SYNOPSIS

Protein kinase C (PKC) has been in the limelight since the discovery three decades ago that it acts as a major receptor for the tumor-promoting phorbol esters. Phorbol esters, with their potent ability to activate two of the three classes of PKC isozymes, have remained the best pharmacological tool for directly modulating PKC activity. However, with the discovery of other phorbol ester-responsive proteins, the advent of various small-molecule and peptide modulators, and the need to distinguish isozyme-specific activity, the pharmacology of PKC has become increasingly complex. Not surprisingly, many of the compounds originally touted as direct modulators of PKC have subsequently been shown to hit many other cellular targets and, in some cases, not even directly modulate PKC. The complexities and reversals in PKC pharmacology have led to widespread confusion about the current status of the pharmacological tools available to control PKC activity. Here, we aim to clarify the cacophony in the literature regarding the current state of bona fide and discredited cellular PKC modulators, including activators, small-molecule inhibitors, and peptides, and also address the use of genetically-encoded reporters and of PKC mutants to measure the effects of these drugs on the spatiotemporal dynamics of signaling by specific isozymes.

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinase C (PKC) isozymes transduce a wide range of extracellular signals that result in generation of the lipid second messenger diacylglycerol (DAG), thereby regulating diverse cellular behaviors such as survival, growth and proliferation, migration, and apoptosis; consequently, their dysregulation is associated with a plethora of pathophysiologies. PKCs were famously discovered three decades ago to be direct signal transducers for a class of plant-derived, tumor-promoting compounds called phorbol esters [1], which potently mimic the function of the endogenous ligand DAG [2]. Within the kinome, the PKC family belongs to the larger AGC family of kinases, named for protein kinases A, G, and C and also encompassing the related kinases protein kinase N, Akt/protein kinase B, S6 kinase, and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK-1) [3].

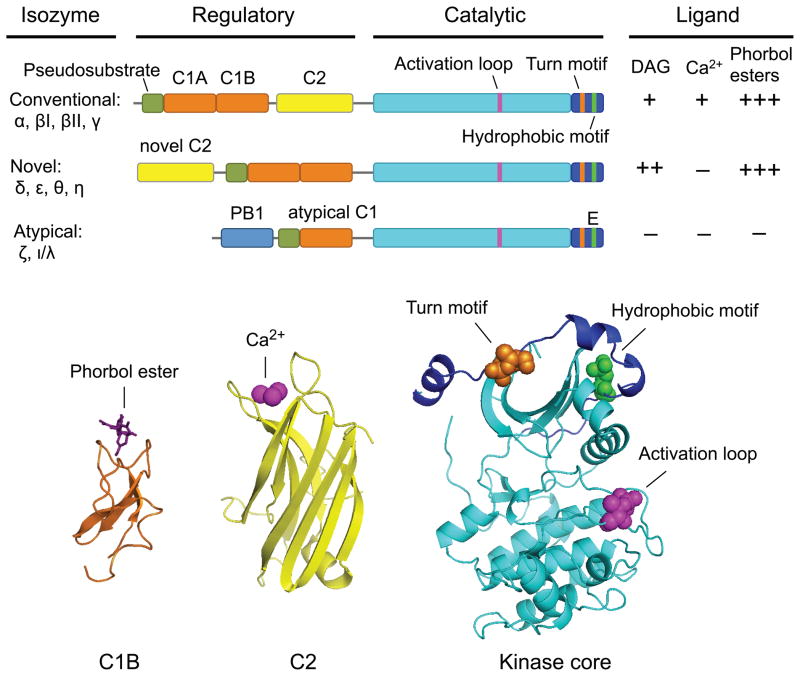

The PKC family is composed of nine genes encoding ten well-characterized full-length mammalian isozymes that serve different biological roles, are regulated differently, and are classified as either conventional, novel, or atypical according to the nature of their regulatory domains [3–9] (Figure 1). Conventional isozymes (α, the alternatively spliced βI and βII, and γ) each possess tandem C1A and C1B domains that bind to DAG or phorbol esters in membranes and a C2 domain that also binds membranes in the presence of the second messenger Ca2+. Novel isozymes (δ, ε, θ, η) likewise each contain two tandem C1 domains that bind to DAG or phorbol esters but possess a novel C2 domain that does not bind Ca2+ and does not serve as a membrane-targeting module; to compensate for the lack of contribution of the C2 domain in membrane recruitment, the C1B domain of novel isozymes has a 100-fold higher affinity for DAG compared to the C1B domain of conventional PKCs [10, 11]. Atypical isozymes (ζ, ι/λ) do not respond to either DAG or Ca2+; rather, they possess a single atypical C1 domain that retains the ability to bind anionic phospholipids and a PB1 domain that mediates protein-protein interactions. Finally, the regulatory moiety of all these isozymes contains a short autoinhibitory pseudosubstrate sequence whose occupation of the kinase substrate-binding cavity maintains these kinases in an inactive state. Alternative transcripts beyond these ten isozymes exist, most notably the brain-specific PKMζ, which consists of the catalytic domain of PKCζ [12], and recently identified PKCδ variants [13–15]. The catalytic moiety of all PKCs consists of a conserved kinase domain followed by a C-terminal tail. PKCs are constitutively processed by three ordered and tightly-coupled phosphorylations in the catalytic domain that serve to mature the enzymes into a catalytically-competent but inactive and closed conformation, in which the pseudosubstrate occupies the substrate binding cavity. These phosphorylation sites are the activation loop, phosphorylated by the upstream kinase PDK-1, and two C-terminal sites termed the turn motif and hydrophobic motif. An exception exists in the case of atypical PKCs, which possess a phosphomimetic residue at the hydrophobic motif site. Canonically, PKCs are activated not by phosphorylation at these sites, which occurs constitutively, but by their acute translocation to membranes via second messenger-mediated membrane binding by their regulatory domains, an event which allosterically removes the pseudosubstrate from the active site. Three PKC isozymes (PKCα, PKCζ, and PKCι/λ) also possess C-terminal PDZ ligands that bind PDZ domain-containing protein scaffolds [16, 17]. The structure, activation, life cycle, regulation, and signaling dynamics of PKC isozymes have been reviewed abundantly elsewhere [3–9, 18–21] and will not be addressed further here.

Figure 1. Structure and relative ligand-responsiveness of PKC isozymes.

Domain structure of PKC family members, showing autoinhibitory pseudosubstrate segment (green), C1 domains (orange), C2 domain (yellow), kinase core (cyan), and C-terminal tail (dark blue); the activation loop (pink), turn motif (orange), and hydrophobic motif (yellow) phosphorylation sites are indicated. The ligands that bind to each subfamily, along with their relative affinities, are indicated. Also shown are the crystal structures of the C1B [50], C2 [171], and kinase domains [80].

The pervasiveness of PKC as a signal transducer in so many biological contexts naturally causes its dysregulation to be implicated in a variety of diseases, such as cancer [4] and diabetes [22]. Thus, elucidating the molecular mechanisms of PKC signaling has proven valuable to an understanding of both basic signaling biology and disease mechanism in a wide range of fields. However, one consequence of the extensive reach of research involving PKC as well as of the complexity inherent in studying a family of nine genes with diverse roles and modes of regulation has been a confusion about the current status of the pharmacological tools available to modulate PKC activity, especially with regard to which compounds are currently considered to be bona fide PKC modulators and which compounds have been discredited. This review is our attempt to clarify the current status of the PKC pharmacological toolbox, including tools both for monitoring and for modulating PKC activity in cells.

GENETICALLY-ENCODED REPORTERS

The advent of genetically-encoded fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based reporters has enabled PKC pharmacology to be studied directly in situ. Although in vitro kinase activity assays have been the mainstay of PKC activity analysis for decades and continue to be the favoured method for in vitro profiling of PKC pharmacology, the cellular pharmacology of a kinase cannot always be reliably inferred from its in vitro profile [23]. Thus, cellular assays should be performed to validate the effectiveness and specificity of a pharmacological reagent against its intended target before its physiological effects are attributed to that target [24]. While cellular PKC activity can be assayed biochemically by immunoblotting cell lysates with phospho-antibodies against PKC substrates, genetically-encoded reporters provide real-time spatiotemporal information on the effects of pharmacological tools on basal and agonist-evoked PKC activity in live cells.

