Abstract

Interferon-alpha (IFN-α) has been identified as a neurotoxin that plays a prominent role in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neurocognitive disorders and HIV encephalitis (HIVE) pathology. IFN-α is associated with cognitive dysfunction in other inflammatory diseases where IFN-α is upregulated. Trials of monoclonal anti-IFN-α antibodies have been generally disappointing possibly due to high specificity to limited IFN-α subtypes and low affinity. We investigated a novel IFN-α inhibitor, B18R, in an HIVE/severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model. Immunostaining for B18R in systemically treated HIVE/SCID mice suggested the ability of B18R to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Real-time PCR indicated that B18R treatment resulted in a decrease in gene expression associated with IFN-α signaling in the brain. Mice treated with B18R were found to have decreased mouse mononuclear phagocytes and significant retention of neuronal arborization compared to untreated HIVE/SCID mice. Increased mononuclear phagocytes and decreased neuronal arborization are key features of HIVE. These results suggest that B18R crosses the BBB, blocks IFN-α signaling, and it prevents key features of HIVE pathology. These data suggest that the high affinity and broad IFN-α subtype specificity of B18R make it a viable alternative to monoclonal antibodies for the inhibition of IFN-α in the immune-suppressed environment.

Introduction

The advent of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) has markedly reduced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related morbidity and mortality. Despite this reduction, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) are still reported in up to 50% of HIV seropositive patients (Liner and others 2010). HAND remains among the most common causes of cognitive dysfunction in young adults and it is expected that more patients will develop the severe form known as HIV-associated dementia (HAD) due to an aging population of HIV-positive individuals (Ellis and others 2010; McArthur and others 2010).

Reaching sufficient therapeutic concentrations in the central nervous system (CNS) is a prerequisite for any effective therapy for HAND. However, the ability of different ART agents to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and reach effective concentrations in the brain varies widely from agent to agent (Cook and others 2005; Brew and others 2007). Additionally, the prevalence of HAND continues to increase in patients despite cART, reinforcing the need for specific treatments targeted to HAND (Liner and others 2010).

Delineating pathogenic mechanisms often leads to new therapeutic avenues. Recently, several agents targeting specific HAND pathogenic mechanisms were investigated in small clinical trials (Schifitto and others 1999, 2006; Sacktor and others 2000; Clifford and others 2002; Goodkin and others 2006; Nakasujja and others 2013). Despite showing some trends, the results of these trials were largely disappointing since some agents may have failed to penetrate the BBB and/or did not improve cognitive function in HAND patients. Given the results of these treatment trials and the apparent failure of cART to prevent HAND, there is a great need to develop therapies that reduce the significant, worldwide morbidity of HAND.

HIV invades the CNS shortly after exposure. With progression of disease, patients may develop HAND and its related histopathological entity, HIV encephalitis (HIVE), manifested by the presence of HIV-infected macrophages and microglia, multinucleated giant cells, activated astrocytes (astrogliosis), and neuronal damage (Tyor and others 1992; Wiley and Achim 1994). In response to HIV invasion, the immune system increases the production of cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-α, chemokines like monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and various metabolites such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Genis and others 1992; Kelder and others 1998). These immune factors produced by macrophages, microglia, and astrocytes, together with HIV proteins such as gp120 and tat, cause neuronal damage (Louboutin and Strayer 2012). Neuronal damage is associated with a decrease in the number of dendritic arborizations (Sas and others 2007), and later, the occurrence of neuronal apoptosis leading to dementia.

The neurotoxicity of interferon-alpha (IFN-α) has been well established in CNS inflammatory diseases and in cases of patients receiving IFN therapy (Rho and others 1995; Valentine and others 1998; Sas and others 2009; Fritz-French and Tyor 2012). Earlier basic and clinical research suggested a significant role of IFN-α in HIVE and pathogenesis of HAND (Rho and others 1995; Fritz-French and Tyor 2012). Neuronal defects and upregulated IFN-α levels are critical in both HAND and HIVE. Clinical studies showed that patients treated with IFN-α suffer reversible cognitive impairment and complications resembling those seen in HAND (Scheibel and others 2004). Similarly, Rho and others reported a correlation between the severity of dementia and the levels of IFN-α in HIV-seropositive patients.

Our previous studies used an HIVE/severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model to investigate the role of IFN-α (Sas and others 2007, 2009). The HIVE/SCID mouse model used shows similar histopathology and behavioral changes seen in HAND in humans (Tyor and others 1993; Avgeropoulos and others 1998; Cook and others 2005; Cook-Easterwood and others 2007). Additionally, Sas and others (2007) found a direct correlation between the amount of mouse IFN-α expression in the brain and cognitive performance in the HIVE/SCID mice. Systemically treating these HIVE/SCID mice with neutralizing antibodies (NAb) to IFN-α resulted in significant amelioration of behavioral and pathological features. However, administering NAb to HAND patients is probably not practical for multiple reasons (Sas and others 2009). Our previous studies (Sas and others 2009) like those of others (Maroun and others 2000), used polyclonal antibody preparations. Polyclonal antibodies have diverse epitope specificity and thus, inhibit multiple IFN-α subtypes, of which there are 12 functional subtypes in humans. However, administration of xenotypic polyclonal antibodies is prohibitive in humans due to serum sickness.

