Abstract

Mutations in human LIS1 cause abnormal neuronal migration and a smooth brain phenotype known as lissencephaly. Lis1+/− (Pafah1b1) mice show defective lamination in the cerebral cortex and hippocampal formation, whereas homozygous mutations result in embryonic lethality. Given that Lis1 is highly expressed in embryonic neurons, we hypothesized that sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons (SPNs and PPNs) would exhibit migratory defects in Lis1+/− mice. The initial radial migration of SPNs and PPNs that occurs together with somatic motor neurons appeared unaffected in Lis1+/− mice. The subsequent dorsally directed tangential migration, however, was aberrant in a subset of these neurons. At all embryonic ages analyzed, the distribution of SPNs and PPNs in Lis1+/− mice was elongated dorsoventrally compared with Lis1+/+ mice. Individual cell bodies of ectopic preganglionic neurons were found in the ventral spinal cord with their leading processes oriented along their dorsal migratory trajectory. By birth, Lis1+/− SPNs and PPNs were separated into distinct groups, those that were correctly, and those incorrectly positioned in the intermediate horn. As mispositioned SPNs and PPNs still were detected in P30 Lis1+/− mice, we conclude that these neurons ceased migration prematurely. Additionally, we found that a dorsally located group of somatic motor neurons in the lumbar spinal cord, the retrodorsolateral nucleus, showed delayed migration in Lis1+/− mice. These results suggest that Lis1 is required for the dorsally directed tangential migration of many sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons and a subset of somatic motor neurons.

INDEXING TERMS: lissencephaly, pafah1b1, reeler, sympathetic preganglionic neurons, parasympathetic preganglionic neurons, somatic motor neurons

Mutations in human LIS1 (PAFAH1B1; the noncatalytic subunit of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase 1b) result in the most common genetic defects found in patients with lissencephaly, a severe brain malformation characterized by a smooth brain surface rather than the typical cortical gyri and sulci (Dobyns et al., 1993; Reiner et al., 1993). Patients with haploinsufficiency for LIS1 exhibit mental retardation and epilepsy (Dobyns et al., 1993; Hattori et al., 1994; Reiner et al., 1993; Lo Nigro et al., 1997). Neuronal migratory errors underlie the smooth brain malformation as postmitotic cortical neurons move more slowly and stop their migration prematurely, forming a disorganized, four-layered neocortex (Reiner et al., 1995; Hirotsune et al., 1998).

Mice with heterozygous deletions in the murine homolog Lis1 (Pafah1b1) have less severe defects than in the human disorder, but do exhibit defects in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and olfactory bulb due to abnormal neuronal migration (Hirotsune et al., 1998). In addition to neuronal migration, Lis1 is required for cell division, neuroepithelial stem cell generation, and neurogenesis (reviewed by Wynshaw-Boris et al., 2010; Yingling et al., 2008). The homozygous loss of Lis1 is early embryonic lethal due to a requirement for Lis1 expression in the embryonic inner cell mass (Hirotsune et al., 1998; Cahana et al., 2001, 2003).

Neuronal migration is characterized first by the extension of the leading process, followed by nucleokinesis, or the movement of the centrosome, and subsequently the nucleus into the leading process (reviewed by Tsai and Gleeson, 2005). The microtubule network that links the centrosome and nucleus during nucleokinesis is well established. Lis1, dynein, and NudE-like protein (Ndel1) all are required for nuclear translocation during migration (Feng et al., 2000; Shu et al., 2004; reviewed by Wynshaw-Boris, 2007), and the reduction of Lis1 slows neuronal migration by interactions with the microtubules that uncouple the centrosome and nucleus (Tanaka et al., 2004a; Tsai et al., 2007).

Studies of Lis1+/− mice reveal dose-dependent neuronal migration defects (Hirotsune et al., 1998; Gambello et al., 2003; Youn et al., 2009). For example, heterozygous deletions in mouse Lis1 result in mild cerebral cortical defects that involve delayed radial migration and a loss of distinct lamination, whereas lower levels of Lis1 cause a progressively more severe phenotype (Hirotsune et al., 1998). Tangential (nonradial) migration is also affected in human lissencephaly (Pancoast et al., 2005; Marcorelles et al., 2010) and in Lis1+/− mice (McManus et al., 2004; Nasrallah et al., 2006; Gopal et al., 2010). The γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic interneurons that arise from the ganglionic eminence and migrate tangentially into the neocortex exhibit a slowed migration in Lis1+/− mice (McManus et al., 2004) and have longer leading processes that show reduced branching (Nasrallah et al., 2006; Gopal et al., 2010).

Most studies to date have focused on Lis1 in highly organized, cortical structures (Reiner et al., 1995; Hirotsune et al., 1998; Sasaki et al., 2000; Youn et al., 2009). However, Lis1 is broadly and highly expressed in neurons throughout embryonic development, including the embryonic spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia (Reiner et al., 1995; Sasaki et al., 2000). Other gene deletions that lead to lissencephaly, such as reelin and cdk5, also cause migratory errors in the spinal cord (Yip et al., 2000, 2003b, 2007, 2009; Phelps et al., 2002; Villeda et al., 2006). Thus, we asked whether Lis1 deficiency would cause delayed or prematurely terminated nucleokinesis in defined populations of spinal cord neurons. To test this hypothesis, we compared the migration patterns of identified populations of cholinergic neurons in Lis1+/+ and Lis1+/− spinal cord and found evidence for a delayed tangential migration of sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons and a dorsally located group of somatic motor neurons. Furthermore, although many of these neurons achieved their correct positions in adult Lis1+/− spinal cord, a subset of these cells remained permanently mispositioned.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and tissue preparation

A Lis1 mouse (Hirotsune et al., 1998; 129 SvEvTac/NIH Black Swiss background) breeding colony is maintained at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia under a protocol approved by Children’s Hospital animal care and use committee. The presence of a vaginal plug, found after overnight mating, was used to determine pregnancy and recorded as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Embryos and postnatal mice were genotyped as reported (McManus et al., 2004) and fixed by overnight immersion (E13.5–E17.5) or transcardial perfusion (P0–P30) with either 1% paraformaldehyde-lysine-periodate or 4% paraformaldehyde. Spinal cords were washed, cryoprotected, frozen, and stored at −80°C. Spinal cords were sectioned 40 μm thick and stored in 0.12 M sodium phosphate buffer with 0.06% sodium azide. Every sixth (E13.5–E14.5) or ninth (E17.5–P30) thoracic section and every other lumbosacral section were mounted in series on slides before processing.

Antibody characterization

Details on the primary antisera used are given in Table 1. The neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) antiserum (Immunostar, Hudson, WI) recognizes a band of 155 kDa by Western blot analysis that could be eliminated by preadsorption with synthetic human nNOS (manufacturer’s data sheet). The cellular morphology and distribution pattern of nNOS-labeled spinal cord neurons in this study resemble those in previous studies carried out with nNOS immunohistochemistry and NADPH-diaphorase histochemistry (Blottner and Baumgarten, 1992; Dun et al., 1993; Phelps et al., 2002).

TABLE 1.

Primary Antisera Used

| Antigen | Immunogen | Source and ID# | Species | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) | Human placental enzyme | Chemicon (Temecula, CA); AB144P | Goat polyclonal | 1:300 |

| Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) | Human C-terminal peptide sequence (aa 1419–1433) | Immunostar (Hudson, WI); 24287 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:8,000–13,000 |

The affinity-purified choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) antiserum (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) recognizes a single band of 69 kDa on Western blots of rat brain (manufacturer’s data sheet). The cellular distribution of ChAT expression in the spinal cord was identical to that found previously (Barber et al., 1991; Phelps et al., 1991; Phelps et al., 2002).

