Abstract

The bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata is a common surface colonizer of marine eukaryotes, including the macroalga Ulva australis.Genomic analysis of P. tunicata identified genes potentially involved in surface colonization, including genes with homology to bacterial virulence factors that mediate attachment. Of particular interest is the presence of a gene, designated ptlL32, encoding an ortholog to the Leptospira lipoprotein LipL32, which has been shown to facilitate the interaction of Leptospira sp. with host extracellular matrix (ECM) structures and is thought to be an important virulence trait for pathogenic Leptospira. To investigate the role of PtlL32 in the colonization by P. tunicata we constructed and characterized a ΔptlL32 mutant strain. Whilst P. tunicata ΔptlL32 bound to an abiotic surface with the same capacity as the wild type strain, it had a marked effect on the ability of P. tunicata to bind to ECM, suggesting a specific role in attachment to biological surfaces. Loss of PtlL32 also significantly reduced the capacity for P. tunciata to colonize the host algal surface demonstrating a clear role for this protein as a host-colonization factor. PtlL32 appears to have a patchy distribution across specific groups of environmental bacteria and phylogenetic analysis of PtlL32 orthologous proteins from non-Leptospira species suggests it may have been acquired via horizontal gene transfer between distantly related lineages. This study provides the first evidence for an attachment function for a LipL32-like protein outside the Leptospira and thereby contributes to the understanding of host colonization in ecologically distinct bacterial species.

Keywords: LipL32, seaweed/s, marine bacteria, Pseudoalteromonas, host-microbe interaction, bacterial attachment, algae

Introduction

Macroalgae, or seaweeds, are important ecosystem engineers in temperate marine environments and are a rich source of biologically active compounds (Egan et al., 2008, 2013b). The surface-associated microbial community (SAMC) that rapidly colonize the alga have important roles for normal morphological development, nutrient supply, and defense against unwanted colonizers (Goecke et al., 2010; Wahl et al., 2012; Hollants et al., 2013). Furthermore, the SAMC can influence the health of the host alga and members of this community have the potential to function as opportunistic pathogens (Gachon et al., 2010; Egan et al., 2013a). The composition of the SAMC for many macroalgal species has been well studied and includes both generalist epibionts and host-specific taxa that are distinct from the surrounding seawater (Longford et al., 2007; Tujula et al., 2010; Burke et al., 2011; Lachnit et al., 2011). In contrast, there remains a paucity of knowledge regarding the specific mechanisms that facilitate interaction of the SAMC with the host alga (Egan et al., 2013a).

Attachment is considered a key stage in host colonization, and facilitates the progression of both commensal and pathogenic bacterial-host interactions (Kline et al., 2009; Petrova and Sauer, 2012; Bogino et al., 2013). The abundance of specialized adhesins and pili encoded in the genomes of seaweed-associated bacteria indicates this is similarly an important aspect of macroalgal epibiosis (Thomas et al., 2008; Fernandes et al., 2011; Thole et al., 2012). The marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata was originally isolated from the tunicate Ciona intestinalis and has since been well studied as a surface colonizer of the alga Ulva australis (Holmström et al., 1998; Rao et al., 2005, 2006). Attachment of P. tunicata to biotic and abiotic surfaces occurs within 2 h of contact, and cells proceed into biofilm formation within 24 h through the production of differentiated mushroom-shaped microcolonies (Mai-Prochnow et al., 2004; Dalisay et al., 2006). With the exception of a MSHA-like pili that has been demonstrated to play a role in the attachment of the bacterium to both abiotic and host surfaces (Dalisay et al., 2006), there is a lack of experimental data on the specific factors that mediate host colonization in this bacterium. Genome analysis of P. tunicata has identified genes with homology to putative colonization factors, lipoproteins, pili and outer membrane proteins (OMP) (Thomas et al., 2008). A number of these genes have homology to factors that mediate specific interactions with host cells in other bacteria. One example, designated ptlL32 (locus tag PTD2_05920) encodes for a protein with 47% identity to the Leptospira MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) lipoprotein, LipL32.

Leptospira species are the causative agent of the endemic zoonotic infection, leptospirosis (reviewed in Levett, 2001; Adler and de la Pena Moctezuma, 2010). LipL32 is highly conserved in pathogenic Leptospira species (with an average 98% amino acid identity) where it is the most abundantly expressed lipoprotein (Haake et al., 2004; Dey et al., 2007; Adler et al., 2011). The absence of LipL32 in saprophytic Leptospira strains and its ability to bind to extracellular matrix (ECM) structures suggest that LipL32 plays a major role in host-cell attachment during mammalian infections (Hauk et al., 2008; Hoke et al., 2008; reviewed in Murray, 2013). However the precise involvement of LipL32 in Leptospira pathogenesis remains unclear as recent studies using a L. interrogans lipL32 transposon mutant failed to demonstrate a direct role for this protein in infection models (Murray et al., 2009).

P. tunicata rapidly attaches to ECM structures (Hoke et al., 2011) and the tunicate, C. intestinalis, a natural host of P. tunicata, possesses the genes necessary for ECM synthesis, including those encoding for collagen type IV, fibronectin, laminin, and nidogen (Huxley-Jones et al., 2007). In addition, Ulva liza, a close relative of U. australis, possesses the genes encoding ECM-like proteins, including collagen (Stanley et al., 2005). Interestingly, recombinantly produced PtlL32 bind ECM structures in a manner analogous to LipL32 from Leptospira sp. (Hoke et al., 2008). Moreover heterologously expressed PtlL32 is immunologically cross reactive with Leptospira LipL32 antibodies (Hoke et al., 2008) and the amino acid sequence across the characteristic calcium-binding and putative polypeptide binding regions of LipL32 is conserved in the two proteins (Hauk et al., 2009). This biochemical information suggests that PtlL32 is an ECM-binding protein, however the biological function and importance for P. tunicata is not established. Moreover prior to the identification of this LipL32 ortholog in P. tunciata, it was widely believe that LipL32 proteins were unique to pathogenic Leptospira spp. (Murray, 2013), raising the question as to the origin of PtlL32 and its' prevalence in other environmental bacteria. Here we use a combination of allelic exchange mutagenesis, attachment assays, colonization experiments, and phylogenetic analysis to demonstrate a role for this conserved lipoprotein in facilitating bacterial interaction with host surfaces and provide evidence that suggests LipL32-proteins may have been acquired via horizontal gene transfer from an environmental origin. This study provides the first experimental evidence for a function of LipL32-like proteins outside of the Leptospira genus and builds upon our current understanding of the traits that drive host colonization in marine bacteria.