The use of monoclonal anti-IFN-α antibodies in clinical trials has been generally disappointing most likely because monoclonal antibodies cannot provide the wide specificity needed to fully neutralize multiple IFN-α subtypes (Petri and others 2013). B18R is a recombinant vaccinia virus gene product that binds type I IFNs more avidly than their receptor (Symons and others 1995). Based on its specificity, affinity, and immunogenicity, B18R is probably a more optimal IFN-α inhibitor than NAbs used previously (Higgs and others 2013). Complete data is not yet available, however, B18R has been shown to inhibit all IFN-α subtypes tested thus far and IFN-β, but does not inhibit type II or III IFNs (Huang and others 2007).

In this study, we used an HIVE/SCID mouse model to investigate the effects of B18R as a novel IFN-α blocker. We report that intraperitoneal (IP) injection of this novel IFN-α blocker alleviates histopathological complications in the HIVE/SCID mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Human monocyte-derived macrophages and HIV infection

Human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) were cultured and infected as described in our previous reports (Cook-Easterwood and others 2007; Sas and others 2009). Briefly, primary human monocytes and HIV-1 ADA were obtained from Dr. Howard Gendelman, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE. Cells were stimulated with macrophage colony-stimulating factor and infected on day 7 with HIV-1 ADA and cultured for an additional 2 weeks to allow for sufficient infection. MDMs were collected and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for intracranial (IC) inoculation.

Animals and inoculation

Five-week-old B6.CB17-Prkdcscid/SzJ male mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Atlanta Veterans Administration Medical Center and were in accordance with the guidelines of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23, revised 1996).

Mice were IC inoculated either with 105 HIV-infected (n=16) or uninfected (control; n=8) human MDMs resuspended in 30 μL PBS into the right frontal lobe under xylazine (5 mg/kg) and ketamine (95 mg/kg) anesthesia. IC inoculation was performed using a syringe fitted with a collar to control depth to 3 mm below the skull surface.

Production of B18R

B18R (Normferon™, gift from Meiogen Biotechnology Corp.) was produced using modified standard recombinant procedures. Briefly, the B18R gene minus the transmembrane region was subcloned into plasmid pET29a and grown in Escherichia coli strain BL-21. Following 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside induction, the cultures were pelleted and frozen. The pellets were digested with lysozyme and inclusion bodies pelleted at 15,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. After unfolding in 6 M guanidium HCl, 0.1 M Tris HCl (pH=8.0), 1.5 mM EDTA, and 6 mM dithiothreitol, the protein was refolded in refold buffer [(0.2 M guanidium HCl, 0.7 M L-arginine, 1.5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris HCl, and 10 mM NaCl (pH=8.5)] with reduced glutathione (0.615 g/L) and glutathione oxidized hydrate (0.245 g/L) added just before use.

The refolded and concentrated protein was stored at −20°C in 50% glycerin. The glycerin was diluted when the protein was concentrated and further purified by elution from a cation exchange resin (POROS HS50; Life Technologies) with 1 M NaCl. The protein gave a single 37 kDa band on PAGE gel analysis. B18R has been extensively studied in vitro (Liptakova and others 1997; Alcami 2000). Here, we study its potential for use in vivo.

For in vivo potency estimation, a test of B18R was run in nonimmunocompromised animals. Six-week-old C57/BL6 mice were induced to high levels of IFN-α by IP injection of poly I:C (300 μL at 1 mg/mL/PBS). Three hours later, they were divided into 2 groups of 3 mice each and B18R (30 μg/300 μL) or vehicle injected. Serum was collected for IFN-α ELISA analysis (PBL product No. 42120) 45 min and 4.5 h after these injections. At 45 min, IFN-α was reduced to nondetectable levels in the B18R injected group [vehicle: mean=420.8925±138.548 (SEM) pg/mL vs. B18R injected: mean ≤37 pg/mL]. At 4.5 h, IFN-α was reduced to 55% of the control level [mean=330.91±87.81 (SEM) pg/mL (vehicle) vs. mean=180.96±62.9 (SEM) pg/mL (B18R)]. No adverse effects of B18R injection were seen either in these normal mice or in the SCID mice used in the experiments reported here.

B18R treatment

Immediately after IC inoculation with either infected or uninfected MDMs, control and infected mice received either saline or B18R treatment. Each mouse received 3 IP injections of saline or B18R per day over a period of 10 days. HIV-infected mice were separated into 2 groups of 8 each. The first group (HIV-Saline; n=8) and control mice (n=8) received saline. The second HIV-infected mice group (HIV-B18R; n=8) received B18R. Each mouse of the HIV-B18R group received 50 μg of B18R per day suspended in 900 μL of PBS in divided doses (300 μL×3 times a day). Preliminary data indicated the half-life of B18R, as measured by IFN-induced gene15 (ISG15) expression in the brain at 1, 3, 6, and 12 h after B18R injections, to be 2–3 h, therefore 3 times a day dosage was chosen. Mice were monitored for physical and behavioral changes and mice showed no signs of toxicity. Physical perimeters monitored included weight, appearance of fur and ear positioning, and appearance of injection area. To monitor behavior, the mice were given fresh bedding daily to ensure that they were shredding and their level of lethargy was also assessed. Food and water intake was assessed daily and found to be normal.

