Abstract

Many studies have implicated a role for conformational motions during the catalytic cycle, acting to optimize the binding pocket or facilitate product release, but a more intimate role in the chemical reaction has not been described. We address this by monitoring active-site loop motion in two protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) using NMR spectroscopy. The PTPs, YopH and PTP1B, have very different catalytic rates, however we find in both that the active-site loop closes to its catalytically competent position at rates that mirror the phosphotyrosine cleavage kinetics. This loop contains the catalytic acid, suggesting that loop closure occurs concomitantly with the protonation of the leaving group tyrosine and explains the different kinetics of two otherwise chemically and mechanistically indistinguishable enzymes.

Molecular motions are crucial for the optimal functioning of enzymes. There has been much debate regarding what role motions play in the enzymatic conversion of substrates to products (1, 2) and recent studies, primarily solution NMR relaxation experiments, have shown that enzyme motions are critical for optimizing the active site (3–6), enabling effective substrate or cofactors binding (7) and facilitating product dissociation (8). These motions often require collective movement of many amino acids over significant molecular distances (9), and are indispensible for chemistry. Furthermore, motions appear to have been evolutionarily optimized to accommodate the extreme environments in which enzymes must function (10). Often, motions are rate-limiting to enzyme turnover, however this is mainly via product release, whereas the chemical steps are usually much faster (11). As a result, the direct participation of molecular motions in the chemical steps of an enzyme reaction, with few exceptions (12, 13), remains largely untested experimentally.

Here, we address this question through a comparison of active site loop motions in two structurally similar protein tyrosine phosphatases (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A), YopH, a virulence factor from Yersinia (14) and PTP1B, a human phosphatase that is involved in regulating insulin, leptin, and epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling (15). These enzymes catalyze the cleavage of the tyrosine phosphate monoester (pY) of their protein substrates followed by hydrolysis of the phosphoenzyme intermediate. YopH and PTP1B contain, ten-residue WPD active site loops and conserved, eight-residue P-loops. The P-loops bind the phosphate moiety of the substrate and contain the catalytic nucleophile C403(C215) in YopH(PTP1B) (Fig. 1C,D). The WPD loop contains an aspartic acid D356 (D181) that serves as the general acid to protonate the leaving group, such that Tyr leaves as the alcohol rather than the alkoxide (Fig 1. B–D). The P-loop does not undergo a significant conformational change during catalysis. However, motions of approximately 10 Å differentiate the open (apo) and the catalytically competent closed WPD loop (Fig. 1B). The closed WPD loop positions the general acid near the oxygen of the leaving group of the substrate. YopH and PTP1B reactions occur in two steps (Fig. 1D). First, after substrate binds, the WPD loop closes and catalyzes the cleavage (kcleavage) of the phosphotyrosine moiety, generating a phosphoenzyme intermediate and a tyrosine-peptide. Subsequently, the phosphoenzyme intermediate is hydrolyzed (khydrolysis) regenerating active enzyme and releasing inorganic phosphate. YopH and PTP1B share equivalent chemical mechanisms and transition states for P–O bond cleavage. In both, kinetic isotope effects (KIE) (16, 17) showed the leaving group oxygen to be fully protonated in the transition state for phosphotyrosine cleavage, a conclusion supported by the negligible dependence (β = − 0.008) on leaving group basicity (18). Despite very similar substrate interactions and chemical mechanisms, their kcat values, which are partially limited by the rate of hydrolysis of the phosphoenzyme intermediate, are significantly different with YopH about 20 -fold more active than PTP1B for phosphopeptide substrate with temperature adjusted catalytic rates of 700 – 1000 s−1 vs 15 – 30 s−1 respectively, at pH = 6.6 and 293 K (19). The cleavage of phosphopeptide is faster than the hydrolysis step, as evidenced by burst kinetics and an observed kinetic solvent deuterium isotope effect on the overall reaction (20). Overall, these kinetic data indicate that kcleavage for YopH and PTP1B range from 1400 – 2000 s−1 and 30 – 80 s−1, respectively. Here, we describe the WPD loop motion by solution phase NMR relaxation dispersion studies and focus on the role of loop closure in the cleavage step.

Fig. 1. Comparison of YopH and PTP1B.

