Abstract

Objective:

Adolescent mothers are at increased risk of mistreating their children. Intervening before they become pregnant would be an ideal primary prevention strategy. Our goal was to determine whether psychopathology, exposure to maltreatment, preparedness for child-bearing, substance use disorders (SUDs), IQ, race, and socioeconomic status were associated with the potential for child abuse in nonpregnant adolescent girls.

Method:

The Child Abuse Potential Inventory (CAPI) was administered to 195 nonpregnant girls (aged 15 to 16 years; 54% African American) recruited from the community. Psychiatric diagnoses from a structured interview were used to form 4 groups: conduct disorder (CD), internalizing disorders (INTs; that is, depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or both), CD + INTs, or no disorder. Exposure to maltreatment was assessed with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, and the Childbearing Attitudes Questionnaire measured maternal readiness.

Results:

CAPI scores were positively correlated with all types of psychopathology, previous exposure to maltreatment, and negative attitudes toward child-bearing. IQ, SUDs, and demographic factors were not associated. Factors associated with child abuse potential interacted in complex ways, but the abuse potential of CD girls was high, regardless of other potentially protective factors.

Conclusions:

Our study demonstrates that adolescent girls who have CD or INT are at higher risk of perpetrating physical child abuse when they have children. However, the core features of CD may put this group at a particularly high risk, even in the context of possible protective factors. Treatment providers should consider pre-pregnant counselling about healthy mothering behaviours to girls with CD.

Keywords: child abuse, adolescents, girls, conduct disorder, internalizing disorders

Abstract

Objectif :

Les mères adolescentes sont à risque accru de maltraiter leurs enfants. Une intervention avant qu’elles ne soient enceintes serait une stratégie idéale de première prévention. Notre but était de déterminer si la psychopathologie, l’exposition à la maltraitance, la préparation à la procréation, les troubles liés à l’utilisation d’une substance (TUS), le QI, la race, et le statut socioéconomique étaient associés au potentiel de maltraitance dans l’enfance chez les adolescentes non enceintes.

Méthode :

L’inventaire de maltraitance potentielle (CAPI) a été administré à 195 jeunes filles non enceintes (de 15 à 16 ans; 54 % afro-américaines) recrutées dans la collectivité. Les diagnostics psychiatriques issus d’une entrevue structurée ont servi à former 4 groupes : le trouble des conduites (TC), les troubles internalisants (TIN, c’est-à-dire, le trouble dépressif, le trouble anxieux, ou les 2), TC + TIN, ou aucun trouble. L’exposition à la maltraitance a été évaluée par le Questionnaire des traumatismes subis durant l’enfance, et le questionnaire des attitudes envers la procréation mesurait l’état de disponibilité à la maternité.

Résultats :

Les scores au CAPI étaient positivement corrélés à tous les types de psychopathologie, à l’exposition antérieure à la maltraitance, et aux attitudes négatives envers la procréation. Le QI, les TUS et les facteurs démographiques n’étaient pas associés. Les facteurs associés au potentiel de maltraitance dans l’enfance interagissaient de façons complexes, mais le potentiel de maltraitance des filles du groupe des TC était élevé, sans égard à d’autres facteurs de protection possibles.

Conclusions :

Notre étude démontre que les adolescentes qui souffrent de TC ou de TIN sont à risque accru de perpétrer la maltraitance physique lorsqu’elles ont des enfants. Cependant, les caractéristiques de base du TC peuvent placer ce groupe à risque exceptionnellement élevé, même dans le contexte de facteurs possibles de protection. Les prestataires de traitement devraient envisager une consultation pré-grossesse sur les comportements maternels sains pour les jeunes filles soufrant du TC.

Young mothers are at increased risk for mistreating their children.1–5 An ideal strategy for protecting children from maltreatment would be early identification of young women who may be at risk for perpetrating abusive or neglectful behaviour so that these problems can be addressed before they begin raising children.6

Prior research has found that several characteristics of young mothers may increase the risk for child maltreatment. Many adolescents who become mothers meet criteria for psychiatric diagnoses, such as CD and INTs (depression and anxiety).7–11 Antisocial behaviour and INT have been identified as correlates or predictors for maltreatment, with consequent negative effects on offspring development.12–18 It is unclear whether the effects of psychiatric disorders are explained, in whole or in part, by SUDs that often co-occur.10,13,19,20

Adolescent mothers are also disproportionately victims of childhood abuse or neglect,21 which in and of itself, often predicts future maltreatment of offspring.22–27 Another factor is poor preparation for transition to motherhood, such as lack of knowledge about child development, negative attitudes toward the fetus, negative self-image about bodily changes of pregnancy and child-bearing, and negative feelings about one’s own mother.28–31

The demographics of adolescent mothers are not representative of the general adolescent population. The rate of teen births is inversely correlated with family income,32,33 and most babies born to adolescent mothers since 1991 have been in non-Hispanic black and Hispanic populations.34 An impoverished socioeconomic environment may contribute to abuse and neglect through increased parental stress.

