Abstract

We expanded the knowledge base for Drosophila cell line transcriptomes by deeply sequencing their small RNAs. In total, we analyzed more than 1 billion raw reads from 53 libraries across 25 cell lines. We verify reproducibility of biological replicate data sets, determine common and distinct aspects of miRNA expression across cell lines, and infer the global impact of miRNAs on cell line transcriptomes. We next characterize their commonalities and differences in endo-siRNA populations. Interestingly, most cell lines exhibit enhanced TE-siRNA production relative to tissues, suggesting this as a common aspect of cell immortalization. We also broadly extend annotations of cis-NAT-siRNA loci, identifying ones with common expression across diverse cells and tissues, as well as cell-restricted loci. Finally, we characterize small RNAs in a set of ovary-derived cell lines, including somatic cells (OSS and OSC) and a mixed germline/somatic cell population (fGS/OSS) that exhibits ping-pong piRNA signatures. Collectively, the ovary data reveal new genic piRNA loci, including unusual configurations of piRNA-generating regions. Together with the companion analysis of mRNAs described in a previous study, these small RNA data provide comprehensive information on the transcriptional landscape of diverse Drosophila cell lines. These data should encourage broader usage of fly cell lines, beyond the few that are presently in common usage.

Drosophila melanogaster is a versatile model system that combines sophisticated animal genetics with diverse manipulations of cultured cells (Bellen et al. 2010; Cherbas et al. 2011). In comparison, Caenorhabditis elegans has powerful genetics but no cell lines (Xu and Kim 2011). Reciprocally, most mammalian research is conducted on cultured cells, with only a small fraction of total studies carried out in mice. However, mammalian researchers have exploited the facile generation of immortal cell cultures to generate thousands of lines with distinct properties. Notably, embryonic stem (ES) cell systems are competent to be differentiated into most cell types as well, a concept extended by induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell protocols (Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006). These bolster efforts to model human diseases in cultured cells and promise to revolutionize regenerative and personalized medicine (Wu and Hochedlinger 2011).

Although dwarfed by the available mammalian cell lines, there exists a substantial collection of Drosophila cell lines derived from diverse times and places during fly development (Cherbas et al. 2011). Many of these are available via the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center, which collects other information such as culture conditions, morphological properties, and gene expression properties (https://dgrc.cgb.indiana.edu/). Still, much of the Drosophila community has not embraced cell studies as the mammalian community has. This partly reflects the fact that Drosophilists often train with a mindset of exploiting genetic techniques and the opportunity to work “in the animal.” Nevertheless, it has become increasingly clear that Drosophila cell lines are a valuable adjunct to in vivo studies.

A spectacular illustration of this is provided by studies on the mechanism and exploitation of RNA interference (RNAi). The demonstration that Drosophila S2 cells specifically destroy mRNAs of choice upon treatment with cognate double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) enabled biochemical dissection and purification of the core RNAi machinery (Tuschl et al. 1999; Zamore et al. 2000). This involves generation of 21-nucleotide (nt) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) by a “Dicer” enzyme (later recognized as Dicer-2) and functional silencing via a “Slicer” enzyme (later recognized as AGO2). Transfection and knockdown strategies in S2 cells were also critical for studying the biogenesis and function of microRNAs (miRNAs), a class of ∼22-nt RNAs cleaved from endogenous short hairpins. In comparison, the paucity of cell lines that express gonad-specific ∼24- to 30-nt piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) has hindered their mechanistic elucidation, despite the fact that plenty of piRNA pathway genes are known from genetics (Ishizu et al. 2012). However, the recognition that Drosophila ovarian somatic cells (OSCs) and ovarian somatic sheet (OSS) cells harbor active primary piRNA pathways (Lau et al. 2009; Saito et al. 2009) rapidly made them valuable models for piRNA biogenesis and function (Sienski et al. 2012; Muerdter et al. 2013).

In parallel, the revelation that RNAi is efficiently triggered in S2 cells by soaking in dsRNA was exploited in genome-wide screens (Kiger et al. 2003; Boutros et al. 2004). To date, more than 100 genome-wide screens have been conducted, including for components of diverse signaling pathways and cell biological processes, among others (Flockhart et al. 2012; Schmidt et al. 2013). Such studies illustrate how Drosophila cell lines can be used to discover novel gene functions and understand cellular behaviors, knowledge that can direct in vivo studies (Mohr and Perrimon 2012). While many aspects of signaling and cell biology are common to all cells, there are significant tissue-specific and cell-type-specific factors and cell behaviors. In principle then, genome-wide screens across multiple cell lines could provide richer information. However, the vast majority of screens utilized only a few lines, chiefly S2 or Kc cells.

The popular usage of these particular lines stems from their robust culture, transfection, and knockdown methodologies; many other Drosophila cell lines are tricky to grow and manipulate. However, the underutilization of other cell lines is partly attributable to insufficient characterization. Except for a few Drosophilists with especial interest in particular cell lines, most researchers would be hard-pressed to say that any cultured cell is an appropriate biological model for them. Still, many avenues and opportunities are ripe for exploitation. For example, Drosophila ovary cell lines (Niki et al. 2006) were obscure for several years until the recognition that they harbored piRNAs, which triggered their broad utilization by the piRNA community. Moreover, S2 cells exhibit properties of macrophages and are thus a model system for phagocytosis (Ramet et al. 2002). ML-DmD8 cells share similarities to muscle precursors and were exploited for genome-wide studies of muscle transcriptional codes (Krejci et al. 2009). Other Drosophila cell lines derive from the nervous system and appear useful for studying induction of neural morphology (Tominaga et al. 2010).

A major goal of the modENCODE Project is the systematic characterization of the Drosophila transcriptome. We have deeply annotated its small RNAs across development, tissues, and some cell lines (Berezikov et al. 2011); our colleagues analyzed mRNA expression throughout development (Graveley et al. 2011) and across 25 cell lines (Cherbas et al. 2011). Here, we complete our survey of small RNAs across this diversity of cell lines. We report myriad analyses of their miRNA, siRNA, and piRNA content and identify compelling and novel features of their expression and activity. We examine the relationship of small RNA expression in these cell lines to their conventional transcriptomes and relate these properties back to the animal. Altogether, the deep profiling of small RNAs and mRNAs across this set of cell lines provides a valuable foundation for their study.

Results

Overview of the Drosophila cell line small RNA data sets

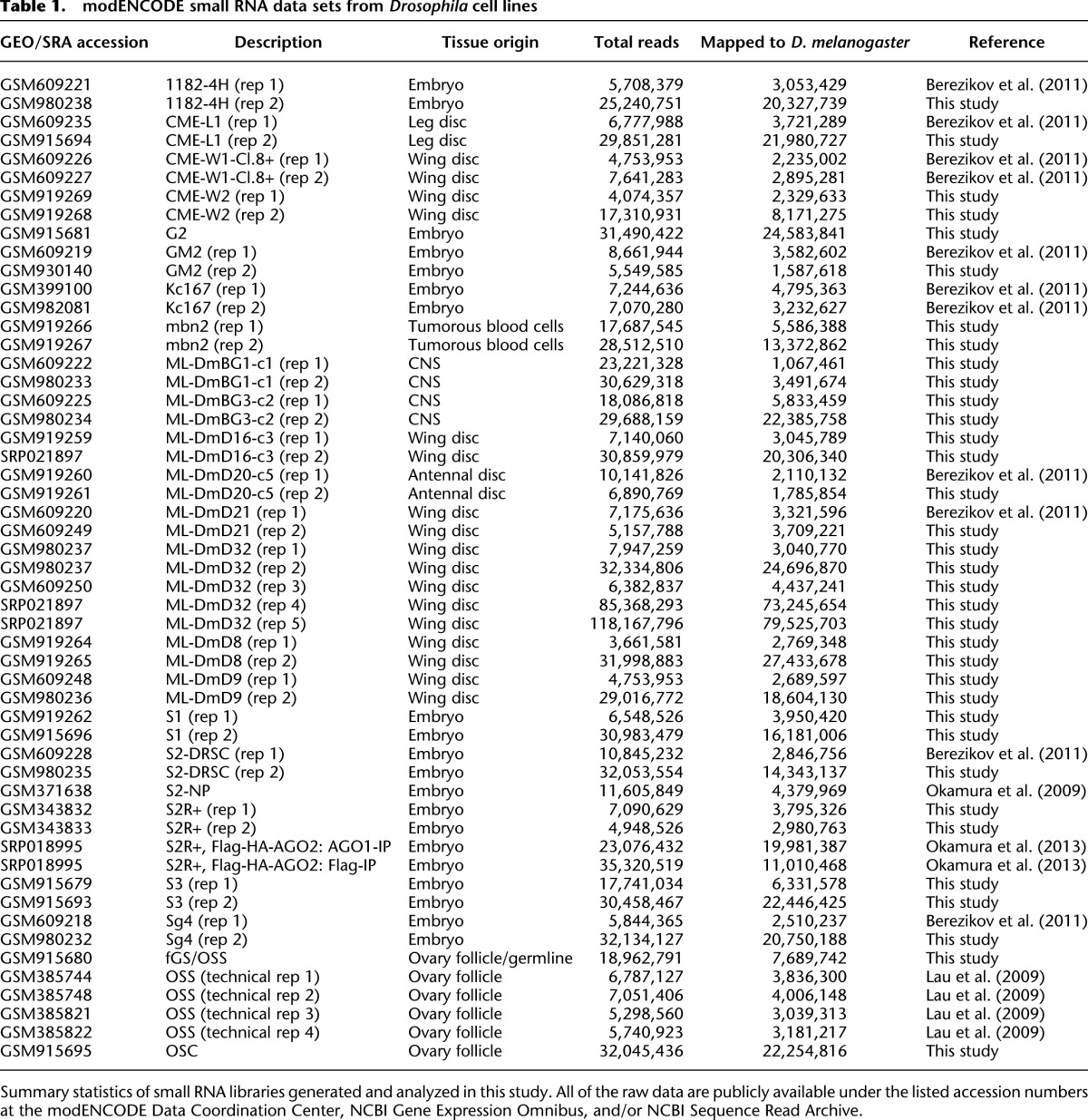

We deeply sequenced total small RNAs from 25 cell lines that cover nearly all lines surveyed in previous transcriptome studies (Cherbas et al. 2011), along with the ovarian OSC, OSS, and fGS/OSS cell lines (Niki et al. 2006) and with AGO1 and AGO2 complexes from S2R+ cells (Table 1). We formally reported 18 data sets previously (Lau et al. 2009; Berezikov et al. 2011; Okamura et al. 2013) but had not analyzed their detailed properties, with the exception of OSS data (Lau et al. 2009; Robine et al. 2009). We generated another 35 data sets for this study, with almost every cell line analyzed in biological replicate. We coordinated our sRNA data production with the transcriptome studies (Cherbas et al. 2011), so that the same RNA samples were analyzed in parallel. The sample IDs are tracked in the metadata of the respective data files at the modENCODE Data Coordination Center (http://www.modencode.org).

