Abstract

The fundamental separation of Golgi function between subcompartments termed cisternae is conserved across all eukaryotes. Likewise, Rab proteins, small GTPases of the Ras superfamily, are putative common coordinators of Golgi organization and protein transport. However, despite sequence conservation, e.g., Rab6 and Ypt6 are conserved proteins between humans and yeast, the fundamental organization of the organelle can vary profoundly. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Golgi cisternae are physically separated from one another, while in mammalian cells, the cisternae are stacked one upon the other. Moreover, in mammalian cells, many Golgi stacks are typically linked together to generate a ribbon structure. Do evolutionarily conserved Rab proteins regulate secretory membrane trafficking and diverse Golgi organization in a common manner? In mammalian cells, some Golgi-associated Rab proteins function in coordination of protein transport and maintenance of Golgi organization. These include Rab6, Rab33B, Rab1, Rab2, Rab18, and Rab43. In yeast, these include Ypt1, Ypt32, and Ypt6. Here, based on evidence from both yeast and mammalian cells, we speculate on the essential role of Rab proteins in Golgi organization and protein transport.

Keywords: Rab proteins, Golgi apparatus, Membrane trafficking, Golgi organization

Golgi structural features and their role in membrane trafficking

The Golgi apparatus (also known as the Golgi complex) has attracted many cell biologists since it was discovered [1–3]. Universally, the Golgi apparatus consists of a series of flattened, disc-shaped membrane limited subcompartments called cisternae. Based upon their arrangement within cells, these subcompartments were termed cis, medial, and trans by electron microscopists in the 1950s to 1960s and, despite the later dominance of the field by biochemists and molecular cell biologists, the original terminology has stuck [1]. Today, these Golgi subcompartments are typically defined by differences in resident protein composition and function rather than morphology [4–6]. In mammalian cells, the cisternae are aligned in parallel to generate the Golgi stack and often, but not in all mammalian cell types, Golgi stacks are then linked together to form a juxtanuclear ribbon structure. This feature is essential to normal Golgi-specific protein glycosylation and sorting [7–9]. In yeast, the Golgi organization varies between different yeast species. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Golgi cisternae are isolated, i.e., not associated with each other, while in Pichia pastoris and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the Golgi cisternae are associated into individual, isolated stacks (Fig. 1). Experimentally, S. cerevisiae is the standard laboratory yeast. It is the creature of choice for most genetic studies on the role of the Golgi apparatus in the secretory pathway [10, 11]. In plants, individual rather than linked Golgi stacks are the norm [12].

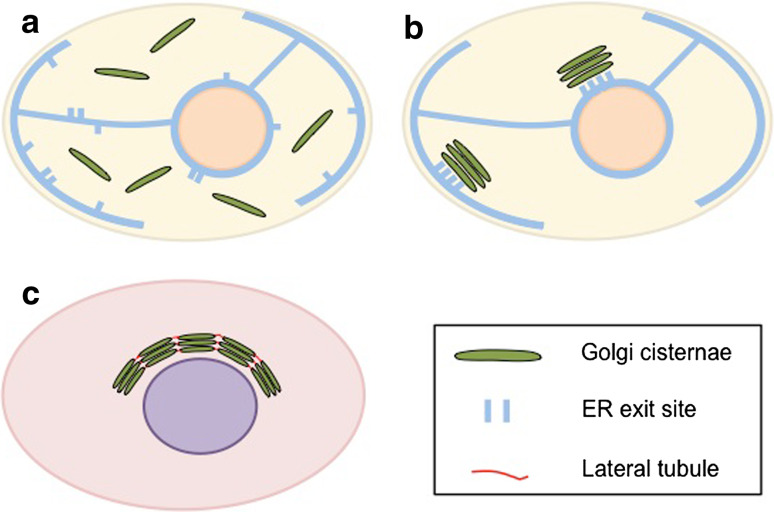

Fig. 1.

Golgi organization varies among different cells and species. a In S. cerevisiae, Golgi cisternae present throughout the cytoplasm individually. b In S. pombe and P. pastoris, cisternae are aligned in parallel to generate the Golgi stack. c In mammalian cells, several Golgi stacks are typically linked together to form a ribbon structure

Despite the different Golgi organization between the yeast S. cerevisiae and mammalian cells, the overall mechanism of membrane trafficking is similar. In both, the Golgi apparatus plays a central role in membrane trafficking pathways. It receives newly synthesized proteins and lipids from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) via COPII-coated vesicles. Within the Golgi apparatus, many of these are modified sequentially by glycosidases and glycosyltransferases as they transit from cis to trans through the Golgi apparatus. Finally, these cargo components are sorted via trans Golgi network (TGN), and transported to the plasma membrane or other intracellular organelles. The above process, anterograde membrane trafficking, delivers newly synthesized proteins from the ER via the Golgi apparatus to the cell surface and is termed overall the secretory pathway [13–16]. However, most, if not all, transport between organelles is in two directions. So, the Golgi apparatus also occupies a central position in retrograde membrane trafficking which returns escaped ER resident proteins and other machinery that cycles between the ER and Golgi back to their site of origin [17, 18]. Together, the Golgi mediates significant steps in bidirectional transport that must be well counterbalanced [19]. In addition, other proteins such as bacterial toxins or viral assembly intermediates may piggyback on these pathways [20].

The Golgi apparatus is a highly dynamic organelle, yet it manages to maintain ordered structure to ensure that cargo proteins are correctly modified and efficiently sorted. Continuous membrane trafficking is essential to maintain Golgi homeostasis [21–23]. Thus, like other organelles, the varied functions of the Golgi apparatus are linked with its organization. However, how the linkage between organization and function for the Golgi apparatus is achieved remains poorly understood. Here, we use Rab proteins, important molecular switches, to illustrate both the extent and the limits of our understanding.

Rab proteins and their effectors

Rab proteins are the largest family of small Ras-like GTPases. Recent analysis indicates that there are over 60 members in the human genome while 11 members identified in the yeast, S. cerevisiae. Besides humans and yeast, Rab proteins have been found in essentially all eukaryotes. This wide distribution suggests that they play key roles in eukaryotic cells [24–27]. In yeast and mammalian cells, Rab proteins are probably central regulatory factors in membrane trafficking and involved in almost all steps of vesicle transport (Fig. 2) [28, 29]. For instance, Rab5 regulates protein trafficking from plasma membrane to early endosomes. Overexpression of Rab5-ile133, in which GTP binding activity is inhibited, results in both endocytic trafficking defects and disruption of the structure of early endosomes into small tubules and vesicles. Moreover, the major Rab5 effector, EEA1, has been shown to function in endocytic vesicle tethering and fusion [30, 31]. In yeast, the Rab protein Sec4 interacts with an exocyst component Sec15 that is important in vesicle trafficking and tethering [32].

