Abstract

As a result of global migration, a significant number of people with Trypanosoma cruzi infection now live in the United States, Canada, many countries in Europe, and other non-endemic countries. Trypanosoma cruzi meningoencephalitis is a rare cause of ring-enhancing lesions in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) that can closely mimic central nervous system (CNS) toxoplasmosis. We report a case of CNS Chagas reactivation in an AIDS patient successfully treated with benznidazole and antiretroviral therapy in the United States.

Trypanosoma cruzi meningoencephalitis is a rare cause of ring-enhancing lesions in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) that can closely mimic central nervous system (CNS) toxoplasmosis. Diagnosis is often delayed and mortality is 79–100% despite treatment1,2; to our knowledge, only four cases of T. cruzi meningoencephalitis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients have been reported in the United States.3–6 None of the four patients have survived. We report a case of CNS Chagas reactivation in an AIDS patient successfully treated with benznidazole and antiretroviral therapy in the United States.

A 49-year-old right-handed woman originally from Honduras was admitted to our hospital with a 3-week history of progressive altered mental status, headache, and right-sided weakness. On the day of symptom onset, she presented to an outside hospital and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed two ring-enhancing lesions associated with edema. She was also diagnosed with AIDS (CD4 count of 38 cells/μL and an HIV viral load of 375,000 copies/mL). The patient underwent an MRI-guided biopsy of the left parietal lesion and was diagnosed with cerebral Toxoplasmosis. After 14-days, she was discharged to continue treatment of cerebral toxoplasmosis with sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine; however, she was nonadherent with her medications.

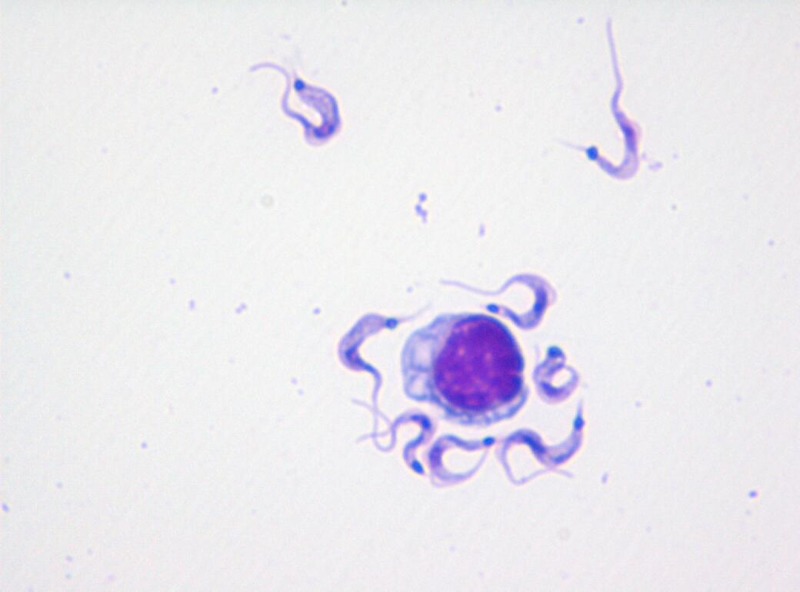

On admission to our hospital, she was afebrile and physical examination was notable for altered mental status and weakness of the right upper and lower extremities (3/5, Medical Research Council scale) without sensory deficit. The MRI of the brain showed worsening ring-enhancing lesions within the right superior frontal gyrus (1.4 × 1.2 cm) and left parietal lobe (2.4 × 2.2 cm) with moderate vasogenic edema and regional mass effect and adjacent leptomeningeal enhancement. She was started on oral sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine, and glucocorticosteroids. On hospital Day 5, the patient had worsening mental status and a computed tomography of the head showed enlargement of the right frontal lesion with increased edema. A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained three white blood cells/μL and one red blood cell/μL. The CSF protein was 78 mg/dL and glucose was 55 mg/dL. The CSF Gram stain was negative for bacteria but Wright-Giemsa stain revealed numerous flagellated parasites consistent with T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Figure 1). Fungal and acid fast bacilli stain and cultures and CSF cryptococcal antigen were negative. Serologic studies were negative for Toxoplasma IgG and IgM but positive for T. cruzi antibody by the indirect fluorescent antibody test and enzyme immunoassay. The CSF and serum polymerase chain reaction studies were positive for T. cruzi and negative for Toxoplasma. Electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were negative for findings to suggest Chagas cardiomyopathy.

