Abstract

♦ Objective: There is a paucity of published data on the outcome of maintenance peritoneal dialysis (PD) since the initiation of continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) in India in 1991. The purpose of this study is to report long-term clinical outcomes of PD patients at a single center.

♦ Design: Retrospective study.

♦ Setting: A government-owned tertiary-care hospital in North India.

♦ Patients: Patients who were initiated on CAPD between October 2002 and June 2011, and who survived and/or had more than 6 months’ follow-up on this treatment with last follow-up till December 31, 2011, were studied.

♦ Results: A total of 60 patients were included in the analysis. The mean age of the patients was 60.2 ± 9.2 years. The majority (65%) of the patients lived in rural areas. A high proportion (47%) were diabetic and 62% had ≥ 2 comorbidities. Total duration on peritoneal dialysis treatment was 1,773 patient-months (148 patient-years) with a mean duration of 29.6 ± 23 patient-months and median duration of 25 patient-months (range 6 - 110 patient-months). Overall patient and technique survival at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years was 77%, 53%, 25%, 15%, and 10% respectively. Patient survival of diabetics vs non-diabetics at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years was 68% vs 84%, 54% vs 53%, 14% vs 34%, 11% vs 19%, and 11% vs 13%, respectively. The mortality in non-diabetics (16/32) was less than that in diabetic (18/28) patients (p = not significant). The main cause of mortality in these patients was cardiac followed by sepsis. There were 58 episodes of peritonitis. The rate of peritonitis was 1 episode per 30.6 patient-months or 0.39 episodes per patient-year. Furthermore, the total number of episodes of peritonitis and number of episodes of peritonitis per patient were higher in the non-survival group (p < 0.05). The incidence of tuberculosis (TB), herpes zoster (HZ) and hernias was 15%, 10% and 5% respectively.

♦ Conclusion: The study reports long-term outcomes of the PD patients, the majority of whom were elderly with a high burden of comorbidities. There was a high proportion of diabetics. The survival of diabetic vs non-diabetic and elderly vs non-elderly PD patients was similar in our study. The mortality in non-diabetics was less than that in diabetic patients. TB and HZ were common causes of morbidity. Peritonitis was associated with mortality in these patients.

Keywords: Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, patient survival, technique survival, peritonitis, tuberculosis, herpes zoster, hernias

Maintenance peritoneal dialysis (PD), especially continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD), is an established treatment modality in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and approximately 150,000 patients are being maintained on CAPD worldwide (1). However, the decline of CAPD as compared with hemodialysis (HD) has become evident, even though many reports indicate that survival rates with PD are better than those with HD during the first 2 - 3 years after dialysis initiation (2,3).

Since its introduction in 1991, CAPD has become the established form of therapy in adults with ESRD in India. CAPD is gradually increasing among ESRD patients: it was 5% in 1996, 10% in 1998, 14% in 2002, and approximately 21% in 2008 (4). According to a recent publication there are 300 centers offering maintenance PD in India and the number of patients on PD has increased from 1,700 in 2001 to 6,500 in 2006 (5). There is a paucity of published data on the outcome of CAPD patients in India (4,6).

Himachal Pradesh is a mountainous state in the northern part of India, situated in the western Himalayas, with elevation ranging from about 350 meters to 7,000 meters above sea level. There is great diversity in the climatic conditions of Himachal Pradesh due to variation in elevation. The total population of the state is 6.8 million. It is the least urbanized state in India, with nearly 90% of the population living in rural areas (7). Many patients come from areas which remain snow-bound during winter. Due to hilly or mountainous terrain, commuting for maintenance HD is difficult. Therefore, CAPD remains the most viable modality of dialysis for patients living in this region. Furthermore, a good telecommunication service with over 100 per cent teledensity in the state is very conducive to this home-based dialysis because it enables the patients to remain in contact with the treating nephrologist, renal unit and clinical coordinators, even during harsh weather conditions.

Our center is the only tertiary-care hospital in the state of Himachal Pradesh providing dialysis services. We do not have a maintenance HD program at our institute. CAPD was first introduced at our center in 2002. The initial experience of CAPD at our institute has been published (8). The objective of this study is to report the long-term clinical outcomes of PD at our center.

Patients and Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of the patients who were initiated on CAPD at our hospital between October 2002 and June 2011. All patients had surgical implantation under local anesthesia of two-cuff Tenckhoff straight catheters. After a break-in period, the patients were initiated on manual exchanges using a twin-bag system; two patients later switched to automated peritoneal dialysis. All patients started PD with three 2-L exchanges daily and the dialysis prescription was changed according to individual requirements determined during the follow-up. All patients were taught to apply 2% mupirocin cream to the exit site with a cotton bud following daily exit-site care. Patients were advised to immediately contact the treating nephrologist by telephone for any assistance or advice. Patients with suspected peritonitis were advised to come to the hospital for microbiological analysis of the cloudy peritoneal effluent and treatment. Patients who were likely to experience a delay in reporting to hospital were advised to immediately start the empiric antibiotics covering both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms through an intraperitoneal route. Peritonitis was defined as cloudy fluid and/or abdominal pain associated with a white blood cell count > 100 (with > 50% neutrophils). All peritonitis patients were treated as per the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis protocol (9). All patients who survived and/or had more than six months’ follow-up on this treatment, with last follow-up till December 31, 2011, were included.

