Abstract

Background

Accurate survival prediction is essential for decision-making in cancer therapies and care planning. Objective physiologic measures may improve the accuracy of prognostication. In this prospective study, we determined the association of phase angle, hand grip strength, and maximal inspiratory pressure with overall survival in patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

We enrolled hospitalized patients with advanced cancer who were seen by palliative care for consultation. We collected information on phase angle, hand grip strength, maximal inspiratory pressure and known prognostic factors including Palliative Prognostic Score (PaP), Palliative Prognostic Index, serum albumin and body composition. We conducted univariate and multivariate survival analysis, and examined the correlation between phase angle and other prognostic variables.

Results

222 patients were enrolled: average age 55 (range 22–79), female 59%, mean Karnofsky Performance Status 55, and median overall survival 106 days (95% confidence interval [CI] 71–128 days). The median survival for patients with phase angle 2–2.9°, 3–3.9°, 4–4.9°, 5–5.9° and ≥6° was 35, 54, 112, 134 and 220 days, respectively (P=0.001). In multivariate analysis, phase angle (hazard ratio [HR]=0.86 per degree increase; 95% CI 0.74–0.99; P=0.04), PaP (HR=1.07; 95% CI 1.02–1.13, P=0.008), serum albumin (HR=0.67, 95% CI 0.50–0.91; P=0.009), and fat free mass (HR=0.98, CI=0.96–0.99; P=0.02) were significantly associated with survival. Phase angle was only weakly (γ<0.4) associated with other prognostic variables.

Conclusions

Phase angle was a novel predictor of poor survival, independent of established prognostic factors in the advanced cancer setting. This objective and non-invasive tool may be useful for bedside prognostication.

Keywords: Electric impedance, neoplasms, palliative care, physiology, prognosis

Introduction

The ability to prognosticate accurately has great implications for patients with advanced cancer because many important medical, personal and financial decisions are related to life expectancy.1 The delivery of high quality of end-of-life care also requires clinicians to accurately distinguish between patients with weeks or days of survival from those with months of survival.2 However, clinicians consistently over-estimate survival in the patients with advanced cancer.3 Although a number of prognostic factors and prognostic models are available, their use are limited by many factors including subjectivity, difficulty in interpretations and low accuracy.4

Phase angle, hand grip strength and maximal inspiratory pressure represent three objective functional measures with prognostic potential in patients with advanced cancer. Phase angle is determined by bioelectric impedance analysis, and represents a novel marker of nutritional and functional status.5 Hand grip strength and maximal inspiratory pressure measure skeletal muscle function in the upper extremity and chest wall, respectively.6, 7 Although these 3 measures have been found to correlate with survival in various patient populations,8–13 their prognostic utility in patients with advanced cancer have not been fully elucidated. A better understanding of their prognostic utility may assist clinicians to estimate survival more accurately and objectively. In this prospective study, we determined the association of phase angle, hand grip strength, and maximal inspiratory pressure with overall survival in patients with advanced cancer.

Patients and Methods

Study Setting and Criteria

We enrolled patients with a diagnosis of advanced cancer who were ≥18 years of age, hospitalized at MD Anderson Cancer Center, seen by the palliative care mobile team for consultation, and received parenteral hydration. Patients with delirium, defibrillator, cardiac pacemaker, inability to use hand held dynamometer due to neuromuscular disorder, joint disease or arm pain, or local infection/wound preventing the use of bioelectric impedance analysis pads were excluded. The Institutional Review Board at MDACC approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent. All patients who met the eligibility criteria were approached for this study. Patient enrollment was conducted between 9/22/2011 and 1/26/2013.

