Abstract

Objective:

To examine the incidence and nature of emergency department (ED) presentations for nonfatal suicide-related behaviours (SRBs) over time, in boys and girls living in Ontario. We hypothesize declining rates (fiscal years [FYs] 2002/03 to 2006/07) ceased thereafter owing to renewed regulatory warnings against prescribing antidepressants and the economic recession.

Method:

We graphed and tested differences in ED SRB incidence rates for FYs 2002/03 to 2010/11. We estimated rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals using negative binomial regression controlling for changes in the underlying population (age, community size, and neighbourhood income quintile). We examined the nature of the incident (index) presentations over time in terms of the method(s) used and events occurring before and after the index event.

Results:

ED SRB incidence rates decreased by 30% in boys and girls from FYs 2002/03 to 2006/07, but not thereafter. This trend was most evident in girls who self-poisoned and in girls’ presentations to hospital with mental illness in the preceding year. Within a year of the index event, the proportion of girls with a repeat ED SRB presentation also declined by about one-third, but beyond FYs 2005/06 to 2009/10. However, the proportion admitted subsequent to the index event increased by about one-third. In boys, their patterns of presentations to hospital with mental illness and SRB repetition over time were similar to girls, but estimated with greater variability.

Conclusions:

While the decline in ED SRB rates to FY 2006/07 is encouraging, the lack of decline thereafter and an increase in subsequent admissions merits ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

Keywords: attempted suicide, adolescent, incidence, time factors, sex distribution

Abstract

Objectif :

Examiner l’incidence et la nature des présentations au service d’urgence (SU) pour des comportements suicidaires (CLS) non fatals au fil du temps, chez des garçons et filles habitant l’Ontario. Nous avons émis l’hypothèse que les taux à la baisse (pour les exercices financiers [EF] de 2002/03 à 2006/07) ont cessé en raison de mises en garde réglementaires renouvelées contre la prescription d’antidépresseurs et de la récession économique.

Méthode :

Nous avons dressé des tableaux et testé les différences des taux d’incidence des CLS en SU pour les exercices de 2002/03 à 2010/11. Nous avons estimé les rapports des taux et les intervalles de confiance à 95 % à l’aide de la régression binomiale négative en contrôlant les changements dans la population sous-jacente (âge, taille de la communauté, et quintile de revenu du quartier). Nous avons examiné la nature des présentations de l’incident (de référence) avec le temps en fonction de la ou aux méthodes utilisées, et des événements survenus avant et après l’incident de référence.

Résultats :

Les taux d’incidence des CLS en SU ont diminué de 30 % chez les garçons et filles dans les EF 2002/03 à 2006/07, mais pas par la suite. Cette tendance était la plus évidente chez les filles qui s’empoisonnaient elles-mêmes et dans les présentations à l’hôpital des filles ayant une maladie mentale l’année précédente. Dans l’année suivant l’événement de référence, la proportion des filles ayant des présentations répétées de CLS en SU a également diminué d’environ un tiers, mais au-delà des EF 2005/06 à 2009/10. Cependant, la proportion admise subséquemment à l’événement de référence a augmenté d’environ un tiers. Chez les garçons, les modèles de présentations de maladie mentale à l’hôpital et la répétition des CLS avec le temps étaient semblables à ceux des filles, mais étaient estimés avec une plus grande variabilité.

Conclusions :

Bien que la baisse des taux de CLS en SU jusqu’à EF 2006/07 soit encourageante, l’absence de diminution par la suite et une augmentation des hospitalisations subséquentes justifient une surveillance et une évaluation permanentes.

Suicide-related behaviours are defined as self-inflicted injuries or self-poisonings with suicidal, undetermined, or no suicidal intent.1,2 Hereafter, SRB refers to nonfatal acts and suicide, fatal acts. In Canada, suicide is the second leading cause of death in youth, representing almost one-quarter of all deaths in those aged 15 to 19 years.3 A hospital presentation for SRB is a strong risk factor for suicide in males and females.4–6 In a comprehensive review, Owens et al7 found that within 1 year of a hospital presentation for SRB, 16% of people of all ages will repeat and about 2% will die by suicide. Studies specific to younger populations have found that, compared with their population-based peers, the risk of mortality among those presenting to hospital with SRB is 3 to 4 times higher than expected, particularly for suicide (10 to 20 times higher).8,9