Table 1.

modENCODE small RNA data sets from Drosophila cell lines

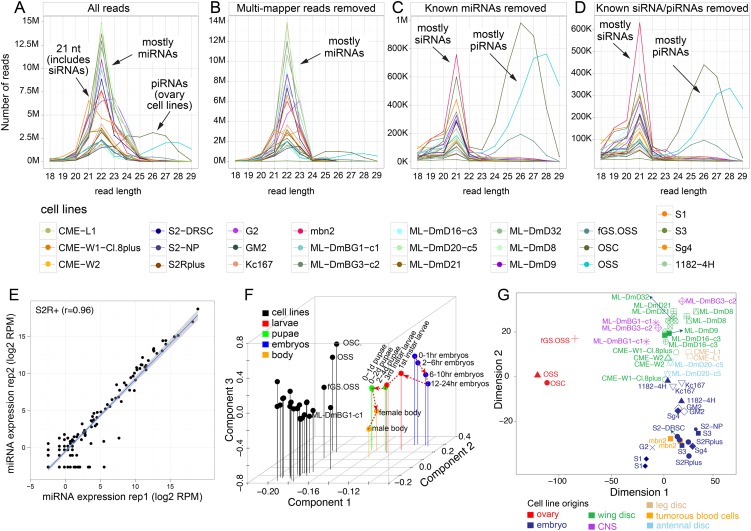

We plotted the size distributions of the libraries and examined how they shift following sequential removal of annotated RNA classes (Fig. 1). Among total reads, 22-nt species were most abundant (Fig. 1A), reflecting the dominant size of miRNAs. Following removal of multimapped reads, which largely corresponded to 21-nt siRNAs from transposable elements (TEs), the read distribution became more tightly distributed around 22 nt (Fig. 1B). In addition, the three ovary-derived cell lines expressed substantial numbers of ≥24-nt piRNAs from TEs, and removal of multimapped reads dampened their remaining piRNA peaks. Removal of known miRNA reads caused loss of the 22-nt peak and appearance of a bimodal distribution with a 21-nt peak across all cell lines, and a 24- to 30-nt peak specific to the three ovary cell lines (Fig. 1C). Among known classes of small RNAs in these size ranges are cis-NAT-siRNAs, hairpin RNA-siRNAs, and genic piRNAs. After removing reads from the known unique siRNA and piRNA loci, we still observed substantial siRNA peaks in all cell lines, as well as piRNA peaks in the three ovary cell lines (Fig. 1D). Therefore, novel small RNA-generating loci remained to be discovered from these data.

Figure 1.

Size distributions of small RNA reads across the 25 Drosophila cell lines. Shown are the distributions of all mapped reads (A) and following sequential removal of multimapper reads (B), of reads from known miRNA loci (C), of reads from known endo-siRNA loci (of the 3′-cis-NAT and hpRNA classes) and of known 3′ UTR piRNA loci (D). Annotated small RNA classes exhibit characteristic preferred sizes, namely, ∼21-nt siRNAs, 22-nt dominant miRNAs, and ∼24- to 29-nt piRNAs. This analysis highlights that an abundance of uniquely mapping, novel siRNA and piRNA reads remains after accounting for all previously annotated Drosophila small RNAs. The color guides for the different cell lines are shown below, and all replicate data were combined for this analysis. The piRNAs were mainly expressed by the ovary-derived cell lines fGS/OSS, OSS, and OSC. (E) Biological replicates of S2R+ small RNAs showed high correlation (r = 0.97). All cell line replicates were well correlated (r > 0.89) (see also Supplemental Fig. S1). (F) Principal component analysis based on sRNA (miRNAs, TE-siRNAs, TE-piRNAs, and piRNA master clusters) expression clearly separates all cell lines from data sets acquired from across a developmental time course. (G) Multidimensional scaling based on sRNAs shows that cell line replicates are generally grouped together, and cell lines from the same tissue origins are generally well grouped together.

We performed correlation analysis to assess the variance of miRNA expression across replicates. A challenge for normalizing miRNA data is the fact that some miRNAs are expressed at much higher levels than others. We used TMM normalization (see Methods) to correct for the “real-estate effect” due to dominance of particular species. Most samples showed high reproducibility, with Pearson correlation coefficients >0.89. An example of the S2R+ replicates is shown in Figure 1E, and other comparisons are shown in Supplemental Figure S1.

Comparison of overall small RNA expression in cell lines vs. tissues

We performed principal components analysis (PCA) of sRNA expression (miRNAs, TE-siRNAs, TE-piRNAs, and piRNA master clusters) in the cell lines and our developmental time series (Chung et al. 2008; Berezikov et al. 2011). We clearly observed that the cell lines exhibited signature commonalities and clustered together, and were well separated from the animal libraries (Fig. 1F). The ovarian cell lines (fGS/OSS, OSS, OSC) were clearly separated from other cell lines, likely due to their shared and unique expression of piRNAs. Comparison of cell line and tissue sRNAs highlighted that the ovarian cell lines clustered more closely to ovaries than to testes, embryos, and heads (Supplemental Fig. S2).

On the other hand, we were able to separate the cell lines using multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis of annotated small RNA classes, which reflected their individuality (Fig. 1G). The biological replicates were generally clustered, attesting to the reproducibility of these data. Cell lines derived from the same tissue origins often grouped together as well, with the ovary cell lines substantially further separated from the other cell lines. These analyses support analogous conclusions to those obtained from protein-coding gene expression (Cherbas et al. 2011), in that this diverse set of Drosophila cell lines shares overall common signatures while retaining individual characteristics.

Overall features of miRNA expression

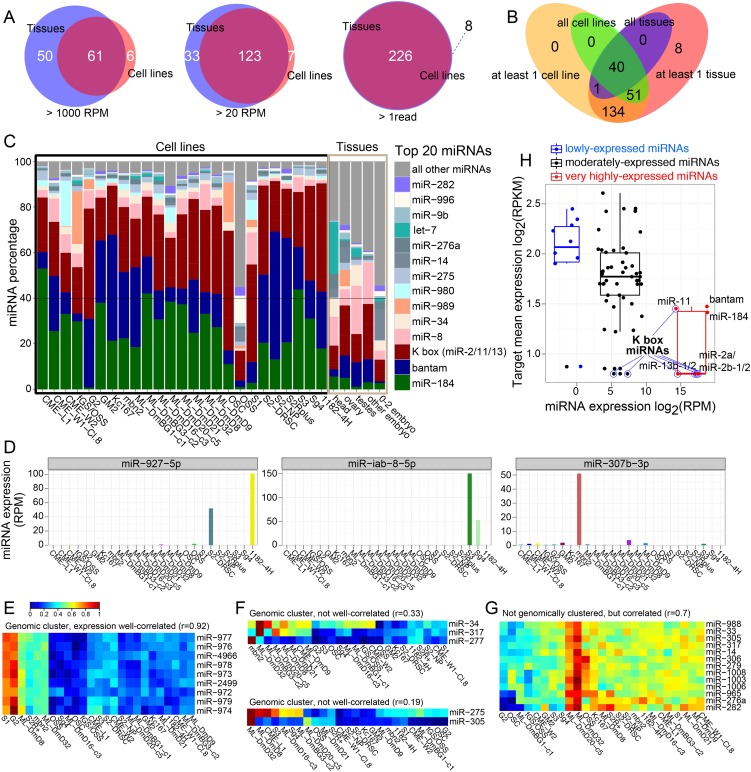

We analyzed the expression of known miRNAs in our cell line libraries. Among 234 annotated miRNAs (excluding miR-280/287/288/289 that are conserved loci, but lack evidence of sRNA patterns characteristic of miRNAs) (Berezikov et al. 2010), we detected 67, 130, and 226 miRNA loci at ≥1000 RPM, ≥20 RPM, or ≥1 mature sequence reads, respectively, among the 25 cell lines. Therefore, although cell lines presumably sample only a subset of all cell types present in the animal, nearly all miRNAs annotated from diverse Drosophila tissue libraries were detected at some level in cell lines.

The overlaps between cell line and tissue miRNA sets, at different thresholds in at least one cell line or tissue, are shown in Figure 2A. Forty miRNAs showed expression across all samples (see Supplemental Table S2); however, 51 miRNAs detected in all cell lines were not similarly detected in all tissues (Fig. 2B). Focusing on the abundant miRNAs in cell lines, a striking feature was that a few loci repeatedly dominated the scene. In particular, bantam and miR-184 were by far the two most abundant individual miRNAs across almost all cell lines, typically accounting for well over 40% of the miRNA reads (Fig. 2C). We used Northern blots to validate that miR-184 accumulates to a much higher level in most cell lines (excepting the G2 and S1 cell lines) compared with multiple embryonic stages or ovaries (Supplemental Fig. S3), these being the best-characterized locations of miR-184 expression (Aboobaker et al. 2005) and function (Iovino et al. 2009). Members of the miR-2/-11/-13 (K box) family often accounted for another 20%–30% of reads as well. The common, dominant representation of these three miRNA seed groups was remarkable, given that these cell lines were isolated from various developmental stages and tissues over a period of decades. We speculate that the high expression of these miRNAs may be beneficial during cell immortalization and/or adaption to in vitro conditions.

