Abstract

Background

Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) have proved to be involved in the detoxifying several carcinogens and may play an important role in carcinogenesis of cancer. Previous studies on the association between Glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) polymorphism and gastric cancer (GC) risk reported inconclusive results. To get a precise result, we conducted this present meta-analysis through pooling all eligible studies.

Methods

A comprehensive databases of Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM) were searched for case–control studies investigating the association between GSTM1 null genotype and GC risk. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used to assess this possible association. A χ2-based Q-test was used to examine the heterogeneity assumption. Begg’s and Egger’s test were used to examine the potential publication bias. The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether our assumptions or decisions have a major effect on the results of present work. Statistical analyses were performed with the software program STATA 12.0.

Results

A total of 47 eligible case–control studies were identified, including 6,678 cases and 12,912 controls. Our analyses suggested that GSTM1 null genotype was significantly associated with increased risk of GC (OR = 1.186, 95% CI = 1.057-1.329, Pheterogenetiy = 0.000, P = 0.004). Significant association was also found in Asians (OR = 1.269, 95% CI = 1.106-1.455, Pheterogenetiy = 0.002, P = 0.001). However, GSTM1 null genotype was not contributed to GC risk in Caucasians (OR = 1.115, 95% CI = 0.937-1.326, Pheterogenetiy = 0.000, P = 0.222). In the subgroup analysis stratified by sources of controls, significant association was detected in hospital-based studies (OR = 1.355, 95% CI = 1.179-1.557, Pheterogenetiy = 0.001, P = 0.000), while there was no significant association detected in population-based studies (OR = 1.017, 95% CI = 0.862-1.200, Pheterogenetiy = 0.000, P = 0.840).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed the evidence that GSTM1 null genotype contributed to the development of GC.

Virtual Slides

The virtual slide(s) for this article can be found here: http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs/1644180505119533.

Keywords: GSTM1, Polymorphism, Gastric cancer, Risk, Meta-analysis

Background

Multiple lines of evidence suggested both cumulative effect of environmental risk factors and genetic susceptibility of the individual contributed to the development of the cancers [1]. The gene-environment interaction in carcinogenesis is also well reflected by metabolic enzymes involved in the inactivation and/or detoxification of environmental carcinogens. Most of the carcinogens are metabolically inactivated by detoxification enzymes. Therefore, inherited variations in genes encoding the carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes may alter enzymatic activity and subsequently the carcinogens activation and/or deactivation [2]. Individual susceptibility to cancer is likely to be affected by the genotypes of biotransformation enzymes which represent significant ethnic differences in the frequency of alleles [3].

Human glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are phase II metabolizing enzymes that play a key role in protecting against cancer by detoxifying numerous potentially cytotoxic/genotoxic compounds [4]. The genes encoding the three major GST isoenzymes, GSTM (mu) 1, GSTT (theta) 1, and GSTP (pi) 1, widely expressed along the human gastrointestinal tract [5], are highly polymorphic. Among the GST isoforms, glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) is of particular interest and important because it possesses a present/null polymorphism and the null genotype has a complete absence of GSTM1 enzyme activity. It has been observed that GSTM1 null may affect individual susceptibility to cancer [6]. Up to now, numerous researches about the relationship between the polymorphism of GSTM1 null genotype and GC susceptibility have been conducted. However, the findings are controversial due to different reasons including the populations selected and their ethnicities. A recent meta-analysis of 15 studies suggested no association between the GSTM1 polymorphism and GC susceptibility was found [7]. When they performed the meta-analysis, the pooled sample size was relatively small and not enough information was available for more exhaustive subgroup analysis. Since then, additional several studies with a large sample size about this polymorphism on GC risk have been reported, which would greatly improve the power of the meta-analysis. In order to get a more precise result, we conducted this present meta-analysis.

Methods

Search strategy for eligible studies

We conducted a comprehensive search through the Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and Chinese Biomedical Data-base (CBM) databases for studies assessing the association between GSTM1 null genotype and GC risk. The literature strategy used the following keywords: (“Glutathione S-transferase M1”, “GSTM1” or “GSTM”) and (“gastric cancer”, “gastric carcinoma”, “stomach cancer” or “stomach carcinoma”). There was no sample size and language limitation. We evaluated all associated publications to retrieve the most eligible literatures. All references cited in the included studies were also hand-searched and reviewed to identify additional published articles not indexed in common databases. Of the studies with overlapping data published by the same authors, only the most recent or complete study was included in this meta-analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria of eligible studies were as following: (1) Evaluate the GSTM1 polymorphism and GC risk; (2) Only the case–control studies were considered; (3) The paper should clearly describe the diagnoses of GC and the sources of cases and controls; (4) The controls were gastric cancer-free individuals; (5) Reported the frequencies of GSTM1 polymorphism in both cases and controls or the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the association between GSTM1 null genotype and GC risk. The exclusion criteria were: (1) none case–control studies; (2) control population including malignant tumor patients; and (3) duplicated publications.

Data extraction

Relevant data were extracted from all the eligible studies independently by two reviewers, and disagreements were settled by discussion and the consensus was reached among all reviewers. The main data extracted from the eligible studies were as following: the first author, year of publication, ethnicity, genotype method, source of the controls, total numbers of cases and controls, the genotype frequency of GSTM1 polymorphism. Different ethnicities were mainly categorized as Caucasians, Asians, Africans, and Mixed. If a study did not specify the ethnicity or if it was not possible to separate participants according to such phenotype, the group was termed “mixed”. For studies including subjects of different ethnic populations, data were collected separately whenever possible and recognized as an independent study.