The baseline demographic characteristics, etiology of ESRD, presence of comorbidities, peritonitis episodes, clinical variables and biochemical parameters at the last follow-up of all patients were recorded. Coexisting diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, chronic lung disease, malignancy, thyroid disorders, or major psychiatric illness were considered as presence of comorbidities. The comorbid illnesses, survival, and complications related or unrelated to peritoneal dialysis were reviewed. The data were analyzed to determine overall outcome of CAPD patients in terms of patient survival, and to compare patient and technique survival; diabetic and non-diabetic CAPD patients, and CAPD patients aged < 60 years and aged ≥ 60 years.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviation and percentages were used to describe the demographic and clinical data. Student’s t-test was used to compare differences in clinical characteristics between different groups. For non-normal data, a Mann-Whitney test was performed. A chi-square test was used to compare proportions between different groups. Data for transfer to HD or kidney transplantation and lost to follow-up were censored in the patient survival analysis. Patient and technique survival rates were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method. A log-rank test was used to compare patient and technique survival between subgroups. A difference was considered significant when the p value was less than 0.05. All statistics were carried out using SPSS, version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Over the 9-year period, a total of 1,550 ESRD patients were hospitalized and received dialysis at our hospital. Out of these, 80 patients were initiated on CAPD. Thirteen patients survived less than six months on PD and seven patients had less than six months of PD treatment and were therefore excluded. Sixty patients who met the criteria were studied.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the PD patients. Thirty-three (55%) were male and 27 (45%) were female. Eleven (18%) patients were vegetarian. The mean age of the study patients was 60.2 ± 9.2 (range 44 - 77) years. Thirty-four (57%) were aged ≥ 60 years. Thirty-nine (65%) patients lived in rural areas. The etiology of ESRD was diabetic nephropathy 28 (47%), chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis 17 (28%), hypertension 11 (18%), chronic glomerulonephritis and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) in 2 (3%) patients each. All the patients (100%) had one or more non-renal comorbidity. The majority (62%) of the patients had ≥ 2 comorbidities. Fourteen (23%) patients had clinical cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the PD Patients (n=60)

The percentages of anemia, hypoalbuminemia and anuria at last follow-up were 72, 60 and 15 respectively. The comorbidities were higher in diabetic PD patients (p = 0.001) and hemoglobin was lower (p = 0.03) compared to non-diabetic PD patients.

Three PD exchanges a day was the standard treatment, but after development of anuria and if demanded by the clinical condition, the patients performed four PD exchanges a day. Two patients were getting icodextrin for ultra filtration failure and it had increased the technique survival for more than two years in each of these patients.

Follow-Up and Clinical Outcomes

This was a closely followed cohort by the treating nephrologist throughout the study period and all the clinical events were prospectively recorded. The periodic inputs received from the clinical coordinators after home visits carried out during PD-related complications were used to update patient records. Furthermore, a good telecommunication service in the state enabled the patients to contact the treating team in times of need. Overall event capture was nearly complete.

