Abstract

Objective:

In North America and internationally, efforts have been made to reduce the gaps between knowledge of psychosocial evidence-based practices (EBPs) and the delivery of such services in routine mental health practice. Part 2 of this review identifies key issues for stakeholders to consider when implementing comprehensive psychosocial EBPs for people with severe mental illness (SMI).

Method:

A rapid review of the literature was conducted. Searches were carried out in MEDLINE and PsycINFO for reports published between 1990 and 2012 using key words related to SMI, and psychosocial practices and implementation. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) was used to structure findings according to key domains and constructs known to influence the implementation process.

Results:

The CFIR allowed us to identify 17 issues reflecting more than 30 constructs of the framework that were viewed as influential to the process of implementing evidence-based psychosocial interventions for people with SMI. Issues arising at different levels of influence (intervention, individual, organizational, and system) and at all phases of the implementation process (planning, engagement, execution, and evaluation) were found to play important roles in implementation.

Conclusion:

The issues identified in this review should be taken into consideration by stakeholders when engaging in efforts to promote uptake of new psychosocial EBPs and to widen the range of effective psychosocial services available in routine mental health care.

Keywords: severe mental illness, substance use disorders, evidence-based practice, psychosocial treatment, implementation

Abstract

Objectif :

En Amérique du Nord et sur la scène internationale, il y a eu des efforts pour réduire l’écart entre la connaissance des pratiques psychosociales fondées sur des données probantes (PFDP) et la prestation de ces services dans la pratique de santé mentale de routine. La 2e partie de cette revue identifie les principaux enjeux dont doivent tenir compte les intervenants qui mettent en œuvre des PFDP psychosociales complètes pour les personnes souffrant de maladie mentale grave (MMG).

Méthode :

Une revue rapide de la littérature a été menée. Des recherches ont été effectuées dans MEDLINE et PsycINFO pour trouver les études publiées entre 1990 et 2012 à l’aide des mots clés liés à MMG, pratiques psychosociales, et mise en œuvre. Le cadre consolidé pour la recherche sur la mise en œuvre (CFIR) a été utilisé pour structurer les résultats selon les principaux domaines et construits reconnus influencer le processus de mise en œuvre.

Résultats :

Le CFIR nous a permis d’identifier 17 enjeux reflétant plus de 30 construits du cadre qui ont été jugés influencer le processus de mise en œuvre des interventions psychosociales fondées sur des données probantes pour les personnes souffrant de MMG. Les questions soulevées à différents niveaux d’influence (intervention, individuelle, organisationnelle, et systémique) et à toutes les phases du processus de mise en œuvre (planification, engagement, exécution, et évaluation) se sont révélées jouer un rôle important dans la mise en œuvre.

Conclusion :

Les questions identifiées dans cette revue doivent être prises en considération par les intervenants lorsqu’ils déploient des efforts pour promouvoir l’adoption de nouvelles PFDP psychosociales et l’expansion de la gamme des services psychosociaux offerts dans les soins de santé mentale réguliers.

In most industrialized countries, gaps exist between knowledge of effective psychosocial practices and the application of these practices in routine mental health services.1–4 However, such gaps are difficult to close, and reports suggest that translating knowledge into practice can take years and even decades.5,6 As such, mental health authorities and service providers are increasingly seeking to understand the strategies and factors that contribute to implementation success or failure in an effort to accelerate the change process.

This review aimed to take stock of the evidence related to the implementation of psychosocial EBPs for people with SMI and to support future efforts to implement a broader range of services than is currently available in most communities. Part 1 of our review7 described more than a dozen international, national, and regional initiatives carried out since 1990 that aimed to implement multiple psychosocial EBPs (Table 1) and identified the key implementation strategies used to promote uptake of these EBPs. In part 2, we identify critical issues for stakeholders to consider when embarking on a process of implementing a broader array of psychosocial EBPs in their own settings.

Table 1.

Description of major initiatives aiming to implement multiple psychosocial EBPs for people with SMI

| Initiative | Description and objectives | References |

|---|---|---|

| National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project United States (8 states): 1999–2006 |

Multi-site demonstration project aiming to support the implementation of 5 psychosocial interventions (ACT, family psychoeducation, illness management and recovery, integrated dual disorders treatment, and supported employment) in community mental health settings. | Bond et al16

Torrey et al50,66 Mueser et al55 |

| Enhancing Quality-of-care In Psychosis United States (4 VHA service regions): 2001–ongoing |

Project emerging from the VHA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, which aimed to promote the delivery of guideline-concordant care (including family psychoeducation, weight management services, and supported employment) to veterans with schizophrenia. | Brown et al27 |

| VHA Quality Improvement initiatives United States (across the United States): 2004–ongoing | Broad quality improvement initiatives led by the VHA to transform mental health services provided to veterans and provide a full continuum of recovery-oriented and psychosocial rehabilitation services. | McHugh and Barlow43