While both SRB and suicide onset in youth, there are distinct sex differences. SRB rates are higher in girls and peak in youth.10–15 In contrast, suicide rates are higher in boys16,17 and this sex difference persists into adulthood. Among Canadians ages 15 to 24 who die by suicide, almost three quarters are males (with a similar proportion in older age groups).18 Although the reasons for this gender paradox,19 first evident in youth, are not fully understood, one theory is girls may provide more opportunities to intervene, for example, through (repeat) ED presentations for SRB.20–22 Ideally, though, the need for such presentations could be prevented through integrated community and hospital-based services.23–29 To inform the development and targeting of preventive interventions, we assess whether there have been changes over time in hospital presentations for SRB in boys or girls.

Clinical Implications

Changes in the population (age, community size, and income) did not alter rates over time in boys or girls.

Factors that influenced the rates over time may be Ontario-specific and (or) broader.

Limitations

We lacked measures of integration between community and hospital-based services.

SRB hospital records do not identify suicidal intent.

Presentations to the ED for SRB do not represent SRB in the general population.

From the literature, it is unclear whether ED presentations for SRB have changed over the past decade in boys or girls. A time trends study (all ages) in 6 hospitals in England from 2000 to 2007 found ED SRB rates declined by 21% in males and 14% in females (in keeping with reported declines in suicide rates).30 Nevertheless, these rates (and in the subgroup who self-poisoned) were stable among youth aged 12 to 19 years in another study from these same 6 hospitals from 2000 to 2006. However, AD prescribing in the United Kingdom for youth decreased after the UK medicines and health care products regulatory authority warnings (December 2003).31 Thus an increase in ED SRB rates in response to the warnings in the United Kingdom may not have been captured as presentations to hospitals outside these 6 sites were not measured. Further, such data do not distinguish between suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury. Thus suicide attempt rates may have increased but been dampened by inclusion of nonsuicidal self-injury. More and more, the importance of distinguishing suicidal from nonsuicidal intent in youth and over time is recognized.32,33 Several countries experienced increases in youth suicide rates after the warnings (and ensuing media attention) against prescribing ADs to youth.34 In Manitoba, suicide rates increased by 25% in youth after the Health Canada regulatory warnings and hospital admissions for SRB (and depression) in youth did not change.35 Still, in the province of Alberta, Newton et al36 found the number of ED SRB pediatric presentations (predominately adolescent) decreased by 25% over FYs from 2003/04 to 2006/07. Also, declines in ED SRB rates (all ages) were observed in Ireland between 2003 and 2006 and thought to reflect effective interventions for reducing the risk of repeat events. However, subsequent hospital admissions were not considered. Coinciding with the economic recession, in Ireland there were successive 10% increases in ED SRB rates for males in 2007 and 2008, reducing sex differences.37 Also, in December 2006, the US FDA extended their 2003 warnings.38 Taken together, we hypothesize that ED SRB rates declined in youth prior to 2006, but not thereafter, owing to renewed warnings and the economic recession. However, this possibility has yet to be investigated in Canadian boys and girls.

Accordingly, we examined ED SRB rates in Ontario between 2002 and 2010, in boys and girls. Ontario is advantageous for studying ED SRB presentations, given near complete coverage of the population and all hospitals submit such ED data. As ED SRB rates in youth are positively associated with age, inversely related to neighbourhood income, and higher in rural areas,39 we adjusted the rates for yearly variations in these factors. To better characterize trends, we examined the nature of the incident (index) presentations over time in terms of the method(s) used and events occurring before and after the index event. More specifically, we examined the proportions who presented to hospital with a mental illness in the year before and at the time of the index event; were subsequently admitted (for any reason); and had a repeat ED SRB presentation in the following year.

Method

Study Design and Setting

We studied the incidence and nature of ED SRB presentations over time in Ontario. All youth (aged 12 to 17 years) living in Ontario from April 1, 2002, to March 31, 2011 (that is, from FY 2002/03 to FY 2010/11), identified in the RPDB formed the underlying cohort (n = 2 502 017). Coverage of youth in the RPDB is near complete owing to universal medical insurance.40 Youth with an initial ED SRB (index) event (described below) during this time frame were identified in the cohort. Youth who died at the time of the index event (n < 6) were excluded from the cohort. Youth with an index event (n = 15 739) were then followed 1-year forward in time to identify a repeat ED SRB event. Youth who died or moved out of the province during follow-up (n = 266) were excluded from further follow-up. For ease, the term sex is used with the caveat that SRB have social and biological determinants and dichotomous measures are limited.41 Data access was granted through the ICES. Our study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of St Michael’s Hospital.

