Abstract

The use of ultrasound in the prenatal diagnosis of fetal genetic syndromes is rapidly evolving. Advancing technology and new research findings are aiding in the increased accuracy of ultrasound-based diagnosis in combination with other methods of non-invasive and invasive fetal testing. Ultrasound as a screening tool for aneuploidy and other anomalies is increasingly being used throughout pregnancy, beginning in the first trimester. Given the number of recorded syndromes, it is important to identify patterns and establish a strategy for identifying abnormalities on ultrasound. These syndromes encompass a wide range of causes from viral, substance-linked, chromosomal, and other genetic syndromes. Despite the ability of those experienced in ultrasound, it is important to note that not all fetal genetic syndromes can be identified prenatally, and even common syndromes often have no associated ultrasound findings. Here, we review the role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of fetal genetic syndromes.

Keywords: ultrasound, genetic, syndrome, anomalies

Advancing technology

Two-dimensional ultrasonography has long been the modality of choice for diagnosis of fetal anomalies. However, the limitations of two-dimensional ultrasonography include the inability to store volume images for future manipulation, non-intuitive interpretation of the images for patients, and inability to simultaneously view images in a multiplanar view. Increasingly, because of the limitations of two-dimensional ultrasound, three dimensional and four-dimensional ultrasonography are being used to aid in diagnosing and visualising suspected fetal anomalies. Previous studies that have compared two-, three- and four-dimensional imaging to determine which has the best diagnostic ability or results in the best clinical outcomes in fetuses with anomalies have found some conflicting results. One study aimed to determine whether two-dimensional ultrasonography adds diagnostic information over three-dimensional and four-dimensional images. This study, which included 54 normal fetuses and 45 fetuses with anomalies, reported 90.4% agreement between two-, three-, and four-dimensional images. Six anomalies were missed by three- and four-dimensional imaging but observed by two-dimensional ultrasonography; however, the investigators concluded that the sensitivity and specificity of the imaging modalities were not significantly different.1 Another study by Dyson et al.2 comparing the results of two-dimensional with three-dimensional imaging found that three-dimensional ultrasonography offered additional information in 51% of cases, was equivalent in 45%, and was disadvantageous in 4%. Additional information obtained in three-dimensional imaging influenced clinical management in 5% of patients.2 Merz and Welter3 studied two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasound in 3472 high-risk pregnancies and discovered 1012 anomalies, excluding cardiac defects. They found that 4.2% of the malformations were correctly identified on three-dimensional ultrasound only. Although all these studies showed a benefit or at least equivalence of the imaging modalities, Scharf et al.4 concluded that three-dimensional visualisation was not superior to standard two-dimensional imaging, and should be restricted to specific malformations. Currently, three- and four-dimensional ultrasonography can be considered an adjunct to two-dimensional sonography, and can aid in the diagnosis of many fetal anomalies, especially those related to facial abnormalities (Figs. 1 and 2), neural tube defects, and skeletal anomalies.5,6

Fig. 1.

Two-dimensional image of bilateral cleft lip.

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional image of a unilateral cleft lip.

The use of three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of fetal oro-facial clefts when suspected on two-dimensional ultrasound greatly improves the sensitivity and specificity. In a recent systematic review, Maarse et al.7 found that use of three-dimensional ultrasound in women at high risk of fetal oro-facial clefts improves diagnostic accuracy. The detection rate of three-dimensional ultrasound was 100% in fetuses with cleft lip and 86–90% in fetuses with cleft lip and palate.7 Baumler et al.8 found that three-dimensional ultrasound of the fetal palate has a high accuracy in the diagnosis of cleft palate when cleft lip is identified on two-dimensional screening ultrasound.8

The use of three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of neural tube defects has been advocated by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine to define the upper level of the lesion.9 With three-dimensional ultrasound, through the use of multiple views, accuracy within one vertebral body can be achieved in 80% of cases.10

For the diagnosis of skeletal dysplasias, in which a precise diagnosis can significantly affect postnatal prognosis, three-dimensional ultrasound has been found to have an improved diagnostic accuracy. In a study by Ruano et al.11 three-dimensional ultrasound correctly identified 77.1% of cases compared with 51.4% with two-dimensional ultrasound. Additionally, three-dimensional ultrasound can improve patient understanding of the skeletal dysplasia and aid clinicians in counselling.12