Figure 2.

Properties of miRNA expression across cell lines. (A) Overlaps between miRNA expression across the aggregated cell line and tissue data sets, at different thresholds of miRNA expression in at least one tissue or cell line, respectively. (B) Summary of overlap of miRNAs (≥1 read) between cell lines and tissues. (C) Percentage distribution of the top 20 expressed miRNAs in individual cell line and tissue data sets (normalized by total miRNA reads). (D) Examples of cell-specific singletons, i.e., expressed in a few cell lines and miRNAs. (E) Example of a highly cell-specific miRNA cluster. All the members of the mir-972→979 cluster are specifically coexpressed in S1 and G2 cells. (F) Examples of genomic miRNA clusters, whose members exhibit disparate expression patterns across different cell lines. (G) A cluster of genomically separate miRNAs that exhibits largely correlated expression patterns across different cell lines. (H) Global anti-correlation of miRNAs and their targets. Target expression (RPKM) for targets of the highly expressed miRs (miR-184/bantam/K box miRNAs), 40th–60th percentile moderately expressed miRNAs, and the lowest 20th percentile miRNAs.

Some miRNAs achieved high stage- or tissue-specific expression, but not in any cell lines. Notably, the eight-member mir-309→mir-6 cluster is highly expressed at the onset of zygotic expression, but its transcription ceases after early embryogenesis (Ruby et al. 2007; Bushati et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008b). Since this entire cluster is universally nearly absent across cell lines (Supplemental Fig. S4), it may be that no cell line recapitulates the early embryonic state. Reciprocally, some miRNAs were specifically expressed in particular cell lines (Supplemental Fig. S5). For example, miR-927-5p was only expressed in 1182-4H and S2-DRSC cells (and not in the related S2R+ or S2-NP cells), miR-iab-8-5p was restricted to S3 and Sg4, and miR-307b-3p was specific to mbn2 cells (Fig. 2D).

We detected coregulated miRNAs across cell lines and tissues using clustering analysis. We calculated the weighted pairwise correlation of log expression between miRNAs as a distance measure and used a partitioning density-based clustering method (see Methods). The mir-972→mir-979 cluster is notable as the largest miRNA cluster in Drosophila melanogaster (Berezikov et al. 2011), and all members of this cluster were specifically expressed in G2 cell and S1 cell lines (Fig. 2E). In the animal, this miRNA cluster is dominantly expressed in testes (Supplemental Fig. S6). In general, miRNA clusters exhibited coordinated expression across cell lines, as expected (Supplemental Fig. S7). However, members of the mir-277/317/34 and mir-275/305 clusters showed discordant expression (pairwise correlations of r = 0.33 and r = 0.19, respectively) (Fig. 2F). This may hint at their potential post-transcriptional regulation. Finally, we detected some groups of genomically unlinked miRNAs that exhibited coordinated expression; the largest such group is shown in Figure 2G.

Global anti-correlation of highly expressed miRNAs and their targets across cell lines

As some miRNAs were expressed at high levels in cell lines, we asked if this had detectable influence on their transcriptomes. Earlier studies provided evidence for anti-correlation of miRNA expression and target accumulation (Farh et al. 2005; Stark et al. 2005; Sood et al. 2006), but this has not been examined in Drosophila cell lines. We compared the expression of predicted conserved targets by TargetScanS (http://www.targetscan.org/fly_12/) of highly (miR-184/bantam/K box miRNAs), lowly (bottom 20%), and moderately (middle 40%–60%) expressed miRNAs in cell lines. Indeed, we saw that the regulatory activity of abundant miRNAs was registered on the transcriptome (Fig. 2H), and fitting target and miRNA expression across cell lines into a linear regression model revealed significant negative relationships (P = 1.2 × 10−4). Supplemental Figure S8 shows global anti-correlations of miRNA and target expression across individual cell lines.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis showed the targets of highly expressed miRNAs (K box, bantam, miR-184) were enriched for cell fate specification (P = 7 × 10−5) and regulation of transcription (P = 1 × 10−7) terms. This may plausibly relate to the activity of these miRNAs in suppressing aspects of differentiation in these immortalized cells. The full GO analyses are provided in Supplemental Table S3. Overall, we demonstrate that recurrent, high expression of specific miRNAs across diverse cell lines has shared consequences on the transcriptomes and may have been selected during cell line derivation.

Annotation of novel miRNA loci

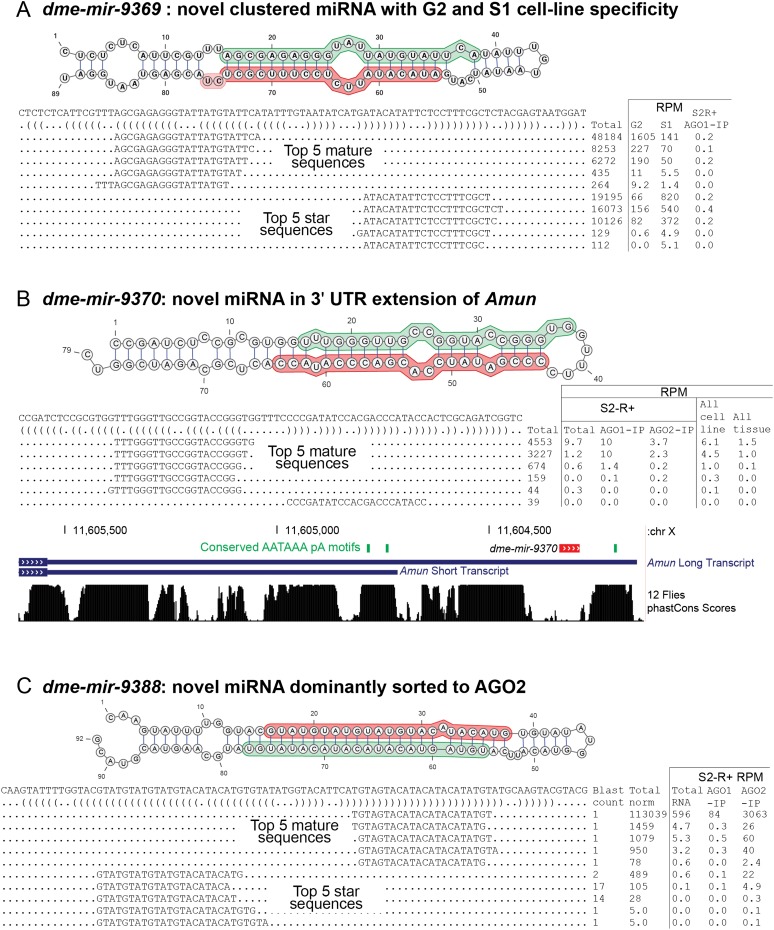

Our previous annotation of miRNAs from ∼1 billion Drosophila reads included some cell data, but the vast majority derived from a developmental time-course and selected tissues (Berezikov et al. 2011). We were curious if these new cell line data, comprising more than 400M reads mapped to the reference genome, might reveal novel miRNAs. We used miRDeep2 (Friedlander et al. 2012) to identify new miRNA loci. We vetted all of the candidates manually to arrive at conservative annotations of 18 novel canonical miRNAs, which we required to exhibit clearly specific read pileups that reflected miRNA/star duplexes with 3′ overhangs. In Figure 3, we highlight a few novel miRNAs with notable features and provide a full accounting of all the novel miRNAs in Supplemental Figure S9 and Supplemental Table S4.

Figure 3.

Examples of novel Drosophila miRNA loci. (A) A new member of the mir-972→979 cluster, namely, dme-mir-9369, which exhibits specificity for S1 and G2 cells (similar to other cluster members) (Fig. 2D). (B) dme-mir-9370 is a miRNA present in an alternative 3′ UTR extension of Amun. (C) dme-mir-9388 is a miRNA hairpin with an unusually paired miRNA/star duplex, whose small RNAs are strongly sorted to AGO2, the siRNA effector.

One novel miRNA (dme-mir-9369) was abundantly expressed in the G2 cell line, modestly expressed in S1 cells, and virtually absent from all other cell lines (Fig. 3A). This miRNA is located within the mir-972→mir-979 cluster, whose members exhibit similar cell specificity of expression (Fig. 2E). Thus, this largest Drosophila miRNA cluster is even larger than earlier appreciated.

A substantial fraction of D. melanogaster transcripts are subject to alternative cleavage and polyadenylation (APA), frequently resulting in tissue-specific 3′ UTRs (Smibert et al. 2012). We identified a new miRNA (dme-mir-9370) located in a 3′ UTR extension of Amun; the usage of both 3′ ends is supported by the existence of well-conserved AAUAAA signals upstream of both proximal and distal termini (Fig. 3B). This miRNA was dominantly cloned in our cell lines, and we recovered substantial reads in AGO1-IP libraries and fewer reads in AGO2-IP libraries, consistent with most known Drosophila miRNAs. It was recently reported that during wound healing, there is dynamic competition between protein and miRNA production from the FSTL1 locus, which harbors MIR198 in its 3′ UTR (Sundaram et al. 2013). The Amun locus represents a further potential twist, since the location of this miRNA suggests interplay between APA, miRNA biogenesis, and host mRNA stability.