Goldberg and Resnick78 |

| NIDA–SAMHSA Blending Initiative United States (across the United States): 2001–ongoing | Partnership between NIDA and SAMHSA aiming to accelerate implementation of research findings from NIDA-sponsored treatment studies into mental health and substance use services. | Martino et al41

Condon et al79 |

| Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder United States (15 institutions across the United States): 1998–2005 | A national, longitudinal infrastructure for clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of 4 psychosocial EBPs (CBT, family focused therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and patient education with illness self-management) for people with various presentations of bipolar disorder. | Miklowitz and Otto22

Sachs et al64 Bowden et al80 |

| Mental Health Treatment Study United States (19 states): 2006–2010 | Large study that aimed to evaluate and improve employment policies and services for people with SMI receiving Social Security Disability Insurance. | Frey et al28,81 |

| Housing First—At Home/Chez soi United States (across the United States): 1993–ongoing Canada (5 cities): 2009–ongoing |

Gradual dissemination of supported housing intervention aiming to provide housing and treatment services to homeless people with SMI. At Home/Chez soi project conducted in Canada, the largest pragmatic trial of the Housing First model to date. | Pathways to Housing Inc32

Goering et al82 |

| Optimal Treatment Project International: 1994–mid-2000s | An international, multi-site pragmatic trial evaluating the effectiveness of evidence-based biomedical and psychosocial treatments (including family psychoeducation, stress management training, ACT, social skills training, CBT, and early intervention programs) for people with psychosis. | Falloon56

Falloon et al83 |

| DH mental health reforms United Kingdom (across England): late 1990s–ongoing |

Mental health system reforms initiated by the British government and overseen by the DH. Reforms included implementation of several psychosocial supports for people with SMI (early intervention programs for psychosis, assertive outreach, and crisis services). | UK DH63,84,85

Joseph and Birchwood86 |

| Reforms to psychiatric services in Israel Israel: 2000–ongoing |

Legislation-based reforms broadening access to evidence-based psychiatric rehabilitation services carried out by the Israeli government and initiated by a multi-stakeholder group of mental health activists. | Roe et al61,87 |

CBT = cognitive-behavioural therapy; DH = Department of Health; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; VHA = Veterans Health Administration

Method

Search and Selection Process

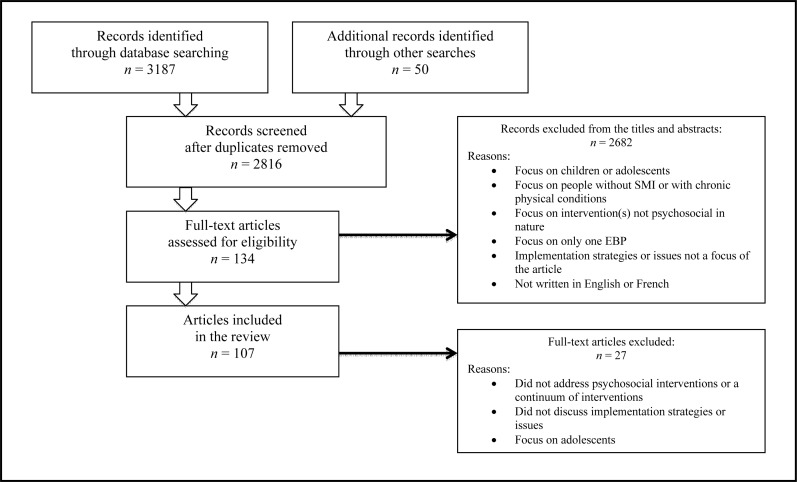

Full details of the rapid review methods are available in Menear and Briand.7 Briefly, we carried out comprehensive searches in MEDLINE and PsycINFO (January 1990 to March 2012) for English- and French-language literature that included terms for SMI, and psychosocial interventions and implementation. All sources combined, our search yielded 2816 reports. After screening (Figure 1), we then extracted data from the 107 selected articles, guided by a conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of articles included in the review

Clinical Implications

During the past 2 decades, the evidence base for a range of psychosocial interventions has grown considerably.

When seeking to implement these interventions, stakeholders must consider a wide range of issues arising at different levels of influence (intervention, individual, organizational, and system) and stages of the implementation process (planning, engagement, execution, and evaluation).

Consideration of the factors that contribute to implementation success or failure is important to reduce gaps in services and ensure the availability of a continuum of effective and sustainable mental health services.

Limitations

The streamlined methodology adopted for this review may have led to some relevant articles being omitted from our analysis.

Consideration of the public policy context of mental health service delivery in the different countries contributing research for the review was limited.