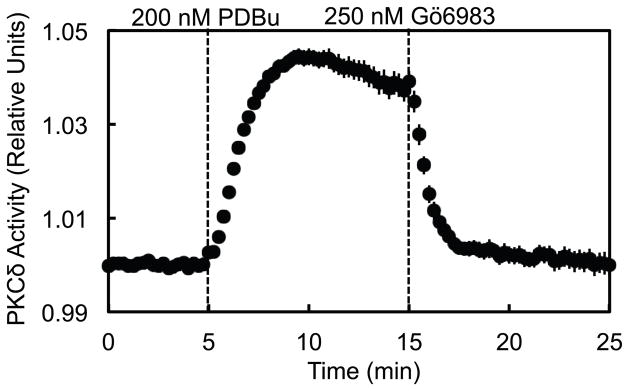

CKAR (C Kinase Activity Reporter), the first and most commonly used PKC activity reporter [25, 26], employs the modular architecture of activity reporters originally developed by Tsien and coworkers for tyrosine kinases [27] and for PKA (AKAR) [28] and subsequently also used in activity reporters for Akt/PKB (BKAR) [29] and PKD (DKAR) [30]. These reporters comprise a donor-acceptor FRET pair (typically CFP and YFP) flanking a kinase-specific substrate sequence tethered by a flexible linker to a phospho-peptide-binding module capable of binding the phosphorylated substrate sequence (reviewed in [31, 32]). Phosphorylation of the substrate sequence causes the phospho-peptide-binding module to bind the substrate sequence, resulting in a conformational change in the reporter that produces a FRET change. In the case of CKAR, the unphosphorylated reporter experiences constitutive intramolecular FRET; however, upon phosphorylation of a Thr residue in the consensus substrate sequence by PKC, the substrate sequence binds to a phospho-Thr-binding FHA2 domain, leading to conformational changes in the reporter that decrease its intramolecular FRET. This change in FRET is reversed upon dephosphorylation of the substrate peptide by cellular phosphatases. Thus, changes in the FRET of CKAR serve as a readout for PKC activity in live cells in real time (Figure 2). CKAR is an effective reporter for the activity of all PKC isozymes [33], including atypical PKCs [23]. Modification of the substrate sequence has resulted in the generation of a PKCδ-specific reporter, which has been invaluable for identifying novel signaling mechanisms of this isozyme to the nucleus and mitochondria [33, 34]. PKC activity can also be read out by measuring the phosphorylation-dependent release of the effector domain of MARCKS, an abundant PKC substrate that is released from the plasma membrane upon phosphorylation by PKC [35].

Figure 2. FRET ratio readout from a C Kinase Activity Reporter (CKAR) specific for PKCδ activity (δCKAR) reflects changes in live-cell PKCδ activity.

COS-7 cells co-transfected with δCKAR and PKCδ-RFP were monitored for FRET ratio changes over time in response to stimulation with 200 nM of the phorbol ester PDBu and subsequent inhibition with 250 nM of the bisindolylmaleimide general PKC inhibitor Gö6983. FRET ratio traces recorded from 13 cells over 3 independent experiments were normalized to baseline data and plotted as the mean ± standard error as a direct reflection of cellular PKCδ activity.

Because CKAR is a genetically-encoded reporter, it can be positioned at specific locations within the cell through the use of appropriate targeting sequences or by fusion to specific proteins. Thus, CKAR has been targeted to the plasma membrane, Golgi, nucleus, cytoplasm, and mitochondria using short localization sequences [20, 31, 36]. It has also been targeted to protein scaffolds to monitor kinase activity on these context-specific signaling hubs [37, 38]. This spatially-resolved profiling of the rate, magnitude, and duration of PKC activation has provided important insights into the subcellular contexts of PKC signaling, revealing spatiotemporal differences in PKC signaling in the presence of PKC inhibitors, PKC activators, or phosphatase inhibitors.

FRET also provides a sensitive tool to monitor the translocation of PKC to specific cellular membranes, a hallmark of its activation. Specifically, intermolecular FRET reporters consisting of subcellularly targeted CFP and separate YFP-tagged PKC constructs have been used to monitor the translocation of PKCs to various intracellular organelles. This approach was used to unveil a novel, isozyme-specific mechanism by which PKCδ interacts with mitochondria to promote mitochondrial respiration [34]. This approach has also been employed in a DAG reporter that uses the translocation of a YFP-tagged C1 domain to monitor the generation of DAG at various membranes, thereby revealing a rapid but transient rise in agonist-evoked DAG at the plasma membrane versus a slower but sustained rise in DAG at the Golgi transduced by Ca2+ [20, 36, 39]. A variety of other reporters for the PKC second messengers DAG and Ca2+ are also available [26, 40, 41], including the recent development of a reporter that simultaneously detects DAG and Ca2+ [42]. The advantages of these FRET reporters over other techniques used to study molecular interactions and localization, such as pull-downs, fractionations, and immunofluorescence, include their preservation of the physiological cellular context and spatiotemporal information, their greater sensitivity for low affinity or transient interactions, and their accommodation of experimental adjustments in response to real-time data.

ACTIVATORS

In contrast to the related Akt, which is acutely phosphorylated at the activation loop and hydrophobic motif upon agonist stimulation and whose activity can consequently be gauged using phospho-antibodies against these sites, PKC is constitutively processed by phosphorylation into a catalytically-competent but latent state [18]. Thus, immunoblotting for PKC phosphorylation at its activation loop, turn motif, or hydrophobic motif is not a reliable way to measure its activity. Rather, acute activation of PKC is achieved by the ligand-mediated engagement of its regulatory domains at membranes, which allosterically releases the autoinhibitory pseudosubstrate from its active site, shifting the enzyme into an active and open conformation. Thus, the majority of compounds that directly activate PKC act as ligands for its regulatory domains and recruit PKC to cellular membranes.

In all except the atypical PKC isozymes, tandem C1 domains serve as hydrophobic switches [43] that drive PKC translocation to membranes. Specifically, each C1 domain contains a hydrophilic cleft in an otherwise hydrophobic surface. A variety of amphipathic ligands can insert their hydrophilic moieties into this hydrophilic cleft while their hydrophobic moieties complete a hydrophobic surface on the C1 domain with high affinity for membranes (Figure 1). Although the isolated C1A and C1B domains bind ligand, only one C1 domain is engaged on membranes in the context of full-length PKC; thus, the stoichometry of ligand binding is one mol phorbol ester per mole PKC [44–46]. This section will address the most prominent C1 domain ligands, the endogenous DAG and the phorbol esters, as well as a variety of other structurally diverse C1 domain ligands isolated from many different organisms. Structural comparison of these diverse ligands has led to a pharmacophore model for PKC ligands, identifying a set of functional groups at structurally-homologous positions that is required for a ligand to interact with a PKC C1 domain [43]. Differences in the hydrophobic side chains projecting from these diverse ligands may give rise to different orientations of the C1 domain relative to the membrane, selectivity for different lipid microdomains, and different biological responses as a consequence [43]. Although PKC may be the most prominent family of C1 domain-containing proteins, one should keep in mind that six other protein families representing 18 different signaling proteins, consisting of kinases, GTPase-regulating proteins, and the signal-terminating DAG kinases, also respond to C1 ligands [47].

Diacylglycerol

The canonical generation of DAG, the endogenous C1 ligand, occurs when receptor-stimulated phospholipase C (PLC) hydrolyzes plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into the membrane-embedded DAG and the water-soluble inositol trisphosphate (IP3). The consequent IP3-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ subsequently activates phospholipases at distal membranes such as the Golgi, resulting in Ca2+-dependent elevation of DAG at the Golgi [39]. Thus, investigators should be aware that pharmacological manipulations elevating intracellular Ca2+ also elevate DAG. While DAG has a simple structure, with only one chiral center, it can have many different combinations of fatty acids attached at the C-1 and C-2 positions. Short-chain synthetic DAGs such as dioctanoyl (DiC8) glycerol and oleoacetyl glycerol (OAG) are examples of more water-soluble versions of the generally very lipophilic DAG that effectively partition into cell membranes and can be used to transiently activate PKC. Synthetic DAG-lactones with the structure of the DAG analogue constrained into the bound conformation have been designed for increased C1 binding [43]. DAG kinases, lipid kinases that phosphorylate DAG, converting it into phosphatidic acid (PA), terminate DAG signaling.

Phorbol Esters

Phorbol esters derive from the oil of the seed of the plant Croton tiglium, which has been used in traditional Chinese medicine, as a counter-irritant and cathartic in the 19th century, and as a tumor promoter on the skin of mice in the mid-20th [43]. The active components in croton oil were purified in the late 1960s as 11 diesters of a tetracyclic diterpene called phorbol, with different combinations of fatty acids attached at the 12th and 13th numbered carbons [48]. Among these, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), also known as 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), was found to be the most potent and became the paradigmatic tumor-promoting phorbol ester [43]. Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) was a derivative optimized for potency and reduced lipophilicity (and thus better aqueous solubility) that then enabled Blumberg and coworkers to demonstrate the existence of a specific, saturable receptor for phorbol esters [49], which led to the identification by Nishizuka and coworkers of PKC as the phorbol ester receptor [1]. This established the importance of PKC in cell proliferation and cancer and the employment of phorbol esters as a tool for activating PKC in cells.

As a tool for activating PKC, phorbol esters are much more potent than DAG: they bind PKC with two orders of magnitude higher affinity than DAG [44] and, additionally, are not readily metabolized (Figure 1). Thus, low nanomolar concentrations of phorbol esters suffice to produce cellular actions [43]. Their remarkable potency is illustrated by the finding that 1 mol% PMA in the lipid bilayer increases PKC’s membrane association by a staggering 4 orders of magnitude [44]. Like DAG, phorbol esters insert into the hydrophilic cleft of C1 domains, capping the C1 domain with a contiguous hydrophobic surface that retains the C1 domain on membranes [50, 51].

