Abstract

The aim of this study was to analyze the rates of condom use among military and police populations in Peru, focusing on differences in use by type of partner. A Knowledge Attitudes and Practices survey was conducted among 6,808 military and police personnel in 18 Peruvian cities between August–September 2006 and September–October 2007. A total of 90.2% of the survey respondents were male; mean age was 37.8 years and 77.9% were married/cohabiting. In all, 99.5% reported having had sex; 89% of the participants had their last sexual contact with their stable partner, 9.7% with a nonstable partner, and 0.8% with a sex worker. Overall, 20.4% used a condom during their most recent sexual contact. Reasons for nonuse of condoms included the following: perception that a condom was not necessary (31.3%) and using another birth control method (26.7%). Prevention efforts against sexually transmitted diseases should focus on strengthening condom use, especially among individuals with nonstable partners.

Keywords: condom use, HIV/AIDS, military, risk factors, sexually transmitted diseases/infections

Introduction

Military and police populations have been described as being a high-risk population for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV infection as they are primarily male, young, sexually active, and lack access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information and services (Timmermans, 1996). Furthermore, military and police personnel are considered to be mobile populations in that they spend more than 1 month annually away from home (Sopheab, Fylkesnes, Vun, & O’Farrell, 2006), apart from their families, spouses, or partners, which may increase the likelihood of engaging in casual sex with a nonstable partner or a sex worker (Samnang et al., 2004; Sopheab et al., 2006). Additionally, past research in the general population has shown that condom use varies with different types of sex partners (i.e., stable, nonstable, or sex worker; Couture et al., 2008; Sopheab et al., 2006). This information, however, has not been examined for military and police populations, thus preventing the design of well-targeted interventions.

Research related to the involvement of men in sexual and reproductive health programs has primarily focused on the knowledge and use of male contraceptive methods and the promotion of STI prevention through responsible male sexual behavior. However, little attention has been paid to men’s own sexual health concerns (Baser, Tasci, & Albayrak, 2007; United Nations Development Programme/United Nations Population Fund/World Health Organization, 2002), particularly among military and police forces, within whom condom use rates and reasons for not using condoms in Latin America have not been studied.

The Peruvian Armed Forces (Army, Navy, and Air Force) consists of approximately 115,000 active-duty personnel. The first case of AIDS in the Peruvian Armed Forces was reported in 1986; since then, 844 cases of HIV and AIDS have occurred in the military, among them 449 active-duty military members. The majority (73%) of HIV-infected persons are from Lima. However, the current rate of infection among military personnel in Peru is unknown (COPRECOS). The Commission for Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS in Peruvian Armed Forces (COPRECOS–Peru; http://coprecosperu.org), a governmental institution founded in 1990, has conducted several activities to improve the sexual health of these populations. As part of these activities, evaluations of sexual health knowledge and sexual risk behavior have been conducted by COPRECOS. The current study is the result of an ongoing collaboration between COPRECOS and the U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit Six (NAMRU-6), which started in 2005 and has resulted in several epidemiological and intervention studies. In this study, the investigators aimed to analyze the rates of condom use among military and police populations in Peru, focusing on differences in use by type of partner and the reasons for nonuse.

Method

A cross-sectional study of sexual behavior was conducted between 2006 and 2007 in military personnel and police.