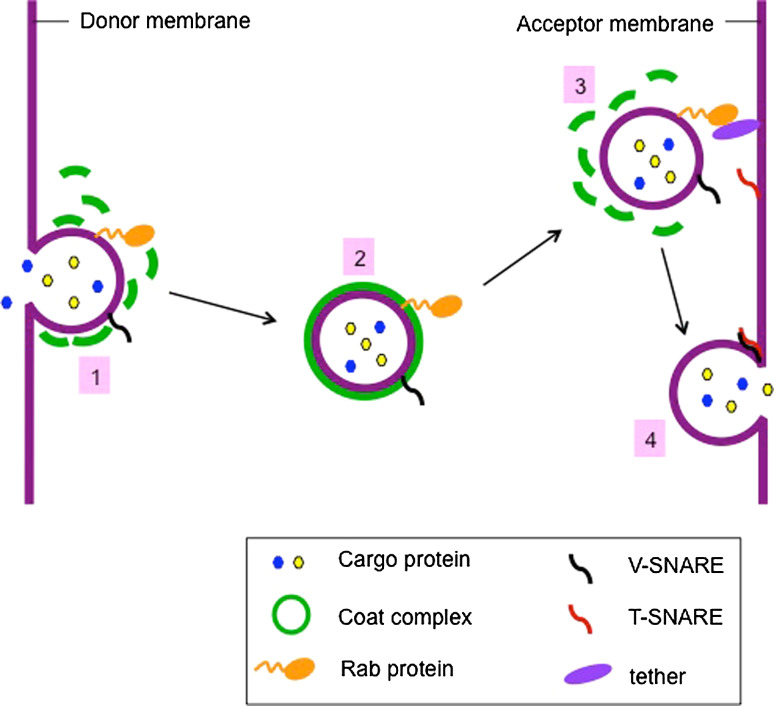

Fig. 2.

Rab proteins are involved in almost all steps of vesicle transport. (1) The transport vesicles are formed by recruitment of coat complex and Rab proteins, both of which are essential for cargo selection. (2) The vesicle transports to acceptor membrane along cytoskeleton with the help of Rab proteins. (3) Rab proteins interact with tethering factors to tether the vesicle to the acceptor membrane. (4) t-SNARE and v-SNARE link with each other to form a SNARE complex, which leads to membrane fusion and cargo delivery

Structurally, Rab proteins share a fold common to GTPases of the Ras superfamily (Fig. 3). This fold consists of a six-stranded β sheet, five strands of which are parallel and one antiparallel, and five α helices that surround them. At the COOH terminus of all Rab proteins is a hypervariable region composed of ~35–40 amino-acid residues and a downstream double-cysteine prenylation motif. Replacement of Rab 1 or Rab5 hypervariable region by that of Rab9 can lead to the interaction of Rab9 effector TIP47 with the chimeric Rabs. Furthermore, the Rab1/9 and Rab5/9 hybrids relocalize from Golgi or early endosome to late endosome that contain Rab9 normally when TIP47 is co-expressed. Thus, the hypervariable domain together with certain effectors probably specifies distinct localizations of Rab proteins [35–37]. Sequence analysis shows the presence of two kinds of additional conserved regions in Rab proteins: five RabF regions and four RabSF regions. The former distinguishes Rab proteins from other members of the Ras superfamily. The latter can be used to define subfamilies of Rabs and is proposed to determine the specific binding site of effector proteins that interact with the respective Rab protein [38–41]. For example, studies by Ostermeier and Brunger [42] demonstrated that there are three complementarity-determining regions of Rab3A. These regions, which occupy three of the four RabSF regions, are important for Rab3A binding to its effector, rabphilin.

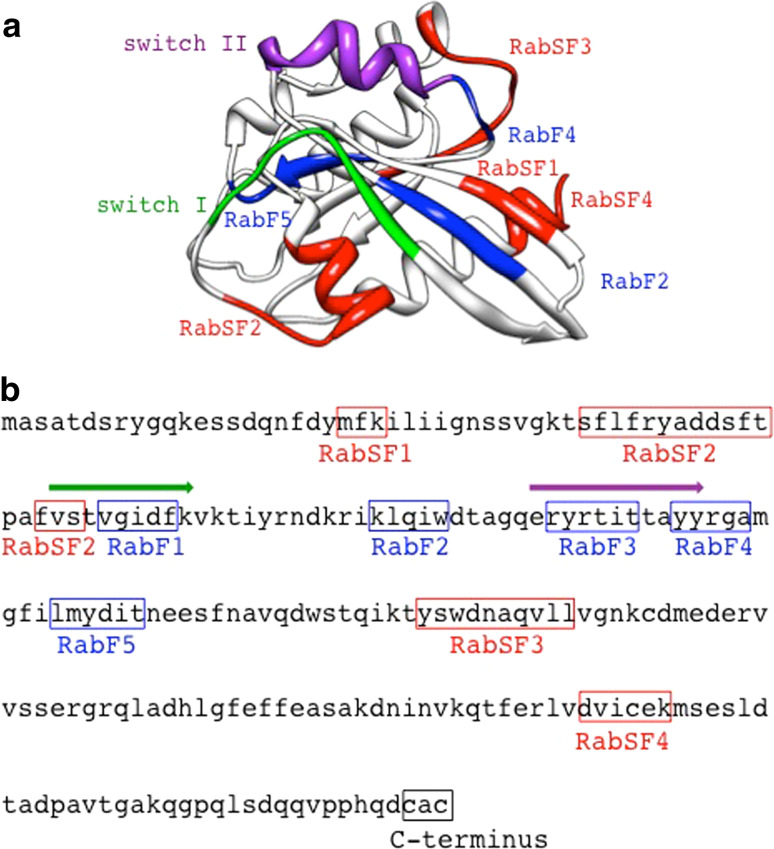

Fig. 3.

Structure analysis of a representative Rab protein, Rab3A. a Ribbon structure of Rab3A with functional regions colored as indicated (RabF1 and RabF3 are not shown since they are localized in switch I and switch II regions, respectively). This figure was rendered using available coordinates [33] and UCSF Chimera software [34]. b Amino-acid sequence of Rab3A and functional regions as indicated. The green arrow highlights the switch I region, while the purple arrow shows the switch II region

In acting as molecular switches, Rab proteins recruit effectors in the GTP-bound state and are switched off in the GDP-bound state. Switch I and switch II regions are crucially responsive to the nucleotide-bound state. They are well ordered when the Rab protein is GTP bound and disordered when it is GDP bound [36, 43, 44]. An early illustrative example comes from Sec4, the first discovered member of the Rab family in yeast. Its GDP-bound structure displays poor order for switch I residues 48–56 and switch II residues 76–93 [45]. Rab switch regions also contribute to the binding of effectors [46].

