Abstract

Background

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, and oxidative stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cachexia (muscle wasting) and the hallmark symptom, exercise intolerance. We have previously shown that a nitric oxide (NO)-dependent antioxidant defense renders oxidative skeletal muscle resistant to catabolic wasting. Here, we aimed to identify and determine the functional role of the NO-inducible antioxidant enzyme(s) in protection against cardiac cachexia and exercise intolerance in CHF.

Methods and Results

We demonstrated that systemic administration of endogenous nitric oxide donor S-Nitrosoglutathione in mice blocked the reduction of extracellular superoxide dismutase (EcSOD) protein expression, the induction of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 mRNA expression and muscle atrophy induced by glucocorticoid. We further showed that endogenous EcSOD, expressed primarily by type IId/x and IIa myofibers and enriched at endothelial cells, is induced by exercise training. Muscle-specific overexpression of EcSOD by somatic gene transfer or transgenesis [muscle creatine kinase (MCK)-EcSOD] in mice significantly attenuated muscle atrophy. Importantly, when crossbred into a mouse genetic model of CHF [α-myosin heavy chain (MHC)-calsequestrin] MCK-EcSOD transgenic mice had significant attenuation of cachexia with preserved whole body muscle strength and endurance capacity in the absence of reduced heart failure. Enhanced EcSOD expression significantly ameliorated CHF-induced oxidative stress, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 mRNA expression, loss of mitochondria and vascular rarefaction in skeletal muscle.

Conclusions

EcSOD plays an important antioxidant defense function in skeletal muscle against cardiac cachexia and exercise intolerance in CHF.

Keywords: oxidative stress, catabolic muscle wasting, exercise intolerance, mitochondrial dysfunction, vascular rarefaction

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in industrialized countries. Cachexia, characterized by severe loss of muscle mass and exercise intolerance, manifested as fatigue and dyspnea during minimal physical activities, are important predictors of mortality in CHF. The progressive decline of exercise capacity results from multiple skeletal muscle abnormalities, including atrophy, impaired excitation-contraction coupling, mitochondrial dysfunction and vascular rarefaction1-3. Oxidative stress due to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and/or reduced antioxidant defenses has emerged as a central player in cardiac cachexia, and is mechanistically linked to intracellular signaling, contractile protein function and degradation3-6. Although animal studies have shown effectiveness of antioxidant supplements in treatment, clinical trials have limited successes7, 8, possibly due to lack of specificity to the target cells and subcellular environment leading to either poor efficacy or impairment of physiological signaling. It is critical to identify a viable approach to augment the endogenous antioxidant defense system to cope with this complicated clinical syndrome.

Our body has very sophisticated, functional antioxidant defense systems for maintaining a delicate redox homeostasis. The first line of antioxidant defense is comprised of superoxide dismutases (SODs), which scavenge superoxide (O2−) to produce the less reactive hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Skeletal muscle expresses all three isoforms of SOD: the cytosolic copper/zinc-containing SOD (CuZnSOD or SOD1), the mitochondrial manganese-containing SOD (MnSOD or SOD2) and the extracellular SOD (EcSOD or SOD3). EcSOD is a glycoprotein that is secreted and has high affinity for sulfated polysaccharides, such as heparin and heparin sulfate, through its haprin-binding domain on the C-terminus. EcSOD may also be internalized by the cells that it binds through endocytosis9. Therefore, EcSOD may exert antioxidant function intracellularly and extracellularly in producing cells and target cells.

Expression of this antioxidant enzyme appears to be prone to suppression by pathological conditions, potentially underlying the etiology of the diseases. For example, reduced EcSOD expression has been reported in many chronic diseases, including CHF10, 11. In terms of functionality, genetic deletion of the EcSOD gene exacerbates12-14 whereas transgenic overexpression attenuates the pathologies in mouse models of chronic diseases14, 15. These findings have clearly established the functional importance of EcSOD in protection against diseases caused by oxidative stress; however, its importance of skeletal muscle mass and function is unknown.

We have recently identified a nitric oxide (NO)-dependent antioxidant defense mechanism that underlies the resistance of oxidative muscles to catabolic wasting3, 16, 17. To ascertain the protective function of NO and to identify the antioxidant gene(s) that plays a major role in this protection, we first administer systemically an endogenous NO donor, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), in a mouse model of catabolic muscle wasting induced by glucocorticoid, a hormone that is elevated in CHF and involved in muscle catabolism18. Our findings underscore the importance of NO-mediated induction of EcSOD expression in protection against catabolic muscle wasting. We then employed two independent genetic approaches and showed that enhanced EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle ameliorates cardiac cachexia and exercise intolerance along with blunted oxidative stress, atrophy gene expression, mitochondrial loss and microvascular abnormalities in a mouse model of CHF. We have, therefore, provided convincing evidence to support the effectiveness of enhancing EcSOD expression and antioxidant activity in protecting skeletal muscle structural and functional integrity under the condition of CHF.

Methods

Animals

Wild type mice (male, 8 weeks old, C57BL/6J) were obtained commercially (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor) and housed in temperature-controlled (22 °C) quarters with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and free access to water and normal chow (Harlan). A muscle-specific EcSOD transgenic mouse line was generated at the University of Virginia Gene Targeting and Transgenic Facility. Briefly, RT-PCR was performed using mouse skeletal muscle RNA with forward primer 5’-TGGATCCACCATGTTGGCCTTCTTGTTC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-AGGTACCAGTGGTCTTGCACTCGCTCTC-3’ to obtain EcSOD cDNA (NM_011435). A Bam H1-Kpn I fragment (762 bp) of the coding region was then fused to a FLAG sequence followed by a stop codon in pTarget (Promega, Madison) to create pEcSOD. A 1.3-kb Hind III-Eco RI fragment of FLAG-tagged EcSOD was then inserted into pMCKhGHpolyA between a 4.8-kb mouse muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter and the human growth hormone polyadenylation site19. A linear Not I-Xho I fragment (6.7 kb) was isolated and used for pro-nuclear injection to generate transgenic mice (C57BL/6.SJL F1 background). We backcrossed the transgene onto pure C57BL/6J background (≥7 generations). To determine if enhanced EcSOD expression prevents CHF-induced muscle atrophy, MCK-EcSOD mice were crossbred with α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC)-calsequestrin mice (CSQ; DBA background)20 to generate double transgenic MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (DTG). The wild type (WT) littermates or littermates with only MCK-EcSOD allele (TG) were used as controls. Therefore, the mice used were of the same genetic background. To prevent negative impact of heart failure on embryonic development, the α-MHC-CSQ breeder mice were treated with β-blocker metoprolol in drinking water before and during breeding6, and the β-blocker was removed at birth such that none of the mice used in the studies received β-blocker after birth. Voluntary wheel running protocol is as described21. All animal protocols were approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Genotyping--PCR of tail DNA was performed using MCK transgenic forward primer, 5’-GAC TGA GGG CAG GCT GTA AC-3’; EcSOD intron forward primer, 5’-GGG AGG TGG GAA GAG TTA GG-3’; and EcSOD coding reverse primer, 5’-CAC CTC CAT CGG GTT GTA GT-3’. Exogenous EcSOD expression in adult skeletal muscle was confirmed by immunoblot as described6.

