Abstract

Background

Computerized provider order entry (CPOE) is the process of entering physician orders directly into an electronic health record. Although CPOE has been shown to improve medication safety and reduce health care costs, these improvements have been demonstrated largely in the inpatient setting; the cost-effectiveness in the ambulatory setting remains uncertain.

Objective

The objective was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of CPOE in reducing medication errors and adverse drug events (ADEs) in the ambulatory setting.

Methods

We created a decision-analytic model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of CPOE in a midsized (400 providers) multidisciplinary medical group over a 5-year time horizon— 2010 to 2014— the time frame during which health systems are implementing CPOE to meet Meaningful Use criteria. We adopted the medical group’s perspective and utilized their costs, changes in efficiency, and actual number of medication errors and ADEs. One-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted. Scenario analyses were explored.

Results

In the base case, CPOE dominated paper prescribing, that is, CPOE cost $18 million less than paper prescribing, and was associated with 1.5 million and 14,500 fewer medication errors and ADEs, respectively, over 5 years. In the scenario that reflected a practice group of five providers, CPOE cost $265,000 less than paper prescribing, was associated with 3875 and 39 fewer medication errors and ADEs, respectively, over 5 years, and was dominant in 80% of the simulations.

Conclusions

Our model suggests that the adoption of CPOE in the ambulatory setting provides excellent value for the investment, and is a cost-effective strategy to improve medication safety over a wide range of practice sizes.

Keywords: adverse drug events, ambulatory care, computerized physician order entry system, cost-benefit analysis (cost-effectiveness), medication errors

Introduction

In 2009, United States Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a seminal piece of legislation focused on health care reform [1]. The act includes the $19 billion Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health provision, which has spurred electronic health record (EHR) adoption [2]. Also promoting EHR adoption are financial incentives from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to providers who demonstrate Meaningful Use [3]. At the top of the list of stage 1 Meaningful Use criteria is implementation of the computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system.

Published systematic reviews suggest that CPOE is associated with a 13% to 99% reduction in medication errors and a 30% to 84% reduction in adverse drug events (ADEs) [4, 5]. In the ambulatory setting, our group found that CPOE, even with limited clinical decision support alerts to guide ordering, is associated with a 55% reduction in errors [6]. Although early problems with drop-down boxes [7], resistance to adoption [8], workflow disruption [9–11], increased workload [9–11], and even increased numbers of errors [12] have been reported, CPOE has gained traction over the past 5 years and is now an integral part of the learning health care system [13, 14]. Current research is addressing alert fatigue using methods of human factors engineering [15, 16]. Workflow has emerged as an area of focus [17]. Work continues to iteratively improve CPOE systems with clinical decision support alerts to further reduce medication errors and improve prescriber adherence to guidelines [18–20].

One of the major barriers to the adoption of CPOE (and EHRs) has long been the large up-front investment. Meaningful Use incentives reduce this cost barrier, thereby promoting increased uptake, with the ultimate goal of improving patient safety. However, few studies have estimated the long-term costs of CPOE relative to its safety benefits. Studies conducted in the ambulatory setting have demonstrated a positive return on investment in an EHR [21, 22], and similar findings have been noted in inpatient settings when evaluating CPOE [23, 24]. One study estimated the cost-effectiveness of an electronic medication ordering system in reducing ADEs in the inpatient setting [25], but we found no such study in ambulatory care. Our objective was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of CPOE versus traditional paper-based prescribing in reducing medication errors and ADEs in the ambulatory care setting of a midsized (400 providers) medical group.

Methods

Setting

The Everett Clinic is the largest independent, physician-owned medical group in Washington state. Based in the North Puget Sound, The Everett Clinic is a multispecialty clinic system comprising more than 400 prescribers, approximately equally distributed between primary care and specialty physicians, with a growing number of mid-level providers. These clinicians provide care for more than 300,000 patients within 60 clinics in 16 locations, and admit to primarily one community hospital in the local market. The Everett Clinic contracts with approximately 18 health plans, each with its own formulary; clinicians order 2.7 million prescriptions annually. In 1995, The Everett Clinic developed a homegrown EHR. The system was Web-based, used point-and-click functionality, and integrated electronic prescribing into an existing EHR that included scheduling, chart notes, and laboratory and imaging reports. Basic CPOE software was designed in 2004 and rolled out from 2004 through 2006, and generated new and refill prescriptions. The drug database was provided by Multum (Cerner, Denver, CO). Clinicians selected medications from pull-down menus or “favorites” lists. Clinical decision support alerts were limited to basic dosing guidance, duplicate therapy checks, and pediatric dosing calculations. Clinic staff could queue prescriptions; prescribers signed and released them. Prescriptions could be electronically transmitted to more than 200 local pharmacies. Prescribing at the point of care demanded a fundamental shift in workflow and required a computer to be installed in each examination room. Our group has previously evaluated the effect of this CPOE implementation on medication errors and ADEs [6], and on prescriber and staff time [26].

The Model

Adding the CPOE module to an existing homegrown EHR provided a unique opportunity to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the CPOE system separate from the EHR. A decision-analytic model was created using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis of The Everett Clinic’s CPOE system. Although we considered modeling both the cost-benefit and the cost-utility of the CPOE system, in this case, we were interested in estimating the cost per medication error or ADE averted; hence, cost-effectiveness analysis was the method of choice. The perspective of the medical group was chosen because the medical group incurs implementation costs and realizes the benefit of improved prescription accuracy and safety. Patients benefit from improved medication safety.

