Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a complex group of malignancies with variable prognosis and response to treatment. For pancreatic neuroendocrine and carcinoid tumors, traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies have demonstrated minimal activity. Current approaches for treatment of metastatic disease use a combination of loco-regional and targeted biological therapies. Clinical trials remain critical for evaluation of new and promising therapeutic options for patients with NETs.

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumors, somatostatin, chemoembolization

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) comprise a spectrum of neoplasms with variable biological behavior and prognosis. Derived from the neural crest origin, NETs originate from many organs, including small intestine, appendix, stomach, colon or rectum, pancreas, lung and ovary. The historical nomenclature describing NETs based on site of origin is often confusing. Islet cell carcinoma or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET) refers to NETs arising from pancreatic endocrine cells. The term carcinoid tumor is best used to describe NETs, which arise from aerodigestive tissues and have well- or moderately differentiated histology. Some refer to NETs with moderately differentiated grade as atypical carcinoids, and to NETs with poorly differentiated histology as small cell carcinomas.

Presentation and initial evaluation

Functional NETs may produce hormones, resulting in a condition known as the carcinoid syndrome, characterized commonly by skin flushing, diarrhea or palpitations. Approximately, half of patients with NETs, from gastrointestinal or pancreatic primary tumors, have symptoms related to carcinoid syndrome, and in general the presence of these symptoms implies the presence of liver metastases, as hormones produced by the primary tumor are metabolized in the liver to non-functional by-products. Liver metastases, on the other hand, are able to secrete hormones directly into the hepatic veins and systemic circulation. Hence, hormone-related symptoms are often an indicator of metastatic disease, although primary tumors with access to systemic circulation may rarely cause similar symptoms. Pancreatic primary tumors may be non-functional or produce hormones causing other symptoms and syndromes unrelated to carcinoid syndrome. These functional PNETs are named for the primary hormone produced, such as insulinomas, gastrinomas, glucagonomas and somatostatinomas.

The appropriate evaluation for any patient with a new diagnosis of NET involves a complete history and physical examination, with attention to questions regarding symptoms possibly related to the carcinoid syndrome and family history relevant for syndromes, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia and Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Initial diagnostic tests include multiple laboratory and several imaging studies. The results of these investigations guide therapy related to symptom control, and management of primary and often metastatic tumors. Because many NETs produce hormones with or without associated symptoms, we routinely measure several polypeptides during the first evaluation of any patient with NET (Table 1), and any elevated markers are subsequently followed to aid in surveillance following therapy or during observation. Most centers routinely measure 24-h urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and serum chromogranin-A levels in the evaluation of NETs. We find it useful to measure serum pancreastatin, a post-translational split product of chromogranin-A, and we have previously demonstrated a correlation between decreased pancreastatin levels and radiological response to regional liver therapy in patients with metastatic NETs (Bloomston et al., 2007). Others have also found pancreastatin to be a useful biomarker for NETs, specifically in that elevated plasma concentrations before therapy are associated with number of liver metastases, increased periprocedural mortality after hepatic arterial embolization and overall poor outcome (Vinik et al., 2009).

Table 1.

The Ohio State University total polypeptide panel for initial evaluation of neuroendocrine tumors

| Peptide | Reference range | Elevated |

|---|---|---|

| Calcitonin | <5.0 pg/ml | Uncommon (10%) |

| Gastrin | 0–122 pg/ml | Uncommon (3–18%) |

| Gastrin-releasing peptide | <500 pg/ml | Rare (3%) |

| Neurotensin | <100 pg/ml | Uncommon (10–12%) |

| Pancreastatin | <135 pg/ml | Common (81–100%) |

| Pancreatic polypeptide | <500 pg/ml | Uncommon (13–29%) |

| Substance P | 0–240 pg/ml | Uncommon (18–19%) |

| Vasoactive intestinal peptide | 0–84 pg/ml | Rare (<5%) |

References: Calhoun et al., 2003; Varker et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2008.

