Those educating healthcare professionals face the undeniable challenge that the current U.S. healthcare system is untenable.1 U.S. health care epitomizes low value—spending more than any other country while ranked 37th in the world—between Costa Rica and Slovenia, in its ability to equitably engender health.2 The September 14–15, 2010 conference on Patients and Populations: Public Health in Medical Education, sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the CDC, provided inspiring examples from those who are trying to show the healthcare professionals of the future a better way.

Yet, with U.S. healthcare spending American business into noncompetitiveness,3 mortgaging not only our children’s but our grandchildren’s futures, the task is more than to bring a public health understanding into the mainstream of research and medical education.4–6 The urgent need is to inspire and enable the younger generation to spring over the current dysfunctional medico-industrial complex, to bubble up diverse new streams that together create a torrential delta of change, so that quality health care becomes about both health and caring, accessible to all, while still leaving resources to strengthen the social and environmental determinants of health.5

This daunting task—providing high-value health care for all while spending less and doing more to improve the actual health of the population—requires a different way of understanding health care and health than the current biomedical model. It requires a more inclusive way of framing the generation of new knowledge and of applying that knowledge in education and practice. This reframing involves raising the gaze and spanning boundaries.

Raising the Gaze

A reductionist biomedical enterprise has made impressive strides in understanding disease mechanisms and in curing or ameliorating certain diseases.7–9 But as the predominant health problems increasingly relate to chronic more than acute illness10; as multimorbidity becomes the norm in an aging population11–14; as health behavior, the education and employment of the population, and other social and environmental determinants become the predominant drivers of health15; a fragmented approach to understanding and advancing health becomes less and less effective, and the need for a complementary more inclusive approach has become more apparent.7, 16, 17