Immunohistochemistry

At day 10 post-IC inoculation, all mice were sacrificed under xylazine (5 mg/kg) and ketamine (95 mg/kg) anesthesia and brains were extracted, snap-frozen in tissue-freezing medium, and stored at −70°C until cryosectioning. Sections were stained using an immunoperoxidase method as previously described (Avgeropoulos and others 1998). In brief, sections were stained for mouse microglia and macrophages (1:50 CD45; AbD Serotec), HIV (1:50 p24; Dako), human MDMs (1:20 EBM11; Dako), astrogliosis [1:750 glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP); Chemicon], and neuronal dendrites (1:200 microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP2); Chemicon). Slides were then reviewed under a light microscope (Olympus Microscope).

To stain for B18R, Ab was produced in rabbits by injection of resuspended inclusion body pellets (Cocalico Biologicals). Serum was run through Pierce Protein A columns according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pierce Biotechnology). Sections were stained with B18R (1:500). To demonstrate the capability of our immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining to detect B18R, mice were IC inoculated with B18R. Brains were stained using anti-B18R antibody, which acted as positive controls. To determine specificity of the anti-B18R antibody, B18R and brain lysate samples were assessed on a PAGE gel. Protein was harvested from SCID mouse brain using RIPA buffer with 10 μL/mL protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). Total protein concentration was determined by a Pierce® BCA Protein Assay Kit. B18R alone, B18R with brain lysate, and brain lysate samples were then loaded on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel. Protein was run at 200 V for 40 min and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using the Trans-blot Turbo transfer system (Biorad). The anti-B18R antibody was used as primary antibody at 1:2,500. The membrane was then washed and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked secondary antibody at 1:10,000 (Cell Signaling). The membrane was then exposed to X-ray film using Supersignal® West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific). Detection of a single band representing B18R at 37.9 kDa was observed in the brain lysate samples containing B18R. No bands were evident in brain lysate alone when probed with anti-B18R antibody (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jir).

Densitometry scoring

The optical density was obtained as follows: ×4 (GFAP), 20× (CD45 and MAP2) and 40× (B18R) images were captured using a QImaging Retiga EXi digital camera attached to an Olympus BX51 microscope. Images were then analyzed by ImageJ 1.45S software (NIH). Microscope and image capture parameters were kept constant. Each slide was subjected to the ImageJ software by selecting the representative GFAP-positive area and adjustments were made to include all GFAP and CD45-positive staining. Artifactual signal such as empty ventricles or folded tissue was not measured. For B18R, positive and background staining was measured in the injection site area in all B18R and saline-injected mice. A mean optical density value was generated from each slide, which was then averaged for each mouse prior to statistical analysis.

For MAP2 staining, mean optical density in the uninjected hemisphere (left) was assigned as a control for the injected hemisphere (right). The intensity of signal was measured in both left and right hemispheres and the percent reduction in MAP2 staining was considered a surrogate for the percent reduction in dendritic arborization. A mean value was calculated from each section (left and right) and then averaged by mouse from 2 sections before the statistical analysis.

Human MDMs and p24-positive cells

EBM11 (human MDMs) and p24 positively stained cells in 3 sequential sections in the injection site area were counted from each slide and then averaged for each mouse as previously described (Avgeropoulos and others 1998). We counted a p24 or EBM11 positively stained cell as a single cell regardless of whether it was a single human macrophage or a single multinucleated cell. Dark brown reaction indicated positive staining for EBM11 or p24. Researchers were blinded prior to counting cells on slides.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

We collected the intervening sections (45 sections between each set; refer to Immunohistochemistry section), which were not used for IHC as previously described. RNA was extracted from these sections using the RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer (Qiagen) protocol. For each brain we used approximately 1 μg of RNA for cDNA synthesis. The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit according to the manufacturer (Biorad) protocol.

Real-time PCR

Levels of mouse ISG15, IFN-alpha 4 gene (IFNA4), and IFN-alpha response gene 15 (Ifrg15) were analyzed using real-time PCR with a Biorad C1000 Thermocycler. Levels were normalized to the levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatedehydrogenase (GAPDH), a housekeeping gene, which was used as the endogenous control for all experiments. ISG15, IFNA4, Ifrng15, and GAPDH primers were designed using Assays-by-Design (Applied Biosystems). cDNA samples were added to TaqMan Assay mix (Applied Biosystems) and the primer/probe mix. Relative quantification of the ISGs in unknown samples was done in comparison to the levels of GAPDH in each sample. The relative changes in gene expression were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Statistics

Analyses of densitometry values and relative gene expression levels were performed using 1-way ANOVA and an unpaired t-test in GraphPad Prism 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software). Significance was set at P<0.05 for all analyses.

Results

HIV-infected MDMs in mouse brain

We counted the number of EBM11 and p24 positively stained cells corresponding to the number of human MDMs and HIV-infected human MDMs respectively in the brains of mice IC inoculated with uninfected (control) human MDMs, mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected MDMs treated with saline (HIV-Saline) and mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected MDMs treated with B18R (HIV-B18R). There was no statistically significant difference between the total number of human monocytes and macrophages across the 3 groups (data not shown) based on positively stained cells for EBM11. These findings indicate that approximately the same number of HIV-infected and uninfected human MDMs were inoculated into the control and HIV-infected mouse brains. Staining showed human MDMs scattered around the injection site. These findings were consistent with our previously reported data (Cook-Easterwood and others 2007; Sas and others 2009).

