Abstract

Scholars and policy makers have expressed concern that social and economic changes occurring throughout Asia are threatening the well-being of older adults by undercutting their systems of family support. Using a sample of 1,654 men and women aged 45 and older from the Chitwan Valley Family Study in Nepal, we evaluated the relationship between individuals’ nonfamily experiences, such as education, travel, and nonfamily living, and their likelihood of receiving personal care in older adulthood. Overall, we found that among individuals in poor health, those who had received more education, traveled to the capital city, or lived away from their families were less likely to have received personal care in the previous two weeks than adults who had not had these experiences. Our findings provide evidence that although familial connections remain strong in Nepal, experiences in new nonfamily social contexts are tied to lower levels of care receipt.

Keywords: aging, caregiving, family, Nepal, social trends/social change, intergenerational relations

Population aging is occurring at a rapid pace in many Asian countries as fertility rates decline and life expectancy increases (United Nations, 2010). As a result, an increasing number of older adults will require assistance in the form of income support, health care, and personal or ‘everyday’ care (Wolf & Ballal, 2006). Given that most Asian countries have relied historically on family-based support for older adults, the growing number of older adults undoubtedly places additional stress on family systems.

At the same time, social, economic, and institutional changes are occurring rapidly throughout Asia. One way these changes affect individuals is by giving them increased opportunities to participate in new activities, such as schooling, employment outside of the family, and travel. Concern that these recent changes may be weakening family support for older adults has motivated a growing body of literature in this area (e.g., Frankenberg, Lillard, & Willis, 2002; Lee, Parish, & Willis, 1994; Martin, 1990a, 1990b; Mason, 1992). However, the past literature has two main limitations. First, we know relatively little about how one’s own experiences with nonfamily organizations influence receipt of care for oneself later in life. Most of the studies focus on how children’s experiences with nonfamily activities influence their support of parents (e.g., Brauner-Otto, 2009; Knodel & Saengtienchai, 1996; Pienta, Barber, & Axinn, 2001; Piotrowski, 2008). Second, relatively few studies have examined the receipt of personal care, such as help with bathing, dressing, and feeding or household tasks. Instead, previous research has focused on how changing social and economic institutions have influenced other types of care, including co-residence (Cameron, 2000; Frankenberg, Chan, & Ofstedal, 2002b; Knodel, Saengtienchai, & Sittitrai, 1995; Zhang, 2004) and income transfers (Brauner-Otto, 2009; Frankbenberg et al., 2002a; Lee et al., 1994; Lillard & Willis, 1997).

Our study seeks to understand the extent to which individuals’ experiences with nonfamily institutions influence the personal care they receive from family members in older adulthood. We have three main objectives. First, we construct a guiding theoretical framework pulling together theories typically applied to care giving with those of social change. Second, we examine how previous nonfamily experiences influence the receipt of care in older adulthood. Third, we examine how nonfamily experiences moderate the influence of poor health on the receipt of care in older adulthood. Our study relies on data from the Chitwan Valley in rural, south-central Nepal, an area which has recently experienced dramatic social, economic, and institutional changes. Consequently, this setting provides a unique opportunity to examine the relationship between a shift toward nonfamily organization and care in older adulthood.

Setting

The Chitwan Valley has recently undergone a period of rapid social change. Until the 1950s, this valley was covered with virgin jungle and only sparingly inhabited by indigenous ethnic groups (Guneratne, 1994). In the 1950s, the government began clearing parts of the jungle, implemented malaria eradication efforts, and instituted a resettlement plan leading to the migration to the region of many different ethnic groups, including both Buddhists and Hindus. By the late 1970s, roughly two thirds of this valley was cultivated and a small town, Narayanghat, was forming in one corner. However, the vast majority of residents were employed in agriculture and continued to use traditional methods of production.

In 1979, the first all-weather road was completed linking Narayanghat to India and eastern Nepalese cities. Following that, two other roads were built—one to the west and one north to the capital city, Kathmandu. Because of Narayanghat’s central location, it quickly became the transportation hub for the entire country. This led to the rapid expansion of schools, health services, wage labor, markets, and mass transportation (Axinn & Yabiku, 2001; Pohkarel & Shivakoti, 1986).

The introduction of new schools and other organizations changed the way family life in the Chitwan Valley was organized. More activities, such as education, living, and work, took place outside of the family, whereas almost all activities previously occurred within the confines of one’s natal home until marriage, and then within the confines of the marital home. For instance, as schools became more common, education became a nonfamily activity (Beutel & Axinn, 2002). As people interacted more with nonfamily organizations, other activities of daily living began to move outside the family. For example, individuals were more likely to reside away from their natal homes and travel to other areas for work or recreation. That is, the spread of nonfamily organizations and community services led to a change for individuals in both the number and types of their nonfamily experiences.

In this setting, family ties and support have generally been very strong, especially towards the husband’s family. State-based programs to meet the financial needs of older adults and the health care system are minimal and market means of providing personal care (e.g., nursing homes, home-care nursing services) are nearly nonexistent (Chalise, 2006), so older adults must rely on family members for all forms of support. Historically, for most ethnic groups living in the Chitwan Valley, a married son and daughter-in-law would live with the son’s parents. Previous research has found that the vast majority of adults continue to feel that adult children should care for their elderly parents (Pienta et al., 2001), although familial ties remain stronger to the husband’s family than to the wife’s. Past research in this setting has found that adult children were more likely to provide support to the husband’s parents than the wife’s (Brauner-Otto, 2009).

