Abstract

Diabetes is a progressive disease that often leads to microvascular complications. This study investigates the impact of diabetes on microvessel permeability under basal and inflammatory conditions. Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats were used to mimic type 1 diabetes. Parallel experiments were conducted in intact mesenteric venules in normal rats and diabetic rats experiencing hyperglycemia for 2–3 wk. Microvessel permeability was determined by measuring hydraulic conductivity (Lp). The correlated changes in endothelial intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), adherens junctions, and cytoskeleton F-actin were examined with fluorescence imaging. Diabetic vessels showed moderately increased basal Lp, but upon platelet-activating factor (PAF) exposure, these vessels showed an ∼10-fold higher Lp increase than the normal vessels. Concomitantly, we observed higher increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i, enhanced stress fiber formation, vascular endothelial-cadherin separation, and larger gap formation between endothelial cells than those occurring in normal vessels. PAF receptor staining showed no significant difference between normal and diabetic vessels. The application of Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 did not affect PAF-induced increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i but significantly reduced PAF-induced Lp increases by 90% in diabetic vessels. The application of both Y27632 and nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor attenuated PAF-induced Lp increases more than using one inhibitor alone. Our studies indicate that diabetic conditions prime endothelial cells into a phenotype with increased susceptibility to inflammation without altering receptor expression and that the increased Rho activation and NO production play important roles in exaggerated permeability increases when diabetic vessels were exposed to inflammatory mediators, which may account for the exacerbated vascular dysfunction when diabetic patients are exposed to additional inflammation.

Keywords: endothelial [Ca2+]i, hyperglycemia, endothelial gap formation, stress fiber, nitric oxide

diabetes, one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the world, often leads to vascular complications, such as peripheral vascular diseases, retinopathy, neuropathy, and renal dysfunction (7, 12, 13). Despite great progress in our understanding of diabetes, the critical mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of vascular complications remain unclear. A growing body of literature indicates that exaggerated inflammation commonly occurs when diabetic patients have an infection, and edema-associated organ infection is a marker of poor outcome for stroke, postischemia, and wound healing in both human and experimental diabetes (5, 15, 26, 28, 29). There is increasing evidence to indicate that microvessels are severely affected in multiple organs in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes (4, 10), and endothelial barrier dysfunction plays an important role in the progression of diabetes-associated vascular complications (4, 8, 23). Although changes in microvessel permeability have been studied extensively in the vasculature of different organs in diabetic animals, most permeability changes were determined by assessing the leakage of systemically injected, fluorescently labeled macromolecules or the accumulation of Evans blue tracer at vascular walls. These methods cannot usually differentiate between changes in microvessel permeability, flux changes caused by changing flow dynamics, and changes in the surface area available for water and solute exchange. This is particularly important since hemodynamic variations are commonly associated with diabetes and inflammation. In the present study, a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rat model was used to mimic insulin-deficient type 1 diabetes, and the permeability coefficients of individually perfused intact diabetic vessels were measured under basal and inflammatory conditions. Platelet-activating factor (PAF), with well-characterized microvascular responses in normal rat vessels (1, 2, 24, 37, 39, 42), was used as a representative inflammatory mediator for acute stimulation. This study provides a quantitative assessment of the permeability properties of microvessel walls under STZ-induced diabetic conditions. We also investigated the correlated changes in endothelial cell signaling, stress fiber formation, and junctions between endothelial cells. Parallel experiments were conducted in individually perfused venules in the mesentery of normal rats and diabetic rats that had been experiencing hyperglycemia for 2–3 wk. Microvessel permeability was determined by measuring hydraulic conductivity (Lp). The correlated changes in endothelial Ca2+ signaling, endothelial cell adherens junctions, and cytoskeleton F-actin in the microvessel walls were examined using either conventional or confocal fluorescence imaging. The involvement of Rho-dependent pathways and their relationship with endothelial Ca2+ and nitric oxide (NO) in the regulation of microvessel permeability under diabetic conditions were also investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation.

Experiments were carried out on female Sprague-Dawley rats (2–3 mo old, 220–250 g; Hilltop Lab Animals, Scottdale, PA). All procedures and animal use were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) at West Virginia University and adhered to the American Physiological Society's Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Vertebrate Animals in Research and Training. Pentobarbital sodium was used for anesthesia, given subcutaneously. The initial dosage was 65 mg/kg body wt with an additional 3 mg/dose given as needed. A midline surgical incision (1.5–2 cm) was made in the abdominal wall. The mesentery was gently moved out of the abdominal cavity and spread over a pillar for Lp measurements or over a glass coverslip attached to an animal tray for confocal imaging and measurement of endothelial intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). The upper surface of the mesentery was superfused continuously with mammalian Ringer solution at 37°C.

STZ-induced diabetes.

Diabetes was induced in female Sprague-Dawley rats (2–3 mo old) by a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of STZ dissolved in citrate buffer (60 mg/kg body wt). Animals were considered diabetics when fasting blood glucose exceeded 350 mg/dl within 3 days after STZ injection. The fasting blood glucose level was measured every 3 days in each rat, and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) levels were measured right before the experiment. All experiments were conducted in rats that had experienced hyperglycemia (fasting glucose level >350 mg/dl) for 2–3 wk and confirmed with HbA1c measurement. The fasting blood glucose level in normal rats (n = 5) was 80 ± 17.3 mg/dl, and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) HbA1C was 26 ± 1.2 (mmol HbA1c/mol Hb). In STZ-induced diabetic rats (n = 26), the mean fasting glucose level of all measurements, starting at 24 h after STZ injection until the experimental date, was 370 ± 11.2 mg/dl, and the IFCC HbA1C level, measured right before the experiment (2–3 wk after STZ injection), was 88 ± 1.5. The general health conditions of STZ rats were monitored daily. Following instructions recommended by the ACUC at West Virginia University, insulin was given if fasting glucose level reached >450 mg/ml. There was an average of 7.6% body wt loss during the 2- to 3-wk period, and the euthanization rate, due to poor health condition, was 8.3%.

Measurement of Lp in individually perfused rat mesenteric microvessels.

A modified Landis technique was used to measure Lp in individually perfused microvessels. The methods have been evaluated in detail (11, 22, 25). Briefly, a single microvessel was cannulated with a micropipette and perfused with albumin-Ringer solution (control) containing red blood cells (∼1% vol/vol) as markers under a known hydrostatic pressure ranging from 40 to 60 cmH2O. For each measurement, the perfused vessel was occluded briefly downstream with a glass rod for 5∼7 s. The initial water flux/unit area of microvessel wall was calculated from the velocity of the marker cell after vessel occlusion, the vessel radius, and the distance between the marker cell and the occlusion site. Lp was calculated as the slope of the relationship between the initial water flow/unit area of vessel wall and the pressure difference across the vessel wall. In each experiment, the baseline Lp and the Lp after application of PAF or other treatment were measured in the same vessel.

Measurement of endothelial [Ca2+]i in individually perfused venules.