Immunocytochemical techniques

nNOS immunocytochemistry

SPNs and PPNs were identified by their expression of nNOS with a polyclonal antiserum (Table 1). Dilutions were made in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST; 0.1 M PB, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.3). Sections were incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide and 0.1% sodium azide (30 minutes), rinsed, and blocked in 3% normal goat serum (1 hour) followed by avidin and biotin pretreatment (15 minutes each; Vector, Burlingame, CA). Sections were then incubated overnight in nNOS antiserum (1:8,000–13,000). After rinsing, sections were incubated for 1 hour in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Vector Elite Rabbit Kit), washed, and incubated in avidinbiotin complex (1:100; Vector) for 1 hour. After a sodium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0) rinse, sections were reacted with nickel-enhanced diaminobenzidine (0.06%) and glucose oxidase, rinsed extensively with acetate buffer, dehydrated, and coverslipped.

ChAT immunocytochemistry

To identify the cholinergic SPNs, PPNs, and somatic motor neurons, we localized the acetylcholine-synthesizing enzyme ChAT with a polyclonal antiserum (Table 1). We used the protocol described above, except that Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 0.1 M Tris, 1.4% NaCl, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4) was used, a presoak (15 minutes) in 0.8% Triton X-100 was added, and 3% normal horse serum and biotinylated anti-goat IgG (1:200; Vector Elite Goat Kit) were substituted.

Morphometric analysis

To quantify the distances that SPNs and PPNs migrated in Lis1+/+ and Lis1+/− mice during development (E13.5–P0), we measured: 1) the dorsoventral extent of the preganglionic neurons (Table 2, dSPN); and 2) the distance between the ventral edge of the preganglionic neurons and the dorsal edge of the somatic motor neurons (Table 2, dSPN-SMN). These measurements were performed blind to the genotype. The distances, reported in Table 2, were normalized with respect to the total dorsal-ventral gray matter length to account for variation in spinal cord size. Thus a smaller ratio reflects a shorter proportional length of the preganglionic neurons or distance between the preganglionic and somatic motor neurons. We identified “outliers” as individual neurons widely separated from the group, and excluded them from these measurements. The mean was obtained for Lis1+/+ and Lis1+/− mice, and statistical significance was evaluated with a Student’s t-test.

TABLE 2.

Morphometric Analysis of SPNs and PPNs1

| Age | Dorsoventral length of SPNs (dSPN) | Distance between SPNs and SMNs (dSPN-SMN) | Dorsoventral length of PPNs (dPPN) | Distance between PPNs and SMNs (dPPN-SMN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E13.5 | ||||

| +/+ | 0.208 ± 0.005 | 0.081 ± 0.007 | 0.244 ± 0.039 | nd |

| +/− | 0.266 ± 0.004** | 0.029 ± 0.004** | 0.295 ± 0.017 | nd |

| E14.5 | ||||

| +/+ | 0.138 ± 0.003 | 0.211 ± 0.004 | 0.119 ± 0.006 | 0.274 ± 0.022 |

| +/− | 0.246 ± 0.006** | 0.080 ± 0.008** | 0.203 ± 0.011** | 0.168 ± 0.030* |

| E17.5 | ||||

| +/+ | 0.112 ± 0.003 | 0.270 ± 0.006 | 0.137 ± 0.006 | 0.464 ± 0.006 |

| +/− | 0.218 ± 0.007** | 0.132 ± 0.006** | 0.221 ± 0.008** | 0.322 ± 0.012** |

| P0 | ||||

| +/+ | 0.104 ± 0.003 | 0.322 ± 0.008 | 0.152 ± 0.008 | 0.521 ± 0.019 |

| +/− | 0.275 ± 0.146** | 0.182 ± 0.011** | 0.304 ± 0.025** | 0.329 ± 0.026** |

Abbreviations: PPN, parasympathetic preganglionic neuron; SMN, somatic motor neuron; SPN, sympathetic preganglionic neuron; nd, not done (unable to measure due to indistinct boundaries between neuronal populations).

All distances were normalized with respect to the total gray matter length along the dorsoventral axis to account for developmental variation in spinal cord sizes.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.0001.

Digital photomicrographs were taken with a Zeiss Axio-Cam camera (Thornwood, NY) with Openlab 4.0.4 software (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) on an Olympus AX70 microscope (Center Valley, PA). Images were transferred into Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), and the brightness and contrast were adjusted on individual images.

RESULTS

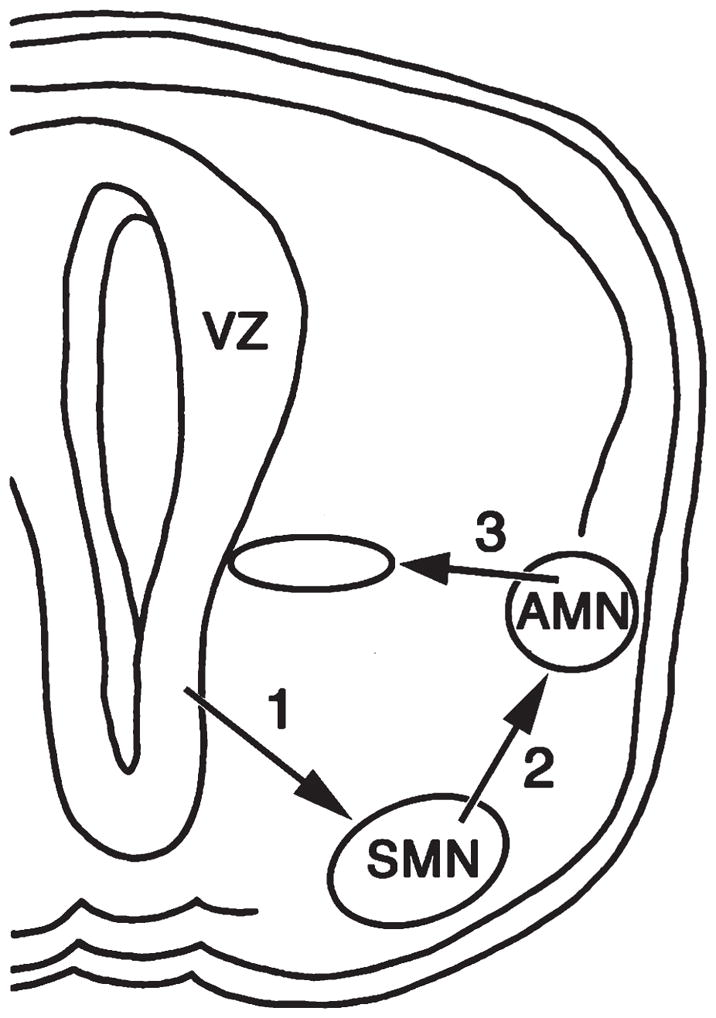

Both groups of autonomic motor neurons (AMNs), the sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons (SPNs and PPNs, respectively), undergo a complex pattern of radial and tangential movements to achieve their final positions in the thoracic and sacral spinal cord. Previous studies (Phelps et al., 1991, 1993, 2002; Yip et al., 2000) report that AMNs and somatic motor neurons (SMNs) translocate together from the ventricular zone to the ventral lateral spinal cord in the first wave of radial migration (Fig. 1, arrow 1). Generally SMNs remain ventrally positioned as AMNs undergo a secondary tangential migration dorsally into the intermediolateral horn (Fig. 1, arrow 2). All PPNs and most SPNs remain laterally, except for the SPNs that migrate medially to form the intercalated and central autonomic groups (Fig. 1, arrow 3). Neurons throughout the ventral spinal cord express high levels of Lis1 (Reiner et al., 1995) during the time of the SPN and PPN migrations, and therefore we asked whether there were migratory defects present in Lis1+/− mice. We first examined the embryonic development of nNOS-labeled SPNs and PPNs and then identified the cholinergic neurons to differentiate the tangential migration of SPNs and PPNs from ventral SMNs.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the migratory pattern of sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons, also termed spinal autonomic motor neurons (AMNs). Together, autonomic and somatic motor neurons (SMNs) are generated in the ventricular zone (VZ) and migrate radially into the ventral horn along the pathway marked by arrow 1. The SMNs remain ventrally as the AMNs migrate dorsally along a tangential pathway (arrow 2) to reach the intermediolateral horn. A limited number of sympathetic preganglionic neurons then migrate medially along the radial pathway marked by arrow 3.

