Abstract

Organic transformations that result in the formation of multiple covalent bonds within the same reaction are some of the most powerful tools in synthetic organic chemistry. Nitrosocarbonyl hetero-Diels–Alder (HDA) reactions allow for the simultaneous stereospecific introduction of carbon–nitrogen and carbon–oxygen bonds in one synthetic step, and provide direct access to 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines. This Review describes the development of the nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction and the utility of the resulting oxazine ring in the synthesis of a variety of important, biologically active molecules.

Keywords: cycloaddition, Diels–Alder reactions, nitrosocarbonyl compounds, oxazines, synthetic methods

1. Introduction

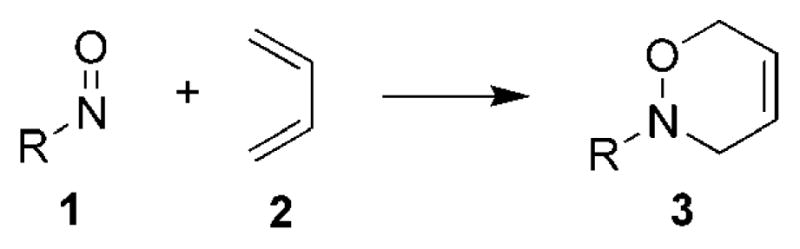

The nitroso hetero-Diels–Alder (HDA) reaction provides access to 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines 3 from nitroso compounds 1 and dienes 2 (Scheme 1). The high regio- and stereoselective installment of nitrogen and oxygen functionality to 1,3-diene systems has resulted in the nitroso HDA reaction often being an important step in the synthesis of natural products and biological molecules.[1,2] Many aspects of the nitroso HDA reaction have been reviewed, ranging from the application of nitroso HDA reactions for the synthesis of azasugars,[3] HDA reactions with acylnitroso derivatives of amino acids,[4] asymmetric nitroso HDA reactions,[5,6] and the use of nitroso HDA reactions in natural product syntheses.[1,7]

Scheme 1.

The nitroso hetero-Diels–Alder reaction.

While these reviews have demonstrated the importance of the nitroso HDA reactions in numerous synthetic endeavors, the chemistry surrounding the nitroso HDA reaction and the resulting 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazine functionality has not been described in detail within the literature. This Review will detail the rich chemistry of nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions and their subsequent transformations to generate useful, biologically important molecules.

2. Nitroso Compounds

The nitroso functional group has been intensively studied since the first synthesis of nitrosobenzene by Baeyer more than one hundred years ago.[8] An early report found that nitroso compounds could add to activated methylene groups to form azomethine compounds (the Ehrlich–Sachs reaction),[9] and since this discovery, the nitroso group has been found to participate in nitroso aldol reactions,[10–13] ene reactions,[14] hetero-Diels–Alder reactions, and other fundamental organic processes.[7]

2.1. C-Nitroso Compounds and Simple Nitroso Compounds

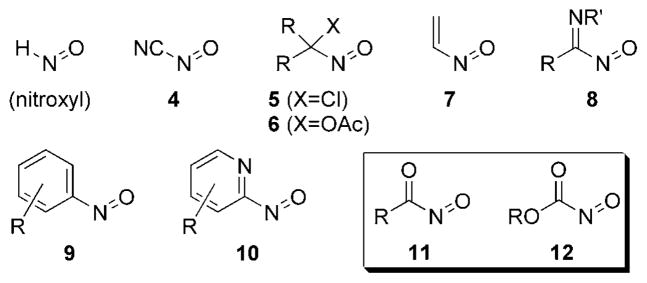

The simplest nitroso compound, nitroxyl or hyponitrous acid (HNO), has seen limited use in cycloaddition reactions because of its high propensity to dimerize with loss of H2O to form nitrous oxide.[15,16] In contrast, C-nitroso compounds have been used extensively as dienophiles in cycloaddition reactions (Figure 1).[4,10,17] Cyanonitroso (4),[17] arylnitroso (9), pyridylnitroso (10),[18] α-halonitroso (5),[19–21] α-acetoxy-nitroso (6),[22,23] vinylnitroso (7), iminonitroso (8),[24] acylnitroso (11),[17] and nitrosoformate ester 12[25] compounds are all commonly used in HDA transformations.

Figure 1.

Examples of C-nitroso compounds.

The arylnitroso compounds 9 were among the first discovered, and are stable reagents that react slowly with dienes in [4+2] cycloaddition reactions.[4] Electron-withdrawing groups on the aromatic ring were found to greatly accelerate the reaction.[17] Similar effects were observed for nitrosoalkane compounds that were substituted at the α position, such as chloronitroso species 5[19–21] and acetoxynitroso species 6.[22,23] The most reactive nitroso compounds include those directly connected to an electron-withdrawing group, and nitroso compounds 4, 8, 11, and 12 are among the most reactive nitroso dienophiles used in HDA reactions.

2.2. Heteroatom-Nitroso Compounds

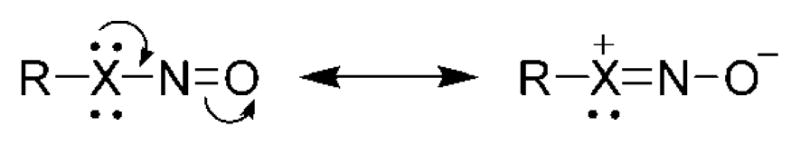

Compounds in which the nitroso group is directly connected to a heteroatom that possesses a free electron pair are much less reactive than C-nitroso compounds toward dienes because of resonance stabilization of the nitroso moiety (Figure 2). Consequently, HDA reactions of hetero-atom-nitroso compounds are studied much less compared to their C-nitroso counterparts.

Figure 2.

Resonance stabilization of X–N=O compounds.

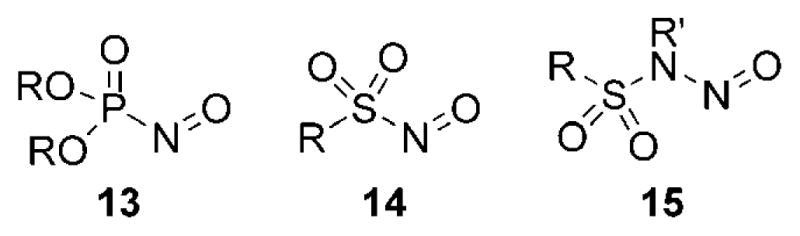

Deactivation of the dienophilic character of nitroso compounds through resonance stabilization can be overcome if no lone pairs of electrons are available for π donation. Some noteworthy examples that make use of this concept include P-nitrosophosphine oxides 13[26–28] and S-nitrososul-fonyl compounds 14 (Figure 3).[29] The N-nitroso compounds 15 were found to be unreactive toward dienes,[30] even though the presence of the sulfonyl group should diminish the effect of lone-pair stabilization.

Figure 3.

Examples of nitroso compounds with heteroatoms.

3. Nitrosocarbonyl Compounds

Nitrosocarbonyl compounds 11 and 12 are among the most reactive nitroso dienophiles. First proposed as transient intermediates in the oxidation of hydroxamic acids,[31] the only early evidence of the existence of acylnitroso 11 species were products resulting from nucleophilic attack at the acylnitroso carbonyl group[17] and [4+2] cycloaddition reactions.[32]

3.1. Preparation of Nitrosocarbonyl Compounds

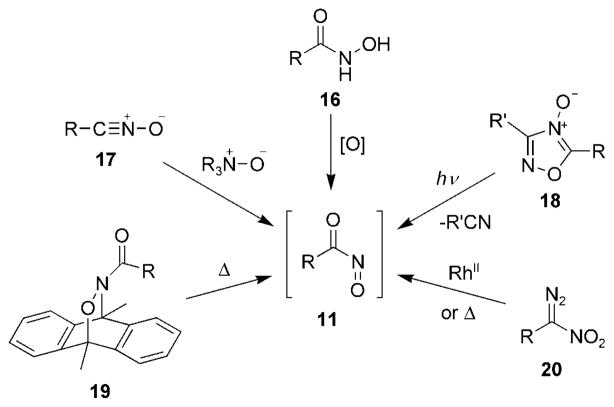

Since acylnitroso compounds 11 are extremely reactive species, they are prepared and used in situ in chemical reactions (Scheme 2). By far the most common method for preparing acylnitroso compounds 11 is through oxidation of the corresponding hydroxamic acid 16.[31] The generation of acylnitroso compounds 11 in this manner has been realized under a multitude of conditions, which include, but are not limited to, the use of periodate, Swern oxidation,[33] lead and silver oxide,[34] and Dess–Martin periodinane.[35] There are also a number of methods that generate acylnitroso compounds 11 from hydroxamic acids 16 through transition-metal-catalyzed oxidations in which peroxides are used as a stoichiometric oxidant.[36–41] A thorough study of metal catalysts that perform this transformation has been reported.[42]

Scheme 2.

Common synthetic routes to nitrosocarbonyl species.

Other methods commonly used to prepare acylnitroso species 11 include the oxidation of nitrile oxides 17,[43] cycloreversion from 9,10-dimethylanthracene adducts 19,[44] photochemical cleavage of 1,2,4-oxadiazole-4-oxides 18,[45] and rearrangement of nitrocarbenes generated from diazo compounds 20.[46]

3.2. Structure and Reactivity of Nitrosocarbonyl Compounds

Although acylnitroso compounds have been studied for well over 50 years, relatively little is known about their structure. Acylnitroso species were first detected spectroscopically in the gas phase in 1991 by neutralization-reionization mass spectrometry[47] and then in solution in 2003 by time-resolved infrared spectroscopy.[48] It is estimated that the lifetime of the acylnitroso species at infinite dilution in an organic solution is on the order of 1 ms.[48]

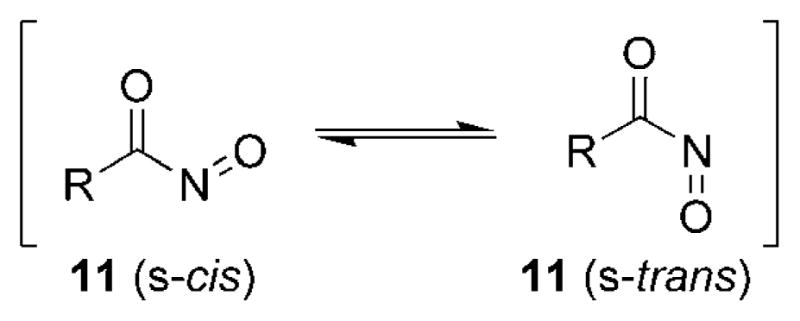

Acylnitroso compounds 11 can exist in either an s-cis or s-trans conformation along the carbonyl–nitrogen bond (Figure 4). It is evident from the data reported in the literature, the preference for a given acylnitroso species 11 to exist as either conformer must be calculated on a case-by-case basis. Additionally, the preference for either conformer is not necessarily minor, and the reported energy differences between the s-cis and s-trans conformers of various acylnitroso species have spanned from about 0–2 kcalmol−1 to nearly 15 kcalmol−1.[49–54]

Figure 4.

s-cis and s-trans Isomers of nitrosocarbonyl compounds.

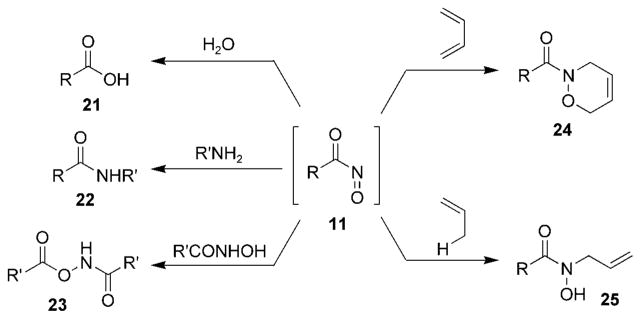

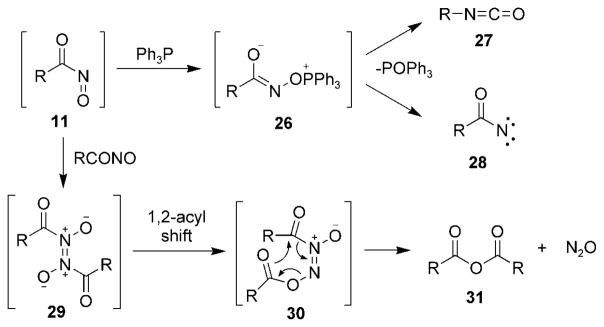

In addition to participating in HDA reactions with dienes to provide N-acyl-3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines 24 (R =acyl) and in ene reactions to provide N-allylhydroxamates 25, acylnitroso compounds 11 also undergo a number of other transformations (Scheme 3). The high stretching frequency of the carbonyl group of acylnitroso compounds 11 (1735 cm−1)[48] reflects their susceptibility to nucleophilic attack at the acylnitroso carbonyl group. The corresponding carboxylic acids 21, amides 22, and O-acylhydroxamates 23 are obtained in the presence of nucleophiles such as water, amines, and hydroxamic acids, respectively.[17]

Scheme 3.

Reactions of nitrosocarbonyl compounds.

