Introduction

"Torsades de pointes" (TdP) ventricular tachycardias carry a high risk of sudden death, even when they occur in individuals with a structurally normal heart, in the absence of myocardial ischemia or prolonged QT interval. Leenhardt et al1 described a new syndrome with these characteristics in 1994 that showed a difference in which the TdP were triggered by ventricular extrasystoles (VE) with ultra-short coupling interval (< 300 ms).

Although this condition is easily diagnosed by the described characteristics, there is a lack of data on the clinical management of patients during the phase of electrical storm and during long-term clinical outcome. Over the past 20 years, three patients were identified in our institution with this clinical condition, as well as a family member with VE and short coupling interval, asymptomatic and without documented polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT).

The aim of this case report is to describe the clinical management used in these patients and review the literature on the implication of the finding of VE with short coupling interval in asymptomatic family members.

Case Reports

Case 1

Female patient, 20 years of age, started to have rhythmic palpitations, initially well tolerated and self-limited in August 1993, at the same time when she had depression due to the loss of a family member. In the same month she had an episode of loss of consciousness with sphincter release that lasted approximately 10 minutes, followed by spontaneous recovery with no physical trauma. During the evolution, she started to have several episodes of short-duration palpitations. Three months later, she reported a new episode of convulsive syncope lasting approximately 8 minutes, after which hospitalization was indicated for investigation. On the same night she was hospitalized, she had an episode of cardiac arrest in ventricular fibrillation rhythm, and underwent cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The investigation showed no evidence of structural heart disease; cardiac chamber showed preserved dimensions (LV = 47/29 mm, LVEF = 76 %; Aorta = 29 mm; LA = 27 mm, RV = 20 mm; septum and posterior wall = 8 mm each and preserved biventricular function, no segmental contractility alterations and no valvular dysfunction).

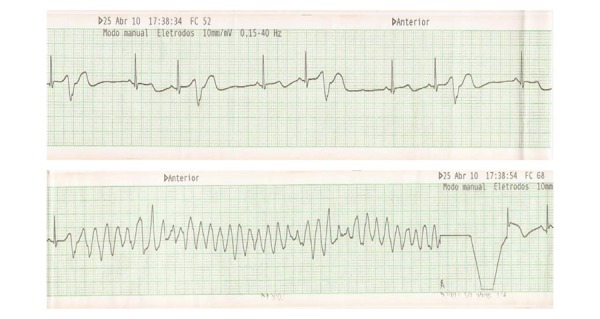

The 24-hour Holter showed VE with ultra-short coupling interval (260 ms) inducing episodes of non-sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia - Figure 1. The 12-lead electrocardiogram showed no alterations, the QT interval was 360 ms and QTc was 390 ms. The exercise stress test was negative for myocardial ischemia with no arrhythmia at rest or upon exertion. Coronary angiography was normal. The high-resolution electrocardiogram showed no late potentials. We performed an electrophysiological study (EPS), which showed normal basic intervals and did not induce arrhythmias when programmed ventricular stimulation was performed in the apex and right ventricular outflow tract, as well as using 'short-long-short' cycles for induction of VT/VF during sensitization with isoproterenol. The patient started to receive verapamil 80 mg every 8 hours and received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

Figure 1.

24-hour Holter: A. Extrasystole with ultrashort coupling interval (260 ms). B. Episode of non-sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia initiated by extrasystoles with short-coupling interval.

The patient needed psychological counseling after these events. During follow-up, she still had episodes of non-sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, seen at the 24-hour Holter, requiring a dose of 480 mg/day of verapamil to control the arrhythmia. She then remained asymptomatic for several years, although the 24-hour Holter still showed VE with short-coupling interval (260 ms). Seventeen years after the diagnosis and two ICD generator replacements, the patient received adequate defibrillator therapy; during an evaluation, she reported poor compliance to treatment with calcium channel blockers. At follow-up, she showed no significant emotional alterations, ischemic changes or ventricular function worsening.

