Abstract

♦ Objective: In a number of patients, the antidiabetic drug metformin has been associated with lactic acidosis. Despite the fact that diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and that peritoneal dialysis (PD) is an expanding modality of treatment, little is known about optimal treatment strategies in the large group of PD patients with diabetes. In patients with ESRD, the use of metformin has been limited because of the perceived risk of lactic acidosis or severe hypoglycemia. However, metformin use is likely to be beneficial, and PD might itself be a safeguard against the alleged complications.

♦ Methods: Our study involved 35 patients with insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes [median age: 54 years; interquartile range (IQR): 47-59 years] on automated PD (APD) therapy. Patients with additional risk factors for lactic acidosis were excluded. Metformin was introduced at a daily dose in the range 0.5 - 1.0 g. All patients were monitored for glycemic control by blood sugar levels and HbA1c. Plasma lactic acid levels were measured weekly for 4 weeks and then monthly to the end of the study. Plasma and effluent metformin and plasma lactate levels were measured simultaneously.

♦ Results: In this cohort, the median duration of diabetes was 18 years (IQR: 14 - 21 years), median time on PD was 31 months (IQR: 27 - 36 months), and median HbA1c was 6.8% (IQR: 5.9% - 6.9%). At metformin introduction and at the end of the study, the median anion gap was 11 mmol/L (IQR: 9 - 16 mmol/L) and 12 mmol/L (IQR: 9 - 16 mmol/L; p > 0.05) respectively, median pH was 7.33 (IQR: 7.32 - 7.36) and 7.34 (IQR: 7.32 - 7.36, p > 0.05) respectively, and mean metformin concentration in plasma and peritoneal fluid was 2.57 ± 1.49 mg/L and 2.83 ± 1.7 mg/L respectively. In the group overall, mean lactate was 1.39 ± 0.61 mmol/L, and hyperlactemia (>2 mmol/L to 5 mmol/L) was found in 4 of 525 plasma samples (0.76%), but the patients presented no symptoms. None of the patients registered a plasma lactate level above 5 mmol/L. We observed no correlation between plasma metformin and plasma lactate (r = 0.27).

♦ Conclusions: Metformin may be used with caution in APD patients with insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes. Although our study demonstrated the feasibility of metformin use in APD, it was not large enough to demonstrate safety; a large-scale study is needed.

Keywords: Metformin, lactic acid, BMI, ESRD, acidosis, hypoglycemia

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide (1,2). Although DM is clearly associated with higher incidences of mortality and morbidity in ESRD patients and in patients on dialysis (3), few trials have examined treatment options for DM in these patient groups.

Metformin is recommended as the drug of first choice in the treatment of type 2 DM, and it has many established benefits (4,5). Its prescription in patients with ESRD is limited by concerns relating to a belief about the risk of lactic acidosis—concerns that have been perpetuated by numerous case reports in which metformin is implicated. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis is a rare complication, the incidence of which is estimated to be 3 cases per 100 000 person-years (6). A recent systematic review from the Cochrane Library concluded that there is no evidence to show that metformin is associated with an increased risk of lactic acidosis (7). The evidence cited for metformin-associated lactic acidosis derives mainly from published case reports or physician reports to drug safety committees (8,9). The observation of Roumie et al. (10) supports the first-line use of metformin in DM therapy and strengthens the evidence for its cardiovascular advantages compared with the sulfonylureas.

Fear of hypoglycemia is another obstacle that holds physicians back from prescribing metformin in ESRD patients (11). A recent nested case-control study using the UK-based General Practice Research Database showed that the risk of severe hypoglycemia as a result of insulin use in chronic kidney disease patients is greater than the risk of metformin-associated complications (6). Data related to metformin use in ESRD patients who are on peritoneal dialysis (PD) are scarce. Almost all the available data emanate from case reports that lack measurements of metformin concentrations in blood or peritoneal effluent.

The foregoing facts raise doubts about the pathogenetic significance of metformin with respect to lactic acidosis or hypoglycemia in ESRD patients who are on PD. In addition, several years ago, Hayat (12) suggested that PD is the best treatment for symptomatic metformin-induced lactic acidosis, especially in diabetic patients. Because of its efficiency, PD promotes removal of lactate and rapid restitution of acid-base balance. Hence, we hypothesized that PD may itself be a safeguard against lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients. A clear redefinition of the contraindications to metformin would enable more physicians to prescribe it within guidelines. We carried out the present work to evaluate the risk of metformin-associated lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia in an ESRD population with insulin-dependent DM who were receiving prescribed automated PD (APD) therapy.