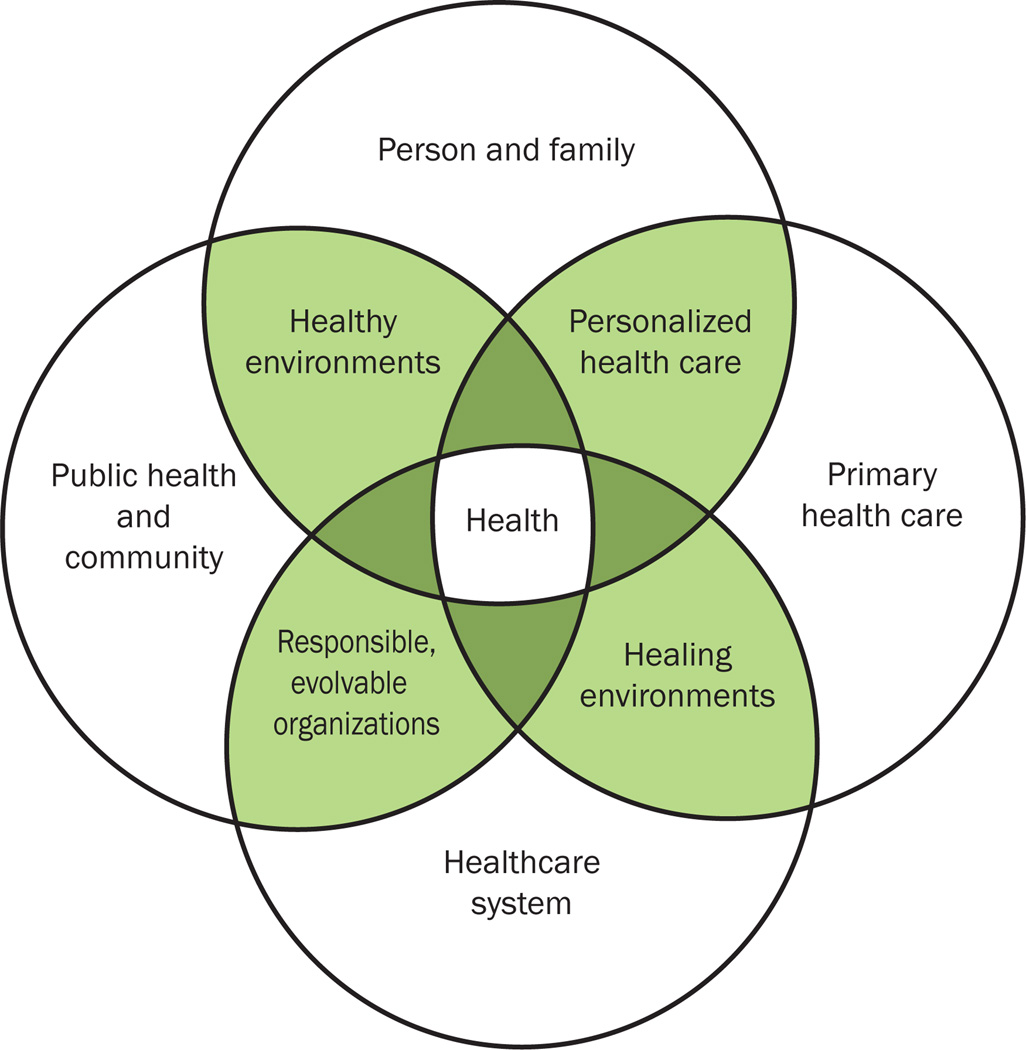

A different lens with which to see the problem becomes vital.18, 19 This lens not only focuses on smaller and smaller parts, but also elevates the gaze upward—from molecule to person, from person to system, system to community, community to environment.20 Shown in the Figure as four circles, a gaze that takes in the broad factors affecting health includes: individuals and families, primary health care, healthcare systems, public health and communities. This elevated view recognizes that people live in a social context and their health is more than the sum of their diseases.21, 22 It recognizes that healthcare systems based on primary care have better population health, higher-quality health care at lower cost, and less inequality than systems based on more fractured approaches.23–25 It takes a systems perspective to health care, public health, and community.

Figure 1.

Promoting health across boundaries

As Risa Lavizzo-Mourey and David Williams note in an article in another recent supplement to the American Journal of Preventive Medicine:

There is more to health than health care. Where we live, work, learn, and play can affect our health more than what happens in the physician’s office. Yet, ask our national leaders, “What determines health?” and you’ll hear about access to health care. As vital as health care and healthcare reform are, they are just part of the answer.26

Moving beyond health care to a broader view of health as a state that enables people to do valued life activities can totally reframe our health promotion efforts. Health can be understood as:

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity21

a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living; it is a positive concept, emphasizing social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities27

conditions that enable a person to work to achieve his or her biological and chosen potential28

membership in community29

the biological, social, and psychological ability that affords an equal opportunity for each individual to function in the relationships appropriate to his or her cultural context at any point in the life cycle30

the ability to develop meaningful relationships and pursue a transcendent purpose in a finite life31

Any of these inclusive, grounded, meaningful definitions of health helps to refocus energy toward solutions to the U.S. health and healthcare crisis, rather than toward more of the same. The enabling importance of focusing on health is indicated in the Figure by its centrality.

Boundary Spanning

Boundary spanning is reaching across borders to “build relationships, interconnections, and interdependencies”32 in order to manage complex problems. Boundary-spanning individuals develop partnerships and collaboration by “building sustainable relationships, managing through influence and negotiation, and seeking to understand motives, roles, and responsibilities.”32 Boundary-spanning organizations33 create “strategic alliances, joint working arrangements, networks, partnerships, and many other forms of collaboration across organizational boundaries. ”32 Boundary spanning can be a source of innovation and of solving the problems created by working narrowly.34–37

Transdisciplinary,38–48 multilevel49–51 research, education, and practice, and boundary-spanning efforts to promote health52 have great potential to build on the strengths of more narrowly focused approaches, while transcending their weaknesses.53 Many of these boundaries relate to crossing ideologies, disciplines, cultures, markets, peoples, and entrenched worldviews. As shown in the Figure and outlined below, boundaries that are important to span to advance health relate to (1) personalized health care; (2) healing environments; (3) responsible, evolvable organizations; and (4) healthy environments.