Measures

Social and Demographic Factors

Age and sex were drawn from the RPDB. Community size and neighbourhood income quintile were created using a person’s residential postal code in each year and the Statistics Canada postal code conversion file.42 For both measures, residential characteristics are determined by where a person lives, that is, his or her dissemination area.42 Community size was defined as 1 500 000 or more; 500 000 to 1 499 999; 100 000 to 1 499 999; 10 000 to 99 999; or 10 000 or less (rural); or missing. Neighbourhood income quintile was calculated for each dissemination area according to the mean income per person equivalent (household income, adjusted for household size). Then the dissemination areas were ranked, within cities, towns, or rural or small town areas, and the populations of each divided into approximate one-fifths to create income quintiles.

The SRB Index Event

The index SRB event was defined according to self-inflicted poisoning or injury code(s) in any ED diagnostic field in the NACRS.43,44 The following ICD-10-CA codes were used: X60 to X84.

The Nature of the SRB Index Event

The nature of the SRB index event was described according to the method(s) used and specific events occurring in the year before and afterwards. SRB method was defined according to the ICD-10-CA code(s) as poisoning only (X60 to X69); cut or pierce only (X78) or other only (X70 to X77; X79 to X84); or multiple (more than one of these methods).45 Events before or after the SRB index event were identified as past and current hospital presentations with mental illness. Among youth with an index event, we identified these presentations according to ED and (or) hospital inpatient stay records. A past presentation was identified in the year before the index event. A current presentation was identified at the time of the index SRB ED presentation and (or) in a subsequent inpatient stay. For ED presentations, mental illness was defined according to ICD-9 230 to 319 or ICD-10 F00 to F99 codes in any NACRS diagnostic field. An inpatient stay with mental illness was defined using the Canadian Institute for Health Information DAD46,47 and the OMHRS48 and defined as: a most responsible diagnosis of mental disorder (ICD-10-CA F00 to F99) and (or) main patient service of psychiatry or pediatric psychiatry in the DAD or an inpatient stay (in an adult psychiatric bed) captured in OMHRS.

An inpatient admission (for any reason) subsequent to the index event was identified within the DAD or OMHRS.

Repetition was defined as at least 1 repeat ED presentation for SRB in the year following the index SRB event.

Analysis

We calculated and graphed person time incidence rates of ED SRB presentations and 95% confidence intervals by FY (excluding subsequent repeat events) in girls and boys. Negative binomial regression was then used to test whether rates declined over time but then either became level or increased. In particular, we compared rates in time 2: FYs 2006/07 to 2010/11 to time 1: FYs 2002/03 to 2005/06 and then the yearly trend, between FYs 2006/07 to 2010/11 adjusted for age, neighbourhood income, or community size in boys and girls. Unadjusted and adjusted rates, RRs, and 95% confidence intervals were estimated for boys and girls. Among those with an index event, we described the nature of these events with proportions (and corresponding 95% confidence intervals) of girls and boys who used specific methods and events occurring before or after the index event over time.

Results

ED SRB Incidence Rates Over Time

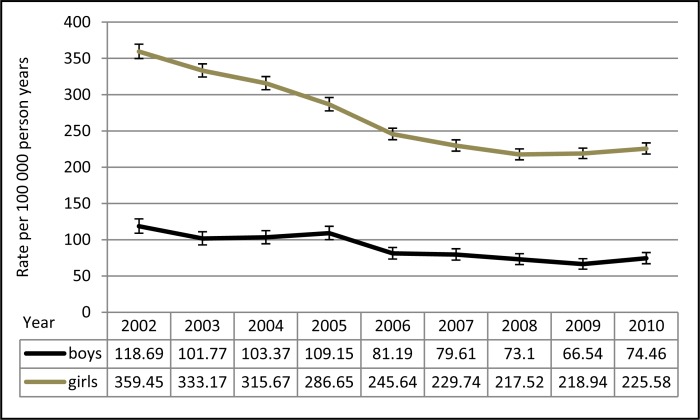

Figure 1 shows these rates over time in boys and girls. Overall, the rates decreased over time in both boys and girls. Further, the rates seem parallel—that is, neither group seemed to be experiencing a greater decrease over time than the other. As such, the rates remain higher in girls in every year studied.