Rab proteins are associated in a chaperone-like manner with a number of distinct protein partners. Newly synthesized Rab protein is recognized by a Rab escort protein (REP), which presents the Rab to geranylgeranyl transferases for modification [47, 48]. With the help of a GDP dissociation inhibitor displacement factor (GDF), Rab proteins are delivered to the appropriate membrane (Fig. 4) [49–51]. At the same time, GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) is released and the exchange of GDP with GTP is catalyzed by a GDP/GTP exchange factor (GEF). The active Rab can then bind effectors and regulate membrane trafficking. After the Rab interacts with a GTPase-activating protein (GAP), the Rab protein hydrolyzes GTP to GDP and the Rab protein is converted from the GTP-bound state to GDP-bound state that is effector inactive [33, 52]. The inactive Rab will be released from the membrane and recycled back to the cytosol in the presence of GDI (Fig. 4). The inactive Rab bound by GDI can then be recycled as illustrated in Fig. 4. Interestingly, GDIs recognize general features of prenylated Rab proteins. Humans have only two expressed GDI proteins, while yeast has only one GDI protein, but they can interact with all of the different GDP-bound Rab proteins [53, 54].

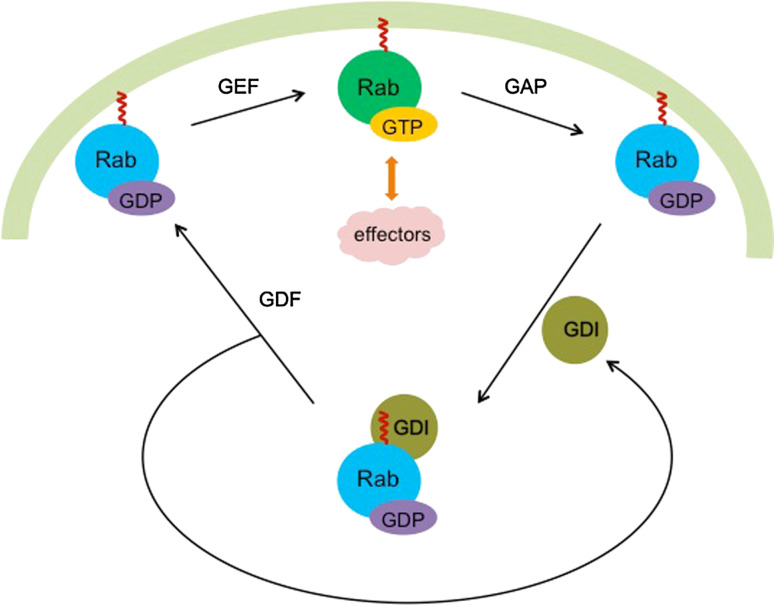

Fig. 4.

Rab proteins cycle between different nucleotide-bound states. GDF (GDI displacement factor) displaces GDI (GDP dissociation inhibitor) from GDP-Rab and facilities Rab protein anchoring to the target membrane. Meanwhile, GEF (GDP/GTP exchange factor) functions to exchange GDP with GTP. Therefore, Rab protein is activated and able to regulate the membrane trafficking with the help of effectors. Finally, catalyzed by GAP (GTPase-activating protein), the bound GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP. The inactive Rab will be recycled back to cytosol by interacting with GDI

Rab proteins are involved in regulating membrane trafficking through the recruitment of effector molecules. Trafficking-specific effector proteins selectively bind Rab proteins in the GTP-bound state [55]. Individual Rab proteins can interact with a variety of different effectors and moreover, an individual effector can be shared by several related Rab proteins. For example, the effector of Rab3A, Rabphilin, can interact with Rab3B/3C/3D, as well as Rab27A/B [56–59]. Rab effectors are typically associated with each step of membrane trafficking and are likely recruited in a manner that is sensitive to local molecular context. During vesicle formation, for example, the well-characterized Rab9 effector, TIP47, binds to the cytoplasmic domain of mannose 6-phosphate receptors (MPRs). MPRs are then recycled from late endosomes to the TGN. Rab9, principally localized to late endosomes, increases the interaction of TIP47 with MPRs, and hence MPRs are concentrated to Rab9 vesicles [37, 60]. In addition, Rab proteins and their effectors are implicated in regulation of vesicle transport along actin or microtubule structures. Rab27a regulates melanosome transport to the plasma membrane in melanocytes. It has been demonstrated that in this process, melanosome Rab27a interacts with myosin Va on actin filaments via the Rab27a effector melanophilin [61–63]. Rab6 effectors Bicaudal D1/D2 have a role in linking Rab6-containing vesicles and the microtubule motors [64]. Rab proteins also interact with vesicle tethers of both the long coiled-coil protein class and multiprotein complex class [30, 65, 66]. Moreover, SNARE-associated vesicle fusion to the target membrane is involved with Rab proteins and effectors as well [67, 68].

