Abstract

Background

Shebeens in South Africa are settings in which alcohol use and sexual behavior often co-occur. The prevalence of alcohol use disorder (AUD), and the association between AUD, situations and settings, and sexual risk behavior, in shebeens remains unknown.

Methods

Men (n = 763; mean age = 30; 98% Black African) were recruited from townships in Cape Town, South Africa and completed a self-administered survey that assessed alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and situations and settings of alcohol use. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule DSV-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) was used to identify the likelihood of AUD. Bivariate regression analyses assessed whether screening for AUD predicted sexual risk behaviors. Multivariate regression analyses examined whether AUD and/or situations/settings predicted risk behaviors.

Results

Nearly two-thirds of men (62%) endorsed sufficient criteria for AUD; 25%, 17%, and 20% were classified as having a mild, moderate, or severe AUD, respectively. AUD was associated with HIV risk such that men with AUD reported more unprotected sex than men without AUD. Analyses indicated that (a) individual (i.e., AUD) and (b) settings (i.e., frequency of having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store) interacted to predict unprotected sex.

Conclusions

The prevalence of AUD among shebeen patrons was high and was associated with unprotected sex. Findings suggest the need to integrate both individual and situational/setting factors to prevent HIV among patrons of shebeens.

Keywords: alcohol use disorder, unprotected sex, HIV, South Africa, shebeens, risky sex

1. INTRODUCTION

The HIV/AIDS epidemic remains a major public health concern in South Africa. This country is home to the largest number of people living with HIV in the world with an estimated 6.1 million South Africans infected (UNAIDS, 2013). Not only do South Africans bear the heaviest HIV burden, they also have the highest levels of alcohol consumption per adult drinker worldwide (Rehm et al., 2003). Rates of hazardous or harmful drinking (defined as a pattern of drinking that increases the risk of adverse health events or consequences) are also high with one-third of South African adult drinkers reporting hazardous or harmful alcohol use (Peltzer et al., 2011). Prior research in sub-Saharan Africa shows that alcohol use is associated with increased sexual risk behaviors that put people at risk for HIV (Kalichman et al., 2007; Woolf-King and Maisto, 2011). Thus, alcohol consumption, as a contributing factor of HIV infection as well as other health consequences, is a major public health concern in South Africa (Hahn et al., 2011).

The association between alcohol, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV is complex. Research addressing the alcohol and HIV association varies considerably in methodological approach and includes (a) global (correlating overall alcohol use and sexual behavior), (b) situational (correlating the frequency of alcohol and sexual behavior during a specific time interval), and (c) event-level (alcohol consumption during specific sexual events) approaches. An association between alcohol and risky sexual behavior is typically found in global and situational studies; however, results from event-level studies have varied depending on whether the study assessed a single or multiple-sexual events (Cook and Clark, 2005; Cooper, 2006; Leigh and Stall, 1993; Weinhardt and Carey, 2000). Researchers have also suggested that alcohol and sexual behavior (regardless of the measurement approach) may not be directly related; instead, any number of factors (e.g., gender, environment) may explain this association (Cooper, 2006; Woolf-King and Maisto, 2011). For example, alcohol-serving venues provide individuals not only with the opportunity to consume alcohol but also a location to meet sexual partners. These settings may help explain why alcohol use is associated with sexual risk-taking. In South Africa, the settings in which people drink play an important role in HIV transmission (Hahn et al., 2011; Kalichman et al., 2007; Scribner et al., 2010; Woolf-King and Maisto, 2011).

Shebeens are important community-based social gathering places in South Africa (Watt et al., 2012). Informal public drinking venues, such as shebeens, are settings where alcohol and sexual risk behaviors converge (Kalichman et al., 2007). Weir et al. (2003) found that shebeens are often the places in which people meet new sexual partners. For example, 93% of adults living in Cape Town townships report meeting new sex partners in shebeens and other drinking venues (e.g., bars, taverns). Sex between new or casual partners often occurs at or around drinking venues (Kalichman et al., 2008; Morojele et al., 2006; Myer et al., 2002) but less than 30% of shebeen patrons reported using a condom at last sexual occasion (Weir et al., 2003). Shebeens may facilitate the sexual transmission of HIV, in part, through sexual networks (Kalichman, 2010). In this regard, the prevalence of HIV is higher among patrons of public drinking venues (e.g., shebeens or beer halls) than the general population (Bassett et al., 1996; Kalichman et al., 2008). Thus, sexual behaviors in the context of shebeens are likely to confer higher levels of risk.

