Abstract

Exact mechanism of action of umbilical cord blood (CB)-derived regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the prevention of GVHD remains unclear. On the basis of selective overexpression of peptidase inhibitor 16 in CB Tregs, we explored the related p53 pathway, which has been shown to negatively regulate miR15a/16 expression. Significantly lower levels of miR15a/16 were observed in CB Tregs when compared with conventional CB T cells (Tcons). In a xenogeneic GVHD mouse model, lower levels of miR15a/16 were also found in Treg recipients, which correlated with a better GVHD score. Forced overexpression of miR15a/16 in CB Tregs led to inhibition of FOXP3 and CTLA4 expression and partial reversal of Treg-mediated suppression in an allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction that correlated with the reversal of FOXP3 demethylation in CB Tregs. On the other hand, miR15a/16 knockdown in CB Tcons led to expression of FOXP3 and CTLA4 and suppression of allogeneic lymphocyte proliferation. Using a luciferase-based mutagenesis assay, FOXP3 was determined to be a direct target of miR15a and miR16. We propose that miR15a/16 has an important role in mediating the suppressive function of CB Tregs and these microRNAs may have a ‘toggle-switch’ function in Treg/Tcon plasticity.

INTRODUCTION

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) as defined by their phenotype of CD4+CD25+CD127lo, and increased FOXP3 expression, are emerging as a promising cellular therapy in the prevention of GVHD.1–3 Improved outcomes have been associated with Treg-based therapy both in preclinical and clinical settings.2–6 Although intracellular FOXP3 expression has been determined to be essential for Treg function,7,8 the precise mechanism by which cord blood (CB) Tregs prevent GVHD remains unclear.

FOXP3 expression has been shown to be regulated directly and indirectly, by microRNA (miRNA)-mediated gene expression.9 Recent studies suggest that miRNA-dependent post-translational regulation impacts FOXP3-dependent Treg genetic programming.10,11 As the selective disruption of miRNAs in Tregs can exacerbate autoimmunity,11 particular subsets of miRNAs have been also been proposed to mediate GVHD.12 Eight miRNAs are preferentially expressed in CB-derived Tregs. These include miR425-5p, miR181c, miR21, miR374, miR586, miR340, miR26b and miR491. In addition, two miRNAs are downregulated (miR31 and miR125a).13 However, the association between these miRNAs and FOXP3 expression and ultimately Treg function remains inconclusive. Recently, miR155 has been shown to be a potential regulator of acute GVHD12 and a direct target of FOXP3.14 However, miR155 deficiency has not shown to significantly impact the suppressive effect of Tregs.14 As such, further research is needed to identify the critical role of miRNAs in Treg function.

On the basis of genome-wide identification, peptidase inhibitor 16 (PI16) has been shown to be a target of human FOXP3 gene in naturally occurring Tregs. In addition, PI16 has been shown to be expressed on the cell surface of >80% of resting human CD25+FOXP3+ cells.15 PI16 has also been described as a surrogate surface marker for CB-derived Tregs based on correlation with their suppressive activity.15,16 We performed an exploratory analysis to identify possible miRNAs engaged in the PI16 pathway, with the goal of better understanding its role in CB Treg function.15

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures

CB Treg generation

Umbilical CB units were provided under University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board-approved protocols. CB Tregs were isolated using CD25+ magnetic-activated cell sorting according to manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergish Gladbach, Germany). Positively selected cells were cocultured with CD3/28 co-expressing Dynabeads (ClinExVivo CD3/CD28, Invitrogen Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway)17 and were maintained at 1 × 106 cells/mL by the addition of fresh medium and interleukin-2 (CHIRON Corporation, Emeryville, CA, USA) every 48–72 h to maintain a final concentration of 200 IU/mL.4,17,18

CB conventional T-cell generation

CD4+25neg cells were isolated from whole CB units by negative selection as described previously.18 Isolated cells were cultured ex vivo for 14 days in continued presence of CD3/28 beads and interleukin-2 (200 IU/mL).

PB Treg generation

Using CD4+CD25+CD127dim regulatory T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc, Auburn, CA, USA), naturally occurring Tregs were isolated from adult PB as per manufacturer’s instructions.

MLR

A two way, allogeneic MLR was performed using PBMC isolated from two unrelated donor samples as described previously.19 Cellular proliferation was measured by the incorporation of 3H-thymidine. Results were measured using a cell harvester (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and a liquid scintillation counter (Packard Meriden, Prospect, CT, USA). Results are expressed in c.p.m.

Xenogenic GVHD mouse model

All animal work was performed under University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols. Xenogenic mouse model for GVHD was developed using nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) interleukin-2Rγnull mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) that underwent sublethal whole-body irradiation (300 cGy from a 137Cs source delivered over 1 min by a J. L. Shepherd and Associates Mark I-25 Irradiator, San Fernando, CA, USA), followed by intravenous injection of human PBMC at a dose of 1 × 107, on the next day as described previously.18 In the experimental arm, CB Tregs at a dose of 1 × 107 were injected into the mice 4 h after the completion of sublethal irradiation. The mice were followed every 48 h to assess for GVHD scoring as described previously.20