Although research has found that familial ties are still strong in Nepal, those ties do appear to be weakening. Empirical research has found that most adult children still say they should support their elderly parents, but individuals who had more education or who had traveled to Kathmandu or outside of Nepal were less likely to believe that a married child should care for his or her aging parents (Pienta, Barber, & Axinn, 2001). In addition, the pattern of co-residence is no longer universally followed; by 1996, less than one third of married couples were living with the husband’s parents and fewer than three per cent were living with the wife’s parents (Brauner-Otto, 2009). Past research has found that adult children are less likely to live with their parents if they have worked outside the family or if either of their parents has traveled outside of Nepal (Pienta et al., 2000). Also, couples who lived closer to schools were less likely to have offered support to the wife’s parents than couples who lived farther from schools (Brauner-Otto, 2009).This paper builds on this research by investigating the relationship between experiences with these nonfamily organizations and receipt of personal care.

Linking social change to care giving and receiving

Substantial bodies of literature exist on both the link between the expansion of opportunities for nonfamily experiences and family relations (e.g., Axinn & Yabiku, 2001; Hoelter, Axinn, & Ghimire, 2004; Yabiku, 2005) and on care giving in the context of rapid social and economic change (e.g., Frankenberg et al., 2002a; Lee et al., 1994; Zhang, 2004). However, little research has brought these two topics together. In this paper we develop a framework for understanding this link between nonfamily experiences and receipt of care in later adulthood.

Commonly used theories that attempt to explain patterns of care giving and receiving can be categorized into two groups: theories of altruism or mutual aid, and theories of reciprocal exchange. Under the altruistic or mutual aid model, family members care for one another because they care about each other’s well-being, with giving often occurring in times of need (Hogan, Eggebeen, & Clogg, 1993; Lee et al., 1994; McGarry & Schoeni, 1997). For instance, if a parent has an illness, his/her child may help by cooking meals for the parent—illness and disability are the primary determinants of receiving care. Under the reciprocal exchange model of care giving, family members may offer assistance in response to actual previous or expected future gifts (Goldscheider, Thornton, & Yang, 2001). Proponents of this theory cite three common examples: adult children assisting their parents to repay them for the assistance they received in childhood, adult children assisting their parents and expecting their parents to repay them through inheritance, and parents assisting their children to insure that their children will in turn care for them (the parents) in their old age (Becker, Beyene, Newsom, & Mayen, 2003; Henretta, Hill, Li, Sodo, & Wolf, 1997; Silverstein, Parrott, & Bengtson, 1995). Building off these two perspectives on care giving and receiving, we identify three specific mechanisms, described further below, that may operate to produce a relationship between nonfamily experiences and care receipt in older adulthood: increased individualism, increased wealth, and decreased availability of caregivers.

Individualism

Participation in nonfamily experiences may be linked to a lower likelihood of receiving care through increased individualism. The modes of social organization framework suggests that those who have had significant experiences outside the family are more likely to hold individualistic attitudes (Thornton & Fricke, 1987; Thornton & Lin, 1994). A key premise of this framework is that as more nonfamily institutions, such as schools, appear in communities, there is a fundamental shift in the social organization of daily life that draws individuals out of social networks dominated by family members and, via participation with these institutions, into new, nonfamily social networks. With this shift, individuals’ own ideas about certain behaviors and their perceptions of others’ ideas about those behaviors begin to change. More specifically, participants in nonfamily institutions become increasingly individualistic and emotionally nucleated, meaning that they become more concerned with their own welfare and the welfare of their children and less concerned with extended families and familial networks. (Caldwell, 1982; Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 1988). This is due to the increased time spent away from the family, increased interactions with people who hold different, specifically nonfamily oriented values, and because of the new ideas they are exposed to in these nonfamily locations (Thornton & Fricke, 1987; Thornton & Lin, 1994).

Given that those who have had nonfamily experiences are likely to hold more individualistic attitudes, the increased individualism may translate into a lower likelihood of care receipt in two main ways. First, individuals who are more individualistic may be less apt to ask their family members for assistance with their personal care needs. They may be less likely to recognize their dependencies or less willing to request and accept offers of assistance. Second, parents who have had nonfamily experiences may socialize their children to hold more individualistic attitudes and, as a result, their children may feel less committed to caring for their parents.

Availability of care providers

Participation in nonfamily experiences may also be linked to a lower likelihood of receiving care through a decreased availability of caregivers. Situations may arise when family members recognize that an older adult needs assistance and intend to help but are unavailable to do so. The extent of one’s nonfamily experiences may influence whether family members are available to care for one in older adulthood. The children of parents who have had nonfamily experiences are more likely to want to pursue education or employment outside of the family, following their parent’s example, thus possibly taking the children away from their parents and rendering them unavailable to help. In addition, parents who have had nonfamily experiences tend to have more social networks outside the family, which they may use to help their children find jobs or living situations elsewhere. In turn, the children of older adults who have had nonfamily experiences are more likely to be away from home pursuing school, work, or travel and, thus, unavailable for care giving.

Wealth

Nonfamily experiences may also be linked with a higher likelihood of receiving care through increased wealth. Households where the parents have had nonfamily experiences tend to have more wealth than households where parents have not had these experiences. In turn, wealth may influence the likelihood of an older adult receiving care in two main ways. First, wealthier households have more resources to invest in children, such as purchasing school books or supporting children’s travel to and living in cities. Based on the reciprocal exchange model described above, this greater investment in children would result in a higher likelihood of these parents receiving care from their children because of the higher debt that children must repay to their parents. Second, children who hope to inherit wealth from their parents may have a greater incentive to provide care for them. As a result, parents who have had nonfamily experiences may be more likely to receive care from children hoping to inherit the wealth these experiences have helped them accumulate. It is also worth noting that although wealth can also be used to hire care providers, in this setting the formal-care sector is nearly nonexistent and less than five per cent of the respondents receiving care identified a non-relative as the provider.