Sympathetic preganglionic neuron migration is aberrant in Lis1+/− mice

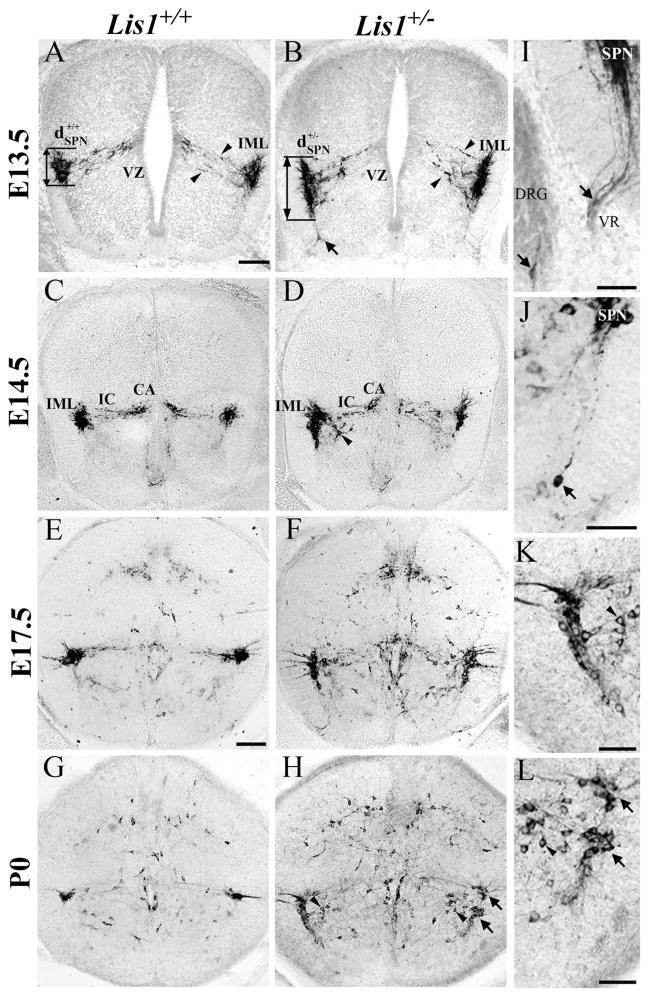

At E13.5, most nNOS-positive SPNs in Lis1+/+ mice are located near the intermediolateral horn (IML) and have dendritic processes projecting medially (Fig. 2A). Wild-type SPNs consolidate into a compact group in the IML on E14.5 (Fig. 2C), and by E17.5–P0 (Fig. 2E,G) display an adult-like morphology. In contrast, the dorsoventral distance (Fig. 2, dSPN) occupied by E13.5 Lis1+/− SPNs is greater than that seen in Lis1+/+ SPNs (Table 2; *P < 0.0001). The average dorsoventral length of the IML nucleus in Lis1+/− mice remains significantly longer than the wild-type IML throughout embryonic development, and at birth is more than 2.5 times the length of the Lis1+/+ IML (Fig. 2D,F,H; Table 2; *P < 0.0001). The medially projecting dendrites of Lis1+/− SPNs also occupy a wider dorsoventral distance (Fig. 2B, between arrowheads) than is typical of Lis1+/+ SPNs (Fig. 2A, between arrowheads).

Figure 2.

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS)-labeled Lis1+/− sympathetic preganglionic neurons (SPNs) have migratory defects. A,B: E13.5 Lis1+/+ SPNs (A, ) aggregate near the intermediolateral horn (IML), whereas Lis1+/− SPNs are distributed dorsoventrally (B, ). Lis1+/− SPNs have widespread processes (B, between arrowheads) that do not yet contact the ventricular zone (VZ) as seen in Lis1+/+ mice. Isolated nNOS-positive cell (B, arrow) is found deep in the Lis1+/− ventral horn. C–H: Most Lis1+/+ SPNs (E14.5, C; E17.5, E; P0, G) are found in the IML, and intercalated (IC) and central autonomic (CA) cells are correctly positioned. Some Lis1+/− SPNs at E14.5 (D), E17.5 (F), and P0 (H) are located in the IML whereas others are mispositioned along the tangential migratory pathway (D,F,H) or found ventromedially (H, arrowheads). I: Mispositioned E13.5 SPNs are detected in Lis1+/− dorsal root ganglion (DRG, arrow) and the ventral root (VR, arrow). J: Isolated P0 Lis1+/− SPN (arrow) is located in the deep ventral horn, widely separated from other SPNs. K,L: Enlargements of H show nNOS-labeled somata of Lis1+/− SPNs in normal (upper arrow) and ectopic (lower arrow) positions (same arrows as H). Ventromedial SPNs (arrowheads) are also mispositioned. Scale bar = 100 μm in A (applies to A–D) and E (applies to E–H); 50 μm in I–L.

Many mispositioned nNOS-positive SPNs in Lis1+/− spinal cords were found in locations that suggest their tangential migration was slowed and perhaps terminated prematurely. Ectopic SPNs are detected as early as E13.5 and remain at P0. We found nNOS-labeled Lis1+/− SPNs located in the ventral horn and all along their tangential migratory trajectory. Some of these nNOS-positive cell bodies are found deep in the ventral horn, with leading processes oriented dorsally (Fig. 2B,J, arrows). At older ages, SPNs could be divided into two groups, those correctly positioned in the IML (Fig. 2H,L, upper arrows) and a second population found ventrally along the tangential migratory pathway (Fig. 2H,L, lower arrows). In addition, some nNOS-positive SPNs are mispositioned ventromedially to the IML (Fig. 2H,K,L, arrowheads). That is, they appear to have started their final medial migration, but remain too far ventral to contribute to the intercalated (IC) or central autonomic (CA) groups (Fig. 2H,L, arrowheads). This finding suggests that some SPNs in Lis1+/− mice do not complete their migration in both the dorsal and subsequent medial directions. Finally, we found rare nNOS-labeled cell bodies with differentiated processes in the ventral root and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of Lis1+/− animals (Fig. 2I, arrows). These ectopic SPNs were found at E13.5 and E14.5, but not at later ages.