South African men are twice more likely to drink in a public drinking venue than women (Weir et al., 2003). Compared to women, men report significantly higher rates of overall alcohol consumption (40 vs. 24 liters) and hazardous or harmful alcohol use (39% vs. 17%; Peltzer et al., 2011; World Health Organization, 2011). Men who drink in shebeens report greater quantity and frequency of alcohol use than those do not patronize shebeens (Cain et al., 2012). Alcohol abuse is a considerable health burden, especially among South African men, in which alcohol abuse accounts for more than 10% of all disability-adjusted life years (DALYs; Schneider et al., 2007). Furthermore, alcohol use disorders account for four times the number of deaths among South African men vs. women (Schneider et al., 2007). Reducing the harm caused by alcohol abuse will require prevention efforts targeted toward men most at risk and in the places where men drink.

From an ecological perspective, the individual, interpersonal, neighborhood, and societal contexts in which alcohol use affects sexual behavior are important. Scribner et al.’s (2010) ecological framework provides a useful conceptual model to help identify HIV-related risk factors (i.e., alcohol and high risk sexual behavior) and their interactions within an alcohol environment. According to this model, individual-level factors such as alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors are important predictors of HIV in an alcohol environment. This model further proposes that the association between alcohol and sexual behavior is moderated by interpersonal factors such as the situation and setting (see Figure 2, page 181). Research has shown that situational factors (e.g., drinking before sex, partner drinking before sex, partner type; Barta et al., 2008; Brown and Vanable, 2007; Kiene et al., 2009, 2008; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010, 2012) impact the alcohol-sexual risk association in sub-Saharan Africa and other locations; however, little research has explored how the setting (i.e., alcohol venues) affects the degree to which alcohol use or misuse is related to risky sex (cf. Kalichman, 2010).

Figure 2.

Proportion of Unprotected Sex by AUD and Setting

Prior research has examined alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among male patrons of shebeens but, to our knowledge, no prior study has screened for alcohol use disorder (AUD) and tested whether AUD is associated with sexual risk behaviors among venue patrons. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was (a) to assess AUD as a risk factor for HIV transmission among male patrons of shebeens in Cape Town. Specifically, we expected that men who met criteria for AUD would be more likely to report sexual risk behavior but the association would differ by AUD severity. Furthermore, it is likely that the situation (e.g., drinking before sex) and setting (e.g., having sex with partners in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store) in which alcohol is consumed may be a contributing factor in the alcohol-sexual risk association (Kalichman et al., 2007; Morojele et al., 2006; Scribner et al., 2010). Therefore, secondary purpose of this study was (b) to examine whether the situation (i.e., drinking before sex) and/or the setting (i.e., having sex with a partner in the drinking environment) moderated the alcohol-risky sex relation. We hypothesized that the situation and setting would be significant independent predictors of sexual risk behavior (main effects). Consistent with the conceptual model guiding the current analyses (i.e., Scribner et al.’s (2010), we expected that the situation and/or setting to moderate the association between AUD and sexual risk behavior (interaction). That is, we expect that the association between AUD and sexual risk behavior will be enhanced for men who report (a) drinking before sex (situation) or (b) having sex with a partner in a drinking venue (setting). Examining the patterns of alcohol use, the situation and/or setting in which sex occurs, and sexual risk behaviors, among patrons of shebeens can guide intervention development specific to the places in which sexual risk occurs.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants and Procedures

Baseline data from a randomized community-level trial evaluating a multilevel HIV/AIDS risk reduction intervention for men who drink alcohol in informal drinking establishments in Cape Town, South Africa, were used to test our hypotheses (Kalichman et al., 2013). We restricted our analyses to the 763 (out of 975) participants who reported drinking in alcohol serving venues (e.g., bars, taverns, or shebeens) in the past 30 days. Participants were men (mean age = 30, 98% Black African, 6% married, 35% had at least a high school education, and 4% employed) from four primarily Xhosa-speaking African townships just outside Cape Town, South Africa. Men were recruited using the chain referral method in which 8 to 10 “seeds” who drank at informal drinking establishments (known as shebeens) in each of the 12 distinct sections of the four townships were invited to participate in a multilevel alcohol and HIV risk reduction intervention at a local community center in one of the townships. These “seeds” recruited other men to participate in the study. Men who reported being 18 years or older and residing within the township section were eligible to participate in the intervention. Eligible participants (79% of the men approached) were given details about the study and, if interested in participating, they provided written informed consent. Participants completed paper-and-pencil surveys and were reimbursed R100 (13 US dollars) for their time. Baseline surveys were conducted between September 1, 2008 and November 30, 2010. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of participating institutions.

