Abstract

Objective:

Research is needed to clarify and improve our understanding of appropriateness and safety issues concerning antidepressant (AD) treatment. We explored the long-term trend in the dispensing of pediatric ADs using provincial, population-based data from Canada.

Methods:

Data covering 22 ADs were drawn from the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health administrative data files in outpatient settings. The data were for 9 triennial years from 1983 to 2007, a 24-year period, for those aged 0 to 19 in the general population. Descriptive analyses were used.

Results:

In 1983, 5.9 per 1000 population aged 0 to 19 were dispensed at least 1 AD; this decreased to 5.1 per 1000 population in 1989, and then increased to 15.4 per 1000 population in 2007, with a slower increase after 2004. Both sexes were dispensed more ADs from 1989 onwards, with females being the heavier users. The rate of AD use increased significantly with age, and this trend became more pronounced after 1998. Family physicians were the major prescribers and their prescriptions significantly increased from 1989 to 2004 and decreased in 2007. The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was the major reason for the increase. The number of AD scripts per patient also increased.

Conclusions:

The growth in the prevalence of AD use among children and youth was largely caused by the use of SSRIs. The possibility of safety issues induced by AD use among children and adolescents, and different patterns of medication practice, suggest continuing education is warranted.

Keywords: antidepressants, Saskatchewan, trends, prescriptions, children, adolescents

Abstract

Objectif :

La a recherche est nécessaire pour clarifier et améliorer notre compréhension des questions d’applicabilité et d’innocuité concernant le traitement aux antidépresseurs (AD). Nous avons exploré la tendance à long terme de la dispensation d’AD pédiatriques à l’aide des données provinciales d’une population du Canada.

Méthodes :

Des données sur 22 AD ont été extraites des fichiers de données administratives sur les services externes du ministère de la Santé de la Saskatchewan. Les données couraient sur 9 années triennales de 1983 à 2007, une période de 24 ans, pour les personnes de 0 à 19 ans de la population générale. Des analyses descriptives ont été utilisées.

Résultats :

En 1983, 5,9 par 1000 de population âgés de 0 à 19 ans se sont fait dispenser au moins 1 AD, ce qui a diminué à 5,1 par 1000 de population en 1989, puis qui a augmenté à 15,4 par 1000 de population en 2007, l’augmentation étant plus lente après 2004. Plus d’AD ont été dispensés aux deux sexes à compter de 1989 et après, les filles étant les plus grandes utilisatrices. Le taux d’utilisation des AD s’est accru significativement avec l’âge, et cette tendance est devenue plus marquée après 1998. Les médecins de famille étaient les principaux prescripteurs et leurs ordonnances ont augmenté significativement de 1989 à 2004 pour diminuer en 2007. L’utilisation des inhibiteurs spécifiques du recapture de la sérotonine (ISRS) constitue la principale raison de l’augmentation. Le nombre de prescriptions d’AD par patient a aussi augmenté.

Conclusions :

La croissance de la prévalence de l’utilisation d’AD chez les enfants et les adolescents a été largement causée par l’utilisation des ISRS. La possibilité de problèmes d’innocuité induits par l’utilisation d’AD chez les enfants et les adolescents, et différents modèles de pratique des médicaments suggèrent que la formation continue est justifiée.

Since researchers in the 1950s discovered the first ADs, TCAs, and MAOIs, a wide variety of ADs have become available and commonly prescribed to children and adolescents for depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders.1 The diversity of ADs allows clinicians to individualize treatment decisions for psychiatric symptoms, as well as to avoid potential side effects.2 Increased use of ADs for youth has been reported over decades in the United Kingdom, Italy, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United States.3–5 SSRIs have been the major contributor to this upward trend.3,6

Like all medications, ADs warrant concerns in terms of efficacy, tolerability, and safety.7 Generally, ADs have several side effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, fatigue, and sleepiness. Consequences of these side effects may adversely impact patients’ compliance and thereby influence outcome, and increase risk of morbidity and mortality.7