Similarly, there was no significant difference in the numbers of p24 positively stained cells in the brains of HIV-Saline and HIV-B18R-treated mice, indicating the presence of the same number of HIV-infected human MDMs in both groups. As measured by p24-positive human MDM, CNS HIV did not increase (see Supplementary Fig. S2). This is consistent with previous studies using polyclonal anti-IFN-α antiserum (Sas and others 2009).

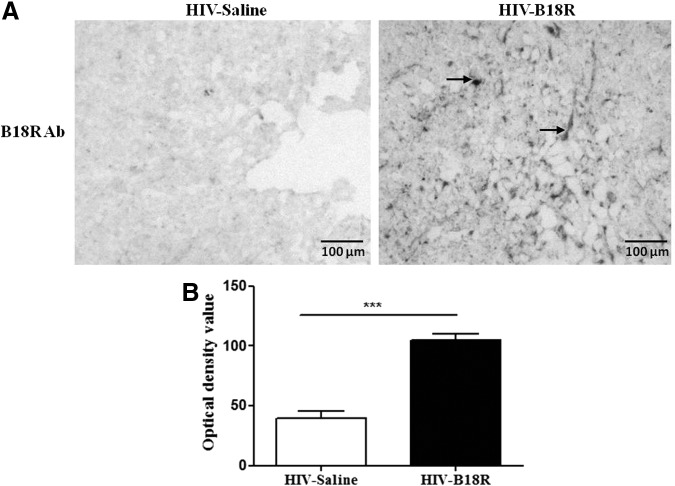

B18R crossed the BBB

We examined mouse brain using an antibody against B18R, which showed the presence of B18R in the brain parenchyma and suggested localization on glia and neurons (data not shown). B18R densitometry indicated that mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs that received IP injections of B18R had significantly higher densitometric values compared with background staining detected in mice that received saline treatment (HIV-B18R vs. control; P<0.001) as shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Immunohistochemistry staining for B18R in mouse human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected brain tissue in B18R-treated and untreated groups (A). Arrows indicate positive B18R staining on cells within the brain. Densitometry values (B) of B18R in brain sections of mice inoculated with HIV-infected human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) and treated with saline (HIV-Saline; n=8) or B18R (HIV-B18R; n=8) (***P<0.001).

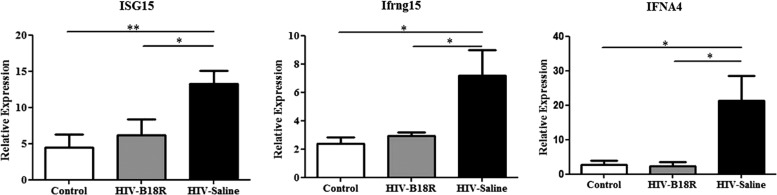

B18R inhibited IFN-α signaling in the brain

To assess the ability of the IP injected B18R to cross the mouse BBB and block IFN-α signaling pathways in the brain, we used real-time PCR to measure mRNA levels for ISG15, IFNA4, and Ifrng15, genes that are activated after IFN-α receptor engagement. The mRNA levels of the ISGs in mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs treated with saline (HIV-Saline) were significantly higher (P<0.05) than those observed in control and HIV-B18R as shown in Fig. 2. Interestingly, the B18R treatment resulted in ISGs mRNA levels similar to those observed in the control mice group, suggesting that B18R completely inhibited IFN-α signaling in brain.

FIG. 2.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) [ISG15, IFN-alpha response gene 15 (Ifrg15), and IFN-alpha 4 gene (IFNA4)] mRNA in control (mice inoculated with uninfected human MDMs and treated with saline; n=8), HIV-Saline (mice inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs and treated with saline; n=8), and HIV-B18R (mice inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs and treated with B18R; n=8) (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

