SUMMARY

Photosynthetic efficiency of C3 plants suffers from the reaction of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) with O2 instead of CO2, leading to the costly process of photorespiration. Increasing the concentration of CO2 around Rubisco is a strategy used by photosynthetic prokaryotes such as cyanobacteria for more efficient incorporation of inorganic carbon. Engineering the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism, the carboxysome, into chloroplasts is an approach to enhance photosynthesis or to compartmentalize other biochemical reactions to confer new capabilities on transgenic plants. We have chosen to explore the possibility of producing β-carboxysomes from Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942, a model freshwater cyanobacterium. Using the agroinfiltration technique, we have transiently expressed multiple β-carboxysomal proteins (CcmK2, CcmM, CcmL, CcmO and CcmN) in Nicotiana benthamiana with fusions that target these proteins into chloroplasts and that provide fluorescent labels for visualizing the resultant structures. By confocal and electron microscopic analysis, we have observed that the shell proteins of the β-carboxysome are able to assemble in plant chloroplasts into highly organized assemblies resembling empty microcompartments. We demonstrate that a foreign protein can be targeted with a 17-amino-acid CcmN peptide to the shell proteins inside chloroplasts. Our experiments establish the feasibility of introducing carboxysomes into chloroplasts for potential compartmentalization of Rubisco or other proteins.

Keywords: β-carboxysome, synthetic biology, photosynthesis, CO2 concentration mechanism, chloroplast engineering, bacterial microcompartment, Nicotiana benthamiana

INTRODUCTION

Intracellular compartmentalization is a general strategy used by organisms to carry out metabolic reactions more efficiently. Several bacteria enclose enzymes within proteinaceous polyhedral bodies known as bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) (Bobik 2006, Yeates et al. 2008). These microcompartments allow the hosts to overcome unfavourable or challenging metabolic pathways by sequestering volatile or toxic reaction intermediates or concentrating a critical substrate nearby an enzyme that has a slow turnover and low affinity for that substrate. Despite their diverse functions, these microcompartments share a common set of homologous protein subunits, which make up the outer shells in a fashion similar to viral capsids (Yeates et al. 2011).

The β-carboxysome from the freshwater cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 is perhaps the best-characterized bacterial microcompartment. It contains two enzymes fundamental to photosynthesis, namely Rubisco (ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) and carbonic anhydrase, and forms an important part of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism (CCM) (Yeates, et al. 2008, Rae et al. 2013). Whilst essential to photosynthesis, Rubisco catalyses two competing reactions involving the enediol form of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP). These are the productive carboxylation of RuBP by CO2 and the wasteful oxygenation of RuBP by molecular oxygen, initiating photorespiration (Long 1991). Carboxysomes increase the concentration of CO2 around the catalytic site of Rubisco, promoting the carboxylase activity and consequently suppressing the undesired reaction with oxygen (Cannon et al. 2001, Price et al. 2008, Whitney et al. 2011).

A reasonable model for the arrangement of protein components in this β-carboxysome has been proposed (Rae, et al. 2013). The protein constituents of β-carboxysomes can be broadly classified as components involved in the formation of either the icosahedral shell or the internal structure. The shell is composed of multiple copies of single BMC domain proteins (Pfam00936) such as CcmK2, CcmK3 and CcmK4, and tandem BMC domain proteins (CcmO and CcmP), which contain two tandem repeats of BMC domains (Kinney et al. 2011, Yeates, et al. 2011). The crystal structures of single and tandem BMC proteins showed that they form hexameric and pseudo-hexameric units, respectively, which oligomerize forming the facets of the carboxysome shell (Kerfeld et al. 2005, Tanaka et al. 2009, Cai et al. 2013). Another component of the shell, CcmL, contains a Pfam03319 protein domain. The crystal structure revealed that CcmL is able to form pentamers and is thought to define the vertices between adjacent facets in the icosahedral shells (Tanaka et al. 2008, Keeling et al. 2014). These shell proteins are distinguished by their pores, which have different sizes and properties and are believed to regulate the flux of metabolites into and out of the carboxysome (Kinney, et al. 2011).

The proteins encoded by ccmM and ccmN participate in the internal organization of β-carboxysome. In S. elongatus, CcmM is present in two isoforms, a 58 kDa-isoform (CcmM58) and a shorter 35 kDa-isoform (CcmM35), which is synthesized from an internal ribosome entry site (Price et al. 1998, Long et al. 2005). CcmM58 has a C-terminal domain containing three copies of a protein domain similar to the small subunit of Rubisco (SSU-like domain) and an N-terminus similar to -carbonic anhydrase, while CcmM35 contains only three SSU-like domains (Price et al. 1993, Ludwig et al. 2000). CcmM58 localizes immediately below the shell and has been shown to interact with the shell proteins such as CcmK2 as well as the internal components such as CcmN, Rubisco and carbonic anhydrase (Cot et al. 2008, Long et al. 2010, Kinney et al. 2012). In contrast, CcmM35 is believed to be involved in the organization of Rubisco within the lumen of the β-carboxysome (Rae, et al. 2013). CcmN is another essential protein, which recruits the shell components to a nucleus of Rubisco complexes during the assembly of new carboxysomes (Cameron et al. 2013). The CcmN protein is characterized by the presence of an N-terminal domain, which interacts with CcmM58, and an approximately 20-amino-acid C-terminal peptide, which interacts with CcmK2 (Kinney, et al. 2012).

One possible strategy to enhance photosynthesis is to transfer components of a cyanobacterial CCM into the chloroplasts of C3 crops in order to increase photosynthetic carbon fixation and reduce photorespiration (Price et al. 2013, Zarzycki et al. 2013). A recent theoretical analysis estimated that engineering of carboxysome into chloroplasts in combination with the addition of a bicarbonate ion transporter and removal of stromal carbonic anhydrase could increase the crop yield by over 30% (McGrath and Long 2014). Despite the great potential of carboxysomes for improved carbon fixing efficiency in higher plants, there has been no report so far on the heterologous expression of proteins from the β-carboxysome or other BMCs in eukaryotic organisms.

