Abstract

Matrix effects in mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) may affect the observed molecular distribution in chemical and biological systems. In this study, we use mouse brain tissue of a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) stroke model to examine matrix effects in nanospray desorption electrospray ionization MSI (nano-DESI MSI). This is achieved by normalizing the intensity of the sodium and potassium adducts of endogenous phosphatidylcholine (PC) species to the intensity of the corresponding adduct of the PC standard supplied at a constant rate with the nano-DESI solvent. The use of MCAO model with an ischemic region localized to one hemisphere of the brain enables immediate comparison of matrix effects within one ion image. Furthermore, significant differences in sodium and potassium concentrations in the ischemic region in comparison with the healthy tissue allowed us to distinguish between two types of matrix effects. Specifically, we discuss matrix effects originating from variations in alkali metal concentrations and matrix effects originating from variations in the molecular composition of the tissue. Compensation for both types of matrix effects was achieved by normalizing the signals corresponding to endogenous PC to the signals of the standards. This approach, which does not introduce any complexity in sample preparation, efficiently compensates for signal variations resulting from differences in the local concentrations of sodium and potassium in tissue sections and from the complexity of the extracted analyte mixture derived from local variations in molecular composition.

Keywords: imaging mass spectrometry, nanospray desorption electrospray ionization (nano-DESI), mouse brain, matrix effects, stroke, MCAO

Introduction

MSI provides detailed information on the spatial localization of molecules in biological systems by recording mass spectra directly from specific locations on the sample surface.1–7 The strength of MSI is the ability to reveal regional chemical changes using diminutive amounts of sample. However, analyte ionization efficiency in MSI is dependent on the chemical composition of the surrounding matrix at the time of ionization, making it prone to matrix effects.8 The presence of cations during ionization affects the efficiency of adduct formation in positive mode (e.g. protonation or alkali ion adduct formation) while the presence of other molecules, originating from the sampled region, can affect the analyte signal.9 Matrix effects which arise from the competition of analyte molecules for charge, have been reported in MSI of drugs in tissue sections10–16 while matrix effects caused by changes in cation concentration have been observed in MSI of brain injury and stroke models.17–21 For example, MSI studies of ischemic brain tissues report increased ion signals of phosphatidylcholine (PC) cationized on sodium and decreased signals of protonated PC and PC cationized on potassium in comparison with normal brain tissue.17, 19, 20, 22 These observations were attributed to the differences in concentrations of sodium and potassium in the corresponding tissues. To overcome matrix effects caused by variations in the alkali ion concentration, Wang et al. developed an approach for desalting brain tissue sections prior to MSI experiments.20 MSI studies of brain tissue from stroke models have found an increase of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) in the ischemic region. This increase of LPC may be a result of degradation of PC by phospholipase A2 activated in ischemic tissue by the release of glutamate.23–27

Development of MSI approaches that account for matrix effects is critically important for obtaining accurate spatial localization of molecules in biological systems. Herein, we describe an approach that compensates for matrix effects in nanospray desorption electrospray ionization (nano-DESI) and enables accurate ambient imaging of tissue sections with minimal sample preparation. Nano-DESI is an ambient ionization technique that utilizes gentle localized liquid extraction of molecules from the sample surface followed by electrospray ionization.28–32 Nano-DESI has been used for imaging and quantification of drugs and endogenous lipids in tissue sections10, 33–35 as well as tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) imaging.36 In this study, we use the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) stroke model which produces a localized ischemic region on one hemisphere of the brain leaving another side intact.27, 37–41 The substantial increase in sodium and decrease in potassium concentration as a result of ischemia and their effect on ion images are of particular importance to this study. Because both the ischemic and the control region are present in the same sample, MCAO brain tissue sections are excellent model systems for studying two types of matrix effects: 1) matrix effects originating from variations in alkali cation concentrations, and 2) matrix effects originating from variations in the molecular composition of the tissue. PC species are highly abundant in the mass spectrum of brain tissues and are therefore excellent targets for evaluation of new MSI approaches. We have previously shown that endogenous PC can be quantified in nano-DESI imaging by doping the solvent with two PC standards and using carbon factors33 but could not systematically examine matrix effects in MSI. Here, we use the MCAO mouse model system to identify and compensate for different types of matrix effects in nano-DESI MSI. We demonstrate that doping the solvent with a single PC standard in nano-DESI MSI enables acquisition of ion images of PC and LPC free of matrix effects. Compensation for matrix effects in nano-DESI MSI is achieved by normalizing ion images of endogenous species to the ion image of the corresponding alkali metal adduct of the standard. This study contributes to a fundamental understanding of matrix effects in MSI and establishes nano-DESI MSI as a robust tool for lipid imaging in complex tissue sections.

