Abstract

This paper is an initial attempt to collate the literature on psychiatric inpatient recovery-based care and, more broadly, to situate the inpatient care sector within a mental health reform dialogue that, to date, has focused almost exclusively on outpatient and community practices. We make the argument that until an evidence base is developed for recovery-oriented practices on hospital wards, the effort to advance recovery-oriented systems will stagnate. Our scoping review was conducted in line with the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (commonly referred to as PRISMA) guidelines. Among the 27 papers selected for review, most were descriptive or uncontrolled outcome studies. Studies addressing strategies for improving care quality provide some modest evidence for reflective dialogue with former inpatient clients, role play and mentorship, and pairing general training in recovery oriented care with training in specific interventions, such as Illness Management and Recovery. Relative to some other fields of medicine, evidence surrounding the question of recovery-oriented care on psychiatric wards and how it may be implemented is underdeveloped. Attention to mental health reform in hospitals is critical to the emergence of recovery-oriented systems of care and the realization of the mandate set forward in the Mental Health Strategy for Canada.

Keywords: recovery, recovery-oriented care, mental health reform, inpatient, severe mental illness, systems, implementation, review

Abstract

Cet article est une première tentative de colliger la littérature sur les soins axés sur le rétablissement de patients psychiatriques hospitalisés et, plus généralement, de situer le secteur des soins des patients hospitalisés dans le dialogue sur la réforme de la santé mentale qui, jusqu’ici, a porté presque exclusivement sur les pratiques ambulatoires et communautaires. Nous alléguons que jusqu’à ce qu’une base de données probantes soit établie pour les pratiques axées sur le rétablissement dans les services d’hospitalisation, les efforts en vue d’améliorer les systèmes axés sur le rétablissement stagneront. Notre étude de portée a été menée conformément aux lignes directrices des éléments de rapport préférentiels pour les revues systématiques et les méta-analyses de 2009 (PRISMA). Sur les 27 articles sélectionnés pour la revue, la plupart étaient des études descriptives ou de résultats non contrôlés. Les études abordant les stratégies d’amélioration de la qualité des soins offrent une évidence modeste pour le dialogue réflectif avec d’anciens patients hospitalisés, le jeu de rôle et le mentorat, et le jumelage de la formation générale en soins axés sur le rétablissement avec la formation en interventions spécifiques, comme le programme de prise en charge de la maladie et de rétablissement. En ce qui concerne d’autres domaines de la médecine, l’évidence à la question des soins axés sur le rétablissement dans les services d’hospitalisation et à la manière de les mettre en œuvre est sous-développée. L’attention portée à la réforme de la santé mentale dans les hôpitaux est essentielle à l’instauration de systèmes de soins axés sur le rétablissement et à la réalisation du mandat proposé dans la Stratégie en matière de santé mentale pour le Canada.

The reform of mental health care systems continues to gain momentum internationally.1 Enhancing recovery is a key aspect of national mental health reforms in high-income countries, including Canada,2 and it is one of the fundamental principles of the World Health Organization’s Comprehensive Action Plan for Mental Health.3 Recovery is typically referenced against severe forms of mental illness and, unlike recovery as remission of illness, it refers to the “developing of new meaning and purpose in life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of psychiatric disability.”4, p 14 In contrast with models of service provision that focus on symptoms, disability, risk, and compliance with treatment, recovery-based services consider wider outcomes, such as competitive employment, self-management skills, and independence.5,6

However, there are some major challenges at the systems level in realizing the mandates and objectives for recovery-oriented reform as set out by system planners and administrators. Here, a service system refers to a combination of services organized to meet the needs of a particular clinical population.7 The evidence for recovery-oriented interventions, and much of the framing of recovery, focuses on outpatient and community-based interventions that target employment,8 education,9 housing,10 and models of outreach.11 There remains considerable ambiguity around how recovery-oriented mental health systems can successfully move from promotion of principles to the implementation of integrated practices.1,12–14

Arguably, the most obvious impediment to the implementation of mental health reform at a systems level is the lack of clear, evidence-based, and practical direction for hospitals. Despite its accounting for about one-half of all mental health and addictions expenditures in Canada,15 the literature provides little guidance on how inpatient care could be improved, with no systematic reviews and few randomized trials. Hospitals continue to apply models of care that predate the recovery movement.14,16 While practices are highly variable across settings, there are consistent accounts of coercive practices, a lack of safety from staff and co-patients, a general process of dehumanization, loss of motivation, and an atrophy of self-care skills.14,17,18

Our paper is an initial attempt to collate the literature on psychiatric inpatient recovery-based care and, more broadly, to situate this very large care sector within a dialogue that, to date, has focused almost exclusively on outpatient and community practices. An argument is made that until a base of evidence is developed for recovery-oriented practices on hospital wards, the effort to advance recovery-oriented systems will stagnate.