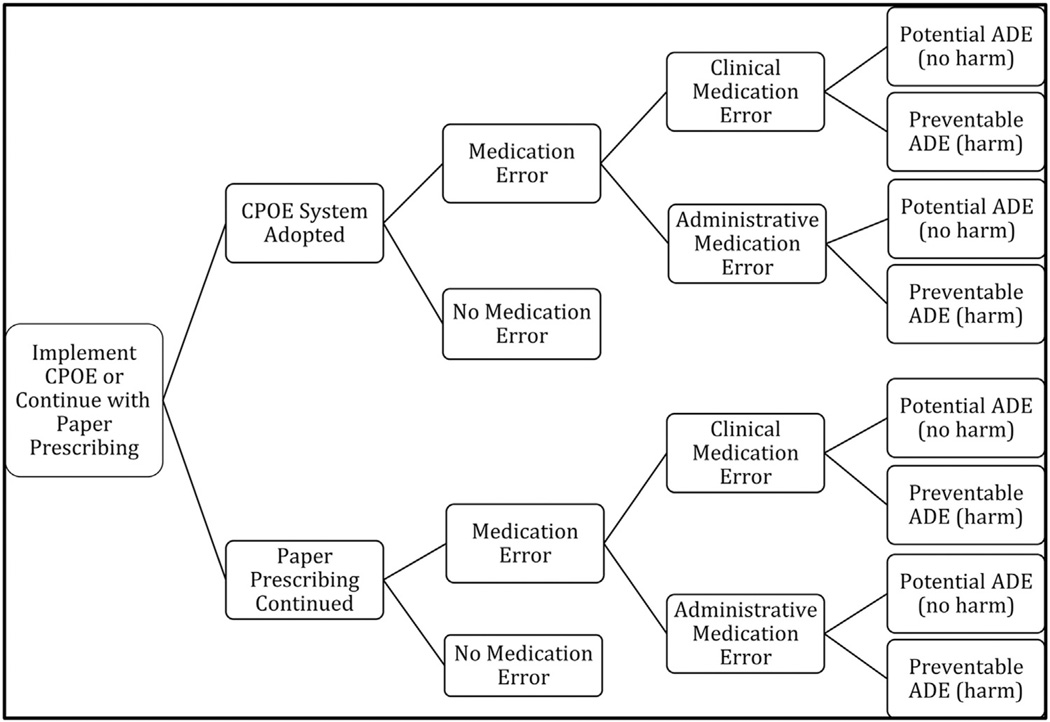

The model compares prescriptions that were hand-written before CPOE implementation (paper-based) with those prescribed after CPOE implementation, and evaluates prescriptions written annually, per provider. The use of either a paper-based or a CPOE system could lead to a clinical (e.g., drug–drug interaction) or administrative (e.g., illegibility) medication error, and each medication error could lead to a potential ADE (no harm) or preventable ADE (harm) (Fig. 1) [6]. The two outcome measures were the number of medication errors avoided and the number of ADEs avoided. We chose a 5-year time horizon (2010–2014) to model the effect of CPOE in accordance with CMS Meaningful Use incentives [3]. These incentives, in the amount of $44,000 over 5 years (2011– 2015), are awarded to each eligible participating provider who meets certain prescribing criteria [3]. We designed our model to reflect a medical group that anticipates meeting these criteria, and therefore, express all year 1 modeling costs in 2010 US dollars. Costs are discounted 3% annually for each of the remaining 4 years of the time horizon.

Fig. 1.

Decision analytic model. ADE, adverse drug event; CPOE, computerized provider order entry.

Base-Case Analysis

The point estimates and respective ranges for all cost and error/ ADE probability inputs are listed in Table 1. The base-case analysis includes the system costs of implementing and maintaining the CPOE system (hardware, software, maintenance, personnel), administrative costs (chart pulls for prescription refills, time spent by staff queuing prescriptions), prescribing costs (time spent by prescribers conducting prescribing tasks), and two types of prescribing incentives (pay-for-performance [P4P] and Meaningful Use). Year over year increases in dollars account for the growth in the number of patients cared for at The Everett Clinic, which resulted in increases in numbers of prescribers and staff hired, number of visits, and number of prescriptions written.

Table 1.

Cost and medication error/ADE inputs: Base-case and scenario analyses.

| Model parameters | Paper system (range) |

CPOE system (range) |

Distribution used in PSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| COSTS* | |||

| CPOE system costs (The Everett Clinic data) | |||

| CPOE hardware, software, and maintenance costs† (thousands) ($) | |||

| Year 1, 2010 | NA | 373 (355–392) | Normal |

| Year 2, 2011 | NA | 675 (642–709) | Normal |

| Year 3, 2012 | NA | 541 (514–568) | Normal |

| Year 4, 2013 | NA | 92 (88–97) | Normal |

| Year 5, 2014 | NA | 92 (88–97) | Normal |

| Personnel costs‡ (CliniTech and The Everett Clinic employees) (thousands) ($) | |||

| Year 1, 2010 | NA | 555 (528–583) | Normal |

| Year 2, 2011 | NA | 625 (493–656) | Normal |

| Year 3, 2012 | NA | 639 (607–671) | Normal |

| Year 4, 2013 | NA | 639 (607–671) | Normal |

| Year 5, 2014 | NA | 639 (607–671) | Normal |

| Indirect costs (%) | NA | 3% of CPOE system and personnel costs |

Beta |

| Administrative costs | |||

| Total The Everett Clinic prescriptions written per year (millions) (The Everett Clinic data) |

2.7 (2.65–2.84) | 2.7 (2.65–2.84) | Normal |

| Annual rate of increase in prescriptions written (%) | 1 (0.1–2) | 1 (0.1–2) | Beta |

| Chart pulls (The Everett Clinic data) | |||

| Charts pulled per day per provider | 10 (5–12) | 5 (3–7)§ | Normal |

| Days worked per provider per year | 224 (202–246) | 224 (202–246) | Normal |

| Cost per chart pull ($) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | Normal |

| Prescription queuing [26] | |||

| RN time per Rx (s) | 83.2 (70.6–96.1) | 76.0 (64.4–87.5) | Normal |

| MA time per Rx (s) | 114.1 (96.8–131.4) | 133.9 (113.8–154.1) | Normal |

| Rx queued by an RN (% of all Rxs) | 40 (32^8) | 40 (32^8) | Beta |

| Rx queued by an MA (% of all Rxs) | 18 (14–21) | 27 (22–32) | Beta |

| Time spent prescribing, per prescriber [26] | |||

| New prescription (s) | 47.16 (39.96–54.00) | 74.88 (63.72–86.40) | Normal |

| Refill prescription(s) | 46.08 (39.24–52.92) | 60.12 (51.12–69.12) | Normal |

| Prescribing costs | |||

| Number of providers (The Everett Clinic data) and compensation [29] | |||

| Primary care providers (PCPs) (n) | 129 (116–142) | 129 (116–142) | Normal |

| Hourly salary ($), PCP | 81 (72–89) | 81 (72–89) | Normal |

| Annual rate of increase in PCPs employed (%) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | Beta |