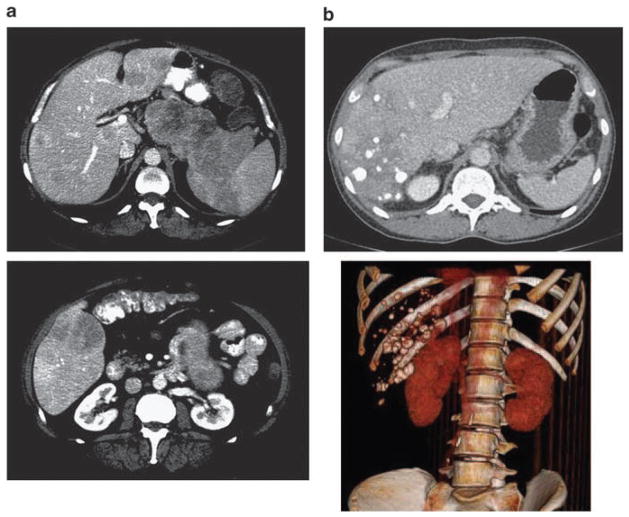

It is also important to evaluate electrolytes, liver transaminases, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, any of which may be abnormal in patients with NET, especially in those patients with a large burden of liver metastases. Cross-sectional imaging with high-quality multidetector computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (triple phase study for the abdomen and pelvis includes series without intravenous contrast, and with contrast in the arterial and portal venous phases) provides high yield for both the initial evaluation of metastatic disease and to assess response to therapies (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging is occasionally necessary to classify indeterminate findings in the liver on CT scan.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan imaging for neuroendocrine tumors. (a) Selected axial CT images of a patient with a large pancreatic primary neuroendocrine carcinoma and multiple hepatic metastases (top and bottom). (b) CT axial image after right lobar hepatic transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for liver metastases (top) with three-dimensional reconstruction and subtracted view (bottom).

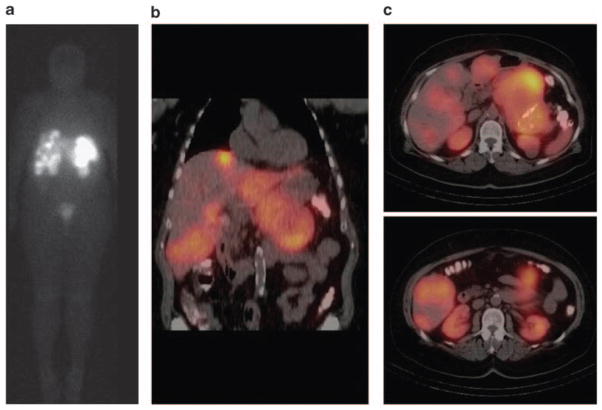

The radiolabeled somastostatin analog, octreotide, can be imaged by a nuclear medicine gamma camera and used to detect primary and metastatic NETs. This modality, termed somatostatin scintigraphy, allows for total body scanning and has high sensitivity (range 61–100% depending on tumor subtype) and positive predictive value for detection of NETs (Krenning et al., 1993; Modlin et al., 2005). Positive scintigraphy has been associated with expression of the somatostatin receptor subtype 2 and improved overall survival (Asnacios et al., 2008). The addition of single photon emission computed tomography to somatostatin scintigraphy allows for increased anatomic detail to the functional information gained with nuclear imaging (Figure 2). At our center, we use somatostatin scintigraphy in the initial evaluation of patients with metastatic NET before planned surgical resection or when otherwise clinically indicated, such as for evaluation of unexplained new symptoms, change in performance status or unusual computed tomography scan findings.

Figure 2.

Octreoscan imaging for neuroendocrine tumors. Coronal octreoscan image demonstrating radiotracer uptake in multiple liver metastases and a large pancreatic primary neuroendocrine carcinoma. (b) Coronal octreoscan fusion images with single positron emission tomography (SPECT) providing increased anatomic detail. (c) Axial octreoscan fusion images with SPECT.

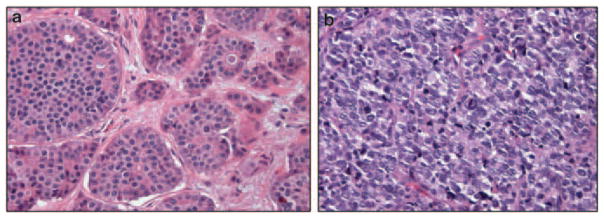

Given the variability in the biological activity of NETs with well-differentiated histology, ranging from indolent disease, with no or slow growth over many years, to aggressive malignancies, which can be fatal weeks to months after initial diagnosis, histological segregation of disease, has a role in treatment selection (Figure 3). Previous studies have demonstrated the association of poorer survival in NET patients with poor histological grade, perineural or lymphovascular invasion, mitotic index as measured by Ki-67 staining, tumor size or hormone production (Reidy et al., 2009). Both the World Health Organization and others have developed classification systems for NETs, based largely upon cell of origin and histological subtypes (Solcia et al., 2000; Rindi et al., 2006, 2007). Correct interpretation of pathological findings after biopsy is therefore critical, and our usual practice is to perform an internal review of any pathological slides obtained at other referring institutions, with a priority given to determining histological grade and Ki-67 staining.

Figure 3.

Histological subtypes of neuroendocrine tumors. (a) Microscopic section from a well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma demonstrating low mitotic rate and low-grade bland histology. (b) Microscopic section from a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma demonstrating high mitotic rate and high-grade histology similar in appearance to small cell carcinomas.

This review will discuss treatment options for patients, with primary and metastatic NETs, primarily focusing on well-differentiated carcinomas arising from pancreatic or intestinal cell origin. These tumors are described as typical carcinoids by the 2004 World Health Organization classification. The management of other malignancies, which broadly fit the classification of NET, such as cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinomas/Merkel cell carcinoma, medullary thyroid cancer, functional adrenal adenomas, pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma and small cell carcinomas will not be discussed. The bulk of the prospective trials presented in this paper will be those taken from the last 10 years, with particular attention to biologically targeted therapies.