Timing of ultrasound in diagnosis of fetal genetic syndromes

Ultrasound can be used throughout pregnancy to detect fetal abnormalities. First-trimester ultrasound is increasingly being used for nuchal translucency tests and also for an early limited anatomic survey. Ultrasound in the first trimester has been shown to be effective in screening for aneuploid conditions, such as trisomy 21.13 The nuchal translucency measurement in the first trimester, with a cut-off of 3 mm or greater, has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity for identifying pregnancies at risk for chromosomal anomalies.14 In addition, early anatomic surveys have been shown to have good detection rates of most structures when carried out by an experienced sonographer.15 Picklesimer et al.,16 in a retrospective cohort study of aneuploid fetuses, investigated the effect of gestational age at time of ultrasound on the detection of sonographic markers of aneuploidy. The fetal ultrasounds in this study were carried out between 14 and 32 weeks’ gestation, and the investigators showed that sonographic markers of aneuploidy were present at all gestational ages. In the earlier gestational ages, a shift was observed from detection of soft markers, non-structural abnormalities, to detection of major anomalies at later gestational ages.16

It is advised that all pregnant women undergo a fetal anatomic survey in the second trimester. Fetal anatomy is assessed systematically through ultrasound after about 18 weeks. Specifics of standard fetal anatomic evaluations are detailed in the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine practice guidelines.17 It is important to use a methodical routine in the execution and evaluation of the anatomic survey to assure complete assessment of fetal anatomy. The first trimester ultrasound largely focuses on nuchal translucency measurement in the assessment of chromosomal syndrome risk; however, the second trimester ultrasound can identify much more specific defects that follow a different pattern for each genetic syndrome. Importantly, some fetal anatomy is more easily visualised later in the second trimester. A prospective randomised study by Schwärzler et al.18 evaluated three different groups of fetuses distinguished by gestational age at time of anatomic survey for the outcome of need for additional ultrasound to complete the evaluation. The investigators concluded that fetuses that underwent an anatomic survey at 20–22 6/7 weeks are less likely to need repeat examination than women who have an ultrasound 18–18 6/7 weeks’ gestation.

Third-trimester ultrasound can also be used as an adjunct to second-trimester anatomic survey to follow the evolution of identified fetal abnormalities. Third-trimester ultrasound as a screening tool for fetal genetic syndromes, however, has limited utility. In 2008, it was concluded in a Cochrane review19 that routine use of third-trimester ultrasound screening in an unselected population of women does not confer benefit.

Infectious syndromes: ultrasound findings

Antepartum ultrasound can aid in the diagnosis of several intrauterine congenital infections. These infectious syndromes all have the potential to cause devastating in-utero and postnatal consequences, and even demise. Fortunately, the infectious syndromes rarely occur in developed nations. If identified prenatally, many of the infections can be treated. Therefore, it is important to understand the applications and limitations of ultrasound in the diagnosis of infectious syndromes. Additionally, it is important to note that infants with symptomatic congenital infections at birth do not always have abnormalities on prenatal ultrasound. The incidence and ultrasound findings most often associated with individual infectious syndromes are listed in Table 1.– Although ultrasound can be a clue in the diagnosis of infectious syndromes, the findings are not diagnostic, and definitive diagnosis should be determined by other means.

Table 1.

Incidence and ultrasound findings most often associated with individual infectious syndromes.

| Infection | Incidence of acute maternal infection | Most common ultrasound findings |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Cytomegalovirus | 0.2–2.2%20,21 | Neurological |

| intracranial calcifications | ||

| periventricular echogenicities | ||

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| echogenic bowel | ||

| hepatosplenomegaly | ||

| Cardiac | ||

| cardiomegaly | ||

| Other | ||

| intrauterine growth restriction | ||

| placentamegaly (Fig. 3) | ||

| hydrops.22–25 | ||

|

| ||

| Parvovirus | 1–4%26,27 | Hydrops, elevated middle cerebral artery dopplers28,29 |

|

| ||

| Toxoplasmosis | 0.2–1%30 | Neurological |

| ventriculomegaly | ||

| intracranial calcifications | ||

| periventricular calcifications | ||

| microcephaly | ||

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| hepatomegaly | ||

| Cardiac | ||

| myocardial calcifications | ||

| Other | ||

| hydrops | ||

| placentamegaly25,31 | ||

|

| ||

| Varicella | 0.01–0.4%32 | Neurological |

| microcephaly | ||

| ventriculomegaly or atrophy | ||

| microcalcifications | ||

| microopthalmia | ||

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| echogenic bowel | ||

| hepatic calcifications | ||

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Clubfeet | ||

| abnormal position of hands limb | ||

| hypoplasia | ||

| flexed limbs | ||

| Other | ||

| intrauterine growth restriction | ||

| hydrops33,34 | ||

|

| ||

| Syphilis | 0.4–1.3%35 | Gastrointestinal |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | ||