Materials and methods

Allelic exchange and complementation of p. tunicata ptlL32

A P. tunicata ptlL32 allelic replacement mutant strain was generated using the Gene Splicing by Overlap Extension (SOE) PCR strategy (Horton, 1995) coupled with bi-parental conjugation and homologous recombination as described previously for the mutagenesis of P. tunicata (Egan et al., 2002; Mai-Prochnow et al., 2004). Briefly, the first section of the ptlL32 gene was amplified from wild type (WT) genomic DNA with primers, first-forward, 5′ ATG AAA ATC AAA CTG GTC GTG G 3′; and first-reverse, 5′ CTG GTT TCG CTA AAT CAC CCA C 3′. In a separate PCR reaction, the second section was amplified with primers, second-forward, 5′ CAG ACA AAT TAA AAG CCG ATA AAG; and second-reverse, 5′ TTA TTT ATT GAC TGC TTT ATG TAA C 3′. A kanamycin resistance (kanR) cassette was amplified from the plasmid pACYC177 (Table 1) using the following primers: kanR forward, 5′ GAT TTA TTC AAC AAA GCC ACG 3′; kanR reverse, 5′ ATT TAT TCA ACA AAG CCG CC 3′. A recombinant ptlL32 knockout fragment (ptlL32::kanR) was constructed using SOE-PCR (Horton, 1995) by “PCR splicing” the overhangs on the first and second PCR products onto the 5′ and 3′ ends of the kanR cassette, respectively. Following PCR amplification of ptlL32::kanR using the first-forward and second-reverse primers, the fragment was introduced into the EcoRI site of the suicide vector pGP704 (Table 1) (Miller and Mekalanos, 1988) to generated the vector pLP704. Standard electroporation techniques (Ausubel et al., 1994) were used to transfer pLP704 into E. coli SM10. The P. tunicata ΔptlL32 strain was constructed using allelic exchange by conjugation of the recombinant E. coli SM10 pLP704 strain with P. tunicata WT (strR) (Table 1) (according to the method described in Egan et al., 2002). Exconjugants with the ptlL32::kanR fragment inserted into the chromosome by homologous recombination were selected using VNSS (Marden et al., 1985) agar plates supplemented with streptomycin (200 μg ml−1) and kanamycin (85 μg ml−1). PCR confirmation of the recombination event was performed with a forward primer that target a region upstream of ptlL32 in the WT chromosome, 5′ AAG CAT CCA GTG TGC AGT CG 3′, and the kanR reverse primer.

Table 1.

Plasmids and bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype# | References |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| SM10 λ pir | RP4-2-Tc::Mu, π replicase (pir); strs kans | Simon et al., 1983 |

| SM10 pLP704 | pGP704:: ptlL32::kanR amp | This study |

| SM10 pBBR1L | pBBR1 MCS5::ptlL32 gen | This study |

| SM10 pCJS10 | pCJS10 cat | Dalisay et al., 2006 |

| P. tunicata D2 | ||

| WT strR | Spontaneously resistant to streptomycin | Egan et al., 2002 |

| GFP-labeled WT strR | pCJS10 cat strR | Dalisay et al., 2006 |

| ΔptlL32 | ptlL32 knockout mutant; strR, ptlL32::kanR amp | This study |

| CΔptlL32 | Complemented ptlL32 knockout mutant; str, ptlL32::kanR amp; pBBR1 MCS5ptlL32 gen | This study |

| GFP-labeled ΔptlL32 | strR, ptlL32 knockout mutant; ptlL32::kanR amp; pCJS10 cat | This study |

| PLASMIDS | ||

| pBBR1 MCS5 | Broad host range mobilizable vector, gen | Kovach et al., 1995 |

| pBBR1 MCS5::ptlL32 | Complementation vector containing intact ptlL32 | This study |

| pCJS10-GFP | RSF1010 broad host range backbone, gfpmut3, cat | Rao et al., 2005 |

| pGP704 | Suicide vector, R6K ori, mob, amp | Miller and Mekalanos, 1988 |

| pLP704 | pGP704 with ptlL32::kanR knockout fragment | This study |

| pACYC177 | Cloning vector, amp kanR | Chang and Cohen, 1978 |

strS, streptomycin sensitive; kanS, kanamycin sensitive; strR, streptomycin resistance; kanR, kanamycin resistance; tet, tetracyclin resistance; amp, ampicillin resistance; cat chloramphenicol resistance; gen, gentamycin resistance.

To complement the ΔptlL32 strain, the ptlL32 gene and surrounding potential promoter and terminator regions was amplified from WT genomic DNA with primers: WT forward, 5′ GCA ATA GCT TTC TTT GTT CCT C 3′; WT reverse, 5′ GAC ACA TCA GCA TCA CTC AC 3′. The ptlL32 PCR product was ligated into the SmaI site of the broad host range plasmid, pBBR1 MCS5 (Kovach et al., 1995) to generate the complementation plasmid, pBBR1L. Standard electroporation was used to transfer pBBR1L into an E. coli SM10 donor strain (Ausubel et al., 1994), before bi-parental conjugation of the donor strain with P. tunicata ΔptlL32 as described previously (Egan et al., 2002). P. tunicata ΔptlL32 ex-conjugants with ptlL32 complemented in trans were selected for on VNSS agar plates supplemented with gentamycin (50 μg ml−1), kanamycin and streptomycin, and verified by PCR using the WT forward primer, and the gen resistance cassette reverse primer 5′ GCGGCGTTGTGACAATTT 3′. The confirmed complemented ΔptlL32 strain was named CΔptlL32.

Bacterial attachment to polystyrene and matrigel™ basement membrane matrix

The attachment of P. tunicata ΔptlL32 to polystyrene was compared to the WT using a cell adhesion assay. The bacterial strains were grown at 28°C for 24 h shaking in VNSS supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (Table 1). The cell suspension was centrifuged (6000 × g, 5 min), washed twice and resuspended in 1 ml of sterile NSS (Marden et al., 1985) at Abs600 nm = 1 (~109 CFU ml−1). Fifty microliters of cell suspension for each strain was added to triplicate wells of a polystyrene Costar® 96 well plate (Corning™). The plate was incubated for 6 h at 28°C with gentle shaking before non-adherent cells were removed by rinsing the wells six times with sterile PBS. Twenty-five microliters of a 200 μg ml−1 solution of trypsin were added to each well and the plate incubated at 37°C for 5 min to allow for cell detachment. Detached cells were then counted by dark field microscopy in a Helber™ bacterial counting chamber (Hawksley, Sussex, UK). Attached bacteria from a total 80 small squares (chosen based on the results of a random number generator) on the counting chamber were enumerated for each of the replicates. The experiment was performed in triplicate for each strain on three independent days. Statistical analysis was performed using SYSTAT 13 (SYSTAT Software Inc., USA) and significance was assessed using an unpaired Students two-tailed t-test.