RNA extraction, retro-transcription and analysis of mature miRNAs by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cell pellets using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) for miRNA analyses according to the manufacturer's protocol. For mature miRNA expression analysis, total RNA was retrotranscribed with miRNA-specific primers using the TaqMan microRNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and then quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed using TaqMan microRNA assays according to the manufacturer's protocol. The comparative cycle time (Ct) method was used to calculate the relative abundance of miRNAs compared with small nuclear RNA (snRNA) U6 as an internal control for RNA normalization.21 The profiling was performed in duplicate wells for each samples and in two independent experiments (four measurements each), and the results were presented as mean ± s.e. of the four measurements. Differences in miRNA levels were compared with Student’s t-test. Fisher exact and χ2 tests were applied to categorical variables.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed at a density of 1 × 106/50 µL in protein lysis buffer (0.25 mol/L Tris–HCl, 2% sodium dodecylsulfate, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostic, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Lysates were then separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), transferred to Hybond-P membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), probed with the appropriate antibodies: anti–human PI16 (Abnova, Walnut, CA, USA), anti-FOXP3 and anti-p53 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-CTLA-4 (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence plus kit (GE Healthcare, Humble, TX, USA) or Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA).

miRNA overexpression and knockdown

mirVana (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) inhibitors or mimics of miR15a or miR16 and negative control were obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All miRs were transfected as per the manual of the Amaxa (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) Human T cell Nucleofector kit. Briefly, 300 nm miRNA mimics (Life Technologies) were transfected into Tregs using program V24 (Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA). Forty-eight hours post transfection, RNA and protein were extracted. Samples were stored at −80 °C until analyzed.

Lentiviral transduction of conventional T cell and Treg for MLR studies

Vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G)-pseudotyped lentiviral particles were generated by the lenti-miRNA Expression System from Applied Biological Materials. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with Lenti-Combo Mix and (1) LentimiRa-GFP-has-miR-15a vector, (2) LentimiRa-GFP-has-miR-16 vector, (3) LentimiRa-OFF-has-miR-15a vector and (4) LentimiRa-OFF-has-miR-16 vector according to the manufacturer’s manual. Forty-eight to 72 h post transfection, viral supernatant was harvested, filtered through 0.45 µm filters and stored at −80 °C until required. CD4+25− cells (conventional T cell (Tcon)) were isolated using CD25 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.). Expanded Treg and Tcon cells were exposed to viral supernatant in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 200 U/mL interleukin-2. GFP+ (green fluorescent protein) cells were sorted by BD FACS Aria High-Speed Digital Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) 3 days after transduction. All experiments were performed three times.

Luciferase assay

To further evaluate the relationship between miR15a/16 and FOXP3, the Dual-Luciferase Reporter System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used. This approach has been widely used in vitro and in vivo22 and has been proposed as a system not only to detect protein–protein interactions but also to validate miRNA targets experimentally.23,24 Herein, a Firefly and Renilla dual luciferase reporter system was employed to investigate the interaction between miR15a and FOXP3. The putative target sites for the miR15a seed sequence were identified by using TargetScan25 and microRNA.org26 software. The interaction between miR15a/16 and FOXP3 was predicted by three algorithms: miranda, PITA and RNA22. A 253-bp or 232-bp fragment of FOXP3 3′-UTR encompassing the miR15a and miR16 potential target sites was cloned downstream of the firefly luciferase gene (XbaI sites) in the pGL3-control plasmids (Promega) and designated as FOXP3 wild type. PCR primers used for amplification of the FOXP3 3′-UTR were as follows: binding site 1, 5′-GTGGTTCTAGACACCCCCTCCCCCA TCATA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGTTCTAGAGGCTCTCTGTGTTTTGGGGT-3′(reverse); binding site 2, 5′-GTGGTTCTAGACCTACACAGAAGCAGCGTCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGTTCTAGAGATCAGGGCTCAGGGAATGG-3′ (reverse). To generate the 3′-UTR mutant construct (3′-UTR-del), seed regions were deleted using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and designated as FOXP3 del. QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the following primers: binding site 1, 5′-CACAGAGCC TGCCTCA CGCACAGATTACTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAAGTAATCTGTGCGTG AGGCAGGCTCTGTG-3′ (reverse); binding site 2, 5′-GAGGTCCCAACAC GTCACACACACGGCCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGGCCGTGTGTGTGACG TGTTGGGACCTC-3′ (reverse). All the constructs were verified by sequencing performed in the core facility of M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Subsequently, we plated HEK293T cells (2.2 × 105) in 96-well plates. Reporter plasmid, pGL3-3′-UTR-WT (or pGL3-3′-UTR-del), for the predicted target genes, was co-transfected with miR15a, miR16 overexpression plasmid and miR-control plasmid. The pRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid was also co-transfected as an internal control using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. After 48 h post transfection, firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were consecutively measured using a Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System kit (Promega), and luminescence was measured on Multimode Microplate Readers (BMG LABTECH, Cary, NC, USA). Luciferase activity was expressed as relative light unit, which was the ratio of firefly luminescence to renilla luminescence.

