Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Ischemic stroke is the dominant subtype of stroke and results from focal cerebral ischemia due to occlusion of major cerebral arteries. Thus, the restoration or improvement of reduced regional cerebral blood supply in a timely manner is very critical for improving stroke outcomes and post-stroke functional recovery. The recovery from ischemic stroke largely relies on appropriate restoration of blood flow via angiogenesis. Newly formed vessels would allow increased cerebral blood flow, thus increasing the amount of oxygen and nutrients delivered to affected brain tissue. Angiogenesis is strictly controlled by many key angiogenic factors in the central nervous system, and these molecules have been well-documented to play an important role in the development of angiogenesis in response to various pathological conditions. Promoting angiogenesis via various approaches that target angiogenic factors appears to be a useful treatment for experimental ischemic stroke. Most recently, microRNAs (miRs) have been identified as negative regulators of gene expression in a post-transcriptional manner. Accumulating studies have demonstrated that miRs are essential determinants of vascular endothelial cell biology/angiogenesis as well as contributors to stroke pathogenesis. In this review, we summarize the knowledge of stroke-associated angiogenic modulators, as well as the role and molecular mechanisms of stroke-associated miRs with a focus on angiogenesis-regulating miRs. Moreover, we further discuss their potential impact on miR-based therapeutics in stroke through targeting and enhancing post-ischemic angiogenesis.

Keywords: microRNAs, angiogenesis, angiogenesis-regulating microRNAs (angiomiRs), cerebrovascular diseases, ischemic stroke, angiogenic factors, vascular endothelial cells, neurovascular unit

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a major cerebrovascular disease resulting from a transient or permanent local reduction of cerebral blood flow, characterized by a set of cellular disturbances. With a mortality rate of 30%, stroke is the fourth leading cause of death and also the leading cause of adult disability in the United States. Currently, thrombolytic therapy within a narrow time window is the only acute therapeutic intervention for ischemic stroke, and as a result, development of new, effective therapies is urgently required [1-3]. During the past two decades, the effectiveness of neuroprotectants has been demonstrated in rodent experimental stroke models. However, clinical trials have failed to show a beneficial effect of neuroprotectants against stroke, implying that solely focusing on neuroprotection is not sufficient. Thus, greater attention has been paid to the local environment of the surviving neuron, such as the cerebral microvasculature and neurovascular unit [4-9]. In particular, the concept of the neurovascular unit (NVU), a complicated cerebral network that includes cerebral vascular cells (endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and pericytes), neuroglial cells (astrocytes, microglial cells, and oligodendrocytes), neurons and the extracellular matrix, has been developed and emerged as a new paradigm for the mechanistic investigation and therapeutic intervention in stroke [5, 7, 8, 10, 11]. There is increasing evidence demonstrating that the pathophysiological responses following stroke are composed of acute neurovascular injury (BBB breakdown and neural cell death) as well as delayed neurovascular repair (angiogenesis, neurogenesis). Understanding the critical mediators in the regulation of post-ischemic NVU remodeling events may eventually lead us to discover novel targets for the treatment of stroke.

Angiogenesis refers to the generation of new blood vessels from existing vascular endothelial cells (ECs) in order to deliver nutrients and oxygen to various organs and tissue [12, 13]. It is a normal physiological process in tissue growth and development that may also occur as a natural defense response against neurological diseases, such as stroke. Extensive studies have shown that post-ischemic angiogenesis plays a crucial role in the recovery of blood flow in affected brain regions [14-17]. Thus, angiogenic vessels in the ischemic boundary zone may contribute to recovery of tissue-at-risk by restoring cellular metabolism in surviving neurons as well as provide the essential neurotrophic support to newly generated neurons. Indeed, it has been well-established that stimulation of angiogenesis can be therapeutic in ischemic heart or cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, and wound healing. In the healthy condition, angiogenesis is strictly controlled by a dynamic balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors. When this balance of angiogenic factors is disturbed, it usually causes increased or decreased blood-vessel formation in diseases. Accumulating endogenous pro-angiogenic molecules have been identified, including matrix metalloproteinases, cytokines, integrins, and growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factors (FGF), transforming growth factors (TGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF).

MicroRNAs (miRs) have been recently discovered as a novel family of noncoding small RNAs that negatively modulate protein expression in various organisms [18-21]. MiRs hybridize to partially complementary binding sequences that are typically localized in the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTR) of target mRNAs, resulting in either cleavage or translational repression in a sequence-specific manner. It is now evident that miRs are able to regulate expression of at least one-third of the human genome and play a critical role in various biological processes, including cell differentiation, apoptosis, development, angiogenesis and metabolism [18, 22-27]. MiRs are abundantly expressed in the nervous system and have been implicated in a variety of human neurological diseases [28-40]. We and others have recently shown the involvement of miRs in the pathogenesis of ischemic brain injury by using rodent stroke models, suggesting miRs as potential therapeutic targets in stroke [37-41].

Recently, accumulating studies have revealed important roles for miR in regulating angiogenesis [25-27]. For example, mice with EC-specific deletion of Dicer display defective postnatal angiogenesis [42, 43]. In this review article, we summarize the research progress describing the role and mechanisms of miRs in ischemic stroke and post-ischemic angiogenic processes. We also discuss the potential clinical applications of these small non-coding RNA molecules as new biomarkers and/or therapeutic targets for ischemic stroke.

1. Angiogenesis-based vascular remodeling and stroke recovery

1.1 Vascular angiogenic remodeling after stroke

Ischemic stroke results in severe reduction of cerebral blood flow and lack of oxygen and nutrients in affected brain tissue, which ultimately leads to neuronal cell death and brain infarction. Thus, re-establishment of the functional cerebral microvasculature network will improve regional blood supply and promote stroke recovery. Angiogenesis is a biological process involving the growth of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels. Although angiogenesis is completely suppressed under normal physiological conditions in adult brains, studies from human and experimental stroke indicate that neovascularization is present in the adult brains after cerebral ischemia [44-46]. Of importance, the extent of angiogenesis is often closely associated with reduced cerebral infarction and improved neurological recovery. Thus, promoting post-ischemic angiogenesis may become a useful therapeutic strategy for treatment of acute ischemic stroke in the clinical settings.

By using rodent transient or permanent focal cerebral ischemia models, intensive studies have demonstrated that cerebral vascular endothelial cells start to proliferate in the peri-infarcted region as early as 12-24h after the onset of stroke [44-46]. This ischemia/hypoxia-induced vascular remodeling leads to increased microvessel density surrounding the infarcted brain area three days following ischemic injury. Neovascularization can occur actively for a longer time in the ischemic region, as evidenced by the findings of Hayashi et al. showing that vessel proliferation continued for more than 21 days following experimental cerebral ischemia [45].

In human stroke patients, pioneering studies demonstrated that active angiogenesis takes place at 3-4 days following ischemic insults [47]. Furthermore, analysis of post mortem brain tissues obtained from patients with varying survival times following stroke revealed increased cerebral microvessel density in the penumbral areas in comparison with the contralateral normal hemisphere. Of note, stroke patients with greater cerebral blood vessel density appear to make better progress and survive longer than patients with lower vascular density [47, 48], suggesting that active post-ischemic angiogenesis may be beneficial for neurological functional recovery.

1.2 Stroke-associated angiogenic factors

During stroke, ischemic insults rapidly trigger transcription of a variety of genes and proteins that may be involved in the process of angiogenesis [14-17]. Here we summarize the major factors that have been identified and associated with the development of angiogenesis after stroke.