Figure 1.

The incidence rates of SRBs in girls and boys over time

The results from modelling the rates over time in girls and boys are shown in Table 1. The RRs indicated that across all models rates were about 30% lower in time 2, compared with time 1. However, (not shown in Table 1) when we examined the yearly trend between FYs 2006/07 and 2010/11, there was little change in the rates in girls or boys. In each of the analyses, adjustments for age, community size, or neighbourhood income had minimal impact on the results.

Table 1.

The incidence ratesa of SRBs in time 2 (2006–2010), compared with time 1 (2002–2005), in girls and boys

| Time 2, compared with Time 1 | Girls

|

Boys

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 2: Rate per 100 000 person years (95% CI) | Time 1: Rate per 100 000 person years (95% CI) | Time 2, compared with time 1 RR (95% CI) | Time 2: Rate per 100 000 person years (95% CI) | Time 1: Rate per 100 000 person years (95% CI) | Time 2, compared with time 1 RR (95% CI) | |

|

n = 9 years

|

||||||

| Model 1: time 2, compared with time 1 | 227.5 (214.7–241.0) | 323.7 (304.0–344.6) | 0.70 (0.65–0.77) | 75.0 (70.7–79.6) | 108.2 (101.8–115.0) | 0.69 (0.64–0.76) |

|

n = 54 (9 year by 6 age groups)

|

||||||

| Model 2: time 2, compared with time 1 (Age-adjusted) | 213.8 (191.2–239.1) | 312.4 (276.1–353.5) | 0.68 (0.58–0.81) | 66.5 (61.0–72.4) | 96.5 (88.4–105.3) | 0.69 (0.61–0.78) |

|

n = 45 (9 years by 5 community size groups)

|

||||||

| Model 3b: time 2, compared with time 1 (Community size-adjusted) | 205.9 (195.7–216.7) | 288.7 (273.6–304.6) | 0.71 (0.67–0.76) | 66.4 (60.7–72.8) | 93.5 (85.0–102.9) | 0.71 (0.63–0.80) |

|

n = 45 (9 year by 5 income groups)

|

||||||

| Model 4c: time 2, compared with time 1 (Income-adjusted) | 216.3 (207.1–225.9) | 307.9 (294.4–322.0) | 0.70 (0.67–0.74) | 70.5 (65.6–75.9) | 100.2 (93.5–107.3) | 0.7 (0.65–0.77) |

Age = 12 to 17 years; community size: <10 000 to 1.45 million (compared with ≥1.5 million); income = neighbourhood income quintiles 1 to 4, compared with 5, high

Rates are the means estimated from the regression model with corresponding 95% CI. The means estimated for the crude rates in model 1 were identical or near identical to those estimated in models 2, 3, and 4.

n ≤ 5 missing on community size, only in girls in year 2003 (excluded from analyses)

Missing data on income quintile in each year (excluded from analyses). In girls, maximum missing in any year was n = 18, total missing across all years was n = 71. In boys, maximum missing in any year was n = 6, otherwise missing suppressed as ≤5; thus maximum missing across all years was n = 46.