To assess the attachment of ΔptlL32 to ECM, the assay outlined above was modified according to the protocol described in Hoke et al. (2008). The ECM preparation used in this study, BD Matrigel™ Basement Membrane Matrix (BD Biosciences, USA), is derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma cells, and is composed mainly of laminin, entactin, collagen, and mammalian growth factors (Vukicevic et al., 1992; Hughes et al., 2010). The wells of a 96 well plate were coated with 50 μL of BD Matrigel™ and incubated at 4°C overnight. The wells were then washed three times with PBS to remove excess ECM. The P. tunicata bacterial strains (Table 1) were grown, washed, and resuspended as described for the polystyrene adhesion experiment above. Fifty microliters of cell suspension for each strain was added to triplicate wells of a plate coated with BD Matrigel™, and incubated for 2 and 6 h at 28°C with gentle shaking. Non-adherent cells were then removed and detached cells enumerated as described for the polystyrene adhesion experiment. Significance was assessed using a One Way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Bacterial attachment to u. australis

To assess the adhesion of P. tunicata ΔptlL32 to a living host surface an attachment assay to U. australis was performed as described previously (Dalisay et al., 2006). The U. australis samples were collected from Clovelly Bay, Sydney Australia and processed immediately. The algal samples were rinsed four times with 50 ml of autoclaved seawater and thallus sections of approximately 6 mm were excised from the mid thalli using a sterile scalpel. The algal surface was then cleaned to remove the majority of epiphytic bacteria. Briefly individual samples were swabbed with sterile cotton tips, containing 0.012% NaOCl for 5 min, and incubated for 24 h in an antibiotic mixture that consisted of ampicillin (300 μg ml−1), polymyxin (30 μg ml−1), and gentamycin (60 μg ml−1). The alga thalli were then incubated for 1 h in 50 ml of 0.2 μm filtered-seawater to remove residue chemicals.

P. tunicata ΔptlL32 was labeled with green florescent protein (GFP) by introducing the broad host range plasmid pCJS10 as described previously for the WT strain (Dalisay et al., 2006) using bi-parental conjugation with an E. coli SM10 donor strain (Egan et al., 2002) (Table 1). GFP-labeled ΔptlL32 ex-conjugants were grown on VNSS agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (18 μg ml−1) and confirmed by visual inspection under the GFP filter cube of an epifluorescence microscope (DM-LB Leica). For the U. australis attachment assays, GFP tagged WT (Dalisay et al., 2006) and ΔptlL32 (Table 1) were grown in VNSS supplemented with chloramphenicol for 24 h at 28°C with shaking. One milliliter of culture was harvested by centrifugation (6000 × g, 2 min), washed three times with NSS, and resuspended at an Abs600 nm of 0.3. A single thallus section was placed in a well of a 6 well plate (Corning™) containing 1 ml PBS and 1 ml of bacterial culture, and incubated for 6 h with gentle shaking.

After 6 h incubation the algal samples were rinsed three times in 2 ml PBS to remove loosely attached cells and visualized immediately using a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (Olympus Fluoview FV1000) under 40× oil magnification and 488 nm excitation. Seven images were taken randomly across each sample and the images were analyzed using ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012). The number of GFP-fluorescing cells attached to the surface of the algae per mm2 was quantified using the “analyze particles” function in ImageJ and the results were plotted using GraphPad Prism 6. In addition the number of microcolonies was manually counted (where >10 cells clustered together was classified as a microcolony) and the results plotted using GraphPad Prism 6. The assay was replicated four times in triplicate for each bacterial strain and data analyzed as described for the polystyrene adhesion experiment.

Sequence retrieval and protein alignment of ptlL32 orthologs

Bacterial genomes were searched for orthologs to the P. tunicata gene PtlL32 using a blastp search tool of both the UniProt database (http://www.uniprot.org/) and the non-redundant database of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in April 2014 (Altschul et al., 1990). All non-Leptospira orthologs with greater than 40% amino acid sequence identity to PtlL32 from P. tunicata (Table 2) and a further five sequences from representative Leptospira species were selected (L. interrogans, ADJ95774; L. kirschneri, AAF60198; L. broomii, EQA47312; L. borgpetersenii, ABJ79303; L. santarosai, AAS21795). All sequences were aligned with ClustalX using the default parameters (Larkin et al., 2007) and the resulting alignment curated with Gblocks to remove gap positions (Talavera and Castresana, 2007). The resulting alignment of 102 amino acid positions was then subject to maximum-likelihood analysis using PhyML 3.0 with the default LG substitution model and 100 bootstraps (Criscuolo, 2011). Trees were visualized using Dendroscope (Huson and Scornavacca, 2012). Information on the phylogeny and isolation of bacterial strains was obtained from published data and using the genome browser in the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) browser (https://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/er/main.cgi) in April 2014 (Markowitz et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Characteristics of non-Leptospira species that possess orthologs of LipL32.

| NCBI accession | Bacterial strain | Taxonomic affiliation | Isolation source |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAR27184 | Pseudoalteromonas tunicata | C: Gammaproteobacteria | Surface of the macroalga Ulva spp. (Australia) and the invertebrate Ciona intestinalis (Sweden) |

| O: Alteromondales | |||

| F: Pseudoalteromonadaceae | |||

| ERG54672 | Pseudoalteromonas spongiae | As above | Surface of the sponge Mycale adhaerens in Hong Kong |

| ERG42655 | Pseudoalteromonas rubra | As above | Mediterranean seawater of the coast of France |

| ESP92640 | Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea | As above | Surface of the coral Montastrea annularis in reef water off the coast of Florida, USA |

| ADZ89577 | Marinomonas mediterranea | C: Gammaproteobacteria | Mediterranean seawater from the southeastern coast of Spain |

| O: Oceanospirillaceae | |||

| F: Oceanospirillales | |||

| EDM65737 | Moritella sp. PE36 | C: Gammaproteobacteria | Deep ocean waters of the Pacific Ocean San Diego, USA |

| O: Alteromondales | |||

| F: Moritellaceae | |||

| ADV49486 | Cellulophaga algicola | P: Bacteroidetes | Surface of a sea ice-chain forming pennate diatom, Melosira sp. in the Eastern Antarctic coastal zone |

| C: Flavobacteria | |||

| O: Flavobacteriales | |||

| F: Flavobacteriaceae | |||

| ADY29818 | Cellulophaga lytica | As above | Beach mud in Limon, Costa Rica |

| CDF79332 | Formosa agariphila | As above | Surface of the green alga Acrosiphonia sonder isolated from the Sea of Japan |

| EDM44616 | Ulvibacter sp. SCB49 | P: Bacteridetes | Surface waters of the Pacific Ocean Southern California Bight, USA |

| C, O, F: Unclassified | |||

| AEE17958 | Treponema brennaborense | P: Spirochaetes | Ulceritive skin lesion on a bovine foot infected with digital dermatitis, Germany |

| C: Spirochaetia | |||

| O: Spirochaetales | |||

| F: Spirochaetaceae |

Results and discussion

PtlL32 is not required for attachment to abiotic surfaces, however contributes to the attachment of p. tunicata to host surfaces