VEGF

In brain tissue, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is produced and secreted by many neurovascular cells including neurons, astrocytes, and vascular endothelial cells [14, 49-51]. VEGF from various cellular sources binds to its receptors on nearby vascular endothelial cells to directly initiate an angiogenic response. The binding of VEGF to its receptors (VEGFR-1 or -2) on the surface of vascular endothelial cells activates intracellular tyrosine kinases and triggers multiple downstream signals (PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK protein kinase pathways) that promote angiogenesis [15, 52]. VEGF has been identified as a central mediator in post-ischemic angiogenesis. A significantly increased VEGF mRNA and protein expression was observed in the penumbra following experimental cerebral ischemia as early as three hours after an ischemic insult and continued three to seven days following stroke [46, 53, 54]. Infusion of VEGF into brain tissue or transgenic overexpression of the VEGF gene in mice has been documented to promote angiogenesis, decrease infarct volume, and reduce neurological deficits after focal cerebral ischemia [55-57]. VEGF has also been demonstrated to exist in microvessels at penumbra after stroke [49, 51, 53, 54, 58, 59]. Accordingly, increased levels of VEGF have been identified in human brains and serum after ischemic stroke [60, 61].

bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) is weakly expressed in the normal brain but its levels are significantly increased after cerebral ischemia. Lin et al. [62] reported that the majority of bFGF protein is localized in reactive astrocytes and that a significant increase in bFGF expression began at one hour and remained for up to 14 days after ischemia. Enhanced levels of bFGF were also observed in neurons adjacent to the infarct after one day. In addition, macrophages, endothelial cells, and reactive astrocytes express mild to moderate bFGF expression levels in the first two weeks following MCA occlusion [63]. In human brain, this growth factor is overexpressed following ischemic stroke [64].

PDGF

In addition to its neuroprotective roles in neurons [65-67], many studies have shown that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and its receptor are involved in the development of angiogenesis. PDGF and PDGF receptors were induced in microvessels in a rat cerebral ischemia model [68]. In particular, it is believed that vascular pericytes are the main source of PDGF receptor expression in the brain. Similar to the embryonic brain, the PDGF system might be implicated in vascular maturation in the ischemic brain.

TGFβ

Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) regulates cellular apoptosis, proliferation, migration and differentiation in most cells [69], which is attributed to the induction of angiogenesis [70, 71]. After cerebral ischemia, TGF-β was significantly increased in activated astrocytes, microglial cells [72, 73], and microvessels [74] in the ischemic areas. Upregulation of TGF-β mRNA has also been observed in the ischemic penumbral region in human brain following ischemic stroke [75].

MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of 23 zinc-dependent endopeptidases capable of degrading virtually all proteins in the extracellular matrix. MMPs participate in a host of normal biological processes, including embryonic development, organ morphogenesis, nerve growth, wound healing, and angiogenesis [76-79]. Dysregulated MMPs can contribute to the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia because of their critical role in proteolytic degradation of basal lamina components (collagen IV, laminin, and fibronectin), leading to increased BBB permeability, edema and hemorrhagic transformation [80-85]. Early observations demonstrated that MMP-2 injection into the brain results in opening of the BBB with subsequent hemorrhaging around blood vessels [86] and that treatment with MMP inhibitors or MMP neutralizing antibodies reduces these effects [87] [88-90]. Further evidence that MMPs mediate BBB injury includes observations in MMP-9 knockout mice, which display a reduced infarct size and less BBB damage or hemorrhagic transformation compared to wild-type mice after focal ischemia [80, 82, 91, 92]. Involvement of MMPs in BBB disruption is also supported by clinical observations in stroke patients that display significantly higher levels of MMP-9 [93, 94]. However, recent studies suggest that MMPs may have a beneficial role in post-ischemic vascular remodeling and neurovascular repair. It has been reported that a secondary phase of elevated MMP-9 activity was observed in the peri-infarct cortical areas after mouse stroke, and this increase was closely associated with the development of angiogenesis. Inhibition of MMP-9 during this delayed upregulation resulted in malformed blood vessels, enlarged infarct volumes and cavitation, and worsened neurological deficits [95].

Thrombospondin-1

Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) is one of the potent anti-angiogenic (angiostatic) factors that have gained attention. It has been reported that this growth factor shows biphasic expression in rat [96] and mouse [45] brains after ischemia, with the first peak at one hour and the second peak at 72 hours following the onset of stroke. These studies revealed an elevated expression of TSP-1 in neurons, endothelial cells, and leptomeninges after cerebral ischemic insult. It is suggested that TSP-1 at the second peak may play a critical role in cessation of angiogenesis.

The angiopoietins and Tie receptors

The angiopoietin family consists of four members (Ang-1-4). Ang-2 promotes angiogenesis whereas Ang-1 inhibits angiogenesis [97]. A study shows that Ang-2 blocks the stabilization and maturation function of Ang-1 and loosens the contacts between endothelial cells and pericytes in the vascular wall, thus allowing it to transition to a more plastic state [15]. Both Ang-1and Ang-2 levels increased in affected brain tissue up to 28 days following an ischemic insult [98-101].

Tie-1 and Tie-2 are two receptor tyrosine kinases of angiopoietins. All four angiopoietins have been identified as ligands for Tie-2, which is selectively expressed on vascular endothelial cells. Tie-1 is expressed in ischemic lesions as early as two hours after an ischemic insult [102]. Lin and his colleagues described a biphasic expression pattern of Tie-1 and Tie-2 in rat brains following ischemia-reperfusion [98]. They also observed an up-regulation of both receptors in capillaries inside the ischemic cortex.

Other angiogenic factors

Increasing numbers of other molecules and proteins have also been identified as potential angiogenic mediators in stroke. Following cerebral ischemia, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) was increased in blood vessels of ischemic tissue [103]. Mice with a genetic deficiency of the eNOS gene showed increased brain infarction [104] and also decreased angiogenesis in the ischemic brain [105]. Placenta growth factor, another stroke-related angiogenic factor, is a ligand for VEGFR-1 that specifically potentiates the angiogenic response to VEGF by activation of VEGFR-1. Placenta growth factor mRNA and protein were both elevated in blood vessels of affected brain tissue with a peak of expression at three days after an ischemic insult [106]. Neuropilins (NP-1, NP-2) bind to VEGFR-2 [107, 108], and their mRNA expression levels were up-regulated following ischemic stroke [106, 109].

2. Angiogenesis-regulating microRNAs (AngiomiRs)

2.1 Overview of microRNAs

MiRs are small endogenous RNA molecules (~21-25 nt) that negatively regulate gene expression by hybridizing to 3′-UTRs of one or more mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner. Although the first miR, Lin-4, was identified in 1993 [110], it is only recently that we have begun to understand the scope and diversity of these regulatory molecules. MiR biogenesis and maturation require synergistic procession of a series of nuclear or cytoplasmic enzymes, including Drosha and Dicer [18, 20]. Depending on the level of complementarity between mature miR and a target sequence, mRNA can either be translationally repressed (partial) or cleaved (identical). Growing evidence has shown that miRs participate in a host of normal biological processes, including cell-cycle regulation, cell differentiation, apoptosis, development, angiogenesis, and metabolism [18, 22-24, 111, 112]. In the past few years, miRs have also been implicated in the etiology of a variety of human diseases, such as cancer, metabolic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, viral infections, and many others [28, 113-117].