Rab proteins are associated with the Golgi organization and trafficking

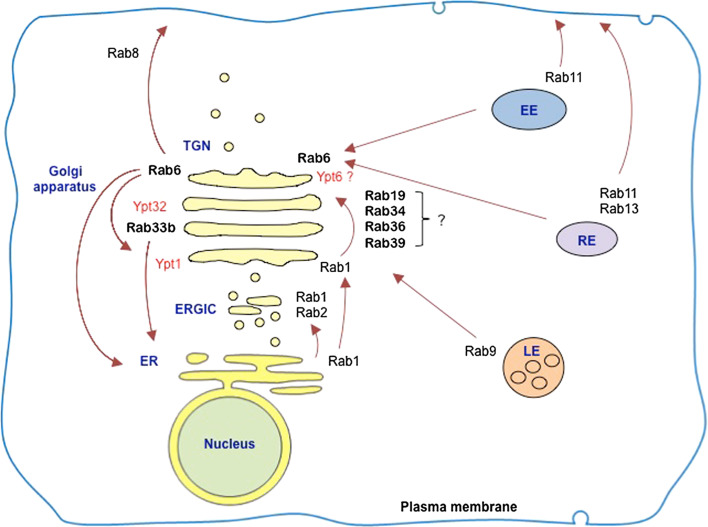

Rab proteins associated with the Golgi apparatus in humans and yeast can be arranged along a cis to trans axis (Fig. 5). Ypt1/Rab1 and Ypt6/Rab6, which are found in yeast and humans, respectively, are orthologues. As noted earlier, despite this molecular conservation, Golgi organization in the yeast S. cerevisiae and in mammalian cells is very different. The cisternae in S. cerevisiae are separated from one another, while in the mammalian cells they are associated into a stack [10]. Does the lack of conserved Golgi organization indicate that the key role of Rab proteins in Golgi structure/function relationships is trafficking not organelle structure, i.e., are trafficking and organelle structure uncoupled here? Among the 60 or more members of Rab family in mammalian cells, several are associated with the Golgi apparatus (Table 1). Some Rab proteins are associated primarily with the Golgi apparatus, including Rab6A/A′, Rab19, Rab33A, Rab33B, Rab34, Rab36, and Rab39, some also localize to other organelles besides the Golgi apparatus. However, all these Golgi-associated Rab proteins in mammalian cells are involved in membrane trafficking from/to or through the Golgi [24, 28, 40]. So it can be suggested that some, if not all, of these Golgi-associated Rab proteins should be linked with the coordination of Golgi organization and trafficking.

Fig. 5.

Localizations and transport pathways of major Golgi-associated Rab proteins in mammalian cells. Localizations of yeast Ypt1, Ypt6, and Ypt32 relative to the Golgi apparatus are also shown. Major Rabs involved in peripheral membrane trafficking are also included in the figure. ER endoplasmic reticulum, LE late endosome, RE recycling endosome, EE early endosome

Table 1.

Golgi-associated Rabs and their effectors in mammalian cells

| Rab | Isoform | Expression | Localization | Transport step | Effector | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rab1 | Rab1A | U | ER, Golgi, ERGIC | ER-to-Golgi, intra Golgi | p115, GM130, giantin, GRASP65, golgin-84, Cog6, OCRL1, MICAL-1, MICAL-cI, INPP5B | [65, 69–77] |

| Rab1B | ||||||

| Rab2 | Rab2A | U | ERGIC | ER-to-Golgi | golgin-45, GM130, GRASP55, GARI-L3, INPP5B | [71, 78–80] |

| Rab2B | ||||||

| Rab6 | Rab6A | U | Golgi | Endosome-to-Golgi, Golgi-to-ER, intra Golgi | golgin-97, GCC185, TMF/ARA160, myosin II, Kif1C, Kif5B, GAPCenA, Rab6IP2/ELKS, Rab6IP1, OCRL1, Bicaudal-D1, INPP5B, BICDR-1a, Rabkinesin-6b | [64, 72, 78, 81–85] |

| Rab6A′ | ||||||

| Rab6B | Brain | ER, Golgi, ERGIC | Golgi-to-ER | |||

| Rab9 | Rab9A | U | LE | LE-to-Golgi | p40, GCC185, TIP47, INPP5B | [37, 71, 78, 86–88] |

| Rab9B | LE, Golgi | |||||

| Rab10 | Rab10 | U | Golgi, basolateral sorting endosome | Golgi-to-basolateral membrane | MICAL-1, MICAL-cI, MICAL-like1, MICAL-like2, Smchd1 | [24, 78, 89] |

| Rab11 | Rab11A | U | RE, Golgi, EE | Transport from Golgi to plasma membrane through the RE | Rab11BP, FIP2, FIP5, RCP, Rab3ip, Smchd1 | [78, 90–94] |

| Rab11B | ||||||

| Rab12 | Rab12 | U | Golgi, secretory vesicles | Unknown | RILP-L1, Smchd1 | [24, 78, 95, 96] |

| Rab13 | Rab13 | Tight junction EC | Golgi, RE | Transport from Golgi to plasma membrane through the RE | INPP5B, MICAL-1, MICAL-cI, MICAL-like1, MICAL-like2 | [78, 97, 98] |

| Rab14 | Rab14 | U | Golgi, EE | Between the Golgi and endosomal compartments | OCRL1, Akap10, FIP2, RCP, Rip11, RUFY1 | [72, 78, 99–102] |

| Rab18 | Rab18 | U | Golgi, ER, endosome, lipid droplets | Between ER and Golgi | Unknown | [103–108] |

| Rab19 | Rab19 | Intestine, lung, spleen | Golgi | Unknown | Wdr38 | [24, 109] |

| Rab20 | Rab20 | Kidney tubule EC | Golgi, endosome | Unknown | INPP5E | [24, 78, 104, 110] |

| Rab30 | Rab30 | U | ER, Golgi | Unknown | Cog4, Golga4 | [24, 78, 111–113] |

| Rab33 | Rab33A | Brain, immune system | Golgi | Golgi-to-ER | Atg16L, rabaptin-5, rabex-5, GM130 | [114–118] |

| Rab33B | U | |||||

| Rab34 | Rab34 | U | Golgi | Intra Golgi | RILP, hmunc13 | [119–121] |

| Rab36 | Rab36 | U | Golgi | Unknown | MICAL-1, MICAL-like1, RILP, Smchd1 | [78, 122, 123] |

| Rab39 | Rab39 | U | Golgi | Unknown | Caspase-1 | [124, 125] |

| Rab40 | Rab40A | U | Golgi, RE | Unknown | Akap10, RME-8 | [24, 78, 126, 127] |

| Rab40B | ||||||

| Rab40C | ||||||

| Rab43 | Rab43 | U | ER, Golgi | ER-to-Golgi | Unknown | [103, 128] |

U ubiquitous, ER endoplasmic reticulum, LE late endosome, RE recycling endosome, EE early endosome, EC epithelial cells

aInteraction between Rab6B and BICDR-1 is ill defined

bRabkinesin-6 doesn’t interact with Rab6A′

To date, two systematic screening approaches have been taken for the identification of the role of Rab proteins in Golgi organization. The first is a RNA interference approach by the Malhotra laboratory [129]. 284 dsRNAs were used to carry out a genome-wide RNA interference screen in Drosophila S2 cells to identify genes that affect protein secretion. Among these genes, two Rab proteins were included, Rab1 and Rab11. They found that knockdown of Rab1 produced an equivalent phenotype to an ER exit mutation in which metabolically stable Golgi membrane proteins accumulated through cycling in the ER, while depletion of Rab11 caused no apparent effect on Golgi organization. The second is a GAP-based screen by the Barr laboratory [128]. Here the concept is that the TBC domain could be used to identify human Rab GAPs and then overexpression of these in cells could be used to screen for the functional importance of the Rabs. In this screen of 38 human GAPs containing the TBC domain, Haas et al. [128] identified two Rab proteins Rab1 and Rab43 that were essential for the maintenance of the Golgi ribbon structure. They suggested that functions of other Rab proteins at the Golgi apparatus were probably redundant, and hence no individual function in Golgi organization could be identified in their screen. However, based on individual protein studies, besides Rab1 and Rab43, other Rab proteins, including Rab2, Rab6, Rab18, and Rab33B, have been assigned key roles in the regulation of Golgi organization and protein trafficking. We now highlight the trafficking and organizational role of an illustrative subset of these proteins. Some appear to exert their effect by being essential to Golgi ribbon organization or stacking while others appear to affect primarily Golgi trafficking.