| Other | ||

| Placentomegaly | ||

| Hydrops25,36 | ||

Chromosomal syndromes

Invasive testing is the gold standard for prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal syndromes. Although the risks of invasive genetic testing are relatively low, chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis both increase the risks of pregnancy loss, preterm labour, and premature rupture of membranes, among other risks.37,38 Therefore, genetic screening tests have been developed and implemented in the general obstetric population to stratify women by risk category. The available genetic screening tests include first-trimester serum and nuchal translucency, second-trimester serum screening, and maternal plasma cell-free fetal DNA testing. The sensitivities and specificities of these screening tests vary. Often, patients use the addition of ultrasound markers of aneuploidy to determine whether they desire invasive diagnostic testing. Although a normal second-trimester anatomic survey does not eliminate possibility of aneuploidy, the absence of any marker can convey a significant risk reduction.39,40 Ultrasound can be used to identify structural anomalies, and also to detect soft markers of aneuploidy. The use of soft markers alone in the decision to pursue diagnostic testing in otherwise low-risk women can lead to unnecessary invasive procedures. On the other hand, a normal anatomic survey can give false reassurance to patients at high risk of aneuploidy.41 Therefore, although we must acknowledge that aneuploidy can be present with a normal sonographic exam, ultrasound performs an important role in the diagnosis of fetal chromosomal syndromes.42 Among the most common chromosomal syndromes that are identified through screening in pregnancy are trisomy 21, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13. The associated ultrasound findings that have been found are included in Table 2.–Many of the chromosomal syndromes have similar sonographic findings, and definitive diagnosis cannot be determined on the basis of ultrasound alone.

Table 2.

Ultrasound findings associated with common chromosomal syndromes.

| Organ system | Trisomy 21 (Down’s synderome) | Trisomy 18 (Edward’s syndrome) | Trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Echogenic intra-cardiac focus (Fig. 4); atrial-ventricular canal defect; atrial septal defect; ventricular septal defect; and other cardiac defects43,44 | Ventricular septal defect; atrial-ventricular canal canal defect; hypoplastic left heart syndrome; other cardiac defects.45–47 | Ventricular septal defect; hypoplastic left heart syndrome; double outlet right ventricle; and other cardiac defects.48–51 |

| Neurological | Choroid plexus cyst; and ventriculomegaly42,52 | Ventriculomegaly, choroid plexus cyst; Dandy–Walker malformation; and neural tube defects45–47 | Microcephaly, Holoprosencephaly.48–51 |

| Gastrointestinal | Hyperechoic bowel; duodenal atresia; oesophageal atresia53 | Omphalocele, diaphragmatic hernia; tracheoesophageal fistula; duodenal atresia; and hyperechoic bowel.45 | Omphalocele.48–51 |

| GU | Pyelectasis (Fig. 5).54 | Pyelectasis.45 | Hyperechoic kidneys, polycystic kidneys.48–51 |

| Facial | Absent or hypoplastic nasal bone55–57 | Micrognathia, cleft lip/palate45 | Cleft lip/palate48–51 |

| Musculoskeletal | Short humerus, short femur, clinodactyly58 | Clenched hands, overlapping digits, radial dysplasia, foot abnormalities45,46 | Post-axial polydactyly48–51 |

| Other | Thickened nuchal fold; and intrauterine growth restriction.59,60 | Thickened nuchal fold; single umbilical artery; and intrauterine growth restriction.46,47 | Thickened nuchal fold; and intrauterine growth restriction.48–51 |

Triploidy

Ultrasound can also aid in the identification of other chromosomal syndromes such as triploidy, Turner syndrome, and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Triploidy refers to the presence of a complete extra set of chromosomes. In triploid pregnancies, multiple associated abnormalities can be detected by ultrasound in almost every organ system. Data surrounding ultrasound findings of triploid fetuses are not robust, and largely consist of case reports and case series. One of the largest case series involved 30 triploid fetuses that all had first-trimester nuchal translucency and serum screening. Most (83%) of the triploid fetuses were ultimately diagnosed after invasive testing, which was ordered because of abnormalities on first-trimester screening.61 In addition to anomalies of every organ system, triploidy is commonly associated with severe intrauterine intrauterine growth restriction and an abnormal placental appearance.62,63