RESULTS

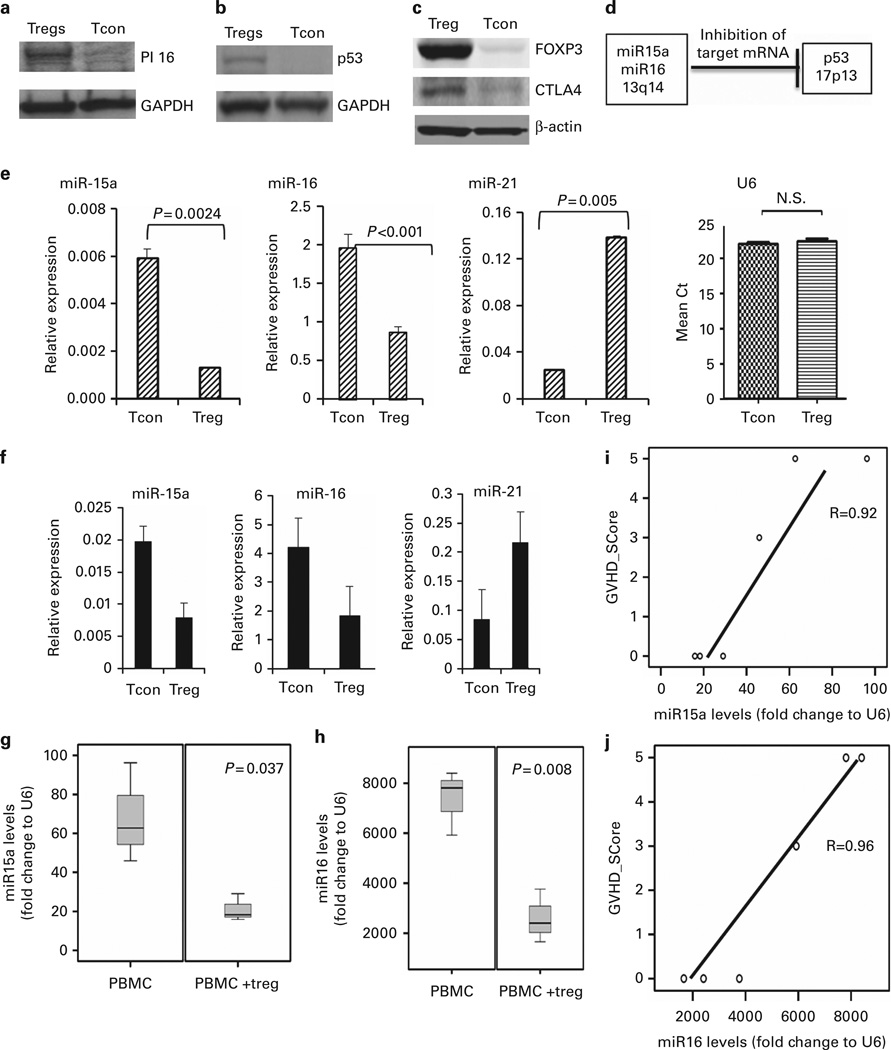

CB Tregs demonstrate increased expression of PI16 and p53

Using the method of western blotting, we demonstrated that PI16 protein expression is increased in the CB Tregs as compared with CB Tcons (Figure 1a). PI16 belongs to the cysteine-rich secretory protein family and shares linkage with p53.27,28 Also, Tregs increase p53 phosphorylation and total protein expression in senescent CD4+ T cells (Tcon), thereby controlling their proliferation.29 Therefore, we investigated the expression of p53 on CB Tregs. Using western blotting, we demonstrated increased expression of p53 protein in CB Tregs when compared with CB Tcons (Figure 1b). As a positive control, we also showed increased FOXP3 and CTLA4 expression in CB Tregs compared with CB Tcons (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. CB Tregs express low levels of miR15a/16.

(a) CB Tregs show higher expression of PI16. Equal amounts of total cell lysates from expanded Tcons and Tregs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against peptidase inhibitor 16 (PI16). The blot was stripped and reprobed with antibody against GAPDH to control for protein loading (representative blot from three different experiments is shown). (b) CB Tregs show higher expression of p53. Equal amounts of total cell lysates from expanded Tcons and Tregs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against p53. The blot was stripped and reprobed with antibody against GAPDH to control for protein loading (representative blot from three different experiments is shown). (c) CB Tregs show higher expression of FOXP3 and CTLA4. Equal amounts of total cell lysates from expanded Tcons and Tregs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against FOXP3 and CTLA4. The blot was stripped and reprobed with antibody against actin to control for protein loading (representative blot from three different experiments is shown). (d) p53 negatively regulates miR15a/16. Adapted from Fabbri et al.,24 a negative control between p53 and miR15a/16 is demonstrated in normal tissues. (e) miR15a and miR16 expression is lower in CB Tregs when compared with Tcons. miR15a and miR16 levels were quantified using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). The comparative cycle time (Ct) method was used to calculate the relative abundance of microRNAs compared with snRNA U6 as an internal control for RNA normalization. Significantly lower miR15a (P =0.0024) and miR16 (P < 0.001) were seen in CB-derived Tregs when compared with Tcons. miR21 is increased in CB Tregs (P=0.005), shown as a positive control. (f) miR15a and miR16 expression is lower in PB Tregs when compared with Tcons. miR15a and miR16 levels were quantified using qRT-PCR. The Ct method was used to calculate the relative abundance of microRNAs compared with snRNA U6 as an internal control for RNA normalization. Lower miR15a and miR16 were seen in PB-derived Tregs when compared with Tcons. miR21 is increased in PB Tregs, shown as a positive control. Decreased miR15a/16 in circulating lymphocytes of CB Treg recipients in xenogenic GVHD model. Sublethally irradiated gamma null mice were injected with human PBMC with or without preceding third party CB Treg injection in 1:1 ratio to evaluate for development of GVHD. The expression of miR15a or miR16 in the circulating lymphocytes on Day 14 for recipients of PBMC or those with Tregs and PBMC (expressed as fold change to snRNA U6, as an internal control for RNA normalization) was analyzed. (g) The miR15a levels (P=0.037; two-tailed t-test) and (h) miR16 levels (P =0.008; two-tailed t-test) were decreased in PBMC+Treg recipients when compared with PBMC-only group. The miR15a (i; regression coefficient 0.92) and miR16 (j; regression coefficient 0.96) levels in the circulating lymphocytes correlated with the GVHD score of the animals.