Nature of the SRB Presentations Over Time

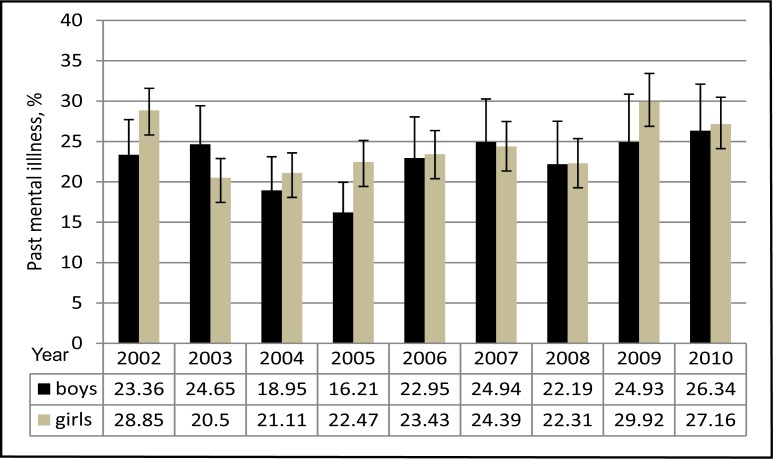

Hospital Presentations With Mental Illness

Among boys and girls with an index event, Figure 2 depicts youth presenting to hospital in the past year with mental illness and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Overall, 24.3% of girls and 22.4% boys presented with past mental illness. The pattern of these presentations over time was similar to that observed in the ED SRB incidence rates. In girls, between FYs 2002/03 and 2005/06, in each year the proportion is lower than in the previous year and these 95% confidence intervals do not overlap with those in FY 2002/03. However, this changes in FY 2006/07. Thereafter, the proportions no longer decreased and are comparable with FY 2002/03. In boys, we found a similar pattern; however, all the 95% confidence intervals overlap. At the time of the index event, in both girls and boys, almost all presented with mental illness (that is, about 90%) and this did not vary considerably over time.

Figure 2.

Hospital presentations with mental illness among boys and girls in the year before their index presentation to the ED for SRB

ED SRB Method

The bulk of index events were due to self-poisoning (74.1% in girls and 62.2% in boys). In girls, the next most common method was cut or pierce injuries (22.3%) and in boys, cut or pierce injuries (22.0%) and other methods (16.8%). Other methods were infrequent in girls (4.7%) and multiple methods, rare in both sexes. In girls, the proportion with self-poisonings decreased between FY 2002/03 and 2005/06 (from 78.5% [95% CI 74.2% to 82.9%] to 67.7% [95% CI 63.4% to 72.2%]). Thereafter, the proportion numerically increased reaching 75.4% (95% CI 70.3% to 80.8%) in 2010/11. The opposite pattern was observed in cut or pierce injuries which increased between FYs 2002/03 and 2005/06 from 18.5% (95% CI 16.5% to 20.7%) to 27.2% (95% CI 24.5% to 30.2%) but then numerically decreased to 22.4% (95% CI 19.6% to 25.4%) in 2010/11. In contrast to girls, the proportion of boys with self-poisoning or cut or pierce injuries remained fairly constant over time. However, other injuries decreased between FYs 2002/03 and 2010/11 from 21.8% (95% CI 18.1% to 26.0%) to 13.2% (95% CI 9.7% to 17.4%).

Subsequent Events

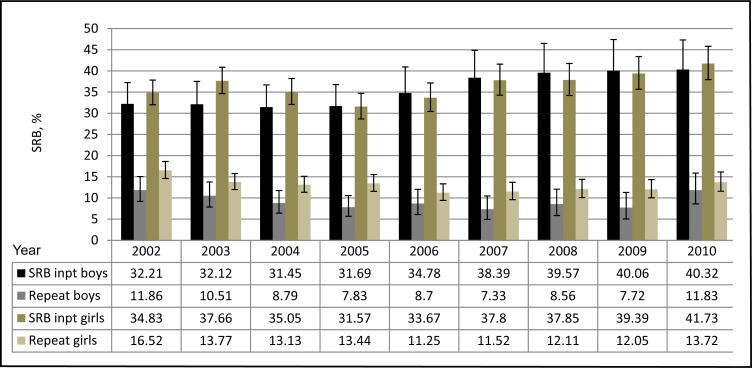

Figure 3 shows the proportion with a subsequent inpatient admission and (or) a repeat ED SRB presentation and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Among girls, the proportion admitted to hospital increased between FYs 2005/06 and 2010/11, from a low of 31.6% to a high of 41.7%, a proportional increase of almost one-third. The proportion of girls with a repeat event declined from 16.5% in FY 2002/03 to around 11% to 12% between FYs 2006/07 and 2009/10, again by about one-third. Among boys, we found that after the index event, the proportion of boys admitted to hospital also (numerically) increased over time between FYs 2005/06 and 2010/11 (from 31.7% to 40.3%) by about one-third. However, the 95% confidence intervals overlapped. Similar to girls, the proportion of boys who had a repeat event within 1 year after the index event (numerically) decreased between FYs 2002/03 and 2009/10 by about one-third; but the 95% confidence intervals overlapped.

