Abstract

Hyposalivation resulting from salivary gland dysfunction leads to poor oral health and greatly reduces the quality of life of patients. Current treatments for hyposalivation are limited. However, regenerative medicine to replace dysfunctional salivary glands represents a revolutionary approach. The ability of dispersed salivary epithelial cells or salivary gland-derived progenitor cells to self-organize into acinar-like spheres or branching structures that mimic the native tissue holds promise for cell-based reconstitution of a functional salivary gland. However, the mechanisms involved in salivary epithelial cell aggregation and tissue reconstitution are not fully understood. This study investigated the role of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor (P2Y2R), a G protein-coupled receptor that is upregulated following salivary gland damage and disease, in salivary gland reconstitution. In vitro results with the rat parotid acinar Par-C10 cell line indicate that P2Y2R activation with the selective agonist UTP enhances the self-organization of dispersed salivary epithelial cells into acinar-like spheres. Other results indicate that the P2Y2R-mediated response is dependent on epidermal growth factor receptor activation via the metalloproteases ADAM10/ADAM17 or the α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 signaling pathway, which leads to activation of the MAPKs JNK and ERK1/2. Ex vivo data using primary submandibular gland cells from wild-type and P2Y2R−/− mice confirmed that UTP-induced migratory responses required for acinar cell self-organization are mediated by the P2Y2R. Overall, this study suggests that the P2Y2R is a promising target for salivary gland reconstitution and identifies the involvement of two novel components of the P2Y2R signaling cascade in salivary epithelial cells, the α5β1 integrin and the Rho GTPase Cdc42.

Keywords: salivary gland reconstitution, P2Y2 nucleotide receptor, EGF receptor, α5β1 integrin, Cdc42 Rho GTPase, extracellular ATP

salivary glands are exocrine glands composed of multiple secretory end pieces called acini, which secrete saliva into the oral cavity via a system of branched ductal cells, including intercalated ducts, striated ducts, and a main excretory duct (52). Saliva performs many protective and physiological functions by providing the oral cavity with water and electrolytes along with essential proteins, including lubricants, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and remineralization agents, digestive enzymes, and growth factors (25, 31, 52). Accordingly, hyposalivation due to salivary gland dysfunction resulting from the autoimmune disease Sjögren's syndrome (SS) or irradiation therapy for head and neck cancers leads to a significant deterioration of oral health and seriously decreases the quality of life of these patients (2, 4). Current treatments for hyposalivation are limited to saliva substitutes in the form of gels or sprays and medications, such as the muscarinic receptor agonists pilocarpine and cevimeline, which induce saliva secretion from residual salivary gland cells. However, these treatments are largely ineffective due to their transient nature or systemic side effects that are poorly tolerated by many patients (3, 106). Therefore, the development of new therapeutic approaches to treat salivary hypofunction is a necessity. Experimental approaches for restoring salivary gland function have been considered, including gene therapy to augment the expression of proteins involved in saliva secretion (28, 82, 104). An alternative approach to regain the function of salivary glands is to induce the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of residual cells in the damaged salivary glands to promote tissue regeneration (59). This approach can be further applied to bioengineer artificial salivary glands that closely resemble the native organ in both structure and function (59).

Reconstitution studies, using salivary gland tissue isolated from embryonic mice (118) and humans (90) or human salivary gland progenitor (SGP) cells (84), have demonstrated the ability of dissociated cells to migrate towards each other and self-organize into acinar-like aggregates with structural features and differentiation markers that resemble the native gland. Cellular mechanisms and components that enhance the formation of these acinar-like aggregates would likely be important factors in salivary gland reconstitution and regeneration. In this study, we investigated the role in salivary gland reconstitution/regeneration of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor (P2Y2R) for extracellular ATP and UTP, since previous findings have suggested roles for the P2Y2R in corneal epithelia wound healing by inducing cell migration (119), liver regeneration by promoting hepatocyte proliferation (8), inflammatory bowel disease by enhancing epithelial repair (27), intestinal reepithelialization following experimental colitis (26), and reduction of infarct size following myocardial infarction (20). In addition, the P2Y2R is upregulated upon disruption of salivary gland tissue homeostasis (113) and in salivary glands of the NOD.B10 mouse model of SS-like autoimmune exocrinopathy (99). In a classic model of salivary gland regeneration, P2Y2R expression and activity increase due to tissue atrophy caused by a 3-day ductal ligation in rat submandibular gland (SMG), whereas P2Y2R expression and activity levels and glandular morphology resemble unligated controls 14 days after deligation (1). Collectively, these findings suggest that P2Y2R upregulation plays a role in salivary gland regeneration.

The P2Y2R has structural motifs that enable interactions with diverse signaling pathways, such as Src homology 3 binding domains that mediate transactivation of growth factor receptors (76) and an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) domain that binds directly to αVβ3/5 integrins to activate the Rho and Rac GTPases and cytoskeletal rearrangements (6, 34, 74). P2Y2R activation also has been shown to induce downstream activation of MAPKs, including JNK (29, 110) and ERK1/2 (13, 29, 94), in several cell types. The P2Y2R also has been shown to activate metalloproteases that induce epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR) and ErbB3 phosphorylation in human salivary gland (HSG) cells (94). P2Y2R interactions and signaling pathways enable extracellular ATP and UTP to regulate numerous physiological processes, such as cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation (6, 12, 14, 34, 87, 117, 119, 125).

On the basis of the role of the P2Y2R in the regulation of intracellular signaling pathways that are crucial to tissue repair, we investigated whether the P2Y2R plays a similar role in the salivary gland using in vitro and ex vivo approaches. Our goals were to test whether P2Y2R activation enhances the aggregation and self-organization of dispersed salivary epithelial cells into acinar-like aggregates and to determine the underlying mechanisms. We found that P2Y2R-mediated formation of acinar-like spheres involves the transactivation of the EGFR through activation of the metalloproteases ADAM10/ADAM17 and the α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 Rho GTPase signaling pathway, leading to downstream activation of MAPKs.

In the following studies, we used the rat parotid acinar (Par-C10) cell line, an established in vitro model of salivary gland differentiation and function (7, 112). Par-C10 cells express endogenous P2Y2Rs, but not P2Y4R (unpublished observations) or P2Y6R (112). Therefore, P2Y2R is the only P2Y or P2X receptor subtype that responds to UTP in these cells (112). Unlike the majority of salivary cell lines, including HSG cells, Par-C10 cells are able to differentiate on Matrigel into three-dimensional (3D) acinar-like spheres that display characteristics similar to differentiated acini in salivary glands, including cell polarization and tight junction formation, which are required to maintain the transepithelial potential difference and responsiveness to muscarinic receptor agonists (7). In addition, we used primary SMG cells isolated from wild-type and P2Y2R−/− mice to corroborate the results obtained with Par-C10 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

Par-C10 cell culture.

Par-C10 cells transfected with cDNA encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged human P2Y2R (GFP-hP2Y2R) (7) were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM-Ham's F-12 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 2.5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies), insulin (5 μg/ml), transferrin (5 μg/ml), selenite (5 ng/ml), retinoic acid (0.1 μM), EGF (80 ng/ml) (Calbiochem, Billerica, MA), triiodothyronine (2 nM), hydrocortisone (1.1 μM), glutamine (5 mM), gentamicin (50 μg/ml), cholera toxin (8.4 ng/ml), and G418 (0.5 mg/ml) (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

Mice.

C57BL/6 (wild-type) and P2Y2R−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred at the Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center Animal Facility of the University of Missouri, Columbia, MO. Animals were housed in vented cages with 12:12-h light-dark cycles and received food and water ad libitum. All animals were handled using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Missouri.

Preparation of dispersed cell aggregates from mouse SMG.

Dispersed cell aggregates from the SMGs of wild-type C57BL/6 and P2Y2R−/− mice were prepared, as previously described (94). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and the SMGs were removed. The glands were finely minced and incubated in dispersion medium consisting of DMEM-Ham's F-12 medium (1:1), 0.2 mM CaCl2, 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 U/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Freehold, NJ), and 400 U/ml hyaluronidase at 37°C for 40 min with aeration (95% air and 5% CO2). Cell aggregates in dispersion medium were suspended by pipetting at 20, 30, and 40 min of the incubation period. The dispersed cell aggregates were washed with enzyme-free assay buffer (in mM: 120 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 15 HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 1% (vol/vol) FBS, filtered through nylon mesh, and cultured in DMEM-Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) containing 2.5% (vol/vol) FBS and the following supplements: retinoic acid (0.1 μM), EGF (80 ng/ml), triiodothyronine (2 nM), hydrocortisone (1.1 μM), glutamine (5 mM), insulin (5 μg/ml), transferrin (5 μg/ml), selenite (5 ng/ml), gentamicin (50 μg/ml), and cholera toxin (8.4 ng/ml). The cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Migration assay.