Local and regional therapies

No review about NET management is complete without discussion of local and regional therapies for primary tumors and metastases. Surgical resection is the main-stay of therapy for localized primary tumors, although observation may be appropriate for slow-growing asymptomatic primary tumors for which surgical resection would be associated with a high risk of morbidity or mortality. Surgery is the only potentially curative treatment for early stage carcinoid or PNETs. Surgical debulking or cytoreduction of metastatic disease, usually liver or mesenteric lymph node metastases, is appropriate in selected patients for palliation of pain, bowel obstruction or carcinoid syndrome. Although surgical resection has been associated with better prolonged symptom control compared with other modalities, studies supporting this claim are subject to selection bias (Que et al., 1995; Osborne et al., 2006). There are no controlled studies to support the use of surgical debulking in asymptomatic patients with a large burden of tumor in the liver although retrospective studies demonstrate improved outcomes in these patients compared with those who do not undergo surgical resection (Hodul et al., 2008).

Liver transplantation is feasible for patients with unresectable metastatic NET metastases, although the worldwide experience is limited. A review of the French experience with transplantation for metastatic NETs was reported by Le Treut, in which 85 patients underwent liver transplant over a 16-year period (Le Treut et al., 2008). Most of the patients in the study had PNETs or carcinoid tumors. The perioperative mortality was 14% (n=12), with median survival of 56 months, and most patients dying as a result of recurrent disease. As such, transplantation is rarely used worldwide except for highly selected patients.

Transarterial embolization or chemoembolization (TACE) of liver metastases is a common therapy for NET patients. Such liver-directed therapy is effective in controlling NET growth because of disruption of tumor blood supply, derived largely from the hepatic arterial system with or without focused delivery of high-dose chemotherapy. The durability of response is quite variable, ranging from months to years, and higher response rates have been associated with aggressive management using multiple therapeutic modalities such as serial TACE treatments with hepatic resection (Touzios et al., 2005). The median progression-free survival after TACE for metastatic NETs at our center was 10 months, with overall survival 33 months (Bloomston et al., 2007).

Possible complications of TACE include carcinoid crisis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, gastritis or enteritis, liver abscess, biliary complications and liver or renal failure; mortality ranges from 1 to 5% (Kiely et al., 2006). More common side-effects are pain, fever, nausea and fatigue, which can be fairly severe and last for 6–8 weeks (Bloomston et al., 2007; Varker et al., 2007). We have found that a staged approach in patients with bilobar liver metastases treating one liver lobe per TACE session is better tolerated than whole-liver TACE during a single session. Treatment with TACE at out center involves a multidisciplinary team approach and a specific protocol for supportive care, including periprocedural intravenous octreotide, patient counseling, education and intense post-procedure surveillance.

Another loco-regional therapy for metastatic NETs in the liver, similar to TACE in approach, is selective internal radiation therapy with Yttrium-90. Yttrium-90 is a radioactive beta-emitter with a half-life of 64 h, which is bound to microspheres for use in selective internal radiation therapy and delivered through the hepatic artery. One of the largest experiences reported combines the data from 10 centers and includes 148 patients who underwent treatment with Yttrium- 90-selective internal radiation therapy for hepatic NET metastases (Kennedy et al., 2008). A partial radiographic response was noted in 60% of patients with a median survival of 70 months after the initial procedure. Only one-third of patients in the study experienced any Common Terminology Criteria grade 3 or 4 toxicities, and there were no deaths reported related to Yttrium-90-selective internal radiation therapy.

Isolated hepatic perfusion with high-dose melphalan or tumor necrosis factor have been used by investigators at the National Cancer Institute with advanced progressive hepatic metastatic NETs, with a radiological response rate of 50% (Grover et al., 2004). Approximately, three-fourths of patients experienced grade III and IV toxicities, most notably a transient elevation in liver transaminases, which resolved without intervention in 62% and elevated creatinine in 31% of patients. Other toxicities occurring in more than 10% of patients included thrombocytopenia (15%) and pleural effusion (15%). There was one death in the study. A clinical trial using percutaneous hepatic perfusion of liver metastases from multiple primary tumors, including NETs, is ongoing at the National Cancer Institute.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

In general, well-differentiated NETs, including most carcinoid tumors and PNETs are resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Historically, fluoruracil (5-FU) and streptozotocin-based regimens have been used for metastatic NETs, although controversy exists over reported response rates and clinical efficacy (Reidy et al., 2009). Combination therapy with 5-FU and streptozotocin was compared with 5-FU and doxorubicin (FUDOX) in a phase II/III study by Sun and colleagues. Response rates were similar in both groups (16%) but the 5-FU and streptozotocin regimen was associated with longer median overall survival (24.3 months) than the 5-FU and doxorubicin regimen (15.7 months); life-threatening toxicity occurred in 11% of patients with a 1.9% mortality rate (Sun et al., 2005). More encouraging results have been obtained over the past decade using chemotherapy combinations with improved activity for NETs. Some regimens that have demonstrated radiological response rates around 20–30% include dose intense 5-FU, dacarbazine and epirubicin (Bajetta et al., 2002) or cisplatin and etopside (Fjällskog et al., 2001). Pavel and colleagues treated 10 patients with streptozotocin and doxorubicin after progression on other therapies (interferon alpha (IFN-α) or somatostatin analogs) and reported a 33% (n=3) radiological response rate (Pavel et al., 2005).