Dexamethasone and GSNO injections

Mice received daily injection of dexamethasone (25 mg/kg, i.p.) (Sigma, St. Louis) or normal saline with/without GSNO (2 mg/kg) twice a day for 7 days22. At 12 and 24 hrs after the last injection of GSNO and dexamethasone, respectively, soleus, plantaris, tibialis anterior, gastrocnemius, extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and white vastus lateralis muscles were harvested and processed for further analyses.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and real-time PCR

These analyses were performed for MAFbx/Atrogin-1, MuRF1 and Gapdh mRNAs in plantaris muscles as described23. Real-time PCR was performed using primers for MAFbox/Atrogin 1 and 18S rRNA from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Immunoblot analysis—Immunoblot analysis was performed as described6 with the following primary antibodies: CuZnSOD (Abcam), MnSOD (Abcam), EcSOD (R&D, Minneapolis), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC- 1α) (Chemicon/Millipore), cytochrome oxidase IV (COX IV) (Invitrogen), cytochrome C (Cyt C) (Cell Signaling, Danvers), malondialdehyde (MDA) (Academy Biomedical Company, Inc., Houston) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (ab48506, Abcam). Hybridoma for antibodies against MHC I (BA-F8), MHC IIa (SC-71) and MHC IIb (BF-F3) were purchased from German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures. All the bands for analysis have been validated previously3, 6, 24. OxyBlot Protein Oxidative Detection Kit (Millipore) was used for immunblot detection of carbonylated proteins. Immunoblots were analyzed by Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, NE) and quantified by Scion Image software.

Immunohistochemistry

Fresh frozen muscle sections (5 μm) were stained with rabbit anti-EcSOD (Sigma), and images acquisition and analysis of capillary density were performed as described3.

Somatic gene transfer and measurement of myofiber size

We performed electric pulse-mediated gene transfer by injecting DNA (15 μg of pGFP3 + 50 μg of pEcSOD or pCI-neo) in tibialis anterior muscles as described24. Confocal microscopy (Fluoview 1000; Olympus) was performed to measure GFP-positive fibers fiber size (>100 fibers for each mouse) using Image J6.

Treadmill running test

The test was performed as described3. Blood lactate level was measured before, at 40 min and immediately after the test by Lactate Scout (SensLab, Leipzig)

Whole body tension test (WBT)

WBT was performed according to an established method25 in a custom-designed device. Ten trials were performed with 10-sec intervals for each mouse, and the mean value of the five peak readings was used for statistical analysis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI was used to assess cardiac function as described26.

Electrocardiography

Electrocardiography was performed on conscious mice using the ECGenie (Mouse Specifics, Boston). Mice were placed on the platform for 10 min to acclimate. Data with continuous recordings of over 40 heart beats were used for analyses by using eMOUSE, a physiologic waveform analysis platform (Mouse Specifics, Boston).

Whole mount immunofluorescence

Flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles were immunolabeled for smooth muscle α-actin (IA4-Cy3, Sigma) and isolectin (IB4-Alexa647 or Alexa488, Invitrogen) as described27.

Statistics

The results are presented as mean ± SE with each of the individual data points plotted. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed by the Wilcoxon rank sum test. A two-way ANOVA was used for comparisons across groups, and when appropriate a post-hoc test was used for detection of differences. When the data failed to meet the normality assumption, logarithmic transformation (base 10) was used prior to ANOVA. When the data failed to meet the equal variance assumption, a non-parametric test (Kruskal-Wallis) was used, and when appropriate, the Dunn's post-hoc analysis to detect difference across specific means. A p-value <0.05 was required to report significance.

Results

Systemic administration of GSNO induces EcSOD expression and prevents dexamethasone-induced muscle wasting

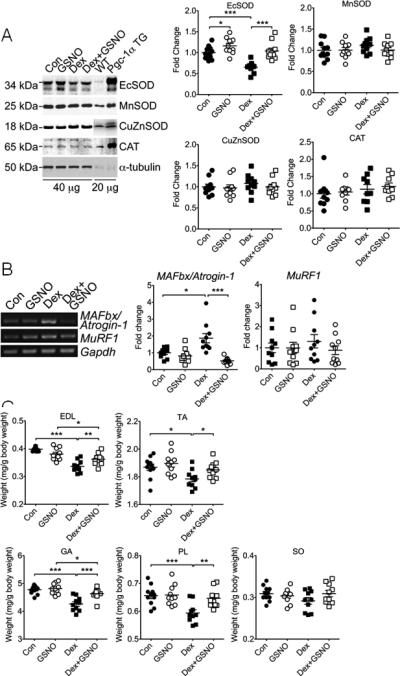

We have recently shown that an NO-dependent antioxidant defense system may underlie the resistance of oxidative muscles to catabolic muscle wasting3, 6, 16. To determine whether NO donor is sufficient to provide protection in vivo and to identify the antioxidant gene(s) that is functionally involved, we performed daily injections of dexamethasone (25 mg/kg, i.p.) with/without endogenous NO donor GSNO (2 mg/kg, i.p. twice a day) in mice for 7 days. Dexamethasone injection led to a significant increase in lipid peroxidation in skeletal muscle as assessed by 4-HNE immunoblot (Supplemental Figure S1). Dexamethasone injection caused a significant reduction of EcSOD protein expression (−29.7%, p<0.001), but not for CuZnSOD, MnSOD or catalase (Figure 1A). GSNO alone induced a moderate increase of EcSOD (p<0.05) and completely prevented the reduction of EcSOD protein expression induced by dexamethasone (Figure 1A). Dexamethasone induced a significant increase of ubiquitin E3 ligase MAFbx/Atrogin-1 mRNA (1.9-fold, p<0.05), which was completely blocked by GSNO (Figure 1B). No significant differences were detected for MuRF1 mRNA. Importantly, dexamethasone injection induced significant atrophy in fast-twitch, glycolytic EDL (−14.5%, p<0.001), tibialis anterior (−4.6%, p<0.05), gastrocnemius (−10.8%, p<0.001) and plantaris muscles (−9.5%, p<0.001), but not in slow-twitch, oxidative soleus muscle. Therefore, endogenous NO donor administration significantly attenuated muscle atrophy in all the fast-twitch, glycolytic muscles (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Systemic administration of endogenous NO donor GSNO induces EcSOD expression and prevents dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy. Wild type mice were subjected to daily injections of dexamethasone (Dex) or saline as control (Con) with/without endogenous NO donor GSNO for 7 days. Various muscles were harvested for muscle weight measurements, and plantaris muscles were processed for immunoblot and semi-quantitative PCR analyses. A) Immunoblot images of antioxidant enzymes in plantaris muscle (40 μg total protein) with samples from a MCK-Pgc-1α transgenic mouse (Pgc-1α TG) and a wild-type littermate (WT) as positive and negative controls (20 μg), respectively. α-tubulin was probed as loading control. Quantitative and statistical analyses are presented on the right (n=9-11/group); B) Images of semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis for MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA with quantitative and statistical analyses presented on the right (n=9-11/group); and C) Quantification of muscle weight of EDL, tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius (GA), plantaris (PL) and soleus (SO) muscles from mice. Data are presented as normalized muscle weight by body weight (n=9-11/group). *, ** and *** denote p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively.