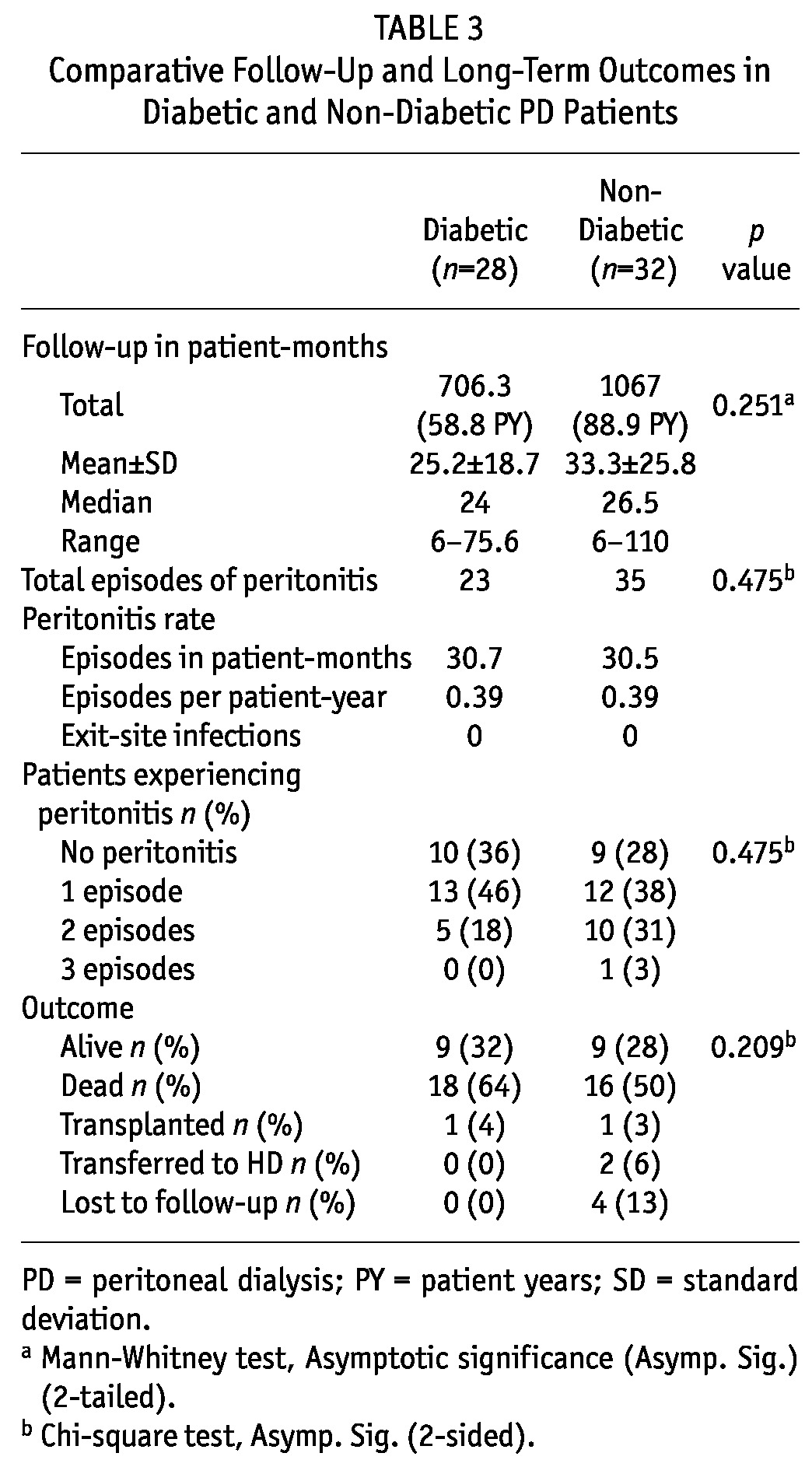

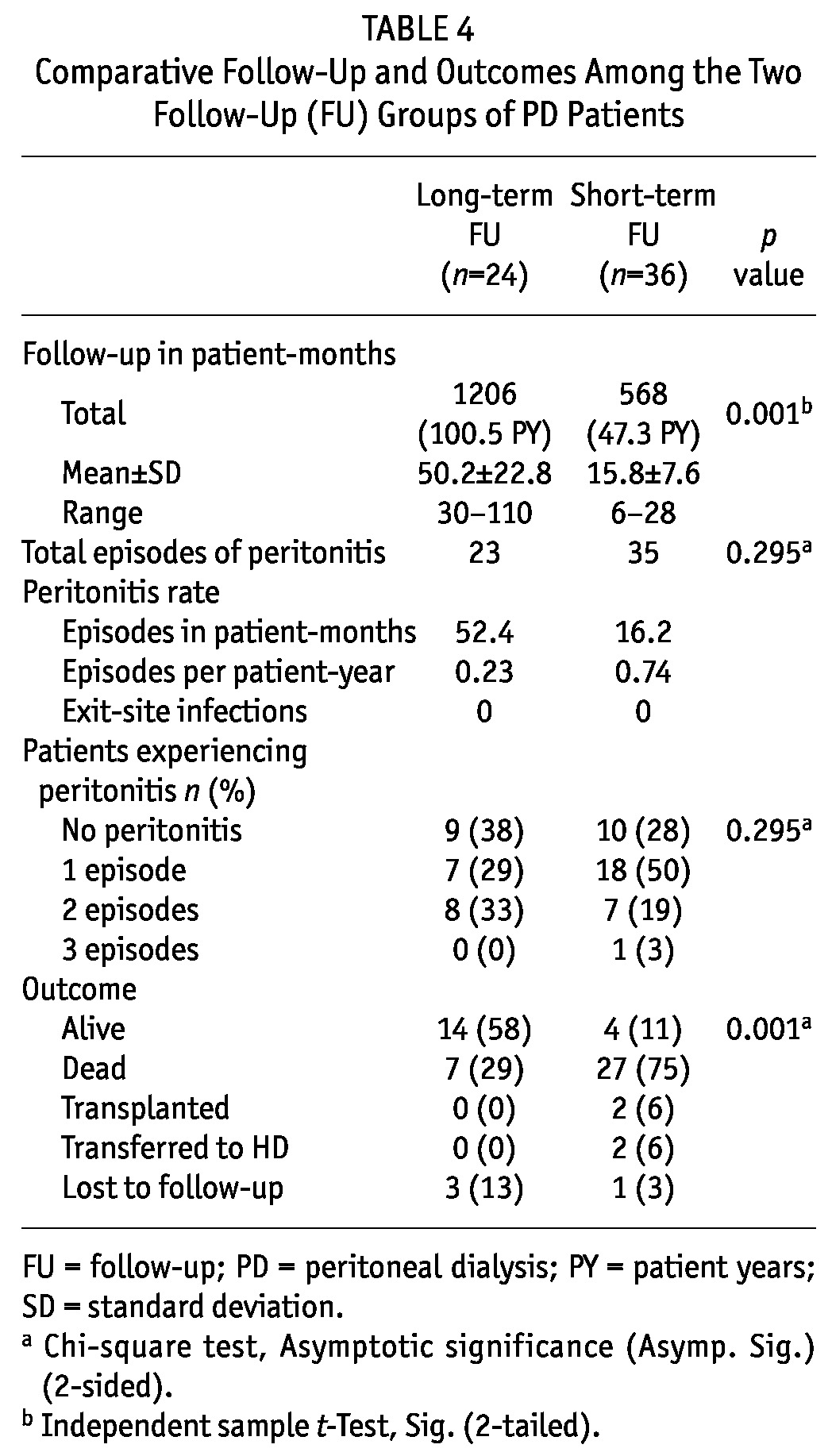

The total follow-up (FU) was 1,773 patient-months (147.8 patient-years) (Table 2). The mean duration of PD treatment was 29.6 ± 23 patient-months and median duration of 25 patient-months (range 6 - 110 patient-months). No patient had exit-site infection (ESI). There were 58 episodes of peritonitis. The rate of peritonitis was 1 episode per 30.6 patient-months or 0.39 episodes per patient-year during the treatment period. There was no significant difference in the follow-up and clinical outcomes of diabetic vs non-diabetic PD patients (Table 3). Ten (42%) of the long-term FU patients were diabetic and two (33%) out of six patients who survived more than five years were diabetic. The majority (58%) of the long-term FU patients were alive whereas 75% of the short-term FU patients had died, p = 0.001 (Table 4). There was no significant difference in other clinical outcomes between the two FU groups.

TABLE 2.

Follow-Up and Long-Term Outcomes of the PD Patients (n=60)

TABLE 3.

Comparative Follow-Up and Long-Term Outcomes in Diabetic and Non-Diabetic PD Patients

TABLE 4.

Comparative Follow-Up and Outcomes Among the Two Follow-Up (FU) Groups of PD Patients

Nine (15%) CAPD patients were diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) during the study period. Four patients had TB peritonitis, three had pulmonary TB and two had TB lymphadenitis. In three patients the diagnosis of TB peritonitis was made during