Rab6 regulates Golgi trafficking and Golgi organization

Rab6 is one of the most extensively studied Rab proteins involved in regulating Golgi trafficking, maintaining its integrity, and its steady-state homeostasis. Rab6 has four isoforms in mammalian cells, Rab6A, Rab6A′, Rab6B, and Rab6C. Rab6A and Rab6A′ are the products of alternate splicing of the Rab6A gene [130]. The two forms differ in only three amino acid residues present in a region flanking the GTP-binding domain. Both Rab6A and Rab6A′ are ubiquitously expressed at similar levels, localized to the trans-Golgi cisternae and TGN membranes, and display the same GTP-binding properties [82, 131]. They are sufficiently similar in biochemical and genetic properties that they are collectively referred to as Rab6. Another isoform, Rab6B, is predominantly expressed in brain. Rab6B shows 91 % identity to Rab6A and is encoded by a different gene. The amino acid differences are mainly scattered in the C-terminal region of the proteins. Rab6B localizes to the Golgi apparatus, ER, and ER Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). In addition, the GTP-binding activity of Rab6B is lower than Rab6A in vitro [83]. The final member of Rab6 gene family, Rab6C, shows 75 % identity to Rab6A′. Much of the sequence divergence is due to a 46-amino-acid extension after the hypervariable region at the COOH terminus of the protein. Rab6C is only expressed in brain, testis, prostate, and breast. Moreover, unlike the other three isoforms, Rab6C labeled with GFP does not localize to the Golgi apparatus but rather predominantly to centrosomes. Rab6C is involved in regulation of cell cycle progression [84].

Among the four isoforms of Rab6, the role of Rab6A and Rab6A′ have been studied most extensively. Overexpression of either wild-type or the GTP-restricted mutant (Q72L) of Rab6A redistributed β-1,4-galactosyltransferase, a trans-Golgi resident glycosyltransferase, to the ER, while overexpression of its GDP-restricted mutant (T27N) inhibited retrograde transport through the Golgi apparatus [132–134]. These experiments were central to the concept that Rab6A coordinated a retrograde transport route from Golgi to ER. Importantly, they indicate in a dramatic manner that balanced Rab protein activity is central to Golgi organization. There exist at least two independent pathways in Golgi-to-ER trafficking. One is COPI-independent and specifically regulated by Rab6. Golgi glycosylation enzymes and Shiga toxin/Shiga-like toxin-1, for example, transport from Golgi to ER by this pathway [135, 136]. The other is COPI-dependent and Rab6-independent. Example proteins include the KDEL receptor, KDEL-containing toxins, and ERGIC-53 as it cycles to the ERGIC and ER [137, 138]. How COPI-independent trafficking occurs remains poorly understood.

Rab6A′ has been reported to be involved in the Shiga toxin transport from early/recycling endosomes to the TGN of Golgi apparatus. So it seems that Rab6A and Rab6A′ may act sequentially to regulate the retrograde transport from endosomes to the ER; Rab6A′ would stimulate transport from endosomes to TGN, while Rab6A would regulate Golgi-to-ER transport [115, 138, 139]. However, several lines of evidence are consistent with the functions of Rab6A and Rab6A′ being redundant. Utskarpen et al. [140], taking an siRNA approach, showed that both Rab6A and Rab6A′ are probably involved in the ricin transport from endosomes to the Golgi. Young et al. [141] found that knockdown of either Rab6A or Rab6A′ by RNAi delayed Golgi-resident protein recycling to the ER. When both Rab6A and Rab6A′ are down-regulated, the Golgi ribbon is more condensed. In contrast, depletion of either Rab6A or Rab6A′ gave a 50 % decrease in total Rab6 protein level and almost a total depletion of the respective isoform. Depletion of either Rab6A or Rab6A′ alone produced no obvious change in the Golgi ribbon by fluorescence microscopy [141]. The two Rab6 isoforms could well be functionally redundant.

Rab6 is also involved in anterograde trafficking from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. Rab6 and its effector myosin II are required for the regulation of vesicle fission from Golgi apparatus [142]. Rab6 in the GTP-bound form can bind to the coiled-coil motif of the motor protein, myosin II, and recruit it to Golgi apparatus. Depletion of either Rab6 or myosin II by RNAi inhibited fission of Rab6-positive transport carriers and correspondingly the number of free Rab6-positive transport carriers was reduced. Inhibition of both Rab6 and myosin II did not cause a significantly different phenotype than was observed for either alone, suggesting that they probably act in the same pathway [142, 143]. Other Rabs and myosins including Rab8 and myosin VI are also involved in transport from Golgi to plasma membrane (see below). They may function sequentially in this pathway [143, 144]. In addition, Grigoriev et al. [145] found that Rab6 regulated exocytotic vesicles movement along microtubules to the cell periphery and directed targeting of these vesicles to the plasma membrane. Furthermore, recent studies indicate that exocytic vesicle docking and fusion with the plasma membrane promoted by Rab8A is also Rab6-dependent [146]. In mammalian cells, Rab8 has two isoforms, Rab8A and Rab8B, and is involved in trafficking from TGN to the plasma membrane [147]. Rab8A is associated with long tubules but not localized to the Golgi apparatus. It could be recruited to vesicles during or soon after they leave the Golgi region in the presence of Rab6. Rab8A is associated with Rab6-interacting cortical factor ELKS. A member of the MICAL family, MICAL3, may well serve to link these proteins within the same vesicle-trafficking pathway. If MICAL3 is mutated, the TGN-to-plasma membrane directed vesicles proliferate, dock at the cell cortex, but fail to fuse with the plasma membrane. So, as the authors suggest, two Rab proteins, Rab6 and Rab8A, together with MICAL3 cooperate in regulating vesicle docking and fusion [146].