Nonfamily experiences as moderator

Nonfamily experiences may have a direct effect on the receipt of care through the mechanisms described above, or they may moderate the relationship between health status and care receipt in older adulthood. In other words, while health problems create the need for care, the effect of health status on care may vary according to the older adult’s nonfamily experiences.

Whether nonfamily experiences exert a positive or negative moderating effect on the relationship between health and care will depend on which mechanism is at work. For example, consider the scenario in which increased education influences care receipt by increasing individualism. If adults who have had more education raise more individualistic children, those children may be less likely to provide care for a specific health situation than children who are more family-centered. In this case, we expect the effect of an older adult’s health status on the likelihood that he/she receives care to depend on the amount of education he/she had. Older adults in poor health who had more education will be less likely to receive care than those in poor health with less education. Alternatively, consider the scenario in which increased education influences care receipt by increasing wealth. In this situation, adults who had more education are wealthier. If their children are motivated by this increased wealth to provide care, then the older adult with more education will be more likely to receive care in a specific health context than an adult who had less education.

Of course, the results we present here should be interpreted with caution regarding the nature of the true causal effects that our estimates are designed to reflect. The individuals in our sample were not randomly assigned to participate in nonfamily activities, so we take great care to control for potentially endogenous background characteristics, including gender, age cohort, and ethnicity. Gender inequalities have long been a dynamic of Nepalese society (Acharya & Bennett, 1981; Bennet, 1983; Morgan & Niraula, 1995; Beutel & Axinn, 2002). While the position of women in Nepal has improved greatly in recent decades, the older women included in our analysis would have been relatively constrained from participating in education, employment, and other activities outside of the family. In addition, past research has demonstrated that levels of support received in older adulthood often vary by gender (Knodel & Ofstedal, 2003; Oftstedal, Reidy, & Knodel, 2004; Yount & Agree, 2005). With regard to age, as nonfamily organizations increased over time, younger age cohorts would have had more opportunities for nonfamily involvement throughout their life course. We also control for ethnicity, which is complex, multifaceted, and interrelated with religion in Nepal. Although a full description of the ethnic groups in this setting is beyond the scope of this article (for detailed descriptions, see Acharya & Bennett, 1981; Bista, 1972; Fricke, 1986; Gurung, 1980), it is important to recognize that opportunities to participate in nonfamily activities may vary by ethnicity.

To summarize, the Chitwan Valley has experienced a significant increase in nonfamily activities, such as schooling, nonfamily living, and travel. Participating in these activities may alter the care one receives later in older adulthood by fostering individualistic attitudes, increasing wealth, and reducing available caregivers. Unique data from the Chitwan Valley Family Study enable us to test two hypotheses about the effects of nonfamily activities on receipt of care in older adulthood:

Hypothesis 1: Nonfamily experiences will be associated with receipt of care in older adulthood.

Hypothesis 2: Nonfamily experiences will moderate the relationship between health and receipt of care in older adulthood.

Method

Data

The study uses data from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS) conducted in rural Nepal. This study combines survey and ethnographic methods to obtain detailed measures of individual life histories and community context. In 1996, the CVFS collected information from residents of a systematic sample of 171 neighborhoods in Western Chitwan Valley—it interviewed every resident between the ages of 15 and 59 in the 171 sampled neighborhoods, and their spouses. Because of large age differentials between spouses, the age distribution of the final sample ranged from 13 to 80 years old. The overall response rate of 97 per cent yielded 5,271 completed interviews. All interviews were conducted in the most common language in Nepal, Nepali (questions presented below are translated). Life History Calendar techniques were used to collect reliable information regarding residents’ education, labor force participation, living arrangements, travel, and family formation behaviors throughout the life course (Axinn, Pearce, & Ghimire, 1999).

In 2007, the CVFS collected detailed information about the health and care receipt for all residents aged 45 and older in 151 of the sample neighborhoods.1 This age is lower than what is often used in studies of care-giving for older adults. However, work in the Chitwan Valley is generally very physically demanding and most people in their 40s have been participating in hard physical labor for over 30 years. As a result, in this setting, many individuals are already experiencing many of the physical and mental signs of aging by the age of 45. For example, in our study, over half of the adults between ages 45 and 54 years reported difficulty stooping, kneeling, or crouching, and nearly half (46 per cent) of respondents in this age group reported difficulty walking continuously for an hour. Additionally, medical resources in Nepal are much more limited than in Western countries, which means that minor ailments are more likely to become physical impairments that require assistance from others.

This 2007 survey of older adult respondents was conducted at the household level. If the older adult was present at the time of the interview, the interviewer asked the questions directly of him or her. In situations where the target person was not present at the time of the interview, other household members served as proxy reporters. Information was gathered for 99 per cent of eligible individuals, yielding 2,155 completed interviews. We are forced to exclude 490 respondents from our analysis sample who were not eligible to be interviewed in 1996 and therefore have missing data on our key independent and control variables. (We ran separate models with measures of sociodemographic characteristics and wealth predicting receipt of care using two separate samples— one sample including all individuals interviewed in 2007 and a second sample including only those interviewed in 1996 and 2007—and found no substantive differences between the results using the two different samples). In addition, we drop six respondents who reported an “other” ethnicity group and three respondents with missing data on key control variables. Our final analytic sample includes 1,654 older adults.