Conceptual Framework

The CFIR was recently developed by Damschroder et al8 to provide an overarching typology of key domains known to influence the implementation process. These 5 domains are: characteristics of the intervention, the individuals involved in the intervention, the organization (inner setting), the outer setting, and the implementation process. The theoretical constructs identified from published implementation theories were identified for each domain, for a total of 39 constructs (eTable 2).

Results

In the sections that follow, we present some of the main implementation issues that were identified by authors across the review studies. When it was judged appropriate, constructs from the CFIR were discussed in tandem.

Characteristics of the Intervention

Evidence Strength and Quality

Authors have long argued that a main barrier to the uptake of psychosocial interventions was probably the evidence itself.9–12 While the evidence base for many interventions has grown considerably during the past decades, even now some psychosocial practices are recognized as having stronger empirical support than others, and there is still much to learn about intervention mechanisms and outcomes for different patient populations.9,10,13 Capturing the critical ingredients and mechanisms of psychosocial interventions is complex work, but it is a necessary step in the process of implementing and evaluating these interventions.13–15

Complexity

The multidimensional nature of interventions influences rates of uptake, with interventions requiring more skill to deliver or involving more professionals or service components being more difficult to implement faithfully.16–20 In the NEBPP, difficulties in implementing integrated treatment for mental health and substance use disorders was directly linked to the complexity of the intervention and its implementation.16 As with other EBPs (for example, family psychoeducation, illness management, and recovery), integrated mental health and substance use treatment interventions require a high degree of skill development and behavioural changes on the part of individual practitioners along with organizational and structural service changes. In contrast, interventions relying more heavily on organizational and structural service modifications (for example, supported employment and ACT) were more often implemented successfully.16 Managing the complexity of implementation may be a particular challenge when seeking to implement multiple psychosocial EBPs, though this may be achieved through sequential (compared with simultaneous) implementation of EBPs21 or through the introduction of new practices while simultaneously enhancing fidelity and quality of existing psychosocial services.22

Adaptability and Relative Advantage

Decisions on which services to offer in a particular setting result from deliberation on the evidence supporting interventions and on the needs of service users, ethical and legal issues, local culture, and the preferences and values of the individuals or groups involved.10,23 While some authors argue fervently in favour of high-fidelity implementation,10,23 others defend the notion that adaptations to local context or populations are acceptable as long as interventions and outcomes are evaluated.24–27 If providers perceive interventions to be too rigid or fail to appreciate their potential advantages, they are unlikely to be adopted.9,23,25

Costs

The cost-effectiveness of psychosocial EBPs was considered an important issue by several authors.12,19,21,28–33 Community-based EBPs are widely considered more cost-effective than traditional services over the long term,12,33 especially when they generate cost reductions in other areas (for example, inpatient services).29,30 That said, some psychosocial EBPs are clearly more costly to implement than others, and high start-up costs for EBPs (for example, ACT) can act as a barrier to uptake.21,34

Characteristics of the Individuals Involved in the Interventions

Knowledge, Competence, and Self-Efficacy

To take ownership of a practice and progressively develop a positive attitude toward change, service providers need information about EBPs, and they need support in the form of training and ongoing supervision.13,19,35–42 Training allows providers to evaluate their level of comfort with new psychosocial practices and fosters commitment to change.40 It also allows them to develop practical expertise and the skills needed to deliver EBPs and to believe in their own abilities to meet new challenges. Many psychosocial EBPs require providers possess sophisticated skills, and without proper training many providers feel underprepared to adopt these practices.2,17,18,43 Successful training requires a balance of didactic (for example, written materials and workshops) and interactive (for example, case review meetings, supervision, audit, or self-appraisal) training approaches.42,43

Attitude and Individual Stage of Change

Though pressures to adopt new or unfamiliar practices can be anxiety-provoking, change is facilitated when providers can tolerate some uncertainty and when positive attitudes toward change are nurtured and encouraged.3,18 Resistance to change is a theme often highlighted in the implementation literature and was noted as a key barrier in many of the articles retrieved in this review. Resistance may stem from misalignments between provider philosophies and those underpinning new practices, negative perceptions of interventions, or pressures to develop new habits or skills.17,19 Further, busy work schedules and a lack of time to integrate new knowledge can discourage openness to change and the adoption of new, complex EBPs.19,36,37,44,45 To overcome such obstacles, leaders within organizations must establish supportive practice contexts, engage and negotiate with team members, and provide them with time to learn and experiment with new practices.3 Failure to put time and resources into such actions often leads providers to continue doing what is familiar and comfortable to them (inertia) even though more effective practices may exist.15

Personal Attributes—Values and Professional Identity

Attributes, such as providers’ values and professional identity, play important roles in the implementation of EBPs.10,18,23,33 Some providers may defend more humanist positions and display skepticism toward new practices or standardization efforts seemingly insensitive to sociodemographic or clinical differences among service users.10,23,44 Implementation efforts may arouse fears of losing professional autonomy,23,46 and implementation success may depend on professionals revisiting their self-image and surrendering some of their autonomy.18