Highlights

While preliminary, evidence exists that recovery-oriented care is relevant to inpatient contexts, and there are strategies available for implementing such practices.

Advancing mental health reform in hospitals holds the promise of leading to better integrated and more effective systems of care.

Method

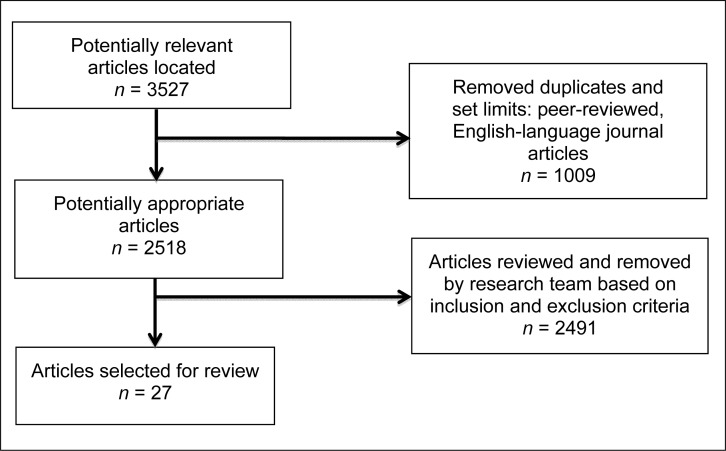

Our review was conducted in line with the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (commonly referred to as PRISMA) guidelines.19 A broad list of terms related to advancing recovery-oriented care on inpatient units was compiled and used as standalone key terms or combined with others to create key search terms. These included the following: “recovery,” “recovery oriented care,” “advancing care,” “changing” “improving,” “client centered,” “patient involvement,” “patient engagement,” “mental health reform,” “education,” and “nursing”; and “inpatient,” “psychiatry,” and “mental illness.” Five databases were searched: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Healthstar, EBM Reviews, the Cochrane Database, along with secondary searches conducted via Google Scholar. All database searches were limited to abstract-level, peer-reviewed, English-language articles published between 1950 and 2013. Further manual searches from reference lists were conducted, as well as recommendations by the research team.

Extracted papers focused on improving the quality of stay, clinical practice or structural systems (for example, training and management) related to patient care on inpatient psychiatric units, including forensic and secure units (Figure 1). Editorials, grey literature reports, letters, books, and book chapters were excluded—a review of which is likely warranted in and of itself. Among the 27 papers selected for review, most were descriptive or uncontrolled outcome studies. Only 4 studies employed controlled designs.

Figure 1.

Search strategy

Results

Problems and Barriers to Change

Seven papers focused on describing the challenges involved in advancing mental health reform on inpatient units, and were based primarily on cross-sectional surveys of staff and patients. The emphasis of patients in this context was the desire to have their needs heard and respected, being treated in a manner that is person-centred and ethical,20 and their highlighting of wards as being typically characterized by poor access to information and compulsory aspects of care.21 Also highlighted was the poor quality of physical space in most inpatient settings, which often limited the ability of staff to implement care in a manner that effectively engaged key supports, such as family- and otherwise-provided safe and stimulating environments.20,22

Other problems noted in these studies included highly variable and difficult-to-monitor nursing practices,23 very limited individualized care planning, patient engagement, and shared decision making, all within the context of increasingly shorter stay and high-acuity settings that emphasize risk management and stabilization.12,24 These challenges are exacerbated by the low morale observed on wards, with up to 40% of psychiatric nurses dissatisfied with their jobs25 and, compared with community mental health workers, evidence of generally greater pessimism and less optimism about the potential for recovery of their clients.14

Are Recovery-Oriented Wards Better for Clients?