Turner syndrome

Turner syndrome, also called monosomy X, frequently ends in spontaneous abortion. The frequency among female live births is about 1 in 2500.64 Infants with Turner syndrome have a highly variable but characteristic phenotype, including short stature, webbed neck, widely spaced nipples, lymphoedema, cardiac, and renal malformations, infertility, and other comorbidities. Although many of the phenotypic expressions of Turner syndrome are identified post-natally, ultrasound can be used to identify some characteristics in the fetus. Baena et al.65 showed that, in an unselected population, cystic hygroma (Fig. 6) was present in 59.5%, and hydrops was present in 19%, of prenatally diagnosed Turner syndrome cases. Furthermore, in another study,66 68% of fetuses with Turner syndrome diagnosed on karyotype had sonographic abnormalities. In addition to cystic hygroma and hydrops fetalis, ultrasound findings in fetuses with Turner syndrome can include congenital heart defects, specifically coarctation of the aorta, ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, and a dilated right ventricle. Additionally, ultrasound may identify renal abnormalities, short femur, choroid plexus cysts, ventriculomegaly, echogenic intracardiac focus, or echogenic bowel.65,66

Fig. 6.

Ultrasound image of large septated cystic hygroma.

22q11.2 deletion syndrome

Another chromosomal syndrome that can be suspected on the basis of ultrasound findings is 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, also known as DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndrome. This syndrome is usually sporadic, but can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion from an affected parent. Affected fetuses usually have a cardiac anomaly such as tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defect, truncus arteriosus, pulmonary atresia, or interrupted aortic arch.67,68 Additionally, ultrasound can identify polyhydramnios, thymic hypoplasia, renal anomalies, microcephaly, and cleft palate in fetuses with 22q11.2 deletion.69–73

5p Deletion syndrome

Also known as Cri du Chat Syndrome, 5p deletion syndrome is a rare genetic syndrome. With this syndrome, a number of associated ultrasound features can lead to suspicion, and possible prenatal diagnosis. The most common ultrasound findings with 5p deletion syndrome include growth restriction, microcephaly, micrognathia, and hypertelorism.74 Other findings may include nasal bone hypoplasia, neurological abnormalities such as ventriculomegaly, and cardiac defects.75–77

Other genetic syndromes

Most genetic syndromes have been identified, and many others remain to be discovered. Some genetic syndromes have associated sonographic findings, whereas others do not. For example, genetic disorders of metabolism such as glycogen storage diseases, disorders of fatty acid oxidation, and lysosomal storage disorders, have no identifiable features on ultrasound. Because of the large number of genetic disorders with associated ultrasound findings, it is not possible to discuss them all within the scope of this review. As examples, however, Beckwith–Wiedemann and Noonan syndromes will be discussed.

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome is characterised by congenital anomalies, tumour predilection, and overgrowth. This syndrome is an imprinting disorder caused by abnormalities on chromosome 11p15.5.78 The diagnosis of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome is usually made after birth, but prenatal ultrasonography can contribute clues to this condition. Ultrasound findings can include an abdominal wall defect such as omphalocele, macroglossia, macrosomia, nephromegaly, and polyhydramnios.79,80

Noonan syndrome

The prevalence of Noonan syndrome is estimated at 1 in 1000 to 1 in 2500 people in the general population.81 Noonan syndrome is autosomal dominant in nature, and results from mutations in signal transduction pathway genes, including PTPN11, SOS1, KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, RAF1, and MAP2K1.81–83 The clinical findings in patients with Noonan syndrome include typical facial dysmorphisms, cardiovascular defects, short status, pectus excavatum or carinatum, mental retardation, and other varying anatomic abnormalities. In a retrospective cohort study by Baldassarre et al.,84 mean age at diagnosis of Noonan syndrome was 7 years. Twenty-one per cent of molecularly confirmed cases, however, had fetal anomalies present at prenatal ultrasonography, 41% had nuchal translucency over 2.5 mm, and 38% had polyhydramnios.84 This study concluded that, although abnormal prenatal findings are frequent in fetuses with Noonan syndrome, they are not specific and therefore are not useful for predicting the postnatal phenotype. Other studies have suggested that, in the absence of karyotype abnormalities, Noonan syndrome should be considered in the presence of cystic hygroma or increased nuchal translucency, cardiac defects, and polyhydramnios.85,86