Data Collection

We prospectively collected baseline patient demographics on admission. The palliative care specialist provided both the KPS and the PPS. KPS is an 11-point functional assessment scale ranging between 0% (death) and 100% (completely asymptomatic) based on a patient’s daily function and care needs.14 The PPS is a similar scale modified from KPS that ranges from 0% to 100%, and incorporates a patient’s ambulation, activity level, disease severity, ability to care for self, oral intake and level of consciousness in the scoring.15, 16 Both the KPS and PPS have good predictive validity.17, 18 The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), a validated 10-item symptom battery examining average intensity of pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, and shortness of breath, appetite, feeling of well being and sleep over the past 24 hours using numeric rating scales ranging from 0 (none) to 10 (worst).19, 20

Quality of life was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ C-30), a validated questionnaire consisting of 30 items that encompasses 3 symptom scales (pain, fatigue, nausea/vomiting), 6 single-item symptom items, 5 functional scales (physical, cognitive, role, emotional, and social), and one scale assessing global health status/quality of life.21

We collected data on the Palliative Prognostic Score (PaP) and the Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI). The PaP score is a prognostic scale validated for patients with advanced diseases. It consists of 6 variables (dyspnea, anorexia, KPS, clinician prediction of survival, total leukocyte count and lymphocyte percentage), and ranges from 0 to 17.5.22, 23 The PPI is another validated scale that includes the palliative performance scale, oral intake, edema, dyspnea at rest and delirium.24, 25 PPI is scored between 0 and 15. Higher PaP and PPI scores are associated with a poorer survival. We also collected the serum albumin level closest to the date of study.

Phase angle was assessed using the RJL Systems Quantum IV (Clinton Township, Michigan). This measure has previously been shown to have high reliability and predictive validity.9, 26 We placed the electrodes over the middle of the dorsal surface of the right hand between the distal prominence of the radius and the ulnar styloid, and over the right foot between the medial and the lateral malleoli at the ankle. We then applied a small single frequency (50 Hz) alternating low voltage, electrical current to detect the voltage drop. In healthy individuals, phase angle generally ranges between 5 and 7.27 In addition to phase angle, bioelectrical impedance analysis provided data on body composition. This bedside test took less than 5 minutes to complete.

We examined handgrip strength using a Jamar hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston Rolyan, Chicago, IL). Patients were asked to sit comfortably with their shoulder adducted and elbow flexed to 90°, then to perform 3 maximal isometric contractions 30 s apart using their non-dominant hand. We used the maximum of 3 measures for analysis.9 The hand grip strength varies with age and sex, and normally ranges between 30 and 50 kg.28

Maximal inspiratory pressure was collected using the NS 120-TRR NIF Monitor (Instrumentation Industries Inc., Bethel Park, PA) according the American Thoracic Society Guideline.29 We asked patients to breath tidally for a few breaths, then exhale maximally before inhaling maximally maintaining pressure level for at least 2 seconds. Five consecutive efforts were recorded, with a 1 minute pause between each effort. We used the average of the top 3 measures that varied by <20% for analysis.29 MIP varies with age and sex, with a normal range between 50 and 100 cm H2O.30

Survival from time of APCU admission was collected from institutional databases and electronic health records.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the baseline demographics using descriptive statistics, including means, medians, proportions, standard deviations (SD), interquartile ranges (IQR), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

We used both unadjusted and standardized phase angle (SPA) for analysis, where SPA = (phase angle − age/sex/body mass index specific mean phase angle value)/standard deviation of the age/sex/body mass index specific standard deviation of the healthy population.31 We used the Kaplan Meir method for survival analysis, and log rank tests to compare between groups.

We conducted multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards regression analysis with backward selection incorporating variables with P-value <0.10 in univariate survival analysis. These variables included the PaP score, PPI, serum albumin, fat free mass, unadjusted phase angle, hand grip strength, maximal inspiratory pressure and standardized phase angle. Age and sex were also included because hand grip strength and maximal inspiratory pressure are dependent on these variables. Palliative Performance status and Karnofsky Performance Status were not included in the multivariate model because they were already part of PaP and PPI, and correlated strongly with these prognostic scores.

We also determined the association between phase angle (both unadjusted and standardized) with various prognostic variables using the Spearman Correlation test.

The sample size justification was based on having at least 10 events (i.e. deaths) for each prognostic variable in the multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards regression model. We anticipated observing at least 120 deaths in 200 patients, thereby providing enough information to include up to 12 prognostic variables in the model. In total, we recruited 222 patients to ensure at least 200 patients completed all 3 functional measures.

The Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) were used for statistical analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of 222 hospitalized patients. The mean KPS was 55 (SD 13) and the mean PPS was 56 (SD 12). The median overall survival was 106 days (95% CI 71–128 days). 142/222 (64%) patients have died at the time of analysis, and the median followup for patients who remained alive was 118 days (IQR 26–240 days).

Figure 1. Study Flow Chart.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N=222)

| Characteristics | N (%)* |

|---|---|

| Age, average (range) | 55 (22–79) |

| Female sex | 131 (59) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 147 (66) |

| Black | 44 (20) |

| Hispanic | 29 (13) |

| Others | 2 (1) |

| Education | |

| High school or lower | 117 (53) |

| College | 75 (34) |

| Advanced | 30 (13) |

| Cancer | |

| Breast | 28 (13) |

| Gastrointestinal | 73 (33) |

| Genitourinary | 19 (9) |

| Gynecological | 24 (11) |

| Head and neck | 11 (5) |

| Hematological | 12 (5) |

| Others | 19 (9) |

| Respiratory | 36 (16) |

| Karnofsky performance status, average (SD) | 55 (13) |

| Palliative performance status, average (SD) | 56 (12) |

| Palliative prognostic score, average (SD) | 4.7 (3.6) |

| 0–5.5 | 152 (70) |

| 5.5–11 | 48 (22) |

| 11.1–17.5 | 16 (8) |

| Palliative prognostic index, average (SD) | 2.9 (2.2) |

| 0–4 | 160 (74) |

| 5–6 | 38 (18) |

| 7–15 | 17 (8) |

| Serum albumin in g/dL, average (SD) | 3.3 (0.7) |

| Fat free mass in kg, median (interquartile range) | 51.7 (44.2–61.5) |

| Fat free mass index in kg/m2, median (interquartile range) | 18.6 (16.3–20.6) |

| Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, median (interquartile range) | |

| Pain | 5 (4–8) |

| Fatigue | 6 (4–7) |

| Nausea | 1 (0–5) |

| Depression | 1 (0–4) |

| Anxiety | 3 (0–5) |

| Drowsiness | 5 (2–7) |

| Appetite | 5 (3–8) |

| Well being | 5 (3–6) |

| Dyspnea | 2 (0–5) |

| Sleep | 5 (3–7) |

| EORTC QLQ-C30, average (SD) | |

| Global health status | 36.8 (24.1) |

| Physical | 57 (27.4) |

| Role | 33.6 (31.8) |

| Emotional | 61.5 (29.4) |

| Cognitive | 62.7 (30.2) |

| Social | 40.3 (33.4) |

| Fatigue | 65.2 (24.7) |

| Nausea | 33.7 (32.5) |

| Pain | 73.2 (26.9) |

| Dyspnea | 33.3 (36.8) |

| Insomnia | 54.7 (35.2) |

| Appetite | 57.2 (37) |

| Constipation | 45.3 (37.9) |

| Diarrhea | 23.3 (31.6) |

| Financial | 44.1 (39.3) |

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation

unless otherwise specified

Phase angle, hand grip strength and maximal inspiratory pressure

A total of 209 (94%), 212 (95%) and 212 (95%) patients completed the phase angle, hand grip strength and maximal inspiratory pressure measurements. The main reasons for non-completion were device malfunction and patient refusal.

The median unadjusted phase angle was 4.4° (IQR 3.5°, 5.3°), and the median SPA was −2.1 (IQR −3.2, −0.89), which was significantly lower than the norm for any given age, sex and body mass index. The median hand grip strength was 22 kg (IQR 18, 32 kg) and the maximal inspiratory pressure was 40 cm H2O (IQR 29, 60 cm H2O).

Survival analysis

In univariate analysis, patients with lower KPS (P=0.001) and PPS (P<0.001) had a poorer survival (Table 2). Higher PPI (P=0.003) and PaP (P9003C;0.001) scores, hypoalbuminemia (P<0.001) and lower fat free mass (P=0.02) were also associated with a shorter survival.