Endothelial [Ca2+]i was measured with Ca2+ imaging in individually perfused microvessels using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fura-2 AM. Experiments were performed on a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope equipped with a 12-bit digital, cooled charge-coupled device camera (ORCA; Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan), a computer-controlled shutter, and a filter changer (Lambda 10-2; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). In each experiment, a venular microvessel was cannulated and perfused with albumin-Ringer solution that contained 10 μM fura-2 AM for 45 min. The vessel was then recannulated and perfused with albumin-Ringer solution for 10 min to remove fura-2 AM from the vessel lumen. The excitation wavelengths were selected by two interference filters (Oriel; 340 ± 5 and 380 ± 5 nm), and the emission was separated with a dichroic mirror (DM400) and an interference filter (Oriel; 500 ± 20 nm). The excitation wavelength for Ca2+ imaging alternated between 340 and 380 nm, and images were acquired with 0.25-s exposure at each wavelength. At the end of the experiment, the microvessel was superfused with a modified Ringer solution (5 mM of Mn2+ without Ca2+) and then perfused with the same solution that contained ionomycin (10 μM) to bleach the Ca2+-sensitive form of fura-2. The background fluorescence intensity (FI), due to unconverted fura-2 AM and other Ca2+-insensitive forms of fura-2, was subtracted from FI340 and FI380 values. MetaFluor software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA) was used for image acquisition and data analyses. Quantitative analysis of [Ca2+]i at the individual endothelial cell level was conducted using manually selected regions of interest (ROIs) along the vessel wall. Each ROI covers the area of one individual endothelial cell, as indicated by the fluorescence outline. The ratios of the two FI values were converted to [Ca2+]i using an in vitro calibration curve (22). Details have been described elsewhere (40, 41).

Confocal imaging.

A Leica TCS SL confocal microscope attached to a single-vessel perfusion rig was used for collecting images. A stack of confocal images was obtained from each vessel by optical sectioning at successive x–y focal planes with vertical steps (z-axis) at 0.5, 0.3, and 0.2 μm using Leica objective ×20 [numerical aperture (NA), 0.7] with ×3 electronic zoom, ×25 (NA, 0.95) with ×2.5 electronic zoom, and ×63 objective (NA, 1.2), respectively, using a 1,024 × 1,024 pixel-scanning format. The selected pinhole diameter (one airy disk) and the vertical step at the z-axis were within the effective resolution limitations calibrated for the objective, wavelength, and electronic scanning format used in the Leica confocal system and complied with Nyquist criterion. Identical image acquisition parameters were applied to each group of studies. Stacks of images were processed using Leica confocal software, and each of the confocal images presented in the figures is the projection of the lower half of the image stack.

Fluorescent staining.

The perfused microvessel was fixed with paraformaldehyde, either under control conditions or at the PAF-induced Lp peak. Actin staining was performed after each vessel was fixed with paraformaldehyde and treated with Triton X-100 during albumin-Ringer perfusion or at the PAF-induced Lp peak (∼7 min of PAF perfusion). Then, each vessel was perfused with Alexa Fluor 488- or tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled phalloidin for 5–10 min in the absence or presence of nuclei dye, DRAQ5. Single- or dual-channel confocal images were acquired after washing away the unbound dye(s) by albumin-Ringer perfusate. Vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin or PAF receptor staining was performed after the rat mesentery bearing the perfused venule was fixed during perfusion and then removed from the animal. The tissue was then exposed to the primary antibody against VE-cadherin or the PAF receptor overnight, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h. The mean FI (MFI) of PAF receptor labeling was quantified from a stack of images collected from a segment of the vessel wall using Leica Confocal Software. The MFI of each vessel was derived from the mean amplitude of three ROIs selected from each vessel segment and expressed in arbitrary units.

Visualization of PAF-induced gap formation in intact microvessels.

The magnitude of the endothelial gaps was evaluated by quantification of accumulated fluorescent microspheres (FMs; 100 nm in diameter) at endothelial clefts using confocal imaging. Details of the experimental procedures and method evaluations have been described previously (24). Briefly, each vessel was perfused with albumin-Ringer solution containing FMs (3 × 1011/ml), with or without PAF for 10 min, and followed by albumin-Ringer perfusate alone for 10 min to remove FMs from the vessel lumen before collecting images. The total FI of FM (area × depth × mean intensity/pixel) for each vessel segment was quantified as total intensity/surface area of the vessel wall under control conditions and after PAF exposure (24). The accumulation of FMs at junctions between endothelial cells is illustrated by projection of images from the lower half of the image stack.

Solutions and reagents.

Mammalian Ringer solution was used for the experiments. The composition of the mammalian Ringer solution was (in mM): 132 NaCl, 4.6 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 5.5 glucose, 5.0 NaHCO3, 20 N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid), Na-N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4. All perfusates contained 1 g/dl BSA. Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR)- and TRITC-labeled phalloidin and the primary and secondary VE-cadherin antibodies were all from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). DRAQ5 was from BioStatus (Leicestershire, UK). Anti-PAF receptor antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). PAF (1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved initially in 95% ethyl alcohol (5 mM) and diluted further to a final concentration of 10 nM with albumin-Ringer solution. All of the perfusates containing the test agents were freshly prepared before each cannulation.

Data analysis and statistics.

All values are means ± SE. To avoid the potential effect of the applied reagents on subsequent vessel studies, each experiment was performed on one microvessel from each animal, and “n” represents the number of vessels or rats used for the experiments. A paired t-test was used for paired data analysis from the same vessel, and ANOVA was used to compare data between groups. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Diabetic rat venules show markedly enhanced Lp and endothelial calcium responses to PAF.

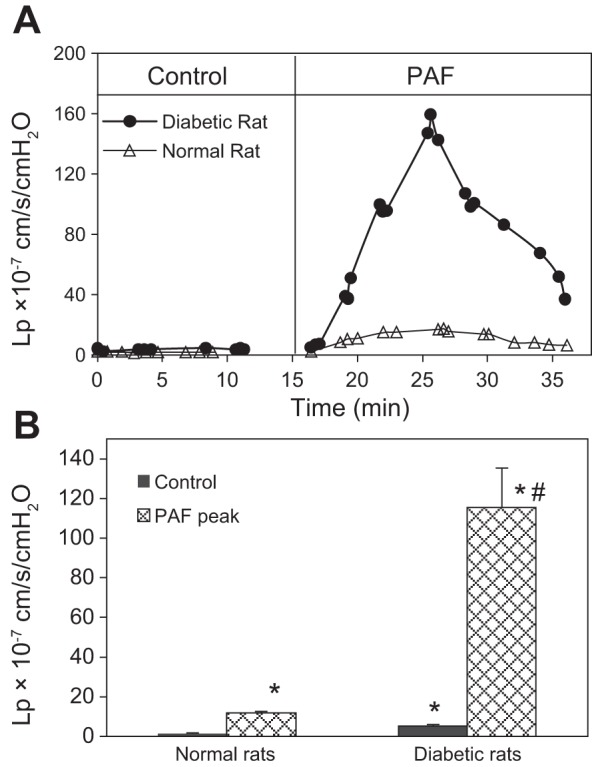

Lp was measured in the microvessels of both normal and diabetic rats. The mean baseline Lp in the normal rat vessels was 1.6 ± 0.1 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (n = 7). Perfusion of PAF (10 nM) induced a transient increase in Lp with a mean peak value of 12.0 ± 1.7 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, occurring at 7.2 ± 1.3 min of PAF perfusion. In diabetic rats, venule diameter did not show significant difference from that in normal rats, but the number of adherent leukocytes on the microvessel wall was increased significantly from 1.5 ± 0.4 (normal vessel, n = 8) to 10 ± 1.6 (n = 5)/100 μm vessel length. However, ∼50% of adherent leukocytes were washed away during perfusion. The mean baseline Lp of the diabetic rat vessels was 5.1 ± 0.7 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (n = 5), a 3.2-fold increase from that of the normal rat vessels. When PAF was applied to each of the diabetic vessels, the mean peak Lp reached 115.4 ± 20.0 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, which is 9.5 times the PAF-induced peak Lp in the normal vessels. The potential effect of IP injection on the subsequent study of mesenteric microvessels was examined in three microvessels by IP injection of vehicle. The baseline Lp was 1.5 ± 0.2 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, and the mean peak response to PAF was 12.3 ± 2.6 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, showing no significant differences from the normal vessels. Figure 1A shows the magnitude and time course of the changes in Lp in normal and diabetic vessels, and Fig. 1B summarizes the results.