Experimental section

Focal cerebral ischemia was induced in three C57BL/6 mice (male, 8–12 weeks, Jackson Laboratories, West Sacramento, CA) by MCAO as previously published.42, 43 This model produces a highly reproducible infarct in C57BL/6 mice and has been used extensively as a model of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury.41 Mice were briefly induced with 3% isoflurane and maintained with 1.5–2% throughout the surgery. The middle cerebral artery (MCA) was blocked by threading silicone-coated 7-0 monofilament nylon surgical suture through the external carotid to the internal carotid, and finally blocking its bifurcation into the MCA and anterior cerebral artery. The filament was maintained for 60 min while the mice were maintained under anesthesia. The filament was removed, and blood flow restored. Cerebral blood flow was monitored with Laser Doppler Flowmetry (Transonic System Inc.). Any mouse that did not maintain a CBF during occlusion of <20% of baseline or failed to reach >80% of baseline following removal of suture was excluded from the study. Temperature was maintained at 37°C±0.5°C with a rectal thermometer-controlled heating pad and lamp (Harvard Apparatus). Two hours following restoration of blood flow, the mouse was perfused with cold, heparinized saline, the brain was removed, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C prior to coronal cryo-sectioning (Cryostar NX70, ThermoScientific). 12 µm thick tissue sections were thaw-mounted onto regular glass slides and three sections from each mouse were imaged.

The nano-DESI probe was assembled using two fused silica capillaries (50 × 150 µm, ID × OD, Polymicro Technologies) mounted in a capillary holder, as described elsewhere.36 The tip of the primary capillary was beveled using a microbeveler (Microbeveler 48000, World Precision Instruments, Inc.) to avoid scratching the surface during MSI. Two standards, PC 12:0/13:0 and PC 21:0/22:6 (Avanti Polar Lipids), were diluted in methanol to a final concentration of 4.69 µM and 4.31 µM, respectively, and supplied through the primary capillary at 0.5 µL/min using a syringe pump (Legato 180, KD Scientific). The sample was continuously moved in lines, spaced by 200 µm, under the nano-DESI probe at a velocity of 40 µm/s. The distance between the sample and the probe was controlled using a motorized XYZ stage programmed to account for the tilt of the plane in which the sample resided, as described elsewhere.34 Mass spectra were continuously acquired in a full scan mode (m/z 100–2000, mass resolution of m/Δm=60,000) using an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). A high voltage of 3 kV was applied to the primary capillary and the heated inlet was kept at 250°C. Raw data was obtained with XCalibur (Thermo Scientific) and processed using MSI-Quickview, a program developed at PNNL and described in detail elsewhere.34 PC species were identified using MS/MS.