| Mid-level providers (MLPs) (n) | 25 (23–28) | 25 (23–28) | Normal |

| Hourly salary ($), MLP | 51 (46–56) | 51 (46–56) | Normal |

| Annual rate of increase in MLPs employed (%) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | Beta |

| Specialty providers (n) | 226 (203–249) | 226 (203–249) | Normal |

| Hourly salary ($), specialty provider | 106 (95–142) | 106 (95–142) | Normal |

| Annual rate of increase in specialty providers employed (%) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | Beta |

| Hourly salary ($), RN | 36 (32^0) | 36 (32^0) | Normal |

| Hourly salary ($), MA | 17 (15–18) | 17 (15–18) | Normal |

| Hourly salary ($), OA | 17 (16–20) | 17 (16–20) | Normal |

| FINANCIAL INCENTIVES | |||

| Incentive-eligible prescribers (The Everett Clinic data) (%) | 0 | 72 | Normal |

| HITECH Meaningful Use incentives, per prescriber [3] ($) | |||

| Year 1, 2010 | NA | 0 | Normal |

| Year 2, 2011 | NA | 18,000 | Normal |

| Year 3, 2012 | NA | 12,000 | Normal |

| Year 4, 2013 | NA | 8,000 | Normal |

| Year 5, 2014∥ | NA | 4,000 | Normal |

| Pay-for-performance incentives | |||

| Office visits per year (thousands) (The Everett Clinic data) | 650 (625–675) | 650 (625–675) | Normal |

| Annual rate of increase in visits (%) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | Beta |

| 10-min visits (%) | 5(4–6) | 5(4–6) | Beta |

| 15-min visits (%) | 35 (30^0) | 35 (30^0) | Beta |

| 25-min visits (%) | 40 (35^5) | 40 (35^5) | Beta |

| 40-min visits (%) | 10 (8–12) | 10 (8–12) | Beta |

| CMS reimbursement, per patient per visit [30] ($) | |||

| 10-min visit | 40 (36^4) | 40 (36^4) | Normal |

| 15-min visit | 65 (58–71) | 65 (58–71) | Normal |

| 25-min visit | 98 (88–108) | 98 (88–108) | Normal |

| 40-min visit | 133 (120- 146) | 133 (120–146) | Normal |

| EVENTS [6] | |||

| Medication error and ADE probabilities (as proportion of total prescriptions) | |||

| Probability of medication error | 0.182 | 0.067 | Lognormal |

| Clinical medication error | 0.073 | 0.043 | Lognormal |

| Potential ADE | 0.072 | 0.042 | Lognormal |

| Preventable ADE | 0.001 | 0.001 | Lognormal |

| Administrative medication error | 0.108 | 0.024 | Lognormal |

| Potential ADE | 0.108 | 0.024 | Lognormal |

| Preventable ADE | 0 | 0 | Lognormal |

| SCENARIO 4: SMALL PRACTICE MODEL | |||

| Cost of CPOE implementation (year 1) [35] ($) | NA | 3,921 | Normal |

| Cost of CPOE maintenance (years 2 through 5) [35] ($) | NA | 2,209 | Normal |

| Number of patients per panel [37] | 1,800 | 1,800 | Normal |

ADE, adverse drug event; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; CPOE, computerized provider order entry; HITECH, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health; MA, medical assistant; NA, not applicable; OA, office assistant; PSA, probabilistic sensitivity analysis; RN, registered nurse; Rx, prescriptions; The Everett Clinic data—The Everett Clinic, data from financial accounting records.

All costs are in 2010 US dollars.

Hardware costs in year 1 reflect wireless installation; hardware costs in years 2 and 3 reflect switch to wired installation of computers in most examination rooms; hardware costs in years 4 and 5 reflect installation in remainder of the examination rooms; the expected life of hardware is 5 years. Software costs include the cost of the operating system, drug database, and virus protection; maintenance costs include costs for maintaining secure Internet connections and costs for parts and labor for failed equipment.

Personnel costs reflect software development, software maintenance and updating, testing and training, and ongoing help desk support. Personnel costs are included for the following types of personnel, each working part-time on CPOE implementation: one project manager, two programmers, one network security administrator, one database administrator, and one application support person. The help desk was staffed by one technical person and two clinical pharmacists who specialized in CPOE implementation.

For first year only.

Meaningful Use incentives truncated at year 4 to align with 5-y life of computer hardware.

System Costs

System costs represent those actually incurred by The Everett Clinic for CPOE installation during the first 3 years (2004–2006) and those incurred on an annual, recurring basis from years 1 through 5 (2004–2008). Hardware costs in year 1 reflect wireless installation; hardware costs in years 2 through 5 reflect the switch to wired installation of a computer in most examination rooms. Maintenance costs include the costs of maintaining secure Internet connections and costs of parts and labor for failed equipment. The expected life of the hardware is 5 years. Software costs include the cost of the operating system, drug database, and virus protection. The software was developed and the system was installed and maintained by professionals employed by The Everett Clinic’s health information technology subsidiary, CliniTech. Personnel costs were incurred in each year and reflect software development, maintenance, and updating; testing and training; and ongoing help desk support. Because the CPOE system was implemented incrementally over 2 years, no decrease in productivity was experienced. A 3% indirect overhead rate is added to all system and personnel costs. These reflect actual dollars spent, as recorded by The Everett Clinic’s financial accounting system, and are inflation-adjusted to 2010 using the consumer price index for medical care [27].

Administrative and Prescribing Costs

Administrative costs consist of paper chart pulls, registered nurse and medical assistant time spent queuing prescriptions, and prescriber time spent prescribing. The number of chart pulls included is limited to those estimated to be needed to evaluate prescription refills only and include the time and cost of medical records personnel to retrieve and re-file the chart [28]. In the first year of CPOE, chart pulls were estimated to be reduced by one-half, then dropped to zero for subsequent years, as all paper charts were eliminated at The Everett Clinic. Registered nurse and medical assistant time spent queuing prescriptions, and prescriber time spent prescribing was based on the number of prescriptions filled at The Everett Clinic per year, the number of physicians and staff employed, and the time spent prescribing. Estimates for time spent queuing and prescribing were taken directly from a direct observation time-motion study previously conducted by our group [26]. Prescribing time reflects time spent prescribing before CPOE implementation and after system use reached stability and reflects the same time frame as does system costs. We applied mean compensation, by occupation, supplied by the Bureau of Labor Statistics [29]. All administrative and prescribing cost data are set in 2010.