Figure 1.

Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Giemsa stain, ×1,000).

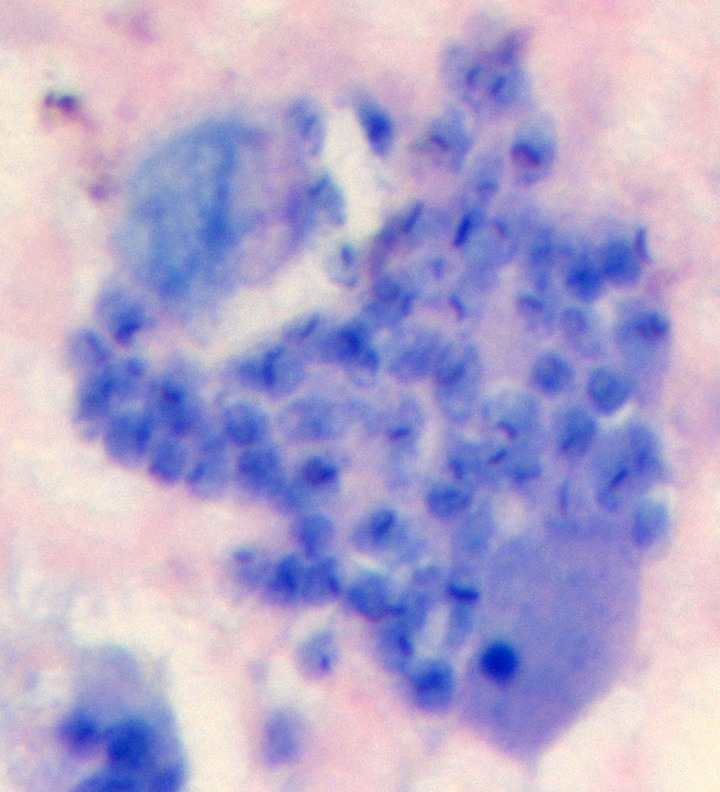

The brain biopsy histopathology slides were obtained from an outside hospital, which revealed numerous intracellular organisms with rod-shaped kinetoplast, consistent with T. cruzi amastigotes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes with rod-shaped kinetoplasts in glial cells (Giemsa stain, ×1,000).

Treatment with benznidazole 5 mg/kg/day was started for Chagasic meningoencephalitis and brain abscesses. Her mental status improved gradually, although her right-sided weakness remained unchanged. Antiretroviral therapy was started 17 days after initiation of antitrypanosomal therapy. Repeat MRI of the brain 2 weeks after treatment showed a decrease in the size of the two lesions and surrounding edema. She completed a 60-day induction therapy. At last follow-up 5 months after initial diagnosis, she was clinically stable without evidence of recurrence and her CD4 count was 359 cells/μL with HIV viral load of 162 copies/ml.

Chagas disease, or American trypanosomiasis, is estimated to affect ∼8–10 million people in the world, primarily in Latin America and the Caribbean.7,8 As a result of global migration, a significant number of people with T. cruzi infection now live in the United States, Canada, many countries in Europe, and other non-endemic countries.9 In the United States alone, it is estimated that ∼0.3 to 1 million people are infected with T. cruzi.10