(A) YopH (cyan) and PTP1B (gray), the phosphate analog, vanadate (gray and red spheres), localizes the active site. (B) Open (light gray) and closed (blue) WPD loops of PTP1B. Vanadate (spheres) binds in the P-loop (orange), with C215 and R221 in stick rendering. Movement of D181 is indicated by dashed lines. (C) Superposition of closed loops for PTP1B and YopH. The three catalytic residues are shown in stick rendering. (D) PTP catalytic reaction of cleavage and hydrolysis. (A) PDB accession numbers are 2I42 and 3I80.

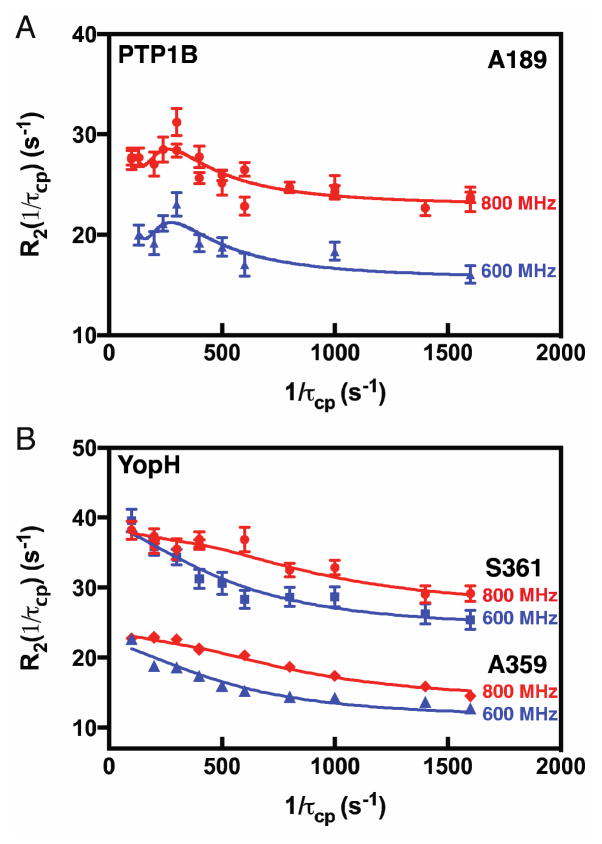

The apo (ligand-free) forms of PTP1B and YopH behave very differently. We applied 15N-Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion experiments to PTP1B (21), in which the measured relaxation rate (R2) depends on the physical parameters for motion, (equilibrium populations pa/pb and chemical shift differences (Δω) between the two interconverting conformations, and kinetics (kex = kf + kr)) and τcp, which is the delay between 15N 180º pulses (SM equation 1). For PTP1B, we have assigned amide resonances for W179, F182, G183, V184, S187, and A189 in the WPD loop. Of these, resonances for G183 and S187 are too weak to quantitate and V184 is partially overlapped precluding further analysis. The remaining WPD loop residues (W179, F182, and A189, Fig. S1B-D), show upward curving CPMG relaxation dispersion (Figs. 2A-C). The exchange parameters are shown in Table 1. Their individual fits yield similar exchange rates with kex ~ 900 s−1 suggesting concerted loop motion. Therefore F182 and A189 data were fit to a global model simultaneously at 600 and 800 MHz (Table 1). For these two residues pa(pb) = 97.5 ± 1.4% (2.5%). Knowledge of pa and kex enables determination of kf (kr) = 22 ± 5 (890 ± 190) s−1. The larger uncertainties in measured R2 values for W179 precluded use of SM equation 1 however, reliable kex values = 900 ± 200 s−1 and Rex (= papbΔω2/kex) = 31.4 ± 4.6 s−1 are obtained for this residue using SM equation 2 (Fig. 1C). Using pa = 97.5% determined above, Δω for W179 is calculated to be 2.8 ± 0.9 ppm (Table 1).

Fig. 2. NMR detected motions.

Apo- PTP1B and YopH WPD loops (A). (B & C) show 15N-CPMG dispersion curves for A189, F182, and W179. In (D) TROSY-detected off-resonance 1H-R1ρ dispersion curves for A359 (blue) and S361 (red).

Table 1.