A provocative study by Kulke and coauthors demonstrates an association with O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) and treatment response to temozolamide (Kulke et al., 2009). In their study, immunohistochemistry was used to identify the presence or absence of MGMT in NET tissue, and MGMT expression was observed in 19 of 37 (51%) PNETs and in none of the 60 carcinoid tumors. Interestingly, a deficiency of MGMT in PNETs was associated with sensitivity to temozolamide. In 21 patients with tumor tissue evaluated, four of five patients with MGMT-deficient tumors (all PNETs) responded to treatment with temozolamide-based therapy, whereas none of the 16 patients with intact MGMT responded (P=0.001).

Prospective trials evaluating other treatment regimens for advanced NETs have shown low response rates (<10%), including high-dose paclitaxel (Ansell et al., 2001), high-dose infusional 5-FU and hydroxy-urea (Kaubisch et al., 2004), gemcitabine (Kulke et al., 2004a), docetaxel (Kulke et al., 2004b) and irinotecan with cisplatin (Kulke et al., 2006c). Because of low response rates and significant toxicities of cytotoxic chemotherapies, in general for NETs, we favor local and regional therapies when possible for disease control at our institution and strongly encourage eligible patients to enroll in ongoing clinical trials.

Targeted therapies for neuroendocrine carcinomas

Increasing understanding of tumor biology at the molecular level has led to the advent of molecular biological agents for use in cancer therapy, allowing targeted treatment of solid tumors based on information about alterations in cellular pathways and the cell cycle genomics, proteomics and epigenetics. Many studies have been performed over the past decade describing the use of targeted-biological therapy for various cancers, including NETs. Several studies, most of them phase II clinical trials, have been published examining the activity of biologically targeted agents in NETs, and some have shown encouraging results in terms of antitumor activity with favorable rates of partial responses or stable disease (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of selected clinical trials for unresectable or advanced NETs

| Drug tested | Key targets |

N=Total patients N=carcinoid/PNET |

Octreotide or LAR | PR carcinoid PNET | SD carcinoid PNET | PD carcinoid PNET | PFS (median) carcinoid PNET | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octreotide LAR | Somatostatin receptor | N=42 LAR N=43 placebo |

vs Placebo | N=1/85 | 38% LAR 5% placebo | 62% LAR 95% placebo | 14.3 months (LAR) vs 6 months | Rinke et al., 2009 |

| Octreotide with/without IFN-α | Somatostatin receptor IFN-αR | N=68 carcinoid only | All | 0% | 82% (27/33) combination 46% (16/35) Octreotide alone |

18% (6/33) combination 54% (19/35) Octreotide alone |

NA | Kolby et al., 2003 |

| IFN-γ | IFN-γR | N=48 | Not allowed | 6% (N=3) | 58% (N=28) | 31% (N=15) | 5.5 months | Stuart et al., 2004 |

| Bortezomib | 26S Proteasome | N=16 N=12/4 | Allowed N=6 | 0% | 69% (N=11) | 31% (N=5) | NA | Shah et al., 2006 |

| Thalidomide | TNF-α | N=18 N=9/5 | Allowed | 0% | 69% (N=11) | 31% (N=5) | 7 months | Varker et al., 2008 |

| Imatinib | Abl; c-kit; PDGFR-α/β | N=27 carcinoid only | Allowed N=17 | 3.7% (N=1) | 83% (N=17) | 33% (N=9) | 5.9 months | Yao et al., 2007 |

| Endostatin | Vascular endothelium | N=42 N=20/22 | Allowed | 0% | 80% (N=32) | 20% (N=8) | 7.6 months, 5.8 months | Kulke et al., 2006a, b, c |

| Temozolamide and thalidomide | Cytotoxic; TNF-α | N=26 N=15/11 | Allowed N=11 | 7% (N=1) 45% (N=5) |

68% (N=19) | 7% (N=2) | Not reached | Kulke et al., 2006a, b, c |

| Temsirolimus | MTOR |

N=36 N=21/15 |

Allowed N=9 | 4.8% (N=1) 6.7% (N=1) |

57% (N=12) 60% (N=9) |

29% (N=6) 27% (N=4) |

6 months, 10.6 months | Duran et al., 2006 |

| Everolimus | MTOR |

N=60 N=30/30 |

All | 17% (N=5) 27% (N=8) |

80% (N=24) 70% (N=18) |

3% (N=1) 13% (N=4) |

15.7 months, 12.5 months | Yao et al., 2008 |

| Sunitinib | VEGFR 1–3 PDGFR-α/β |

N=107 N=41/66 |

Allowed (N=22/18) | 2.4% (N=1) 17% (N=11) |

83% (N=34) 68% (N=45) |

2.4% (N=1) 7.6% (N=5) |

10.2 months, 7.7 months | Kulke et al., 2008 |

| Bevacizumab and IFN-α | VEGF; IFN-αR | N=44 carcinoid only | All | 18% (Bevacizumab) 0% (INF-α) | 77% (Bevacizumab) 68% (INF-α) | 5% | 15.7 months | Yao et al., 2008 |