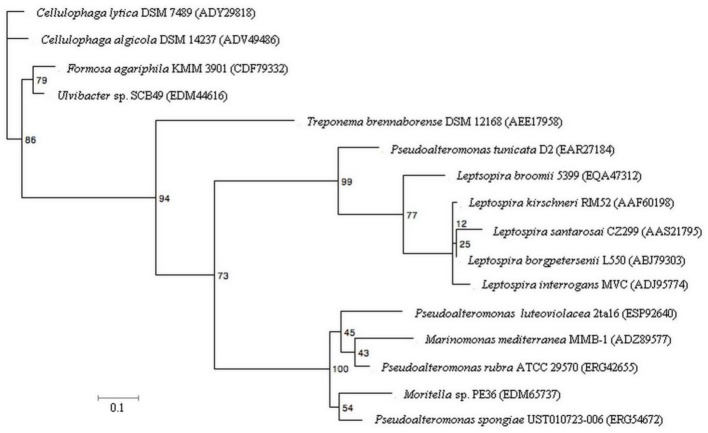

To investigate the role of ptlL32 in attachment to abiotic surfaces a ptlL32 knock-out mutant (ΔptlL32) was constructed and was compared to the WT P. tunicata strains for its ability to adhere to a polystyrene surface. After 6 h incubation there was no significant difference (p > 0.8) between the number of cells attached for the ΔptlL32 strain compared to WT (Figure 1). These data demonstrate that a mutation in ptlL32 has no immediate impact on the ability of P. tunicata to attach to abiotic surfaces.

Figure 1.

Attachment of P. tunicata WT (solid fill) and ΔptlL32 (vertical stripes) to a polystyrene well plate after 6 h of incubation. The numbers of cells attached per mm3 were determined using direct counts of detached bacteria in a Helber bacterial counting chamber. Significance was assessed using the Students unpaired, two-tailed t-test (p > 0.8). Error bars represent standard deviation.

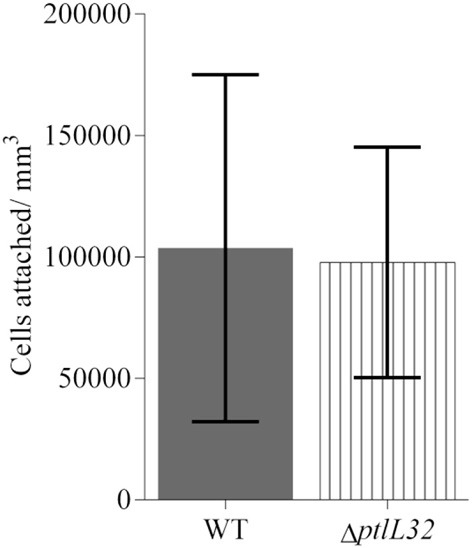

Attachment of the P. tunicata ΔptlL32 strain to ECM structures was also compared to WT and CΔptlL32, at times that have been characterized as early (2 h) and late (6 h) stages of irreversible attachment in other bacterial species (Hinsa et al., 2003; Palmer et al., 2007; Li et al., 2012). Figures 2A,B show the average numbers of cells attached per mm3 for the three strains after 2 and 6 h, respectively. The mutant strain ΔptlL32 exhibited 10-fold reduction (p < 0.001) in attachment compared to WT after both 2 and 6 h. There was also a clear increase in attached cells over time for the WT, but not for the mutant strain (ΔptlL32) (Figure 2). Complementation of ptlL32 in trans (strain CΔptlL32) restored the WT phenotype, excluding polar effects of the knock-out mutant. Together with the observations that mutations in ptlL32 had no effect on attachment of P. tunicata to abiotic surfaces (Figure 1), these data show that Ptlp32 contributes specifically to the ability of P. tunicata to adhere to complex biological surfaces.

Figure 2.

Attachment to Matrigel™ after 2 h (A) and 6 h (B) for ΔptlL32 (horizontal stripes) compared to WT (solid fill) and C ΔptlL32 (small squares). The number of cells attached per mm3 for each strain was estimated using direct counts of detached bacteria in a Helber bacterial counting chamber. Averages are shown as columns with n = 9. Error bars represent standard deviation. *Indicates significance with a p < 0.001 using an ANOVA.