Clinical Implications

Potential for physical child abuse toward offspring is increased in adolescent girls with CD and (or) INTs (that is, depressive or anxiety disorders).

Girls with CD are particularly at risk, often get pregnant during adolescence, and may not have the same protective factors as other girls.

Treatment programs for girls with CD should consider adding skills in readiness for motherhood and healthy parenting techniques, especially for girls who have been victims of maltreatment.

Limitations

Causal relations between the variables cannot be determined because of the cross-sectional design.

Effects of SUDs on physical child abuse potential could not be fully examined in our study as most of the girls with these disorders also had CD.

The CAQ has not previously been used in samples such as ours, thus the original psychometric properties described may not pertain to our study.

Most studies to date on child abuse potential in adolescents have investigated demographic factors and one other possible risk factor. However, it is important to consider the interacting effects of multiple factors.1,21,31,35,36 Many factors believed to be associated with abuse and neglect tend to co-occur, and it is important to examine whether a given factor is an important predictor of maltreatment when other factors are considered simultaneously.

Previous work has also studied young women who were pregnant or who were already mothers. In most studies, the mothers had already abused or neglected their children. By studying girls who are neither pregnant nor mothers, we could obtain information for early, primary prevention. Research using the CAPI37,38 can yield valuable information to estimate future risk for abuse and neglect in nonmothers. Two studies have used the CAPI with nonpregnant, nonparent teens. Adolescents who had been abused or witnessed violence had high scores on potential for child abuse.27 In addition, high CAPI scores were associated with placement in special education for disruptive behaviour.39 To our knowledge, no study has conducted a multifactorial investigation about whether psychopathology, previous exposure to maltreatment, mothering preparedness, or demographic factors contribute to the potential for child abuse in nonpregnant adolescent girls.

Our study was designed to examine associations between psychosocial and demographic factors and the potential for child abuse in adolescent girls who are not pregnant and not mothers. We hypothesized that psychopathology, exposure to maltreatment, negative attitudes toward child-bearing, SUDs, lower IQ, lower social class, and minority race would be associated with higher potential for physical child abuse.

Methods

Design and Participants

Our study used portions of the baseline assessment data from a longitudinal study of the effects of stress response system function on mental and physical health in adolescent girls. The longitudinal study recruited 15- to 16-year-old girls from the community through newspapers, radio advertisements, and posters that described symptoms of CD, depression, or anxiety, as well as soliciting girls without behaviour or emotional problems.

When families called in response to an ad, the girl and parent or guardian were given a brief description of the protocol and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria were age other than 15 to 16 years, Tanner Stage less than V, IQ of less than 70, psychosis, and a medical illness or medication that could affect the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. The last criterion was necessary for accomplishing the main goal of the longitudinal study. If girls did not meet exclusion criteria and wanted to participate, they received an intake appointment for themselves and a parent or guardian. Ninety-one per cent of the adult informants were biological parents.

Three hundred and fifty-one parent–girl dyads were interviewed for the main study, with 207 meeting inclusion criteria and agreeing to participate. Seven of these participants were already mothers and were excluded from our study. Five subjects had missing data on all self-report questionnaires owing to computer problems. They comprised less than 5% of the sample, thus they were excluded from these analyses. The final sample for analysis was n = 195.

Protocol and Instruments

Written informed consent was obtained from the parent and assent obtained from the girl. The girl and parent were interviewed separately, but concurrently. Transportation costs were provided and each dyad half received $20 for the interview. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and The Ohio State University.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable was physical child abuse potential, measured by the CAPI.38,40 We chose to study physical child abuse because it is the most common type of abuse.41 Note that from this point forward in our paper, when we use the term child abuse, we are referring to physical child abuse. The CAPI is a 160-item forced choice questionnaire originally used to predict child abuse behaviour in adults. Items include: “Spanking is the best punishment” and “I do not like most children.” A higher score indicates greater potential for physical abuse. It has excellent internal reliability and test–retest reliability.37,38 In samples of abusive parents, sensitivity was 80% and specificity was 90%.40

Although developed for adults, it has been used extensively with adolescent parents,31,35,39,42 pregnant adolescents,21 and in nonpregnant and nonparent female and male teens.27,31,38 The psychometric properties when used in adolescents have been questioned, particularly with the use of the clinical cut points and sensitivity and specificity.43 Adolescents also have higher mean and median scores than adults.5,44 Therefore, as recommended by Blinn-Pike and Mingus,44 we used the scale score rather than the clinical cut point for adults.