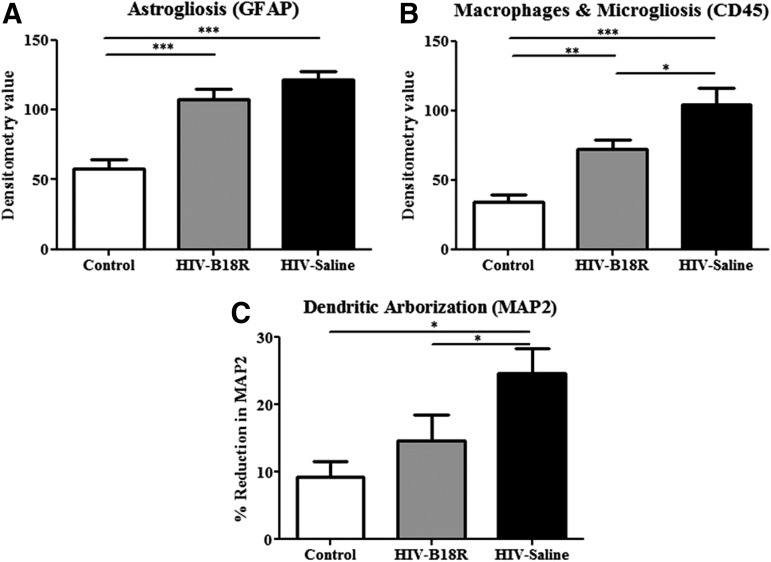

Astrogliosis

GFAP densitometry showed that mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs had significantly higher astrogliosis than mice IC inoculated with uninfected human MDMs (HIV-Saline and HIV-B18R vs. control; P<0.001) as shown in Fig. 3A (see also Supplementary Fig. S3). This finding is consistent with our previously reported data (Avgeropoulos and others 1998; Sas and others 2009). Densitometry values for astrogliosis were lower in B18R-treated mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs, but did not reach statistical significance.

FIG. 3.

Densitometry values of astrogliosis, microgliosis, and dendritic arborization in all mice. Astrocytes [mouse glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)] expression was slightly decreased in HIV-B18R mice compared with HIV (A) (***P<0.001). Mice treated with B18R had significantly less staining for mouse macrophages and microglia (mouse CD45) compared with HIV mice (B) (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). B18R-treated mice were significantly protected against reduction in dendritic arborization [mouse microtubule associated protein-2 (MAP2)] compared to HIV mice (C) (*P<0.05).

Mouse macrophages and microglia

CD45 densitometry showed that mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs had significantly higher presence of mouse macrophages and microglia, than in control mice (HIV-Saline vs. control; P<0.001) as shown in Fig. 3B. Interestingly, B18R treatment significantly reduced (HIV-Saline vs. HIV-B18R; P<0.05) CD45 staining in mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs. However, B18R treatment did not bring the level of mouse macrophages and microglia staining down to control levels.

Neuronal dendritic arborization

In accordance with previously reported data (Cook-Easterwood and others 2007; Sas and others 2007), our results indicate that mice IC inoculated with HIV-infected human MDMs had more dendritic loss, as measured by MAP2 staining (P<0.05) compared with control mice (Fig. 3C). Treatment with B18R showed a significant improvement of MAP2 staining compared with saline-injected mice.

Discussion

In this investigation B18R treatment alleviated histopathological complications seen in an HIVE/SCID mouse model. Our data indicate that the IP injected B18R was capable of crossing the BBB, as evident by the IHC staining and densitometry results. B18R treatment reduced the severity of histopathology and inhibited IFN-α mediated signaling in mouse brains. Importantly, the treatment with B18R had no effect on HIV infection since approximately the same numbers of p24 positively stained MDMs were found in saline and B18R-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Elevated IFN-α levels in the CNS are associated with cognitive abnormalities (Fritz-French and Tyor 2012). The expression of type I IFN genes was shown to be elevated in the frontal cortex of HAD patients (Masliah and others 2004). Previous reports showed that the levels of IFN-α were significantly higher in the CSF of HIV-infected patients with dementia compared with HIV patients without dementia or HIV-negative individuals (Rho and others 1995; Krivine and others 1999).

Interestingly, IFN-α levels in the CNS were directly correlated with the severity of dementia. Our mouse model reflects these clinical studies showing elevated levels of IFN-α, increased IFN-mediated signaling (Fig. 2), and abnormal cognitive behavior.

Previous studies in our lab found that treating HIVE/SCID mice with IFN-α NAbs alleviated cognitive dysfunction and improved HIVE in mice. B18R protein is a more ideal treatment than NAbs because it is a direct IFN-α-binding protein with higher affinity for IFN-α than the type I IFN receptor and is a multi-subtype IFN-α inhibitor with a very high binding affinity (Symons and others 1995), suggesting the possibility of very low-dose therapy with B18R. The binding constant of B18R surpasses antibodies by more than an order of magnitude (Boder and others 2000). Cytokine-binding proteins with low affinity run the risk of agonist rather than antagonist activity by stabilizing normally short lived cytokines (Klein and Brailly 1995). Antibody affinity can be increased using phage display technology but, with humanized antibodies, these modifications generally increase the risk of human constant region auto-antibody induction (Boder and others 2000).

In clinical practice, all injected proteins are immunogenic whether human or non-human (Thorpe 2013). This suggests that NAbs maybe endogenously produced to counteract injected monoclonal antibodies resulting in treatment failure (Leroy and others 1998; Hemmer and others 2005). For example, the anti-IFN-α fully human IgG used in clinical trials induced an immune response in up to 20% of injected patients (Higgs and others 2013). In addition to being anti-idiotypic, these antibodies can often bind to human IgG constant regions with the associated risk of inducing immune complex-mediated disease (CHMP 2010). Viral immunomodulatory proteins are often modified human proteins but, in some cases, they have no amino acid sequence homology to any human protein (Lucas and McFadden 2004). B18R has minimal, if any, amino acid sequence homology to any human protein and thus provides the advantage that its expected immunogenicity in immune-competent individuals is not likely to induce autoimmunity.

