Abstract

This longitudinal study was designed to (i) examine changes in children’s deliberate memory across the first grade; (ii) characterize the memory-relevant aspects of their classrooms; and (iii) explore linkages between the children’s performance and the language their teachers use in instruction. In order to explore contextual factors that may facilitate the development of skills for remembering, 107 first graders were assessed three times with a broad set of tasks, while extensive observations were made in the 14 classrooms from which these children were sampled. When the participating teachers were classified as high or low in terms of their “mnemonic orientation,” in part on the basis of their use of metacognitive information and requests for deliberate remembering during instruction in language arts and mathematics, differences were observed in the use of mnemonic techniques by the children in their classes. By the end of the year, the children drawn from these two groups of classrooms differed in their spontaneous use of simple behavioral strategies for remembering and in their response to training in more complex verbally-based mnemonic techniques.

Over the past 30 years, a rich database of information concerning age-related changes in the generation of memory strategies has been amassed (Kail & Hagen, 1977; Schneider & Bjorklund, 1998). This body of work has demonstrated convincingly that with increases in age, children become more proficient in the use of strategies for the encoding, storage, and retrieval of information. This wealth of information notwithstanding, the literature is relatively silent with regard to two key developmental questions (Ornstein, Baker-Ward, & Naus, 1988; Ornstein & Haden, 2001). First, what can be said about the course of memory development within individual children? And second, what are the factors that underlie this development? To explore these critical issues, the research reported here was designed to characterize the first-grade classroom context in which mnemonic skills are thought to develop and to identify preliminary linkages between aspects of the classroom context and children’s memory performance. This exploration was motivated by a commitment to the “blending” of two perspectives: the information processing orientation for assessing the children’s changing memory skills, and the social constructivist viewpoint for describing the socialization of skills in the classroom context (Ornstein & Haden, 2001).

A large literature provides a rich description of age-related changes in children’s use of strategies such as rehearsal (e.g., Ornstein & Naus, 1978), organization (e.g., Lange, 1978), and elaboration (e.g., Rohwer, 1973). Across the elementary school years there is a very systematic transition from relatively passive to more active techniques of remembering in tasks involving deliberate memorization of words or pictures, and these strategies are linked clearly to success in remembering (Schneider & Bjorklund, 1998). Unfortunately, however, insight into the development of these skills is limited greatly by the cross-sectional nature of most research on children’s memory. Longitudinal research designs in which children are tracked over time are important for making statements about developmental (as opposed to age-related) changes within individual children and in permitting inferences about factors that may serve to bring about these changes. Indeed, the few extant longitudinal studies suggest that generalizations from cross-sectional findings about the course of strategy development may not reflect an accurate picture of individual developmental pathways (e.g., Schneider & Sodian, 1997; Schneider, Kron, Hünnerkopf, & Krajewski, 2004). More specifically, strategy development may be best characterized in terms of dramatic leaps in performance, and not gradual increases in sophistication over time. Complementary information about the development of strategic competence has also resulted from microgenetic studies (Siegler, 2006) in which focused, in-depth observations are made at times during which the skills being examined are undergoing change. Importantly, microgenetic studies of children’s acquisition of a categorization strategy (Schagmüller & Schneider, 2002) have indicated that children who came to use the strategy did so at different times, but in an all-or-none fashion.

A second difficulty with the cross-sectional literature is that it provides relatively little insight into the factors that serve to bring about developmental change (Ornstein & Haden, 2001). Of course, children’s increasing sophistication in the deployment of strategies for remembering is widely seen as contributing to age-related improvement in deliberate memory tasks, but relatively little is known about the origins of these mnemonic techniques. However, generalizing on the basis of the few longitudinal studies of autobiographical – as opposed to deliberate – memory (e.g., Reese, Haden, & Fivush, 1993), it seems likely that children acquire these strategies for remembering in the social context of the classroom. These investigations suggest that preschoolers develop skills in talking about the past in the context of social-communicative interactions with their parents, and by extension it seems likely that the repertoire of mnemonic strategies that emerge during the elementary school years is influenced by similar types of interactions with teachers in the school setting. Consistent with this perspective, a number of lines of work point to the potential impact of formal schooling on the development of memory strategies (e.g., Moely et al., 1992; Morrison, Smith, & Dow-Ehrensberger, 1995; Wagner, 1978).

The importance of schooling is demonstrated in a number of cross-cultural explorations of the cognitive skills of children matched in chronological age but who differed in terms of whether they had or had not participated in Western-style schooling. Thus, for example, Scribner and Cole (1978) and Wagner (1978), working in Liberia and Morocco, respectively, observed that children who attended school demonstrated superiority in the mnemonic skills that have typically been studied by Western psychologists (see also Rogoff, 1981). These findings suggest that something in the formal school context most likely is related to the emergence of skills that are important for success on tasks that involve deliberate memorization. Moreover, research by Morrison et al. (1995) complements the cross-cultural work by suggesting more precisely that the first-grade experience is particularly important for the development of memory skills. Morrison and his colleagues studied two groups of children who were close in age, those who “just made” the mandated date for entry into first grade (a “young” first grade group) and those who “just missed” the date (an “old” kindergarten group). Taking performance at the start of the school year as a baseline, the young first graders evidenced substantial improvement in their memory skills. In contrast, the performance of the older kindergartners did not change over the year, although improvement was noted the next year, following their experience in the first grade. These findings imply that there is something in the first-grade context that is supportive of the development of children’s memory skills.

Given that schooling is identified as a potential facilitator of developmental change in mnemonic skill, what is it about the classroom context that is important? In an effort to examine this issue, Mercer (1996) made systematic observations in first-grade classrooms and also questioned teachers about their beliefs and practices concerning memory. Mercer (1996) reported that although teachers considered strategies for remembering to be very important, they nonetheless did not teach these techniques in a direct fashion. Moreover, consistent with the teachers’ verbal reports, Mercer’s observations in six classes revealed that explicit strategy suggestions were very rare, occurring in only 2.4% of the observational intervals that were coded. Indeed, even informing students that remembering was an expressed goal of an ongoing activity was a rare occurrence, taking place in only 1.8% of the observational intervals. Nonetheless, the teachers often made implied memory demands of the children in their classes. Indeed, across the classrooms, 38.8% of the intervals contained instances in which memory was strongly implied, albeit not overtly expressed.

Mercer’s (1996) findings are consistent with Moely et al.’s (1992) report that explicit instruction in mnemonic techniques by teachers throughout the elementary school grades is quite low. Moely and her colleagues also divided teachers in the first, second, and third grades into groups reflecting more versus less strategy suggestion. Importantly, children in the first-grade classes of teachers who provided more suggestions about strategy use in their lessons were more likely to spontaneously generate organizational strategies in recall tasks than were children whose teachers gave fewer strategy suggestions. This differentiation in strategy usage was not found among second- and third-grade children of high versus low strategy teachers. Nonetheless, it must be reiterated that very few strategy suggestions were observed in any of the classrooms that Moely et al. visited. To illustrate, general information about cognitive processes was noted in 9.5% of the intervals in which observations were made; moreover, fewer than 3% of the observational intervals contained strategy suggestions.

These findings lead to a critical question: if school is important in terms of the emergence and refinement of mnemonic techniques, but if explicit instruction is an infrequent occurrence, then what is it about the first-grade classroom that influences the development of these skills? As indicated above, one strong possibility is suggested by an observed linkage between the ways in which mothers of preschoolers structure conversations about past experiences and the memory abilities of their children. Fivush and her colleagues (e.g., Fivush & Fromhoff, 1988; Reese et al., 1993) have shown that remembering is aided greatly by mothers’ provision of detailed information about events and by increased opportunities for children to report their experiences. For example, Reese et al. observed that mothers classified as high-elaborative in their conversational style encouraged talk about past events more than low-elaborative mothers. Importantly, the children of these high-elaborative mothers showed elevated recall of the events under discussion, and they also seemed to acquire some generalized skills for remembering. Indeed, levels of maternal elaboration early in development were associated positively with children’s independent provision of information in later conversations. Moreover, confirming these demonstrations of associations between maternal elaboration and children’s memory performance, training studies in which mothers’ conversational style has been brought under experimental control now reveal clear benefits of an elaborative style of engagement (McGuigan & Salmon, 2004; Peterson, Jesso, & McCabe, 1999; Reese & Newcombe, 2007). Importantly, Reese and Newcombe (2007) have shown that in comparison with a control group, the children of mothers who were trained in an elaborative conversational style when they were 19 months of age demonstrated elevated levels of independent remembering when they were 44 months old.