Quality assessment

Quality of eligible studies in present meta-analysis was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) as recommended by the Cochrane Non-Randomized Studies Methods Working Group. This instrument was developed to assess the quality of non-randomized studies, specifically cohort and case–control studies [8]. This instrument was developed to assess the quality of nonrandomized studies, specifically cohort and case–control studies. Based on the NOS, case–control studies were judged based on three broad perspectives: selection of study groups (1 criterion), comparability of study groups (4 criteria), and ascertainment of outcome of interest (3 criteria). Given the variability in quality of observational studies found on our initial literature search, we considered studies that met 5 or more of the NOS criteria as high quality (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp) [9].

Statistical methods

We examined the association between GSTM1 null genotype and GC risk by calculating pooled odds ratio (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and the significance of the pooled OR was determined by the Z-test. To assess the heterogeneity among the included studies more precisely, both the chi-square based Q statistic test (Cochran’s Q statistic) to test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic to quantify the proportion of the total variation due to heterogeneity [10,11]. If obvious heterogeneity existed among those included studies (P < 0.05), the random-effect model (DerSimonian and Laird method) was used to pool the results [12]. When there was no obvious heterogeneity existed among those included studies (P > 0.05), the fixed-effect model (Mantel-Haenszel’s method) was used to pool the results [13]. Moreover, subgroup analyses were performed to test whether the effect size varied by the ethnicity and the source of control population. The kinds of ethnicity were mainly defined as Caucasians, Asians. Publication bias was investigated with the funnel plot and its asymmetry suggested risk of publication bias. To evaluate the published bias, we used Begg’s [14] and Egger’s [15] formal statistical test and by visual inspection of the funnel plot. Furthermore, the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether our assumptions or decisions have a major effect on the results of the review by omitting each study [16]. All statistical tests for this meta-analysis were performed with STATA (version 12.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all the P values were two sided.

Results

Study characteristics

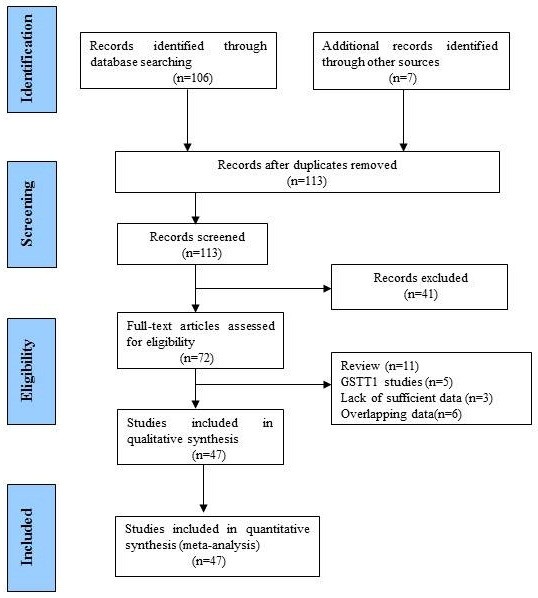

There were 113 relevant abstracts identified by searching the key words, and 41 studies were firstly excluded after the careful review of the abstracts, leaving 72 studies for full publication review (Figure 1). Of those 72 studies, 25 studies were excluded (6 for containing overlapping data, 11 for reviews, 3 for without adequate data, and 5 for on GSTT1 polymorphism). Table 1 listed the main characteristics of eligible studies included in this meta-analysis. There are 47 case–control studies, including 6,678 cases and 12,912 controls met the selection criteria [2,17-62]. Among the 47 studies, 24 studies are of Caucasians and 23 studies are of Asians. There are 25 studies of hospital-based controls and the rest are population-based controls.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of all the eligible studies in this meta-analysis

| First author | Year | Ethnicity | Control source |

Sample size |

Case |

Control |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Present | Null | Present | Null | ||||

