Abstract

To improve the health of children and bend the health care cost curve we must integrate the individual and population approaches to health and health care delivery. The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health laid out the continuum for integration of primary care and public health stretching from isolation to merging systems. Integration of the family-centered medical home (FCMH) and home visitation (HV) would promote overall efficiency and effectiveness and help achieve gains in population health through improving the quality of health care delivered, decreasing duplication, reinforcing similar health priorities, decreasing costs, and decreasing health disparities. This paper aims to (1) provide a brief description of the goals and scope of care of the FCMH and HV, (2) outline the need for integration of the FCMH and HV and synergies of integration, (3) apply the IOM’s continuum of integration framework to the FCMH and HV and describe barriers to integration, and (4) use child developmental surveillance and screening as an example of the potential impact of HV-FCMH integration.

Keywords: home visiting, family-centered medical home, patient-centered medical home, primary care

Integration of the Family-Centered Medical Home and Home Visiting Into the Medical Neighborhood

To improve the health of children and bend the health care cost curve we must integrate the traditional silos of health delivery systems.1 Moving the family-centered medical home (FCMH) beyond the office into the community will integrate the personal and population approaches to health and health care delivery and has the potential to optimize each child’s life course trajectory, improve outcomes, and reduce costs.2,3

The future of pediatric care is working in multidisciplinary teams with the shared goal of delivering the right care at the right time and in the right place with the right providers. Although the medical home may be the right place for some services, the patient’s home may be the right place and home visitors the right providers for other services. Continued health disparities bring urgency to integration of these services.4–6 Recent Affordable Care Act investment in home visitation (HV) programs and emphasis on the FCMH combined with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Academic Pediatric Association (APA) endorsement of collaboration between home visitors and primary care providers (PCPs) offer a unique opportunity to integrate and improve services provided to children and families.6–8

This paper aims to (1) provide a brief description of the goals and scope of care of the FCMH and HV, (2) outline the need for integration of the FCMH and HV and synergies of integration, (3) apply the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) continuum of integration framework to the FCMH and HV and describe barriers to integration, and (4) use child developmental surveillance and screening as an example of the potential impact of HV-FCMH integration.

The Family-Centered Medical Home

From an ecological perspective, availability of comprehensive primary care is strongly associated with improved population health.2,9 The FCMH was initially conceived in pediatrics in the 1960s and 1970s as a model for providing comprehensive pediatric care.10 Over the past 3 decades the medical home model has been further refined, defining the medical home as accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective.11,12 The central goal of the FCMH is to facilitate partnerships between patients, families, clinicians, and community resources to improve children’s health, and the joint principles for the FCMH have been widely endorsed.7

There is modest evidence that FCMH models are associated with improved quality of health care in pediatrics, including children with a medical home having fewer unmet health care needs and increased likelihood of receiving preventive care.13–17 Evidence exists for potential cost savings associated with the growth of the medical home model.18 It is hypothesized that an expanded medical home model will further decrease health disparities.19 Ongoing multisite FCMH demonstration projects aim to provide additional evidence regarding the effectiveness of the FCMH model of care.20

The current scope of practice of the FCMH is deeply rooted in the medical model of care, including child health supervision and acute and chronic disease management occurring primarily at an office site. There is increased recognition of the importance of psychosocial issues in child and family health and of a population approach that addresses the social determinants of health. New models of health promotion that move beyond the medical model of care are needed to look beyond the individual patient in the office to managing the health of families and patient populations in the community.3,21

Although traditional models of primary care provide reactive and episodic care during doctor visits, new models require outreach, coordination, and education/empowerment with increasing teamwork provided by multidisciplinary staff including home visitors.22 As FCMHs and hospitals are increasingly being held accountable to population quality measures, interest in home visitation (HV) and community health worker models have increased.23 For instance, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set quality measures that assess well-child visit attendance of a primary care practice’s panel has increased interest in medical home outreach to families and home visitation strategies. Similarly, hospital reimbursement tied to readmission rates has also led some to consider social determinants of health and strategies beyond the health care setting.