In this work, we utilize a transient expression method to explore the possibility of transferring components of β-carboxysomes from Synechococcus PCC7942 into plant chloroplasts. Agroinfiltration of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves gave rise to high levels of protein expression, demonstrating that carboxysomal proteins can be produced in plant cells and correctly targeted into the chloroplast stroma when fused to a chloroplast transient peptide. Application of both fluorescence and transmission electron microscopy in combination with immunogold labelling enabled visualization of assemblies of carboxysomal proteins in the chloroplast stroma.

Results

All carboxysomal proteins expressed in this study were fused with the N-terminal chloroplast transit peptide from Arabidopsis recA gene (Kohler et al. 1997). Imaging analyses indicate that all the proteins were correctly targeted to chloroplast stroma.

Transient expression of CcmK2-YFP in N. benthamiana leaves

When yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged CcmK2 (CcmK2-YFP) was expressed and targeted to the chloroplasts of N. benthamiana, elongated structures were visualized by fluorescent microscopy (Figure 1a). Co-expression of CcmK2-YFP with other carboxysomal proteins did not alter these elongated fluorescent signals. We hypothesize that fusing YFP to the much smaller CcmK2 protein causes the CcmK2 subunits to assemble incorrectly, leading to these elongated structures and preventing proper interactions with other carboxysomal proteins. Hence, subsequent experiments were performed with CcmK2 lacking a YFP tag.

Figure 1.

Confocal image of N. benthamiana leaf cells transiently expressing stroma-targeted YFP-tagged β-carboxysomal shell proteins. (a) CcmK2-YFP by 35SS promoter. (b, c) CcmO-YFP by 35SS promoter. (d) CcmO-YFP by 35SS promoter and CcmL by ubiquitin-10 promoter. (e) CcmO-YFP by 35SS promoter and CcmK2 by ubiquitin-10 promoter. (f) CcmO-YFP by 35SS promoter, CcmK2 by ubiquitin-10 promoter and CcmL by ubiquitin-10 promoter. Green = YFP fluorescence. Red = chlorophyll autofluorescence. Bars (a–f) = 5 μm.

Transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves of CcmO, CcmK2, CcmL and CcmM58

When CcmO-YFP is targeted to chloroplasts, diffuse YFP signals were observed; alternatively, in some cases, polar aggregations were seen, probably due to very high protein levels (Figure 1b, c). We co-expressed CcmO-YFP with each of the other β-carboxysomal shell proteins, namely CcmK2, CcmK3, CcmK4 and CcmL. We found that only in the presence of CcmK2 was CcmO-YFP able to produce punctate fluorescent loci (Figure 1d, e), indicating the possible assembly of CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP. Punctate fluorescent signals were consistently produced when additional proteins such as CcmL and CcmM58 were co-expressed with CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP (Figure 1f).

In order to further resolve the structures formed by these punctate signals, the plant material was characterized at high resolution by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Two different protocols of preparation of plant tissue were used: conventional chemical fixation at room temperature; and high pressure freeze fixation (HPF)/freeze substitution in combination with immunogold labelling. In leaves expressing CcmO-YFP alone, large protein aggregates were observed (Figure 2a, d). Interestingly, when CcmO-YFP was expressed in combination with CcmK2, protein arrays organized into parallel linear structures were observed (Figure 2b, e). This result indicates that CcmO-YFP is not able to self-assemble into discrete structures, but when CcmK2 is present, the two carboxysomal proteins can interact, forming ordered assemblies – possibly sheets or stacked arrays of carboxysomal facets. Immunolabelling experiments using an anti-GFP antibody conjugated to 10nm gold supported the presence of carboxysomal proteins in these structures (Figure 2d, e).

Figure 2.

Electron micrograph of ultrathin sections of leaf mesophyll cells from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana expressing the indicated carboxysomal proteins: (a, d) CcmO-YFP; (b, e) CcmO-YFP and CcmK2; (c, f–i) CcmO-YFP, CcmK2 and CcmL-YFP. Images showing different structures within the chloroplast stroma: (a, d, black arrows) protein aggregates; (b, e, black arrows) protein aggregates organized in parallel line structures; (c, f–i, black arrows) circular structures resembling a carboxysome shell. (a–c) Leaf tissue prepared by normal chemical fixation. (d–i) leaf tissue prepared by high pressure freeze fixation (HPF) in combination with immunogold labelling: (d–g) GFP labelling; (h) CcmK2 labelling; (i) CcmO labelling. A secondary antibody conjugated with 10 nm gold particles was used for the labelling. (a–e) Bars = 500 nm; (f) bar = 1 μm; (g–i) bars = 200 nm; (detail panel c) bar = 50 nm; (detail panel e) bar = 100 nm; (detail panel f) bar = 200 nm.

When we expressed another component of the shell, CcmL-YFP, along with CcmO-YFP and CcmK2, circular structures were observed (Figure 2c, f–i). The same outcome was observed using either form of sample preparation, conventional chemical fixation or HPF fixation. Immunogold experiments using anti-GFP (Figure 2f, g), anti-CcmK2 (Figure 2h) and anti-CcmO (Figure 2i) antisera confirmed the presence of CcmO and CcmK2 in these circular structures.

A size determination and a schematic representation of these structures are illustrated in Figure 3. They are round and slightly elongated, but some angular structures have been observed in high quality plant material fixed by high pressure freezing (Figure 2g). They measure 100–110 nm in length and 80–90 nm in width. These carboxysome-like structures are surrounded by a double shell with a space in between. The external shell measures about 5–6 nm in thickness, which is a value similar to that reported for a β-carboxysome shell (Kaneko et al. 2006). In contrast, the structure of the second shell is difficult to resolve since it appears less thick and disorganized. An inner cavity surrounded by the double shell constitutes the internal part of the circular structure.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic representation of a circular structure. (b) High magnification of a circular structure in the chloroplast stroma of a mesophyll cell from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana expressing CcmO-YFP, CcmK2 and CcmL-YFP. Leaf tissue prepared by normal chemical fixation. Bar = 50 nm.