Par-C10 single-cell suspensions in DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) FBS were seeded (2 × 105 cells/well) on a 24-well plate coated with growth factor reduced (GFR) Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air for 4 h. Then, the cell culture plate was mounted on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E microscope equipped with a digital camera, a motorized x-y stage, an automatic shutter, and an in vivo incubation chamber (37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air). Within each well, a field of cells was located with a ×10 objective and marked for monitoring over the duration of the experiment using Nikon NIS-Elements imaging software. The exposure time was kept constant for all positions and all time points. Cells were treated with or without UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 ng/ml). In inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (1 μM) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), ADAM10/ADAM17 inhibitor TAPI-2 (10 μM) (Peptides International, Louisville, KY), α5β1 integrin blocking antibody (100 μg/ml) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), Cdc42 inhibitor ML141 (10 μM) (Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN), RhoA inhibitor SR3677 (10 μM) (Tocris Bioscience), MEK/ERK pathway inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) (Cell Signaling Technology) or JNK inhibitor SP600125 (10 μM) (Tocris Bioscience) for 2 h before UTP, EGF, or vehicle (basal) treatment. Unless otherwise noted, inhibitors at the concentrations employed had no effect on the responses measured under basal conditions. Transmitted light images of cells were obtained every 10 min for the time indicated. Cellular aggregation was monitored by manually counting the number of aggregation events, where one aggregation event was defined as the coalescence/fusion of two or more cells at the same time point. ZO-1 tight junction protein was detected in Par-C10 cell aggregates formed after 36 h using immunofluorescence as previously described (7).

For primary SMG cells isolated from wild-type and P2Y2R−/− mice, SMGs were enzymatically dispersed and incubated for 3 days (37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air) to allow the P2Y2R to upregulate. After 3 days, cells were serum-starved overnight and on day 4, cells were seeded on GFR-Matrigel for 8 h, treated with or without UTP, and monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging, as described above. In inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (1 μM) (Cell Signaling Technology) for 2 h before UTP or vehicle (basal) treatment. Primary cell migration was assessed by measuring the distance traveled from the origin, total distance traveled, and average velocity using the tracking software provided with the NIS-Elements imaging software.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Par-C10 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were seeded on 24-well culture dishes, grown to 70% confluence, and then incubated overnight in DMEM-Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) without serum. When indicated, the cells were pretreated with or without inhibitors for 2 h at 37°C before stimulation with agonists for the indicated times. Then, the medium was removed and 100 μl of 2× Laemmli lysis buffer [20 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.0, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, 4% (wt/vol) SDS, 0.01% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, and 100 mM dithiothreitol] were added. The samples were sonicated for 5 s with a Branson Sonifier 250 (microtip; output level, 5; duty cycle, 50%), heated at 95°C for 5 min, and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels. The proteins resolved on the gel were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked for 1 h with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (TBST). The blots were incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking solution or TBST with the following rabbit polyclonal antibodies used at 1:1,000 dilutions: anti-phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068) (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-ERK1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) as a loading control. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent, and the protein bands detected on X-ray film were quantified using a computer-driven scanner and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The intensities of phosphorylated protein bands in cells treated with agonists or other agents were normalized to total ERK1/2 and are expressed as a percentage of normalized data from untreated controls.

Cdc42 activation assay.

A Cdc42 activation assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) was used to assess Cdc42 activity according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, Par-C10 cells were cultured in 100-mm culture dishes and grown to 70% confluence. Then, cells were starved overnight in serum-free DMEM-Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) before being stimulated with UTP (100 μM) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were collected using 1× assay/lysis buffer (125 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 750 mM NaCl, 5% NP-40, 50 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with p21-activated kinase-1 p21-binding domain (PAK1 PBD) agarose beads, which bind the GTP-bound form of Cdc42. GTP-bound Cdc42 was analyzed by Western analysis using mouse monoclonal anti-rat Cdc42 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Cell Biolabs). The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:2,000 dilution) at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent, and the protein bands were detected on X-ray film.

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR analysis of P2Y2R mRNA expression.

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) from SMG aggregates cultured for 0, 24, 48, or 72 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% air. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of purified RNA using the Advantage RT for PCR kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA). Ten percent of the synthesized cDNA was used as a template in 25 μl real-time PCR reactions, and samples were run in duplicate for the P2Y2R target and the endogenous 18S RNA control. The relative levels of P2Y2R and 18S RNA in each sample were determined and are expressed as a ratio of P2Y2R to 18S RNA (normalized to 1) using Applied Biosystems software.

Intracellular free Ca2+ concentration measurements.

Changes in the intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in SMG cell aggregates were quantified as previously described (99). Briefly, dispersed SMG aggregates from wild-type or P2Y2R−/− mice were cultured for 72 h and loaded with 2 μM fura 2-AM (Calbiochem) for 30 min at 37°C in assay buffer (in mM: 120 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 15 HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA. Then, the SMG aggregates were washed and adhered to chambered coverslips coated with Cell-Tak (BD Biosciences) for an additional 30 min in the absence of fura 2-AM. SMG aggregates were stimulated with UTP (100 μM), and changes in the 340/380 nm excitation ratio (505 nm emission) were monitored using an InCyt dual-wavelength fluorescence imaging system (Intracellular Imaging, Cincinnati, OH). Fluorescence ratios were converted to [Ca2+]i (nM) using a standard curve created with known concentrations of Ca2+.

Statistical analysis.

The quantitative results are presented as the means ± SE of data from three or more experiments. Two-tailed t-test or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni or Dunnett's test was performed, as indicated, where P < 0.05 represents a significant difference.

RESULTS

P2Y2R activation enhances Par-C10 cell aggregation and the formation of acinar-like spheres.

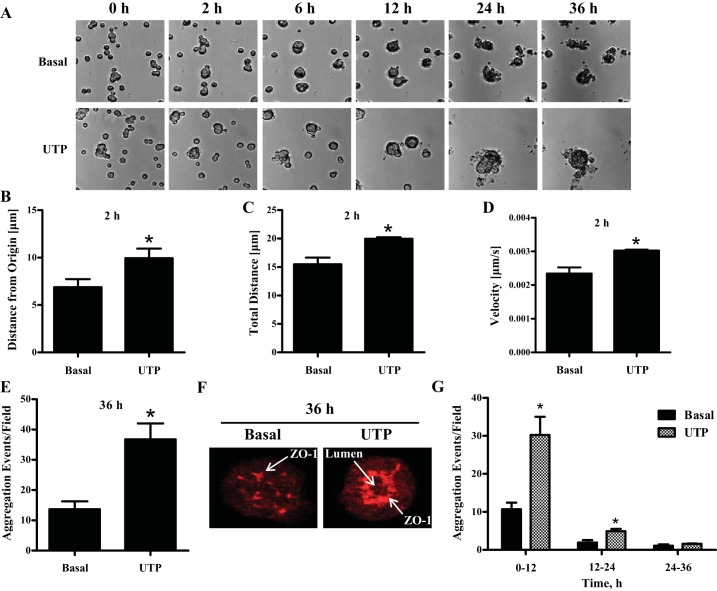

When plated on extracellular matrices, such as Matrigel, dispersed salivary epithelial cells isolated from embryonic mice (118) or adult humans (90) as well as cultured Par-C10 (7) and HSG (49) cells migrate towards each other and self-organize into aggregates that display structural and/or functional features similar to the native salivary gland. Since activation of the P2Y2R has been shown to enhance the migration of a variety of cell types (6, 117, 125), including epithelial cells (13, 68), we investigated whether P2Y2R activation enhances the migration, aggregation, and self-organization of salivary epithelial cells. Par-C10 single-cell suspensions seeded on GFR-Matrigel-coated 24-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well) were treated with or without UTP (100 μM), and cells were monitored for 36 h by time-lapse live cell imaging (Fig. 1A), as described in materials and methods. During the first 2 h of the time course, UTP-treated single Par-C10 cells showed enhanced migratory responses, as indicated by the distance that single cells traveled from the origin (Fig. 1B), the total distance that cells migrated (Fig. 1C), and the increase in the cell velocity (Fig. 1D). After 2 h, single Par-C10 cells began to form aggregates that were quantified, as described in materials and methods, where one aggregation event represents the coalescence/fusion of two or more cells at the same time point. UTP-treated Par-C10 cells exhibited enhanced aggregation (Fig. 1, A and E, and Supplemental Movies S1 and S2; Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the journal website) with 100% forming acinar-like spheres that display lumen formation and an organized distribution of the tight junction protein ZO-1 (Fig. 1F) at the end of 36 h. Although untreated (basal) Par-C10 cells can aggregate and express ZO-1, they did not form differentiated acinar-like spheres until ∼72 h in culture (data not shown), as previously described (7). Notably, the majority of aggregation events took place in the first 12 h after addition of UTP (Fig. 1G). Therefore, subsequent experiments investigating aggregation events were performed for 12 h.