Work from this laboratory, Sun et al. [148], and Storrie et al. [149] provide important evidence that Rab6 regulates Golgi organization through regulating Golgi trafficking. The initial work took an epistatic, double-knockdown approach, to identifying the role of Rab6 relative to the retrograde tether proteins ZW10/RINT-1, Golgi to ER, and the conserved oligomeric Golgi (COG) complex in Golgi trafficking and homeostasis. In mammalian cells, Zeste White 10 (ZW10), a mitotic checkpoint protein, is essential for retrograde trafficking from Golgi to the ER and Golgi organization. It links with RINT-1 and the ER SNARE syntaxin 18. Knockdown of ZW10 or RINT-1 by RNAi induces a clustered punctuate Golgi distribution, i.e., the Golgi ribbon fragments, and inhibits Golgi-to-ER trafficking [150–152]. Depletion of COG leads to a fragmented Golgi ribbon and the dispersal of Golgi vesicles rich in medial Golgi proteins [153, 154]. In epistatic, double-knockdown experiments, co-depletion of Rab6 inhibited the Golgi ribbon disruption induced by ZW10/RINT-1 or COG depletion and the accumulation of Golgi-derived vesicles. These results strongly indicate that Rab6 acts upstream of both tether complexes and transport of Golgi-derived vesicles. When Rab6 alone was depleted, electron tomography revealed that Golgi cisternal number and cisternal continuity increased and both COPI- and clathrin-coated vesicles and coated membrane fission/fusion figures accumulated. Significantly, depletion of the individual Rab6-effector, myosin IIA, induced a decrease in cisternal organization and the accumulation of uncoated vesicles [149]. These results provide strong evidence for a link between Rab6 and effectors that affects Golgi structure. The actual vesicles accumulated must be central to the affect as accumulation of coated vesicles resulted in cisternal proliferation while the accumulation of uncoated vesicles in the case of the myosin IIA knockdown resulted in decreased cisternal organization. These data provide the first indication that Rab6 can regulate, in a direct or indirect manner, Golgi-coated vesicle trafficking. Whether the link between Rab6 and the regulation of Golgi ribbon homeostasis is direct or a secondary consequence of membrane-trafficking effects, for example, on coated vesicle trafficking, remains an open question.

Relatively little is known regarding the role of Rab6B or Rab6C. Taking a yeast two-hybrid approach supported by co-immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down assays, Rab6B was found to interact with the large coiled-coil protein, Bicaudal-D1, a member of the dynactin complex that regulates the motor protein dynein [155, 156]. Bicaudal-D1 is a known effector of Rab6A/A′. The interaction of Rab6B and Bicaudal-D1 is involved in regulation of retrograde transport along microtubules in neuronal cells. Likely, Rab6A and Rab6A′ are also associated with Rab6B/Bicaudal-D1-mediated retrograde transport in neuronal cells [64, 155]. Recently, Bicaudal-D-related protein 1 (BICDR-1), which is sequence homologous to Bicaudal-D, was found to be a novel effector of Rab6A and Rab6A′. Presently, it is unknown whether BICDR-1 can interact with Rab6B. Such an interaction could be functionally important. In zebrafish, BICDR-1 can bind to dynein/dynactin complex as well as the kinesin motor Kif1C. Localization of Rab6 secretory vesicles in pericentrosomal and neuronal differentiation are regulated by BICDR-1 [85].

Rab33B and Rab6 overlap in the regulation of Golgi trafficking and organization

Rab33B is the only member of the Rab33 subfamily to be implicated in Golgi function. It is expressed ubiquitously across cell types [157–159]. We concentrate here on Rab33B because of its proven role in Golgi trafficking and organization. Immunoelectron microscopy analysis revealed that Rab33B was localized to the medial Golgi [159]. Similar information comes from confocal fluorescence microscopy [116]. Overexpression of GTP-restricted Rab33B relocalizes glycosyltransferases from the Golgi apparatus to the ER. Moreover, overexpression of GDP-restricted Rab33B inhibits the ER accumulation of Golgi-resident enzymes in a Sar1 mutant background [160]. Sar1 is a small GTPase required for ER exit. Depletion of Rab33B by RNAi impairs Shiga-like toxin B trafficking from Golgi apparatus to the ER, while anterograde trafficking of tsO45G protein through the Golgi apparatus is not affected [117]. The above results demonstrate that Rab33B plays an important role in Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport and in so doing can regulate Golgi apparatus homeostasis. Further work by Starr et al. [117] indicated that the Rab33B and Rab6 functioned together in COPI-independent retrograde trafficking. Like Rab6, knockdown of Rab33B inhibits the disruption of Golgi organization induced by ZW10- and COG3-depletion. Moreover, the relocation of Golgi enzymes to the ER induced by GTP-Rab6 overexpression is inhibited in the epistatic Rab33B-depletion experiment. However, when this experiment is reversed, there is no obvious effect of a Rab6 knockdown on the GTP-Rab33B induced redistribution of Golgi enzymes. Therefore, Rab33B probably acts downstream of Rab6. Overall, the above results indicate that Rab33B and Rab6 functionally overlap in regulating intra-Golgi retrograde transport pathway and Golgi homeostasis. The two Rab proteins may be related by a Rab cascade, i.e., one Rab recruits or stabilizes the membrane association of another Rab in the same pathway.

Rab1, Rab2, and their effectors are essential for ER-to-Golgi trafficking and the maintenance of the Golgi ribbon

Rab1 has two isoforms, named Rab1A and Rab1B, whose identity is 92 %. They can be found in the ER, early compartments of the Golgi stack and pre-Golgi intermediates, which are also referred to as ERGIC [118, 161]. Nuoffer et al. [162] analyzed the phenotype of rab1A mutant in which the S25N substitution reduced the affinity for GTP and resulted in a GDP-bound form. It turned out that the mutation of Rab1A inhibited protein export from the ER, transport between Golgi compartments, and also led to apparent dispersal of the Golgi to the ER, i.e., an ER exit defect was mimicked. Similarly, a Rab GAP expression screen revealed that TBC1D20 was a GAP for Rab1 in vivo and in vitro, and Rab1 was required for Golgi morphological integrity [128]. These results demonstrate that Rab1 not only plays a key role in ER-to-Golgi and intra-Golgi transport, but also is essential for the maintenance of the Golgi structure. Again as with Rab6, the role of Rab1 in Golgi organization may be an indirect consequence of its role in ER-to-Golgi membrane trafficking.