One of the earliest reactions observed with acylnitroso compounds 11 (R =alkyl, aryl) was their tendency to be deoxygenated by phosphines to yield isocyanates 27 through phosphonium intermediate 26 (Scheme 4).[55] In contrast, nitrosoformate esters 11 (R =alkoxy) yield products arising from the generation of the acylnitrene species 28 because of the unfavorable migratory aptitude of the alkoxy substitutent from phosphonium intermediate 26.[25]

Scheme 4.

Other reactions of nitrosocarbonyl compounds.

Acylnitroso compounds 11 have also been known to generate symmetrical anhydrides 31 and nitrous oxide in the absence of other reactants. Presumably, this process proceeds through nitroso dimer 29, which undergoes a 1,2-acyl shift to give compound 30 followed by an intramolecular cyclization.[44]

4. Nitrosocarbonyl Hetero-Diels–Alder Reactions

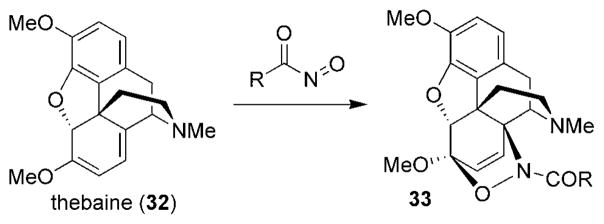

The most common use of nitroso compounds has involved their ability to participate in [4+2] cycloaddition reactions. The first nitroso HDA reactions using aryl- and alkylnitroso compounds were reported by Wichterle[56] and Arbuzov[57] in 1947 and 1948, respectively. One of the earliest examples of a HDA reaction using an acylnitroso compound was reported by Kirby and Sweeny in 1973, where acylnitroso compounds were generated in the presence of thebaine (32) to afford cycloadducts 33 selectively (Scheme 5).[31]

Scheme 5.

The cycloaddition reported by Kirby and Sweeny.[31]

The remarkable selectivity observed in acylnitroso HDA reactions provides access to 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines and ultimately 1,4-amino alcohols. This section will document efforts toward the study of the mechanism, selectivity, and asymmetric variants of the acylnitroso HDA reaction.

4.1. Mechanism of the Nitrosocarbonyl HDA Reaction

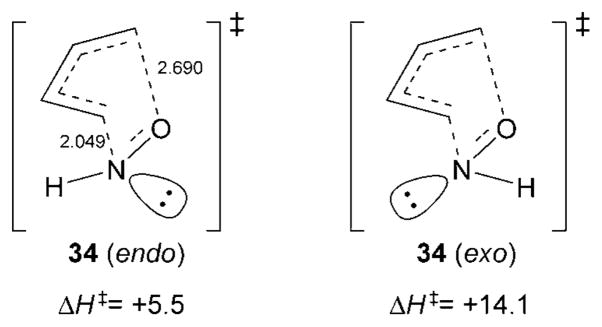

The mechanism of the acylnitroso HDA reaction has been studied computationally by Leach and Houk,[58,59] and was found to proceed in a concerted fashion through a highly asynchronous transition state. In the calculated transition state, the C–N bond is shorter than the C–O bond, whereas in the product, the situation is reversed. Additionally, the authors found from RB3LYP/6-31G*//RB3LYP/6-31G* theory that the endo transition state was preferred over the exo transition state by 8.6 kcalmol−1 (34, Figure 5).[59] The n–π repulsion exhibited by the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom, termed the “exo lone pair effect”,[60,61] is responsible for this strong preference for the placement of the nitrogen substituent in an endo position.

Figure 5.

Computed energies for transition states of the nitroso HDA reaction.

The combined preference for placement of the nitrogen substituent in an endo position with the shorter C–N bond in the transition state can explain the high regio- and stereoselectivities observed in acylnitroso HDA reactions.

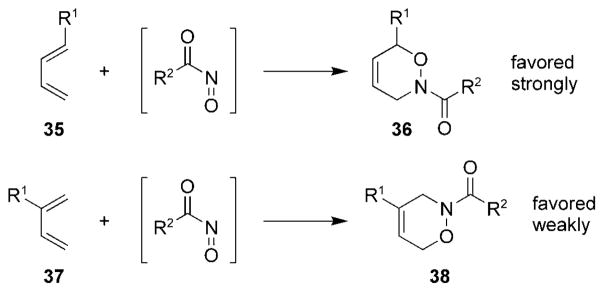

4.2. Regioselectivity in Nitrosocarbonyl HDA Reactions

The regioselectivity of intermolecular acylnitroso HDA reactions has been studied experimentally[2,62] as well as through the use of computational methods.[59] Most unsymmetrical dienes add to nitroso compounds regioselectively, as shown in Scheme 6. 1-Substituted 1,3-dienes 35 provide oxazines 36 with high selectivity, whereas 2-substituted 1,3-dienes 37 provide the oxazines 38 with moderate selectivity. The regioselectivity in nitroso HDA reactions can be rationalized on the basis of frontier MO theory, and dienes with substituents that are strongly electron donating or electron withdrawing provide cycloadducts with higher regioselectivity than dienes with substituents that are only weakly electron donating or electron withdrawing.[59] It should also be noted that, in most cases, solvent polarity has been shown to have little effect on the regioselectivity in intermolecular nitroso HDA reactions;[62] however, as will be described in Section 8.2, the opposite is true of intramolecular nitroso HDA reactions.

Scheme 6.

General selectivity observed for unsymmetrical dienes.

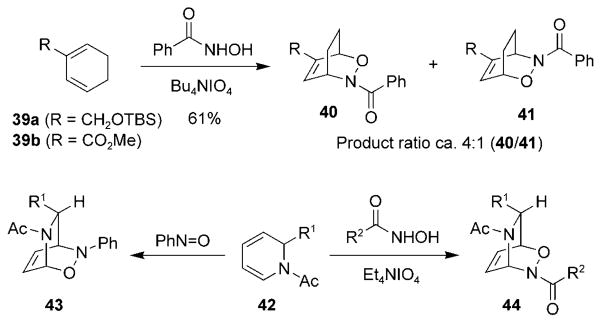

Similar trends for regioselectivity are observed for substituted cyclic dienes in acylnitroso HDA reactions (Scheme 7). The oxidization of benzohydroxamic acid in the presence of substituted cyclohexadienes 39a and 39b, led to cycloadducts 40 and 41 with moderate regioselectivity.[62]

Scheme 7.

Examples of regioselectivity in nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions. TBS =tert-butyldimethylsilyl.

In most cases, arylnitroso and acylnitroso species yield products with the same regioselectivity; however, in a few cases the selectivites are reversed. For example, opposite regioselectivities were observed when N-acyl-1,2-dihydropyridines 42 were treated with arylnitroso and acylnitroso compounds. Arylnitroso compounds afforded adducts 43,[63,64] while acylnitroso compounds (R2 =alkyl) resulted in cycloadducts 44.[64] The reason for this observed difference in regioselectivity has not been explained.

4.3. Stereoselectivity in Nitrosocarbonyl HDA Reactions

There are a number of reviews detailing the use of asymmetric nitroso HDA reactions in organic syntheses.[1,4–6,50] Methods for performing asymmetric nitroso HDA reactions include the use of chiral nitroso dienophiles, chiral dienes, and, with mixed success, the use of chiral catalysis. All three of these general approaches toward asymmetric nitroso HDA reactions will be described briefly in the following sections.

4.3.1. Chiral Dienophiles in Nitrosocarbonyl HDA Reactions

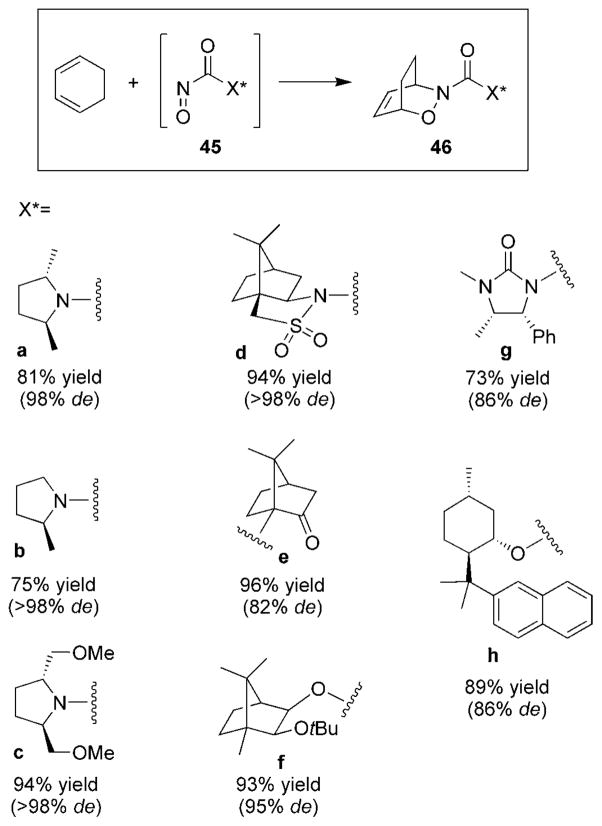

The use of chiral acylnitroso dienophiles, specifically as chiral auxiliaries, is the most common method for inducing chirality in acylnitroso HDA reactions. A variety of chiral acylnitroso species 45 that have been found to provide 1,3-cyclohexadiene adduct 46 with excellent diastereoselectivity have appeared in the literature (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Examples of chiral nitrosocarbonyl compounds.

All acylnitroso species 45 were prepared in situ by oxidation from the corresponding hydroxamic acid. Substituted pyrrolidines 45a–c offered cycloadducts 46 in high diastereomeric excess.[49] Additionally, a variety of camphor derivatives 45d–f have also been reported.[30,33,51] Other auxiliaries include imidazolidin-2-one 45g[52] and compound 45h,[65] derived from menthol.

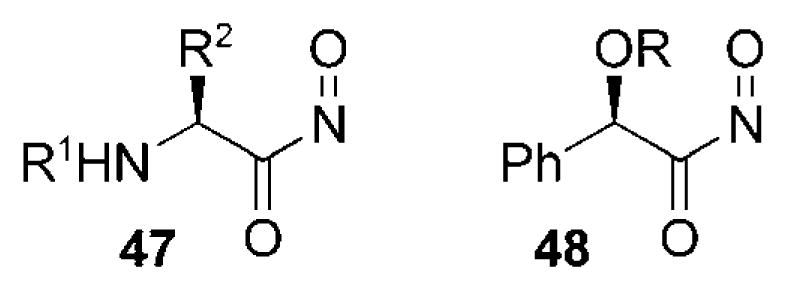

Chiral α-substituted acylnitroso compounds that undergo asymmetric HDA reactions have included nitroso species 47 derived from α-amino acids,[4,66,67] and nitroso species 48 derived from mandelic acid (Figure 7).[53,54,68–71] These auxiliaries benefit from their relatively simple preparation from readily available sources of chirality.

Figure 7.

Other chiral nitrosocarbonyl species.

4.3.2. Chiral Dienes in Nitrosocarbonyl HDA Reactions

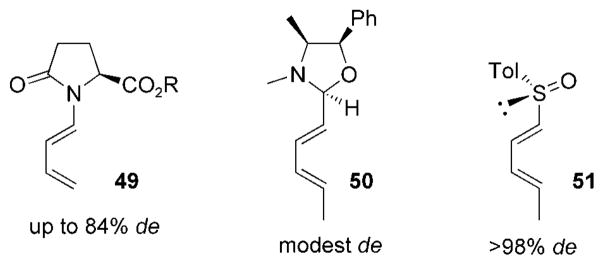

The use of both chiral cyclic and acyclic dienes in diastereoselective acylnitroso HDA reactions has been reported in the literature. In general, the use of chiral acyclic dienes yields cycloadducts in lower diastereomeric excess than does the use of chiral acylnitroso dienophiles. This is probably a result of the asynchronous transition state of the nitroso HDA reaction, where the nitrogen substituent is hypothesized to be closer to the diene than the oxygen lone pairs of electrons. This, in turn, places the chiral moiety of 1-substituted acyclic dienes spatially distant from the bulk of the incoming nitroso dienophile. Nevertheless, chiral acyclic dienes, such as chiral N-dienyllactams 49,[72,73] pseudoephedrine-derived oxazolidines 50,[74] and chiral 1-sulfinyl dienes 51 (Figure 8)[75,76] have been successfully used in asymmetric nitroso HDA reactions.

Figure 8.

Examples of chiral acylic dienes.

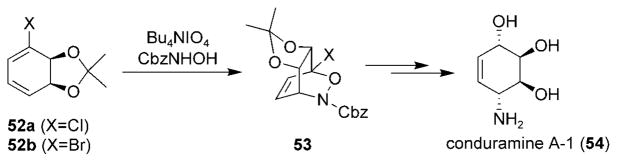

Compared to chiral acyclic dienes, chiral cyclic dienes often yield cycloadducts with excellent diastereoselectivity. Hudlicky and Olivo have reported the use of chiral dienes 52a and 52b, obtained by microbial oxidation of halobenzenes, in asymmetric nitroso HDA reactions (Scheme 8).[77] Cycloadducts 53 were obtained in high yields with complete diastereo- and regioselectivity. The conversion of cycloadducts 53 into conduramine A-1 (54) was also described.