Fig. 1.

Comparisons of baseline hydraulic conductivity (Lp) and platelet-activating factor (PAF)-induced Lp changes between normal and diabetic venules. A: the overlay of 2 individual experiments demonstrates the differences in time course and the magnitude of the Lp changes between a normal and a diabetic venule. B: summarized data showing that in diabetic venules (n = 5), the mean baseline Lp was elevated from 1.6 ± 0.1 (normal vessel, n = 7) to 5.1 ± 0.7 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, whereas in PAF-induced Lp, the mean peak Lp was potentiated from 12.0 ± 1.8 (normal vessel) to 115.4 ± 20.2 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1. Intraperitoneal injection of vehicle (sham control) showed no effects on baseline Lp and PAF-induced Lp increases (n = 3). *Significant increases from control; #significant increases from normal vessel responses.

The changes in endothelial [Ca2+]i were also measured in both normal and diabetic vessels before and after exposure to PAF (n = 5/group). The mean baseline endothelial [Ca2+]i was not significantly different between normal and diabetic vessels (84 ± 10 and 92 ± 4 nM, respectively). However, when diabetic vessels were exposed to PAF (10 nM), endothelial [Ca2+]i reached a mean peak level of 1,234 ± 189 nM, which was much higher than the mean peak value of 772 ± 32 nM observed in the normal vessels. The peak [Ca2+]i occurred within the first 2 min of PAF application in all vessels. Figure 2A shows the endothelial Ca2+ response to PAF in normal and diabetic vessels from single experiments, and Fig. 2B summarizes the results.

Fig. 2.

Diabetic vessels show higher Ca2+ responses to PAF than that in normal vessels. A: 2 representative experiments showing the differences in PAF-induced increases in endothelial intracellular Ca2+ concentration (EC [Ca2+]i) between normal and diabetic vessels. Endothelial [Ca2+]i in the diabetic vessel increased at a faster rate and reached a higher magnitude than that in a normal vessel. The time courses were derived from calcium imaging, and each point is the mean value of 12–18 regions of interest (endothelial cells) of the vessel wall. B: summary results of PAF-induced increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i in normal and diabetic vessels (n = 5/group). *Significant increases from control; #significant increases from normal vessel responses.

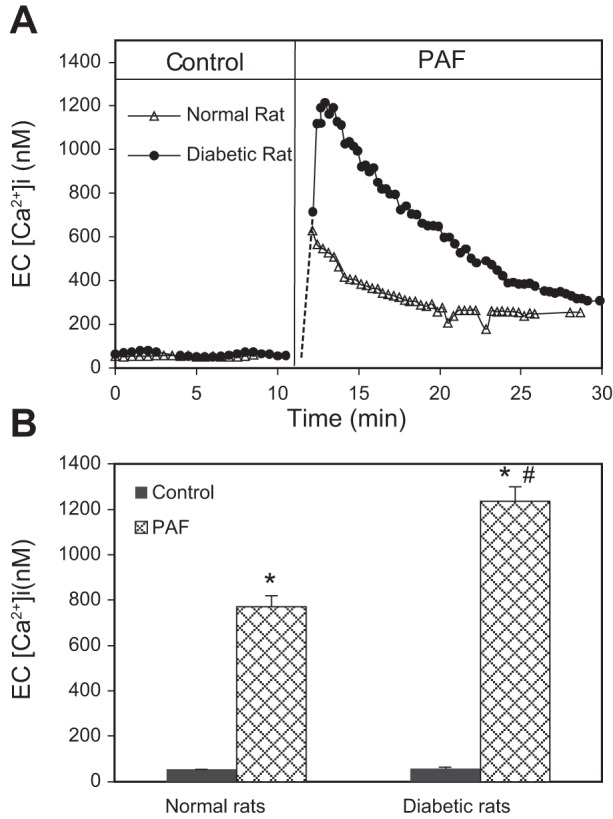

The augmented Lp responses to PAF in diabetic vessels were not due to the alterations of receptor expression.

The levels of the PAF receptor at the microvessel walls were examined in both normal and diabetic rats using immunostaining and confocal imaging (n = 3/group). Figure 3A shows confocal images of individual vessel segments, demonstrating the levels and the distributions of the PAF receptor in the vessel walls. The quantification of the MFI showed no significant difference in PAF receptor staining between the normal and diabetic vessels (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Immunostaining of PAF receptor in normal and diabetic mesenteric venules. A: representative confocal images of fluorescent immunostaining of the PAF receptor in normal and diabetic venules (green). The nuclei were labeled with DRAQ5 (red). The application of a secondary antibody (Ab) alone showed no significant green fluorescence. Each image is the maximum projection of ½ of the vessel. B: quantification of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) from normal and diabetic vessels (n = 3/group).

Diabetic vessels formed larger gaps between endothelial cells than normal rat vessels upon PAF stimulation.