miR15a/16 expression is decreased in CB Tregs

Fabbri et al. showed that in normal tissues there exists an inverse relation between p53 and miR15a/16 expression (Figure 1d).24 On the basis of this observation, we explored the expression level of miR15a/16 in CB Tregs and CB Tcons. Using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR with snRNA U6 as an internal control for RNA normalization, we evaluated endogenous miR15a and miR16 levels in CB Tregs and CB Tcons. Significantly lower expression of miR15a (P = 0.0024) and miR16 (P < 0.0001) was detected in CB Tregs when compared with Tcons (Figure 1e). This experiment was independently repeated three times. Consistent with previous reports30 (and as a positive control for this study), miR21 was shown to be upregulated in CB Tregs, when compared with CB Tcons (Figure 1e). U6 normalizer was used to control for loading. Similar pattern of lower expression of miR15a/16 was also seen in PB-derived Tregs when compared with Tcon (Figure 1f). miR21 was also increased in PB-derived Tregs as positive control. As described previously,18 we used a xenogenic GVHD mouse model (Supplementary Figure 1) to study the impact of infused CB Tregs on miR15a/16 levels. Lower levels of miR15a (Figure 1g) and miR16 (Figure 1h) were seen in the circulating lymphocytes of third party CB Treg recipients as compared with PBMC-alone group at day 14. We utilized the Ferrara GVHD scoring system20 to objectively evaluate the severity of GVHD in the xenogenic mouse model. The lymphocyte miR15a (Figure 1i) and miR16 (Figure 1j) level inversely correleated with the GVHD score. Whereas, no differences were seen in the miR15a/16 expression levels when comparing CB with PB Treg (Supplementary Figure 1).

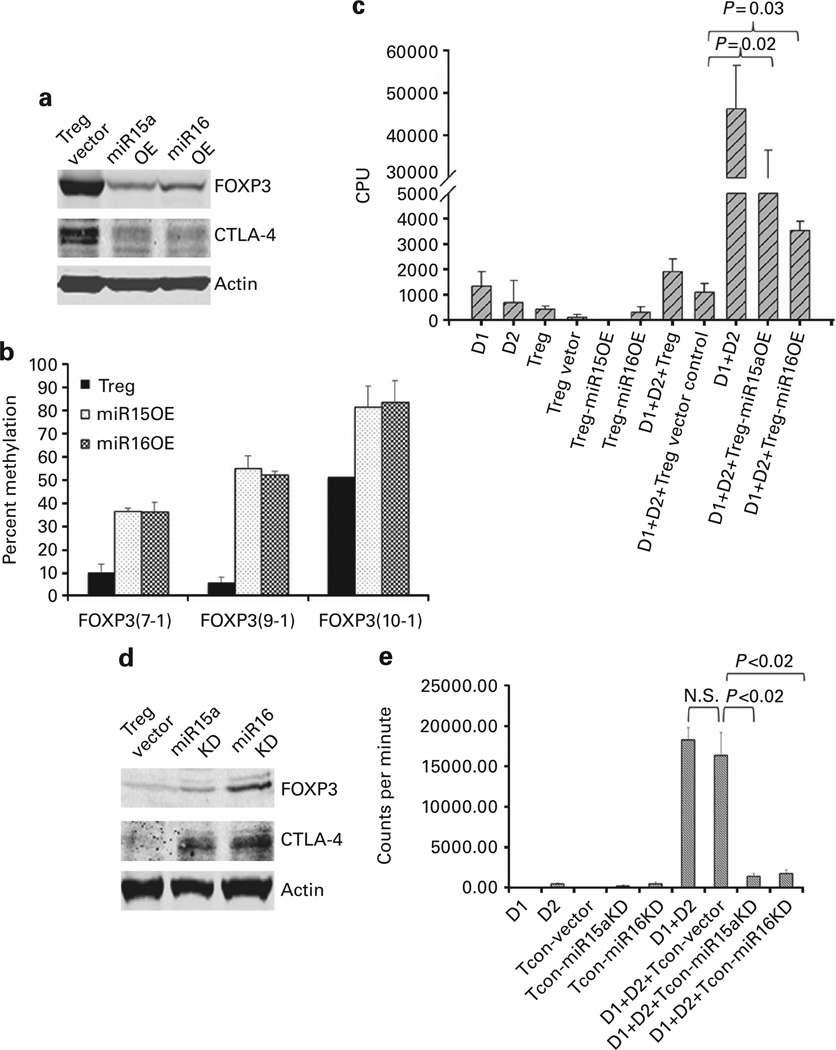

Overexpression of miR15a/16 in CB Tregs leads to a reversal of suppressive activity