Characteristics of the Organization (Inner Setting)

Organizational Structure and Workforce

The fragmentation of services, frequent personnel turnover, and shortages of highly trained specialist therapists that characterize many mental health systems hinder the implementation of needed psychosocial services and the development of advanced professional skills.19,29,42,44,45,47,48 Organizations’ ability to train professionals and retain qualified personnel is critical for successful implementation efforts and in the delivery of high-quality services.28,49 Large organizations with a larger pool of professionals are often able to replace personnel that leave with people with new skills and knowledge of best practices.15 However, larger organizations also tend to have organizational structures that are more rigid, which may impede innovation.3 Investing in the organization’s workforce and retaining qualified personnel is thus key to implementing comprehensive psychosocial services.

Organizational Culture

Organizations must feature supportive structural characteristics and foster a culture that facilitates the emergence and maintenance of EBPs.16,24,50,51 Providers may not fully appreciate the benefits of an EBP if the basic philosophy, values, and norms espoused in their work environment encourage a different service approach.20,37,50,52 A major finding of the NEBPP was that many implementation sites were not naturally predisposed to integrating science-based interventions or to practising according to recovery philosophies, a cultural reality that needed to be addressed prior to the actual implementation of EBPs.50

Implementation Climate

Similar to organizational culture, an organization may exhibit a climate that, at a given point in time and for various reasons, is favourable to the adoption of psychosocial EBPs. In initiatives such as the NEBPP and the Enhancing Quality-of-care In Psychosis Project, researchers purposely aimed to influence implementation climates by securing support for initiatives from key stakeholders and by generating enthusiasm for EBPs through project kick-off events with participating sites.17,27 Initial implementation of EBPs is also facilitated by organizational climates that promote learning and are open to change, which can be made possible through training or knowledge-sharing opportunities, systems of rewards for new practices, and time protected for reflexive thinking and experimenting with new practices.13,15,35,40,44 Organizations should also foresee a consolidation phase when implementing EBPs, that is, ensuring sustainability of newly introduced EBPs by formalizing mechanisms for supervising staff, monitoring service costs and identifying quality issues or problems, and ensuring that services continue to meet client needs.3

Readiness for Implementation

Several factors seem to make organizations more ready to implement psychosocial EBPs, such as strong leadership and an organizational commitment to change practices,13,16,36,37,48,50 the availability of adequate resources,2,15,17,21,40,46,53–55 as well as access to experts willing to support implementation and share their expertise.16,28,32,56 When organizational leaders make practice change a clear priority, they can mobilize their personnel and foster a climate that overcomes implementation obstacles. This was apparent in the NEBPP, where sites with engaged leadership found ways to ensure they achieved high fidelity in the EBPs being implemented (for example, by hiring staff to fill specific roles, limiting the size of caseloads, organizing team meetings, and revising productivity standards that conflicted with the EBP).16 Strong leadership is even more critical for practices that involve important changes in philosophy, coordination with many stakeholders, or political and financial issues.20,21

There is little doubt that inadequate funding and under-staffed or -skilled programs and services are all key impediments to the implementation of psychosocial EBPs.17,23,29,44,52,57 Lack of funds to pursue professional development and the absence of incentives to promote high-quality services can dampen staff morale and slow the uptake of EBPs.9,13,15,29,44,45 Timely access to people with expertise and perceived legitimacy with EBPs is another key facilitator of change. In the Optimal Treatment Project, the ongoing support and technical assistance of the project leader was identified as a major determinant of success in the implementation of best practices in the treatment of schizophrenia across numerous countries.56

Outer Setting

Mental Health Authority Leadership and Engagement

As with organization-level leadership, leadership exhibited by mental health authorities and policy-makers is widely considered critical to the implementation of psychosocial EBPs.16,17,21,31,47–49,58,59 For instance, in the NEBPP, lack of commitment on behalf of mental health authorities in some states acted as a major barrier to the implementation and sustainability of psychosocial EBPs.18,60 In contrast, support in other states from such authorities took the form of clear policies in favour of psychosocial EBPs, support in training and consultation (for example, through the establishment of technical assistance centres), and implementation of financial incentives and quality-improvement strategies (for example, through licensing and accreditation processes).16,17 When mental health authorities played a lead role in implementation, they established norms for high-quality services, ensured that there were no geographic disparities in services, and acted as influential change agents.21,59

Attitudes and Advocacy by Service Users and Families

While involving service users and their families in psychosocial treatment and service planning has historically been challenging, it is increasingly thought to facilitate the adoption of new practices and to decrease stigma.13,18,44,57 Service users often have particular concerns, such as fears that services they appreciate and consider effective could be discontinued or replaced by unfamiliar services having stronger empirical support.11 Further, advocacy by service users and families has been shown to accelerate the dissemination of EBPs and ensure that new practices correspond to real community needs.11,12 A striking example is the case of psychiatric service reforms in Israel, where consumers, families, and other activists successfully pressured the government to significantly broaden the range of psychosocial EBPs available to people with SMI.61 In the past decade, the number of people receiving psychiatric rehabilitation services in Israel has quadrupled, and the budget for these services has increased 8-fold.61 Clearly, more collaborative approaches to implementation that are driven by the voices of consumers and families have great potential to increase access to psychosocial supports.