Home Visitation

HV is a widely disseminated strategy to promote maternal and child health that is endorsed by state and federal agencies, professional societies, and private foundations.24 HV for at-risk families was developed more than a century ago with goals similar to pediatric primary care, including promoting the health and development of children by developing a longitudinal, supportive, and trusting relationship with families. HV programs involve regular home visits by a paraprofessional or nurse. There are multiple types of HV programs, including maternal, infant and early childhood visiting, targeted visiting for children from at-risk families, and child care and school-based visiting programs.

Models of maternal and infant early home visiting have documented modest evidence that high intensity HV programs can improve child physical and emotional health and development, improve school readiness, and prevent child abuse and neglect.25,26 HV has also been shown to improve the relationship between the family and their primary care clinician.27,28 Furthermore, HV programs have also demonstrated cost savings longitudinally, with the greatest savings in those visited who were at greatest risk.29–31

The scope of practice for evidence-based HV programs is wide and varies depending on the individual goals of the program and what type of provider is performing the home visit. Goals of these programs include improved pregnancy outcomes, prevention of maltreatment and neglect, enhanced parent-child interactions, early identification of delays, and improved developmental trajectories. Community health worker programs have also increased with emphasis on the shared culture of the worker and the family.23

The scope of HV programs has been expanding to address special populations and to include additional goals such as follow-up from hospital discharge, medical visits to children who have special health care needs (eg, asthma care), hospice and palliative care, and environmental evaluations (eg, home lead evaluations). Although some HV programs are based in traditional health care settings such as hospitals and primary care practices, many are operated by state or local public health departments or private companies, often without connection to primary care practices. HV curricula are also used in some pediatric residency training programs as a method to extend the medical home into the community while experientially teaching residents social determinants of health and the role of HV staff.32

Integration: Moving From Isolation to Systems Merging

Why is Integration Important?

The goals of the FCMH model of care and HV programs are fundamentally synergistic. They share goals of promoting the health and development of children, often through trusting longitudinal relationships. Both provide children and their families with social support and anticipatory guidance (eg, development, safety), and linkage to community resources and services. To fully capitalize on these synergies, the systems should be integrated, whenever possible prioritizing the particular strengths of each service and needs of the family.

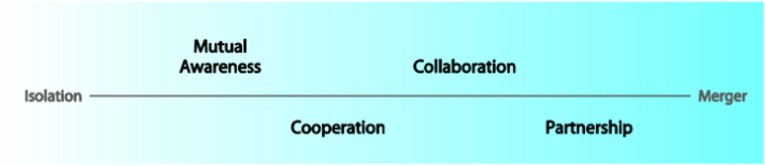

The 2012 IOM report Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health laid out the continuum for integration of primary care and public health.33 The continuum stretches from isolation, mutual awareness, cooperation, collaboration, partnership, and finally to merging systems (Fig 1). Core principles for integration include common goals, involvement of the community in addressing needs, and strong leadership. Leadership is needed to bridge disciplines, services, programs and jurisdictions, sustain integration, and develop collaborative systems for data sharing and evaluation. The time is ripe for planning horizontal integration (ie, merging health services with other sectors such as social and civic sectors) and vertical integration (ie, linking primary, secondary, and tertiary health care services and different health disciplines) for the common goals that HV and the FCMH share.3,34

FIGURE 1.

The Institute of Medicine continuum of integration of primary care and public health.33

Integration of the FCMH and HV could promote overall efficiency and effectiveness and help achieve gains in population health through improving the quality of health care delivered, decreasing duplication, reinforcing similar health priorities, decreasing costs, and decreasing health disparities. The current movement from the FCMH toward the medical neighborhood, which encompasses the FCMH combined with other clinical health services and community and social service organizations at the state and local public health levels, may also serve as a facilitator.35 Because families are more likely to use health services when they reflect the families’ perceived needs, communication between home visitors and FCMH clinicians regarding specific needs is likely to result in more preventive care use and better retention in HV programs.36 Integration may also allow home visitors and medical home providers to better understand patients’ and families’ needs and preferences, and more directly address their concerns.