2.2 microRNAs as key modulators in the development of angiogenesis

The discovery of miRs that mediate post-transcriptional silencing of specific target genes has shed light on how non-coding RNAs can play critical roles in angiogenesis [25-27]. The initial evidence showing the importance of miRs in the regulation of angiogenesis arose from several experiments using mice with a genetically manipulated Dicer gene [42, 43]. Dicer knockout mice exhibit embryonic lethality because of abnormal vascular wall structure and disarrangement. Mice with vascular-selective Dicer knockout have been reported to demonstrate a pathophysiological phenotype showing impaired angiogenic ability, such as reduced endothelial tube formation and slowed EC migration, which may have resulted from functional alteration of some key angiogenesis-related genes. Thereafter, an increasing number of individual miRs have recently been shown to regulate angiogenesis signaling pathways, thus modulating vascular endothelial migration, proliferation, and vascular-forming patterns [25-27]. In general, angiogenesis-related miRs can be classified into two groups with often opposing effects, pro-angiogenic miRs (pro-angiomiRs) and anti-angiogenic miRs (anti-angiomiRs). Several reviews have been published summarizing the literature on all angiogenesis-related miRs [25, 27]. Among them, the miR-17-92 cluster [43, 118-121], let-7 [42], miR-27b [122, 123], miR-126 [25, 124-126], miR-130a [127], miR-210 [128-130], miR-296 [131], miR-378 [132], miR-21 [133, 134], and miR-31 [133] are found to have pro-angiogenic effects; whereas miR-15/16 [135-139], miR-424 [135], miR-221/222 [140, 141], miR-92a [142], miR-320 [143], miR-200b [144], miR-217 [145], miR-503 [146, 147], miR-34 [148, 149], and miR-214 [150-152] have been thought to be anti-angiogenic (Table 1). This list is expected to expand quickly as more studies are performed. Of note, the effects of these miRs on vascular endothelial cell biology and angiogenesis have been identified in both cultured vascular endothelial cells and in cerebral ischemia-induced angiogenesis [142, 153]. Although a large number of angiogenesis-regulating microRNAs (angiomiRs) have been recognized to play a role in development, cancer and cardiovascular diseases, only a few of them have been studied in the ischemic brain.

Table 1. Identified Angiogensis-regulatory MicroRNAs (AngiomiRs).

| microRNAs | Function on Agiogenic Process | GeneTargets | Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-angiomiRs | |||

| miR-17-92 cluster | Promotes tumor angiognesis and EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo |

Tsp-1, CTGF, E2F1, TGFBR2 |

Cancer cells, HUVECs |

| let7 | Promotes EC angiogenesis in vitro | Unknown | HUVECs |

| miR-27a/b | Promotes EC angiogenesis in vitro | SEMA6A, Spry2, Dll4 |

HUVECs |

| miR-126 | Promotes EC angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo | Spred-1, PIK3R2, VCAM-1 |

Various ECs |

| miR-130a | Promotes EC angiogenesis in vitro | GAX, HOXA5 | HUVECs |

| miR-210 | Promotes EC-mediated and renal angiogenesis in vitro |

Ephrin A3, VEGF and VEGFR2 |

HUVECs |

| miR-296 | Promotes tumor angiognesis and EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo |

HGS | HBMVECs |

| miR-378 | Promotes tumor angiognesis in vitro and in vivo | SuFu, Fus-1 | Cancer cells |

| miR-21 | Induces tumor angiognesis in vitro | PTEN | Cancer cells |

| miR-31 | Promotes tumor angiognesis in vitro | Unknown | Cancer cells |

| Anti-angiomiRs | |||

| miR-15/16 | Inhibits tumor angiognesis and EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo |

FGF2, FGFR1, VEGF, VEGFR2 |

Cancer cells, HUVECs |

| miR-424 | Inhibits EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro | FGF2, FGFR1, VEGF, VEGFR2 |

HUVECs |

| miR-221/222 | Inhibits EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro | c-kit, eNOS | HUVECs |

| miR-92a | Inhibits EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo |

Integrin α5 | HUVECs |

| miR-320 | Inhibits diabetic angiogenesis in vitro | IGF-1 | ECs |

| miR-200b | Inhibits EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro | Ets-1 | HMEC |

| miR-217 | Promotes endothelial senescence | SIRT1 | HUVECs, HAECs |

| miR-503 | Inhibits EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo |

CCNE1, cdc25A | HUVECs |

| miR-34 | Inhibits endothelial and EPC angiogenesis in vitro and increased senescence |

SIRT1 | HUVECs, EPCs |

| miR-214 | Inhibits tumor angiognesis and EC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo |

HDGF, Quaking, eNOS |

Cancer cells, HUVECs |

3. Stroke-associated microRNAs and angiomiRs

MiRs are abundantly expressed in the nervous system and regulate neural development and plasticity [154]. Recently, accumulating evidence has also linked dysregulated cerebral miR expression profiles to a variety of neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease [28, 29], Parkinson’s disease [30, 31], Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [32], spinal cord injury [33], traumatic brain injury [34], and stroke [37-41]. Thus, the function and potential clinically-relevant intervention of unique miRs in these neurological disorders begins to be uncovered.

3.1 Altered microRNA profile in stroke

Recently, several groups have shown the involvement of miRs in the pathogenesis of ischemic brain injury by using miR profiling techniques in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model [38, 155]. These findings suggest several miRs as potential candidates for possible biomarkers or therapeutic targets in stroke. The first report that demonstrated the potential importance of miR dysfunction in the pathogenesis of stroke was published in 2007 [155]. The authors used miR microarray to carry out miR expression profiling in brain and blood samples from rats subjected to 24-48h reperfusion following MCA occlusion. Their data showed that approximately 106 and 82 miR transcripts were identified in the brain of MCAO rats reperfused for 24 and 48 hours, respectively. The miRs identified as highly upregulated during the ischemia reperfusion periods (24 and 48 hours) included rnomiR-292-5p, -290, 206, -210, -215, -214, -223, -298, -327, -494, and -497. Among them, miR-292-5p and miR-290 transcripts showed the highest expression after ischemic injury in the brain at 24- and 48-hour reperfusion times, respectively. Several miRs highly expressed in the ischemic brain were also detected in blood samples. Moreover, the miR profiling results with DNA microarray data further showed that the expression of AQP4, MMP9, transfelin, VSNL1 genes may be regulated by some miRs during the progression of cerebral ischemia.

Recently, Dharap et al.[38], in a provocative study on the cerebral microRNAome after stroke, employed similar miR microarray techniques to profile brain miRs in spontaneously hypertensive rats at five different reperfusion times (from 3h to 3 days) following MCA occlusion. Of the 238 miRs investigated in spontaneously hypertensive rats, 3 miRs (miR-140, miR-145, and miR-331) showed a significant increase and 5 miRs (miR 376b-5p, miR-153, miR-29c, miR-98, and miR-204) showed decreased expression at all 5 reperfusion time points studied in comparison with the sham group. These miRs may mediate inflammation, neuroprotection, receptor function, and ionic homeostasis. In addition to miR putative negative regulation of gene translation, the authors also provided evidence that several ischemia-induced miRs may bind to the promoter region of target genes and activate their transcription. Importantly, these investigators identified superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) as the direct target of miR-145 by informatics software. Infusion of antagomir-145 to the cerebral lateral ventricle resulted in increased SOD2 protein expression and decreased ischemic infarction area.

Ischemic preconditioning was also shown to alter the abundance of miR expression, including miR-132 [41], the miR-200 family, the miR-182 family [156], and others [157] that may promote ischemic tolerance and trigger neuroprotective signaling pathways.

In addition to direct involvement of miRs in the regulation of stroke progression, increasing numbers of miRs have been found to be closely associated with several risk factors of human ischemic stroke, including atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases, which may finally affect the pathogenesis of stroke. Abnormal miR expression and dysfunction in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells are thought to be responsible for carotid stenosis, resulting in the reduction of cerebral blood flow. MiR-21 [158], miR-221/222 [159], and miR-143/145 [160-163] have recently been investigated in this specific pathological process and have been shown to be critical regulators in vascular neointimal lesion formation. During atherosclerosis, formation and vulnerability of atherosclerotic plaques play a dominant role in the onset and development of ischemic stroke in humans. Abundant miR expression has been reported in carotid arteries where atherosclerotic plaques accumulate and rupture to generate thrombi that block the cerebral arteries [164-166]. For example, miR-126, miR-21, miR-221/222, and miR-143/145 have been demonstrated to contribute to the progression of atherosclerotic plaques in experimental animal models by regulating either endothelial cell function or vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via various complex molecular mechanisms [166]. Indeed, these findings are further supported by the Tampere Vascular Study demonstrating that miR-21, miR-210, miR-34a, and miR-146a/b are significantly up-regulated in human atherosclerotic plaques [167]. Importantly, another study conducted by Cipollone et al. reported significant overexpression of five specific miRs (miR-100, miR-127, miR-145, miR-133a, and miR-133b) in atherosclerotic plaques of stroke patients compared to non-stroke controls, and suggested that miRs may have an important role in regulating the evolution of atherosclerotic plaques toward instability and rupture [168]. Most of these findings have been well-summarized in several recent reviews (see reviews by Tan et al.[166], Santovito et al.[164], and Rink and Khanna [165]) and may be beyond the scope of this review article.