Methods

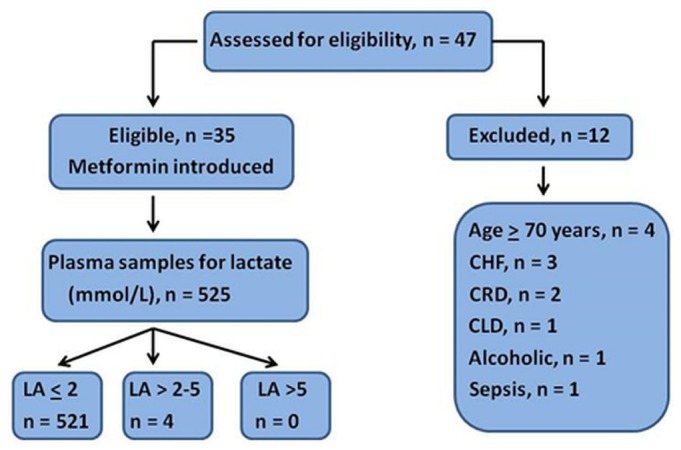

The study was conducted between September 2011 and August 2012 at King Fahd University Hospital, Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia, and it complied with the Helsinki Declaration. After written informed consent was obtained, 35 eligible ESRD patients [median age: 54 years; interquartile range (IQR): 47 - 59 years] with insulin-dependent type 2 DM were prospectively studied for a period of 4 weeks. Another 12 patients with additional risk factors for lactic acidosis (congestive heart failure, age 70 years or older, chronic respiratory disease, sepsis, alcohol use, liver disease) were excluded from the study (Figure 1). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study cohort.

Figure 1 —

Consort diagram demonstrating study design. CHF = chronic heart failure; CRD = chronic respiratory disease; CLD = chronic liver disease, LA = serum lactic acid.

TABLE 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Biochemical Characteristics of the Study Patients

All 35 enrolled patients were on APD. The dialytic prescription consisted of 1.36% and 2.27% glucose-based solutions (Dianeal: Baxter Healthcare SA, Castlebar, Ireland) for 9 hours overnight and 2 L 7.5% icodextrin (Extraneal: Baxter Healthcare SA) as the final fill for a day dwell in all patients. The total daily PD volume ranged between 10 L and 13 L, with a fill volume between 2.0 L and 2.5 L per cycle.

Of the 35 study patients, 25 were using insulin glargine, and 10 were using premix insulin. Metformin was introduced at a daily oral dose in the range 0.5 - 1.0 g (0.5 g daily being the minimum recommended therapeutic dose). Metformin concentrations in plasma and peritoneal effluent were measured at metformin introduction and at the end of the study. The therapeutic level of metformin was defined as a plasma concentration between 0.5 - 1.0 mg/L (13). Serum lactic acid was measured weekly for 4 weeks and then monthly until the end of the study. Lactate and metformin were both measured 8 hours after the fill for the day dwell. Hyperlactemia was defined as a serum lactate concentration exceeding 2 mmol/L and up to 5 mmol/L, and lactic acidosis was defined as a plasma lactate concentration exceeding 5 mmol/L and a venous pH less than 7.35 (14). Fasting blood sugar levels were measured at each PD clinic visit, and HbA1c was measured once every 3 months. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated for all patients at the beginning and end of the study.

Metformin Assay Technique

All metformin concentrations were measured in duplicate in the same laboratory using quantitative reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection and tandem mass spectrometry (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT, USA).

Lactate Assay Technique

Samples were collected from patients in a state of oral fasting and complete rest. Blood was collected in tubes containing sodium fluoride or potassium oxalate. The specimens were immediately chilled, and the plasma was separated within 15 minutes. If tests could not be performed immediately, the separated plasma samples were refrigerated at a temperature below 4°C while awaiting analysis. The kits used were LA Flex Reagent Cartridges for the Dimension Clinical Chemistry System (Siemens Healthcare, Malvern, PA, USA). Plasma lactate levels were considered normal when in the range 0.4 - 2.0 mmol/L.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as medians and IQRs (25th to 75th percentiles), and categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Nonparametric Spearman rank correlation was used to test continuous variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare groups. Values of p were not adjusted for multiple testing and should therefore be considered descriptive. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (version 20: IBM, New York, NY, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the patients. Women constituted 42.9% of the cohort, and 11.4% of the patients were smokers. The median duration of DM was 18 years (IQR: 14 - 21 years), and the median time on APD was 31 months (IQR: 27 - 36 months).