Case 2

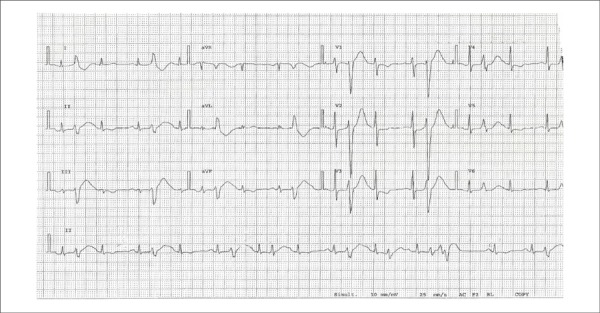

Female patient, 52 years old, admitted at another service due to episodes of recurrent syncope in 2010. At the time, she had suffered the recent loss of a son in a car accident and was drinking a type of "tea for weight loss." The electrocardiographic monitoring showed episodes of rapid ventricular tachycardia (Figures 2A and 2B). Within hours, the patient developed electrical storm and needed defibrillation for more than 50 times during a 24-hour period, requiring sedation and orotracheal intubation. An attempt was made to suppress the arrhythmias with isoproterenol, which was not successful.

Figure 2A.

Electrical Storm - Moment of electrical cardioversion with 200 J and Torsades de Pointes reversal to sinus rhythm

Figure 2B.

12-lead ECG with extrasystole and short coupling interval (280 ms)

Recurrence was observed in less than 6 hours after the start of drug infusion. A temporary pacemaker was implanted in the right ventricle, performed on stimulation without arrhythmia suppression. She was clinically stable after 48 hours of deep sedation and administration of verapamil at a dose of 240 mg/day.

The investigation showed no structural heart disease at the echocardiography, MRI and coronary angiography. The 24-h Holter monitoring, performed after crisis stabilization, showed 960 VE/24 h, with several of them showing short coupling (+/- 280 ms) and the same morphology. There were no tachycardias. At the ECG, the QTc was 400 ms. Electrophysiological mapping and attempted VE ablation were not successful. The scarcity of extrasystoles during the procedure did not induce arrhythmias when programmed ventricular stimulation was performed in the apex and right ventricular outflow tract, as well as using 'short-long-short' cycles for of VT/ VF induction under sensitization with isoproterenol. ICD implantation was indicated and treatment with verapamil was maintained. The patient remains asymptomatic during the two-year follow-up.

Case 3

This is an asymptomatic, 18-year-old woman, the daughter of the patient described in case # 2. During family screening, she was diagnosed with VE with a coupling of approximately 300 ms (17 extrasystoles in 24 h) during a 24-h Holter monitoring. Because the patient was asymptomatic and due to the low-density VE, it was decided to prescribe verapamil 160 mg/day and keep her on frequent clinical monitoring. She remains asymptomatic after a follow-up period of 48 months.

Case 4

Female patient, 39 years old, with episodes of syncope preceded by sudden and fast malaise, without trauma and unrelated to exertion, some occurring at night, during sleep, at an approximate frequency of three times a week since March 2011. She sought medical attention a few times, having been diagnosed with anxiety and prescribed anxiolytics, with no improvement of symptoms and worsening of anxiety. On 07/10/2011, she had recurrence of syncope, with characteristics similar to those described, when she was admitted at another hospital for diagnosis.

The patient had no family history of cardiac arrhythmias or sudden death. Physical examination was normal. The initial ECG showed no abnormalities. The exercise stress test was negative for ischemia and di not trigger arrhythmias. The echocardiogram showed a structurally normal heart (LV = 52/35 mm, LVEF = 60%; Aorta = 33 mm; LA = 35 mm; septum and posterior wall = 9 mm; preserved biventricular function, no segmental alterations in contractility and mitral valve prolapse with discrete meso-systolic leak). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging also ruled out structural heart disease showing preserved cardiac chamber dimensions with normal biventricular function (LVEF = 70% and RVEF = 69%), without the presence of myocardial fibrosis.