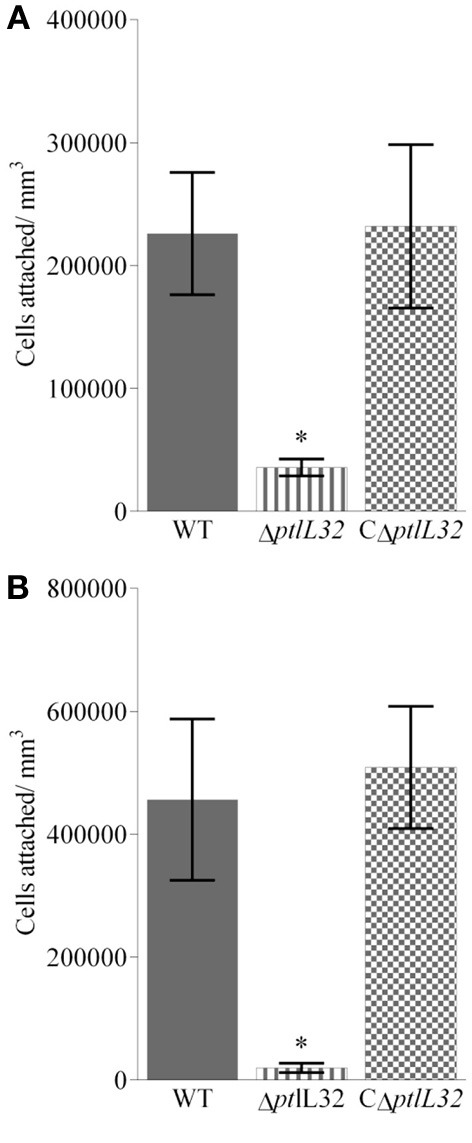

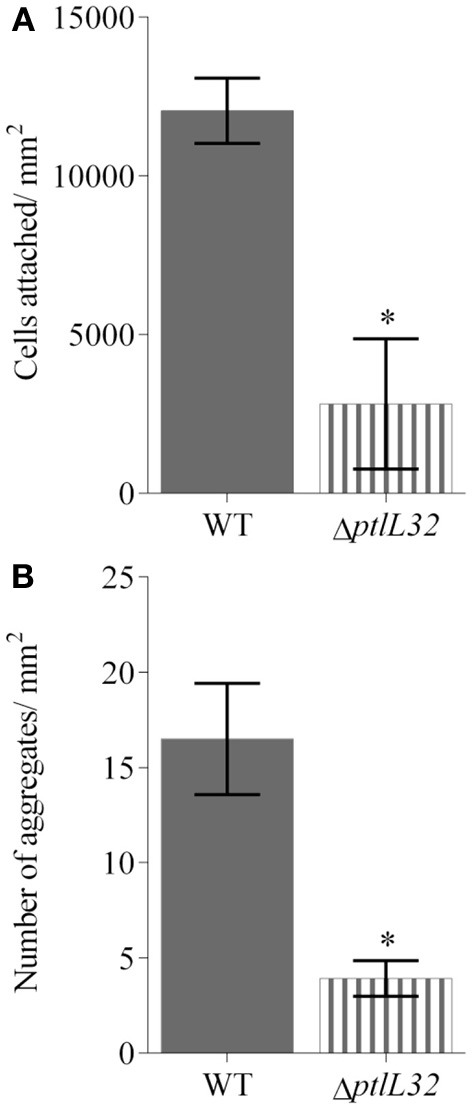

Bacterial colonization of various marine eukaryotes has been demonstrated in other non-algal systems to be mediated by surface-specific adhesins (Mueller et al., 2007; Bulgheresi et al., 2011; Stauder et al., 2012); and we hypothesize that PtlL32 may facilitate adhesion to ECM-like surfaces in the marine environment, including, but not limited to, its natural host U. australis. To further explore this role we assessed the ability of ΔptlL32 and the WT P. tunicata strains to attach to the surface of U. australis. P. tunicata ΔptlL32 demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of cells attached to the surface of the alga (Figures 3, 4A) compared to WT cells (p < 0.001). A reduction in the number of cell aggregates on the surface of U. australis in the mutant strain (Figure 4B; p < 0.001) also indicates that biofilm maturation may be impaired. The reduced attachment of ΔptlL32 cells to the surface of the alga compared to WT suggests that PtlL32 may bind to specific host cell wall components. The major cell wall matrix components for Ulva species are cellulose and ulvan (Lahaye and Robic, 2007), however the structural details are unknown (Lahaye and Kaeffer, 1997; Robic et al., 2009). Genetic analysis of U. linza identified genes involved in the synthesis of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins, including collagen (Stanley et al., 2005), which are homologous to components in the ECM preparation used above (Hughes et al., 2010). Leptospira LipL32 has also been shown to bind a number of proteins, including different types of collagen (Hauk et al., 2008; Hoke et al., 2008; Chaemchuen et al., 2011). Therefore, the reduced adhesion of ΔptlL32 to both ECM and U. australis may be the result of interaction of PtlL32 with host proteins, including different forms of collagen.

Figure 3.

Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of GFP-labeled WT (A) and GFP-labeled ΔptlL32 (B) attached to the surface of U. australis. Green fluorescent cells were enumerated using ImageJ software. Images were captured using a FV1000 confocal laser-scanning microscope. Scale bar represents 20 μm.

Figure 4.

Average number of cells attached to (A), and cell aggregates (defined as a tight cluster of >10 cells) (B) on U. australis for GFP-labeled WT (solid fill) and GFP-labeled ΔptlL32 (horizontal stripes) after 6 h incubation. The number of green fluorescing cells or aggregates in each field of view was counted using ImageJ and an average expressed for cells per mm2. Error bars represent standard deviation. Error bars represent standard deviation at 45 replicates and * denotes a significant difference with a p < 0.001 using the unpaired Students two-tailed t-test.

The observation that PtlL32 mediates colonization only on biotic surfaces stands in contrast to what has been observed for the MSHA-like pili, which mediates adhesion to both biotic and abiotic surfaces (Dalisay et al., 2006). Changes in the membrane proteome of P. tunicata between cells grown on either BSA-coated or ECM-coated surfaces have recently been observed (Hoke et al., 2011) and therefore it is likely that P. tunicata utilizes a distinct subset of proteins to adhere to different surfaces. Thus the available data suggests a conserved function for LipL32-like proteins in facilitating interaction with ECM structures (Hauk et al., 2008; Hoke et al., 2008), a novel finding given the absence of an overlapping niche between P. tunicata and Leptospira species.

PtlL32 orthologs have a patchy distribution across specific groups of environmental bacteria

Given that PtlL32 is important for mediating host colonization in P. tunicata we sought to determine the distribution and relationship of orthologous proteins across other non-Leptospira organisms. In silico analysis of publically available bacterial genomes revealed sequences similar to PtlL32 in eleven other species, of which five were isolated from eukaryotic hosts, ten are marine bacteria and only the spirochete Treponema brennaborense has been associated with disease (Table 2). This distribution is interesting considering that until relatively recently LipL32-like proteins were thought to be unique to pathogenic Leptospira (Hoke et al., 2008; Murray, 2013). Given the untapped bacterial diversity in environmental ecosystems these data further suggest that the distribution of LipL32 orthologs may be greater still.

Multiple alignment of the protein sequences revealed a total of 29 amino acids positions that are fully conserved across all sequences; with increased conservation of amino acids at positions 85–107 (Supplementary Material). The regions of sequence conservation also include components of the protein that are postulated to mediate binding of host structures in Leptospira, including the polypeptide binding function located in the C-terminal (Supplementary Material, amino acids 188–272) (Hauk et al., 2008; Hoke et al., 2008) and an acidic loop at amino acids 164–178 (AKPVQKLDDDDDGDD) (Hauk et al., 2009; Vivian et al., 2009). These regions of amino acid conservation were previously highlighted in the crystal structures of three non-Leptospira LipL32 proteins for their potential role in conferring similar binding properties to the orthologous proteins (Hauk et al., 2009; Vivian et al., 2009).