To explore the direct effect of miR15a and miR16 on the better known targets that control Treg function (including FOXP3 and CTLA4), we transfected miR15a and miR16 miRNA mimics into CB Tregs by Nucleofection. Transfection led to upregulation of the expression of these miRNA activities. Cells collected 48 h after transfection exhibited overexpression (OE) of miR15a or miR16 when compared with an empty vector control (Supplementary Figure 2). Western blotting revealed that the miR15a and miR16 OE led to decreased expression of FOXP3 and CTLA4 (Figure 2a). This experiment was repeated three times. To further examine the effects of miR15a and miR16 on the functionality of Tregs, lentiviral transduction was employed to establish more stable overexpression. Seventy-two hours after transfection, GFP+ cells (co-expression of GFP used to confirm transfection efficiency) were sorted by flow cytometry and stable overexpression was demonstrated as compared with the empty vector (data not shown). Overexpression of miR15a and miR16 led to partial reversal of the FOXP3 demethylation that is essential for CB Treg function (Figure 2b).31 Although ≥85% suppression of lymphocyte proliferation was observed in the presence of non-transfected vector control Tregs, less marked suppression was observed in the presence of the miR15a OE and miR16 OE Treg (Figure 2c). There was no additive effect of combined OE of miR15a and miR16 in CB Treg (data not shown).

Figure 2. miR15a/16 mediate functional activity of CB Tregs.

(a) Overexpression (OE) of miR15a and miR16 in Tregs suppresses FOXP3 and CTLA4. Equal amounts of total lysates of Tregs with empty vector or Tregs overexpressing miR15a or miR16 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against FOXP3 and CTLA4, respectively. The blot was stripped and reprobed with an antibody against actin to control for protein loading (representative blot from three different experiments is shown). (b) miR15a/16 OE in Tregs reverses FOXP3 demethylation. Bisulfite sequencing in ex vivo-expanded UCB-derived Treg showed significant DNA demethylation of the FOXP3 gene locus at amplicons 7, 9, 10 and 11, which is partially reversed with MiR15a or miR16 overexpression in CB Tregs. X axis denotes the CpG island locus and Y axis denotes percent methylation (n=3). (c) miR15a and miR16 OE in Tregs partially reverses their suppressive function. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNC) from adult donor 1 (D1) and adult donor 2 (D2) were mixed at 1:1 ratio using 50 000 cells from each source to generate a two-way allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction, where proliferation is captured by the incorporation of 3H-thymidine. Stable overexpression of miR15a and miR16 using lentiviral transduction of CB Tregs led to partial reversal of the suppression of allogeneic lymphocyte proliferation, when added in 1:1 concentration to the effector cells. No such effect on suppression was seen with the Treg vector control cells (n=3; mean ±s.e.). (d) Knockdown of miR15a and miR16 in Tcon leads to increased FOXP3 and CTLA4 protein expression. Equal amounts of total lysates from Tcons with empty vector or Tcons subject to miR15a and miR16 knockdown were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against FOXP3 and CTLA4, respectively. The blot was stripped and reprobed with an antibody against actin to control for protein loading. (e) Knockdown of miR15a and miR16 induces suppressive function in CB Tcon cells. PB MNC from adult donor 1 (D1) and adult donor 2 (D2) were mixed at 1:1 ratio using 50 000 cells from each source to generate a two-way allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction, where proliferation is captured by the incorporation of 3H-Thymidine. Silencing of miR15a and miR16 expression using lentiviral transduction of CB Tcons was shown to induce significant suppressive activity on lymphocyte proliferation when added in 1:1 concentration to the effector cells. No such suppression was seen with the Tcon vector control cells (n=3; mean±s.e.).

Knockdown of miR15a/16 in CB Tcons induces suppressor function

Electroporation was employed to knock down miR15a or miR16 expression in Tcons. The effect on expression of FOXP3 or CTLA4 in these cells was investigated. Cells collected 48 h after transfection exhibited knockdown of miR15a or miR16 when compared with an empty vector control (Supplementary Figure 3). Using western blotting, knockdown of miR15a or miR16 in Tcons led to increased expression of FOXP3 and CTLA4 (Figure 2d). These experiments were independently repeated three times. To further explore the importance of miR15a or miR16 expression on allo-MLR, we systematically knocked down miR15a or miR16 in Tcons. Seventy-two hours after transfection, GFP+ cells (co-expression of GFP confirmed successful transfection) were sorted by flow cytometry and stable knockdown was confirmed (data not shown). Although Tcons transfected with empty vector had no impact on the magnitude of lymphocyte proliferation, knockdown of miR15a and miR16 in Tcons led to the suppression of the allogeneic lymphocyte proliferation by 90% when present at a 1:1 effector cell ratio (Figure 2e, P < 0.02 for miR15a and miR16). This experiment was repeated three times.