There have been further concerns expressed about the safety issue of ADs in pediatric patients.8–10 In 2004, drug regulatory agencies in the United States (Food and Drug Administration), Canada (Health Canada), and the United Kingdom (Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency) released warnings on ADs in pediatric patients, including suicidality, violence, aggression, mania, and other abnormal behavioural changes.11 Epidemiologic studies on trends of AD use in children and adolescents have been conducted to examine the influence of warnings on the use of ADs. Generally, prescriptions of SSRIs (except fluoxetine, which remained stable) decreased during 2003 to 2005, but increased afterwards.6,12–14 Notably, there has been significant national variability in patterns of psychotropics practice, owing to the introduction of new drugs, controversies over which drugs are better and more effective, different drug regulations, drug safety, cultural meaning of drug treatment in pediatric populations, and each country imprinting its own particular culture.15,16

Recently, Tsapakis et al17 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing responses to ADs and placebo in youth with depression. They concluded that most ADs, with the exception of fluoxetine, provided only limited efficacy in adolescent depression. Although clinical trials generally could provide better quality evidence than other study designs, short-term follow-up and small sample size limit the use of clinical trials in exploring trends of using pharmaceuticals. Health policy experts have suggested that existing health record databases should be studied to identify early warnings of adverse side effects of drugs, and to develop evidence-based health policy.18

Clinical Implications

There had been a substantial increase in the use of ADs among children and adolescents. The number of prescriptions per patient increased.

Family physicians played a major role in the use of ADs, but their role decreased after 2004.

Continued emphasis on training and education in the use of pediatric ADs is warranted.

Limitations

Data used was multiple cross-sectional.

The analysis of variables related to AD prescription is restricted, due to the existing variable limitation in the data source.

Data analyzed was for the Saskatchewan population, and may not be generalizable to other provinces in Canada.

Given the widespread use of ADs, the possibility of suicidality induced by ADs among children and adolescents, and different patterns of medication practice, data on the long-term trend of pediatric AD use in a general population are needed. In our study, we aimed to examine trends in pediatric AD use in general and in population subgroups over a 24-year period in a Canadian provincial population.

Methods

Context

Provincial governments in Canada take the responsibility of most health services delivered within their provinces. Although the precise range of services may vary by province, these services include almost all hospital and physician services, as well as a significant proportion of nursing home care, prescription drug subsidies, and public health.19 Saskatchewan is a prairie province, which has a total area of 651 900 square kilometres. The Saskatchewan population has remained relatively constant at around 1 million, and about 50% of the population live in the cities of Saskatoon and Regina. The government of Saskatchewan provides most health services delivered within the province. One byproduct of the services is extensive linkable health care use data files that are feasible for research use.20 The Saskatchewan population of children and adolescents (excluding registered First Nations) decreased from 309 385 in 1983 to 248 645 in 2007. There were consistently more males than females during the 24-year period. The proportions of younger age groups among children and adolescents decreased, whereas the proportion of older adolescents increased during the study period (online eAppendix 1).

Data Source

The data used were from the outpatient prescription drug data files of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. The detailed AD dispensing information for patients had been recorded in the drug file. The data released to researchers by the provincial Ministry of Health are subject to restraints and dummy identification to ensure confidentiality. These are anonymous administrative data; therefore, no ethics board approval is required for this type of study. The data include information for all beneficiaries eligible for prescription drug benefits. All Saskatchewan residents are eligible for prescription drug benefits except those who receive these benefits from the federal government (for example, veterans for service-related illnesses and registered Indians, about 10% of the provincial population). This constitutes covered population. The cross-sectional data were organized for 9 triennial years from 1983 to 2007. Data analyzed here are population-based.

Measures

For our study, the detailed information on 22 ADs, categorized into subclasses, prescribed by physicians, and dispensed by a community pharmacy, was extracted from the prescription drug database. The data documented individual prescriptions during a calendar year and included information on sex, age, AD drug category, and prescriber specialty. The 4 subclasses of ADs analyzed were SSRIs, MAOIs, TCAs, and other ADs (details on the drugs covered are shown in online eAppendix 2).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate rates of pediatric AD use in general and for subgroups. The age distribution of the total 9 years covered youth population was used as a standardization reference. The age-specific dispensing rates for each individual year were then calculated. The age-standardized dispensing rates for all study years were then computed, based on the age distribution of the standardized population and age-specific dispensing rates. Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 19.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

There were 1814 children and adolescents in Saskatchewan (5.9 per 1000 population of the covered children and adolescents aged 0 to 19) who received at least 1 prescription for ADs in 1983. The overall AD use prevalence rate in this age range decreased to 5.1 per 1000 population in 1989, then gradually increased to 15.4 per 1000 population in 2007. This was a 1.61-fold increase from 1983.