Results and discussion

Spectra Comparison between Healthy and Ischemic Region

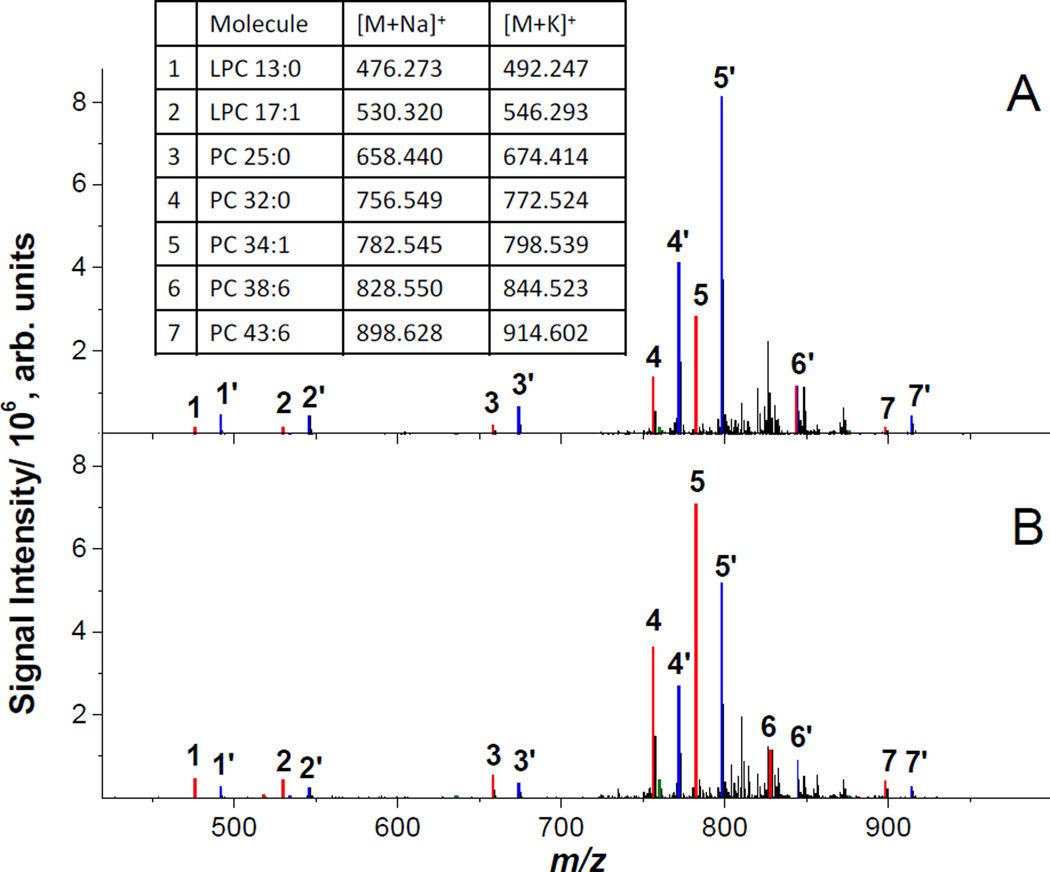

In MCAO mouse models, brain ischemia is induced on one hemisphere of the brain with the other hemisphere presenting a control tissue largely unaffected by stroke. As a result, imaging of coronal brain tissue sections facilitates direct comparison of healthy and ischemic tissue in one experiment.40 Nano-DESI spectra from healthy and ischemic striatum are shown in Figure 1A and 1B, respectively. The spectra are dominated by PC species cationized on sodium and potassium while protonated PC species are observed as minor peaks. The most abundant peaks found in the spectrum from the healthy side of the brain are m/z 798.54, [PC 34:1+K]+, and m/z 772.52, [PC 32:0+K]+. The most abundant peaks found in the spectrum from the ischemic region originate from the same PC cationized on sodium instead of potassium; m/z 782.57, [PC 34:1+Na]+, and m/z 756.55, [PC 32:0+Na]+. This shift in cationization between the healthy and the ischemic region observed for all the peaks in the mass spectrum can be rationalized assuming that there is a significant difference in the amount of sodium and potassium in healthy and ischemic tissues, which is consistent with previous studies.17, 19–21, 37, 38, 44–46 Specifically, atomic spectroscopy analysis demonstrated significantly elevated sodium and reduced potassium concentrations at the ischemic site of MCAO rats.37

Figure 1.

Nano-DESI spectra of A) healthy striatum and B) ischemic striatum of the MCAO mouse brain tissue section. Color coding shows [M+Na]+ (red), [M+K]+ (blue), and [M+H]+ (green) ions of the four standards and three endogenous PC species with the corresponding m/z values listed in the table. Protonated PC species are observed as minor peaks.