Evidence for Integration

Different degrees of integration of the FCMH and HV systems have been shown in multiple studies to be effective and to improve health-related outcomes for children.22,23 Hardy and Street found that home visits conducted 2 to 3 weeks before a well-child visit resulted in fewer missed visits, fewer sick and acute care visits, decreased hospitalization, and decreased abuse and neglect.37 Furthermore, at-risk children receiving an intensive HV program in collaboration with a PCP improved involvement with and retention in early intervention programs.38 A program that assigned public health home visitors to work with PCPs in North Carolina resulted in mothers of infants being able to overcome more personal and structural barriers in seeking care for their child.39 Another program in which school-based home visitors collaborated with PCPs in South Carolina resulted in a greater parental understanding and retention of anticipatory guidance and improved satisfaction with care.24

State programs have also been successful in encouraging integration of HV and the FCMH. North Carolina Linkages for Prevention brought together primary care practices and local state health departments in Durham to improve the delivery of preventive care in pediatric primary care practices and implement intensive HV to low-income pregnant women and their infants. Home visitors working in close collaboration with PCPs providing 2 to 4 home visits per month for the first year of life resulted in higher numbers of well-child visits at 12 months and lower likelihood of being seen for injuries and ingestions.40 The REACH-Futures program in Chicago, which uses registered nurses from a community clinic who are teamed with public health trained community health workers for an infant HV program, resulted in improved immunization rates and retention in the primary care clinic.41

Finally, a qualitative study by Nelson et al demonstrated that PCPs and home visitors perceived one of the benefits of integration was improved communication. This included home visitors assisting parental communication with PCPs, home visitors giving PCPs information about families and home environments, home visitors helping the family understand the child’s medical conditions, and home visitors and PCPs reinforcing the specific treatment plan and anticipatory guidance each other gave.36,42–44

Barriers to Integration

As noted, there exists evidence for the feasibility and effectiveness of integrating HV and the FCMH. Understanding the barriers to integration is critical for dissemination and implementation. Integration of HV programs and the FCMH is not an easy task. Many medical home clinicians are not aware of what HV programs operate in their communities and what their scope of practice entails. This results in the inability to fully appreciate and take advantage of each other’s skill. In addition, some PCPs are concerned that the rise of HV may result in more fragmented services for families or may replace some of the services provided in their current practice.43

There are multiple barriers that must be overcome for optimal coordination, communication, and linkage between HV and FCMH. As is acknowledged in the IOM report, the first step of integration is mutual awareness, which is often lacking. FCMH providers and home visitors are often separate organizations that have different oversight and administration. In addition, there are few financial incentives or reimbursement structures to encourage HV and FCMH providers to interact. Significant barriers to communication currently exist, many of which are similar to communication struggles seen between PCPs and subspecialists. These include inconsistent method and timing of communication, inadequate content of communication, and concern for making families intermediaries between home visitor and PCP providers.45

Another common barrier to integration is concern about disclosure of possible confidential information from the PCPs to the home visitors or vice versa.43,46 Families may be apprehensive about disclosing information across services. Furthermore, there is concern that clinicians may be unprepared to act on family issues the home visitor may find in the home, and conversely, that home visitor may not be able to address the issues of PCP concern.37 Finally, the perceived and real-time constraints related to communication and potential disruptions to practice also impede integration efforts.

Measurement

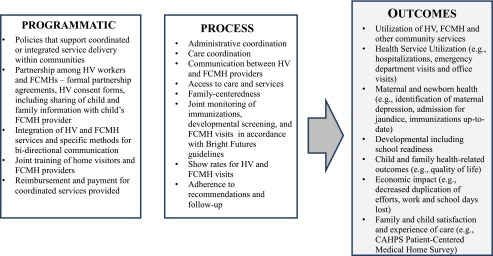

Measuring the integration of HV programs and the FCMH is critical to encourage integration, assess the current state of coordination, plan next steps, and assess effectiveness of interventions to increase collaboration.47 Programmatic measures, process measures, and outcomes must be initially assessed and regularly reassessed (Fig 2).

FIGURE 2.