Measures of receipt of care

In the 2007 survey, respondents were asked, “Now I would like to talk about care received from other people. There are situations in which people receive care or assistance, perhaps because of difficulties with the activities just discussed, or because of a long-term physical or mental illness or a disability. During the past two weeks, have you (has she/he) received any such care or assistance?” This question followed a series of questions about their difficulty with activities of daily living, such as eating, bathing, and getting out of bed. We create a measure equal to one if the older adult reported receiving assistance and zero if not. Descriptive statistics for this, and all measures used in the analyses presented in this table, can be found in Table 1. Approximately six per cent of all individuals reported receiving care or assistance in the last two weeks.2, 3

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for variables used in analyses (N = 1,654)

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||||

| Receives care | 0.06 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Nonfamily experiences | ||||||

| Years of education | 2.65 | 4.35 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Ever lived separately from family | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Ever traveled to Kathmandu | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Non-family experience index | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Health | ||||||

| Health status (1 = excellent, 4 = poor) | 2.87 | 0.85 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Caregiver availability | ||||||

| Number of sons | 2.51 | 1.74 | 0 | 9 | ||

| Number of daughters | 0.12 | 0.76 | 0 | 11 | ||

| Wealth | ||||||

| Number of stories in house | 1.46 | 0.57 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Owns land | 0.90 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Number of livestock | 4.15 | 3.44 | 0 | 26 | ||

| Number of durables | 2.85 | 1.57 | 0 | 8 | ||

| Has electricity | 0.96 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Annual household income (Nepalese rupees) | ||||||

| 0 – 10,000 | 0.14 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 10,001 – 25,000 | 0.15 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 25,001 – 50,000 | 0.29 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 50,000 and above | 0.43 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| Age cohort | ||||||

| 45 – 54 years | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 55 – 64 years | 0.35 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 65 – 74 years | 0.14 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 75 and over | 0.02 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Ethnic group | ||||||

| Upper Caste Hindu | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Hill Tibeto Burmese | 0.17 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Lower caste Hindu | 0.11 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Newar | 0.07 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Terai Tibeto Burmese | 0.19 | 0 | 1 | |||

Measures of nonfamily experiences

We use information gathered in the Life History Calendars in 1996 to create four measures of the individual’s nonfamily experiences. First, we created a count measure of the number of years of formal education the respondent had attained. Approximately three per cent of respondents reported more than 15 years of education, which is roughly equivalent to graduating from college. We recoded the measure of education, capping the outliers at 15 years. The mean number of years of education for this capped measure was just under 3.

We also created two dichotomous measures for whether the individual had ever lived away from home (alone, in dormitories, with unrelated individuals, and other nonfamily possibilities) or had ever traveled to Kathmandu, the capital city of Nepal. Both of these experiences represent substantial separation from the family. A quarter of respondents had lived away from their families at some point in time and almost 40 per cent had traveled to Kathmandu.

Finally, we created an index counting the number of these nonfamily experiences for each respondent. For education we coded a dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the respondent reported more than the mean years of education and 0 otherwise. We then summed this measure with the two dichotomous measures of nonfamily living and traveling. The mean number of experiences was just under 1.

Measures of health status

Given the theoretical argument for altruistic giving, it is important to control for the health of the individual, given that individuals in worse health are more likely to receive care. Our measure of health is based on responses to the question, “Overall, would you say that your (her/his) health is excellent, good, fair, or poor?” Responses ranged from 1 to 4 where 1 = excellent and 4 = poor. Overall, respondents generally had low assessments of their health—the mean for all the elderly was almost 3.

Measures of caregiver availability

We control for the number of caregivers available by including measures of the number of sons and daughters the individual gave birth to or fathered. We distinguish between the sons and daughters because gender plays an important role in social norms dictating care giving in Nepal. Sons typically live with their parents, bringing their wives into the household, whereas daughters move to their husband’s home. Consequently, a couple who has a son likely would have at least two caregivers available in their household in their old age, whereas a couple with only daughters may be more likely to live alone. Another advantage of living with a son and daughter-in-law in older adulthood is that providing assistance often requires intimate physical contact, and according to local customs, the caregiver should be the same gender as the recipient of the care.

Measures of wealth

We include five measures of wealth in these analyses. In the Chitwan Valley, household goods and landownership are a typically more meaningful measure of wealth or of need of support than cash income, and these wealth measures reflect this fact. The first measure is a dichotomous measure equal to one if the household owns the land their house is on and zero otherwise. The second and third measures are counts of the number of large livestock and consumer durables the family owns, respectively. The livestock measure includes bulls, cows, buffaloes, sheep, goats, and pigs. The consumer durables measure includes radios, televisions, bicycles, motorcycles, carts, tractors, irrigation pumpsets, gobar gas plants, and farm tools such as threshers, chaff cutters, sprayers, and corn shellers. The fourth measure is a count of the number of stories in the house that the family is living in. We also include a measure of the family’s household cash income in the previous year measured in Nepalese rupees.

Controls

In order to properly specify the models, we control for various characteristics of the respondents that may influence both one’s nonfamily experiences and the likelihood of receiving care. Age is measured using dichotomous variables for four birth cohorts: ages 45 to 54, ages 55 to 64, ages 65 to 74, and ages 75 and over. The group ages 45 to 54 is the reference group in all analyses. Gender is a dichotomous measure equal to 1 if the respondent is female and 0 otherwise. We use dichotomous variables to control for five classifications of ethnicity: Uppercaste Hindu, hill TibetoBurmese, Lowercaste Hindu, Newar, and terai TibetoBurmese. Uppercaste Hindu is the reference group in all analyses.

