Abstract

Objectives

Assess pediatric providers’ ability to identify visible plaque on children's teeth.

Methods

Pediatric providers (residents, nurse practitioners, and attendings) conducting well-child care on 15-month to 5-year-olds in an academic practice examined children's maxillary incisors for visible plaque (recorded yes/no). A dental hygienist then examined the children and recorded the degree of visible plaque present.

Results

The children's mean age was 34 months (±15 months), and 50% had visible plaque. Providers (n = 28) identified visible plaque on 39% of children (n = 118), with 55% sensitivity and 80% specificity, and agreement with hygienist measured as a κ score was 0.34. Subgroup analyses (based on provider training level, exam experience, child age, and plaque scores) did not appreciably improve sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, or κ scores.

Conclusions

Visible plaque exams performed during well-child care may not be accurate. To comply with caries-risk assessment guidelines, providers require further education in oral exams.

Keywords: caries, child, dental hygienist, oral health, plaque, primary care, risk factors, toothbrushing

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) is the most common chronic disease of childhood, yet it is preventable. ECC can cause pain, impaired speech development, facial cellulitis, and dental abscesses. Although children of all income levels and backgrounds are at risk, nonwhite and low-income-group children are disproportionately affected.1-4

Pediatric primary care providers (PCPs), who typically see young children more frequently than dentists, have an increasingly important role to play in addressing ECC.5 Therefore, policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry recommend that PCPs perform oral health assessments on their young patients during routine well-child care.5-7 As PCPs devote more time during well-child visits to oral health, it is important that the guidelines for oral health screening are supported by evidence of their utility.

The Oral Health Risk Assessment Tool developed by the AAP includes clinical findings indicative of caries risk, such as visible plaque accumulation, white spots, obvious decay, restorations, and gingivitis.8 These findings reflect a progression to caries development in which plaque accumulation is the earliest visible sign of risk. Therefore, if a clinician is able to identify visible plaque on a child's teeth, counseling can be aimed at improving oral hygiene practices to decrease the risk of that child developing ECC. To date, this has not been shown. In this study, we assess the baseline ability of pediatric PCPs to detect visible plaque on young children's teeth because this finding can be a valuable component of the well-child oral exam and subsequent counseling.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was designed to test agreement between several pediatric PCPs and 1 dental hygienist in the identification of visible plaque on the teeth of young children presenting for well-child care. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participating PCPs and children's parents. The study took place at an academic teaching practice that served 6110 unique patients during the fiscal year in which this study took place, about 75% of whom were Medicaid insured.

Participants

A registered dental hygienist served as the gold standard against whose exams PCP visible plaque exams were compared. There was only 1 hygienist for this study, and so interexaminer reliability was not tested. However, inherent in dental hygienist training and practice is the evaluation of oral health status with oral hygiene indices, such as the Simplified-Oral Health Index (OHI-S) used in this study. Therefore, we assumed that the hygienist had expertise in identifying visible plaque, and she was directly involved in selecting the OHI-S as an appropriate study measure.

Participating PCPs included attending pediatricians, pediatric nurse practitioners, and pediatric residents who provided well-child care in the clinic. Each PCP maintained a specific day or days of the week in which he or she saw patients for well-child care. Therefore, they were enrolled if they provided care on the days of the week that the dental hygienist was available to serve as the gold standard for visible plaque exams. A total of 28 PCPs were enrolled, and each saw a varying number of children based on a convenience sample of patients available to participate.

PCP enrollment occurred individually or in small groups to accommodate individual schedules. During enrollment, PCPs were given an approximately 5-minute review of ECC and the role of plaque in caries development and shown pictures of visible plaque on tooth surfaces. The review was consistent with information provided by the AAP-endorsed Smiles for Life National Oral Health Curriculum.9 The review was not intended to be an intervention in PCP knowledge and was, therefore, limited to only include information that PCPs needed to understand the purpose of the study and the role of plaque in the development of ECC.