In viral infections significant type I IFN, including IFN-α, is produced, which plays a vital role in suppressing viral replication. Consequently, reducing type I IFNs with B18R could result in a damaging effect on the immune system's ability to mount an appropriate antiviral response leading to increased viral loads. However, previous studies showed that IFN-β (Sas and others 2009) and likely IFN-γ and type III IFNs are still present in HIVE/SCID mice, where IFN-α has been blocked. In addition, B18R treatment is expected to improve the ability of patients to fight infection. This somewhat counterintuitive result was demonstrated in clinical trials in late-stage HIV+ patients where improved blood lymphocyte counts and decreased viral load was observed in those HIV-infected patients who were successfully immunized against their own IFN (Gringeri and others 1999). Despite these cautions regarding potential B18R treatment in humans, the present study strongly suggests that HIV loads were not affected by B18R treatment in the HIVE/SCID mice.

The vast majority of HIV-infected cells in the CNS are macrophages and microglia (ie, increased presence of mononuclear phagocytes) (Glass and Wesselingh 2001). The presence of increased numbers of macrophages and microglia, other than demonstrating HIV infection of brain, is arguably the hallmark of HIVE (Glass and Wesselingh 2001). These cells are probably the main source of HIV, HIV proteins like Tat, cellular metabolites that are potential neurotoxins, and IFN-α (Tyor 2009). Therefore, reducing the number of reactive macrophages and microglia in HIVE may, in and of itself, alleviate neuronal abnormalities and thus cognitive dysfunction. Interestingly, our results show that the IP injected B18R in HIVE/SCID mice significantly reduced the presence of mouse macrophages and microglia (Fig. 3B). Results of this study are consistent with our previously reported data in which IP injections of IFN-α NAbs significantly reduced the presence of mouse macrophages and microglia in HIVE/SCID mice.

In our study, B18R did not significantly reduce astrogliosis (Fig. 3A). These results were consistent with those reported by Sas and others in which the IP injected IFN-α NAbs did not reduce astrogliosis. Therefore, astrogliosis might not be a critical feature of HIVE. Our previous studies using cART in this HIVE/SCID mouse model have also suggested that astrogliosis is not as important as increased numbers of macrophages and microglia in the pathogenesis of HAND (Cook and others 2005; Cook-Easterwood and others 2007). While cART in HIVE/SCID mice reduced astrogliosis, it had no effect on MAP2 reductions (ie, neuronal integrity) or behavioral dysfunction (Cook-Easterwood and others 2007). Taken together, these studies suggest that reducing the number of macrophages and microglia, but not astrocytes, in HIVE is associated with preservation of neuronal integrity.

Although HIV does not infect neurons, neurotoxicity in HAND is evident by neuronal and neurocognitive abnormalities (McArthur and others 2010). As stated above, infected macrophages and microglia in HIVE interact with other cells in the CNS to produce substances like TNF-α and IFN-α, which cause neurotoxicity (Tyor 2009). In the present study, B18R preserved dendritic arborization as shown by MAP2 staining compared to saline-injected mice (Fig. 3C). The deleterious action of IFN-α on neuronal function and anatomy was demonstrated in our previous in vivo and in vitro investigations. Although the exact mechanism has to be elucidated, our in vitro experiments suggest that part of this mechanism involves N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. This is interesting because other putative HIVE neurotoxins (eg, gp120) have also been linked to NMDA toxicity (Potter and others 2013; Yang and others 2013). Therefore, this may represent a final common pathway for several neurotoxins implicated in HAND pathogenesis. Our results suggest that B18R would be an effective therapeutic agent to prevent or reduce IFN-α neurotoxicity in HAND. Future studies will look at behavior in HIVE/SCID mice to see whether B18R treatment not only prevents cognitive dysfunction, but reverses it, as seen in patients that discontinue IFN-α therapy.

It is important to note that the pathogenesis of HAND likely involves multiple putative neurotoxins that are not limited to IFN-α. The severe form of HAND (ie, HAD) may result from synergistic neurotoxicity of viral proteins like Tat and gp120 in addition to IFN-α and other neurotoxins, such as free radicals (Tyor 2009). Nevertheless, it seems likely that IFN-α is a major source of neurotoxicity in HAND, especially early in the course of the disease. Here, we have shown that B18R treatment resulted in improvement in HIVE/SCID mice, suggesting that B18R is likely to be an effective therapy in humans. Future studies will investigate the effects of B18R on improving behavioral memory tasks in cognitively impaired HIVE/SCID mice as was previously investigated with IFN-α NAb and in combination with cART. If these studies are successful, B18R may be moved forward into Phase I trials in humans with HAND.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Hee Young Hwang for her preliminary work with B18R prior to this publication. The work in this manuscript was largely supported by VA Merit Award 0007 and a grant from Meiogen Biotechnology Corporation, Inc. C.F.F. was supported by an R25 Pilot Grant from the Johns Hopkins University NIMH Center. R.S. was supported by funds from the Department of Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine.

Authors' Contributions

C.F.F. and R.S. equally contributed to this work and share first authorship. J.E.W. and L.E.M. made, tested, and provided the B18R as well as guidance in terms of dosing of B18R. R.S. and C.F.F. helped to design and perform the experiments and wrote the article. W.R.T. designed the experiments and wrote the article, which was additionally edited and commented on by the other authors.