| Strange et al. |

1991 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

19 |

49 |

5 |

14 |

29 |

20 |

| Harada et al. |

1992 |

Asian |

Population-based |

19 |

84 |

14 |

5 |

44 |

40 |

| Kato et al. |

1996 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

64 |

120 |

34 |

30 |

59 |

61 |

| Katoh et al. |

1996 |

Asian |

Population-based |

139 |

126 |

60 |

79 |

71 |

55 |

| Deakin et al. |

1996 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

136 |

577 |

64 |

72 |

261 |

316 |

| Enders et al. |

1998 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

51 |

35 |

23 |

28 |

22 |

13 |

| Martins et al. |

1998 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

148 |

84 |

77 |

71 |

40 |

44 |

| Oda et al. |

1999 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

147 |

112 |

56 |

91 |

57 |

55 |

| Cai et al. |

1999 |

Asian |

Population-based |

95 |

94 |

35 |

60 |

51 |

43 |

| Setiawan et al. |

2000 |

Asian |

Population-based |

87 |

419 |

45 |

42 |

207 |

212 |

| Lan et al. |

2001 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

347 |

426 |

180 |

167 |

204 |

222 |

| Saadat et al. |

2001 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

42 |

131 |

16 |

26 |

78 |

53 |

| Gao et al. |

2002 |

Asian |

Population-based |

153 |

223 |

63 |

90 |

90 |

133 |

| Wu et al. |

2002 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

356 |

278 |

183 |

173 |

142 |

136 |

| Sgambato et al. |

2002 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

8 |

100 |

3 |

5 |

47 |

53 |

| Choi et al. |

2003 |

Asian |

Population-based |

80 |

177 |

34 |

46 |

82 |

95 |

| Roth et al. |

2004 |

Asian |

Population-based |

90 |

454 |

66 |

24 |

309 |

145 |

| Suzuki et al. |

2004 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

145 |

177 |

58 |

87 |

93 |

84 |

| Colombo et al. |

2004 |

Mixed |

Population-based |

100 |

150 |

53 |

47 |

88 |

62 |

| Lai et al. |

2005 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

123 |

121 |

50 |

73 |

66 |

55 |

| Li et al. |

2005 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

100 |

62 |

33 |

67 |

36 |

26 |

| Mu et al. |

2005 |

Asian |

Population-based |

196 |

393 |

69 |

127 |

158 |

235 |

| Nan et al. |

2005 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

400 |

614 |

149 |

251 |

254 |

360 |

| Shen et al. |

2005 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

142 |

675 |

41 |

71 |

314 |

361 |

| Palli et al. |

2005 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

175 |

546 |

85 |

90 |

271 |

275 |

| Tamer et al. |

2005 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

70 |

204 |

30 |

40 |

116 |

88 |

| Nan et al. |

2005 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

107 |

220 |

34 |

73 |

90 |

130 |

| Hong et al. |

2006 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

108 |

238 |

48 |

60 |

104 |

134 |

| Agudo et al. |

2006 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

242 |

927 |

120 |

122 |

434 |

498 |

| Martinez et al. |

2006 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

87 |

329 |

54 |

33 |

180 |

149 |

| Boccia et al. |

2007 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

105 |

256 |

48 |

59 |

119 |

135 |

| Ruzzo et al. |

2007 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

79 |

112 |

44 |

35 |

51 |

61 |

| Wideroff et al. |

2007 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

116 |

209 |

55 |

61 |

87 |

121 |

| Tripathi et al. |

2008 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

76 |

100 |

45 |

31 |

61 |

39 |

| Al-Moundhri et al. |

2009 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

107 |

107 |

65 |

42 |

75 |

32 |

| Masoudi et al. |

2009 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

67 |

134 |

30 |

37 |

74 |

60 |

| Malik et al. |

2009 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

108 |

195 |

44 |

64 |

116 |

79 |

| Moy et al. |

2009 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

170 |

735 |

72 |

98 |

320 |

415 |

| Zendehdel et al. |

2009 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

181 |

624 |

54 |

70 |

230 |

239 |

| Palli et al. |

2010 |

Caucasian |

Population-based |

296 |

546 |

206 |

90 |

271 |

275 |

| Yadav et al. |

2010 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

133 |

270 |

84 |

49 |

150 |

120 |

| Luo et al. |

2010 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

123 |

129 |

30 |

93 |

58 |

71 |

| Nguyen et al. |

2010 |

Asian |

Hospital-based |

59 |

109 |

16 |

43 |

34 |

75 |

| Darazy et al. |

2011 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

13 |

70 |

7 |

6 |

58 |

12 |

| García-González et al. |

2012 |

Caucasian |

Hospital-based |

557 |

557 |

274 |

283 |

290 |

267 |

| Malakar et al. |

2012 |

Asian |

Population-based |

102 |

204 |

45 |

57 |

107 |

97 |

| Jing et al. | 2012 | Asian | Hospital-based | 410 | 410 | 170 | 240 | 203 | 207 |