Hypoxia is a crucial pathogenic component of ischemic diseases and angiogenesis. Dysregulated miR profiles in cellular responses to hypoxia may also contribute to the initiation and development of post-stroke angiogenesis [169]. It has been reported that low oxygen induces a variety of hypoxia-regulating miRs, including miR-210, miR-373, miR-103, miR-24-1, miR-181c, miR-26b, and miR-26a-2 [170-173]. In particular, miR-210, the most extensively investigated miR, is specifically sensitive to hypoxic stimuli and has been considered as a master miR of hypoxic response. MiR-210 has been demonstrated to be induced by hypoxia in almost all cells and tissues tested to date [174]. The induction of miR-210 is hypoxia-specific and enhanced by several classical hypoxia-related transcription factors, such as HIF-1α in a transcriptional manner (transactivation) [171, 172]. It is worth noting that the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke is very complex and not limited only to hypoxia. Thus, the altered miR profiles may be different between these two pathological processes.

3.2 Potential functions of stroke-associated microRNAs

3.2.1 Biomarker for stroke diagnosis and outcomes

MiRs have been recently reported as potential biomarkers in stroke. Altered miR levels were found in blood samples directly from rodent stroke models [37, 175-177]. Several highly dysregulated miRs in ischemic rat brains were detected in blood samples [37]. A total of 10 miRs were found to be present in both the blood and brain at both reperfusion times (24 and 48 hours). MiR-290 was observed to be highly upregulated, whereas let-7i was downregulated. In addition, rat models of cerebral ischemia, cerebral hemorrhage, and kainate-induced seizures also showed changes in the expression of miRs in the hippocampus and blood samples, many of which changed significantly in both tissues in comparison with the sham controls [176]. One study from a Japanese group also reported that miR-124 is a brain-specific miR and plasma miR-124 levels were significantly increased at 6h, and remained elevated at 48 h after rat MCAO [37, 175-177].

Consistent with experimental data in rats, peripheral blood isolated directly from young stroke patients (18-49 years) also revealed differential expression of miR profiles, implicating them as potential biomarkers for identifying stroke subtypes or predicting therapeutic outcomes in stroke. For example, 157 of the 836 miRs present on the array chip have been found to be differentially regulated across stroke samples and subtypes, with 138 miRs highly upregulated and 19 miRs downregulated. Among them, 17 miRs (hsa-let-7e, miR-1184, -1246, -1261, -1275, -1285, -1290, -181a, -25*, -513a-5p, -550, -602, -665, -891a, -933, -939, -923) can also be identified as highly expressed in the stroke subtypes, including large artery strokes, small artery strokes, cardioembolic strokes and undetermined causes, whereas 8 miRs (hsa-let-7f, miR-126, -1259, -142-3p, -15b, -186, -519e, -768-5p) are poorly expressed across these stroke subtypes. Moreover, miR-103 and miR-29a, -b, -c increase significantly and are associated with poor outcomes in both large artery and cardioembolic stroke subtypes. These miRs are widely implicated in vascular endothelial cell and vascular function, erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, neural function, and hypoxia, and altered miRs were detectable even several months after the onset of stroke [178].

Similarly, another study also revealed that circulatory miR-145 expression is significantly enhanced in ischemic stroke patients in comparison with the healthy control subjects, implying that circulating miR-145 may be a suitable biomarker for ischemic stroke [179]. Furthermore, miR-210, a master hypoxia-inducing miR, has also been evaluated for the correlation of blood miR-210 levels with stroke severity and clinical outcome in acute ischemic stroke. Compared to healthy controls, miR-210 was significantly decreased in stroke patients at 7 and 14 days after stroke onset. MiR-210 levels in stroke patients with good outcomes were significantly higher than patients with poor outcomes. There is a positive correlation between blood and brain miR-210 in ischemic mice [180]. Thus, it is promising that peripheral blood miRs and their profiles can be utilized as biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of acute cerebral ischemic stroke.

3.2.2 Modulating signaling cascades to regulate stroke pathology: the function of individual microRNAs in stroke

Most recently, the functions of several individual miRs have also been identified in post-ischemic pathology from several investigative groups, including our laboratory (Table 2). For example, a recent study showed that miR-145 is upregulated and responsible for translational inhibition of superoxide dismutase-2 in the hypertensive rat brain after stroke [38]. Inhibition of miR-145 in vivo is able to reduce cerebral infarction. Also, we have recently defined that miR-497 is induced and promotes ischemic neuronal death in vitro and in vivo by directly inhibiting anti-apoptotic genes, bcl-2 and bcl-w [40]. Moreover, we are the first to document that the expression of miR-15a is significantly increased in cerebral vascular endothelial cell (CEC) cultures after ischemic insults and that miR-15a plays a causative role in the regulation of apoptosis by directly targeting bcl-2 in ischemic vascular injury in vitro. The inhibition of this effect is also shown to contribute to the PPARδ-mediated vasoprotective role in mouse stroke [39]. On the other hand, miR-320a [181] and miR-21 [182] were demonstrated to protect neurons from ischemic death by targeting water channel modulators, aquaporins and the Fas ligand gene, respectively. Several other studies from different groups also documented that direct modulation of miR-23a [183], miR-181 [184], miR-29b [185], and Let7f [186] can provide neuroprotective roles in rodent experimental stroke models. Accordingly, miRs such as miR-331 and miR-885-3p [187], miR-146a [188], and miR-199a-5p [189] can also mediate valproic acid, VELCADE-tissue plasminogen activator combination therapy, Vitamin E-mediated neuroprotection or improvements in neurological deficits, and motor performance in rodent stroke models. Interestingly, stroke is also able to alter miR expression in neural progenitor cells of the subventricular zone (SVZ) and in particular, miR-124a mediates stroke-induced neurogenesis by targeting the JAG-Notch signaling pathway [190]. Taken together, these findings support and highlight the importance of miRs in the pathogenesis of stroke [165, 166, 191, 192].

Table 2. Identified Stroke-Associated MicroRNAs.

| microRNAs | Function | Targets | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-145 | Antagomir-145 decreases brain infarction. | SOD-2 | Dharap A et al.,2009 [38] |

| miR-497 | Antagomir-497 attenuates ischemic brain infarction, and improves neurological outcomes. |

Bcl-2, Bcl-w | Yin KJ et al, 2010a [40] |

| miR-15a | Inhibition results in cerebral vascular protection in vitro and in vivo. |

Bcl-2 | Yin KJ et al., 2010b [39] |

| miR-132 | Decreased miR-132 expression correlates with increased MeCP2 protein. |

MeCP2 | Lusardi TA et al., 2010 [41] |

| miR-21 | Overexpression protects neurons from ischemic death in vitro. |

FASLG | Buller B et al., 2010 [182] |

| miR-320a | Antagomir-320a reduces brain infarct volume. | AQP1, AQP4 | Sepramaniam S et al., 2010 [182] |

| miR-200 family |

Overexpression results in neuroprotection in in vitro ischemia. |

PHD2 | Lee ST et al., 2010 [156] |

| miR-124a | Inhibition reduces progenitor cell proliferation and promots neuronal differentiation in vitro. |

Jag1/Notch/p27K ip1 |

Liu XS et al., 2011 [190] |

| miR-23a | Sex difference in miR-23a regulates XIAP in ischemic cell death. |

XIAP | Siegel C et al., 2011 [183] |

| miR-29b | Upregulation promotes neuronal cell death in vitro. |

Bcl2L2 | Shi G et al., 2011 [185] |

| miR-181 | Knockdown provides protection against ischemia- induced brain cell death in vitro and in vivo. |