The two members of the Rab2 subfamily, Rab2A and Rab2B, share 82 % identity. In contrast to Rab1, Rab2 has been detected only in pre-Golgi intermediates [163]. To identify the role of Rab2 in membrane trafficking, Tisdale et al. [164] generated site-directed Rab2 mutants. These mutations inhibited protein transport from the ER to the Golgi and indicate that Rab2 is required for ER-to-Golgi trafficking. Furthermore, they demonstrated the function of NH2 terminus (amino acids 1–14) of Rab2. In vitro, this peptide can especially interfere with Rab2 and inhibit ER-to-Golgi transport. NRK cells treated with this peptide exhibit reduced transport of VSV-G protein from the ER to pre-Golgi intermediates and a reduction of the size and abundance of pre-Golgi intermediates. In sum, the amino terminus of Rab2 appears essential for interaction with components involved in the maturation of pre-Golgi intermediates [163]. These outcomes could also reflect that Rab2 works in protein transport from ER to pre-Golgi intermediates. However, unlike Rab1, there is no evidence that Rab2 is associated with vesicle derivation from the ER. In Rab2 amino-terminal peptide experiments, Tisdale et al. [163] did not find any change in Golgi structure using immunofluorescence specific for cis/media resident protein 1,2-mannosidase II as marker. On the other hand, overexpression of the Rab2 GAP, TBC1D20, causes redistribution of Golgi enzymes to the ER [128]. Thus, Rab2 is probably involved both in ER-to-Golgi transport and the regulation of Golgi organization as well.

Rab18 and Rab43 are required for normal Golgi ribbon organization and probably ER/Golgi trafficking

Rab43 has been reported to have a role in the regulation of retrograde transport and Golgi organization. Overexpression of RN-tre, which is the GAP for Rab43, leads to the inhibition of Shiga toxin trafficking from cell surface to trans-Golgi and Golgi ribbon fragmentation, but anterograde transport through the Golgi apparatus is normal. Furthermore, cells depleted of Rab43 or expressing Rab43-T32N display a similar phenotype. The block of Shiga toxin trafficking is proposed to be induced by Golgi disorganization, but further studies are needed [129, 165].

Information about the localization and function of Rab18 is limited. Some reports place Rab18 in endosomes and lipid droplets while others localize it to the ER and Golgi apparatus [104–108]. Like Rab43, Rab18 is essential for ER/Golgi trafficking and Golgi organization. Knockdown of Rab18 using three different siRNA causes inhibition of transport of the model cargo, VSV-G protein, to the cell surface and visible Golgi fragmentation. Overexpression of GFP-Rab18 results in a similar phenotype. Furthermore, the COPI-dependent cargo transport from Golgi to ER is not influenced by overexpression of Rab18-S22N, the GDP-restricted mutant of the protein, while COPI-independent cargo retrograde transport is enhanced. Thus, Rab18 is probably involved in the COPI-independent pathway as well [103, 135].

Defects in Ypt1, Ypt32, and Ypt6 produce Golgi-associated vesicle accumulation in the yeast S. cerevisiae

Ypt6, associated with the Golgi apparatus, is the homologue of mammalian Rab6 in yeast S. cerevisiae (Table 2). Yeast has only one form of Ypt6. It is unknown to which part of Golgi apparatus Ypt6 localizes. Ypt6 is not required for yeast cell viability, but ypt6 deletion or truncation mutants exhibit growth inhibition at elevated temperatures. Moreover, disruption of Ypt6 leads to missorting of carboxypeptidase Y (CPY), inhibition of α-factor precursor processing, and vacuole fragmentation. Deletion of ric1, which implicated in localization of TGN membrane proteins in S. cerevisiae, results in a similar phenotype. SYS1, a multicopy suppressor of defects exhibited in yeast lacking Ypt6, can also complement the phenotype of the ric1 mutant. Therefore, it can be concluded that Ypt6 acts in the same pathway as Ric1 and is associated with Golgi organization [166–168].

Table 2.

Comparison of Rab6 in mammalian cells and Ypt6 in yeast S. cerevisiae

| Rab/Ypt | Isoform | Localization | Transport step | Homologous effector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rab6 | Rab6A, Rab6A′, Rab6B, Rab6Ca | Golgi | Endosome-to-Golgi, Golgi-to-ERb, intra Golgi | TMF/ARA160 |

| Ypt6 | Ypt6 | Golgi | Endosome-to-Golgi, intra Golgi | Sgm1 |

aRab6C predominantly localizes to centrosomes and is associated with regulation of cell cycle progression

bUnlike Rab6A and Rab6A′, Rab6B is only associated with Golgi-to-ER trafficking

Siniossoglou [169] purified proteins that interacted with Ypt6 from yeast cytosol and identified two Ypt6 effectors, the tetrameric VFT complex and Sgm1. Sgm1 is homologous to mammalian Rab6 effector, TMF/ARA160, which is able to bind to three of the isoforms of Rab6, Rab6A, Rab6A′, and Rab6B. Ypt6 has been implicated in intra-Golgi retrograde transport [166]. With loss-of-function mutations of Ypt6, the v-SNARE Sec22p, which cycles between Golgi compartments as well as between Golgi and ER, was mis-sorted to the late Golgi, while in wild-type cells, little of this protein was so localized. In mammalian cells, Rab6 functions in both non-coated and coated vesicle trafficking [135, 142, 149]. Disruption of ypt6 gene causes accumulation of 40 to 50-nm vesicles and membrane-bound, spherical structures. A fraction of these transport vesicles probably are from endosomes and targeted to fuse with late Golgi membranes [167, 170]. Whether these vesicles are coated remains an open question. The mechanism of vesicle formation is unknown.

For Ypt1 and Ypt32, it has been suggested that they have a functional relationship [11]. Ypt1, localized to the cis-Golgi, is thought to be the yeast counterpart of Rab1 in mammalian cells. Overexpression of mouse Rab1A can rescue the abnormal phenotype of yeast caused by mutation of Ypt1 [171–174]. Moreover, as with Rab1, Ypt1 is also required for ER-to-Golgi trafficking and intra-Golgi retrograde transport in yeast [175, 176]. Ypt32 is the homologue of mammalian Rab11 in yeast and mainly localized to the trans-Golgi. It is involved in the regulation of vesicles export from late-Golgi compartments and exhibits functional redundancy with Ypt31 [177].

Ypt1 and Ypt32 appear to act in a single Rab cascade to direct membrane trafficking in the Golgi, i.e., Ypt1 recruits TRAPP complex as GEF for the downstream Rab protein, Ypt32. Then activated Ypt32 recruits Sec2, a GEF for the next Rab protein, Sec4. Ypt32 also recruits Gyp1, which is a GAP for Ypt1 and extracts Ypt1 from the membrane [178–181]. Thus, according to the cisternal maturation model, Ypt1 and Ypt32 are probably associated with the maturation states of the Golgi cisternae. The major organelle structural effect of Rab protein mutations in yeast manifests itself as vesicle accumulation.