Summary of WPD loop motions

| Enzyme | kex (s−1) | kclose (s−1) | kopen (s−1) | a Keq | 15N Δω (ppm)b | 15N Δδcalc (ppm)c | 15N Δωmeas (ppm)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTP1B apo | 920 ± 190 | 22 ± 5 | 890 ± 190 | 40 | A189: 3.8 ± 0.6 F182: 3.4 ± 1.3 W179: 2.8 ± 0.9 |

A189: 3.7 ± 0.2 F182: 4.9 ± 1.0 W179: 1.9 ± 0.5 |

A189: 3.87 F182: 3.60 Not Determined |

| PTP1B/peptide | 35 ± 5 | 30 ± 4 | 4.5 ± 1 | 0.15 | A189: 3.2 ± 0.3 | A189: 3.7 ± 0.2 | A189: 3.87 |

| YopH apo | 43000 ± 6200 | 1240 ± 200 | 42000 ± 6000 | 34 | Not Determined | A359: 3.4 ± 0.4 S361: 6.4 ± 1.2 |

A359: 3.82 S361: 3.96 |

| YopH/peptide | 1790 ± 240 | 1770 ± 240 | 18 ± 2 | 0.01 | A359: 3.5 ± 0.4 S361: 4.5 ± 0.8 |

A359: 3.4 ± 0.4 S361: 6.4 ± 1.2 |

A359: 3.82 S361: 3.96 |

open/closed loop equilibrium derived from popen/pclosed;

determined from fits to relaxation dispersion data;

determined with ShiftX2 as described in SM Methods;

determined from differences in measured chemical shifts between apo and peptide bound enzyme.

Based on the many apo PTP1B crystal structures (22), we hypothesized that the major solution conformer is an open WPD loop with a minor population of closed WPD loop, supported by an apo closed crystal structure (1SUG (23)) with a closed active site loop. This interconversion between open and closed conformations means that kf (kr) represent the rates for loop closure (opening). Support for this hypothesis comes from measurement of the chemical shift differences between the open and closed WPD loop, which were determined by direct measurement ( )(SM Methods) of the difference in open and closed shifts for the apo and peptide bound (vide infra) enzyme. Moreover, the difference ( ) between calculated shifts for the closed conformation based on the crystal structure and the measured shifts for the open conformation was determined. These Δω, values are nearly identical for F182, A189, similarly for W179, whose bound resonance disappears, Δω and are within error (Fig 3A,B Fig. S3A and Table 1). The agreement between these shifts supports the hypothesis that the apo loop converts between a predominantly open conformation with a minor closed state and strikingly indicates that the WPD loop in apo PTP1B closes (kclose = kf = 22 ± 5 s−1) with a rate constant very similar to its kcleavage value of 30 – 80 s−1 (See Methods) suggesting that, if the enzyme maintained these motions in the substrate bound state, loop closure occurs simultaneously with protonation of the leaving group substrate.

Fig. 3. Chemical shift differences for open and closed WPD loops.

For PTP1B (A,B) and YopH (C,D) the NMR measured (red symbols) and calculated (black open symbols) chemical shifts are shown for residues in the WPD loop.

Distinct from PTP1B, YopH is over an order of magnitude faster in its enzymatic reaction. WPD loop resonances for T358, A359, V360 and S361 were assigned (Fig. S4A). In contrast to PTP1B, YopH 15N-CPMG and 15N-R1ρ dispersion curves are flat (Fig. S4B,C) indicating loop motions ≥ 30,000 s−1. To detect these faster motions we modified a 1H-R1ρ experiment (24) for TROSY detection (Fig. S5) and applied it to YopH. In Fig. 2D-E, dispersion is observed for loop residues A359 and S361 with global kex = 43,000 ± 6200 s−1. T358 is overlapped and V360 had low signal-to-noise for quantitation. Like PTP1B, our hypothesis is that the WPD loop moves between open and closed conformations, which is supported by the similarity in and 15N chemical shifts for A359 and S361 (Fig. 3C-D) and for T358 and V360 (Fig. S3B-C).

The motion of the apo YopH WPD loop is in the fast exchange limit and therefore other methods are needed to extract Δω and populations from this data since they appear as the product, papbΔω2 in equation (1)

| (1) |

To circumvent this limitation we measured the 15N-Rex values (Rex = papbΔω2/kex) from a 15N TROSY Hahn-echo experiment (25) (Fig. S6), (For details see SM) and used the measured kex and as a proxy for Δω to give pa = 97%. A loop closing rate kclose = 1240 ± 280 s−1 (Table 1) is calculated for YopH, which is about 1.7-fold greater than its kcat value, and similar to kcleavage (1400 s−1 – 2000 s−1) suggesting that, like PTP1B, there is intimate involvement of WPD loop closure in the step of pY cleavage. Thus, for two enzymes with very different catalytic rates and identical chemical mechanisms, active-site loop motion in the apo enzyme is tuned to approximate the overall cleavage rate in each. Because the WPD loop must be closed for chemistry to occur, loop closing on the proper timescale will facilitate the chemical reaction.