Because ion signals in MSI experiments depend both on the concentration of alkali cations and the molecular composition, accurate determination of analyte localization in MSI is challenging. In this study, we examine signal suppression in MSI by adding standards into the nano-DESI solvent and monitoring the signal of the standard as a function of the position on the tissue sample. Furthermore, we show efficient compensation for matrix effects by normalizing ion images of endogenous PC and LPC species extracted from the tissue sample to the ion image of an appropriate adduct of the PC or LPC standard. In this experiment, we added four standards of known concentration, LPC 13:0, LPC 17:1, PC 12:0/13:0 (hereafter referred to as PC 25:0) and PC 21:0/22:6 (hereafter referred to as PC 43:6), to the nano-DESI solvent. These standards have similar ionization efficiency as endogenous LPC and PC, respectively,47 and the m/z values of the standards do not overlap with m/z of endogenous lipids, as shown in Figure S1 of the supporting information.

Matrix Effects in MSI

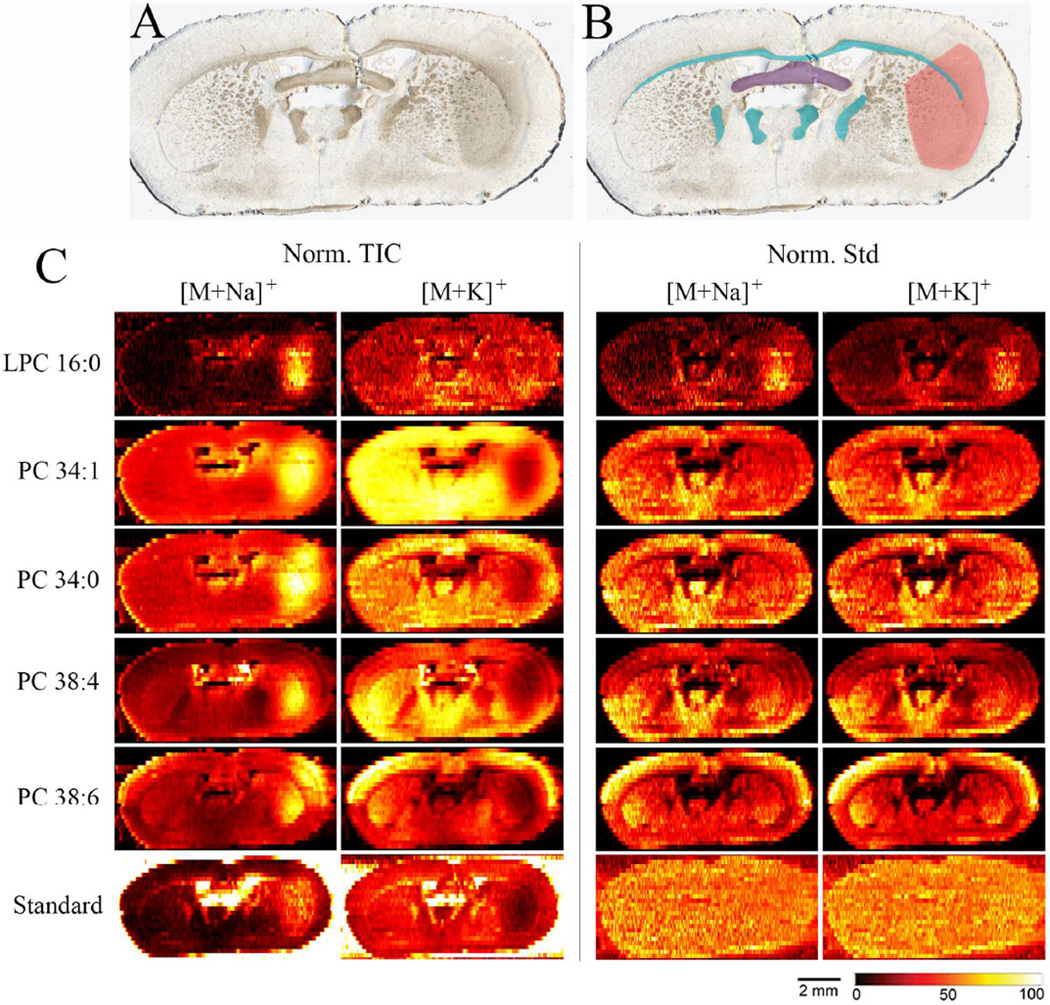

To investigate matrix effects in MSI, we imaged brain tissue sections from MCAO treated mice. The MCAO mouse model was chosen because it enables investigation of matrix effect originating both from chemical heterogeneity and from large variations in alkali cation concentration.27, 37 The optical image of one imaged tissue section is shown in Figure 2A; in Figure 2B the ischemic region is marked pink and the white matter regions are marked blue. Ion images of [M+Na]+ and [M+K]+ ions of endogenous LPC 16:0, PC 34:1, PC 34:0, PC 38:6, PC 38:4 and the standard PC 43:6 for this section, are shown in Figure 2C. The ion images are normalized to the total ion current (TIC) in the left column and to the standard PC 25:0 in the right column. Note that [M+Na]+ are normalized to [PC 25:0+Na]+ and [M+K]+ are normalized to [PC 25:0+K]+. Since the standard and the endogenous PC experience the same signal suppression effects, the ion images of [M+K]+ and [M+Na]+ normalized to the corresponding standards are expected to be the same and reflect the actual distribution of the endogenous PC.

Figure 2.

A) Optical image of the brain tissue section analyzed in this study, B) optical image of the same tissue section with marked areas; pink – ischemic region, blue – white matter regions, purple – ventral hippocampal commissure, C) ion images of sodium and potassium adducts, [M+Na]+ and [M+K]+, of endogenous LPC 16:0, PC 34:1, PC 34:0, PC 38:4, PC 38:6 and standard PC 43:6. Ion images are normalized to the TIC in the left two columns and to the standard PC 25:0 the right two columns. Lateral scale bar is 2 mm. Intensity scale bar ranges from 0 (black) to 100% (light yellow) signal intensity of an individual peak.