Analytic strategy

We use multivariate logistic regression techniques to examine the relationship between nonfamily experiences and receipt of care. All analyses include controls for the respondents’ age, gender, ethnicity, wealth, and the availability of caregivers. We run the models using the xtlogit command in Stata, which adjusts for the fact that individuals were clustered in the sample neighborhoods.

Our analysis has two main sections. In the first section, we examine the main effects of health and nonfamily experiences on receipt of care. Next, we consider the extent to which nonfamily experiences moderate the relationship between health and receipt of care. To accomplish this part of the analysis, we test models that include a set of interactions between health status and each measure of nonfamily experiences—years of education, nonfamily living, travel to the capital city, and the nonfamily experience index.

Results

Table 2 presents results from a set of equations in which receipt of care is regressed on measures of older adults’ health and nonfamily experiences. All tables present estimated coefficients with standard errors. Model 1 includes the measures for health status, the availability of caregivers, wealth and the control variables—age cohort, gender, and ethnicity. As expected, we see that health status, gender, and number of sons have an important influence on the likelihood of receiving care. The unstandardized coefficient of .71 for health status means that for every one unit decline in health, the log odds of receiving care increases by .71. Family members appear to be responsive to older adults’ need for assistance due to functional limitations or illness. Supplementary analyses show similar effects of health status on receipt of care when more specific measures of functional limitations are used, such as difficulty getting out of bed, eating, or bathing (results not shown). This finding supports the theory that care is given at least partially for altruistic reasons.

Table 2.

Unstandardized coefficients from regression of nonfamily experiences on receiving care (N = 1,654)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonfamily experiences | |||||

| Years of education | −.03 | ||||

| (.04) | |||||

| Ever lived separately from family | .11 | ||||

| (.31) | |||||

| Ever traveled to Kathmandu | .00 | ||||

| (.24) | |||||

| Index of non-family experiences | −.08 | ||||

| (.15) | |||||

| Health | |||||

| Health status (1 = excellent, 4 = poor) | .71*** | .70*** | .71*** | .71*** | .70*** |

| (.17) | (.17) | (.17) | (.17) | (.17) | |

| Caregiver availability | |||||

| Number of sons | .11† | .11† | .12† | .11† | .11† |

| (.06) | (.07) | (.07) | (.06) | (.07) | |

| Number of daughters | .06 | .06 | .06 | .06 | .06 |

| (.13) | (.13) | (.13) | (.13) | (.13) | |

| Wealth | |||||

| Number of stories in house | −.12 | −.13 | −.13 | −.12 | −.12 |

| (.21) | (.21) | (.21) | (.21) | (.21) | |

| Owns land | .21 | .21 | .21 | .20 | .20 |

| (.43) | (.43) | (.44) | (.43) | (.43) | |

| Number of livestock | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| (.04) | (.04) | (.04) | (.04) | (.04) | |

| Number of durables | .02 | .03 | .02 | .02 | .03 |

| (.09) | (.09) | (.09) | (.09) | (.09) | |

| Has electricity | .76 | .77 | .77 | .76 | .76 |

| (.77) | (.76) | (.77) | (.77) | (.77) | |

| Household income (Nepalese rupees)a | |||||

| 10,000 | −.07 | −.07 | −.06 | −.07 | −.07 |

| (.42) | (.42) | (.42) | (.42) | (.42) | |

| 25,000 | −.12 | −.12 | −.11 | −.12 | −.12 |

| (.38) | (.38) | (.38) | (.38) | (.38) | |

| 50,000 | .09 | .11 | .09 | .09 | .09 |

| (.37) | (.37) | (.37) | (.37) | (.37) | |

| Controls | |||||

| Age cohortb | |||||

| 55 – 64 years | −.17 | −.22 | −.18 | −.17 | −.18 |

| (.26) | (.27) | (.26) | (.26) | (.26) | |

| 65 – 74 years | .28 | .18 | .27 | .28 | .26 |

| (.33) | (.35) | (.34) | (.33) | (.34) | |

| 75 and over | .38 | .24 | .38 | .38 | .34 |

| (.83) | (.85) | (.83) | (.83) | (.84) | |

| Female | .50* | .38 | .54* | .50* | .44† |

| (.24) | (.27) | (.26) | (.24) | (.26) | |

| Ethnicityc | |||||

| Hill Tibeto Burmese | .28 | .27 | .27 | .28 | .29 |

| (.33) | (.33) | (.33) | (.33) | (.33) | |

| Lower caste Hindu | .42 | .38 | .43 | .42 | .39 |

| (.39) | (.39) | (.39) | (.39) | (.39) | |

| Newar | .31 | .32 | .31 | .31 | .32 |

| (.45) | (.45) | (.45) | (.45) | (.45) | |

| Terai Tibeto Burmese | −.33 | −.36 | −.32 | −.33 | −.36 |

| (.38) | (.38) | (.38) | (.38) | (.38) | |

| X2 | 31.43 | 31.91 | 31.47 | 31.44 | 31.60 |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

Excluded group is 0 – 10,000;

Excluded group is ages 45 – 54;

Excluded group is Upper Caste Hindu.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Older adults with more sons were also more likely to receive care, which is a finding we expected due to the historical patterns of co-residence described above. Finally, the finding that women were more likely to receive care than men echoes the findings of other studies on personal care giving in Asia (e.g. Zimmer & Kwong, 2003).