Independent Variables

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined from the computer-assisted National Institute of Mental Health DISC-IV, Parent and Youth Versions.45,46 This structured interview assesses the presence of all DSM-IV Axis I disorders. Test–retest reliability ranges from 0.43 to 0.96 for parental report and 0.25 to 0.92 for youth report. Validity data on the entire DISC-IV are not available, but validity of the previous version was tested and shown to be acceptable.47 Other research indicates excellent external validity of the DISC-IV diagnoses for CD and ODD in comparison with youth daily behaviour ratings.48

Based on concerns about the validity of using the aggression and age of onset DSM-IV criteria to diagnose female CD,49 we modified the DISC slightly, as we have done in our previous studies of CD in girls. First, we rephrased the question on fighting to read: “Do you often get into fights?” rather than “Do you often start fights?” Second, our diagnostic algorithm requires that antisocial behaviours be demonstrated for at least 1 year before the interview, instead of onset before age 13.

Diagnoses were made based on meeting criteria from the DISC–Youth or Parent Versions. Adolescents may not reveal behaviours to their parents (a false negative on DISC–Parent Version) or they may minimize their antisocial behaviour on report (a false negative on DISC–Youth Version).50 Therefore, we took all data as equally valid.51

Girls were placed into 1 of 4 diagnostic groups based on the results of the interview: no disorder (no lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder); INT (current major depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, but no externalizing disorders); CD; and CD+INT. The CD groups did not exclude the other externalizing disorders of ODD or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Alcohol, marijuana, or other drug abuse or dependence were combined into a single dichotomous variable (present or absent) called SUDs. SUDs was an exclusion variable for the no disorder group, but not for the other diagnostic groups. However, creating a super normal no disorder group would have compromised generalizability of our findings, thus girls were included if they had experimented with substances, defined as lifetime usage of less than 5 times (this is the cut point used in the DISC-IV).

Personal exposure to maltreatment was measured with the CTQ, a 28-item self-report inventory assessing 5 types of maltreatment: emotional, physical, sexual abuse, emotional, and physical neglect.52 The results are highly stable over time, show convergent and discriminate validity with other trauma instruments, and have good agreement with other sources of trauma data and validated in adolescents.52,53 The total score was used; higher scores indicated more exposure to maltreatment.

Preparation for transition to motherhood was assessed with the CAQ.54 This 76-item self-report instrument was designed for women at all reproductive stages, including those who have never been pregnant: they are instructed to imagine what they will feel like when they become pregnant.54 The higher the score, the more positive the attitudes.

Full-scale IQ was measured by the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test.55 A well-established brief test of intelligence, it yields a score for verbal and nonverbal aspects of intelligence. The instrument was standardized on a national representative sample.55 Split-half and test–retest reliabilities were good for children and adolescents. Construct and concurrent validity ranged from adequate to good. The composite score was used for analysis.

Demographic data were collected with a structured parent interview that included race and social class (scored with the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Social Status).56 The Hollingshead uses 4 factors (education, occupation, sex, and marital status) to compute social status. Once computed, social status is reported along 5 social strata, ranging from major business and professional to unskilled labourers and menial service workers. If 2 parents contributed equally to the girl’s support, the highest SES score was used.

Data Analysis

Data were checked for outliers and missing data; distributions of dependent variables were checked for normality. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and univariate statistics were used to examine the relations between the predictor variables and the dependent variable. General linear modelling was used to determine the best model to predict CAPI scores. Two-tailed tests were used and statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05. SPSS Statistics version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and STATA 9.057 were used for the analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The mean age of the sample was 15.8 years (SD 0.6 years). The sample comprised higher proportions of Caucasian (55%) than African-American girls (45%) and more girls from the lower 3 social classes (58%) than the upper 2 (42%). Although we recruited the sample for the main study so that the 4 psychopathology groups were about equal, for our study, some girls were excluded, as described above. Therefore, there were more girls in this study with CD+INT (31%) than any other group (CD 25%; INT 17%) and fewer in the no disorder group (27%). The mean CAPI score was 182.7 (SD 107.7). The mean total score on the CTQ was 42.8 (SD 16.3). The mean score on the CAQ was 211.4 (SD 30.4) and the mean full-scale IQ for the group was in the average range 95.2 (SD 12.9).