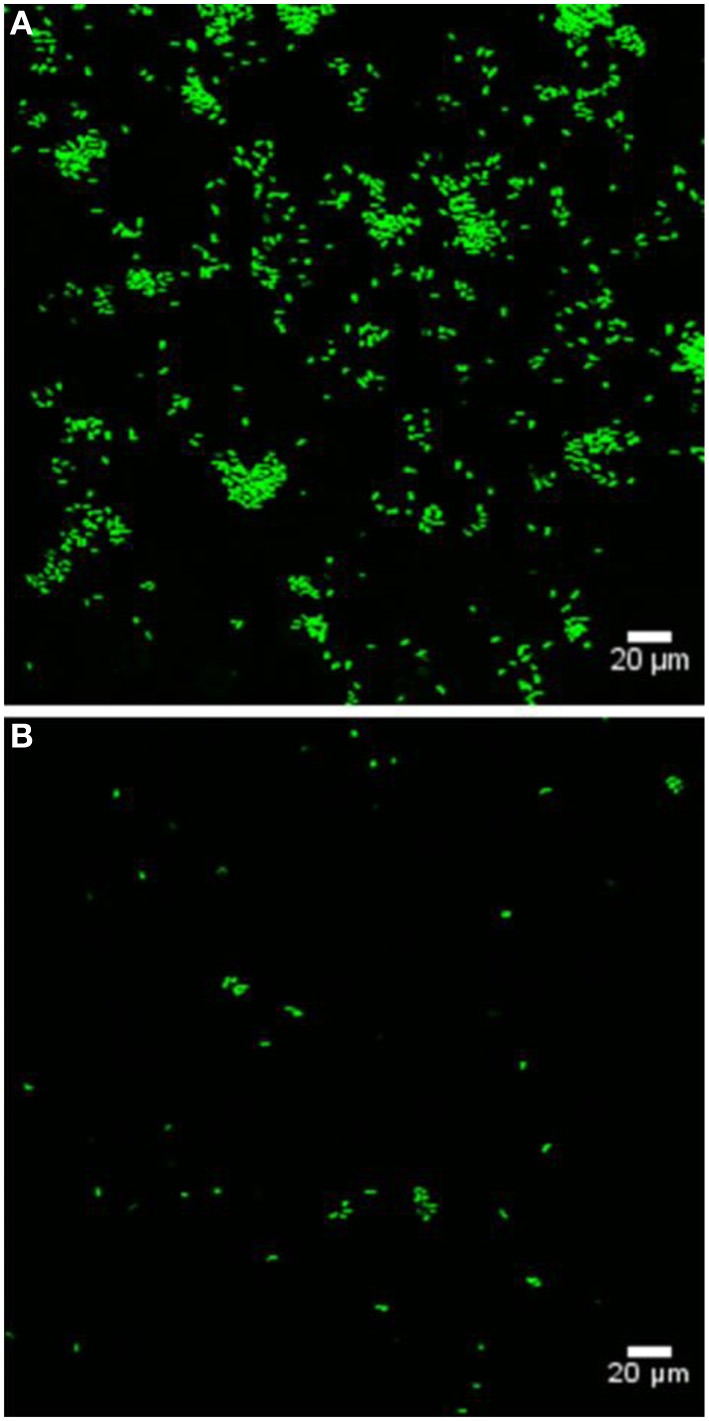

Analysis of the phylogenetic relationship between the PtlL32 orthologs provides new insight into its evolutionary origins. Most striking is the observation that the P. tunicata sequence clusters with the Leptospira and not with those from other Pseudoalteromonas species or Gammaproteobacteria (Figure 5). Likewise, a PtlL32 ortholog of T. brennaborense (phylum Spirochaetes) does not cluster with the other members of the Spirochaetes (i.e., Leptospira spp.) (Figure 5, Table 2). This clustering of LipL32 sequences outside of their taxonomic relatives is in support of an acquisition via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and/ or maintenance only in the pathogenic Leptospira and a selected group of environmental organism. In support of this theory, an examination of the GC content of the lipL32 genes revealed a deviation from the genomic GC content in examples of Leptospira lipL32 genes, but not in the non-Leptospira orthologs. Given the diversity of the ecosystems in which many of the LipL32 containing strains are found (Table 2) it possible that the Leptospira LipL32 has evolved from environmental strains, where it facilitates commensal interactions, to a role in pathogenic interaction with animals. This proposed “dual function” for LipL32 is in line with observations of other environmentally acquired pathogens, where certain colonization traits mediate pathogenesis in a host-associated context, whilst facilitating microbial survival and persistence in the environment (Casadevall et al., 2003; Vezzulli et al., 2008). Indeed an environmental origin of pathogenic Leptospira has also been recently suggested and is supported by observations that the closest orthologs to many hypothetical Leptospira genes are from environmental rather than pathogenic bacteria (Murray, 2013).

Figure 5.

Maximum-likelihood tree of PtlL32 and orthologous protein sequences in non-Leptospira species. Five representative Leptospira LipL32 sequences were included for comparison with the non-Leptospira sequence. NCBI GenBank accession numbers for each protein sequence is provided in brackets. Bootstrap values for 100 replicates are shown for each node. The scale bar represents 10% sequence divergence.

Conclusion

Understanding of the mechanisms that facilitate bacterial interactions with marine surfaces is poorly understood compared to that of medically relevant systems. Here we have begun to fill this knowledge gap by investigating the mechanisms that facilitate interactions between the marine bacterium P. tunciata with its macroalgal host. We found that a P. tunicata ΔptlL32 strain attached with a greatly reduced capacity to the biotic surfaces (Figures 2–4), a finding that is in line with previous reports indicating that the colonization of U. australis by P. tunicata involves multiple adhesins (Dalisay et al., 2006; Thomas et al., 2008). Having multiple mechanisms for adhesion may represent a means by which the bacterium can mediate host specificity and/or modify its interaction with the host in response to environmental variability. A degree of functional overlap has also been reported for adhesive structures in a diverse range of bacteria where the apparent redundancy may reflect the ability of these organisms to interact with multiple eukaryotic hosts or tissues (Ramey et al., 2004; Clarke and Foster, 2006; Rodriguez-Navarro et al., 2007; Pruzzo et al., 2008). For example, collagen is also a component of the ECM of the tunicate C. intestinalis (Vizzini et al., 2002), since P. tunicata has also been isolated from C. intestinalis it is possible that PtlL32 also has a function in mediating colonization to both macroalgae and marine invertebrates.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to investigate the function for a LipL32 ortholog in an organism outside the Leptospira species and the results speak to a conserved function for this protein in mediating association with host cell matrix components. Phylogenetic analysis suggests the Leptospira LipL32 was acquired from environmental bacteria and that LipL32 proteins act as “dual function” traits (Casadevall et al., 2003; Casadevall, 2006; Hoke et al., 2008; Murray, 2013) facilitating both pathogenic interactions by Leptospira spp. and host colonization by the environmental bacterium P. tunicata. This study therefore adds weight to the hypothesis presented by Egan et al. (2013a), that such dual function traits may facilitate interactions between bacteria and macroalgae; a relationship that has important implications for macroalgal health, as well as nutrient cycling, and homeostasis in the temperate ocean environment (Wahl et al., 2012; Egan et al., 2013b).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from the Australian Research Council and the Centre for Marine Bio-Innovation. We thank A/Prof. Torsten Thomas for his thoughtful discussions and revision of the draft manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00323/abstract