Table 2.

Univariate Survival Analysis

| Characteristics | N | Median survival (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤60 | 142 | 117 (78–164) | 0.22 |

| >60 | 78 | 88 (51–125) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 131 | 117 (68–149) | 0.87 |

| Male | 89 | 102 (62–133) | |

| Palliative prognostic index | |||

| 0–4 | 160 | 122 (89–155) | 0.003 |

| 5–6 | 38 | 63 (0–150) | |

| 7–15 | 17 | 16 (10–22) | |

| Palliative prognostic score | |||

| 0–5.5 | 152 | 143 (116–170) | <0.001 |

| 5.6–11 | 48 | 62 (35–89) | |

| 11.1–17.5 | 16 | 44 (0–89) | |

| Palliative performance scale | |||

| 60–100% | 113 | 143 (105–181) | <0.001 |

| 10–50% | 102 | 62 (43–81) | |

| Karnofsky performance scale | |||

| 60–100% | 102 | 134 (92–176) | 0.001 |

| 10–50% | 114 | 63 (39–87) | |

| Fat free mass | |||

| ≤51,6 kg | 103 | 63 (50–76) | 0.02 |

| >51.6 kg | 103 | 134 (98–170) | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | |||

| <3.5 mg/dL | 127 | 71 (41–100) | <0.001 |

| ≥3.5 mg/dL | 85 | 168 (94–242) | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | |||