Implementation Process

Implementation Timelines

Implementing effective psychosocial practices can take considerable time, especially when multiple EBPs are implemented at once. While research reports may focus on the execution and evaluation phases of initiatives, the time required to plan initiatives and engage stakeholders in a new project should not be underestimated.3,17,19,62 For instance, the Mental Health Treatment Study was carried out between 2006 and 2010, but was preceded by 6 years of conceptual development.28 When timelines to implement EBPs are compressed, adequate communication and engagement with partners may not occur.20

Collaboration and Support of Stakeholders

A common strategy adopted in implementation initiatives is to engage multiple stakeholders in the implementation process. Shared interest in new practices and concerted efforts to initiate change can facilitate implementation of EBPs.20 In some initiatives, the creation of steering committees or implementation teams was used as a strategy to facilitate the involvement of key partners and to develop consensus around implementation plans and issues.16,20,27,63,64

Skills of Front-Line Players

The literature is clear that administrative and mental health authority leadership is critical to implementation success, but the skills and determination of front-line program managers, clinical supervisors, as well as clinical advisers or consultants were equally found to be very important.16,17,48,51 Front-line supervisors working with consultants must ensure that there is a commitment on behalf of partners based on target objectives, offer support and continuous feedback, including recommendations and concrete action plans, as well as rapidly resolve problems that emerge, including relational or political issues.16,21,51 In the NEBPP, implementation suffered when clinical supervisors were unable to provide structure to providers’ practices and failed to master the skills needed for group supervision.51 Some supervisors further sabotaged the implementation process by failing to follow through with commitments they had made to the research team or to their own staff.51

Quality Monitoring and Evaluation

Many authors consider that regular evaluation of practice fidelity and quality is a major determinant of implementation success and improved outcomes for service users.2,10,14–16,25,28,41–43,48,65,66 Fidelity monitoring is thought to communicate key components of an intervention and progress with its implementation, document variation in practices across sites in multi-site studies, improve implementation by raising awareness of nonadherence to best practices, and predict client outcomes.28 Where such evaluations were not valued or poorly executed, implementation typically suffered and services failed to meet the standards dictated by current evidence.16

Discussion

Our analysis, guided by the CFIR model, allowed us to shed light on a range of issues for stakeholders to consider when implementing psychosocial EBPs for people with SMI. Seventeen issues emerged as central to implementation efforts, reflecting more than 30 different constructs identified in the CFIR. In particular, the characteristics of interventions (for example, evidence, complexity, adaptability, and cost), providers (for example, knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, and identity), organizations (for example, culture, leadership, resources, and access to expertise and support), and the broader context (for example, community needs, policies, and incentives) were all found to have strong influences on practice implementation. In addition, critical implementation issues arise at various stages of the implementation process (for example, planning, engagement, execution, and evaluation).

Our review also allowed us to identify the range of players who must assume a collective leadership role to implement a continuum of psychosocial services for people with SMI. Successful implementation occurs when there is a synergy between stakeholders that emerges when each fulfils their necessary roles and commitments.51 The task of creating this synergy to implement single psychosocial EBPs in complex health systems is clearly not an easy one. The challenge, then, of ensuring that communities can access a broad continuum of psychosocial services can thus seem even more daunting. However, while the literature focuses largely on implementation issues related to single EBPs, the articles retained for our review provide some guidance for stakeholders seeking to establish a more comprehensive range of services.

First, implementation initiatives are facilitated when all key stakeholders are engaged in the process from the start, and communication channels exist for them to share their expertise and to voice their concerns with project leaders. As argued by Rosenheck,62 the strength of these coalitions and their ability to mobilize partners and promote change has certainly had as much or more of an influence on eventual outcomes than on the quality of the available evidence for the targeted EBPs. The active involvement of consumers and caregivers should be prioritized so services are evidence-based, correspond to their preferences, and reflect philosophies related to empowerment and recovery.67–70 Several authors further argue that the influence of differences in resources or power held by stakeholders involved in the process should not be neglected or underestimated,13,71,72 suggesting a need for engagement processes that are open, equitable, and empowering.20

Second, efforts to educate providers about the value of evidence-based and recovery-oriented service approaches should precede or complement training strategies for specific EBPs. However, leaders should be careful to identify the learning needs of providers and introduce new psychosocial EBPs at a digestible rhythm so providers are not overburdened and their quality of working life does not suffer.21,44,45 High staff turnover is common in the mental health sector, and work dissatisfaction and the precariousness of providers’ own mental health are serious problems.16,73–75 Engaged leaders and organizational cultures of trust and learning can help providers build a sense of self-efficacy with new practices and ensure that these are aligned with their professional identity as well as the values established in the larger practice setting.