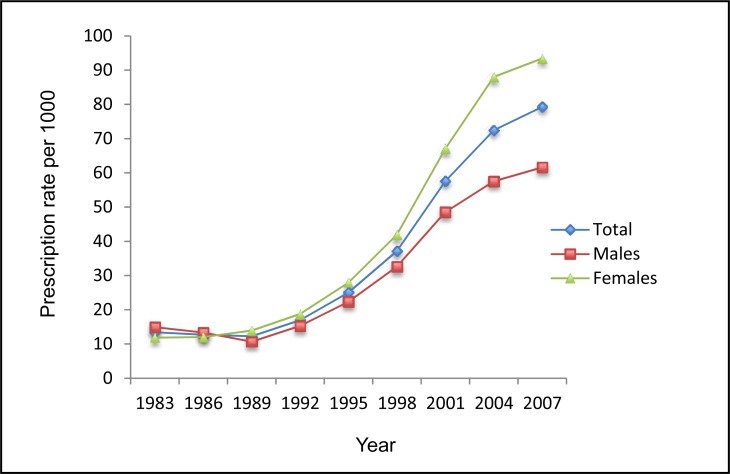

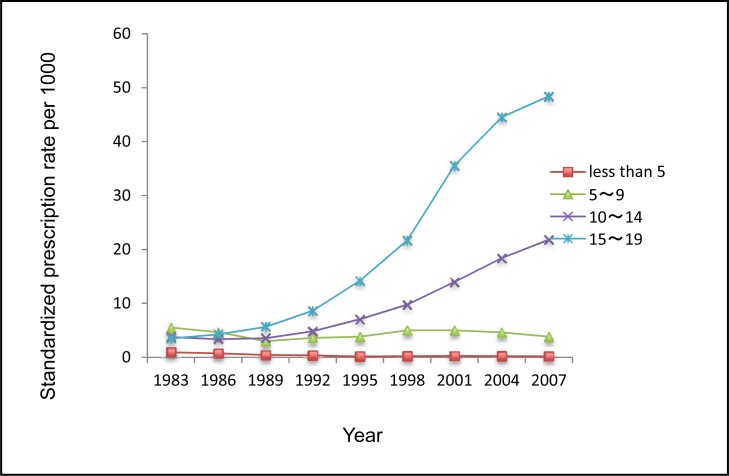

Figure 1a shows trends in numbers of dispensed ADs per 1000 children and adolescents in Saskatchewan from 1983 to 2007 (24 years). The number of dispensed AD prescriptions was 4156 in 1983, and it significantly increased to 19 715 in 2007. The rate of dispensed ADs among children and adolescents was 13.43 per 1000 in 1983, decreased to 12.27 per 1000 in 1989, and gradually increased to 79.29 per 1000 in 2007. Figure 1b presents standardized rates of dispensed ADs for different age groups. It shows that

the rate of AD use significantly increased among those aged 10 to 14 and aged 15 to 19;

this increasing trend became more pronounced during the 1998 to 2007 period;

the rate of ADs dispensed to those aged 5 to 9 fluctuated during the study period, and consistently decreased after 2001; and,

there was a decrease in the rate of dispensed ADs among those aged less than 5 years old.

Figure 1a.

The rate of ADs dispensed to children and adolescents aged 0 to 19 by sex, Saskatchewan, 1983 to 2007

Figure 1b.