A third notable example is dme-mir-9388 (Fig. 3C). Its 3p reads map uniquely and dominate 5p reads by nearly 1000-fold, and the miRNA/star duplex exhibits 2-nt 3′ overhangs at both termini. Curiously, while there are also some reads mapped uniquely to the 5p arm, the 21- to 22-nt 5p species have 14 and 17 genomic matches, respectively, indicating a relationship to a repetitive element despite clear evidence for small RNA production from this particular locus. We note that its duplex region is nearly completely paired, including within the central duplex region that is predicted to promote loading to AGO2 (Czech et al. 2009; Okamura et al. 2009; Ghildiyal et al. 2010). Indeed, a high fraction of reads from both arms derived specifically from an AGO2-IP library from S2-R+ cells, with very few reads in the corresponding AGO1-IP library (Fig. 3C). Thus, this miRNA hairpin exhibits Ago sorting that is characteristic of siRNAs.

General features of endo-siRNAs from TEs and cis-NATs

The major substrates for the Drosophila endogenous siRNA (endo-siRNA) pathway include TEs, long inverted repeat transcripts (hairpin RNAs), and cis-natural antisense transcripts (cis-NATs) (Okamura and Lai 2008). Of the latter, the dominant class involves convergent transcription units that overlap within their 3′ UTRs (3′-cis-NAT-siRNA loci) (Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008a). Exceptional loci generate siRNAs across internal exons, introns, or 5′ UTRs, exemplars of which reside in the klarsicht and thickveins loci (i.e., “klar-type” siRNA loci).

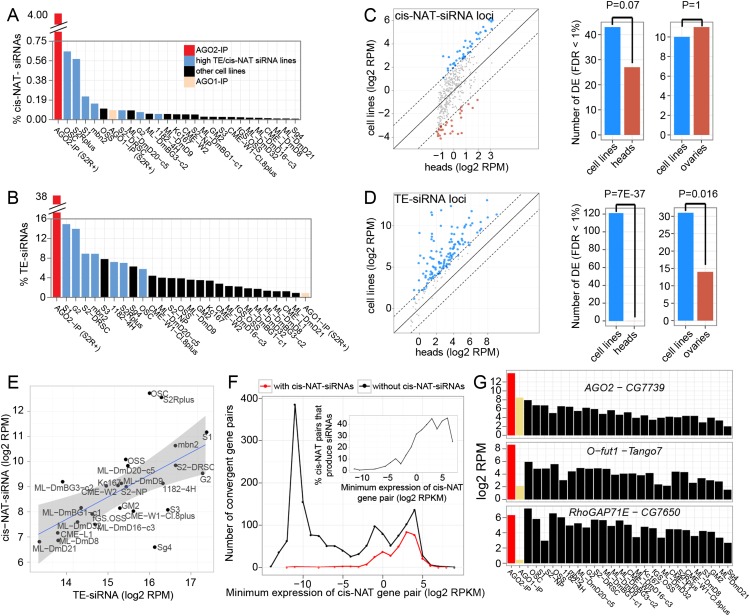

We developed a classifier for cis-NAT-siRNA loci that identifies genomic segments generating dominantly 21-nt reads from both strands at ≥1 RPM (see Methods). By running this across the cell line data sets, we identified 1017 (868 novel) cis-NAT-siRNA loci, of which 371 (223 novel) were from 3′ convergent transcript pairs. As expected, cis-NAT-siRNAs were most abundant in the AGO2-IP library (4% of total reads, sevenfold enrichment over the parent S2R+ total RNA libraries) and were depleted from the AGO1-IP library (Fig. 4A). Since cis-NAT-siRNAs were originally identified using the divergent S2 and OSS cell lines (Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008a; Lau et al. 2009), one might have anticipated this to be a shared property of Drosophila cell lines. OSCs and S2R+ cells exhibited the highest levels of cis-NAT-siRNAs, while S1 and mbn2 cells accumulated the next highest levels. However, most other cell lines proved to express vanishing amounts of cis-NAT-siRNAs (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Features of endo-siRNA expression across Drosophila cell lines. (A) Expression of 21-nt 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA loci across cell lines. All are total RNA libraries, except for AGO2-IP and AGO1-IP data sets from S2R+ cells. (B) Expression of 21-nt TE-siRNAs across cell lines. Light blue bars show the intersection (seven cell lines) of the top 10 ranked cell lines with the highest cis-NAT-siRNA and TE-siRNA expression. (C,D) Comparison of TE-siRNA and 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA expression in cell lines and tissues. Differentially expressed siRNAs (FDR < 1%, see Methods) are shown in blue (high in cell lines) and red (high in tissues). Scatter plots show mean expression in cell lines vs. head libraries for each siRNA loci (−4 indicates fourfold changes marked as dashed lines around 0). Comparisons to other tissues are in Supplemental Figure S10. Barplots compare number of differentially expressed siRNA loci in cell lines vs. heads and ovaries (P-values by binomial test). (E) Correlation of TE-siRNA and 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA expression across cell lines. Linear regression lines were fit to the data, and bands show the standard error at each position (R2 = 0.38). (F) Comparison of 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA and parent cis-NAT-mRNA expression. Plotted are the number of cis-NAT loci at the designated bins of the lower-expressed mRNA partner (to define the minimum cis-NAT expression level), split into loci that did or did not produce siRNAs. (G) Examples of 3′-cis-NAT loci that generated substantial siRNAs in most or all cell lines analyzed.

Curiously, TE-siRNAs (i.e., specifically 21-nt TE reads) were generally expressed at much higher levels than cis-NAT-siRNAs across the cell lines. Peak TE-siRNA levels were seen in S1 cell and G2 cell lines (∼15% of total reads), but the cell lines were overall more similar in their accumulation of TE-siRNAs compared with cis-NAT-siRNAs (Fig. 4A, B). We further compared siRNA production in cell lines vs. tissues. In aggregate, the cell lines showed a small increase in cis-NAT-siRNAs compared with heads, although this did not reach statistical significance (FDR < 1%; 43 vs. 27, P = 0.07), and showed similar numbers of differentially expressed cis-NAT-siRNA loci compared with ovaries (FDR < 1%; 10 vs. 11, P = 1) (Fig. 4C). In contrast, 120 TE classes preferentially generated siRNAs in cell lines compared with head libraries (FDR < 1%), whereas none were specifically found in head libraries (P = 7 × 10−37, binomial test) (Fig. 4D). Even compared with ovaries, which exhibit higher TE-siRNA levels than other tissues, cell lines exhibited substantially more differentially expressed TE-siRNAs (31 vs. 14, P = 0.016) (Fig. 4D). Comparisons to other tissues are shown in Supplemental Figure S10.

Figure 4E shows that TE-siRNA and cis-NAT-siRNA abundance across the cell lines were correlated (r = 0.62). However, the global elevation of TE-siRNAs across most cell lines, relative to tissues and also relative to cis-NAT-siRNAs across the cell lines, suggests that TE mobilization and subsequent defense by the RNAi pathway may be a common feature of cell line derivation.

Concordant and discordant relationships of cis-NAT-RNA and siRNA accumulation

We previously concluded that the mere coexpression of top and bottom strand loci in a cis-NAT was not predictive of siRNA production (Okamura et al. 2008a). We based this conclusion on S2 cells, but our broader cell line sRNA data sets along with transcriptome data (Cherbas et al. 2011) permitted more systematic analyses. When using the level of the lower-expressed cis-NAT partner to infer potential availability of dsRNA, 3′-cis-NAT-siRNAs preferentially emanated from higher-expressed pairs (Fig. 4F, inset). Nevertheless, for every bin of cis-NAT expression level analyzed, an equivalent or indeed higher number of loci failed to produce siRNAs, compared with those that did (Fig. 4F). Thus, bidirectional transcription does not guarantee siRNA biogenesis, perhaps implying licensing steps for dsRNA formation or access to the RNAi machinery.

One of the highest-expressed 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA loci in S2 cells and ovaries is AGO2- CG7739 (Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008a), which is notable since AGO2 encodes the siRNA effector. This locus actually generates relatively abundant siRNAs across all cell lines (Fig. 4G), indicating that this is a common feature of Drosophila tissues and cells. Curiously, the core siRNA loading factor r2d2 and its cis-NAT partner cdc14 also generate substantial siRNAs across most cell lines (Supplemental Fig. S11). Additional examples of 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA loci that were common to most cells are shown in Figure 4G and Supplemental Figure S11. Based on mRNA-seq data, the average expression of genes producing siRNAs common to most cells is substantially higher than other genes producing siRNAs (P = 5 × 10−6, one-sided t-test) (Supplemental Fig. S11).

A plethora of novel cis-NAT-siRNA loci of 3′ overlap and klar-type classes

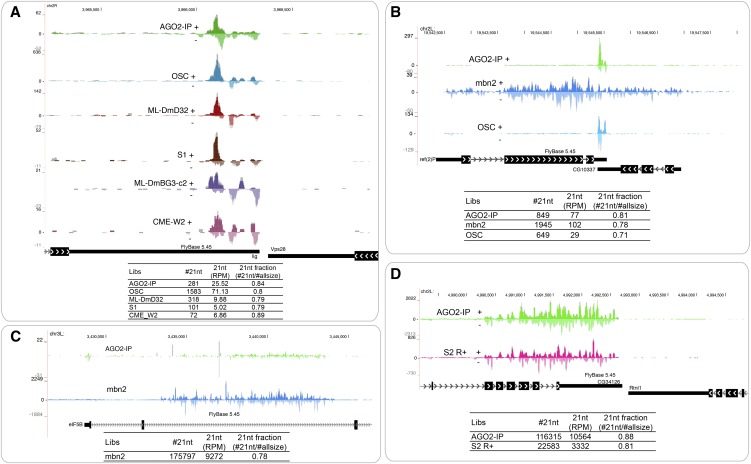

We identified many novel 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA loci across the cell line data (Supplemental Table S5; Supplemental Fig. S12). In many cases, these involved annotated convergent 3′ UTRs, for which we earlier did not have sufficient or appropriate sRNA data to be able to call siRNA production confidently. However, notable were examples of 3′-cis-NAT-siRNAs emanating from unannotated 3′ UTRs, which demonstrate that the extensively updated Drosophila transcript models (Graveley et al. 2011; Smibert et al. 2012) still remain incomplete. For example, we recovered abundant siRNAs from an unannotated, presumed overlap of the lig and Vps28 3′ UTRs, including reads in AGO2-IP data from S2 cells (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Examples of novel cis-NAT-siRNA loci annotated in this study. (A) The convergent genes lig and Vps28 have 3′ UTRs that are not annotated to overlap; however, the specific accumulation of abundant siRNAs between these gene models suggests that their 3′ UTRs indeed overlap in several cell lines. This is bolstered by the presence of overlap siRNAs in AGO2-IP data (21-nt read coverage shown in color; coverage over all read sizes shown in gray). (B) Example of alternative 3′ UTRs generating distinct genomic limits of siRNAs. The limits of siRNAs from the ref(2)P/CG10337 pair in OSC cells and S2R+ cells (here showing AGO2-IP data) strictly obey the overlap limits of their annotated gene models. In contrast, the genomic extent of siRNA accumulation is greatly expanded in mbn2 cells. (C) An especially abundant and expansive cis-NAT-siRNA locus in the intron of eIF5B (overlapping one alternative exon) is expressed specifically in mbn2 cells. (D) Highly expressed siRNAs emanate from the 3′ region of CG34126, including both exons and introns, potentially suggesting that the siRNA substrate involves an unprocessed form of this gene.