Incentives

When The Everett Clinic meets prespecified quality benchmarking criteria, the P4P incentives are awarded annually by the health plans with which it contracts. These take the form of a premium paid per ambulatory care visit. For purposes of the cost-effectiveness analysis model, the only incentive we applied was that of adopting a CPOE system. We conservatively estimate that CPOE adoption comprises a small portion of the P4P incentive and estimate it at 3% above Medicare’s rate for primary care office visits [30]. Increased revenue from each patient visit was assumed to start in year 1 (2010). For CMS criteria, we conservatively applied 32% of the total amount of each annual Meaningful Use incentive payment to the model, reasoning that CPOE criteria comprise a significant proportion but not all of the total EHR stage 1 Meaningful Use criteria [3, 31].

Medication Errors and ADEs

We use our previously published data evaluating the effect of a CPOE system on medication errors and ADEs to populate the event probabilities in our model [6]. These probabilities were obtained from a sample size of more than 10,000 prescriptions that were evaluated for medication errors and ADEs. In this sample, approximately 14% of the patients were older than 65 years and 58% were female; more than 70% of the prescriptions were ordered by primary care physicians (including pediatricians), 14% by specialty providers, and less than 10% by urgent care providers. Between 15% and 18% of the prescriptions were written for antibiotics, 19% for controlled substances, 10% for central nervous system agents, 6% for antidepressants, 7% for hormones, and 40% for others [6]. We classify errors as 1 of 17 types (Table 2). We then categorize each of these as clinical or administrative, to distinguish errors for which lack of clinical information could have contributed to an error (e.g., drug–lab monitoring) from those for which clinical information would not play a role (e.g., illegibility), respectively. If a prescription were found to have more than one medication error, the most severe was chosen. Medication errors were linked to ADEs through chart review, and severity was classified using the rating system of the National Coordinating Council on Medication Error Reporting and Prevention [32]. All clinical errors were associated with either potential (levels B–D; no harm) or preventable ADEs (levels E–F; harm); all administrative errors were associated with potential ADEs. Data reflect the number of medication errors and ADEs that occurred before CPOE implementation and after system use reached stability and reflects the same time frame as do system costs [6]. We have no reason to believe that the proportion of prescriptions with errors or ADEs would have changed since that time, so have set these estimates in 2010. As with costs, increases in the number of errors and ADEs, year over year, reflect increases in the number of patients cared for at The Everett Clinic, and therefore increased number of prescriptions. All outcomes are then discounted at 3% per annum from 2011 through 2014.

Table 2.

Types of errors, administrative and clinical [6], and probabilities.

| Types of errors | Proportion of prescriptions with each error type before CPOE implementation (%) |

Proportion of prescriptions with each error type after CPOE implementation (%) |

Distribution used in PSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | |||

| Contraindication for patients ≥65 y | 0.5 | 0.2 | Lognormal |

| Drug allergy | 0.2 | 0 | Lognormal |

| Drug-disease interaction | 0.5 | 0.2 | Lognormal |

| Drug-drug interaction | 0.5 | 0.3 | Lognormal |

| Lack of appropriate laboratory monitoring | 2.0 | 2.1 | Lognormal |

| Therapeutic duplication | 0.3 | 0.3 | Lognormal |

| Wrong directions | 2.4 | 1.6 | Lognormal |

| Wrong dosage form | 0.1 | 0.1 | Lognormal |

| Wrong dose | 0.2 | 0.2 | Lognormal |

| Wrong drug | 0.3 | 0.2 | Lognormal |

| Wrong route | 0 | 0 | Lognormal |

| Wrong strength | 0.3 | 0.1 | Lognormal |

| Total proportion of prescriptions with clinical errors | 7.3 | 5.3 | |

| Administrative | |||

| Illegible writing | 2.0 | 0 | Lognormal |

| Inappropriate abbreviations | 4.8 | 0.4 | Lognormal |

| Missing information | 3.8 | 2.5 | Lognormal |

| Wrong patient | 0.1 | 0 | Lognormal |

| Wrong physician | 0.1 | 0 | Lognormal |

| Total proportion of prescriptions with administrative errors | 10.8 | 2.9 | |

| Total proportion of prescriptions with any type of error | 18.2 | 8.2 | |

CPOE, computerized provider order entry; PSA, probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses on all model parameters. The results of the one-way sensitivity analyses identify inputs with the greatest effect on results. We conducted a probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation methods (10,000 simulation runs) to examine joint uncertainty in model outcomes, applying a distribution suitable to each parameter (Table 2), and calculate the net monetary benefit of each strategy [33]. These results are plotted as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the CPOE strategy over a plausible range of willingness to pay for the CPOE system.

Scenario Analyses

We explore four scenario analyses. Because CPOE implementation at The Everett Clinic reflects an add-on module to a preexisting, homegrown EHR, the incremental costs reflected in our base case are likely lower than those incurred when a CPOE system is initially implemented in conjunction with a vendor-purchased EHR. In the latter situation, the entire system is new, implementation costs higher, and training requirements more intense. Acknowledging this reality, in scenario 1, we double the costs in the base case to better reflect the effect of a more expensive CPOE system. In scenario 2, we assume that The Everett Clinic achieved no reduction in paper chart pulls throughout the 5-year time horizon, to explore the effect of inefficiency from running a paper and electronic system in parallel. In scenario 3, we assume Meaningful Use incentives are not available and explore the effect of lack of this cost offset on implementation costs.