Extending this finding that conversations about the past may serve to support the development of children’s independent memory skills, Haden, Ornstein, Eckerman, & Didow (2001) have shown that adult-child discussions about novel events while they are being experienced together can also affect children’s recall. In fact, adult-child conversations as events unfold and after they have taken place are likely to have an important impact on preschoolers’ memory (McGuigan & Salmon, 2004; Ornstein, Haden, & Hedrick, 2004). Conversations as an event unfolds can provide children with information to aid their interpretation of the experience and thus facilitate comprehension and encoding, whereas elaborative discussion of an event most likely leads to deep levels of processing that are known to support later (incidental) recall (see Corsale & Ornstein, 1980; Craik & Lockhart, 1972). Moreover, the notion that parent “talk” about an event can influence children’s remembering suggests that teacher “talk” may also be relevant for the development of early memory skills. For example, if teachers are not directly providing instruction in strategy use, there may be something about the nature of teacher-student conversation that facilitates children’s acquisition of techniques that are effective for remembering.

Reflecting this analysis of the potential importance of conversation in the classroom, a dual-level observational system was developed to characterize teachers’ talk while in the course of instruction. With this system, one observer in the classroom uses a new coding system, the Taxonomy of Teacher Behaviors, to classify each teacher’s conversation into the four broad categories of (i) instruction, (ii) cognitive structuring activities (encouraging children to engage the materials in ways that are known to facilitate encoding and retrieval of information), (iii) memory requests (asking students to retrieve information already acquired or to prepare for future activities), and (iv) metacognitive information (providing or soliciting information that might facilitate performance on a range of cognitive tasks in the classroom). Simultaneously, a second observer prepares a contextual narrative of each lesson as it unfolds, so that coders can later make inferences about the nature of the memory demands being communicated by the teacher. Although use of the observational system captures many features of classroom instruction that are important for children’s mnemonic development, extensive pilot work led to the construction of a measure of teachers’ “mnemonic orientation” that was based on a subset of the component codes. More specifically, this composite index was based on a consideration of teachers’ strategy suggestion and metacognitive questioning (even though these are relatively low frequency activities) and the occurrence of deliberate memory demands in the context of (i) instructional activities, (ii) cognitive structuring activities, and (iii) the provision of metacognitive information. The selection of these activities for the index was based primarily on their presumed role in memory and its development. Thus, for example, cognitive structuring activities affect the depth to which information is processed (Craik & Lockhart, 1972), whereas memory requests and the provision of strategy suggestions and metacognitive information impact encoding, retrieval, or both (Schneider & Pressley, 1997).

With a methodology for characterizing teachers’ memory-relevant talk in place, the research described here was launched to examine the development of children’s memory strategies in the context of the first-grade classroom. A longitudinal design was employed to capture changes in mnemonic skill across the first grade, a time during which children’s application of deliberate memory skills comes to be associated with improved memory performance (Baker-Ward, Ornstein, & Holden, 1984). The participating children were assessed three times across the year with a broad battery of memory tasks while, simultaneously, their teachers were observed as they taught lessons in language arts and mathematics. Given the complex nature of the study design – with children nested into different classrooms and multiple memory measures being collected over time – hierarchical linear models were employed to examine within-child, between-child, and between-teacher effects. Making use of these unique methodological and analytic strategies, the overall aims of the project were to (i) describe children’s competence on different memory tasks over the course of the first-grade year, (ii) characterize memory-relevant aspects of the first-grade classrooms in which the participants were embedded, and (iii) link relevant features of the classroom to the children’s recall and strategy performance.

METHOD

Participants

A sample of 107 children (49 boys and 58 girls) was recruited and followed across the first grade, using a large multi-task battery to assess their memory performance three times throughout the year. All first-grade students and teachers at four schools in two school districts in a southeastern state were invited to take part in the study.

In initial discussions with the 15 first-grade teachers at the participating schools, the study was described as one of the classroom context in which children’s memory skills develop, with an emphasis on their naturally-occurring experiences in the classroom. The teachers were told that they would be observed as they taught regularly-scheduled lessons in language arts and mathematics, but no mention was made of the emphasis on teacher language in the course of instruction. With this understanding, all of the teachers agreed to participate in the study. Each of the teachers was female – 12 Caucasian and 3 African American – with an average age of 36 years (range = 23–51 years). They had a mean of 10.6 years of teaching experience (range = 1–30 years) with an average of 7.5 years of teaching in the first grade (range = 1–30).

Letters were sent to the families of all children in the classes of the participating teachers, and any student who returned a consent form was enrolled in the study, with no criteria for exclusion. Approximately 8 children (range = 3–13) from each classroom chose to participate, and because two of the 15 teachers co-taught, these students were nested into 14 different classrooms across the four schools. At the initial time point, children’s mean age was 79 months (range = 71–91 months), or 6 years, 7 months. The diversity of these school systems was well represented by the sample of children, with 47% of the families describing their ethnicity as Caucasian, 27% as African-American, 4% as Hispanic, 15% as Asian, and 7% as being of mixed ethnicity. Within the sample, 24% qualified for either free or reduced lunch.

Research Design

Child Assessments

Three assessments were made across the first-grade year (Time Points 1–3), in the fall, winter and spring. Each assessment included several memory tasks, was conducted at school by an experienced research assistant, and lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. Although the battery included a wide range of deliberate memory, event memory, and working memory tasks, in this report the focus is on three tasks: Digit Span (Jacobs, 1887), Object Memory (Baker-Ward, Ornstein, & Holden, 1984), and Sort-Recall with Organizational Training (Moely et al., 1992). The Digit Span task has been in use for more than 100 years and is included in many instruments for measuring intelligence. It is a simple assessment of deliberate memory for numbers that is taken as a measure of basic memory capacity. In contrast, the Object Memory task is used to assess the types of simple behavioral and linguistic strategies that children display while attempting to remember a set of stimulus objects. It provides measures of the spontaneous strategies that young children may deploy in the service of meeting a memory goal and serves as a point of reference for the more complex verbally-based mnemonic strategies (e.g., organized sorting and clustering) that are tapped by the Sort-Recall with Organizational Training task. This latter task also enables a contrast between children’s spontaneous organizational efforts and their performance after specific mnemonic training. All procedures were videotaped and/or audiotaped for subsequent analysis.

Classroom Observations

Extensive observations were carried out in each of the 14 classrooms, focusing especially on the nature of “teacher talk” about remembering, the memory demands that were expressed, the specific strategies that were discussed, and the expectations that were transmitted by the teachers. These observations were conducted during teacher-led lessons in two subject areas, language arts and mathematics. These two subject areas were chosen for observation because they impose contrasting mnemonic demands on learners. For example, lessons in language arts often require children to retrieve relevant information from memory and to make knowledge-based inferences. In contrast, instruction in mathematics often involves an emphasis on remembering per se (as in the memorization of arithmetic facts) and on providing children with problem-solving strategies. Two researchers observed for a total of 60 minutes in each area of instruction, making use of a dual-level coding system that is described in detail below.

Procedure

Assessments of Children’s Memory

To characterize the children’s mnemonic skill, three tasks were administered throughout the academic year. The Digit Span task provided a measure of basic memory capacity, whereas the Object Memory task indexed children’s spontaneous use of (largely behavioral) strategies for remembering and the Sort-Recall with Organizational Training task permitted an assessment of more complex verbally-based organizational strategies both before and after training.

Digit Span

Following standardized assessment procedures used with the Digit Span task (McCarthy, 1972), two forward span trials were administered. On each trial, strings of numbers of increasing length were presented, with the child’s task being that of repeating the numbers in sequence. The child’s span was measured as the length of the longest forward string of digits (out of the two administered trials) that could be produced without error. Two coders independently scored all records with any discrepancies being resolved through examination of the original coding sheet.