In contrast with the strong emphasis on recovery-oriented care in policy, public, and advocacy forums, the literature suggesting that recovery-oriented wards are more effective is very sparse. In part, mental health reform is about a greater recognition of patient rights and the provision of more individualized, culturally competent services. In this light, the rationale for advancing care is more one of ethics than of evidence. Similarly, patient engagement aspects of recovery-oriented care, such as the cultivation of hope and alignment around goals, are common factors of psychiatric interventions. A large body of work exists across a range of mental health interventions to suggest that common factors are an important determinant of clinical outcome.26 Our review found only 2 studies that have directly examined factors associated with the recovery orientation of psychiatric wards. One suggested that when effectively engaged in a recovery-oriented conceptualization of their illness (compared with purely medical and custodial perspectives), inpatient clients have a better quality of life, better engagement in treatment, and fewer social problems.27 Another strong association was between client satisfaction and staff efforts to convey empathy and actively engage in teaching about medication, illness self-management, and stress management.28

How Can Psychiatric Inpatient Wards Be Improved?

Most papers (n = 17) identified in the scoping review focus on specific strategies to enhance recovery-oriented care on psychiatric wards. These included papers overtly referencing recovery and those containing components of recovery-oriented care, even if not overtly identified as such (for example, empowerment and illness self-management). The types of papers in this area ranged from studies of outcome to very broad, descriptive works addressing models of practice that were not tied to process or outcome data. For example, the Tidal Model, aligning with practice commentary that focuses on developing stronger relationships between staff and clients, proposes a client empowerment approach to nursing practice.29,30 It emphasizes a holistic assessment and an individualized, empathetic approach to care that focuses on providing only the level of support necessary.29 The authors of the Tidal Model frame their efforts as a social movement, addressing equity rather than an intervention strategy that is validated through scientific study. This was one of several reports of general programs of training and practice designed to enhance the degree to which inpatient care is client-centred, empowering, and based on approaches that emphasize various ways of identifying individualized tools where recovery can be better supported. Such approaches include scripting of clinical interactions and designing physical spaces,31 the Good Lives Model,32 which is a strengths-based approach, grounded in personal goals and an emphasis on community integration, and papers generally recommending recovery-oriented programming and the means to hold clinicians accountable for such practices.16,22,33–37 While not suggesting that they are outside the bounds of scientific inquiry, these latter approaches were not examined with respect to impact other than in some instances examining the level of knowledge uptake in trainings.

While it is difficult to assess the impact or potential impacts of such approaches, several groups have examined the outcomes of initiatives ranging in scope and focus. Examples of more specific, circumscribed interventions include an RCT in which a year-long series of facilitated conversations between inpatient providers and former patients with schizophrenia resulted in improved attitudes toward, and knowledge about, recovery and recovery-oriented practice, with some modest indications of improved practice.38 Another study,39 examining outcomes, found that staff education in areas of recovery and wellness, goal-setting, and coping resulted in pre–post improvements in client functioning.

Four studies41–44 were found that document more extensive programs of service development, 3 of which were conducted with varying degrees of controlled designs. Forums for ward staff to engage in reflective practice groups with an equal representation of people with SMI, paired with skill development through role plays and ongoing mentorship, revealed significant improvements in teamwork, the implementation of recovery-oriented services, and staff competency in providing holistic care.40 An uncontrolled pre–post design study41 demonstrated improvements in staff attitudes and client satisfaction after the implementation of a program that included mentoring in recovery-oriented skills, tailoring care to client goals, and incorporating treatments, such as Liberman’s independent living skills modules and Mueser’s IMR groups. In line with this finding, there is evidence that specific practical trainings in interventions, such as IMR and motivational interviewing, when accompanying more generic trainings in recovery-oriented care, lead to stronger improvements in recovery orientation.42 The IMR program is particularly salient given its evidence base and its explicitly recovery-oriented curriculum, which emphasizes establishing personal recovery goals, improving coping skills, building on strengths, and self-advocacy.43 More difficult to interpret is the impact of a year-long quality improvement initiative targeting recovery-oriented care. While improvements were found in the recovery orientation of services, and staff perceptions of the initiative being effective, there were no improvements in clients’ quality of life.44