GRP78 | Ouyang YB et al., 2011 [184] |

| miR-210 | Biomarker, the higher miR-210 level, the better stroke outcome in patients. |

Unknown | Zeng L et al., 2011 [180] |

| miR-124 | Biomaker, increases in plasm in rat following MCAO |

Unknown | Weng H et al., 2011 [177] |

| Let7f | Antagomir to let7f promotes neuroprotection in rat ischemic stroke model. |

IGF-1 | Selvamani A et al., 2012 [186] |

| miR-145 | Biomarker, circulatory microRNA-145 expression is significantly higher in ischemic stroke patients. |

Unknown | Gan CS et al., 2012 [179] |

| miR-199a-5p | Mediates the neuroprotection of vitamin E α- Tocotrienol against focal cerebral ischemia |

MRP1 | Park HA et al., 2011 [189] |

| miR-146a | Mediates the neuroprotection of VELCADE and tPA in aged rat MCAO medel |

IRAK1 | Zhang L et al., 2012 [188] |

| miR-331, miR-885-3p |

Mediates the neuroprotection of valproic acid in rat MCAO medel |

Multiple targets | Hunsberger JG et al., 2012 [187] |

3.3 AngiomiRs in stroke pathologies

Emerging evidence shows that miRs may be involved in the regulation of post-ischemic angiogenesis after stroke (Table 3). In young stroke patients, circulating miRs in blood that are associated with vascular endothelial function and angiogenesis (hsa-let-7f, miR-130a, -150, -17, -19a, -19b, -20a, -222 and -378) and vascular remodeling (miR-21, -126, -150) have been found to be differentially regulated under ischemic conditions. Similarly, miRs that are expressed in hypoxic conditions (miR-23, -24, -26, -103, -107, -181) and cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (miR-15, -16, -21, -23a, -29, -30a, -150 and -195) have also been detected in blood samples from stroke patients [178]. Moreover, miR-320, which is a negative angiogenic mediator in myocardial microvascular endothelial cells of type 2 diabetic rats, is significantly reduced in all stroke patients, especially those with good outcome [178].

Table 3. Stroke-Associated AngiomiRs.

| microRNAs | Function in Angiogenesis | Targets | Cell types |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-320 | Blood miR-320 level is significantly downregulated in all young stroke patients with good outcome. |

Unknown | Blood | Tan KS et al., 2009 [178] |

| miR-15a | Upregulates in ischemic brain regions. Gain or loss-of-miR-15a function reduces or increases EC tube formation, migration, and differentiation, respectively. EC-miR-15a transgenic overexpression leads to reduced blood vessel formation and local blood flow perfusion after hindlimb ischemia. |

FGF2, VEGF |

CECs, HUVECs |

Yin KJ et al., 2010b [39]; Yin KJ et al., 2012 [136] |

| miR-210 | Upregulates in rat ischemic brain cortexes. Overexpression increases Notch1 expression and induces ECs to migrate and form capillary-like structures on Matrigel. |

Notch1 | HUVECs | Lou YL et al., 2012 [193] |

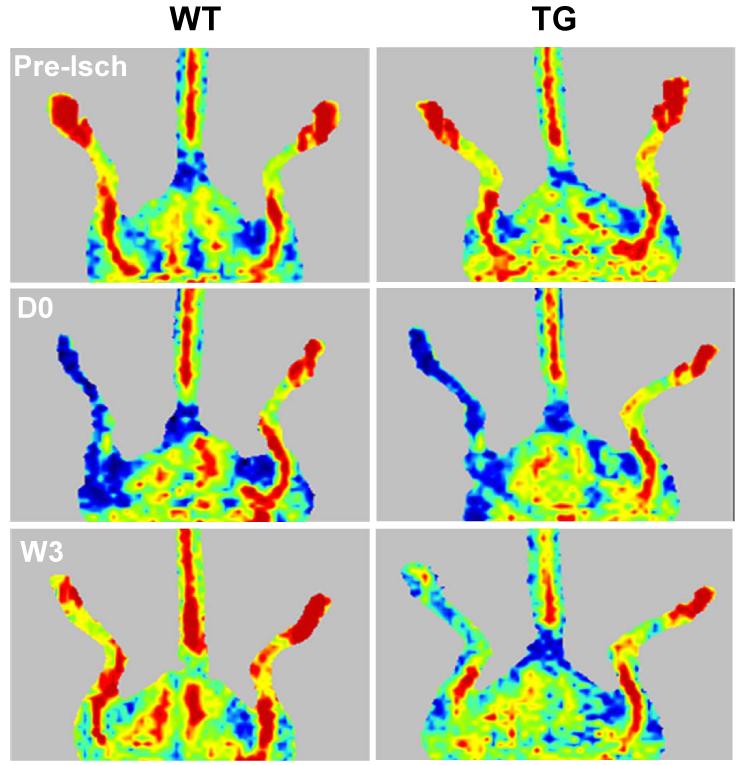

Consistent with clinical observations, we recently documented the effects and potential mechanisms of vascular endothelial cell (EC)-enriched miR-15a, a stroke-associated miR, on angiogenesis after ischemic insults [136]. We have shown a novel finding that EC-selective miR-15a transgenic overexpression leads to reduced blood vessel formation and local blood flow perfusion in mouse hindlimbs at 1-3 weeks after hindlimb ischemia (Figure 1). Mechanistically, gain- or loss-of-miR-15a function by lentiviral infection in ECs significantly reduces or increases tube formation, cell migration and cell differentiation, respectively. By FGF2 and VEGF 3′UTR luciferase reporter assays, real-time PCR, and immunoassays, we further identified that miR-15a directly targets FGF2 and VEGF to facilitate its anti-angiogenic effects. Our data suggest that miR-15a in ECs can significantly suppress cell-autonomous angiogenesis through direct inhibition of endogenous endothelial FGF2 and VEGF activities [136]. Moreover, we further investigated the role of miR-15a in the regulation of post-brain ischemic angiogenesis (unpublished data). We have shown that expression of the miR-15a is significantly increased in the cerebral vasculature at the penumbral area 7 days after mouse middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Accordingly, endothelial cell (EC)-selective miR-15a transgenic overexpression leads to reduced cerebral blood vessel formation, increased brain infarction and neurological deficits in mice 7 days post-MCA occlusion. These findings may suggest miR-15a can suppress post-ischemic cerebral angiogenesis. Pharmacological modulation of miR-15a function may provide a new therapeutic strategy to intervene against angiogenesis with potential promise for further development of neurorestorative therapies after ischemic stroke.

Figure 1.

miR-15a attenuates angiogenesis and local blood flow recovery after mouse hindlimb ischemia [136]. miR-15a transgenic (TG) mice and littermate wild-type controls (WT) were subjected to femoral artery ligation and subsequently monitored by laser Doppler perfusion imaging at 0 day (D0) and 3 weeks (W3) after hindlimb ischemia (n=8 per group).

In addition, another group has recently found that miR-210, a hypoxia-induced miR, is significantly up-regulated in adult rat ischemic brain cortexes in which the expression of Notch1 signaling was also increased. Gain-of-miR-210 function in cultured HUVE-12 cells caused activation of the Notch1 signaling cascade and induced endothelial cells to migrate and form capillary-like structures. These data may imply that miR-210 mediates angiogenesis following cerebral ischemia [193].

4. AngiomiR-based therapeutics in cardiovascular diseases and stroke

Greater attention has been paid to angiomiRs as key regulators of angiogenesis as well as novel treatments for cancer, limb ischemic injury, retinopathy, cardiovascular diseases, and stroke [25, 27, 194]. The use of angiomiR mimics and angiomiR inhibitors are two therapeutic approaches to promoting and inhibiting angiogenesis. The use of these strategies depends on the requirements of upregulating or downregulating target angiomiRs to inhibit or enhance the angiogenic process according to the pathological angiogenic status of relevant diseases. In ischemic diseases with insufficient angiogenesis such as myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and peripheral artery diseases, pro-angiomiR mimics or anti-angiomiR inhibitors can be used to promote angiogenesis for a better beneficial outcome. Conversely, pro-angiomiR inhibitors or anti-angiomiR mimics may be applied to reduce excessive neovascularization in tumor angiogenesis and retinopathy [25, 27, 194].