Abbreviations: Abl, Abelson oncogene; IFN, interferon; LAR, long-acting repeatable; MTOR, mammalian target of Rapamycin; NA, not available; NETs, neuroendocrine tumors; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PFR, progression-free rate; PNET, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Somatostatin

Somatostatin is an endogenous peptide secreted by neuroendocrine cells with general inhibitory actions on gastrointestinal cells. Somatostatin analogs such as the drug octreotide (Sandostatin, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland) have been developed, which bind to somatostatin receptors, and these compounds are widely used in the treatment of NETs. One goal for use of somatostatin analogs is amelioration of symptoms related to the carcinoid syndrome. Diarrhea and flushing are the most common patient complaints, and the use of octreotide or lanreotide has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the frequency of carcinoid syndrome symptoms (Ruszniewski et al., 2004; Berkovi et al., 2007).

Somatostatin analogs also inhibit the growth of gastrointestinal cells and may have a tumoristatic effect on NETs. Although many studies have been published regarding the use of octreotide and lanreotide for this purpose, attribution of the study drug to stabilization of NET is difficult because of the slow-growing nature of such cancers. The most exciting and encouraging data comes from a recently published randomized prospective phase III trial comparing use of month long-acting octreotide versus placebo in treatment-naïve patients with well-differentiated metastatic midgut primary NETs (Rinke et al., 2009). An interim analysis in the 85 patients enrolled at that time, revealed a significant benefit in the treatment arm with a median time to progression of 14.3 months compared with 6 months in the placebo group. Nearly twice as many patients in the treatment arm compared with the placebo arm had stable disease at 6 months.

An intriguing use of somatostatin analogs for treatment of NETs combines the ability of the compound to specifically bind somatostatin receptors with internalization of cytotoxic radioactive isotopes bound to the ligand. This therapy is not currently approved for use in the United States, but is available in several European countries. The published studies to date include both heterogeneous patient populations and treatment approaches and therefore the results vary (Table 3). Nevertheless, in properly selected patients this may be a valuable treatment strategy, and furthermore represents an innovative approach in targeting radiation therapy based on the molecular characteristics of NETs.

Table 3.

Selected studies evaluating radiolabeled somatostatin analogs for treatment of NETs

| Study | N | Radiolabeled somatostatin analog | Response rates (PR+CR) | Symptom relief or reduction | Median overall survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bushnell, 2010 USA | 90 | 90-Y-edotreotide | 4% | >50% | 26.9 months |

| Delpassand, 2008 USA | 18 | In-111 pentetreotide | 11% | NA | 13.3 months |

| Kwekkeboom 2008 Netherlands | 310 | Lu-177-octreotate | 30% | NA | 46 months |

| Forrer 2006 Switzerland | 116 | 90-Y-DOTATOC | 27% | 83% | NA |

| Anthony 2002 USA | 26 | In-111 pentetreotide | 8% | 62% | 18 months |

Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; In-111, indium 111; Lu-177, leutium-177; NA, not available; PR, partial remission; 90-Y, 90-yttrium.

Interferon alpha

Like somatostatin and its analogs, IFN-α has an antiproliferative effect on NETs. In one of the first prospective studies comparing these treatment modalities, the combination of IFN and the somatostatin analog lanreotide was given to 80 patients with NETs and progression of disease. Combination therapy or the use of either agent alone was comparable to stable disease in 18–26% of patients, but with further progression of disease in half of the patients in each arm and only 4 out of 80 patients showing partial tumor response in the entire study (Faiss et al., 2003). Another multicenter prospective trial compared treatment with octreotide alone or in combination with IFN-α in 68 patients, with more encouraging results (Kolby et al., 2003). With a median follow-up of 24 months, combination therapy was associated with an improved progression-free survival (18% progression) compared with those treated with octreotide alone (54% progression, P=0.008); there was also a trend towards improved overall survival with combination therapy; mean 5-year survival was 56.8% in the IFN group compared with 36.6% (P=0.132) in the placebo group.

Treatment with IFN-α is associated with significant side-effects, such as fatigue or flu-like symptoms, and a high rate of non-compliance with therapy; the use of pegylated IFN has been associated with improved patient tolerability (Pavel et al., 2006). Given the high rate of side-effects and modest antitumor activity, use of IFN-α for treatment of NETs is less common than other modalities or clinical trials. Of note, treatment with IFN-γ was studied in 51 patients with metastatic carcinoid tumors by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, and the radiological response rate was 6% (Stuart et al., 2004).