The Holter monitoring showed several polymorphic VE with short-coupling interval, some of them inducing nonsustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia initiated by extrasystoles with R-on-T phenomenon, with coupling between 350 and 370 ms, and QT intervals within normal limits.

The coronary angiography ruled out the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease. She was prescribed diltiazem 180 mg/day and a defibrillator implant was indicated, performed in August 2011. As the VE persisted (density 2%) with episodes of non-sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, diltiazem was substituted by verapamil 240 mg/day in September 2011. New 24-h Holter monitoring showed a significant reduction in the density of arrhythmias (<1%), increase in minimum coupling interval of extrasystoles to 370 ms and absence of episodes of non-sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, always with a normal QT interval. The patient became asymptomatic, with no further episodes of syncope or ICD therapies, during a nine-month follow up.

Discussion

Described by Dessertenne2 in 1966, TdP ventricular has a typical ECG pattern, with progressive changes in morphology, amplitude and polarity of the QRS complex of which peaks cross the baseline before spontaneously terminating. This phenomenon is preceded by a long-short cycle that triggers the tachycardia, usually after a long coupling interval (600 to 800 ms). The scenario of this arrhythmia includes long QT syndrome in its congenital and acquired forms, as well as the precipitating factors, such as electrolyte disturbances.

Three decades later, in 1994, Leenhardt et al1 published a series of 14 patients without structural heart disease and a history of syncope, whose electrocardiographic monitoring showed TdP polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with normal QT intervals, initiated by VE with short coupling interval (200 - 300 ms). One third of these patients had a family history of sudden death, and approximately 70% had TdP degenerating into ventricular fibrillation during a mean follow-up of seven years. The morphology of isolated VE and those that initiated the TdP was similar in nine patients, with most triggering VE showing left bundle branch block morphology and axis deviated to the left.

In general, the EPS did not reproduce the clinical arrhythmia. The only drug that partially suppressed arrhythmia was verapamil, increasing the VE coupling interval and reducing its density. However, it was not able to prevent sudden death, which is why the ICD is indicated for all patients with this disease.

In the following year, a series of 15 patients with the same characteristics (absence of structural heart disease, normal QT interval) that had episodes of TdP polymorphic ventricular tachycardia initiated by VE with short coupling interval was published. It was demonstrated that the smaller the coupling interval of these extrasystoles, the greater the risk of spontaneous polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and, therefore, of sudden death due to ventricular fibrillation. No medication was able to prevent this outcome3.

In the two largest case series published, similar to our three patients, we observed that the initial clinical presentation was syncope preceded or not by palpitations and the occurrence was predominantly in females. The age of symptom onset ranged from the second to the fifth decade of life and two of our patients were going through major psychological problems, which is described as a potential trigger for the clinical manifestation of the disease2. The mean coupling interval measured from the beginning of the QRS preceding the extrasystole, at the beginning of the latter, was + / - 280 ms. Verapamil has been prescribed to all patients, although the literature reports the frequent occurrence of appropriate ICD therapy and sudden death, in which the defibrillator had not been implanted, despite medication use3.

A case of electrical storm and recovered cardiac arrest triggered by VE with ultrashort coupling interval in a 50-year-old patient was recently published. Similar to our patient in case number 2, there were several episodes of spontaneous TdP polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, some of them developing into ventricular fibrillation requiring cardiorespiratory resuscitation and electrical defibrillation.

Several intravenous medications have been tried, including lidocaine, amiodarone and magnesium, without control of arrhythmia. Ventricular pacing with temporary pacemaker electrode resulted in arrhythmia exacerbation. However, unlike our patient, the infusion of isoproterenol until a heart rate of 100 bpm is achieved showed to be capable of suppressing ventricular arrhythmias. Electrode implantation in the right atrium and its stimulation at a frequency of 85 bpm was effective in arrhythmia remission. After ICD implantation with atrial pacing of 85 bpm, the patient had no symptoms and no evidence of arrhythmias during a three-month follow-up4.