At metformin introduction and at the end of study, the median dose of insulin was, respectively, 15 U (IQR: 12 - 22 U) and 10 U (IQR: 10-14 U) for the patients using insulin glargine; it was 25 U (IQR: 22 - 30 U) and 18 U (IQR: 16 - 20 U) for the patients using premix insulin (p < 0.05, Table 2). Throughout the study period, median blood sugar in the cohort overall was 7.66 mmol/L (IQR: 5.44 - 8.05 mmol/L), and median HbA1c was 6.8% (IQR: 5.9% - 6.9%). Episodes of hypoglycemia (random blood sugar: 3.33 - 4.0 mmol/L) occurred in 3 patients (8.6%) and were managed successfully with dose modification.

TABLE 2.

Clinical Features of the Study Patients at Baseline and at Study End

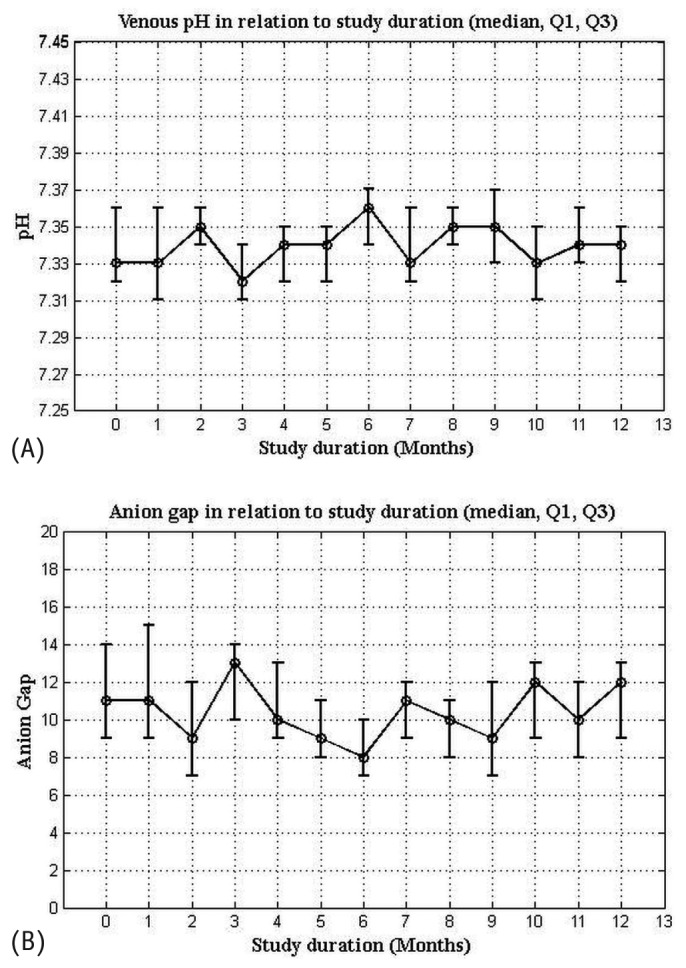

At metformin introduction and at the end of the study, median BMI was, respectively, 29.8 kg/m2 (IQR: 28.9 - 31.4 kg/m2) and 28.3 kg/m2 (IQR: 27.9 - 28.9 kg/m2, p < 0.05). Median Kt/V for all patients was 1.62 (IQR: 1.32 - 1.68). Table 2 shows Kt/V at metformin introduction and at the end of the study. Median creatinine clearance was 6.3 mL/min (IQR: 5.5 - 6.9 mL/min) at metformin introduction and 6.1 mL/min (IQR: 5.6 - 7.1 mL/min) at the end of the study (p > 0.05). At metformin introduction and at the end of the study, the median anion gap was, respectively, 11 mmol/L (IQR: 9 - 16 mmol/L) and 12 mmol/L (IQR: 9 - 16 mmol/L, p > 0.05), and the median pH was 7.33 (IQR: 7.32 - 7.36) and 7.34 (IQR: 7.32 - 7.36; p > 0.05; Table 2; Figure 2).