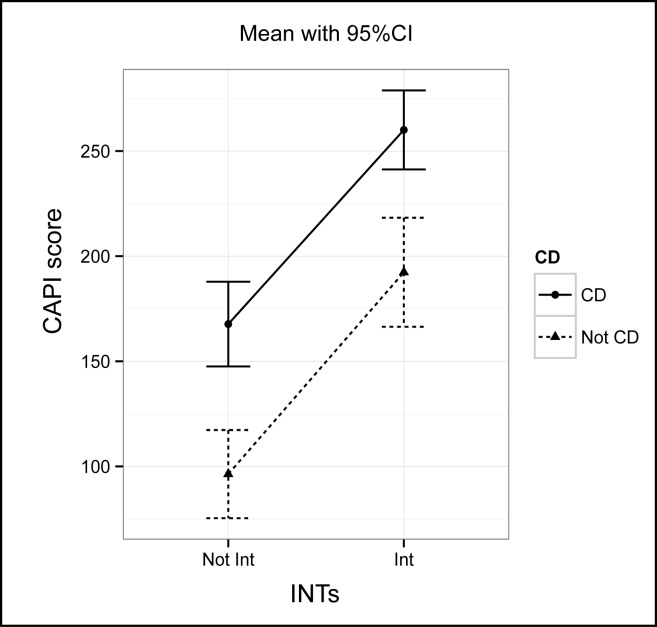

Nearly every independent variable was significantly associated with CAPI scores in the univariate analyses. Child abuse potential was associated with more negative attitudes toward childbearing (r = −0.33, P < 0.001), more exposure to maltreatment (r = 0.53, P < 0.001), lower IQ (r = −0.24, P = 0.001), and lower SES score (r = −0.22, P = 0.003). Both CD and INT were associated with greater child abuse potential, as depicted in Figure 1 (P < 0.001). The interaction between CD and INT was not significant (Figure 1). Race was not associated with CAPI scores (P = 0.08).

Figure 1.

Child abuse potential as a function of CD and INT

Girls with SUDs had greater child abuse potential (mean 231.4 [SD 104.9] for girls with SUDs, compared with 170.9 [SD 106.9] without SUDs, P < 0.001). However, 37 of the 38 girls who met criteria for SUDs also met criteria for CD. As girls with SUDs were, in effect, a subgroup of girls with CD, it was not surprising that SUD did not predict CAPI in multiple regression that also included CD. Girls with CD who also had SUDs had CAPI scores (mean 230.9 [SD 99.6]) that were not significantly higher than girls with CD without SUDs (mean 210.5 [SD 108.4], P = 0.32).

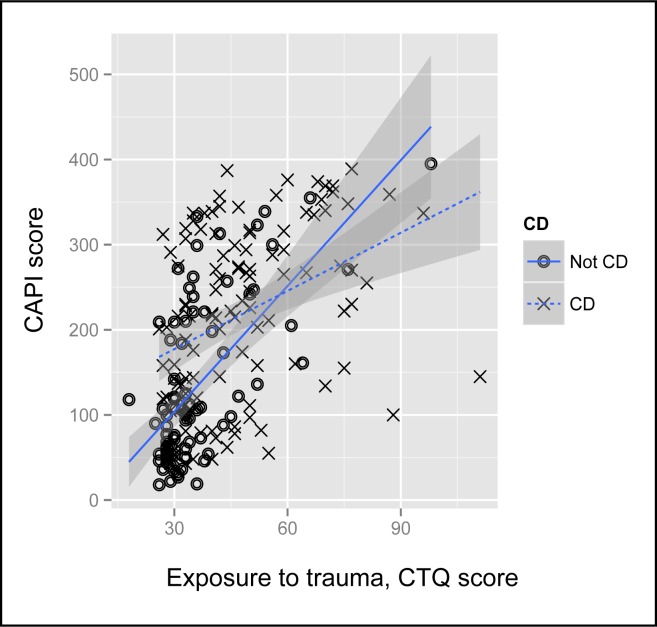

We examined variables significantly associated with CAPI (IQ, SES, attitudes toward child-bearing, exposure to maltreatment, CD, and INT) to determine interactions in association with child abuse potential. For each pair of these independent variables, we fit a regression with CAPI as the dependent variable and the 2 variables and their interaction as independent variables. There was a significant interaction between CAPI scores, SES, and exposure to trauma (P = 0.008). Girls exposed to maltreatment had significantly higher CAPI scores, whether they came from high or low social classes. There was also a significant interaction between CD and preparedness for mothering (P = 0.02), illustrating that positive attitudes had a substantially stronger protective effect among girls without CD than girls with CD (Figure 2). This was not the case for girls with INT.