Scheme 8.

Stereoselective nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction in the presence of a chiral diene. Cbz =benzyloxycarbonyl.

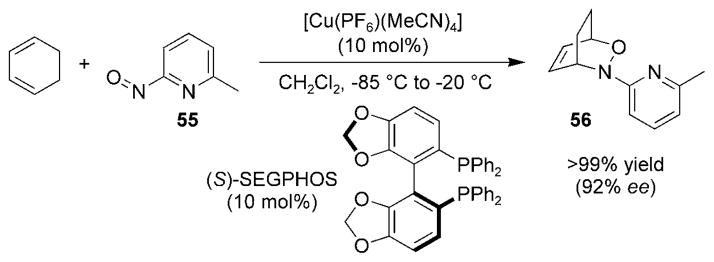

4.3.3. Catalytic Asymmetric Nitroso HDA Reactions

For many years, attempts at developing a catalytic asymmetric nitroso HDA reaction resulted in only extremely low ee values (ca. 15%).[78] It was not until 2004, when the Yamamoto research group published an asymmetric nitroso HDA reaction with pyridylnitroso species 55, that an effective catalytic asymmetric nitroso HDA reaction was realized (Scheme 9).[79] This ground-breaking discovery is very useful for the synthesis of enantiomerically pure oxazines 56; however, a similar method for the nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction is still lacking.

Scheme 9.

Catalytic asymmetric pyridylnitroso cycloaddition.

The difficulties faced in the development of a catalytic asymmetric method for the nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction have included an extremely facile background reaction and the susceptibility of nitrosocarbonyl species to dimerize. These problems plagued the study of aryl- and heteroarylnitroso species for some time before the discovery of the Yamamoto research group;[78] however, nitrosocarbonyl compounds are more reactive than aryl- or heteroarylnitroso species, and react as rapidly or more rapidly without catalysts than when bound to a Lewis acid.[36,38] A better understanding of the metal coordination chemistry of nitrosocarbonyl species will be essential for the development of a catalytic asymmetric nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction.

5. Nitrosocarbonyl HDA Reactions on a Solid Phase

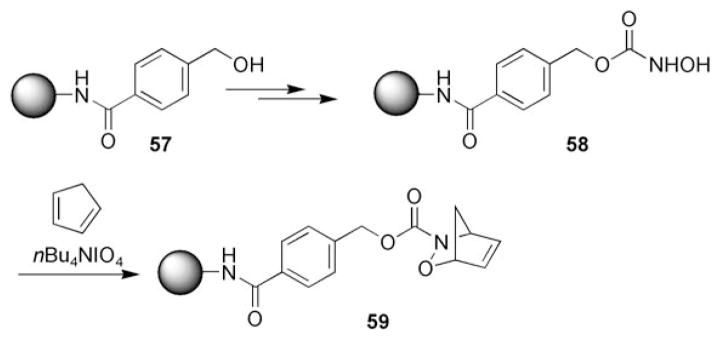

Although nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions have been widely used in organic synthesis in solution, there have only been a few accounts of performing nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions on a solid support. One example reported by Krchnak et al.[80–82] utilized Wang resin supported hydroxamic acids 58 derived from alcohols 57 (Scheme 10). The hydroxamic acids 58 were oxidized using tetrabutylammonium periodate in the presence of dienes to yield cycloadducts 59.

Scheme 10.

Nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction on a solid phase.

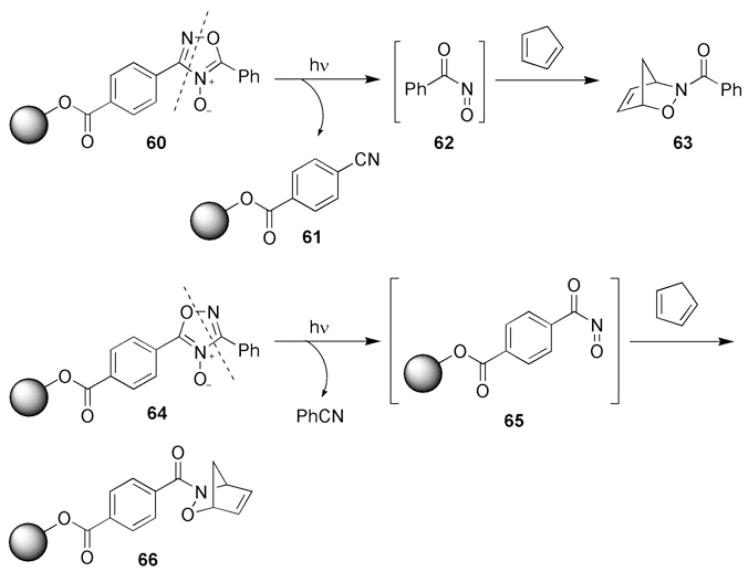

Other solid-supported nitroso HDA reactions reported by Quadrelli and co-workers include the generation of acylnitroso compounds from solid-supported nitrile oxides[83] and the photochemical generation of acylnitroso compounds from solid-supported 1,2,4-oxadiazole-4-oxides 60 and 64 (Scheme 11).[84] Upon irradiation, compounds 60 generated the solid-supported nitrile 61 and the acylnitroso compound 62, which was trapped in situ with cyclopentadiene to afford cycloadduct 63. Irradiation of 1,2,4-oxadiazole-4-oxide 64 provided benzonitrile and solid-supported acylnitroso compound 65, which was subsequently trapped by dienes to yield cycloadduct 66.

Scheme 11.

Another nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction on a solid phase.

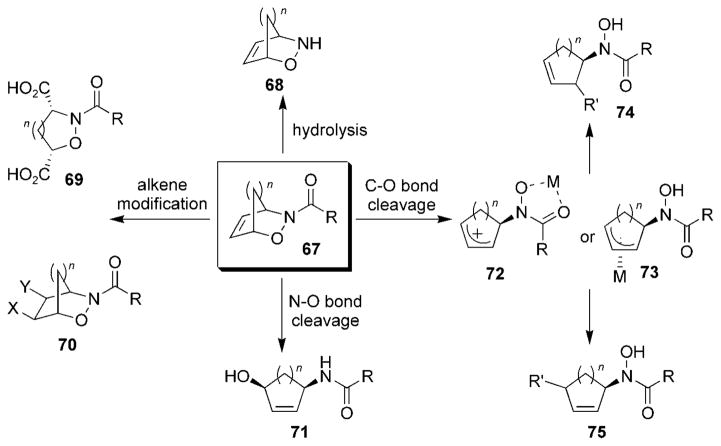

6. Chemistry of 3,6-Dihydro-1,2-oxazines

Most of the utility of the acylnitroso HDA reaction in organic syntheses stems from the rich chemistry of the resulting cycloaddition products. The rapid construction of a wide variety of functional groups in one molecule allows access to a number of molecular scaffolds from simple bicyclic cycloadducts 67 (Scheme 12). The structural modification of cycloadducts 67 can be divided into one of four main areas: cleavage of the N–acyl bond to yield oxazines 68, cleavage of the N–O bond to yield amino alcohols 71, cleavage of the C–O bond to yield compounds 72–75, and alkene modification to afford compounds 69 and/or 70. Additionally, compounds such as oxazines 67 have demonstrated the ability to undergo a number of rearrangements and other chemical reactions.

Scheme 12.

Modification of bicyclic 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines.

The carbonyl group of cycloadducts 67 is susceptible to hydrolysis under relatively mild conditions (R =alkyl or aryl).[85] This provides the basis for removing many of the chiral auxiliaries described in Section 4.3.1. The following section details various transformations of cycloadducts 67 commonly utilized in synthetic organic applications. Although most of the methodology has been developed using bicyclic oxazines 67, much of the chemistry presented here is also applicable to monocyclic 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines.

6.1. Alternate Routes to 3,6-Dihydro-1,2-oxazines

Although the nitroso HDA reaction is an excellent method for preparing 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines, alternative methods for preparing these heterocyclic systems exist and have been reviewed.[86,87] Methods of preparing monocyclic 1,2-oxazines have included using alkene[88] and enyne[89,90] ring-closing metathesis reactions, the addition of nitrones to methoxyallenes[91] and activated cyclopropanes,[92,93] and the use of nitroso aldol reactions.[94]

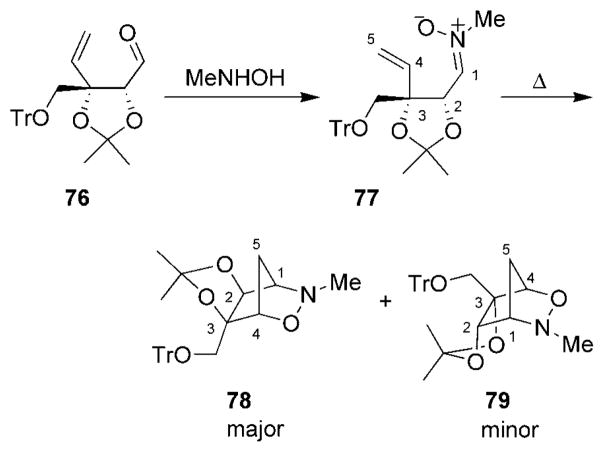

An example of an alternative synthesis of bicyclic 1,2-oxazine systems involved an intramolecular nitrone [3+2] cycloaddition (Scheme 13).[95] Aldehyde 76, derived from L-arabinose, was converted into nitrone 77, which cyclized selectively to yield oxazines 78 and 79.

Scheme 13.

[3+2] Cycloaddition for the synthesis of 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazines. Tr =triphenylmethyl.

6.2. N–O Bond Cleavage

Reductive cleavage of the N–O bond is one of the most widely utilized methods for derivatizing 1,2-oxazines. Common reagents that facilitate cleavage of the N–O bond include molybdenumhexacarbonyl ([Mo(CO)6]),[96,97] zinc in acetic acid, catalytic hydrogenation, samarium diiodide,[98,99] and titanocene(III) chloride.[100] Other methods for reduction of the N–O bond include the use of photochemical,[101] enzymatic,[102] and other chemical[103] processes.

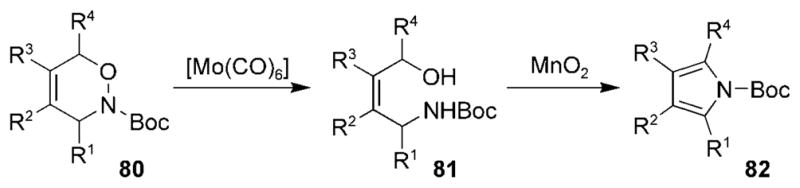

Reductive cleavage of the N–O bonds of monocyclic 1,2-oxazines 80 yielded 1,4-amino alcohols 81, which have been cyclized using manganese dioxide to provide access to pyrroles 82 (Scheme 14).[104]

Scheme 14.

Pyrrole synthesis by reductive cleavage of a N–O bond. Boc =tert-butoxycarbonyl.

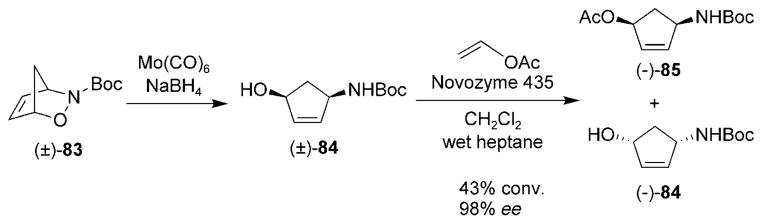

Treatment of racemic cycloadduct (±)-83 with molybde-numhexacarbonyl yielded the aminocyclopentenol (±)-84 (Scheme 15). The Miller research group has developed a kinetic enzymatic resolution method that yielded enantiomerically pure acetate (−)-85 and aminocyclopentenol (−)-84 by using an immobilized lipase from Candida antarctica.[105] Acetate (−)-85 has been an important intermediate in the synthesis of 5′-norcarbocyclic nucleosides, which will be covered in Section 7.1.

Scheme 15.

Enzymatic resolution of a racemic alcohol.

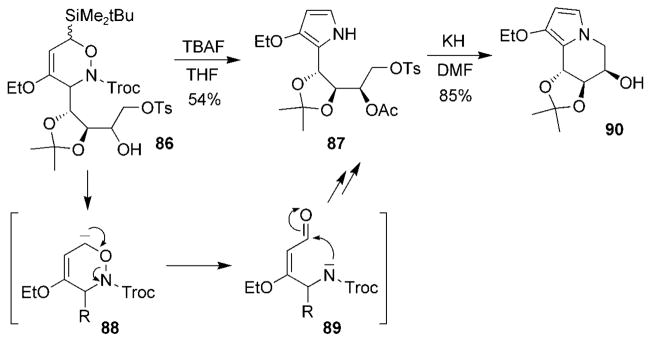

Other methods for the reductive cleavage of the N–O bond have included eliminative ring-opening reactions similar to that reported by Kefalas and Grierson (Scheme 16).[106] 1,2-Oxazine 86 was treated with tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) to provide pyrrole 87. The anion intermediate 88 generated by treatment with fluoride yielded the aldehyde intermediate 89, which subsequently underwent dehydrative cyclization to afford pyrrole 87. Intramolecular cyclization to pyrrolo-castanospermine 90 was effected using KH in DMF. This reaction sequence was similar to that reported for the base-catalyzed decomposition of dialkyl peroxides (the Kornblum–DeLaMare rearrangement),[107] and has also been reported for other monocyclic oxazine systems.[108]

Scheme 16.