Figure 2 —

Median (A) serum pH and (B) anion gap in relation to study duration. Q1 = quartile 1; Q3 = quartile 3.

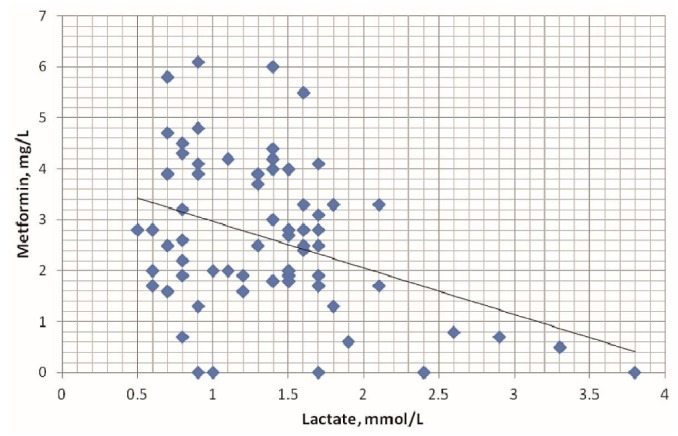

The mean metformin dose in the cohort was 0.84 ± 0.24 g daily (range: 0.5 - 1.0 g daily). Mean metformin concentrations in plasma and peritoneal effluent were 2.57 ± 1.49 mg/L and 2.83 ± 1.7 mg/L respectively. We distinguished 4 pragmatic categories of plasma metformin concentration: undetectable (5 samples, 7.1% of the assays); therapeutic range (0.5 - 1.0 mg/L; 5 samples, 7.1%); slightly to moderately elevated (>1.0 mg/L to 5.0 mg/L; 57 samples, 81.4%); and markedly elevated (>5.0 mg/L; 3 samples, 4.4%). Mean plasma lactate was 1.39 ± 0.61 mmol/L (range: 0.5 - 3.8 mmol/L). Hyperlactemia (>2 mmol/L to 5 mmol/L) was found in 4 of 525 (0.76%) plasma samples, but the patients presented no symptoms. No patient had a plasma lactate level exceeding 5 mmol/L. We observed no correlation between plasma metformin and plasma lactate (r = 0.27, Figure 3).

Figure 3 —

Relationship between plasma lactate and plasma metformin in the study patients, r = 0.27 (nonsignificant).

Discussion

This study of patients with insulin-dependent type 2 DM receiving metformin demonstrates the feasibility of metformin use in ESRD patients who are using APD as renal replacement therapy. To illuminate the concerns about the use of metformin in patients with reduced renal function, it is important to understand the metabolism of this drug. At routine doses of 500 - 1500 mg, metformin has an absolute oral bioavailability of 50% - 60% (15). Its molecular weight is 165.63. It is not protein-bound, and it therefore has a wide volume of distribution, with maximal accumulation in the wall of the small intestine. Undergoing no modifications in the body, metformin is eliminated unchanged by rapid kidney excretion (through glomerular filtration and, possibly, tubular secretion). Impaired kidney function slows elimination and may cause metformin accumulation, raising concerns about lactic acidosis (13). However, recent data and reviews of large databases have suggested increased use of metformin in individuals with diminished renal function, with no increase in the occurrence of lactic acidosis (6,13,16-19).

Phenformin, another biguanide, was removed from the market in 1977 because of several cases of fatal lactic acidosis. Many physicians therefore discontinue use of all biguanides whenever any increase in serum creatinine occurs. However, the chemical structure of phenformin is substantially different from that of metformin. Unlike metformin, phenformin can impair oxidative phosphorylation in the liver, thereby increasing lactate production by anaerobic pathways (7,20). Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis without altering lactate turnover or lactate oxidation (20), which was demonstrated in our study by the lack of correlation between plasma metformin and plasma lactate.