Author Disclosure Statement

L.E.M and J.E.W. hold stock in Meiogen Biotechnology Corporation, Inc. All additional co-authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- Alcami A.S.J.A.S.G.L. 2000. The vaccinia virus soluble alpha/beta interferon (IFN) receptor binds to the cell surface and protects cells from the antiviral effects of IFN. J Virol 74(23):11230–11239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgeropoulos N, Kelley B, Middaugh L, Arrigo S, Persidsky Y, Gendelman HE, Tyor WR. 1998. SCID mice with HIV encephalitis develop behavioral abnormalities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 18(1):13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boder ET, Midelfort KS, Wittrup KD. 2000. Directed evolution of antibody fragments with monovalent femtomolar antigen-binding affinity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97(20):10701–10705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew BJ, Halman M, Catalan J, Sacktor N, Price RW, Brown S, Atkinson H, Clifford DB, Simpson D, Torres G, Hall C, Power C, Marder K, McArthur JC, Symonds W, Romero C. 2007. Factors in AIDS dementia complex trial design: Results and lessons from the abacavir trial. PLoS Clin Trials 2(3):e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford DB, McArthur JC, Schifitto G, Kieburtz K, McDermott MP, Letendre S, Cohen BA, Marder K, Ellis RJ, Marra CM. 2002. A randomized clinical trial of CPI-1189 for HIV-associated cognitive-motor impairment. Neurology 59(10):1568–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Dasgupta S, Middaugh LD, Terry EC, Gorry PR, Wesselingh SL, Tyor WR. 2005. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Ann Neurol 57(6):795–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Easterwood J, Middaugh LD, Griffin WC, 3rd, Khan I, Tyor WR. 2007. Highly active antiretroviral therapy of cognitive dysfunction and neuronal abnormalities in SCID mice with HIV encephalitis. Exp Neurol 205(2):506–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Rosario D, Clifford DB, McArthur JC, Simpson D, Alexander T, Gelman BB, Vaida F, Collier A, Marra CM, Ances B, Atkinson JH, Dworkin RH, Morgello S, Grant I, Group CS. 2010. Continued high prevalence and adverse clinical impact of human immunodeficiency virus-associated sensory neuropathy in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: the CHARTER Study. Arch Neurol 67(5):552–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz-French C, Tyor W. 2012. Interferon-alpha (IFN alpha) neurotoxicity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 23(1–2):7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genis P, Jett M, Bernton EW, Boyle T, Gelbard HA, Dzenko K, Keane RW, Resnick L, Mizrachi Y, Volsky DJ, Epstein LG, Gendelman HE. 1992. Cytokines and arachidonic metabolites produced during human-immunodeficiency-virus (HIV)-infected macrophage-astroglia interactions—implications for the neuropathogenesis of HIV disease. J Exp Med 176(6):1703–1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JD, Wesselingh SL. 2001. Microglia in HIV-associated neurological diseases. Microsc Res Tech 54(2):95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin K, Vitiello B, Lyman WD, Asthana D, Atkinson JH, Heseltine PN, Molina R, Zheng W, Khamis I, Wilkie FL, Shapshak P. 2006. Cerebrospinal and peripheral human immunodeficiency virus type 1 load in a multisite, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of D-Ala1-peptide T-amide for HIV-1-associated cognitive-motor impairment. J Neurovirol 12(3):178–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringeri A, Musicco M, Hermans P, Bentwich Z, Cusini M, Bergamasco A, Santagostino E, Burny A, Bizzini B, Zagury D. 1999. Active anti-interferon-alpha immunization: a European-Israeli, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 242 HIV-1—infected patients (the EURIS study). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 20(4):358–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmer B, Stuve O, Kieseier B, Schellekens H, Hartung HP. 2005. Immune response to immunotherapy: the role of neutralising antibodies to interferon beta in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 4(7):403–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs BW, Zhu W, Morehouse C, White WI, Brohawn P, Guo X, Rebelatto M, Le C, Amato A, Fiorentino D, Greenberg SA, Drappa J, Richman L, Greth W, Jallal B, Yao Y. 2013. A phase 1b clinical trial evaluating sifalimumab, an anti-IFN-alpha monoclonal antibody, shows target neutralisation of a type I IFN signature in blood of dermatomyositis and polymyositis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 73(1):256–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Smirnov SV, Lewis-Antes A, Balan M, Li W, Tang S, Silke GV, Putz MM, Smith GL, Kotenko SV. 2007. Inhibition of type I and type III interferons by a secreted glycoprotein from Yaba-like disease virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(23):9822–9827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder W, McArthur JC, Nance-Sproson T, McClernon D, Griffin DE. 1998. beta-chemokines MCP-1 and RANTES are selectively increased in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol 44(5):831–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B, Brailly H. 1995. Cytokine-binding proteins: stimulating antagonists. Immunol Today 16(5):216–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivine A, Force G, Servan J, Cabee A, Rozenberg F, Dighiero L, Marguet F, Lebon P. 1999. Measuring HIV-1 RNA and interferon-alpha in the cerebrospinal fluid of AIDS patients: insights into the pathogenesis of AIDS Dementia Complex. J Neurovirol 5(5):500–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy V, Baud M, de Traversay C, Maynard-Muet M, Lebon P, Zarski JP. 1998. Role of anti-interferon antibodies in breakthrough occurrence during alpha 2a and 2b therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 28(3):375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liner KJ, 2nd, Ro MJ, Robertson KR. 2010. HIV, antiretroviral therapies, and the brain. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 7(2):85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptakova H, Kontsekova E, Alcami A, Smith GL, Kontsek P. 1997. Analysis of an interaction between the soluble vaccinia virus-coded type I interferon (IFN)-receptor and human IFN-alpha1 and IFN-alpha2. Virology 232(1):86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods 25(4):402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louboutin JP, Strayer DS. 2012. Blood-brain barrier abnormalities caused by HIV-1 gp120: mechanistic and therapeutic implications. ScientificWorldJournal 2012:482575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A, McFadden G. 2004. Secreted immunomodulatory viral proteins as novel biotherapeutics. J Immunol 173(8):4765–4774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroun LE, Heffernan TN, Hallam DM. 2000. Partial IFN-alpha/beta and IFN-gamma receptor knockout trisomy 16 mouse fetuses show improved growth and cultured neuron viability. J Interferon Cytokine Res 20(2):197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Roberts ES, Langford D, Everall I, Crews L, Adame A, Rockenstein E, Fox HS. 2004. Patterns of gene dysregulation in the frontal cortex of patients with HIV encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol 157(1–2):163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, Steiner J, Sacktor N, Nath A. 2010. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorders: mind the gap. Ann Neurol 67(6):699–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasujja N, Miyahara S, Evans S, Lee A, Musisi S, Katabira E, Robertson K, Ronald A, Clifford DB, Sacktor N. 2013. Randomized trial of minocycline in the treatment of HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Neurology 80(2):196–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri M, Wallace DJ, Spindler A, Chindalore V, Kalunian K, Mysler E, Neuwelt CM, Robbie G, White WI, Higgs BW, Yao Y, Wang L, Ethgen D, Greth W. 2013. Sifalimumab, a human anti-interferon-alpha monoclonal antibody, in systemic lupus erythematosus: a phase I randomized, controlled, dose-escalation study. Arthritis Rheum 65(4):1011–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter MC, Figuera-Losada M, Rojas C, Slusher BS. 2013. Targeting the glutamatergic system for the treatment of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 8(3):594–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho MB, Wesselingh S, Glass JD, McArthur JC, Choi S, Griffin J, Tyor WR. 1995. A potential role for interferon-alpha in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated dementia. Brain Behav Immun 9(4):366–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor NC, Skolasky RL, Lyles RH, Esposito D, Selnes OA, McArthur JC. 2000. Improvement in HIV-associated motor slowing after antiretroviral therapy including protease inhibitors. J Neurovirol 6(1):84–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sas AR, Bimonte-Nelson H, Smothers CT, Woodward J, Tyor WR. 2009. Interferon-alpha causes neuronal dysfunction in encephalitis. J Neurosci 29(12):3948–3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sas AR, Bimonte-Nelson HA, Tyor WR. 2007. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV encephalitic SCID mice correlates with levels of Interferon-alpha in the brain. AIDS 21(16):2151–2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel RS, Valentine AD, O'Brien S, Meyers CA. 2004. Cognitive dysfunction and depression during treatment with interferon-alpha and chemotherapy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 16(2):185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifitto G, Peterson DR, Zhong J, Ni H, Cruttenden K, Gaugh M, Gendelman HE, Boska M, Gelbard H. 2006. Valproic acid adjunctive therapy for HIV-associated cognitive impairment: a first report. Neurology 66(6):919–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifitto G, Sacktor N, Marder K, McDermott MP, McArthur JC, Kieburtz K, Small S, Epstein LG. 1999. Randomized trial of the platelet-activating factor antagonist lexipafant in HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Neurological AIDS Research Consortium. Neurology 53(2):391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons JA, Alcami A, Smith GL. 1995. Vaccinia virus encodes a soluble type-I interferon receptor of novel structure and broad species-specificity. Cell 81(4):551–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe R, FRCPath , Wadhwa M. 2013. New CHMP Guideline on immunogenicity of monoclonal antibodies. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal 2(1):45–46 [Google Scholar]

- Tyor WR. 2009. Pathogenesis and treatment of HIV-associated dementia: recent studies in a SCID mouse model. In: Banik N, ed. Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin, pp. 472–489 [Google Scholar]

- Tyor WR, Glass JD, Griffin JW, Becker PS, McArthur JC, Bezman L, Griffin DE. 1992. Cytokine expression in the brain during the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol 31(4):349–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyor WR, Power C, Gendelman HE, Markham RB. 1993. A model of human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis in SCID mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90(18):8658–8662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine AD, Meyers CA, Kling MA, Richelson E, Hauser P. 1998. Mood and cognitive side effects of interferon-alpha therapy. Semin Oncol 25(1 Suppl 1):39–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley CA, Achim C. 1994. Human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis is the pathological correlate of dementia in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol 36(4):673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Hu D, Xia J, Liu J, Zhang G, Gendelman HE, Boukli NM, Xiong H. 2013. Enhancement of NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents by gp120-treated macrophages: implications for HIV-1-associated neuropathology. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 8(4):921–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.