Abstract

Standard therapy for malaria in Uganda changed from chloroquine to chloroquine + sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in 2000, and artemether-lumefantrine in 2004, although implementation of each change was slow. Plasmodium falciparum genetic polymorphisms are associated with alterations in drug sensitivity. We followed the prevalence of drug resistance-mediating P. falciparum polymorphisms in 982 samples from Tororo, a region of high transmission intensity, collected from three successive treatment trials conducted during 2003–2012, excluding samples with known recent prior treatment. Considering transporter mutations, prevalence of the mutant pfcrt 76T, pfmdr1 86Y, and pfmdr1 1246Y alleles decreased over time. Considering antifolate mutations, the prevalence of pfdhfr 51I, 59R, and 108N, and pfdhps 437G and 540E were consistently high; pfdhfr 164L and pfdhps 581G were uncommon, but most prevalent during 2008–2010. Our data suggest sequential selective pressures as different treatments were implemented, and they highlight the importance of genetic surveillance as treatment policies change over time.

Introduction

Despite the recent endorsement of malaria elimination as a worldwide goal, the malaria burden has not decreased notably in Uganda, where Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for most episodes of malaria, and millions of cases occur each year.1 Uganda has undergone two recent changes in policy for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria, driven by the development of resistance to older antimalarials.2 In 2000, chloroquine (CQ) was replaced by CQ plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), and in 2004 this regimen was replaced by the artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) artemether-lumefantrine (AL), although implementation of new treatment practices was slow. Alternate ACTs for uncomplicated malaria in Uganda are artesunate-amodiaquine (AS-AQ) and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP). Each ACT consists of a potent and rapid-acting artemisinin and a longer-acting partner drug.3 Leading ACTs have shown outstanding antimalarial efficacy,4,5 but early signs of resistance to artemisinins, manifested as delayed parasite clearance after therapy, have been seen in parts of Southeast Asia,6 and resistance has been seen to most ACT partner drugs.7

Resistance to a number of antimalarial drugs has been linked to genetic polymorphisms in P. falciparum. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in pfcrt and pfmdr1, which encode putative transport proteins, affect responses to multiple drugs. A single mutation, pfcrt 76T, is the key mediator of resistance to CQ and AQ.8 In addition, polymorphisms in pfmdr1, which is homologous to proteins that mediate drug sensitivity in mammalian cells,9 modulate sensitivity of parasites to multiple drugs.10,11 Considering pfmdr1 mutations that are common in Africa, 86Y and 1246Y are associated with decreased sensitivity to CQ and AQ, but wild-type (WT) sequences at the same alleles mediate decreased sensitivity to lumefantrine, mefloquine, and artemisinins.12–14 Another pfmdr1 polymorphism, Y184F, is common, but of uncertain significance, and two others, S1034C and N1042D, are seen in Asia, but rare in Africa.9

In Uganda and many other African countries the prevalence of the key mediator of CQ resistance, pfcrt 76T, increased to saturation levels by the 1990s.15–17 With cessation of CQ use, reduction in the prevalence of pfcrt 76T has been seen. Notably, in Malawi, over 8 years after CQ withdrawal, the prevalence of parasites with pfcrt 76T decreased from 85% to 13%,18 and in 2005 excellent antimalarial efficacy of CQ was shown.19 Decreases in the prevalence of pfcrt 76T have also been seen in eastern Kenya and Zanzibar, although changes have not been as dramatic as in Malawi.20,21 Changes have also been seen in the prevalence of key pfmdr1 genotypes in Kenya, Tanzania, and Zanzibar, with WT N86 and D1246 genotypes increasing over time.11,21–23

The SNPs in folate enzyme genes are associated with decreased sensitivity to antifolate antimalarials such as SP.24 Antifolate resistance develops in a stepwise manner. Parasites containing five mutations, pfdhfr 51I, 59R, and 108N plus pfdhps 437G and 540E, which together mediate clinically relevant resistance, have recently been seen to be common in East Africa and near fixation in Uganda,16,25 where continued selection is presumably caused by continued use of antifolates for intermittent preventive therapy and other uses. However, mutations that mediate a higher level of resistance and are seen elsewhere, notably pfdhfr I164L and pfdhps A581G, are generally uncommon in Africa,26 although some reports have noted increased prevalence in parts of east Africa.27,28 Notably, pfdhfr 164L was reported in 14% of P. falciparum isolates collected from symptomatic patients in southwestern Uganda in 2005.29

Considering the impacts of parasite polymorphisms in both transporter and folate genes on drug sensitivity and changing malaria treatment practices over time, it was of interest to examine the prevalence of key SNPs in Uganda over time. We therefore examined sequences of interest in P. falciparum isolates from patients enrolled in drug efficacy trials from 2003 to 2012 in a high malaria transmission area of Uganda.

Materials and Methods

Clinical trials.