Phorbol esters with different substituents on the 12th and 13th carbons can produce different biological responses, and not all of them promote tumorigenesis. For example, among 12-deoxyphorbol 13-monoesters, long-chain substituted 13-tetradecanoate is both inflammatory and tumor promoting [52], whereas short-chain substituted phorbol esters are also inflammatory but not tumor promoting [53]. Blumberg and colleagues have shown that ligand hydrophobicity determines the pattern and kinetics of PKCδ translocation, in turn dictating biological response [54]. Thus, the more hydrophobic 12-deoxyphorbol 13-tetradecanoate, which causes PKCδ to translocate first to plasma membrane and then to internal membranes, is tumor promoting whereas the more hydrophilic 12-deoxyphorbol 13-phenylacetate, which causes immediate translocation of PKCδ to internal membranes, inhibits tumor promotion. The effect of lipophilicity on biological function raises caution in using phorbol esters to understand PKC signaling evoked by DAG. Furthermore, it suggests that therapeutic compounds designed to target the C1 domain should more closely resemble DAG than phorbol, an approach taken by Blumberg and co-workers [55].

Fluorescent Phorbol Esters

Natural and synthetic fluorescent phorbol esters have been used to probe the spatiotemporal dynamics of phorbol ester behavior and its interaction with PKCs. The synthetic fluorescent phorbol ester dansyl-TPA has been shown to enter freely into cells, to behave like TPA in competing with PDBu for binding and in stimulating biological activity, and to localize to ER, Golgi, mitochondria, and nuclear membranes [56, 57]. In addition, the sapintoxins, naturally occurring and potent phorbol esters derived from Sapium plants that induce inflammation but are poor tumor promoters, can act as FRET energy acceptors from the tryptophans of PKCs upon binding [57].

Using a series of homologous phorbol esters that varied in lipophilicity based on the length of a methylene spacer used to attach a fluorescent BODIPY label, Braun et al. monitored the spatiotemporal dynamics of ligand uptake in live cells [58]. They found that the greater the lipophilicity of a ligand, the slower its rate of uptake, with ligands possessing PMA-like lipophilicity requiring 30–60 min to equilibrate, while more hydrophilic ligands penetrated more quickly. However, the equilibrium distributions of all of the ligands were similar, localizing primarily to intracellular membranes and failing to accumulate visibly within either the nucleus or plasma membrane. When they simultaneously monitored the distribution kinetics of these ligands together with those of fluorescently tagged PKCα or PKCδ, they found that the presence of overexpressed PKC modified and presumably trapped the distribution of the ligands. More lipophilic ligands now accumulated first in the plasma membrane before distributing to internal membranes, while more hydrophilic ligands penetrated to internal membranes more quickly. Additionally, there were isozyme-specific differences. PKCδ colocalized well with phorbol esters throughout the timecourse. In contrast, PKCα localized to the plasma membrane regardless of the phorbol ester distribution, suggesting that PKCα localization is dominated by other factors.

Other C1 Domain Ligands

A variety of structurally diverse natural products bind with high affinity to the hydrophilic cleft of the C1 domain and activate PKC, reflecting the widespread physiological importance of PKC signal transduction. Ingenol and daphnane esters are tricyclic diterpenes structurally related to phorbol esters [43]. Ingenol mebutate, derived from the sap of Euphorbia peplis, a plant in the same family as the croton, is used as a topical treatment for the premalignant skin condition actinic keratosis [59]. Mezerein and daphnetoxin are daphnane esters [43] derived from Daphne gnidium, a poisonous Mediterranean evergreen shrub. Lyngbyatoxin and teleocidins are indole alkaloids, and aplysiatoxin is a polyacetate [43], all derived from bacteria. Iridals are triterpenoids derived from iridaceous plants [43, 60].

Bryostatins are macrocyclic lactones [43] originally isolated from the marine bryozoan Bugula neritina [61]. Bryostatins are large, complex molecules, as evidenced by the fact that bryostatin 1 has 11 chiral centers [43]. When bound to a C1 domain, the large protruding rings of bryostatin form a cap that contributes to its unique biology [43, 62]. Although bryostatins induce some of the same effects as phorbol esters, their effects tend to be more transient, and they actually antagonize the effects of phorbol esters in numerous biological contexts, including that of tumor promotion [43]. Although the mechanism of this antagonism is unclear, bryostatin 1 has been in clinical trials, primarily as an anti-cancer agent but also as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease [21, 63, 64]. Unlike phorbol esters, bryostatin 1 differentially down-regulates different PKC isozymes, with its down-regulation of PKCδ in particular exhibiting a biphasic dose-dependence [65, 66]. Furthermore, whereas most phorbol esters induce PKCδ to translocate first to the plasma membrane, then to internal membranes, bryostatin 1 induces direct translocation to internal membranes [67]. Although one study showed that tethering PKCδ to the plasma membrane promoted apoptosis, mimicking the effects of phorbol esters [68], analysis of the effects of phorbol esters whose lipophilicity covered an 8 orders of magnitude range revealed that parameters beyond lipophilicity and translocation pattern drive the biological differences between phorbol esters and bryostatins [69]. Because bryostatins are difficult both to isolate from their nonrenewable natural sources and to synthesize, investigators have designed simplified bryologues [70–72].

Ca2+ Agonists

Elevation of intracellular Ca2+ using either a natural agonist such as histamine or a pharmacological agent such as thapsigargin (an inhibitor of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase) or ionomycin (a Ca2+ ionophore) directly activates the Ca2+-sensitive conventional PKC isozymes by the binding of Ca2+ to conventional C2 domains to target the domain to the PIP2-enriched plasma membrane via electrostatic interactions. Furthermore, as noted above, Ca2+ stimulates phospholipase activity to produce DAG at internal membranes such at the Golgi [39], which activates both conventional and novel PKCs. Thus, Ca2+ elevation directly activates conventional PKC isozymes by recruiting via the C2 to membranes and indirectly activates both conventional and novel PKCs by elevating DAG to recruit via the C1 domain to membranes.

Natural Agonists

A variety of diverse physiological stimuli result in DAG production and consequently PKC activation. G-protein coupled receptor agonists such as histamine, UTP, bombesin, and lysophosphatidic acid and receptor tyrosine kinase agonists such as insulin, epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and other growth factors are commonly used to activate cellular PKC. The choice of agonist depends on the cell type and its receptor/signaling pathway signature. For example, in standard tissue-culture experiments, ATP activates PKC in MDCK cells [26], UTP activates PKC in COS cells [33, 36], and histamine activates PKC in HeLa cells [26].

SMALL-MOLECULE INHIBITORS

Active-Site Inhibitors

The vast majority of small-molecule kinase inhibitors target the ATP-binding site. When selecting from among the numerous such compounds marketed as PKC inhibitors, one should be aware of the selectivity of the inhibitor for PKCs over other kinases, the selectivity of the different PKC isozymes in general for being targeted by kinase inhibitors, and the meaning of the IC50 value for that compound. First, all PKC inhibitors possess some degree of promiscuity [73–76]. Second, among the PKCs, the atypical isozymes are the most selective, with only 1%–2% of compounds in a screen of 178 kinase inhibitors used at 500 nM inhibiting either PKCζ or PKCι [76] and fewer than 3% of compounds in a different screen of 72 kinase inhibitors used at 300 nM binding to PKCι [75]. Conventional and novel PKCs have somewhat lower levels of selectivity, with approximately 5%–10% of compounds in either screen hitting these isozymes [75, 76]. Third, the reported IC50 values of ATP-competitive inhibitors depend on the ATP concentration used in the assay [73]. This is an oft-neglected point: the intracellular concentration of ATP is on the order of 5 mM, the Km for ATP for PKC isozymes is on the order of 5 μM (see [77]), and the KI for inhibitors is typically on the order of 5 nM (e.g. [78]). With these parameters, 1 μM inhibitor may result in 95% inhibition of kinase activity in an in vitro assay with 50 μM ATP but only 17% inhibition of activity in the presence of 5 mM ATP. The majority of effective PKC inhibitors in prevalent laboratory use today are ATP-competitive derivatives of bisindolylmaleimides or indolocarbazoles.

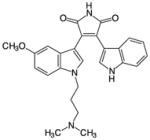

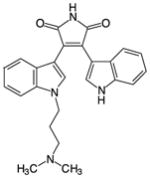

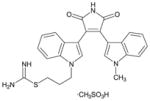

Bisindolylmaleimides

Among the bisindolylmaleimides are Gö6983 and BisI (aka Gö6850 or GF109203X), both ATP-competitive, isozyme-nonspecific, general PKC inhibitors that differ from one another by only a methoxy group. Both compounds inhibit PKC isozymes from all three classes in vitro but are more effective against conventional and novel PKCs than atypical isozymes [76, 78, 79], exhibit a moderate degree of kinase promiscuity [76], and do not inhibit the closely related PKA or PKD [76, 79]. Gö6983 inhibits PKC isozymes with IC50s ranging from 7 nM to 60 nM (at 35 μM ATP) [79], whereas BisI inhibits PKC isozymes with IC50s ranging from the nanomolar to the micromolar (at 10 μM ATP) [78]. At 500 nM, both Gö6983 and BisI inhibit conventional and novel PKCs by 80%–100%, with Gö6983 being most effective against PKCδ and BisI being most effective against PKCε, and both inhibit atypical PKCs by less than 50% [76]. In addition to inhibiting PKCs, both Gö6983 and BisI exhibit a moderate degree of promiscuity. At 500 nM, Gö6983 substantially inhibited (by >50%, greater than its inhibition of atypical PKCs) 21 other kinases in a panel of 300 mostly full-length kinases screened, whereas BisI substantially inhibited 27 [76]. Of these off-target hits, Gö6983 dramatically inhibited (by >84%, equal to or greater than its inhibition of conventional and novel PKCs) 5 of these kinases (GSK3α and RSK1-4), whereas BisI dramatically inhibited 10 (FLT3, GSK3α, GSK3β, S6K, PIM1, PIM3, and RSK1-4) [76]. At 1 μM, BisI also strongly inhibited MAPKAP-K1b but was otherwise highly selective for PKC when tested against a panel of 24 kinases [73]. X-ray crystallography shows that BisI localizes to the ATP-binding pocket of the kinase domain of PKCβII, where its dimethylamino group hydrogen bonds with the catalytic Asp470 of PKCβII [38, 80].