- Personalized health care—a relationship between a clinician and care team with the individual and family that includes:24, 54

- accessibility as the first contact with the healthcare system;

- a comprehensive whole-person approach;

- coordination of care across settings, and integration of care of acute and chronic illnesses, mental health and prevention; and

- a sustained partnership over time.

- Healing environments—restorative settings and conditions, including:

- trustworthy, invested interpersonal and interorganizational relationships;

- situations that enable a balance of action and reflection;

- physical space that provides access to nature, light, privacy or positive sensory experience; and

- meaningful work or activity.

- Responsible organizations that move beyond sustaining past successes to continued development based on making sense of a rapidly changing environment—moving from sustainability to evolvability. Such organizations that enable health by:

- following sound environmental procedures;

- operating with integrity;

- being accountable to employees, customers, vendors and the communities in which they operate;

- recognizing the impact of their actions on the physical; emotional and social well-being of individuals and communities; and

- developing to meet emerging needs and conditions.

- Healthy environments—physical and social surroundings that foster health, including:

- clean air, water and sanitation;

- affordable, accessible, nutritious food, especially fruits and vegetables;

- safe, affordable, comfortable and pest-free housing;

- safe, spacious areas for walking;

- crime-free neighborhoods and violence-free homes;

- economic opportunities; and

- affordable and available education.

Generating and Learning the Relevant Knowledge

Fortunately, different ways of knowing19 and of generating knowledge55, 56 are emerging. These emergent approaches have great potential to complement the dominant reductionist models of knowledge generation and use57–60 to enable boundary spanning that advances health. The new models include participatory50, 61–65 and practice-based network research,62, 66–76 multimethod approaches that integrate quantitative and qualitative methods,77–83 and theories that recognize the complex adaptive nature of the systems that relate to health and health care.13, 80, 84–95 Glimmers of support for these more inclusive approaches to research are seen in the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards, CDC Prevention Research Centers, and the CDC– AAMC Cooperative Agreement that led to this journal supplement. Even the comparative effectiveness research movement96–99 has potential to step in a more systemic direction as it struggles to move from a focus on drugs and devices96 to comparing different systems affecting health care and health.100

I invite readers who are interested in the emerging effects of boundary spanning and health to share your own stories or knowledge from other sources at the website of the Promoting Health Across Boundaries initiative (www.PHAB.org).

Daniel Federman, in his address at the 2007 American Association of Medical Colleges Annual Meeting commented:

I believe we should enlist some medical students as agents of change, committed to designing a system of care that is equitable, cost-effective, prevention-oriented, universal, and thus moral. I suggest…an activist focus, and consistent mentoring.5, 101

The 2010 conference on Patients and Populations: Public Health in Medical Education advanced this vision beyond medical students to include multiple disciplines, generations, organizations, and communities that care about health. The hard work of the boundary spanner is needed in research, education, systems development, and practice. Combined with an inclusive view of health and an elevated gaze, there is great cause for hope.31

Acknowledgments

Mary Ruhe and Heide Aungst helped to develop many of the ideas contained in this manuscript. Dr. Stange’s time is supported in part by a Clinical Research Professorship from the American Cancer Society and by the Case Western Reserve University/Cleveland Clinic Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative, Grant Number UL1 RR024989 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, the NIH or the ACS.

Publication of this article was supported by the CDC–AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges) Cooperative Agreement number 5U36CD319276.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the author of this paper.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. [Accessed March 23, 2011];Press Release WHO/44: World Health Organization assesses the world's health systems. 2000 www.who.int/inf-pr-2000/en/pr2000-44.html.