Conclusion

The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of fetal genetic syndromes is as a screening tool to identify fetal, placenta, and amniotic abnormalities. With the knowledge of patterns seen with individual syndromes, identification of these abnormalities can lead to recommendations on definitive diagnostic testing, preparation for the post-natal period, or both. Current evidence supports the application of first-trimester ultrasound as a screening tool for select genetic syndromes. Second-trimester ultrasound provides the most information on fetal abnormalities and should be carried out in a structured and systematic manner. Use of three-dimensional and four-dimensional ultrasound as an adjunct to two-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of fetal structural abnormalities is a developing modality, and will likely be used in the future. Genotypic and phenotypic links are known for numerous genetic syndromes. In this chapter, we have only touched on a few of the genetic syndromes in existence to highlight the role of ultrasound as a screening tool in diagnosis. More invasive methods that are safer and more accurate when carried out under ultrasound guidance are needed for more definitive diagnosis.

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound image of placentamegaly.

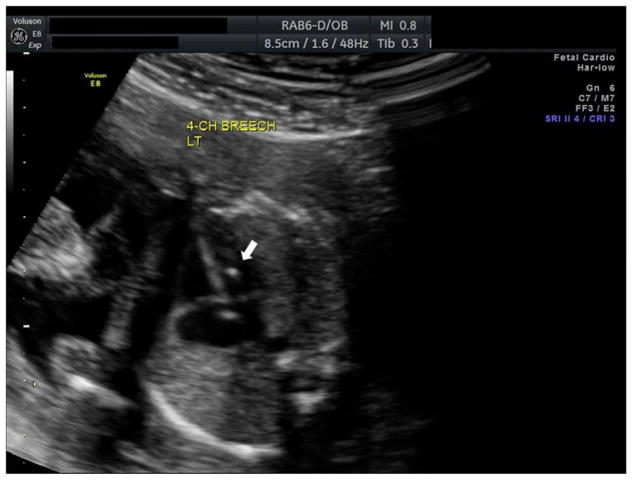

Fig. 4.

Ultrasound image of an echogenic intra-cardiac focus.

Fig. 5.

Ultrasound image of pyelectasis.

Practice points.

Ultrasound is a valuable tool in screening for fetal genetic syndromes.

First-, second-, and third-trimester ultrasounds provide information on possible fetal abnormalities; however, routine second-trimester anatomy ultrasound is the most accurate at identifying structural abnormalities.

Three-dimensional and four-dimensional ultrasound are useful adjuncts in the diagnosis of select fetal anomalies.

A normal ultrasound does not eliminate the possibility of a fetal genetic syndrome.

Ultrasound does not replace invasive testing for definitive diagnosis of genetic syndromes.

Research agenda.

Effect of timing of ultrasound on accuracy in diagnosis of fetal genetic syndromes and effects on maternal and fetal outcomes.

Routine use of three- and four-dimensional ultrasound when a structural malformation is identified.

Accuracy of ultrasound in screening for individual genetic syndromes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shayna N. Conner, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine,, Washington University, 4911 Barnes Jewish Hospital Plaza, Campus Box 8064, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