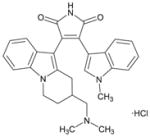

A series of ATP-competitive bisindolylmaleimides originally synthesized by Roche are commercially marketed as PKC inhibitors [81]. Among these, Ro-31-8220 and Ro-32-0432 have been characterized in screens of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Both were originally reported to inhibit rat brain PKC with an IC50 of approximately 20 nM (at 10μM ATP) and each of the conventional PKC isozymes with an IC50 between 5–37 nM, both with the highest preference for PKCα [81]. The major reported distinction between them was that Ro-32-0432 had a much higher IC50 for PKCε (108 nM) than Ro-31-8220 did (24 nM) or than either had for conventional isozymes [81]. The specificity of Ro-31-8220 was screened at 100 nM, at which concentration it inhibited PKCα by 97% and PKCζ by 75% and substantially inhibited (by ≥50%) 15 other kinases in a panel of 69 kinases screened and dramatically inhibited (by ≥80%) 9 of those [82]. At 1 μM, it inhibited PKCα by 97%, was found to have an IC50 of 33 nM for PKCα (at 100 μM ATP), substantially inhibited 7 other kinases in a panel of 24 kinases screened, and dramatically inhibited 4 of those [73]. These data are consistent with another report of the nonspecificity of Ro-31-8220 that, like the aforementioned screening studies, also found MAPKAP-K1β and S6K to be targets of this compound [83]. The specificity of Ro-32-0432 was screened at 500 nM, at which concentration it was found to be the 14th most selective inhibitor among 178 kinase inhibitors screened and the most selective PKC inhibitor of the seven included [76]. At 500 nM, Ro-32-0432 inhibited all conventional and novel PKC isozymes by >87% without exhibiting much isozyme specificity, inhibited atypical PKC isozymes by 64%–69%, substantially inhibited (by >50%) only 13 other kinases in a panel of 300 kinases screened, and dramatically inhibited (by >80%) only 7 of those [76]. Incidentally, Ro-32-0432 is one of only two kinase inhibitors among 178 screened found to be able to inhibit PKCζ substantially [76].

A variety of other indolylmaleimide-based PKC inhibitors have been developed, including several that have been advanced for clinical development. Sotrastaurin (AEB071) is a novel indolylmaleimide that potently and selectively inhibits novel and conventional PKCs, with nanomolar or sub-nanomolar IC50s for these PKCs versus above-micromolar or near-micromolar IC50s for atypical PKCs and all 32 other kinases screened (at 10 μM ATP) [84, 85]. As an immunosuppressive that markedly inhibits PKCθ in T cells and T-cell activation and proliferation [84], sotrastaurin has been in clinical trials for psoriasis [21, 86] and transplant rejection [85]. Enzastaurin (LY317615) and ruboxistaurin (LY333531) are PKCβ-selective bisindolylmaleimides with IC50s of 4.7–6 nM for PKCβ (at 30 μM ATP), 10- to >100-fold that for other PKC isozymes [87, 88]. Both exhibit modest promiscuity. At 1 μM, enzastaurin did not substantially inhibit any of 28 other kinases tested [89], and ruboxistaurin is selective for PKCβ over PKA, CaMK, src, and casein kinase [87] and, at 100 nM, substantially inhibited 12 other kinases in a panel of 69 kinases screened, dramatically inhibiting 4 of them [82]. Enzastaurin, which inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human tumor cell cultures and xenografts, is in oncology clinical trials as an anti-angiogenic [21, 82, 89, 90]. Ruboxistaurin was in clinical trials for the treatment of diabetic vascular dysfunction that were discontinued during Phase III [21, 82, 91]. Anilino-monoindolylmaleimides, compounds in which one of the indoles of bisindolylmaleimide has been replaced with aniline, are selective for PKCβ over PKCα or PKCε by approximately an order of magnitude [88]. However, one such compound, termed simply “PKCβ inhibitor”, when used at 500 nM, was reported to also substantially inhibit PKCα, PKCη, and PKCθ and to dramatically inhibit PKCδ and PKCε; nonetheless, this report ranked this compound as the second most selective PKC inhibitor of the seven included, after Ro-32-0432 [76].

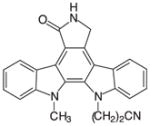

Indolocarbazoles

Among the indolocarbazoles are the ATP-competitive inhibitors Gö6976 and staurosporine. Gö6976 inhibits conventional PKC isozymes at nanomolar concentrations in vitro but does not effectively inhibit novel or atypical PKC isozymes even at micromolar concentrations [78]. The potency and specificity of Gö6976 has been characterized in multiple studies of kinase inhibitor selectivity [73, 76, 82]. At 100 nM, Gö6976 inhibited PKCα by 98% and PKCζ by only 22%, and the other PKC isozymes were not tested [82]. At 500 nM, it inhibited PKCα, PKCβI, and PKCβII by more than 80%; PKCδ, PKCε, and PKCη by 41%–65%; PKCγ and PKCθ by less than 28%; and atypical PKC isozymes by less than 13% [76]. At 1 μM, it inhibited PKCα by 93%, and the other isozymes were not tested [73]. However, these studies also reveal that Gö6976 is a highly promiscuous inhibitor of other kinases. At 100 nM, it substantially inhibited (by ≥50%) 38 other kinases in a panel of 69 kinases screened and dramatically inhibited (by >80%) 19 of those [82]. At 500 nM, it was the seventh most promiscuous compound in a panel of 178 kinase inhibitors screened, substantially inhibiting (by >50%) 107 kinases other than PKCs in a panel of 300 kinases screened and dramatically inhibiting (by >80%) 52 of those [76]. At 1 uM, Gö6976 substantially inhibited (by ≥50%) 11 other kinases in a panel of 24 kinases screened and dramatically inhibited (by >80%) 7 of those [73]. The dramatically inhibited off-target hits of Gö6976 found by both the Cohen and Peterson groups are Aurora B, CaMKK2, CDK2-cyclin A, CHK1, GSK3β, MSK1, MST2, PAK4, PAK5, PAK6, PHK, PIM3, PKD1 [79], RSK1, and RSK2 [73, 76, 82]. Parallel usage of Gö6976 and a general PKC inhibitor such as Gö6983 in an experiment can be used to analyze whether a biological effect is the result of activity by an off-target kinase (inhibited by Gö6976 but not Gö6983) or whether it is the result of novel or possibly atypical PKC activity (inhibited by Gö6983 but not Gö6976).

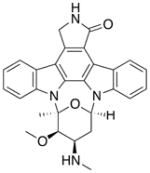

Staurosporine represents the original indolocarbazole isolated from Streptomyces staurosporeus [92, 93] and is a highly promiscuous, ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor [38, 74–76] that potently binds to and inhibits most if not all PKC isozymes in vitro [74–76, 81]. Indeed, staurosporine has been ranked as the most nonselective commercially available kinase inhibitor in multiple unbiased high-throughput screens of kinase inhibitor selectivity [74–76]. Despite its promiscuity and one report that staurosporine does directly inhibit PKCζ in vitro [76], other in vitro studies report that staurosporine does not inhibit either PKCζ [94] or PKMζ [95], a brain-specific alternative transcript of PKCζ encoding its catalytic domain [12]. Consequently, staurosporine has been used as a negative control inhibitor in studies that implicate PKMζ in long-term memory [95, 96]. However, staurosporine does bind with nanomolar affinity to and inhibits PDK-1 [74, 76], the upstream kinase that catalyzes the activation loop phosphorylation required for the catalytic competence of all PKC isozymes [18, 97], including that of PKCζ [98, 99]. Thus, even though staurosporine may not have inhibited PKMζ in vitro in some studies, it does inhibit PKMζ activity in cells and tissues, as measured both by using CKAR and by immunoblotting for the phosphorylation of endogenous PKMζ substrates, by inhibiting PDK-1’s phosphorylation of PKMζ’s activation loop [23]. Effects such as this, which would be overlooked in in vitro assays, demonstrate the importance of verifying the targets of a drug in the complex milieu of cells and tissues before drawing physiological conclusions based solely on its in vitro pharmacological profile. Additionally, UCN01 (hydroxystaurosporine) is a staurosporine derivative that also potently inhibits many kinases in addition to PKCs [73, 82], does not inhibit PKCζ in vitro [82, 94], but does inhibit PDK-1 [73, 82, 100].