In Models 2 – 5 we add in our measures of nonfamily experiences. Years of education (Model 2), living separately from family (Model 3), traveling to Kathmandu (Model 4), and the number of nonfamily experiences (Model 5) are not significantly related to the receipt of care. Thus, the findings do not support our first hypothesis that older adults’ nonfamily experiences are related to receipt of care.

Having considered the main effects of health and nonfamily experiences in Table 2, we now investigate the moderating influences of nonfamily experiences on the relationship between health and receipt of care. The models in Table 3 test our second hypothesis, which is that older adults’ nonfamily experiences will condition the association between health and nonfamily experiences. The equations used to estimate the models shown in Table 3 add terms capturing the interaction of nonfamily experiences and health to the equations in Table 2. All models include the controls shown in Table 2.

Table 3.

Unstandardized coefficients from regression of nonfamily experiences on receiving care and interactions of health status and nonfamily experiences (N = 1,654)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of education | .22* | |||

| (.10) | ||||

| Health status × Years of education | −.09* | |||

| (.03) | ||||

| Ever lived separately from family | 3.16** | |||

| (1.06) | ||||

| Health status × Ever lived separately from family | −.99** | |||

| (.34) | ||||

| Ever traveled to Kathmandu | 3.23** | |||

| (1.08) | ||||

| Health status × Ever traveled to Kathmandu | −1.01** | |||

| (.33) | ||||

| Index of nonfamily experiences | 1.76*** | |||

| (.46) | ||||

| Health status × Index of nonfamily experiences | −.60*** | |||

| (.15) | ||||

| Health status (1 = excellent, 4 = poor) | .93*** | 1.02*** | 1.22*** | 1.37*** |

| (.20) | (.21) | (.25) | (.25) | |

| X2 | 38.24* | 38.54* | 38.52* | 45.65** |

Notes: All models include controls for health status, sociodemographic characteristics, wealth, and caregiver availability. Standard errors in parentheses.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We continue to see a strong positive association between health and receipt of care. More importantly, we find evidence supporting our hypothesis that nonfamily experiences moderate the influence of health on receipt of care. Model 1 in Table 3 shows that the effect of health on receipt of care depends on years of education. The significant and negative interaction between years of education and health indicates that the positive relationship between worse health and receipt of care is weaker at higher levels of education (and that the positive effect of education on care receipt is weaker for those in worse health). Among those with more years of education, the slope representing the health-receipt of care relationship flattens.

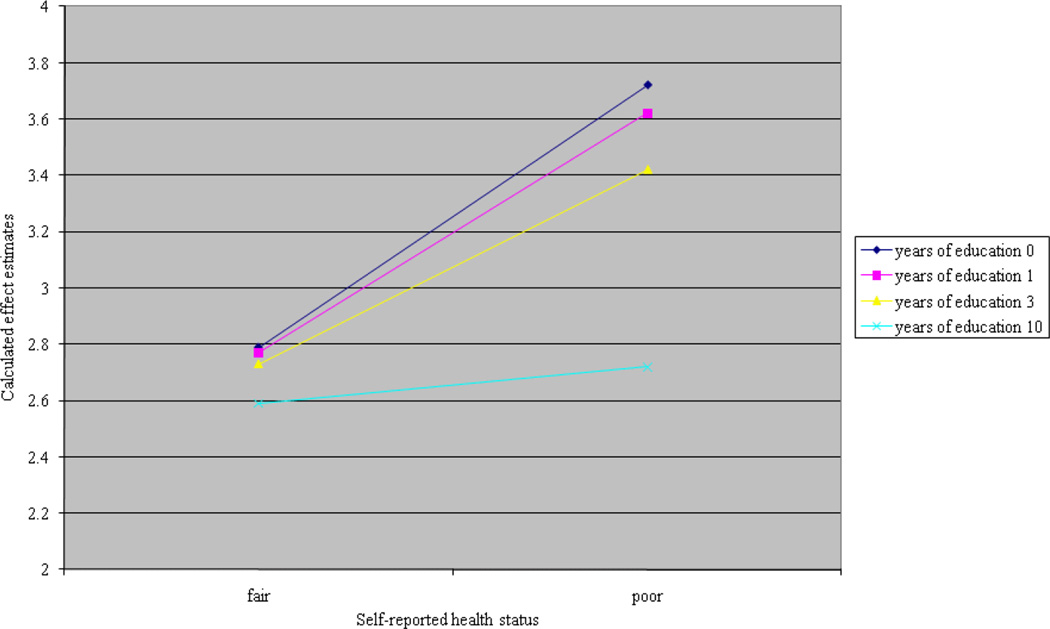

Figure 1 illustrates this pattern by graphing the effect of health status on the likelihood of getting care, conditional on years of education. Each line shows the relationship between health status and the likelihood of getting care for people with different levels of education. To illustrate the interaction we show the relationship for people with no education (blue line with diamonds), 1 year of education (pink line with squares), 3 years of education, the mean number of years for people in our sample (yellow line with triangles), and 10 years of education, the completion of high school in Nepal (light blue line with stars). Among the older adults in poor health, those who have had more education are less likely to receive care than their counterparts who have had less education, and the gap in care is even wider for those in poor health as opposed to fair health. More educated people are less likely to get needed care. That is, the positive effect of health status on care receipt is less for people with more education.

Figure 1.