Discussion

In contrast with the intensive examination of recovery-oriented care as it applies to outpatient clinical practice domains, research in this area, as it pertains to psychiatric wards, is markedly underdeveloped. This discrepancy is all the more striking considering the expense and degree of use of inpatient care by people with mental illness. At a pivotal point of clinical engagement, many patients are exposed to historical models of care, with very little guidance to be found in the research literature as to how such settings may be improved. However, there is some modest evidence for strategies, such as ongoing reflective dialogue with former inpatient clients,38 role play, and mentorship in training,40 and training in which general strategies are tied with training in specific clinical interventions.42

Efforts Toward Health Care Reform in Inpatient Care Outside of Psychiatry

Looking beyond psychiatry, there are substantial bodies of research examining strategies for better attending to psychosocial aspects of inpatient care. This includes multiple RCTs, in fields such as oncology and cardiology, which aim to improve the experience of treatments, improving psychosocial aspects of care, emphasizing quality of life, and focusing on independence and adapting life around illness in a manner that echoes the concept of recovery in mental health. The success of service improvement approaches outside psychiatry seems to rest heavily on staged, well-integrated, interdisciplinary work supported strongly by leadership.

Examples of specific EBP approaches include the 6-stage process developed by French,45 which includes locating the problem, reviewing the literature and one’s own practice, applying research findings, quality assurance activities, team involvement and collaborative work, and cost analysis. Much of this work requires empowering unit staff, including nurses and physicians, in taking a leadership role on change in an organization, a continued program of education and feedback, and improving communications with patients. The key factor here is that each of these activities is linked to measures of patient outcome.

Examples of successful approaches to improving clinician– patient interactions, in which a great deal of work has been done in inpatient oncology, has included the use of videotaping patient and nurse interactions to identify facilitating or blocking behaviours.46–48 Such intensive trainings, which emphasize experiential learning around effectively engaging patients, have been rigorously investigated and found to improve the quality of inpatient care and have contributed to the development of EBP models.

In addition to these specific types of EBP approaches, change in the health sector has been embedded in broader policy agendas. One area in which we see this happen in a systematic way is in the oncology field in the United Kingdom, where many of these requirements were written into the UK Cancer Plan.49 This led to the evidence-based Transforming Inpatient Framework for Spread, aimed at providing a framework of indicators for good practice at a local level.50

Points of Controversy

The haziness that attends the concept of recovery, specifically, and mental health reform, more broadly, leads to many professionals believing that it does not apply to inpatient units, where people are in crisis or are otherwise seen as unable to directly collaborate in care planning.51 Both a problem of unclear definition and simplistic interpretation, such a perspective does not acknowledge that just as with situations in which people are medically incapacitated, respectful, comprehensive, culturally competent, and individualized care can still occur. Much more controversial are the implications of mental health reform for a less medicalized understanding of SMI, with medications being found to have less impact than previously believed and social determinants of illness onset and course being more firmly established.52,53 This has numerous implications for professional roles in clinical decision making as well as for staffing models (for example, reconsidering staff complements on units being dominated by nursing.)

Locating the Ward in a Recovery-Oriented System

Few would argue that there is no need to provide intensive support, including caretaking and prescriptive treatment, when a person’s life is, or the lives of others are, at risk. The problem, as noted above, lies in the application of historical models of care that broaden the normal–abnormal divide and in hospital care mandates extending beyond addressing overt dangerousness and incapacity.16 Indeed, insomuch as ward practices in many contexts are historical, so are the critiques about them. For example, the sociologist Erving Goffman in his seminal work Asylums,54 an ethnography of a psychiatric institution completed in the 1950s, comments extensively on the manner in which inpatient care was highly stigmatizing, coercive and overly restrictive, and stripped people of their nonillness identities. Subsequent work in this period went on to further explore the problems of depersonalization, loss of identity, and the loss of a sense of responsibility for one’s life,55 with the suggestion that the more wards were isolating and lacking opportunities for social engagement, the more withdrawn and the lower the community functioning of the people on them.56,57 These points of research and critique moved across scientific forums (perhaps most famously in the Rosenhan study55), played an important role in catalyzing consumer-survivor activism,58 and have been extensively explored in popular media; for example, in the films One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and Girl, Interrupted (1999). As such, this topic, as it is situated in the language of recovery-oriented care, may be thinly addressed, but key aspects of it have a lengthy and highly contentious history in psychiatric service provision.