We formed the complex between PTP1B and an octamer peptide, Ac-DADEXLIP-NH2 (Fig. S2A) derived from EGFR, where X is difluoromethylphosphono-phenylalanine, a non-cleavable phosphotyrosine mimic. The inhibition constant (Ki) value of the peptide (high nM, low μM) is similar to the substrate Km indicating DADEXLIP behaves as a good substrate mimic (26). In PTP1B, F182 is significantly exchange broadened in the peptide bound form and the resonance for W179 disappears preventing further analysis. Both observations indicate a change in loop motions. 15N-CPMG dispersion curves at 600 and 800 MHz for A189 in peptide-bound PTP1B are noticeably different from apo PTP1B and display pronounced oscillation at low CPMG pulsing frequencies, characteristic of slow conformational exchange (Fig. 4A & SM Eq. 3). The A189 Δω = 1210 ± 130 s−1 (3.2 ± 0.3 ppm) is identical to that determined in ligand-free PTP1B (Table 1). The equivalence of Δω for apo and peptide bound PTP1B is additional evidence that when substrate occupies the active site, the WPD loop interconverts between major closed and minor open conformations. Further support for this hypothesis comes from a PTP1B ligand-bound crystal structure (3EB1(27)) in which the WPD loop is open, unlike the majority of other bound structures. From this data we obtain a kclose (kopen) = 30 ± 4 s-1 (5 ± 1 s−1). Thus, loop closure is the same in apo and peptide bound PTP1B; peptide binding only slows loop opening. The similarity of kclose and kcleavage along with KIE data (16, 17) indicating leaving group protonation in the transition state suggests that protonation of the tyrosine occurs concomitantly with loop closure with the proton being delivered by D181 on the WPD loop. Cleavage of phosphotyrosine is followed by hydrolysis of the phosphoenzyme intermediate, which occurs somewhat slower. These NMR data suggest that closing of the WPD loop occurs in close connection with the chemistry of phosphate cleavage and plays a significant regulatory role in the overall catalytic cycle.

Fig. 4. NMR detected motions.

15N-CPMG dispersion analyses for peptide bound- PTP1B (A) and YopH (B). (A) shows a global fit at 800 and 600 MHz for A189. (B) shows a global fit at 800 (red) and 600 (blue) MHz for A359 and S361 in YopH.

For YopH bound to peptide, loop motion slows significantly such that the 15N-CPMG dispersion experiment can now be used for characterization, in stark contrast to apo YopH (Fig. 4B). Global fits of SM equation 1 to the dispersion data in Fig. 4B gives Δω values for A359 and S361 of 1350 ± 150 s−1 (3.5 ppm) and 1730 ± 290 s−1 (4.5 ppm), which are similar to the apo Δω, and values, as they are in PTP1B, indicating interconversion between open and closed conformations (Table 1). For the YopH loop, kex = 1790 ± 240 s−1, pa = 99% to give, kclose (kopen) = 1770 ± 240 s–1 (18 ± 2 s−1). Like PTP1B, peptide binding to YopH only slows loop opening. Thus, in this faster YopH enzyme kclose and kcleavage are similar again suggesting that loop closure is concerted with protonation of the leaving group tyrosine as part of the cleavage reaction. Unlike the apo and peptide bound enzymes, the product state mimic, tungstate, dissociates from PTB1B and YopH with identical rate constants (Figure S7 and SM methods). Thus, once cleavage and hydrolysis are complete, release of product is the same for both enzymes.

These NMR results for YopH are different than observed by other techniques. For apo YopH, Trp flourescence anisotropy and T-Jump fluorescent experiments suggest loop kinetics ranging from 3 ns to 3 μs, respectively(28, 29). The former value is consistent with MD simulations (30) indicating conformational motion between open and partially closed states, unlike our data that show opening/closing times, similar to T-jump experiments, of 22 μs between open and fully closed conformations. Those fluorescence experiments, however, only report on the indole sidechain of W179, while our NMR data pertain to the motion of the backbone and therefore are more closely connected to the motion of the entire loop. Comparison of YopH loop motion in the bound conformation to other studies is more difficult. We use a peptide whereas the previous T-Jump experiment exploits the fluorescence from p-nitrocatechol sulfate; the differences in ligand choice may explain the 50-fold difference in observed loop kinetics in the respective complexes. For PTP1B there are no available data for comparison.