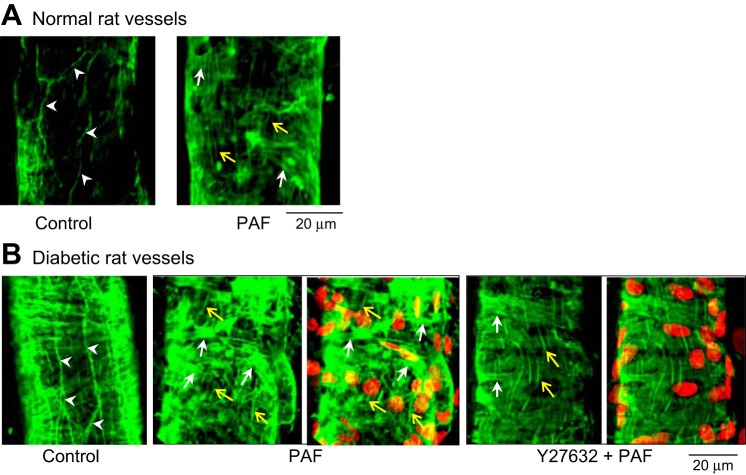

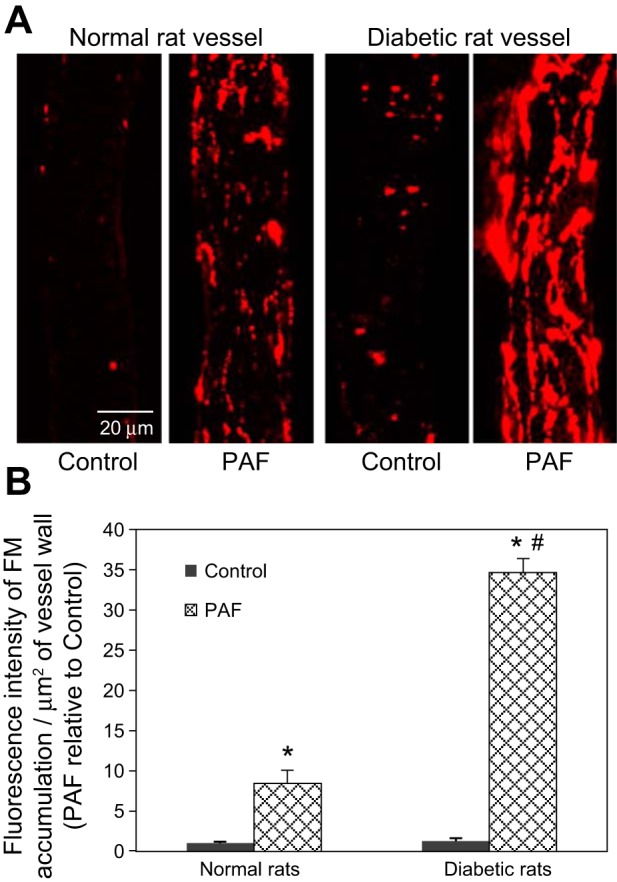

To investigate the changes in endothelial junctions in PAF-induced diabetic venules, we evaluated the magnitude of endothelial gap formation at the PAF-induced Lp peak using FMs as markers. Following our previously established method (24), FMs were added to the perfusate under control conditions or with PAF application. Confocal images were collected after luminal FMs were washed away with albumin-Ringer perfusate. The accumulation of FMs at endothelial junctions represents the magnitude of endothelial gap formation (24). Figure 4A shows representative confocal images of FM accumulation with and without PAF exposure in normal and diabetic vessels. Under control conditions, the MFI of accumulated FMs in diabetic vessels was 1.3 times that in the normal vessels (n = 5/group). Upon PAF stimulation, the accumulated FM at the PAF-induced Lp peak in diabetic vessels (n = 4) was significantly increased compared with that in normal vessels (n = 5), and the FI of accumulated FM relative to control increased from 8.4 (normal vessels) to 34.7 (Fig. 4B), which indicates that the formation of larger endothelial gaps was associated with the higher Lp increase in diabetic vessels.

Fig. 4.

In response to PAF, diabetic vessels form larger gaps between endothelial cells than normal vessels: confocal images of fluorescent microsphere (FM) accumulation at endothelial junctions. A: representative confocal images showing FM accumulation in normal and diabetic vessel walls under control conditions and after PAF stimulation. B: quantification of the MFI of FM accumulation at junctions between endothelial cells in normal and diabetic vessels. Data are presented as FI/μm2 vessel wall relative to the control value measured in the normal vessels (n = 5/group). *Significant increases from control; #significant increases from normal vessel responses.

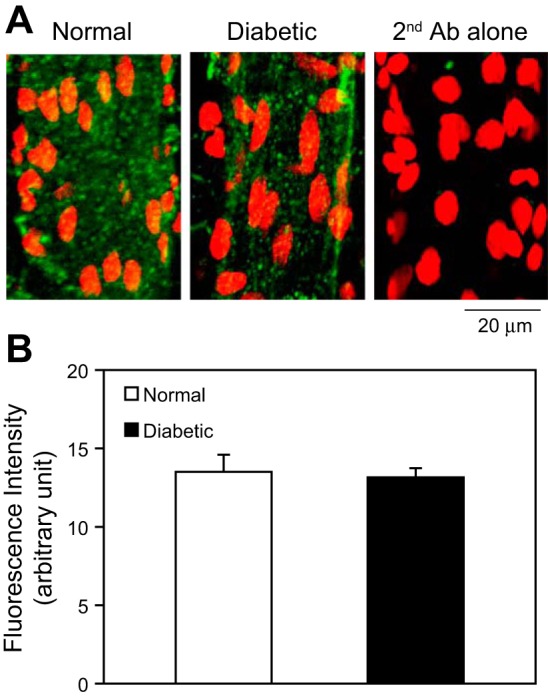

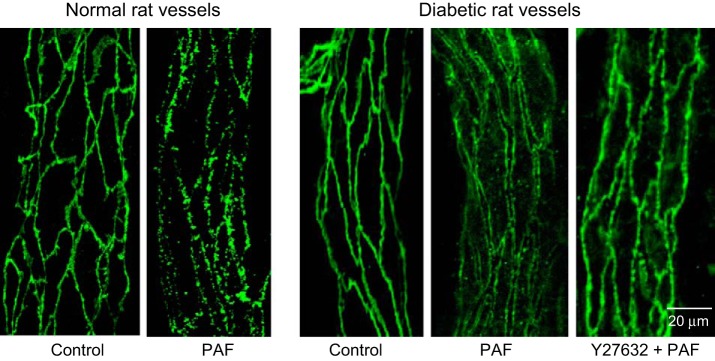

Diabetic microvessels exhibit enhanced stress fiber formation and largely separated VE-cadherin between endothelial cells at the PAF-induced Lp peak.

Endothelial VE-cadherin and F-actin in normal and diabetic vessels were viewed with confocal imaging with albumin-Ringer perfusion (control) and at the PAF-induced Lp peak (n = 4/group). Figure 5 shows that under control conditions, both normal and diabetic vessels maintained a continuous VE-cadherin distribution along the junctions between adjacent endothelial cells. The VE-cadherin staining also revealed no significant differences in endothelial cell shape and size between normal and diabetic vessels. While at the PAF-induced Lp peak, VE-cadherin staining in diabetic vessels showed a completely different profile from that in normal vessels, which exhibited frequent breaks without obvious separation between endothelial cells, whereas diabetic vessels showed a large gap between the VE-cadherin of adjacent endothelial cells with fewer breaks. Figure 6 shows the changes in F-actin in normal and diabetic vessels. Like VE-cadherin staining, there was no difference in F-actin staining between normal and diabetic vessels under control conditions, demonstrating intact, peripheral F-actin distribution. However, at the PAF-induced Lp peak, we observed markedly enhanced formation of F-actin bundles and stress fibers at pericytes and endothelial cells in diabetic vessels compared with normal vessels.

Fig. 5.

Vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin staining under control and PAF-stimulated conditions in normal and diabetic rat vessels. VE-cadherin in normal rat vessels shows continuous distribution under control conditions and frequent breaks at the PAF-induced Lp peak. In diabetic vessels, VE-cadherin distribution under control conditions shows no difference from normal vessels but exhibits large gaps between endothelial cells with PAF stimulation. The application of Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 replaces PAF-induced VE-cadherin separation with some breaks on a single profile distribution.

Fig. 6.

Confocal images of phalloidin staining of F-actin in normal and diabetic microvessels. A: in normal vessels, F-actin was located at the peripheral of endothelial cells under control conditions (arrowheads). At the PAF-induced Lp peak, endothelial peripheral F-actin disappeared and was replaced by stress fibers (green, vertically oriented), indicated by yellow arrows. Pericyte F-actin (horizontally oriented) was indicated by white arrows. These changes correlated to a Lp increase from 1.6 (control) to 12.0 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1. B: F-actin staining in diabetic vessels. Under control conditions, F-actin (left) remained at the peripheral of endothelial cells (arrowheads). At the PAF-induced Lp peak (2nd and 3rd from left), there was markedly increased stress fibers in endothelial cells (yellow arrows), and the pericyte F-actin also formed disorganized bundles (white arrows), indicating pericyte contraction. Red shows DRAQ5-labeled nuclei. These changes in F-actin correlated to a Lp increase, 10 times higher than that in the normal vessels shown in A. The 2 right images show that the application of Y27632, a Rho kinase inhibitor, prevented the increased stress fiber formation and pericyte contraction at the PAF-induced Lp peak and restored the F-actin pattern close to that in normal vessels. This reflected >90% reduction of the PAF-induced Lp increases in diabetic vessels.