The rate of ADs dispensed by age groups standardized to the total of 9 years in Saskatchewan covered youth population, 1983 to 2007

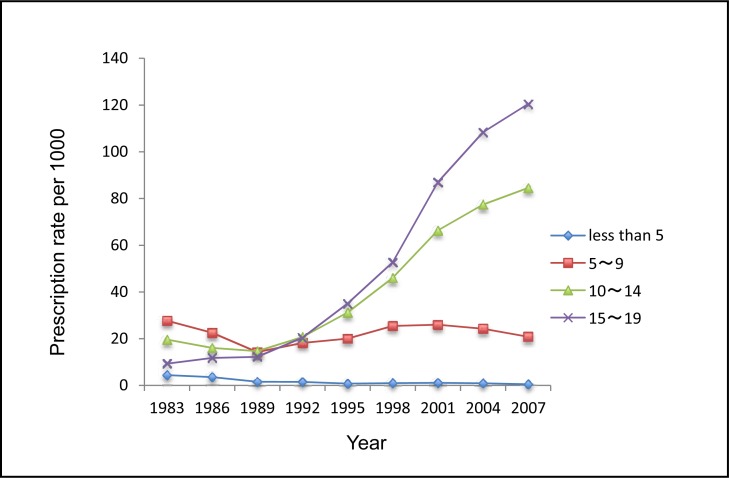

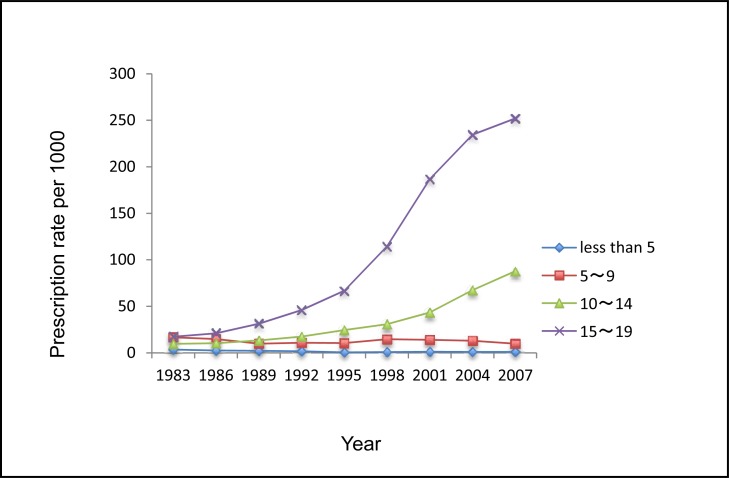

Compared with males, females received fewer ADs in 1983 and 1986. Both sexes used more ADs from 1989 onwards, and females were the heavier AD users. Adolescents aged 15 to 19 years were the major age group of AD users, and their use increased substantially from 1998 onwards. There were consistent increasing trends in use for adolescents aged 15 to 19 and those aged 10 to 14 in both males and females. Notably, the use of ADs decreased during 2004 to 2007 for children aged 5 to 9 (Figure 2a and 2b).

Figure 2a.

The rate of ADs dispensed to male children and adolescents aged 0 to 19 by age, Saskatchewan, 1983 to 2007

Figure 2b.

The rate of ADs dispensed to female children and adolescents aged 0 to 19 by age, Saskatchewan, 1983 to 2007

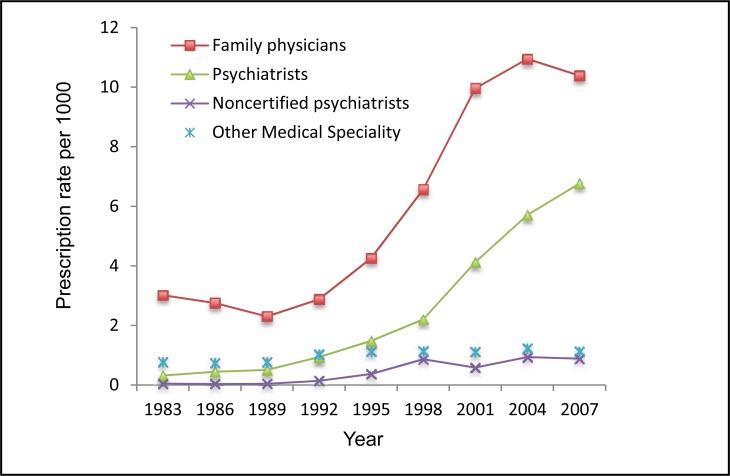

Family physicians were the major prescribers, and their prescriptions significantly increased from 1989 to 2004 and decreased in 2007. Psychiatrists were the second major group, and their prescriptions consistently increased over the 24-year study period. The rate of dispensed ADs prescribed by other medical specialties also slightly increased. The rate of ADs prescribed by noncertified psychiatrists (physicians with psychiatric training, but who have not completed examinations for certification and who are allowed to practice with a specific license) significantly increased in 1998 and remained at a higher level afterwards, compared with 1983 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The rate of ADs dispensed to children and adolescents aged 0 to 19 by medical specialty, Saskatchewan, 1983 to 2007