2.2 Measures

Surveys assessed (a) demographic information (e.g., age, ethnicity), (b) the likelihood of an alcohol use disorder, (c) situation (alcohol use before sex) and setting (having sex with partners in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store), (d) sexual behaviors (number of sexual partners, unprotected vaginal and anal sex), and (e) additional measures (e.g., attitudes, social norms) as part of the larger study.

2.2.1 Alcohol Use Disorder

Identification of AUD was assessed using items from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule DSV-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV), adapted as a self-administered survey format (Grant et al., 2001). The AUDADIS-IV is based on criteria for alcohol use disorders as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Items represent four abuse criteria (failing to fulfill obligations, continuing to drink despite problems, recurrent drinking in hazardous situations, or alcohol-related legal problems) and seven dependence criteria (tolerance, withdrawal, drinking larger amounts over longer time intervals, persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to control drinking, reducing important activities in favor of drinking, time spent to obtain alcohol or drink, or continued drinking despite physical or psychological problems). The recently released fifth edition of the DSM employs a unitary construct of AUD that varies in terms of severity: mild (2 to 3 criteria), moderate (4 to 5 criteria), and severe (≥6 criteria; American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Hasin et al., 2013). Individuals who endorse at least two criteria are considered to have AUD. Therefore, we used participants endorsement of the abuse and dependence criteria on the AUDADIS-IV to classifying participants as having AUD (yes, no) as well as to rate the severity of AUD (none [0], mild [1], moderate [2] or severe [3]). (Because the DSM-V criteria dropped alcohol-related legal problems and added a new criterion of craving, we recognize that the AUDADIS item set does not completely represent current AUD criteria. However, only a subset of men endorsed the item representing legal problems [10%] and most of those men [90%] endorsed other criteria so that is not inflating our AUD estimate. The lack of an item representing craving could result in our underestimating the prevalence of AUD in this sample.)

2.2.2 Situations and Settings

Two questions addressed the situation and setting in which alcohol and sex occurred. Participants were asked about the frequency with which they (a) consumed alcohol before sex by asking the number of times they had “drank alcohol (beer, wine) before sex” during the past 30 days and (b) had sex with someone at a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store in the past 30 days (zero to five or more times).

2.2.3 Sexual Risk Behaviors

Participants were asked questions regarding their sexual risk behavior during the past 30 days. Number of sexual partners was assessed by asking participants the number of women or men they had sex with in the past 30 days. Number of vaginal or anal sex events (in past 30 days) was assessed by asking participants how often they had (a) vaginal sex with or without a condom (protected and unprotected vaginal sex) and (b) anal sex with or without a condom (protected and unprotected anal sex). Responses were used to determine the (a) number of unprotected sexual events in the past 30 days (number of times vaginal or anal sex occurred without a condom) and (b) proportion of unprotected sexual events in past 30 days (number of times vaginal and anal sex occurred without a condom divided by the total number of vaginal and anal sexual events).

2.3 Data Management and Analysis

All continuous variables were examined for outliers. For all count variables (number of sexual partners, unprotected sex events, drinking before sex), responses more than 3 standard deviations above the mean were recoded to be equivalent to the value 3 standard deviations from the mean plus 1 (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Summary statistics (means and standard deviations, frequencies) were used to describe demographic and risk characteristics for the overall sample and by AUD. Differences in sample characteristics by AUD category were tested using a series of bivariate analyses (chi-square and one-way analysis of variance). Demographic variables that differed by AUD were included in the hierarchical regression analyses.

Bivariate regression analyses were used to test our hypothesis that AUD is associated with sexual risk behaviors and whether this association differs by AUD severity. Specifically, we conducted separate analyses predicting sexual risk behaviors (number of sexual partners, unprotected sex events, proportion of unprotected sex events) from AUD (yes, no) and AUD severity (none, mild, moderate, severe). We also conducted bivariate regression analyses to examine whether the situation (drinking before sex) and setting (having sex in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store) predicted sexual risk behaviors.