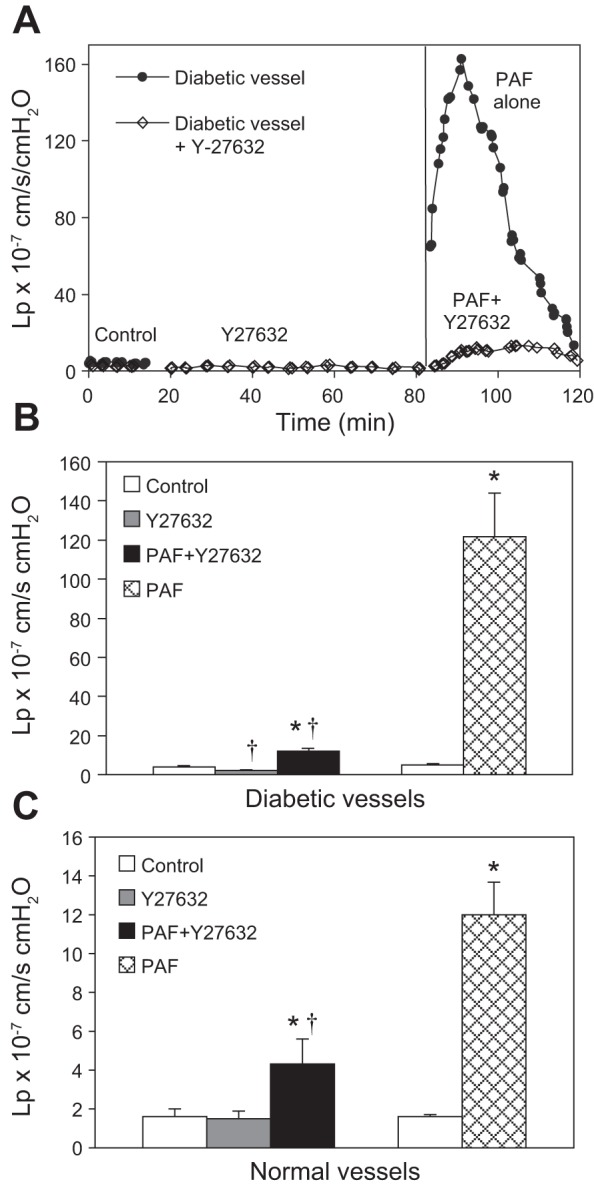

Inhibition of Rho kinase attenuated PAF-induced enhanced permeability increases, cytoskeleton contractility, and adherens junction disassembly in diabetic vessels.

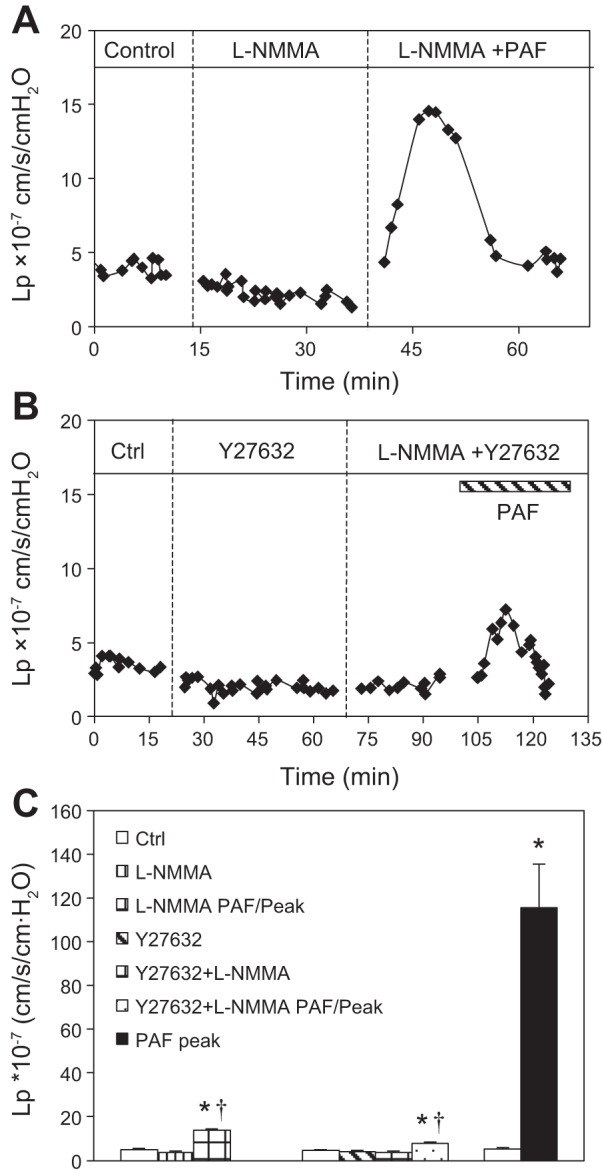

To investigate the role of Rho-dependent signaling pathways in the enhanced permeability responses to PAF in diabetic vessels, we examined PAF-induced changes in Lp, VE-cadherin, and cytoskeletal F-actin when the Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 was applied to the diabetic vessels. Figure 7A compares the baseline Lp and PAF-induced Lp changes in the absence and presence of Y27632 in two individual experiments. The mean baseline Lp of six diabetic vessels was 4.0 ± 0.8 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1. After perfusion of Y27632 (30 μM) for 1 h, the mean Lp decreased slightly to 2.2 ± 0.2 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (P = 0.03). When PAF (10 nM) was added to the perfusate in the presence of Y27632, the mean peak Lp was only 11.9 ± 1.7 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, which was a significant reduction from the mean peak Lp of 115.4 ± 22.4 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, measured in the absence of Y27632 (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Different magnitude inhibition of PAF-induced Lp increases by the Rho kinase inhibitor in normal and diabetic venules. A: the overlay of 2 individual experiments conducted in diabetic venules, demonstrating the time course and the magnitude differences in PAF-induced Lp increases, with and without the application of Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632. B: summarized data showing that in diabetic venules, the application of the Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 (30 μM) restored the increased basal Lp and attenuated PAF-induced peak Lp by >90% (n = 6). C: in normal rat venules, Y27632 did not affect basal Lp but reduced PAF-induced Lp increases by ∼70% (n = 4). *Significant increases from control; †significant decreases from positive control.

Similarly, the application of Y27632 abolished PAF-induced manifestations of VE-cadherin and F-actin in diabetic vessels (n = 3/group). At the PAF-induced Lp peak, we observed only small breaks along a single profile of VE-cadherin and much less stress fiber and F-actin bundle formation in both endothelial cells and pericytes than in the absence of Y27632 application. Representative images are shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

To determine the involvement of Rho-dependent pathways in PAF-induced Lp increases in normal vessels, Y27632 was applied to four normal vessels before and during PAF stimulation. The mean baseline Lp was 1.6 ± 0.4 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1. Perfusion of Y27632 (30 μM) for 1 h did not affect basal Lp; the mean value was 1.5 ± 0.4 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1. When PAF was added to the perfusate in the presence of Y27632, the mean peak Lp was 4.3 ± 1.3 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, a significant reduction from 12.0 ± 1.7 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, a mean value in the absence of Y27632 (n = 7, P = 0.02; Fig. 7C).

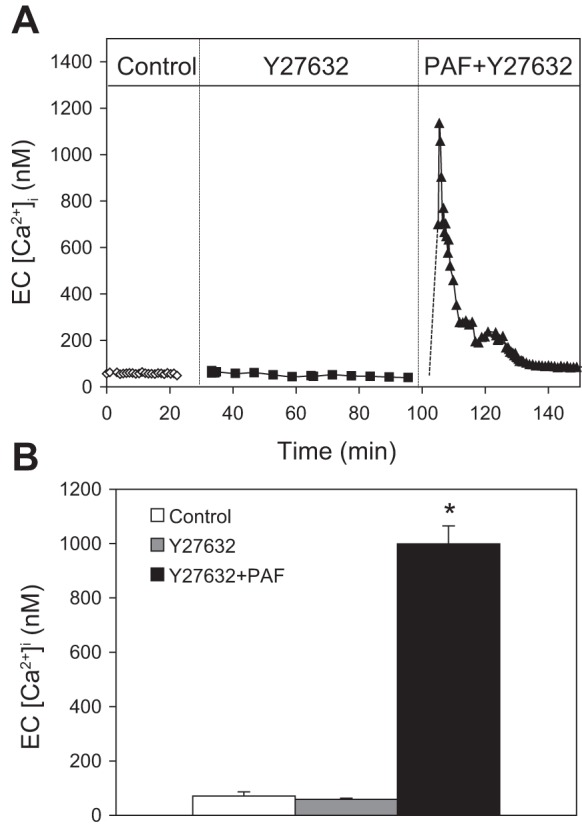

Rho kinase inhibitor attenuates endothelial cytoskeleton and Lp responses to PAF without affecting PAF-induced potentiated increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i in diabetic vessels.