Measures for assessing the coordination of HV programs and FCMH. Adapted from reference 47.

Example: Integration of Developmental Surveillance and Screening

Although developmental surveillance and screening are part of child health supervision in the FCMH, it is also in the scope of practice for many HV programs. Home visitors potentially have more time with families for developmental surveillance and would be able to observe children in their natural home environment. Without integration, it is possible that PCPs and home visitors may duplicate efforts providing the same surveillance and waste time and money for the PCP, home visitor, and family. There is also the potential to provide inconsistent or conflicting information to families regarding children’s developmental milestones.

Dividing responsibilities regarding developmental assessment between the home visitor and the PCP would likely avoid duplication and allow standardized screening with enhanced monitoring of referrals. Developmental assessment in the home may also be a more effective location for observation and testing, as children might be more comfortable interacting in their home environment rather than having to rely on parental report. As has been done with care coordinators, multiple PCPs could share a home visitor or group of home visitors. A clear process and system for ensuring screening, assessment, referral, and follow-up shared by the FCMH and home visitors could result in improved child developmental outcomes. By dividing responsibilities between the home visitor and PCP, there could be more focused time to address other steps in the surveillance process as well as other important child and family health-related issues.

Methods for Integration of Home Visitation and the Family-Centered Medical Home

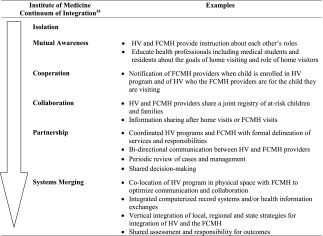

The integration process requires breaking down barriers and establishing new methods of improved communication.48 A first step in facilitating communication is creating a system for the FCMH provider to know that their patient is enrolled in an HV program. Second, a regular and preferred method of communication needs to be established. Mutual awareness between FCMH providers and HV programs is necessary, but not sufficient for optimal care and avoidance of duplication and fragmentation of services. Instead, to maximize the health of children we must move along the integration continuum to partnership and merging of systems. This requires a clear scope of service for HV and the FCMH, bidirectional communication, and shared responsibilities for outcomes. Optimally, FCMH and HV providers in a region must agree on a strategy, allocate responsibilities and services, and monitor implementation and outcomes. Table 1 details examples of different levels along the integration continuum for the FCMH and HV.

TABLE 1.

The Continuum of Integration of the FCMH and HV

Medical home and HV integration can result directly in improved individual child development and health outcomes. On a patient and family level, integration can translate into information sharing, referring bidirectionally, assisting in care coordination, reinforcing treatment plans and anticipatory guidance, improving maternal depression identification and treatment, and improved chronic disease management. On a population health level, integration promotes primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention within a single integrated system and can improve identification of community needs.49

When progressing along the integration continuum, it is necessary to consider the current level of integration, which partners should be included in the process, and what actions will be needed for enhanced integration. Partners should extend beyond home visitor programs and individual FCMH practices to include community members and other stakeholders to fully assess needs. Actions toward integration will likely be different in different regions and dependent on which partners are involved. They can range from a minimum of shared goals and mutual awareness to sharing of resources whether financial or human and sharing physical space and supplies.33 Ideally actions should work toward the goal of a shared infrastructure, including co-location and building sustainable integrated systems that have enduring impact.

Multiple methods have been proposed to facilitate integration between practitioners in the FCMH and home visitors. States have convened statewide task forces composed of Title V Maternal Child Health, Medicaid and CHIP programs, hospital provider groups, insurers, and families to start integrating service delivery systems.1 States are also using funds to integrate public-private service delivery systems and promote quality. One example of a funding mechanism to encourage integration is the Medicaid Health Home State Plan Option that provides funding strategies through Medicaid to enhance provider reimbursement for enhanced multidisciplinary collaboration.

Conclusions

The FCMH model of primary care delivery and HV models have synergistic goals. Both are critical in promoting child development and health in the context of their family and community. Pediatric primary care providers and home visitors must be pushed from the current status of playing nicely in the sandbox together in isolation toward merging systems of care. Health care professionals working in pediatric primary care practices (eg, physicians, nurses, and social workers) and in other health and education programs (eg, home visiting nurses, community case managers, and community health workers) must work on the same team to capitalize on each others’ capabilities and expertise, increase efficiencies, and improve the health of children and families.