Study Population

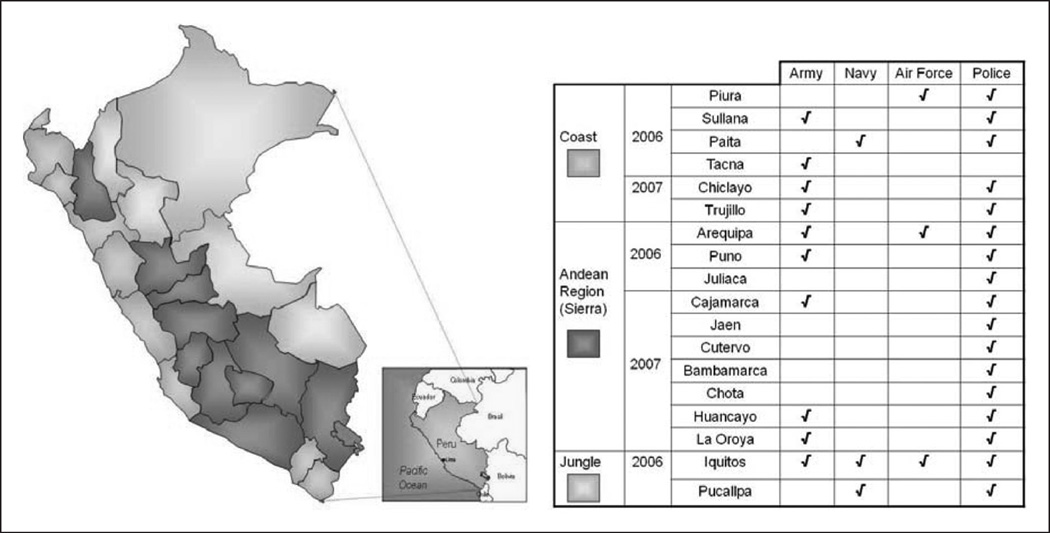

Personnel from all ranks of the three Peruvian Armed Forces (Army, Navy, and Air Force) and Peruvian National Police stationed in 18 cities distributed along the three major geographic regions of Peru (coast, highlands, and jungle) were invited to participate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of distribution of cities enrolled by region

Enrollment and Data Collection

All potential participants were gathered in a convenient facility (depending on the site, this could be an auditorium or a comfortable classroom). After an informational presentation about the study carried out by COPRECOS health professionals, attending personnel were invited to participate. At each site, an oral consent process was conducted to maintain the participants’ confidentiality. The information related to the informed consent process was provided by trained NAMRU-6 personnel prior to any further activity. Once the informed consent process had been carried out, NAMRU-6 personnel distributed an anonymous self-administered questionnaire. It was clearly stated that everyone would receive a questionnaire, but they could return it blank if they did not want to participate. All participants were provided with standard black pens, and all questionnaires were collected in standard black plastic bags, so that no participant’s survey could be identified. To avoid the possibility of coercion, it was made clear that participation was voluntary and anonymous, and all supervising officers left the room during the administration of the survey.

These activities took place in selected military and police bases in three major regions of Peru (Figure 1). This distribution assured not only geographic but also ethnic and cultural diversity. The activities related to this study took place between August–September, 2006 and September– October, 2007.

After coordinating with military and police authorities and unit commanders, at a central level (Ministries of Defense and Interior) and then at each site, COPRECOS personnel delivered informative HIV/STI education and prevention talks, then explained the study and invited all personnel present to participate in the survey. This survey contained 88 questions, distributed in 7 modules: “Demographic data”; “Impact recognition of HIV/AIDS and perception of infection risk,” which included questions related with number of sexual partners (in the previous 5 years, 12 and 3 months), HIV serostatus, and characteristics of the last sexual partner and last sexual contact; “Communication for behavioral change related to HIV/AIDS,” which asked about sources of information about HIV/AIDS and perception about these sources; “Use and access to condoms,” which was the main source of information for this article; “Use and access to HIV/AIDS tests”; “Knowledge and access to HIV/AIDS and STIs treatments”; and “Alcohol use,” which asked about frequency and volume of alcohol consumption in the previous 3 months, and sexual contacts after it.

Given that the information obtained from the survey would be used in the design of prevention policies and programs, honesty was explicitly solicited from respondents when completing the survey. Additionally, NAMRU-6 and COPRECOS study personnel clearly explained that this survey was not meant to be a test or an examination and that there were no correct or incorrect answers to these questions. Finally, participants were told that they could skip any question that made them feel uncomfortable and continue with the next one.

Sampling

The study sites were selected considering the number of reported HIV cases in each region. The sample size per site was a convenience sample. All the military/police units in each of the selected departments were visited. In each unit, all the military or police personnel present during the visit were invited to participate.

Analysis

The data were entered into a database using FoxPro software at NAMRU-6; double data entry with independent data entry personnel was used to maintain consistency and accuracy of the data.