Last, in scenario 4, we decrease the size of the medical group. In the United States, approximately 55% of physician offices are solo practices, 41% are groups between 2 and 10 providers, 3% are groups between 11 and 19 providers, and the remaining 1% are groups of 20 or more physicians [34]. As our base case reflects a medical group that falls into this last category, scenario 4 models a smaller medical group, of 5 providers (varied from1 to 20 providers in the sensitivity analyses). Because of our concern that implementation processes of CPOE systems in a small medical group may be fundamentally different from those experienced by The Everett Clinic, we used system implementation and maintenance costs obtained from the literature and created a “small practice model.” We chose costs for a stand-alone e-prescribing system, often installed in small practices, which is similar in features and functionality to The Everett Clinic’s CPOE system (basic, with little clinical decision support that would be available if fully integrated with a complete EHR, yet with the capability of transmitting prescriptions electronically) [35]. These system costs include hardware, software, personnel, and training, and were $3900 (2010 US dollars) per provider during the implementation year and $2900 (2010 US dollars) per provider per year during each maintenance year [36]. Evidence suggests that there is no decline in productivity during the implementation of an e-prescribing system [35], which was also similar to The Everett Clinic’s experience. We assume all providers are primary care providers and estimate the size of their practice panel using an equation provided by the American Academy of Family Practice [37]. We retained the number of prescriptions written per prescriber per year, and the proportions of prescriptions with medication errors and ADEs used in The Everett Clinic base-case and other scenario analyses, because we found no reason to believe that these patterns would be dependent on practice size. The cost of chart pulls, provider salaries, and incentive payments also remain the same.

Results

Base Case

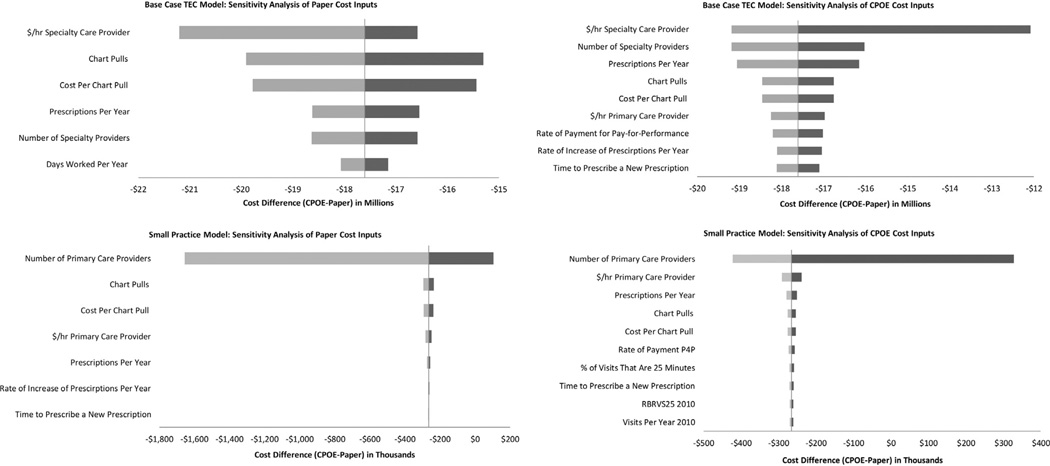

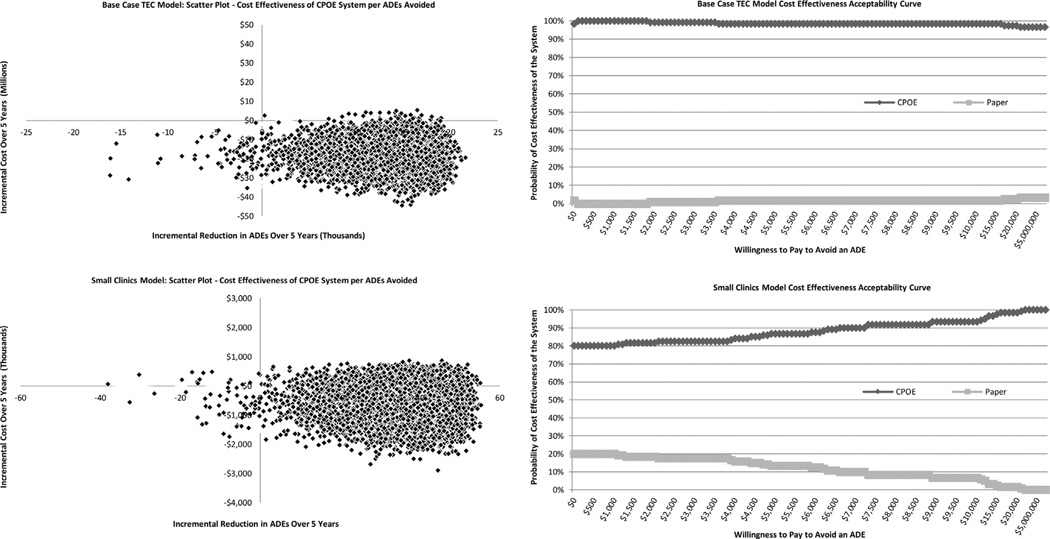

In the base case, the CPOE strategy cost $18 million less than paper-based prescribing and is associated with 1.5 million fewer errors and 14,500 fewer ADEs. Accordingly, CPOE is the dominant strategy. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis confirms that CPOE is the dominant strategy in 99.6% and 98.9% of the Monte Carlo simulations for medication errors and ADEs, respectively (Table 3). One-way sensitivity analyses reveal that the largest drivers of uncertainty in the models are the salary and number of specialty care providers, the number and cost of chart pulls, and the number of prescriptions ordered per year (Fig. 2). The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve illustrates the probability that the CPOE system is cost-effective at various levels of willingness to pay per ADE avoided. For the base case, the probability that the CPOE system is cost-effective is more than 98% until willingness to pay reaches approximately $16,000, when it drops slightly, remaining steady at more than 97% for the remainder of the levels (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Results—Base case and scenarios 1 through 4.