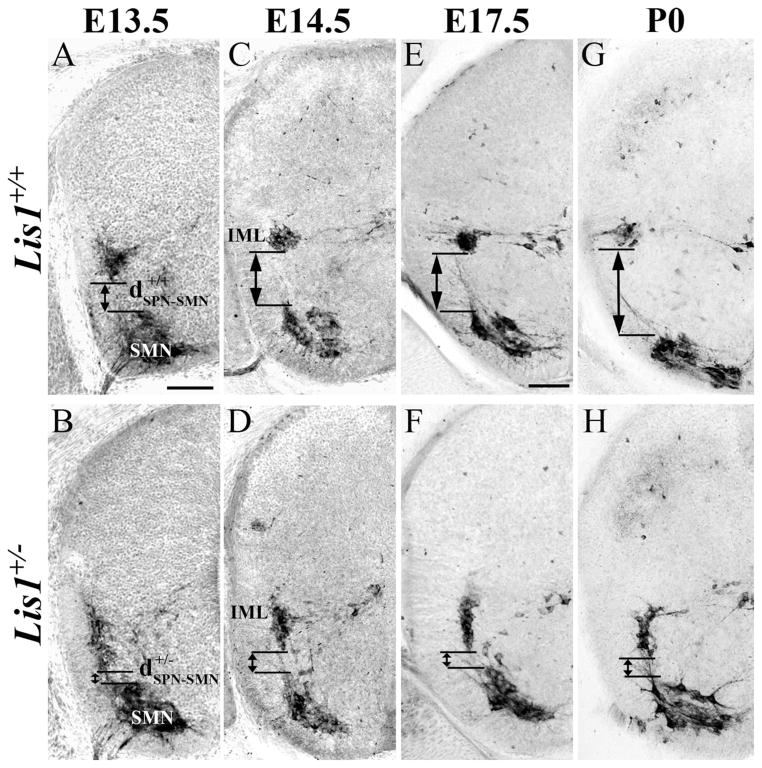

The separation between SPNs and SMNs is another measure of the extent of SPN tangential migration. We therefore measured the distance between these two populations (Fig. 3, dSPN-SMN) in sections processed for ChAT immunocytochemistry. The distance between the SPNs and SMNs is significantly greater (Table 2, *P < 0.0001) in Lis1+/+ than in Lis1+/− mice at each developmental time point studied (Fig. 3A–H). By birth, the normalized distance between these cholinergic populations in Lis1+/− spinal cord is only 57% of that observed in wild-type mice. These results provide further evidence that a substantial number of SPNs do not complete their migration and are mispositioned ventrally.

Figure 3.

Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-positive Lis1+/− sympathetic preganglionic (SPNs) and somatic motor neurons (SMNs) do not separate completely during development. A,C,E,G: E13.5 (A), 14.5 (C), 17.5 (E), and P0 (G) Lis1+/+ SPNs are found in the intermediolateral horn (IML). As development proceeds, the distance between the SPNs and SMNs increases (A, ). B,D,F,H: The separation between SPNs and SMNs is smaller in E13.5 Lis1+/− (B, ) than in Lis1+/+ mice and also at E14.5 (D), E17.5 (F), and P0 (H). Scale bar = 100 μm in A (applies to A–H).

Parasympathetic preganglionic neuron migration is aberrant in Lis1+/− mice

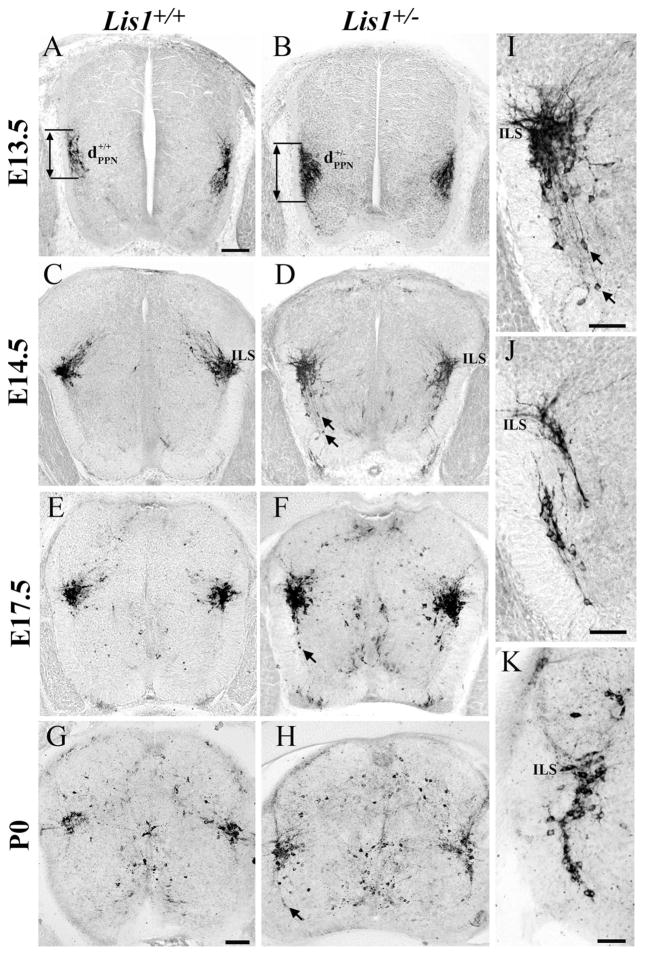

At E13.5, the position and distribution of nNOS-positive PPNs are similar in both genotypes (Fig. 4A,B). These groups of PPNs are elongated and have not yet reached the intermediolateral sacral nucleus (ILS). Morphometric analysis confirms no differences in the dorsoventral length (dPPN) of these nNOS-labeled neurons between Lis1+/+ and Lis1+/− mice at this age (Table 2, *P = 0.11).

Figure 4.

nNOS-positive Lis1+/− parasympathetic neurons (PPNs) have migratory errors. A,B: On E13.5 both Lis1+/+ (A, ) and Lis1+/− (B, ) PPNs formed elongated nuclei. C,D: By E14.5 the intermediolateral sacral horn (ILS) contained PPNs in both genotypes. Ventrally positioned nNOS-positive SPNs (arrows) with dorsally oriented processes were present only in Lis1+/− spinal cords (enlargement in I). E–H: E17.5 (E) and P0 (G) Lis1+/+ PPNs are similar, whereas this cell group in Lis1+/− mice (F,H) is more elongated and outliers (arrows) are detected ventrally. I–K: Lis1+/− PPNs exhibit different arrangements of ectopically positioned cells: individual outliers with long processes oriented toward the ILS (I, enlarged from D), multiple groups of PPNs (J, shown at E14.5), and PPNs found all along the migratory pathway (K, shown at P0). Scale bar = 100 μm in A (applies to A–F) and G (applies to G,H); 50 μm in I–K.

By E14.5, Lis1+/+ PPNs form a compact group in the ILS region and their dendritic processes extend dorsomedially (Fig. 4C). In contrast, migratory abnormalities reminiscent of those seen in Lis1+/− SPNs are evident in Lis1+/− PPNs. Compared with Lis1+/+, groups of E14.5, E17.5, and P0 Lis1+/− PPNs are elongated dorsoventrally (Fig. 4C–H; Table 2, E14.5, 17.5, and P0 comparisons, *P < 0.0001). Many nNOS-positive cell bodies remain along the tangential migratory pathway, again suggesting their migration is slowed and incomplete (Fig. 4D,F,H,I, arrows). This defect manifests in three ways: 1) as individual PPNs isolated in the ventral horn (Fig. 4D,F,I, arrows); 2) as two separate groups of PPNs, one of which is clearly mispositioned ventrally (Fig. 4J); and 3) as a continuous group of PPNs located between the ventral horn and the ILS (Fig. 4K).