Descriptive univariate analyses were performed to calculate means (with standard deviations [SDs]) and frequencies; medians and quartiles were used when the variables did not have a normal distribution. For condom use analysis, sexual partners were grouped in three categories: stable partners (wives/husbands/cohabitants, girlfriends/boyfriends, and engaged partners), nonstable partners (friends and casual partners), and commercial sex workers. To provide a clear image of age distribution, the study population was arbitrarily divided into six age-groups: 18 to 20, 21 to 30, 31 to 40, 41 to 50, 51 to 59, and 60 years and older. Regarding marital status, participants were categorized as single, married, cohabiting, divorced, separated, or widow(er); participants were divided into members of the Armed Forces (Army, Navy, Air Force) or Police Force. Other dichotomous variables used in the analyses were alcohol consumption prior to the last sexual contact (yes/no), gender (male/female), institution (police/armed force), and the outcome variable, condom use during the last sexual contact (yes/no). The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to examine differences in proportions.

Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression to assess the relationship between the type of sexual partner and condom use in the study population adjusting for the potential confounding effect of other variables.

All reported p values were two sided; p values ≤.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using STATA 10.0 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) and EpiInfo 6.0.

Ethics

Following federal regulations (45 CRF 46.102 f), this protocol was reviewed as nonhuman subject research by the U.S. Naval Medical Research Center in Silver Spring, MD and by a local institutional review board (IRB; NAMRU-6 in Lima, Peru; local IRB register No. RCEI-78).

Results

The survey yielded 6,808 participants. Mean age was 37.8 years (SD = 8.6, range = 18–76), 90.2% were male and 77.9% were married/cohabiting. Nearly all respondents (99.5%) reported having had sexual intercourse in the past, and the mean age of sexual debut was 16.8 years (SD = 2.9, range = 6–70). Nearly all participants reported ever having had vaginal sex (99.1%), whereas 44.6% and 50.5% reported ever having had anal and oral sex, respectively (see Table 1 for further socioepidemiological data). For their most recent sexual contact, 89.5% of participants reported sex with a stable partner, 9.7% sex with a nonstable partner, and 0.8% sex with a sex worker. Among married participants, 12.5% reported sex with someone other than their spouse at last sexual contact.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Sexual Partners of Surveyed Peruvian Military and Police Personnel

| Military Personnel | Police Agents | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 36.7 (8.5)a | 38.6 (8.6)a | 37.8 (8.6)a |

| Male, percentage (n/N) | 95.3 (2,670/2,802) | 86.6 (3,412/3,940) | 90.2 (6,086/6,746) |

| Marital status, % (n/N) | |||

| Single | 20.5 (571/2,787) | 16.9 (661/3,916) | 18.4 (1,232/6,706) |

| Married/cohabiting | 76.2 (2124/2,787) | 79.1 (3,099/3,916) | 77.9 (5,226/6,706) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 3.3 (92/2,787) | 4.0 (156/3,916) | 3.7 (248/6,706) |

| Last sexual partner, % (n/N) | |||

| Stable | 89.3 (2,359/2,641) | 89.5 (3,337/3,727) | 89.5 (5,700/6,372) |

| Nonstable | 9.4 (248/2,641) | 9.9 (370/3,727) | 9.7 (618/6,372) |

| Sexual worker | 1.3 (34/2,641) | 0.5 (20/3,727) | 0.8 (54/6,372) |

No data (military personnel = 51, police agents = 61, total = 113).

Only 20.4% of the participants used a condom at last sexual contact, regardless of the type of sex partner (24.8% and 17.4% for military personnel and police agents, respectively). Among those not using a condom, reasons included a belief that condoms were unnecessary (31.3%), using another birth control method (26.7%), and not liking condoms (17.1%).

When condom use during last sexual contact was analyzed by the type of sex partner, only 18.4% of respondents reported using condoms with their stable partner. In comparison, respondents used a condom nearly twice as often with a nonstable partner (34.0%) and more than 4 times more often with a commercial sex worker (75.5%).