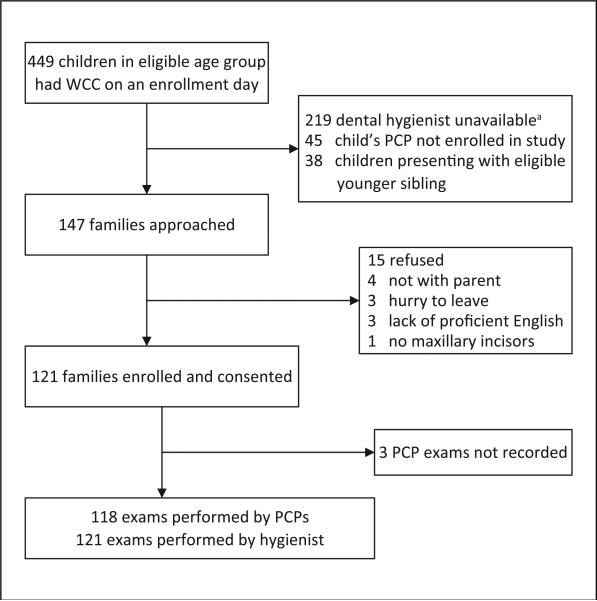

Participating families included healthy children 15 months through 5 years old who were presenting to the clinic for routine well-child care in the company of a parent who was at least 18 years old. We chose a lower limit of 15 months for children because by this age most children have their central maxillary incisors. We chose an upper limit of 5 years, so as to be consistent with the definition of ECC as applying to children through this age. This variation in age was accounted for in analysis. Parents consented for themselves and their child in the exam room prior to their well-child visit with the PCP. Children were excluded if they did not possess at least 1 maxillary incisor, if they were in the company of an eligible younger sibling, or if their parent did not have adequate English proficiency to complete the informed consent form (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of screening protocol and enrollment. Abbreviations: WCC, well-child care; PCP, primary care provider. a The dental hygienist was often unavailable because she was occupied examining a different child.

Visible Plaque Exam

During routine well-child visits with enrolled families, participating PCPs examined the labial surface of the child's 2 central maxillary incisors. These teeth were chosen because they were likely to be erupted in all children enrolled and because caries in these teeth has been associated with greater caries incidence in posterior teeth.10 The PCP then recorded whether or not visible plaque was observed on at least 1 of the maxillary incisors by checking “yes” or “no” on a study card. After the well-child visit, the study card was returned to the hygienist in a sealed envelope. In 3 cases, the provider returned the study card without filling it out.

The dental hygienist entered the exam room when the well-child visit with the PCP was concluded. The hygienist then performed an exam of the child's maxillary incisors and separately recorded findings for each tooth according to the OHI-S scoring system. The OHI-S rates the amount of visible plaque on a tooth's surface on a scale of 0 (no plaque visible) to 3 (nearly entire tooth with visible plaque).11 The highest OHI-S between the 2 teeth was used in analysis and was discordant in only 1 child. The hygienist concluded the visit with standardized oral health counseling and oral hygiene instruction. The prevalence of visible plaque was calculated based on the dental hygienist's exams. A child was considered to have visible plaque present if the hygienist recorded an OHI-S score >0 for either maxillary incisor.

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted to determine if parent or child demographic characteristics contributed to plaque prevalence because factors such as minority race and low income are associated with higher incidence of ECC.2,3 The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), percentage agreement, and κ statistic were calculated for PCP visible plaque exams using the hygienist's exam findings as the gold standard in analysis. Analyses were also conducted to determine if PCP accuracy or exam agreement with the hygienist improved by restricting data to those characteristics we hypothesized would support accurate identification. Specifically, analyses were performed to test the accuracy and agreement of PCP exams that were conducted: (1) on children with high plaque scores (OHI-S ≥2); (2) by more experienced PCPs (nurse practitioners or attendings); (3) on more cooperative children (≥3 years); and (4) by PCPs who had more practice with the visible plaque exam (had examined ≥8 different children). Analyses were run using Stata 11.1 statistical software.12

Results

Participant Characteristics

The 28 enrolled PCPs examined a total of 121 children. Attendings and nurse practitioners represented the majority of enrolled providers and conducted the majority of plaque exams (Table 1). The mean age of children examined was 34 months (standard deviation of 15 months). Most children were identified by their parent as Black or African American only and had Medicaid insurance. The majority of parents enrolled were mothers, had no education beyond high school or a GED, and reported a household income of <$20 000. Male gender and African American race increased the odds of being a child with visible plaque in this sample (Table 2).