Object Memory

Each child was administered the Object Memory task adapted from an assessment developed by Baker-Ward et al. (1984). At each time point, the children were provided with 15 familiar objects (e.g., plastic toy animals or vehicles, or household items such as a mirror or brush) and instructed to do anything during a 2-minute study period that they thought would help them to remember the materials. After the study period, the objects were hidden with a cloth, and recall was requested. Multiple sets of items were created and counterbalanced, such that over the different time points, children saw different sets, each of which was designed so that the objects were unrelated and could not be grouped easily by color, function, or semantic category.

Measures of the children’s open-ended recall and strategy use were obtained at each time point. To characterize the simple strategies used by the children while trying to remember the objects, their behavior during the 2-minute study period was videotaped for later coding and analysis of behaviors typically elicited by instructions to remember, as opposed to instructions to play (Baker-Ward, 1985; Baker-Ward et al., 1984). Particular emphasis was placed on the amount of time spent engaged in the specific task-oriented behaviors that are displayed in Table 1. In order to establish reliability in the coding of these behaviors and the children’s recall, two coders independently scored 25% of the records from each time point and were required to obtain at least 80% agreement on each file. The percent agreement scores ranged from 80% to 99%, with an average of 86%, and the Kappas ranged from .72 to .98, with an average of .84. After reliability was established, one of the coders completed the remainder of the records.

Table 1.

Task-oriented Behaviors Coded in the Object Memory Task

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Association | A child verbalizes an association with or elaboration about an object (e.g., “I have a necklace like this”). |

| Categorization | A child groups two or more items together, either verbally or physically. The presence of the grouping category must be either obvious to the observer or identified verbally by the child. |

| Covert mnemonic activity | A child’s behavior suggests studying, as in moving the lips as if rehearsing, alternating between closing the eyes and looking at the objects, as in self-testing. |

| Manipulation | A child makes any type of manual contact with the objects that does not involve their unique properties. |

| Naming | A child provides any label – conventional or personal – for an object, without further description. |

| Object talk | A child discusses physical properties of an object (e.g. “These glasses are green”). |

| Pointing | A child points to the objects without touching or moving them. |

| Visual examination | A child scans the objects without touching any of them. |

Sort-Recall with Organizational Training

On each trial of this task that was modeled after that used by Moely et al. (1992), children were presented with 16 picture cards with line drawings that were taken from four conceptual categories, allowing for the assessment of organizational strategies at both input (e.g., sorting or grouping) and output (e.g., categorical clustering). At the first assessment point (Time 1) each child was given three trials of the Sort-Recall task, including baseline, training, and generalization assessments. At Times 2 and 3, the children were presented with a single non-instructed generalization trial.

On the baseline trial at Time 1, the picture cards were presented in a quasi-random order such that categorically-related items were not displayed contiguously, and the children were told to do whatever they could to remember the pictures. In contrast, on the subsequent training trial, the children were given instructions on how to use categorization during study (sorting) and recall (clustering) as aids to remembering. Further, the generalization trial at Time 1, administered after a 15-minute delay, involved the presentation of a new set of cards, allowing for an assessment of the continued use of strategies in the absence of specific instructions to do so. Moreover, additional assessments of generalization were obtained at Times 2 and 3.

In order to measure children’s sorting, recall, and clustering, the examiners recorded the children’s sorting placements, numbers of items recalled, and the order of items remembered. With this information, a standard index of categorical grouping, the Adjusted Ratio of Clustering (ARC) Score (Roenker, Thompson, & Brown, 1971), was calculated to characterize the children’s sorting during the study period and clustering in recall. The ARC scores could range from −1 (below chance organization), to 0 (chance), to 1 (complete categorization). Two coders independently scored all records, with any discrepancies being resolved through examination of the original videotapes.

Classroom Observations

To provide information about the classroom context, two researchers made observations on multiple occasions, one using the Taxonomy of Teacher Behaviors (see Appendix) that was specially developed to characterize teacher behaviors, and the other recording a full contextual narrative of the ongoing lesson and the children’s responses. The first observer used the Taxonomy to make judgments about the nature of each teacher’s memory-relevant conversation. At the same time, the second observer wrote an independent narrative account of the lesson as it unfolded, including descriptions of the content, the salient teacher and child activities, and the children’s verbal responses. With the Taxonomy, it is possible to make statements about the nature and extent of the teachers’ use of language that may be supportive of remembering, whereas the narrative coding system enables subsequent inferences about the nature of the memory demands being communicated in the classroom. More specifically, the narratives provide information about whether these demands or expectations are expressed or implied. In this way, it is possible to document the extent to which teachers verbally reference memory (e.g., “remember”; “don’t forget”) in the course of their lessons.

For each teacher, observations were made during a total of 240 30-second intervals, or 120 minutes of instruction, with 60 minutes each in language arts and mathematics. Coding decisions were made every 30 seconds, and following the recommendations of Cairns, Santoyo, Ferguson, and Cairns (1991), the taxonomy and narrative coders changed roles every five minutes. Moreover, to supplement the observers’ decision making, the observational periods were audiotaped. The lessons in these areas were often substantially less than a half hour in duration, and it took multiple trips to each classroom to accumulate the necessary time. Lessons ranged from 3 to 30 minutes of teacher-led instruction, and it took from 2 to 7 visits per teacher to collect 60 minutes of instruction in each subject area.

Taxonomy Coding System

The Taxonomy calls for the classification of each teacher’s conversation into four broad categories: instruction, cognitive structuring activities, memory requests, and metacognitive information:

Instruction

Several codes were employed to characterize the types of information provided by the teachers, such as giving specific task information, general information, or a prospective summary about an upcoming activity, or reading from a book. These Instruction codes were employed in situations in which the teacher offered information without requiring specific actions of her students.

Cognitive Structuring Activities

In contrast to Instruction, the Cognitive Structuring Activities codes were used for teacher talk that encouraged children to attend to or manipulate the materials in ways that are known to affect the encoding and retrieval of information. Cognitive Structuring Activities include attention regulation, massed repetition, identifying features, categorization, identifying relationships, making connections with personal experiences, drawing inferences, and visual imagery. As can be seen, some of these activities can be viewed as prompting deep levels of processing that have been explored in laboratory studies of memory (Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Hyde & Jenkins, 1969).

Memory Requests

These codes were employed when a teacher asked students to retrieve information already acquired or to prepare for future activities. Reports of experiences or prior knowledge could be episodic, semantic, or procedural. In contrast, requests involving the future could be prospective (defined as a behavioral goal), or anticipated (specified as a learning goal).

Metacognitive Information

These codes were used when a teacher either provided or solicited metacognitive information that might facilitate children’s performance on a range of classroom tasks (e.g., mathematics, reading, or remembering). To illustrate, a teacher could make a suggestion, provide a metacognitive rationale, or pose metacognitive questions. In contrast, sometimes a teacher may recommend suppression or replacement of a strategy.

In addition, a Non-Instructional/Non-Memory Relevant code was used to capture instances in which the teacher was not engaged in a memory or instructionally-relevant activity.

Narrative Coding System

Supplementing this coding of on-going teacher behavior, the observational narratives provide rich contextual information that permits interpretation of the memory-related questions (e.g., semantic, episodic, anticipated) posed by the teachers during the course of instruction. On the basis of the narrative notes, it was possible to characterize further the 30-second intervals that were coded according to the Taxonomy as containing “memory requests.” More specifically, the narratives provide information about whether these memory-related questions – now coded as “Deliberate Memory Demands” – were presented in an expressed form in which the goal of remembering was stated explicitly (e.g., “remember” or “don’t forget”) or whether it was simply implied by the need to retrieve information in order to answer a question (e. g., retrieving 4 from memory in response to a question such as “What is 2 + 2?”).

Given the use of the Taxonomy and the Narrative Coding System as the lessons unfolded, the classroom observers worked to attain a criterion of at least 80% reliability prior to the start of data collection. Each of five observers had extensive exposure to videotapes of teacher-led instruction and then independently coded 50 30-second intervals with the Taxonomy and an additional 50 with the Narrative Coding System. To assess reliability, the observers’ use of the Taxonomy and Narrative codes was compared to that of a master coder and measured in terms of percent agreement. The Taxonomy reliability scores ranged from 80% to 96%, with an average of 87%, whereas those obtained for the use of the Narrative system ranged from 92% to 100% and averaged 94%.