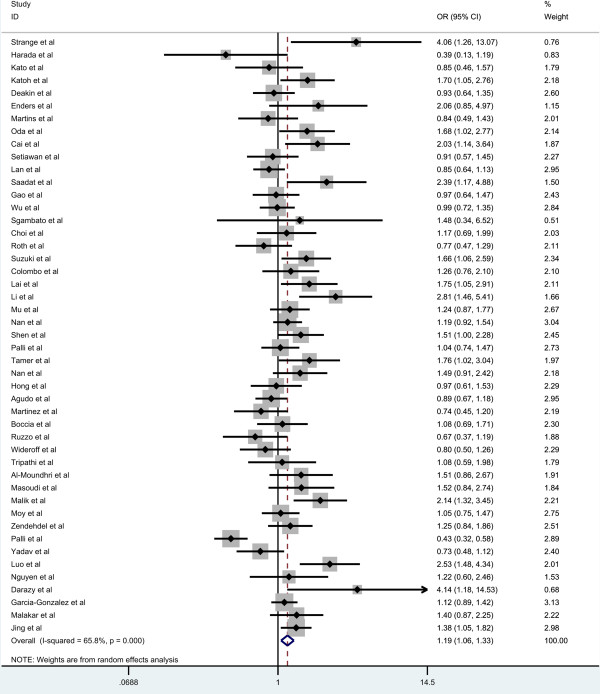

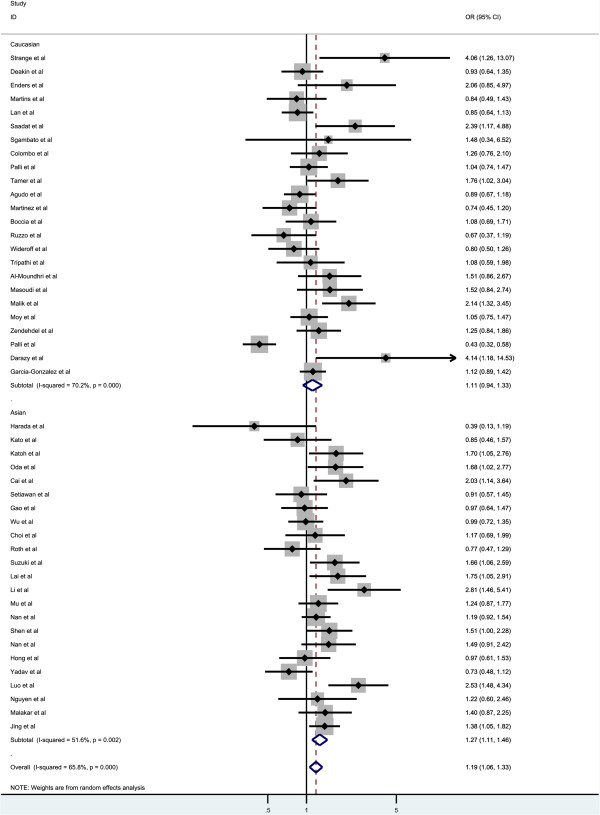

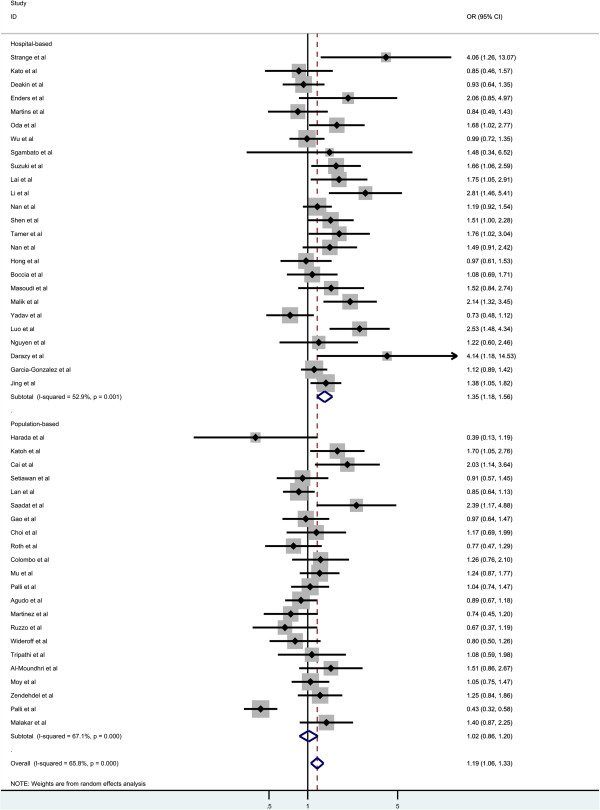

Quantitative synthesis

Overall, there was significant association between GC risk and the GSTM1 null genotypes when all the eligible studies were pooled into the meta-analysis (OR = 1.186, 95% CI = 1.057-1.329, Pheterogenetiy = 0.000, P = 0.004, Figure 2). Simultaneously, significant association was also found in Asians (OR = 1.269, 95% CI = 1.106-1.455, Pheterogenetiy = 0.002, P = 0.001, Figure 3). However, GSTM1 null genotype was not increased the risk of GC in Caucasians (OR = 1.115, 95% CI = 0.937-1.326, Pheterogenetiy = 0.000, P = 0.222, Figure 3). In the subgroup analysis stratified by sources of controls, significant association was detected in hospital-based studies (OR = 1.355, 95% CI = 1.179-1.557, Pheterogenetiy = 0.001, P = 0.000, Figure 4), while there was no significant association detected in population-based studies (OR = 1.017, 95% CI = 0.862-1.200, Pheterogenetiy = 0.000, P = 0.840, Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between GSTT1 null genotype and gastric cancer risk.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analyses of the association between GSTT1 null genotype and gastric cancer risk by the ethnicity.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analyses of the association between GSTT1 null genotype and gastric cancer risk according to the source of controls.

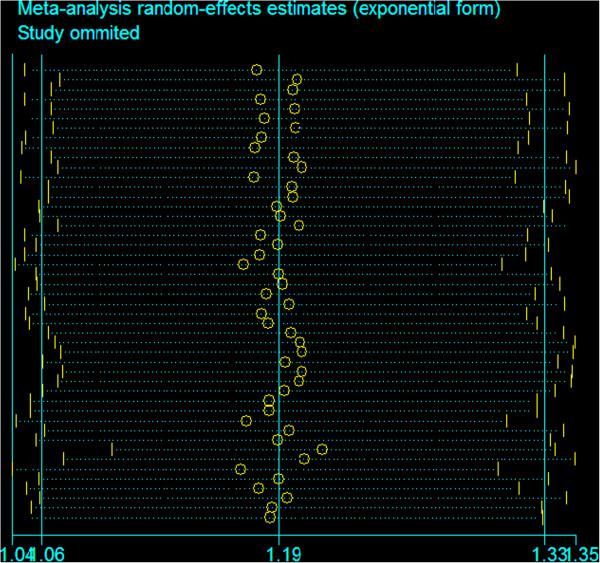

Sensitivity analysis

In order to compare the sensitivity of this meta-analysis, we conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. A single study involved in this meta-analysis was evaluated each time to reflect the influence of the individual data set to pooled ORs. The results pattern was not impacted by single study (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sensitive analysis of the pooled ORs and 95% CI for the overall analysis, omitting each dataset in the meta-analysis.