Table 1.

PCP Enrollment and Number of Exams Performed.

| Total PCPs Enrolled, n = 28 | Total Exams Performed, n = 118 | |

|---|---|---|

| Residents (PGY 1-3) | 12 (43%) | 28 (24%) |

| Nurse practitioners | 3 (11%) | 27 (23%) |

| Attendings | 13 (46%) | 63 (53%) |

Abbreviations: PCP, primary care provider; PGY, postgraduate year.

Table 2.

Child and Parent Demographic Characteristics and Odds of Child Having Visible Plaque.

| Total (%; n = 121)a | Visible Plaque (%; n = 61)b | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age, months | |||

| <3 Years old | 71 (59%) | 38 (62%) | 1.44 (0.70-2.98) |

| 3 Through 5 years old | 52 (43%) | 23 (38%) | (Reference is age ≥3 years) |

| Child gender | |||

| Male | 62 (51%) | 41 (67%) | 3.80 (1.79-8.08) |

| Female | 59 (49%) | 20 (33%) | (Reference is female) |

| Child ethnicity, Hispanic or Latino | 12 (10%) | 6 (10%) | |

| Child race | |||

| Black or African American | 80 (65%) | 46 (77%) | 2.51 (1.16-5.44) |

| White or Caucasian | 14 (11%) | 6 (10%) | (Reference is non–African American race) |

| Multiracial | 12 (10%) | 3 (5%) | |

| Other | 17 (14%) | 5 (8%) | |

| Child with Medicaid | 111 (95%) | 54 (89%) | |

| Parent gender, female | 109 (90%) | 56 (92%) | |

| Parent highest education | |||

| <High school or GED | 19 (16%) | 7 (12%) | 1.22 (0.94-1.59) |

| High school or GED | 44 (36%) | 23 (38%) | (Reference is education >high school or GED) |

| Some college or associate's degree | 40 (33%) | 19 (32%) | |

| ≥College degree | 18 (15%) | 11 (18%) | |

| Household income | |||

| <$5000 | 30 (25%) | 15 (25%) | 1.21 (0.54-2.67) |

| $5000-$9999 | 13 (11%) | 6 (10%) | (Reference is income ≥$30 000 or do not know) |

| $10 000-$19 999 | 29 (24%) | 16 (27%) | |

| $20 000-$29 999 | 15 (12%) | 8 (13%) | |

| ≥$30 000 | 18 (15%) | 6 (10%) | |

| Do not know | 16 (13%) | 9 (15%) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Missing data resulted in slightly different n for the following demographic calculations: ethnicity n = 120; Medicaid n = 117.

Missing data resulted in total n = 60 for visible plaque prevalence calculations categories of race, education, and income.

Accuracy of PCP Exams

The prevalence of visible plaque in the study population based on dental hygienist exams was 50%. PCPs identified visible plaque on 39% of children. Overall, PCP exam sensitivity was low, but specificity was high enough to rule in most cases of visible plaque. PCPs had a higher sensitivity and NPV when analyses were restricted to children with high plaque scores. However, these calculations were based on a prevalence of children with high plaque scores of only 25%, which lessened the utility of the NPV. For all other group analyses, the confidence intervals overlapped for sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV, indicating that restriction on PCP provider level, child age, and PCP experience with exam did not improve the PCP accuracy in identifying visible plaque on children's teeth (Table 3).

Table 3.