Third, practice contexts that embrace and support knowledge exchange, innovation, and evaluation clearly promote the emergence of new, effective practices more than contexts lacking the leadership, resources, external pressures, or expertise to overcome organizational inertia and alter the status quo. As many of the initiatives show, actions taken at multiple levels by numerous players can facilitate or impede the implementation of psychosocial services. Modern technologies and common systems to allow the widespread monitoring of services and client outcomes are urgently needed to support decision making and increase the quality and range of services for people with SMI.31,48

Finally, authors maintain that establishing service continuums requires that stakeholders adopt a systems view of the broader organization of services, compared with a component view, a perspective that would allow them to appreciate how each component contributes to the whole, to detect gaps in service and training, and to promote creative and critical thinking about the manner in which the system functions.3,76 Once such a perspective is achieved, action to effect changes and better address community needs depends on timely access to funding and resource management that promotes best practices.12,23,48,77 In many jurisdictions, medical models guide the allocation of resources for mental health services, while budgets for community-based and psychosocial services remain limited and unprotected.3,30,57

Conclusion

Modern mental health systems are currently striving to reduce gaps that exist between what is known to be effective and the services that are delivered in routine care. This task involves developing a strong understanding of the implementation process as well as the roles that actors at different levels must play to effectively bring about practice changes. Future efforts to implement psychosocial EBPs should solicit the engagement of all key stakeholders and adopt a systems perspective to reduce inequities in care and make accessible the broadest range of evidence-based services possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dave Erickson for sharing his knowledge, and Dr Alain Lesage for his guidance and helpful comments on the manuscript.

Mr Menear was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canada Graduate Scholarship doctoral award and doctoral awards from the University of Montreal and the Transdisciplinary Understanding and Training on Research–Primary Health Care program. Dr Briand was supported by a CIHR new investigator award (2011–2016) and by the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Montreal. The Canadian Psychiatric Association proudly supports the In Review series by providing an honorarium to the authors.