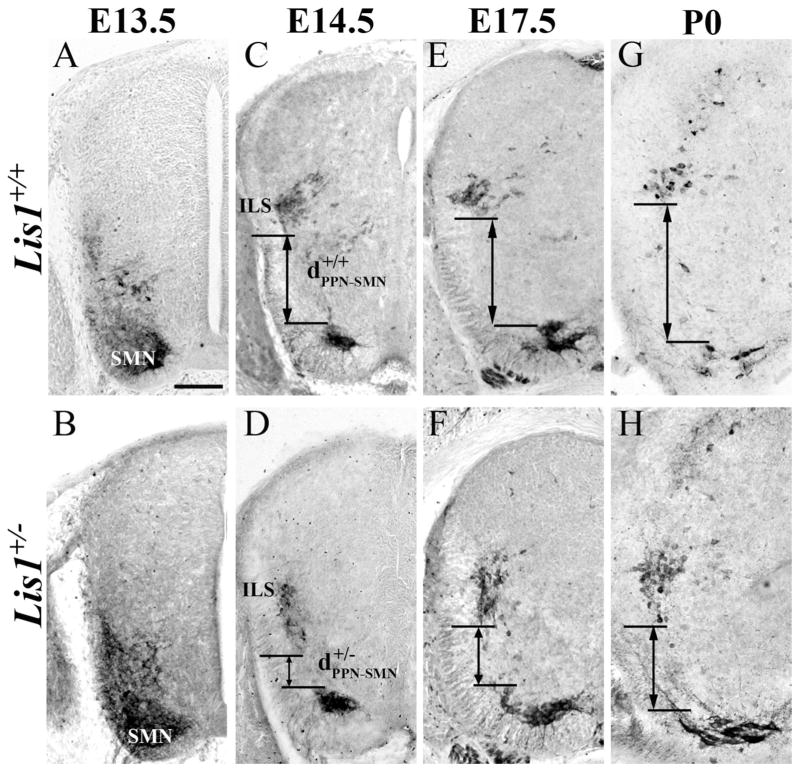

The boundaries between ChAT-positive SMNs and PPNs are indistinct at E13.5 in both genotypes and therefore not included in our statistical analysis (Fig. 5A,B). At E14.5, 17.5, and P0 (Fig. 5C–H), however, our measurements confirm that the distance between PPNs and SMNs (Fig. 5, dPPN-SMN) is significantly greater in Lis1+/+ than in Lis1+/− mice (Table 2, *P < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-positive parasympathetic preganglionic (PPNs) and somatic motor neurons (SMNs) do not completely separate in Lis1+/− mice. A,B: On E13.5 the ChAT-positive cells in the ventral spinal cord form a continuous group in Lis1+/+ and Lis1+/− mice. C,E,G: Lis1+/+ PPNs reach the sacral intermediolateral horn (ILS) by E14.5 (C, ). The distance between PPNs and SMNs continues to increase at E17.5 (E) and P0 (G). D,F,H: On E14.5 some Lis1+/− PPNs (D, ) are found in the ILS with others scattered further ventrally. On E17.5 (F) and P0 (H) the Lis1+/− PPNs remain more widespread and closer to the SMNs than wild-type PPNs. Scale bar = 100 μm in A (applies to A–F).

Some preganglionic neurons cease migration prematurely

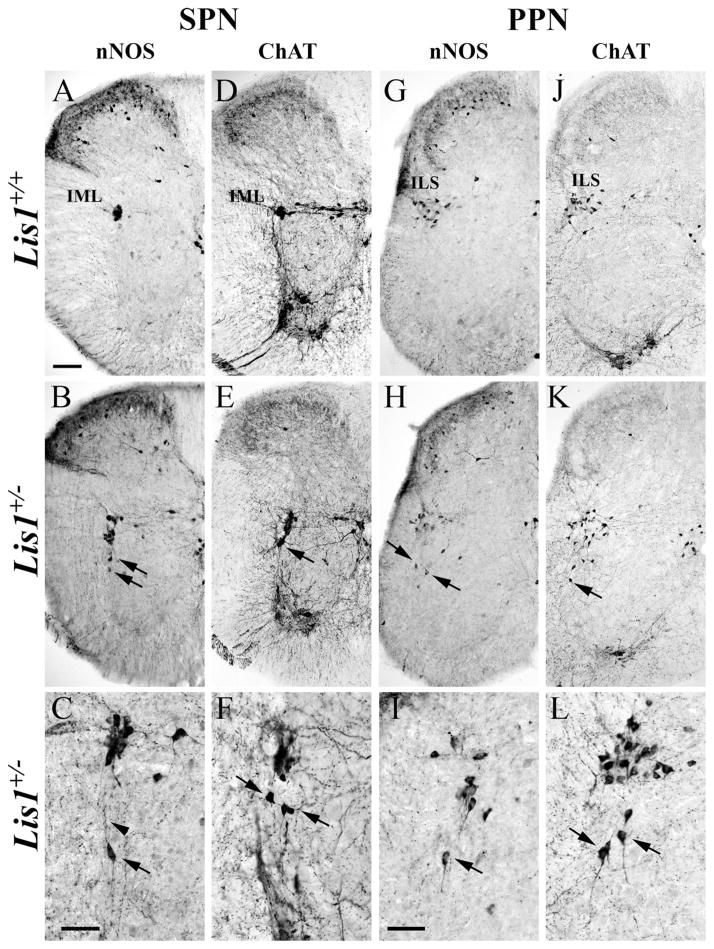

SPNs and PPNs are among the earliest born neurons in the rodent spinal cord (Nornes and Carry, 1978; Barber et al., 1991; Yip et al., 2004b) and complete their rather complex migration early during spinal cord development (Phelps et al., 1991, 2002; Yip et al., 2000, 2003a). To determine whether ectopic preganglionic neurons detected in P0 Lis1+/− spinal cord would eventually migrate into the intermediate horn, we evaluated their positions 1 month later. Lis1+/+ nNOS- and ChAT-labeled SPNs occupy the IML as expected (Fig. 6A,D), but a number of Lis1+/− SPNs are still found ventrally (Fig. 6B,C,E,F, arrows), and a few have dorsally directed processes (Fig. 6C, arrowhead). Similarly, Lis1+/+ PPNs are correctly located (Fig. 6G,J), whereas some Lis1+/− PPNs are found ventrally along their original migratory pathway (Fig. 6H,I,K,L). As ectopic preganglionic neurons are maintained in the Lis1+/− spinal cord between P0 and P30, they are likely to be permanently mispositioned.

Figure 6.

Mispositioned sympathetic (SPNs) and parasympathetic (PPNs) preganglionic neurons persist in P30 Lis1+/− spinal cord sections and are identified with nNOS (A–C,G–I) and ChAT (D–F,J–L) antisera. A,D: In Lis1+/+ mice, nNOS- and ChAT-positive SPNs are found in the intermediolateral horn (IML). B–C,E–F: Lis1+/− SPNs in multiple sections are correctly positioned in the IML, but others are mispositioned ventrally (arrows) with dorsally oriented processes (C, arrowhead). G,J: In Lis1+/+ mice, nNOS- and ChAT-positive PPNs are concentrated in the intermediolateral sacral horn (ILS). H–I,K–L: Different sacral sections of Lis1+/− spinal cords illustrate incorrectly positioned PPNs (arrows) at lower (H,K) and higher (I,L) magnifications. Scale bar = 100 μm in A (applies to A,B,D,E,G,H,J,K); 50 μm in C (applies to C,F); 50 μm in I (applies to I,L).