Other biological therapies

Imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. In an elegant study by Yao and colleagues, imatinib was also demonstrated to have a dose-dependent cytotoxic in vitro effect for bronchial and PNET cell lines, although clinical activity was modest with only one partial tumor response in 27 evaluable patients (Yao et al., 2007). An interesting finding in this study was the association of biochemical response to imatinib therapy (measurable decrease or normalization of serum markers chromogranin A or pancreatic polypeptide), with improved progression-free survival. Although tumor response to initial therapy and the later development of resistance to therapy are dependent on molecular subtypes in patients treated with imatinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumors, small-cell lung carcinomas are resistant to imatinib even when c-kit is positive (Krug et al., 2005; Agaram et al., 2007).

Thalidomide is an immunomodulatory drug with antiangiogenic properties. A phase II trial in which 18 patients with NETs were treated with daily oral thalidomide at 200 mg escalated to 400 mg did not result in any partial tumor responses (Varker et al., 2008). However, the addition of oral temozolamide, an oral alkylating agent, at a dose of 150 mg/m2 for 7 days every other week to treatment with oral thalidomide at doses ranging from 50 to 400 mg daily, resulted in a radiological response rate of 25% and a biochemical response rate of 40% in a study of 29 patients with NETs (Kulke et al., 2006b). The combination regimen of temozolamide and thalidomide was associated with a high rate of toxicity in the study, and 16 (55%) patients discontinued treatment because of toxicity at a median time of 8.4 months; common toxicities included neuropathy (38%), thrombocytopenia (14%) and infection (14%).

A clinical trial examining the effect of the histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide was terminated because of unacceptable cardiac toxicities (Shah et al., 2006). Endostatin, a recombinant human protein fragment of collagen XVIII, with antiangiogenic behavior, did not demonstrate any antitumor activity in patients with NETs in one phase II trial (Kulke et al., 2006a). The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib was studied in 16 patients with NETs, and although the surrogate biological end point measured in the study was achieved, there were no partial tumor responses (Shah et al., 2004). Despite these somewhat discouraging results, in recent years several biological agents described below have shown significant promise.

Metastatic NETs in the liver predominantly derive their blood supply from hepatic arteries as described in the section on loco-regional therapies. Furthermore, these tumors are known to secrete vascular endothelial growth factor and to express the receptor of vascular endothelial growth factor. Therefore, biologically targeted therapies affecting this pathway have been studied in NETs. Bevacizumab is an antibody that binds vascular endothelial growth factor-A, preventing interaction with its receptor. In a study performed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, bevacizumab achieved a partial response in 4 of 22 patients (18%) and stable disease in all of the remaining patients except one over an 18-week period (Yao et al., 2008). Of note, patients may have had stable disease before enrollment, making it difficult to determine whether patients with stable disease derived any benefit from therapy. On the basis of these preliminary results, a multicenter phase III trial, comparing octreotide LAR in combination with either IFN-α or bevacuzimab, is being conducted by the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG).

Sunitinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with activity against vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, was given to 107 patients with advanced NETs in a phase II study (Kulke et al., 2008). Response rates were higher in PNETs (16.7%) compared with carcinoid tumors (2.4%). Preliminary results from a randomized phase III study comparing sunitinib versus placebo in patients with advanced PNETs were recently presented in abstract form at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s 2010 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium. This study was stopped early because of an interim analysis, demonstrating improved median progression-free survival in the sunitinib arm (11.4 months) compared with the placebo arm (5.5 months, P=0.0001).

A phase-II study examining the role of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor temsirolimus in 37 patients, with advanced NETs, demonstrated an overall response rate of 5.6% (Duran et al., 2006). Of note, patients enrolled in this clinical trial had progressive metastatic disease documented within 6 months of enrollment. Another study examining treatment, with the combination of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus and long-acting octreotide, in patients with metastatic PNETs or carcinoid tumors reported a radiological response rate of 22% (n=13 of 60 patients). Median progression-free survival in the study was 60 weeks (Yao et al., 2008). A randomized phase III trial comparing everolimus to placebo in patients with metastatic PNETs and carcinoid tumors has recently been completed and results are eagerly anticipated.