There is no consensus in the literature regarding what the normal value of the VE coupling interval is. In the patient from case number 4, the shortest coupling interval recorded was 360 ms, with several episodes of NSVT occurring with VE of up to 370 ms, with morphological characteristics similar to those from the other three cases. A clinical hypothesis is that it is the same genetic mutation with varying degrees of gene penetration and consequently, different clinical expressions. Therefore, individuals with the more severe form of disease could potentially trigger malignant arrhythmias without necessarily having a coupling interval < 300 ms.

In 2002, Haissaguerre et al5 described the VE with short coupling interval originating from the distal Purkinje fibers as the main triggering factors of idiopathic VF. These extrasystoles had different morphologies and were mapped in several locations of the Purkinje system, including the anterior right ventricular region and large areas of the lower half of the left ventricular septum. The authors ruled out these triggers by focal catheter ablation in 27 patients.

Throughout a mean follow up of 24 months, 89% of patients had no recurrence of ventricular fibrillation5. These findings demonstrate that a therapeutic possibility in this patient population would be treatment by catheter ablation; however, it should be noted that all patients were under the protection of an ICD. In our series, two patients underwent attempted ablation of VE, but the non-occurrence of VE during the procedure prevented their accurate mapping, which would justify the moment of the electrical storm as the ideal setting for the attempted ablation. Another indication for ablative therapy would be cases of appropriate therapies for the ICD, refractory to use of calcium channel blockers.

Regarding family screening, there is no specific reference in the literature about the best management and medical decision in asymptomatic individuals remains controversial. All four patients in our series underwent family screening and extrasystoles with short coupling interval were found in the daughter of Patient 2. Due to the limited data in the literature in asymptomatic individuals, together with the family, we chose to institute a clinical follow-up and prophylactic and empiric prescription of verapamil.

Conclusions

VE patients with short coupling may carry a rare syndrome, probably of genetic etiology, which can result in TdP. Verapamil is apparently the most effective drug for alleviating the occurrence of these arrhythmias; however, it is not effective enough to eliminate the need for an ICD. Ablation of VE could reduce the incidence of TdP; however, there are still technical limitations to its effective implementation. A new look at the disease and the knowledge of this rare heart rhythm disorder is needed so that cardiologists can be able to recognize this electrocardiographic detail and thus identify apparently healthy individuals at risk of genetically determined sudden death.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Chokr MO, Britto AVO, Scanavacca MI; Acquisition of data: Chokr MO, Darrieux FCC, Hardy CA, Hachul DT, Britto AVO, Melo SL, Pisani C, Sosa EA, Martinelli Filho M, Scanavacca MI; Statistical analysis: Chokr MO, Scanavacca MI; Analysis and interpretation of the data: Chokr MO, Sosa EA, Scanavacca MI; Writing of the manuscript: Chokr MO, Britto AVO, Scanavacca MI; Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Chokr MO, Darrieux FCC, Scanavacca MI.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Study Association

This study is not associated with any thesis or dissertation work.

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

References

- 1.Leenhardt A, Glaser E, Burguera M, Nürnberg M, Maison-Blanche P, Coumel P. Short-coupled variant of torsade de pointes: a new electrocardiographic entity in the spectrum of idiopathic ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation. 1994;89(1):206–215. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dessertenne F. La tachycardie ventriculaire á deux foyers opposes variables. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1966;59(2):263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg SJ, Scheinman MM, Dullet NK, Finkbeiner WE, Griffin JC, Eldar M, et al. Sudden cardiac death and polymorphous ventricular tachycardia in patients with normal QT intervals and normal systolic cardiac function. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(10):687–692. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80654-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiladakis JA, Spiroulias G, Koutsogiannis N, Zagli F, Alexopoulos D. Short-coupled variant of Torsade de Pointes as a cause of electrical storm and aborted sudden cardiac death: insights into mechanism and treatment. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2008;49(5):360–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haïssaguerre M, Shoda M, Jais P, Nogami A, Shah DC, Kautzner J, et al. Mapping and ablation of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;106(8):962–967. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027564.55739.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]