We analyzed 982 archived P. falciparum isolates obtained from treatment trials in Tororo District. Details of the clinical studies have been published (Table 1).30–33 For the first study, which enrolled patients ≥ 6 months of age with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria from December 2002 to May 2004 and compared the efficacies of CQ+SP, AQ+SP, and AS+AQ,31 we analyzed 198 pretreatment DNA samples collected from September to November 2003 for pfmdr1 and pfdhps 581 polymorphisms, and included data on other polymorphisms that were already published.16 For the second study, which enrolled patients 1–10 years of age that presented with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria from December 2004 to July 2005 and compared the efficacies of AS+AQ, and AL,32 we analyzed 201 pretreatment DNA samples for pfdhfr and pfdhps polymorphisms, and included data on pfcrt and pfmdr1 SNPs that were already published.34 For the third study, a longitudinal trial in which 351 children 4–12 months of age were enrolled and randomized to receive either AL or DP for each episode of uncomplicated malaria,33 we analyzed 584 samples, including 204 from all first episodes of falciparum malaria and 380 from all recurrent episodes presenting 84 or more days after a prior treatment. For this trial, in a subset of samples that were genotyped, < 1% of recurrent infections within 28 days were caused by recrudescence; we anticipate that no infections occurring ≥ 84 days after a prior infection were the result of recrudescence.33,35

Table 1.

Description of trials that provided samples for the molecular study*

| Antimalarial regimens studied | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline study characteristics | CQ+SP vs. AQ+SP vs. AS+AQ† | AL vs. AS+AQ† | AL vs. DP‡ |

| Study period | 2002–04 | 2004–05 | 2007–12 |

| Age at enrollment | ≥ 6 months | 1–10 years | 4–12 months |

| Number of participants | 347 | 403 | 351 |

| Median age (years) | 1.27 | 1.83 | 0.98 |

| Geometric mean parasite density | 18,484/μL | 22,071/μL | 16,349/μL |

| Samples successfully genotyped | 189/198 (95%) | 188/201 (93%) | 561/584 (96%) |

Target gene amplification and mutation analysis.

Parasite DNA was extracted from dried filter paper blood spots using Chelex, as previously described.36 The DNA from control strains 3D7, Dd2, 7G8, FCR3, V1/S, K1, and Peru was obtained from the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center. Genes of interest were amplified, and polymorphisms in pfcrt, pfmdr1, pfdhfr, and pfdhps were analyzed by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, as previously described.37–39 Target sequences were amplified (see Supplemental Table 1 for primers), and PCR products were treated with polymorphism-specific restriction endonucleases (ApoI for pfcrt K76T; AflIII, DraI, and BglII for pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F, and D1246Y, respectively; MluCI, XmnI, BsrI and DraI for pfdhfr N51I, C59R, S108N and I164L, respectively; and AvaII, FokI and BstUI for pfdhps A437G, K540E and A581G, respectively). Reaction products were resolved on 2.5% agarose gels, and electrophoretic band patterns were categorized as WT, mixed, or mutant genotypes by visual inspection of gels and comparison with DNA from control strains.

Data analysis.

Data were entered into a Microsoft (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) access database and exported into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) software 17.0, which was used for analysis. For these analyses, mixed genotypes were grouped with either mutant or WT, as indicated. Graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA). Temporal changes in SNP frequencies were analyzed using logistic regression with date of collection as a continuous or categorical variable, as indicated, to evaluate for trends over time or differences between discrete time periods, respectively. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

We evaluated the prevalence of polymorphisms of interest in pfcrt, pfmdr1, pfdhfr, and pfdhps from P. falciparum isolates collected in three clinical trials, all conducted in Tororo District over the course of a decade during which standard antimalarial treatment in Uganda underwent major changes. To minimize the influence of prior therapies on parasite genetics, samples were collected before treatment in the two older trials, and in the newer longitudinal trial, samples were from first episodes of malaria and from episodes ≥ 84 days since a prior episode. The SNPs of interest were categorized as WT, mixed, or mutant, based on sequences of the reference 3D7 strain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportions of patients infected with Plasmodium falciparum parasites containing polymorphisms in pfcrt, pfmdr1, pfdhfr, and pfdhps*

| Genotype | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2004† | 2005‡ | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| pfcrt K76T | ||||||||

| WT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 13 (17%) |

| Mixed | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 9 (8%) | 12 (16%) |

| Mutant | 79 (99%) | 201 (100%) | 38 (100%) | 144 (98%) | 87 (94%) | 104 (96%) | 102 (92%) | 52 (67%) |

| Pfmdr1 N86Y | ||||||||

| WT | 20 (10%) | 19 (9%) | 12 (32%) | 34 (23%) | 23 (26%) | 48 (44%) | 52 (47%) | 40 (51%) |

| Mixed | 136 (71%) | 76 (38%) | 7 (19%) | 88 (61%) | 27 (30%) | 41 (37%) | 41 (37%) | 32 (41%) |

| Mutant | 36 (19%) | 106 (53%) | 18 (49%) | 23 (16%) | 39 (44%) | 21 (19%) | 18 (16%) | 6 (8%) |

| Pfmdr1 Y184F | ||||||||

| WT | 141 (75%) | 169 (85%) | 25 (68%) | 103 (71%) | 75 (83%) | 41 (37%) | 63 (59%) | 50 (68%) |

| Mixed | 43 (23%) | 28 (14%) | 7 (19%) | 22 (15%) | 6 (7%) | 45 (41%) | 7 (7%) | 4 (6%) |

| Mutant | 3 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 5 (13%) | 20 (14%) | 9 (10%) | 25 (22%) | 36 (34%) | 19 (26%) |