Figure 2.

Child abuse potential as a function of CD and preparation for mothering, conditional mean (95%CI).

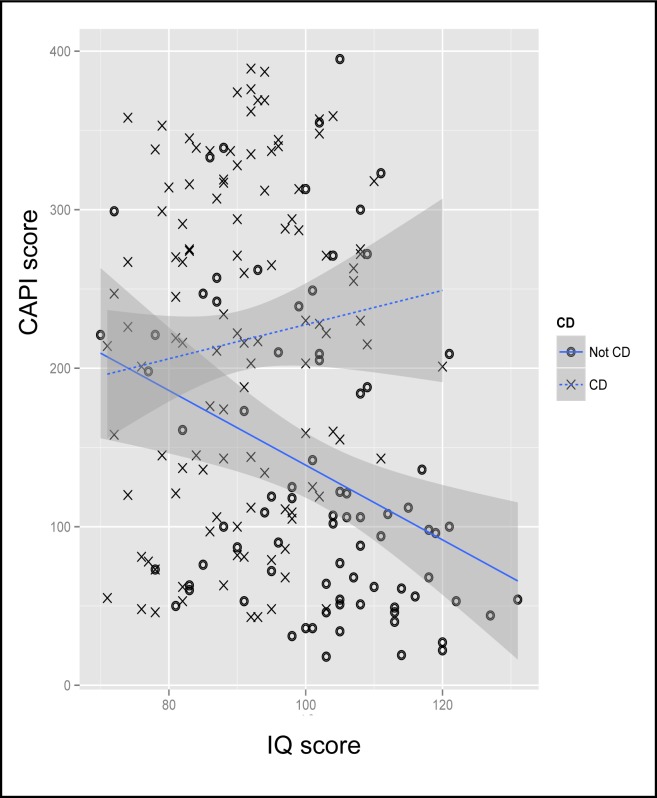

Figure 3 illustrates that girls with CD had higher potential for child abuse whether they had been exposed to trauma and neglect or not; this was not the case for the group without CD (P = 0.004). The same general finding was true for IQ levels: IQ had a protective effect from child abuse potential in the girls without CD, but not in those with CD (P = 0.02) (Figure 4). Neither of these relations were significant for girls in the internalizing disorders group.

Figure 3.

Child abuse potential as a function of CD and exposure to trauma, conditional mean (95%CI).

Figure 4.

Child abuse potential as a function of CD and IQ, conditional mean (95%CI).

We estimated multiple regression with child abuse potential as a dependent variable and the significant participant characteristics from the above analyses as covariates. Table 1 reports the model’s coefficients, in order of decreasing absolute value of the standardized regression coefficient (β). The most important correlate of child abuse potential was INT.

Table 1.

Predictors of child abuse potential scores in adolescent girlsa

| Variable | b | 95% CI | β | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | 72.61 | 48.95 to 96.28 | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| CD | 34.60 | 7.05 to 62.15 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| CTQ | 1.98 | 1.20 to 2.76 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| CAQ | −0.65 | −1.04 to −0.27 | −0.19 | 0.001 |

P < 0.001; R2 = 0.46

Additional statistically significant correlates were childhood exposure to maltreatment, childbearing attitudes, and CD. SES and IQ were not significantly associated with CAPI in the final model, and none of the interactions were statistically significant. This model explained an adjusted R2 of 46% of variance in CAPI scores.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the physical child abuse potential in 15- to 16-year-old nonpregnant adolescent girls was associated with having CD, INT, negative attitudes toward child-bearing, and childhood exposure to maltreatment. Many of our findings support previous studies in adolescent and adult mothers. This is important for 2 reasons. First, because we studied young women who were not yet mothers, our findings indicate that offspring maltreatment cannot be wholly due to economic disadvantages and social stressors that accompany adolescent motherhood—valuable information for prevention efforts. Second, we have replicated findings from studies of adolescent and adult mothers, which provides additional support for the hypotheses about etiologies of offspring maltreatment. Specifically, we have added to the literature linking child abuse potential with maternal psychopathology,12,13,21,58,59 maternal exposure to maltreatment,5,60 and preparedness for mothering.61

Despite several reports that maternal SUD is a major factor in child abuse or child abuse potential scores,13,19,20,62 our sample did not demonstrate this association once the effects of INT and CD were taken into account. However, our data are consistent with other studies demonstrating that the effect of maternal SUDs may be better explained by antisociality or depression.16,58 Approaches to the prevention of child abuse in young women should be tailored to the type of psychopathology that most affects the risk for maltreatment.