life and in one the diagnosis was made postmortem. One TB peritonitis patient required catheter removal and switch to HD and the other two continued with PD treatment. Eight patients were treated with standard antituberculous treatment. Four patients successfully completed the treatment and were cured. Two patients died due to failure to tolerate and continue the anti-TB drug therapy. Two patients died of causes unrelated to TB while on treatment.

Six (10%) patients developed herpes zoster (HZ) during the study period. All patients were treated with oral acyclovir and had a good clinical response to therapy. In one patient, the course was complicated by acyclovir neurotoxicity which reversed after one session of HD. One patient suffered from post herpetic neuralgia.

Hernias were observed in 3 (5%) patients. The hernia rate observed was 0.02 per patient per year. The location was umbilical in two and inguinal in one.

Mortality

A total of 34 (57%) patients died. Thirteen (50%) of the surviving patients vs six (18%) of the non-surviving patients experienced no episode of peritonitis. Furthermore, the total number of episodes of peritonitis and number of episodes of peritonitis per patient were higher in the non-survival group (p < 0.05).The main cause of mortality in these patients was cardiac (65%) followed by sepsis (35%). The mortality in non-diabetics (16/32) was less than that in diabetic (18/28) patients (p = not significant). Mortality was higher in the short-term FU group (p = 0.001).