RESULTS

Overview

In the sections that follow, several aspects of the children’s abilities to recall, to utilize memory strategies, and to take advantage of training in organizational techniques are presented briefly, along with a description of the classroom context and a treatment of differences among the teachers in terms of their “mnemonic orientation.” In the final section, the memory skills of children in taught by first-grade teachers who are high versus low in their mnemonic orientation are contrasted, and hierarchical linear models are utilized to examine the hypothesized links between the classroom context and trajectories of children’s memory performance.

Overall Descriptive Summary of First Graders’ Memory Performance over Time

Preliminary Analyses and Overview

At each time point, at least 97% of the sample was seen, and for the children who were assessed, equipment failure led to the loss of only a few measures (range = 0 – 3). Although participant retention was quite high, a series of initial analyses was carried out to demonstrate that attrition and missing data did not impact systematically the characterization of the children’s performance that is reported below. A second set of analyses indicated no systematic differences in recall and strategy use as a function of gender, examiner, school, school district, or to-be-remembered materials. Accordingly, the data were pooled across these variables for subsequent analyses. First, to assess the children’s basic memory capacity, their performance on the Digit Span task is described. In addition, their scores on the Object Memory and Sort-Recall with Organizational Training tasks are characterized, focusing first on recall and then on strategy usage across the three measurement points during the first-grade year: Time 1 (Fall); Time 2 (Winter); and Time 3 (Spring). These data are presented descriptively to characterize changes at the group level over the first grade in memory skill and to provide a foundation for hierarchical linear modeling that enables exploration of linkages between aspects of the classroom and individual children’s recall and use of strategies.

Children’s Overall Mnemonic Skills

The overall sample means are presented in Table 2 in order to provide an initial overview of the children’s performance at each of the three time points across the first-grade year. Following a description of the children’s skills and an overall characterization of the classroom context, their performance on the memory tasks is described as a function of the teachers’ mnemonic style.

Table 2.

Children’s Memory Skills: Descriptive Statistics over Time

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digit Span | |||

| Longest forward string | 5.00 (.90) | 5.22 (.97) | 5.41 (1.02) |

|

| |||

| Object Memory task | |||

| Recall | 7.84 (1.99) | 7.66 (1.96) | 8.19 (2.07) |

| Strategy Composite | 119.85 (35.29) | 117.99 (32.04) | 125.50 (34.95) |

|

| |||

| Sort-Recall task | |||

| Recall | |||

| Baseline | 8.70 (2.65) | ||

| Training | 14.23 (1.54) | ||

| Generalization | 9.13 (3.60) | 10.27 (3.20) | 10.60 (3.28) |

| Sorting | |||

| Baseline | −0.03 (0.42) | ||

| Training | - | ||

| Generalization | 0.49 (0.59) | 0.50 (0.57) | 0.64 (0.53) |

| Clustering | |||

| Baseline | 0.40 (0.47) | ||

| Training | 0.83 (0.22) | ||

| Generalization | 0.65 (0.50) | 0.67 (0.35) | 0.65 (0.49) |

Note. Categorical organization during the training trial is not reported, as the examiner placed the cards for each child into the appropriate groups.

As can be seen in Table 2, there were modest increases in the children’s recall performance on the Digit Span, Object Memory, and Sort-Recall tasks. Moreover, the spontaneous behavior strategies observed in the Object Memory task appeared to change less across the first-grade year than did the trained verbally-based techniques assessed in the Sort-Recall task. In terms of the Object Memory task, the data were coded in terms of behaviors – such as association, categorization, covert mnemonic activity, manipulation, naming, object talk, pointing, and visual examination – that previous research (Baker-Ward et al., 1984) has indicated are associated with children’s response to a “remember” goal, as opposed to instructions to play with materials prior to an unexpected test of memory. As can be seen in Table 2, a substantial amount of time during the study period was consistently devoted to strategic behaviors (i.e., the components of a Combined Strategy Score) over the course of the year. In response to direct organizational training in the Sort-Recall task, the children’s sorting on the basis of meaning as assessed by the Adjusted Ratio of Clustering (ARC) measure (Roenker et al., 1971), increased dramatically over baseline performance. Moreover, not only did categorically-based sorting improve as a function of training, but it remained high and, in fact, increased somewhat over the remainder of the year. The children’s use of categorical clustering during recall also reflected dramatically the training received at Time 1, but in contrast to the increase in sorting over time, clustering performance on the three generalization trials was comparable.

A Characterization of Memory-Relevant Aspects of First-Grade Classrooms

Overview

In parallel with the assessments of the children’s memory performance, teacher-led instruction was observed and measured in terms of the numbers of 30-second intervals (out of a total of 3,360) in which the different behaviors included in the observational coding system were recorded. In the sections that follow, the Taxonomy and the Narrative coding systems are used to characterize the memory-relevant language that was used in the course of instruction. Information from the two coding systems was used to develop a measure of the teachers’ mnemonic orientation, so that linkages between the classroom context and children’s memory performance could be explored.

Taxonomy Coding: Characterizing Instruction in the Classroom

Reflecting the observers’ coding of teacher behavior with the Taxonomy, the data reported in Table 3 provide an overall picture of the types of teacher talk averaged across all 14 classrooms. In considering these data, it should be noted that multiple behaviors can be coded in each interval and, accordingly, that if one summed across the categories, the total would be greater than 100%. As would be expected, the children experienced a considerable amount of instruction, with 78.2% of the intervals containing some form of instruction. The teachers, moreover, spent much time on the provision of general information (41.8%) and specific task information (40.1%). In addition, 42.6% of the intervals included cognitive structuring activities. Although teachers devoted a considerable amount of time to attention regulation in the sense of changing the children’s behavior (18.6%), they were also able to engage in attention regulation in the service of instruction (14.1%). In addition, time was devoted to relating new material to prior experiences at school (8.1%), and some emphasis was placed on massed repetition (9.3%). Importantly, memory requests were quite frequent, with 52.6% of the intervals including some direct or indirect prompts for the storage and/or retrieval of information from memory. Indeed, the teachers asked a variety of questions that required the children to access information in semantic memory (47.0%) or episodic memory (4.0%), with fewer prompts that focused on the future. More specifically, teachers asked their children to remember academic information for future (anticipated) assessments of memory (2.3%) as well as to perform specific (prospective) actions in the future (0.8%). In contrast to instructional activities, cognitive structuring activities, and memory requests, the provision of metacognitive information was quite rare (9.5%), with approximately half of the intervals containing metacognitive information involving the provision of suggestions about strategies (4.9%) and/or the posing of metacognitive questions (4.9%).

Table 3.

Overall Percent Occurrence of Teacher Behaviors

| Taxonomy Codes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Overall percent occurrence | Range across teachers | |

| Instructional Activities – Category Total | 78.2% | 66.7% – 85.4% |

| Book Reading | 11.7% | 0.4% – 25.8% |

| General Information Giving | 41.8% | 31.7% – 59.6% |

| Prospective Summary | 7.0% | 2.1% – 12.5% |

| Specific Task Information | 40.1% | 28.3% – 52.5% |

|

| ||

| Cognitive Structuring – Category Total | 42.6% | 26.3% – 62.5% |

|

| ||

| Attention Regulation- Behavioral Goal | 18.6% | 3.3% – 32.5% |

| Attention Regulation- Instructional Goal | 14.1% | 6.7% – 20.0% |

| Massed Repetition | 9.3% | 0.0% – 29.6% |

| Identifying Features | 4.5% | 0.4% – 13.3% |

| Categorization | 2.2% | 0.0% – 9.2% |

| Identifying Relationships | 6.3% | 0.8% – 14.2% |

| Connections- Personal Experiences at Home | 2.0% | 0.4% – 5.8% |

| Connections- Personal Experiences at School | 8.1% | 1.7% – 15.0% |

| Drawing Inferences | 3.9% | 0.4% – 7.9% |

| Visual Imagery | 0.3% | 0.0% – 1.3% |

|

| ||

| Memory Requests – Category Total | 52.6% | 42.5% – 61.3% |

|

| ||

| Episodic | 4.0% | 0.4% – 10.4% |

| Semantic | 47.0% | 32.9% – 59.6% |

| Procedural | 1.3% | 0.0% – 3.8% |

| Prospective | 0.8% | 0.0% – 2.5% |

| Anticipated | 2.3% | 0.4% – 5.4% |

|

| ||

| Metacognitive Instruction – Category Total | 9.5% | 2.5% – 19.2% |

|

| ||

| Metacognitive Rationale | 1.2% | 0.0% – 5.0% |

| Metacognitive Questioning | 4.9% | 0.8% – 9.6% |

| Suggestion | 4.9% | 0.8% – 13.8% |

| Suppression | 0.1% | 0.0% – 0.4% |

| Replacement | 0.1% | 0.0% – 0.4% |

|

| ||

| Narrative Coding of Memory Demands | ||

| Implied Deliberate Memory Demands | 47.3% | 36.7% – 56.3% |

| Expressed Deliberate Memory Demands | 5.4% | 2.1% – 10.4% |

Note. The overall percent occurrence for teacher behaviors is based on a total of 3,360 coded intervals.