Our findings indicate that exposure to abuse or neglect puts one at risk for future abusive behaviour. Although disputed in the past,63 this association has been reported frequently in recent studies.17,64–66 Our findings are similar to those reported in one of the few studies using the CAPI with a nonpregnant, nonparent sample of teens.27

The effect of preparation for mothering, as measured by the CAQ, is consistent with other studies of this construct, although it has been measured in various ways.28,29,31,39 Our data highlight the need to continue prevention efforts that include education about mothering expectations and attitudes for at-risk young women.

The results indicate that factors associated with child abuse potential interact in complex ways. First, there was a significant interaction between CAPI scores, SES, and exposure to trauma. Girls exposed to maltreatment had significantly higher CAPI scores, whether they came from high or low social classes. Second, the child abuse potential of girls without CD varied substantially in response to the risk factor of childhood exposure to maltreatment and the potentially protective factors of higher IQ, higher SES, and good preparation for mothering. However, the child abuse potential of girls with CD tended to be high, regardless of the presence or absence of these risk and protective factors. This was not the case with girls who had INT.

We speculate several explanations for our findings on girls with CD. People with antisocial behaviour, including CD, are often narcissistic67,68 and may score higher on the CAPI because the items unintentionally measure this construct. They also are often physically aggressive, a characteristic, when present in young women, that is associated with high rates of physical injuries in offspring.68 Studies of parenting behaviours in young mothers with antisocial behaviour demonstrate interactions with their infants and children that are characterized by hostility, harshness, lack of empathy, and disinterest.9,14 Thus aggressive tendencies of CD may be driving CAPI scores higher in pre-mothers. CD is frequently comorbid with SUDs and it is possible that the combination of disorders increases child abuse potential. We could not fully test this hypothesis because almost all girls with SUDs had CD. However, arguing against this explanation is that the mean CAPI score for the CD and SUDs subgroup was no different than the CD and no SUDs subgroup. No matter which of these explanatory mechanisms are correct, protective factors appear to be less important for child abuse potential in girls with CD.

None of the interactions were statistically significant in the final model. We believe that this is due to our moderate sample size, but but these interactions should be reexamined in a larger sample.

Our findings present somewhat of a dilemma. If a girl had no disorder or had INT, factors such as exposure to trauma, preparedness for child-bearing, IQ, and social class moderated her child abuse potential. Current prevention programs could be effective in training young women who are not yet parents to become nonabusive mothers. Treatment of any psychopathology will undoubtedly improve outcomes. However, girls with CD seem to have a child abuse potential beyond the effects of these factors. If so, it suggests that we need a different preventive strategy for this population, particularly in light of the high rate of girls with antisocial behaviour who become young mothers.9,69–71

Despite much of the child abuse literature focusing on sociodemographic characteristics of mothers, we did not find an association between race and social class and CAPI scores in the final model. As we had nearly equal proportions of Caucasian and African-American girls in our study and the sample included the full range of social classes, we do not think our finding is due to a type II error. Our results indicate that risk profiling for child abuse cannot be accomplished with a model based on race or social class.

Several characteristics of our study limit the generalizability of our results. The primary issue is the design. All data were collected concurrently with instruments in which the time frames included the present. Therefore, we were unable to establish causal directions between the variables. The ideal design would be longitudinal, with the outcome being postnatal CAPI scores.

The second limitation is how we used the CAPI. Our data demonstrate that administering the CAPI to pre-parent teens is feasible and will yield a wide range of scores. However, because of concerns about the validity in adolescents of the standard adult clinical cut-point,38,43,44 we opted to use the scale score. While a prudent choice for research, prevention program planning is optimal when people are categorized according to a cut-off, which we cannot provide. More research is needed on the development of appropriate clinical cut-off scores in the adolescent population.

In summary, our study demonstrates that adolescent girls who are not yet mothers vary in physical child abuse potential. Higher scores for child abuse potential are best explained by internalizing and externalizing types of psychopathology, individual exposure to maltreatment, and negative attitudes toward child-bearing. The findings suggest that we should consider working with girls who have certain types of psychopathology, particularly CD, before they get pregnant to reduce potential for future abuse. Further, our data suggest that usual approaches to preventing abuse, such as education about child-bearing, may need to be supplemented or changed in some way for girls with CD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Joel Milner for advice on the use of the CAPI with nonparent adolescents and thank the participants for their time and effort.