An alternative method for cleavage of the N–O bond. Troc =trichloroethoxycarbonyl, Ts =toluene-4-sulfonyl.

6.3. C–O Bond Cleavage

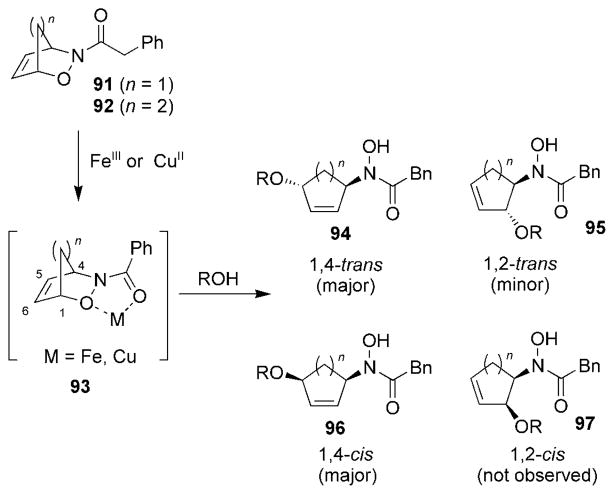

The Miller research group reported that Lewis acids could mediate C–O bond cleavage of cycloadducts 91 and 92 in the presence of alcoholic solvents to afford hydroxamates 94–96 (Scheme 17).[109,110] Presumably, this transformation proceeded by coordination of the Lewis acid to the hydroxamate portion of the oxazine system through a structure similar to complex 93. The reaction was found to be moderately selective for 1,4-trans-hydroxamate 94 over 1,2-cis-hydroxamate 96. The formation of 1,2-cis-hydroxamate 97 was not observed.

Scheme 17.

Lewis acid mediated cleavage of a C–O bond. Bn =benzyl.

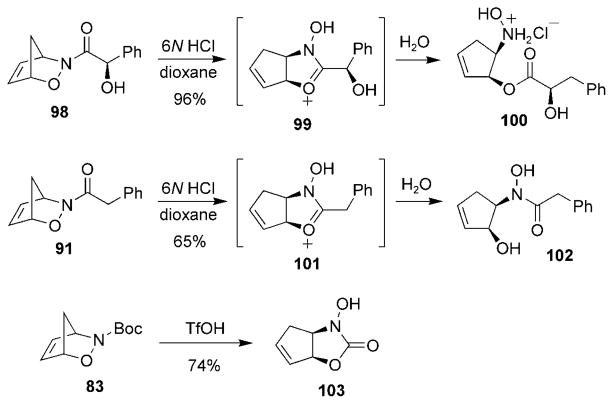

The C–O bond has also been cleaved in the presence of Brønsted acids to yield products arising from intramolecular cyclizations (Scheme 18). For example, Procter and co-workers reported that treatment of cycloadduct 98, derived from mandelic acid, with aqueous HCl in dioxane afforded hydroxylamine 100.[111,112] Interestingly, hydroxamate 102 was obtained when cycloadduct 91 was treated under the same conditions.[109] It would appear that both reactions proceeded through the bicyclic intermediates 99 and 101, respectively; however, no explanation was given for the different products arising from hydrolysis. Recently, the treatment of cycloadduct 83 with Brønsted acids yielded the bicyclic hydroxamate 103.[113]

Scheme 18.

Brønsted acid mediated cleavage of a C–O bond. TfOH = trifluoromethanesulfonic acid.

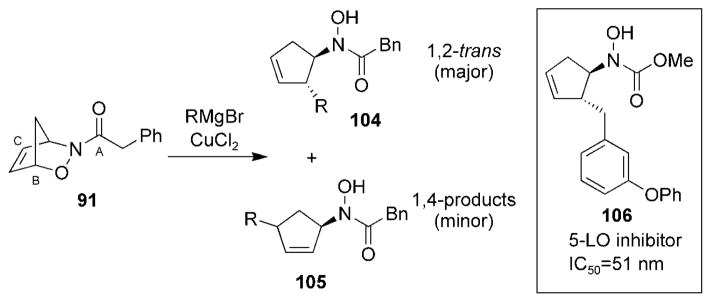

Treatment of cycloadduct 91 with Grignard reagents in the presence of CuII resulted in the selective formation of hydroxamates 104 arising from attack at the “C” position and to minor amounts of hydroxamates 105 arising from attack at the “B” position (Scheme 19).[114] Similar reactivity was observed when bicyclic cycloadducts 67 were treated with dialkylzinc reagents in the presence of copper catalysts.[115,116] Even though attack at the carbonyl group was expected on the basis of studies by Keck et al.,[85] no products arising from attack at position “A” were observed. Again, this probably illustrates the weakening of the C–O bond that arises in metal-coordinated species such as complex 93. This method was applied in the synthesis of hydroxamate 106, a potent 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor.[114]

Scheme 19.

Cleavage of a C–O bond with Grignard reagents.

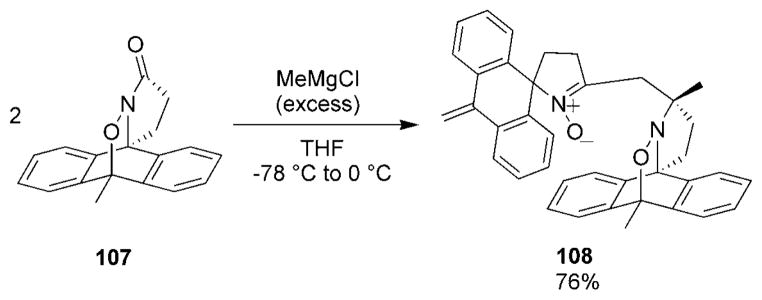

Other unexpected reactions have been reported when acylnitroso HDA cycloadducts were treated with Grignard reagents. Treatment of 9,10-dimethylanthracene adduct 107 with excess MeMgCl in THF led to the unusual dimeric nitrone compound 108 in 76% yield (Scheme 20).[117] The authors proposed a possible mechanistic explanation for this result; however, the details concerning the formation of compound 108 are still not clear.

Scheme 20.

An unusual reaction with a Grignard reagent.

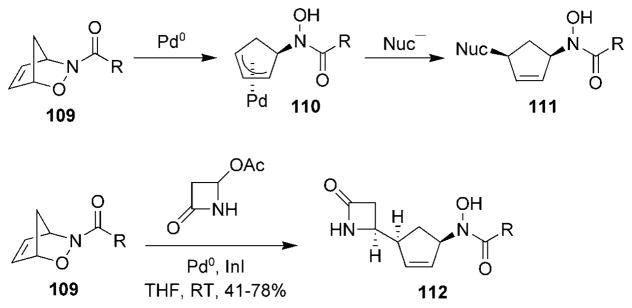

Treatment of cycloadducts 108 with Pd0 yielded π-allyl species 110, which were trapped with nucleophiles and provided 1,4-cis-cyclopentenes 111 selectively (Scheme 21).[109,118] π-Allyl species 110 can be reductively transmetalated using InI to form allylic indium(III) species, which are subsequently trapped with reactive aldehydes, ketones, and other electrophiles, such as Eschenmoser’s salt.[119,120] Recently, the in situ prepared allylindium(III) species generated from cycloadduct 109 was trapped with 4-acetoxy-2-azetidinone to provide compound 112 with high regio- and stereospecificity.[120]

Scheme 21.

Pd/In-mediated cleavage of a C–O bond.

6.4. Cleavage and Modification of the Alkene Function

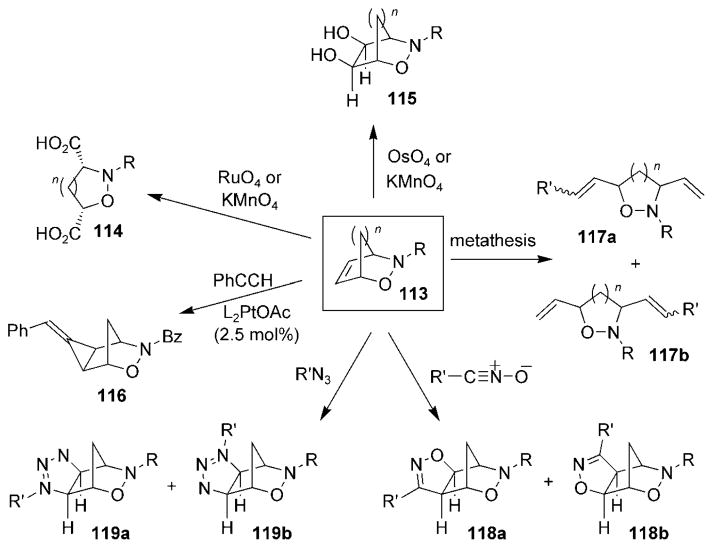

Compared to other functionality in bicyclic oxazines 113, relatively little effort has been concentrated on modifying the alkene portion of the 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazine system. Accordingly, the strained nature of the 2-oxa-3-aza-bicyclo-[2.2.1]hept-5-ene system has been under-utilized for its potential to promote the selective functionalization of the alkene system. Only a handful of transformations have been made to the alkene moiety in bicyclic oxazines 113 (Scheme 22). The oxidative cleavage of cycloadducts 113 yielded diacid compounds 114. Other studies have shown the alkene function of bicylic oxazines 113 to be suitable for ring-opening cross-metathesis reactions, thereby resulting in compounds 117a and 117b,[121,122] while alkylidenecyclopropanation of oxazine 113 yielded compound 116.[123]

Scheme 22.

Examples of alkene modification of bicyclic cycloadducts. Bz =benzoyl.

Additions to the alkene function of bicylic oxazine 113 (n =1) have often proceeded with high facial selectivity, but not with high regioselectivity. Consequently, dihydroxylation of cycloadducts 113 yielded diols 115,[124–126] and alkylidene-cyclopropanation yielded compound 116[123] with excellent selectivity. Dipolar cycloaddition reactions of oxazines 113 proceed with high facial selectivity, but with poor regioselectivity. Consequently, treatment of cycloadducts 113 with nitrile oxides[127,128] and organic azides[129] afforded dihydro-isoxazoles 118a,b and triazolines 119a,b, respectively, as regioisomeric mixtures.

6.5. Other Chemical Transformations and Rearrangements

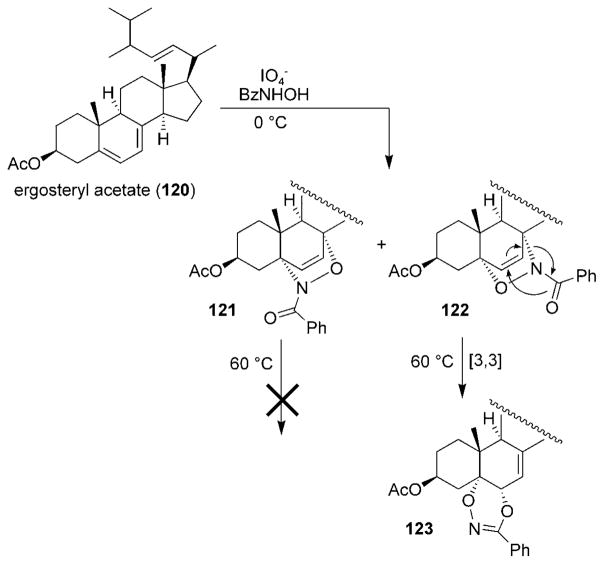

In addition to the reactions outlined above, nitrosocarbonyl HDA cycloadducts have participated in a number of other unusual and mechanistically interesting transformations.[17,130] Kirby and Mackinnon reported that treatment of ergosteryl acetate (120) with acylnitroso compounds in refluxing benzene afforded cycloadduct 121 along with the unusual dihydrodioxazine 123 (Scheme 23).[131] When the reaction was repeated at 0°C, the regioisomeric cycloadducts 121 and 122 were obtained; however, heating the mixture to reflux resulted in cycloadduct 122 being transformed into the dioxazine compound 123 through a [3,3] sigmatropic rearrangement. Oxazine 121 did not undergo the rearrangement, which was explained by steric crowding of the dioxazine product.

Scheme 23.

[3,3] Rearrangment of an ergosteryl cycloadduct.

7. Synthetic Applications of Intermolecular Nitroso-carbonyl HDA Reactions

The utility of the intermolecular nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction in organic syntheses is reflected by the wide variety of molecules that are accessible. The following section will outline various classes of molecules that have been synthesized by using nitrosocarbonyl HDA methodology.

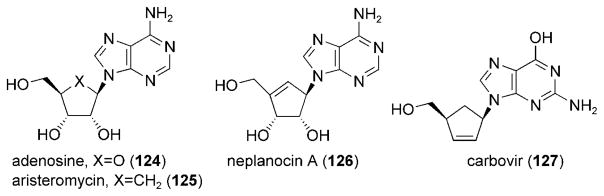

7.1. Carbocyclic Nucleosides

Carbocyclic nucleosides, in which the furanose oxygen atom of the nucleoside is replaced by a methylene unit, have received attention for their use as antiviral agents.[132–136] Aristeromycin (125) is the direct carbocyclic nucleoside analogue of adenosine (124) and has demonstrated potent antiviral properties linked to the inhibition of AdoHcy hydrolase (Figure 9).[137] The synthesis and study of carbocyclic nucleosides has been an important area of therapeutic research, and many methods have been developed that allow access to this class of molecules.