In other cases, we observed apparent cases of alternative polyadenylation (APA) that generate different genomic extents of 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA production in different cells. Figure 5B shows that siRNA accumulation from the ref(2)P/CG10337 3′-cis-NAT respects their annotated 3′ termini in several cell types, including S1 cells and OSS cells. However, the siRNAs extend across a much broader region in mbn2 cells, implying extension of 3′ UTRs on both top and bottom strand genes in this cell line.

Our genome-wide segmentation recovered siRNAs from cis-NATs of unexpected configuration. For example, a ∼10-kb region of an eIF5B intron generated more than 175,000 siRNAs (i.e., counting only 21-nt reads), specifically in mbn2 cells (Fig. 5C). Such an extended domain of abundant siRNA production resembles those generated from introns of klar, so we refer to this as “klar-type.” Other instances of klar-type loci are provided in Supplemental Figure S12. Figure 5D shows a prominent siRNA locus that overlaps multiple 3′ exons and introns of CG34126 and terminates rather precisely at its longest annotated 3′ UTR. Although the neighboring 3′ convergent gene Rtnl1 is practically adjacent to CG34126, siRNAs did not extend into this gene. Moreover, while 3′-cis-NAT-siRNAs respect exonic boundaries (Okamura et al. 2008a), CG34126 siRNAs were not depleted in its introns, suggesting they might not be generated from mRNA overlaps. Finally, we also recovered examples of cis-NAT-siRNA loci involving 5′ UTRs and covering gene bodies (Supplemental Fig. S12). Such novel configurations of siRNA loci raise new questions on the biogenesis of endo-siRNAs.

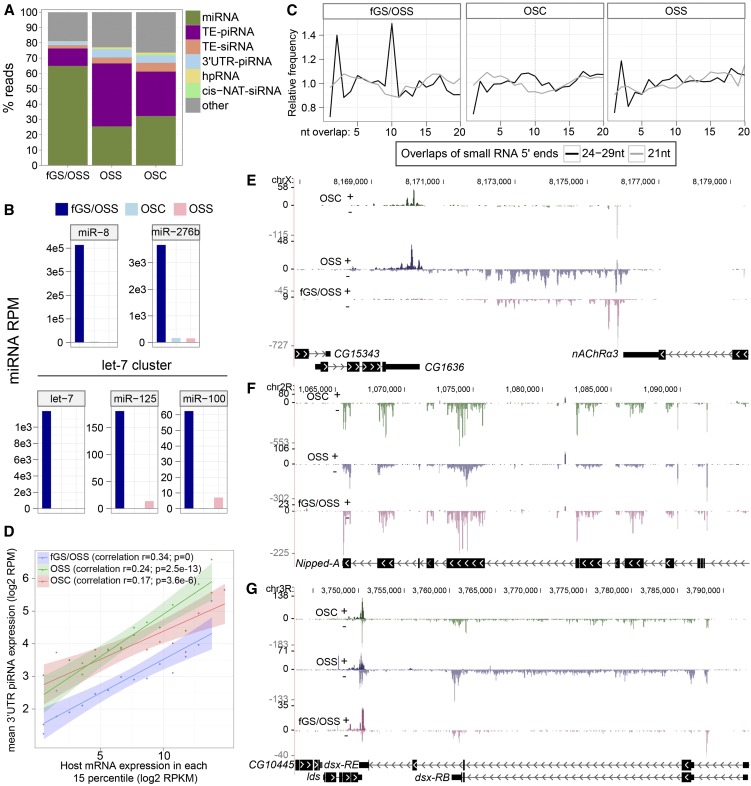

Inference of germline-restricted miRNAs through comparison of ovarian cell lines

Niki et al. (2006) described an ovarian cell culture containing both germline and somatic cells (fGS/OSS), from which germline (fGS) cells were eventually exhausted leaving a pure somatic population (OSS). We showed that OSS cells exhibit a robust primary piRNA pathway, but lack ping-pong piRNAs (Lau et al. 2009). Siomi and colleagues independently derived a somatic culture from fGS/OSS, which they termed OSC (Saito et al. 2009); these cells exhibit similar signatures to OSS. We deeply sequenced small RNAs from OSCs and fGS/OSS cells and compared them to OSS; we also included an independent OSC sRNA data set recently reported by Brennecke and colleagues (Sienski et al. 2012). OSS and OSC cells contained 46% and 34% piRNAs, respectively (defined as 24- to 30-nt reads), whereas fGS/OSS cells contained only 14% piRNAs (Fig. 6A). Thus, some aspect of piRNA biogenesis may be more robust in the OSS/OSC cell systems.

Figure 6.

Analysis of miRNAs and piRNAs in ovarian cell lines. (A) Expression distribution (percentage relative to total mapped reads) of annotated endogenous small RNAs in ovarian cell lines. (B) Examples of miRNAs that are highly expressed only in fGS/OSS and not in either the OSS or OSC cell lines. We infer that these miRNAs are specific to the “fGS” component of fGS/OSS, i.e., that they are germline-specific miRNAs. (C) Ping-pong signatures showing a characteristic peak at a 10-bp overlap between the 5′ ends of complementary species are found specifically among the 24- to 29-nt reads of fGS/OSS cells, but not among their 21-nt reads. OSC and OSS do not show such a signature. (D) Correlation of 3′ UTR-piRNAs and their host genes. The distribution across 15 percentiles of host gene expression (x-axis) vs. mean 3′ UTR piRNA expression (y-axis) is plotted. Linear regression lines were fit to the binned data, and bands show the standard error at each position. Correlation coefficients were calculated using all raw data. (E) Example of a novel 3′ UTR-piRNA locus that is specific to fGS/OSS cells. (F) Example of piRNAs produced from Nipped-A coding regions. (G) Example of piRNAs mainly produced from dsx introns. The 3′ UTR overlapping region of lds and dsx also generates piRNAs from both strands.

Since the germline component of fGS/OSS cells appears modest (Niki et al. 2006), we expect the majority of miRNAs to be common to all three ovarian cell lines. However, comparison of these cell lines provided an opportunity to infer potential germline-enriched miRNAs. Such a question is difficult to answer in the intact animal, due to the challenge of purifying sufficient somatic or germline cells for sRNA sequencing. We hypothesized that miRNAs that were independently lost in both OSS and OSC cell lines, relative to the fGS/OSS parent population, were good candidates for “fGS”-restricted miRNAs. We indeed identified a number of miRNAs that satisfied these criteria (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S13). In some cases, the coordinated expression of genomic clusters provided further evidence for the veracity of these measurements. For example, all members of the let-7/mir-100/mir-125 cluster (Fig. 6B) and mir-959→mir-964 cluster (Supplemental Fig. S13) were well expressed in fGS/OSS cells but were barely present in either OSS cells or OSC cells. These miRNAs are good candidates for loci that may potentially be expressed in ovarian germline but not somatic cells.

Primary and ping-pong piRNA pathways in ovarian Drosophila cell lines

Unlike miRNAs and siRNAs, which are synthesized by most if not all cell types, piRNAs are generated by specialized gonad-restricted machinery (Aravin et al. 2003; Brennecke et al. 2007). The genetic dependence and cell specificity of different piRNAs led to the appreciation of primary and ping-pong pathways (Lau et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009; Malone et al. 2009). Somatic ovarian cells generate only primary piRNAs, which generally derive from the fragmentation of TE-rich long noncoding RNAs, TE transcripts, or mRNA 3′ UTRs. The germline has both primary piRNAs and secondary piRNAs generated by the cleavage of complementary target transcripts, usually in the service of transposon defense. A defining feature of ping-pong activity is enrichment of complementary piRNAs that overlap by 10 nt, which stems from the fact that these pairs are generated by Slicer-mediated cleavage of piRNA/target pairs loaded in Aubergine or AGO3 (Brennecke et al. 2007; Gunawardane et al. 2007).

OSS and OSC cells lacked specificity for any register of complementary piRNAs, as expected, reflecting that they only bear a primary pathway. In contrast, analysis of complementary piRNAs from fGS/OSS cells revealed a clear 10A peak (Fig. 6C). Consistent with this, we observed higher expression of several germline piRNA clusters (e.g., 42AB, chr2L:22735000, and piRNA cluster 6) in fGS/OSS cells, relative to either OSS or OSC cells (Supplemental Fig. S14). This is the first demonstration of an active ping-pong pathway in a Drosophila cultured cell line.

Features and annotation of genic piRNA loci

Our final analyses concerned piRNAs from mRNAs, whose 3′ UTRs are broad substrates of the primary piRNA pathway (Robine et al. 2009). Correlation analysis of 3′ UTR piRNAs and their host genes showed that higher-expressed transcripts tend to produce more piRNAs (Fig. 6D). Nevertheless, many highly expressed transcripts did not produce piRNAs, implying restricted access of substrates to the piRNA biogenesis machinery.