Among participants who did not use condoms at last sex with a stable partner, the reasons were the following: did not consider condoms to be necessary (31.8%), using another birth control method (27.7%), and does not like condoms (15.5%). Reasons for not using condoms with nonstable partners included not liking condoms (31.1%), not having planned to have sex (25.4%), a belief that condoms were unnecessary (23.3%), and using another birth control method (11.8%). Among participants who reported not using a condom with a sex worker, reasons included not liking condoms (20.0%), lack of planning (20.0%), using another contraceptive method (20.0%), a belief that condoms were unnecessary (13.3%), and lack of availability (13.3%).

There was a statistically significant decreasing trend (p < .05) in the condom use as participants became older (test for trend of odds). However, this difference was not necessarily significant between age groups when stratified by partner type (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Condom use by age and partner

We analyzed the association between alcohol consumption before sex and condom use during the participants’ last sexual contact. Among all survey participants, the frequency of condom use was 25.1% (n = 272) among people who drank before sex and 19.4% (n = 1,038) among those who did not drink before sex (z = 2.07, p = .03). Regardless of the sex partner type, a higher rate of condom use was found after alcohol consumption. Other variables that showed significance in the bivariate analysis were gender (women 16.53% [n = 98] vs. men 20.74% [n = 1,207]; z = 7.87, p < .05) and being in either the police or armed forces (17.38% [n = 655] vs. 24.78% [n = 665], respectively; z = −3.29, p < .01).

Regardless of the partner type, women and personnel from the police force were less likely to have used a condom in their last sexual encounter (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.68, p < .01 and AOR = 0.64, p < .01, respectively). This analysis did not find an association between alcohol consumption prior to the sexual encounter and condom use (AOR = 1.10, p = .28).

Multivariate analysis to assess condom use according to partner type adjusted for personnel type (military or police), age, and sex, showed an increasing chance of condom use in the last sex contact with less stable sex partners (Table 2).

Table 2.

AOR for Condom Use Among Military Personnel and Police Agents, Peru, 2006–2007 (n = 6245)

| Partner Type | AORa | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable partner | Reference | — | — |

| Nonstable partner | 1.84 | [1.53, 2.22] | <.01 |

| Sex worker | 13.53 | [7.17, 25.56] | <.01 |

Note: AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for personnel type (military or police), age, and gender.

Discussion

Condoms have been widely described as an effective method for preventing the transmission of STIs and HIV when they are used properly and consistently (Minnis & Padian, 2005; Niccolai, Rowhani-Rahbar, Jenkins, Green, & Dunne, 2005). Despite sexual health education and condom promotion in the military, condom use is still inconsistent in this population (Baser et al., 2007; Norris, Phillips, Statton, & Pearson, 2005; Tavarez, Chun, & Anastario, 2011), probably because the information provided is not comprehensive enough and has not been tailored to this population. Previous publications have described the reasons given by military populations for not using condoms. These include not having a condom available (Bauman, Karasz, & Hamilton, 2007; Crosby, Graham, Yarber, & Sanders, 2004), substance use before or during sex (Jemmott & Brown, 2003), trying to avoid demonstration of distrust (Duncan et al., 2002), being in a steady relationship (Bauman et al., 2007), and reduction of sexual pleasure (Bauman et al., 2007). All these were mentioned by this Peruvian population. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study in a primarily male military population to describe the participants’ belief that condom use is not necessary since their sex partners are using another contraceptive method. This may suggest that participants use condoms to avoid pregnancy more than to prevent STIs/HIV and that participants may not consider their sex partners a risk for transmission of STIs. This issue may need to be addressed in future interventions.

The survey used in this study did not specifically address why participants believe that condom use was unnecessary. However, the belief that condoms are not necessary with high-risk partners may be because of several factors. It has been described that during training military and police personnel may start to feel invulnerable (Okulate, Jones, & Olorunda, 2008), which can lead to risky behaviors including unsafe sex practices (Brodine et al., 1995). Additional reasons for nonuse of condoms may be that respondents trusted in the contraceptive method that the sex partners said they were using, or they believed that they could identify who might have an STI by the partner’s background. This may explain why we observed higher rates of condom use with sex workers, but low rates with nonstable sex partners such as friends and other casual partners, as has been seen in other populations (Westercamp et al., 2008). Therefore, the use of condoms in this population may be limited by a subjective assessment of the partner and the context in which sex occurs. Considering that almost 25% of this population had their last sexual encounter with a nonstable partner, this situation is concerning.