Fig. 1.

UTP enhances Par-C10 cell aggregation and the formation of acinar-like spheres on growth factor reduced (GFR) Matrigel. A: Par-C10 single-cell suspensions were cultured on GFR-Matrigel for 4 h, then treated with or without UTP (100 μM) and monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging for 36 h, as described in materials and methods. B–D: the migration of single Par-C10 cells was monitored for 2 h, and the distance migrated from the origin (B), total distance traveled (C), and average velocity of single cells (D) were quantified with the tracking software provided with NIS-Elements imaging software. The data represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, significant increase over basal levels (two-tailed t-test). E: quantification of the number of aggregation events in response to UTP (100 μM) after 36 h. F: after 36 h, UTP-treated Par-C10 cell aggregates formed acinar-like spheres that display lumen formation and an organized distribution of the tight junction protein ZO-1 (red) detected by immunofluorescence using rabbit anti-ZO-1 antibody, as previously described (7), features not observed in the Par-C10 cell aggregates formed under basal conditions. G: quantification of the aggregation events from 0–12 h, 12–24 h, and 24–36 h indicates that the majority of aggregation events take place in the first 12 h with or without UTP treatment. The data shown represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, significant increase over basal levels (two-tailed t-test).

Inhibition of EGFR decreases UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation.

EGFR regulates a wide variety of cellular responses, including cell migration and differentiation (47, 57). In HSG cells, the P2Y2R has been shown to activate EGFR (94). To determine whether UTP-induced enhancement of Par-C10 cell aggregation is dependent on EGFR activation, cells were pretreated with AG1478 (1 μM), a potent EGFR inhibitor, 2 h prior to UTP stimulation. The results show that EGFR inhibition decreased UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation by 69% (Fig. 2A) and, as expected, completely inhibited EGF-induced enhancement of Par-C10 cell aggregation (Fig. 2A). EGFR inhibition also prevented UTP- and EGF-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR) activation decreases UTP-induced enhancement of Par-C10 cell aggregation. A: Par-C10 single-cell suspensions plated on GFR-Matrigel for 4 h were pretreated with or without the EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (1 μM) for 2 h, then incubated with or without UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 ng/ml). Par-C10 cell aggregates were monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging for 12 h. The data are expressed as percentages of the maximal number of aggregation events induced by UTP or EGF in the absence of AG1478 and represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant difference from the UTP- or EGF-induced response (two-tailed t-test). B: Par-C10 cells were serum-starved overnight, pretreated with or without AG1478 (1 μM) for 2 h, and then treated with or without UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 ng/ml). Five minutes after UTP or EGF addition, protein extracts were prepared from Par-C10 cell aggregates and EGFR phosphorylation (Y1068) was determined by Western analysis. Representative blots are shown (top). Quantification of protein levels in blots (bottom) was performed using Quantity One software, as described in materials and methods. The data are expressed as the percentage increase in EGFR phosphorylation induced by UTP or EGF, compared with untreated controls, and represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01, significant difference from the UTP- or EGF-induced response (two-tailed t-test).

Inhibition of ADAM10/ADAM17 metalloproteases decreases UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation and EGFR phosphorylation.

In HSG cells, the P2Y2R has been shown to activate EGFR via ADAM10 and ADAM17 metalloproteases (94) that promote shedding of EGF-like ligands, such as neuregulin, which bind to and activate members of the EGFR family. To determine whether ADAM10/ADAM17 are involved in the UTP-induced enhancement of Par-C10 cell aggregation, cells were pretreated with the selective ADAM10/ADAM17 inhibitor TAPI-2 (10 μM), which partially (52%) decreased UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation (Fig. 3A), whereas ADAM10/ADAM17 inhibition did not affect the EGF-induced increase in aggregation (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the role of metalloproteases in the P2Y2R-mediated generation of EGFR agonists (94), ADAM10/ADAM17 inhibition decreased UTP-induced, but not EGF-induced, phosphorylation of the EGFR (Fig. 3B). The partial loss of UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation by ADAM10/ADAM17 inhibition suggests that other P2Y2R-mediated signaling pathways contribute to the cell aggregation response.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of metalloproteases ADAM10/ADAM17 decreases UTP-induced enhancement of Par-C10 cell aggregation and EGFR phosphorylation. A: Par-C10 single-cell suspensions plated on GFR-Matrigel for 4 h were pretreated with or without the ADAM10/ADAM17 inhibitor TAPI-2 (10 μM) for 2 h, then incubated with or without UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 ng/ml). Par-C10 cell aggregates were monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging for 12 h. The data are expressed as percentages of the maximal number of aggregation events induced by UTP or EGF in the absence of TAPI-2 and represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. ***P < 0.001, significant difference from the UTP- or EGF-induced response (two-tailed t-test). B: Par-C10 cells were serum-starved overnight, pretreated with or without TAPI-2 (10 μM) for 2 h, and then treated with or without UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 ng/ml). Five minutes after UTP or EGF addition, protein extracts were prepared from Par-C10 cell aggregates and EGFR phosphorylation (Y1068) was determined by Western analysis. Representative blots are shown (top), where a black line represents noncontiguous lanes from the same gel. Quantification of protein levels in blots (bottom) was performed using Quantity One software, as described in materials and methods. The data are expressed as the percentage increase in EGFR phosphorylation induced by UTP or EGF, compared with untreated controls, and represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. **P < 0.01, significant difference from the UTP- or EGF-induced response (two-tailed t-test).

Inhibition of the α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 signaling pathway decreases UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation and EGFR phosphorylation.

The P2Y2R contains an extracellular-oriented RGD sequence that interacts with RGD-binding integrins (35) to activate Rho GTPases that regulate cell migration (6, 117). The RGD-binding α5β1 integrin has been shown to regulate SMG branching morphogenesis (96) and stimulate migration of a variety of cell types (16, 22, 42, 51, 69, 73, 115). To test whether UTP-induced Par-C10 cell migration and aggregation require activation of α5β1 integrin, cells were pretreated with α5β1 integrin function-blocking antibody (100 mg/ml) prior to addition of 100 μM UTP. Results indicate that inhibition of α5β1 integrin function decreased UTP-induced aggregation by 49%, but had no effect on the EGF-induced response (Fig. 4A). Integrin-dependent activation of the Rho GTPases Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA has been shown to modulate cytoskeletal reorganization and cell migration, where there is a reciprocal relationship between Cdc42/Rac1 and RhoA activities (32, 75, 97). Our results show that stimulation of Par-C10 cells with 100 μM UTP activates Cdc42 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4B, top). Inhibition of Cdc42 with the selective antagonist ML141 (10 μM) inhibited UTP-induced aggregation by 90% (Fig. 4B, bottom) and inhibited the UTP-induced phosphorylation of EGFR to a similar extent (Fig. 4D), but it had no effect on EGF-induced responses, which are independent of metalloproteases (Fig. 3) and α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 (Figs. 4, A, B, and D). However, inhibition of RhoA with SR3677 (10 μM) significantly increased basal cell aggregation by almost twofold and had no additional effect on the UTP- or the EGF-induced enhancement of Par-C10 cell aggregation (Fig. 4C). Inhibition of Rac1 using NSC23766 (100 μM) did not affect UTP-induced or basal Par-C10 cell aggregation (data not shown). These data suggest that the P2Y2R-mediated activation of the α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 signaling pathway enhances the self-organization of Par-C10 cells into acinar-like spheres through the activation of the EGFR pathway. Moreover, these data show that RhoA plays an inhibitory role in the basal aggregation of dispersed Par-C10 cells.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of the α5β1/Cdc42 signaling pathway decreases UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation and EGFR phosphorylation, whereas RhoA inhibition increases basal cell aggregation. Par-C10 single-cell suspensions were plated on GFR-Matrigel for 4 h, pretreated for 2 h with or without α5β1 integrin function-blocking antibody (100 μg/ml) (A), the Cdc42 inhibitor ML141 (10 μM) (B, bottom), or the RhoA inhibitor SR3677 (10 μM) (C). Cells were then treated with or without UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 ng/ml), as indicated, and cell aggregation was monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging for an additional 12 h. The data are expressed as percentages of the maximal number of aggregation events induced by UTP or EGF (A and B) or the total number of aggregation events (C). The data represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. A and B: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, significant difference from the UTP- or EGF-induced response (two-tailed t-test). C: two-way ANOVA was performed followed by the Bonferroni test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, significant difference in the number of aggregation events between SR3677-treated and untreated cells under basal conditions or SR3677-treated cells stimulated with or without UTP or EGF, as indicated. B, top: GTP binding by Cdc42 was determined in serum-starved Par-C10 cells treated with or without UTP (100 μM) for 1, 5, or 10 min, as described in materials and methods. D: Par-C10 cells were serum-starved overnight, pretreated with or without the Cdc42 inhibitor ML141 (10 μM) for 2 h, and then treated with or without UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 5 min. EGFR phosphorylation (Y1068) was determined by Western analysis. A representative blot is shown (top), where a black line represents noncontiguous lanes from the same gel. Quantification of protein levels in blots (bottom) was performed using Quantity One software, as described in materials and methods. The data are expressed as the percentage increase in EGFR phosphorylation induced by UTP, compared with untreated controls, and represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, significant difference from the UTP-induced response (two-tailed t-test).

UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation depends on the activation of JNK and ERK1/2.

The activation of the EGFR leads to downstream activation of the MAPKs ERK1/2 and JNK, a response shown to modulate cell migration (18). Initially, we determined that P2Y2R activation with 100 μM UTP stimulates the time-dependent phosphorylation of JNK and ERK1/2 in Par-C10 cells (Fig. 5A). Inhibition of JNK with 10 μM SP600125 or ERK1/2 with 10 μM U0126, a MEK inhibitor, decreased UTP-induced Par-C10 cell aggregation (Fig. 5B), suggesting that JNK and ERK1/2 are regulators of Par-C10 acinar-like sphere formation. The EGFR pathway is apparently involved in the regulation of JNK- and ERK1/2-dependent Par-C10 cell aggregation induced by 100 μM UTP, since inhibition of the EGFR with 1 μM AG1478 (Fig. 5C) significantly reduced UTP-induced JNK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Fig. 5.

UTP-induced enhancement of Par-C10 cell aggregation is dependent on the activation of JNK and ERK1/2 by the EGFR. A: Par-C10 cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with or without 100 μM UTP for 1, 5, 10, or 15 min. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), and ERK1/2 (loading control) were detected by Western analysis. B: Par-C10 single-cell suspensions plated on GFR-Matrigel for 4 h were pretreated with or without the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (10 μM) or the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) for 2 h. Cells were then treated with or without UTP (100 μM), and cell aggregation was monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging for 12 h. The data are expressed as percentages of the maximal number of aggregation events induced by UTP and represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant difference from the UTP-induced response (two-tailed t-test). C: Par-C10 cells were pretreated for 2 h with or without the EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (1 μM) then treated with or without UTP (100 μM) for 5 min. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), and ERK1/2 (loading control) were detected by Western analysis (representative blots are shown on the left, where a black line represents noncontiguous lanes from the same gel). Quantification of protein levels was performed (right), as described in materials and methods. The data are expressed as the percentage increase in JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) and ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) phosphorylation induced by UTP, compared with untreated control, and represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, significant difference from the UTP-induced response (two-tailed t-test).

UTP stimulates the migration of primary murine SMG cells from wild-type but not P2Y2R−/− mice.

To test whether the UTP-induced salivary epithelial cell migration and aggregation are mediated by the P2Y2R, SMGs from wild-type and P2Y2R−/− mice were isolated, enzymatically dispersed, and cultured for 3 days to allow for upregulation of the P2Y2R, as previously described (113). Similar to primary rat SMG cell aggregates (113), P2Y2R mRNA expression is upregulated with time in cells cultured from wild-type mice (Fig. 6A), consistent with an increase in the [Ca2+]i induced by UTP in these cells (Fig. 6B), responses not seen in SMG cell aggregates from P2Y2R−/− mice (data not shown). UTP (100 μM) stimulated the migration of SMG cell aggregates from wild-type but not P2Y2R−/− mice (Fig. 6C). UTP-induced migration of wild-type primary SMG cells occurred only during the first 4 h, as indicated by the distance that cell aggregates traveled from the origin (Fig. 6D), the total distance that cell aggregates migrated (Fig. 6E), and an increase in the velocity of the cell aggregates (Fig. 6F). A lack of these responses in SMG from P2Y2R−/− mice (Fig. 6, C–F) confirms that UTP-induced SMG cell migration is mediated by P2Y2R activation. Furthermore, inhibition of EGFR with 1 μM AG1478 impaired the UTP-induced migratory responses in wild-type primary SMG cells (Fig. 7), corroborating our findings using Par-C10 cells that the P2Y2R-induced responses are dependent on EGFR activation.

Fig. 6.

P2Y2 receptor (P2Y2R) mediates UTP-induced migration of primary submandibular gland (SMG) cell aggregates. A: P2Y2R mRNA was isolated from SMG cell aggregates from wild-type and P2Y2R−/− mice after 0, 24, 48, or 72 h in culture, as described in materials and methods. The data are expressed as fold increase in P2Y2R mRNA levels over the 0 time point and represent the means of ± SE of results from 4 experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, significant increase in P2Y2R mRNA expression, compared with the 0 time point (one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test). B: changes in the intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) induced by 100 μM UTP in SMG cell aggregates at 0 and 72 h in culture were determined, as described in materials and methods. The data represent the means ± SE of results from 7 experiments. ***P < 0.001, significant difference from the 0 time point (two-tailed t-test). C: primary SMGs isolated from wild-type and P2Y2R−/− mice were enzymatically dispersed and incubated for 3 days (37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air) to enable upregulation of the P2Y2R. After 3 days, cells were serum-starved overnight, seeded on GFR-Matrigel for 8 h, and treated with or without 100 μM UTP. Cell aggregates of similar size were monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging for 24 h, and the point of origin (arrow) and the migration path (red line) are indicated. D–F: quantification of the distance migrated from the origin (D), the total distance traveled (E), and the average velocity (F) of aggregates throughout the first 4 h of the time course was performed with the tracking software provided with NIS-Elements imaging software. The data represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, significant increase over basal levels (two-tailed t-test).

Fig. 7.

P2Y2R-induced migration of primary SMG cell aggregates is dependent on EGFR. Primary SMGs isolated from wild-type and P2Y2R−/− mice were enzymatically dispersed and incubated for 3 days (37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air) to enable upregulation of the P2Y2R. After 3 days, cells were serum-starved overnight, seeded on GFR-Matrigel for 8 h, and pretreated for 2 h with or without the EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (1 μM). Cells were then treated with or without UTP (100 μM). Cell aggregates of similar size were monitored by time-lapse live cell imaging. Quantification of the distance migrated from the origin (A), the total distance traveled (B), and the average velocity (C) of aggregates during the first 4 h of the time course was performed with the tracking software provided with NIS-Elements imaging software. The data represent the means ± SE of results from at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, significant decrease from basal levels (two-tailed t-test).