With the vision of extending the medical home into the community (eg, the medical neighborhood), eliminating persistent health disparities, and the Affordable Care Act’s support for increased health care partnerships, this is an optimal time to integrate the FCMH and HV programs. Policies and funding streams need to be further aligned to encourage this integration. As HV programs are implemented in communities, connecting and partnering with the medical home should be a requirement. Ultimately HV programs should be co-located in the FCMH to optimize communication, collaboration, and child health outcomes. To truly improve the health of all children, the integration of HV and the FCMH should only be the first step in horizontal and vertical integration of services that promote the health, development, and well being of children and families.

Glossary

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- FCMH

family-centered medical home

- HV

home visitation

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- PCP

primary care provider

Footnotes

Dr Tschudy conceptualized and designed the manuscript and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Toomey conceptualized and designed the manuscript and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Cheng conceptualized and designed the manuscript and drafted the initial manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the HRSA NRSA Fellowship Training grant T32 HP10004-16-00 (Dr Tschudy), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant 1K24HD052559 (Dr Cheng), and the DC-Baltimore Research Center on Child Health Disparities P20 MD00165 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.VanLandeghem K, Schor E. New opportunities for integrating and improving health care for women, children, and their families. The Commonwealth Fund and the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs. February 2012. Accessed November 12, 2012. Available at: www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Issue-Briefs/2012/Feb/New-opportunities-for-integrating-health-care-for-women.aspx#citation

- 2.Starfield BB, Shi L. The medical home, access to care, and insurance: a review of evidence. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 suppl):1493–1498 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halfon N, DuPlessis H, Barrett E. Looking back at pediatrics to move forward in obstetrics. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20(6):566–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toomey SL, Chien AT, Elliott MN, Ratner J, Schuster MA. Disparities in unmet care coordination needs: analysis of the national survey of children’s health. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2011 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: March 25, 2012

- 6.Affordable care act maternal infant and early childhood home visiting program: supplemental information request for the submission of the statewide needs assessment. OMB control no. 0915-0333

- 7.American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Physicians (ACP), American Osteopathic Association (AOA). Joint principles of the patient centered medical home. March 2007. Available at: www.medicalhomeinfo.org/downloads/pdfs/JointStatement.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2012

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics. Council on Child and Adolescent Health The role of home-visitation programs in improving health outcomes for children and families. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 pt 1):486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starfield B. Primary care: Balancing health needs, services and technology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Pediatric Practice Standards of child care. Evanston, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Pediatrics Ad Hoc Task Force on Definition of the Medical Home The medical home. Pediatrics. 1992;90(5):774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. American Academy of Pediatrics The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 pt 1):184–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Homer CJ, Klatka K, Romm D, et al. A review of the evidence for the medical home for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/4/e922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooley WC, McAllister JW, Sherrieb K, Kuhlthau K. Improved outcomes associated with medical home implementation in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens GD, Vane C, Cousineau MR. Association of experiences of medical home quality with health-related quality of life and school engagement among Latino children in low-income families. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(6pt1):1822–1842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strickland BB, Jones JR, Ghandour RM, Kogan MD, Newacheck PW. The medical home: health care access and impact for children and youth in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toomey SL, Chan E, Ratner JA, Schuster MA. The patient-centered medical home, practice patterns, and functional outcomes for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(6):500–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beal AC, Doty DM, Hernandez SE, et al. Closing the divide: How do medical homes promote equity in health care- Results from the Commonwealth Fund 2006 Health Care Quality Survey. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong W, Dankwa-mullan I, Simon MA, Vega WA. The patient-centered medical home: a path toward health equity? Discussion paper, Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC. 2012. Available at: http://iom.edu/Global/Perspectives/2012/PatientCenteredMedicalHome.aspx Accessed November 12, 2012