Patient and Technique Survival

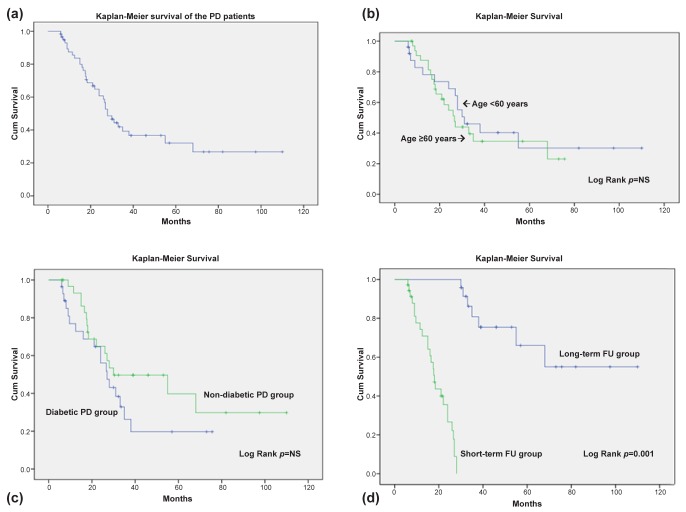

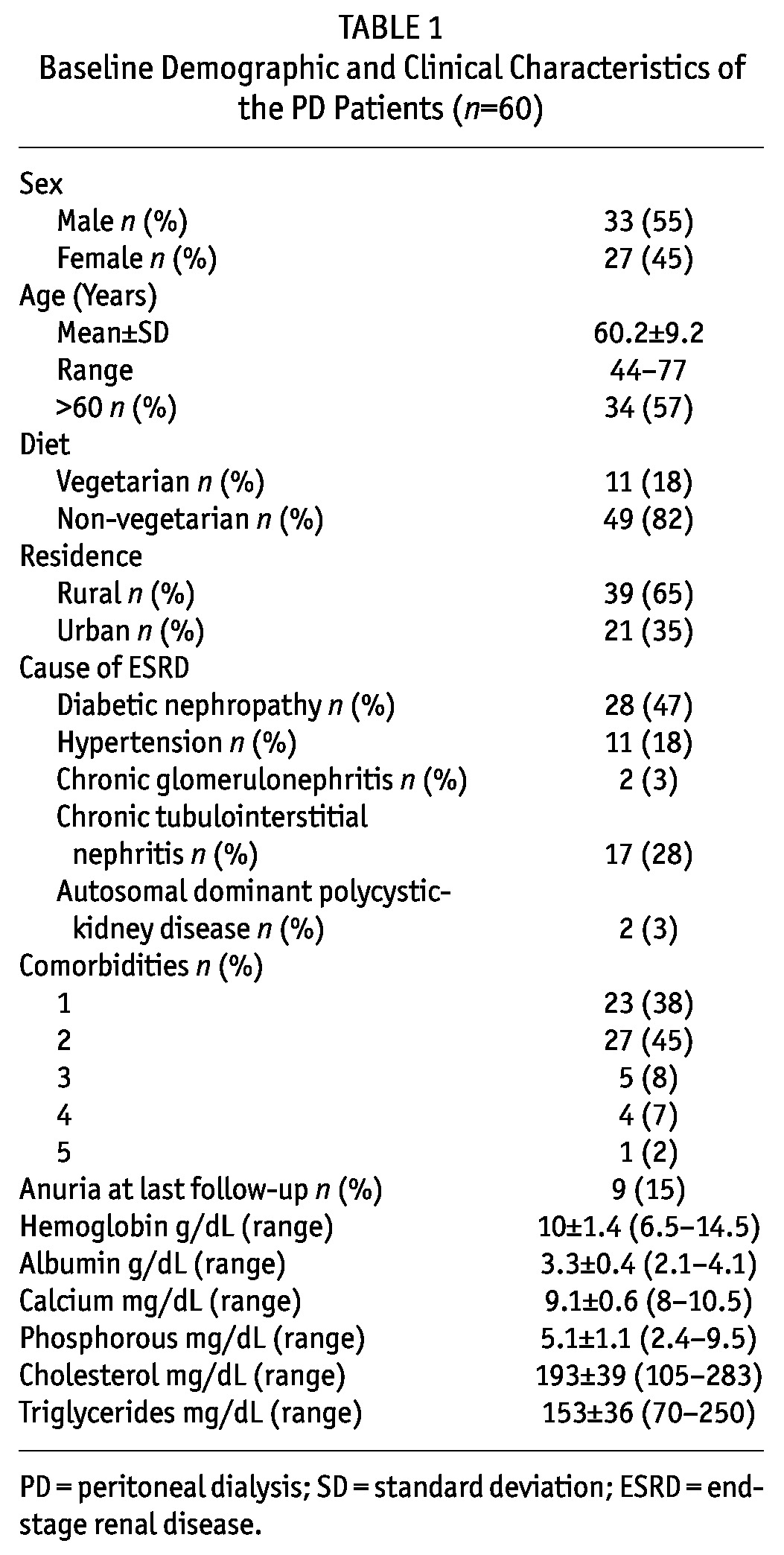

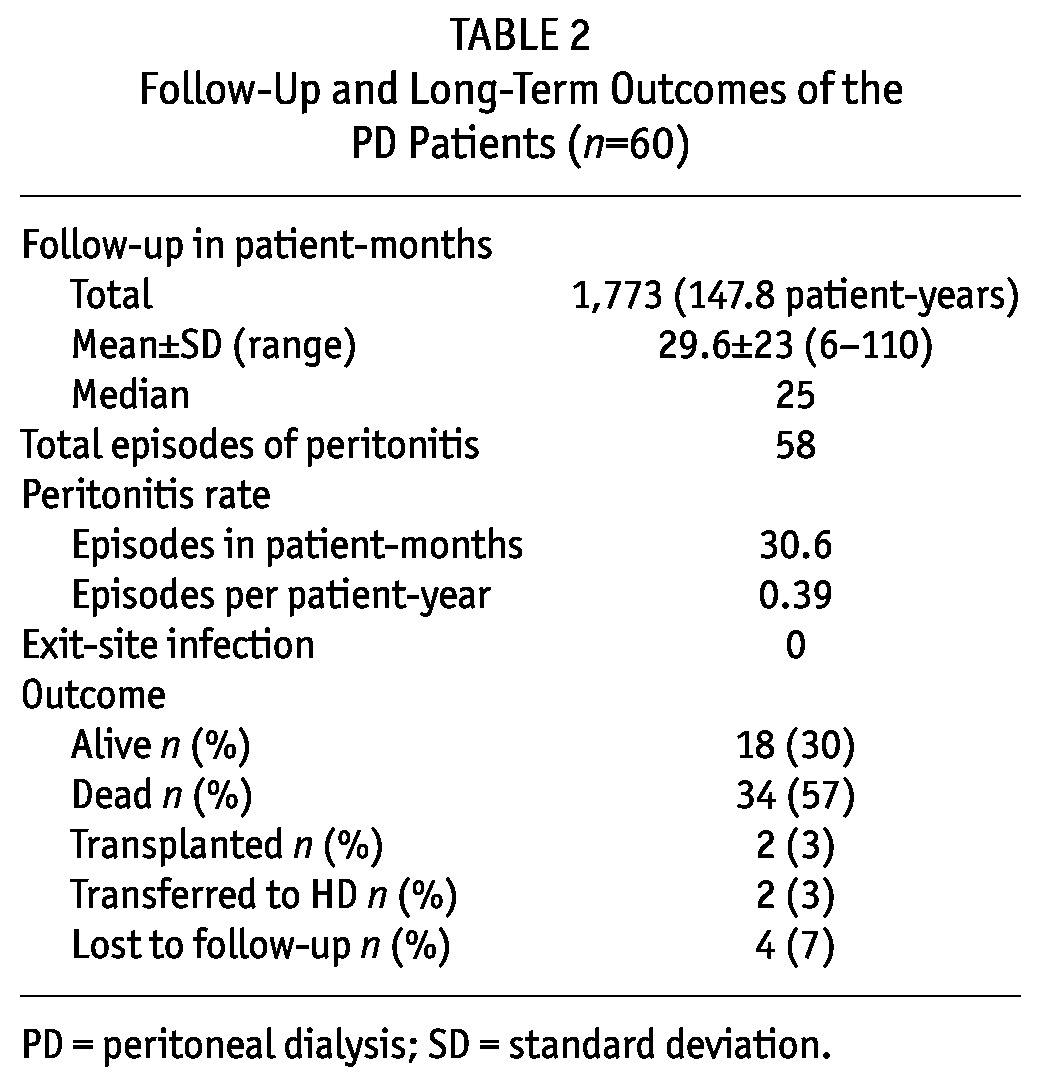

Overall patient and technique survival at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years was 77%, 53%, 25%, 15%, and 10% respectively. Patient survival of diabetics vs non-diabetics at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years was 68% vs 84%, 54% vs 53%, 14% vs 34%, 11% vs 19%, and 11% vs 13%, respectively. Thirty-six (60%) patients had a follow-up (FU) period of < 30 months (short-term FU) and 24 (40%) patients had a follow-up period of ≥ 30 months (long-term FU) (p = 0.001). Patient and technique survival in the long-term FU group at 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, and 5 years was 100%, 63%, 46%, 38%, 33%, 25% respectively. Nearly two-thirds survived three years and one-quarter survived > 5 years. For the short-term FU group, patient and technique survival at 1, 1.5, 2, and < 2.5 years was 61%, 42%, 22% and 20% respectively. Figure 1a shows the Kaplan-Meier survival of the PD patients. There was no difference in Kaplan-Meier survival of the age groups < 60 years vs ≥ 60 years (Figure 1b) and diabetic vs non-diabetic PD patients (Figure 1c), but there was a significant difference in the Kaplan-Meier survival of short-term vs long-term FU groups (Figure 1d).

Figure 1 —

a: Kaplan-Meier survival of the PD patients. b: Kaplan-Meier survival of age groups < 60 years vs ≥ 60 years. c: Kaplan-Meier survival of diabetic vs non-diabetic PD patients. d: Kaplan-Meier survival of short-term vs long-term FU groups. PD = peritoneal dialysis; FU = follow-up.

Discussion

Only 3 - 5% of all patients with ESRD in India get some form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) (5,10). In developing countries in Asia, PD offers certain clear advantages over HD, such as simplicity, reduced need for trained technicians and nurses, minimal technical support requirements, lack of electricity dependence, online water purification and home-based therapy with institutional independence which has potential cost savings (11). Eight to ten percent of the ESRD population in the state of Himachal Pradesh gets some form of RRT. CAPD is the main modality of treatment. They go outside the state for kidney transplantation and, even to get in-center HD, they need to relocate to cities outside the state.