DISCUSSION

Recent progress has been made in the development of strategies for regeneration and engineering of a variety of tissues, including skin (79, 92), corneal epithelium (43), cartilage (85), bone (10, 11), bladder (77), and lacrimal (48) and salivary glands (83). Determining the capacity of dispersed cells or tissue fragments to reassemble into native structures and the underlying mechanisms involved should provide novel insights to improve tissue regeneration approaches. The capacity of dispersed salivary epithelial cells or salivary gland-derived progenitor cells to reassemble into acinar-like spheres or branching structures has been previously assessed (84, 90, 118), but little is known about the signaling events involved in these differentiation processes. In the present study, we determined that the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor (P2Y2R), known to be upregulated during salivary gland damage and disease (1, 99, 113), plays a role in the aggregation and self-organization of dispersed salivary epithelial cells into acinar-like spheres. Our in vitro data using the rat parotid acinar (Par-C10) cell line show that P2Y2R activation by UTP significantly enhances the migration, aggregation, and self-organization of dispersed Par-C10 cells into acinar-like spheres (Fig. 1, A–E, and Supplemental Movies S1 and S2) that display structural features and differentiation markers similar to those of acini in the native gland (Fig. 1F), as previously described (7). In addition, our ex vivo data show that P2Y2R deletion prevents the UTP-induced migration of primary murine SMG cell aggregates (Fig. 6), demonstrating that UTP-induced migratory responses of salivary epithelial cells are primarily mediated by P2Y2R activation.

In this paper, we demonstrate that UTP-induced enhancement of dispersed salivary epithelial cell aggregation occurs by two distinct signaling pathways coupled to activation of the P2Y2R: 1) the activation of metalloproteases (i.e., ADAM10/ADAM17) and 2) the activation of the α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 Rho GTPase pathway, major signaling pathways that activate various physiological processes (5, 95, 101, 108, 109, 116, 123, 128). Both of these signaling pathways activate EGFR, which leads to the downstream activation of JNK and ERK1/2 that we demonstrate increases UTP-induced aggregation of Par-C10 cells. A schematic outlining these P2Y2R-mediated signaling pathways involved in salivary epithelial cell migration and aggregation is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Proposed mechanisms for P2Y2R-mediated enhancement of salivary epithelial cell aggregation and formation of acinar-like spheres. The P2Y2R enhances the aggregation of dispersed salivary epithelial cells into acinar-like spheres through the activation of the EGFR and subsequent downstream activation of JNK and ERK1/2. P2Y2R mediates EGFR activation through two distinct pathways: the first pathway involves P2Y2R-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteases (i.e., ADAM10/ADAM17), which cleave membrane-bound EGFR ligands (94) leading to the activation of the EGFR, and the second pathway involves P2Y2R-mediated activation of the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) binding α5β1 integrin, which leads to activation of the Rho GTPase Cdc42 that also activates the EGFR. RhoA activation has an inhibitory effect on the basal aggregation of dispersed Par-C10 salivary epithelial cells. P2Y2R, P2Y2 receptor; ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase; GFR, growth factor receptor; NRG, neuregulin; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; RhoA, Ras homolog gene family member A; Cdc42, cell division control protein 42 homolog.

It is well-established that the EGFR and its signaling pathways are critical for stimulating cell migration and the regeneration of a variety of tissues (30, 37, 57, 58, 81, 91). In salivary tissue reconstitution studies, exogenous EGF has been shown to be crucial for the self-organization of dispersed salivary gland-derived progenitor cells into branching structures (84). Several studies have shown that P2Y2R activation enhances epithelial cell migration, thereby accelerating wound healing and tissue regeneration (9, 12–14, 26, 62, 68) in part due to transactivation of the EGFR (12, 14, 62, 68). Our group has previously shown that the P2Y2R mediates transactivation of the EGFR in HSG cells through metalloprotease-dependent neuregulin release (94). In the present study, we demonstrate that the ADAM10/ADAM17/EGFR signaling pathway is required for P2Y2R-mediated aggregation of salivary epithelial cells (Figs. 2, 3, and 8), suggesting P2Y2R as a potential therapeutic target for promoting salivary gland regeneration or the ex vivo bioengineering of salivary glands, which represent promising alternative approaches to replace the current ineffective therapies for hyposalivation resulting from SS or irradiation therapy for head and neck cancers.

In addition to metalloprotease-dependent activation of the EGFR, the P2Y2R can activate EGFR through the α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 signaling pathway (Fig. 4). Our group has previously shown that the P2Y2R contains an RGD motif in its first extracellular loop that enables receptor interaction with RGD-binding αVβ3/5 integrins to stimulate cell migration (6, 26, 64, 117). However, P2Y2R interactions with other RGD-binding integrins have not been previously reported. In this study, we show for the first time that the α5β1 integrin, a known mediator of SMG branching morphogenesis (96), cell migration, and tissue regeneration (16, 40–42, 51, 66, 67, 69, 73, 78, 88, 115, 121, 127), also plays a role in P2Y2R-mediated salivary epithelial cell aggregation (Fig. 4A). We also have shown that the P2Y2R/αV integrin interaction leads to the activation of Rac (6), a Rho GTPase critical for regulating cell migration (39, 44–46, 93, 98), epithelial morphogenesis (44, 114), and salivary acinar formation (23). In this study, we found no evidence that Rac1 is required for P2Y2R-mediated salivary epithelial cell aggregation (data not shown), but rather Cdc42, another Rho GTPase known to regulate cell migration (38, 39, 44–46, 93, 98) and tissue regeneration (89, 126), regulates the aggregatory response to P2Y2R activation (Fig. 4B). Previous reports from our lab have linked P2Y2R-mediated cell migration to the activation of the Rho GTPase RhoA, as well as Rac1 (6, 64, 74, 103). Interestingly, RhoA inhibition in Par-C10 salivary epithelial cells increased basal cell aggregation by almost twofold and had no additional effect on the UTP- or EGF-induced enhancement of cell aggregation (Fig. 4C), suggesting that RhoA GTPase is a negative regulator of migratory responses in these cells. A reciprocal relationship between Cdc42 and RhoA has recently been described for mammary epithelial acinar morphogenesis (32). In contrast, another study has shown that inhibition of RhoA does not affect acinus formation by HSG cells (23).

It is well-established that MAPKs, including JNK and ERK1/2, regulate cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation (15, 18, 21, 36, 63, 72, 86, 102, 120), processes important for salivary gland morphogenesis (60, 70) and regeneration of a wide variety of tissues (19, 24, 50, 53, 54, 56, 65, 71, 80, 100, 105, 107, 111, 122, 124). The P2Y2R-mediated activation of ERK1/2 has been reported in HSG cells (94), corneal epithelial cells (13), and human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC) (29). However, the ability of the P2Y2R to activate JNK has only been reported for HCAEC (29) and primary rat hepatocytes (110). Our data indicate that the P2Y2R agonist UTP activates JNK and ERK1/2 (Fig. 5A) through the canonical EGFR pathway (Fig. 5C) to enhance salivary epithelial cell aggregation and self-organization (Fig. 5B).

Growth factor receptors and integrins represent major signaling pathways that interact at different levels to regulate various physiological processes (33, 55). The present study indicates that the P2Y2R transactivates the EGFR through the α5β1 integrin/Cdc42 signaling pathway as well as the activation of the metalloproteases ADAM10/ADAM17, enabling extracellular nucleotides to enhance the aggregation and self-organization of dispersed salivary epithelial cells into acinar-like spheres on GFR-Matrigel by increasing the activities of the MAPKs JNK and ERK1/2. Further work is needed to investigate whether other P2Y2R signaling pathways are involved in acinar-like sphere formation, such as the activation of the MAPK p38 that has been reported to promote the regeneration of salivary glands (24), skeletal muscle (17), and sciatic nerve (61) and to regulate corneal epithelial wound healing (105). Other potential P2Y2R signaling pathways involved in salivary epithelial cell migration include the activation of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-K)/protein kinase B (Akt) (117) and the Go signaling pathway (6). Understanding the signaling events responsible for the aggregation and self-organization of dispersed salivary epithelial cells into acinar-like spheres should provide insights into novel approaches for the bioengineering of salivary glands (83) and should lead to better regenerative/replacement strategies for salivary glands damaged in human autoimmune diseases or as an unintended side effect of radiation treatments for head and neck cancers.