References

- Adler B., de la Pena Moctezuma A. (2010). Leptospira and leptospirosis. Vet. Microbiol. 140, 287–296 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler B., Lo M., Seemann T., Murray G. L. (2011). Pathogenesis of leptospirosis: the influence of genomics. Vet. Microbiol. 153, 73–81 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R., Moore R., Siedman J., Smith J., et al. (1994). Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons [Google Scholar]

- Bogino P. C., Oliva Mde L., Sorroche F. G., Giordano W. (2013). The role of bacterial biofilms and surface components in plant-bacterial associations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 15838–15859 10.3390/ijms140815838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgheresi S., Gruber-Vodicka H. H., Heindl N. R., Dirks U., Kostadinova M., Breiteneder H., et al. (2011). Sequence variability of the pattern recognition receptor Mermaid mediates specificity of marine nematode symbioses. ISME J. 5, 986–998 10.1038/ismej.2010.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C., Thomas T., Lewis M., Steinberg P., Kjelleberg S. (2011). Composition, uniqueness and variability of the epiphytic bacterial community of the green alga Ulva australis. ISME J. 5, 590–600 10.1038/ismej.2010.164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A. (2006). Cards of virulence and the global virulome for humans. Microbes 1, 359–364 [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A., Steenbergen J. N., Nosanchuk J. D. (2003). “Ready made” virulence and “dual use” virulence factors in pathogenic environmental fungi—the Cryptococcus neoformans paradigm. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 332–337 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00082-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaemchuen S., Rungpragayphan S., Poovorawan Y., Patarakul K. (2011). Identification of candidate host proteins that interact with LipL32, the major outer membrane protein of pathogenic Leptospira, by random phage display peptide library. Vet. Microbiol. 153, 178–185 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A. C. Y., Cohen S. N. (1978). Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134, 1141–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S. R., Foster S. J. (2006). Surface adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 51, 187–224 10.1016/s0065-2911(06)51004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscuolo A. (2011). morePhyML: improving the phylogenetic tree space exploration with PhyML 3. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 61, 944–948 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalisay D. S., Webb J. S., Scheffel A., Svenson C., James S., Holmström C., et al. (2006). A mannose-sensitive haemagglutinin (MSHA)-like pilus promotes attachment of Pseudoalteromonas tunicata cells to the surface of the green alga Ulva australis. Microbiology 152, 2875–2883 10.1099/mic.0.29158-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey S., Mohan C. M., Ramadass P., Nachimuthu K. (2007). Phylogenetic analysis of LipL32 gene sequence of different pathogenic serovars of Leptospira. Vet. Res. Commun. 31, 509–511 10.1007/s11259-007-3535-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S., Fernandes N. D., Kumar V., Gardiner M., Thomas T. (2013a). Bacterial pathogens, virulence mechanism and host defence in marine macroalgae. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 925–938 10.1111/1462-2920.12288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S., Harder T., Burke C., Steinberg P., Kjelleberg S., Thomas T. (2013b). The seaweed holobiont: understanding seaweed-bacteria interactions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 462–476 10.1111/1574-6976.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S., James S., Holmström C., Kjelleberg S. (2002). Correlation between pigmentation and antifouling compounds produced by Pseudoalteromonas tunicata. Environ. Microbiol. 4, 433–442 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S., Thomas T., Kjelleberg S. (2008). Unlocking the diversity and biotechnological potential of marine surface associated microbial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 219–225 10.1016/j.mib.2008.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N., Case R. J., Longford S. R., Seyedsayamdost M. R., Steinberg P. D., Kjelleberg S., et al. (2011). Genomes and virulence factors of novel bacterial pathogens causing bleaching disease in the marine red alga Delisea pulchra. PLoS Biol. 6:e27387 10.1371/journal.pone.0027387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachon C. M. M., Sime-Ngando T., Strittmatter M., Chambouvet A., Kim G. H. (2010). Algal diseases: spotlight on a black box. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 633–640 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecke F., Labes A., Wiese J., Imhoff J. F. (2010). Chemical interactions between marine macroalgae and bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 409, 267–299 10.3354/meps08607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haake D. A., Suchard M. A., Kelley M. M., Dundoo M., Alt D. P., Zuerner R. L. (2004). Molecular evolution and mosaicism of leptospiral outer membrane proteins involves horizontal DNA transfer. J. Bacteriol. 186, 2818–2828 10.1128/jb.186.9.2818-2828.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauk P., Guzzo C. R., Ramos H. R., Ho P. L., Farah C. S. (2009). Structure and calcium-binding activity of LipL32, the major surface antigen of pathogenic Leptospira sp. J. Mol. Biol. 390, 722–736 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauk P., Macedo F., Romero E. C., Vasconcellos S. A., de Morais Z. M., Barbosa A. S., et al. (2008). In LipL32, the major leptospiral lipoprotein, the C terminus is the primary immunogenic domain and mediates interaction with collagen and plasma fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 76, 2642–2650 10.1128/iai.01639-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsa S. M., Espinosa-Urgel M., Ramos J. L., O'Toole G. A. (2003). Transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 requires an ABC transporter and a large secreted protein. Mol. Microbiol. 49, 905–918 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoke D. E., Egan S., Cullen P. A., Adler B. (2008). LipL32 is an extracellular matrix-interacting protein of Leptospira spp. and Pseudoalteromonas tunicata. Infect. Immun. 76, 2063–2069 10.1128/iai.01643-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoke D. E., Zhang K., Egan S., Hatfaludi T., Buckle A. M., Adler B. (2011). Membrane proteins of Pseudoalteromonas tunicata during the transition from planktonic to extracellular matrix-adherent state. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3, 405–413 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollants J., Leliaert F., De Clerck O., Willems A. (2013). What we can learn from sushi: a review on seaweed-bacterial associations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 83, 1–16 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmström C., James S., Neilan B. A., White D. C., Kjelleberg S. (1998). Pseudoalteromonas tunicata sp. nov., a bacterium that produces antifouling agents. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48, 1205–1212 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton R. M. (1995). PCR-mediated recombination and mutagenesis. SOEing together tailor-made genes. Mol. Biotechnol. 3, 93–99 10.1007/bf02789105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C. S., Postovit L. M., Lajoie G. A. (2010). Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics 10, 1886–1890 10.1002/pmic.200900758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H., Scornavacca C. (2012). Dendroscope 3: an interactive tool for rooted phylogenetic trees and networks. Syst. Biol. 61, 1061–1067 10.1093/sysbio/sys062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley-Jones J., Robertson D. L., Boot-Handford R. P. (2007). On the origins of the extracellular matrix in vertebrates. Matrix Biol. 26, 2–11 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline K. A., Falker S., Dahlberg S., Normark S., Henriques-Normark B. (2009). Bacterial adhesins in host-microbe interactions. Cell Host Microbe 5, 580–592 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Steven Hill D., Robertson G. T., Farris M. A., Roop Ii R. M., et al. (1995). Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166, 175–176 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachnit T., Meske D., Wahl M., Harder T., Schmitz R. (2011). Epibacterial community patterns on marine macroalgae are host-specific but temporally variable. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 655–665 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye M., Kaeffer B. (1997). Seaweed dietary fibres: structure, physico-chemical and biological properties relevant to intestinal physiology. Sci. Aliments 17, 563–584 [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye M., Robic A. (2007). Structure and functional properties of Ulvan, a polysaccharide from green seaweeds. Biomacromolecules 8, 1765–1774 10.1021/bm061185q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levett P. N. (2001). Leptospirosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 296–326 10.1128/cmr.14.2.296-326.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Brown P. J. B., Tang J. X., Xu J., Quardokus E. M., Fuqua C., et al. (2012). Surface contact stimulates the just-in-time deployment of bacterial adhesins. Mol. Microbiol. 83, 41–51 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07909.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longford S. R., Tujula N. A., Crocetti G. R., Holmes A. J., Holmström C., Kjelleberg S., et al. (2007). Comparisons of diversity of bacterial communities associated with three sessile marine eukaryotes. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 48, 217–229 10.3354/ame048217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mai-Prochnow A., Evans F., Dalisay-Saludes D., Stelzer S., Egan S., James S., et al. (2004). Biofilm development and cell death in the marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 3232–3238 10.1128/aem.70.6.3232-3238.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marden P., Tunlid A., Malmcrona-Friberg K., Odham G., Kjelleberg S. (1985). Physiological and morphological changes during short term starvation of marine bacterial isolates. Arch. Microbiol. 142, 326–332 10.1007/BF00491898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz V. M., Mavromatis K., Ivanova N. N., Chen I. M., Chu K., Kyrpides N. C. (2009). IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 25, 2271–2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller V. L., Mekalanos J. J. (1988). A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170, 2575–2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller R. S., McDougald D., Cusumano D., Sodhi N., Kjelleberg S., Azam F., et al. (2007). Vibrio cholerae strains possess multiple strategies for abiotic and biotic surface colonization. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5348–5360 10.1128/jb.01867-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G. L. (2013). The lipoprotein LipL32, an enigma of leptospiral biology. Vet. Microbiol. 162, 305–314 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G. L., Srikram A., Hoke D. E., Wunder E. A., Jr., Henry R., Lo M., et al. (2009). Major surface protein LipL32 is not required for either acute or chronic infection with Leptospira interrogans. Infect. Immun. 77, 952–958 10.1128/iai.01370-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J., Flint S., Brooks J. (2007). Bacterial cell attachment, the beginning of a biofilm. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34, 577–588 10.1007/s10295-007-0234-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova O. E., Sauer K. (2012). Sticky situations: key components that control bacterial surface attachment. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2413–2425 10.1128/jb.00003-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruzzo C., Vezzulli L., Colwell R. R. (2008). Global impact of Vibrio cholerae interactions with chitin. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1400–1410 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey B. E., Koutsoudis M., von Bodman S. B., Fuqua C. (2004). Biofilm formation in plant-microbe associations. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7, 602–609 10.1016/j.mib.2004.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D., Webb J. S., Kjelleberg S. (2005). Competitive interactions in mixed-species biofilms containing the marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 1729–1736 10.1128/aem.71.4.1729-1736.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D., Webb J. S., Kjelleberg S. (2006). Microbial colonization and competition on the marine alga Ulva australis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5547–5555 10.1128/aem.00449-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robic A., Bertrand D., Sassi J. F., Lerat Y., Lahaye M. (2009). Determination of the chemical composition of ulvan, a cell wall polysaccharide from Ulva spp. (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) by FT-IR and chemometrics. J. Appl. Phycol. 21, 451–456 10.1007/s10811-008-9390-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Navarro D. N., Dardanelli M. S., Ruiz-Sainz J. E. (2007). Attachment of bacteria to the roots of higher plants. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 272, 127–136 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R., Priefer U., Pühler A. (1983). A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram Negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1, 784–791 10.1038/nbt1183-784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M. S., Perry R. M., Callow J. A. (2005). Analysis of expressed sequence tags from the green alga Ulva linza (Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 41, 1219–1226 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00138.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stauder M., Huq A., Pezzati E., Grim C. J., Ramoino P., Pane L., et al. (2012). Role of GbpA protein, an important virulence-related colonization factor, for Vibrio cholerae's survival in the aquatic environment. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 4, 439–445 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G., Castresana J. (2007). Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst. Biol. 56, 564–577 10.1080/10635150701472164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thole S., Kalhoefer D., Voget S., Berger M., Engelhardt T., Liesegang H., et al. (2012). Phaeobacter gallaeciensis genomes from globally opposite locations reveal high similarity of adaptation to surface life. ISME J. 6, 2229–2244 10.1038/ismej.2012.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T., Evans F. F., Schleheck D., Mai-Prochnow A., Burke C., Penesyan A., et al. (2008). Analysis of the Pseudoalteromonas tunicata genome reveals properties of a surface-associated life style in the marine environment. PLoS Biol. 3:e3252 10.1371/journal.pone.0003252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tujula N. A., Crocetti G. R., Burke C., Thomas T., Holmström C., Kjelleberg S. (2010). Variability and abundance of the epiphytic bacterial community associated with a green marine Ulvacean alga. ISME J. 4, 301–311 10.1038/ismej.2009.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli L., Guzman C. A., Colwell R. R., Pruzzo C. (2008). Dual role colonization factors connecting Vibrio cholerae's lifestyles in human and aquatic environments open new perspectives for combating infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 254–259 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivian J. P., Beddoe T., McAlister A. D., Wilce M. C. J., Zaker-Tabrizi L., Troy S., et al. (2009). Crystal structure of LipL32, the most abundant surface protein of pathogenic Leptospira spp. J. Mol. Biol. 387, 1229–1238 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzini A., Arizza V., Cervello M., Cammarata M., Gambino R., Parrinello N. (2002). Cloning and expression of a type IX-like collagen in tissues of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1577, 38–44 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00403-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukicevic S., Kleinman H. K., Luyten F. P., Roberts A. B., Roche N. S., Reddi A. H. (1992). Identification of multiple active growth-factors in basement-membrane Matrigel suggests caution in interpretation of cellular-activity related to extracellular-matrix components. Exp. Cell Res. 202, 1–8 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90397-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl M., Goecke F., Labes A., Dobretsov S., Weinberger F. (2012). The second skin: ecological role of epibiotic biofilms on marine organisms. Front. Microbiol. 3:292 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.