Abbreviations

- ACT

assertive community treatment

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- EBP

evidence-based practice

- NEBPP

National Implementing Evidence-Based Practice Project

- SMI

severe mental illness

References

- 1.Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(1):11–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033303. ; discussion 20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggeri M, Lora A, Semisa D. The SIEP-DIRECT’S Project on the discrepancy between routine practice and evidence. An outline of main findings and practical implications for the future of community based mental health services. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2008;17(4):358–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornicroft G, Tansella M, Law A. Steps, challenges and lessons in developing community mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):87–92. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the twenty-first century. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ. A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):194–205. doi: 10.1037/a0022284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menear M, Briand C. Implementing evidence-based psychosocial interventions for people with severe mental illness: part 1—review of major initiatives and implementation activities. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(4):178–186. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehman AF. Commentary: what happens to psychosocial treatments on the way to the clinic? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(1):137–139. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al. Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(2):179–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon L. The need for implementing evidence-based practices. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(10):1160–1161. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.10.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horvitz-Lennon M, Donohue JM, Domino ME, et al. Improving quality and diffusing best practices: the case of schizophrenia. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):701–712. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry K, Haddock G. The implementation of the NICE guidelines for schizophrenia: barriers to the implementation of psychological interventions and recommendations for the future. Psychol Psychother. 2008;81(Pt 4):419–436. doi: 10.1348/147608308X329540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Essock SM, Covell NH, Weissman EM. Inside the black box: the importance of monitoring treatment implementation. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):613–615. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WR, Sorensen JL, Selzer JA, et al. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: a review with suggestions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(1):25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bond GR, Drake RE, McHugo GJ, et al. Strategies for improving fidelity in the National Evidence-Based Practices Project. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19(5):569–581. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser LL, Deluca NL, Bond GR, et al. Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(12):926–936. 942. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900009780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold PB, Glynn SM, Mueser KT. Challenges to implementing and sustaining comprehensive mental health service programs. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(2):195–218. doi: 10.1177/0163278706287345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amodeo M, Lundgren L, Cohen A, et al. Barriers to implementing evidence-based practices in addiction treatment programs: comparing staff reports on motivational interviewing, adolescent community reinforcement approach, assertive community treatment, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Eval Program Plann. 2011;34(4):382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson G, Macnaughton E, Goering P, et al. Planning a multi-site, complex intervention for homeless people with mental illness: the relationships between the national team and local sites in Canada’s At Home/Chez soi project. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(3–4):347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isett KR, Burnam MA, Coleman-Beattie B, et al. The state policy context of implementation issues for evidence-based practices in mental health. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(7):914–921. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW. Psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder: a review of literature and introduction of the systematic treatment enhancement program. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40(4):116–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruggeri M. Guidelines for treating mental illness: love them, hate them. Can the SIEP-DIRECT’S Project serve in the search for a happy medium? Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2008;17(4):270–277. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swain K, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, et al. The sustainability of evidence-based practices in routine mental health agencies. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(2):119–129. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundgren L, Amodeo M, Cohen A, et al. Modifications of evidence-based practices in community-based addiction treatment organizations: a qualitative research study. Addict Behav. 2011;36(6):630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glasner-Edwards S, Rawson R. Evidence-based practices in addiction treatment: review and recommendations for public policy. Health Policy. 2010;97(2–3):93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown AH, Cohen AN, Chinman MJ, et al. EQUIP: implementing chronic care principles and applying formative evaluation methods to improve care for schizophrenia: QUERI Series. Implement Sci. 2008;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frey WD, Drake RE, Bond GR, et al. Mental Health Treatment Study Final report. Baltimore (MD): Social Security Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glynn SM. The challenge of psychiatric rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(5):401–406. doi: 10.1007/s11920-996-0034-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latimer EA, Bond GR, Drake RE. Economic approaches to improving access to evidence-based and recovery-oriented services for people with severe mental illness. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(9):523–529. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rieckmann TR, Kovas AE, Cassidy EF, et al. Employing policy and purchasing levers to increase the use of evidence-based practices in community-based substance abuse treatment settings: reports from single state authorities. Eval Program Plann. 2011;34(4):366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pathways to Housing Inc Providing Housing First and recovery services for homeless adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(10):1303–1305. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rieckmann T, Bergmann L, Rasplica C. Legislating clinical practice: counselor responses to an evidence-based practice mandate. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;(Suppl 7):27–39. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.601988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tai B, Straus MM, Liu D, et al. The first decade of the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network: bridging the gap between research and practice to improve drug abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38(Suppl 1):S4–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlson L, Rapp CA, Eichler MS. The experts rate: supervisory behaviors that impact the implementation of evidence-based practices. Community Mental Health J. 2012;48(2):179–186. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9367-4. ; Epub 2010 Dec 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corrigan PW, Steiner L, McCracken SG, et al. Strategies for disseminating evidence-based practices to staff who treat people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1598–1606. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corrigan P, McCracken S, Blaser B. Disseminating evidence-based mental health practices. Evid Based Ment Health. 2003;6(1):4–5. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.6.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falloon IR, Held T, Roncone R, et al. Optimal treatment strategies to enhance recovery from schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32(1):43–49. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garety PA. The future of psychological therapies for psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2003;2(3):147–152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehman WE, Simpson DD, Knight DK, et al. Integration of treatment innovation planning and implementation: strategic process models and organizational challenges. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):252–261. doi: 10.1037/a0022682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martino S, Brigham GS, Higgins C, et al. Partnerships and pathways of dissemination: the National Institute on Drug Abuse–Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Blending Initiative in the Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38(Suppl 1):S31–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torrey WC, Bond GR, McHugo GJ, et al. Evidence-based practice implementation in community mental health settings: the relative importance of key domains of implementation activity. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39(5):353–364. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McHugh RK, Barlow DH. The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments. A review of current efforts. Am Psychol. 