Retrodorsolateral somatic motor neuron location is aberrant in Lis1+/− mice

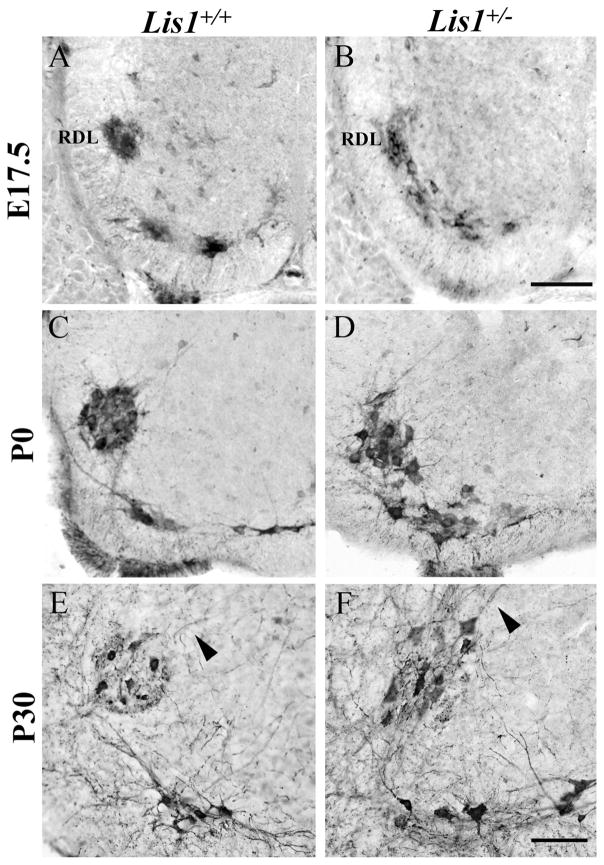

Most SMNs remain ventrally positioned after their movement from the ventricular zone. The SMNs that innervate the intrinsic muscles of the hindpaw, however, move a short distance dorsally to form the prominent retrodorsolateral (RDL) nucleus that characterizes the L6 spinal cord segment (Schroder, 1980; Micevych et al., 1986). As this movement resembles the tangential phase of the SPN and PPN migrations, we asked if the neurons in the RDL nucleus would be affected by the loss of a single Lis1 allele. In E17.5 Lis1+/+ mice, ChAT-positive neurons in the RDL form a distinct circular nucleus (Fig. 7A), whereas those in Lis1+/− spinal cords remain distributed along their dorsal trajectory, with no clear separation from the ventrally positioned SMNs (Fig. 7B). By P0, RDL neurons in Lis1+/+ mice are in a tightly condensed circle, whereas those in Lis1+/− mice remain disorganized and loosely aggregated (Fig. 7C,D).

Figure 7.

The retrodorsolateral group (RDL) of ChAT-positive somatic motor neurons (SMNs) is mispositioned in Lis1+/− lumbar spinal cord. A,B: On E17.5 the Lis1+/+ RDL nucleus (A) forms a tightly packed, circular group of neurons, but in Lis1+/− spinal cord (B) these cells are not yet separated from the ventral SMNs. C,D: At P0, the Lis1+/+ RDL nucleus is circular (C), whereas in the Lis1+/− RDL these cells remain loosely organized and close to ventral SMNs (D). E,F: At P30, the Lis1+/+ RDL nucleus is circular, with dorsomedially projecting dendrites (E, arrowhead). The Lis1+/− RDL nucleus is more oval-shaped, with dorsally directed dendrites (F, arrowhead). Scale bar = 100 μm in B (applies to A–D) and F (applies to E–F).

Compared with the indistinct separation between the ventral and RDL SMNs at earlier ages, the Lis1+/− RDL nucleus clearly had separated in P30 spinal cord and now more closely resembled the Lis1+/+ nucleus (Fig. 7E,F). By P30, the Lis1+/− RDL nucleus was either circular (data not shown) or oval in shape (Fig. 7F) and displayed typical dorsomedially directed dendrites (Fig. 7F, arrowhead). Thus the organization of this distinct group of SMNs in Lis1+/− mice changed substantially during late embryonic development and in the first postnatal month.

DISCUSSION

Lis1 mediates tangential migration of SPNs and PPNs

This study found that SPNs and PPNs in Lis1+/− mice exhibit specific migratory errors. The initial wave of radial migration from the ventricular zone into the ventral horn appears normal, but a number of SPNs and PPNs exhibit a slowed tangential phase of their migration. At all ages studied, some preganglionic neurons were found too far ventral, and occasionally even deep within the ventral horn, presumably intermixed with SMNs. As a number of Lis1+/− SPNs and PPNs are still mispositioned at P30, we suggest that these cells prematurely ceased migration. These errors are likely due to inadequate levels of Lis1 and/or the Pafah1b complex that result in an inefficient coupling between Lis1 and dynein and subsequent defects in microtubule dynamics. Detection of mispositioned preganglionic neurons, some with long leading processes oriented along their dorsal migratory pathway, is consistent with an interpretation of incomplete nucleokinesis during tangential migration (Nasrallah et al., 2006). Interestingly, these findings seem to differ from those in the cerebral cortex, where both radial and tangential migrations are affected in Lis1+/− mice (Hirotsune et al., 1998; Nasrallah et al., 2006).

We also showed that the movement of SMNs that occupy the RDL nucleus is slowed and Lis1 dependent. SMNs migrate radially to reach their ventral positions, but RDL neurons also move a short distance tangentially to achieve a distinct, more dorsal location. As with the SPNs and PPNs, only the tangential component of the RDL location appears defective in Lis1+/− mice, but unlike the preganglionic neurons, the position of RDL neurons relative to the ventral SMNs changes later in embryonic development and continues to change postnatally. This dorsal shift in the position of RDL neurons may reflect a slowed migration of these SMNs or a slowed movement of other neurons and glia into the space between the ventral and more dorsal SMNs.

An advantage to studying genetic mutants is a precise control over the levels of Lis1 (Youn et al., 2009). The Lis1+/− mice express approximately 50% of the Lis1 protein in neurons compared with Lis1+/+ littermates (Hirotsune et al., 1998). The 50% levels of Lis1 expression are adequate for many SPNs and PPNs to achieve their correct adult positions, but insufficient for the somal migration of a subset of preganglionic neurons. Our results are reminiscent of the arrangement of hippocampal pyramidal neurons in Lis1+/− mice that have a bilaminar or broader than normal distribution (Hirotsune et al., 1998; Youn et al., 2009) and thus also may represent a mixture of correctly and incorrectly positioned neurons. Furthermore, patients with a LIS1 mutation may exhibit a subcortical band heterotopia, and thus have a combination of cortical neurons that fail to reach their final destination and a subset of cortical neurons that migrate normally (Guerrini and Parrini, 2010). These reports, together with our findings, suggest that some neurons may require more than 50% Lis1 expression levels to successfully complete their migration.

Lis1, Cdk5, and reeler mouse models provide clues to understanding multistep neuronal migrations

Errors in preganglionic neuron migration were reported in the spinal cords of cdk5 (Yip et al., 2007) and reeler mutants (Yip et al., 2000, 2003a; Phelps et al., 2002; Kubasak et al., 2004). Consistent with our results in the Lis1+/− spinal cord, the primary radial migration of cdk5 and reeler SPNs and PPNs from the ventricular zone to the ventrolateral spinal cord appears unaffected. Problems occur in the subsequent migration of SPNs and PPNs from the ventral spinal cord to their final positions, but the errors observed differ in each model. In cdk5−/− mice, all SPNs and PPNs are arrested in the ventral spinal cord adjacent to the SMNs (Yip et al., 2007), whereas only a portion of these cells do not reach their correct locations in Lis1+/− mice. In rl−/− mice, all SPNs and PPNs complete their tangential migration dorsally, but then do not stop in the IML and instead migrate toward the ventricular zone (Yip et al., 2000, 2003a; Phelps et al., 2002), probably along radial glia (Phelps et al., 1993). An unusual migratory error found in both rl−/− and Lis1+/− mice involves SPNs migrating out the ventral roots and into the dorsal root ganglia during embryonic development (Han et al., 2008).