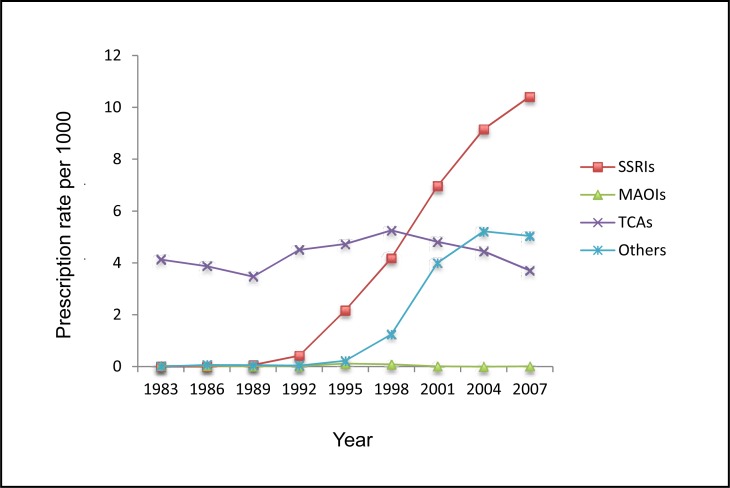

The use rate of SSRIs significantly increased since their introduction. Again, the rate of other AD use also rose, but had slightly decreased in 2007. In contrast, the MAOIs dispensing rate remained constant at a very low level. More fluctuations were observed in the rate of TCAs. Both TCAs and other ADs experienced a decrease in use after 2004. There was a dramatically decreasing trend in the usage of TCAs for children aged younger than 9 years old. Conversely, adolescents aged 15 to 19 were dispensed an increasing number of TCAs during the study period. In general, females were dispensed more TCAs over time (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The rate of dispensed ADs to children and adolescents by subclass, Saskatchewan, 1983 to 2007

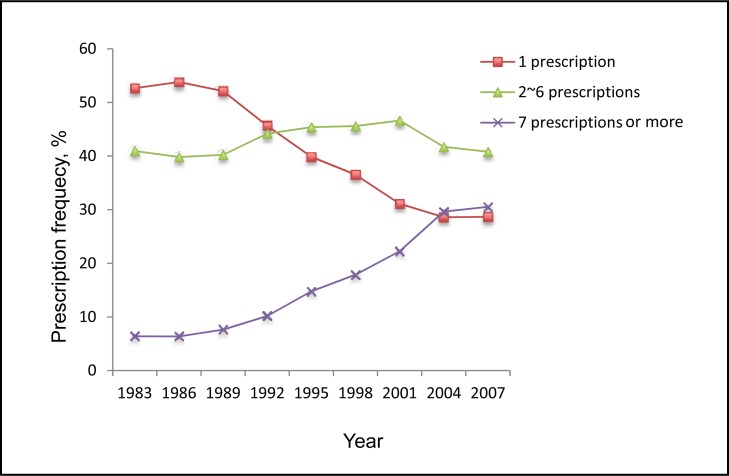

Figure 5 shows percentages of pediatric patients who were dispensed different numbers of ADs during the study period. There was an increasing trend in the percentage of those having 7 or more ADs dispensed per year, whereas a decreasing trend was observed in the percentage of those who were dispensed a single AD in a given year. The percentage having 2 to 6 prescriptions per year fluctuated over the 24-year period. Children and adolescent patients were dispensed more ADs per year over time regardless of sex. The percentages of dispensed ADs used by adolescents aged 15 to 19 dramatically increased in all prescription groups. Notably, the percentage of single prescriptions per year consistently and significantly decreased for both males and females. The percentages of only 1 AD per year dramatically decreased over time in all age groups (except adolescents aged 15 to 19). Family physicians were the major group to prescribe single ADs annually to pediatric patients, but their role had decreased over time. In contrast, the percentage of single ADs prescribed by noncertified psychiatrists was on the rise over the study period.