Figure 9.

Representative carbocylic nucleosides.

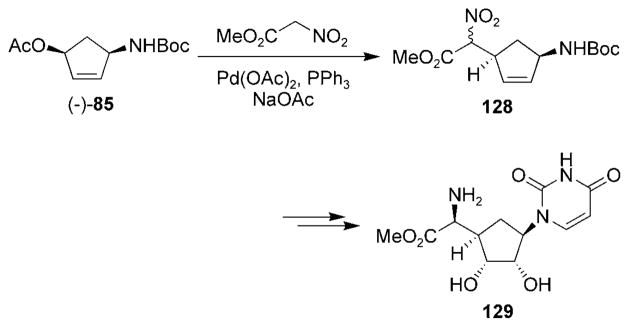

The Miller research group has published a number of reports regarding the use of nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions to construct carbocyclic nucleoside analogues.[66,138–143] Enantiomerically pure acetate (−)-85,[105] obtained from the kinetic enzymatic resolution process described in Section 6.2, was used to synthesize carbocyclic uracil polyoxin C (129) and its epimer through the intermediate 128 (Scheme 24).[140,144] The opposite enantiomer of acetate (−)-85 was used to synthesize the carbocyclic fragment of nucleoside Q.[145]

Scheme 24.

Synthesis of the carbocyclic uracil polyoxcin C.

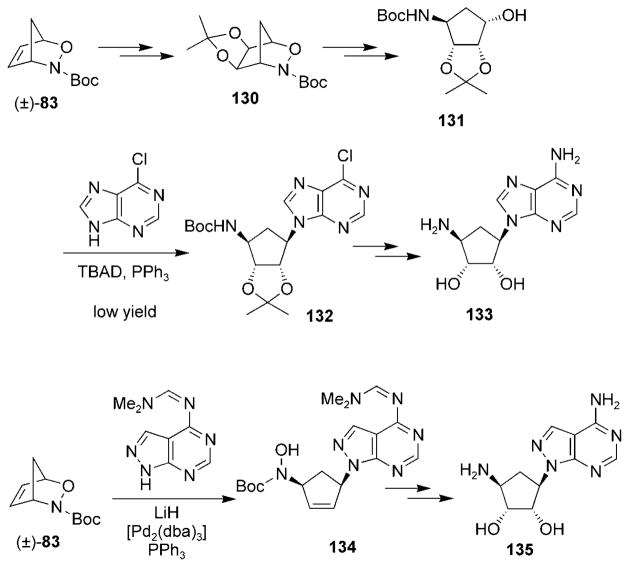

Cowart et al. have also published a method for synthesizing azacarbocyclic nucleoside analogues, such as compounds 133 and 135, from cycloadduct 83 (Scheme 25).[126] Reduction of the N–O bond of acetonide 130 followed by inversion of the alcohol group through an oxidation/reduction sequence yielded alcohol 131. The nucleoside base was installed under Mitsunobu conditions and yielded compound 132, which was ultimately transformed into analogue 133. This method suffered from low yields for the Mitsunobu reaction, so an alternative strategy was employed that made use of palladium-π-allyl chemistry to install the base directly from cycloadduct 83 and yielded hydroxamate 134. Reduction of the hydroxamate followed by dihydroxylation and deprotection provided an efficient route to analogue 135.

Scheme 25.

Synthesis of azacarbocyclic nucleoside analogues., dba = trans,trans-dibenzylideneacetone, TBAD =di-tert-butyl azodicarboxylate.

7.2. Azasugars

The nitroso HDA reaction allows the construction of 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazine rings that possess the required substitution pattern for the synthesis of many azasugars. The use of the nitroso HDA reaction for the synthesis of azasugars has been reviewed,[3,50] and allows access to both pyrrolidine and piperidine analogues of sugars.

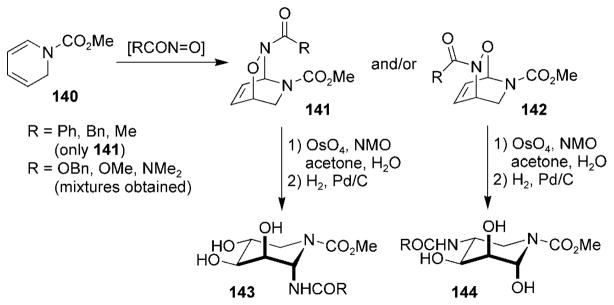

Acyclic dienes 136a[72,146–148] and 136b[75] have been used for the synthesis of pyrrolidine-based sugar derivatives (Scheme 26). The cycloadducts 137 have been obtained in high yield and diastereoselectivity. Dihydroxylation afforded diol 138 with excellent facial selectivity, and reduction of the N–O bond followed by intramolecular condensation provided access to pyrrolidines 139.

Scheme 26.

Synthetic route to pyrrolidines. NMO =4-methylmorpholine N-oxide, Tol =tolyl.

Piperidine-based sugar derivatives have been synthesized by utilizing an acylnitroso HDA reaction with 1,2-dihydro-pyridines 140 (Scheme 27).[3] While nitrosoformate esters yielded mixtures of cycloadducts 141 and 142, the use of acylnitroso species derived from carboxylic acids yielded cycloadduct 141 exclusively. Facially selective dihydroxylation followed by catalytic hydrogenation yielded the azasugar derivatives 143 and 144.

Scheme 27.

Route to aza sugars from 1,2-dihydropyridines.

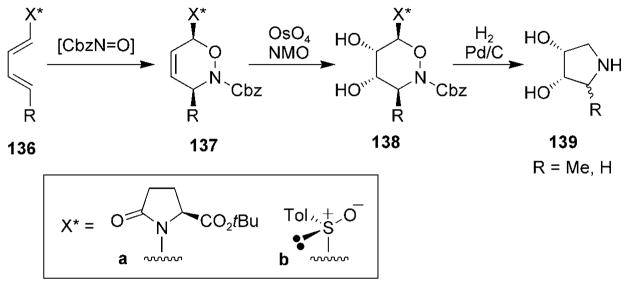

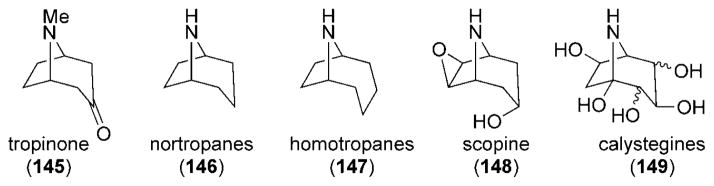

7.3. Tropane Alkaloids and Related Structures

Ever since the first landmark synthesis of tropinone (145) by Robinson in 1917,[149] the tropane alkaloids have continued to elicit the interest of synthetic organic chemists (Figure 10). This substance class includes nortropane (146), homotropane (147), scopine (148), and polyhydroxylated nortropanes such as calystegines (149).

Figure 10.

Structures of the tropane alkaloid family.

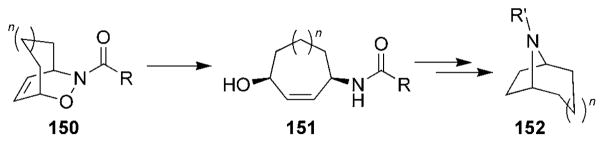

A number of nitrosocarbonyl HDA approaches to the tropane alkaloids have been reported, and all follow the same general scheme first outlined by Kibayashi and co-workers (Scheme 28):[150] Reductive cleavage of the N–O bond of cycloadducts 150 provided the amino alcohols 151. An intramolecular cyclization yielded the aza-bridged tropane system 152.

Scheme 28.

General synthetic route to tropane alkaloids.

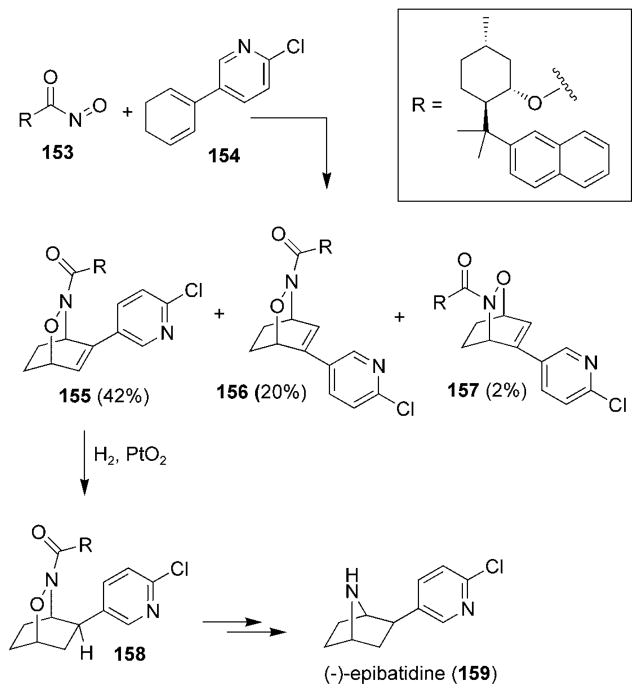

This general approach to tropanes has been extended to the enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-epibatidine (159) (Scheme 29).[65,151] Chiral nitrosoformate ester 153 was generated in the presence of diene 154 and yielded the three cycloadducts 155–157 with moderate selectivity. Cycloadduct 155 was used to complete the synthesis of (−)-epibatidine (159) via intermediate 158.

Scheme 29.

Total synthesis of (−)-epibatidine.

Other research groups have utilized similar approaches toward the synthesis of members of the tropane family such as nortropane (146),[152] homotropane (147),[153–155] scopine (148) and pseudoscopine,[156] and polyhydroxylated nortropanes 149.[157,158]

7.4. Amaryllidacea Alkaloids and Related Structures

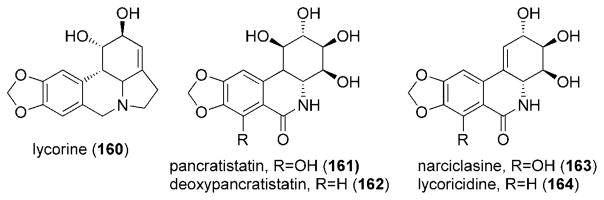

Alkaloids from plants in the Amaryllidacea family have been used in the treatment of cancer.[159] Members of this family of alkaloids include lycorine (160), pancratistatin (161), deoxypancratistatin (162), narciclasine (163), and lycoricidine (164; Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Structures of amaryllidacea alkaloids.

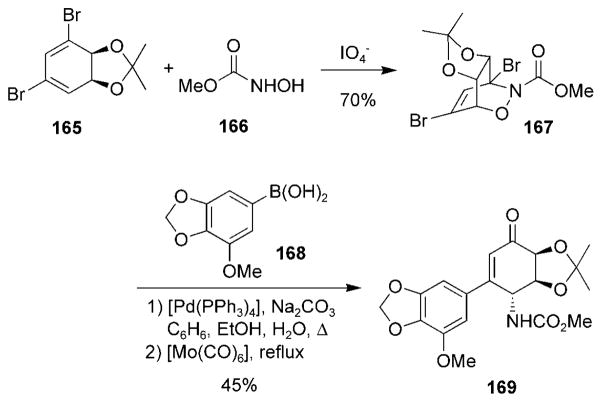

Nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions with substituted 1,3-cyclohexadienes have been used for the synthesis of the amaryllidacea alkaloids. The Hudlicky research group has published synthetic routes to narciclasine (163).[77,160,161] Nitrosoformic acid (166) was oxidized in the presence of the chiral diene 165 and yielded cycloadduct 167 (Scheme 30).[160] A one-pot Suzuki–Miyaura reaction followed by reduction of the N–O bond yielded the key intermediate 169, which was further elaborated to furnish narciclasine (163). Other routes to the amaryllidacea alkaloids and their core structure have been reported that utilize similar nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions.[33,161–165]

Scheme 30.

Synthetic route to narciclasine.

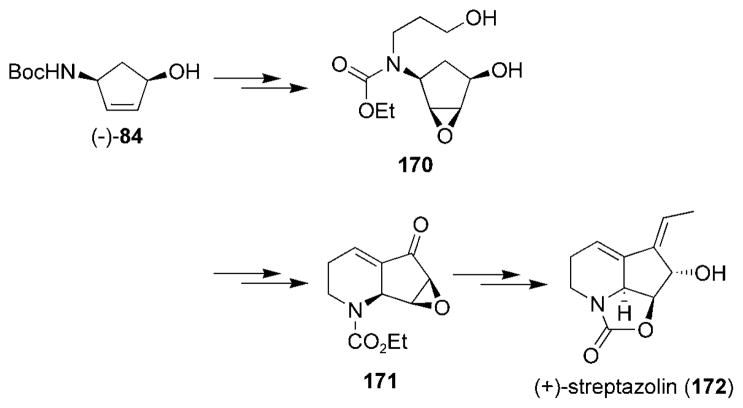

The total synthesis of the related fused polycyclic piperidine-containing alkaloid (+)-streptazolin (172) has also been reported by the Miller research group (Scheme 31).[166,167] The chiral cyclopentenol (−)-84 was converted into intermediate 170, which underwent an intra-molecular aldol condensation to furnish compound 171. Selective installment of the Z alkene was realized by using a silicon-tethered ring-closing metathesis strategy[167] and ultimately provided (+)-streptazolin (172).