Two important observations transpire from the images shown in Figure 2C. First, ion images normalized to the TIC show matrix effects caused by changes in alkali cation concentration: signals of endogenous PC cationized on sodium are enhanced in the ischemic region while signals of endogenous PC cationized on potassium are suppressed. Similar effects were observed in MALDI MSI.17, 19, 21 In the absence of matrix effects, the standard (PC 43:6), which is supplied at a constant rate, should show a uniform distribution over the tissue section. However, Figure 2C shows that, when normalized to TIC, the signal of [PC 43:6+Na]+ is enhanced and the signal of [PC 43:6+K]+ is suppressed in the ischemic region - similar to endogenous PC. When instead normalized to the standard PC 25:0, ion images of the second PC 43:6 standard, show the expected uniform distribution across the tissue section for both [PC 43:6+Na]+ and [PC 43:6+K]+. Furthermore, when ion images of endogenous PC are normalized to the standard they no longer show a clear localization or anti-localization to the ischemic site, regardless of cationization. Instead, remarkably similar distributions are obtained for both alkali metal adducts of endogenous PC species. This is also true for protonated PC (Figure S2B) which has a similar distribution as PC cationized on sodium when normalized to TIC. Due to the similarity in ionization efficiency between LPC and PC, normalization of LPC 16:0 to PC 25:0 gives the qualitative matrix free ion image shown in Figure 2. This is confirmed by the almost identical ion image of LPC 16:0 normalized to LPC 13:0 shown in Figure S2A of the supporting information and the uniform distribution of LPC 13:0 standard normalized to PC 25:0 standard as shown in Figure S2D. Of note, LPC 13:0 experiences higher ion suppression effects on the tissue compared to PC 25:0 resulting in the increased signal outside the tissue observed in Figure S2D.33 Nevertheless, similar signal suppression of both LPC and PC on the tissue enables the use of one PC standard in the nano-DESI solvent for obtaining matrix-free images of both lipid classes. The observed increase of LPC 16:0 in the ischemic region (Figure 2C) is a biological consequence of ischemia, resulting in membrane degradation and generation of free fatty acids and LPC from PC.20, 23–27, 48, 49

Second, ion images of the standard normalized to TIC show increased signal intensity in the white matter regions of the tissue. This is due to matrix effects caused by differences in the molecular composition of the analyte mixture extracted from the white and the gray matter regions. The white matter has a high amount of glycolipids, which are abundant in myelinated axons, while the gray matter has high amounts of phospholipids.50–52 The higher ionization efficiency of phospholipids increases ion suppression effects of molecules in the gray matter, while the lower ionization efficiency of glycolipids enhances the ion yield in the white matter. Although the analyte signal in MSI may be affected by differences in the extraction efficiency of molecules from the tissue, our recent study indicates that in nano-DESI imaging the extraction efficiency of endogenous PC is independent of the brain tissue region.33 Because both PC standards and endogenous PC molecules experience similar suppression during ionization, normalization to the standard compensates for matrix effects. Ion images normalized to the standard reveal clear morphological structures including the dorsal 3rd and lateral ventricles and several white matter regions. Furthermore, the endogenous PC 38:4 shows a clear localization to the ventral hippocampal commissure.