In the same plant material (expressing CcmO-YFP, CcmK2, and CcmL-YFP), other types of structures were observed as well as the round structures described above (Figure 4). Elongated (Figure 4a, d) and disorganized structures (Figure 4b, e) were observed, which probably result from different ratios of carboxysomal proteins (CcmO-YFP, CcmK2 and CcmL-YFP), the proportions of which are likely to be heterogeneous within agroinfiltrated leaves. The presence of structures that are intermediate between a round and elongated shape, may also reflect the importance of having an optimal ratio of carboxysomal proteins for carboxysome biogenesis (Figure 4c, f).

Figure 4.

Electron micrograph of ultrathin sections of leaf mesophyll cells from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana expressing CcmO-YFP, CcmK2 and CcmL-YFP. Images showing different structures into the chloroplast stroma: (a, d, black arrows) elongated structures; (b, e, black arrows) disorganized structures; (c, f, black arrows) intermediate structures. (a–c) Leaf tissue prepared by normal chemical fixation. (d–f) Leaf tissue prepared by high pressure freeze fixation (HPF) in combination with immunogold labelling. An antibody against GFP and a secondary antibody conjugated with 10 nm gold particles were used. (a, d) Bars = 1 μm; (b, c, f) bars = 200 nm; (e) bar = 500 nm; (detail panel a, d) bars = 200 nm.

In plant material expressing CcmM58-YFP in combination with CcmO-YFP and CcmK2, round structures were observed (Figure 5a). Immunolabelling experiments using antibodies against GFP (Figure 5b), CcmK2 (Figure 5c), CcmO (Figure 5d), and CcmM58 (Figure 5e) confirmed the presence of all these proteins. This result supports the interpretation that sheets of CcmO-YFP/CcmK2 proteins form complex structures in the presence of CcmM58. In addition to the round structures, elongated structures were observed in some chloroplasts in plants agroinfiltrated with constructs expressing CcmM58-YFP, CcmO-YFP and CcmK2 (Figure 5f, g). The elongated structures were organized into semicrystalline arrays of parallel lines spaced 8–9 nm, which intersect forming a net structure (Figure 5f, g). A similar organization of carboxysomal proteins in β-carboxysomes has been described by others (Kaneko, et al. 2006). Immunolabelling experiments using antibodies against GFP, CcmK2, CcmO and CcmM58 also confirmed the presence of these carboxysomal proteins in elongated structures (Figure S1).

Figure 5.

Electron micrograph of ultrathin sections of leaf mesophyll cells from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana expressing the indicated carboxysomal proteins: (a–g) CcmO-YFP, CcmK2 and CcmM58-YFP; (h, i) CcmO-YFP, CcmK2, CcmL and CcmM58-YFP. (a–e, h, black arrows) Images showing circular structures resembling a carboxysome shell; (f, g, i, black arrows) images showing elongated structures (parallel lines spaced 8–9 nm and organized forming a net structure are indicated). Leaf tissue prepared by high pressure freeze fixation without immunogold labelling (a, f), and in combination with immunogold labelling (b–e, g–i). Different antibodies against carboxysomal proteins were used: (b, g–i) GFP labelling; (c) CcmK2 labelling; (d) CcmO labelling; (e) CcmM58 labelling. A secondary antibody conjugated with 10 nm gold particles was reacted with the primary antibodies. (a) Bar = 100 nm; (b–e, g–i) bars = 200 nm; (f) bar = 50 nm.

In plant material expressing CcmO-YFP, CcmK2, CcmL, and CcmM58-YFP together, we observed the same type of carboxysome-like and elongated structures described for the CcmO-YFP, CcmK2, and CcmM58-YFP plant material (Figure 5h, i). Immunolabelling experiments with an anti-GFP antibody supported the presence of the carboxysomal proteins.

CcmN contains a 17-amino-acid peptide that can target YFP to the structures formed by CcmK2/CcmO-YFP

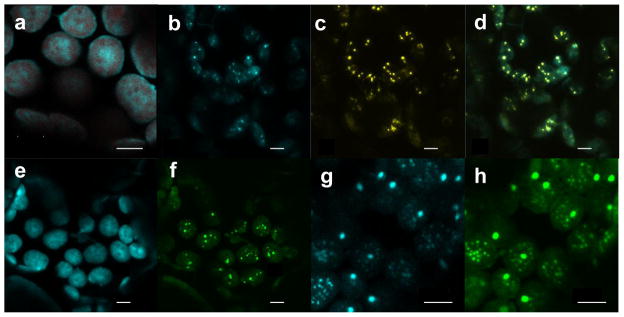

We also co-expressed CcmN, an internal protein of β-carboxysomes, with CcmK2 and CcmO. When expressed alone, CcmN-CFP gave diffuse CFP signals (Figure 6a). When CcmN-CFP was co-expressed with CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP, both CcmN-CFP and CcmO-YFP gave punctate signals, which co-localized to the same areas in chloroplasts, suggesting that CcmN was able to associate with the structures composed of CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP (Figure 6b–d). When we removed the C-terminal 17 amino-acid peptide of CcmN and fused the truncated CcmN to CFP, the resulting protein fusion, CcmNd17-CFP, no longer co-localized with the punctate structures of CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP (Figure 6e, f). This finding is consistent with a recent report that demonstrated that CcmN interacts with CcmK2 through its C-terminal 17 amino-acid peptide (CcmN17) (Kinney, et al. 2012).

Figure 6.

Confocal image of N. benthamiana leaf cells transiently expressing stroma-targeted CcmK2, CcmO and CcmN to determine co-localization. (a) CcmN-CFP by 35SS promoter. CFP fluorescence is shown in cyan and chlorophyll autofluorescence in red. (b–d) CcmN-CFP by 35SS promoter, CcmK2 by ubiquitin-10 promoter and CcmO-YFP by MAS promoter. Individual CFP (b, in cyan) and YFP (c, in yellow) channels as well as the merged channel (d, CFP in cyan and YFP in yellow) from the same region are shown. (e, f) CcmNd17-CFP by 35SS promoter, CcmK2 by ubiquitin-10 promoter and CcmO-YFP by MAS promoter. Individual CFP (e, in cyan) and YFP (f, in green) channels of the same leaf section are shown. (g, h) CcmO-CFP by 35SS promoter, CcmK2 by MAS promoter and YFP-CcmN17 by ubiquitin-10 promoter. Individual CFP (g, in cyan) and YFP (h, in green) channels of the same leaf section are shown. Bars (a–h) = 5 μm.