- 3.Congress of the United States, Congressional Budget Office. [Accessed July 14, 2010];The Long-Term Outlook for Health Care Spending. Pub. No. 3085, November [pdf] 2007 www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/87xx/doc8758/11-13-LT-Health.pdf.

- 4.Maeshiro R, Johnson I, Koo D, et al. Medical education for a healthier population: reflections on the Flexner Report from a public health perspective. Acad Med. 2010 Feb;85(2):211–219. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c885d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maeshiro R. Responding to the challenge: population health education for physicians. Acad Med. 2008 Apr;83(4):319–320. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318166ae9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeshiro R. Public health practice and academic medicine: promising partnerships regional medicine public health education centers--two cycles. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006 Sep-Oct;12(5):493–495. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200609000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauli HG, White KL, McWhinney IR. Medical education, research, and scientific thinking in the 21st century (part three of three) Education for health (Abingdon, England) 2000;13(2):173–186. doi: 10.1080/13576280050074435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesko LJ. Personalized medicine: elusive dream or imminent reality? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007 Jun;81(6):807–816. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw SE, Greenhalgh T. Best research--for what? Best health--for whom? A critical exploration of primary care research using discourse analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008 Jun;66(12):2506–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004 Mar 10;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Lapointe L. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005 May-Jun;3(3):223–228. doi: 10.1370/afm.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortin M, Soubhi H, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity's many challenges. Time to focus on the needs of this vulnerable and growing population. BMJ. 2007 May 19;334(7602):1016–1017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39201.463819.2C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009 Jul-Aug;7(4):357–363. doi: 10.1370/afm.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004 Dec 30;351(27):2870–2874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. [Accessed August 13, 2010];Commission on Social Determinants of Health - Final Report. 2008 www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.html.

- 16.Bulger RJ. Reductionist biology and population medicine - strange bedfellows or a marriage made in heaven? JAMA. 1990;264(4):508–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturmberg JP. Systems and complexity thinking in general practice: part 1 - clinical application. Aust. Fam. Physician. 2007 Mar;36(3):170–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stange KC, et al. Integrative approaches to promoting health and personalized, high-value health care: a science of connectedness and the practice of generalism. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009–2010 www.annfammed.org/cgi/collection/editorial_series. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stange KC. Ways of knowing, learning, and developing. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010 Jan-Feb;8(1):4–10. doi: 10.1370/afm.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009;7(2):100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Definition of Health. 1948 www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html.

- 22.World Health Organization. [Accessed June 30, 2010];Declaration of Alma-Ata: International conference on primary health care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. 1978 www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf.