Technique survival three years and longer on maintenance PD is considered rare in South Asian regions (5). Our study is the longest outcome study reported from this country and it adds to the few published CAPD studies from India. The first study from India, which was a single-center study of a cohort of 373 PD patients followed for six years, reported patient survival at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years of 90%, 72%, 60%, 49%, and 39%, respectively (4). Another multicenter long-term survival study from South India of a cohort of 209 PD patients reported patient survival of 87%, 82%, 72%, 45%, and 19% at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years respectively (6).

In our study, patient survival seems to be lower than that reported in the other studies (4,6). The majority (57%) of our study patients were elderly. Compared to the mean age of 60.2 years in our study, the mean age in other studies was lower (51.3 and 52.5 years). Sixty-two percent of our patients had ≥2 comorbidities as compared to a lower (18%) comorbidity rate in study by Prasad et al. (4).

The majority of patients reported in Prasad et al.’s (4) and Abraham et al.’s (6) studies resided in cities, while the majority of our patients resided in rural areas. City dwellers seem to have better survival compared to those living in towns and villages as they have better access to medical care. Patients in rural areas do not have access to proper microbiology services, well-stocked pharmacies, or medical care for comorbid conditions (6). These differences in demographic factors and clinical characteristics could explain the differences in patient survival observed in our study compared to other studies.

The leading cause of ESRD in our study was diabetic nephropathy, similar to the studies by Prasad et al. (4) and Abraham et al. (6). The percentage of diabetic patients in our study was 47 compared to a percentage of 53 and 48 respectively in these studies. The majority of reports agree that patient survival is lower and relative risk of death is higher in diabetics compared to non-diabetics (12-16). Prasad et al. found that patient survival was inferior in diabetic compared to non-diabetic patients on CAPD (4). In our study, the survival was inferior and mortality was higher in diabetics compared to non-diabetics but the differences were statistically not significant, perhaps due to small numbers in each group. However, the survival of diabetic patients was similar to survival rates reported by Viglino et al. (12) and Zimmerman et al. (16) in diabetic patients of comparable age groups. Diabetes should not deter nephrologists from using PD as a RRT (17).