GRANTS

This project was supported by NIH/NIDCR Grant DE-007389. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research or the National Institutes of Health or the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.G.E., J.M.C., L.T.W., L.E., and G.A.W. conceived and designed the research; F.G.E. and J.M.C. performed experiments; F.G.E. and J.M.C. analyzed data; F.G.E., J.M.C., L.T.W., M.G.K., M.J.P., L.E., and G.A.W. interpreted results of experiments; F.G.E. and J.M.C. prepared figures; F.G.E. and J.M.C. drafted manuscript; F.G.E., J.M.C., L.T.W., M.G.K., M.J.P., L.E., and G.A.W. edited and revised manuscript; F.G.E., J.M.C., L.T.W., M.G.K., M.J.P., L.E., and G.A.W. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn JS, Camden JM, Schrader AM, Redman RS, Turner JT. Reversible regulation of P2Y2 nucleotide receptor expression in the duct-ligated rat submandibular gland. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C286–C294, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson J, Fox P. Salivary gland dysfunction. Clin Geriatr Med 8: 499–511, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson JC, Baum BJ. Salivary enhancement: current status and future therapies. J Dent Educ 65: 1096–1101, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson JC, Wu AJ. Salivary gland dysfunction: causes, symptoms, treatment. J Am Dent Assoc 125: 409–416, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auer KL, Contessa J, Brenz-Verca S, Pirola L, Rusconi S, Cooper G, Abo A, Wymann MP, Davis RJ, Birrer M. The Ras/Rac1/Cdc42/SEK/JNK/c-Jun cascade is a key pathway by which agonists stimulate DNA synthesis in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Mol Biol Cell 9: 561–573, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagchi S, Liao Z, Gonzalez FA, Chorna NE, Seye CI, Weisman GA, Erb L. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor interacts with αV integrins to activate Go and induce cell migration. J Biol Chem 280: 39050–39057, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker OJ, Schulz DJ, Camden JM, Liao Z, Peterson TS, Seye CI, Petris MJ, Weisman GA. Rat parotid gland cell differentiation in three-dimensional culture. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16: 1135–1144, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beldi G, Enjyoji K, Wu Y, Miller L, Banz Y, Sun X, Robson SC. The role of purinergic signaling in the liver and in transplantation: effects of extracellular nucleotides on hepatic graft vascular injury, rejection and metabolism. Front Biosci 13: 2588–2603, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belete HA, Hubmayr RD, Wang S, Singh RD. The role of purinergic signaling on deformation induced injury and repair responses of alveolar epithelial cells. PLos One 6: e27469, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhumiratana S, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Concise review: personalized human bone grafts for reconstructing head and face. Stem Cells Transl Med 1: 64–69, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boeckel DG, Shinkai RSA, Grossi ML, Teixeira ER. Cell culture-based tissue engineering as an alternative to bone grafts in implant dentistry: a literature review. J Oral Implantol 38 Spec No: 538–545, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boucher I, Kehasse A, Marcincin M, Rich C, Rahimi N, Trinkaus-Randall V. Distinct activation of epidermal growth factor receptor by UTP contributes to epithelial cell wound repair. Am J Pathol 178: 1092–1105, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boucher I, Rich C, Lee A, Marcincin M, Trinkaus-Randall V. The P2Y2 receptor mediates the epithelial injury response and cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C411–C421, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boucher I, Yang L, Mayo C, Klepeis V, Trinkaus-Randall V. Injury and nucleotides induce phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor: MMP and HB-EGF dependent pathway. Exp Eye Res 85: 130–141, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cargnello M, Roux PP. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 75: 50–83, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caswell PT, Spence HJ, Parsons M, White DP, Clark K, Cheng KW, Mills GB, Humphries MJ, Messent AJ, Anderson KI, McCaffrey MW, Ozanne BW, Norman JC. Rab25 associates with α5β1 integrin to promote invasive migration in three-dimensional microenvironments. Dev Cell 13: 496–510, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen SE, Jin B, Li YP. TNF-α regulates myogenesis and muscle regeneration by activating p38 MAPK. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1660–C1671, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z, Gibson TB, Robinson F, Silvestro L, Pearson G, Xu BE, Wright A, Vanderbilt C, Cobb MH. MAP kinases. Chem Rev 101: 2449–2476, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chierzi S, Ratto GM, Verma P, Fawcett JW. The ability of axons to regenerate their growth cones depends on axonal type and age, and is regulated by calcium, cAMP and ERK. Eur J Neurosci 21: 2051–2062, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen R, Shainberg A, Hochhauser E, Cheporko Y, Tobar A, Birk E, Pinhas L, Leipziger J, Don J, Porat E. UTP reduces infarct size and improves mice heart function after myocardial infarct via P2Y2 receptor. Biochem Pharmacol 82: 1126–1133, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coso OA. Signaling from the small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42 to the c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase pathway. A role for mixed lineage kinase 3/protein-tyrosine kinase 1, a novel member of the mixed lineage kinase family. J Biol Chem 271: 27225–27228, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox EA, Sastry SK, Huttenlocher A. Integrin-mediated adhesion regulates cell polarity and membrane protrusion through the Rho family of GTPases. Mol Biol Cell 12: 265–277, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crema VO, Hamassaki DE, Santos MF. Small Rho GTPases are important for acinus formation in a human salivary gland cell line. Cell Tissue Res 325: 493–500, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dang H, Elliott JJ, Lin AL, Zhu B, Katz MS, Yeh CK. Mitogen-activated protein kinase upregulation and activation during rat parotid gland atrophy and regeneration: role of epidermal growth factor and β2-adrenergic receptors. Differentiation 76: 546–557, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Almeida PDV, Gregio A, Machado M, De Lima A, Azevedo LR. Saliva composition and functions: a comprehensive review. J Contemp Dent Pract 9: 72–80, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degagné E, Degrandmaison J, Grbic DM, Vinette V, Arguin G, Gendron FP. P2Y2 receptor promotes intestinal microtubule stabilization and mucosal re-epithelization in experimental colitis. J Cell Physiol 228: 99–109, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degagné E, Grbic DM, Dupuis AA, Lavoie EG, Langlois C, Jain N, Weisman GA, Sévigny J, Gendron FP. P2Y2 receptor transcription is increased by NF-κB and stimulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression and PGE2 released by intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol 183: 4521–4529, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delporte C, O'Connell BC, He X, Lancaster HE, O'Connell AC, Agre P, Baum BJ. Increased fluid secretion after adenoviral-mediated transfer of the aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated rat salivary glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 3268–3273, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding L, Ma W, Littmann T, Camp R, Shen J. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor mediates tissue factor expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 286: 27027–27038, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dise RS, Frey MR, Whitehead RH, Polk DB. Epidermal growth factor stimulates Rac activation through Src and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to promote colonic epithelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G276–G285, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodds MW, Johnson DA, Yeh CK. Health benefits of saliva: a review. J Dent 33: 223–233, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan L, Chen G, Virmani S, Ying G, Raja SM, Chung BM, Rainey MA, Dimri M, Ortega-Cava CF, Zhao X, Clubb RJ, Tu C, Reddi AL, Naramura M, Band V, Band H. Distinct roles for Rho versus Rac/Cdc42 GTPases downstream of Vav2 in regulating mammary epithelial acinar architecture. J Biol Chem 285: 1555–1568, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eliceiri BP. Integrin and growth factor receptor crosstalk. Circ Res 89: 1104–1110, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erb L, Liao Z, Seye CI, Weisman GA. P2 receptors: intracellular signaling. Pflügers Arch 452: 552–562, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erb L, Liu J, Ockerhausen J, Kong Q, Garrad RC, Griffin K, Neal C, Krugh B, Santiago-Pérez LI, González FA. An RGD sequence in the P2Y2 receptor interacts with αVβ3 integrins and is required for Go-mediated signal transduction. J Cell Biol 153: 491–502, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fanger GR, Johnson NL, Johnson GL. MEK kinases are regulated by EGF and selectively interact with Rac/Cdc42. EMBO J 16: 4961–4972, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frey MR, Golovin A, Polk DB. Epidermal growth factor-stimulated intestinal epithelial cell migration requires Src family kinase-dependent p38 MAPK signaling. J Biol Chem 279: 44513–44521, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friesland A, Zhao Y, Chen YH, Wang L, Zhou H, Lu Q. Small molecule targeting Cdc42-intersectin interaction disrupts Golgi organization and suppresses cell motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 1261–1266, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukata M, Nakagawa M, Kaibuchi K. Roles of Rho-family GTPases in cell polarisation and directional migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 590–597, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardiner NJ. Integrins and the extracellular matrix: key mediators of development and regeneration of the sensory nervous system. Dev Neurobiol 71: 1054–1072, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giros A, Grgur K, Gossler A, Costell M. α5β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to fibronectin is required for axis elongation and somitogenesis in mice. PLos One 6: e22002, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gleeson LM, Chakraborty C, McKinnon T, Lala PK. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 stimulates human trophoblast migration by signaling through α5β1 integrin via mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 2484–2493, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griffith M, Polisetti N, Kuffova L, Gallar J, Forrester J, Vemuganti GK, Fuchsluger TA. Regenerative approaches as alternatives to donor allografting for restoration of corneal function. Ocul Surf 10: 170–183, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall A. Rho family GTPases. Biochem Soc Trans 40: 1378–1382, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science 279: 509–514, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanna S, El-Sibai M. Signaling networks of Rho GTPases in cell motility. Cell Signal 25: 1955–1961, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herbst RS. Review of epidermal growth factor receptor biology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 59: 21–26, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirayama M, Ogawa M, Oshima M, Sekine Y, Ishida K, Yamashita K, Ikeda K, Shimmura S, Kawakita T, Tsubota K, Tsuji T. Functional lacrimal gland regeneration by transplantation of a bioengineered organ germ. Nat Commun 4: 2497, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffman MP, Kibbey MC, Letterio JJ, Kleinman HK. Role of laminin-1 and TGF-β3 in acinar differentiation of a human submandibular gland cell line (HSG). J Cell Sci 109: 2013–2021, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hollis ER, 2nd, Jamshidi P, Low K, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Induction of corticospinal regeneration by lentiviral trkB-induced ERK activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 7215–7220, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hotchkiss KA, Ashton AW, Schwartz EL. Thymidine phosphorylase and 2-deoxyribose stimulate human endothelial cell migration by specific activation of the integrins α5β1 and αVβ3. J Biol Chem 278: 19272–19279, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Humphrey SP, Williamson RT. A review of saliva: normal composition, flow, and function. J Prosthet Dent 85: 162–169, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iimuro Y, Fujimoto J. TLRs, NF-κB, JNK, and liver regeneration. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2010: 598109, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishizuka S, Yano T, Hagiwara K, Sone M, Nihei H, Ozasa H, Horikawa S. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediates renal regeneration in rats with myoglobinuric acute renal injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 254: 88–92, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ivaska J, Heino J. Cooperation between integrins and growth factor receptors in signaling and endocytosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 27: 291–320, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Javelaud D, Laboureau J, Gabison E, Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. Disruption of basal JNK activity differentially affects key fibroblast functions important for wound healing. J Biol Chem 278: 24624–24628, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jorissen R. Epidermal growth factor receptor: mechanisms of activation and signalling. Exp Cell Res 284: 31–53, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joslin EJ, Opresko LK, Wells A, Wiley HS, Lauffenburger DA. EGF-receptor-mediated mammary epithelial cell migration is driven by sustained ERK signaling from autocrine stimulation. J Cell Sci 120: 3688–3699, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kagami H, Wang S, Hai B. Restoring the function of salivary glands. Oral Dis 14: 15–24, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kashimata M, Sayeed S, Ka A, Onetti-Muda A, Sakagami H, Faraggiana T, Gresik EW. The ERK-1/2 signaling pathway is involved in the stimulation of branching morphogenesis of fetal mouse submandibular glands by EGF. Dev Biol 220: 183–196, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kato N, Matsumoto M, Kogawa M, Atkins GJ, Findlay DM, Fujikawa T, Oda H, Ogata M. Critical role of p38 MAPK for regeneration of the sciatic nerve following crush injury in vivo. J Neuroinflammation 10: 1, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kehasse A, Rich CB, Lee A, McComb ME, Costello CE, Trinkaus-Randall V. Epithelial wounds induce differential phosphorylation changes in response to purinergic and EGF receptor activation. Am J Pathol 183: 1841–1852, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keshet Y, Seger R. The MAP kinase signaling cascades: a system of hundreds of components regulates a diverse array of physiological functions. Methods Mol Biol 661: 3–38, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim HJ, Ajit D, Peterson TS, Wang Y, Camden JM, Gibson Wood W, Sun GY, Erb L, Petris M, Weisman GA. Nucleotides released from Aβ1–42-treated microglial cells increase cell migration and Aβ1–42 uptake through P2Y2 receptor activation. J Neurochem 121: 228–238, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim M, McGinnis W. Phosphorylation of Grainy head by ERK is essential for wound-dependent regeneration but not for development of an epidermal barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 650–655, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiwanuka E, Andersson L, Caterson EJ, Junker JP, Gerdin B, Eriksson E. CCN2 promotes keratinocyte adhesion and migration via integrin α5β1. Exp Cell Res 319: 2938–2946, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klein S, de Fougerolles AR, Blaikie P, Khan L, Pepe A, Green CD, Koteliansky V, Giancotti FG. α5β1 integrin activates an NF-κB-dependent program of gene expression important for angiogenesis and inflammation. Mol Cell Biol 22: 5912–5922, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klepeis VE, Weinger I, Kaczmarek E, Trinkaus-Randall V. P2Y receptors play a critical role in epithelial cell communication and migration. J Cell Biochem 93: 1115–1133, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koivisto L, Grenman R, Heino J, Larjava H. Integrins α5β1, αVβ1, and αVβ6 collaborate in squamous carcinoma cell spreading and migration on fibronectin. Exp Cell Res 255: 10–17, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koyama N, Kashimata M, Sakashita H, Sakagami H, Gresik EW. EGF-stimulated signaling by means of PI3K, PLCγ1, and PKC isozymes regulates branching morphogenesis of the fetal mouse submandibular gland. Dev Dyn 227: 216–226, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kunduzova OR, Bianchi P, Pizzinat N, Escourrou G, Seguelas MH, Parini A, Cambon C. Regulation of JNK/ERK activation, cell apoptosis, and tissue regeneration by monoamine oxidases after renal ischemia-reperfusion. FASEB J 16: 1129–1131, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levi NL, Hanoch T, Benard O, Rozenblat M, Harris D, Reiss N, Naor Z, Seger R. Stimulation of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) by gonadotropin-releasing hormone in pituitary αT3–1 cell line is mediated by protein kinase C, c-Src, and Cdc42. Mol Endocrinol 12: 815–824, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li R, Maminishkis A, Zahn G, Vossmeyer D, Miller SS. Integrin α5β1 mediates attachment, migration, and proliferation in human retinal pigment epithelium: relevance for proliferative retinal disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50: 5988–5996, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liao Z, Seye CI, Weisman GA, Erb L. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor requires interaction with αV integrins to access and activate G12. J Cell Sci 120: 1654–1662, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lim L. Networking of Rho GTPases in regulating morphology: the role of effectors and regulators. Biol Cell 91: 546–548, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu J, Liao Z, Camden J, Griffin KD, Garrad RC, Santiago-Perez LI, Gonzalez FA, Seye CI, Weisman GA, Erb L. Src homology 3 binding sites in the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor interact with Src and regulate activities of Src, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2, and growth factor receptors. J Biol Chem 279: 8212–8218, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ludlow JW, Kelley RW, Bertram TA. The future of regenerative medicine: urinary system. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 18: 218–224, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ly DP, Corbett SA. The integrin α5β1 regulates αVβ3-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. J Surg Res 123: 200–205, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma L, Gao C, Mao Z, Zhou J, Shen J, Hu X, Han C. Collagen/chitosan porous scaffolds with improved biostability for skin tissue engineering. Biomaterials 24: 4833–4841, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Napoli I, Noon LA, Ribeiro S, Kerai AP, Parrinello S, Rosenberg LH, Collins MJ, Harrisingh MC, White IJ, Woodhoo A, Lloyd AC. A central role for the ERK-signaling pathway in controlling Schwann cell plasticity and peripheral nerve regeneration in vivo. Neuron 73: 729–742, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Natarajan A, Wagner B, Sibilia M. The EGF receptor is required for efficient liver regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 17081–17086, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O'Connell AC, Baccaglini L, Fox PC, O'Connell BC, Kenshalo D, Oweisy H, Hoque A, Sun D, Herscher LL, Braddon VR. Safety and efficacy of adenovirus-mediated transfer of the human aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated parotid glands of non-human primates. Cancer Gene Ther 6: 505–513, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ogawa M, Oshima M, Imamura A, Sekine Y, Ishida K, Yamashita K, Nakajima K, Hirayama M, Tachikawa T, Tsuji T. Functional salivary gland regeneration by transplantation of a bioengineered organ germ. Nat Commun 4: 2498, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Okumura K, Shinohara M, Endo F. Capability of tissue stem cells to organize into salivary rudiments. Stem Cells Int 2012: 