As shown in Figure 1D, the size distribution of small RNAs from the three ovarian cell lines implies that many piRNA loci remain to be annotated in D. melanogaster. We developed a classifier for piRNA loci that finds genomic segments with dominant and relatively high density of 24- to 30-nt reads (see Methods). Analysis of the three ovary cell lines identified 1211 loci associated with annotated genes that generated substantial piRNAs. Most of these loci generated piRNAs with >60% 5′ uridine bias (OSS, 77%; OSC, 87%; fGS/OSS, 84%), indicating they were mostly substrates of the primary pathway. As expected, the bulk of these loci (1048) corresponded to 3′ UTRs of protein-coding genes (Supplemental Fig. S15A). Many genic piRNA loci were active in all three cell lines (e.g., Dcp2 3′ UTR), but overall, more genic piRNAs were found in OSS/OSC than in fGS/OSS (Supplemental Fig. S15B). Rare instances of 3′ UTR-piRNA loci were restricted to the fGS/OSS data set (e.g., CG8858 3′ UTR), suggesting piRNA production from germline-expressed loci (Supplemental Fig. S16). A number of 3′ UTR loci generated piRNAs regions downstream from the sense strands of annotated 3′ UTRs, indicating the likely existence of extended 3′ UTRs. For example, piRNAs span ∼4000 bp downstream from the nAChRα3 3′ UTR (Fig. 6E) and ∼5000 bp downstream from the mei-P26 3′ UTR (Supplemental Fig. S16). Therefore, as was the case with 3′-cis-NAT-siRNAs, 3′ UTR-piRNAs help identify new isoforms of protein-coding transcripts.

In addition to the dominant 3′ UTR class, we recognized other piRNA configurations. One hundred forty-nine overlapped CDS and/or 5′ UTR exons, (e.g., Nipped-A) (Fig. 6F), which may potentially reflect decreased translational status of these mRNAs (Robine et al. 2009). Curiously, we also identified 81 loci that generated substantial piRNAs from the sense strand of introns. For example, we mapped ∼20,000 piRNAs to an intron of RhoGAP18B (Supplemental Fig. S16), and a multitude of piRNAs were generated from a largely intronic ∼25-kb region of dsx (Fig. 6G). A full accounting of genic piRNA loci is provided in Supplemental Table S6, along with additional compelling examples of piRNA arrangements in Supplemental Figure S16.

Discussion

Commonalities and diversity of long and short RNA expression across cell lines

The conventional transcriptome of Drosophila cell lines exhibits both commonalities and diversity of gene expression. On one hand, many mRNAs were up-regulated across unrelated cell lines, compared with their maximal levels of expression recorded across a developmental time-course of whole-animal samples. This was interpreted to reflect signatures of adaptation to cell immortalization and/or to life in cultured conditions (Cherbas et al. 2011). We hypothesize the same to apply to the select set of miRNAs that accumulate to particularly high levels across Drosophila cell lines (Fig. 2C). For example, bantam is generally highly expressed, and this miRNA is well known as a potent growth-promoting and apoptosis-inhibiting miRNA (Brennecke et al. 2003). Interestingly, a companion study shows the bantam locus is a frequent target of copy number amplification across many modENCODE cell lines, providing a potential molecular rationale for its high expression across diverse cell lines (Lee et al. 2014).

We also found that miR-184 and many members of the K box miRNA family were highly expressed in most cell lines. Similar to bantam, the K box miRNAs directly repress pro-apoptotic genes (Brennecke et al. 2005; Ge et al. 2012). The involvement of miR-184 is more difficult to rationalize; however, its consistent up-regulation in cell lines suggests its activity is generally beneficial in the ex vivo cultured setting. Understanding such activity could prove relevant to deciphering its in vivo function. Moreover, the enhanced expression of these miRNAs in cell lines has impact on their transcriptomes (Fig. 2G), evidence that the shared dominant miRNA signature of diverse cell lines may direct aspects of their existence as cultured cells.

On the other hand, these cell lines exhibit a variety of distinct cell morphologies and properties (Cherbas et al. 2011), which reflect their individuality. We likewise find evidence for cell line-specific small RNA expression (Fig. 1G). This is clearly reflected in the abundance of piRNAs in the three ovary-derived cell lines (Fig. 6), a small RNA class that is largely restricted to gonads. We could even distinguish a likely germline component of small RNA expression in the fGS/OSS culture, as evidenced by the presence of a ping-pong piRNA signature and the presence of certain abundant miRNAs that were excluded from either OSS or OSC. We also observed other miRNAs that were particular to specific cell lines (Fig. 2D); this may reflect their tissues of origin, as inferred from their mRNA profiles (Cherbas et al. 2011).

Extensive sequencing reveals few novel miRNAs but myriad new siRNA and piRNA loci

We have long been invested in annotating Drosophila miRNAs using computational and deep sequencing approaches (Lai et al. 2003; Ruby et al. 2007; Berezikov et al. 2011). In principle, our current deep sequencing data sets might allow us to identify highly cell-specific miRNAs that might not be seen in sequencing data from whole animals or even tissues, which are often composed of a diversity of cell types. In addition, given that these cell lines harbor chromosomal aberrations and aneuploidy (Lee et al. 2014), an intriguing possibility is that their mutated genomes may generate novel transcribed regions that are sources of miRNAs.

In light of these possibilities, it was notable that this set of cell lines essentially recapitulated the expression of virtually all previously annotated Drosophila miRNAs (Fig. 2), even though the previous efforts presumably sampled many cell types and cell states not represented in these 25 cell lines. Beyond this, we recognized a limited number of novel miRNAs (Fig. 3), some of which indeed achieve higher expression in specific cell lines compared with available developmental stage or tissue data sets. But the yield of novel Drosophila miRNAs is certainly diminishing, even as the capacity for deep sequencing increases evermore. These findings extend our previous inference that a limited number of the hundreds of thousands of plausible miRNA-like hairpins are actually competent for biogenesis into specific small RNAs (Berezikov et al. 2010, 2011). Recent studies of highly complex pools of pri-miRNA hairpins reveal additional determinants of successful Drosha substrates (Auyeung et al. 2013), and presumably other features of “successful” miRNA hairpins remain to be elucidated.

On the other hand, these extensive cell line data allowed us to uncover a diversity of novel endo-siRNA and piRNA loci. In particular, we annotated unexpected classes and arrangements of cis-NAT-siRNA loci, including many new loci of the “klar-type,” which generate substantial numbers of siRNA distributed across broad genomic regions (e.g., Fig. 5). These frequently lack evidence for an antisense transcript; others even lack evidence for a stable sense progenitor transcript, and some are not currently associated with any gene annotation. Given that 3′-cis-NAT-siRNA production appears relatively inefficient, the cases of “klar-type” loci that generate abundant siRNAs raise mechanistic questions regarding their genesis. We find that the mbn2 cell line may be an especially good model to study these further. In addition, the ovary-derived cell lines reveal surprising arrangements of piRNA production from genes, not only from 3′ UTRs but also from certain coding regions and across specific introns. We believe that these will serve as useful models for studying the potential intersections of translation, splicing, and piRNA biogenesis.

Overall, while we only scratched the surface of these deep and broad small RNA data, we provide abundant evidence that the wealth of Drosophila cell lines can be used to infer and interrogate the biogenesis and function of diverse classes of small RNAs. Collectively, they constitute a natural complement to the rich genetics the fruit fly system offers by permitting studies of relatively homogenous cell populations. Companion analysis of the conventional transcriptome of these cell lines supported the proposition that each provides a unique microcosm within the Drosophila universe (Cherbas et al. 2011). Our current data sets and analyses further this notion by demonstrating myriad new aspects of miRNA expression and processing, siRNA biogenesis, and piRNA accumulation. In sum, this variety of Drosophila cell lines comprises novel model systems for studying Argonaute-mediated small RNA pathways.

Methods

Preparation of RNA from Drosophila cell cultures

Culture conditions of cell lines analyzed in this study were previously described (Niki et al. 2006; Cherbas et al. 2011) and are summarized in Supplemental Table S7; S2R+ cells stably expressing Flag-HA-AGO2 were also previously described (Okamura et al. 2009). We collected five to 10 plates of cells at ∼5 × 106/mL (10 mL/plate) by centrifugation (1000g, 5 min) and washed them in 5 mL phosphate-buffered saline (2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl at pH 7.2). After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 0.75 mL TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA was extracted and dissolved in DNase/RNase-free water. RNA concentration was determined by absorbance using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer.

The quality of RNA samples was confirmed by Northern blots for RpL11-RA, using 5 μg total RNA and the Ambion NorthernMax-Gly, BrightStar Psoralen-Biotin, and BrightStar BioDetect kits. All RNA samples were stored at −80°C and shipped from the Indiana group to the New York group on dry ice. A detailed protocol for RNA extraction used by the modENCODE transcriptome project is provided as Supplemental Text.

Generation of small RNA libraries

We deeply sequenced small RNAs from D. melanogaster cell lines using previously described methods (Czech et al. 2008; Berezikov et al. 2011). Most of these were performed in biological replicate samples and comprise 53 data sets in total. The raw data were deposited in and are publicly available at the modENCODE Data Coordination Center (http://data.modencode.org/). The accession numbers of these data sets and mapping statistics are summarized in Table 1. Small RNA reads were mapped to the Drosophila genome release 5.3 after removing 3′ adaptor sequences. We considered only reads with perfect matches to the genome in subsequent analyses.

Other data resources

We collected publicly available D. melanogaster small RNA data sets from various tissues/cell lines generated from our group and other laboratories from the modENCODE Data Coordination Center, NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), or NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). The accession numbers of all data sets analyzed in this study are summarized in Supplemental Table S1. We also used corresponding cell line poly(A)+ RNA-seq libraries from the modENCODE Data Coordination Center (Cherbas et al. 2011) in the miRNA targets and piRNA host gene expression analyses.