Scheme 31.

Synthetic route to (+)-streptazolin.

7.5. Amino Acid Analogues and Related Structures

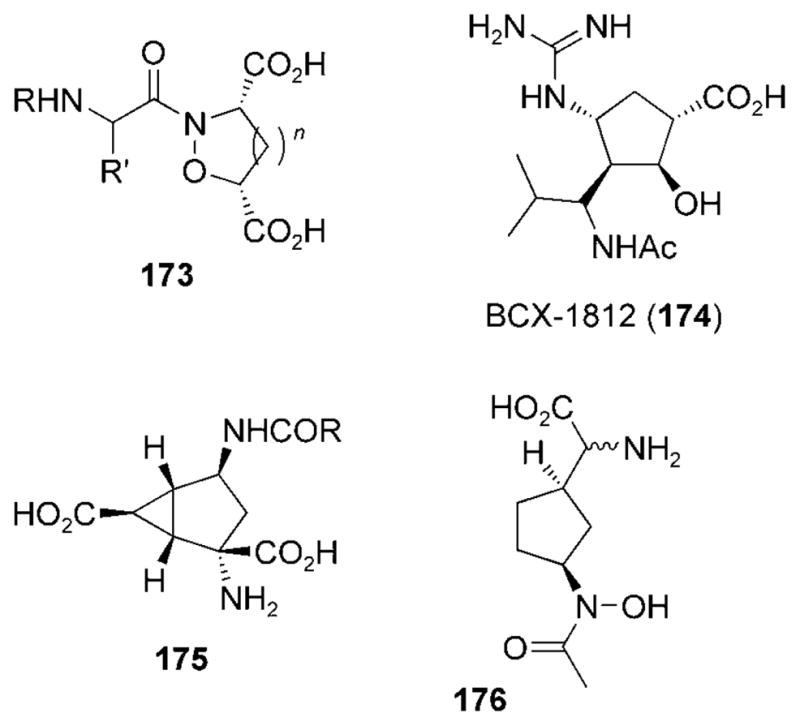

The nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction has provided access to a number of novel amino acid analogues and other biologically important molecules. The Miller research group has reported the synthesis of a variety of therapeutically relevant molecules. A number of amino acid analogues have been synthesized that are structurally similar to antibacterial diacid compounds 173[168] by the oxidative cleavage of nitrosocarbonyl HDA cycloadducts (Figure 12).[68,169–173] Other syntheses reported by Miller and co-workers have included the preparation of biologically active agents such as meso-DAP analogues,[174] BCX-1812 (174), LY354740 analogues 175, 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors 106,[114] phosphodiesterase inhibitors,[175–177] and the conformationally restricted substrate analogue of siderophore biosynthesis 176.[178]

Figure 12.

Representative amino acid derivatives and related structures.

7.6. Natural Product Derivatization

Ever since Kirby and Sweeny reported acylnitroso HDA reactions with thebaine,[31] the acylnitroso HDA reaction has been used as a method for synthesizing natural product derivatives. The benefits of using nitroso HDA reactions for this purpose include the often exquisite stereo- and regioselectivity of the cycloaddition as well as the rich chemistry of their products.

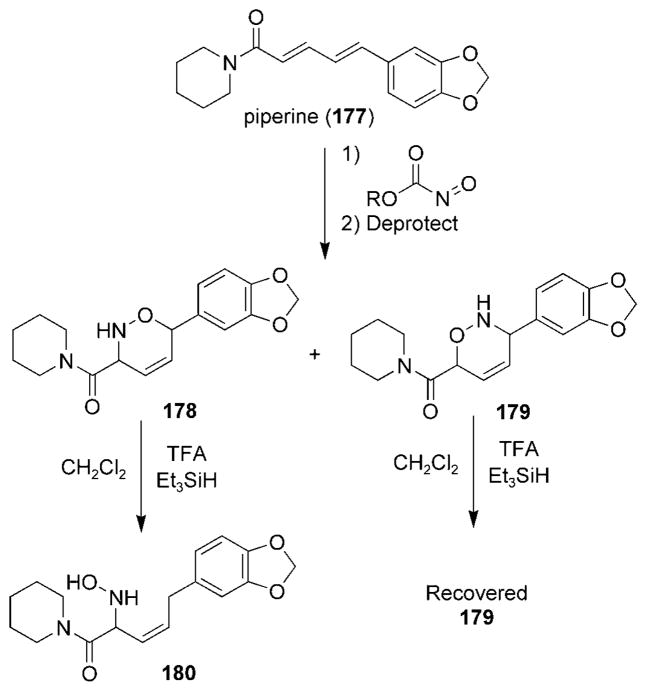

The nitroso HDA reaction has been used in a number of studies to provide access to steroids as well as novel analogues and derivatives.[25,131,179–181] The Miller research group has recently disclosed a strategy that exclusively utilizes nitroso cycloadditions to prepare analogues of natural products from a variety of molecular classes.[182] Piperine (177), a major component naturally found in peppers, was treated with polymer-supported nitrosocarbonyl species to produce, after deprotection, the two cycloadducts 178 and 179 (Scheme 32).[183] The authors were surprised to find that treatment of compound 178 with TFA and triethylsilane as a cation scavenger produced hydroxylamine 180. Under the same conditions, the cycloadduct 179 was recovered from the reaction unchanged.

Scheme 32.

A nitroso-Diels–Alder reaction with piperine (177). TFA = trifluoroacetic acid.

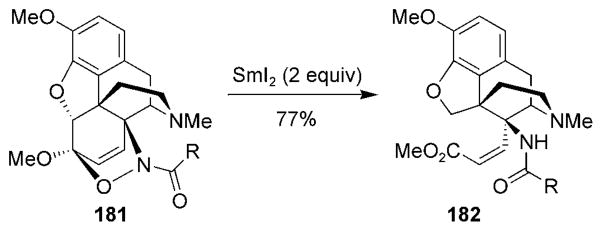

Thebaine has provided an interesting look into how structurally novel derivatives of natural products can be prepared in a few steps by using the chemistry of nitroso HDA cycloadducts. Gourlay and Kirby have reported a number of unusual reactions that use acylnitroso cycloadducts of the-baine.[17,184] In a recent example, Sheldrake and Soissons have reported the selective opening of the thebaine skeleton from cycloadducts 181 by using samarium diiodide (Scheme 33).[185] Similar to other reactions of acylnitroso HDA cycloadducts,[186] samarium diiodide facilitated cleavage of the N–O and C–C bonds in one pot and provided the novel derivative 182.

Scheme 33.

Thebaine analogues from an unexpected ring cleavage.

8. Synthetic Applications of Intramolecular Nitroso-carbonyl HDA Reactions

Intramolecular nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions have been used in the synthesis of natural products, alkaloids, and other biologically important molecules. Although intermolecular nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions are often regioselective, tethering the nitrosocarbonyl group to the reacting diene imparts regiospecificity and additional diastereoselectivity. This section will survey the use of intramolecular nitro-socarbonyl HDA reactions in the synthesis of a variety of alkaloid classes and will again emphasize the utility of the nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction as a method to construct complex structural systems.

8.1. Monocyclic Alkaloids

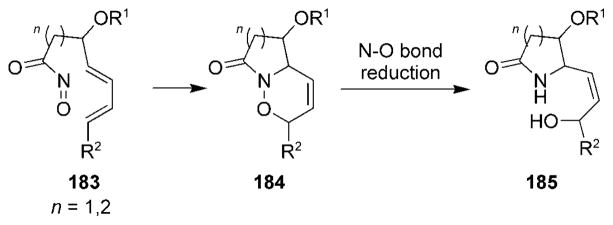

The simplest alkaloids that have been synthesized by utilizing intramolecular nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions are monocyclic alkaloids. The synthesis of compounds 185 from acylnitroso species 183 represents a general method that often closely resembles the initial steps in the synthesis of monocyclic as well as polycyclic alkaloid systems (Scheme 34). Preliminary studies in this area by Keck[187] as well as by Kibayashi and co-workers[188–190] provided the necessary methodology required for more elaborate structures.

Scheme 34.

General route to monocyclic alkaloids.

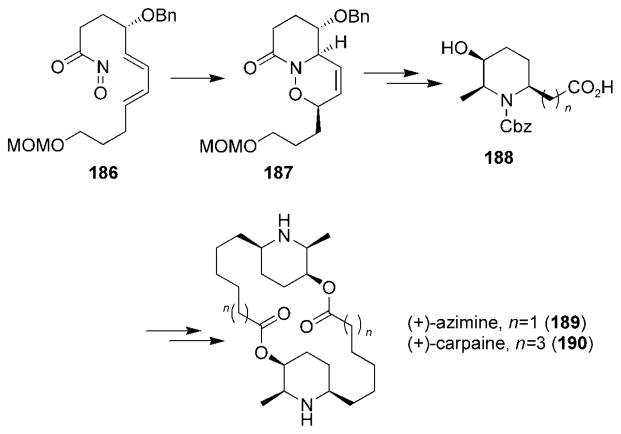

Recently, Kibayashi and co-workers published the enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-azimine (189) and (+)-carpaine (190), which highlighted the use of the intramolecular acylnitroso HDA reaction (Scheme 35).[191] Acylnitroso compound 186 underwent a spontaneous, stereoselective HDA reaction and formed oxazine 187, which was transformed, over a number of synthetic steps, into the key monomeric intermediate 188. Dimerization of compound 188 through the formation of the two ester bonds yielded the aforementioned natural products 189 and 190.

Scheme 35.

Synthesis of (+)-azimine and (+)-carpaine.

8.2. Decahydroquinoline Alkaloids

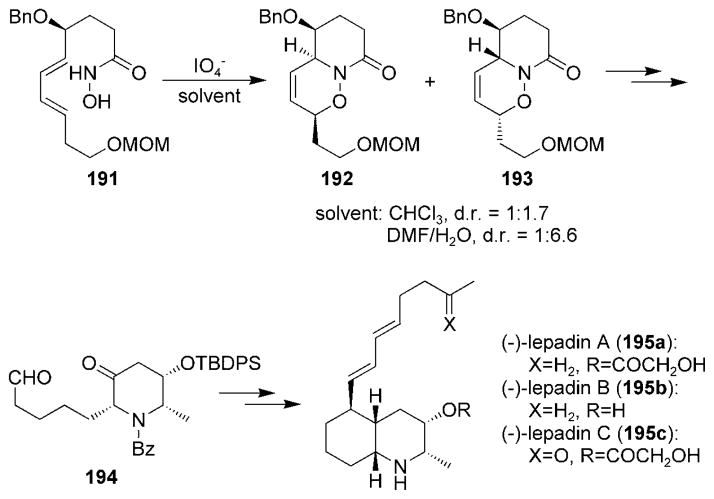

Decahydroquinoline alkaloids have been synthesized by using similar methodology as for monocyclic alkaloids. The synthesis of (−)-lepadins A (195a), B (195b), and C (195c) was reported in 2001 (Scheme 36).[192,193] The synthesis of the lepadin family also illustrated an important difference between the intra- and intermolecular acylnitroso HDA reactions in regard to the effect of the solvent polarity on the reaction selectivity. The selectivity in intermolecular nitroso HDA reactions has generally been insensitive to solvent polarity; however, the use of aqueous media for intramolecular acylnitroso HDA reactions resulted in a significant enhancement of the diastereoselectivity.[194] Thus, cycloadduct 193 was formed more selectively over cycloadduct 192 when hydroxamic acid 191 was oxidized in aqueous solvent mixtures compared to in nonpolar solvents. Cycloadduct 193 was transformed into the monocyclic intermediate 194, which was further elaborated to (−)-lepadins 195a–c. Kibayashi and co-workers have also used a similar approach for the synthesis of the pumiliotoxin alkaloids.[194–197]

Scheme 36.

Total synthesis of (−)-lepadins A, B, and C. MOM = methoxymethyl, TBDPS =tert-butyldiphenylsilyl.

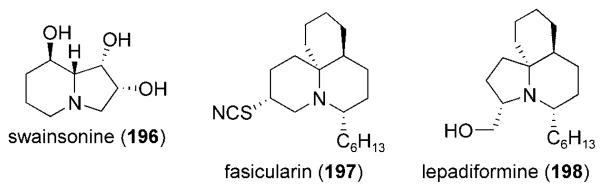

8.3. Indolidizine and Pyrrolidizine Alkaloids

Pyrrolizidine and indolizidine alkaloids have been isolated from a wide variety of natural sources and have demonstrated interesting biological properties.[198] Representative compounds of this class of alkaloids that have been synthesized by using an intramolecular acylnitroso HDA strategy include swainsonine (196) and its derivatives,[199,200] fasicularin (197) and lepadiformine (198),[201] and other indolizidine alkaloids (Figure 13).[187,189,199,202–209]

Figure 13.