In order to test the ability of the CcmN17 peptide to target a foreign protein to the structures formed by CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP, we co-expressed CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP with CcmN17-CFP, where the CFP was fused to the C-terminus of CcmN17. But the CcmN17-CFP fluorescent signals were diffuse and did not co-localize with the punctate signals of CcmO-YFP (Figure S2). We hypothesize that either the CFP fused to the C-terminus of CcmN17, or the 15 amino-acid scar peptide that remained at the N-terminus of CcmN17 after the truncation of the chloroplast transit peptide, interfered with the interaction between CcmN17 and CcmK2. When we fused the CTP-YFP to the N-terminus of CcmN17 and co-expressed it with CcmK2 and CcmO-CFP, both YFP-CcmN17 and CcmO-CFP fluorescent signals co-localized to punctate spots within chloroplasts (Figures 6g–h). Thus, the C-terminal 17 amino-acid peptide of CcmN (CcmN17) is critical for the binding of CcmN to the structures of CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP, and the CcmN17 peptide by itself is enough to target a foreign protein to the shell proteins of β-carboxysomes. However, we were not able to observe by TEM the formation of any specific structures in the leaf tissues expressing CcmN or CcmN17 with CcmK2 and CcmO (Figure S3).

Discussion

In this study, we used the well-established agroinfiltration technique to express transiently several protein components of the β-carboxysome in chloroplasts of N. benthamiana. We fused several of these proteins with YFP or CFP, which allowed us to monitor the formation of protein assemblies at the resolution of visible light. We found that fusing YFP to a much smaller shell protein of β-carboxysome, CcmK2, gave rise to elongated structures and co-expressing it with other shell proteins did not seem to alter these elongated structures. CcmK2 is the major shell component of β-carboxysomes and has a high tendency to self-polymerize (Samborska and Kimber 2012). YFP fusion likely causes distortion in the assembly of CcmK2 subunits, leading to the artificial elongated structures, and prevents CcmK2 from proper interactions with other carboxysomal proteins. It was recently reported that CcmK2-YFP by itself could not substitute for the native unlabelled protein in the ΔccmK2 cyanobacterial strain, and it could only interact with other carboxysomal components in presence of the unlabelled CcmK2 (Cameron, et al. 2013). Thus, the subsequent experiments were carried out without YFP fused to CcmK2. Although we did not observe any interference with the proper protein-protein interactions with YFP fused to other components such as CcmO and CcmM58, we should caution that such fusions might disrupt other structural or functional aspects of β-carboxysomes. Fluorescent protein-labelled CcmK4 and RbcL in previous studies did not disrupt the structure or function of carboxysomes as long as unlabelled versions were also present (Cameron, et al. 2013, Chen et al. 2013).

Large protein aggregates, probably due to non-specific interactions, were observed in agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaves expressing the fluorescently tagged carboxysome shell protein, CcmO-YFP, while co-expression of CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP gave rise to more organized, parallel structures. CcmO and CcmK2 are presumably the main components in the formation of the faces of the carboxysome shell (Rae et al. 2012). Evidently CcmO-YFP alone is not able to self-assemble in a recognisable fashion, but in the presence of CcmK2, the two proteins can polymerize to form sheets which could represent arrays of shell faces. This finding is in agreement with a recent report suggesting that CcmO was unable to assemble with other components in the absence of CcmK2 (Cameron, et al. 2013).

When we added CcmL-YFP, the component involved in the formation of vertices of carboxysome shells (Tanaka, et al. 2008), round structures resembling carboxysome shells were observed. This result supports the notion that CcmL provides the requisite curvature for the formation of the icosahedral structure of the carboxysome and is in line with a recent work suggesting that CcmK2, CcmO and CcmL constitute the minimal structural determinants of β-carboxysome’s outer shells (Rae, et al. 2012). Circular structures that we observed in chloroplasts appear to be defined by a double shell, which contains an internal cavity. Probably the presence of a double shell represents a thermodynamically stable conformation of a combination of CcmO-YFP, CcmK2, CcmL-YFP in the absence of the other internal components such as cyanobacteria Rubisco. Indeed, CcmK2 has recently been shown to form a double-layered shell in the absence of other protein components (Samborska and Kimber 2012).

These carboxysome-like structures are more frequently round and smaller than a normal β-carboxysome shell, but in some cases, internal angular structures have been observed in particularly well preserved plant preparations observed using the HPF fixation technique (Figure 2g). The oval shaped structures measure 100–110 nm in length and 80–90 nm in width, whereas the diameter of a β-carboxysome from Synechococcus PCC7942 is ~175 nm (Rae, et al. 2013). The smaller size and less-angular architecture of the outer shell are probably due to the absence of other important components of the shell and of the carboxysome interior. It has been demonstrated recently that cyanobacterial Rubisco plays a central role in carboxysome nucleation, together with the two isoforms of CcmM, during the biogenesis of β-carboxysomes (Cameron, et al. 2013, Chen, et al. 2013). Only after nucleation does the shell form around this ‘procarboxysome’ via interactions with CcmN, which links the shell to the internal parts (Cameron, et al. 2013). This recently uncovered assembly process distinguishes β-carboxysome from other bacterial microcompartments such as α-carboxysome and propanediol utilization metabolosome, which are generally known to be able to form empty compartments in the absence of lumen proteins (Menon et al. 2008, Parsons et al. 2010, Choudhary et al. 2012). Nevertheless, CcmK2 at high concentration levels was able to form well-defined bodies ranging from 100 to 300 nm in size and could interact with CcmL in vitro (Keeling, et al. 2014). The spherical structures observed in this study are more uniform in size and appear more organized likely due to the presence of additional components such as CcmO and CcmM58.