| <3.0 mg/dL | 64 | 50 (28–73) | <0.001 |

| ≥3.0 mg/dL | 148 | 134 (93–175) | |

| Unadjusted phase angle | |||

| ≤4.4° | 105 | 54 (36–73) | 0.001 |

| >4.4° | 104 | 134 (93–175) | |

| Unadjusted phase angle | |||

| 2–2.99° | 18 | 35 (29–41) | 0.001 |

| 3–3.99° | 55 | 54 (31–77) | |

| 4–4.99° | 59 | 112 (64–160) | |

| 5–5.99° | 45 | 134 (110–158) | |

| ≥6° | 32 | 220 (50–390) | |

| Standardized phase angle | |||

| Upper 95th percentile | 74 | 168 (100–236) | <0.001 |

| Lower 5th percentile | 134 | 68 (40–96) | |

| Hand grip strength | |||

| ≤22 kg | 112 | 71 (18–125) | 0.08 |

| >22 kg | 110 | 122 (92–162) | |

| Maximal inspiratory pressure | |||

| ≤40 cm H2O | 90 | 68 (52–84) | 0.08 |

| >40 cm H2O | 132 | 122 (99–145) |

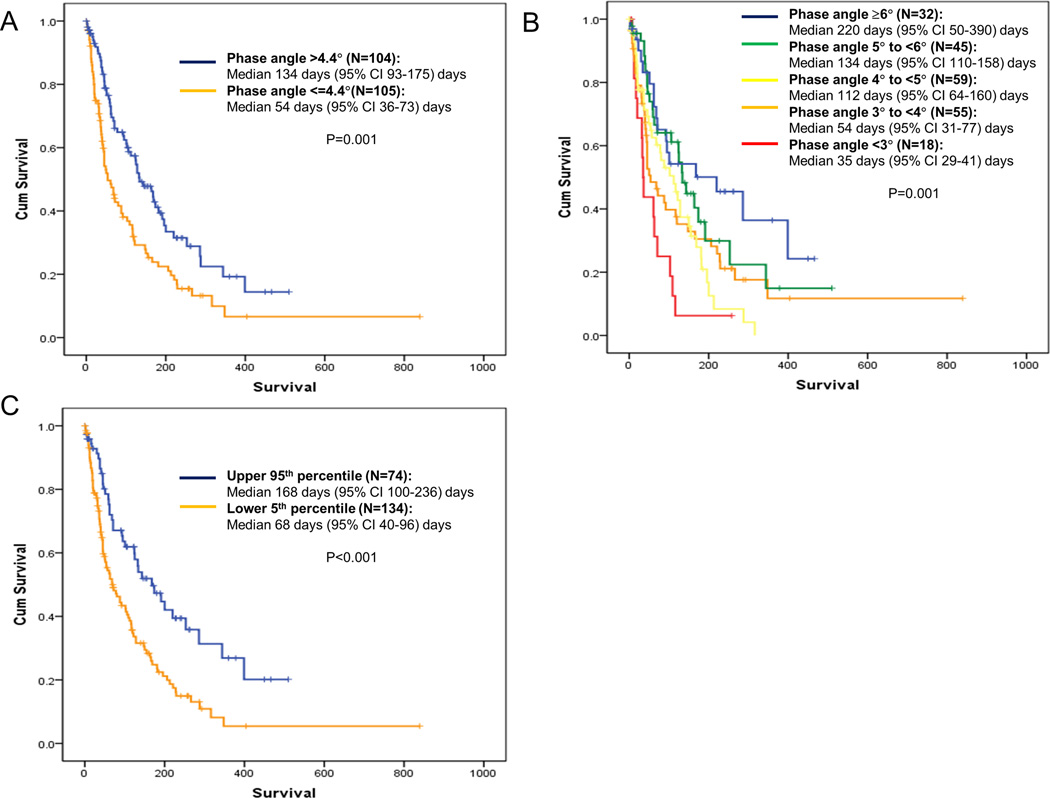

Both unadjusted phase angle (P=0.001) and standardized phase angles (P<0.001) were significantly associated with overall survival. In contrast, hand grip strength and maximal inspiratory pressure only showed a trend towards significance.

In multivariate analysis, lower phase angle, higher PaP score, lower serum albumin level and lower fat free mass were independently associated with a shorter survival (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis

| Variables | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Palliative Prognostic Score (per point increase) | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 0.008 |

| Phase angle (per degree increase) | 0.86 (0.74–0.99) | 0.04 |

| Albumin (per g/dL increase) | 0.67 (0.50–0.91) | 0.009 |

| Fat free mass (per kg increase) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.02 |

Variables entered into the model included Palliative Prognostic Scale, Palliative Prognostic Index, serum albumin level, fat free mass, hand grip strength, maximal inspiratory pressure, and standardized phase angle all as continuous variables.

Correlation between phase angle and other variables

Table 4 shows that the phase angle was associated with many known prognostic variables, including the Palliative Performance Status, Karnofsky Performance Status, PaP score, PPI, hand grip strength, maximal inspiratory pressure, serum albumin, and fat free mass. However, the correlation was weak (γ <0.4).

Table 4.

Correlation between phase angle and other prognostic variables*

| Variables | Phase angle | Standardized phase angle | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | γ | P-value | N | γ | P-value | |

| Standardized phase angle | 208 | 0.76 | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| Palliative Performance Status | 215 | 0.18 | 0.007 | 202 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | 216 | 0.18 | 0.007 | 202 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| Palliative Prognostic Score | 216 | −0.21 | 0.002 | 202 | −0.19 | 0.007 |

| Palliative Prognostic Index | 215 | −0.22 | 0.001 | 202 | −0.18 | 0.01 |

| Clinician Prediction of Survival | 216 | 0.075 | 0.28 | 202 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Hand Grip Strength | 212 | 0.35 | <0.001 | 198 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| Maximal Inspiratory Pressure | 212 | 0.23 | 0.001 | 198 | 0.04 | 0.60 |

| Serum albumin | 202 | 0.37 | <0.001 | 201 | 0.35 | 0.001 |

| Fat free mass | 202 | 0.29 | <0.001 | 201 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| Fat free mass index | 202 | 0.33 | <0.001 | 201 | 0.22 | 0.001 |

Spearman correlation test

DISCUSSION

Accurate survival prediction is essential to guide decisions regarding cancer treatments and care planning; however, survival estimation remains a challenge in the advanced cancer population, prompting the need for new objective tools that can be easily applied in the clinical setting. In this study, we confirmed the prognostic significance of many known prognostic factors, such as the PaP score, hypoalbuminemia and lean body mass. We also identified phase angle as a significant predictor of poor survival, independent of established prognostic factors in the advanced cancer setting. Phase angle has multiple advantages including objectivity, reproducibility, non-invasiveness, ease of operation, portability and low cost. The Quantum IV bioelectrical impedance analysis system costs approximately $2500, and the electrodes cost less than $1 per patient. The test took less than 5 minutes to complete. Upon further validation, phase angle may facilitate prognosis-based clinical decision making.