EcSOD is highly expressed in oxidative muscle, induced by endurance exercise training and accumulates at capillary endothelial cells

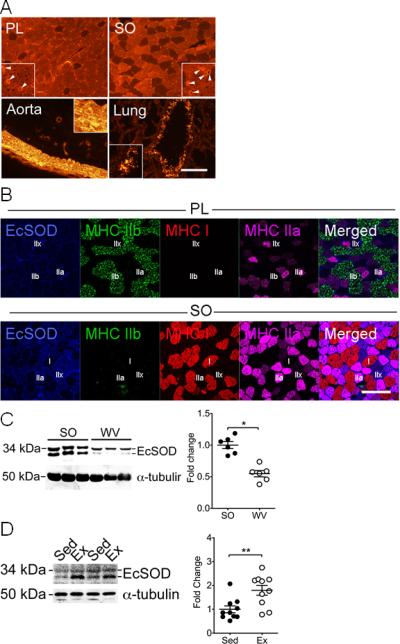

To determine which type(s) of muscle fibers expresses EcSOD, we employed immunofluorescence. We found that EcSOD was expressed at a moderate level in most of the fibers in fast-twitch, glycolytic plantaris muscle (Figure 2A). In contrast, EcSOD was highly expressed in most of the fibers in slow-twitch, oxidative soleus muscle with clear evidence of enrichment at capillary endothelial cells (Figure 2A, indicated by arrows). The specificity of the immunofluorescence was confirmed both by negative staining without primary antibody (not shown) and by the positive staining of aortic smooth muscle and bronchioles of the lung (Figure 2A). Fiber type analysis revealed that EcSOD was primarily expressed by type IIa and IId/x myofibers (Figure 2B) while neither type IIb nor type I fibers expressed detectable levels of EcSOD. Furthermore, immunoblot analysis provided clear evidence that EcSOD is expressed more abundantly in slow-twitch, oxidative soleus muscle than fast-twitch, glycolytic white vastus lateralis muscle (p<0.05; Figure 2C). Finally, voluntary running (4 wks) induced EcSOD protein expression in plantaris muscle (+79.9%, p<0.01; Figure 2D). Therefore, EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle is enhanced by contractile activities, which may underlie the protective effects of exercise training and oxidative phenotype3, 6

Figure 2.

EcSOD is highly expressed in oxidative muscle and is induced by endurance exercise training. Various tissues were harvested from wild type mice and from sedentary mice and exercise trained mice after 4 weeks of voluntary running and processed for immunoblot analysis and immunohistochemistry. A) Immunofluorescence staining showing EcSOD expression in plantaris (PL) and soleus (SO) muscle sections in comparison with the aorta and lung sections. High magnification images were shown in the brackets with arrows pointing to the capillary endothelial cells. Scale bar = 100 μm; B) Immunofluorescence staining of PL and SO muscle sections showing EcSOD (blue) is mainly expressed by type IIa (pink) and IId/x (fibers with no staining) myofibers; C) Immunoblot images of EcSOD protein in SO and white vastus lateralis (WV) muscles (40 μg total protein) with α-tubulin as loading control. Quantitative and statistical analyses are presented on the right (n=6/group); and D) Immunoblot images of EcSOD protein in plantaris muscle (40 μg total protein) from sedentary (Sed) and exercise trained (Ex) mice after 4 weeks of voluntary running with α-tubulin as loading control. Quantitative and statistical analyses are presented on the right (n=10/group). * and ** denote p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively.

Somatic gene transfer-mediated EcSOD overexpression in adult skeletal muscle protects myofibers from atrophy

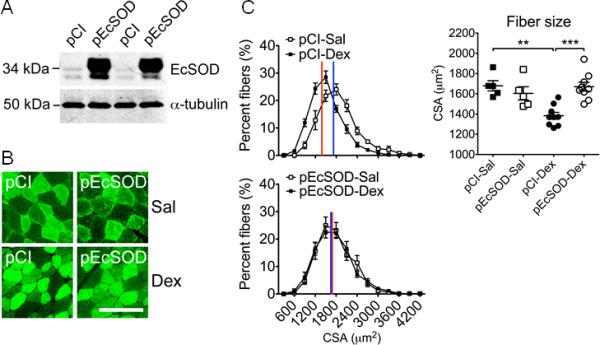

Our finding that dexamethasone injection decreases EcSOD expression in atrophying muscle suggests that reduced EcSOD expression plays a role in catabolic wasting. Blocking the reduction of EcSOD expression along with the prevention of muscle atrophy by GSNO administration further supports this notion. To determine if enhanced EcSOD expression is sufficient to protect myofibers from catabolic wasting, we performed electric pulse-mediated gene transfer in fast-twitch, glycolytic tibialis anterior muscle. High levels of exogenous EcSOD expression were confirmed when compared to the contralateral control muscle (pCI-neo) (Figure 3A). Systemic administration of dexamethasone resulted in a leftward shift (reduction) of the fiber size histogram with a significant reduction of the mean cross-sectional area (CSA) in pCI-neo transfected myofibers (−14.5%, p<0.01), whereas myofibers transfected with EcSOD were protected from atrophy (Figure 3B and 3C).

Figure 3.

Somatic gene transfer-mediated EcSOD overexpression in adult skeletal muscle is sufficient to prevent dexamethasone-induced catabolic muscle wasting. Ten days after electric pulse-mediated gene transfer in tibialis anterior muscles (see Methods), mice received daily injections of dexamethasone (Dex) or saline (Sal) as control for 7 days, and the tibialis anterior muscles were harvested and processed for protein and muscle fiber size analyses by immunoblot and fluorescent microscopy. A) Immunoblot images of EcSOD protein expression in left tibialis anterior muscle transfected with pEcSOD and the contralateral control muscle transfected with empty vector pCI-neo (pCI) with α-tubulin as loading control (40 μg total protein); B) Fluorescent microscopy images of muscle sections with co-transfection of pGFP3; and C) Histograms of fiber size distribution according to cross-sectional area (CSA) (left, top and bottom panels) and comparison of the mean CSA across treatment conditions (right panel, n=5-9/group). ** and *** denote p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively.

Muscle-specific EcSOD expression in transgenic mice significantly attenuates muscle wasting

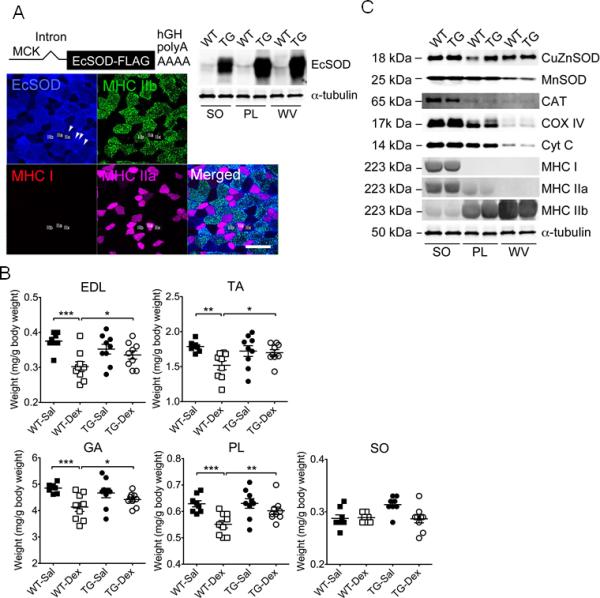

To further ascertain the protective role of EcSOD in catabolic muscle wasting, we generated a transgenic mouse line with muscle-specific overexpression of EcSOD under the control of the MCK promoter (Figure 4A, top left panel). We detected significantly greater EcSOD protein expression in skeletal muscles in MCK-EcSOD mice than in the wild-type littermates (Figure 4A, top right panel). The increases appeared to be more profound in plantaris and white vastus lateralis muscles than in soleus muscle. Immunofluorescence of EcSOD along with fiber typing analysis showed that exogenous EcSOD was highly expressed in type IIb fibers (Figure 4A, bottom panel). These fiber type-specific expression patterns are consistent with the notion that the MCK promoter is more active in fast-twitch, glycolytic fibers. EcSOD also appeared to be enriched at endothelial cells (Figure 4A, bottom panel by arrows). Consistent with findings presented in Figure 1, dexamethasone injection induced muscle mass loss in wild-type mice by −27.5% for EDL (p<0.001), −19.5% for tibialis anterior (p<0.01), 19.0% for gastrocnemius (p<0.001) and 14.7% for plantaris (p<0.001) muscles, but not in soleus muscle (Figure 4B). More importantly, dexamethasone injection did not cause significant reduction in muscle mass in any of these muscles in MCK-EcSOD mice, suggesting that enhanced EcSOD expression is sufficient to protect fast-twitch, glycolytic fibers from catabolic wasting (Figure 4B). Protein expression of antioxidant enzymes (CuZnSOD, MnSOD and Catalase), mitochondrial (COX IV and Cyt C) and contractile proteins (MHC I, IIa and IIb) were not significantly different between MCK-EcSOD mice and the wild-type littermates in these muscles (Figure 4C), suggesting that the protection in MCK-EcSOD mice was most likely due to enhanced antioxidant function, not adaptive responses induced by the transgene overexpression.