Data normalization

In deep-sequencing data, a “real estate” effect occurs when a small number of highly expressed genes consume a substantial proportion of the sequenced reads (such as bantam and miR-184, which account for >40% of miRNA reads in most cell lines). To account for this, we normalized miRNAs by the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) normalization method in the edgeR/Limma Bioconductor library (Oshlack et al. 2010). We used a transformation method that is designed for handling sequencing count data by correcting for the Poisson noise due to the discrete counts of RNA-seq. Specifically, the voom method of Limma (Smyth 2005) estimates a mean-variance trend for log counts and assigns weights to each data point based on predicted variance, which are incorporated in subsequent analyses. miRNAs, siRNAs, and piRNAs analyzed in this study were normalized and transformed this way. Note that we cannot rule out differences potentially caused by systematic bias due to, for example, library preparation, protocols, or sequencing platform (Linsen et al. 2009).

miRNA clustering and cell line-specific miRNA detection

To cluster miRNAs, we calculated as a distance measure the weighted pairwise correlation of expression between miRNAs (using mean weight of each miRNA pair). We used a graph-based density clustering method termed the highly connected subgraph (HCS) method (Hartuv et al. 2000), which is optimized for homogeneous clusters within a larger heterogeneous background, with a similarity measure consisting of a weighted Pearson correlation coefficient. HCS is parameter free, except for a robust threshold (set to 0.8) to define the false-discovery rate (FDR) of the final cluster set, enabling the detection of definite clusters from the noisy background of cell lines.

To detect cell-specific miRNAs, we used an outlier detection method as follows: A set of exemplar expression vectors to compare against were generated for each cell line, defined by a high expression peak at the given cell line and a low expression value for the rest of the cell lines. A high expression value was taken as the third quartile of miRNA expressions in that cell line, and low expression values were taken as the first quartile of miRNA expressions. The correlations between all miRNAs to these exemplars were calculated and clustered to extract the cell line-specific miRNAs.

Annotation of novel miRNAs

We used miRDeep2 (Friedlander et al. 2012) to identify novel miRNA loci using our cell line libraries (Table 1) and additional sRNA data sets from SRA (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) or GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (Supplemental Table S1). We aligned these to the D. melanogaster reference genome (dm3; http://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/dm3/) using miRDeep2’s mapper.pl script with default parameters. Mapped reads were further processed by the miRDeep2_core_algorithm.pl script using the default parameters, which yield a collection of candidate canonical and noncanonical small RNAs.

miRNA predictions were then examined manually and classified as “novel” or “candidate” based on a collection of features suggestive of RNase III enzymatic cleavage. miRDeep2 ensures a collection of its own features in order to rank and call miRNA. These include the presence of (1) a hairpin secondary structure, (2) at least one star read that forms a mature:star duplex with a 2- to 3-nt overhang, and (3) an enrichment of mature and star strand reads with no more than 10% background, degradation reads. In order to remove false positives from miRDeep2’s automated discovery and to bolster confidence in our annotation, we manually examined all predictions and checked for additional, stricter features, which include (4) precise 5′ cleavage of mature and star sequences, (5) a requirement of at least five star reads, and (6) at least one mature AGO1- or AGO2-IP read. Predictions were classified as “novel” if they satisfied all six criteria, whereas loci marked “candidate” showed a deficiency of one or more manual criteria. All candidate and novel miRNA predictions are summarized within Supplemental Table S4. Detailed HTML (http://compgen.bscb.cornell.edu/mirna/cellline/) and PDF (Supplemental Fig. S9) documents that show the secondary-structure predictions, read-distribution per small RNA library, and read-pileup patterns per miRNA are available.

Annotation of cis-NAT-siRNA loci

The D. melanogaster genome was first segmented based on small RNA-seq read coverage of 25 small RNA cell line libraries. To do so, for each cell line small RNA-seq read coverage of less than five reads/bp was first filtered out, and reads overlapped with these low coverage regions were removed; this step is essential for the segmentation as it removes most of the background read noise. As cis-NAT siRNA loci generate siRNAs from both sense and antisense strands, we prepared the reads from both strands for the segmentation. We used a Bioconductor library seqSegment (Hardcastle et al. 2012) to cluster overlapping read regions into consensus segments. Adjacent segments separated by <200 bp were then merged. We remapped all reads for each library to these segments and excluded the lowly expressed segments with less than 40 reads over all libraries or less than 10 reads for each library. The segments overlapping with TEs were also excluded.

cis-NAT siRNA features were extracted from these segments. Features used for the predictive model included (1) 21-nt read frequency (21-nt reads/all size reads), (2) strand ratio (read ratio of sense/antisense), and (3) read length distribution (four moments: mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, as well as mode). As the negative class of “non-cis-NAT siRNA loci” is not well defined, we built a one-class predictive model (Karatzoglou et al. 2004) that uses the positive class as the training set and classifies the testing set based on how similar they are to the training set. The model was trained on the previously published cis-NAT siRNA loci from our and other’s laboratories (Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008a), using the above features, and applied to predict cis-NAT-siRNAs on all segments genome-wide, separately for each library and for a set combined from all libraries. The overall characteristics of these loci were as follows: minimum expression of 21-nt reads ≥1 RPM for both sense and antisense strands (5th–95th percentile range was 2.6–56.6 RPM); minimum 21-nt percentage (21-nt reads/all size reads) for the calling siRNA loci was 59% (5th–95th percentile range was 64%–87%); minimum sense and antisense strand ratio was less than fourfold (5th–95th percentile range was <2.5 fold).

Annotation of piRNA loci in ovarian cell lines

Genome-wide segmentations were performed similarly to the above for cis-NAT siRNA region detection, except that two segmentations were made separately for sense and antisense strand because piRNAs can be produced from either a single strand or both strands. Adjacent segments separated by <1000 bp were merged. In annotating genic piRNA loci, the segments overlapping with TEs were excluded, and uniquely mapped reads were used. piRNA features included (1) 24- to 30-nt read frequency (24- to 30-nt reads/all size reads), (2) strand ratio (read ratio sense/antisense over 24–30 nt), and (3) read size distribution (mean, standard deviation, and mode over 24–30 nt). The one-class 3′ UTR piRNA predictive model was trained on features of segments residing on a previously published gene set (Robine et al. 2009), containing more than 1000 3′ UTR piRNAs in OSS, and was tested on all segments for three ovarian cell line libraries. We calculated 24- to 30-nt coverage defined as the fraction of number of bases covered by 24- to 30-nt reads over the length of the segment. We further required 24- to 30-nt coverage over the called piRNA segments to be >50%. Minimum expression for annotated piRNA loci were uniquely mapped 24- to 30-nt reads ≥2.3 RPM (5th–95th percentile range was 6–357 RPM); minimum 24- to 30-nt percentage (24- to 30-nt reads/all size reads) for the calling piRNA loci was 60% (5th–95th percentile range was 77%–98%); sense and antisense strand ratio was fourfold to 12-fold (5th–95th percentile range). Size distribution for the identified piRNA loci was 123–3171 bp (5th–95th percentile range); a histogram of the size distribution is shown in Supplemental Figure S15C. For each called piRNA loci, we assigned the genomic region with the most overlap with number of 24- to 30-nt reads (i.e., 3′ UTR, 5′ UTR, CDS, intron, intergenic, as well as putative 3′ UTR regions defined as up to 3 kb downstream from genes, excluding any overlap with downstream genes).

Additional computational analysis

We used targetScanS (version 6.2) (Grimson et al. 2007) to search for conserved targets in 3′ UTRs. We required both miRNA and targets to be conserved in D. melanogaster and one of D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, or D. persimilis; and three of D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. yakuba, or D. erecta. GO enrichment analysis for targets of highly and lowly expressed miRNAs was performed using topGO Bioconductor library (Alexa and Rahnenfuhrer 2010).

PCA and MDS analyses were used to give an overview of sRNA expression in the cell lines compared with that in the developmental time-course and various tissues. The input of these analyses was normalized sRNA expression (log2 RPM). The centroid distances between the ovarian cell lines and tissues were calculated by Euclidean distance.

Differentially expressed miRNA, TE-siRNA, and cis-NAT-siRNA loci between cell lines and tissues (head, ovary, testis, and embryo) were identified by a moderated t-test, and FDRs (Benjamini-Hochberg) were estimated, using the Limma library (Smyth 2005) in Bioconductor.

Data access

All small RNA sequencing data are available from the modENCODE data coordination center, the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and/or the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra), under the accession numbers listed in Table 1.

Acknowledgments

J.M. was supported in part by the Tri-Institutional Training Program in Computational Biology and Medicine (via NIH training grant 1T32GM083937). Work in E.C.L.’s group was supported by R01-GM083300, U01-HG004261, and RC2-HG005639.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.161554.113.

Freely available online through the Genome Research Open Access option.