Our study is unique because it included a relatively homogeneous population with a short survival. Previous studies in cancer patients have mostly been retrospective32–35 or enrolled patients with mixed stages.9, 36, 37 One of the key issues related to prognostication is the inception cohort. While tumor-related factors such as stage and grade drive prognosis for patients with early cancer; they often lose their ability to discriminate survival among patients with months or weeks of life expectancy. Instead, functional status and symptom burden become more important. Our data suggest that phase angle was able to discriminate among patients with a short life expectancy. Our findings are consistent with a study of 50 cancer patients admitted to a palliative care unit reporting that a higher phase angle had a trend towards improved survival.8

Our findings are robust because (1) of the gradient effect in phase angle (Figure 2C) and (2) phase angle retained its prognostic significance in the context of many known prognostic factors.38 The PaP Score already incorporates the KPS, Clinician Prediction of Survival, dyspnea, anorexia and 2 laboratory variables associated with inflammation (leukocytosis and lymphopenia). Furthermore, phase angle remains independently significant despite the inclusion of hypoalbuminemia and low lean body mass, two key markers of poor nutritional status.

Figure 2. Kaplan Meir Survival Curves by Phase Angle.

Overall survival was calculated from time of study assessments to last followup date or death. (A) Unadjusted phase angle with median as cutoff, (B) Unadjusted phase angle with cutoffs by degree, (C) standardized phase angle comparing between patients who had phase angle values in the upper 95th percentile versus the lower 5th percentile of age, sex and body mass index matched healthy controls. A lower phase angle was significantly associated with a shorter survival.

Phase angle represents a novel marker of cellular function. It is determined using the following formula: phase angle = arc-tangent(reactance/resistance)×180°/π. In this study, we specifically controlled for resistance by enrolling only patients with adequate hydration, thus phase angle was based mostly on reactance, which is in turn a function of cellular mass and membrane integrity.27 These cellular properties may be compromised by inflammatory cytokines, tumor by-products, and altered host homeostasis, putting a patient at risk of life-threatening complications such as sepsis, infarction and thromboembolic events. Indeed, changes in electrophysiologic parameters have been found to associated with an increased risk of bacteremia.39 Patients with a lower phase angle also had a higher risk of complications after surgical procedures.40 Thus, in addition to being a marker of cellular function, muscle mass and nutritional status, phase angle may be a predictive factor of the risk of acute catastrophic complications. Interestingly, phase angle was weakly but significantly associated with other prognostic variables, suggesting that it captures some additional information compared to existing prognostic factors. Further studies are needed to examine the physiologic and cellular changes associated with phase angle.

Although some studies advocated for the use of phase angle adjusted by age, sex and body mass index, others have used unadjusted phase angles.27 In our analyses, both unadjusted and standardized phase angles were significantly associated with survival, and correlated with each other. Given the use of adjusted phase angle is cumbersome and provides little additional information, our data justify the use of unadjusted phase angle. Another common question is regarding the cutoff of phase angle. In our cohort, unadjusted phase angle of 2–3, 4–5 and ≥6 was associated with a median survival of <3 months, 3–6 months and >6 months. Upon further validation, these cutoffs may have practical implications for clinical decision making, such as hospice referral, initiation and discontinuation of palliative systemic therapies, and advance care planning.

In our study, lower hand grip strength and maximal inspiratory pressure also had a trend towards shorter survival, albeit non-statistically significant. Our finding is in contrast to studies involving other patient populations demonstrating that impaired muscle strength is associated with a poorer prognosis.13, 41–44 One potential explanation is that our patients were all hospitalized and quite deconditioned, which could compromise the prognostic value of these measures. Another consideration is that our patients had a short survival, and muscle function provides limited differentiation in this setting. Further research of these measures in the ambulatory oncology setting may be useful.