Active Site Inhibitors with Additional Binding Determinants

A recent chemical library screen identified thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine-based compounds that bind competitively with respect to ATP in the nucleotide binding pocket of atypical PKC isozymes and, additionally, have a benzyl group that displaces a key phenylalanine that structures the adenosine binding motif [101]. Thus, not only is ATP binding inhibited, but the adenosine binding motif becomes disordered. These promising compounds are effective in cells and serve as a paradigm for isozyme-selective inhibition by coupling active site-inhibition with isozyme-selective binding determinants.

Active-Site Occupation by an Inhibitor Prevents PKC Dephosphorylation

An interesting and counterintuitive effect of PKC active-site inhibitors is their stabilization of the constitutive processing phosphorylations on PKC [102, 103]. Cameron et al. [102] first observed an increase in the steady-state levels of these processing phosphorylations on the normally unprimed kinase-dead constructs of PKCε and PKCα upon incubation with ATP-competitive inhibitors such as BisI, Gö6983, or Gö6976, but not with the non-active-site inhibitor calphostin C. The same effect was observed by Okuzumi et al. [104] for the analogous regulatory phosphorylations on Akt. These observations were recapitulated for PKCβII in vitro and in cells by Gould et al. [103], who further showed that the inhibitor-induced increase in steady-state levels of processing phosphorylations results from protection against dephosphorylation rather than promotion of phosphorylation. Specifically, pulse-chase analysis revealed that incubation with BisI had no effect on the rate of processing phosphorylations but significantly slowed phorbol ester-triggered dephosphorylation. Similarly, occupation of active site of Akt by ATP-competitive inhibitors or by ATP itself protects Akt from dephosphorylation by restricting phosphatase access [105, 106]. Finally, the same protection from dephosphorylation can be observed upon active-site occupation by peptide substrates or by the pseudosubstrate peptide of PKC itself when in its inactive conformation [107, 108]. At the structural level, active-site occupancy causes the C-terminal tail of PKC [80] and PKA [109, 110], where the turn and hydrophobic motifs reside, to go from a highly flexible to a highly ordered state.

Scaffolded PKC Is Refractory to Inhibition by Active-Site Inhibitors

Protein scaffolds such as A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) and receptors for activated C-kinase (RACKs) organize PKCs, their substrates, and their modulators into subcellular complexes that coordinate signaling. It was recently discovered that PKC bound to protein scaffolds such as AKAP79 is refractory to inhibition by ATP-competitive inhibitors such as BisI or staurosporine [38]. The likely explanation is that the apparent concentration of substrate, when anchored in such close proximity to an enzyme, is so high in the neighborhood of the enzyme that active-site inhibitors become ineffective. Thus, the context of PKC’s interactions with protein scaffolds not only determines the spatiotemporal dynamics and substrate specificity of PKC in cells but also appears to blunt the effectiveness of active-site inhibitors against PKC, shifting its pharmacological profile. In contrast, non-active-site inhibitors such as BisIV or calphostin C maintain their effectiveness against AKAP79-scaffolded PKC [38].

Non-Active-Site Inhibitors

Although most drug development efforts against kinases have focused on the ATP-binding site, the kinome-wide conservation of the active site results in widespread drug promiscuity among active-site inhibitors. Structure-based design that targets less conserved pockets within the kinase domain or targeting noncatalytic domains to generate drugs that inhibit kinases by an allosteric mechanism could produce more selective kinase inhibitors. One example of a non-active-site PKC inhibitor is BisIV. Like the active-site PKC inhibitor BisI, BisIV is a bisindolylmaleimide-derived general PKC inhibitor. But, unlike BisI, from which it differs only by the absence of the dimethylamino group that hydrogen bonds with the catalytic Asp, BisIV is uncompetitive with respect to substrate [38]. While BisIV is a much less potent inhibitor than BisI, Gö6983, or Gö6976, it is also more specific to PKC [73, 76]. Because it is not an active-site inhibitor, despite its structural similarity to BisI, BisIV treatment does not stabilize PKC’s priming phosphorylations [103] and remains effective against scaffolded PKC [38]. The same are true of calphostin C, which targets the DAG-binding sites of PKC in a light-dependent manner [38, 102, 111, 112]. Another example of allosteric PKC inhibition involves modulation of a site called the PIF-pocket in the N-lobe of AGC kinases, a site that binds the phosphorylated hydrophobic motif segment [113]. Biondi and coworkers have recently identified benzimidazole compounds (namely PS171 and PS168) that allosterically inhibit PKCζ in vitro by binding its PIF-pocket and, additionally, inhibit PKCζ-dependent NF-kB activation in cells [113, 114]. These allosteric modulators are the first bona fide inhibitors of PKCζ shown to have cellular effects on functions mediated by this kinase.

Inhibitors of PKC Maturation

Upon translation, conventional and novel PKCs are constitutively processed by phosphorylation at the activation loop, turn motif, and hydrophobic motif to mature them into a stable and catalytically-competent but inactive conformation [3, 19]. Species that are not processed by phosphorylation are degraded by the proteasome. Thus, the steady-state levels of conventional and novel PKC isozymes are extremely low in cells lacking the upstream kinase PDK-1 [115]. However, active site inhibitors of PDK-1 are relatively ineffective at inhibiting the processing of these PKC isozymes, underscoring the concept that kinases scaffolded on/next to their substrates are refractory to active-site inhibitors [38]. In contrast, atypical PKC isozymes, which have a phosphomimetic at the hydrophobic motif, are sensitive to inhibition by PDK-1, and phosphorylation of their activation loop acutely controls activity.

The initiation of PKC maturation is promoted by the chaperone Hsp90 and its co-chaperone Cdc37, which bind to newly synthesized PKC via a molecular clamp formed between a conserved PXXP motif in the C-terminal tail of PKC and a conserved Tyr in the αE-helix of the kinase core [116]. Thus, Hsp90 inhibitors such as geldanamycin and 17-AAG, which inhibit the ATP binding and hydrolysis essential for Hsp90’s protein folding function, and celastrol, which inhibits both Hsp90’s ATP binding and its interaction with Cdc37, inhibit PKC hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and enzyme maturation [116].

Phosphorylations of both the turn and hydrophobic motifs have been shown to depend on mTORC2 and do not occur in mTORC2-deficient cells [91, 117–119], although it is unclear whether mTORC2 directly phosphorylates PKC at one or both of these sites or whether it performs a chaperoning role as Hsp90 does to prime PKC for phosphorylation by another mechanism such as autophosphorylation, as observed in vitro [3]. Thus, second-generation ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors such as Torin1 can reduce the steady-state levels of PKC by preventing priming phosphorylations [120]; they do not, however, acutely inhibit PKC activity.

Inhibitors of PKC Down-Regulation

In the mature but inactive conformation of PKC, its pseudosubstrate peptide is lodged in the kinase active site, preventing it from phosphorylating substrates. Agonist stimulation induces PKC to translocate to intracellular membranes, where membrane engagement of its regulatory domains allosterically removes the pseudosubstrate from the active site, enabling it to phosphorylate substrates. In this open conformation, PKCs become more sensitive to dephosphorylation by two orders of magnitude [107], and sustained activation of PKC causes PKC to become dephosphorylated and degraded, a process termed down-regulation [3, 19]. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 controls the down-regulation of conventional PKCs by docking onto its hydrophobic motif and isomerizing the phospho-Thr-Pro peptide bond of the turn motif from a cis to a trans conformation, converting PKC into a down-regulation-sensitive species [121]. Thus, Pin1 inhibitors such as PiB (diethyl-1,3,6,8-tetrahydro-1,3,6,8-tetraoxobenzo[lmn][3,8]phenanthroline-2,7-diacetate) inhibit the down-regulation of conventional PKCs and trap them in the active state [121]. The PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) dephosphorylates the hydrophobic motif of conventional and novel PKCs, the first event in the down-regulation of PKC, while an okadaic acid-sensitive phosphatase dephosphorylates the turn motif and activation loop [122]. Thus, phosphatase inhibitors that can inhibit PHLPP or the turn motif phosphatase or mutation of the hydrophobic motif to a phosphomimetic Glu also inhibit down-regulation and trap PKC in the active state [122].

PEPTIDE DRUGS

Peptides Derived from Receptors for Activated C Kinase (RACKs)

PKC isozymes with overlapping activator responsiveness and substrate specificities frequently coexist in the same tissues, but their distinct subcellular localizations account in part for their isozyme-specific functions [123]. The subcellular localizations of PKC isozymes are determined not only by lipid interactions, but in part by their interactions with scaffold proteins such as RACKs, structurally unrelated adaptor or scaffold proteins that are functionally defined by their ability to bind and activate specific PKC isozymes and were first identified by Mochly-Rosen and coworkers in the particulate fraction of cells over two decades ago [124]. RACKs are known to bind the regulatory domains and variable N- and C-terminal sequences of PKCs and to activate them by competing for binding against autoinhibitory sequences within PKCs, relieving their autoinhibition and locking them into an active conformation that exposes their substrate-binding site [123, 125]. For example, the first and most archetypal autoinhibitory sequence to be discovered in PKC is its pseudosubstrate peptide [126]. RACKs can thus control both PKC isozyme-specific localization (and hence substrate proximity) and activation. Another set of anchoring proteins was proposed to exist for inactive PKC isozymes (RICKs) [123].