Narrative Coding: Nature of the Memory Demand

Supplementing this depiction of the teacher talk, the coded narratives permitted a characterization of the mnemonic goals that were presented to the children. To some extent, of course, the codes derived from the narratives are not independent of those obtained with the use of the Taxonomy. For example, teacher talk that would be categorized as involving a memory request in the Taxonomy would be captured in the narratives and classified later as involving either an expressed or implied deliberate memory demand.

Moreover, the assessment of the narratives yielded a view of the classroom that was similar to earlier observations (e.g., Mercer, 1996; Moely et al., 1992). Thus, even though teachers rarely informed their students that remembering was an expressed goal, they frequently demanded that children make use of their memory. Expressed deliberate memory demands in which teachers explicitly asked the children to “remember” or not to “forget” were observed in only 5.4% of the 3,360 intervals, but implied deliberate memory demands were seen in 47.3% of the intervals (1,589/3,360). Thus, consistent with the Taxonomy coding, deliberate memory demands were seen in 52.7% of the intervals.

In addition, these two sets of coding decisions can be linked, so as to examine the specific teacher behaviors (as judged by the use of the Taxonomy) that occurred when particular memory demands or goals were being expressed (as determined by the coding of the narratives). For example, 37.6% of the total intervals contained both a deliberate memory demand and some instructional activity. In addition, 5.9% of the total intervals contained some deliberate memory demand and some use of metacognitive information.

Developing a Teacher Measure

The participating teachers varied both in the types of behaviors coded using the Taxonomy and in the extent to which they presented deliberate memory demands to their students. Indeed, as can be seen in Table 3, across the classrooms the use of implied deliberate memory demands ranged from 36.7% to 56.3%, and the degree to which expressed deliberate memory demands were presented varied between 2.1% and 10.4%. Interestingly, within the domain of memory requests, considerable variability was observed in terms of making a request that involved the retrieval of semantic or generic information (range= 32.9% to 59.6% of intervals observed). Similarly, the use of metacognitive questioning (range= 0.8% to 9.6%), the provision of a metacognitive rationale (range= 0 to 5.0%), and suggestion (range= 0.8% to 13.8%) all varied markedly across the 14 classrooms.

On the basis of these classroom differences, a composite measure of the “mnemonic orientation” that is reflected in the participating classrooms was developed. Drawing in part on analysis of teacher behaviors thought to foster the development of memory (Mercer, 1996; Moely et al., 1992), the resulting index of “mnemonic orientation” is based on a subset of codes from the two observational systems. In constructing this measure, the aim was to capture the ways in which the teachers’ lessons were supported by the provision of both metacognitive information and requests for deliberate remembering. Although the establishment of memory goals in the classroom is clearly important, the focus here is not on the goals per se but rather on aspects of “teacher talk” that accompany and support this orientation. More specifically, the index of teacher “mnemonic orientation” is based on the frequency of (1) strategy suggestions and of (2) metacognitive questioning across the 240 intervals for each teacher, as well as the co-occurrence of deliberate memory demands with (3) instructional activities, (4) cognitive structuring activities and (5) metacognitive information. Thus, even though strategy suggestions and metacognitive questions were not observed frequently, they nonetheless were included in the index because they could influence the ways in which children approach a range of cognitive tasks in the classroom. In addition, the potential importance of exposing children to information in the course of a lesson, of providing opportunities for cognitive structuring, and of presenting metacognitive information could be enhanced when accompanied by a deliberate memory demand. Accordingly, the codes reflecting the co-occurrence of these components of “talk” during instruction with the provision of deliberate memory demands are included in the measure of mnemonic orientation.

Illustrations of each of these five codes can be seen in Table 4. Inspection of the table also indicates that there is considerable variation across the 14 classrooms, reinforcing the view that some composite index would characterize effectively the differences in the teachers’ mnemonic orientation. However, because the average rates of occurrence of the codes also vary substantially, it was necessary to compute standard scores for each code before the values could be combined in a composite index. Accordingly, each code was standardized based on its mean and standard deviation, and the resulting T-scores for each of the five measures were then averaged to generate a “mnemonic orientation” score that could be used to contrast the different classrooms. The mean of the resulting T-scores was 50 (SD = 7), with a range of 40.36 to 64.01, and the teachers were divided into two groups (high and low mnemonic orientation) on the basis of a median split. Although it certainly is the case that mnemonic orientation may be distributed continuously in the population of first-grade teachers, the relatively small sample of classrooms (n = 14) in which observations were made prompted a contrastive strategy of forming groups of teachers who differed clearly in the ways in which memory was reflected in their classrooms. It should be emphasized that the two groups of teachers with contrasting levels of mnemonic orientation were nonetheless similar on a range of demographic characteristics, including age (34.9 years versus 37.7 years, for the low and high groups respectively), years of overall teaching experience (9.21 years versus 11.38 years), and years of teaching in the first grade (7.57 years versus 7.38 years), ts (13) ≤.53, ps ≥ .61. The two groups were also similar in terms of their educational levels, with three teachers in the low mnemonic group and two in the high mnemonic group having Master’s degrees.

Table 4.

Percentage of Intervals and Examples of Codes in Teacher Mnemonic Orientation Score

| Teacher Behaviors | Mean (SD) | Range | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy Suggestions | 4.9 % (3.6%) | 0.8 – 13.8% | “If that doesn’t make sense, go back and reread or look at the picture.” |

| Metacognitive Questioning | 4.9 % (2.7 %) | 0.8 – 9.6% | “What are some strategies you could use to help you figure that out?” |

| Deliberate Demand and Instructional Activities | 37.6 % (8.3 %) | 25.8 – 50.0% | “Today we are going to write a story about our field trip to the zoo. What was the first thing we did when we got there? Remember, a story has a beginning, middle, and end.” |

| Deliberate Demand and Cognitive Structuring Activities | 23.5 % (8.1 %) | 10.0 – 35.4% | “Yesterday we talked about states of matter. What are the three forms that water can take?” |

| Deliberate Demand and Metacognitive Information | 5.9 % (3.8 %) | 1.3 – 12.1% | “How many seashells are there in all? How did you solve that problem? How did you know that you should add?” |

Linking the Classroom Context to the Children’s Memory Performance

Given these teacher differences in mnemonic orientation, it is possible to examine the performance of children nested into each type of classroom. The contrasting performance of these two groups of children will first be described and then will be explored with a series of hierarchical linear models (HLMs: Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Characterizing Memory Performance as a Function of the Teachers’ Mnemonic Orientation

The 46 children in the classes taught by low mnemonic teachers and the 61 participants in those of the high mnemonic teachers did not differ at any assessment point on the Digit Span measure of basic capacity. The children in the classes taught by low mnemonic teachers had an average digit span (longest forward string) of 5.26, whereas that of the children taught by high mnemonic teachers was 5.16, t(100) = .36, p = .72. With this equivalence established, however, the children in classes taught by teachers with contrasting mnemonic orientations did differ in their use of memory strategies and in the amount of information they recalled in these tasks by the end of the first-grade year.