| Result | Paper system (range*) |

CPOE system (range*) |

Difference (range*) |

CPOE dominated† (less costly and more effective) (%) |

CPOE more costly and more effective (%)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Everett Clinic base case | |||||

| Cost (millions) ($)‡ | 43 (20–69) | 25 (13–38) | −18 (−44 to 5) | ||

| Errors (millions) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | −1.5 (−1.8 to −0.7) | 99.6 | 0.4 |

| ADEs (thousands) | 21.8 (19.7–24.8) | 7.3 (1.6–41) | −14.5 (−21.2 to 18.9) | 98.9 | 0.4 |

| The Everett Clinic scenario 1: Base case with CPOE costs doubled | |||||

| Cost (millions) ($)‡ | 43 (22–67) | 29 (18-) | −13 (−38 to 13) | ||

| Errors (millions) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | −1.5 (−1.8 to −0.7) | 97.6 | 2.4 |

| ADEs (thousands) | 21.8 (19.7–24.8) | 7.3 (1.6–41) | −14.5 (−21.2 to 18.9) | 96.9 | 2.4 |

| The Everett Clinic scenario 2: No reduction in chart pulls | |||||

| Cost (millions) ($)‡ | 42 (21–70) | 44 (19–77) | 1.6 (−36 to 47) | ||

| Errors (millions) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | −1.5 (−1.8 to −0.8) | 50.5 | 49.5 |

| ADEs (thousands) | 21.8 (19.9–24.5) | 7.3 (1.4–41) | −14.5 (−21.4 to 15.6) | 50.1 | 49.1 |

| ICER = $110/ADE avoided | |||||

| The Everett Clinic scenario 3: Exclusion of Meaningful Use incentives | |||||

| Cost (millions) ($)‡ | 42 (22–67) | 29 (18–41) | −14 (−41 to 10) | ||

| Errors (millions) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | −1.5 (−1.8 to −0.7) | 98.3 | 1.7 |

| ADEs (thousands) | 21.8 (19.7–24.8) | 7.3 (1.6–41) | −14.5 (−21.2 to 18.9) | 97.6 | 1.7 |

| Scenario 4: Small practice model (five providers) | |||||

| Cost (thousands) ($)‡ | 478 (65–2,819) | 213 (48–1,029) | −265 (−2,510 to 826) | ||

| Errors (thousands) | 6,099 (5,552–7,003) | 2,224 (1,468–3,644) | −3,875 (−4,946 to −2,008) | 80.4 | 19.6 |

| ADEs (hundreds) | 58 (53–67) | 19 (4–137) | −39 (−55 to 38) | 80.0 | 19.5 |

ADE, adverse drug event; CPOE, computerized provider order entry; ICER, incremental cost- effectiveness ratio.

Range for 10,000 Monte-Carlo simulations,

Percent of Monte-Carlo simulations.

In 2010 US dollars.

Fig. 2.

One-way sensitivity analyses—The Everett Clinic base case and small practice model. Base-case costs are in millions (2010 US dollars). Small practice model costs are in thousands (2010 US dollars). CPOE, computerized provider order entry; RBRVS25, Resource-based Relative Value Scale cost for a 25-minute clinic visit; P4P, pay for performance; TEC, The Everett Clinic.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plots and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves—The Everett Clinic base case and small practice model. ADE, adverse drug event; CPOE, computerized provider order entry; TEC, The Everett Clinic.

Scenario 1

Doubling the costs of the base case, CPOE cost $13 million less than paper-based prescribing and is dominant in 97% of the simulations (Table 3). The most influential cost drivers in this scenario are the same as those in the base case (see Appendix 1 in Supplemental Materials found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.009). The probability of the CPOE system being cost-effective is stable at 99% for almost all levels of willingness to pay (see Appendix 2 in Supplemental Materials found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.009).

Scenario 2

When we model no reduction in chart pulls, CPOE remains the dominant strategy for medication errors, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $110 per ADE averted. For both medication errors and ADEs averted, CPOE remains dominant in 50% of the simulations (Table 3). Again, in the one-way sensitivity analyses, the same parameters drive the largest changes in the model (see Appendix 1 in Supplemental Materials found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.009). The probability that the CPOE system is cost-effective is just below 50% when willingness to pay is less than $200, but rises rapidly to more than 99% thereafter (see Appendix 2 in Supplemental Materials found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.009).

Scenario 3

Eliminating Meaningful Use incentives did not have an appreciable effect over the base case, saving $14 million to reduce errors by 1.5 million and ADEs by 14,500 over 5 years. CPOE is dominant in 98% to 99% of the simulations (Table 3). The cost drivers in the one-way sensitivity analysis remained the same, and the probability of the CPOE system being cost-effective is stable at 100% at all levels of willingness to pay (see Appendices 1 and 2 in Supplemental Materials found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.009).

Scenario 4

Dominance of the CPOE system is maintained when modeling medical groups with small numbers of providers. With a practice comprising five providers, CPOE saves $265,000 and results in 3,875 fewer medication errors and 39 fewer ADEs, respectively, over 5 years. CPOE is dominant in 80% of the simulations (Table 3). In this scenario, the one-way sensitivity analysis highlights that the number of primary care providers is an exceptionally large driver of costs; far less so is their salary, the number of prescriptions per year, and, again, the number of chart pulls (Fig. 2). This is logical because in this model, both the implementation costs and the number of patients and prescriptions are based on the number of prescribers. In the other scenarios, the number of patients and prescriptions were drawn from The Everett Clinic’s actual experience. The probability that the CPOE is cost-effective is 80% when the willingness to pay per ADE avoided is $0 and rises slowly to more than 95% at approximately $10,000 (Fig. 3).

Constructing a model that reflects small practice sizes provided us an opportunity to compare parameters used in The Everett Clinic model with those used in the small practice model. Specifically, when we compared the cost of the CPOE system per prescriber and the size of the practice panel at The Everett Clinic (calculated from aggregate numbers from The Everett Clinic’s financial management system) with these same parameters used in the small practice model (obtained from the literature on a perprescriber basis), they were quite similar (Table 4). These findings support the validity and generalizability of The Everett Clinic model. Similarly, the prescription volume per patient per year for The Everett Clinic model was calculated from aggregate Everett Clinic data (10 prescriptions per year), and then used in the small practice model. Comparing this value with the same from the literature, we found that the number of prescriptions filled per capita per year in Washington state is 11 and in the United States is 12 [38]. This further validates and supports the generalizability of The Everett Clinic model (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of parameter inputs in The Everett Clinic model and the small practice model.

| Parameter | The Everett Clinic model |

The small practice model (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of CPOE implementation (year 1) ($) | 2443 | 3921 [36] |

| Cost of CPOE maintenance | Year 2: 3301* | 2209 [33] |

| (years 2 through 5) ($) | Year 3: 2890* | |

| Year 4: 1705 | ||

| Year 5: 1644 | ||

| Number of patients per panel | 1900 | 1800 [37] |

| Number of prescriptions per patient per year† | 10 | 10 [The Everett Clinic Model] |

The Everett Clinic costs are larger in years 2 and 3 due to the timing of installation of computers in examination rooms.