Bivariate analyses were followed by hierarchical regression analyses to assess whether AUD independently, or in combination with the situation or setting of sexual risk behavior, predicted sexual risk behavior. Three separate models were used to examine whether AUD and situation (drinking before sex) and setting (having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store) predicted sexual risk behaviors (number of sexual partners, unprotected sex, and proportion of unprotected sex events). Demographic variables that were significantly different between men who did and did not meet screening criteria for an AUD were entered in Step 1. In Step 2, AUD (1 = yes, 0 = no) was entered. Both situational (drinking before sex; continuous variable) and setting (having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store; continuous variable) variables were entered in Step 3. Poisson regression was used to model total number of sexual partners (count) and negative binomial regression analysis was used to model unprotected sex events (skewed, clustered at zero, and overdispersed). Linear regression was used to assess the proportion of unprotected sex. Robust variance estimation was used in all hierarchical regression analyses (Cameron and Trivedi, 2013). All data analyses were conducted using Stata 12 (StataCorp, 2011).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of the Sample

Analyses were restricted to the 763 men (78% of the original sample) who reported drinking in alcohol serving venues (e.g., bars, taverns, or shebeens) in the past 30 days (Table 1). Of these men, most identified as Black African (98%) with a mean age of 30 years (SD = 9, range = 19 to 57 years). Few men reported being married (6%); over half of the men (61%) reported having at least one child. Most of the sample (96%) was unemployed; 35% reporting having at least a high school education. Men reported an average of 3 sexual partners (M = 2.74, SD= 3.34) and 3 unprotected sex events (M = 3.25, SD = 8.10) in the past 30 days. One-third of men’s vaginal or anal sex events were unprotected (M% = 0.29, SD = 0.35).

Table 1.

Characteristics of South African Men who Patronize Alcohol-Serving Venues (N = 763)

| Alcohol Use Disorder | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Overall | None n = 291 |

Any n = 472 |

Mild n = 194 |

Moderate n = 129 |

Severe n = 149 |

|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, M(SD) | 30 (9) | 30 (9) | 30 (9) | 30 (9) | 29 (8) | 31 (9) |

| Ethnicity, % Black | 98 | 99 | 98 | 100 | 98 | 96 |

| Marital status, % married | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| Children, % | 61 | 58 | 62 | 63 | 62 | 61 |

| Education, % high school | 35 | 40 | 32 | 32 | 39 | 25 |

| Unemployed, % | 96 | 97 | 96 | 95 | 98 | 97 |

| Sexual Behaviors | ||||||

| Sexual partners, no. | 2.74 (3.34) | 2.52 (3.33) | 2.89 (3.34) | 2.76 (3.01) | 3.20 (4.21) | 2.77 (2.88) |

| Unprotected sex, no. of events | 3.25 (8.10) | 2.87 (9.45) | 3.49 (7.15) | 2.37 (4.50) | 4.74 (8.83) | 3.87 (8.12) |

| Unprotected sex, % of events | 29 (35) | 25 (34) | 32 (36) | 27 (34) | 37 (37) | 33 (36) |

| Situational/Setting Factors | ||||||

| Participant drank before sex, no. | 3.91 (5.45) | 4.15 (5.62) | 3.52 (5.15) | 3.53 (5.13) | 3.94 (5.11) | 5.15 (6.49) |

| Sex with partner in PDV, frequency | 0.61 (1.27) | 0.41 (1.04) | 0.73 (1.38) | 0.64 (1.36) | 0.80 (1.46) | 0.80 (1.33) |

PDV, public drinking venue such as a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store.

3.2 Alcohol Use Disorder

A large proportion of men (62%; n = 472) met criteria for having AUD according to self-report. Men were classified as having none (38%), mild (25%), moderate (17%), or severe (20%) AUD based on DSM-V guidelines. Demographic characteristics of the men did not differ by AUD status except for education: men with AUD were less likely to have completed high school or beyond, Χ2 = 5.59, p = .018. Therefore, we controlled for education in the following analyses.