Generally, angiomiR mimics are basically designed as double-stranded oligonucleotides that resemble miR precursors. Depending on the delivery system, overexpression of an angiomiR mimic can be achieved by lipid-mediated transfection, adenoviral or lentiviral vectors, or transgenesis. For example, miR-126 mimics might be utilized to enhance neoangiogenesis after myocardial infarction or ischemia [153]. MiR-15 and -16 mimics might be a useful anti-tumor tool that blocks angiogenesis, resulting in the inhibition of tumor cell growth and proliferation [26, 42].

AngiomiR inhibitors are originally designed as single-stranded angiomiR antisense oligonucleotides that bind to the full or partial complementary reverse sequence of a mature miR. The use of antisense sequences has been successful in various cultured cell systems. However, for use in vivo, several different chemical modifications have been developed to improve their pharmacokinetic characteristics in vivo [195, 196]. These modifications include the initial antagomiRs in which anti-miR oligonucleotides are synthesized and further modified by incorporations of a methyl group (2′-O-methyl [2′-O-Me]) together with the partial phosphorothioate linkage and cholesterol conjugation at the 3′ end of the strand (which improves tissue distribution and cellular uptake), alterations to the sugar moiety with 2′-O-methoxyethyl phosphorothioate (2′-MOE) and the use of locked nucleic acids (LNAs). Studies have revealed that inhibition of miR-17-92 cluster activity is associated with angiogenesis [118, 197]. Systemic administration of antagomirs has been used to silence miR-122 in the liver of mice [198] and miR-133 in mouse heart [113]. In addition, anti-miR-122 LNA has been used to treat chronic viral hepatitis in chimpanzees [199]. Several companies are now developing miR-based therapeutics. Santaris Pharmaceuticals (http://www.santaris.com) has launched a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of hepatitis C using liver-specific anti-miR-122 LNA. Most recently, angiomiR inhibitor technology has been used for miR-15 inhibition in ischemic heart disease [200]. Also, anti-miR-15/195, miR-92, and miR-143/145 LNA preclinical studies are ongoing at miRagen Therapeutics (http://www.miragentherapeutics.com) to develop anti-miR inhibitors for the improvement of post-myocardial infarction remodeling and treatment of peripheral artery disease and vascular disease. In terms of ischemic stroke studies, our laboratory, together with other groups, has also shown that local delivery of antagomiR-497 [40], or antagomiR-145 [38] by intracerebroventricular injection provides a significant neuroprotective role in rodent experimental stroke models. However, there is no direct experimental evidence to show that angiomiR therapeutics reduces brain infarct volume or improves functional outcomes after stroke.

5. Future prospects

Recent miR-based therapeutic angiogenesis through direct injection or viral gene transfer of angiomiRs has shown us several promising results in reducing myocardial infarction or promoting new vessel growth and blood flow recovery in peripheral vascular diseases. These encouraging trials should prompt us to apply similar approaches to the treatment of ischemic stroke. Although selective regulation of particular angiomiRs appears to be a promising restorative therapy for ischemic stroke, there are several potential challenges or limitations for application of miR and angiomiR therapeutics in stroke. These obstacles include a lack of understanding the function of individual angiomiRs in stroke pathogenesis, a less than effective delivery system to achieve neural cell specific delivery in vivo, limitations pertaining to miR target specificity, and the unique structure of the blood-brain barrier. For systemic delivery of virus-based angiomiR mimics and inhibitors, potential pitfalls such as virus-derived toxicity and off-target effects may also hinder their future translational application in human studies. Moreover, in addition to the beneficial outcomes of angiogenesis in the restorative treatment of ischemic stroke, angiogenesis-derived negative effects should also be carefully taken into account. For example, essential attention should be paid to tumor cells growth-promoting roles when thinking about systemically modifying miR expression with antagomiRs and/or angiomiRs, especially in patients suffering from ischemic stroke with comorbid cancers.