Ryan E. Longman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

Alison G. Cahill, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

References

- 1.Goncalves LF, Nien JK, Espinoza J, et al. What does two-dimensional imaging add to 3- and 4-dimensional obstetric ultrasonography? J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:691–699. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.6.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyson RL, Pretorius DH, Budorick NE, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the evaluation of fetal anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:321–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merz E, Welter C. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasound in the evaluation of normal and abnormal fetal anatomy in the second and third trimesters in a level III center. Ultraschall Med. 2005;26:9–16. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scharf A, Ghazwiny MF, Steinborn A, et al. Evaluation of two-dimensional versus three-dimensional ultrasound in obstetric diagnostics: a prospective study. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2001;16:333–341. doi: 10.1159/000053937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merz E, Abramowicz JS. Three-dimensional /four-dimensional ultrasound in prenatal diagnosis: is it time for routine use? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:336–351. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182446ef7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merz E, Bahlmann F, Weber G, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasonography in prenatal diagnosis. J Perinat Med. 1995;23:213–222. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1995.23.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maarse W, Berge SJ, Pistorius L, van Barneveld T, Kon M, Breugem C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transabdominal ultrasound in detecting prenatal cleft lip and palate: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:495–502. doi: 10.1002/uog.7472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumler M, Faure JM, Bigorre M, et al. Accuracy of prenatal three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of cleft hard palate when cleft lip is present. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:440–444. doi: 10.1002/uog.8933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benacerraf BR, Benson CB, Abuhamad AZ, et al. Three- and four-dimensional ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology: proceedings of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine Consensus Conference. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1587–1597. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.12.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron M, Moran P. Prenatal screening and diagnosis of neural tube defects. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29:402–411. doi: 10.1002/pd.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruano R, Molho M, Roume J, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal skeletal dysplasias by combining two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasound and intrauterine three-dimensional helical computer tomography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:134–140. doi: 10.1002/uog.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krakow D, Williams J, 3rd, Poehl M, et al. Use of three-dimensional ultrasound imaging in the diagnosis of prenatal-onset skeletal dysplasias. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:467–472. doi: 10.1002/uog.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malone FD, Canick JA, Ball RH, et al. First-trimester or second-trimester screening, or both, for Down’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2001–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo J, Gellen J, Szemere G. First-trimester ultrasound screening for fetal aneuploidies in women over 35 and under 35 years of age. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5:161–163. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1995.05030161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timor-Tritsch IE, Bashiri A, Monteagudo A, Arslan AA. Qualified and trained sonographers in the US can perform early fetal anatomy scans between 11 and 14 weeks. Am Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1247–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picklesimer AH, Moise KJ, Jr, Wolfe HM. The impact of gestational age on the sonographic detection of aneuploidy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1243–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medicine AIoUi. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of obstetric ultrasound examinations. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:1083–1101. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.6.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwärzler P, Schwarzler P, Senat MV, Holden D, et al. Feasibility of the second-trimester fetal ultrasound examination in an unselected population at 18, 20 or 22 weeks of pregnancy: a randomized trial. Ultrasound Obstetrics Gynecol. 1999;14:92–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14020092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bricker L, Neilson JP, Dowswell T. Routine ultrasound in late pregnancy (after 24 weeks’ gestation) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD001451. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001451.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fowler KB, Stagno S, Pass RF, et al. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:663–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203053261003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:253–276. doi: 10.1002/rmv.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerra B, Simonazzi G, Puccetti C, et al. Ultrasound prediction of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:380 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benoist G, Salomon LJ, Mohlo M, et al. Cytomegalovirus-related fetal brain lesions: comparison between targeted ultrasound examination and magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:900–9005. doi: 10.1002/uog.6129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malinger G, Lev D, Zahalka N, et al. Fetal cytomegalovirus infection of the brain: the spectrum of sonographic findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:28–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crino JP. Ultrasound and fetal diagnosis of perinatal infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;42:71–80. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199903000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamont RF, Sobel JD, Vaisbuch E, et al. Parvovirus B19 infection in human pregnancy. BJOG. 2011;118:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gratacos E, Torres PJ, Vidal J, et al. The incidence of human parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal outcome. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1360–1363. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delle Chiaie L, Buck G, Grab D, et al. Prediction of fetal anemia with Doppler measurement of the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity in pregnancies complicated by maternal blood group alloimmunization or parvovirus B19 infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:232–236. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2001.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pretlove SJ, Fox CE, Khan KS, et al. Noninvasive methods of detecting fetal anaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2009;116:1558–1567. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerina NG, Hsu HW, Meissner HC, et al. Neonatal serologic screening and early treatment for congenital Toxoplasma gondii infection. N England Regional Toxoplasma Working Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1858–1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harger JH, Ernest JM, Thurnau GR, et al. Frequency of congenital varicella syndrome in a prospective cohort of 347 pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:260–265. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enders G, Miller E, Cradock-Watson J, et al. Consequences of varicella and herpes zoster in pregnancy: prospective study of 1739 cases. Lancet. 1994;343:1548–1551. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92943-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pretorius DH, Hayward I, Jones KL, et al. Sonographic evaluation of pregnancies with maternal varicella infection. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:459–463. doi: 10.7863/jum.1992.11.9.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lumbiganon P, Piaggio G, Villar J, et al. The epidemiology of syphilis in pregnancy. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:486–494. doi: 10.1258/09564620260079653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puder KS, Treadwell MC, Gonik B. Ultrasound characteristics of in utero infection. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1997;53:262–270. doi: 10.1155/S1064744997000446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odibo AO, Dicke JM, Gray DL, et al. Evaluating the rate and risk factors for fetal loss after chorionic villus sampling. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:813–819. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181875b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odibo AO, Gray DL, Dicke JM, et al. Revisiting the fetal loss rate after second-trimester genetic amniocentesis: a single center’s 16-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:589–595. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318162eb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nyberg DA. Ultrasound markers of fetal Down syndrome. JAMA. 2001;13(285):2856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nyberg DA, Souter VL, El-Bastawissi A, et al. Isolated sonographic markers for detection of fetal Down syndrome in the second trimester of pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:1053–1063. doi: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.10.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith-Bindman R, Hosmer W, Feldstein VA, et al. Second-trimester ultrasound to detect fetuses with Down syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2001;285:1044–1055. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aagaard-Tillery KM, Malone FD, Nyberg DA, et al. Role of second-trimester genetic sonography after Down syndrome screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1189–1196. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c15064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman SB, Taft LF, Dooley KJ, et al. Population-based study of congenital heart defects in Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998;80:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tennstedt C, Chaoui R, Vogel M, et al. Pathologic correlation of sonographic echogenic foci in the fetal heart. Prenat Diag. 2000;20:287–292. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(200004)20:4<287::aid-pd802>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeo L, Guzman ER, Day-Salvatore D, et al. Prenatal detection of fetal trisomy 18 through abnormal sonographic features. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:581–90. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bronsteen R, Lee W, Vettraino IM, et al. Second-trimester sonography and trisomy 18. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:233–240. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson WJ, Miller RC, Wax JR, et al. Sonographic findings of trisomy 18 in the second trimester of pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:1033–1088. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.7.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson WJ, Miller RC, Wax JR, et al. Sonographic detection of trisomy 13 in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1209–1214. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.9.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snijders RJ, Sebire NJ, Nayar R, et al. Increased nuchal translucency in trisomy 13 fetuses at 10–14 weeks of gestation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;86:205–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seoud MA, Alley DC, Smith DL, Levy DL. Prenatal sonographic findings in trisomy 13, 18, 21 and 22. A review of 46 cases. The Journal of reproductive medicine. 1994 Oct;39(10):781–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lehman CD, Nyberg DA, Winter TC, 3rd, et al. Trisomy 13 syndrome: prenatal US findings in a review of 33 cases. Radiology. 1995;194:217–22. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.1.7997556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sohl BD, Scioscia AL, Budorick NE, Moore TR. Utility of minor ultrasonographic markers in the prediction of abnormal fetal karyotype at a prenatal diagnostic center. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:898–903. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Kouatly HB, Chasen ST, Streltzoff J, et al. The clinical significance of fetal echogenic bowel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1035–1038. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orzechowski KM, Berghella V. Isolated fetal pyelectasis and the risk of Down’s syndrome: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:615–621. doi: 10.1002/uog.12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bromley B, Lieberman E, Shipp TD, et al. Fetal nose bone length: a marker for Down syndrome in the second trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1387–1394. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.12.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosen T, D’Alton ME, Platt LD, et al. Nuchal Translucency Oversight Committee MFMF. First-trimester ultrasound assessment of the nasal bone to screen for aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:399–404. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275281.19344.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cicero S, Curcio P, Papageorghiou A, et al. Absence of nasal bone in fetuses with trisomy 21 at 11–14 weeks of gestation: an observational study. Lancet. 2001;358:1665–1667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benacerraf BR, Frigoletto FD, Jr, Cramer DW. Down syndrome: sonographic sign for diagnosis in the second-trimester fetus. Radiology. 