Abraham et al. (6), in their outcome study of patients surviving ≥ 3 years, reported 4- and 5-year survival rates of 63% and 27% respectively compared to survival rates at respective periods of 38% and 25% observed in the long-term FU group in our study. These results affirm the importance of utilization of PD as a RRT in elderly and diabetic patients.

Peritonitis remains a major cause of technique failure, morbidity, and mortality in CAPD patients. The peritonitis rate in the major centers in India is one episode in 22 - 26 patient-months (18). The peritonitis rate of one episode per 30.6 patient-months or 0.39 episode per patient-year observed in our study is lower than that reported in studies by Prasad et al. (4) and Abraham et al. (6). As per International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis Guidelines, a peritonitis rate of 0.67 per year at risk should be considered acceptable and most programs can now achieve a peritonitis rate of 0.36 episodes per year at risk (19). The improved peritonitis rate may be due to the use of disconnect systems in all patients from the start of CAPD. Further, daily exit-site care with mupirocin contributed to excellent result of no ESI in our PD patients. It has been shown that application of mupirocin to the exit site considerably reduces ESI and peritonitis rates (20,21). The relative risk of developing peritonitis was not different in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Peritonitis was associated with mortality as the total number of episodes of peritonitis and number of episodes of peritonitis per patient were higher in the non-survival group in our study.

Effective fluid removal is undoubtedly a crucial predictor of patient survival. Indeed, Ateş et al. (22) demonstrated a clear relationship between relative risk of death and 24-hour ultrafiltration (UF) volume. The icodextrin in newly available PD solutions enhances fluid removal and is indicated for patients with UF loss. Patients with impaired UF, particularly in the settings of acute peritonitis, high transporter status and diabetes mellitus, appear to derive the greatest benefit from icodextrin with respect to augmentation of dialytic fluid removal, amelioration of symptomatic fluid retention and possible prolongation of technique survival. Glycemic control is also improved by substituting icodextrin for hypertonic glucose exchanges in diabetic patients (23). In our study, the use of icodextrin further increased the PD technique survival for more than two years in each of two long-term FU diabetic patients who were having UF loss.

The major cause of mortality in our patients was cardiovascular, followed by infection, similar to what was reported by Prasad et al. (4). Patients with ESRD who are on RRT usually have a certain number of comorbid factors. The presence of non-renal comorbidity in patients commencing RRT, therefore, is a major predictor of mortality (24). Cardiovascular diseases are the most common comorbidities and the most common causes of mortality in ESRD patients. Non-cardiovascular comorbid factors, including nutrition, also have an impact on survival of ESRD patients on RRT (25).

Patients with ESRD undergoing maintenance dialysis are 6 to 25 times more likely to develop TB than the general population, mainly because of the impaired cellular immunity characteristic of this condition. Extrapulmonary TB has been reported in as many as 60% to 80% of cases, either alone or associated with pulmonary TB (26). The reported incidence of TB in dialysis patients varies from 10% to 15% in India (27). Nine (15%) CAPD patients were diagnosed with TB during the study period. The majority (67%) of our patients had extrapulmonary involvement. Peritoneal TB, whilst otherwise relatively uncommon, is an important manifestation of TB in CAPD (28,29). It was the leading cause of TB in our patients. Treatment delay is the most significant factor contributing to high morbidity and mortality due to TB peritonitis. Early diagnosis and treatment of the disease are extremely important for improving outcome. Standard antituberculous chemotherapy is highly effective. Therefore, it is prudent to start empirical treatment with antituberculous chemotherapy in CAPD patients with peritonitits that is refractory to broad-spectrum antibiotics while awaiting the results of the mycobacterial cultures to improve the outcome and preserve peritoneal membrane integrity (30).

Six (10%) patients developed HZ during the study period. HZ is caused by the reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus in the cranial and dorsal root ganglia. Waning of cell-mediated immunity is thought to be one of the causes of varicella zoster virus reactivation and has been offered as the explanation for why immunosuppressive conditions and advancing age are the most consistently identified risk factors for HZ (31). Patients with ESRD exhibit defective cellular immunity, which is more affected than humoral immunity. The immunological deficiency due to uremia cannot be corrected by HD or CAPD (32). Population-based studies have found patients treated with long-term HD to be at an increased risk of HZ compared with the general population (33). The risk of HZ and its complications has been found to be higher in PD patients compared to HD patients (34).

Conclusion

The study reports on long-term outcomes of PD patients, the majority of whom were elderly with a high burden of comorbidities, with also a high proportion of diabetics. The survival of diabetic vs non-diabetic and elderly vs non-elderly PD patients was similar in our study. The mortality in non-diabetics was less than that in diabetic patients. TB and HZ were common causes of morbidity. Peritonitis was associated with mortality in these patients. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that CAPD is a viable procedure for ESRD patients in remote and rural places. It is an excellent alternative suitable for patients who are living in far flung areas where HD facilities are not easily available. Good results can be achieved by carefully selecting patients who have sufficient resources and can strictly adhere to the basic principles of asepsis. With good medical care, it can emerge as a safe, viable mode of RRT for ESRD patients dwelling in remote and geographically difficult regions in developing countries like India.