| Pfmdr1 D1246Y | ||||||||

| WT | 3 (2%) | 32 (17%) | 9 (23%) | 35 (24%) | 16 (17%) | 22 (19%) | 22 (20%) | 42 (53%) |

| Mixed | 89 (48%) | 80 (40%) | 12 (31%) | 50 (34%) | 22 (23%) | 55 (50%) | 53 (48%) | 27 (34%) |

| Mutant | 93 (50%) | 86 (43%) | 18 (46%) | 61 (42%) | 58 (60%) | 34 (31%) | 35 (32%) | 10 (13%) |

| Pfdhfr N51I | ||||||||

| WT | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed | 5 (6%) | 5 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Mutant | 75 (94%) | 185 (97%) | 34 (100%) | 144 (99%) | 92 (99%) | 110 (99%) | 109 (100%) | 79 (100%) |

| Pfdhfr C59R | ||||||||

| WT | 24 (7%) | 13 (7%) | 3 (8%) | 4 (3%) | 6 (7%) | 10 (9%) | 5 (4%) | 6 (8%) |

| Mixed | 122 (37%) | 60 (31%) | 1 (3%) | 9 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 12 (11%) | 14 (13%) | 5 (6%) |

| Mutant | 187 (56%) | 117 (62%) | 33 (89%) | 132 (91%) | 84 (90%) | 87 (80%) | 92 (83%) | 65 (86%) |

| Pfdhfr S108N | ||||||||

| WT | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed | 0 | 4 (2%) | 20 (59%) | 29 (23%) | 10 (11%) | 18 (16%) | 10 (9%) | 2 (2%) |

| Mutant | 80 (100%) | 186 (97%) | 14 (41%) | 99 (77%) | 83 (89%) | 92 (83%) | 101 (91%) | 77 (98%) |

| Pfdhfr I164L | ||||||||

| WT | 80 (100%) | 152 (99%) | 34 (100%) | 137 (99%) | 83 (91%) | 98 (88%) | 105 (100%) | 77 (100%) |

| Mixed | 0 | 2 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 7 (8%) | 12 (11%) | 0 | 0 |

| Mutant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Pfdhps A437G | ||||||||

| WT | 5 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Mixed | 48 (14%) | 24 (12%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (5%) |

| Mutant | 280 (84%) | 170 (86%) | 33 (100%) | 142 (98%) | 91 (98%) | 108 (97%) | 108 (98%) | 75 (95%) |

| Pfdhps K540E | ||||||||

| WT | 8 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Mixed | 86 (26%) | 25 (13%) | 0 | 6 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 14 (13%) | 3 (4%) |

| Mutant | 239 (72%) | 165 (86%) | 33 (100%) | 138 (96%) | 89 (96%) | 106 (95%) | 95 (86%) | 76 (96%) |

| Pfdhps A581G | ||||||||

| WT | 193 (100%) | 195 (98%) | 37 (100%) | 129 (88%) | 83 (89%) | 97 (87%) | 95 (88%) | 76 (98%) |

| Mixed | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 17 (11%) | 9 (10%) | 4 (4%) | 9 (8%) | 1 (2%) |

| Mutant | 0 | 2 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 10 (9%) | 4 (4%) | 0 |

WT = wild-type.

Data shown are numbers (proportions in parentheses) of samples with each genotype.

Data from 2003–2004 (samples obtained from November 2003 to May, 2004) are combined.

Data obtained from December 2004 to July 2005 are included for 2005; 98% of samples from this trial were collected in 2005.

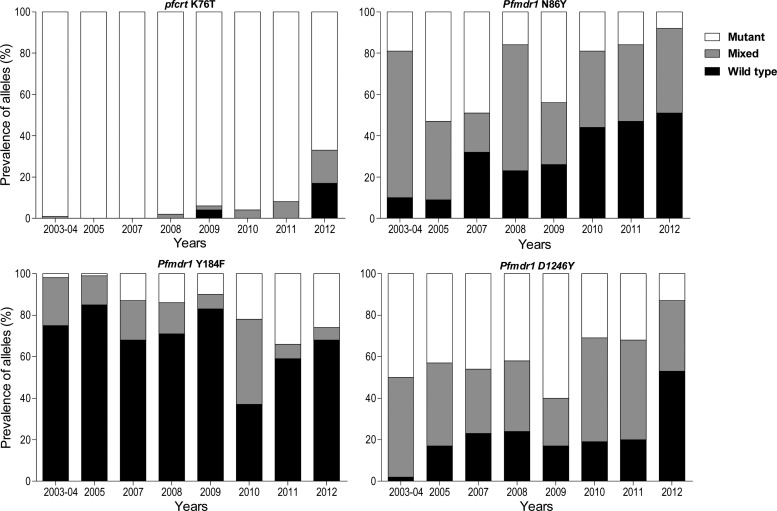

For pfcrt K76T, the prevalence of mutant parasites was nearly 100% throughout the early years of observation, consistent with other reports from Uganda,15,16,40,41 and likely due in part to widespread use of chloroquine even after the national treatment policy changed in 2004. The prevalence of WT and mixed K76T genotypes increased modestly from 2008 to 2011, and then a marked change was seen in 2012, with 16% mixed and 17% pure WT genotypes seen (Figure 1). Considering the period from 2007 to 2012, the probability of being infected with a WT or mixed (versus mutant) genotype increased significantly over time (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of polymorphisms over time at codon 76 of pfcrt, and codons 86, 184, and 1246 of pfmdr1.