Reactivation of chronic T. cruzi infection can occur in immunosuppressed patients such as those with hematologic malignancies, organ transplantation, and AIDS. In Chagas-endemic countries, T. cruzi and HIV coinfection rate ranges from 1.3% to 7.1%.11 Although the chronic phase of Chagas disease in non-immunosuppressed patients most commonly manifests as cardiac disease or gastrointestinal dysfunction, the most common manifestations of T. cruzi reactivation in patients with AIDS are CNS lesions and menigoencephalitis. Most of the reported cases have occurred in HIV-infected patients with a CD4 count < 200 cells/μL.1,2,12 T. cruzi reactivation in patients with AIDS can closely mimic cerebral toxoplasmosis clinically and radiographically, thus patients are often misdiagnosed resulting in a delay in appropriate treatment.12

Identification of T. cruzi trypomastigote in CSF is diagnostic of chagasic encephalitis. However, a negative CSF smear does not rule out the disease. In a report of 15 cases from Argentina, CSF direct examination for T. cruzi was positive in 11 of 13 patients.2 A brain biopsy may be necessary when the diagnosis remains unclear. The recommended treatment of CNS Chagas reactivation in HIV patients is benznidazole 5 mg/kg daily divided into two doses for 60–90 days and some authors recommend secondary prophylaxis with benznidazole 5 mg/kg three times per week.12 Nifurtimox is considered an alternative treatment but clinical experience is limited. Immune reconstitution with highly active antiretroviral therapy likely plays an important role in the control of Chagas reactivation but optimal timing for initiation of antiretroviral therapy remains unclear.12 Chagasic menigoencephalitis should be considered in HIV-infected patients with CNS lesions who are from T. cruzi-endemic areas.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Kosuke Yasukawa and Charlene A. Flash, Section of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, E-mails: kosukeyaz@gmail.com and Charlene.Flash@bcm.edu. Shital M. Patel, Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, E-mail: shitalp@bcm.edu. Charles E. Stager and Jerry C. Goodman, Department of Pathology and Immunology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, E-mails: cstager@bcm.edu and jgoodman@bcm.edu. Laila Woc-Colburn, National School of Tropical Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, E-mail: woccolbu@bcm.edu.

References

- 1.Silva N, O'Bryan L, Medeiros E, Holand H, Suleiman J, de Mendonca JS, Patronas N, Reed SG, Klein HG, Masur H, Badaro R. Trypanosoma cruzi meningoencephalitis in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:342–349. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199904010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordova E, Boschi A, Ambrosioni J, Cudos C, Corti M. Reactivation of Chagas disease with central nervous system involvement in HIV-infected patients in Argentina, 1992–2007. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckstein D, Ciferri F, Ruskin J. Chagas' disease: another cause of cerebral mass in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1992;92:429–432. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90275-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoo TW, Mlikotic A, Cornford ME, Beck CK. Concurrent cerebral American trypanosomiasis and toxoplasmosis in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:e30–e34. doi: 10.1086/422456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert N, Mehta B, Walters R, Eron JJ. Chagasic encephalitis as the initial manifestation of AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:941–943. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campo M, Phung MK, Ahmed R, Cantey P, Bishop H, Bell TK, Gardiner C, Arias CA. A woman with HIV infection, brain abscesses, and eosinophilia. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:239–240. doi: 10.1086/649538. 276–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rassi A, Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bern C. Antitrypanosomal therapy for chronic Chagas' disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2527–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1014204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gascon J, Bern C, Pinazo MJ. Chagas disease in Spain, the United States and other non-endemic countries. Acta Trop. 2010;115:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotez PJ, Dumonteil E, Woc-Colburn L, Serpa JA, Bezek S, Edwards MS, Hallmark CJ, Musselwhite LW, Flink BJ, Bottazzi ME. Chagas disease: “the new HIV/AIDS of the Americas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Molina JA. Management of Trypanosoma cruzi coinfection in HIV-positive individuals outside endemic areas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:9–15. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diazgranados CA, Saavedra-Trujillo CH, Mantilla M, Valderrama SL, Alquichire C, Franco-Paredes C. Chagasic encephalitis in HIV patients: common presentation of an evolving epidemiological and clinical association. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:324–330. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70088-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]