Figure 4.

Muscle-specific EcSOD transgenic mice are resistant to dexamethasone-induced catabolic muscle wasting. Skeletal muscles were harvested from MCK-EcSOD mice (TG) and wild type littermates (WT) and processed for immunofluorescence and immunoblot analyses. Muscles were also harvested for muscle weight from TG and WT mice following 7 days of dexamethasone injections (Dex) with saline (Sal) injections as control. A) EcSOD transgene construct is illustrated at the top. Immunoblot images of EcSOD expression in soleus (SO), plantaris (PL) and white vastus lateralis (WV) muscles from TG and WT mice (40 μg total protein) with α-tubulin as loading control are presented on the right. Immunofluorescence images are presented at the bottom showing EcSOD overexpression mainly in fast-twitch, glycolytic type IIb fibers (green) with enrichment around endothelial cells (indicated by arrows); B) Quantification of muscle weight in EDL, tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius (GA), PL and SO muscles as normalized muscle weight by body weight (n=9-12/group); and C) Immunoblot images of other antioxidant enzymes, mitochondrial and muscle contractile proteins in SO, PL and WV muscle in TG and WT mice. *, ** and *** denote p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively.

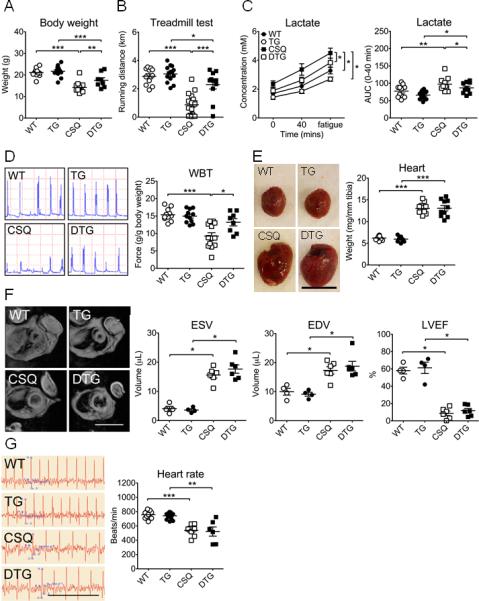

Muscle-specific EcSOD transgenic mice are resistant to cachexia and exercise intolerance induced by CHF

Our previous studies6, 16 and the current findings (Figure 1, 3 and 4) suggest that enhanced EcSOD expression is sufficient to preserve skeletal muscle mass and function under conditions of cachexia. We expected that MCK-EcSOD mice would be resistant to CHF in developing cachexia and exercise intolerance. To this end, we generated MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ double transgenic mice by crossbreeding. Although α-MHC-CSQ and MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ double transgenic mice had similar mortality probably due to severe dilated cardiomyopathy (Supplemental Figure S2), a significant attenuation of cachexia (assessed by body weight) was observed in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ double transgenic mice at 7 wks of age compared with α-MHC-CSQ mice (p<0.01; Figure 5A). Importantly, CHF-induced exercise intolerance as indicated by a dramatic reduction in treadmill running distance (p<0.001) was blunted in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (p<0.001 vs. CSQ; Figure 5B). This functional protection was confirmed by blood lactate levels; all four groups of mice displayed increases in blood lactate, but the highest levels independent of time points were observed in α-MHC-CSQ mice (p<0.05 vs. WT, TG, DTG; Figure 5C). The area under curve of blood lactate for the first 40 min of the running test was significantly higher in α-MHC-CSQ mice compared with wild-type mice (p<0.01), which was blunted in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (p<0.05 vs. CSQ). Non-invasive whole body tension test showed that α-MHC-CSQ mice have a significantly reduced force production (39.9%, p<0.01) compared with wild-type mice (Figure 5D), which was also blunted in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (p<0.05 vs. CSQ).

Figure 5.

Muscle-specific EcSOD transgenic mice are resistant to cardiac cachexia and exercise intolerance. MCK-EcSOD mice (TG) were crossbred with α-MHC-CSQ mice (CSQ) to generate MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ double transgenic mice (DTG). These mice were analyzed for body weight, running capacity, whole body tension, electrocardiography and MRI with wild-type littermates (WT) as control. A) Body weight at 7 wks of age (n=8-14/group); B) Treadmill running test at 5 wks of age; C) Blood lactate levels (n=11-17/group) during treadmill running test (left) and the area under the curve (AUC) during the first 40 min of the test (right); D) Representative force production records of WBT at 7 wks of age (left) with quantitative and statistical analyses presented on the right (n=8-13/group); E) Representative heart images (left; bar = 1 cm) with quantitative and statistical analyses presented on the right (n=10-12/group); F) Representative MRI (left; scale bar = 2 cm) of the thoracic chambers with quantification of end-systolic volume (ESV), end-diastolic volume (EDV) and left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) of the heart at 6 wks of age (n=4-6/group); and G) Representative CKG recordings (left, scale bar = 0.5 sec) and quantification of the heart rate (right) at 7 wks of age (n=6-16/group). *, ** and *** denote p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001, respective

Improved skeletal muscle function in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice could theoretically be a result of improved cardiac function by protection from overexpressed EcSOD redistributing to the heart. To test this possibility, we first performed immunoblot and semi-quantitative RT-PCR and found significantly increased EcSOD protein in the heart without increased EcSOD mRNA (Supplemental Figure S3) along with elevated EcSOD in the serum in MCK-EcSOD mice, suggesting that muscle EcSOD redistributed to the heart through the circulation. MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice, however, developed the same degree of cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 5E) and reduction of ejection fraction as α-MHC-CSQ mice (Figure 5F). Electrocardiography showed significantly increased QRS intervals (Table) and decreased heart rate (p<0.01) in these mice to the same degree (Figure 5G). Therefore, reduced cachexia and improved muscle function in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice did not appear to be a result of improved cardiac function. We also crossbred MCK-EcSOD mice with a genetic model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), SOD1-G93A mice. SOD1-G93A mice harbor transgene expressing autosomal dominant fashion of a mutant form of CuZnSOD that results in ALS-like motor neuron disease. SOD1-G93A and SOD1-93A:MCK-EcSOD mice had similar survival curve (Supplemental Figure S5) with significant reduction of body weight at 14 wks of age and reduced muscle force production at 8 weeks of age (Supplemental Figure S5). Therefore, EcSOD did not provide protection for skeletal muscle when the insults were of motor neuron origin.

Table.