Accuracy and Agreement of Gold Standarda Exams and Primary Care Provider Exams.

| Comparison Measure | Visible Plaque Present |

Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Specificity (95% CI) |

PPV (95% CI) |

NPV (95% CI) |

Percentage Agreement |

κ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All exams, n = 121 | 61 (50%) | 55% (42-68) | 80% (67-89) | 75% (60-87) | 61% (49-73) | 67% | 0.34 (0.18-0.51) |

| High plaque scores,b,c n = 30 | — | 69% (49-85) | 71% (61-81) | 46% (30-61) | 87% (77-94) | 71% | 0.35 (0.03-0.46) |

| NPs or attending, n = 90 | 49 (54%) | 48% (33-63) | 80% (64-91) | 74% (55-88) | 55% (42-69) | 62% | 0.26 (0.08-0.45) |

| Children ≥3 years, n = 51 | 23 (45%) | 55% (32-76) | 79% (59-92) | 67% (41-87) | 69% (50-84) | 68% | 0.34 (0.08-0.60) |

| PCP performed ≥8 exams, n = 86 | 46 (54%) | 54% (39-69) | 74% (57-87) | 71% (54-85) | 57% (42-71) | 63% | 0.27 (0.08-0.47) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; NP, nurse practitioner; PCP, primary care provider; OHI-S, Simplified-Oral Health Index.

Dental hygienist.

OHI-S ≥2.

25% of children had a high plaque score.

Agreement With Hygienist

κ Scores were obtained to control for the probability of chance agreement between the dental hygienist's visible plaque exams and those of the PCPs. All PCPs were treated as one rater in analysis. This yielded a κ score of 0.34, suggesting fair agreement between the PCP and hygienist exams that was not a result of chance, according to Landis and Koch guidelines.13 After submission, I was advised this sentence should be omitted since it is a post-hoc analysis and therefore directly correlated with the p-value, and doesn't add anything to the results. In addition, κ scores were obtained for specific groups, restricted by PCP and child characteristics, similar to the accuracy analysis. The highest κ score was 0.35, obtained for exams with high plaque scores (Table 3).

Discussion

Under current pediatric training requirements, the visible plaque exam recommended by the AAP has limited utility in light of our findings. κ Scores show that PCP exams for visible plaque have some correlation to the caries risk factor, especially for children with higher degrees of plaque accumulation. However, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV measurements suggest that PCP exam skills need improvement before they can be reliably used in practice.

Visible plaque remains an objective, reversible, and quickly assessed caries risk factor with potential utility in the pediatric well-child visit, regardless of this study's implication on the current state of PCP ability to identify it. Visible plaque at 19 months has been shown to positively correlate to the occurrence of caries at 36 months,2,14 and several other studies have confirmed the relationship between visible plaque and caries in young children.15-20 In addition, a systematic review of caries risks for young children suggested that although they are likely to develop caries if the bacteria Streptococcus mutans is acquired early, this risk may be compensated for by good oral hygiene (ie, good plaque control) and a noncariogenic diet.21 An emphasis on plaque control needs to be communicated during well-child care because the prevalence of visible plaque in young, low-income populations has been reported to be as high as 42% to 52%, similar to the prevalence of 50% in this study.16,22 If visible plaque can be detected on children's teeth during well-child care, counseling can be targeted to oral hygiene techniques that remove this very tangible risk.

This study had several limitations. It was conducted at a single, urban, academic site with a largely minority, low-income population and, therefore, cannot be generalized to other clinic types, or other racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups. However, the child demographics were consistent with reports of children at highest risk for the development of ECC.2,23 In addition, the analysis did not correct for the varying levels of oral health training and experience of the different PCPs. However, the resident participants had completed the children's section of the Smiles for Life Oral Health Curriculum approximately 6 months prior to study initiation as part of ongoing clinical review for providers in the practice. In addition, approximately 1 year prior to the study, all attending and nurse practitioner PCPs had undergone oral health training that certified them to receive Medicaid reimbursement for fluoride varnish applications in the state of Pennsylvania. Therefore, providers in this study may have had at least equal or more oral health training than the typical pediatric PCP. Regardless, neither the Smiles for Life Curriculum nor the fluoride varnish training included instruction on how to identify visible plaque. This study only used 1 hygienist to serve as the gold standard in the visible plaque exams; therefore, a consensus between several experts in dental hygiene was not used to determine the appropriate plaque score received by each child. This study did not randomize the enrollment of PCPs and child/parent participants, which may have created bias in the results. For example, it is not known if the typical child presenting for well-child care on days that the dental hygienist was enrolling patients had characteristics pre-disposing him or her to visible plaque that was different from those typically presenting on other days of the week. Also, because of its small sample size, this study was not able to determine provider improvement with the visible plaque exam over time.