Conclusion

Neuroendocrine carcinomas are rare tumors with a wide range of biological activity and prognosis. Despite low response rates to conventional chemotherapies, recent advances in loco-regional approaches and targeted radioactive and biological therapies provide hope that control of tumor growth is possible in those with progression or a life-threatening burden of disease. The use of a personalized approach to treatment with particular attention to molecular classification of tumors will be critical in tailoring future therapeutic options to find the most potentially effective treatment for each patient.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agaram NP, Besmer P, Wong GC, Guo T, Socci ND, Maki RG, et al. Pathologic and molecular heterogeneity in imatinib-stable or imatinib-responsive gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:170–181. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell SM, Pitot HC, Burch PA, Kvols LK, Mahoney MR, Rubin J, et al. A Phase II study of high-dose paclitaxel in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2001;91:1543–1548. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010415)91:8<1543::aid-cncr1163>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony LB, Woltering EA, Espenan GD, Cronin MD, Maloney TJ, McCarthy KE. Indium-111-pentetreotide prolongs survival in gastroenteropancreatic malignancies. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:123–132. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2002.31769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnacios A, Courbon F, Rochaix P, Bauvin E, Cances-Lauwers V, Susini C, et al. Indium-111-pentetreotide scintigraphy and somatostatin receptor subtype 2 expression: new prognostic factors for malignant well-differentiated endocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:963–970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajetta E, Ferrari L, Procopio G, Catena L, Ferrario E, Martinetti A, et al. Efficacy of a chemotherapy combination for the treatment of metastatic neuroendocrine tumours. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:614–621. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berković MC, Altabas V, Herman D, Hrabar D, Goldoni V, Vizner B, et al. A single-centre experience with octreotide in the treatment of different hypersecretory syndromes in patients with functional gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Coll Antropol. 2007;31:531–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomston M, Al-Saif O, Klemanski D, Pinzone JJ, Martin EW, Palmer B, et al. Hepatic artery chemoembolization in 122 patients with metastatic carcinoid tumor: lessons learned. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell DL, Jr, O’Dorisio TM, O’Dorisio MS, Menda Y, Hicks RJ, Van Custem E, et al. 90Y-edotreotide for metastatic carcinoid refractory to octreotide. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1652–1659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun K, Toth-Fejel S, Cheek J, Pommier R. Serum peptide profiles in patients with carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg. 2003;186:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpassand ES, Sims-Mourtada J, Saso H, Azhdarinia A, Ashoori F, Torabi F, et al. Safety and efficacy of radionuclide therapy with high-activity In-111 pentetreotide in patients with progressive neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2008;23:292–300. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2007.0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran I, Kortmansky J, Singh D, Hirte H, Kocha W, Goss G, et al. A phase II clinical and pharmacodynamic study of temsirolimus in advanced neuroendocrine carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1148–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faiss S, Pape UF, Böhmig M, Dörffel Y, Mansmann U, Golder W, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter trial on the antiproliferative effect of lanreotide, interferon alfa, and their combination for therapy of metastatic neuroendocrine gastroentero-pancreatic tumors—the International Lanreotide and Interferon Alfa Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2689–2696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjällskog ML, Granberg DP, Welin SL, Eriksson C, Oberg KE, Janson ET, et al. Treatment with cisplatin and etoposide in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2001;92:1101–1107. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1101::aid-cncr1426>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrer F, Waldherr C, Maecke HR, Mueller-Brand J. Targeted radionuclide therapy with 90Y-DOTATOC in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:703–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover AC, Libutti SK, Pingpank JF, Helsabeck C, Beresnev T, Alexander HR, Jr, et al. Isolated hepatic perfusion for the treatment of patients with advanced liver metastases from pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Surgery. 2004;136:1176–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodul PJ, Strosberg JR, Kvols LK. Aggressive surgical resection in the management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: when is it indicated? Cancer Control. 2008;15:314–321. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaubisch A, Kaleya R, Haynes H, Rozenblit A, Wadler S. Phase II clinical trial of parenteral hydroxyurea in combination with fluorouracil, interferon and filgrastim in the treatment of advanced pancreatic, gastric and neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:337–340. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0727-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AS, Dezarn WA, McNeillie P, Coldwell D, Nutting C, Carter D, et al. Radioembolization for unresectable neuroendocrine hepatic metastases using resin 90Y-microspheres: early results in 148 patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:271–279. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31815e4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely JM, Rilling WS, Touzios JG, Hieb RA, Franco J, Saeian K, et al. Chemoembolization in patients at high risk: results and complications. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:47–53. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000195074.43474.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolby L, Persson G, Franzen S, Ahren B. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of interferon alpha on survival in patients with disseminated midgut carcinoid tumours. Br J Surg. 2003;90:687–693. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenning EP, Kwekkeboom DJ, Bakker WH, Breeman WA, Kooij PP, Oei HY, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with [111In-DTPA-D-Phe1]- and [123I-Tyr3]-octreotide: the Rotterdam experience with more than 1000 patients. Eur J Nucl Med. 1993;20:716–731. doi: 10.1007/BF00181765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug LM, Crapanzano JP, Azzoli CG, Miller VA, Rizvi N, Gomez J, et al. Imatinib mesylate lacks activity in small cell lung carcinoma expressing c-kit protein: a phase II clinical trial. Cancer. 2005;103:2128–2131. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Bergsland EK, Ryan DP, Enzinger PC, Lynch TJ, Zhu AX, et al. Phase II study of recombinant human endostatin in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006a;24:3555–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Hornick JL, Frauenhoffer C, Hooshmand S, Ryan DP, Enzinger PC, et al. O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase deficiency and response to temozolomide-based therapy in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:338–345. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Kim H, Clark JW, Enzinger PC, Lynch TJ, Morgan JA, et al. A Phase II trial of gemcitabine for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2004a;101:934–939. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Kim H, Stuart K, Clark JW, Ryan DP, Vincitore M, et al. A phase II study of docetaxel in patients with metastatic carcinoid tumors. Cancer Invest. 2004b;22:353–359. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200029058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Lenz HJ, Meropol NJ, Posey J, Ryan DP, Picus J, et al. Activity of sunitinib in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3403–3410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Stuart K, Enzinger PC, Ryan DP, Clark JW, Muzikansky A, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006b;24:401–406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Wu B, Ryan DP, Enzinger PC, Zhu AX, Clark JW, et al. A phase II trial of irinotecan and cisplatin in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Dig Dis Sci. 2006c;51:1033–1038. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-8001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, Kam BL, van Eijck CH, van Essen M, Kooij PP, et al. Treatment with the radiolabeled somatostatin analog [177 Lu-DOTA 0,Tyr3]octreotate: toxicity, efficacy, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2124–2130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Treut YP, Grégoire E, Belghiti J, Boillot O, Soubrane O, Mantion G, et al. Predictors of long-term survival after liver transplantation for metastatic endocrine tumors: an 85-case French multicentric report. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1205–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717–1751. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne DA, Zervos EE, Strosberg J, Boe BA, Malafa M, Rosemurgy AS, et al. Improved outcome with cytoreduction versus embolization for symptomatic hepatic metastases of carcinoid and neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:572–581. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel ME, Baum U, Hahn EG, Hensen J. Doxorubicin and streptozotocin after failed biotherapy of neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:179–185. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:35:3:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel ME, Baum U, Hahn EG, Schuppan D, Lohmann T. Efficacy and tolerability of pegylated IFN-alpha in patients with neuroendocrine gastroenteropancreatic carcinomas. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:8–13. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que FG, Nagorney DM, Batts KP, Linz LJ, Kvols LK. Hepatic resection for metastatic neuroendocrine carcinomas. Am J Surg. 1995;169:36–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80107-x. discussion 42–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DL, Tang LH, Saltz LB. Treatment of advanced disease in patients with well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2009;6:143–152. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindi G, Klöppel G, Alhman H, Caplin M, Couvelard A, de Herder WW, et al. TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindi G, Klöppel G, Couvelard A, Komminoth P, Körner M, Lopes JM, et al. TNM staging of midgut and hindgut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:757–762. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinke A, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, Klose KJ, Barth P, Wied M, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4656–4663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruszniewski P, Ish-Shalom S, Wymenga M, O’Toole D, Arnold R, Tomassetti P, et al. Rapid and sustained relief from the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome: results from an open 6-month study of the 28-day prolonged-release formulation of lanreotide. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80:244–251. doi: 10.1159/000082875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MH, Young D, Kindler HL, Webb I, Kleiber B, Wright J, et al. Phase II study of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (PS-341) in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6111–6118. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MH, Binkley P, Chan K, Xiao J, Arbogast D, Collamore M, et al. Cardiotoxicity of histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3997–4003. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solcia E, Kloppel G, Sobin L. WHO International Histologic Classification of TUMORS. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart K, Levy DE, Anderson T, Axiotis CA, Dutcher JP, Eisenberg A, et al. Phase II study of interferon gamma in malignant carcinoid tumors (E9292): a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Invest New Drugs. 2004;22:75–81. doi: 10.1023/b:drug.0000006177.46798.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Lipsitz S, Catalano P, Mailliard JA, Haller DG. Phase II/III study of doxorubicin with fluorouracil compared with streptozocin with fluorouracil or dacarbazine in the treatment of advanced carcinoid tumors: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1281. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4897–4904. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touzios JG, Kiely JM, Pitt SC, Rilling WS, Quebbeman EJ, Wilson SD, et al. Neuroendocrine hepatic metastases: does aggressive management improve survival? Ann Surg. 2005;241:776–783. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161981.58631.ab. discussion 783–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varker KA, Martin EW, Klemanski D, Palmer B, Shah MH, Bloomston M, et al. Repeat transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for progressive hepatic carcinoid metastases provides results similar to first TACE. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1680–1685. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varker KA, Campbell J, Shah MH. Phase II study of thalidomide in patients with metastatic carcinoid and islet cell tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:661–668. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinik AI, Silva MP, Woltering EA, Go VL, Warner R, Caplin M, et al. Biochemical testing for neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2009;38:876–889. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bc0e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Zhang JX, Rashid A, Yeung SC, Szklaruk J, Hess K, et al. Clinical and in vitro studies of imatinib in advanced carcinoid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:234–240. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Phan AT, Chang DZ, Wolff RA, Hess K, Gupta S, et al. Efficacy of RAD001 (everolimus) and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4311–4318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Phan A, Hoff PM, Chen HX, Charnsangavej C, Yeung SC, et al. Targeting vascular endothelial growth factor in advanced carcinoid tumor: a random assignment phase II study of depot octreotide with bevacizumab and pegylated interferon alpha-2b. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1316–1323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]