For a more detailed view of the observed matrix effects we are providing line scan traces of endogenous and standard PC in Figure S3 of the supporting information. In addition to standard and TIC-normalized traces Figure S3 shows non-normalized traces displaying very similar results as the TIC-normalized data.

Conclusions

Matrix effects in MSI may affect the observed localization of molecules in biological systems. In this study, we show that doping the nano-DESI solvent with appropriate standards enables identification of and compensation for matrix effects in nano-DESI MSI. Using MCAO mouse brain tissue as a model system, we identify suppression of potassium adducts and enhancement of sodium adducts of PC in the ischemic region of the brain, and an overall enhancement of PC in white matter regions. Compensation for matrix effects is achieved by normalizing ion signals of endogenous PC to the signal of the corresponding adduct of the PC standard. The resulting ion images show identical distributions of [PC+Na]+ and [PC+K]+ and enhancement of LPC ([M+Na]+ and [M+K]+) in the ischemic region. The increase of LPC in the ischemic region is in agreement with previously published data confirming efficient compensation for matrix effects in nano-DESI imaging of biological tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research described in this paper is part of the Chemical Imaging Initiative, at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) supported under the PNNL’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program. PNNL is operated by Battelle for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830. The research was performed using EMSL, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the DOE’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at PNNL. Research performed at OHSU was supported by the NIH-NINDS NS062381 (MSP). We thank Dr. Mingyue Liu and Valerie Conrad for excellent technical support.