Despite abundant evidence of the importance of and policies supporting PCP assessments of children's oral health, many clinicians report inconsistent screening practices and inadequate oral health training. In a 2009 survey of pediatricians, only 54% of respondents reported examining the teeth of more than half of their 0- to 3-year-old patients, and less than 25% had received oral health education in medical school, residency, or continuing education.24 Fortunately, recent studies illustrate that pediatricians can be trained to successfully incorporate oral health teaching and interventions into their practices, such as the use of fluoride varnish.25-27 Pediatricians can also be trained to accurately identify advanced dental caries in children's teeth and provide effective oral health counseling.28,29 However, it is also desirable for clinicians to detect visible plaque as an early warning sign of caries that signals a chance to intervene before disease progresses. This study demonstrates that PCPs require further training before they can reliably do this.

Regardless of training, PCPs have acknowledged difficulties providing comprehensive care to their patients and frequently cite a lack of time to address all their patients’ preventive health issues.30,31 Therefore, this study suggests a benefit in partnering with trained dental professionals in well-child care for young children. For example, integrating dental hygienist services into a well-child care setting may provide the needed time and expertise for a complete caries risk assessment, oral health counseling, and possibly even preventive treatments, without further burdening the well-child visit conducted by the PCP. This suggestion is in line with a Government Accountability Office Report that recommends more effort be applied to PCP education or the use of ancillary staff for addressing children's oral health.23 Some models of integrated pediatric and dental care have already emerged across the country, but they remain the exception.32,33 Either through further education and/or integration of dental services, pediatricians who provide well-child care must be able to offer meaningful caries risk assessments to their patients, especially since the current recommendation for all children to visit a dentist by age 1 creates more competition for pediatric dental visits and may further reduce access to dental care for high-risk children.34 However, further research is needed to determine the most feasible means of improving the oral health care received by children during well-child visits.

Conclusions

If a PCP has received the level of oral health training typical for an accredited pediatric health training program, then the visible plaque exam conducted by this PCP during well-child care may not be predictive of the child actually having visible plaque on his or her teeth. This possibly reflects a larger difficulty with well-child care, in which the PCP often lacks the time or skill to address all screenings and assessments recommended. Therefore, to improve the caries risk component of well-child care and comply with oral health screening recommendations, PCPs either need to receive further education in oral health exams or incorporate trained ancillary staff into their practices.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the General Academic Pediatric Fellowship Program of Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC for support and guidance during this project, as well as all funders, and the support staff in the Division of General Academic Pediatrics at Children's Hospital of UPMC.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by a Seed Grant from the Research Advisory Committee at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Grant Number 11_0018 from the Dental Trade Alliance Foundation, Grant Number UL1RR024153 from NIH/NCRR/CTSA (Pediatric PittNet), and Grant Number T32HS019486 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting institutions. The principal investigator had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Dye BA, Arevalo O, Vargas CM. Trends in paediatric dental caries by poverty status in the United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:132–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinanoff N, Reisine S. Update on early childhood caries since the Surgeon General's Report. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vargas CM, Crall JJ, Schneider DA. Sociodemographic distribution of pediatric dental caries: NHANES III, 1988-1994. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1229–1238. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mouradian WE, Wehr E, Crall JJ. Disparities in children's oral health and access to dental care. JAMA. 2000;284:2625–2631. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preventive oral health intervention for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1387–1394. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hale KJ. Oral health risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5)(pt 1):1113–1116. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatric Dentisty [March 15, 2013];Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents. 2010 http://www.aapd.org/ media/Policies_Guidelines/G_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf. [PubMed]

- 8. [May 27, 2012];Oral Health Risk Assessment Tool. http://www2.aap.org/commpeds/dochs/oralhealth/RiskAssessmentTool.html.