References

- Aboobaker AA, Tomancak P, Patel N, Rubin GM, Lai EC 2005. Drosophila microRNAs exhibit diverse spatial expression patterns during embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 18017–18022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexa A, Rahnenfuhrer J 2010. topGO: enrichment analysis for gene ontology. http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/2.12/bioc/html/topGO.html

- Aravin A, Lagos-Quintana M, Yalcin A, Zavolan M, Marks D, Snyder B, Gaasterland T, Meyer J, Tuschl T 2003. The small RNA profile during Drosophila melanogaster development. Dev Cell 5: 337–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auyeung VC, Ulitsky I, McGeary SE, Bartel DP 2013. Beyond secondary structure: primary-sequence determinants license pri-miRNA hairpins for processing. Cell 152: 844–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen HJ, Tong C, Tsuda H 2010. 100 years of Drosophila research and its impact on vertebrate neuroscience: a history lesson for the future. Nat Rev Neurosci 11: 514–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov E, Liu N, Flynt AS, Hodges E, Rooks M, Hannon GJ, Lai EC 2010. Evolutionary flux of canonical microRNAs and mirtrons in Drosophila. Nat Genet 42: 6–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov E, Robine N, Samsonova A, Westholm JO, Naqvi A, Hung JH, Okamura K, Dai Q, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Martin R, et al. 2011. Deep annotation of Drosophila melanogaster microRNAs yields insights into their processing, modification, and emergence. Genome Res 21: 203–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros M, Kiger AA, Armknecht S, Kerr K, Hild M, Koch B, Haas SA, Paro R, Perrimon N 2004. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of growth and viability in Drosophila cells. Science 303: 832–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM 2003. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113: 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM 2005. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol 3: e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Aravin AA, Stark A, Dus M, Kellis M, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ 2007. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell 128: 1089–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushati N, Stark A, Brennecke J, Cohen SM 2008. Temporal reciprocity of miRNAs and their targets during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in Drosophila. Curr Biol 18: 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherbas L, Willingham A, Zhang D, Yang L, Zou Y, Eads BD, Carlson JW, Landolin JM, Kapranov P, Dumais J, et al. 2011. The transcriptional diversity of 25 Drosophila cell lines. Genome Res 21: 301–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WJ, Okamura K, Martin R, Lai EC 2008. Endogenous RNA interference provides a somatic defense against Drosophila transposons. Curr Biol 18: 795–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Malone CD, Zhou R, Stark A, Schlingeheyde C, Dus M, Perrimon N, Kellis M, Wohlschlegel J, Sachidanandam R, et al. 2008. An endogenous siRNA pathway in Drosophila. Nature 453: 798–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Zhou R, Erlich Y, Brennecke J, Binari R, Villalta C, Gordon A, Perrimon N, Hannon GJ 2009. Hierarchical rules for Argonaute loading in Drosophila. Mol Cell 36: 445–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farh KK, Grimson A, Jan C, Lewis BP, Johnston WK, Lim LP, Burge CB, Bartel DP 2005. The widespread impact of mammalian microRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science 310: 1817–1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flockhart IT, Booker M, Hu Y, McElvany B, Gilly Q, Mathey-Prevot B, Perrimon N, Mohr SE 2012. FlyRNAi.org: the database of the Drosophila RNAi screening center: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D715–D719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander MR, Mackowiak SD, Li N, Chen W, Rajewsky N 2012. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 37–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge W, Chen YW, Weng R, Lim SF, Buescher M, Zhang R, Cohen SM 2012. Overlapping functions of microRNAs in control of apoptosis during Drosophila embryogenesis. Cell Death Differ 19: 839–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Seitz H, Horwich MD, Li C, Du T, Lee S, Xu J, Kittler EL, Zapp ML, Weng Z, et al. 2008. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science 320: 1077–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Xu J, Seitz H, Weng Z, Zamore PD 2010. Sorting of Drosophila small silencing RNAs partitions microRNA* strands into the RNA interference pathway. RNA 16: 43–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley BR, Brooks AN, Carlson JW, Duff MO, Landolin JM, Yang L, Artieri CG, van Baren MJ, Boley N, Booth BW, et al. 2011. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 471: 473–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP 2007. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 27: 91–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardane LS, Saito K, Nishida KM, Miyoshi K, Kawamura Y, Nagami T, Siomi H, Siomi MC 2007. A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5′ end formation in Drosophila. Science 315: 1587–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle TJ, Kelly KA, Baulcombe DC 2012. Identifying small interfering RNA loci from high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28: 457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartuv E, Schmitt AO, Lange J, Meier-Ewert S, Lehrach H, Shamir R 2000. An algorithm for clustering cDNA fingerprints. Genomics 66: 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovino N, Pane A, Gaul U 2009. miR-184 has multiple roles in Drosophila female germline development. Dev Cell 17: 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizu H, Siomi H, Siomi MC 2012. Biology of PIWI-interacting RNAs: new insights into biogenesis and function inside and outside of germlines. Genes Dev 26: 2361–2373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatzoglou A, Smola A, Hornik K, Zeileis A 2004. Kernlab: an S4 package for kernel methods in R. J Stat Softw 11: 1–20 [Google Scholar]

- Kiger AA, Baum B, Jones S, Jones MR, Coulson A, Echeverri C, Perrimon N 2003. A functional genomic analysis of cell morphology using RNA interference. J Biol 2: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci A, Bernard F, Housden BE, Collins S, Bray SJ 2009. Direct response to Notch activation: signaling crosstalk and incoherent logic. Sci Signal 2: ra1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Tomancak P, Williams RW, Rubin GM 2003. Computational identification of Drosophila microRNA genes. Genome Biol 4: R42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau N, Robine N, Martin R, Chung WJ, Niki Y, Berezikov E, Lai EC 2009. Abundant primary piRNAs, endo-siRNAs and microRNAs in a Drosophila ovary cell line. Genome Res 19: 1776–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, McManus CJ, Cho D, Eaton M, Renda F, Somma M, Cherbas L, May G, Powell S, Zhang D, et al. 2014. DNA copy number evolution in Drosophila modENCODE cell lines. Genome Biol (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Vagin VV, Lee S, Xu J, Ma S, Xi H, Seitz H, Horwich MD, Syrzycka M, Honda BM, et al. 2009. Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell 137: 509–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsen SE, de Wit E, Janssens G, Heater S, Chapman L, Parkin RK, Fritz B, Wyman SK, de Bruijn E, Voest EE, et al. 2009. Limitations and possibilities of small RNA digital gene expression profiling. Nat Methods 6: 474–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Brennecke J, Dus M, Stark A, McCombie WR, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ 2009. Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell 137: 522–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr SE, Perrimon N 2012. RNAi screening: new approaches, understandings, and organisms. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 3: 145–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muerdter F, Guzzardo PM, Gillis J, Luo Y, Yu Y, Chen C, Fekete R, Hannon GJ 2013. A genome-wide RNAi screen draws a genetic framework for transposon control and primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. Mol Cell 50: 736–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki Y, Yamaguchi T, Mahowald AP 2006. Establishment of stable cell lines of Drosophila germ-line stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 16325–16330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Lai EC 2008. Endogenous small interfering RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 673–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Balla S, Martin R, Liu N, Lai EC 2008a. Two distinct mechanisms generate endogenous siRNAs from bidirectional transcription in Drosophila. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 581–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Phillips MD, Tyler DM, Duan H, Chou YT, Lai EC 2008b. The regulatory activity of microRNA* species has substantial influence on microRNA and 3′ UTR evolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 354–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Liu N, Lai EC 2009. Distinct mechanisms for microRNA strand selection by Drosophila Argonautes. Mol Cell 36: 431–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Ladewig E, Zhou L, Lai EC 2013. Functional small RNAs are generated from select miRNA hairpin loops in flies and mammals. Genes Dev 27: 778–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshlack A, Robinson MD, Young MD 2010. From RNA-seq reads to differential expression results. Genome Biol 11: 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramet M, Manfruelli P, Pearson A, Mathey-Prevot B, Ezekowitz RA 2002. Functional genomic analysis of phagocytosis and identification of a Drosophila receptor for E. coli. Nature 416: 644–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robine N, Lau NC, Balla S, Jin Z, Okamura K, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Blower MD, Lai EC 2009. A broadly conserved pathway generates 3′ UTR-directed primary piRNAs. Curr Biol 19: 2066–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby JG, Stark A, Johnston WK, Kellis M, Bartel DP, Lai EC 2007. Evolution, biogenesis, expression, and target predictions of a substantially expanded set of Drosophila microRNAs. Genome Res 17: 1850–1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Inagaki S, Mituyama T, Kawamura Y, Ono Y, Sakota E, Kotani H, Asai K, Siomi H, Siomi MC 2009. A regulatory circuit for piwi by the large Maf gene traffic jam in Drosophila. Nature 461: 1296–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EE, Pelz O, Buhlmann S, Kerr G, Horn T, Boutros M 2013. GenomeRNAi: a database for cell-based and in vivo RNAi phenotypes, 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D1021–D1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienski G, Donertas D, Brennecke J 2012. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by piwi and maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell 151: 964–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert P, Miura P, Westholm JO, Shenker S, May G, Duff MO, Zhang D, Eads B, Carlson J, Brown JB, et al. 2012. Global patterns of tissue-specific alternative polyadenylation in Drosophila. Cell Reports 1: 277–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. 2005. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and Bioconductor (ed. Gentleman VCR, et al.), pp. 397–420. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Sood P, Krek A, Zavolan M, Macino G, Rajewsky N 2006. Cell-type-specific signatures of microRNAs on target mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 2746–2751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Brennecke J, Bushati N, Russell RB, Cohen SM 2005. Animal microRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3′ UTR evolution. Cell 123: 1133–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram GM, Common JE, Gopal FE, Srikanta S, Lakshman K, Lunny DP, Lim TC, Tanavde V, Lane EB, Sampath P 2013. ‘See-saw’ expression of microRNA-198 and FSTL1 from a single transcript in wound healing. Nature 495: 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S 2006. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126: 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Nishihara E, Oogami T, Iwasaki M, Takagi Y, Shimohigashi M, Nakagawa H 2010. Neurite elongation from Drosophila neural BG2-c6 cells stimulated by 20-hydroxyecdysone. Neurosci Lett 482: 250–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuschl T, Zamore PD, Lehmann R, Bartel DP, Sharp PA 1999. Targeted mRNA degradation by double-stranded RNA in vitro. Genes Dev 13: 3191–3197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SM, Hochedlinger K 2011. Harnessing the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Nat Cell Biol 13: 497–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Kim SK 2011. The early bird catches the worm: new technologies for the Caenorhabditis elegans toolkit. Nat Rev Genet 12: 793–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamore PD, Tuschl T, Sharp PA, Bartel DP 2000. RNAi: double-stranded RNA directs the ATP-dependent cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 nucleotide intervals. Cell 101: 25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]