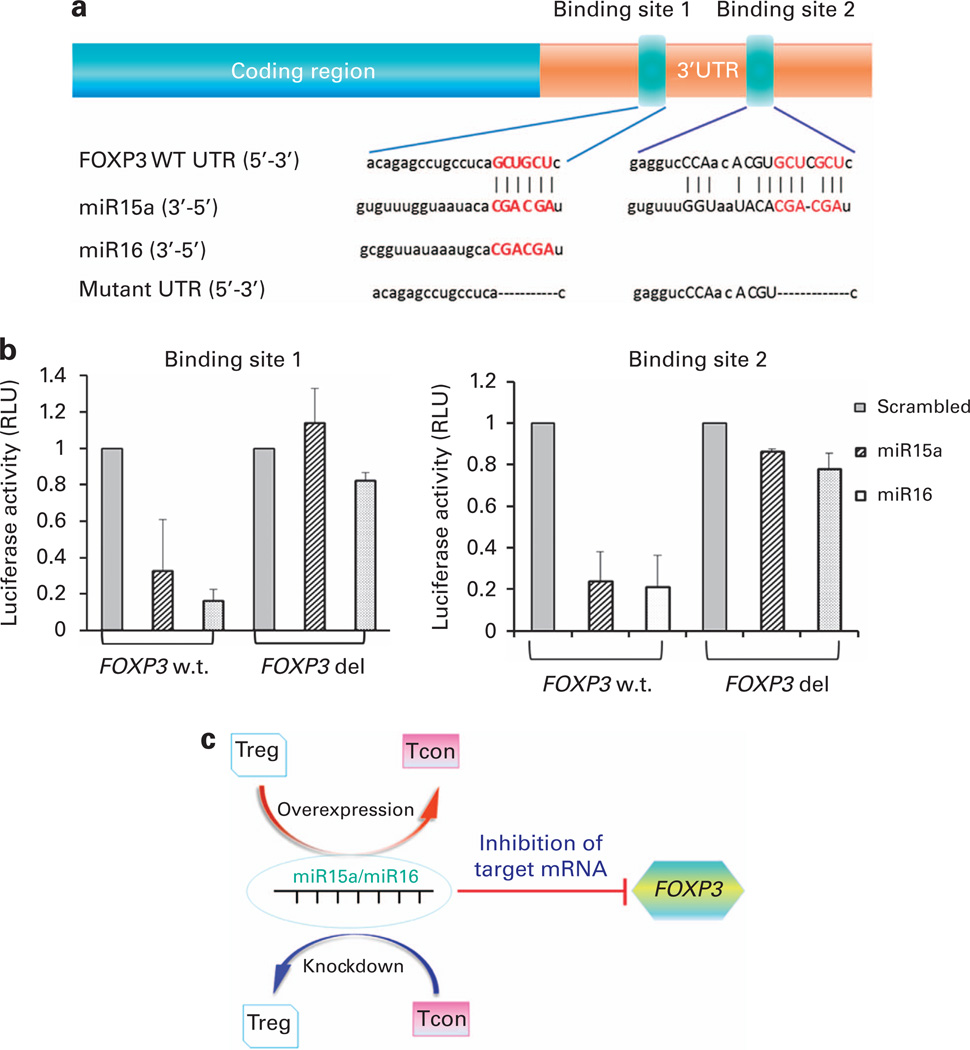

FOXP3 is a direct target of miR15a/16

To further evaluate the relationship between miR15a/16 and FOXP3, we used the Dual-Luciferase Reporter System. The interaction between miR15a/16 and FOXP3 was predicted by three algorithms: miranda, PITA and RNA22 (Figure 3a). Using the luciferase-based assay, we demonstrated that miR15a/16 had a direct binding interaction with FOXP3 at binding site 1: 5′-GTGGTTCTAGACACCCCCTCCCCCATCATA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGTTCTAGAGGCTCTCTGTGTTTTGGGGT-3′ (reverse) and binding site 2: 5′-GTGGTTCTAGACCTACACAGAAGCAGCGTCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGTTCTAGAGATCAGGGCTCAGGGAATGG-3′ (reverse) (Figure 3b). Using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis, the following primers: binding site 1, 5′-CACAGAGCCTG CCTCA CGCACAGATTACTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAAGTAATCT GTGCGTGAGGCAGGCTCTGTG-3′ (reverse); and binding site 2, 5′-GAGGTCCCAACACGTCACACACACGGCCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGGCCGTGTGTGTGACGTGTTGGGACCTC-3′ (reverse) were used. In the luciferase-based assay, we showed that the miR15a/16 lost their ability to bind to FOXP3 when binding sites 1 and 2 are mutated (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. FOXP3 is a direct target of miR15a/16.