502136, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oldershaw RA. Cell sources for the regeneration of articular cartilage: the past, the horizon and the future. Int J Exp Pathol 93: 389–400, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pearson G, Robinson F, Gibson TB, Xu B, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev 22: 153–183, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Peterson TS, Camden JM, Wang Y, Seye CI, Wood WG, Sun GY, Erb L, Petris MJ, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor-mediated responses in brain cells. Mol Neurobiol 41: 356–366, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pickering JG, Chow LH, Li S, Rogers KA, Rocnik EF, Zhong R, Chan B. α5β1 integrin expression and luminal edge fibronectin matrix assembly by smooth muscle cells after arterial injury. Am J Pathol 156: 453–465, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pothula S, Bazan HE, Chandrasekher G. Regulation of Cdc42 expression and signaling is critical for promoting corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 5343–5352, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pradhan S, Liu C, Zhang C, Jia X, Farach-Carson MC, Witt RL. Lumen formation in three-dimensional cultures of salivary acinar cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142: 191–195, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Prenzel N, Fischer O, Streit S, Hart S, Ullrich A. The epidermal growth factor receptor family as a central element for cellular signal transduction and diversification. Endocr Relat Cancer 8: 11–31, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Priya SG, Jungvid H, Kumar A. Skin tissue engineering for tissue repair and regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 14: 105–118, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol 265: 23–32, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ratchford AM, Baker OJ, Camden JM, Rikka S, Petris MJ, Seye CI, Erb L, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors mediate metalloprotease-dependent phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB3 in human salivary gland cells. J Biol Chem 285: 7545–7555, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rul W, Zugasti O, Roux P, Peyssonnaux C, Eychene A, Franke TF, Lenormand P, Fort P, Hibner U. Activation of ERK, controlled by Rac1 and Cdc42 via Akt, is required for anoikis. Ann NY Acad Sci 973: 145–148, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sakai T, Larsen M, Yamada KM. Fibronectin requirement in branching morphogenesis. Nature 423: 876–881, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sander EE, Jean P, van Delft S, van der Kammen RA, Collard JG. Rac downregulates Rho activity: reciprocal balance between both GTPases determines cellular morphology and migratory behavior. J Cell Biol 147: 1009–1022, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schmitz AA, Govek EE, Bottner B, Van Aelst L. Rho GTPases: signaling, migration, invasion. Exp Cell Res 261: 1–12, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schrader AM, Camden JM, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor upregulation in submandibular gland cells from the NOD. B10 mouse model of Sjögren's syndrome. Arch Oral Biol 50: 533–540, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schwabe RF, Bradham CA, Uehara T, Hatano E, Bennett BL, Schoonhoven R, Brenner DA. c-Jun-N-terminal kinase drives cyclin D1 expression and proliferation during liver regeneration. Hepatology 37: 824–832, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schwartz MA, Shattil SJ. Signaling networks linking integrins and Rho family GTPases. Trends Biochem Sci 25: 388–391, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J 9: 726–735, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seye CI, Yu N, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Weisman GA. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor mediates vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression through interaction with VEGF receptor-2 (KDR/Flk-1). J Biol Chem 279: 35679–35686, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shan Z, Li J, Zheng C, Liu X, Fan Z, Zhang C, Goldsmith CM, Wellner RB, Baum BJ, Wang S. Increased fluid secretion after adenoviral-mediated transfer of the human aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated miniature pig parotid glands. Mol Ther 11: 444–451, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sharma GD, He J, Bazan HE. p38 and ERK1/2 coordinate cellular migration and proliferation in epithelial wound healing: evidence of crosstalk activation between MAP kinase cascades. J Biol Chem 278: 21989–21997, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ship J. Diagnosing, managing, and preventing salivary gland disorders. Oral Dis 8: 77–89, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Spence JR, Madhavan M, Aycinena JC, Del Rio-Tsonis K. Retina regeneration in the chick embryo is not induced by spontaneous Mitf downregulation but requires FGF/FGFR/MEK/ERK dependent upregulation of Pax6. Mol Vis 13: 57–65, 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Su JL, Lin MT, Hong CC, Chang CC, Shiah SG, Wu CW, Chen ST, Chau YP, Kuo ML. Resveratrol induces FasL-related apoptosis through Cdc42 activation of ASK1/JNK-dependent signaling pathway in human leukemia HL-60 cells. Carcinogenesis 26: 1–10, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Szczur K, Xu H, Atkinson S, Zheng Y, Filippi MD. Rho GTPase Cdc42 regulates directionality and random movement via distinct MAPK pathways in neutrophils. Blood 108: 4205–4213, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thevananther S, Sun H, Li D, Arjunan V, Awad SS, Wyllie S, Zimmerman TL, Goss JA, Karpen SJ. Extracellular ATP activates c-jun N-terminal kinase signaling and cell cycle progression in hepatocytes. Hepatology 39: 393–402, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tonges L, Planchamp V, Koch JC, Herdegen T, Bahr M, Lingor P. JNK isoforms differentially regulate neurite growth and regeneration in dopaminergic neurons in vitro. J Mol Neurosci 45: 284–293, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Turner JT, Redman RS, Camden JM, Landon LA, Quissell DO. A rat parotid gland cell line, Par-C10, exhibits neurotransmitter-regulated transepithelial anion secretion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 275: C367–C374, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Turner JT, Weisman GA, Camden JM. Upregulation of P2Y2 nucleotide receptors in rat salivary gland cells during short-term culture. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C1100–C1107, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Van Aelst L, Symons M. Role of Rho family GTPases in epithelial morphogenesis. Genes Dev 16: 1032–1054, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Veevers-Lowe J, Ball SG, Shuttleworth A, Kielty CM. Mesenchymal stem cell migration is regulated by fibronectin through α5β1-integrin-mediated activation of PDGFR-β and potentiation of growth factor signals. J Cell Sci 124: 1288–1300, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang L, Yang L, Burns K, Kuan CY, Zheng Y. Cdc42GAP regulates c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-mediated apoptosis and cell number during mammalian perinatal growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 13484–13489, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang M, Kong Q, Gonzalez FA, Sun G, Erb L, Seye C, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor interaction with αV integrin mediates astrocyte migration. J Neurochem 95: 630–640, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wei C, Larsen M, Hoffman MP, Yamada KM. Self-organization and branching morphogenesis of primary salivary epithelial cells. Tissue Eng 13: 721–735, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Weinger I, Klepeis VE, Trinkaus-Randall V. Tri-nucleotide receptors play a critical role in epithelial cell wound repair. Purinergic Signal 1: 281–292, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wu WS, Wu JR, Hu CT. Signal crosstalks for sustained MAPK activation and cell migration: the potential role of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Metastasis Rev 27: 303–314, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yanagida H, Tanaka J, Maruo S. Immunocytochemical localization of a cell adhesion molecule, integrin α5β1, in nerve growth cones. J Orthop Sci 4: 353–360, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yano T, Yano Y, Yuasa M, Horikawa S, Ozasa H, Okada S, Otani S, Hagiwara K. The repetitive activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase is required for renal regeneration in rat. Life Sci 62: 2341–2347, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yeh CK, Ghosh PM, Dang H, Liu Q, Lin AL, Zhang BX, Katz MS. β-Adrenergic-responsive activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases in salivary cells: role of epidermal growth factor receptor and cAMP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1357–C1366, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yin J, Yu FS. ERK1/2 mediate wounding- and G-protein-coupled receptor ligands-induced EGFR activation via regulating ADAM17 and HB-EGF shedding. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50: 132–139, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yu N, Erb L, Shivaji R, Weisman GA, Seye CI. Binding of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor to filamin A regulates migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 102: 581–588, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yuan H, Zhang H, Wu X, Zhang Z, Du D, Zhou W, Zhou S, Brakebusch C, Chen Z. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of Cdc42 results in delayed liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology 49: 240–249, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zech T, Calaminus SD, Caswell P, Spence HJ, Carnell M, Insall RH, Norman J, Machesky LM. The Arp2/3 activator WASH regulates α5β1-integrin-mediated invasive migration. J Cell Sci 124: 3753–3759, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhong B, Jiang K, Gilvary DL, Epling-Burnette PK, Ritchey C, Liu J, Jackson RJ, Hong-Geller E, Wei S. Human neutrophils utilize a Rac/Cdc42-dependent MAPK pathway to direct intracellular granule mobilization toward ingested microbial pathogens. Blood 101: 3240–3248, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data