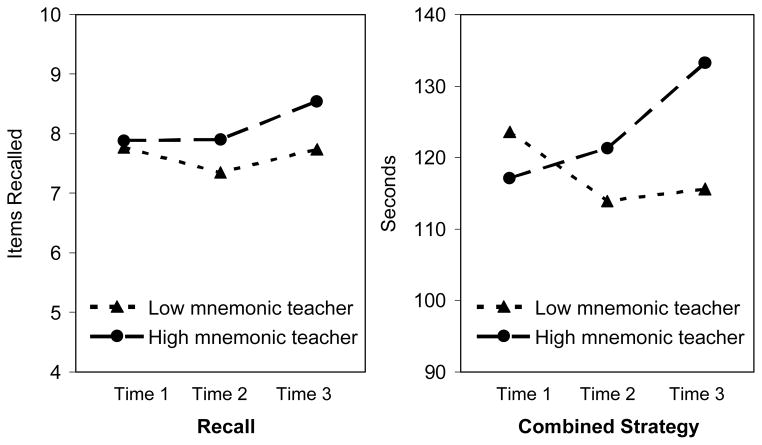

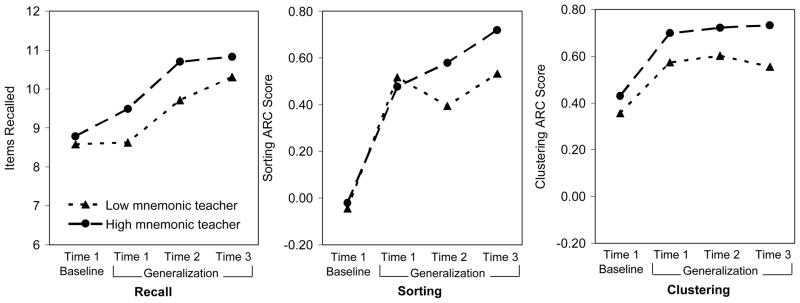

As can be seen in Figure 1, the children taught by high versus low mnemonic teachers differed in both recall and the use of strategies on the Object Memory task. For example, as displayed in the left panel of Figure 1, the two groups exhibited different patterns of recall over time, such that after the first time point the children in the high mnemonic classes evidenced greater recall than their peers in the low mnemonic classes. Similar group differences in strategy use, as reflected in the Combined Strategy Score, are evident in the right panel of Figure 1. Different patterns also emerge on the Sort-Recall task. As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the recall performance of both groups improves somewhat as a function of training at Time 1. In contrast, however, more pronounced group differences are observed in the use of organized sorting during the study period and the categorical clustering in recall, and these patterns are displayed in the middle and right panels of Figure 2. Although these strategies were very infrequently used by the children in either group on the baseline trial of Time 1, the children drawn from these contrasting classrooms differed markedly in their ability to take advantage of organizational training such that clear differences in performance were apparent by Time 2.

Figure 1.

The number of items recalled and the number of seconds engaged in strategic behaviors on the Object Memory task, over time, as a function of teachers’ mnemonic orientation.

Figure 2.

The number of items recalled, sorting ARC scores, and clustering ARC scores on the Sort-Recall with Organizational Training task, over time, as a function of teachers’ mnemonic orientation.

Modeling Classroom Differences in Memory Performance

Analytic Strategy

In order to examine more formally developmental trajectories in recall and strategy use, a series of hierarchical linear models (HLMs) (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was employed with individual estimates of growth curves, using SAS Proc Mixed (SAS Institute, 1992), allowing for the estimation of both fixed and random effects. HLMs were utilized because they allow for the examination of complex multilevel, longitudinal data with the structure of repeated measures within children, and children nested within classrooms. These models permit a longitudinal exploration of trajectories of individual children over time, of individual variability in these trajectories, and of predictors, such as the measure of the classroom context, of variability in rates of change across classrooms.

As is customary in the HLM framework (e.g., Singer & Willett, 2004), a series of unconditional models was first estimated, capturing the individual growth trajectories (intercepts and slopes) of each of the five outcome variables being examined, namely recall and Combined Strategy Scores in the Object Memory task, and recall, sorting, and clustering scores in the Sort-Recall task. These estimates were of the overall group growth trajectories, averaged across all children in all classrooms for each of these five aspects of children’s memory performance. The purpose of these models was to establish a baseline for the amount of variance to be explained in each measure, in order to determine if the defined intercept was statistically different from zero and if there was significant growth over time (linear rate of change). Finally, it was necessary to assess if there was significant individual variability in the intercepts as well as in the rates of change over time, so as to determine if predictors could be incorporated into the models to account for that variability. Thus, multilevel linear growth curve models that were estimated were defined by an intercept (coded as performance at Time 3) and the linear effect of time. The intercept was defined as Time 3 in the spring of the first grade because it enabled the assessment of differences at the end of the school year, after children had been in the classroom for most of the academic year.1 Fixed and random components for the trajectory components were estimated, and a 95% confidence interval size was used throughout the paper.2

Unconditional Models

As can be seen in Table 5, the results of the unconditional growth models indicated that for all five of the outcome variables of interest, there were significant fixed effects for the intercept (as defined at Time 3), suggesting that the values of each were different from zero. In addition, there were significant fixed and random effects in the slope of the developmental trajectory of sorting, clustering, and recall in the Sort-Recall task. (It should be noted that because of the relatively flat trajectories of the recall and the Combined Strategy Score measures in the Object Memory task seen earlier, there was no significant change over time in these measures).

Table 5.

Results of the Hierarchical Linear Model Analysis [Unconditional]

| Final estimation of fixed effects | Coefficient | SE | t | df | p | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Object Memory Task Recall | |||||||

| Intercept | 8.08 | 0.19 | 41.90 | 106 | <0.0001 | 7.70 | 8.46 |

| Slope | 0.18 | 0.11 | 1.59 | 207 | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.41 |

|

| |||||||

| Object Memory Task Strategy | |||||||

| Intercept | 125.11 | 3.46 | 36.12 | 106 | <0.0001 | 118.25 | 131.98 |

| Slope | 3.22 | 2.16 | 1.49 | 202 | 0.14 | −1.04 | 7.48 |

|

| |||||||

| Sort-Recall Task Recall | |||||||

| Intercept | 10.80 | 0.32 | 34.26 | 106 | <0.0001 | 10.18 | 11.42 |

| Slope | 0.95 | 0.17 | 5.51 | 207 | <0.0001 | 0.61 | 1.29 |

|

| |||||||

| Sort-Recall Task Sorting | |||||||

| Intercept | 0.71 | 0.06 | 12.48 | 106 | <0.0001 | 0.59 | 0.82 |

| Slope | 0.34 | 0.03 | 10.62 | 204 | <0.0001 | 0.27 | 0.40 |

|

| |||||||

| Sort-Recall Task Clustering | |||||||

| Intercept | 0.70 | 0.05 | 15.26 | 106 | <0.0001 | 0.61 | 0.79 |

| Slope | 0.13 | 0.03 | 3.93 | 207 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

Note. Intercepts and slopes did vary randomly, although only fixed effects are presented here.

Object Memory

The aim of the first step in hierarchical linear modeling was to determine if there was variability across children – without regard to their group placement – at Time 3 performance (intercept) and in the rate of change over time (slope) that could potentially be accounted for by the classroom context. In the fixed effects analyses of the children’s recall performance, the model-implied average at Time 3 was 8.08 items, and the estimate for the linear expected increase was only .18 items per time point. Although the overall intercept coefficient was different from zero (p < .001), the linear growth rate was not (p = .113), illustrating that there is no significant change in the slope to be predicted. Similarly, the average intercept value for the Combined Strategy Score measure in the Object Memory task, was 125.11 seconds of engagement in strategic behaviors, with a linear growth rate of 3.22 seconds over each time point, suggesting that there are significant fixed effects for the intercept (p < .001) but not for the rate of change (p = .140). This application of unconditional models to the Object Memory data indicate that there are important individual differences in the children’s performance (as reflected in the intercepts, but not the slopes) that may be accounted for by teacher mnemonic orientation in conditional models.

Sort-Recall with Organizational Training

Parallel unconditional modeling of the recall, sorting, and clustering data in the Sort-Recall task revealed that both the intercepts (Time 3 performance) and rates of change were significantly different from zero and that significant variability existed around these parameters. To illustrate, the model-implied overall trajectory for recall had an intercept of 10.80 items, with a linear growth rate of .95 items, (ps < .001). Similarly, this trajectory for sorting had an ARC score estimate of .71 at Time 3, with a linear growth rate of .34 (ps < .001), and the application of the unconditional model to the clustering data revealed a model-implied intercept of .70 at Time 3, with a .13 unit linear rate of change (ps < .001). Thus, for each of these measures, significant fixed effects were found for each of the two parameters (intercept and slope), revealing differences from zero. Moreover, significant random effects were seen for each of the three intercepts and the three slopes (ps <.01), indicating that there was variability around each of the group means to be predicted.