For pfmdr1, the N86Y, Y184F, and D1246Y alleles were highly polymorphic throughout the period of observation. Although results varied from year to year, clear patterns were seen at the N86Y and D1246Y alleles, with increasing prevalence of WT genotypes over time (Figure 1). At Y184F, increasing prevalence of the mutant genotype was seen. Considering the entire period of observation, statistically significant increases in the probability of infection with a WT or mixed genotype for the N86Y (P < 0.001) and D1246Y (P < 0.001) alleles, and with a mutant (versus mixed or WT) genotype for the Y184F allele (P < 0.001) were seen. Prevalence of the 86Y/Y184/1246Y haplotype decreased markedly over time, with increases in haplotypes including WT sequences at positions 86 and 1246 (Table 3). Based on known selective effects of antimalarial drugs that have been commonly used in Uganda, these results suggest decreasing selective pressure of CQ and/or increasing selective pressure of AL over time in Uganda.

Table 3.

Pfmdr1 haplotype distribution over time

| Year | 86Y/1246Y | N86/D1246 | N86/184F/D1246 | 86Y/Y184/1246Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 15/180 (8%) | 0/180 (0%) | 0/197 (0%) | 70/197 (36%) |

| 2005 | 70/198 (35%) | 15/198 (8%) | 2/197 (1%) | 67/197 (34%) |

| 2007 | 13/37 (35%) | 7/37 (19%) | 1/37 (3%) | 12/37 (32%) |

| 2008 | 13/144 (9%) | 19/144 (13%) | 8/150 (5%) | 11/150 (7%) |

| 2009 | 24/89 (30%) | 9/89 (10%) | 3/87 (4%) | 23/87 (26%) |

| 2010 | 9/110 (8%) | 14/110 (13%) | 0/110 (0%) | 3/110 (3%) |

| 2011 | 9/110 (8%) | 10/110 (9%) | 4/105 (4%) | 5/105 (5%) |

| 2012 | 2/78 (3%) | 22/78 (28%) | 7/73 (10%) | 0/73 (0%) |

Data from 2003–2004 and late 2004–2005 were combined as explained in Table 2. The results shown represent the proportion and percentage of each haplotype found among all those with successful analysis for each allele, considering only results with pure wild-type (WT) or mutant genotypes.

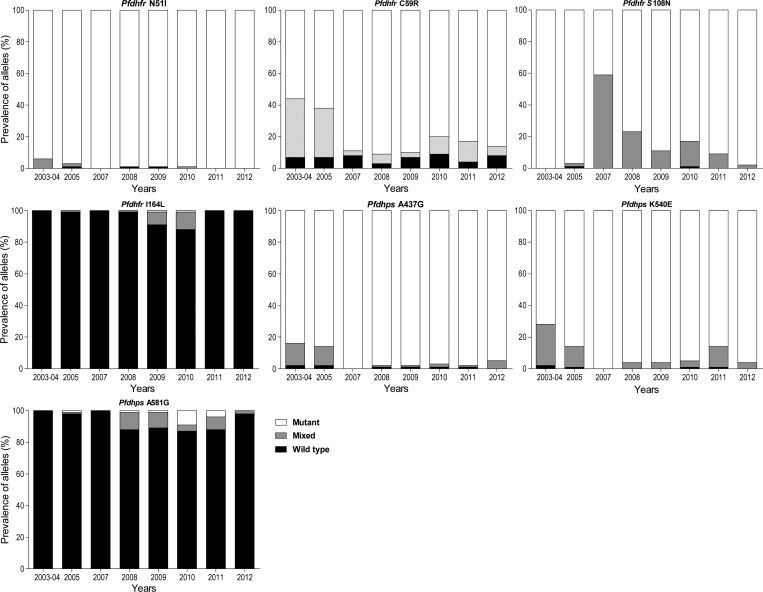

For mutations associated with resistance to antifolate antimalarials, five well-described mutations in pfdhfr (N51I, C59R, S108N) and pfdhps (A437G, K540E) were all very common throughout the period of observation (Table 2). Considering uncommon genotypes associated with high-level resistance, both pfdhfr 164L and pfdhps 581G were nearly absent early and late in our study, but more common from 2008 to 2010, with peak prevalence of mixed or mutant sequences at pfdhfr 164 at 9–12% in 2009 and 2010, and at pfdhps position 581 at 11–13% in 2008–2011 (Figure 2). The prevalence of the pfdhfr 164 WT genotype was significantly lower in 2009–10 than in other years (P < 0.001) and the prevalence of the pfdhps 581 WT genotype was significantly lower in 2009–12 than in earlier years (P = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of polymorphisms over time in the indicated alleles of pfdhfr and pfdhfr.

Discussion

We examined changes in the prevalence of P. falciparum polymorphisms associated with drug resistance over a decade during which standard antimalarial treatment in Uganda underwent major changes. All evaluated samples were from the same region of Uganda, and from patients without known recent antimalarial treatment before analysis, limiting selective pressure from prior therapy, and thus providing a reasonable assessment of the prevalence of polymorphisms in parasites circulating in Tororo each year. Important changes were seen in the prevalence of a number of SNPs of interest. For pfcrt K76T, which is known to mediate CQ and AQ resistance, WT parasites were nearly absent in the early years of observation, but these became much more common by 2012. For pfmdr1 N86Y and D1246Y, which impact upon sensitivity to multiple drugs, the prevalence of WT alleles increased steadily over time. For polymorphisms in pfdhfr and pfdhps, which mediate resistance to antifolates, five well-described mutations remained common over time, and mutations at two additional alleles associated with high level resistance showed modest prevalence only from 2008–11. Overall, the identified changes in prevalence seem to be consistent with differing selective drug pressures caused by changes in treatment practices in Uganda over time.