Representative indolidizine and pyrrolidizine alkaloids.

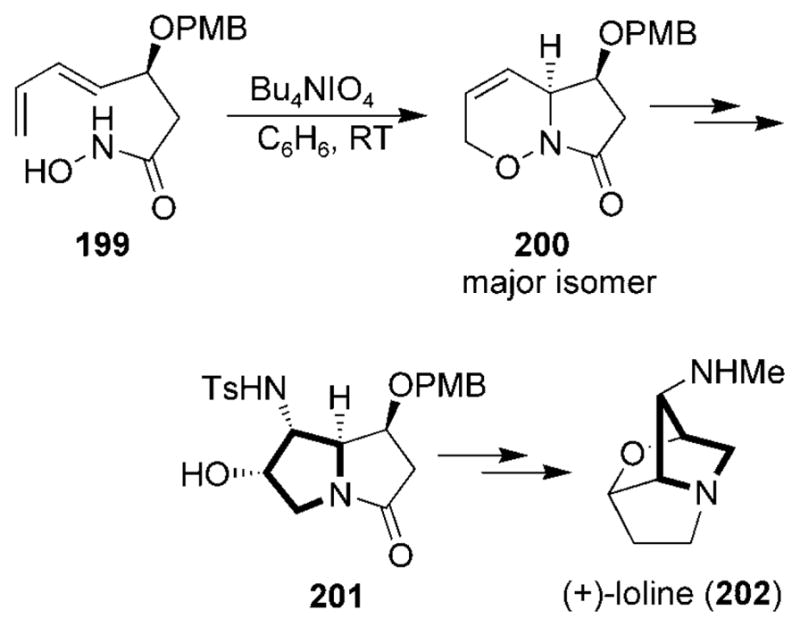

The synthesis of a particularly interesting member of the pyrrolidizine class of alkaloids, (+)-loline (202) was achieved by using an intramolecular acylnitroso HDA strategy (Scheme 37).[210,211] Hydroxamic acid 199 was oxidized to yield the oxazine 200. Subsequent modifications yielded the intermediate 201 which was converted into (+)-loline 202.

Scheme 37.

Total synthesis of (+)-loline. PMB =para-methoxybenzyl.

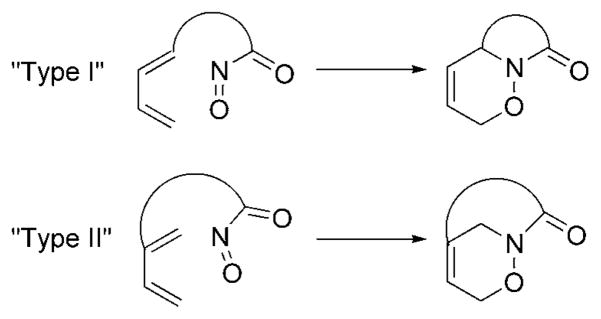

8.4. Bridged Oxazinolactams Using Type II Intramolecular Cycloadditions

The vast majority of intramolecular acylnitroso HDA reactions have involved the use of dienes tethered at the 1-position. In “type II” intramolecular acylnitroso HDA reactions, the 2-position of the diene is tethered (Figure 14), which provides access to bridged oxazinolactam compounds.

Figure 14.

Type I and type II intramolecular nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions.

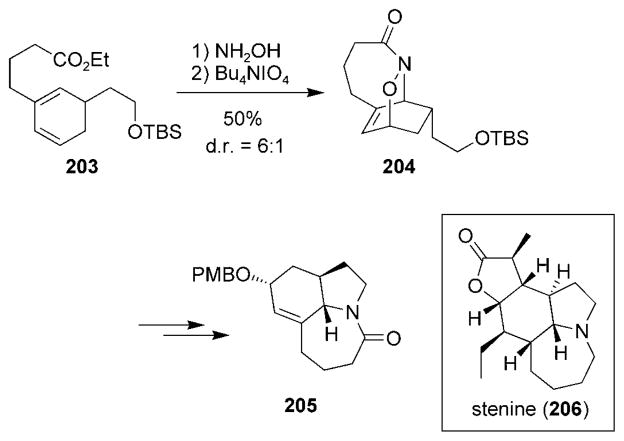

Recently, the synthesis of the tricyclic core of the alkaloid stenine (206) was reported by using a type II intramolecular acylnitroso HDA reaction (Scheme 38).[212] Ethyl ester 203 was converted into a hydroxamic acid, which upon oxidation yielded the tricyclic structure 204. Subsequent modification led to advanced intermediate 205.

Scheme 38.

A recent example of a type II intramolecular nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction.

Other examples of the use of type II intramolecular acylnitroso HDA reactions in synthetic applications have been reported by the Shea research group,[213–216] and demonstrate the potential of these often overlooked variations of the more-typical type I intramolecular acylnitroso HDA reactions.

9. Summary and Outlook

Although the nitrosocarbonyl HDA reaction has been used toward the synthesis of a number of important biologically active substrates, there is still much room for method development surrounding the usage of the resulting 3,6-dihydro-1,2-oxazine ring in organic syntheses. The acylnitroso HDA reaction is a valuable tool for synthetic organic chemists, since it allows for the rapid construction of elaborate alkaloids in a stereocontolled manner. This Review is meant to serve as a reference to illustrate how the N–acyl, N–O, C–O, and C=C bonds of nitrosocarbonyl HDA cycloadducts can be functionalized. We encourage further research in nitrosocarbonyl HDA reactions so that the fundamental principles of the nitroso HDA reaction presented here can be applied to many new and exciting synthetic efforts.

10. Note Added in Proof

After submission of this manuscript, the recent study by Monbaliu et al., in which microreactor technology was used for HDA reactions of various nitroso dienophiles, was brought to our attention.[217] This is an excellent example of how new developments in the literature are improving the utility of an already powerful synthetic transformation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the NIH (GM068012 and GM075855) and Eli Lilly.

Biographies

Brian S. Bodnar received his BS from The College of New Jersey in 2003. He received his PhD in 2008 with Marvin J. Miller at the University of Notre Dame, where he synthesized natural product analogues. After working as a Research Scientist at SiGNa Chemistry, he is now employed as an Application Chemist with Chemspeed Technologies, where he provides chemistry service and support for automated platforms.

Marvin J. Miller was born in Dickinson, North Dakota, and received his BS in Chemistry at North Dakota State University. He then moved to Cornell University for graduate studies with G. Marc Loudon. After completing his PhD, he was an NIH postdoctoral fellow in the laboratories of Professor Henry Rapoport at UC Berkeley. In 1977, he moved to the University of Notre Dame and is now the George & Winifred Clark Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry. His research focus is on synthetic organic, bioorganic, and medicinal chemistry.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Professor Jeremiah P. Freeman

Contributor Information

Dr. Brian S. Bodnar, Chemspeed Technologies, Inc., 113 North Center Drive, North Brunswick, NJ 08906 (USA)

Prof. Marvin J. Miller, Email: mmiller1@nd.edu, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556 (USA), Fax: (+1)574-631-6652, Homepage: http://www.nd.edu/~mjmgroup/

References

- 1.Streith J, Defoin A. Synthesis. 1994:1107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinreb SM, Staib RR. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:3087. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Streith J, Defoin A. Synlett. 1996:189. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogt PF, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:1317. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H. Eur J Org Chem. 2006:2031. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldmann H. Synthesis. 1994:535. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto H, Kawasaki M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2007;80:595. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baeyer A. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1874;7:1638. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrlich P, Sachs F. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1899;32:2341. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto H, Momiyama N. Chem Commun. 2005:3514. doi: 10.1039/b503212c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Momiyama N, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1080. doi: 10.1021/ja0444637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto Y, Momiyama N, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5962. doi: 10.1021/ja049741g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momiyama N, Yamamoto H. Org Lett. 2002;4:3579. doi: 10.1021/ol026443k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adam W, Krebs O. Chem Rev. 2003;103:4131. doi: 10.1021/cr030004x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sha X, Isbell TS, Patel RP, Day CS, King SB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9687. doi: 10.1021/ja062365a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahr N, Guller R, Reymond JL, Lerner RA. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3550. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby GW. Chem Soc Rev. 1977;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labaziewicz H, Lindfors KR, Kejonen TH. Heterocycles. 1989;29:2327. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noguchi H, Aoyama T, Shioiri T. Heterocycles. 2002;58:471. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang D, Sueling C, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 1998;63:885. doi: 10.1021/jo971696q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tronchet JMJ, Jean E, Barbalat-Rey F, Bernardinelli G. J Chem Res Synop. 1992:228. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvet G, Guillot R, Blanchard N, Kouklovsky C. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:4395. doi: 10.1039/b513397a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reißig HU, Dugovič D, Zimmer R. Sci Synth. 2010;41:259. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller CA, Batey RA. Org Lett. 2004;6:699. doi: 10.1021/ol0363117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirby GW, McGuigan H, Mackinnon JWM, Mclean D, Sharma RP. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1985:1437. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware RW, Day CS, King SB. J Org Chem. 2002;67:6174. doi: 10.1021/jo0202839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware RW, Jr, King SB. J Org Chem. 2000;65:8725. doi: 10.1021/jo001230z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware RW, Jr, King SB. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6769. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singal KK, Singh B, Raj B. Synth Commun. 1993;23:107. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gouverneur V, Dive G, Ghosez L. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1991;2:1173. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirby GW, Sweeny JG. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1973:704. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirby GW, Sweeny JG. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1981:3250. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin SF, Hartmann M, Josey JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:3583. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dao LH, Dust JM, Mackay D, Watson KN. Can J Chem. 1979;57:1712– 1719. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenkins NE, Ware RW, Jr, Atkinson RN, King SB. Synth Commun. 2000;30:947. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard JAK, Ilyashenko G, Sparkes HA, Whiting A. Dalton Trans. 2007:2108. doi: 10.1039/b704728b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwasa S, Fakhruddin A, Tsukamoto Y, Kameyama M, Nishiyama H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:6159. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flower KR, Lightfoot AP, Wan H, Whiting A. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 2002:2058. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flower KR, Lightfoot AP, Wan H, Whiting A. Chem Commun. 2001:1812. doi: 10.1039/b106338n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iwasa S, Tajima K, Tsushima S, Nishiyama H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:5897. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard JAK, Ilyashenko G, Sparkes HA, Whiting A, Wright AR. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:869. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adamo MFA, Bruschi S. J Org Chem. 2007;72:2666. doi: 10.1021/jo062334y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quadrelli P, Mella M, Invernizzi AG, Caramella P. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:10497. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corrie JET, Kirby GW, Mackinnon JWM. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1985:883. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quadrelli P, Mella M, Caramella P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:797. [Google Scholar]

- 46.O3Bannon PE, William DP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:5719. [Google Scholar]