Figure 5.

The percentage of pediatric patients who were dispensed different numbers of ADs, Saskatchewan, 1983 to 2007

Discussion

In 1983, 5.9 per 1000 population aged 0 to 19 were dispensed at least 1 AD prescription, this decreased to 5.1 per 1000 in 1989, and then increased to 15.4 per 1000 in 2007, with a slower increase after 2004. Both sexes received more ADs from 1989 onwards, with females being the heavier users. The rate of AD use significantly increased with age, and this trend became more pronounced after 1998. Family physicians were the major prescribers and their prescriptions significantly increased from 1989 to 2004 and decreased slightly at 2007. The use of SSRIs was the major reason for this increase. Pediatric AD use became more frequent, as an increase in the percentage of patients with 7 or more prescriptions per year, whereas the percentage of 1 AD prescription dispensed per year decreased.

Evidence shows that mental disorders, especially depression, are being more frequently diagnosed among children and adolescents. Epidemiologic studies have found that mood and anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents, and are likely to be chronic and increase vulnerability to other diseases.21,22 A population-based study on children and adolescents had shown that those who were growing up in the 1990s had a 1 in 6 chance of getting a psychiatric disorder and the rate increased to 1 in 3 by the age of 16.23

Costello et al24 systematically conducted a meta-analytic study on the prevalence of depression between 1965 and 1996, and found that the prevalence of depression was 2.8% for those aged under 13, 5.9% for girls aged between 13 to 18, and 4.6% for boys aged 13 to 18. O’Neil et al25 in their review suggest that community and clinical studies have shown that a range of 9.0% to 47.9% of adolescents had comorbidity between internalizing disorders and substance use. Recently, Merikangas et al26 reviewed the magnitude of mental disorders in children and adolescents; despite variation in the results across the world, they concluded that about one-fourth of youth had a mental disorder in the past year, and one-third during their lifetime.

The safety issue of ADs in children and adolescents has been studied, but the efficacy of these drugs in juvenile depression has not been explicitly studied. More importantly, although CBT has been widely seen as an evidence-based treatment in children and adolescents, and has been considered as the most appropriate treatment for those who suffer from mild mental disorders,27 pharmacotherapy, and in particular ADs, may be an alternative or adjunct to CBT for more severe cases.28

Consistent with studies conducted in Quebec,29 Taiwan,30 the United States,31 the trend of AD use in children and adolescents has increased since the late 1990s. This trend was mainly a result of the increased use of SSRIs and other ADs. Our study found that the rate of pediatric use of ADs in Saskatchewan was 5.9 per 1000 in 1983, decreased in 1989, and then increased to 15.4 per 1000 in 2007. Pediatric AD use of children and adolescents in Taiwan increased during 1997 to 2005 from 2.7 per 1000 to 4.7 per 1000.30 The US rates increased from 13 per 1000 in 1997 to 18 per 1000 in 2002.31 Caution has to be paid when comparing the rate of pediatric AD use among studies for 3 reasons: studies were conducted at different time periods; characteristics of subjects varied by study; and insurance coverage of ADs differed.

Regulatory warnings resulted in a temporal decline in pediatric AD use during 2003 to 2005, but the use of ADs rebounded afterwards.10,32,33 This phenomenon could be explained by the following: clinicians were influenced by regulatory warnings in terms of making psychiatric diagnosis and offering prescriptions, and further studies on safety issues of ADs did not find evidence to support suicidal and violent acts as induced by ADs in youth,34 the influence of those warnings on clinicians was short-term. Our study found that a slower increase of pediatric AD use after 2004, which is in line with the trends in SSRI use in pediatric patients reported by a Quebec study29 and a Taiwanese study,30 and a decrease in the rate of ADs dispensed by family physicians after 2004, which may indicate that they were influenced by the warnings.