In N. benthamiana leaves expressing the three carboxysomal proteins CcmO-YFP, CcmK2, and CcmL-YFP, elongated structures and disorganized structures (Figures 5h–i and S1d–f) were also observed. These are probably the result of different ratios of the three carboxysomal proteins. The amount of each protein expressed transiently from T-DNA will vary in different cells, depending on how much T-DNA from each strain enters the cell as well as how much RNA is transcribed and translated. Furthermore, different carboxysomal proteins may vary in stability. We speculate that elongated structures are due to the result of CcmO-YFP and CcmK2 polymerization in the presence of sub-optimal amounts of CcmL. In contrast, perhaps when CcmL is present at an appropriate concentration, carboxysome-like structures can be formed. This result is supported by studies performed in cyanobacteria where elongated carboxysomes were observed in ccmL mutants (Cai et al. 2009, Cameron, et al. 2013). Our data indicate that proper levels of expression of the different carboxysome proteins from stably integrated genes will be essential for formation of carboxysomes with structures akin to those observed in cyanobacteria.

Overexpression of carboxysomal proteins as well as absence of sufficient expression can also be inimical to the formation of proper microcompartments. Even when combinations of carboxysomal proteins gave rise to more than one type of structure, only a single morphological type was observed in each chloroplast, probably due to the particular level of expression of the carboxysomal proteins in each chloroplast. Elongated and disorganized structures were observed only in what appeared to be ‘sick’ chloroplasts (those with unusual chloroplast morphology). The circular, carboxysome-like structures were observed more frequently in chloroplast with characteristic chloroplast morphology - probably due to a suitable level of expression of carboxysomal proteins.

We also observed round structures and elongated structures in plant material expressing CcmO-YFP, CcmK2, and CcmM58-YFP. These results raise two interesting issues. First, it suggests there is direct interaction between CcmM58 and the shell formed by CcmK2 and CcmO since it is likely that such interaction gives the driving force to organize CcmO-YFP/CcmK2 sheets into round structures. This finding should not be surprising since a previous yeast two hybrid experiment suggested the binding of CcmK2 to CcmM58 (Cot, et al. 2008). However, CcmN, which is also known to interact with CcmM58, has been shown to bind CcmK2 through a short C-terminal peptide and is essential for recruiting the shell to the aggregation of Rubisco complexes with other components (Kinney, et al. 2012, Cameron, et al. 2013). If the CcmN is the main protein bridging the shell with other internal components, the interaction between CcmK2 and CcmM58 seems redundant. It is also possible that the lack of other stronger binding partners such as Rubisco, carbonic anhydrase and CcmN enables CcmM58 to interact with CcmK2. Second, although CcmL seems to play an essential role in the formation of circular microcompartments when it is co-expressed with CcmK2 and CcmO, it is not necessary when CcmM58 is also present. CcmL is believed to occupy the vertices of icosahedral shaped carboxysomes and the mostly elongated structures observed in the ΔccmL cyanobacteria supported such a role for CcmL (Cameron, et al. 2013). However, in the case of α-carboxysomes, the deletion of CcmL homologues did not disrupt their shapes (Cai, et al. 2009). Our results highlight the heterogeneity of structures that can arise from missing components. Since most of the internal components were absent in our samples, it is possible that the structures observed arise from an assembly process completely different from a natural one.

Interestingly, we could not detect either round structures or elongated assemblies in the samples co-expressing CcmN or CcmN17 with CcmK2 and CcmO. Although the fluorescence fusions indicated that CcmN and CcmN17 are able to co-localize with these shell proteins, the lack of formation of any specific structure suggests that CcmN by self cannot arrange the shell components into more organized structures without CcmM58 or CcmL.

Bacterial microcompartments, including carboxysomes, have been proposed for biotechnological applications in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering due to their unique abilities to enclose specific enzymatic pathways (Corchero and Cedano 2011, Frank et al. 2013). Short N-terminal peptides from several internal components of propanediol utilization microcompartment (Pdu MCP) from Salmonella enterica have been demonstrated to be able to encapsulate foreign proteins such as GFP, glutathione S-transferase and maltose-binding protein within Pdu MCP (Fan et al. 2010, Fan and Bobik 2011, Fan et al. 2012). A similar shell-targeting signal sequence was also reported to target EGFP and β-galactosidase to the recombinant ethanolamine utilization (eut) bacterial microcompartment shell proteins expressed in E. coli (Choudhary, et al. 2012). Recently, a homologous 17-amino-acid peptide located at the C-terminus of CcmN has been identified that can interact with CcmK2 in a similar fashion (Kinney, et al. 2012). Here, we showed that CcmN was able to co-localize with CcmK2 and CcmO-YFP in chloroplasts through the same C-terminal peptide (CcmN17). In addition, our work also demonstrates that the CcmN17 signal sequence alone is able to cause co-localization of a foreign protein, YFP, with the carboxysomal shell proteins, CcmK2 and CcmO, inside the chloroplasts. The results in our study present an exciting potential of β-carboxysome shells for synthetic biology and biotechnological applications in higher plants.

The current work describes recombinant heterologous expression of β-carboxysomal proteins in higher plant chloroplasts. Previously, the propanediol utilization microcompartment from Citrobacter freundii and ethanolamine utilization microcompartment from Salmonella enterica have been successfully engineered in E. coli (Parsons et al. 2008, Parsons, et al. 2010, Choudhary, et al. 2012). Bonacci et al. heterologously produced α-carboxysome from Halothiobacillus neapolitanus in E. coli and demonstrated that the recombinant microcompartments were capable of fixing CO2 (Bonacci et al. 2012). By expressing CcmO-YFP and CcmK2 in combination with CcmL-YFP and/or CcmM58-YFP, we observed discrete structures with characteristics similar to β-carboxysomes. Therefore, this work provides evidence that specific combinations of carboxysomal proteins can assemble within the chloroplast stroma. These experiments are the first step towards the expression of a complete cyanobacterial carboxysome-based carbon-concentrating mechanism in vascular plants, in order to enhance photosynthetic performance.

Experimental Procedures

Plant expression vector construction

The Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 ccmK2, ccmL and ccmO genes were amplified from E. coli expression vectors containing the respective coding regions, kindly provided by Cheryl Kerfeld (Michigan State University). Synthetic ccmN, ccmM58, ccmK3, ccmK4 and yfp genes, designed to mimic the codon usage of chloroplast protein expression system, were synthesized by Bioneer Inc. (Alameda, CA). Each carboxysomal gene was fused with the chloroplast transit peptide (ctp) from Arabidopsis recA gene (Kohler, et al. 1997).