Stades et al. (8) strongly suggest that the association between lactic acidosis and metformin use is coincidental. No relationship could be established between lactate concentration, metformin concentration, and mortality. That lack of a relationship accords with the results of a well-documented case series recently published by Lalau and Race (21). The foregoing clinical data invalidate the hypothesis of a high lactic acid concentration in metformin users being primarily a result of the inhibitory effect of metformin on mitochondrial lactate oxidation (22,23). In both the Lalau and Race and the Stades reports, all but one of the cases had one or more risk factors that could have induced lactic acidosis even without metformin therapy (21). Stades et al.(8) found acute risk factors able to precipitate lactic acidosis in 46 of 47 cases analyzed, which emphasizes the subjectivity of the judgment (confirmed by a panel of experts in that study).

Remarkably, the severity of renal failure expressed as creatinine concentration was neither a risk factor for mortality nor correlated with lactic acid or metformin concentration. The recently published Cochrane review of 65 621 type 2 DM patients in comparative trials and cohorts showed that the incidence of lactic acidosis was comparable in metformin-treated and non-treated patients (24). Although adherence to contraindications for metformin use in type 2 DM might have resulted in a selection bias that could explain lower lactic acidosis rates (25,26), it must be noted that those contraindications are widely disregarded (27,28). Because no mortality attributable to metformin alone was reported, it is important that physicians become familiar with the range of other risk factors that contribute to lactic acidosis in patients with renal impairment treated with metformin (9). Why, then, does the idea that metformin is associated with fatal lactic acidosis persist?

First, a class effect of biguanides is suggested. Second, a positive publication bias for case descriptions of lactic acidosis in metformin users has fortified the “clinical impression.” Once a serious side effect has entered general medical opinion, expunging it is very difficult. The double-blind prospective randomized clinical trial necessary to test the specific issue of lactic acidosis may never be performed because of the immense size of the group needed to capture enough cases. In a recent large cohort study (51 675 patients), Ekstrom and his colleagues (31) demonstrated that, compared with insulin, metformin carries a lower risk for CVD and all-cause mortality, and compared with other hypoglycemic agents, it carries a slightly lower risk for all-cause mortality in pharmacologically treated patients with type 2 DM and varying levels of renal function. Ekstrom et al. also demonstrated that patients with renal impairment taking metformin had no increased risk of CVD, all-cause mortality, acidosis, or serious infection.

In our study, hyperlactemia (>2 mmol/L to 5 mmol/L) was found in only 4 of 525 plasma samples (0.76%), and no patient had a plasma lactate level above 5 mmol/L. The relation between metformin plasma concentration and lactic acidosis is not clear; we observed no correlation between plasma metformin and plasma lactate concentrations in the present study (r = 0.27, nonsignificant; Figure 3). The hyperlactemia observed in the 4 plasma samples was not necessarily a result of metformin accumulation. Unlike traditional hypoglycemic agents such as the sulfonylureas, insulin, and the thiazolidinediones, metformin does not increase body weight and does not cause hypoglycemia (30). In that regard, significant reductions in total body fat and visceral fat have been observed in metformin-treated women with pre-existing abdominal or visceral obesity (31). That reduction in visceral adipose tissue may have additional cardiovascular benefits in people treated with metformin (30,32,33). We also noticed a reduction in BMI (about 5%) in our metformin-treated patients. That observation agrees with findings in the original UK Prospective Diabetes Study (34), which showed a significant reduction in BMI [associated with a 39% risk reduction for myocardial infarction (p = 0.010) and a 36% risk reduction for total mortality (p = 0.011)] in metformin-treated patients compared with those using conventional dietary treatment. Furthermore, metformin has advantages over insulin and some types of insulin secretagogues: By decreasing excess hepatic gluconeogenesis without raising insulin levels, it rarely leads to significant hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy (6,34). Our results confirmed that profile, because only 8.6% of our patients experienced episodes of hypoglycemia (random blood sugar: 3.33 - 4.0 mmol/L), which were successfully managed with dose modification.

Although there is clear recognition that renal failure may be a risk factor for adverse events with metformin use, opinion diverges significantly across the globe regarding the optimal definition of “safety.” None of the various published guidelines discusses the use of metformin in patients who are on chronic PD, which raises the question “Can PD be a safety measure against the development of lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients?”