Muscle-specific EcSOD expression does not provide significant protection against CHF in α-MHC-CSQ mice as assessed by electrocardiography.

| WT (n = 11) | TG (n = 16) | CSQ (n = 8) | DTG (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (ms) | 25.1±1.3 | 26.1±0.7 | 29.9±3.1*** | 38.9±6.8† |

| QRS (ms) | 10.9±0.2 | 10.8±0.2 | 16.5±1.8† | 17.4±2.0§§§ |

| QT (ms) | 39.6±0.8 | 40.4±0.7 | 57.6±4.1† | 64.4±8.6§§§ |

Data were obtained from MCK-EcSOD (TG), α-MHC-CSQ (CSQ) and MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ double transgenic mice (DTG) and their wild-type littermates (WT) and presented as mean ± SE.

denote p<0.01, respectively, vs. WT

denote p<0.001, respectively, vs. WT

denotes p<0.05 vs. CSQ

denotes p<0.001 vs. TG.

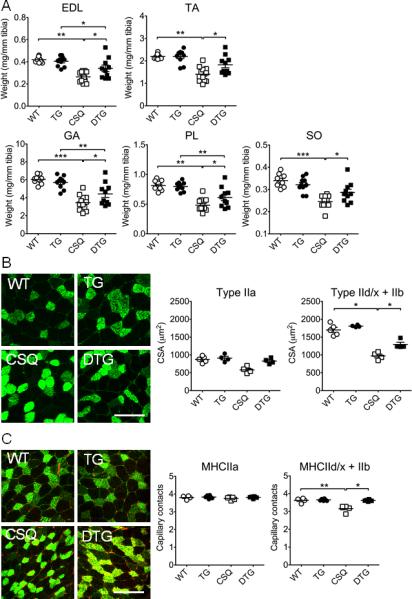

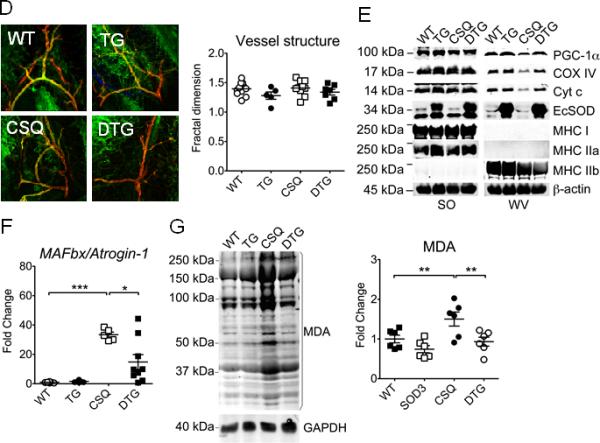

Muscle-specific EcSOD transgenic mice are resistant to CHF in developing cachexia and multiple abnormalities

To obtain structural and biochemical evidence of EcSOD-mediated protection, we measured muscle mass and normalized by tibia length to minimize the effect of body weight reduction. CHF led to a significant loss of muscle mass in EDL (−38.4%; p<0.01), tibialis anterior (−37.3%; p<0.01), gastrocnemius (−42.3%; p<0.001), plantaris (−43.3%; p<0.01) but to a less degree in soleus (−28.7%; p<0.001) muscles in α-MHC-CSQ mice compared to the wild-type littermates, which were significantly attenuated in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (Figure 6A). Fiber size analyses showed that α-MHC-CSQ mice had significantly reduced IId/x/IIb fiber size (−42.8%; p<0.05) (Figure 6B), which was blunted by EcSOD overexpression (p<0.05 vs. CSQ). Consistent with our previous finding3, α-MHC-CSQ mice had significantly decreased capillary contacts in glycolytic type IId/x/IIb fibers (p<0.01), but not in oxidative type IIa fibers. The loss of capillarity was significantly attenuated in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (p<0.05 vs. CSQ; Figure 6C). We also performed whole mount immunofluorescence staining for CD31 and smooth muscle α-actin in FDB muscle and measured the fractal dimension of microvessels (arterioles and venules), a measure of number of branches and microvessels. There were no significant differences in fractal dimension among different groups (Figure 6D), suggesting that vascular rarefaction did not occur at the arteriole and venule levels in α-MHC-CSQ mice. α-MHC-CSQ mice are known to have reduced mitochondrial (Cyt C, COX IV) and PGC-1α protein expression indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction in fast-twitch, glycolytic muscles3, 6. Here, we showed that a preferentially reduced expression of these proteins in fast-twitch, glycolytic white vastus lateralis muscle was absent in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (Figure 6D), suggesting that overexpression of EcSOD is sufficient to block CHF-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle. Consistently, CHF condition in α-MHC-CSQ mice did not cause any significant changes in myosin heavy chain protein isoforms, and EcSOD overexpression alone in MCK-EcSOD mice did not cause compensatory changes either. Real-time PCR analysis showed that α-MHC-CSQ mice had significantly elevated MAFbx/Atrogin-1 mRNA (p<0.001), which was significantly reduced in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (p<0.05 vs. CSQ) (Figure 6F). We did not detect significantly differences of apoptosis assessed by TUNEL staining (Supplemental Figure S5). Most importantly, we have performed three different analyses to determine if EcSOD overexpression had any significant impact on oxidative stress induced by CHF. We found that CHF (in α-MHC-CSQ mice) led to significantly elevated levels of oxidative stress markers, MDA and protein carbonyls, in fast-twitch, glycolytic white vastus lateralis muscle, which were significantly reduced in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice (Figure 6G and Supplemental Figure 6S). A similar trend, although not statistically significant, was found for another oxidative stress marker of lipid peroxidation, 4-HNE (Supplemental Figure 6S). These findings provide evidence for EcSOD function in protecting skeletal muscle from cardiac cachexia at molecular, biochemical, structural and functional levels likely through its ectopic antioxidant function.

Figure 6.

Muscle-specific overexpression of EcSOD prevents CHF-induced catabolic muscle wasting, loss of mitochondria, vascular rarefaction and oxidative stress. Skeletal muscles were harvested from MCK-EcSOD (TG), α-MHC-CSQ (CSQ) and MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ double transgenic mice (DTG) and their wild-type littermates (WT) at 7 wks of age and processed for measurements of muscle weight, muscle fiber size, contractile and mitochondrial protein expression, atrogene mRNA expression and oxidative stress. A) Quantification of muscle weight normalized by tibia length in EDL, tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius (GA), plantaris (PL) and soleus (SO) muscles (n=9-12/group); B) Immunofluorescence images of type IIa (green) and type IId/x/IIb fibers (negative staining) with quantification of fiber size in plantaris muscle (n=4-5/group); C) Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (red) and MHC IIa (green) with quantification of fiber type specific capillary contacts in plantaris muscle (n=4-5/group); D) Whole mount immunofluorescence staining of CD31 (green) and smooth muscle α-actin (red) in FDB muscle (left) with quantification of the fractional dimension of microvessels (right) (n=5-12/group); E) Representative immuoblot images of PGC-1α, COX IV, Cyt c, EcSOD, MHC I, MHC IIa, and MHC IIb proteins in SO and white vastus lateralis muscles (WV) with β-actin as loading control; F) Real-time PCR analysis for MAFbx/Atrogin-1 mRNA expression in PL muscle (n=7-9/group); and G) Representative immunoblot images of protein carbonylation in WV muscle with GAPDH as loading control. *, ** and *** denote p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively.