- 47.O3Bannon PE, Suelzle D, Schwarz H. Helv Chim Acta. 1991;74:2068. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen AD, Zeng BB, King SB, Toscano JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1444. doi: 10.1021/ja028978e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gouverneur V, McCarthy SJ, Mineur C, Belotti D, Dive G, Ghosez L. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:10537. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Defoin A, Brouillard-Poichet A, Streith J. Helv Chim Acta. 1992;75:109. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang YC, Lu TM, Elango S, Lin CK, Tsai CT, Yan TH. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2002;13:691. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cardillo B, Galeazzi R, Mobbili G, Orena M, Rossetti M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:1535. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller A, Procter G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1041. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller A, Paterson TM, Procter G. Synlett. 1989:32. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corrie JET, Kirby GW, Sharma RP. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1982:1571. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wichterle O. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1947;12:292. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arbuzov YA. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1948;60:993. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leach AG, Houk KN. Chem Commun. 2002:1243. doi: 10.1039/b111251c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leach AG, Houk KN. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5192. doi: 10.1021/jo0104126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCarrick MA, Wu YD, Houk KN. J Org Chem. 1993;58:3330. [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCarrick MA, Wu YD, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1499. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boger DL, Patel M, Takusagawa F. J Org Chem. 1985;50:1911. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lemire A, Beaudoin D, Grenon M, Charette AB. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2368. doi: 10.1021/jo048216x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dubey SK, Knaus EE. J Org Chem. 1985;50:2080. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aoyagi S, Tanaka R, Naruse M, Kibayashi C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:4513. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vogt PF, Hansel JG, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:2803. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ritter AR, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 1994;59:4602. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pepper AG, Procter G, Voyle M. Chem Commun. 2002:1066. doi: 10.1039/b201645c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morley AD, Hollinshead DM, Procter G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1047. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller A, Procter G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1043. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kirby GW, Nazeer M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:6173. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Behr JB, Chevrier C, Defoin A, Tarnus C, Streith J. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:543. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Defoin A, Pires J, Streith J. Synlett. 1991:417. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hussain A, Wyatt PB. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:2123. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arribas C, Carreno MC, Garcia-Ruano JL, Rodriguez JF, Santos M, Ascension Sanz-Tejedor M. Org Lett. 2000;2:3165. doi: 10.1021/ol0063611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carreno MC, Cid MB, Garcia Ruano LJ, Santos M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:1405. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hudlicky T, Olivo HF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:6077. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lightfoot AP, Pritchard RG, Wan H, Warren JE, Whiting A. Chem Commun. 2002:2072. doi: 10.1039/b206366b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4128. doi: 10.1021/ja049849w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Krchnak V, Moellmann U, Dahse HM, Miller MJ. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:94. doi: 10.1021/cc700140h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krchnak V, Moellmann U, Dahse HM, Miller MJ. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:112. doi: 10.1021/cc700142d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krchnak V, Moellmann U, Dahse HM, Miller MJ. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:104. doi: 10.1021/cc7001414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Faita G, Mella M, Paio AM, Quadrelli P, Seneci P. Eur J Org Chem. 2002;2002:1175. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Quadrelli P, Scrocchi R, Piccanello A, Caramella P. J Comb Chem. 2005;7:887. doi: 10.1021/cc050056v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Keck GE, Webb RR, Yates JB. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:4007. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tsoungas PG. Heterocycles. 2002;57:1149. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsoungas PG. Heterocycles. 2002;57:915. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Le Flohic A, Meyer C, Cossy J, Desmurs JR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:8577. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang YK, Choi JH, Tae J. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6995. doi: 10.1021/jo050957q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang Y-K, Tae J. Synlett. 2003:2017. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Reißig HU, Zimmer R. Sci Synth. 2006;33:371. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sibi MP, Ma Z, Jasperse CP. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5764. doi: 10.1021/ja0421497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ganton MD, Kerr MA. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8554. doi: 10.1021/jo048768f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kumarn S, Shaw DM, Longbottom DA, Ley SV. Org Lett. 2005;7:4189. doi: 10.1021/ol051577u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gallos JK, Stathakis CI, Kotoulas SS, Koumbis AE. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6884. doi: 10.1021/jo050987t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cicchi S, Goti A, Brandi A, Guarna A, De Sarlo F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:3351. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nitta M, Kobayashi T. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1985:1401. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Keck GE, Wager TT, McHardy SF. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:11755. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Keck GE, McHardy SF, Wager TT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:7419. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cesario C, Tardibono LP, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2009;74:448. doi: 10.1021/jo802184y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee YH, Choo DJ. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 1993;14:423. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Klier K, Kresze G, Werbitzky O, Simon H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:2677. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Galvani G, Calvet G, Blanchard N, Kouklovsky C. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:1063. doi: 10.1039/b718787d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Calvet G, Blanchard N, Kouklovsky C. Synthesis. 2005:3346. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mulvihill MJ, Gage JL, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 1998;63:3357. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kefalas P, Grierson DS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:3555. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kornblum N, DeLaMare HE. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:880. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Desai MC, Doty JL, Stephens LM, Brighty KE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:961. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mulvihill MJ, Surman MD, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 1998;63:4874. doi: 10.1021/jo016275u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Surman MD, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2001;66:2466. doi: 10.1021/jo010094a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Muxworthy JP, Wilkinson JA, Procter G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:7539. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Muxworthy JP, Wilkinson JA, Procter G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:7535. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bodnar BS, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:796. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.11.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Surman MD, Mulvihill MJ, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4115. doi: 10.1021/jo016275u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pineschi M, DelMoro F, Crotti P, Macchia F. Org Lett. 2005;7:3605. doi: 10.1021/ol050895q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pineschi M, Del Moro F, Crotti P, Macchia F. Pure Appl Chem. 2006;78:463. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen W, Day CS, King SB. J Org Chem. 2006;71:9221. doi: 10.1021/jo0615192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Surman MD, Mulvihill MJ, Miller MJ. Org Lett. 2002;4:139. doi: 10.1021/ol017036w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee W, Kim KH, Surman MD, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2003;68:139. doi: 10.1021/jo026488z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cesario C, Miller MJ. Org Lett. 2009;11:1293. doi: 10.1021/ol9000685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Calvet G, Blanchard N, Kouklovsky C. Org Lett. 2007;9:1485. doi: 10.1021/ol0702066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ellis JM, King SB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:5833. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bigeault J, Giordano L, deRiggi I, Gimbert Y, Buono G. Org Lett. 2007;9:3567. doi: 10.1021/ol071386m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ranganathan S, George KS. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:3347. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lin CC, Wang YC, Hsu JL, Chiang CC, Su DW, Yan TH. J Org Chem. 1997;62:3806. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cowart M, Bennett MJ, Kerwin JF. J Org Chem. 1999;64:2240. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Quadrelli P, Mella M, Paganoni P, Caramella P. Eur J Org Chem. 2000:2613. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Quadrelli P, Scrocchi R, Caramella P, Rescifina A, Piperno A. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:3643. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bodnar BS, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2007;72:3929. doi: 10.1021/jo0701987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Freer AA, Islam MA, Kirby GW, Mahajan MP. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1991:1001. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kirby GW, Mackinnon JWM. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1985:887. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jeong LS, Lee JA. Antiviral Chem Chemother. 2004;15:235. doi: 10.1177/095632020401500502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rodriguez JB, Comin MJ. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2003;3:95. doi: 10.2174/1389557033405331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Roy A, Schneller SW. J Org Chem. 2003;68:9269. doi: 10.1021/jo030238g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schneller SW. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:1087. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hansel J-G, O3Hogan S, Lensky S, Ritter AR, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:2913. [Google Scholar]

- 137.De Clercq E. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2005;24:1395. doi: 10.1080/15257770500265638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Shireman BT, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9537. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mulvihill MJ, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:6605. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zhang D, Ghosh A, Suling C, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:3799. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ghosh A, Ritter AR, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 1995;60:5808. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Jiang MXW, Jin B, Gage JL, Priour A, Savela G, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2006;71:4164. doi: 10.1021/jo060224l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lin W, Gupta A, Kim KH, Mendel D, Miller MJ. Org Lett. 2009;11:449. doi: 10.1021/ol802553g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Li F, Brogan JB, Gage JL, Zhang D, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2004;69:4538. doi: 10.1021/jo0496796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kim KH, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:4571. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Behr JB, Defoin A, Mahmood N, Streith J. Helv Chim Acta. 1995;78:1166. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Joubert M, Defoin A, Tarnus C, Streith J. Synlett. 2000:1366. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Defoin A, Pires J, Streith J. Synlett. 1990:111. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Robinson R. J Chem Soc. 1917;111:762. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Iida H, Watanabe Y, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 1985;50:1818. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Aoyagi S, Tanaka R, Naruse M, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 1998;63:8397. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Bathgate A, Malpass JR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:5937. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Smith CR, Justice D, Malpass JR. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:11037. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Malpass JR, Hemmings DA, Wallis AL, Fletcher SR, Patel S. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 2001:1044. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Malpass JR, Smith C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:273. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Justice DE, Malpass JR. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:11977. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Groetzl B, Handa S, Malpass JR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:9147. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Soulie J, Betzer JF, Muller B, Lallemand JY. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:9485. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Martin SF. In: The Alkaloids. Brossi AR, editor. Vol. 31. Academic Press; New York: 1987. p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Hudlicky T, Rinner U, Gonzalez D, Akgun H, Schilling S, Siengalewicz P, Martinot TA, Pettit GR. J Org Chem. 2002;67:8726. doi: 10.1021/jo020129m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Gonzalez D, Martinot T, Hudlicky T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:3077. [Google Scholar]

- 162.Hudlicky T, Olivo HF. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9694. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Martin SF, Tso HH. Heterocycles. 1993;35:85. [Google Scholar]

- 164.Shukla KH, Boehmler DJ, Bogacyzk S, Duvall BR, Peterson WA, McElroy WT, DeShong P. Org Lett. 2006;8:4183. doi: 10.1021/ol061070z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Olivo HF, Hemenway MS, Hartwig AC, Chan R. Synlett. 1998:247. [Google Scholar]

- 166.Li F, Warshakoon NC, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8836. doi: 10.1021/jo048606j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Li F, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2006;71:5221. doi: 10.1021/jo060555y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Nora GP, Miller MJ, Moellmann U. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:3966. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Ding P, Miller MJ, Chen Y, Helquist P, Oliver AJ, Wiest O. Org Lett. 2004;6:1805. doi: 10.1021/ol049473r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Surman MD, Mulvihill MJ, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:1131. [Google Scholar]

- 171.Heinz LJ, Lunn WHW, Murff RE, Paschal JW, Spangle LA. J Org Chem. 1996;61:4838. doi: 10.1021/jo960241i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Ritter AR, Miller MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:9379. [Google Scholar]

- 173.Shireman BT, Miller MJ, Jonas M, Wiest O. J Org Chem. 2001;66:6046. doi: 10.1021/jo010284l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Shireman BT, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4809. doi: 10.1021/jo015544d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Jiang MXW, Warshakoon NC, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2824. doi: 10.1021/jo0484070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Lee W, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2004;69:4516. doi: 10.1021/jo0495034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Mineno T, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2003;68:6591. doi: 10.1021/jo034316b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Surman MD, Miller MJ. Org Lett. 2001;3:519. doi: 10.1021/ol006813+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Horsewood P, Kirby GW, Sharma RP, Sweeny JG. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1981:1802. [Google Scholar]

- 180.Kirsch G, Golde R, Neef G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:4497. [Google Scholar]

- 181.Perez-Medrano A, Grieco PA. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:1057. [Google Scholar]

- 182.Li F, Yang B, Miller MJ, Zajicek J, Noll BC, Mllmann U, Dahse HM, Miller PA. Org Lett. 2007;9:2923. doi: 10.1021/ol071322b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Krchnak V, Waring KR, Noll BC, Mllmann U, Dahse HM, Miller MJ. J Org Chem. 2008;73:4559. doi: 10.1021/jo8004827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Gourlay RI, Kirby GW. J Chem Res Synop. 1997:152. [Google Scholar]

- 185.Sheldrake GN, Soissons N. J Org Chem. 2006;71:789. doi: 10.1021/jo052016j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.McAuley BJ, Nieuwenhuyzen M, Sheldrake GN. Org Lett. 2000;2:1457. doi: 10.1021/ol000057q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Keck GE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:4767. [Google Scholar]

- 188.Kibayashi C, Aoyagi S. Synlett. 1995:873. [Google Scholar]

- 189.Watanabe Y, Iida H, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 1989;54:4088. [Google Scholar]

- 190.Aoyagi S, Shishido Y, Kibayashi C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:4325. [Google Scholar]

- 191.Sato T, Aoyagi S, Kibayashi C. Org Lett. 2003;5:3839. doi: 10.1021/ol030088w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Ozawa T, Aoyagi S, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 2001;66:3338. doi: 10.1021/jo001589n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Ozawa T, Aoyagi S, Kibayashi C. Org Lett. 2000;2:2955. doi: 10.1021/ol000153r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Naruse M, Aoyagi S, Kibayashi C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:9213. [Google Scholar]

- 195.Aoyagi S, Hirashima S, Saito K, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 2002;67:5517. doi: 10.1021/jo0200466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Kibayashi C, Aoyagi S. Yuki Gosei Kagaku Kyokaishi. 1999;57:981. [Google Scholar]

- 197.Naruse M, Aoyagi S, Kibayashi C. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1996:1113. [Google Scholar]

- 198.Liddell JR. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:773. doi: 10.1039/b108975g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Keck GE, Romer DR. J Org Chem. 1993;58:6083. [Google Scholar]

- 200.Naruse M, Aoyagi S, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 1994;59:1358. [Google Scholar]

- 201.Abe H, Aoyagi S, Kibayashi C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1205. [Google Scholar]

- 202.Keck GE, Nickell DG. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:3632. [Google Scholar]

- 203.Iida H, Watanabe Y, Kibayashi C. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:5534. [Google Scholar]

- 204.Yamazaki N, Kibayashi C. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:1396. [Google Scholar]

- 205.Machinaga N, Kibayashi C. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1991:405. [Google Scholar]

- 206.Shishido Y, Kibayashi C. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1991:1237. [Google Scholar]

- 207.Machinaga N, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 1992;57:5178. [Google Scholar]

- 208.Shishido Y, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 1992;57:2876. [Google Scholar]

- 209.Yamazaki N, Ito T, Kibayashi C. Org Lett. 2000;2:465. doi: 10.1021/ol990389z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 210.Blakemore PR, Kim S-K, Schulze VK, White JD, Yokochi AFT. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 2001:1831. [Google Scholar]

- 211.Blakemore PR, Schulze VK, White JD. Chem Commun. 2000:1263. [Google Scholar]

- 212.Zhu L, Lauchli R, Loo M, Shea KJ. Org Lett. 2007;9:2269. doi: 10.1021/ol070397c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 213.Molina CL, Chow CP, Shea KJ. J Org Chem. 2007;72:6816. doi: 10.1021/jo070978f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 214.Sparks SM, Chow CP, Zhu L, Shea KJ. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3025. doi: 10.1021/jo049897z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 215.Chow CP, Shea KJ, Sparks SM. Org Lett. 2002;4:2637. doi: 10.1021/ol026075k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 216.Sparks SM, Vargas JD, Shea KJ. Org Lett. 2000;2:1473. doi: 10.1021/ol005811m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 217.Monbaliu JCMR, Cukalovic A, Marchand-Brynaert J, Stevens CV. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:5830. [Google Scholar]