Mean number of prescriptions per capita per year in Washington state = 11; mean number of prescriptions per capita per year in the United States = 12.

Discussion

In the base case, the adoption of CPOE and cessation of paper prescribing resulted in lower costs and improved medication safety from the medical group perspective. Neither doubling the costs nor elimination of Meaningful Use incentives significantly altered the results. In scenario 2, wherein we modeled no chart pull reduction over 5 years, the proportion of simulations wherein CPOE was the dominant strategy was cut almost in half. The results of our modeling exercise suggest that the dominance of the CPOE strategy is closely tied to a rapid reduction in chart pulls and, by extension, to the elimination of paper charts. The commitment to elimination of paper charts, on the part of a medical group, is an ambitious undertaking and indicates a full commitment to the electronic storage of data [28].

Our results are strengthened by the conservative nature of our assumptions that were in favor of paper prescribing, and supported by our model design. That is, first, we considered chart pulls solely for refill requests, excluding those pulled for new prescriptions, for addressing medication errors, and for other clinical reasons. Including these costs would have increased the costs of the paper strategy. Second, prescribing time using CPOE was reflective of time spent prescribing in the examination room, which takes longer [26]. Third, at the time of data collection, the CPOE system implemented by The Everett Clinic included only basic clinical decision support functionality. Had more sophisticated functionality been available, additional medication errors may have been identified [6]. For these reasons, our model may have underestimated the benefit of CPOE. The application of CPOE may result in more dramatic cost savings and improved safety for other medical groups if the baseline number of paper chart pulls is higher using the paper strategy, computers are not installed in examination rooms, or more sophisticated clinical decision support alerts are part of the CPOE system [23–25]. However, groups adopting CPOE but unable to fully transition away from pulling charts may not realize a cost saving as great as that seen at The Everett Clinic. That eliminating the Meaningful Use incentives did not change the results should not deter health systems from implementing CPOE systems because the finding that CPOE implementation was less expensive and resulted in improved medication safety, when compared with paper-based prescribing, was almost universal in our models.

Modeling the cost-effectiveness of using an e-prescribing system in small medical groups (small practice model) was a useful exercise, and it further confirmed that implementing such a system, even in a small practice (<20 providers), is of high value— saving costs while improving medication safety. This should encourage small provider groups that have not yet done so to consider adoption. That approximately 95% of the medical groups in the United States are of this small size suggests that national policies to spur adoption reflect good value for money. That this exercise also enabled us to validate The Everett Clinic model suggests that the findings of this model may be generalizable to other midsized medical groups as well. A recently published report suggests that the largest medical group in the United States is the Kaiser Permanente Medical Group (Santa Clara, CA), with 7842 physicians; the 2nd largest, the Cleveland Clinic, with 1472 physicians; and the 50th largest, Health Partners (St. Paul, MN), with 398 physicians [34]. With 355 physicians (and 25 mid-level providers), The Everett Clinic does not rank in the top 50, but it is still the largest independent medical group in the state of Washington. As such, we feel that the results of our base case may be generalizable to medical groups of similar size but not necessarily larger, because it is likely that the largest medical groups are structurally and operationally different from The Everett Clinic.

Approximately 4.5 million ADE-related ambulatory visits occur annually in the United States, with most of these being in the outpatient offices of primary care physicians [39]. The cost of treating an ADE in the ambulatory setting is approximately $771 (inflated to 2010 US dollars) [40]. A recent estimate of the cost of treating a preventable medication-related hospital admission was €5641 (~US $7786) [41], with average production loss costs per admission of €1712 (~US $2363) for a person younger than 65 years. This sums to €6009 (~US $8294) per admission. With more than 95% probability that a CPOE system will be cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of approximately $10,000 to avoid an ADE, the evidence is robust that the implementation of a CPOE system provides good value for money and improves medication safety.

Our study is limited by the fact that the basic CPOE system implemented by The Everett Clinic was homegrown, and costs were undoubtedly lower than those of medical groups implementing a complete, vendor-purchased EHR today. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of an EHR, however, was not our question of interest, so we did not take into account the effect of changes in costs of dictation, transcription, or accounting, billing or charge capture; space for medical records; or other EHR elements. These limitations are balanced by two key strengths. First, we based our medication error and ADE probabilities, and time estimates, on data collected at The Everett Clinic during the time frame of CPOE implementation. Second, our model inputs reflect national averages for implementation costs, physician panel size, and prescriptions ordered per capita per year.

We believe that this is the first study to estimate the cost-effectiveness of CPOE in the ambulatory setting, separate from an EHR. Our findings suggest that provider groups adopting CPOE and eliminating paper prescribing have the potential to rapidly improve medication safety while reducing costs to the health care system.

For groups unable to implement a full EHR all at once, CPOE— or a basic e-prescribing system—can be an important first step, with demonstrated patient safety and cost-saving benefits. Our findings support initiatives of the Institute of Medicine [42] and the CMS [3] to encourage the adoption of CPOE and electronic prescribing because, at our site, CPOE alone resulted in increased medication safety and resulted in cost savings to the system.

Conclusions

Adoption of CPOE in the ambulatory setting of midsize group practices provides excellent value for the investment and is a cost-effective strategy to improve medication safety. These same results may be applied to practices with fewer providers that implement a basic e-prescribing system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues at The Everett Clinic for the provision of data contained in financial records of CPOE implementation, specifically Nathan Lawless, Jennifer Wilson-Norton, and Melani Vance. We also thank the two reviewers whose comments greatly helped to strengthen the article.

Source of financial support: The authors were supported in their work by the following grants: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. 5K08 HS014739; PI: Devine); a training grant from Allergan, Inc. (Hepp); and the National Institute on Aging (grant no. T32 AG027677; Roth; PI: LaCroix). The sponsors played no role in study design, execution, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials accompanying this article can be found in the online version as a hyperlink at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.009 or, if a hard copy of article, at www.valueinhealthjournal.com/issues (select volume, issue, and article).