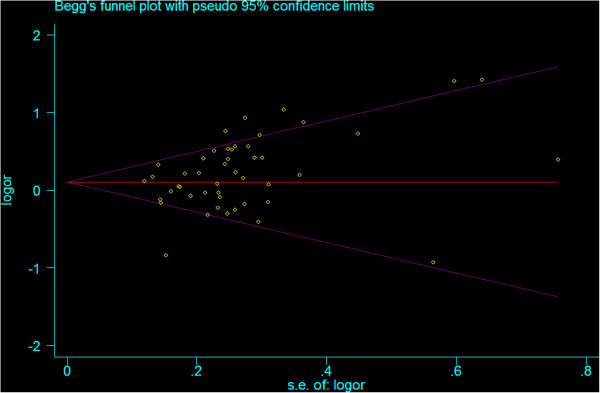

Publication bias

Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to assess the publication bias in this present work. The Funnel plots’ shape did not reveal obvious evidence of asymmetry (Figure 6), and the P value of Egger’s test was more than 0.05, providing statistical evidence for the funnel plots’ symmetry.

Figure 6.

Begg’s test for detecting the potential publication bias.

Discussion

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the world which accounts for 9.7% of total cancer deaths. Multiple factors have been proved contributed to the development of GC, including environmental, such as, Helicobacter pylori infection, Tobacco smoking and individual genetic polymorphism [63,64]. Since the first publication in 1991 by Strange et al. [17] reporting the association between the GSTT1 null genotype and the increased risk of GC, a large number of epidemiological studies concerning the link between GST gene polymorphisms and GC risk have been conducted. GSTM1 is generally considered as a protective enzyme because it detoxifies a number of toxic and carcinogenic substances such as nitrosamines and PAHs including BPDE [65].

As we all known, meta-analysis has great power to give a more credible results in one field than individual study through analyzing all the published research works with the same field [66,67]. Previous epidemiological studies have evaluated the association between the GSTM1 polymorphism and GC risk, but with inconclusive results. Therefore, it is necessary to perform this meta-analysis to identify the association between GSTM1 polymorphism and GC risk by combining the relevant studies published to date. Detection of gene genotype in all kinds of cancer not only in GC patient, which can be used for new therapeutic targets, will modify the current therapeutic approach. After pooling available data from all included studies, we found that there was significant association between this polymorphism and GC risk in over the world population. Our data are in line with those reported by Saadat et al. [68] and Boccia et al. [69] who observed a significantly increased risk of GC. This association can be explained by the reduced ability to detoxify the reactive intermediates that react with DNA because of the lack of GSTM1 enzyme activity [70].

It has been well known that cancer occurrence and mortality varied by ethnicity and geographic location. Piao et al. [71] suggested it was not associated with GC risk in different populations. In present work, significant association of GSTM1 polymorphism with GC risk was detected in Asian populations. However, no association was detected in Caucasians, which in line with previous meta-analysis conducted by Qiu et al. [72]. When stratified by source of controls, significant association between GSTM1 polymorphism and GC risk was observed among hospital-based studies. Many factors may contribute to this result, incompleteness of search, and include the potential false diagnoses (clinic, documentation, statistical methods). Furthermore, the use of typical control populations is vitally important, especially for the genetic association studies. The failure to reach a statistical significance in population-based studies implies that the selection of representative controls may reduce bias of the results.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Firstly, there was some heterogeneity in both the meta-analysis of total 48 studies and the subgroup analyses by ethnicity. The differences from the selection criteria of cases or controls, the adjusted confounding variables, and the ethnicity result in the heterogeneity. Secondly, most studies in the meta-analysis were retrospective design which could suffer more risk of bias owing to the methodological deficiency of retrospective studies. Those there was no obvious risk of publication bias in the present meta-analysis, the risks of other potential bias were unable to be excluded. Some misclassification bias was possible because most studies could not exclude latent gastric cancer cases in the control group. Therefore, more studies with prospective design and low risk of other bias are needed to provide a more precise estimate of the association between GSTM1 null genotype and GC risk. Finally, we could not address gene-gene and gene-environmental interactions in the association between GSTM1 null genotype and GC risk.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the meta-analysis with all the eligible studies published up to now, provides a more precise evidence for the significant association between GSTM1 null genotype and increased risk of GC. In addition, more individual studies with well design are needed to further assess the possible gene-gene and gene-environmental interactions in the association between GSTM1 null genotype and GC risk.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XM, BL and YL conceived and designed the experiments. XM and BL analyzed the data. XM, BL and YL contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. XM and YL wrote the paper. Yong Liu revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xianhong Meng, Email: xianhongmeng_hr@126.com.

Yong Liu, Email: yongliu_sy@126.com.

Bona Liu, Email: bona_liu@126.com.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the people who give technical support and useful discussion of the paper.