- 23.Starfield B, Shi LY, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, editors. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Affair. 2010 May;29(5):766–772. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavizzo-Mourey R, Williams DR. Strong medicine for a healthier America: introduction. Am J Prev Med. 2011 Jan;40(1) Suppl 1:S1–S3. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.First International Conference on Health Promotion. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1; 1986. Nov 21, [Accessed January 18, 2011]. www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seedhouse D. Health: The Foundations for Achievement. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berry W. Health is membership. In: Wirzba N, editor. The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays of Wendell Berry. Berkeley: Counterpoint : Distributed by Publishers Group West; 2002. pp. 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine M, Peters JW. The Nature of Health: How America Lost, and Can Regain, A Basic Human Value. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Radcliffe Publishing Limited; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stange KC. Power to advocate for health. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010;8(2):100–107. doi: 10.1370/afm.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams PT. The competent boundary spanner. Public Admin. 2002;80(1):103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levina N, Vaast E. The emergence of boundary spanning competence in practice: implications for information systems' implementation and use. MIS Quarterly. 2005 Jun;29(2):335–363. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aldrich H, Herker D. Boundary Spanning Roles and Organization Structure. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1977;2(2) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller PM. Examining the work of boundary spanning leaders in community contexts. International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice. 2008;11(4):353–377. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weerts DJ, Sandmann LR. Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. The Journal of Higher Education. 2010;81(6):702–726. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu S-H, Wang Y-C, Tzeng SF. The Source of Innovation: Boundary Spanner. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence. 2007;18(10):1133–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: the National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98(9):1608–1615. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Syme SL. The science of team science: assessing the value of transdisciplinary research. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S94–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stokols D, Misra S, Moser RP, Hall KL, Taylor BK. The ecology of team science: understanding contextual influences on transdisciplinary collaboration. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S96–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nash JM. Transdisciplinary training: key components and prerequisites for success. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S133–S140. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mabry PL, Olster DH, Morgan GD, Abrams DB. Interdisciplinarity and systems science to improve population health: a view from the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S211–S224. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein JT. Evaluation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: a literature review. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S116–S123. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kessel F, Rosenfield PL. Toward transdisciplinary research: historical and contemporary perspectives. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S225–S234. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harper GW, Neubauer LC, Bangi AK, Francisco VT. Transdisciplinary research and evaluation for community health initiatives. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(4):328–337. doi: 10.1177/1524839908325334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emmons KM, Viswanath K, Colditz GA. The role of transdisciplinary collaboration in translating and disseminating health research: lessons learned and exemplars of success. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S204–S210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Croyle RT. The National Cancer Institute's transdisciplinary centers initiatives and the need for building a science of team science. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S90–S93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stokols D. Toward a science of transdisciplinary action research. Am J. Community Psychol. 2006;38(1–2):63–77. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petermann L, Petz G. The E2D2 Model: a dynamic approach to cancer prevention interventions. Health Promot Pract. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1524839909357317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schensul JJ. Community, culture and sustainability in multilevel dynamic systems intervention science. Am J. Community Psychol. 2009;43(3–4):241–256. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taplin SH, Rodgers AB. Toward improving the quality of cancer care: addressing the interfaces of primary and oncology-related subspecialty care. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2010;2010(40):3–10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richter AW, West MA, Dick RV, Dawson JF. Boundary spanners’ identification, intergroup contact, and effective intergroup relations. Acad. Manage. J. 2006;49(6):1252–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burt RS. Structural holes and good ideas. The American Journal of Sociology. 2004;110(2):349–399. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010;25(6):601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stange KC. A science of connectedness. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009;7(5):387–395. doi: 10.1370/afm.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stange KC, Miller WL, McWhinney I. Developing the knowledge base of family practice. Fam. Med. 2001;33(4):286–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Polanyi M. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McWhinney IR. Medical knowledge and the rise of technology. The Journal of medicine and philosophy. 1978 Dec;3(4):293–304. doi: 10.1093/jmp/3.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Best A, Hiatt RA, Norman CD. Knowledge integration: conceptualizing communications in cancer control systems. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008;71(3):319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wenger E, McDermott RA, Snyder W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: from process to outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where's the practice-based evidence? Fam. Pract. 2008 Sep 15; doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2008;29:325–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Macaulay AC, Commanda LE, Freeman WL, et al. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. North American Primary Care Research Group. BMJ. 1999;319(7212):774–778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed June 3, 2011];AHRQ Support for Primary Care Practice- Based Research Networks (PBRNs) 2001 Jun; revised February 2011. www.ahrq.gov/research/pbrn/pbrnfact.htm.