Interestingly, both Cdk5 and the Reelin signaling pathway are proposed to interact with Lis1 (Niethammer et al., 2000; Assadi et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). During neuronal migration, the serine/threonine kinase Cdk5 phosphorylates Ndel1, which binds to both Lis1 and dynein, and together are necessary for nucleokinesis (Niethammer et al., 2000; Sasaki et al., 2000). Cdk5 also phosphorylates Doublecortin (Dcx), a microtubule-associated protein that localizes to the perinuclear cage and may regulate nuclear translocation in parallel with Lis1 (Tanaka et al., 2004b; reviewed in Tsai and Gleeson, 2005). Therefore, the impaired migration of preganglionic neurons in the ventral horn of cdk5−/− spinal cords (Yip et al., 2007) is consistent with the loss of phosphorylated Ndel1 and Dcx that leads to unstable Lis1-dynein interactions. In our study, the absence of a single Lis1 allele caused similar migratory errors in preganglionic neurons, but to a much lesser extent than in cdk5 null mice (Yip et al., 2007). Although both Lis1−/− and cdk5−/− mice are embryonic lethal (Ohshima et al., 1996; Hirotsune et al., 1998; Cahana et al., 2003), mice heterozygous for either gene deletion live well into adulthood, breed successfully, and have no reported functional deficits related to SPN or PPN migratory errors (Ohshima et al., 1996; Yip et al., 2007; current study).

The migration of SPNs and PPNs also depends on an intact Reelin signaling pathway (Yip et al., 2000; Phelps et al., 2002). Reelin binding to the very-low-density lipoprotein receptor (Vldlr) or apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (Apoer2) leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of Disabled-1 (Dab1; D’Arcangelo et al., 1999; Hiesberger et al., 1999) and the deletion of Reelin, Vldlr and Apoer2, or Dab1 all cause similar migratory defects in the SPNs (Yip et al., 2004a). There are both genetic and biochemical interactions between the Lis1/Pafah1b complex and the Reelin signaling pathway (Assadi et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2007, 2009). In compound heterozygous mice (Lis1+/− and Vldlr+/− or Dab1+/−) a higher incidence of hydrocephalus and more cortical lamination defects are observed than in single heterozygous mice (Assadi et al., 2003).

Lis1 regulates Pafah1b2 and Pafah1b3, the α catalytic subunits of the Pafah1b complex that, in addition to their function in platelet-activating factor hydrolysis, directly interact with the Vldlr receptor (Zhang et al., 2007, 2009). This interaction facilitates the binding of the Lis1 β subunit to phosphorylated Dab1, and may ultimately modulate microtubule dynamics (Zhang et al., 2007). When the migratory errors between Lis1+/− (current study) and rl−/− (Yip et al., 2000; Phelps et al., 2002) preganglionic neurons are compared, however, these genes are seen to act independently during preganglionic neuron migration as rl−/− SPNs and PPNs do not exhibit defects in nucleokinesis. Perhaps the interaction of the Pafah1b complex with Reelin signaling is related to a different function, such as leading process stabilization or regulation of dendritic development (Niu et al., 2004; Matsuki et al., 2008; Chameau et al., 2009; Gopal et al., 2010).

SPNs and PPNs have a complex migratory pattern that involves both radial and tangential components and thus is a useful model to dissect out the effects of individual gene deletions related to neuronal migration. Three genes, cdk5 (Yip et al., 2007), reeler (Yip et al., 2000, 2003a; Phelps et al., 2002), and Lis1 (current study), all mediate specific aspects of preganglionic neuron migration in mouse spinal cord, and their interconnected signaling pathways are required for normal migration. Furthermore, because Lis1 primarily disrupts the tangential migration of the preganglionic neurons, we propose that Lis1 specifically mediates tangential migration in these neurons.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ellen Carpenter for helpful suggestions and discussions throughout the study, Will Shapiro for breeding and genotyping the Lis1 mutant mice, and George Clement for preparation of the adult Lis1 mouse pairs.