To examine whether the magnitude of inhibition of PAF-induced increases in Lp and cytoskeletal contractile activity by Y27632 in diabetic vessels was due to its inhibition of increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i, we measured PAF-induced increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i after perfusing diabetic microvessels with Y27632 (30 μM) for 1 h (n = 3). Neither basal endothelial [Ca2+]i nor PAF-induced increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i were affected significantly by Y27632. The PAF-induced mean peak [Ca2+]i was 999 ± 66 nM, which is not significantly different from that measured in diabetic vessels in the absence of Y27632 but is significantly higher than the PAF-induced peak [Ca2+]i in normal vessels. Figure 8A shows the changes in endothelial [Ca2+]i from an individual experiment, and Fig. 8B shows a summary of the results.

Fig. 8.

Rho kinase inhibitor attenuates PAF-induced Lp increases without affecting PAF-induced increases in endothelial cell [Ca2+]i in diabetic vessels. A: an individual experiment showing that the application of Y27632 (30 μM) has no effect on PAF-induced increases in endothelial cell [Ca2+]i. B: result summary of 3 vessels. *Significant increases from control.

Role of NO in PAF-induced enhanced increases in Lp in diabetic vessels.

Increased endothelial [Ca2+]i-triggered endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) activation and increased NO production have been shown to play important roles in PAF-induced increases in Lp in normal vessels (42, 43). In this study, we investigated further the role of NO in baseline Lp and PAF-induced Lp increases and the relationship between NO and Rho-dependent signaling in diabetic vessels. The mean baseline Lp of nine diabetic vessels was 4.9 ± 0.5 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1. After perfusion of L-NMMA (100 μM) for 20 min, the mean baseline Lp decreased slightly to 3.7 ± 0.8 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (P = 0.03). When PAF (10 nM) was added to the perfusate, the mean peak Lp was reduced to 13.9 ± 0.5 ×10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (n = 3), which was a significant reduction from the mean peak Lp of 115.4 ± 22.4 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 measured in the absence of L-NMMA (Fig. 9, A and C). The increase of L-NMMA concentration to 2 mM showed no significant difference from the 100-μM group (n = 2). The addition of L-NMMA (100 μM) in Y27632 perfused vessels (n = 4) did not decrease the baseline Lp further but further attenuated the PAF-induced Lp increase from 11.9 ± 1.7 (Y27632 alone) to 7.7 ± 0.8 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (P = 0.04; Fig. 9, B and C).

Fig. 9.

Role of nitric oxide in PAF-induced enhanced increases in microvessel permeability in diabetic vessels. A: a representative graph of 3 experiments demonstrates that the application of L-NMMA (100 μM) decreased the PAF-induced Lp increase in a diabetic venule. B: a representative graph of 4 experiments demonstrates that adding L-NMMA after Y27632 perfusion further decreased the PAF-induced Lp increase in a diabetic venule. C: summary of 3 groups of studies. *Significant increases from control (Ctrl); †significant decreases from positive control.

DISCUSSION

Diabetes-associated endothelial barrier dysfunction has been reported in various organ vasculatures and is considered the initiating factor for vascular complications and organ dysfunction (27, 34, 38). With the use of individually perfused, intact microvessels, our study provides a quantitative assessment of the changes in microvessel permeability at an early stage of STZ-induced diabetes (2–3 wk after STZ-induced hyperglycemia) under both basal and inflammatory conditions. We also provide a direct comparison of inflammatory mediator-induced changes in endothelial [Ca2+]i, cytoskeleton F-actin, adherens junctions, and Rho activation involvement in normal and diabetic rat vessels. Our findings suggest that diabetic conditions transform the endothelial cells at microvessel walls into a proinflammatory phenotype. Although they have moderately increased basal permeability with a relatively intact cellular junction in the absence of additional stimuli, they manifest augmented responses to inflammatory mediators with potentiated increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i, RhoA/Rho-associated protein kinase-dependent enhanced F-actin cytoskeleton contractile activity, and VE-cadherin separation, resulting in the formation of larger endothelial gaps and greater increases in microvessel permeability than those of normal vessels.

At early stages of STZ-induced diabetes, the basal permeability of rat vessels increased moderately (approximately three times that of normal rat vessels) without significant changes in endothelial junctions, as illustrated by continued VE-cadherin distribution between endothelial cells (Fig. 5). Striking differences occurred when the vessels were acutely stimulated with an inflammatory mediator. PAF-induced permeability increases in diabetic rat vessels were ∼10 times higher than normal vessel responses. The chronic inflammation-associated higher vascular leakage in response to substance P was reported, due to the upregulation of substance P receptors (6). Our study with immunofluorescence staining and confocal imaging showed no significant difference in PAF receptor expression between normal and diabetic mesenteric venules. Therefore, our results suggest that the enhanced permeability responses to PAF in diabetic rats were associated with increased sensitivity to inflammatory stimuli and the changes in downstream signaling pathways and not due to the alterations of receptor expression. These results explain the clinical observation that the majority of diabetic patients could enjoy a normal life without tissue edema if the patients have no severe vascular complications. However, if diabetic patients encounter an infection or other vascular diseases, then they will manifest more severe reactions and will have a poorer outcome compared with those without diabetes (5, 15, 26, 28, 29).

Our previous studies indicated that the magnitude of increase in endothelial [Ca2+]i determines the magnitude of increase in microvessel permeability (16, 18). In agreement with this, the potentiated Lp response to PAF observed in diabetic vessels was accompanied with a higher magnitude of increase in endothelial [Ca2+]i over that of normal rat vessels. Based on cell-culture studies, the extent of cell retraction and phosphorylation of the myosin light chain (MLC) is Ca2+ dependent, which accounts for the formation of gaps between adjacent cells (36). In diabetic rat vessels, the enhanced endothelial Ca2+ responses to PAF could play an essential role in the greater contractile activity of the cytoskeleton, leading to VE-cadherin separation, enlarged gap formation between endothelial cells, and marked increases in microvessel permeability.