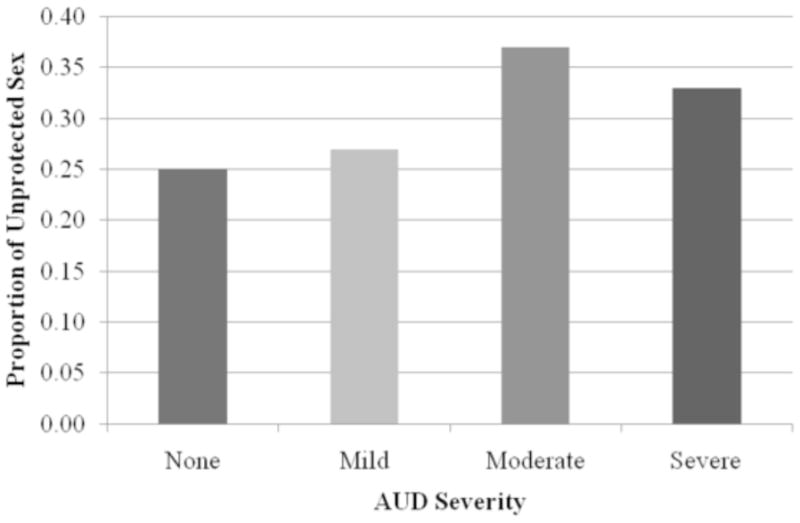

Results from the bivariate regression analyses predicting sexual risk behaviors from AUD status and AUD severity are shown in Table 2. Meeting criteria for AUD was not associated with sexual risk behaviors with one exception: men with AUD reported a greater proportion of unprotected sex events (32%) than men without an AUD (25%), p = .015. As displayed in Figure 1, men classified as having a moderate AUD were more likely to engage in unprotected sex (count or proportion) compared with men without AUD, ps ≤.047. Compared to men without AUD, men with a severe AUD reported a greater proportion of unprotected sex events (25% vs. 33%), p = .037. AUD severity was not associated with the total number of sexual partners (ps >.083).

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations between Individual and Situational/Setting Factors and Sexual Risk Behaviors

| Sexual Risk Behaviors

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Partners (count) | Unprotected Sex (count) | Unprotected Sex (proportion) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| IRR (RSE) | p | IRR (RSE) | p | β (SE) | p | |

| Individual | ||||||

| Any AUD* | 1.15 (.11) | .145 | 1.22 (.26) | .360 | .09 (.03) | .015 |

| AUD Severity* | ||||||

| Mild | 1.10 (.12) | .394 | 0.83 (0.20) | .417 | .02 (.03) | .523 |

| Moderate | 1.27 (.18) | .083 | 1.65 (0.42) | .047 | .12 (.04) | .003 |

| Severe | 1.10 (.13) | .399 | 1.35 (0.35) | .243 | .08 (.04) | .037 |

| Situational/Setting Factors | ||||||

| Situational: Drinking before sex | 1.03 (.01) | .000 | 1.07 (.02) | .000 | .04 (.00) | .337 |

| Setting: Sex with partner in PDV | 1.17 (.04) | .000 | 1.21 (.08) | .003 | .09 (.01) | .014 |

No AUD is the reference category in these analyses.

AUD, alcohol use disorder; IRR, incidence rate ratio; RSE, robust standard error.

Figure 1.

Proportion of Unprotected Sex by AUD Severity

3.3 Situations and Settings

Men reported consuming alcohol before sex on an average of 4 occasions (M = 3.91, SD = 5.45) and having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store less than 1 time (M= 0.61, SD = 1.27) in the past 30 days. Bivariate regression analyses were used to predict sexual risk behaviors from the situation and setting in which sexual risk behavior occur (see Table 2). Both the situation and setting of sexual risk behavior predicted the number of sexual partners and the number of unprotected sex events, ps <.01. Only the setting (i.e., having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store) predicted the proportion of unprotected sex events, p = .014. For all analyses, drinking before sex and having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store was associated with increased risk (i.e., more sexual partners or unprotected sex events and a greater proportion of unprotected sex events).

3.4 Predictors of Sexual Risk Behaviors

Hierarchical regression analyses (poisson, negative binomial, and linear) were used to examine whether AUD, or the situation and/or setting in which sex occurs, predicted sexual risk behavior. Three separate models were tested, controlling for education (Step 1). In these analyses, we include AUD (1 = yes, 0 = no; Step 2) and situational/setting factors (number of times men drank before sex and had sex in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store; Step 3). The results from the hierarchical regression analyses are presented in Table 3. AUD was associated with unprotected sex (proportion), but not the number of sexual partners: men with AUD reported a greater proportion of unprotected sex events compared to men without AUD (β = .10, p = .010). The situations and settings in which sexual behavior occurred also predicted sexual risk behaviors: drinking before sex and having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store predicted the number of sexual partners and number of unprotected sex events (ps ≤.031). The regression models predicting the number of (a) sexual partners (final model: Wald’s Χ2 = 48.31, p <.001) and (b) unprotected sex events (final model: Wald’s Χ2 = 20.33, p <.001) from the individual and situational/setting factors was statistically significant. The linear regression model predicting the proportion of unprotected sex from individual and situational/setting factors did not reach statistical significance: overall Wald’s Χ2 = 2.62, p <.063, for the final model. (The Wald’s chi-square statistics for the final models are not presented in Table 3.)