Our study also observed the prevalence of pediatric AD use increased with age. The increasing trend in use from 1983 to 2007 was most pronounced in the adolescent group (aged 15 to 19), and their use getting more frequent; this is also true for other studies.3,4,8,35 Adolescents are more likely to be judged to suffer with depression, anxiety, and other psychological difficulties, compared with children. The substantial increasing use of SSRIs is consistent with an increasing number of adolescent psychiatric patients.36

Females were more likely to use ADs in our study. Inconsistent findings on the role of sex in pediatric AD use have been reported.29,30 The discrepancy may be explained by the prevalence of psychiatric disorders varying between the sexes at different ages, and by structural differences in the proportions of males and females at different ages across studies.

Notably, the use of TCAs remained fairly constant over the study period. There was a dramatically decreasing trend in the usage of TCAs for those aged younger than 9 years. Conversely, adolescents aged 15 to 19 were dispensed an increasing number of TCAs. In addition, our study found that TCA use was more frequent in adolescents. It was likely that TCAs were used to treat psychiatric problems in this age group. Though one might consider TCAs prescribed for physical problems, such as bedwetting, we found a dramatically decreasing trend in the usage of TCAs for those aged younger than 9 years.

Family physicians played the major role in AD prescribing, followed by psychiatrists. However, there was a decrease in the prescription rate of ADs by family physicians after 2004. This phenomenon may be explained by the following: family physicians may be more influenced by the regulatory warnings; or the prescribing of ADs in children and adolescents shifted from generalists to psychiatric specialists,37 as we observed the rate of ADs dispensed by psychiatrists consistently increased during the 24-year period. The number of AD prescriptions dispensed per patient also increased, which parallels findings from the United States.38

Several findings from our comparison of AD use across subgroups warrant further attention. First, the effectiveness and appropriateness of frequently used ADs should be examined. Second, family physicians played a major role in AD prescriptions; therefore, continuing training and education on their use of ADs should be reinforced. Third, given the dramatic increase of SSRI use, research should be strengthened on the effectiveness and safety of individual SSRIs, and should help to identify the relative safety and balance of risks for pediatric patients.

Our study has some limitations. First, the range of variables in the data analyzed limits our ability to explore roles of other variables that may influence use. Second, data only had categorical information on the subclasses of ADs, data on specific ADs were not retrieved. Third, since our study only had one study point after 2004, the trend of pediatric AD use after regulatory warning needs to be reexamined with further post-2004 data.

Conclusions

Saskatchewan experienced an increasing trend in pediatric AD use from 1983 to 2007. The use of SSRIs significantly contributed to the trend. Family physicians and psychiatrists were the major prescribers. AD use increased with age, and the number of prescriptions per patient became more frequent. Given the use of ADs had dramatically increased, the possibility of safety issues induced by AD use among children and adolescents, and different patterns of medication practice, continuing education is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Dr Meng was funded by the Saskatchewan Research Foundation as a postdoctoral fellow. A Canadian Foundation for Innovation Leaders Opportunity Foundation Award (16995) was used to offset the costs involved in acquiring the data analyzed in the study.

Our study is based, in part, on de-identified data provided by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. The interpretations and conclusions contained herein do not necessarily represent those of the Government of Saskatchewan or the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health.