Figure 3.

Events subsequent to the index ED SRB event: hospital inpatient (inpt) stay and repeat ED SRB presentation, over time

Discussion

Our study confirmed our hypothesis that ED SRB presentation rates decreased by 30% in boys and girls to FY 2006, but not in later years. These findings were not altered by yearly variations in the underlying population structure (age, community size, or neighbourhood income). When we examined the nature of the index ED SRB presentations, we found this pattern was most evident in girls who self-poisoned and was also apparent in girls’ presentations to hospital with mental illness in the preceding year. Within 1 year of the index event, the proportion of girls who had a repeat ED SRB also declined by about one-third, but beyond FYs 2005/06 to 2009/10. However, the proportion admitted subsequent to the index event increased beyond FYs 2005/06 to 2010/11 by about one-third. In boys, their methods differed somewhat from girls and over time; still, their pattern of presentations to hospital with mental illness and SRB repetition over time were similar to girls, but estimated with greater variability. Overall, it is reassuring that ED SRB rates declined over time in girls and boys from FYs 2002/03 to 2006/07 and were robust to the population structures noted. However, the lack of a continued decline in the rates, along with an increase in the proportion subsequently admitted, merit consideration, along with the study limitations.

Limitations

We did not have measures of provider- or organization-level integration between community and hospital-based services. We are unable to discern whether such mechanisms may have influenced ED SRB rates over time. Further, we did not examine whether the 30% reduction in ED SRB rates prior to FY 2006/07 was offset by these youth presenting to the ED with mental illness rather than SRB. This possibility seems less credible, though, given that in the year before the index event, the direction of the trends in their hospital presentations with mental illness were in the same (not opposite) direction as their future index ED SRB presentations. Like previous studies, our measures of SRB do not enable us to identify the intent of these behaviours. This information is not (yet) collected in NACRS or in the ICD classification system. We studied presentations to the ED for SRB as most who present to the ED with SRB are not admitted. Still, these presentations do not represent SRB in the general population of youth. Thus it is unclear whether the time trends in our study apply to youth with SRB in the general population. The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey conducted in the United States reported the prevalence of youth with a past-year suicide attempt that required treatment from a doctor or nurse decreased between 1995 and 2009 (from 2.8% to 1.9%) with no change between 2009 and 2011.49

Interpretation of Findings

Below we identify some possible explanations of why ED SRB rates declined prior to FY 2006/07, but not thereafter, along with an increase in the proportion subsequently admitted. Reductions in youth suicide rates have been observed in Canada over time, especially in male youth.3,34 Perhaps the same factors influencing suicide rates over time (more boys) are relevant to SRB, including suicide attempts (more girls). Over the past decade, there has been a concerted effort by numerous organizations to reduce stigma about mental illness and seeking help directed to the general public and youth.50–54 Given mental disorders are major determinants of SRBs55,56 to the extent that youth sought and benefited from treatment, the incidence and repetition of SRB may have been prevented. Possibly related, reductions in the consumption of alcohol and its misuse among youth may have contributed to declines in these behaviours.34

Reasons why ED SRB rates stopped declining after FY 2006/07 may be Ontario-specific and (or) reflect broader influences. For example, in Ontario note that in March 2006, regions or Local Health Introduction Networks were introduced to better plan, fund, and integrate health services locally.57 Local Health Introduction Networks may have helped to offset potential increases in ED SRB rates owing to broader influences, that is, the effects of the regulatory warnings and (or) economic recession. Regarding the warnings, we wonder whether there was a lagged effect in ED SRB rates. That is, some youth may have stopped (or tapered) treatment between FYs 2004/05 and 2006/07, contributing to future index ED SRB presentations (with proportionately more admissions, but fewer ED SRB repetitions). Prior work and our study indicate that a fair portion of youth who present to the ED with SRB received some form of medical care in the past 2 years.24 Further, the added FDA warnings in 2006 may have influenced physicians and patients. Lastly, the recession may have contributed to preventing a continued decline in ED SRB rates after 2006 in Ontario youth. The (all ages) increases in ED SRB rates found in Ireland37 and in suicide rates documented in England,58 other European countries59 and US adults60 are thought to be recession-related. While the mechanisms for youth are unclear, stress about income loss and any added expense of treatment likely burdened youth and their families.