REFERENCES

- 1.American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Public Law III-5. [Accessed January 18, 2014];111th Congress, February 17, 2009, H.R.1. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ5/pdf/PLAW-111publ5.pdf.

- 2.Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1477–1479. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0901592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 18, 2014];Medicare and Medicaid programs; Regulations and guidance; EHR incentive programs. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html.

- 4.Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Machan C, Siebert U. The effect of electronic prescribing on medication errors and adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:585–600. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shamliyan TA, Duval S, Du J, et al. Just what the doctor ordered: review of the evidence of the impact of computerized physician order entry system on medication errors. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:32–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devine EB, Hansen RN, Wilson-Norton JL, et al. The impact of computerized provider order entry on medication errors in a multispecialty group practice. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:78–84. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner M, Gress T, Thiemann DR, et al. Contrasting views of physicians and nurses about an inpatient computer-based provider order-entry system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6:234–244. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1999.0060234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poon EG, Blumenthal D, Jaggi T, et al. Overcoming barriers to adopting and implementing computerized physician order entry systems in US hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:184–190. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, et al. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;76(Suppl. 1):S21–S27. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra RH, et al. Categorizing the unintended consequences of computerized provider order entry. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(Suppl. 1):S21–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra R, et al. The unintended consequences of computerized provider order entry: findings from a mixed methods exploration. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(Suppl. 1):S69–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koppel R, Metlay J, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;239:1197–1230. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson K. Computerized provider-order entry: challenges, achievements, and opportunities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:730–731. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen LA, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, editors. IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. [Accessed January 18, 2014]. The Learning Healthcare System. Workshop Summary. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11903.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott GP, Shah P, Wyatt JC, et al. Making electronic prescribing alerts more effective: scenario-based experimental study in junior doctors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:789–98. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riedmann D, Jung M, Jackl WO, et al. How to improve the delivery of medication alerts within computerized physician order entry systems: an international Delphi study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:760–766. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baysari MT, Westbrook JI, Richardson KL, et al. The influence of computerized decision support on prescribing during ward-rounds: are the decision-makers targeted? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:754–759. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanji KC, Rothschild JF, Salzberg C, et al. Errors associated with outpatient computerized prescribing systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:767–773. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wetterneck TB, Walker JM, Blosky MA, et al. Factors contributing to an increase in duplicate medication order errors after CPOE implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:774–782. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austrian JS, Adelman JS, Reissman SH, et al. The impact of the heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) computerized alert on provider behaviors and patient outcomes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:783–788. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SJ, Middleton B, Prosser LA, et al. A cost-benefit analysis of electronic medical records in primary care. Am J Med. 2003;114:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grieger DL, Cohen SH, Krusch DA. A pilot study to document the return on investment for implementing an ambulatory electronic health record at an academic medical center. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weingart SN, Simchowitz B, Padolsky H, et al. An empirical model to estimate the potential impact of medication safety alerts on patient safety, health care utilization, and cost in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1465–1473. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zlabek JA, Wickus JW, Mathiason MA. Early cost and safety benefits of an inpatient electronic health record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:169–172. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.007229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu RC, Laporte A, Ungar WJ. Cost-effectiveness of an electronic medication ordering and administration system in reducing adverse drug events. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:440–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devine EB, Hollingworth W, Hansen RN, et al. Electronic prescribing at the point of care: a time-motion study in the primary care setting. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:152–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Consumer price index for medical care. [Accessed January 18, 2014]; Available from: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

- 28.Maxwell JM. Paperless office: a must, a maybe, or a mistake? [Accessed January 18, 2014];American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Available from: http://www.aaos.org/news/bulletin/sep07/managing7.asp.

- 29.Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed January 18, 2014];Occupational employment statistics. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/oes/

- 30.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 18, 2014];Physician fee schedule. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/index.html.

- 31.Marcotte L, Seidman J, Trudel K, et al. Achieving meaningful use of health information technology: a guide for physicians to the EHR incentive programs. Arch Intern Med. 2012;192:731–736. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. [Accessed January 18, 2014];National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. Available from: http://www.nccmerp.org/

- 33.Briggs AH. Handling uncertainty in cost-effectiveness models. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17:479–500. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SK&A. [Accessed January 18, 2014];SK&A’s 50 Largest Medical Groups. 2013 Available from: http://www.skainfo.com/health_care_market_reports/largest_medical_groups.pdf.

- 35.Bell DS, Strauss SG, Belson D, et al. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0102-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [Accessed January 18, 2014]. Toolset for E-Prescribing Implementation in Physician Offices (Prepared by RAND Corporation under Contract No. HHSA 290-2006-00017, TO #4) Available from: http://healthit.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/docs/page/ToolsetEPrescribingImplementationFINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medicare Program: proposed standards for e-prescribing under Medicare Part D. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 18, 2014] ];42 CRF Part 423. Fed Reg. 2007 72(221) Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Regulations-and-Policies/QuarterlyProviderUpdates/downloads/cms0016p.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray M, Davies M, Boushon B. Panel size: how many patients can one doctor manage? [Accessed January 18, 2014];Fam Pract Manag. 2007 :44–51. Available from: http://www.aafp.org/fpm/2007/0400/p44.pdf. [PubMed]

- 38.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed January 18, 2014];Retail prescriptions drugs filled at pharmacies (annual per capita) Available from: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/retail-rx-drugs-per-capita/#notes.

- 39.Sarkar U, Lopez A, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Adverse drug events in US adult ambulatory medical care. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1517–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Field TS, Gilman BH, Subramanian S, et al. The costs associated with adverse drug events among older adults in the ambulatory setting. Med Care. 2005;43:1171–1176. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000185690.10336.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.XE currency converter. [Accessed January 18, 2014]; Available from: http://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/convert/?Amount=6009&From=EUR&To=USD.

- 42.Cosgrove D, Fisher M, Gabow P, et al. A CEO checklist for high value health care. [Accessed January 18, 2014];2012 Available from: http://www.iom.edu/Home/Global/Perspectives/2012/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2012/Discussion-Papers/CEOHighValueChecklist.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.