2010;65(2):73–84. doi: 10.1037/a0018121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prytys M, Garety PA, Jolley S, et al. Implementing the NICE guideline for schizophrenia recommendations for psychological therapies: a qualitative analysis of the attitudes of CMHT staff. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(1):48–59. doi: 10.1002/cpp.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sin J, Scully E. An evaluation of education and implementation of psychosocial interventions within one UK mental healthcare trust. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15(2):161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morriss R. Implementing clinical guidelines for bipolar disorder. Psychol Psychother. 2008;81:437–458. doi: 10.1348/147608308X278105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bond GR. Deciding versus implementing: a comment on “What gets noticed: how barrier and facilitator perceptions relate to the adoption and implementation of innovative mental health practices.”. Community Mental Health J. 2009;45(4):270–271. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9190-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drake RE, Bond GR, Essock SM. Implementing evidence-based practices for people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(4):704–713. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lundgren LM, Rieckmann T. Research on implementing evidence-based practices in community-based addiction treatment programs: policy and program implications. Eval Program Plann. 2011;34(4):353–355. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torrey WC, Lynde DW, Gorman P. Promoting the implementation of practices that are supported by research: the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practice Project. Child Adolescent Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005;14(2):297–306. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rapp CA, Etzel-Wise D, Marty D, et al. Barriers to evidence-based practice implementation: results of a qualitative study. Community Mental Health J. 2010;46(2):112–118. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9238-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corrigan PW. Building teams and programs for effective rehabilitation. Psychiatr Q. 1998;69(3):193–209. doi: 10.1023/a:1022149226408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rieckmann TR, Kovas AE, Fussell HE, et al. Implementation of evidence-based practices for treatment of alcohol and drug disorders: the role of the state authority. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36(4):407–419. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9122-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torrey EF. Economic barriers to widespread implementation of model programs for the seriously mentally ill. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41(5):526–531. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.5.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mueser K, Torrey W, Lynde D, et al. Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behav Modif. 2003;27(3):387–411. doi: 10.1177/0145445503027003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Falloon IR. Optimal treatment for psychosis in an international multisite demonstration project. Optimal Treatment Project Collaborators. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(5):615–618. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lehman AF. Quality of care in mental health: the case of schizophrenia. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18(5):52–65. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Capoccia V, Gustafson DH, O’Brien J, et al. Barriers and strategies to implement evidence-based practices. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(2):219–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isett KR, Burnam MA, Coleman-Beattie B, et al. The role of state mental health authorities in managing change for the implementation of evidence-based practices. Community Mental Health J. 2008;44(3):195–211. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drake RE, Essock SM. The science-to-service gap in real-world schizophrenia treatment: the 95% problem. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(4):677–678. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roe D, Bril-Barniv S, Kravetz S. Recovery in Israel: a legislative response to the needs–rights paradox. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24(1):48–55. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.652600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenheck R. Stages in the implementation of innovative clinical programs in complex organizations. J Nerv Mental Dis. 2001;189(12):812–821. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200112000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.UK Department of Health (DH) The mental health policy implementation guide. London (GB): DH; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(11):1028–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flynn PM, Brown BS. Implementation research: issues and prospects. Addict Behav. 2011;36(6):566–569. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al. Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Serv. 2001;52(1):45–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davidson L. Creating a recovery-oriented system of behavioral health care: moving from concept to reality. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2007;31(1):23–31. doi: 10.2975/31.1.2007.23.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Farkas M. The vision of recovery today: what it is and what it means for services. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):68–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) Changing directions, changing lives: the mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary (AB): MHCC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shepherd G, Boardman J, Slade M. Making recovery a reality Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lundgren L, Amodeo M, Krull I, et al. Addiction treatment provider attitudes on staff capacity and evidence-based clinical training: results from a national study. Am J Addict. 2011;20(3):271–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Components of a modern mental health service: a pragmatic balance of community and hospital care: overview of systematic evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:440. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rössler W. Stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in mental health workers. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(Suppl 2):65–69. doi: 10.1007/s00406-012-0353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salyers M, Rollins A, Kelly Y, et al. Job satisfaction and burnout among VA and community mental health workers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(2):69–75. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0375-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wood S, Stride C, Threapleton K, et al. Demands, control, supportive relationships and well-being amongst British mental health workers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(10):1055–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thornicroft G, Tansella M. The balanced care model for global mental health. Psychol Med. 2012;11:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lundgren L, Chassler D, Amodeo M, et al. Barriers to implementation of evidence-based addiction treatment: a national study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(3):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.08.003. ; Epub 2011 Oct 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goldberg RW, Resnick SG. US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) efforts to promote psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2010;33(4):255–258. doi: 10.2975/33.4.2010.255.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Condon TP, Miner LL, Balmer CW, et al. Blending addiction research and practice: strategies for technology transfer. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(2):156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bowden CL, Perlis RH, Thase ME, et al. Aims and results of the NIMH Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(3):243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frey WD, Azrin ST, Goldman HH, et al. The Mental Health Treatment Study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31(4):306–312. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.306.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goering PN, Streiner DL, Adair C, et al. The At Home/Chez soi trial protocol: a pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a Housing First intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000323. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Falloon IR, Montero I, Sungur M, et al. Implementation of evidence-based treatment for schizophrenic disorders: two-year outcome of an international field trial of optimal treatment. World Psychiatry. 2004;3(2):104–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.UK Department of Health (DH) A national service framework for mental health. London (GB): DH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 85.UK Department of Health (DH) The national service framework for mental health—five years on. London (GB): DH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Joseph R, Birchwood M. The national policy reforms for mental health services and the story of early intervention services in the United Kingdom. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30(5):362–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roe D, Hasson-Ohayon I, Lachman M, et al. Selecting and implementing evidence-based practices in psychiatric rehabilitation services in Israel: a worthy and feasible challenge. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2007;44(1):47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.