Abbreviations

- AD

antidepressant

- CBT

cognitive-behavioural therapy

- MAOI

monoamine oxidase inhibitor

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- TCA

tricyclic AD

References

- 1.Murray ML, de Vries CS, Wong IC. A drug utilisation study of antidepressants in children and adolescents using the general practice research database. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(12):1098–1102. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.064956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stahl SM. Selecting an antidepressant by using mechanism of action to enhance efficacy and avoid side effects. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 18):23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zito JM, Tobi H, de Jong-van den Berg LT, et al. Antidepressant prevalence for youths: a multi-national comparison. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(11):793–798. doi: 10.1002/pds.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fegert JM, Kolch M, Zito JM, et al. Antidepressant use in children and adolescents in Germany. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(1–2):197–206. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Middleton N, Gunnell D, Whitley E, et al. Secular trends in antidepressant prescribing in the UK, 1975–1998. J Public Health Med. 2001;23(4):262–267. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.4.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez JF, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, van Thiel GJ, et al. A 10-year analysis of the effects of media coverage of regulatory warnings on antidepressant use in the Netherlands and UK. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papakostas GI. The efficacy, tolerability, and safety of contemporary antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(Suppl E1):E03. doi: 10.4088/JCP.9058se1c.03gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volkers AC, Heerdink ER, van Dijk L. Antidepressant use and off-label prescribing in children and adolescents in Dutch general practice (2001–2005) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(9):1054–1062. doi: 10.1002/pds.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leon AC. The revised black box warning for antidepressants sets a public health experiment in motion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(7):1139–1141. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, et al. Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):884–891. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breggin PR. Recent US, Canadian and British regulatory agency actions concerning antidepressant-induced harm to self and others: a review and analysis. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2004;16:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijlaars LP, Nazareth I, Petersen I. Trends in depression and antidepressant prescribing in children and adolescents: a cohort study in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) PLOS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean AJ, Hendy A, McGuire T. Antidepressants in children and adolescents—changes in utilisation after safety warnings. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(9):1048–1053. doi: 10.1002/pds.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holstein SA, Knapp HR, Clamon GH, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of high dose lovastatin in subjects with advanced malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57(2):155–164. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zito JM, Safer DJ, de Jong-van den Berg LT, et al. A three-country comparison of psychotropic medication prevalence in youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parens E, Johnston J. Understanding the agreements and controversies surrounding childhood psychopharmacology. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsapakis EM, Soldani F, Tondo L, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in juvenile depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):10–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.031088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadman M. Experts call for active surveillance of drug safety. Nature. 2007;446(7134):358–359. doi: 10.1038/446358b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchidon G, O’Fee K. Health care in Saskatchewan: an analytical profile. Regina (SK): Canadian Plains Research Center and the Saskatchewan Institute of Public Policy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rawson NS, Downey W, Maxwell CJ, et al. 25 years of pharmacoepidemiologic innovation: the Saskatchewan health administrative databases. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2011;18(2):e245–e249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lack CW, Green AL. Mood disorders in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;24(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muris P. Treatment of childhood anxiety disorders: what is the place for antidepressants? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(1):43–64. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.642864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, et al. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jane Costello E, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Neil KA, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in youth: comorbidity, risk, temporal order, and implications for intervention. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(1):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):7–20. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/krmerikangas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapee RM, Schniering CA, Hudson JL. Anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence: origins and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:311–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center . Treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD) during the acute phase. Cincinnati (OH): Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tournier M, Greenfield B, Galbaud du Fort G, et al. Patterns of antidepressant use in Quebec children and adolescents: trends and predictors. Psychiatry Res. 2010;179(1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chien IC, Hsu YC, Tan HK, et al. Trends, correlates, and disease patterns of antidepressant use among children and adolescents in Taiwan. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(6):706–712. doi: 10.1177/0883073812450319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vitiello B, Zuvekas SH, Norquist GS. National estimates of antidepressant medication use among US children, 1997–2002. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):271–279. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000192249.61271.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz LY, Kozyrskyj AL, Prior HJ, et al. Effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescription rates, use of health services and outcomes among children, adolescents and young adults. CMAJ. 2008;178(8):1005–1011. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray ML, Thompson M, Santosh PJ, et al. Effects of the Committee on Safety of Medicines advice on antidepressant prescribing to children and adolescents in the UK. Drug Saf. 2005;28(12):1151–1157. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528120-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rihmer Z, Akiskal H. Do antidepressants t(h)reat(en) depressives? Toward a clinically judicious formulation of the antidepressantsuicidality FDA advisory in light of declining national suicide statistics from many countries. J Affect Disord. 2006;94(1–3):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoega H, Baldursson G, Hrafnkelsson B, et al. Psychotropic drug use among Icelandic children: a nationwide population-based study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(6):757–764. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delate T, Gelenberg AJ, Simmons VA, et al. Trends in the use of antidepressants in a national sample of commercially insured pediatric patients, 1998 to 2002. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(4):387–391. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemeroff CB, Kalali A, Keller MB, et al. Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(4):466–472. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]