Previous research has shown that the military population reports less consistent condom use when they have stable and nonstable partners in the same timeframe compared with when they have nonstable partners only (von Sadovszky, Ryan-Wenger, Germann, Evans, & Fortney, 2008). Considering that 12.5% of the married participants in this study had their last sexual contact with someone other than their spouse, this subgroup may be placing not only themselves but also their stable partners at risk. This finding suggests the importance of studying the interactions of members of the armed forces with each of their sex partners to assess the frequency of partner concurrency in this population and its importance in STI transmission.

The survey asked about ever having anal sex, but it did not ask about the type of sex during the last sexual encounter. Given that a portion of this population considers the condom as a contraceptive method and that 45% of the participants indicated ever having had anal sex, it is likely that at least some anal sex is being performed without the use of a condom, probably increasing the risk of STIs including HIV. In future surveys, information on condom use for anal sex should be collected to quantify this risk. Furthermore, this survey did not include questions about same-sex sexual contacts. This is still an extremely sensitive topic in the uniformed services. We understand that this might be a study limitation and the results shown may provide an incomplete picture of this population’s sexuality. However, we believe that the information provided depicts fairly accurately the perception and conduct related to condom use.

Alcohol consumption is widely accepted as a risk factor for inconsistent condom use; however, this was not seen in our data. The questionnaire used for this study included a question about alcohol consumption prior to sex, but the amount consumed was not determined. This may explain why there was no significant difference in condom use after alcohol consumption across all types of sex partners.

Due to the activities inherent in active military personnel operations, we were unable to estimate the exact number of individuals stationed at each site (therefore no denominator was available to perform further analyses). Nonetheless, we believe that the large sample size in this study allowed for consistent and accurate results.

A finding of interest in this study was gender as a risk factor for inconsistent condom use, since women were less likely to have used a condom in their last sexual encounter. In light of the fact that most females acquire STI infections while in a steady relationship (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2004), the issue of empowerment seems crucial; furthermore, for women in a military institution gender–power imbalances could be even more significant. This study was not designed to address these issues and most participants were male. Previous publications show gender-tailored studies and interventions (Essien et al., 2010; Essien et al., 2011) allowing a better assessment of female military personnel’s perception on condom use. The use of these models in the population here studied could show very interesting data.

Future studies in this population should assess the individuals’ perception of their sex partners’ STI risk, and behavioral results should be linked to serological samples to analyze the relationship between sexual risk behaviors and positive serology for STIs and HIV.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into male perspectives on an important dimension of sexual health—condom use with different types of sex partners and reasons for nonuse of this key prevention method. Results show that a portion of the studied population believes that they can assess the risk of acquiring an STI through a subjective assessment of their sex partners and the context in which sex occurs, an assessment that is often flawed and risky. In addition, many participants rely on their partner using another contraceptive method. This implies that some individuals consider condoms primarily as a contraceptive method versus a means to avoid STIs.

Since military and police personnel are primarily young, healthy, and sexually active, these findings are difficult to generalize to the general population. However, given similar cultural background in the region, condom use may be similar in other Latin American military and police populations of the region. Current programs in family planning and STI prevention aim to link sexual responsibility (STI prevention, family planning, etc.) to both genders (Drennan, 1998). The information provided in this study can be used to improve interventions tailored to the needs of the military and police population in Peru who are primarily male and report risk behaviors including a lack of condom use with nonprimary partners that require intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their recognition and gratitude to the COPRECOS team: Tte. Crl. SAN. EP Rafael Rodríguez Bayona and Crl. FAP Méd.(r) Carlos Castro Farro for their hard work, experience, and support during the field work. Special thanks go to Crl. SAN. EP Luis Fernando Gutierrez from the Peruvian Ministry of Defense, C. de N. SN Victor Vallejos Sandoval and Gral.FAP Méd(r) Juan Alva Lescano, former Presidents of COPRECOS, and the Peruvian Ministry of Defense and Interior Affairs authorities for making this study possible.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by DHAPP (Work Unit Number RA317) and (R8207) USAID-PAPA-ETD