References

- 1.Badu-Tawiah AK, Eberlin LS, Ouyang Z, Cooks RG. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2013;64:481–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040412-110026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prideaux B, Stoeckli M. Journal of Proteomics. 2012;75:4999–5013. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanni EJ, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Journal of Proteomics. 2012;75:5036–5051. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angel PM, Caprioli RM. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3818–3828. doi: 10.1021/bi301519p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaurand P. Journal of Proteomics. 2012;75:4883–4892. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson SN, Ugarov M, Egan T, Post JD, Langlais D, Schultz JA, Woods AS. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2007;42:1093–1098. doi: 10.1002/jms.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delvolve AM, Colsch B, Woods AS. Anal. Methods. 2011;3:1729–1736. doi: 10.1039/C1AY05107E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heeren RMA, Smith DF, Stauber J, Kukrer-Kaletas B, MacAleese L. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2009;20:1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annesley TM. Clinical Chemistry. 2003;49:1041–1044. doi: 10.1373/49.7.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanekoff I, Thomas M, Carson JP, Smith JN, Timchalk C, Laskin J. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;85:882–889. doi: 10.1021/ac302308p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoeckli M, Staab D, Schweitzer A. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2007;260:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marko-Varga G, Fehniger TE, Rezeli M, Doeme B, Laurell T, Vegvari A. Journal of Proteomics. 2011;74:982–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groseclose MR, Castellino S. Analytical chemistry. 2013;85:10099–10106. doi: 10.1021/ac400892z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamm G, Bonnel D, Legouffe R, Pamelard F, Delbos J-M, Bouzom F, Stauber J. Journal of Proteomics. 2012;75:4952–4961. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vismeh R, Waldon DJ, Teffera Y, Zhao Z. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:5439–5445. doi: 10.1021/ac3011654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pirman DA, Reich RF, Kiss A, Heeren RMA, Yost RA. Analytical Chemistry. 2013;85:1081–1089. doi: 10.1021/ac302960j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hankin J, Farias S, Barkley R, Heidenreich K, Frey L, Hamazaki K, Kim H-Y, Murphy R. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2011;22:1014–1021. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hankin JA, Murphy RC. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82:8476–8484. doi: 10.1021/ac101079v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanta SR, Choi CS, Lee JH, Shin CY, Kim YJ, Kim K-H, Kim KP. Journal of Lipid Research. 2012;53:1823–1831. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M022558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang H-YJ, Wu H-W, Tsai P-J, Liu CB. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2012;404:113–124. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H-YJ, Liu CB, Wu H-W, Kuo S., Jr Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2010;24:2057–2064. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koizumi S, Yamamoto S, Hayasaka T, Konishi Y, Yamaguchi-Okada M, Goto-Inoue N, Sugiura Y, Setou M, Namba H. Neuroscience. 2010;168:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wender M, Adamczewska-Goncerzewicz Z, Dorszewska J, Szczech J, Godlewski A, Pankrac J, Talkowska D. Neuropatol. Pol. 1991;29:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun G, Foundin L. J. Neurochem. 1984;43:1081–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb12847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein J. J Neural Transm. 2000;107:1027–1063. doi: 10.1007/s007020070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto Y, Okamoto S, Yonekawa Y, Taki W, Kikuchi H, Handa H, Kito M. Stroke. 1988;19:728–735. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doyle KP, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roach PJ, Laskin J, Laskin A. Analyst. 2010;135:2233–2236. doi: 10.1039/c0an00312c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanekoff I, Geydebrekht O, Pinchuk GE, Konopka AE, Laskin J. Analyst. 2013;138:1971–1978. doi: 10.1039/c3an36716a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roach PJ, Laskin J, Laskin A. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82:7979–7986. doi: 10.1021/ac101449p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eckert PA, Roach PJ, Laskin A, Laskin J. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:1517–1525. doi: 10.1021/ac202801g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laskin J, Eckert PA, Roach PJ, Heath BS, Nizkorodov SA, Laskin A. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:7179–7187. doi: 10.1021/ac301533z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanekoff I, Thomas M, Laskin J. Analytical Chemistry. 2014;86:1872–1880. doi: 10.1021/ac403931r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanekoff I, Heath BS, Liyu A, Thomas M, Carson JP, Laskin J. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:8351–8356. doi: 10.1021/ac301909a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laskin J, Heath BS, Roach PJ, Cazares L, Semmes OJ. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:141–148. doi: 10.1021/ac2021322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanekoff I, Burnum-Johnson K, Thomas M, Short J, Carson JP, Cha J, Dey SK, Yang P, Conaway M, Laskin J. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:9596. doi: 10.1021/ac401760s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young W, Rappaport ZH, Chalif DJ, Flamm ES. Stroke. 1987;18:751–759. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanekar SG, Zacharia T, Roller R. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2012;198:63–74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.7312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casals JB, Pieri NC, Feitosa ML, Ercolin AC, Roballo KC, Barreto RS, Bressan FF, Martins DS, Miglino MA, Ambrósio CE. Comp Med. 2011;61:305–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popp A, Jaenisch N, Witte OW, Frahm C. Plos One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu F, McCullough LD. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2011;2011:9. doi: 10.1155/2011/464701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens SL, Leung PY, Vartanian KB, Gopalan B, Yang T, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:8456–8463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0821-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Packard AEB, Hedges JC, Bahjat FR, Stevens SL, Conlin MJ, Salazar AM, Stenzel-Poore MP. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:242–247. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin Z, Caruso JA, Lai B, Matusch A, Becker JS. Metallomics. 2011;3:28–37. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00048e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yushmanov VE, Kharlamov A, Yanovski B, LaVerde G, Boada FE, Jones SC. Brain Research. 2013;1527:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi S, Hatashita S, Taba Y, Sun XZ, Kubota Y, Yoshida S. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2000;100:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pulfer M, Murphy RC. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 2003;22:332–364. doi: 10.1002/mas.10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun G, Lu F, Lin S, Ko M. Molecular and Chemical Neuropathology. 1992;17:39–50. doi: 10.1007/BF03159980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF, Dempsey RJ. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2004;76:390–396. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morell P, Quarles R. In: Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6 edn. Siegel G AB, Albers R, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Obrien JS, Fillerup DL, Mead JF. Journal of Lipid Research. 1964;5 109-&. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Obrien JS, Sampson EL. Journal of Lipid Research. 1965;6:545–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.