The data presented for this pair of phosphatases suggest that the tuning of loop motion is closely synchronized with the chemical reaction of phosphotryosine cleavage. During the femtosecond bond making and breaking steps of the enzyme reaction, the WPD loop is static on the timescale observable by NMR. Our NMR experiments do however suggest a contiguous energy landscape for loop motion and catalytic activity and that loop closure is closely coupled to the protonation of the tyrosine leaving group. Interestingly, the nature of the occupancy of the active site modulates the WPD loop kinetics and is consistent with the dynamic energy landscape hypothesis of enzyme function (3).

A myriad of crucial biological pathways are regulated by post-translational protein phosphorylation levels. Remarkably, our NMR data for these phophatases suggests phosphorylation levels can be modulated through control of WPD loop kinetics. The additional Pro residues in the PTP1B loop are potentially responsible for the slower motions. Slower PTP1B loop motions likely reflect the physiological role of PTP1B as a tight regulator of cellular processes, in which its turnover rate must meet the strict growth requirements of the cell. In contrast, the faster loop motion and enzymatic activity in YopH would be beneficial for the rapid disruption of normal cellular pathways that enable this enzyme to participate in and facilitate Yersinia infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeff Hoch, Dmitry Korzhnev, Mark Maciejewski, and Geoffrey Armstrong for access to their high-field NMR instruments. We thank Gennady Khirich for running Monte Carlo simulations. SKW, ACH, and JPL acknowledge support from grants NIH-T32GM008283, NIH-GM47297, and NSF-MCB1121372.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Kamerlin SC, Warshel A. Proteins. 2010;78:1339–1375. doi: 10.1002/prot.22654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamczyk AJ, Cao J, Kamerlin SC, Warshel A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14115–14120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111252108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boehr DD, McElheny D, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Science. 2006;313:1638–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1130258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rozovsky S, McDermott AE. Proc Nat Acad Sci (USA) 2007;104:2080–2085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608876104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenmesser EZ, et al. Nature. 2005;438:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature04105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henzler-Wildman KA, et al. Nature. 2007;450:838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhabha G, et al. Science. 2011;332:234–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1198542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beach H, Cole R, Gill ML, Loria JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9167–9176. doi: 10.1021/ja0514949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph D, Petsko GA, Karplus M. Science. 1990;249:1425–1428. doi: 10.1126/science.2402636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf-Watz M, et al. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:945–949. doi: 10.1038/nsmb821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desamero R, Rozovsky S, Zhadin N, McDermott A, Callender R. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2941–2951. doi: 10.1021/bi026994i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antoniou D, Ge X, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:3538–3544. doi: 10.1021/jz301670s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva RG, Murkin AS, Schramm VL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18661–18665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114900108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brubaker RR. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1991;4:309–324. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang ZY. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:416–423. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandao TA, Hengge AC, Johnson SJ. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15874–15883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hengge AC, Sowa GA, Wu L, Zhang ZY. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13982–13987. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keng YF, Wu L, Zhang ZY. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:809–814. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang ZY, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4446–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang ZY. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11199–11204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loria JP, Rance M, Palmer AG. J Biomol NMR. 1999;15:151–155. doi: 10.1023/a:1008355631073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barford D, Flint AJ, Tonks NK. Science. 1994;263:1397–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen AK, Peters GG, Moller KB, Iversen LF, Kastrup JS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1527–1534. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904015094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eichmuller C, Skrynnikov NR. J Biomol NMR. 2005;32:281–293. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-0658-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C, Rance M, Palmer AG., 3rd J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8968–8969. doi: 10.1021/ja035139z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke TR, Jr, Kole HK, Roller PP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:129–134. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17075–17084. doi: 10.1021/ja8068177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juszczak LJ, Zhang ZY, Wu L, Gottfried DS, Eads DD. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2227–2236. doi: 10.1021/bi9622130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khajehpour M, et al. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4370–4378. doi: 10.1021/bi602335x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu X, Stebbins CE. Biophys J. 2006;91:948–956. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.