Accumulating evidence has linked dysregulated cerebral miR expression to a variety of neurological diseases. Much hope has been laid on these tiny non-coding RNA molecules as novel pharmaceutical targets in many fields, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. However, we should realize that we are still at the early stages in miR or angiomiR-based therapy in the stroke research field. Future studies will focus on elucidating the in vivo functions of angiomiR members after focal cerebral ischemia. In particular, utilization of general or cell-specific angiomiR transgenic and knockout animals will be necessary to validate the particular functional significance and molecular mechanisms of individual angiomiRs in the pathogenesis of stroke. Moreover, the molecular regulatory network of particular angiomiRs may also need to be elucidated to fully understand the function of angiomiRs. Specific attention will also be paid to miR target identification and cell-type specificity of miRs. Also, non-toxic angiomiR modulators and better local delivery methods need to be developed or optimized to avoid the side effects and lower specificity caused by the systemic administration of virus-based angiomiR mimics and inhibitors. In the meantime, employing nanoparticle-packaged angiomiR mimics or inhibitors will be needed to overcome barriers such as BBB damage and brain edema after the onset of stroke. In addition, since a number of angiomiRs may be associated with post-ischemic angiogenesis, a whole family of miRs and/or multiple miRs will likely need to be silenced for effective angiomiR therapeutics. Toward this goal, tiny LNA-substituted phosphorothioate anti-miR oligonucleotides complementary to seed sequences [201] and miR sponges [202] will be used to antagonize all the respective miR family members or multiple miR targets, respectively. These studies will contribute to emerging efforts for angiomiR therapeutics in stroke, and may lead us to uncover new insights for further development of neurorestorative therapies after ischemic stroke.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health (NS066652, and HL089544). K.J.Y. is supported by the American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grants 0630209N. Y.E.C. is an AHA established investigator (0840025N).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- [1].Schellinger PD, Kaste M, Hacke W. An update on thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004 Feb;17(1):69–77. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200402000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schellinger PD, Warach S. Therapeutic time window of thrombolytic therapy following stroke. Current atherosclerosis reports. 2004 Jul;6(4):288–94. doi: 10.1007/s11883-004-0060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stapf C, Mohr JP. Ischemic stroke therapy. Annual review of medicine. 2002;53:453–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barone FC. Ischemic stroke intervention requires mixed cellular protection of the penumbra. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009 Mar;10(3):220–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].del Zoppo GJ. Stroke and neurovascular protection. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Feb 9;354(6):553–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ginsberg MD. Current status of neuroprotection for cerebral ischemia: synoptic overview. Stroke. 2009 Mar;40(3 Suppl):S111–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lo EH, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003 May;4(5):399–415. doi: 10.1038/nrn1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lok J, Gupta P, Guo S, et al. Cell-cell signaling in the neurovascular unit. Neurochem Res. 2007 Dec;32(12):2032–45. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yuan J. Neuroprotective strategies targeting apoptotic and necrotic cell death for stroke. Apoptosis. 2009 Apr;14(4):469–77. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0304-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004 May;5(5):347–60. doi: 10.1038/nrn1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008 Jan 24;57(2):178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med. 1995 Jan;1(1):27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005 Dec 15;438(7070):932–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hayashi T, Deguchi K, Nagotani S, et al. Cerebral ischemia and angiogenesis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006 May;3(2):119–29. doi: 10.2174/156720206776875902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Beck H, Plate KH. Angiogenesis after cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 2009 May;117(5):481–96. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Arai K, Jin G, Navaratna D, Lo EH. Brain angiogenesis in developmental and pathological processes: neurovascular injury and angiogenic recovery after stroke. FEBS J. 2009 Sep;276(17):4644–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Neurorestorative therapies for stroke: underlying mechanisms and translation to the clinic. Lancet Neurol. 2009 May;8(5):491–500. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004 Jan 23;116(2):281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009 Jan 23;136(2):215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim VN. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005 May;6(5):376–85. doi: 10.1038/nrm1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bartel DP, Chen CZ. Micromanagers of gene expression: the potentially widespread influence of metazoan microRNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2004 May;5(5):396–400. doi: 10.1038/nrg1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, Sijen T, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2001 Oct 15;15(20):2654–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, et al. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004 Oct 13;23(20):4051–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wienholds E, Plasterk RH. MicroRNA function in animal development. FEBS Lett. 2005 Oct 31;579(26):5911–22. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang S, Olson EN. AngiomiRs--key regulators of angiogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009 Jun;19(3):205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Targeting microRNA expression to regulate angiogenesis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008 Jan;29(1):12–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Suarez Y, Sessa WC. MicroRNAs as novel regulators of angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2009 Feb 27;104(4):442–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hebert SS, Horre K, Nicolai L, et al. MicroRNA regulation of Alzheimer’s Amyloid precursor protein expression. Neurobiol Dis. 2009 Mar;33(3):422–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hebert SS, Horre K, Nicolai L, et al. Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Apr 29;105(17):6415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710263105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kim J, Inoue K, Ishii J, et al. A MicroRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science (New York, NY. 2007 Aug 31;317(5842):1220–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1140481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang G, van der Walt JM, Mayhew G, et al. Variation in the miRNA-433 binding site of FGF20 confers risk for Parkinson disease by overexpression of alpha-synuclein. Am J Hum Genet. 2008 Feb;82(2):283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Williams AH, Valdez G, Moresi V, et al. MicroRNA-206 delays ALS progression and promotes regeneration of neuromuscular synapses in mice. Science (New York, NY. 2009 Dec 11;326(5959):1549–54. doi: 10.1126/science.1181046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Liu NK, Wang XF, Lu QB, Xu XM. Altered microRNA expression following traumatic spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2009 Oct;219(2):424–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Redell JB, Liu Y, Dash PK. Traumatic brain injury alters expression of hippocampal microRNAs: potential regulators of multiple pathophysiological processes. J Neurosci Res. 2009 May 1;87(6):1435–48. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nicoloso MS, Calin GA. MicroRNA involvement in brain tumors: from bench to bedside. Brain Pathol. 2008 Jan;18(1):122–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Beveridge NJ, Tooney PA, Carroll AP, et al. Dysregulation of miRNA 181b in the temporal cortex in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 Apr 15;17(8):1156–68. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jeyaseelan K, Lim KY, Armugam A. MicroRNA expression in the blood and brain of rats subjected to transient focal ischemia by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2008 Mar;39(3):959–66. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dharap A, Bowen K, Place R, Li LC, Vemuganti R. Transient focal ischemia induces extensive temporal changes in rat cerebral microRNAome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009 Apr;29(4):675–87. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yin KJ, Deng Z, Hamblin M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta regulation of miR-15a in ischemia-induced cerebral vascular endothelial injury. J Neurosci. 2010 May 5;30(18):6398–408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0780-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yin KJ, Deng Z, Huang H, et al. miR-497 regulates neuronal death in mouse brain after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2010 Apr;38(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lusardi TA, Farr CD, Faulkner CL, et al. Ischemic preconditioning regulates expression of microRNAs and a predicted target, MeCP2, in mouse cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Apr;30(4):744–56. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of Dicer and Drosha for endothelial microRNA expression and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007 Jul 6;101(1):59–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C, Yu J, et al. Dicer-dependent endothelial microRNAs are necessary for postnatal angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Sep 16;105(37):14082–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804597105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Beck H, Acker T, Wiessner C, Allegrini PR, Plate KH. Expression of angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, and tie receptors after middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Am J Pathol. 2000 Nov;157(5):1473–83. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64786-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hayashi T, Noshita N, Sugawara T, Chan PH. Temporal profile of angiogenesis and expression of related genes in the brain after ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003 Feb;23(2):166–80. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000041283.53351.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Marti HJ, Bernaudin M, Bellail A, et al. Hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression precedes neovascularization after cerebral ischemia. Am J Pathol. 2000 Mar;156(3):965–76. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64964-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM. Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1994 Sep;25(9):1794–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.9.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM. Some remarks on the growth-rate and angiogenesis of microvessels in ischemic stroke. Morphometric and immunocytochemical studies. Patol Pol. 1993;44(4):203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lennmyr F, Ata KA, Funa K, Olsson Y, Terent A. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors (Flt-1 and Flk-1) following permanent and transient occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in the rat. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 1998 Sep;57(9):874–82. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Issa R, Krupinski J, Bujny T, Kumar S, Kaluza J, Kumar P. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR, in human brain tissue after ischemic stroke. Lab Invest. 1999 Apr;79(4):417–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kovacs Z, Ikezaki K, Samoto K, Inamura T, Fukui M. VEGF and flt. Expression time kinetics in rat brain infarct. Stroke. 1996 Oct;27(10):1865–72. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1865. discussion 72-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Greenberg DA, Jin K. From angiogenesis to neuropathology. Nature. 2005 Dec 15;438(7070):954–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hayashi T, Abe K, Suzuki H, Itoyama Y. Rapid induction of vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke. 1997 Oct;28(10):2039–44. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.10.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Plate KH, Beck H, Danner S, Allegrini PR, Wiessner C. Cell type specific upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in an MCA-occlusion model of cerebral infarct. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 1999 Jun;58(6):654–66. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Jiang Q, et al. VEGF enhances angiogenesis and promotes blood-brain barrier leakage in the ischemic brain. J Clin Invest. 2000 Oct;106(7):829–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI9369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sun Y, Jin K, Xie L, et al. VEGF-induced neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J Clin Invest. 2003 Jun;111(12):1843–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI17977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wang Y, Kilic E, Kilic U, et al. VEGF overexpression induces post-ischaemic neuroprotection, but facilitates haemodynamic steal phenomena. Brain. 2005 Jan;128(Pt 1):52–63. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Cobbs CS, Chen J, Greenberg DA, Graham SH. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1998 Jun 19;249(2-3):79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lee MY, Ju WK, Cha JH, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA following transient forebrain ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1999 Apr 16;265(2):107–10. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gunsilius E, Petzer AL, Stockhammer G, Kahler CM, Gastl G. Serial measurement of vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 in serum of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2001 Jan;32(1):275–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.275-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Slevin M, Krupinski J, Slowik A, Kumar P, Szczudlik A, Gaffney J. Serial measurement of vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 in serum of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2000 Aug;31(8):1863–70. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lin TN, Te J, Lee M, Sun GY, Hsu CY. Induction of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) expression following focal cerebral ischemia. Brain research. 1997 Oct 3;49(1-2):255–65. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Chen HH, Chien CH, Liu HM. Correlation between angiogenesis and basic fibroblast growth factor expression in experimental brain infarct. Stroke. 1994 Aug;25(8):1651–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.8.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Issa R, AlQteishat A, Mitsios N, et al. Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor mRNA and protein in the human brain following ischaemic stroke. Angiogenesis. 2005;8(1):53–62. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-5613-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Iihara K, Sasahara M, Hashimoto N, Hazama F. Induction of platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor in focal ischemia of rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996 Sep;16(5):941–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Iihara K, Sasahara M, Hashimoto N, Uemura Y, Kikuchi H, Hazama F. Ischemia induces the expression of the platelet-derived growth factor-B chain in neurons and brain macrophages in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994 Sep;14(5):818–24. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kawabe T, Wen TC, Matsuda S, Ishihara K, Otsuda H, Sakanaka M. Platelet-derived growth factor prevents ischemia-induced neuronal injuries in vivo. Neurosci Res. 1997 Dec;29(4):335–43. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Renner O, Tsimpas A, Kostin S, et al. Time- and cell type-specific induction of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta during cerebral ischemia. Brain research. 2003 May 12;113(1-2):44–51. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Massague J. The transforming growth factor-beta family. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:597–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, et al. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jun;83(12):4167–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Yang EY, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor beta 1-induced changes in cell migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis in the chicken chorioallantoic membrane. J Cell Biol. 1990 Aug;111(2):731–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wiessner C, Gehrmann J, Lindholm D, Topper R, Kreutzberg GW, Hossmann KA. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and interleukin-1 beta mRNA in rat brain following transient forebrain ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;86(5):439–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00228578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Yamashita K, Gerken U, Vogel P, Hossmann K, Wiessner C. Biphasic expression of TGF-beta1 mRNA in the rat brain following permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. Brain Res. 1999 Jul 31;836(1-2):139–45. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Haqqani AS, Nesic M, Preston E, Baumann E, Kelly J, Stanimirovic D. Characterization of vascular protein expression patterns in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion using laser capture microdissection and ICAT-nanoLC-MS/MS. Faseb J. 2005 Nov;19(13):1809–21. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3793com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Krupinski J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Kaluza J. Increased expression of TGF-beta 1 in brain tissue after ischemic stroke in humans. Stroke. 1996 May;27(5):852–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.5.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Yong VW, Power C, Forsyth P, Edwards DR. Metalloproteinases in biology and pathology of the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001 Jul;2(7):502–11. doi: 10.1038/35081571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Baker AH, Edwards DR, Murphy G. Metalloproteinase inhibitors: biological actions and therapeutic opportunities. Journal of cell science. 2002 Oct 1;115(Pt 19):3719–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function, and biochemistry. Circ Res. 2003 May 2;92(8):827–39. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070112.80711.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Asahi M, Asahi K, Jung JC, del Zoppo GJ, Fini ME, Lo EH. Role for matrix metalloproteinase 9 after focal cerebral ischemia: effects of gene knockout and enzyme inhibition with BB-94. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000 Dec;20(12):1681–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Asahi M, Sumii T, Fini ME, Itohara S, Lo EH. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 gene knockout has no effect on acute brain injury after focal ischemia. Neuroreport. 2001 Sep 17;12(13):3003–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200109170-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Asahi M, Wang X, Mori T, et al. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on the proteolysis of blood-brain barrier and white matter components after cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2001 Oct 1;21(19):7724–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07724.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Hamann GF, Okada Y, Fitridge R, del Zoppo GJ. Microvascular basal lamina antigens disappear during cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Stroke. 1995 Nov;26(11):2120–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Hamann GF, Okada Y, Zoppo GJ. Hemorrhagic transformation and microvascular integrity during focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996 Nov;16(6):1373–8. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Hamann GF, Liebetrau M, Martens H, et al. Microvascular basal lamina injury after experimental focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002 May;22(5):526–33. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Rosenberg GA, Kornfeld M, Estrada E, Kelley RO, Liotta LA, Stetler-Stevenson WG. TIMP-2 reduces proteolytic opening of blood-brain barrier by type IV collagenase. Brain Res. 1992 Apr 3;576(2):203–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases in brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 1995 Oct;12(5):833–42. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Mun-Bryce S, Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases in cerebrovascular disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998 Nov;18(11):1163–72. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Mun-Bryce S, Rosenberg GA. Gelatinase B modulates selective opening of the blood-brain barrier during inflammation. Am J Physiol. 1998 May;274(5 Pt 2):R1203–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.5.R1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Rosenberg GA, Estrada EY, Dencoff JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs are associated with blood-brain barrier opening after reperfusion in rat brain. Stroke. 1998 Oct;29(10):2189–95. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Lapchak PA, Chapman DF, Zivin JA. Metalloproteinase inhibition reduces thrombolytic (tissue plasminogen activator)-induced hemorrhage after thromboembolic stroke. Stroke. 2000 Dec;31(12):3034–40. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Sumii T, Lo EH. Involvement of matrix metalloproteinase in thrombolysis-associated hemorrhagic transformation after embolic focal ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2002 Mar;33(3):831–6. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.104542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Montaner J, Alvarez-Sabin J, Molina CA, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase expression is related to hemorrhagic transformation after cardioembolic stroke. Stroke. 2001 Dec 1;32(12):2762–7. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.99512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Montaner J, Molina CA, Monasterio J, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 pretreatment level predicts intracranial hemorrhagic complications after thrombolysis in human stroke. Circulation. 2003 Feb 4;107(4):598–603. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046451.38849.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Zhao BQ, Wang S, Kim HY, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed cortical responses after stroke. Nat Med. 2006 Apr;12(4):441–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Lin TN, Kim GM, Chen JJ, Cheung WM, He YY, Hsu CY. Differential regulation of thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-2 after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Stroke. 2003 Jan;34(1):177–86. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000047100.84604.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Gale NW, Thurston G, Hackett SF, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is required for postnatal angiogenesis and lymphatic patterning, and only the latter role is rescued by Angiopoietin-1. Dev Cell. 2002 Sep;3(3):411–23. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Lin TN, Wang CK, Cheung WM, Hsu CY. Induction of angiopoietin and Tie receptor mRNA expression after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000 Feb;20(2):387–95. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Zhang Z, Chopp M. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietins in focal cerebral ischemia. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2002 Feb;12(2):62–6. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Jiang Q, Chopp M. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells participate in cerebral neovascularization after focal cerebral ischemia in the adult mouse. Circ Res. 2002 Feb 22;90(3):284–8. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Tsang W, et al. Correlation of VEGF and angiopoietin expression with disruption of blood-brain barrier and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002 Apr;22(4):379–92. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Zhang ZG, Chopp M, Lu D, Wayne T, Zhang RL, Morris D. Receptor tyrosine kinase tie 1 mRNA is upregulated on cerebral microvessels after embolic middle cerebral artery occlusion in rat. Brain Res. 1999 Nov 20;847(2):338–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Veltkamp R, Rajapakse N, Robins G, Puskar M, Shimizu K, Busija D. Transient focal ischemia increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase in cerebral blood vessels. Stroke. 2002 Nov;33(11):2704–10. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000033132.85123.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Huang Z, Huang PL, Ma J, et al. Enlarged infarcts in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice are attenuated by nitro-L-arginine. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996 Sep;16(5):981–7. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Chen J, Zacharek A, Zhang C, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and neurogenesis after stroke in mice. J Neurosci. 2005 Mar 2;25(9):2366–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5071-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Beck H, Acker T, Puschel AW, Fujisawa H, Carmeliet P, Plate KH. Cell type-specific expression of neuropilins in an MCA-occlusion model in mice suggests a potential role in post-ischemic brain remodeling. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2002 Apr;61(4):339–50. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Soker S, Miao HQ, Nomi M, Takashima S, Klagsbrun M. VEGF165 mediates formation of complexes containing VEGFR-2 and neuropilin-1 that enhance VEGF165-receptor binding. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85(2):357–68. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. Interactions of VEGF isoforms with VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and neuropilin in vivo: a computational model of human skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology. 2007 Jan;292(1):H459–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00637.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Zhang ZG, Tsang W, Zhang L, Powers C, Chopp M. Up-regulation of neuropilin-1 in neovasculature after focal cerebral ischemia in the adult rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001 May;21(5):541–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993 Dec 3;75(5):843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004 Sep 16;431(7006):350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Wienholds E, Kloosterman WP, Miska E, et al. MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science (New York, NY. 2005 Jul 8;309(5732):310–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1114519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, et al. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007 May;13(5):613–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Krutzfeldt J, Stoffel M. MicroRNAs: a new class of regulatory genes affecting metabolism. Cell Metab. 2006 Jul;4(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Sullivan CS, Ganem D. MicroRNAs and viral infection. Molecular cell. 2005 Oct 7;20(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Sullivan CS, Grundhoff AT, Tevethia S, Pipas JM, Ganem D. SV40-encoded microRNAs regulate viral gene expression and reduce susceptibility to cytotoxic T cells. Nature. 2005 Jun 2;435(7042):682–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Wiemer EA. The role of microRNAs in cancer: no small matter. Eur J Cancer. 2007 Jul;43(10):1529–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, et al. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat Genet. 2006 Sep;38(9):1060–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]