1987;163:811–813. doi: 10.1148/radiology.163.3.2953039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crane JP, Gray DL. Sonographically measured nuchal skinfold thickness as a screening tool for Down syndrome: results of a prospective clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benacerraf BR, Frigoletto FD., Jr Soft tissue nuchal fold in the second-trimester fetus: standards for normal measurements compared with those in Down syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1146–1149. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Engelbrechtsen L, Brondum-Nielsen K, Ekelund C, et al. the Danish Fetal Medicine study g. Detection of triploidy at 11–14 weeks of gestation: a cohort study of 198,000 pregnant women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:530–535. doi: 10.1002/uog.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benacerraf BR. Intrauterine growth retardation in the first trimester associated with triploidy. J Ultrasound Med. 1988;7:153–154. doi: 10.7863/jum.1988.7.3.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crane JP, Beaver HA, Cheung SW. Antenatal ultrasound findings in fetal triploidy syndrome. J Ultrasound Med. 1985;4:519–524. doi: 10.7863/jum.1985.4.10.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stochholm K, Juul S, Juel K, et al. Prevalence, incidence, diagnostic delay, and mortality in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3897–902. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baena N, De Vigan C, Cariati E, et al. Turner syndrome: evaluation of prenatal diagnosis in 19 European registries. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;129A:16–20. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Papp C, Beke A, Mezei G, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of Turner syndrome: report on 69 cases. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:711–17. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Volpe P, Marasini M, Caruso G, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of interruption of the aortic arch and its association with deletion of chromosome 22q11. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;20:327–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Volpe P, Marasini M, Caruso G, et al. 22q11 deletions in fetuses with malformations of the outflow tracts or interruption of the aortic arch: impact of additional ultrasound signs. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:752–577. doi: 10.1002/pd.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Devriendt K, Swillen A, Fryns JP, et al. Renal and urological tract malformations caused by a 22q11 deletion. J Med Genet. 1996;33:349. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Devriendt K, Van Schoubroeck D, Eyskens B, et al. Polyhydramnios as a prenatal symptom of the digeorge/velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goodship J, Robson SC, Sturgiss S, et al. Renal abnormalities on obstetric ultrasound as a presentation of DiGeorge syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:867–70. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199709)17:9<867::aid-pd139>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ryan AK, Goodship JA, Wilson DI, et al. Spectrum of clinical features associated with interstitial chromosome 22q11 deletions: a European collaborative study. J Med Genet. 1997;34:798–804. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.10.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chaoui R, Kalache KD, Heling KS, Tennstedt C, et al. Absent or hypoplastic thymus on ultrasound: a marker for deletion 22q11. 2 in fetal cardiac defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;20:546–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aoki S, Hata T, Hata K, et al. Antenatal sonographic features of cri-du-chat syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13:216–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13030216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sherer DM, Eugene P, Dalloul M, et al. Second-trimester diagnosis of cri du chat (5p-) syndrome following sonographic depiction of an absent fetal nasal bone. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:387–388. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stefanou EG, Hanna G, Foakes A, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of cri du chat (5p-) syndrome in association with isolated moderate bilateral ventriculomegaly. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:64–66. doi: 10.1002/pd.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hills C, Moller JH, Finkelstein M, et al. Cri du chat syndrome and congenital heart disease: a review of previously reported cases and presentation of an additional 21 cases from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e924–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choufani S, Shuman C, Weksberg R. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. 2010;154C:343–354. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams DH, Gauthier DW, Maizels M. Prenatal diagnosis of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:879–884. doi: 10.1002/pd.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ranzini AC, Day-Salvatore D, Turner T, et al. Intrauterine growth and ultrasound findings in fetuses with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:538–542. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tartaglia M, Mehler EL, Goldberg R, et al. Mutations in PTPN11, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, cause Noonan syndrome. Nature Genet. 2001;29:465–468. doi: 10.1038/ng772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schubbert S, Zenker M, Rowe SL, et al. Germline KRAS mutations cause Noonan syndrome. Nature Genet. 2006;38:331–336. doi: 10.1038/ng1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roberts AE, Araki T, Swanson KD, et al. Germline gain-of-function mutations in SOS1 cause Noonan syndrome. Nature Genet. 2007;39:70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baldassarre G, Mussa A, Dotta A, et al. Prenatal features of Noonan syndrome: prevalence and prognostic value. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31:949–954. doi: 10.1002/pd.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Benacerraf BR, Greene MF, Holmes LB. The prenatal sonographic features of Noonan’s syndrome. J Ultrasound Med. 1989;8:59–63. doi: 10.7863/jum.1989.8.2.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hiippala A, Eronen M, Taipale P, et al. Fetal nuchal translucency and normal chromosomes: a long-term follow-up study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Young C, von Dadelszen P, Alfirevic Z. Instruments for chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD000114. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000114.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Crandon AJ, Peel KR. Amniocentesis with and without ultrasound guidance. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979;86:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1979.tb10673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Benacerraf BR, Frigoletto FD. Amniocentesis under continuous ultrasound guidance: a series of 232 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62:760–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ralston SJ, Craigo SD. Ultrasound-guided procedures for prenatal diagnosis and therapy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004;31:101–123. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8545(03)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]