Interaction between years of education and health status—Effect on receiving care

Model 2 in Table 3 shows how the effect of health varies between those who have lived separately from family and those who have not. Again, the significant and negative interaction term between nonfamily living and health indicates that the effect of health on receipt of care is weaker among those who have experienced nonfamily living. Similarly, in Model 3, we see that the effect of health is weaker among those who have traveled to Kathmandu, the capital city. Model 4 includes the interaction between number of nonfamily experiences and health and also reveals a negative interaction between number of nonfamily experiences and health status. Taken together, the results indicate that older adults in poor health are more likely to receive care, but the link between health and receipt of care is weaker among those who have had more nonfamily experiences.

Overall, these findings support our hypothesis that nonfamily experiences moderate the relationship between health and receipt of care. They suggest that the influence of health on receipt of care is smaller among older adults who have had nonfamily experiences. In other words, older adults in poor health are more likely to receive care than older adults in good health, regardless of their nonfamily experiences. However, among the older adults in poor health, those who have had nonfamily experiences are less likely to receive care than their counterparts who have not had nonfamily experiences. Our models shown in Table 2 do not show an effect of nonfamily experiences because when we look across health status groups the effect is washed out. By including interaction terms we are able to look at the effect of nonfamily experiences on receipt of care within health status groups, and as a result see this potentially detrimental effect of nonfamily experiences on the likelihood of receiving care among older adults.

According to our theoretical framework, the negative interaction term between health and nonfamily experiences can be interpreted in two non-mutually exclusive ways. First, the negative interaction term may indicate that family members are less responsive to the health needs of older adults who have had nonfamily experiences. Second, older adults who have had nonfamily experiences may be less willing to request or receive assistance with health problems.

Discussion

The rapid and dramatic demographic, social, and economic changes that have swept through Nepal and many other countries over the past 50 years have raised concern regarding the well-being of older adults. In particular, the academic and policy worlds fear that these changes will result in an abandonment of older family members. There has been much discussion over whether historical systems of care, living arrangements, and familial responsibilities that once centered around or within the family network are changing to look more like Western, individualistic systems and whether older adults are suffering as a result. By exploring care for older adults in a setting currently experiencing such dramatic social and economic change, we learn new information about the relationship between social context and care giving and receipt.

This paper contributes to this discussion in two ways. First, we focus on personal care, which is an area that has received far less attention than co-residence or monetary support for parents, despite its essential connection to health and well-being. In a setting like Nepal, where the health care system is minimal and nursing homes are nonexistent, family care is the only care option when one becomes ill or disabled. Second, we examine the effect of the older adult’s own experiences on whether he or she receives care. It is not surprising that most studies have focused on the effects of children’s experiences on their care provision—younger people have gone to school, lived away from their families, and traveled more often than the older generations. However, as the first generations to experience nonfamily living reach older adulthood, investigating how these experiences influence receipt of care later in life expands our understanding of how social change influences family care dynamics.

In order to investigate how the new experiences made possible by dramatic social change may affect the care older adults receive, we construct and empirically test a framework that combines theories of social change, particularly the modes of social organization framework, with theories of care giving. Our empirical analysis provides evidence that social change is influencing the care situation for older adults in Nepal. When we look at older adults in poor health we find that those with more nonfamily experiences—more schooling, living away from their families, and traveling to the capital city—are less likely to have received care in the previous two weeks than those with fewer experiences. Given that the social changes currently occurring in Nepal and similar settings typically result in dramatic increases in education, travel, living and work opportunities, it is probable that older and sick adults will increasingly find themselves lacking necessary personal care.

Our analysis also yields important conclusions regarding the specific motivation behind care giving and receiving in Nepal. In particular, these findings support the altruistic model of giving. Older adults who were in need of care, those who had lower self reported health, were more likely to receive it. Similarly, those who had more caregivers available, that is had given birth to more sons, were also more likely to receive care. However, we do not find evidence that the increased prevalence of nonfamily experiences (i.e., social change) influences care receipt through caregiver availability. Even though number of sons born was positively associated with care receipt, the inclusion of this variable in our models does not influence the effect estimates of nonfamily experiences on care receipt (results not shown). So, while nonfamily experiences influence the likelihood of receiving care, they do not appear to do so by influencing caregiver availability.

We also do not find evidence in support of the reciprocal exchange model for care giving. Recall that those who had received more education were not more likely to receive care, nor was wealth related to likelihood of receiving care. This is in contrast to previous research in this setting which found that those with more education were less likely to have provided support to their parents (Brauner-Otto, 2009). One reason for these conflicting findings may be that the work presented here is from the care recipient’s perspective, whereas other research has been from the care provider’s perspective. Also, the type of care provided is different—here we look at physical care whereas previous research looked at material support or attitudes about support.

Altogether, our results suggest that nonfamily experiences influence care for older adults through attitudinal or ideational changes. Based on our theoretical framework, this is evidence that the social changes occurring are encouraging individualism and further distancing people from their families. Future research should focus more specifically on the role of changing attitudes as a mechanism through which social change influences old age support. The research would be particularly informative if it incorporates both the attitudes of the older adults as well as their children, and, of course, longitudinal data on attitudes would also be crucial.

In conclusion, this research provides an important glimpse into the complex way social change is influencing the well-being of older adults. Although there still appears to be fairly strong levels of familial ties, the actual receipt of personal care is negatively influenced by the experiences individuals have in these new nonfamily social contexts. As these experiences become increasingly common, we can expect to see a decline in family care for older adults.

Footnotes

If any of the original households or respondents moved out of the sample neighborhood, they were followed.

The low incidence of care receipt is likely more an artifact of the data used here rather than a commentary on the overall level of care for rural, Nepalese older adults. The specific question used to we rely on in this paper gave a “snapshot” of care during the previous two weeks.