Table S1 contains the primers used in the overlap extension PCR procedure (Horton et al. 1989) to generate the ctp::ccm gene fusion constructs with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific). The PCR products were first cloned into pCR8/GW/TOPO TA vector (Life Technologies) and subsequently transferred to the pEXSG-YFP Gateway destination vector, which has the tandem CaMV 35S promoter (P35SS) and the YFP or CFP gene placed 5′ and 3′ of the Gateway recombination cassette respectively (Jakoby et al. 2006), through a standard LR recombination reaction. Thus, each resulting vector contains a carboxysomal gene driven by P35SS and fused to the YFP or CFP gene at the 3′ end as shown in Figure S4a.

In order to express 1–2 additional carboxysomal genes from single vectors, nuclear expression operons driven by ubiquitin-10 (Puq10) and MAS (Pmas) promoters (Langridge et al. 1989, Grefen et al. 2010) were constructed with the overlap extension PCR procedure using the primers listed in Table S1. These operons were then inserted into the AscI site located 5′ of the tandem CaMV 35S promoter in the pEXSG-YFP vectors (Figure S4b). The attB2 segment located between the carboxysomal gene and YFP or CFP gene in these vectors gives rise to a 15-amino-acid Gateway linker peptide (KGEFDPAFLYKVVDG) upon translation, which should provide sufficient separation between the carboxysomal protein domains and the fluorescent domain. In operons driven by the ubiquitin-10 or MAS promoter, we added 9- or 12-amino-acid flexible linker peptide made up of GGS repeats between the YFP and carboxysomal proteins in order to minimize the influence of the YFP fusion on the molecular interactions among carboxysomal proteins. The expression vectors created in this work and their features are summarized in Table 1. The YFP and CFP used in this study are EYFP and mCerulean versions and their amino-acid sequences are included in the supplemental information section.

Table 1.

The plant expression vectors with β-carboxysomal genes created in this study

| Vectors | Promoters# and proteins to be expressed |

|---|---|

| pEXSG-K2-YFP | P35SS – CcmK2-YFP |

| pEXSG-O-YFP | P35SS – CcmO-YFP |

| pEXSG-L-YFP | P35SS – CcmL-YFP |

| pEXSG-M58-YFP | P35SS – CcmM58-YFP |

| pEXSG-O-YFP -UK2 | P35SS – CcmO-YFP, Puq10 – CcmK2 |

| pEXSG-O-YFP -UL | P35SS – CcmO-YFP, Puq10 – CcmL |

| pEXSG-O-YFP -UK3 | P35SS – CcmO-YFP, Puq10 – CcmK3 |

| pEXSG-O-YFP -UK4 | P35SS – CcmO-YFP, Puq10 – CcmK4 |

| pEXSG-O-YFP -UK2-UL | P35SS – CcmO-YFP, Puq10 – CcmK2, Puq10 – CcmL |

| pEXSG-N-CFP | P35SS – CcmN-CFP |

| pEXSG-N-CFP-UK2-PmO-YFP | P35SS – CcmN-CFP, Puq10 – CcmK2, Pmas – CcmO-YFP |

| pEXSG-Nd17-CFP-UK2-PmO-YFP | P35SS – CcmNd17-CFP, Puq10 – CcmK2, Pmas – CcmO-YFP |

| pEXSG-N17-CFP-PmK2-UO-YFP | P35SS – CcmN17-CFP, Pmas – CcmK2, Puq10 – CcmO-YFP |

| pEXSG-YFP-N17 | P35SS – YFP-CcmN17 |

| pEXSG-O-CFP-PmK2-UYFP-N17 | P35SS – CcmO-CFP, Pmas – CcmK2, Puq10 – YFP-CcmN17 |

| pEXSG-YFP-N17-UO-PmK2 | P35SS – YFP-CcmN17, Puq10 – CcmO, Pmas – CcmK2 |

| pEXSG-YFP-Nd17-UO-PmK2 | P35SS – YFP-CcmNd17, Puq10 – CcmO, Pmas – CcmK2 |

P35SS – tandem 35S promoter, Puq10 – ubiquitin-10 promoter, Pmas – MAS promoter

Each expression vector was electroporated into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101/pMP90RK (Koncz and Schell 1986) and transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing carbenicillin, kanamycin and gentamycin.

Transient expression of carboxysomal proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana

For transient expression of carboxysomal proteins in N. benthamiana leaf tissues, agroinoculation was performed as described previously (Sparkes et al. 2006). About 5 ml of each agrobacterial culture grown to the late log phase was pelleted, re-suspended in 10 mM MES pH 5.6 buffer with 10 mM MgCl2 and 150 uM acetosyringone to an optical density of 0.3–0.5 and incubated in the dark at 28 degree C for 2–5 h. Leaves from 4–6 week-old N. benthamiana plants grown at 10 hours of light per day at ~ 50 μmoles/m2/s of light intensity at around 22 degree C were infiltrated with the agrobacterial suspension on the abaxial side using a needle-less syringe. In some cases, suspension of agrobacteria carrying the gene for the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV) was also co-infiltrated to improve the expression levels and duration of carboxysomal proteins (Voinnet et al. 2003). Within 2–4 days after agroinfiltration, the leaf tissues were examined with a confocal microscope or fixed for immunogold labelling and transmission electron microscopy as described below.

Confocal microscopy

Laser scanning confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope through a 25X multi-immersion objective. The 458, 488 and 514 nm lines of an argon laser were used to excite CFP, chlorophyll and YFP respectively. All the imaging experiments were carried out in sequential mode in order to minimize the spectral bleed-through from undesired fluorophores. The images were collected and processed with either Zen 2009 or 2010 microscope software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany).