Ilabaca-Avendaño et al. (35) described 4 patients with chronic kidney disease and acute metabolic acidosis who were treated successfully with APD. Another paper published by Vaziri et al. (36) dealt with a subset of patients with severe lactic acidosis who did not respond to large amounts of intravenous sodium bicarbonate. A special bicarbonate-buffered dialysate was shown to effectively dialyze lactic acid and thus avoid hypernatremia and fluid overload. In the 4 patients studied, the diagnosis was confirmed by serum lactate concentrations. Similarly, Sheppard et al. (37) recommended PD as an effective intervention for removal of lactate from plasma. In our patients, the presence of metformin in peritoneal effluent at concentrations more or less equal to those in plasma (2.83 ± 1.7 mg/L and 2.57 ± 1.49 mg/L respectively) might confirm the conclusions of the earlier studies. Those clinical data are, to our knowledge, the first to demonstrate peritoneal removal of metformin, a non-protein-bound small molecule. No published animal model or clinical study has shown the effects of metformin, if any, on the peritoneal membrane. We therefore cannot speculate on any eventual impact of various PD solutions on metformin clearance or on the long-term effects of PD on the peritoneal membrane in the presence of metformin.

It is noteworthy that 85% of our patients presented with moderate or markedly raised metformin concentrations. Until a larger prospective study can clearly demonstrate the safety of metformin in APD patients, there is a need to monitor metformin concentrations in such patients when they are being treated with metformin.

Our study has some drawbacks. First, the number of patients was relatively small, and the reported data might underestimate incidents occurring in actual clinical practice. Second, the study lacked a control group. Third, as described earlier, the study cohort was a selected group of insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Finally, it should be remembered that, although emerging data suggest that metformin can be used in ESRD, distinctions have to be drawn concerning when, in routine practice, metformin can safely be used without putting patients at potential risk. On the other hand, our study has the strength of being the first of its kind to discuss the use of metformin in PD patients with type 2 DM. The study also discloses the relationship between metformin and plasma lactate concentrations in this group of patients.

Conclusions

Metformin can be used with caution in patients with insulin-dependent type 2 DM on APD therapy. Although our study has demonstrated the feasibility of metformin use in APD, it was not large enough to demonstrate safety; a large-scale study is needed. In addition, the reported data might underestimate the incidents that could occur in actual clinical practice. Further studies are needed.

Disclosures

The authors have no relationship with pharmaceutical companies or other entities such as employment contracts, consultancy, advisory boards, speaker bureaus, membership of Board Directors, stock ownership that could be perceived to represent a financial conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Abdul Rashid Qureshi, CLINTEC, Karolinska Institute, Sweden, for his valuable help in the statistical analysis. The authors also extend their sincere appreciation to all staff in the PD Unit and chemistry laboratory at King Fahd University Hospital, University of Dammam, for their remarkable help and support during the study.