Conclusions

In Ontario, presentations to the ED for SRB in youth decreased by 30% in boys and girls from FYs 2002/03 to 2006/07 but then stabilized up to and including FY 2010/11. This pattern was not altered by yearly variations in the underlying population structure (age, community size, or neighbourhood income). While the declining ED SRB rates from FYs 2002/03 to 2006/07 are encouraging, it will be important to monitor and evaluate the lack of decline thereafter along with increases in subsequent hospital admissions in boys and girls, in relation to the underlying population and etiologic factors, including the delivery and receipt of supports and services.

Acknowledgments

The data were accessed through the ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. This project was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (SEC117128).

Abbreviations

- AD

antidepressant

- CA

Canadian enhancement

- DAD

Discharge Abstract Database

- ED

emergency department

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FY

fiscal year

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- ICES

Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

- NACRS

National Ambulatory Care Reporting System

- OMHRS

Ontario Mental Health Reporting System

- RPDB

Registered Persons Data Base

- RR

rate ratio

- SRB

suicide-related behaviour

References

- 1.Silverman M, Berman A, Sanddal N, et al. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part I: background, rationale and methodology. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(3):248–263. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman M, Berman A, Sanddal N, et al. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: suicide-related ideations, communications and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(3):264–277. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner R, McFaull S. Suicide among children and adolescents in Canada: trends and sex differences, 1980–2008. CMAJ. 2012;184(9):1029–1034. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawton K, Zahl D, Weatherall R. Suicide following deliberate self-harm: long-term follow-up of patietns who presented a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:537–542. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):297–303. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, et al. Premature death after self-harm: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1568–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193–199. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reith DM, Whyte I, Carter G, et al. Adolescent self-poisoning: a cohort study of subsequent suicide and premature deaths. Crisis. 2003;24(2):79–84. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.24.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K, Harriss L. Deliberate self-harm in young people: characteristics and subsequent mortality in a 20-year cohort of patients presenting to hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1574–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawton K, Saunders K, O’Connor R. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler R, Berglund P, Borges G, et al. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293:2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colman I, Yiannakoulias N, Schopflocher D, et al. Population-based study of medically treated self-inflicted injuries. CJEM. 2004;6(5):313–320. doi: 10.1017/s148180350000957x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes A, Bethell J, Jaakkimainen L, et al. The impact of rural residence on medically serious medicinal self-poisonings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(6):552–560. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canadian Insitute for Health Information (CIHI) Health indicators. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasserman D, Cheng Q, Jiang G. Global suicide rates among young people aged 15–19. World Psychiatry. 2005;4:114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitman A, Krysinka K, Osborn D, et al. Suicide in young men. Lancet. 2012;379:2383–2392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics Canada . Deaths and mortality rate, by selected grouped causes and sex, Canada, provinces and territories, 2009 CANSIM table 1020552 [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2009. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canetto S. Women and suicidal behavior: a cultural analysis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(2):259–266. doi: 10.1037/a0013973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beautrais AL. Gender issues in youth suicidal behaviour. Emerg Med. 2002;14:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes A, Khan S, Boyle M, et al. Sex differences in suicides among children and youth—the potential impact of help-seeking behaviour. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(5):274–282. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhodes A, Khan S, Boyle M, et al. Sex differences in suicides among children and youth—the potential impact of misclassification. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(3):213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF03403815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodes A, Boyle M, Bethell J, et al. Child maltreatment and onset of emergency department presentations for suicide-related behaviors. Child Abuse Neg. 2012;36:542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes A, Boyle M, Bethell J, et al. Child maltreatment and repeat presentations to the emergency department for suicide-related behaviors. Child Abuse Neg. 2012;37(2–3):139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newton A, Rosychuk R, Dong K, et al. Emergency health care use and follow-up among sociodemographic groups of children who visit emergency departments for mental health crises. CMAJ. 2013;184(12):665–674. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton A, Hamm M, Bethell J, et al. Pediatric suicide-related presentations: a systematic review of mental health care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asarnow J, Baraff L, Berk M, et al. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1303–1309. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ougrin D, Zundel T, Ng A, et al. Trial of therapeutic assessment in London: randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus standard psychosocial assessment in adolescents presenting with self-harm. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:148–153. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.188755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grupp-Phelan J, McGuire L, Husky M, et al. A randomized controlled trial to engage in care of adolescent emergency department patients with mental health problems that increase suicide risk. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(1263):1268. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182767ac8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, et al. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England: 2000–2007. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:493–498. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergen H, Hawton K, Murphy E, et al. Trends in prescribing and self-poisoning in relation to UK regulatory authority warnings against use of SSRI antidepressants in under 18-year olds. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(4):618–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapur N, Cooper J, O’Connor R, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury v attempted suicide: new diagnosis or false dichotomy? Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(326):328. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butler A, Malone K. Attempted suicide v non-suicidal self-injury: behaviour, syndrome or diagnosis? Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:324–325. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.113506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhodes A, Skinner R, McFaull S, et al. Canada wide effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescribing and suicide rates in boys and girls. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(11):640–645. doi: 10.1177/070674371305801110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz L, Kozyrsky A, Prior H, et al. Effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescription rates, use of health services and outcomes among children, adolescents and young adults. CMAJ. 2008;178(8):1005–1011. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newton A, Ali S, Johnson D, et al. A 4-year review of pediatric mental health emergencies in Alberta. CJEM. 2009;11(5):447–454. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500011647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perry I, Corcoran P, Fitzgerald A, et al. The incidence and repetition of hospital-treated deliberate self-harm: findings from the world’s first national registry. PLoS Med. 2012;7(2):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibbons R, Brown C, Hur K, et al. Early evidence on the effects of regulator’s suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1356–1363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bethell J, Bondy S, Lou W, et al. Emergency department presentations for self-harm among Ontario youth. Can J Public Health. 2013;104:124–130. doi: 10.1007/BF03405675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iron K, Zagorski B, Sykora K, et al. ICES investigative report. Toronto (ON): Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2008. Living and dying in Ontario: an opportunity for improved health information. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson J, Repta R. Sex and gender: beyond the binaries. In: Oliffe J, Greaves L, editors. Designing and conducting gender, sex and health research. Los Angeles (CA): Sage; 2012. pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkins R. PCCF+ version 5E user’s guide (geocodes/PCCF) automated geographic coding based on the Statistics Canada postal code conversion files. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) National ambulatory care reporting system [Internet] Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2012. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/internet/en/document/types+of+care/hospital+care/emergency+care/services_nacrs. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) CIHI data quality study of Ontario emergency department visits for 2004–2005 volume II of IV—main study findings. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawton K, Harriss L. Deliberate self-harm by under-15-year-olds: characteristics, trends and outcome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):441–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Acute care [Internet] Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2012. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/internet/EN/TabbedContent/types+of+care/hospital+care/acute+care/cihi016785. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: a validation study. Toronto (ON): Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) About OMHRS [Internet] Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2012. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.cihi.ca/cihi-ext-portal/internet/en/document/types+of+care/specialized+services/mental+health+and+addictions/services_omhrs_about. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behaviors National YRBS: 1991–2011 [Internet] Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2013. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/us_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teen Mental Health . Teen mental health [web site] Halifax (NS): IWK Health Centre—Maritime Psychiatry; 2013. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.teenmentalhealth.org. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health . Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health [website] Ottawa (ON): Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health; 2013. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.excellenceforchildandyouth.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) The Mental Health Commission of Canada [web site] Ottawa (ON): MHCC; 2013. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention . Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention [web site] Winnipeg (MB): Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention; 2013. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.suicideprevention.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Government of Ontario . Open minds, healthy minds [Internet] Toronto (ON): Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2011. [cited 2013 Jun 18] Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/mental_health2011/mentalhealth_rep2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bridge J, Goldstein T, Brent D. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Marcus SC, et al. Emergency treatment of young people following deliberate self-harm. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1122–1128. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Government of Ontario . Ontario’s local health integration networks 2013 [Internet] Toronto (ON): Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2013. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://www.lhins.on.ca/home.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A, et al. Suicides associated with the 2008–10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Vogli R, Marmot M, Stuckler D. Strong evidence that the economic crisis caused a rise in suicides in Europe: the need for social protection. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(4):298. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-202112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sullivan E, Annest J, Luo F, et al. Suicide among adults aged 35–64 years—United States, 1999–2010. MMWR. 2013;62(17):321–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]