Discussion

Studies with genetic and pharmacological interventions in cultured myocytes and intact skeletal muscles have provided ample evidence that intracellular antioxidant defenses are critical in maintaining normal redox state, muscle mass and function28, 29. Here, we provide clear in vivo evidence that EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle is reduced under glucocorticoidism, a condition of many chronic diseases including CHF that is associated with increased oxidative stress30, muscle wasting and loss of muscle function18. We showed that systemic administration of endogenous NO donor could attenuate skeletal muscle atrophy induced by dexamethasone in mice concurrent with a restoration of EcSOD expression. These findings suggest that NO-dependent EcSOD expression is important for muscle maintenance in vivo. We then employed two independent genetic approaches and showed that myofibers with acquired EcSOD expression do not undergo significant atrophy upon glucocorticoidism. Muscle-specific EcSOD transgenic mice are resistant to CHF, displaying significant protections against cachexia, exercise intolerance, and loss of mitochondria, rarefaction of microvasculature, and increased atrophy gene expression in skeletal muscle. Most importantly, we have shown evidence of reduced oxidative stress when EcSOD is ectopic overexpressed in a mouse model of cardiac cachexia. These findings provide for the first time unequivocal evidence that induced EcSOD expression protects myofibers from catabolic muscle wasting in vivo, suggesting that promoting EcSOD expression by augmenting NO bioavailability in skeletal muscle could be an effective intervention for CHF patients.

NO plays important signaling role in physiological and pathological processes. We have reported that injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a major mediator of sepsis, induces greater NO production in slow-twitch, oxidative muscle than in fast-twitch, glycolytic muscle in mice3, 16. Since these oxidative muscles are resistant to catabolic muscle wasting under many disease conditions, the findings suggest that elevated NO production is protective. Our previous studies in cultured myocytes provided further evidence for a functional link between NO and antioxidant gene expression6, 16. Consistently, the data presented in this and previous studies16, 31 showed robust induction of EcSOD expression when there is increased NO bioavailability, suggesting that NO-induced EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle may contribute significantly to the protection associated with oxidative phenotype.

The functional importance of EcSOD has been shown by its reduced expression associated with various chronic diseases10, 11, and by the fact that genetic deletion and overexpression of EcSOD leading to exacerbation and protection against pathological changes in animal models of diseases, respectively12-15. Glucocorticoids are used as therapeutic agents due to their potent anti- inflammatory and immunosuppressive functions; however, high dose and long-term use of glucocorticoids causes muscle atrophy22, 32. Previous studies and our current data support an increased oxidative stress induced by dexamethasone in skeletal muscle with direct evidence of increased free radicals22, 33. Oxidative stress may promotes catabolic wasting and loss of muscle function through cell signaling, impairment of contractile protein and promotion of protein degradation4, 5, 34, 35. Here, we provide new evidence for reduced EcSOD protein expression in catabolic muscle wasting and the functional importance of the NO-mediated EcSOD expression in protection against catabolic wasting.

A key question is how EcSOD protects skeletal muscle from atrophy. Since EcSOD is the only isoform of superoxide dismutase that is secreted to the extracellular space, one straightforward explanation is that elevated extracellular ROS, which could be scavenged by EcSOD, plays an importantly role in cachexia and exercise intolerance. Several pathological steps might be relevant here. First, extracellular ROS could cause endothelial cell apoptosis36, leading to vascular rarefaction, an important feature of cardiac cachexia. Vascular rarefaction not only impairs microcirculation and tissue perfusion but also exacerbates muscle wasting due to hypoxia. Second, superoxide reacts readily with NO to reduce NO bioavailability37, impairing exercise-induced increase of blood flow and contributing to exercise intolerance. Finally, extracellular ROS-mediated intracellular ROS production and signaling38 may play an important role in catabolic muscle wasting. Enhanced EcSOD expression could provide protection through one or more of these mechanisms. Studies showing protective effects of antioxidants when applied directly to cultured cells appear to be consistent with EcSOD function in scavenging extracellular superoxide; however, in light of the findings that EcSOD can be internalized by cells that it binds9, elevated intracellular EcSOD in myofibers and/or other cells in skeletal muscle may also contribute to the protection.

The protective role of EcSOD is likely mediated by its antioxidant properties. Based on the evidence of reduced oxidative stress markers and atrogene expression in glycolytic muscles (Figure 6F and 6G), we believe that transgenic overexpression of EcSOD in skeletal muscle exerts its protective function by counteracting oxidative stress induced by CHF. The findings of muscle mass, mitochondrial protein and vascular rarefaction are all extremely consistent with this notion. Future studies should focus on elucidating the necessity of EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle in maintain muscle mass and function under catabolic wasting conditions.

It has been shown that EcSOD expression by smooth muscle can be enhanced by exercise training in an NO-dependent manner31, and EcSOD mRNA is increased by acute exercise in skeletal muscle39. It has also been shown recently that exercise training protects oxidative stress and proteasome-dependent protein degradation in CHF-induced skeletal muscle atrophy40. An unanswered question is which effecter gene(s) is responsible for the enhanced antioxidant function induced by exercise training. Our findings suggest EcSOD could be such an important player. We show here that exercise training promotes EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle (Figure 2), and that enhanced EcSOD expression is sufficient to provide protection against cardiac cachexia and exercise intolerance.

Another issue is whether enhanced expression of EcSOD from skeletal muscle redistributes to the extracellular space of the heart leading to improved cardiac function and preventing cachexia. EcSOD-mediated protection against cardiac toxicity has been shown by Kliment et al where EcSOD global knockout mice showed exacerbated cardiac dysfunction, myocardial apoptosis and fibrosis following doxorubicin injection41. We have previously shown that adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of EcSOD in the heart elicits protective effects on cardiac function following myocardial infarction in rabbits42. In this study, although forced expression of EcSOD from skeletal muscle redistributed to the heart (Supplemental Figure S3), it did not improve cardiac function and prevent premature death. These findings allowed us to focus on the impact of ectopic EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle on catabolic muscle wasting without confounding factors of EcSOD overexpression in impeding heart failure. Sicne abnormal calcium and G-protein coupling signaling is caused by calsequestrin overexpression from within cardiac myocytes43, the negative findings of EcSOD effects in the heart suggest that elevated EcSOD in the heart of α-MHC-CSQ mouse is not enough to deal with such a severe CHF condition or with pathogenesis of CHF of an intracellular origin. Previous findings support the view that exercise intolerance in CHF is a result of skeletal muscle abnormalities although the failing heart is the primary cause44-46. Consistent with this scenario, our findings suggest that the improved skeletal muscle outcomes in MKC-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice were not due to improved cardiac function. Our measurements of baseline heart function, heart weight, skeletal muscle weight, and survival curve collectively suggest that EcSOD overexpression had a negligible impact on the progression of heart failure induced by cardiac overexpression of calsequestrin in our model. On the contrary, skeletal muscle abnormalities are significantly blocked/attenuated along with improved contractile function and exercise capacity. We, therefore, believe that the effects of elevated EcSOD in the heart on cardiac function, if present, likely has a minor impact on exercise capacity. It would be interesting to ascertain whether muscle overexpression of EcSOD is protective against other types of CHF.

The concept that exercise intolerance in CHF results from multiple skeletal muscle abnormalities will be instrumental to developing effective interventions. We have previously shown that CHF leads to preferential vascular rarefaction in fast-twitch, glycolytic muscle fibers in CHF3, and that skeletal muscles with overexpression of PGC- 1α have significantly elevated EcSOD expression, less muscle atrophy and vascular rarefaction under the condition of CHF6. Here, we have again detected vascular rarefaction in fast-twitch, glycolytic fibers in α-MHC-CSQ mice, which was significantly attenuated by EcSOD overexpression. Since EcSOD accumulates at the endothelium, EcSOD may also protect endothelial cells against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. We have also previously shown that skeletal muscles undergoing catabolic wasting lose mitochondria with reduced expression of PGC-1α and increased oxidative stress3, 6, which may contribute directly to exercise intolerance. The fact that EcSOD overexpression prevents the reduction of mitochondrial and PGC-1α proteins strongly suggests that ROS induced by CHF induces pathological events in muscle. This could explain why enhanced EcSOD expression in skeletal muscle can provide potent protection and lead to preserved exercise capacity in MCK-EcSOD:α-MHC-CSQ mice. Previous studies have also linked oxidative stress to catabolic muscle wasting with evidence for enhanced ubiquitin-proteasome16, 47-49 and the autophagy-lysosome systems22, 50. The link of oxidative stress to autophagy, particularly mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy), may underlie the loss of mitochondria in CHF. A vicious cycle between oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction could be critical for the development of cardiac cachexia and exercise intolerance.