(a) Sequences and introduced mutations of the miR15a and miR16 binding sites. The putative target sites for the miR15a seed sequence were identified by using TargetScan25 and microRNA.org26 software. The interaction between miR15a/16 and FOXP3 was predicted by three algorithms: miranda, PITA and RNA22. Annotation of the FOXP3 3′-UTR showing predicted binding sites of miR15a and miR16, their seed sequences and subsequent introduced mutations. Two sites were identified: binding site 1: 5′-GTGGTTCTAGACACCCCCTCCCCCATCATA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGTTCTAGAGGCTCTCTGTGTTTTGGGGT-3′ (reverse) and; binding site 2: 5′-GTGGTTCTAGACCTACACAGAAGCAGCGTCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGGTTCTAGAGATCAGGGCTCAGGGAATGG-3′ (reverse). Using a Quik-Change site-directed mutagenesis was identified in the following primers: binding site 1, 5′-CACAGAGCCTGCCTCACGCACAGATTACTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAAGTAATCTGTGCGTGAGGCAGGCTCTGTG-3′ (reverse); and binding site 2, 5′-GAGGTCCCAACACGTCACACACACGGCCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGGCCGTGTGTGTGACGTGTTGGGACCTC-3′ (reverse). (b) miR15a/16 directly interact with Foxp3 at binding site 1 and binding site 2. In luciferase-based assay, miR15a/16 showed direct binding interaction with FOXP3 at binding site 1 and binding site 2. When these sites are specifically mutated, mir15a/16 lose their ability to bind to FOXP3. (c) ‘Toggle-switch’ role of miR15a/16 and FOXP3 function. Overexpression of miR15a/16 in Tregs can push their functional differentiation into a more conventional T-cell-like activity. On the other hand, silencing of miR15a/16 pathway in Tcon may lead to an inducible Treg-like function.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that FOXP3 is a direct target of miR15a/16 and we propose that changes in miR15a/16 expression may provide a mechanism for the plasticity of Treg function. Although the precise targets for miR15a/16 in Tregs remain unclear, we have shown that their overexpression leads to a marked reduction in FOXP3 and CTLA4 protein expression in CB Tregs. As FOXP3 is essential for the suppressive function of Tregs,7,8 the observation that FOXP3/CTLA4 protein expression and the Treg suppressive function are decreased on overexpression of miR15a/16 provides evidence that miR15a/16 likely has an impact Treg activity by engaging with FOXP3. Our conclusion is substantiated by identification of specific binding sites utilized by miR15a and miR16 to engage the FOXP3 gene as shown by the luciferase assay, where mutation of these binding sites disrupts such engagement. Although we appreciate the limitations of our in vitro assays and the possibility of generating non-physiological levels of overexpression, our findings nonetheless provide the first direct evidence of involvement of the miR15a/16 pathway in Treg function. Furthermore, the reversal of the demethylation profile of the Treg-specific demethylated region by miR15a/16 overexpression provides the unique possibility of crosstalk between miR15a/16 and the DNA methylation machinery in Tregs. Further, there are accumulating data that some miRNAs target, directly or indirectly, effectors of the epigenetic machinery such as DNA methyl transferases and methyl CpG binding protein 2.32–35 It is therefore possible that miR15a/16 may additionally regulate Treg methylation, FOXP3 expression and ultimately the suppressive function of the Treg. In humans, miR-15a and miR-16 are clustered within 0.5 kb at chromosome position 13q14 and even though we were not able to demonstrate any additive effect of manipulating these miRNAs, the overall impact of individual knockdown and overexpression experiments showed consistent outcomes on the functional properties of Tregs and Tcons.

Although the prime focus of this study has been FOXP3, another potential target for miR15a/16 is CTLA4. CTLA4 is one of the FOXP3-dependent amplified genes in Treg cells and may act in a cellintrinsic manner to restrict the activation of Tcon, as well as being implicated in the regulation of Treg cell-mediated suppression function.36,37 In addition, TGF-β-mediated induction of FOXP3 in vitro is associated with the expression of CTLA4.38 As CTLA4 expression was decreased when miR15a/16 were overexpressed Tregs, this provides another potential mechanism by which miR15a/16 may exert their downstream effects.

To validate the importance of miR15a/16 in the characterization of suppressive function of Tregs, we demonstrated that the silencing of miR15a/16 in Tcons led to the increased expression of FOXP3/CTLA4, which provided Tcons with Treg-like suppressive activity. As FOXP3 is a target of miR15a/16, it is possible that knockdown of miR15a/16 may have an effect at the level of gene expression. Our findings are consistent with a study reporting that the retroviral transfer of the FOXP3 gene into activated peripheral Tcon (CD4+CD25−) also confers a Treg-like suppressor activity.7,8 Furthermore, we propose that miR15a/16 knockdown in Tcons leads to induction of FOXP3 gene, which in turn confers on them suppressive function as demonstrated in the MLR suppression assay in Figure 2e.

We propose a ‘toggle-switch’-like role of miR15a/16 that can be possibly exploited to manipulate the Treg/Tcon axis (Figure 3c) so that the overexpression of miR15a/16 in Tregs can push their activity more to that of a Tcon. Alternatively, silencing of miR15a/16 pathway in Tcon may lead to the induction of Treg-like activity. A better understanding of the impact of miR15a/16 manipulation in in vivo models is needed before the full potential of a process able to manipulate and exploit the ‘switch’ between Treg and Tcon activities in a clinical setting can be fully realized.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The funding for this work was provided by institutional funds

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

XL designed and performed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. SST designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data. TS designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data. LD’A designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data. MYS designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data. SNR designed and performed research. HY designed and performed research and wrote the manuscript. EY designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. NS designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data. HoY designed and performed research. MK designed and performed research. GG-M designed and performed research, contributed vital new reagents and wrote the manuscript. IMcN analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. Katy Rezvani analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. GAC designed and performed research, contributed vital new reagents, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. EJS designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. SP designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Bone Marrow Transplantation website (http://www.nature.com/bmt)