Grant sponsor: National Science Foundation (NSF); Grant numbers: IBN-9734550 (to P.E.P.), IOS-0924143 (to P.E.P.); Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Grant number: RO1 NS45034 (to J.A.G.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Assadi AH, Zhang G, Beffert U, McNeil RS, Renfro AL, Niu S, Quattrocchi CC, Antalffy BA, Sheldon M, Armstrong DD, Wynshaw-Boris A, Herz J, D’Arcangelo G, Clark GD. Interaction of reelin signaling and Lis1 in brain development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:270–276. doi: 10.1038/ng1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber RP, Phelps PE, Vaughn JE. Generation patterns of immunocytochemically identified cholinergic neurons at autonomic levels of the rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1991;311:509–519. doi: 10.1002/cne.903110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blottner D, Baumgarten HG. Nitric oxide synthetase (NOS)-containing sympathoadrenal cholinergic neurons of the rat IML-cell column: evidence from histochemistry, immunohistochemistry, and retrograde labeling. J Comp Neurol. 1992;316:45–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.903160105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahana A, Escamez T, Nowakowski RS, Hayes NL, Giacobini M, von Holst A, Shmueli O, Sapir T, McConnell SK, Wurst W, Martinez S, Reiner O. Targeted mutagenesis of Lis1 disrupts cortical development and LIS1 homodimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6429–6434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101122598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahana A, Jin XL, Reiner O, Wynshaw-Boris A, O’Neill C. A study of the nature of embryonic lethality in LIS1−/− mice. Mol Reprod Dev. 2003;66:134–143. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chameau P, Inta D, Vitalis T, Monyer H, Wadman WJ, van Hooft JA. The N-terminal region of reelin regulates postnatal dendritic maturation of cortical pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7227–7232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810764106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T. Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron. 1999;24:471–479. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobyns WB, Reiner O, Carrozzo R, Ledbetter DH. Lissencephaly. A human brain malformation associated with deletion of the LIS1 gene located at chromosome 17p13. JAMA. 1993;270:2838–2842. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.23.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun NJ, Dun SL, Wu SY, Forstermann U, Schmidt HH, Tseng LF. Nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in the rat, mouse, cat and squirrel monkey spinal cord. Neurosci. 1993;54:845–857. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Olson EC, Stukenberg PT, Flanagan LA, Kirschner MW, Walsh CA. LIS1 regulates CNS lamination by interacting with mNudE, a central component of the centrosome. Neuron. 2000;28:665–679. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambello MJ, Darling DL, Yingling J, Tanaka T, Gleeson JG, Wynshaw-Boris A. Multiple dose-dependent effects of Lis1 on cerebral cortical development. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1719–1729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01719.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal PP, Simonet JC, Shapiro W, Golden JA. Leading process branch instability in Lis1+/− nonradially migrating interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:1497–1505. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Parrini E. Neuronal migration disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;38:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JM, Hirose M, Basbaum AI, Phelps PE. Aberrant migration of sympathetic preganglionic neurons into the dorsal root ganglia of reeler and dab1 mutant mice. Soc Neurosci Abst. 2008:230.10. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M, Adachi H, Tsujimoto M, Arai H, Inoue K. Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene encodes a subunit of brain platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase [corrected] Nature. 1994;370:216–218. doi: 10.1038/370216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesberger T, Trommsdorff M, Howell BW, Goffinet A, Mumby MC, Cooper JA, Herz J. Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation. Neuron. 1999;24:481–489. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsune S, Fleck MW, Gambello MJ, Bix GJ, Chen A, Clark GD, Ledbetter DH, McBain CJ, Wynshaw-Boris A. Graded reduction of Pafah1b1 (Lis1) activity results in neuronal migration defects and early embryonic lethality. Nat Genet. 1998;19:333–339. doi: 10.1038/1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubasak MD, Brooks R, Chen S, Villeda SA, Phelps PE. Developmental distribution of Reelin-positive cells and their secreted product in the rodent spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:165–178. doi: 10.1002/cne.10946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Nigro C, Chong CS, Smith AC, Dobyns WB, Carrozzo R, Ledbetter DH. Point mutations and an intragenic deletion in LIS1, the lissencephaly causative gene in isolated lissencephaly sequence and Miller-Dieker syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:157–164. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcorelles P, Laquerriere A, Adde-Michel C, Marret S, Saugier-Veber P, Beldjord C, Friocourt G. Evidence for tangential migration disturbances in human lissencephaly resulting from a defect in LIS1, DCX and ARX genes. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;210:503–515. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0692-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki T, Pramatarova A, Howell BW. Reduction of Crk and CrkL expression blocks reelin-induced dendritogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1869–1875. doi: 10.1242/jcs.027334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus MF, Nasrallah IM, Pancoast MM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Golden JA. Lis1 is necessary for normal non-radial migration of inhibitory interneurons. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:775–784. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63340-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micevych PE, Coquelin A, Arnold AP. Immunohisto-chemical distribution of substance P, serotonin, and methionine enkephalin in sexually dimorphic nuclei of the rat lumbar spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1986;248:235–244. doi: 10.1002/cne.902480206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah IM, McManus MF, Pancoast MM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Golden JA. Analysis of non-radial interneuron migration dynamics and its disruption in Lis1+/− mice. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496:847–858. doi: 10.1002/cne.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer M, Smith DS, Ayala R, Peng J, Ko J, Lee MS, Morabito M, Tsai LH. NUDEL is a novel Cdk5 substrate that associates with LIS1 and cytoplasmic dynein. Neuron. 2000;28:697–711. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu S, Renfro A, Quattrocchi CC, Sheldon M, D’Arcangelo G. Reelin promotes hippocampal dendrite development through the VLDLR/ApoER2-Dab1 pathway. Neuron. 2004;41:71–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00819-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nornes HO, Carry M. Neurogenesis in spinal cord of mouse: an autoradiographic analysis. Brain Res. 1978;159:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima T, Ward JM, Huh C-G, Longenecker G, Veeranna, Pant HC, Brady RO, Martin LJ, Kulkarni AB. Targeted disruption of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 gene results in abnormal corticogenesis, neuronal pathology, and perinatal death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11173–11178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancoast ML, Dobyns WB, Golden JA. Interneuron deficits in patients with the Miller-Dieker syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:400–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0979-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps PE, Barber RP, Vaughn JE. Embryonic development of choline acetyltransferase in thoracic spinal motor neurons: somatic and autonomic neurons may be derived from a common cellular group. J Comp Neurol. 1991;307:77–86. doi: 10.1002/cne.903070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps PE, Barber RP, Vaughn JE. Embryonic development of rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons: possible migratory substrates. J Comp Neurol. 1993;330:1–14. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps PE, Rich R, Dupuy-Davies S, Rios Y, Wong T. Evidence for a cell-specific action of Reelin in the spinal cord. Dev Biol. 2002;244:180–198. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner O, Carrozzo R, Shen Y, Wehnert M, Faustinella F, Dobyns WB, Caskey CT, Ledbetter DH. Isolation of a Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene containing G protein beta-subunit-like repeats. Nature. 1993;364:717–721. doi: 10.1038/364717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner O, Albrecht U, Gordon M, Chianese KA, Wong C, Galgerber O, Sapir T, Siracusa LD, Buchberg AM, Caskey CT, Eichele G. Lissencephaly gene (LIS1) expression in the CNS suggests a role in neuronal migration. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3730–3738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03730.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Shionoya A, Ishida M, Gambello MJ, Yingling J, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hirotsune S. A LIS1/NUDEL/cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain complex in the developing and adult nervous system. Neuron. 2000;28:681–696. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder HD. Organization of the motoneurons innervating the pelvic muscles of the male rat. J Comp Neurol. 1980;192:567–587. doi: 10.1002/cne.901920313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu T, Ayala R, Nguyen MD, Xie Z, Gleeson JG, Tsai LH. Ndel1 operates in a common pathway with LIS1 and cytoplasmic dynein to regulate cortical neuronal positioning. Neuron. 2004;44:263–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Serneo FF, Higgins C, Gambello MJ, Wynshaw-Boris A, Gleeson JG. Lis1 and doublecortin function with dynein to mediate coupling of the nucleus to the centrosome in neuronal migration. J Cell Biol. 2004a;165:709–721. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Serneo FF, Tseng HC, Kulkarni AB, Tsai LH, Gleeson JG. Cdk5 phosphorylation of doublecortin ser297 regulates its effect on neuronal migration. Neuron. 2004b;41:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J-W, Bremner KH, Vallee RB. Dual subcellular roles for LIS1 and dynein in radial neuronal migration in live brain tissue. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:970–979. doi: 10.1038/nn1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LH, Gleeson JG. Nucleokinesis in neuronal migration. Neuron. 2005;46:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeda SA, Akopians AL, Babayan AH, Basbaum AI, Phelps PE. Absence of Reelin results in altered nociception and aberrant neuronal positioning in the dorsal spinal cord. Neurosci. 2006;139:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynshaw-Boris A. Lissencephaly and LIS1: insights into the molecular mechanisms of neuronal migration and development. Clin Genet. 2007;72:296–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynshaw-Boris A, Pramparo T, Youn YH, Hirotsune S. Lissencephaly: mechanistic insights from animal models and potential therapeutic strategies. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:823–830. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yingling J, Youn YH, Darling D, Toyo-oka K, Pramparo T, Hirotsune S, Wynshaw-Boris A. Neuroepithelial stem cell proliferation requires LIS1 for precise spindle orientation and symmetric division. Cell. 2008;132:474–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip JW, Yip YP, Nakajima K, Capriotti C. Reelin controls position of autonomic neurons in the spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8612–8616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150040497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YP, Capriotti C, Yip JW. Migratory pathway of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in normal and reeler mutant mice. J Comp Neurol. 2003a;460:94–105. doi: 10.1002/cne.10634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YP, Rinaman L, Capriotti C, Yip JW. Ectopic sympathetic preganglionic neurons maintain proper connectivity in the reeler mutant mouse. Neurosci. 2003b;118:439–450. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YP, Capriotti C, Magdaleno S, Benhayon D, Curran T, Nakajima K, Yip JW. Components of the Reelin signaling pathway are expressed in the spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2004a;470:210–219. doi: 10.1002/cne.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YP, Zhou G, Capriotti C, Yip JW. Location of preganglionic neurons is independent of birthdate but is correlated to reelin-producing cells in the spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2004b;475:564–574. doi: 10.1002/cne.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YP, Capriotti C, Drill E, Tsai LH, Yip JW. Cdk5 selectively affects the migration of different populations of neurons in the developing spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:297–307. doi: 10.1002/cne.21377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YP, Mehta N, Magdaleno S, Curran T, Yip JW. Ectopic expression of reelin alters migration of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:260–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn YH, Pramparo T, Hirotsune S, Wynshaw-Boris A. Distinct dose-dependent cortical neuronal migration and neurite extension defects in Lis1 and Ndel1 mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15520–15530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4630-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Assadi AH, McNeil RS, Beffert U, Wynshaw-Boris A, Herz J, Clark GD, D’Arcangelo G. The Pafah1b complex interacts with the reelin receptor VLDLR. PLoS One. 2007;2:e252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Assadi AH, Roceri M, Clark GD, D’Arcangelo G. Differential interaction of the Pafah1b alpha subunits with the Reelin transducer Dab1. Brain Res. 2009;1267:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]