- 67.Fagnan LJ, Handley MA, Rollins N, Mold J. Voices from left of the dial: reflections of practice-based researchers. J. Am Board Fam. Med. 2010;23(4):442–451. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.090189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fagan LJ, Davis M, Deyo RA, Werner JJ, Stange KC. Linking practice-based research networks and Clinical and Transitional Science Awards: new opportunities for community engagement by academic health centers. Acad. Med. 2010;85(3):476–483. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181cd2ed3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Westfall JM, Fagnan LJ, Handley M, et al. Practice-based research is community engagement. J. Am Board Fam. Med. 2009 Jul-Aug;22(4):423–427. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baker EA, Brennan Ramirez LK, Claus JM, Land G. Translating and disseminating research-and practice-based criteria to support evidence-based intervention planning. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2008;14(2):124–130. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311889.83380.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research--"Blue Highways" on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007 Jan 24;297(4):403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Westfall JM, VanVorts RF, Main DS, Herbert C. Community-based participatory research in practice-based research networks. Ann. Fam. Med. 2006;4(1):8–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Macaulay AC, Nutting PA. Moving the frontiers forward: incorporating community-based participatory research into practice-based research networks. Ann. Fam. Med. 2006 Jan-Feb;4(1):4–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005 May 1;3(Suppl 1):S12–S20. doi: 10.1370/afm.303. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nutting PA, Beasley JW, Werner JJ. Practice-based research networks answer primary care questions. JAMA. 1999;281(8):686–688. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.8.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomas P, Griffiths F, Kai J, O'Dwyer A. Networks for research in primary health care. BMJ. 2001;322(7286):588–590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7286.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stange KC, Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Publishing multimethod research. Ann. Fam. Med. 2006 Jul-Aug;4(4):292–294. doi: 10.1370/afm.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stange KC, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, O'Connor PJ, Zyzanski SJ. Multimethod research: approaches for integrating qualitative and quantitative methods. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1994;9(5):278–282. doi: 10.1007/BF02599656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Addison RB, Gilchrist VJ, Kuzel A. Part III: the search for multimethod research. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Addison RB, Gilchrist VJ, Kuzel A, editors. Exploring Collaborative Research in Primary Care. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1994. pp. 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004;2(1):7–12. doi: 10.1370/afm.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Borkan JM. Mixed methods studies: a foundation for primary care research. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004;2(1):4–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sturmberg JP, Martin CM. Complexity and health--yesterday's traditions, tomorrow's future. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2009 Jun;15(3):543–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Peek CJ. Integrating care for persons, not only diseases. Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings. 2009 Mar;16(1):13–20. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9154-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miles A. Complexity in medicine and healthcare: people and systems, theory and practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2009 Jun;15(3):409–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heath I, Rubinstein A, Stange KC, van Driel ML. Quality in primary health care: a multidimensional approach to complexity. BMJ. 2009 Apr 2;338(apr02_1) doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1242. 2009 b1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leischow SJ, Best A, Trochim WM, et al. Systems thinking to improve the public's health. Am J. Prev. Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S196–S203. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilson T, Holt T, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: complexity and clinical care. BMJ. 2001;323(7314):685–688. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7314.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Plsek PE, Wilson T. Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations. BMJ. 2001;323(7315):746–749. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: the challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323(7313):625–628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, Stange KC. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J. Fam. Pract. 2001;50(10):872–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Albrecht G, Freeman S, Higginbotham N. Complexity and human health: the case for a transdisciplinary paradigm. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1998;22(1):55–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1005328821675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000 Sep 16;321(7262):694–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Volpp KG, Das A. Comparative effectiveness--thinking beyond medication A versus medication. B. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009 Jul 23;361(4):331–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0903496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Iglehart JK. Prioritizing comparative-effectiveness research--IOM recommendations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009 Jul 23;361(4):325–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hoffman A, Pearson SD. 'Marginal medicine': targeting comparative effectiveness research to reduce waste. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2009 Jul-Aug;28(4):w710–w718. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Conway PH, Clancy C. Comparative-effectiveness research--implications of the Federal Coordinating Council's report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009 Jul 23;361(4):328–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0905631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Glasgow RE, Steiner JS. Comparative effectiveness research that translates. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor E, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Federman DD. Healing and heeling; Address at the 2007 AAMC Annual Meeting; 2007. www.aamc.org/meetings/annual/2007/highlights/cohen_federman.pdf. [Google Scholar]