Taking advantage of the isozyme-specific interactions between PKCs and RACKs to address the dearth of isozyme-specific PKC activators and inhibitors, Mochly-Rosen and colleagues developed a series of first-generation peptides, derived from either PKCs or RACKs and based on their interaction sites, that interfere with the protein-protein interactions between PKCs and RACKs [123, 127]. In cases where a RACK acts to scaffold PKC next to its substrates, peptides that interfere with PKC binding to RACK will inhibit PKC signal transduction, and such peptides act as isozyme-specific inhibitors of PKC translocation and activity [123, 127]. By the same principle, peptides that interfere with PKC-RICK interaction should act as isozyme-specific PKC agonists [123]. However, peptides called pseudo-RACKs (ψRACKs) that mimic the autoinhibition-relieving properties of RACKs without affecting the proximity of PKCs to their substrates act as activators of PKC translocation and activity [127]. Second generation peptide inhibitors may interfere with the interaction between PKC and a specific substrate on the same RACK [127]. The advantages of peptide drugs are their flexibility and naturally selected fit for a particular protein interaction site, which enable them to interact more effectively and specifically with proteins than rigid small molecules and to interfere with multiple interaction sites on a protein [127]. Isozyme-specific peptide drugs such as PKCε-activating and PKCδ-inhibiting peptides have been used as pharmacological modulators of PKC activity in basic research and animal models of disease, in particular improving outcomes in models of cardiovascular diseases and interventions [127, 128].

Pseudosubstrate Peptides and Zeta Inhibitory Peptide (ZIP)

ZIP is a myristoylated putative PKCζ-inhibiting peptide composed of the pseudosubstrate sequence of PKCζ. ZIP has been employed prominently in the past decade as the primary pharmacological tool with which Sacktor and colleagues have attempted to establish PKMζ, an alternative transcript of PKCζ that encodes its catalytic domain, as the kinase necessary and sufficient for the maintenance of long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission and for learning and memory [95, 96, 129–131]. ZIP does indeed inhibit both PKCζ and PKMζ in vitro [23, 95] and consistently abolishes LTP and various measures of memory in rats [95, 96, 129–131]. However, the effectiveness of ZIP in targeting PKMζ in the vastly more complex environment of cells and tissues was never determined until 2012, when cellular studies revealed that this peptide does not inhibit PKMζ in mammalian cells or rat hippocampal brain slices in contexts where the positive control staurosporine does [23]. In vitro, the highly basic ZIP (and scrambled ZIP [23]) may inhibit PKMζ by competing with the basic PKC substrate peptide for active-site occupation; however, in cells, the effective concentration of these basic peptides is considerably lower as a result of binding to any number of nonspecific, negatively charged surfaces in a complex cellular environment. It is also possible that the pseudosubstrate sequence of PKCζ binds with much higher affinity to a cellular target and that ZIP disrupts this interaction rather than the enzymatic activity of PKMζ. Furthermore, in contrast to the regulatory mechanism of conventional PKCs, a recent study reports that the atypical C1 domain rather than the pseudosubstrate of PKCζ is primarily responsible for allosterically autoinhibiting PKCζ activity; deletion of the pseudosubstrate does not significantly increase the activity of the kinase [114]. Rather, the function of this highly positively charged pseudosubstrate is to interact with other regions on the protein to provide thermal stability; lipid-activated removal of the pseudosubstrate from the kinase active site results in loss of PKCζ stability [114]. Recent reports that mice lacking PKMζ have normal memory and learning, and continue to be sensitive to ZIP, confirm cellular pharmacological data that the target of ZIP is not PKMζ [132, 133]. Thus, the cellular pharmacology of PKMζ contrasts with its in vitro profile, underscoring the importance of establishing the cellular activity of pharmacological tools.

It is perhaps not surprising that pseudosubstrate-derived peptides are not effective PKC inhibitors in cells. First, the affinities of these peptides for PKC are several orders of magnitude lower than what is required for them to effectively bind PKC in cells. Peptides that effectively inhibit the related kinase PKA in cells bind with nanomolar affinity. PKI, the gold standard in inhibitory peptides that was originally characterized by John Scott, binds the catalytic subunit of PKA with a Kd of 4.8 nM [134]. Peptides such as Ht31 and AKAP-IS that effectively disrupt localized PKA signaling by displacing PKA from AKAPs bind with affinities of 2–4 nM [135]. In contrast, the affinities of pseudousbstrate peptides for PKC are in the micromolar range. Thus, the field awaits the generation of higher-affinity peptides before peptides as a class can be applied as effective pharmacological inhibitors of PKC in cells. Second, although an intramolecular pseudosubstrate peptide may be able to autoinhibit a PKC isozyme, the isolated peptides may not be isozyme- or even PKC-specific inhibitors. Indeed, the pseudosubstrate peptide of PKCα is not a PKC-specific inhibitor, inhibiting also CaMKII and MLCK at micromolar concentrations in vitro [136]. Furthermore, based on the unbiased screen of Cantley and colleagues for the optimal substrate sequences of individual PKC isozymes using an oriented peptide library, there is limited isozyme selectivity in substrate sequence recognition [137]. Thus, due to the demonstrated lack of specificity of pseudosubstrate-derived peptide inhibitors, results obtained using them should be interpreted with caution.

DISCREDITED PKC INHIBITORS

Rottlerin

Rottlerin, also known as mallotoxin, was originally reported to be a PKC and CaMKIII inhibitor that inhibited PKCδ (IC50 = 3–6 μM) with 5- to 10-fold greater potency than conventional PKC isozymes and 13- to 33-fold greater potency than other novel and atypical PKC isozymes tested in vitro [138]. Based on this report, hundreds of published studies have used rottlerin to draw conclusions about the role of PKCδ in a variety of cellular processes. It has been over a decade, however, since rottlerin was debunked as a PKCδ inhibitor, with multiple independent investigators finding no effect of even 10–20 μM rottlerin on PKCδ (or PKCα or PKCζ) activity in vitro [73, 82, 139]. Instead, rottlerin strongly inhibits many other protein kinases such as PRAK and MAPKAP-K2 [73] or such as CHK2, PLK1, PIM3, and SRPK1 [82] much more potently in vitro. Possible explanations for this disparity include the use of the generic PKC substrate protamine in the original report, in contrast with the use of the optimal PKCδ substrate peptide in subsequent studies [139], and the presence of contaminants in the rottlerin used in the original report. Furthermore, treatment of cells with 10 μM rottlerin does not inhibit phorbol ester-stimulated PKCδ activity, as measured using the isozyme-specific PKCδ activity reporter δCKAR, under conditions where 750 nM Gö6983 completely abolishes it [34]. Additionally, the cellular effects of rottlerin are not reproduced by the use of bona fide PKC inhibitors, kinase-dead PKCδ, or siRNA against PKCδ or by down-regulation of PKCδ with prolonged phorbol ester treatment [140]. Even more damningly, rottlerin continues to produce its effects in the absence of PKCδ activity (when inhibited by the bona fide PKC inhibitor BisI) [139] or in the absence of PKCδ protein (in cells from PKCδ knockout mice or when down-regulated by phorbol esters) [140–143].

The widespread cellular effects of rottlerin on apoptosis and mitochondrial ROS production can be attributed to its activity as a mitochondrial uncoupler [139, 140, 144], a compound that uncouples ATP synthesis from respiration. Like the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP, which collapses the proton gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane by acting as a protonophore, rottlerin depolarizes the mitochondrial membrane potential that drives ATP synthesis, thereby increasing the cellular oxygen consumption rate while reducing cellular ATP levels, activating AMP kinase, and changing the phosphorylation of many signaling proteins [139, 140]. Among these phosphorylation changes, Tyr phosphorylation of PKCδ, which can activate PKCδ in certain contexts, can be indirectly blocked by rottlerin [139, 140]. While these effects are not mimicked by PKC inhibitors, they are mimicked by other mitochondrial uncouplers [139]. Responsible drug vendors should follow the lead of LC Labs, which has discontinued its sales of rottlerin, by at least ceasing to market rottlerin as a PKCδ inhibitor.

Chelerythrine

Chelerythrine is a benzophenanthridine alkaloid that was originally reported in 1990 to be a potent in vitro substrate-competitive active-site inhibitor of PKC purified from rat brain, with an IC50 of 0.66 μM (at 100 μM ATP), selectivity for PKC over PKA, CaM kinase, and an unspecified tyrosine kinase, and antitumoral activity [145]. Since then, multiple independent investigators have debunked chelerythrine as a PKC inhibitor, both in vitro [73, 76, 146] and in cells [103]. In in vitro studies that contrast directly with the original report, chelerythrine did not inhibit either the basal or phorbol ester-induced activity of PKC purified from rat, mouse, or calf brain, whereas staurosporine as a positive control did [146]. In fact, concentrations of chelerythrine up to 100 μM enhanced the activity of PKC purified from rat and mouse brain [146]. At 500 nM, chelerythrine did not inhibit any PKC isozyme (purified from insect cells) or any other kinase in a panel of 300 kinases assayed in vitro [76]. At 10 μM, chelerythrine did not inhibit PKCα or any other protein kinase in a panel of 24 kinases assayed in vitro [73]. At 10 μM or less, chelerythrine did not inhibit PKCζ in vitro [147]. Because chelerythrine inhibited only lipid-stimulated and not basal PKC activity in the original report, we speculate that the positive charge of this amphipathic molecule may have been responsible for its reported effect by nonspecifically reducing the surface charge of the anionic membranes needed as a cofactor in PKC activation. In cellular studies, concentrations of chelerythrine up to 10 μM produced no effect on endogenous PKC in contexts where positive control PKC inhibitors did suppress PKC activity [103]. Furthermore, cellular effects produced by chelerythrine have been found to be independent of PKC [148].