Increasing evidence indicates that diabetes is associated with chronic vascular inflammation. Our study demonstrated that diabetic microvessels share many patterns similar to chronic inflammation or vascular remodeling due to previous inflammatory exposure but also show some differences (6, 9, 14, 37). Both diabetic vessels and vessels, 3 days after inflammatory exposure, show increased leukocyte adhesion on the microvessel walls, and their permeability responses to PAF were ∼10-fold higher than that in normal vessels (37). Meanwhile, the augmented increases in Lp were all accompanied with markedly increased endothelial [Ca2+]i, stress fiber formation, separated VE-cadherin, and large gap formations between endothelial cells (37). However, diabetic venules showed no significant changes in endothelial cell shape and vessel diameter compared with normal vessels, demonstrated by VE-cadherin staining that outlined endothelial cell shape and vessel diameter. In contrast, both chronic-inflamed vessels (14) and venular microvessels 3 days after inflammatory exposure (37) showed notable changes in endothelial cell shape with an ∼60% enlargement of vessel diameter. Increases in vessel wall thickness with perivascular cell proliferation were also observed in vessels, 3 days after inflammatory exposure, but similar changes were not found in diabetic vessels. These observations indicate that 2–3 wk of hyperglycemic conditions are sufficient to cause alterations of the sensitivity of endothelial signaling pathways and cytoskeleton responses to inflammatory stimuli, resulting in augmented increases in microvessel permeability, a pattern similar to those occurring in microvessels experiencing chronic inflammation or vascular remodeling following an infection (6, 9, 14, 37), but did not involve significant morphological changes in cell shape and vascular wall structures.

In addition to the Ca2+ signaling that regulates the phosphorylation of the MLC and tension development, Rho family GTPases have been implicated in the intracellular signaling of many vasoactive agents and have been shown to regulate both actin cytoskeletal activity and the integrity of intercellular junctions (30, 33, 35). However, Rho-mediated contractile mechanisms have been reported to be only applicable to cultured endothelial cells that display an upregulated contractile phenotype and are not thought to be involved in inflammatory mediator-induced hyperpermeability in intact microvessels (1, 10, 32). Our study, conducted in individually perfused intact microvessels, indicates the involvement of different levels of stimulus-induced Rho activation in normal and diabetic vessels. In diabetic vessels, the inhibition of Rho kinase by Y27632 markedly reduced PAF-induced permeability increases from a mean peak Lp of 115.4 ± 22.4 to 11.9 ± 1.7 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (a reduction of >90%). However, in normal vessels, Y27632 was less effective than in diabetic rat vessels but still significantly attenuated PAF-induced Lp increases by ∼70% (from 12.0 ± 0.1 to 4.3 ± 0.1 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1). The magnitude of differences in Rho-dependent permeability increases could be explained by different levels of contractile activity in normal and diabetic vessels as those shown by F-actin staining (Fig. 6). PAF-induced permeability increases in diabetic vessels were accompanied with more prominent stress fiber formation and a greater magnitude of endothelial gap formation than in normal vessels, indicating much higher levels of contractile activity. Our results that the application of the Rho kinase inhibitor in diabetic vessels reduced stress fiber formation, prevented VE-cadherin separation, and largely attenuated the PAF-induced Lp increase strongly suggest that the upregulation of Rho-dependent contractile mechanisms and redistribution of VE-cadherin at junctions play important roles in the enhanced permeability increases in diabetic vessels.

Despite the indication that increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i and Rho activation both play important roles in the regulation of cytoskeleton contractility and adherens junctions, their inter-relationship in the regulation of agonist-induced permeability increases in intact microvessels has not been well defined. Our previous studies on microvessels of normal animals demonstrated that agonist-induced initial Ca2+ influx correlated directly with the magnitude of permeability increases and that blockage of Ca2+ influx or removal of extracellular Ca2+ abolished agonist-induced permeability increases (16, 18, 22). Those studies indicate that increased Ca2+ influx is a necessary, initial signal for permeability increases. On the other hand, we also found many regulatory mechanisms that modulate permeability downstream from Ca2+ entry, such as agents that directly regulate cAMP or cGMP levels or eNOS activity (17, 19–21, 39). In the present study, we demonstrated that inhibition of Rho kinase by Y27632 markedly reduced PAF-induced Lp increases in diabetic vessels without affecting PAF-induced increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i, which suggests that the blocking of the activation of Rho kinase is sufficient to overcome increased Ca2+-mediated phosphorylation of the MLC. The ratio of MLC kinase to MLC phosphatase (MLCP) has been indicated as a major determinant of the contractile response through the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of myosin, respectively (3). In addition, studies using permeabilized smooth muscle cells reported that RhoA activation not only inhibits MLCP but also enhances the Ca2+ sensitivity of myosin (31). Our quantitative measurements of both endothelial [Ca2+]i and Lp in intact microvessels in the absence (normal vessels) and presence (diabetic vessels) of upregulated Rho activation support this potential mechanism. Our previous studies in normal vessels showed that the increase of the chemical driving force of Ca2+ entry by elevating extracellular [Ca2+] from 2 to 10 mM increased PAF-induced endothelial [Ca2+]i from 500 to 1,225 nM. The correlated Lp increased from 12 to 28 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1 (39). In contrast, when the PAF-induced peak endothelial [Ca2+]i was 1,234 nM in diabetic vessels in the present study, the correlated peak Lp was 115 × 10−7 cm·s−1·cmH2O−1, a much greater increase than the same levels of endothelial [Ca2+]i-mediated Lp increase observed in normal vessels (39). These mismatched magnitudes between the increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i and Lp in diabetic vessels support the hypothesis that enhanced Rho-dependent signaling may not only inhibit MLCP, which promotes the Ca2+/calmodulin-mediated MLC phosphorylation, but may also increase the myosin sensitivity to Ca2+. Therefore, the enhanced Rho signaling in diabetic vessels, at the same levels of increased endothelial [Ca2+]i as those in normal vessels, resulted in more prominent stress fiber formation, VE-cadherin separation, and increases in microvessel permeability. This mechanism may also explain the marked reduction in PAF-induced permeability increases by the inhibition of Rho kinase in the presence of high endothelial [Ca2+]i, which might be attributable to both the increased activity of MLCP and decreased myosin calcium sensitivity. Although the evidence is indirect, it provides in vivo support for such a concept at molecular levels.

Our previous studies demonstrated that although increased endothelial [Ca2+]i plays an essential role in the regulation of inflammatory mediator-induced endothelial gap formation and microvessel permeability (16, 18, 24, 40), the blocking of PAF-induced NO production by inhibition of NOS nearly abolished the permeability increase without affecting the initial increase in endothelial [Ca2+]i in intact venules (42, 43). Those results suggest that increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i are necessary but not sufficient to increase permeability, indicating an interdependent relationship between endothelial Ca2+ and NO in the regulation of microvessel permeability. In this study, the application of L-NMMA to diabetic microvessels also showed a significant reduction of PAF-induced permeability increase. The observation that inhibition of both Rho kinase and NOS further reduced PAF-induced Lp increase more than one inhibitor application alone suggests that under diabetic conditions, Ca2+-induced increases in NO production and the activation of Rho-dependent signaling both contribute to increased permeability via regulating common, as well as signaling-specific, cellular components.

The role of the Rho-dependent actin cytoskeleton in mediating cell contractility and endothelial barrier dysfunction has been well documented in cultured endothelial cells; however, there is less evidence for their direct link with cardiovascular diseases. The present study provides in vivo evidence that the contractile mechanisms that are upregulated via Rho-mediated signaling play important roles in the exaggerated permeability increases observed when microvessels from diabetic rats were exposed to inflammatory mediators. Our experiments demonstrate a replicate manifestation of the exacerbated vascular barrier dysfunction when diabetic patients are exposed to additional inflammation or have an infection. The significant inhibitory effect of the Rho kinase inhibitor on increased permeability in diabetic microvessels indicates that Rho signaling could be a great therapeutic target for diabetes-associated vascular leakage and could prevent endothelial barrier dysfunction associated with organ dysfunction.

GRANTS

Support for this study was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL56237 and HL084338 and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant DK097391 (to P. He) and an American Heart Association Great Rivers Affiliate 12PRE11470010 Predoctoral Fellowship (to S. Xu).