Conditional Models and the Impact of Mnemonic Orientation

Given the presence of individual differences in the children’s trajectories over time, it was possible to examine the impact of the teachers’ mnemonic style on the (1) mean performance at the end of the first grade and (2) rates of change over the academic year. Therefore, for each of the five outcome measures, a conditional model with a teacher-level predictor was estimated, allowing for examination of differences in the recall and strategy use of children drawn from classrooms with high versus low mnemonic orientations. The five sets of conditional model estimates are displayed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of the Hierarchical Linear Model Analysis [Conditional]

| Final estimation of fixed effects | Coefficient | SE | t | df | p | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Object Memory Task Recall | |||||||

| Intercept | 7.60 | 0.29 | 26.49 | 105 | <0.0001 | 7.04 | 8.17 |

| Time | −0.01 | 0.17 | −0.07 | 206 | 0.94 | −0.36 | 0.33 |

| Group | 0.84 | 0.38 | 2.21 | 105 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 1.60 |

| Time X Group | 0.34 | 0.23 | 1.49 | 206 | 0.14 | −0.11 | 0.80 |

|

| |||||||

| Object Memory Task Strategy | |||||||

| Intercept | 114.91 | 5.09 | 22.59 | 105 | <0.0001 | 104.83 | 125.00 |

| Time | −3.31 | 3.20 | −1.03 | 201 | 0.30 | −9.61 | 3.00 |

| Group | 18.15 | 6.79 | 2.67 | 105 | 0.01 | 4.70 | 31.61 |

| Time X Group | 11.52 | 4.24 | 2.72 | 201 | 0.01 | 3.16 | 19.88 |

|

| |||||||

| Sort-Recall Task Recall | |||||||

| Intercept | 10.40 | 0.43 | 24.37 | 105 | <0.0001 | 9.55 | 11.25 |

| Time | 0.87 | 0.26 | 3.30 | 206 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 1.39 |

| Group | 0.72 | 0.57 | 1.26 | 105 | 0.21 | −0.41 | 1.84 |

| Time X Group | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 206 | 0.67 | −0.54 | 0.83 |

|

| |||||||

| Sort-Recall Task Sorting | |||||||

| Intercept | 0.58 | 0.08 | 6.90 | 105 | <0.0001 | 0.41 | 0.75 |

| Time | 0.29 | 0.05 | 6.01 | 203 | <0.0001 | 0.20 | 0.39 |

| Group | 0.22 | 0.11 | 1.92 | 105 | 0.057 | −0.01 | 0.44 |

| Time X Group | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.26 | 203 | 0.21 | −0.05 | 0.21 |

|

| |||||||

| Sort-Recall Task Clustering | |||||||

| Intercept | 0.60 | 0.07 | 8.75 | 105 | <0.0001 | 0.47 | 0.74 |

| Time | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.94 | 206 | 0.05 | −0.00 | 0.20 |

| Group | 0.18 | 0.09 | 1.96 | 105 | 0.05 | −0.00 | 0.36 |

| Time X Group | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.86 | 206 | 0.39 | −0.07 | 0.19 |

Note. Intercepts and slopes did vary randomly, although only fixed effects are presented here.

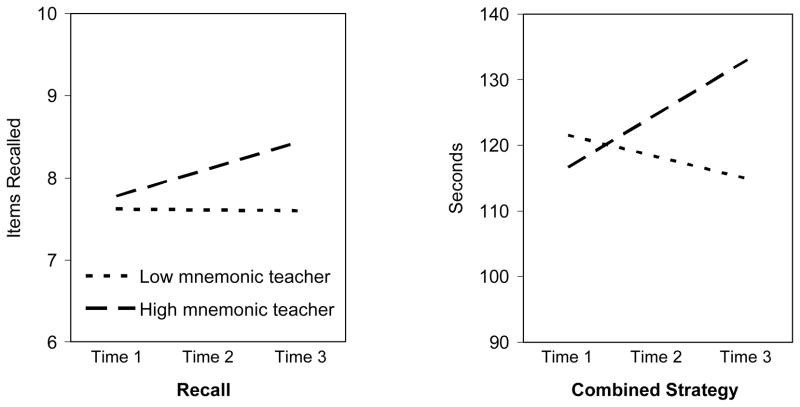

By the end of year, the teachers’ mnemonic orientation was associated significantly with the children’s recall and strategy use on the Object Memory task. As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 3, at Time 3 the children taught by the two groups of teachers differed in recall performance, as the model-estimated means were 7.60 and 8.44 items for the low and high mnemonic groups, respectively (p = .029). Similarly, inspection of the right panel of Figure 3 indicates that the average Combined Strategy Score differed as a function of teacher mnemonic orientation, with the model estimated means for the low and high groups being 114.91 and 133.06 seconds, respectively (p = .009). Moreover, the children taught by these two groups of teachers differed in their linear rates of change (low group = −3.31 and high group = 8.21) over the course of the first-grade year (p = .007), with higher teacher mnemonic orientation being associated with steeper (and positive) rates of change over time.

Figure 3.

Model-implied trajectories of the numbers of items recalled and the number of seconds engaged in strategic behaviors on the Object Memory task, over time, as a function of teachers’ mnemonic orientation.

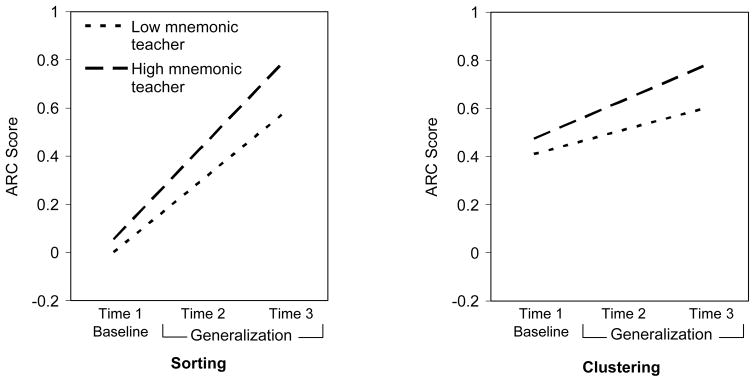

In contrast to the Object Memory task, in the Sort-Recall task there were effects of teacher mnemonic orientation on both of the measures of strategy use, but not on children’s recall. As illustrated in the left panel of Figure 4, the model-estimated intercepts of the sorting scores at Time 3 were .58 and .80 for the children taught by low and high mnemonically oriented teachers, respectively, a difference that was marginally significant (p = 0.057). In contrast, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the rates of change in sorting over the course of the year. Similarly, in clustering, the conditional model results suggested that there were statistically significant differences in the group means as a function of teacher mnemonic orientation at Time 3 (low group X = .60; high group X = .78, p = .053), but that there were no differences in the rates of change over the course of the year.

Figure 4.

Model-implied trajectories of strategy use, both sorting ARC scores and clustering ARC Scores, on the Sort-Recall with Organizational Training task, over time, as a function of teachers’ mnemonic orientation.

Taken together, these model results suggest that the children’s developmental trajectories on three different measures of strategy deployment on two tasks exhibited linear trends over the first-grade year and that there was important individual variability in the Time 3 means and in the linear rates of change over time. Moreover, the high versus low mnemonic orientation of the children’s teachers predicted a significant proportion of this variability. In contrast, although there was variability in the children’s patterns of recall over the year, teacher mnemonic orientation was only associated with performance on the Object Memory task.

DISCUSSION

Children’s Memory Performance

The design of this longitudinal study has enabled a detailed description of first-graders’ memory performance over a one-year period. By focusing principally on the Object Memory and Sort-Recall tasks and describing children’s performance both within and across time points, it was possible to generate an in-depth picture of recall and strategy use over the course of the first grade. Minimal changes over time were seen in the children’s recall in these two tasks, but substantial gains were made in the deployment of several memory strategies, especially in terms of children’s ability to generalize training in the utilization of organizational strategies in the context of the Sort-Recall task. Children’s recall, sorting, and clustering performance on this task increased sharply as a function of training at Time 1, and their use of sorting and clustering remained significantly higher than baseline over time. Independent strategy use in the Object Memory task also increased substantially over the course of the first-grade year.