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Sexual Risk Behaviors from Individual and Situational/Setting Factors

| Sexual Risk Behaviors

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Partners (count) | Unprotected Sex (count) | Unprotected Sex (proportion) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| IRR (RSE) | p | IRR (RSE) | p | β (RSE) | p | |

| Step 1: Covariates | ||||||

| Education, % high school | 0.92 (.08) | .370 | 1.11 (.20) | .552 | .02 (.03) | .663 |

| Wald Χ2 = 0.81 | Wald Χ2 = 0.35 | F (1, 665) = 0.19 | ||||

| Step 2: Individual | ||||||

| AUD | 1.14(.11) | .187 | 1.23 (.27) | .347 | .10 (.03) | .010 |

| Wald Χ2 = 3.77 | Wald Χ2 = 0.95 | F (1, 664) = 3.56* | ||||

| Step 3: Situational/Setting Factors | ||||||

| Situational: Drinking before sex | 1.03 (.01) | .000 | 1.06 (.02) | .000 | .02 (.00) | .503 |

| Setting: Sex with partner in PDV | 1.14 (.03) | .000 | 1.12 (.06) | .031 | .08 (.01) | .039 |

| Wald Χ2 = 53.07*** | Wald Χ2 = 21.49*** | F (1, 662) = 3.30* | ||||

RSE, robust standard errors. AUD, alcohol use disorder. PDV, public drinking venue such as a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store.

p <.05;

p <.01;

p <.001

Moderator Analyses

AUD and having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store were significant predictors of the proportion of unprotected sex. Scribner et al.’s conceptual model of HIV risk indicates that the association between alcohol and sexual behavior is moderated by the setting (see Scribner et al., 2010, Figure 2, page 181). Therefore, we examined whether individual (AUD) and setting (sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store) interacted. Specifically, linear regression analyses were used to predict the proportion of unprotected sex from AUD (yes, no), having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store (continuous), and the interaction between AUD and setting (AUD × sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store). In this model we controlled for education and participants’ drinking before sex. Main effects for both the individual and setting variables were found such that men with AUD (vs. none; β = .14, p =.001) or the frequency of having sex in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store (β = .25, p <.001) predicted unprotected sex. These main effects were qualified by a significant interaction (β = −.21, p =.002). As shown in Figure 2, the proportion of unprotected sex among men without AUD increased as the frequency of sex in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store increased whereas unprotected sex among men with AUD remained relatively stable as their frequency of sex in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store increased. The overall model was significant: F (5, 661) = 4.30, p = .001.

4. DISCUSSION

Hazardous and harmful drinking may increase an individual’s risk for HIV. In South Africa, informal public drinking venues, such as shebeens, are important community social gathering places (Watt et al., 2012) in which alcohol use and sexual behaviors converge (Kalichman et al., 2007). The extent to which alcohol consumption among patrons of shebeens meets criteria for AUD, a condition that can be treated and managed, has not previously been estimated. The prevalence of AUD observed in this study may, in part, explain the high rates of HIV transmission among patrons of shebeens. To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess a likely AUD, the severity, the situation and setting in which risky sex occurs, and the relation to sexual risk behaviors among men who patronize shebeens in South Africa.

Although our assessments were based on survey data, it appears that AUD among men who patronize shebeens is highly prevalent. Most men (62%) met self-reported criteria for an AUD, with 25% classified as having a mild, 17% classified as having a moderate, and 36% classified as having a severe AUD. The prevalence of AUD in this sample was much higher than a national probability sample of South African adults in which 11% and 3% met screening criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, respectively (Suliman et al., 2010). The discrepancy in prevalence rates is not surprising given that all men in the current sample consumed alcohol in the past month whereas only 34% of the national probability sample reported using alcohol regularly during their lifetime. Suliman et al. (2010) also showed that men (vs. women) were more likely to transition from regular alcohol use to alcohol abuse. Gender-specific findings from the national probability sample and the prevalence of AUD in our sample suggest that interventions targeting alcohol use, including the presence of AUD, are needed among South African men who frequent shebeens.