Chemical fixation, dehydration and embedding

Sections of leaf tissue 2 × 2mm were excised from leaves using a sterile razor blade and incubated in primary fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.05M phosphate buffer pH 7.2) for 2 hours in low vacuum, over ice with rotation. The samples were washed three times in 0.05M phosphate buffer pH 7.2 and then incubated in the second fixative (1% osmium tetroxide in 0.05M phosphate buffer pH 7.2) for 4 hours over ice with rotation. The tissue was washed in 0.05M phosphate buffer pH 7.2 to remove all trace of osmium tetroxide and dehydrated through an acetone series 30% – 50% – 70% – 90% (v/v) acetone in water (10 minutes each incubation) and then three times in 100% dry acetone (30 minutes each incubation) all at room temperature. Finally the samples were embedded through increasing concentration of Spürr resin (TAAB) from 30%–50%–70% to 100% v/v of resin in acetone and then polymerized overnight at 60°C (Hulskamp et al. 2010).

Cryofixation using a high pressure freezer, freeze substitution and embedding

5 mm disks of leaf tissue were taken using a punch and then incubated in 150 mM sucrose for 8 minutes under low vacuum, in order to fill the intercellular spaces. The disks were transferred to the cavity of a specimen carrier (type B planchettes, Leica Microsystems) pre-coated with 1-hexadecene and containing 150 mM sucrose as cry-protectant. The flat side of a second carrier was used as a lid. This plant material was then cryo-fixed using a high pressure freezer unit (Leica Microsystems EM HPM100).

For the second step of freeze substitution, the high pressure frozen tissue was transferred to 5 ml plastic pots containing a solution of 0.5% uranyl acetate in dry acetone pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The freeze substitution process was carried out in an EM AFS unit (Leica Microsystems) at −85°C for 48 hours and then linear warm up to −60°C for 5 hours. After 1 hour samples were washed using dry ethanol to remove all trace of uranyl acetate. The samples were then infiltrated at low temperature using Lowicryl HM20 resin (Polysciences). This step was performed at −60°C by increasing the concentration of resin, from 30%–50%–70% to 100% v/v HM20 in dry ethanol, with 1 hour for each incubation. Finally the samples were transferred to aluminium moulds and polymerized at −50°C for 24 hours using an UV lamp (Hillmer et al. 2012).

Immunogold labelling

Ultrathin sections (60–90nm) were cut from the polymerised blocks on a Reichert-Jung Ultrmicrotome and collected on gold grids. These were incubated in blocking solution (1% w/v BSA in PBS buffer) for 1 hour and then treated for 1 hour with a blocking solution containing the primary antibody. Different primary antibodies against GFP (abcam, rabbit polyclonal to GFP) and different carboxysomal proteins were tested: rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CcmK2, CcmO, CcmM, CcmN and cyanobacteria Rubisco (produced by CRB, Cambridge Research Biochemicals). The grids carrying the sections were washed three times in blocking solution and then incubated for 1 hour in blocking solution containing a secondary antibody conjugated with 10 nm gold particles (abcam, goat polyclonal antibody to rabbit IgG, 10 nm gold conjugated). The excess of secondary antibody was removed washing three times in blocking solution and then washing three times in distilled water.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Grids carrying ultrathin sections of both embedded samples, cryo-fixed and chemically fixed, were post strained using 2 % (w/v) aqueous solution of uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Images were obtained using a transmission electron microscope JEM 2011 FasTEM Jeol UK operating at 200kV, equipped with a Gatan Ultrascan 1000 CCD camera and a Gatan Dual Vision 300 CCD camera.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Cheryl Kerfeld for providing us with vectors harboring ccmK2, ccmL and ccmO genes and the genomic DNA extracted from Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number (EF-1105584) to M.R.H., Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council under Grant Number (BB/I024488/1) to M.A.J.P. and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number (F32GM103019) to M.T.L.

References

- Bobik TA. Polyhedral organelles compartmenting bacterial metabolic processes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;70:517–725. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacci W, Teng PK, Afonso B, Niederholtmeyer H, Grob P, Silver PA, Savage DF. Modularity of a carbon-fixing protein organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:478–483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108557109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F, Menon BB, Cannon GC, Curry KJ, Shively JM, Heinhorst S. The pentameric vertex proteins are necessary for the icosahedral carboxysome shell to function as a CO2 leakage barrier. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F, Sutter M, Cameron JC, Stanley DN, Kinney JN, Kerfeld CA. The structure of CcmP, a tandem bacterial microcompartment domain protein from the b-carboxysome, forms a subcompartment within a microcompartment. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:16055–16063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.456897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JC, Wilson SC, Bernstein SL, Kerfeld CA. Biogenesis of a bacterial organelle: the carboxysome assembly pathway. Cell. 2013;155:1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon GC, Bradburne CE, Aldrich HC, Baker SH, Heinhorst S, Shively JM. Microcompartments in prokaryotes: carboxysomes and related polyhedra. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5351–5361. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5351-5361.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AH, Robinson-Mosher A, Savage DF, Silver PA, Polka JK. The bacterial carbon-fixing organelle is formed by shell envelopment of preassembled cargo. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary S, Quin MB, Sanders MA, Johnson ET, Schmidt-Dannert C. Engineered protein nano-compartments for targeted enzyme localization. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corchero JL, Cedano J. Self-assembling, protein-based intracellular bacterial organelles: emerging vehicles for encapsulating, targeting and delivering therapeutical cargoes. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10:92. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cot SS, So AK, Espie GS. A multiprotein bicarbonate dehydration complex essential to carboxysome function in cyanobacteria. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:936–945. doi: 10.1128/JB.01283-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CG, Bobik TA. The N-terminal region of the medium subunit (PduD) packages adenosylcobalamin-dependent diol dehydratase (PduCDE) into the Pdu microcompartment. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5623–5628. doi: 10.1128/JB.05661-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CG, Cheng SQ, Liu Y, Escobar CM, Crowley CS, Jefferson RE, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Short N-terminal sequences package proteins into bacterial microcompartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7509–7514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913199107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CG, Cheng SQ, Sinha S, Bobik TA. Interactions between the termini of lumen enzymes and shell proteins mediate enzyme encapsulation into bacterial microcompartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14995–15000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207516109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Lawrence AD, Prentice MB, Warren MJ. Bacterial microcompartments moving into a synthetic biological world. J Biotechnol. 2013;163:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefen C, Donald N, Hashimoto K, Kudla J, Schumacher K, Blatt MR. A ubiquitin-10 promoter-based vector set for fluorescent protein tagging facilitates temporal stability and native protein distribution in transient and stable expression studies. Plant J. 2010;64:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillmer S, Viotti C, Robinson DG. An improved procedure for low-temperature embedding of high-pressure frozen and freeze-substituted plant tissues resulting in excellent structural preservation and contrast. J Microsc. 2012;247:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2011.03595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes - gene-splicing by overlap extension. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulskamp M, Schwab B, Grini P, Schwarz H. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of plant tissues. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010;2010:pdb prot4958. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby MJ, Weinl C, Pusch S, Kuijt SJ, Merkle T, Dissmeyer N, Schnittger A. Analysis of the subcellular localization, function, and proteolytic control of the Arabidopsis cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor ICK1/KRP1. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1293–1305. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.081406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Danev R, Nagayama K, Nakamoto H. Intact carboxysomes in a cyanobacterial cell visualized by hilbert differential contrast transmission electron microscopy. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:805–808. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.805-808.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling TJ, Samborska B, Demers RW, Kimber MS. Interactions and structural variability of b-carboxysomal shell protein CcmL. Photosynth Res. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-9973-z. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerfeld CA, Sawaya MR, Tanaka S, Nguyen CV, Phillips M, Beeby M, Yeates TO. Protein structures forming the shell of primitive bacterial organelles. Science. 2005;309:936–938. doi: 10.1126/science.1113397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JN, Axen SD, Kerfeld CA. Comparative analysis of carboxysome shell proteins. Photosynth Res. 2011;109:21–32. doi: 10.1007/s11120-011-9624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JN, Salmeen A, Cai F, Kerfeld CA. Elucidating essential role of conserved carboxysomal protein CcmN reveals common feature of bacterial microcompartment assembly. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17729–17736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler RH, Cao J, Zipfel WR, Webb WW, Hanson MR. Exchange of protein molecules through connections between higher plant plastids. Science. 1997;276:2039–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koncz C, Schell J. The promoter of TL-DNA gene 5 controls the tissue-specific expression of chimaeric genes carried by a novel type of Agrobacterium binary vector. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:383–396. [Google Scholar]