References

- Oliveira C, Seruca R, Carneiro F. Genetics, pathology, and clinicsof familial gastric cancer. Int J SurgPathol. 2006;14:21–33. doi: 10.1177/106689690601400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccia S, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Persiani R, Gianfagna F, Rausei S, Arzani D, La Greca A, D'Ugo D, La Torre G, van Duijn CM, Ricciardi G. Polymorphisms in metabolic genes, their combination and interaction with tobacco smoke and alcohol consumption and risk of gastric cancer: a case–control study in an Italian population. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:206–213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros R, Vasconcelos A, Costa S, Pinto D, Ferreira P, Lobo F, Morais A, Oliveira J, Lopes C. Metabolic susceptibility genes and prostate cancer risk in asouthernEuropean population: the role of glutathione S-transferases GSTM1, GSTM3, and GSTT1 genetic polymorphisms. Prostate. 2004;58:414–420. doi: 10.1002/pros.10348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, Pulford DJ. The glutathione S-transferase super-gene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30:445–600. doi: 10.3109/10409239509083491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin W, Wagenmans M, Peters W. Expression of glutathioneS-transferase alpha, P1-1 and T1-1 in the human gastrointestinal tract. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:310–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb00946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavel J, Bellec S, Rebouissou S, Ménégaux F, Feunteun J, Bonaïti-Pellié C, Baruchel A, Kebaili K, Lambilliotte A, Leverger G, Sommelet D, Lescoeur B, Beaune P, Hémon D, Loriot MA. Childhood leukaemia, polymorphisms ofmetabolism enzyme genes, and interactions with maternal tobacco, coffee and alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Eur J CancerPrev. 2005;14:531–540. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Torre G, Boccia S, Ricciardi G. Glutathione S-transferase M1 status andgastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Lett. 2005;217:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang AP, Liu BH, Wang L, Gao Y, Li F, Sun SX. Glutathione S-transferasegene polymorphisms and risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:3421–3425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) forassessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed February 22, 2011.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuringinconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10(1):101–129. [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data fromretrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlationtest for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysisdetected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysong SJ. Meta-analysis: audit and feedback features impact effectiveness on care quality. Med Care. 2009;47(3):356–363. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181893f6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange RC, Matharoo B, Faulder GC, Jones P, Cotton W, Elder JB, Deakin M. The human glutathione S-transferases: a case–control study of the incidence of the GST1 0 phenotype in patients with adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 1991;12:25–28. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada S, Misawa S, Nakamura T, Tanaka N, Ueno E, Nozoe M. Detection of GST1 genedeletion by the polymerase chain reaction and its possible correlation with stomach cancer in Japanese. Hum Genet. 1992;90:62–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00210745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Onda M, Matsukura N, Tokunaga A, Matsuda N, Yamashita K, Shields PG. Genetic polymorphisms ofthe cancer-related gene and Helicobacter pylori infection inJapanese gastric cancer patients: an age and gender matchedcase-control study. Cancer. 1996;77:1654–1661. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960415)77:8<1654::AID-CNCR35>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T, Nagata N, Kuroda Y, Itoh H, Kawahara A, Kuroki N, Ookuma R, Bell DA. Glutathione S-transferaseM1 (GSTM1) and T1 (GSTT1) genetic polymorphism and susceptibility to gastric and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1855–1859. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.9.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin M, Elder J, Hendrickse C, Peckham D, Baldwin D, Pantin C, Wild N, Leopard P, Bell DA, Jones P, Duncan H, Brannigan K, Alldersea J, Fryer AA, Strange RC. Glutathione S-transferaseGSTT1 genotypes and susceptibility to cancer: studies of interactions with GSTM1 in lung, oral, gastric and colorectal cancers. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:881–884. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng EK, Sung JJ, Ling TK, Ip SM, Lau JY, Chan AC, Liew CT, Chung SC. Helicobacter pylori and thenull genotype of glutathione-S-transferase-mu in patients withgastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1998;82:268–273. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980115)82:2<268::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins G, Alves M. Glutathione S transferase mu polymorphism and gastric cancer in the Portuguese population. Biomarkers. 1998;3:441–447. doi: 10.1080/135475098231084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Kobayashi M, Ooi A, Muroishi Y, Nakanishi I. Genotypes of glutathione S-transferase M1 and N-acetyltransferase 2in Japanese patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2:158–164. doi: 10.1007/s101200050040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Yu SZ, Zhang ZF. Glutathione S-transferases M1, T1genotypes and the risk of gastric cancer: a case–control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:506–509. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan VW, Zhang ZF, Yu GP, Li YL, Lu ML, Tsai CJ, Cordova D, Wang MR, Guo CH, Yu SZ, Kurtz RC. GSTT1 and GSTM1 null genotypes and the risk of gastric cancer: a case–control study in a Chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, Chow WH, Lissowska J, Hein DW, Buetow K, Engel LS, Ji B, Zatonski W, Rothman N. Glutathione S-transferase genotypes and stomach cancer in a population-based case–control study in Warsaw, Poland. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:655–661. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat I, Saadat M. Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 nullgenotypes and the risk of gastric and colorectal cancers. Cancer Lett. 2001;169:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00550-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao CM, Takezaki T, Wu JZ, Li ZY, Liu YT, Li SP, Ding JH, Su P, Hu X, Xu TL, Sugimura H, Tajima K. Glutathione-S-transferases M1 (GSTM1) and GSTT1 genotype, smoking, consumption of alcohol and tea and risk of esophageal and stomach cancers: a case–control study of a high-incidence area in Jiangsu Province, China. Cancer Lett. 2002;188:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MS, Chen CJ, Lin MT, Wang HP, Shun CT, Sheu JC, Lin JT. Genetic polymorphisms ofcytochrome p450 2E1, glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1, andsusceptibility to gastric carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:338–343. doi: 10.1007/s00384-001-0383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgambato A, Campisi B, Zupa A, Bochicchio A, Romano G, Tartarone A, Galasso R, Traficante A, Cittadini A. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) polymorphisms as risk factors for cancer in a highly homogeneous population from southern Italy. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:3647–3652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SC, Yun KJ, Kim TH, Kim HJ, Park SG, Oh GJ, Chae SC, Oh GJ, Nah YH, Kim JJ, Chung HT. Prognostic potential of glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 null genotypes for gastric cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2003;195:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MJ, Abnet CC, Johnson LL, Mark SD, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Dawsey SM, Qiao YL. Polymorphic variation of Cyp1A1 is associated with the risk of gastric cardia cancer: a prospective case-cohort study of cytochrome P-450 1A1 and GST enzymes. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:1077–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-2233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Muroishi Y, Nakanishi I, Oda Y. Relationship between genetic polymorphisms of drug-metabolizing enzymes (CYP1A1, CYP2E1, GSTM1, and NAT2), drinking habits, histological subtypes, and p53 gene point mutations in Japanese patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:220–230. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo J, Rossit AR, Caetano A, Borim AA, Wornrath D, Silva AE. GSTT1, GSTM1 andCYP2E1 genetic polymorphisms in gastric cancer and chronicgastritis in a Brazilian population. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1240–1245. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai KC, Chen WC, Tsai FJ, Li SY, Chou MC, Jeng LB. Glutathione S-transferase M1gene null genotype and gastric cancer risk in Taiwan. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 2005;52:1916–1919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Chen XL, Li HQ. Polymorphism of CYPIA1 and GSTM1genes associated with susceptibility of gastric cancer in Shandong Province of China. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5757–5762. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i37.5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu LN, Lu QY, Yu SZ, Jiang QW, Cao W, You NC, Setiawan VW, Zhou XF, Ding BG, Wang RH, Zhao J, Cai L, Rao JY, Heber D, Zhang ZF. Green tea drinking and multigenetic index on the risk of stomach cancer in a Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:972–983. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan HM, Park JW, Song YJ, Yun HY, Park JS, Hyun T, Youn SJ, Kim YD, Kang JW, Kim H. Kimchi and soybean pastes arerisk factors of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3175–3181. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i21.3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Wang RT, Xu YC, Wang LW, Wang XR. Interaction models of CYP1A1, GSTM1 polymorphisms and tobacco smoking in intestinal gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6056–6060. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i38.6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palli D, Saieva C, Gemma S, Masala G, Gomez-Miguel MJ, Luzzi I, D'Errico M, Matullo G, Ozzola G, Manetti R, Nesi G, Sera F, Zanna I, Dogliotti E, Testai E. GSTT1 and GSTM1 gene polymorphisms and gastric cancer in a high-risk Italian population. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:284–289. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamer L, Ateş NA, Ateş C, Ercan B, Elipek T, Yildirim H, Camdeviren H, Atik U, Aydin S. Glutathione S-transferase M1, T1 and P1 genetic polymorphisms, cigarette smoking and gastric cancer risk. Cell Biochem Funct. 2005;23:267–272. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan HM, Song YJ, Yun HY, Park JS, Kim H. Effects of dietary intake and genetic factors on hyper methylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3834–3841. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i25.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SH, Kim JW, Kim HG, Park IK, Ryoo JW, Lee CH, Sohn YK, Lee JY. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1) and N-acetyl transferase 2 polymorphisms and the risk of gastric cancer. J Prev Med Pub Health. 2006;39:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agudo A, Sala N, Pera G, Capellá G, Berenguer A, García N, Palli D, Boeing H, Del Giudice G, Saieva C, Carneiro F, Berrino F, Sacerdote C, Tumino R, Panico S, Berglund G, Simán H, Stenling R, Hallmans G, Martínez C, Amiano P, Barricarte A, Navarro C, Quirós JR, Allen N, Key T, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Linseisen J, Nagel G. et al. No association between polymorphisms in CYP2E1, GSTM1, NAT1, NAT2 and the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1043–1045. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C, Martín F, Fernández JM, García-Martín E, Sastre J, Díaz-Rubio M, Agúndez JA, Ladero JM. Glutathione S-transferases mu 1, theta 1, pi 1, alpha 1 and mu 3 genetic polymorphisms and the risk of colorectal and gastric cancers in humans. Pharmaco Genomics. 2006;7:711–718. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzo A, Canestrari E, Maltese P, Pizzagalli F, Graziano F, Santini D, Catalano V, Ficarelli R, Mari D, Bisonni R, Giordani P, Giustini L, Lippe P, Silva R, Mattioli R, Torresi U, Latini L, Magnani M. Polymorphisms in genes involved in DNA repair and metabolism of xenobiotics in individual susceptibility to sporadic diffuse gastric cancer. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:822–828. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wideroff L, Vaughan TL, Farin FM, Gammon MD, Risch H, Stanford JL, Chow WH. GST, NAT1, CYP1A1polymorphisms and risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi S, Ghoshal U, Ghoshal UC, Mittal B, Krishnani N, Chourasia D, Agarwal AK, Singh K. Gastric carcinogenesis: possible role of polymorphisms of GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 genes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:431–439. doi: 10.1080/00365520701742930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Moundhri MS, Alkindy M, Al-Nabhani M, Al-Bahrani B, Burney IA, Al-Habsi H, Ganguly SS, Tanira M. Combined polymorphism analysis of glutathione S-transferase M1/G1 andinterleukin-1B (IL-1B)/interleukin 1-receptor antagonist (IL-1RN) and gastric cancer risk in an Omani Arab population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:152–156. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815853fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoudi M, Saadat I, Omidvari S, Saadat M. Genetic polymorphisms of GSTO2, GSTM1, and GSTT1 and risk of gastriccancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:781–784. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik MA, Upadhyay R, Mittal RD, Zargar SA, Modi DR, Mittal B. Role of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzyme gene polymorphisms and interactions with environmental factors in susceptibility to gastric cancer in Kashmir Valley. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2009;40:26–32. doi: 10.1007/s12029-009-9072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy KA, Yuan JM, Chung FL, Wang XL, Van Den Berg D, Wang R, Gao YT, Yu MC. Isothiocyanates, glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk: a prospective study of men in Shanghai, China. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2652–2659. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zendehdel K, Bahmanyar S, McCarthy S, Nyren O, Andersson B, Ye W. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase genes GSTP1, GSTM1, and GSTT1 and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:2031–2038. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palli D, Polidoro S, D'Errico M, Saieva C, Guarrera S, Calcagnile AS, Sera F, Allione A, Gemma S, Zanna I, Filomena A, Testai E, Caini S, Moretti R, Gomez-Miguel MJ, Nesi G, Luzzi I, Ottini L, Masala G, Matullo G, Dogliotti E. Polymorphic DNA repair and metabolic genes: a multigenic study on gastric cancer. Mutagenesis. 2010;25:569–575. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav DS, Devi TR, Ihsan R, Mishra AK, Kaushal M, Chauhan PS, Bagadi SA, Sharma J, Zamoawia E, Verma Y, Nandkumar A, Saxena S, Kapur S. Polymorphisms of glutathione-S-transferase genes and the risk of aero digestive tract cancers in the Northeast Indian population. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:715–723. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo YP, Chen HC, Khan MA, Chen FZ, Wan XX, Tan B, Ou-Yang FD, Zhang DZ. Genetic polymorphisms of metabolic enzymes-CYP1A1, CYP2D6, GSTM1, and GSTT1, and gastric carcinoma susceptibility. Tumour Biol. 2011;32:215–222. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TV, Janssen MJ, van Oijen MG. Genetic polymorphisms in GSTA1, GSTP1, GSTT1, and GSTM1 and gastric cancer risk in a Vietnamese population. Oncol Res. 2010;18:349–355. doi: 10.3727/096504010x12626118080064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darazy M, Balbaa M, Mugharbil A, Saeed H, Sidani H, Abdel-Razzak Z. CYP1A1, CYP2E1, and GSTM1 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to colorectal and gastric cancer among Lebanese. Genet Test Mol Bio markers. 2011;15(6):423–429. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-González MA, Quintero E, Bujanda L, Nicolás D, Benito R, Strunk M, Santolaria S, Sopeña F, Badía M, Hijona E, Pérez-Aísa MA, Méndez-Sánchez IM, Thomson C, Carrera P, Piazuelo E, Jiménez P, Espinel J, Campo R, Manzano M, Geijo F, Pellisé M, González-Huix F, Espinós J, Titó L, Zaballa M, Pazo R, Lanas A. Relevance of GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 gene polymorphisms to gastric cancer susceptibility and phenotype. Mutagenesis. 2011;27(6):771–777. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ges049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakar M, Devi KR, Phukan RK, Kaur T, Deka M, Puia L, Barua D, Mahanta J, Narain K. Genetic polymorphism of glutathione S-transferases M1 and T1, tobacco habits and risk of stomach cancer in Mizoram, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(9):4725–4732. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.9.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing C, Huang ZJ, Duan YQ, Wang PH, Zhang R, Luo KS, Xiao XR. Glulathione-S-transferases gene polymorphism in prediction of gastric cancer risk by smoking and Helicobacter pylori infection status. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(7):3325–3328. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.7.3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaowen L, Hongmei Y, Hong C, Yanong W. The expression and clinical significance of miR-132 in gastric cancer patients. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming G, Lin W, Xin C, Ruixue C, Peifeng L. The association between chemosensitivity and Pgp, GST- and Topo II expression in gastric cancer. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:198. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketterer B, Harris JM, Talaska G, Meyer DJ, Pemble SE, Taylor JB, Lang NP, Kadlubar FF. The human glutathione S-transferase supergene family, its polymorphism, and its effects on susceptibility to lung cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1992;98:87–94. doi: 10.1289/ehp.929887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan C, Huimin S, Kan Z, Lingling Y, Guohua Z. RAD51 gene 135G/C polymorphism and the risk of four types of common cancers: a meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Q, Peng Q, Qin A, Chen Z, Lin L, Deng Y, Xie L, Xu J, Li H, Li T, Li S, Zhao J. Association of COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:136. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat M. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase T1 (GSTT1) and susceptibility to gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:505–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccia S, La Torre G, Gianfagna F, Mannocci A, Ricciardi G. Glutathione S-transferase T1 status and gastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis of the literature. Mutagenesis. 2006;21:115–123. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darazy M, Balbaa M, Mugharbil A, Saeed H, Hassan S, Ziad AR. CYP1A1, CYP2E1, and GSTM1 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to colorectal and gastric cancer among Lebanese. Genetic Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;15(6):1–7. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao JM, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Kim HN, Choi JS, Bae WK, Shim HJ, Kim HR, Park YK, Choi YD, Kim SH. Glutathione-S-transferase (GSTM1, GSTT1) and the risk of gastrointestinal cancer in a Korean population. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5716–5721. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu LX, Wang K, Lv FF, Chen ZY, Liu X, Zheng CL, Li WH, Zhu XD, Guo WJ, Li J. GSTM1 null allele is a risk factor for gastric cancer development in Asians. Cytokine. 2011;55(1):122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]