The respondents who reported receiving care were asked to identify their relationship with each care provider. The vast majority of care providers were children or grandchildren of the older adults, and less than 5% reporting receiving care from a non-relative.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Yarger, Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California, San Francisco.

Sarah R. Brauner-Otto, Mississippi State University

References

- Acharya M, Bennett L. Rural women of Nepal: An aggregate analysis and summary of eight village studies. Kathmandu, Nepal: Tribhuvan University; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, Pearce LD, Ghimire DJ. Innovations in life history calendar applications. Social Science Research. 1999;28:243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, Yabiku ST. Social change, the social organization of families, and fertility limitation. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106:1219–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Beyene Y, Newsom E, Mayen N. Creating continuity through mutual assistance: Intergenerational reciprocity in four ethnic groups. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;58:S151–S159. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L. Dangerous wives and sacred sisters: Social and symbolic roles of high-caste women in Nepal. New York: Columbia University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel AM, Axinn WG. Gender, social change, and educational attainment. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2002;51:109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bista DB. People of Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ratna Pustak Bhandar; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Brauner-Otto SR. Schools, schooling, and children's support of their aging parents. Ageing & Society. 2009;29:1015–1039. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC. Theory of fertility decline. New York: Academic; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Chalise HN, Brightman JD. Aging trends: Population aging in Nepal. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2006;6:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L. The residency decision of elderly Indonesians: A nested logit analysis. Demography. 2000;37:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg E, Lillard L, Willis RJ. Patterns of intergenerational transfers in Southeast Asia. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002a;64:627–641. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg E, Chan A, Ofstedal MB. Stability in living arrangements in Indonesia, Singapore, and Taiwan, 1993–99. Population Studies. 2002b;56:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke TE. Himalayan households: Tamang demography and domestic processes. New York: Columbia University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, Thornton A, Yang LS. Helping out the kids: Expectations about parental support in young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:727–740. [Google Scholar]

- Guneratne UA. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Chicago: University of Chicago; 1994. The Tharus of Chitwan: Ethnicity, class and the state in Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung HB. Vignettes of Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: Sajha Prakashan; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Henretta JC, Hill MS, Li W, Sodo BJ, Wolf DA. Selection of children to provide care: The effect of earlier parental transfers. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Science. 1997;52:110–119. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelter LF, Axinn WG, Ghimire DJ. Social change, premarital nonfamily experiences, and marital dynamics. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:1131–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Eggebeen DJ, Clogg CC. The structure of intergenerational exchanges in American families. American Journal of Sociology. 1993;98:1428–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J, Ofstedal MB. Gender and aging in the developing world: Where are the men? Population and Development Review. 2003;29:677–698. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J, Saengtienchai C. Family care for rural elderly in the midst of rapid social change: The ease of Thailand. Social Change. 1996;26:98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J, Saengtienchai C, Sittitrai W. Living arrangements of the elderly in Thailand: Views of the populace. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1995;10:79–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00972032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Parish WL, Willis RJ. Sons, daughters, and intergenerational support in Taiwan. American Journal of Sociology. 1994;99:1010–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, Surkyn J. Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review. 1988;14:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Willis RJ. Motives for intergenerational transfers: Evidence from Malaysia. Demography. 1997;34:115–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG. The status of South Asia's growing elderly population. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1990a;5:93–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00116568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG. Changing intergenerational family relations in East Asia. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1990b;510:102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mason KO. Family change and support of the elderly in Asia: What do we know? Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 1992;7:13–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP, Niraula BB. Gender inequality and fertility in two Nepali villages. Population and Development Review. 1995;21:541–561. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry K, Schoeni RF. Transfer behavior within the family: Results from the asset and health dynamics study. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Science. 1997;52:S82–S92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofstedal MB, Reidy E, Knodel J. Gender differences in economic support and well-being of older Asians. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2004;19:165–201. doi: 10.1023/B:JCCG.0000034218.77328.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienta AM, Barber JS, Axinn WG. Patterns of social change and adult child-elderly parent coresidence: Evidence from Nepal; Unpublished manuscript presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pienta AM, Barber JS, Axinn WG. Social change and adult children's attitudes towards support of elderly parents: Evidence from Nepal. Hallym International Journal of Aging. 2001;3:211–235. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski M. Intergenerational relations in a context of industrial transition: A study of agricultural labor from migrants in Nang Rong, Thailand. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2008;23:17–38. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel BN, Shivakoti GP. Impact of development efforts on agricultural wage labor. Rural Poverty Paper 1. Winrock Kathmandu, Nepal: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Parrott TM, Bengtson VL. Factors that predispose middle-aged sons and daughters to provide social support to older parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:465–475. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Fricke TE. Social change and the family: Comparative perspectives from the West, China, and South Asia. Sociological Forum. 1987;2:746–779. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Lin HS. Social change and the family in Taiwan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population ageing 2009. New York: United Nations; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DA, Ballal SS. Family support for older people in an era of demographic change and policy constraints. Ageing & Society. 2006;26:693–706. [Google Scholar]

- Yabiku ST. The effect of non-family experiences on age of marriage in a setting of rapid social change. Population Studies. 2005;59:339–354. doi: 10.1080/00324720500223393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount KM, Agree EM. The power of older women and men in Egyptian and Tunisian Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:126–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QF. Economic transition and new patterns of parent-child coresidence in urban China. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:1231–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z, Kwong J. Family size and support of older adults in urban and rural China: Current effects and future implications. Demography. 2003;40:23–44. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]