REFERENCES

- 1.Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells: history and perspective. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;707:3–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-979-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunstein CG, Miller JS, Cao Q, McKenna DH, Hippen KL, Curtsinger J, et al. Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood: safety profile and detection kinetics. Blood. 2011;117:1061–1070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-293795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Terenzi A, Castellino F, Bonifacio E, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor PA, Lees CJ, Blazar BR. The infusion of ex vivo activated and expanded CD4 (+)CD25(+) immune regulatory cells inhibits graft-versus-host disease lethality. Blood. 2002;99:3493–3499. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edinger M, Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Drago K, Fathman CG, Strober S, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hippen KL, Harker-Murray P, Porter SB, Merkel SC, Londer A, Taylor DK, et al. Umbilical cord blood regulatory T-cell expansion and functional effects of tumor necrosis factor receptor family members OX40 and 4-1BB expressed on artificial antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2008;112:2847–2857. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Josefowicz SZ, Kas A, Chu TT, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Genome-wide analysis of Foxp3 target genes in developing and mature regulatory T cells. Nature. 2007;445:936–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liston A, Lu LF, O'Carroll D, Tarakhovsky A, Rudensky AY. Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway safeguards regulatory T cell function. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1993–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou X, Jeker LT, Fife BT, Zhu S, Anderson MS, McManus MT, et al. Selective miRNA disruption in T reg cells leads to uncontrolled autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1983–1991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranganathan P, Heaphy CE, Costinean S, Stauffer N, Na C, Hamadani M, et al. Regulation of acute graft-versus-host disease by microRNA-155. Blood. 2012;119:4786–4797. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouas R, Fayyad-Kazan H, El Zein N, Lewalle P, Rothe F, Simion A, et al. Human natural Treg microRNA signature: role of microRNA-31 and microRNA-21 in FOXP3 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1608–1618. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu LF, Thai TH, Calado DP, Chaudhry A, Kubo M, Tanaka K, et al. Foxp3-dependent microRNA155 confers competitive fitness to regulatory T cells by targeting SOCS1 protein. Immunity. 2009;30:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadlon TJ, Wilkinson BG, Pederson S, Brown CY, Bresatz S, Gargett T, et al. Genome-wide identification of human FOXP3 target genes in natural regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:1071–1081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson IC, Mavrangelos C, Bird DR, Bresatz-Atkins S, Eastaff-Leung NG, Grose RH, et al. PI16 is expressed by a subset of human memory Treg with enhanced migration to CCL17 and CCL20. Cell Immunol. 2012;275:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parmar S, Robinson SN, Komanduri KSt, John L, Decker W, Xing D, et al. Ex vivo expanded umbilical cord blood T cells maintain naive phenotype and TCR diversity. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:149–157. doi: 10.1080/14653240600620812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parmar SLS, Tung SS, Robinson SN, Rodriguez G, Cooper LJN, Yang H, et al. Third-party umbilical cord blood–derived regulatory T cells prevent xenogenic graft-versus-host disease. Cytotherapy. 2013;16:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato T, Deiwick A, Raddatz G, Koyama K, Schlitt HJ. Interactions of allogeneic human mononuclear cells in the two-way mixed leucocyte culture (MLC): influence of cell numbers, subpopulations and cyclosporin. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:301–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy V, Hill GR, Pan L, Gerbitz A, Teshima T, Brinson Y, et al. G-CSF modulates cytokine profile of dendritic cells and decreases acute graft-versus-host disease through effects on the donor rather than the recipient. Transplantation. 2000;69:691–693. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002270-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C (T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diegelmann J, Olszak T, Goke B, Blumberg RS, Brand S. A novel role for interleukin-27 (IL-27) as mediator of intestinal epithelial barrier protection mediated via differential signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) protein signaling and induction of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:286–298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.294355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonci D, Coppola V, Musumeci M, Addario A, Giuffrida R, Memeo L, et al. The miR-15a-miR-16-1 cluster controls prostate cancer by targeting multiple oncogenic activities. Nat Med. 2008;14:1271–1277. doi: 10.1038/nm.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabbri M, Bottoni A, Shimizu M, Spizzo R, Nicoloso MS, Rossi S, et al. Association of a microRNA/TP53 feedback circuitry with pathogenesis and outcome of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA. 2011;305:59–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–D153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbs GM, Roelants K, O'Bryan MK. The CAP superfamily: cysteine-rich secretory proteins, antigen 5, and pathogenesis-related 1 proteins--roles in reproduction, cancer, and immune defense. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:865–897. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diez-Roux G, Banfi S, Sultan M, Geffers L, Anand S, Rozado D, et al. A high-resolution anatomical atlas of the transcriptome in the mouse embryo. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye J, Huang X, Hsueh EC, Zhang Q, Ma C, Zhang Y, et al. Human regulatory T cells induce T-lymphocyte senescence. Blood. 2012;120:2021–2031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawant DV, Wu H, Kaplan MH, Dent AL. The Bcl6 target gene microRNA-21 promotes Th2 differentiation by a T cell intrinsic pathway. Mol Immunol. 2013;54:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron U, Floess S, Wieczorek G, Baumann K, Grutzkau A, Dong J, et al. DNA demethylation in the human FOXP3 locus discriminates regulatory T cells from activated FOXP3(+) conventional T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2378–2389. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balaguer F, Link A, Lozano JJ, Cuatrecasas M, Nagasaka T, Boland CR, et al. Epigenetic silencing of miR-137 is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6609–6618. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabbri M, Garzon R, Cimmino A, Liu Z, Zanesi N, Callegari E, et al. MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyl-transferases 3A and 3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15805–15810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707628104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein ME, Lioy DT, Ma L, Impey S, Mandel G, Goodman RH. Homeostatic regulation of MeCP2 expression by a CREB-induced microRNA. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1513–1514. doi: 10.1038/nn2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varambally S, Cao Q, Mani RS, Shankar S, Wang X, Ateeq B, et al. Genomic loss of microRNA-101 leads to overexpression of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in cancer. Science. 2008;322:1695–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.1165395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bachmann MF, Kohler G, Ecabert B, Mak TW, Kopf M. Cutting edge: lymphoproliferative disease in the absence of CTLA-4 is not T cell autonomous. J Immunol. 1999;163:1128–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng SG, Wang JH, Stohl W, Kim KS, Gray JD, Horwitz DA. TGF-beta requires CTLA-4 early after T cell activation to induce FoxP3 and generate adaptive CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3321–3329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]