Our study has several limitations. First, we only enrolled hospitalized patients with advanced cancer seen by palliative care. These patients were acutely ill and symptomatic, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, the data was collected at a single tertiary care center. Further research is necessary to determine if our findings also apply in the outpatient and community settings. Third, we did not collect C-reactive protein (CRP) which has known prognostic utility and has been reported to be associated with phase angle.45 Instead, we included indirect measures such as serum albumin and white blood cell count in our analysis. Future studies should examine the prognostic utility of CRP in the context of phase angle. Finally, we only included patients who had been receiving parenteral hydration to ensure a homogenous population for study purposes. Our phase angle findings could also apply to patients who are well hydrated by the oral route as well, although this remains to be confirmed. Future research should also examine the accuracy of phase angle for prognostication in patients who are dehydrated.

In summary, we found that phase angle was a significant predictor of survival in patients with advanced cancer, independent of established prognostic factors such as the PaP Score and nutritional status. This non-invasive bedside tool is objective, reliable, inexpensive and easy to use. Future studies may examine the utility of phase angle alone or in combination with other prognostic tools, and how phase angle may inform prognosis-based clinical decision making in the advanced cancer setting.

Acknowledgments

Research support: This research is supported in part by a University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (CA 016672). EB is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (grant numbers RO1CA1RO10162-01A1, RO1CA1222292-01 and RO1CA124481-01). The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: No relevant disclosure for all authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Complexities in prognostication in advanced cancer: "to help them live their lives the way they want to". JAMA. 2003;290(1):98–104. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ, Block S. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1133–1138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, Hudson M, Eychmuller S, Simes J, et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):195–198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glare PA, Sinclair CT. Palliative Medicine review: prognostication. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(1):84–103. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbosa-Silva MC, Barros AJ. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in clinical practice: a new perspective on its use beyond body composition equations. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8(3):311–317. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000165011.69943.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norman K, Stobaus N, Gonzalez MC, Schulzke JD, Pirlich M. Hand grip strength: Outcome predictor and marker of nutritional status. Clin Nutr. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochester DF. Respiratory muscles and ventilatory failure: 1993 perspective. Am J Med Sci. 1993;305(6):394–402. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199306000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis MP, Yavuzsen T, Khoshknabi D, Kirkova J, Walsh D, Lasheen W, et al. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle changes during hydration and prognosis in advanced cancer. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2009;26(3):180–187. doi: 10.1177/1049909108330028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norman K, Stobaus N, Zocher D, Bosy-Westphal A, Szramek A, Scheufele R, et al. Cutoff percentiles of bioelectrical phase angle predict functionality, quality of life, and mortality in patients with cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):612–619. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwenk A, Beisenherz A, Romer K, Kremer G, Salzberger B, Elia M. Phase angle from bioelectrical impedance analysis remains an independent predictive marker in HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;72(2):496–501. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desport JC, Marin B, Funalot B, Preux PM, Couratier P. Phase angle is a prognostic factor for survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2008;9(5):273–278. doi: 10.1080/17482960801925039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mushnick R, Fein PA, Mittman N, Goel N, Chattopadhyay J, Avram MM. Relationship of bioelectrical impedance parameters to nutrition and survival in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003;87(87):S53–S56. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s87.22.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgev VA, Kostianev SS. Maximal inspiratory pressure predicts mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a five-year follow-up. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2006;48(3–4):36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(3):187–193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. J Palliat Care. 1996;12(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho F, Lau F, Downing MG, Lesperance M. A reliability and validity study of the Palliative Performance Scale. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M. Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(7):1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Pittureri C, Martini F, Montanari L, Amaducci E, et al. Prospective comparison of prognostic scores in palliative care cancer populations. Oncologist. 2012;17(3):446–454. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nekolaichuk C, Watanabe S, Beaumont C. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: a 15-year retrospective review of validation studies (1991--2006) Palliat Med. 2008;22(2):111–122. doi: 10.1177/0269216307087659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glare P, Virik K. Independent prospective validation of the PaP score in terminally ill patients referred to a hospital-based Palliative Medicine consultation service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(5):891–898. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maltoni M, Nanni O, Pirovano M, Scarpi E, Indelli M, Martini C, et al. Successful validation of the palliative prognostic score in terminally ill cancer patients. Italian Multicenter Study Group on Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(4):240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. The Palliative Prognostic Index: a scoring system for survival prediction of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7(3):128–133. doi: 10.1007/s005200050242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone CA, Tiernan E, Dooley BA. Prospective validation of the palliative prognostic index in patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(6):617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dittmar M. Reliability and variability of bioimpedance measures in normal adults: effects of age, gender, and body mass. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2003;122(4):361–370. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman K, Stobaus N, Pirlich M, Bosy-Westphal A. Bioelectrical phase angle and impedance vector analysis--clinical relevance and applicability of impedance parameters. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(6):854–861. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Werle S, Goldhahn J, Drerup S, Simmen BR, Sprott H, Herren DB. Age- and gender-specific normative data of grip and pinch strength in a healthy adult Swiss population. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2009;34(1):76–84. doi: 10.1177/1753193408096763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ATS/ERS Statement on respiratory muscle testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(4):518–624. doi: 10.1164/rccm.166.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harik-Khan RI, Wise RA, Fozard JL. Determinants of maximal inspiratory pressure. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 1):1459–1464. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9712006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosy-Westphal A, Danielzik S, Dorhofer RP, Later W, Wiese S, Muller MJ. Phase angle from bioelectrical impedance analysis: population reference values by age, sex, and body mass index. JPENJournal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 2006;30(4):309–316. doi: 10.1177/0148607106030004309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Burrows JL, Dahlk SL, Vashi PG, Grutsch JF, et al. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle in clinical practice: implications for prognosis in advanced colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6):1634–1638. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Vashi PG, King J, Dahlk SL, Grutsch JF, et al. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle as a prognostic indicator in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:249. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Vashi PG, King J, Dahlk SL, Grutsch JF, et al. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle in clinical practice: implications for prognosis in stage IIIB and IV non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta D, Lis CG, Dahlk SL, Vashi PG, Grutsch JF, Lammersfeld CA. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle as a prognostic indicator in advanced pancreatic cancer. The British Journal of Nutrition. 2004;92(6):957–962. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santarpia L, Marra M, Montagnese C, Alfonsi L, Pasanisi F, Contaldo F. Prognostic significance of bioelectrical impedance phase angle in advanced cancer: preliminary observations. Nutrition. 2009;25(9):930–931. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paiva SI, Borges LR, Halpern-Silveira D, Assuncao MC, Barros AJ, Gonzalez MC. Standardized phase angle from bioelectrical impedance analysis as prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19(2):187–192. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0798-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, Broeckaert B, Christakis N, Eychmueller S, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: evidence-based clinical recommendations--a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6240–6248. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwenk A, Ward LC, Elia M, Scott GM. Bioelectrical impedance analysis predicts outcome in patients with suspected bacteremia. Infection. 1998;26(5):277–282. doi: 10.1007/BF02962247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbosa-Silva MC, Barros AJ. Bioelectric impedance and individual characteristics as prognostic factors for post-operative complications. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(5):830–838. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R. Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Izawa KP, Watanabe S, Osada N, Kasahara Y, Yokoyama H, Hiraki K, et al. Handgrip strength as a predictor of prognosis in Japanese patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(1):21–27. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32831269a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rantanen T, Volpato S, Ferrucci L, Heikkinen E, Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Handgrip strength and cause-specific and total mortality in older disabled women: exploring the mechanism. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):636–641. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer FJ, Borst MM, Zugck C, Kirschke A, Schellberg D, Kubler W, et al. Respiratory muscle dysfunction in congestive heart failure: clinical correlation and prognostic significance. Circulation. 2001;103(17):2153–2158. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.17.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stobaus N, Pirlich M, Valentini L, Schulzke JD, Norman K. Determinants of bioelectrical phase angle in disease. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(8):1217–1220. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511004028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]