- 9.Douglass AB, Gonsalves W, Maier R, et al. Smiles for Life: a national oral health curriculum for family medicine. A model for curriculum development by STFM groups. Fam Med. 2007;39:88–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Sullivan DM, Tinanoff N. Maxillary anterior caries associated with increased caries risk in other primary teeth. J Dent Res. 1993;72:1577–1580. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720120801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. StataCorp; College Station, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alaluusua S, Malmivirta R. Early plaque accumulation: a sign for caries risk in young children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22(5)(pt 1):273–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Declerck D, Leroy R, Martens L, et al. Factors associated with prevalence and severity of caries experience in preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:168–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanasi E, Johansson I, Lu SC, et al. Microbial risk markers for childhood caries in pediatricians’ offices. J Dent Res. 2010;89:378–383. doi: 10.1177/0022034509360010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parisotto TM, Steiner-Oliveira C, Silva CM, Rodrigues LK, Nobre-dos-Santos M. Early childhood caries and mutans Streptococci: a systematic review. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paunio P, Rautava P, Helenius H, Alanen P, Sillanpaa M. The Finnish Family Competence Study: the relationship between caries, dental health habits and general health in 3-year-old Finnish children. Caries Res. 1993;27:154–160. doi: 10.1159/000261534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seow WK, Clifford H, Battistutta D, Morawska A, Holcombe T. Case-control study of early childhood caries in Australia. Caries Res. 2009;43:25–35. doi: 10.1159/000189704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wendt LK, Hallonsten AL, Koch G, Birkhed D. Oral hygiene in relation to caries development and immigrant status in infants and toddlers. Scand J Dent Res. 1994;102:269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1994.tb01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris R, Nicoll AD, Adair PM, Pine CM. Risk factors for dental caries in young children: a systematic review of the literature. Community Dent Health. 2004;21(1)(suppl):71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren JJ, Weber-Gasparoni K, Marshall TA, et al. Factors associated with dental caries experience in 1-year-old children. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68:70–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Government Accountability Office . Efforts Under Way to Improve Children's Access to Dental Services, but Sustained Attention Needed to Address Ongoing Concerns. US General Accountability Office; Washington, DC: 2010. [April 3, 2011]. Publication GAO-11-96. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d1196.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis CW, Boulter S, Keels MA, et al. Oral health and pediatricians: results of a national survey. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozier RG, Sutton BK, Bawden JW, Haupt K, Slade GD, King RS. Prevention of early childhood caries in North Carolina medical practices: implications for research and practice. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:876–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis C, Lynch H, Richardson L. Fluoride varnish use in primary care: what do providers think? Pediatrics. 2005;115:e69–e76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant JS, Roberts MW, Brown WD, Quinonez RB. Integrating dental screening and fluoride varnish application into a pediatric residency outpatient program: clinical and financial implications. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2007;31:175–178. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.31.3.y7501427n240u793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierce KM, Rozier RG, Vann WF., Jr Accuracy of pediatric primary care providers’ screening and referral for early childhood caries. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E82. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Stearns SC, Quinonez RB. Effectiveness of preventive dental treatments by physicians for young Medicaid enrollees. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e682–e689. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bethell C, Reuland CH, Halfon N, Schor EL. Measuring the quality of preventive and developmental services for young children: national estimates and patterns of clinicians’ performance. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6)(suppl):1973–1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun P, Kahl S, Widmer K, Ellison M, Daley M. Co-locating dental hygienists, staff, and parents. Poster session presented at: General Pediatrics and Preventive Pediatrics.. Academic Societies Annual Meeting; Denver, Colorado. 2011 April 30-May 3. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stearns SC, Rozier RG, Kranz AM, Pahel BT, Quinonez RB. Cost-effectiveness of preventive oral health care in medical offices for young Medicaid enrollees. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:945–951. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones K, Tomar SL. Estimated impact of competing policy recommendations for age of first dental visit. Pediatrics. 2005;115:906–914. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]