The continued marketing of chelerythrine as a specific PKC inhibitor has resulted in the inappropriate attribution of numerous and wide-ranging biological effects to PKC activity. Most prominently in the past decade, chelerythrine has been employed in the neurobiology field to implicate PKMζ in long-term memory maintenance [95, 130], even though the effectiveness of chelerythrine in inhibiting PKMζ in the complex milieu of mammalian cells and tissues had never been established. In fact, it was recently demonstrated that chelerythrine does not inhibit PKMζ in either mammalian cell lines or rat hippocampal brain slices [23]. Rather, chelerythrine is a cytotoxic and apoptosis-inducing drug [23, 145, 149, 150] with mechanisms of action independent of PKC. For example, chelerythrine has been shown by NMR experiments to bind and inhibit the pro-survival Bcl-2 family member BclXL [150, 151]. Furthermore, the imidium bond in chelerythrine can interact with the thiol groups of alanine aminotransferase [152]. The closely related benzophenanthradine alkaloid sanguinarine has also been shown to bind BclXL [151], and its imidium bond has also been shown to react with the nucleophilic and anionic moieties of amino acids and to intercalate into DNA [151, 153].

GENETIC MANIPULATION OF PKC

Kinase-Dead Mutants

As a complementary or alternative approach to pharmacological inhibition, studies frequently make use of kinase-dead PKC constructs to address the role of PKC activity in biological processes. These kinase-dead constructs are all generated by mutating one of a number of conserved residues in the active site of PKC, which renders the mutant kinase itself essentially inactive and potentially also generates a dominant-negative effect in cells from competition against endogenous PKC [154]. However, such mutations often compromise phosphorylation of the priming sites on PKC. Thus, priming phosphorylations of mutants should be verified, and effects obtained using unprimed mutants should be treated with caution, as they may be the artifactual result of improper protein conformation, rather than of loss of kinase activity per se. Furthermore, most kinase-dead mutations reduce activity significantly (10–100 fold) but do not entirely abolish it. As a consequence, some “kinase-dead” constructs can still autophosphorylate their C-terminal priming sites. Kinase-dead PKCs that remain unphosphorylated are typically degraded or may localize to a different spatial compartment than processed PKCs, potentially producing off-target effects.

The most commonly mutated residue reported in the literature to generate a kinase-dead PKC corresponds to K376 of mouse PKCδ and is mutated either to Met or Arg. This positively charged Lys residue hydrogen bonds with the α and β phosphates of ATP and forms an ion pair with a conserved Glu in the C-helix that stabilizes the N-lobe of the kinase domain [102]. Thus, mutation of this residue inhibits activity by impairing phosphoryl transfer.

Another conserved residue that has been mutated to generate a kinase-dead PKC corresponds to D471 of mouse PKCδ and is mutated to either Ala or Asn. This Asp residue acts as the catalytic base to abstract the proton of the hydroxyl group of the Ser or Thr residue on the substrate to coordinate it for phosphorylation [102]. Mutation of this residue has been reported to produce no loss of priming phosphorylations on PKCε and PKCα [102]. However, although this mutant in PKCε loses all in vitro kinase activity [102], the naturally occurring substitution of Asn for the catalytic Asp in the pseudokinase ErbB3 preserves enough residual kinase activity for ErbB3 to autophosphorylate [155].

A third conserved residue that was recently mutated to inactivate a kinase corresponds to A374 of mouse PKCδ and was originally mutated in the kinase suppressor of Ras (KSR1) to a Phe [156]. This Ala residue in the N-lobe of kinases forms part of a three-dimensional catalytic hydrophobic spine that stabilizes the active conformation of a kinase and interacts with the top of the adenine ring in ATP [156]. According to molecular modeling in CRAF, this Ala to Phe mutation may stabilize the catalytic hydrophobic spine to maintain an active conformation while blocking ATP binding, creating a pseudokinase [156]. Indeed, the KSR1 A/F mutant does not bind ATP and is not active (it cannot enable RasV12 transformation-induced colony formation) but retains its scaffolding of BRAF and CRAF [156].

Gatekeeper Mutants and Chemical Genetics

Chemical genetics approaches to kinase biology, pioneered by the lab of Kevan Shokat in the late 1990s, afford an elegant approach to interrogate the role played by the intrinsic catalytic activity of a particular PKC isozyme [157–160]. Specifically, the genetic engineering of protein kinases to preferentially bind to co-engineered small-molecule ligands provides a method to specifically target the kinase of interest. These ligands are either modified nucleotides that can be used to radiolabel and thus identify the substrates specifically phosphorylated by the engineered kinase or small-molecule inhibitors derived from a pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP) inhibitor of Src family kinases that specifically inhibit the engineered kinase. The chemical genetics approach to identifying kinase-specific substrates was made possible by the discovery that, when a certain bulky, conserved hydrophobic residue in the kinase active site that interacts with the adenine N6 amino group on ATP is mutated to a smaller Ala or Gly, this mutation slightly enlarges the active site to accommodate a modified, bulkier ATP that cannot bind the active site of wild-type kinases. This critical residue has become known as the gatekeeper residue for its role in guarding the active site of wild-type kinases against the entry of engineered ligands and allowing their entry in gatekeeper mutants. The chemical genetics approach to inhibiting a specific kinase quickly followed when mutation of the same bulky residue was found to accommodate the binding of cell-permeable, mutant-selective, PP-derived small-molecule inhibitors, whose N4 position corresponds to the N6 position of ATP. This chemical genetics approach was recently employed for mechanistic studies to demonstrate a role for the intrinsic catalytic activity of PKCδ in its isozyme-specific interaction with mitochondria [34], as well as for an organism based screen to identify cellular substrates of PKCι [161].

Genetic deletion of depletion of PKC

PKC isozymes, in general, have relatively long half-lives so effective knock-down by siRNA can be challenging [68, 162, 163]. However, with the exception of PKCi, knock-out of PKC isozymes results in viable mice (e.g. [133, 164–168]). Thus, analysis of mouse embryonic fibroblasts from isozyme-specific knock-out mice provides a helpful tool for examining isozyme-specific function (eg. [16, 169]).

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

We have aimed here to clarify the current status and mechanisms of action of the bona fide and discredited pharmacological tools in the PKC toolbox. A wide range of compounds in the forms of activators, small-molecule inhibitors, and peptides have emerged to modulate the catalytic activity, subcellular distribution, protein interactions, and life cycle of PKC. Coupled to the advent of FRET-based reporters to examine the spatio-temporal dynamics of PKC signaling, tools should no longer limit our accurate assessment of the biological function of PKC. Given the importance of time and space in cell signaling, future advances in developing tools that reversibly turn on or off specific isozymes at specific cellular locations, as well as tools that allow supra-high definition of PKC subcellular locations, will be welcomed additions to the PKC toolbox. In this regard, novel and light-sensitive tags such as the recently-described mini-SOG (a 106 amino acid tag that whose light-dependent generation of singlet oxygen affords a way to locally inactivate proteins, as well as to visualize with high resolution electron microscopy) holds promise for defining the precise cellular location of specific isozymes [170]. In the meantime, it is our hope that, in refining the PKC pharmacological toolbox, we will assist investigators in selecting the best tools for studying the role of PKC in their systems and minimize the formation of erroneous conclusions from the use of nonspecific compounds.

Table 1.