How can we explain the observed changes in the prevalence of P. falciparum drug resistance-mediating SNPs in Uganda over time? The mutant pfcrt 76T genotype persisted in Uganda at high (> 90%) prevalence levels through 2011, long after it had decreased elsewhere in East Africa. For example, the prevalence of the 76T genotype was 63% in eastern Kenya in 2008,22 63% in Zanzibar in 2010,21 and 32% in western Kenya in 2011.11 The persistence of the mutant pfcrt 76T genotype in Uganda suggests that continued selective pressure from CQ persisted long after the national treatment policy changed in 2004, when the standard therapy for malaria was changed from CQ + SP to AL. The CQ remains available in Uganda, and in fact it continues to be recommended for regular chemoprophylaxis in children with sickle cell disease.42 Very recently, the prevalence of parasites with the CQ-sensitive pfcrt K76 genotype increased markedly in Tororo, suggesting a decrease in community use of CQ.

For pfmdr1, the prevalence of mutant 86Y and 1246Y genotypes gradually decreased in Uganda from 2003 to 2012. These changes were likely due both to decreased use of CQ and gradual establishment of AL as the standard antimalarial drug in Tororo, because both decreasing CQ exposure and increased lumefantrine exposure will select for WT sequences at these alleles.3,43,44 In other parts of East Africa, the prevalence of pfmdr1 N86 and D1246 have been observed to increase following widespread use of ACTs.11,23,45 Of note, pfmdr1 WT genotypes have been associated with decreased sensitivity to lumefantrine.46,47 Taken together, available data suggest that, although the efficacies of leading ACTs appear to remain excellent, parasites in East Africa are undergoing changes rendering them less sensitive to lumefantrine. Continued selection may lead to highly resistant parasites, jeopardizing the antimalarial efficacy of AL, the first-line therapy for malaria in Uganda and surrounding countries.

Considering changes in the prevalence of SNPs that mediate antifolate resistance, five well-characterized mutations in pfdhfr (N51I, C59R, and S108N) and pfdhps (A437G, K540E) were very common in Tororo throughout the last 10 years. These data suggest continued strong selective pressure despite the withdrawal of SP from treatment guidelines in 2004. Of interest was whether selection of additional polymorphisms in pfdhfr or pfdhps was seen, in particular the pfdhfr 164L and pfdhps 581G mutations that are associated with high-level antifolate resistance.24 In Kenya, an increase in prevalence of the five common mutations, and also emergence of dhps 581G, was reported over a 13-year period of observation,48 despite withdrawal of SP for the treatment of malaria in 2006. Other reports have noted a fairly high prevalence of SNPs that mediate high-level antifolate resistance in some settings, including a pfdhfr 164L prevalence of 14% in P. falciparum from an area of Uganda with low malaria transmission intensity29 and modest prevalence of both the pfdhfr 164L and pfdhps 581G mutations in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected Ugandan children receiving regular trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis.49,50 In other recent studies from East Africa, the prevalence of pfdhps 581G was > 50% in samples from eastern Kenya and Tanzania.27,28 In our results from Tororo, the pfdhfr 164L and pfdhps 581G mutations were very uncommon, except for increased prevalence from 2008 to 2011. Reasons for continued antifolate selective pressure likely include continued use of SP to treat malaria, treatment of bacterial infections with antifolates, use of SP in intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women, which remains the World Health Organization (WHO) policy, and widespread use of another antifolate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in HIV-infected individuals. The decreased prevalence of both the pfdhfr 164L and pfdhps 581G mutations in Tororo in the most recent years suggests decreasing use of SP to treat malaria quite recently and fitness disadvantages of genotypes that mediate the highest levels of antifolate resistance; these fitness disadvantages may most effectively prevent selection in areas with very high malaria transmission intensity, such as Tororo.7

Our study had some limitations. First, samples were collected from studies with different designs. In the two older treatment efficacy trials subjects were enrolled and samples obtained immediately before treatment of malaria, but information on prior treatment before enrollment was necessarily limited. The more recent trial was a longitudinal trial in which children were treated with the same regimen, either AL or DP, for every episode of malaria over 5 years. In this trial, to limit impacts of prior treatments on infecting parasites, we studied only parasites causing first infections in the study and those without prior therapy within 84 days. Another limitation was that data were derived from a combination of older and recent assays, and for the oldest trial different numbers of samples were assessed for different alleles. Although we used the same RFLP methods for all assessments, assays done at different points in time after sample collection may have led to somewhat different results, in particular in the case of minority strains within populations.