Finally, we have previously shown that overexpression of PGC-1α in skeletal muscle leads to increased iNOS, eNOS, EcSOD, MnSOD, CuZnSOD and CAT expression in skeletal muscle along with increased FOXO and Akt phosphorylation6. We postulated that PGC-1α enhances FOXO and Akt phosphorylation in parallel with enhanced NO-antioxidant defense axis. Our current findings, consistent with this posulation, suggest that increased NO can directly stimulate EcSOD in skeletal muscle providing protection. It is of note that increased NO alone without overexpression of PGC-1α only stimulates EcSOD, but not the other antioxidant enzymes. This NO inducibility of EcSOD expression helped us to focus on the function of this important, yet understudied, antioxidant enzyme in protection against muscle wasting.

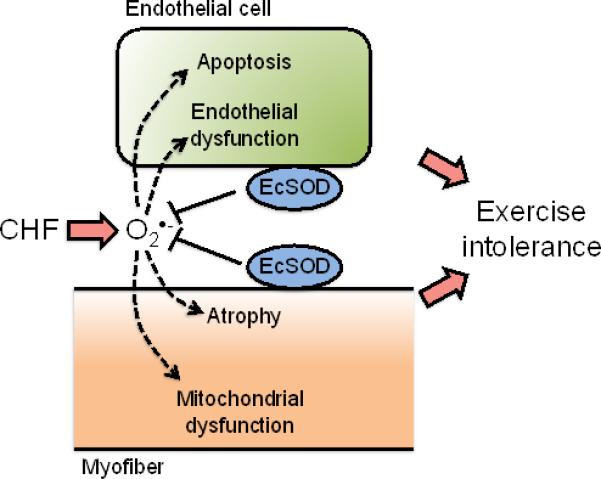

In summary, we have obtained novel findings to support that NO-mediated protection against catabolic muscle wasting is associated with enhanced EcSOD protein expression. Genetic interventions with forced expression of EcSOD in skeletal muscles significantly attenuates muscle atrophy. Importantly, muscle-specific EcSOD transgenic mice are resistant to CHF in developing cachexia and exercise intolerance with significant protection against oxidative stress, atrophic gene expression, and loss of mitochondria and microvasculature. We now propose a model where enhanced skeletal muscle EcSOD expression prevents endothelial and muscular abnormalities in cachexia and exercise intolerance likely due to the maintenance of redox homeostasis (Figure 7). The findings pave the way for targeting NO-dependent EcSOD expression for the prevention and treatment of cardiac cachexia.

Figure 7.

Schematic presentation of the working hypothesis for EcSOD-mediated protection against CHF-induced catabolic muscle wasting and exercise intolerance. CHF and the resulting systemic factors exacerbates the production of extracellular free radical superoxide ion O2.−, which in turn cause abnormalities in muscle vasculature (endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis) and muscle fibers (atrophy and mitochondrial dysfunction). These abnormalities in skeletal muscle underscore the development of exercise intolerance presumably by impairing blood supply and muscle contractile and metabolic functions. EcSOD in extracellular space in skeletal muscle may provide the first line of defense against the excessive production of extracellular free radicals under the condition of CHF, ultimately preserving muscle function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. John Sanders and R. Jack Roy for their excellent technical supports in immunofluorescence and MRI, respectively.