Footnotes

Authors’ Note

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government, Department of Defense nor Peruvian Government. The study protocol was approved by PJT-NMRCD.011. Some of the authors are military service members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a U.S. Government work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Baser M, Tasci S, Albayrak E. Commandos do not use condoms. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2007;18:823–826. doi: 10.1258/095646207782717072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman L, Karasz A, Hamilton A. Understanding failure of condom use intention among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2007;22:248–274. [Google Scholar]

- Brodine SK, Garland FC, Mascola JR, Porter KR, Mascola JR, Artenstein AW, McCutchan FE. Detection of diverse HIV-1 genetic subtypes in the USA. Lancet. 1995;346:1198–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture MC, Soto JC, Akom E, Labbe AC, Joseph G, Zunzunegui MV. Clients of female sex workers in Gonaives and St-Marc, Haiti characteristics, sexually transmitted infection prevalence and risk factors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35:849–855. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318177ec5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, Graham CA, Yarber WL, Sanders SA. If the condom fits, wear it: A qualitative study of young African-American men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80:306–309. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.008227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drennan M. Reproductive health. New perspectives on men’s participation. Population Reports. 1998 Oct;:1–35. (Series J, No. 46) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C, Miller DM, Borskey EJ, Fomby B, Dawson P, Davis L. Barriers to safer sex practices among African American college students. Journal of National Medical Association. 2002;94:944–951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essien EJ, Mgbere O, Monjok E, Ekong E, Holstad MM, Kalichman SC. Effectiveness of a video-based motivational skills-building HIV risk-reduction intervention for female military personnel. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essien EJ, Monjok E, Chen H, Abughosh S, Ekong E, Peters RJ, Mgbere O. Correlates of HIV knowledge and sexual risk behaviors among female military personnel. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:1401–1414. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9701-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Brown EJ. Reducing HIV sexual risk among African American women who use drugs: Hearing their voices. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2003;14(1):19–26. doi: 10.1177/1055329002239187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. HIV prevention and protection efforts are failing women and girls. London, England: Author; 2004. Feb, (Press release) [Google Scholar]

- Minnis AM, Padian NS. Effectiveness of female controlled barrier methods in preventing sexually transmitted infections and HIV: Current evidence and future research directions. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:193–200. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niccolai LM, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Jenkins H, Green S, Dunne DW. Condom effectiveness for prevention of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:323–325. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris AE, Phillips RE, Statton MA, Pearson TA. Condom use by male, enlisted, deployed navy personnel with multiple partners. Military Medicine. 2005;170:898–904. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.10.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okulate GT, Jones OB, Olorunda MB. Condom use and other HIV risk issues among Nigerian soldiers: Challenges for identifying peer educators. AIDS Care. 2008;20:911–916. doi: 10.1080/09540120701777264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samnang P, Leng HB, Kim A, Canchola A, Moss A, Mandel JS, Page-Shafer K. HIV prevalence and risk factors among fishermen in Sihanouk Ville, Cambodia. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2004;15:479–483. doi: 10.1258/0956462041211315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopheab H, Fylkesnes K, Vun MC, O’Farrell N. HIV-related risk behaviors in Cambodia and effects of mobility. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41:81–86. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174654.25535.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavarez M, Chun H, Anastario MP. Correlates of sexual risk behavior in sexually active male military personnel stationed along border-crossing zones in the Dominican Republic. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2011;5:65–77. doi: 10.1177/1557988310362097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans D. Men’s role in reproductive health: Family planning is a family affair. Entre Nous Copenhagen Denmark, May. 1996;(32):8–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme/United Nations Population Fund/World Health Organization. Programming for male involvement in reproductive health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- von Sadovszky V, Ryan-Wenger N, Germann S, Evans M, Fortney C. Army women’s reasons for condom use and nonuse. Women’s Health Issues. 2008;18:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westercamp N, Mattson CL, Madonia M, Moses S, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola JO, Bailey RC. Determinants of consistent condom use vary by partner type among young men in Kisumu, Kenya: A multi-level data analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;14:949–959. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9458-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]