The Classroom Context

To some extent, the memory-related aspects of the language used by the first-grade teachers were similar to those observed previously by Moely et al. (1992; see also Mercer, 1996). For example, the teachers rarely informed students that remembering was an expressed goal, but they nonetheless often seemed to require the active use of memory. Expressed deliberate memory demands in which teachers explicitly asked the children to “remember” or not to “forget” were observed in only 5.4% of the 3,360 observational intervals, but implied deliberate memory demands were seen in 47.3% of the intervals. Thus, memory permeates the classroom environment, with teachers frequently making requests of their students that require them to recall information from memory. In addition, even though teachers regularly engaged in cognitive structuring activities that could be seen as increasing the depth to which information was processed, they nonetheless provided relatively little direct instruction in the use of specific strategies.

Importantly, observations in the classrooms revealed substantial differences among the teachers in ways in which their students were exposed to memory demands, strategy suggestions, and metacognitive information. Not only was there variability across teachers in the extent to which memory goals were made explicit (e.g., in the use of language such as “don’t forget”), there were also differences in terms of the ways in which requests for remembering (both expressed and implied) were accompanied by language that would be thought to influence the depth to which information is processed. More specifically, when teachers seemed to have a deliberate goal of remembering in mind, they differed substantially in the extent to which they also engaged in instructional and cognitive structuring activities, and provided metacognitive information. These important differences in classroom context were associated with variation in aspects of the children’s use of mnemonic techniques, perhaps because they provided contrasting opportunities for students to approach various cognitive tasks and to learn about the importance of remembering.

Linking the Classroom Context to the Children’s Memory Performance

These pronounced differences in the use of language in the classroom enabled the measurement of the teachers’ mnemonic style and the identification of two distinct groups of teachers that were high and low in their orientation. Moreover, variation among teachers in their mnemonic style was associated with corresponding differences in their students’ skills for remembering by the spring of their first-grade year. More specifically, examination of both the group means and HLM model-implied estimates illustrated linkages between children’s individual memory performance and the mnemonic orientation of the classroom context in which they were embedded. These differences were especially pronounced in the generalization of training in sorting and clustering strategies in the Sort-Recall task over the course of the year and in a composite strategy measure in the Object Memory task. Classroom differences in children’s use of strategies for remembering are particularly interesting given that children taught by high versus low mnemonic teachers did not differ at any point during the academic year on the Digit Span measure of basic capacity.

Limitations and Future Directions

The demonstration of a linkage between the teachers’ mnemonic orientation and the children’s memory performance provides useful information about the important classroom context in which children’s memory skills are honed. Indeed, the longitudinal findings obtained here replicate and extend in important ways the cross-sectional work of Moely and her colleagues (1992). The observation that the children taught by teachers who differ in their mnemonic orientation exhibit contrasting profiles of mnemonic skill over the course of the first grade reinforces the basic notion that the school context is of critical importance for the development of children’s memory. Nonetheless, it must be recognized that the classification of teachers into the high and low mnemonic groups represents an initial approach to the task of describing the classroom context that was done on the basis of a measure that reflected the use of a specific subset of observational codes. As such, it is possible that alternative characterizations of teachers’ memory-relevant language may yield greater insights into the impact of the classroom on children’s developing repertoire of cognitive skills.

In addition to exploring further ways of measuring the mnemonic orientation of classroom teachers, it is also important to examine the extent to which characteristics of the children themselves may also be associated with the development of skill. The importance of child-level factors in understanding the acquisition of memory strategies is suggested by the HLM analyses described in the Results. More specifically, even after teachers’ mnemonic orientation was included in the models, there remained important variability in the children’s trajectories, suggesting the need to consider additional measures (e.g., children’s academic achievement and self regulation skills) as predictors of memory development. Putting classroom and child-level factors together, it is also important to focus attention on the mechanisms that may underlie children’s developing skills in the context of the classroom. Simply put, what is the process by which an individual child in a class taught by a high mnemonic teacher comes to be more proficient in the application of a grouping or clustering strategy than a peer who is taught by a low mnemonic teacher? To what extent does the high mnemonic teacher create a context for strategy discovery and utilization, or, alternatively, for the generalization of techniques from one area – such as reading or arithmetic – to remembering?

Although much remains to be learned about associations between the classroom context and children’s developing mnemonic skills, the present findings reinforce the importance of using longitudinal research designs to study the development of memory and to identify contexts that are associated with developmental change. However, it must be emphasized that the non-experimental nature of this research makes it impossible to make causal inferences about the impact of the classroom environment. Within the context of research on preschoolers’ autobiographical memory (e.g., Boland, Haden, & Ornstein, 2003; McGuigan & Salmon, 2004; Ornstein, Haden, & Hedrick, 2004; Reese & Newcombe, 2007), longitudinal and experimental research methods have been combined effectively to demonstrate causal connections between parent-child conversations and children’s recall of specific events. In a similar fashion, it seems likely that this strategy – involving experimental manipulations of aspects of teacher communicative style – would be useful in exploring the impact of the classroom on children’s developing skills for remembering. In addition to enabling causal inferences, small-scale studies in which teachers are trained in the use of conversational techniques employed spontaneously by high mnemonic teachers can lead to broad interventions that have the potential to facilitate the acquisition of strategies for remembering among large numbers of elementary school children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (BCS-0217206) to the second author, as well as a Predoctoral Fellowship provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HD07376) through the Center for Developmental Science, UNC-CH, to the first author. The authors wish to express their sincere appreciation to the participating teachers, schools, and families for their enthusiastic support of this work. In addition, technical assistance was provided by Rebecca Abu Ayed, Cary Chen, Astrid Ertola, Heather Fuller, Jennie Grammer, Pooja Gupta, Stephanie Guthrie, Carolyn Monsma, Veronica Pamparo, Sandy Pham, and Priscilla San Souci and is gratefully acknowledged. Finally, the authors wish to thank the four anonymous reviewers and Dr. Catherine McBride-Chang, the associate editor, for very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this report.

APPENDIX: CLASSROOM OBSERVATIONS

During classroom observations, one observer utilizes the Taxonomy of Teacher Behavior to code teacher language, while another simultaneously writes a contextual narrative of classroom activities.

A. The Taxonomy of Teacher Behavior

The Taxonomy classifies teacher conversation into four broad categories: instruction, cognitive structuring activities, memory requests, and metacognitive information.

1. Instruction

Instruction codes are used when a teacher provides specific task information (e.g., how to form the letter W); general information (e.g., in describing a frog’s habitat); a prospective summary about an upcoming activity (e.g., alerting the class to a field trip next week); or if she reads from a book.

2. Cognitive Structuring Activities

These codes capture teacher talk that encourages children to engage materials in ways that have been found in laboratory studies to prompt deep levels of processing and to affect the encoding and retrieval of information (Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Hyde & Jenkins, 1969). Examples of Cognitive Structuring Activities include attention regulation (e.g., regulating behavior or focusing attention), massed repetition (e.g., performing an action in unison), identifying features (e.g., circling the “it” family words), categorization (e.g., sorting by shape or color), identifying relationships (e.g., comparing and contrasting water and ice), making connections with personal experiences (e.g., relating a current activity to a child’s previous experience), drawing inferences (e.g., asking what might happen next in a story), and visual imagery (as in imagining oneself as an animal).

3. Memory Requests

These codes are employed when a teacher asks students to retrieve information or to prepare for future activities. Such requests can be episodic (e.g., retrieval of an event: “What did you do at your birthday party?”), semantic (e.g., report of a learned fact: “What comes after 10?”), procedural (e.g., recalling how to perform an action: “How do we set up the tape recorder?”) or involving the future with either a prospective (e.g., a behavioral goal: “Bring your lunch money tomorrow!”), or an anticipated request (e.g., a learning goal: “Remember this set of numbers.”).

4. Metacognitive Information

These codes are used when teachers provide or solicit metacognitive information with the goal of facilitating children’s performance. Teachers may offer a metacognitive rationale (e.g., “Reading the word problem twice is helpful because as you get older the problems will get more complicated”), use metacognitive questioning (e.g., “How did you study those words?”), or make a suggestion (e.g., “If you make a picture in your mind, it will help you to remember.”). In contrast, a teacher might use suppression of a strategy (“Don’t count on your fingers.”), and may suggest a replacement (e.g., “Don’t erase your mistakes. Just cross them out.”).