Nonetheless, promising strategies exist for changing ward practice to maximize collaboration and empowerment, and, when temporarily restricting freedoms, providing care informed by advanced directives. The rationale for such a movement lies in the large bodies of evidence suggesting that exposure-based strategies that embrace measured risk, such as supported employment,8 have far greater impact than custodial services that actively or passively discourage autonomy and lower the life expectations of people with mental illness.

Enhanced inpatient practices would then, in turn, need to connect effectively with recovery-oriented interventions in the community to move systems, rather than services, forward. Typically, such transitions are fraught with the challenge of poor communication between in- and outpatient providers working in siloed systems, along with high rates of relapse, particularly in the first month postdischarge.59 This has led to the development of transition-focused interventions, several of which embed recovery principles in the use of peer support and the emphasis on community engagement,60,61 or in the use of rehabilitation-focused partial hospitals that facilitate earlier discharge and reduce admissions.62 Such interventions show considerable promise in reducing rates of rehospitalization and improving community participation.63 However, should hospitals more effectively engage in efforts toward mental health reform, the challenges of transition out of hospital may be considerably reduced. First, there would be a less radical shift in the model of care, with recovery-oriented hospital care more seamlessly merging with outpatient and community care. Second, should people with mental illness perceive inpatient care as being less highly aversive,16 they may access hospitals earlier in the progression of acuity, rather than as a last resort when a full-blown crisis requires emergency hospitalization owing to safety concerns. Such a scenario may lead to more effective clinical engagement, briefer periods of hospitalization, and more effective transitions back into the community. Therein lies the recovery-oriented system of care—one that better reflects policy mandates2 and practice recommendations.63

Unfortunately, in many contexts, the inverse of the recovery-oriented systems solution would seem to have been enacted. Rather than updating and improving inpatient practices and connecting them to enhanced outpatient care, there is a trend toward narrow, coercive, and restrictive approaches reaching out into community contexts in the form of assertive outreach strategies and CTOs.64 In this manner, the contemporary, so-called, institution is much less bound by hospital walls. In parallel with the concerns that custodial approaches in hospitals are derived from sources other than evidence-based and ethical practices, we see practices, such as CTOs, being taken up at a pace that far outstrips the dubious evidence about their effectiveness, at least as they are currently being employed.65–67 This is only the latest divisive turn in the decades-old dilemma about how to effectively and ethically provide services for people suffering from SMIs in a context where the discussion of mandates and systems are overshadowed by a focus on interventions.68

Areas Requiring Further Study and Consideration

Aside from the general need for the development of a body of inpatient practice research that could complement those developed in other areas of medical intervention, there are several specific questions that need to be addressed. For example, will the rigorous study of the implementation of recovery-oriented care on psychiatric inpatient units demonstrate better outcomes in care quality and efficiency? Aside from strategies at a unit level for advancing care quality, how can service improvement best be rolled out at the hospital level in a manner that addresses the complexities of interdisciplinary teams, staff job dissatisfaction, multiple stakeholders, including the criminal justice system, and entrenched cultures of custodial care delivery? Lastly, there would seem to be a need for some scrutiny of the role of decision makers. From national strategy to hospital mission statement, there is clear evidence that many decision makers have adopted the language and values associated with mental health reform. However, a recent study of Canadian policy-maker perspectives on mental health reform noted that most do not see the relevance of recovery-oriented reform in hospital settings.69 Further, recovery-oriented system change was viewed as something to be left to direct service providers to address, with acknowledgement of the promise of a, so-called, new breed of professionals entering the care system.69 Internationally, the challenge in implementing recovery-oriented systems in high-income countries, one which has persisted in many North American settings for 20 years or more,4 attests to the need for more direct involvement by policy-makers. With better evidence to guide inpatient practice and better integrated services that embody the principles of recovery and recovery-oriented care, the vision of the Mental Health Strategy for Canada may be realized, and the impacts of mental illness upon fiscal, social, and human capital may be considerably reduced.

Acknowledgments

This paper was developed with support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number 124734). Appreciation is extended to Dr Stephanie Penney and Dr Sandy Simpson for their support in this initiative. The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, related to this submission to declare.

The Canadian Psychiatric Association proudly supports the In Review series by providing an honorarium to the authors.