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.Y. and P.H. conception and design of research; D.Y. and S.X. performed experiments; D.Y., S.X., and P.H. analyzed data; P.H. interpreted results of experiments; D.Y., S.X., and P.H. prepared figures; D.Y., S.X., and P.H. drafted manuscript; S.X. and P.H. edited and revised manuscript; D.Y., S.X., and P.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson RH, Curry FE, Adamson G, Liu B, Jiang Y, Aktories K, Barth H, Daigeler A, Golenhofen N, Ness W, Drenckhahn D. Rho and Rho kinase modulation of barrier properties: cultured endothelial cells and intact microvessels of rats and mice. J Physiol 539: 295–308, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson RH, Zeng M, Adamson GN, Lenz JF, Curry FE. PAF- and bradykinin-induced hyperpermeability of rat venules is independent of actin-myosin contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H406–H417, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander JS. Rho, tyrosine kinase, Ca2+, and junctions in endothelial hyperpermeability. Circ Res 87: 268–271, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Khin S, Lieth E, Tarbell JM, Gardner TW. Vascular permeability in experimental diabetes is associated with reduced endothelial occludin content: vascular endothelial growth factor decreases occludin in retinal endothelial cells. Penn State Retina Research Group. Diabetes 47: 1953–1959, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apelqvist J. Diagnostics and treatment of the diabetic foot. Endocrine 41: 384–397, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baluk P, Bowden JJ, Lefevre PM, McDonald DM. Upregulation of substance P receptors in angiogenesis associated with chronic airway inflammation in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 273: L565–L571, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carr ME. Diabetes mellitus: a hypercoagulable state. J Diabetes Complications 15: 44–54, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Boulakia FE, Tarhzaoui K, Valensi PE, Lestrade RA, Albertini JP, Behar A. Effect of cerivastatin on peripheral capillary permeability to albumin and peripheral nerve function in diabetic rats. Diabetes Metab 33: 189–196, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curry FE, Zeng M, Adamson RH. Thrombin increases permeability only in venules exposed to inflammatory conditions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2446–H2453, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curry FR, Adamson RH. Vascular permeability modulation at the cell, microvessel, or whole organ level: towards closing gaps in our knowledge. Cardiovasc Res 87: 218–229, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curry PE, Huxley VH, Sarelius IH. Techniques in microcirculation: measurement of permeability, pressure and flow. In: Cardiovascular Physiology. Techniques in the Life Sciences. New York: Elsevier, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ergul A, Kelly-Cobbs A, Abdalla M, Fagan SC. Cerebrovascular complications of diabetes: focus on stroke. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 12: 148–158, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ergul A, Li W, Elgebaly MM, Bruno A, Fagan SC. Hyperglycemia, diabetes and stroke: focus on the cerebrovasculature. Vascul Pharmacol 51: 44–49, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ezaki T, Baluk P, Thurston G, La Barbara A, Woo C, McDonald DM. Time course of endothelial cell proliferation and microvascular remodeling in chronic inflammation. Am J Pathol 158: 2043–2055, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan X, Qiu J, Yu Z, Dai H, Singhal AB, Lo EH, Wang X. A rat model of studying tissue-type plasminogen activator thrombolysis in ischemic stroke with diabetes. Stroke 43: 567–570, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He P, Curry FE. Depolarization modulates endothelial cell calcium influx and microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1246–H1254, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He P, Curry FE. Differential actions of cAMP on endothelial [Ca2+]i and permeability in microvessels exposed to ATP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 265: H1019–H1023, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He P, Curry FE. Endothelial cell hyperpolarization increases [Ca2+]i and venular microvessel permeability. J Appl Physiol 76: 2288–2297, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He P, Liu B, Curry FE. Effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on endothelial [Ca2+]i and microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H176–H185, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He P, Zeng M, Curry FE. cGMP modulates basal and activated microvessel permeability independently of [Ca2+]i. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H1865–H1874, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He P, Zeng M, Curry FE. Dominant role of cAMP in regulation of microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1124–H1133, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He P, Zhang X, Curry FE. Ca2+ entry through conductive pathway modulates receptor-mediated increase in microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H2377–H2387, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber JD, VanGilder RL, Houser KA. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes progressively increases blood-brain barrier permeability in specific brain regions in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2660–H2668, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Y, Wen K, Zhou X, Schwegler-Berry D, Castranova V, He P. Three-dimensional localization and quantification of PAF-induced gap formation in intact venular microvessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H898–H906, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendall S, Michel CC. The measurement of permeability in single rat venules using the red cell microperfusion technique. Exp Physiol 80: 359–372, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller LM, Gorter KJ, Hak E, Goudzwaard WL, Schellevis FG, Hoepelman AI, Rutten GE. Increased risk of common infections in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis 41: 281–288, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murata T, Ishibashi T, Khalil A, Hata Y, Yoshikawa H, Inomata H. Vascular endothelial growth factor plays a role in hyperpermeability of diabetic retinal vessels. Ophthalmic Res 27: 48–52, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritter L, Davidson L, Henry M, Davis-Gorman G, Morrison H, Frye JB, Cohen Z, Chandler S, McDonagh P, Funk JL. Exaggerated neutrophil-mediated reperfusion injury after ischemic stroke in a rodent model of type 2 diabetes. Microcirculation 18: 552–561, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah BR, Hux JE. Quantifying the risk of infectious diseases for people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 26: 510–513, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen Q, Rigor RR, Pivetti CD, Wu MH, Yuan SY. Myosin light chain kinase in microvascular endothelial barrier function. Cardiovasc Res 87: 272–280, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev 83: 1325–1358, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spindler V, Schlegel N, Waschke J. Role of GTPases in control of microvascular permeability. Cardiovasc Res 87: 243–253, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Vermeer MA, van Hinsbergh VW. Role of RhoA and Rho kinase in lysophosphatidic acid-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: E127–E133, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williamson JR, Chang K, Tilton RG, Prater C, Jeffrey JR, Weigel C, Sherman WR, Eades DM, Kilo C. Increased vascular permeability in spontaneously diabetic BB/W rats and in rats with mild versus severe streptozocin-induced diabetes. Prevention by aldose reductase inhibitors and castration. Diabetes 36: 813–821, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wojciak-Stothard B, Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and the regulation of endothelial permeability. Vascul Pharmacol 39: 187–199, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wysolmerski RB, Lagunoff D. Involvement of myosin light-chain kinase in endothelial cell retraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 16–20, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan D, He P. Vascular remodeling alters adhesion protein and cytoskeleton reactions to inflammatory stimuli resulting in enhanced permeability increases in rat venules. J Appl Physiol (1985) 113: 1110–1120, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan SY, Ustinova EE, Wu MH, Tinsley JH, Xu W, Korompai FL, Taulman AC. Protein kinase C activation contributes to microvascular barrier dysfunction in the heart at early stages of diabetes. Circ Res 87: 412–417, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou X, He P. Endothelial [Ca2+]i and caveolin-1 antagonistically regulate eNOS activity and microvessel permeability in rat venules. Cardiovasc Res 87: 340–347, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou X, He P. Temporal and spatial correlation of platelet-activating factor-induced increases in endothelial [Ca2+]i, nitric oxide, and gap formation in intact venules. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1788–H1797, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Wen K, Yuan D, Ai L, He P. Calcium influx-dependent differential actions of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide on microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1096–H1107, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu L, He P. Platelet-activating factor increases endothelial [Ca2+]i and NO production in individually perfused intact microvessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2869–H2877, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu L, Schwegler-Berry D, Castranova V, He P. Internalization of caveolin-1 scaffolding domain facilitated by Antennapedia homeodomain attenuates PAF-induced increase in microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H195–H201, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]