Despite some limitations, our data offer the best available description of changes in the prevalence of key resistance-mediating P. falciparum polymorphisms over time in Uganda. Indeed, parasites changed notably from 2003 to 2012. Our results suggest continued use of CQ and SP well beyond the establishment of AL as the national treatment regimen in 2004. However, our most recent results suggest decreasing selective pressure from both CQ and SP, with increasing prevalence of the pfcrt K76 WT genotype and loss of folate gene polymorphisms associated with high level resistance. In addition, increasing prevalence of the WT pfmdr1 N86 and D1246 alleles has been seen over time. These results are reassuring, in suggesting that recommended use of AL to treat uncomplicated malaria has increased. However, the results also raise the concern that continued heavy use of AL may select for parasites with decreased lumefantrine sensitivity, potentially leading to AL treatment failures. Continued surveillance of P. falciparum polymorphisms will be important, both to provide insight into the evolution of drug resistance and to offer feedback regarding national treatment practices. In future surveillance higher throughput assays,51 and deep sequencing methods to identify minority strains,52 may improve our ability to assess changes in allele prevalence over time.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants in all the clinical trials that provided samples for our analyses, the parents or guardians of study children, and clinical and laboratory personnel for each trial.

Disclaimer: The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was funded by an International Center of Excellence in Malaria Research grant (AI089674) and a Fogarty International Center training grant (TW007375), both from the National Institutes of Health. Some study samples were from a trial supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; and Cooperative Agreement U62P024421 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; and the Global AIDS Program. The funders were not involved with study design, data analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Authors' addresses: George W. Mbogo, Sheila Nankoberanyi, Stephen Tukwasibwe, Samuel L. Nsobya, Emmanuel Arinaitwe, and Moses Kamya, Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda, E-mails: mbggeorge@yahoo.co.uk, nankshila@yahoo.com, stephentukwasibwe@yahoo.com, samnsobya@yahoo.co.uk, earinaitwe@idrc-uganda.org, and mkamya@infocom.co.ug. Frederick N. Baliraine, Le Tourneau University, Longview, TX, E-mail: FredBaliraine@letu.edu. Melissa D. Conrad, Grant Dorsey, Bryan Greenhouse, and Philip J. Rosenthal, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA, E-mails: ConradM@medsfgh.ucsf.edu, gdorsey@medsfgh.ucsf.edu, bgreenhouse@medsfgh.ucsf.edu, and prosenthal@medsfgh.ucsf.edu. Jordan Tappero, Global AIDS Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mail: jtappero@cdc.gov. Sarah G. Staedke, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK, E-mail: sarah.staedke@lshtm.ac.uk.