Abbreviations

- CTO

community treatment order

- EBP

evidence-based practice

- IMR

Illness Management and Recovery

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SMI

severe mental illness

References

- 1.Piat M, Sabetti J. The development of a recovery-oriented mental health system in Canada: what the experience of commonwealth countries tells us. Can J Comm Ment Health. 2009;2:17–33. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2009-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) Changing directions, changing lives: the mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary (AB): MHCC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. Geneva (CH): WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connell M, Tondora J, Croog G, et al. From rhetoric to routine: assessing perceptions of recovery-oriented practices in a state mental health and addiction system. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005;28:378–386. doi: 10.2975/28.2005.378.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drake RE, Whitley R. Recovery and severe mental illness: description and analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(5):236–242. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauber SR. The human service delivery system. New York (NY): Columbia University; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR, et al. An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31:280–290. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.280.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard E, Bruer R. Supported education strategies for people with severe mental illness: a review of evidence based practice. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. 2007;11:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rog D. The evidence on supported housing. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:334–344. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.334.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kidd SA, George L, O’Connell M, et al. Fidelity and recovery in assertive community treatment. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:342–350. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piat M, Lal S. Service providers’ experiences and perspectives on recovery-oriented mental health system reform. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2012;35:289–296. doi: 10.2975/35.4.2012.289.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anthony WA. A recovery oriented service system: setting some system level standards. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2000;24:159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai J, Salyers M. Recovery orientation in hospital and community settings. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2010;37:385–399. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs P, Yim R, Ohinmaa A, et al. Expenditures on mental health and addictions for Canadian provinces in 2003–2004. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:306–313. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith R, Bartholomew T. Will hospitals recover? The implications of a recovery-orientation. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2006;9:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson I, Lundman B. Patients’ experience of involuntary psychiatric care. Good opportunities and great losses. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2002;9:639–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilburt H, Rose D, Slade M. The importance of relationships in mental health care: a qualitative study of service users’ of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:92. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blomqvist M, Ziegart K. ‘Family in the waiting room’: a Swedish study of nurses’ conceptions of family participation in acute psychiatric inpatient settings. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2011;20:185–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuosmanen L, Hätönen H, Jyrkinen AR, et al. Patient satisfaction with psychiatric inpatient care. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55:655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen S-P, Krupa T, Lysaght R, et al. The development of recovery competencies for in-patient mental health providers working with people with serious mental illness. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40:96–116. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindwall L, Boussaid L, Kulzer S, et al. Patient dignity in psychiatric nursing practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health. 2012;19:569–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seed MS, Torkelson DJ. Beginning the recovery journey in acute psychiatric care: using concepts from Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33:394–398. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.663064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanrahan NP, Aiken LH. Psychiatric nurse reports on the quality of psychiatric care in general hospitals. Qual Manag Health Care. 2008;17:210–217. doi: 10.1097/01.QMH.0000326725.55460.af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert MJ, Barley DE. Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome In: Norcross JC, editor Psychotherapy relationships that work: therapists contributions and responsiveness to patients. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gudjonsson GH, Savona CSV, Green T, et al. The recovery approach to the care of mentally disordered patients. Does it predict treatment engagement and positive social behaviour beyond quality of life? Pers Individ Dif. 2011;51:899–903. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hackman A, Brown C, Yang Y, et al. Consumer satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric treatment among persons with severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2007;43:6. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barker P. The Tidal Model: developing an empowering, person-centred approach to recovery within psychiatric and mental health nursing. J Psychiatr Ment Health. 2001;8:233–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchanan-Barker P, Barker PJ. The Tidal Commitments: extending the value base of mental health recovery. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bromley E. Building patient-centeredness: hospital design as an interpretive act. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1057–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies J, Maggs RG, Lewis R. The development of a UK low secure service: philosophy, training, supervision and evaluation. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 2010;9:334–342. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill P, McKenna P, O’Neill H, et al. Pillars and pathways: foundations of recovery in Irish forensic mental health care. Br J Forensic Pract. 2010;12:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linhorst DM, Eckert A, Hamilton G, et al. The involvement of a consumer council in organizational decision making in a public psychiatric hospital. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2001;28:427–438. doi: 10.1007/BF02287773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orem DE, Taylor SG. Reflections on nursing practice science: the nature, the structure, and the foundation of nursing sciences. Nurs Sci Q. 2011;24:35–41. doi: 10.1177/0894318410389061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randal P, Stewart MW, Proverbs D, et al. “The Re-covery Model”—an integrative developmental stress–vulnerability–strengths approach to mental health. Psychosis. 2009;1:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swarbrick M, Brice GH. Sharing the message of hope, wellness, and recovery with consumers psychiatric hospitals. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2006;9:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kidd SA, McKenzie K, Collins A, et al. Advancing the recovery orientation of hospital care through staff engagement with former clients of inpatient units. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):221–225. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elbaz-Haddad M, Savaya R. Effectiveness of a psychosocial intervention model for persons with chronic psychiatric disorders in long-term hospitalization. Eval Rev. 2011;35:379–398. doi: 10.1177/0193841X11406080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young AS, Chinman M, Forquer SL, et al. Use of a consumer-led intervention to improve provider competencies. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:967–975. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayerhoff DI, Smith R, Schleifer SJ. Academic–state hospital collaboration for a rehabilitative model of care. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1474–1475. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai J, Salyers MP, Lobb AL. Recovery-oriented training and staff attitudes over time in two state hospitals. Psychiatr Q. 2010;81:335–347. doi: 10.1007/s11126-010-9142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(Suppl 1):S32–S43. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strating MM, Broer T, van Rooijen S, et al. Quality improvement in long-term mental health: results from four collaboratives. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19:379–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.French P. The development of evidence-based nursing. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29:72–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilkinson S. Factors which influence how nurses communicate with cancer patients. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16:677–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uitterhoeve R, Bensing J, Dilven E, et al. Nurse–patient communication in cancer care: does responding to patient’s cues predict patient satisfaction with communication. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1060–1068. doi: 10.1002/pon.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maguire P, Faulkner A, Booth K, et al. Helping cancer patients disclose their feelings. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:78–81. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.UK Department of Health (DH) The NHS Cancer Plan. London (GB): DH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Health Service (NHS) NHS Improvement transforming inpatient care—programme transforming care for cancer inpatients: spreading the winning principles and good practice. London (GB): NHS Improvement; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidson L, O’Connell M, Tondora J, et al. The top 10 concerns about recovery encountered in mental health system transformation. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:640–645. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lepping P, Sambhi RS, Whittington R, et al. Clinical relevance of findings in trials of antipsychotics: systematic review. Br J Psychiatr. 2011;198:341–345. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McKenzie KJ. How do social factors cause psychotic illnesses? Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:41–43. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goffman E. Asylums. Garden City (NY): Anchor Books; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosenhan D. On being sane in insane places. Science. 1973;179:250–258. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4070.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wing J, Brown G. Institutionalism and schizophrenia: a comparative study of three mental hospitals, 1960–1968. London (GB): Cambridge University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wing J, Brown G. Social treatment of chronic schizophrenia: a comparative survey of three hospitals. J Ment Sci. 1961;107:847. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frese F, Davis W. The consumer-survivor movement, recovery, and consumer professionals. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1997;28:243–245. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vigod S, Kurdyak P, Dennis C, et al. Transitional interventions to reduce early psychiatric readmission in adults: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:187–194. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.115030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chinman M, Weingarten R, Stayner D, et al. Chronicity reconsidered: improving person–environment fit through a consumer run service. Community Ment Health J. 2001;37:215–229. doi: 10.1023/a:1017577029956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forchuk C, Martin ML, Chan YL, et al. Therapeutic relationships: from psychiatric hospital to community. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2005;12:556–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marshall M, Crowther R, Sledge WH, et al. Day hospital versus admission for acute psychiatric disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD004026. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004026.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sowers W. Transforming systems of care: the American Association of Community Psychiatrists guidelines for recovery oriented services. Community Mental Health J. 2006;41:757–774. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-6433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chow WS, Priebe S. Understanding psychiatric institutionalization: a conceptual review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burns T, Rugkasa J, Molodynski A, et al. Community treatment orders for patients with psychosis (OCTET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1627–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swartz MS, Swanson JW. Involuntary outpatient commitment, community treatment orders, and assisted outpatient treatment: what’s in the data? Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(9):585–591. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kisely S, Campbell L, Preston N. Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD004408. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaimowitz G. Community treatment orders: an uncertain step. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:577–578. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Piat M, Sabetti J, Bloom D. The transformation of mental health services to a recovery-oriented system of care: Canadian decision maker perspectives. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56:168–177. doi: 10.1177/0020764008100801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]