- 20.Patient-centered primary care pilot projects guide. Patient-centered primary care collaborative web site. Available at: www.pcpcc.net/guide/pilot-guide Accessed November 11, 2012

- 21.Cheng TL. Primary care pediatrics: 2004 and beyond. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1802–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohmer RM. Managing the new primary care: the new skills that will be needed. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):1010–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arvey SR, Fernandez ME. Identifying the core elements of effective community health worker programs: a research agenda. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1633–1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Council on Community Pediatrics The role of preschool home-visiting programs in improving children’s developmental and health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):598–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olds DL, Robinson J, Pettitt L, et al. Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1560–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duggan A, Windham A, McFarlane E, et al. Hawaii’s healthy start program of home visiting for at-risk families: evaluation of family identification, family engagement, and service delivery. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1 pt 3):250–259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Hughart N, Scharfstein D, Guyer B, Healthy Steps Evaluation Team Early effects of the healthy steps for young children program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(4):470–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Mistry KB, et al. Healthy Steps for Young Children: sustained results at 5.5 years. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/3/e658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Phelps C, Kitzman H, Hanks C. Effect of prenatal and infancy nurse home visitation on government spending. Med Care. 1993;31(2):155–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman J, Siegel E, Cross A. Home visitors and child health: analysis of selected programs. Pediatrics. 1990;85(6):1059–1068 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karoly L. Early childhood interventions: Proven results, future promise. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschudy MM, Pak-Gorstein S, Serwint JR. Home visitation by pediatric residents - perspectives from two pediatric training programs. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(5):370–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng TL, Solomon BS. Translating life course theory to clinical practice to address health disparities [published online ahead of print May 16, 2013]. Matern Child Health J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor EF, Lake T, Nysenbaum J, Peterson G, Meyers D. Coordinating care in the medical neighborhood: critical components and available mechanisms. White paper (prepared by Mathematica Policy Research under contract no. HHSA290200900019I TO2). AHRQ publication no. 11-0064. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; June 2011

- 36.Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):989–997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy JB, Streett R. Family support and parenting education in the home: an effective extension of clinic-based preventive health care services for poor children. J Pediatr. 1989;115(6):927–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogler SD, Davidson AJ, Crane LA, Steiner JF, Brown JM. Can paraprofessional home visitation enhance early intervention service delivery? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(4):208–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens R, Margolis P, Harlan C, Bordley C. Access to care: a home visitation program that links public health nurses, physicians, mothers, and babies. J Community Health Nurs. 1996;13(4):237–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Margolis PA, Stevens R, Bordley WC, et al. From concept to application: the impact of a community-wide intervention to improve the delivery of preventive services to children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):E42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnes-Boyd C, Fordham Norr K, Nacion KW. Promoting infant health through home visiting by a nurse-managed community worker team. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(4):225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eckenrode J, Ganzel B, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Preventing child abuse and neglect with a program of nurse home visitation: the limiting effects of domestic violence. JAMA. 2000;284(11):1385–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson CS, Tandon SD, Duggan AK, Serwint JR. Communication between key stakeholders within a medical home: a qualitative study. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009;48(3):252–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997;278(8):637–643 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stille CJ, Primack WA, Savageau JA. Generalist-subspecialist communication for children with chronic conditions: a regional physician survey. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 pt 1):1314–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seid M, Varni JW, Bermudez LO, et al. Parents’ Perceptions of Primary Care: measuring parents’ experiences of pediatric primary care quality. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toomey SL, Cheng TL. APA-AAP Workgroup on the Family-Centered Medical Home. Home visiting and the family-centered medical home: synergistic services to promote child health. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(1):3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Margolis PA, Carey T, Lannon CM, Earp JL, Leininger L. The rest of the access-to-care puzzle. Addressing structural and personal barriers to health care for socially disadvantaged children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(5):541–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cusack CM, Knudson AD, Kronstadt JL, Singer RF, Brown AL. Practice-based population health: information technology to support transformation to proactive primary care (prepared for the AHRQ national resource center for health information technology under contract no. 290-04-0016.) AHRQ publication no. 10-0092-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; July 2010