Prior research shows that alcohol use and misuse is associated with increased sexual risk behaviors that put people at risk for HIV (Kalichman et al., 2007; Woolf-King and Maisto, 2011). Consistent with prior research, we found that the likelihood of AUD was associated with unprotected sexual intercourse (bivariate analyses). That is, moderate to severe AUDs were associated with unprotected sex such that men with a moderate AUD reported more unprotected sex (count or proportion) and men with a severe AUD had a greater proportion of unprotected sex in the past month compared to men without an AUD. In contrast, AUD was not a significant predictor of the number of sexual partners. Subsequent hierarchical regression analyses showed that situations and settings were the strongest predictors of sexual partners and unprotected sex (count) such that alcohol use before sex (situational) and the frequency of having sex with partners in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store (setting) predicted the number of sexual partners and unprotected sex events. Alcohol use disorder, the setting, and their interaction predicted the proportion of unprotected sex; that is, as the frequency of having sex with a partner in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store increased, men without AUD (vs. with AUD) reported a greater proportion of unprotected sex events in the past 30 days. Interestingly, men with AUD consistently reported having unprotected sex approximately one-third of the time regardless of their frequency of having sex in a shebeen, tavern, or bottle store suggesting that their sexual risk taking was less influenced by the setting (Edwards, 1986). The alcohol-sexual risk behavior literature is complex; alcohol use may “promote, inhibit, or have no effect on behavior” depending on “third variable” explanations such as the situation or setting (Cooper, 2006). Taken together, these findings suggest that both individual- and situational/setting factors and their interaction influence HIV transmission (Scribner et al., 2010). Interventions that address both the individual and situation/setting may be required to reduce the transmission of HIV among men who frequent shebeens (Kalichman, 2010; Scribner et al., 2010).

This study has several limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings. First, men were recruited using chain referral methods and may not be representative of the larger community. Second, data were gathered from self-reports, which can be vulnerable to reporting bias. To minimize socially desirable responding (Weinhardt et al., 1998), field staff emphasized that all data were confidential, and encouraged participants to respond honestly. Furthermore, recall of alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors may differ by AUD and non-AUD participants. Third, our assessment of the rates and severity of AUD was based on self-administered diagnostic questions, not structured interviews. Future research should use formal diagnostic interviews to confirm the rates and severity of AUD among men who frequent shebeens. Fourth, because the study was designed prior to the publication of the DSM-V, our assessment lacked the item assessing craving that was added to the DSM-V criteria. Thus it is likely that our data represents an underestimate of AUD prevalence. Fifth, we used a situational measure of drinking before sex; situational measures (and study designs) are stronger methods than global measures (and designs) of the alcohol—sexual risk behavior association but they are weaker than event-level methods (Leigh and Stall, 1993). Nonetheless, our situational measure of drinking before sex in the past 30 days (yes/no) limits our interpretation of our findings and may have overestimated the extent to which men drink alcohol before sex. That is, men who responded “yes” to this question could have consumed alcohol on a single, isolated occasion vs. multiple occasions in the past month. Sixth, alcohol abuse and misuse is often associated with economic status (Peltzer et al., 2011). Most men (96%) reported that they were unemployed; high rates of AUD observed in our sample of predominately unemployed men may not be representative of all South African men. Finally, data used for this study are cross-sectional and cannot support causal inferences. Longitudinal data can provide stronger evidence regarding the impact of alcohol use disorders on sexual risk behaviors.

Our data suggest that meeting criteria for AUD may be common among South African men who patronize shebeens and that having AUD is associated with risky sexual behaviors. Both AUD and situational/setting factors are related to HIV transmission risk. Findings from this study support the need for interventions targeting AUDs and sexual risk transmission in the broader context in which sexual risk occurs. Multilevel alcohol venue-based HIV interventions, that is interventions targeted to the individual and the settings, may be required to prevent HIV transmission among South African men who patronize shebeens (Kalichman, 2010).