Our study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (1R01MH066003–01A1; Pajer-PI).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

- CAPI

Child Abuse Potential Inventory

- CAQ

Childbearing Attitudes Questionnaire

- CD

conduct disorder

- CTQ

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

- DISC

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

- INT

internalizing disorder

- ODD

oppositional defiant disorder

- SES

socioeconomic status

- SUD

substance use disorder

References

- 1.Buchholz ES, Korn-Bursztyn C. Children of adolescent mothers: are they at risk for abuse? Adolescence. 1993;28(110):361–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stier DM, Leventhal JM, Berg AT, et al. Are children born to young mothers at increased risk of maltreatment? Pediatrics. 1993;91(3):642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Facts for families: when children have children [website] Washington (DC): American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 2004. [cited 2013 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/Facts_for_Families_Pages/When_Children_Have_Children_31.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florida State University Center for Prevention & Early Intervention Policy . Fact sheet: the children of teen parents. Tallahassee (FL): Florida State University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Paul J, Domenech L. Childhood history of abuse and child abuse potential in adolescent mothers: a longitudinal study. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(5):701–713. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stagner MW, Lansing J. Progress toward a prevention perspective. Future Child. 2009;19(2):19–38. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker-Lausen E, Rickel AU. Integration of teen pregnancy and child abuse research: identifying mediator variables for pregnancy outcome. J Prim Prev. 1995;16(1):39–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02407232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovacs M, Krol RSM, Voti L. Early onset psychopathology and the risk for teenage pregnancy among clinically referred girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(1):106–113. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassidy B, Zoccolillo M, Hughes S. Psychopathology in adolescent mothers and its effects on mother–infant interactions: a pilot study. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:379–384. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoccolillo M, Meyers J, Assiter S. Conduct disorder, substance dependence, and adolescent motherhood. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(1):152–157. doi: 10.1037/h0080220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Foster CL, et al. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders. II: Teenage parenthood. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(10):1405–1411. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Rutter M, et al. The caregiving environments provided to children by depressed mothers with or without an antisocial history. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1009–1018. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaffin M, Kelleher K, Hollenberg J. Onset of physical abuse and neglect: psychiatric, substance abuse, and social risk factors from prospective community data. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20(3):191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosquet M, Egeland B. Predicting parenting behaviors from antisocial practices content scale scores of the MMPI-2 administered during pregnancy. J Pers Assess. 2000;74(1):146–162. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA740110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conron KJ, Beardslee W, Koenen KC, et al. A longitudinal study of maternal depression and child maltreatment in a national sample of families investigated by child protective services. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(10):922–930. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinehart DJ, Becker MA, Buckely PR, et al. The relationship between mothers’ child abuse potential and current mental health symptoms: implications for screening and referral. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2005;32(2):155–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02287264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medley A, Sachs-Ericsson N. Predictors of parental physical abuse: the contribution of internalizing and externalizing disorders and childhood experiences of abuse. J Affect Disord. 2009;113(3):244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh C, MacMillan H, Jamieson E. The relationship between parental psychiatric disorder and child physical and sexual abuse: findings from the Ontario health supplement. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammerman RT, Kolko DJ, Kirisci L, et al. Child abuse potential in parents with histories of substance use disorder. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23(12):1225–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolock I, Magura S. Parental substance abuse as a predictor of child maltreatment re-reports. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20(12):1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelenko MA, Huffman L, Lock J, et al. Poor adolescent expectant mothers: can we assess their potential for child abuse? J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(4):271–278. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall LA, Sachs B, Rayens MK. Mothers’ potential for child abuse: the roles of childhood abuse and social resources. Nurs Res. 1998;47(2):87–95. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubowitz H, Black MM, Kerr MA, et al. Type and timing of mothers’ victimization: effects on mothers and children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):728–735. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig CD, Sprang G. Trauma exposure and child abuse potential: investigating the cycle of violence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):296–305. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green AH. Factors contributing to the generational transmission of child maltreatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(12):1334–1336. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atten DW, Milner JS. Child abuse potential and work satisfaction in day-care employees. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(1):117–123. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(87)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller TR, Handal PJ, Gilner FH, et al. The relationship of abuse and witnessing violence on the Child Abuse Potential Inventory with black adolescents. J Fam Violence. 1991;6(4):351–363. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosengard C, Pollock L, Weitzen S, et al. Concepts of the advantages and disadvantages of teenage childbearing among pregnant adolescents: a qualitative analysis. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):503–510. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field TM, Widmayer SM, Stringer S, et al. Teenage, lower-class, black mothers and their preterm infants: an intervention and developmental follow-up. Child Dev. 1980;51(2):426–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trad P. Mental health of adolescent mothers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(2):130–142. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haskett ME, Johnson CA, Miller JW. Individual differences in risk of child abuse by adolescent mothers: assessment in the perinatal period. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35(3):461–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colen CG, Geronimus AT, Phipps MG. Getting a piece of the pie? The economic boom of the 1990s and declining teen birth rates in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(6):1531–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickett KE, Mookherjee J, Wilkinson RG. Adolescent birth rates, total homicides, and income inequality in rich countries. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1181–1183. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin J, Hamilton B, Sutton P, et al. Births: final data for 2006. National vital statistics reports. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budd KS, Heilman NE, Kane D. Psychosocial correlates of child abuse potential in multiply disadvantaged adolescent mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(5):611–625. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelenko MA, Huffman LC, Brown BW, Jr, et al. The Child Abuse Potential Inventory and pregnancy outcome in expectant adolescent mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(11):1481–1495. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milner J. Assessing child abuse risk: the Child Abuse Potential Inventory. Clin Psychol Rev. 1994;14:547–583. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milner J. The Child Abuse Potential Inventory manual. Webster (NC): Psytec; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todd M, Gesten E. Predictors of child abuse potential in at-risk adolescents. J Fam Violence. 1999;14:417–436. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milner J, Ayoub C. Evaluation of “at-risk” parents using the Child Abuse Potential Inventory. J Clin Psychol. 1980;36:945–948. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198010)36:4<945::aid-jclp2270360420>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, executive summary. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lounds JJ, Borkowski JG, Whitman TL. The potential for child neglect: the case of adolescent mothers and their children. Child Maltreat. 2006;11(3):281–294. doi: 10.1177/1077559506289864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blinn-Pike L. Psychometric properties of CAP. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(3):148–149. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blinn-Pike L, Mingus S. The internal consistency of the child abuse potential inventory with adolescent mothers. J Adolesc. 2000;23(1):107–111. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA Study. Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwab-Stone M, Shaffer D, Dulcan M, et al. Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friman P, Handwerk M, Smith G, et al. External validity of conduct and oppositional defiant disorders determined by the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2000;28:277–286. doi: 10.1023/a:1005148404980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zoccolillo M. Gender and the development of conduct disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrews VC, Garrison CZ, Jackson KL, et al. Mother–adolescent agreement on the symptoms and diagnoses of adolescent depression and conduct disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(4):869–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychol Assess. 2004;16(3):330–334. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernstein D, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: a retrospective self-report. San Antonio (TX): Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernstein D, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, et al. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruble D, Fleming A, Stangor C, et al. Transition to motherhood and the self: measurement, stability, and change. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:450–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaufman A, Kaufman N. K-BIT. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test manual. Circle Pines (MN): American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. New Haven (CT): Yale University Department of Sociology; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 57.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 9. College Station (TX): StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hien D, Cohen LR, Caldeira NA, et al. Depression and anger as risk factors underlying the relationship between maternal substance involvement and child abuse potential. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson J, et al. A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spieker SJ, Bensley L, McMahon RJ, et al. Sexual abuse as a factor in child maltreatment by adolescent mothers of preschool aged children. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:497–509. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dukewich TL, Borkowski JG, Whitman TL. Adolescent mothers and child abuse potential: an evaluation of risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20(11):1031–1047. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Egami Y, Ford D, Greenfield S, et al. Psychiatric profile and sociodemographic characteristics of adults who report physically abusing or neglecting children. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:921–928. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaufman J, Zigler E. Do abused children become abusive parents? Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(2):186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pears KC, Capaldi DM. Intergenerational transmission of abuse: a two-generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(11):1439–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dixon L, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Browne K. Attributions and behaviours of parents abused as children: a mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (Part II) J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dixon L, Browne K, Hamilton-Giachritsis C. Risk factors of parents abused as children: a mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (Part I) J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frick PJ, Bodin SD, Barry CT. Psychopathic traits and conduct problems in community and clinic-referred samples of children: further development of the psychopathy screening device. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(4):382–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barry CT, Frick PJ, Killian AL. The relation of narcissism and self-esteem to conduct problems in children: a preliminary investigation. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(1):139–152. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Serbin LA, Peters PL, Schwartzman AE. Longitudinal study of early childhood injuries and acute illnesses in the offspring of adolescent mothers who were aggressive, withdrawn, or aggressive-withdrawn in childhood. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105(4):500–507. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Early conduct problems and later risk of teenage pregnancy in girls. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(1):127–141. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pajer K. What happens to “bad” girls? A review of the adult outcomes of antisocial adolescent girls. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(7):862–870. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]