Disclosure

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- 1. Grassmann A, Gioberge S, Moeller S, Brown G. ESRD patients in 2004: global overview of patient numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20:2587–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collins AJ, Hao W, Xia H, Ebben JP, Everson SE, Constantini EG, et al. Mortality risks of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1999; 34:1065–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vonesh EF, Snyder JJ, Foley RN, Collins AJ. Mortality studies comparing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: what do they tell us? Kidney Int Suppl 2006; 103:S3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prasad N, Gupta A, Sinha A, Singh A, Sharma RK, Kumar A, et al. A comparison of outcomes between diabetic and nondiabetic CAPD patients in India. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28(5):468–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abraham G, Pratap B, Sankarasubbaiyan S, Govindan P, Nayak KS, Sheriff R, et al. Chronic peritoneal dialysis in South Asia - challenges and future. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:13–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abraham G, Kumar V, Nayak KS, Ravichandran R, Srinivasan G, Krishnamurthy M, et al. Predictors of long-term survival on peritoneal dialysis in South India: a multicenter study. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wikipedia contributors. Himachal Pradesh [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; Retrieved 2007-05-20 Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Himachal_Pradesh [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vikrant S. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A viable modality of renal replacement therapy in a hilly state of India. Indian J Nephrol 2007; 17:165–9 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keane WF, Baillie GR, Boeschoten E, Gokal R, Golper TA, Homes CJ, et al. Adult peritonitis treatment recommendations: 2000 update. Perit Dial Int 2000; 20:396–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abraham G. The challenges of renal replacement therapy in Asia. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2008; 4:643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reddy YN, Abraham G, Mathew M, Ravichandran R, Reddy YN. An Indian model for cost-effective CAPD with minimal man power and economic resources. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26:3089–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viglino G, Cancarini GC, Catizone L, Cocchi R, De Vecchi A, Lupo A, et al. Ten years experience of CAPD in diabetics: comparison of results with non-diabetics. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994; 9:1443–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMillan MA, Briggs JD, Junor BJ. Outcome of renal replacement in patients with diabetes mellitus. BMJ 1990; 301(6751):540–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Catalano C, Goodship TH, Tapson JS, Venning MK, Taylor RM, Proud G, et al. Renal replacement treatment for diabetic patients in Newcastle upon Tyne and the Northern region, 1964-88. BMJ 1990; 301(6751):535–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rotellar C, Black J, Winchester JF, Rakowski TA, Mosher WF, Mazzoni MJ, et al. Ten years’ experience with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1991; 17:158–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zimmerman SW, Oxton LL, Bidwell D, Wakeen M. Long-term outcome of diabetic patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 1996; 16:63–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Passadakis P, Thodis E, Vargemezis V, Oreopoulos D. Long-term survival on peritoneal dialysis in end-stage renal disease owing to diabetes. Adv Perit Dial 2000; 16:59–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abraham G. Asian PD perspective. An update on PD in the Indian subcontinent. ISPD Asian Chapter Newsletter 2004; 2(1). Available from www.ispd.org [Google Scholar]

- 19. Piraino B, Bernardini J, Brown E, Figueiredo A, Johnson DW, Lye WC, et al. ISPD position statement on reducing the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:614–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ward A, Campoli-Richards DM. Mupirocin. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use. Drugs 1986; 32:425–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mahajan S, Tiwari SC, Kalra V, Bhowmik DM, Agarwal SK, Dash SC, et al. Effect of local mupirocin application on exit-site infection and peritonitis in an Indian peritoneal dialysis population. Perit Dial Int 2005. Sep-Oct; 25(5):473–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ateş K, Nergizoğlu G, Keven K, Sen A, Kutlay S, Ertürk S, et al. Effect of fluid and sodium removal on mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2001. August; 60(2):767–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson DW, Agar J, Collins J, Disney A, Harris DC, Ibels L, et al. Recommendations for the use of icodextrin in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003. February; 8:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan IH. Comorbidity: the major challenge for survival and quality of life in end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13:76–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eiam-Ong S, Sitprija V. Comorbidities in patients with end-stage renal disease in developing countries. Artif Organs 2002; 26:753–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Segall L, Covic A. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in dialysis patients: current strategy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:1114–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jha V, Chugh KS. The practice of dialysis in the developing countries. Hemodial Int 2003; 7:239–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akpolat T. Tuberculous peritonitis. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29:S166–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ram R, Swarnalatha G, Akpolat T, Dakshinamurty KV. Mycobacterium tuberculous peritonitis in CAPD patients: a report of 11 patients and review of literature. Int Urol Nephrol 2013; 45(4):1129–35 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vikrant S, Guleria RC, Kanga A, Verma BS, Singh D, Dheer SK. Microbiological aspects of peritonitis in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Indian J Nephrol 2013; 23:12–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Joesoef RM, Harpaz R, Leung J, Bialek SR. Chronic medical conditions as risk factors for herpes zoster. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87:961–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sigaloff KC, de Fijter CW. Herpes zoster-associated encephalitis in a patient undergoing CAPD: case report and literature review. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27:391–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kuo CC, Lee CT, Lee IM, Ho SC, Yang CY. Risk of herpes zoster in patients treated with long-term hemodialysis: a matched cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2012; 59:428–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lin SY, Liu JH, Lin CL, Tsai IJ, Chen PC, Chung CJ, et al. A comparison of herpes zoster incidence across the spectrum of chronic kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation. Am J Nephrol 2012; 36(1):27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]