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AA017399 (Seth C. Kalichman, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We thank the participants, staff, and our research team.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

Lori Scott-Sheldon, Kate Carey, and Michael Carey were responsible for the study concept and design. Demetria Cain was responsible for the acquisition of the data and Lori Scott-Sheldon performed the statistical analyses. All authors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. Lori Scott-Sheldon, Kate Carey, and Michael Carey were responsible for the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. Seth Kalichman was responsible for obtaining funding and supervising the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. APA; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. APA; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barta WD, Portnoy DB, Kiene SM, Tennen H, Abu-Hasaballah KS, Ferrer R. A daily process investigation of alcohol-involved sexual risk behavior among economically disadvantaged problem drinkers living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:729–740. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MT, McFarland WC, Ray S, Mbizvo MT, Machekano R, van de Wijgert JH, Katzenstein DA. Risk factors for HIV infection at enrollment in an urban male factory cohort in Harare, Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1996;13:287–293. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199611010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: findings from an event-level study. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain D, Pare V, Kalichman SC, Harel O, Mthembu J, Carey MP, Carey KB, Mehlomakulu V, Simbayi LC, Mwaba K. HIV risks associated with patronizing alcohol serving establishments in South African Townships, Cape Town. Prev Sci. 2012;13:627–634. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression Analysis of Count Data. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Does Drinking Promote Risky Sexual Behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G. The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome: a concept as stimulus to enquiry. Br J Addict. 1986;81:171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Schedule--DSM-IV Version. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Woolf-King SE, Muyindike W. Adding fuel to the fire: alcohol’s effect on the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:172–180. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, Compton WM, Crowley T, Ling W, Petry NM, Schuckit M, Grant BF. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:834–851. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC. Social and structural HIV prevention in alcohol-serving establishments. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33:184–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cain D, Carey KB, Carey MP, Eaton L, Harel O, Mehlomakulu V, Mwaba K. Randomized community-level HIV prevention intervention trial for men who drink in South African alcohol-serving venues. Eur J Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt172. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8:141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Jooste S, Cain D. HIV/AIDS risks among men and women who drink at informal alcohol serving establishments (Shebeens) in Cape Town, South Africa. Prev Sci. 2008;9:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Barta WD, Tennen H, Armeli S. Alcohol, helping young adults to have unprotected sex with casual partners: findings from a daily diary study of alcohol use and sexual behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Simbayi LC, Abrams A, Cloete A, Tennen H, Fisher JD. High rates of unprotected sex occurring among HIV-positive individuals in a daily diary study in South Africa: the role of alcohol use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:219–226. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318184559f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Kachieng’a MA, Mokoko E, Nkoko MA, Parry CD, Nkowane AM, Moshia KM, Saxena S. Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Matthews C, Little F. Condom use and sexual behaviors among individuals procuring free male condoms in South Africa: a prospective study. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:239–241. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Davids A, Njuho P. Alcohol use and problem drinking in South Africa: findings from a national population-based survey. Afr J Psychiatry. 2011;14:30–37. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v14i1.65466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Norman R, Parry C, Bradshaw D, Pluddemann A South African Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Estimating the burden of disease attributable to alcohol use in South Africa in 2000. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:664–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Cain D, Harel O, Mehlomakulu V, Mwaba K, Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC. Patterns of alcohol use and sexual behaviors among current drinkers in Cape Town, South Africa. Addict Behav. 2012;37:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R, Theall KP, Simonsen N, Robinson W. HIV risk and the alcohol environment. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33:179–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Suliman S, Seedat S, Williams DR, Stein DJ. Predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders in South Africa. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:695–703. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Pearson/Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. [accessed on September 30, 2013];Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2013 http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf.

- Watt MH, Aunon FM, Skinner D, Sikkema KJ, Kalichman SC, Pieterse D. “Because he has bought for her, he wants to sleep with her”: alcohol as a currency for sexual exchange in South African drinking venues. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:125–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Forsyth AD, Carey MP, Jaworski BC, Durant LE. Reliability and validity of self-report measures of HIV-related sexual behavior: progress since 1990 and recommendations for research and practice. Arch Sex Behav. 1998;27:155–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1018682530519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Pailman C, Mahlalela X, Coetzee N, Meidany F, Boerma JT. From people to places: focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS. 2003;17:895–903. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000050809.06065.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf-King SE, Maisto SA. Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40:17–42. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. [accessed on November 21, 2011];Global status report on alcohol and health. 2011 http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/msbgsruprofiles.pdf.