References

- 1. McDonald S, Excell L, Livingston B, eds. The Thirty First Report: Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Adelaide, Australia: ANZDATA Registry; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. United States, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, US Renal Data System (USRDS). USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report. Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: USRDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, Leivestad T, Holdaas H, Sagedal S, Olstad M, et al. The impact of early-diagnosed new-onset post-transplantation diabetes mellitus on survival and major cardiac events. Kidney Int 2006; 69:588–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Ferrannini E, Holman RR, Sherwin R, et al. on behalf of the American Diabetes Association; European Association for Study of Diabetes. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:193–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Heine RJ, Holman RR, Sherwin R, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:1963–72 [Erratum in: Diabetes Care 2006; 49:2816-18] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodmer M, Meier C, Krahenbuhl S, Jick SS, Meier CR. Metformin, sulfonylureas, or other antidiabetes drugs and the risk of lactic acidosis or hypoglycemia: a nested case-control analysis. Diabetes Care 2008; 31:2086–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;:CD002967 [Review update] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stades AM, Heikens JT, Erkelens DW, Holleman F, Hoekstra JB. Metformin and lactic acidosis: cause or coincidence? A review of case reports. J Intern Med 2004; 255:179–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lalau JD, Race JM. Lactic acidosis and metformin therapy: searching for a link with metformin in reports of “metformin-associated lactic acidosis.” Diabetes Obes Metab 2001; 3:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roumie CL, Hung AM, Greevy RA, Grijalva CG, Liu X, Murff HJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of sulfonylurea and metformin monotherapy on cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:601–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nissen SE. Cardiovascular effects of diabetes drugs: emerging from the dark ages. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:671–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hayat JC. The treatment of lactic acidosis in the diabetic patient by peritoneal dialysis using sodium acetate: a report of two cases. Diabetologia 1974; 10:485–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scheen AJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics of metformin. Clin Pharmacokinet 1996; 30:359–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stacpoole PW, Wright EC, Baumgartner TG, Bersin RM, Buchalter S, Curry SH, et al. Natural history and course of acquired lactic acidosis in adults. DCA-Lactic Acidosis Study Group. Am J Med 1994; 97:47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McFarlane SI, Banerji M, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86:713–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lalau JD, Andrejak M, Morinière P, Coevoet B, Debussche X, Westeel PF, et al. Hemodialysis in the treatment of lactic acidosis in diabetics treated by metformin: a study of metformin elimination. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1989; 27:285–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vasisht KP, Chen SC, Peng Y, Bakris GL. Limitations of metformin use in patients with kidney disease: are they warranted? Diabetes Obes Metab 2010; 12:1079–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salpeter S, Greyber E, Pasternak G, Salpeter E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;:CD002967 [Review update] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mani MK. Nephrologists sans frontières: preventing chronic kidney disease on a shoestring. Kidney Int 2006; 70:821–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bando K, Ochiai S, Kunimatsu T, Deguchi J, Kimura J, Funabashi H, et al. Comparison of potential risks of lactic acidosis induction by biguanides in rats. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2010; 58:155–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lalau JD, Race JM. Lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients. Prognostic value of arterial lactate levels and plasma metformin concentrations. Drug Saf 1999; 20:377–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Czyzyk A, Lao B, Bartosiewicz W, Szczepanik Z, Orlowska K. The effect of short-term administration of antidiabetic biguanide derivatives on the blood lactate levels in healthy subjects. Diabetologia 1978; 14:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ofenstein JP, Dominguez LJ, Sowers JR, Sarnaik AP. Effects of insulin and metformin on glucose metabolism in rat vascular smooth muscle. Metabolism 1999; 48:1357–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salpeter S, Greyber E, Pasternak G, Salpeter E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;:CD002967 [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wiholm BE, Myrhed M. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis in Sweden 1977-1991. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 44:589–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stacpoole PW. Metformin and lactic acidosis. Guilt by association? Diabetes Care 1998; 21:1587–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Emslie-Smith AM, Boyle DI, Evans JM, Sullivan F, Morris AD. on behalf of the DARTS/MEMO Collaboration. Contraindications to metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes—a population-based study of adherence to prescribing guidelines [Abstract]. Diabetologia 1999; 42(Suppl 1):A3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holstein A, Nahrwold D, Hinze S, Egberts EH. Contraindications to metformin therapy are largely disregarded. Diabet Med 1999; 16:692–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ekstrom N, Schioler L, Svensson AM, Eag-Olofsson K, Jonasson JM, Zethelius B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of metformin in 51 675 patients with type 2 diabetes and different levels of renal function: a cohort study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. BMJ Open 2012; 2:e001076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Metformin: an update. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pasquali R, Gambineri A, Biscotti D, Vicennati V, Gagliardi L, Colitta D, et al. Effect of long-term treatment with metformin added to hypocaloric diet on body composition, fat distribution, and androgen and insulin levels in abdominally obese women with and without the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85:2767–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sowers JR, Whaley-Connell A, Hayden MR. The role of overweight and obesity in the cardiorenal syndrome. Cardiorenal Med 2011; 1:5–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sowers JR. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Clin Chem 1998; 44:1821–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998; 352:854–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ilabaca-Avendaño MB, Yarza-Solorzáno G, Rodriguez-Valenzuela J, Arcinas-Fausto G, Ramírez-Hernandez V, Hernández-Hernández DA, et al. Automated peritoneal dialysis as a lifesaving therapy in an emergency room: report of four cases. Kidney Int Suppl 2008; (108):S173–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vaziri ND, Ness R, Wellikson L, Barton C, Greep N. Bicarbonate-buffered peritoneal dialysis. An effective adjunct in the treatment of lactic acidosis. Am J Med 1979; 67:392–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sheppard JM, Lawrence JR, Oonf RCs, Thomas DW, Rowttand PG, Wise PH. Lactic acidosis: recovery associated with use of peritoneal dialysis. Aust NZ J Med 1972; 2:389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]