- Langridge WHR, Fitzgerald KJ, Koncz C, Schell J, Szalay AA. Dual promoter of Agrobacterium tumefaciens mannopine synthase genes is regulated by plant-growth hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3219–3223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long BM, Price GD, Badger MR. Proteomic assessment of an established technique for carboxysome enrichment from Synechococcus PCC7942. Can J Bot. 2005;83:746–757. [Google Scholar]

- Long BM, Tucker L, Badger MR, Price GD. Functional cyanobacterial b-Carboxysomes have an absolute requirement for both long and short forms of the CcmM protein. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:285–293. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP. Modification of the response of photosynthetic productivity to rising temperature by atmospheric CO2 concentrations: Has its importance been underestimated? Plant Cell Environ. 1991;14:729–739. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig M, Sültemeyer D, Price GD. Isolation of ccmKLMN genes from the marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 (Cyanophyceae), and evidence that CcmM is essential for carboxysome assembly. J Phycol. 2000;36:1109–1119. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JM, Long SP. Can the cyanobacterial carbon-concentrating mechanism increase photosynthesis in crop species? A theoretical analysis. Plant Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1104/pp.113.232611. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon BB, Dou Z, Heinhorst S, Shively JM, Cannon GC. Halothiobacillus neapolitanus carboxysomes sequester heterologous and chimeric RubisCO species. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JB, Dinesh SD, Deery E, Leech HK, Brindley AA, Heldt D, Frank S, Smales CM, Lunsdorf H, Rambach A, Gass MH, Bleloch A, McClean KJ, Munro AW, Rigby SEJ, Warren MJ, Prentice MB. Biochemical and structural insights into bacterial organelle form and biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14366–14375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JB, Frank S, Bhella D, Liang MZ, Prentice MB, Mulvihill DP, Warren MJ. Synthesis of empty bacterial microcompartments, directed organelle protein incorporation, and evidence of filament-associated organelle movement. Mol Cell. 2010;38:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR, Woodger FJ, Long BM. Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:1441–1461. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Howitt SM, Harrison K, Badger MR. Analysis of a genomic DNA region from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus Sp strain PCC7942 involved in carboxysome assembly and function. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2871–2879. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2871-2879.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Pengelly JJL, Forster B, Du JH, Whitney SM, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR, Howitt SM, Evans JR. The cyanobacterial CCM as a source of genes for improving photosynthetic CO2 fixation in crop species. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:753–768. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Sultemeyer D, Klughammer B, Ludwig M, Badger MR. The functioning of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in several cyanobacterial strains: a review of general physiological characteristics, genes, proteins, and recent advances. Can J Bot. 1998;76:973–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Rae BD, Long BM, Badger MR, Price GD. Structural determinants of the outer shell of b-carboxysomes in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942: Roles for CcmK2, K3-K4, CcmO, and CcmL. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae BD, Long BM, Badger MR, Price GD. Functions, compositions, and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: Polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:357–379. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00061-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samborska B, Kimber MS. A dodecameric CcmK2 structure suggests b-carboxysomal shell facets have a double-layered organization. Structure. 2012;20:1353–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes IA, Runions J, Kearns A, Hawes C. Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2019–2025. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Kerfeld CA, Sawaya MR, Cai F, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Yeates TO. Atomic-level models of the bacterial carboxysome shell. Science. 2008;319:1083–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1151458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Sawaya MR, Phillips M, Yeates TO. Insights from multiple structures of the shell proteins from the b-carboxysome. Protein Sci. 2009;18:108–120. doi: 10.1002/pro.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 2003;33:949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Houtz RL, Alonso H. Advancing our understanding and capacity to engineer nature’s CO2-sequestering enzyme, Rubisco. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:27–35. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.164814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM. Protein-based organelles in bacteria: carboxysomes and related microcompartments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:681–691. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates TO, Thompson MC, Bobik TA. The protein shells of bacterial microcompartment organelles. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycki J, Axen SD, Kinney JN, Kerfeld CA. Cyanobacterial-based approaches to improving photosynthesis in plants. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:787–798. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.