Reprints requests: Philip J. Rosenthal, Department of Medicine, Box 0811, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143-0811. E-mail: prosenthal@medsfgh.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Yeka A, Gasasira A, Mpimbaza A, Achan J, Nankabirwa J, Nsobya S, Staedke SG, Donnelly MJ, Wabwire-Mangen F, Talisuna A, Dorsey G, Kamya MR, Rosenthal PJ. Malaria in Uganda: challenges to control on the long road to elimination: I. Epidemiology and current control efforts. Acta Trop. 2012;121:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nanyunja M, Nabyonga Orem J, Kato F, Kaggwa M, Katureebe C, Saweka J. Malaria treatment policy change and implementation: the case of Uganda. Malar Res Treat. 2011;2011(683167) doi: 10.4061/2011/683167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nosten F, White NJ. Artemisinin-based combination treatment of falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorsey G, Staedke S, Clark TD, Njama-Meya D, Nzarubara B, Maiteki-Sebuguzi C, Dokomajilar C, Kamya MR, Rosenthal PJ. Combination therapy for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Ugandan children: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2210–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.20.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeka A, Dorsey G, Kamya MR, Talisuna A, Lugemwa M, Rwakimari JB, Staedke SG, Rosenthal PJ, Wabwire-Mangen F, Bukirwa H. Artemether-lumefantrine versus dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for treating uncomplicated malaria: a randomized trial to guide policy in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, Ringwald P, Silamut K, Imwong M, Chotivanich K, Lim P, Herdman T, An SS, Yeung S, Singhasivanon P, Day NP, Lindegardh N, Socheat D, White NJ. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenthal PJ. The interplay between drug resistance and fitness in malaria parasites. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:1025–1038. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fidock DA, Nomura T, Talley AK, Cooper RA, Dzekunov SM, Ferdig MT, Ursos LM, Sidhu AB, Naude B, Deitsch KW, Su XZ, Wootton JC, Roepe PD, Wellems TE. Mutations in the P. falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol Cell. 2000;6:861–871. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valderramos SG, Fidock DA. Transporters involved in resistance to antimalarial drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mwai L, Diriye A, Masseno V, Muriithi S, Feltwell T, Musyoki J, Lemieux J, Feller A, Mair GR, Marsh K, Newbold C, Nzila A, Carret CK. Genome wide adaptations of Plasmodium falciparum in response to lumefantrine selective drug pressure. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eyase FL, Akala HM, Ingasia L, Cheruiyot A, Omondi A, Okudo C, Juma D, Yeda R, Andagalu B, Wanja E, Kamau E, Schnabel D, Bulimo W, Waters NC, Walsh DS, Johnson JD. The role of Pfmdr1 and Pfcrt in changing chloroquine, amodiaquine, mefloquine and lumefantrine susceptibility in western-Kenya P. falciparum samples during 2008–2011. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nsobya SL, Kiggundu M, Nanyunja S, Joloba M, Greenhouse B, Rosenthal PJ. In vitro sensitivities of Plasmodium falciparum to different antimalarial drugs in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1200–1206. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01412-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickard AL, Wongsrichanalai C, Purfield A, Kamwendo D, Emery K, Zalewski C, Kawamoto F, Miller RS, Meshnick SR. Resistance to antimalarials in southeast Asia and genetic polymorphisms in pfmdr1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2418–2423. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2418-2423.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodrow CJ, Krishna S. Antimalarial drugs: recent advances in molecular determinants of resistance and their clinical significance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1586–1596. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6071-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorsey G, Kamya MR, Singh A, Rosenthal PJ. Polymorphisms in the Plasmodium falciparum pfcrt and pfmdr-1 genes and clinical response to chloroquine in Kampala, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1417–1420. doi: 10.1086/319865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis D, Nsobya SL, Talisuna A, Yeka A, Kamya MR, Machekano R, Dokomajilar C, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G. Geographic differences in antimalarial drug efficacy in Uganda are explained by differences in endemicity and not by known molecular markers of drug resistance. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:978–986. doi: 10.1086/500951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyosiimire-Lugemwa J, Nalunkuma-Kazibwe AJ, Mujuzi G, Mulindwa H, Talisuna A, Egwang TG. The Lys-76-Thr mutation in PfCRT and chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kublin JG, Cortese JF, Njunju EM, Mukadam RA, Wirima JJ, Kazembe PN, Djimde AA, Kouriba B, Taylor TE, Plowe CV. Reemergence of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum malaria after cessation of chloroquine use in Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1870–1875. doi: 10.1086/375419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laufer MK, Thesing PC, Eddington ND, Masonga R, Dzinjalamala FK, Takala SL, Taylor TE, Plowe CV. Return of chloroquine antimalarial efficacy in Malawi. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1959–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mwai L, Ochong E, Abdirahman A, Kiara SM, Ward S, Kokwaro G, Sasi P, Marsh K, Borrmann S, Mackinnon M, Nzila A. Chloroquine resistance before and after its withdrawal in Kenya. Malar J. 2009;8:106. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Froberg G, Jornhagen L, Morris U, Shakely D, Msellem MI, Gil JP, Bjorkman A, Martensson A. Decreased prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance markers to amodiaquine despite its wide scale use as ACT partner drug in Zanzibar. Malar J. 2012;11:321. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mang'era CM, Mbai FN, Omedo IA, Mireji PO, Omar SA. Changes in genotypes of Plasmodium falciparum human malaria parasite following withdrawal of chloroquine in Tiwi, Kenya. Acta Trop. 2012;123:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malmberg M, Ngasala B, Ferreira PE, Larsson E, Jovel I, Hjalmarsson A, Petzold M, Premji Z, Gil JP, Bjorkman A, Martensson A. Temporal trends of molecular markers associated with artemether-lumefantrine tolerance/resistance in Bagamoyo district, Tanzania. Malar J. 2013;12:103. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregson A, Plowe CV. Mechanisms of resistance of malaria parasites to antifolates. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:117–145. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorsey G, Dokomajilar C, Kiggundu M, Staedke SG, Kamya MR, Rosenthal PJ. Principal role of dihydropteroate synthase mutations in mediating resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in single-drug and combination therapy of uncomplicated malaria in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:758–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nzila A, Ochong E, Nduati E, Gilbert K, Winstanley P, Ward S, Marsh K. Why has the dihydrofolate reductase 164 mutation not consistently been found in Africa yet? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gesase S, Gosling RD, Hashim R, Ord R, Naidoo I, Madebe R, Mosha JF, Joho A, Mandia V, Mrema H, Mapunda E, Savael Z, Lemnge M, Mosha FW, Greenwood B, Roper C, Chandramohan D. High resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine in northern Tanzania and the emergence of dhps resistance mutation at Codon 581. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spalding MD, Eyase FL, Akala HM, Bedno SA, Prigge ST, Coldren RL, Moss WJ, Waters NC. Increased prevalence of the pfdhfr/phdhps quintuple mutant and rapid emergence of pfdhps resistance mutations at codons 581 and 613 in Kisumu, Kenya. Malar J. 2010;9:338. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch C, Pearce R, Pota H, Cox J, Abeku TA, Rwakimari J, Naidoo I, Tibenderana J, Roper C. Emergence of a dhfr mutation conferring high-level drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum populations from southwest Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1598–1604. doi: 10.1086/587845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeka A, Banek K, Bakyaita N, Staedke SG, Kamya MR, Talisuna A, Kironde F, Nsobya SL, Kilian A, Slater M, Reingold A, Rosenthal PJ, Wabwire-Mangen F, Dorsey G. Artemisinin versus nonartemisinin combination therapy for uncomplicated malaria: randomized clinical trials from four sites in Uganda. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakyaita N, Dorsey G, Yeka A, Banek K, Staedke SG, Kamya MR, Talisuna A, Kironde F, Nsobya S, Kilian A, Reingold A, Rosenthal PJ, Wabwire-Mangen F. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine plus chloroquine or amodiaquine for uncomplicated falciparum malaria: a randomized, multisite trial to guide national policy in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:573–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bukirwa H, Yeka A, Kamya MR, Talisuna A, Banek K, Bakyaita N, Rwakimari JB, Rosenthal PJ, Wabwire-Mangen F, Dorsey G, Staedke SG. Artemisinin combination therapies for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Uganda. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arinaitwe E, Sandison TG, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Homsy J, Kalamya J, Kamya MR, Vora N, Greenhouse B, Rosenthal PJ, Tappero J, Dorsey G. Artemether-lumefantrine versus dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for falciparum malaria: a longitudinal, randomized trial in young Ugandan children. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1629–1637. doi: 10.1086/647946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nsobya SL, Dokomajilar C, Joloba M, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. Resistance-mediating Plasmodium falciparum pfcrt and pfmdr1 alleles after treatment with artesunate-amodiaquine in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3023–3025. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conrad MD, LeClair N, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Bigira V, Muhindo M, Kamya MR, Tappero JW, Greenhouse B, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. Comparative impacts over 5 years of artemisinin-based combination therapies on P. falciparum polymorphisms that modulate drug sensitivity in Ugandan children. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu141. First published online March 8, 2014, doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plowe CV, Djimde A, Bouare M, Doumbo O, Wellems TE. Pyrimethamine and proguanil resistance-conferring mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase: polymerase chain reaction methods for surveillance in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:565–568. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Djimde A, Doumbo OK, Cortese JF, Kayentao K, Doumbo S, Diourte Y, Dicko A, Su XZ, Nomura T, Fidock DA, Wellems TE, Plowe CV, Coulibaly D. A molecular marker for chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:257–263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duraisingh MT, Curtis J, Warhurst DC. Plasmodium falciparum: detection of polymorphisms in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase genes by PCR and restriction digestion. Exp Parasitol. 1998;89:1–8. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duraisingh MT, Jones P, Sambou I, von Seidlein L, Pinder M, Warhurst DC. The tyrosine-86 allele of the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with increased sensitivity to the anti-malarials mefloquine and artemisinin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;108:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baliraine FN, Rosenthal PJ. Prolonged selection of pfmdr1 polymorphisms after treatment of falciparum malaria with artemether-lumefantrine in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1120–1124. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamugisha E, Jing S, Minde M, Kataraihya J, Kongola G, Kironde F, Swedberg G. Efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine in treatment of malaria among under-fives and prevalence of drug resistance markers in Igombe-Mwanza, north-western Tanzania. Malar J. 2012;11:58. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakibuuka V, Ndeezi G, Nakiboneka D, Ndugwa CM, Tumwine JK. Presumptive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine versus weekly chloroquine for malaria prophylaxis in children with sickle cell anemia in Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. Malar J. 2009;8:237. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dokomajilar C, Nsobya SL, Greenhouse B, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G. Selection of Plasmodium falciparum pfmdr1 alleles following therapy with artemether-lumefantrine in an area of Uganda where malaria is highly endemic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1893–1895. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1893-1895.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humphreys GS, Merinopoulos I, Ahmed J, Whitty CJ, Mutabingwa TK, Sutherland CJ, Hallett RL. Amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine select distinct alleles of the Plasmodium falciparum mdr1 gene in Tanzanian children treated for uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:991–997. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00875-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomsen TT, Ishengoma DS, Mmbando BP, Lusingu JP, Vestergaard LS, Theander TG, Lemnge MM, Bygbjerg IC, Alifrangis M. Prevalence of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance gene (Pfmdr-1) in Korogwe District in Tanzania before and after introduction of artemisinin-based combination therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:979–983. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mwai L, Kiara SM, Abdirahman A, Pole L, Rippert A, Diriye A, Bull P, Marsh K, Borrmann S, Nzila A. In vitro activities of piperaquine, lumefantrine, and dihydroartemisinin in Kenyan Plasmodium falciparum isolates and polymorphisms in pfcrt and pfmdr1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5069–5073. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00638-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Sowunmi A, Hudson T, O'Neil M, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AM. Selection of Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance gene 1 alleles in asexual stages and gametocytes by artemether-lumefantrine in Nigerian children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:888–895. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00968-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iriemenam NC, Shah M, Gatei W, van Eijk AM, Ayisi J, Kariuki S, Vanden Eng J, Owino SO, Lal AA, Omosun YO, Otieno K, Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nahlen B, Moore J, Hamel MJ, Ouma P, Slutsker L, Shi YP. Temporal trends of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) drug-resistance molecular markers in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from pregnant women in western Kenya. Malar J. 2012;11:134. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gasasira AF, Kamya MR, Ochong EO, Vora N, Achan J, Charlebois E, Ruel T, Kateera F, Meya DN, Havlir D, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G. Effect of trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole on the risk of malaria in HIV-infected Ugandan children living in an area of widespread antifolate resistance. Malar J. 2010;9:177. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandison TG, Homsy J, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Bigira V, Kalamya J, Vora N, Kublin J, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, Tappero JW. Protective efficacy of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis against malaria in HIV exposed children in rural Uganda: a randomized clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d1617. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LeClair NP, Conrad MD, Baliraine FN, Nsanzabana C, Nsobya SL, Rosenthal PJ. Optimization of a ligase detection reaction-fluorescent microsphere assay for characterization of resistance-mediating polymorphisms in African samples of Plasmodium falciparum. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2564–2570. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00904-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor SM, Parobek CM, Aragam N, Ngasala BE, Martensson A, Meshnick SR, Juliano JJ. Pooled deep sequencing of Plasmodium falciparum isolates: an efficient and scalable tool to quantify prevailing malaria drug-resistance genotypes. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1998–2006. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.