Sources of Funding

This project was supported by grant AR060444 (Z.Y.). The research was also supported by Nakatomi Foundation (M.O.), Postdoctoral Fellowship in Physiological Genomics by the American Physiological Society (V.A.L.), National Health Institutes T32-HL007284 (J.A.C.), and American Heart Association 12POST12030231 (J.A.C.). This research was supported in part by grant to S.M.P. (HL082838).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Sullivan M, Duscha B, Klitgaard H, Kraus W, Cobb F, Saltin B. Altered expression of myosin heavy chain in human skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:860–866. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaufelberger M, Eriksson B, Grimby G, Held P, Swedberg K. Skeletal muscle fiber composition and capillarization in patients with chronic heart failure: Relation to exercise capacity and central hemodynamics. J Card Fail. 1995;1:267–272. doi: 10.1016/1071-9164(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li P, Waters RE, Redfern SI, Zhang M, Mao L, Annex BH, Yan Z. Oxidative phenotype protects myofibers from pathological insults induced by chronic heart failure in mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:599–608. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid MB, Moylan JS. Beyond atrophy: Redox mechanisms of muscle dysfunction in chronic inflammatory disease. J Physiol. 2011;589:2171–2179. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.203356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powers SK, Smuder AJ, Judge AR. Oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy: Cause or consequence? Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2012;15:240–245. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328352b4c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geng T, Li P, Yin X, Yan Z. Pgc-1alpha promotes nitric oxide antioxidant defenses and inhibits foxo signaling against cardiac cachexia in mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1738–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauer K, Hildebrandt W, Sehl Y, Edler L, Oster P, Droge W. Improvement in muscular performance and decrease in tumor necrosis factor level in old age after antioxidant treatment. J Mol Med (Berl) 2003;81:118–125. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantovani G, Maccio A, Madeddu C, Gramignano G, Lusso MR, Serpe R, Massa E, Astara G, Deiana L. A phase ii study with antioxidants, both in the diet and supplemented, pharmaconutritional support, progestagen, and anti-cyclooxygenase-2 showing efficacy and safety in patients with cancer-related anorexia/cachexia and oxidative stress. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1030–1034. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu Y, Piper R, Richardson S, Watanabe Y, Patel P, Heistad DD. Endocytosis of extracellular superoxide dismutase into endothelial cells: Role of the heparin-binding domain. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1985–1990. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000234921.88489.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahl M, Bowler RP, Juul K, Crapo JD, Levy S, Nordestgaard BG. Superoxide dismutase 3 polymorphism associated with reduced lung function in two large populations. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:906–912. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-549OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Hou M, Li Y, Traverse JH, Zhang P, Salvemini D, Fukai T, Bache RJ. Increased superoxide production causes coronary endothelial dysfunction and depressed oxygen consumption in the failing heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H133–141. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00851.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Z, Xu X, Hu X, Zhu G, Zhang P, van Deel ED, French JP, Fassett JT, Oury TD, Bache RJ, Chen Y. Extracellular superoxide dismutase deficiency exacerbates pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction. Hypertension. 2008;51:19–25. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson LM, Jonsson J, Edlund T, Marklund SL. Mice lacking extracellular superoxide dismutase are more sensitive to hyperoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6264–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao H, Arunachalam G, Hwang JW, Chung S, Sundar IK, Kinnula VL, Crapo JD, Rahman I. Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects against pulmonary emphysema by attenuating oxidative fragmentation of ecm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15571–15576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007625107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad KM, Smith RS, Xu Y, French BA. A single direct injection into the left ventricular wall of an adeno-associated virus 9 (aav9) vector expressing extracellular superoxide dismutase from the cardiac troponin-t promoter protects mice against myocardial infarction. J Gene Med. 2011;13:333–341. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Z, Li P, Zhang M, Hannink M, Stamler J, Yan Z. Fiber type-specific nitric oxide protects oxidative myofibers against cachectic stimuli. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng T, Li P, Okutsu M, Yin X, Kwek J, Zhang M, Yan Z. Pgc-1alpha plays a functional role in exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis and angiogenesis but not fiber-type transformation in mouse skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C572–579. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00481.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasselgren PO. Glucocorticoids and muscle catabolism. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 1999;2:201–205. doi: 10.1097/00075197-199905000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naya F, Mercer B, Shelton J, Richardson J, Williams R, Olson E. Stimulation of slow skeletal muscle fiber gene expression by calcineurin in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4545–4548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones L, Suzuki Y, Wang W, Kobayashi Y, Ramesh V, Franzini-Armstrong C, Cleemann L, Morad M. Regulation of ca2+ signaling in transgenic mouse cardiac myocytes overexpressing calsequestrin. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1385–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akimoto T, Ribar T, Williams R, Yan Z. Skeletal muscle adaptation in response to voluntary running in ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase iv-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1311–1319. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00248.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClung JM, Judge AR, Powers SK, Yan Z. P38 mapk links oxidative stress to autophagy-related gene expression in cachectic muscle wasting. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C542–549. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00192.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Z, Choi S, Liu X, Zhang M, Schageman JJ, Lee SY, Hart R, Lin L, Thurmond FA, Williams RS. Highly coordinated gene regulation in mouse skeletal muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8826–8836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pogozelski AR, Geng T, Li P, Yin X, Lira VA, Zhang M, Chi J-T, Yan Z. P38gamma mitogen-activated protein kinase is a key regulator in skeletal muscle metabolic adaptation in mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlson CG, Makiejus RV. A noninvasive procedure to detect muscle weakness in the mdx mouse. Muscle Nerve. 1990;13:480–484. doi: 10.1002/mus.880130603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berr SS, Roy RJ, French BA, Yang Z, Gilson W, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Black blood gradient echo cine magnetic resonance imaging of the mouse heart. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1074–1079. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey AM, O'Neill TJt, Morris CE, Peirce SM. Arteriolar remodeling following ischemic injury extends from capillary to large arteriole in the microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2008;15:389–404. doi: 10.1080/10739680701708436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller FL, Song W, Liu Y, Chaudhuri A, Pieke-Dahl S, Strong R, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Csete M, Faulkner JA, Van Remmen H. Absence of cuzn superoxide dismutase leads to elevated oxidative stress and acceleration of age-dependent skeletal muscle atrophy. Free radical biology & medicine. 2006;40:1993–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobrowolny G, Aucello M, Rizzuto E, Beccafico S, Mammucari C, Boncompagni S, Belia S, Wannenes F, Nicoletti C, Del Prete Z, Rosenthal N, Molinaro M, Protasi F, Fano G, Sandri M, Musaro A. Skeletal muscle is a primary target of sod1g93a-mediated toxicity. Cell Metab. 2008;8:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtani T, Ohta M, Yamamoto K, Mano T, Sakata Y, Nishio M, Takeda Y, Yoshida J, Miwa T, Okamoto M, Masuyama T, Nonaka Y, Hori M. Elevated cardiac tissue level of aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptor in diastolic heart failure: Beneficial effects of mineralocorticoid receptor blocker. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R946–954. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00402.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukai T, Siegfried MR, Ushio-Fukai M, Cheng Y, Kojda G, Harrison DG. Regulation of the vascular extracellular superoxide dismutase by nitric oxide and exercise training. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1631–1639. doi: 10.1172/JCI9551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waddell DS, Baehr LM, van den Brandt J, Johnsen SA, Reichardt HM, Furlow JD, Bodine SC. The glucocorticoid receptor and foxo1 synergistically activate the skeletal muscle atrophy-associated murf1 gene. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E785–797. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00646.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konno S. Hydroxyl radical formation in skeletal muscle of rats with glucocorticoid-induced myopathy. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:669–675. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-2755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smuder AJ, Kavazis AN, Hudson MB, Nelson WB, Powers SK. Oxidation enhances myofibrillar protein degradation via calpain and caspase-3. Free radical biology & medicine. 2010;49:1152–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clavel S, Siffroi-Fernandez S, Coldefy AS, Boulukos K, Pisani DF, Derijard B. Regulation of the intracellular localization of foxo3a by stress-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in skeletal muscle cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:470–480. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00666-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho KS, Lee EH, Choi JS, Joo CK. Reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis and necrosis in bovine corneal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:911–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung O, Marklund SL, Geiger H, Pedrazzini T, Busse R, Brandes RP. Extracellular superoxide dismutase is a major determinant of nitric oxide bioavailability: In vivo and ex vivo evidence from ecsod-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2003;93:622–629. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000092140.81594.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daiber A. Redox signaling (cross-talk) from and to mitochondria involves mitochondrial pores and reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hitomi Y, Watanabe S, Kizaki T, Sakurai T, Takemasa T, Haga S, Ookawara T, Suzuki K, Ohno H. Acute exercise increases expression of extracellular superoxide dismutase in skeletal muscle and the aorta. Redox Rep. 2008;13:213–216. doi: 10.1179/135100008X308894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunha TF, Bacurau AV, Moreira JB, Paixao NA, Campos JC, Ferreira JC, Leal ML, Negrao CE, Moriscot AS, Wisloff U, Brum PC. Exercise training prevents oxidative stress and ubiquitin-proteasome system overactivity and reverse skeletal muscle atrophy in heart failure. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kliment CR, Suliman HB, Tobolewski JM, Reynolds CM, Day BJ, Zhu X, McTiernan CF, McGaffin KR, Piantadosi CA, Oury TD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase regulates cardiac function and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:730–742. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Q, Bolli R, Qiu Y, Tang XL, Guo Y, French BA. Gene therapy with extracellular superoxide dismutase protects conscious rabbits against myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:1893–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.14.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho M, Rapacciuolo A, Koch W, Kobayashi Y, Jones L, Rockman H. Defective beta-adrenergic receptor signaling precedes the development of dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice with calsequestrin overexpression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22251–22256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan M, Green H, Cobb F. Skeletal muscle biochemistry and histology in ambulatory patients with long-term heart failure. Circulation. 1990;81:518–527. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.2.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massie B. Exercise tolerance in congestive heart failure. Role of cardiac function, peripheral blood flow, and muscle metabolism and effect of treatment. Am J Med. 1988;84:75–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jondeau G, Katz S, Zohman L, Goldberger M, McCarthy M, Bourdarias J, LeJemtel T. Active skeletal muscle mass and cardiopulmonary reserve. Failure to attain peak aerobic capacity during maximal bicycle exercise in patients with severe congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1992;86:1351–1356. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.5.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin B, Li Y-P. Curcumin prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced atrogin-1/mafbx upregulation and muscle mass loss. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:960–969. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Chen Y, John J, Moylan J, Jin B, Mann D, Reid M. Tnf-alpha acts via p38 mapk to stimulate expression of the ubiquitin ligase atrogin1/mafbx in skeletal muscle. Faseb J. 2005;19:362–370. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2364com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McClung JM, Kavazis AN, Whidden MA, DeRuisseau KC, Falk DJ, Criswell DS, Powers SK. Antioxidant administration attenuates mechanical ventilation-induced rat diaphragm muscle atrophy independent of protein kinase b (pkb akt) signalling. J Physiol. 2007;585:203–215. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Foxo3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.