Small-molecule active-site inhibitors: in vitro potency, isozyme selectivity, and promiscuity

| Inhibitor | IC50 | Conc. | % Inhibition of PKC Isozymes | % Inhibition of Non-PKC (total tested) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Novel | Atypical | Inhibited by ≥50% | Inhibited by ≥80%* | |||

| Bisindolylmaleimides | |||||||

Gö6983

|

6–7 nM for α, β, γ, 10 nM for δ 60 nM for ζ (35 μM ATP) [70] | 500 nM [68] | 80–100% | <50% | 7.2% (290) | 1.7% (290) | |

BisI

|

8.4 nM for α, 18 nM for βI, 210 nM for δ, 132 nM for ε, 5.8 μ for ζ (10 μM ATP) [69] | 500 nM [68] | 80–100% | <50% | 9.3% (290) | 3.4% (290) | |

| 1 μM [65] | α by 96% | N.T | N.T | 17% (23) | 4.3% (23) | ||

Ro-31-8220

|

5–27 nM for cPKC, 24 nM for ε (10 μM ATP) [72]; 33 nM for PKCα (100 μM ATP) [65] | 100 nM [73] | α by 97% | N.T | ζ by 75% | 22% (67) | 13% (67) |

| 1 μM [65] | α by 97% | N.T | N.T | 30% (23) | 17% (23) | ||

Ro-32-0432

|

9–37 nM for cPKC, 108 nM for PKCε (10 μM ATP) [72]; | 500 nM [68] | >87% | 64–69% | 4.5% (290) | 2.4% (290) | |

| Indolocarbazoles | |||||||

Gö6976

|

2.3 nM for α, 6.2 for βI, 7.9 for rat brain PKC (10 μM ATP) [69] | 100 nM [73] | α by 98% | N.T | ζ by 22% | 57% (67) | 28% (67) |

| 500 nM [68] | α, βI, βII by >80%, γ by 28% | δ, ε, η by 41–65%, θ by 24% | ζ by 13%, ι by 8% | 37% (290) | 18% (290) | ||

| 1 μM [65] | α by 93% | N.T | N.T | 48% (23) | 30% (23) | ||

Staurosporine

|

11–32 nM for cPKC, PKCε (10 μM ATP) [72]; 2.7 nM for rat brain PKC (5 μM ATP) [84] not detected for PKCζ [69] | 500 nM [68] | 94–100% | ζ by 78%, ι by 95% | 82% (290) | 69% (290) | |

N.T. = not tested

Comparable to inhibition of PKCs

Table 2.

Mechanism, efficacy in vitro vs. in cells, and specificity of various inhibitor types

| Inhibitor | Mechanism of Action | Inhibition of PKC | Specificity of PKC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in vitro | In cells | |||

| SMALL-MOLECULE | ||||

| Active-Site | ATP-competitive | ✔ | ✔ | Variable, see Table 1 |

| Non-Active-Site | ||||

| BisIV | Allosteric, uncompetitive with substrate | ✔ | ✔ | At 500nM, inhibited 4.5% of 290 other kinases by ≥50% (as much as it inhibited PKCs) [68] |

| Calphostin C | Competes against DAG/phorbol ester binding to C1 domain | ✔ | ✔ | Not well characterized |

| PS168, PS171 benzimidazole compounds | Allosterically inhibits by binding PIF-pocket | ✔ | ✔ | Selectively inhibits PKCζ over other isozymes and AGC kinases [104] |

| Geldanamycin 17-AAG, Celastrol | Inhibits PKC maturation by inhibiting Hsp90/Cdc37 | × | ✔ (not acute) | Not applicable |

| Torin1 | Inhibits PKC maturation by inhibiting mTORC2 | × | ✔ (not acute) | Not applicable |

| PEPTIDES | ||||

| ZIP and other pseudosubstrate-derived peptides | Highly basic peptide competes with substrate | ✔ | × | None |

| DISCREDITED | ||||

| Rottlerin | Mitochondrial uncoupler | × | × | None |

| Chelerythrine | Induces apoptosis | ✔/× | × | None |

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Newton lab for helpful discussions and critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH GM43154 (ACN) and P01 DK054441 (ACN) and in part by the UCSD Graduate Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology through NIGMS T32 GM007752 (AXW).

Abbreviations

- PKC

protein kinase C

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- PDK-1

phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1

- RACK

receptor for activated C kinase

- MARCKS

myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate

- CKAR

C kinase activity reporter

- PKA

protein kinase A

- AKAR

A kinase activity reporter

- PKB

protein kinase B (aka Akt)

- BKAR

B kinase activity reporter

- PKD

protein kinase D

- DKAR

D kinase activity reporter

- δCKAR

PKCδ-specific CKAR

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- IP3

inositol trisphosphate

- DiC8

dioctanoyl(glycerol)

- OAG

oleoacetylglycerol

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate

- PDBu

phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate

- Bis

bisindolylmaleimide

- AKAP

A-kinase anchoring protein

- PiB

Pin1 inhibitor

- PHLPP

PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase

- RICK

receptor for inactive C kinase

- ZIP

zeta inhibitory peptide

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- CaMK

Ca2+/calmodulin kinase

- KSR1

kinase suppressor of Ras 1

- PP

pyrazolo[3,4-D]pyrimidine

References

- 1.Castagna M, Takai Y, Kaibuchi K, Sano K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y. Direct activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase by tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J Biol Chem. 1982;257(13):7847–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton AC. Diacylglycerol’s affair with protein kinase C turns 25. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(4):175–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newton AC. Protein kinase C: poised to signal. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298(3):E395–402. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00477.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):281–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reyland ME. Protein kinase C isoforms: Multi-functional regulators of cell life and death. Front Biosci. 2009;14:2386–99. doi: 10.2741/3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosse C, Linch M, Kermorgant S, Cameron AJ, Boeckeler K, Parker PJ. PKC and the control of localized signal dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(2):103–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg SF. Structural basis of protein kinase C isoform function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(4):1341–78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newton AC. Protein kinase C: structural and spatial regulation by phosphorylation, cofactors, and macromolecular interactions. Chem Rev. 2001;101(8):2353–64. doi: 10.1021/cr0002801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton AC. Lipid activation of protein kinases. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S266–71. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800064-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giorgione JR, Lin JH, McCammon JA, Newton AC. Increased membrane affinity of the C1 domain of protein kinase Cdelta compensates for the lack of involvement of its C2 domain in membrane recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(3):1660–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510251200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dries DR, Gallegos LL, Newton AC. A single residue in the C1 domain sensitizes novel protein kinase C isoforms to cellular diacylglycerol production. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(2):826–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez AI, Blace N, Crary JF, Serrano PA, Leitges M, Libien JM, Weinstein G, Tcherapanov A, Sacktor TC. Protein kinase M zeta synthesis from a brain mRNA encoding an independent protein kinase C zeta catalytic domain. Implications for the molecular mechanism of memory. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):40305–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang K, Apostolatos AH, Ghansah T, Watson JE, Vickers T, Cooper DR, Epling-Burnette PK, Patel NA. Identification of a novel antiapoptotic human protein kinase C delta isoform, PKCdeltaVIII in NT2 cells. Biochemistry. 2008;47(2):787–97. doi: 10.1021/bi7019782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueyama T, Ren Y, Ohmori S, Sakai K, Tamaki N, Saito N. cDNA cloning of an alternative splicing variant of protein kinase C delta (PKC deltaIII), a new truncated form of PKCdelta, in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269(2):557–63. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JD, Seo KW, Lee EA, Quang NN, Cho HR, Kwon B. A novel mouse PKCdelta splice variant, PKCdeltaIX, inhibits etoposide-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;410(2):177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neill AK, Gallegos LL, Justilien V, Garcia EL, Leitges M, Fields AP, Hall RA, Newton AC. Protein kinase Calpha promotes cell migration through a PDZ-dependent interaction with its novel substrate discs large homolog 1 (DLG1) J Biol Chem. 2011;286(50):43559–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.294603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng M, Sala C. PDZ domains and the organization of supramolecular complexes. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newton AC. Regulation of the ABC kinases by phosphorylation: protein kinase C as a paradigm. Biochem J. 2003;370(Pt 2):361–71. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gould CM, Newton AC. The life and death of protein kinase C. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9(8):614–25. doi: 10.2174/138945008785132411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallegos LL, Newton AC. Spatiotemporal dynamics of lipid signaling: protein kinase C as a paradigm. IUBMB Life. 2008;60(12):782–9. doi: 10.1002/iub.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roffey J, Rosse C, Linch M, Hibbert A, McDonald NQ, Parker PJ. Protein kinase C intervention: the state of play. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(2):268–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das Evcimen N, King GL. The role of protein kinase C activation and the vascular complications of diabetes. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55(6):498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu-Zhang AX, Schramm CL, Nabavi S, Malinow R, Newton AC. Cellular pharmacology of protein kinase Mzeta (PKMzeta) contrasts with its in vitro profile: implications for PKMzeta as a mediator of memory. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(16):12879–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.357244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen P. Guidelines for the effective use of chemical inhibitors of protein function to understand their roles in cell regulation. Biochem J. 2010;425(1):53–4. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Violin JD, Newton AC. Pathway illuminated: visualizing protein kinase C signaling. IUBMB Life. 2003;55(12):653–60. doi: 10.1080/152165401310001642216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Violin JD, Zhang J, Tsien RY, Newton AC. A genetically encoded fluorescent reporter reveals oscillatory phosphorylation by protein kinase C. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(5):899–909. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ting AY, Kain KH, Klemke RL, Tsien RY. Genetically encoded fluorescent reporters of protein tyrosine kinase activities in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):15003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211564598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Ma Y, Taylor SS, Tsien RY. Genetically encoded reporters of protein kinase A activity reveal impact of substrate tethering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):14997–5002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211566798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunkel MT, Ni Q, Tsien RY, Zhang J, Newton AC. Spatio-temporal dynamics of protein kinase B/Akt signaling revealed by a genetically encoded fluorescent reporter. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(7):5581–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411534200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunkel MT, Toker A, Tsien RY, Newton AC. Calcium-dependent regulation of protein kinase D revealed by a genetically encoded kinase activity reporter. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6733–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608086200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunkel MT, Newton AC. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Kinase Signaling Visualized by Targeted Reporters. Curr Protoc Chem Biol. 2009;1(1):17–18. doi: 10.1002/9780470559277.ch090106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]