Conclusions and perspectives

In this review, we have mainly paid attention to the localization and role of mammalian Rab6, Rab33B, Rab1, Rab2, Rab43, Rab18, and the comparable yeast proteins, Ypt1, Ypt32, and Ypt6. Each Rab protein significantly affects/regulates vesicular trafficking to/through the Golgi apparatus. Much of the affects of these proteins on Golgi organization can be explained on the basis of their effect on vesicular trafficking. Whether effects on Golgi stack interlinking into a Golgi ribbon in mammalian cells is due to the same process is uncertain. Stack interlinking likely requires separate, non-trafficking effectors; the recruitment of structural proteins such as golgins/GRASPs may be important [77, 80, 182, 183]. In mammalian cells, recent evidence points to Rab6 as being a significant regulator of Golgi cisternal number, perhaps by inhibiting COPI-coated vesicle trafficking. Whether other Rab proteins in mammalian cells regulate cisternal number as well as vesicle trafficking accumulation remains an open question. Although a large number of effectors have been identified for many of these Rab proteins, how mechanistically effectors and Rab proteins are linked to produce specific and selective variations in Golgi trafficking/organization is still not clear. This will be a challenge for future work.

Acknowledgments

Work in the Storrie laboratory has been supported by a series of grants from the United States National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Institutes of Health (NIH). Current support is from NIH grant 1R01 GM092206 with equipment support for electron microscopy from NSF grant DBI-0959745.

References

- 1.Farquhar MG, Palade GE. The Golgi apparatus: 100 years of progress and controversy. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:2–10. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01187-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emr S, Glick BS, Linstedt AD, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Luini A, Malhotra V, Marsh BJ, Nakano A, Pfeffer SR, Rabouille C, et al. Journeys through the Golgi-taking stock in a new era. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:449–453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson C, Venditti R, Rega LR, Colanzi A, D’Angelo G, De Matteis MA. The Golgi apparatus: an organelle with multiple complex functions. Biochem J. 2011;433(1):1–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamaki H, Yamashina S. The stack of the Golgi apparatus. Arch Histol Cytol. 2002;65(3):209–218. doi: 10.1679/aohc.65.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowe M. Structure organization of the Golgi apparatus. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shorter J, Warren G. Golgi architecture and inheritance. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 2002;18:379–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.030602.133733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marra P, Salvatore L, Mironov A, Jr, Di Campli A, Di Tullio G, Trucco A, Beznoussenko G, Mironov A, De Matteis MA. The biogenesis of the Golgi ribbon: the roles of membrane input from the ER and of GM130. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1595–1608. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drickamer K, Taylor ME. Evolving views of protein glycosylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:321–324. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Füllekrug J, Nilsson T. Protein sorting in the Golgi complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404(1–2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(98)00048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preuss D, Mulholland J, Franzusoff A, Segev N, Botstein D. Characterization of the Saccharomyces Golgi complex through the cell cycle by immunoelectron microscopy. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3(7):789–803. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.7.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suda Y, Nakano A (2011) The yeast Golgi apparatus. Traffic. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01316.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Dupree P, Sherrier DJ. The plant Golgi apparatus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404(1–2):259–270. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(98)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickel W, Wieland FT. Biosynthetic protein transport through the early secretory pathway. Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;109(5–6):477–486. doi: 10.1007/s004180050249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aridor M, Bannykh SI, Rowe T, Balch WE. Sequential coupling between COPII and COPI vesicle coats in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. J Cell Biol. 1995;131(4):875–893. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weidman PJ. Anterograde transport through the Golgi complex: do Golgi tubules hold the key? Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5(8):302–305. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)89046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorente-Rodríguez A, Barlowe C. Requirement for Golgi-localized PI(4)P in fusion of COPII vesicles with Golgi compartments. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(2):216–229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miesenböck G, Rothman JE. The capacity to retrieve escaped ER proteins extends to the trans-most cisterna of the Golgi stack. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:309–319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganley IG, Espinosa E, Pfeffer SR. A syntaxin 10-SNARE complex distinguishes two distinct transport routes from endosomes to the trans-Golgi in human cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180(1):159–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee MC, Miller EA, Goldberg J, Orci L, Schekman R. Bi-directional protein transport between the ER and Golgi. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:87–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.105307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarragó-Trani MT, Storrie B. Alternate routes for drug delivery to the cell interior: pathways to the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59(8):782–797. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cosson P, Amherdt M, Rothman JE, Orci L. A resident Golgi protein is excluded from peri-Golgi vesicles in NRK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(20):12831–12834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192460999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Storrie B. Maintenance of Golgi apparatus structure in the face of continuous protein recycling to the endoplasmic reticulum: making ends meet. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;244:69–94. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)44002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glick BS. Organization of the Golgi apparatus. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12(4):450–456. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutagalung AH, Novick PJ. Role of Rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(1):119–149. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00059.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goud B, Gleeson PA. TGN golgins, Rabs and cytoskeleton: regulating the Golgi trafficking highways. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(6):329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barr FA. Rab GTPase function in Golgi trafficking. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20(7):780–783. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordens I, Marsman M, Kuijl C, Neefjes J. Rab proteins, connecting transport and vesicle fusion. Traffic. 2005;6(12):1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(8):513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bock JB, Matern HT, Peden AA, Scheller RH. A genomic perspective on membrane compartment organization. Nature. 2001;409(6822):839–841. doi: 10.1038/35057024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bucci C, Parton RG, Mather IH, Stunnenberg H, Simons K, Hoflack B, Zerial M. The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell. 1992;70(5):715–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90306-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBride HM, Rybin V, Murphy C, Giner A, Teasdale R, Zerial M. Oligomeric complexes link Rab5 effectors with NSF and drive membrane fusion via interactions between EEA1 and syntaxin 13. Cell. 1999;98(3):377–386. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo W, Roth D, Walch-Solimena C, Novick P. The exocyst is an effector for Sec4p, targeting secretory vesicles to sites of exocytosis. EMBO J. 1999;18(4):1071–1080. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dumas JJ, Zhu Z, Connolly JL, Lambright DG. Structural basis of activation and GTP hydrolysis in Rab proteins. Structure. 1999;7(4):413–423. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfeffer SR. Structural clues to Rab GTPase functional diversity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(16):15485–15488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee M, Mishra A, Lambright D. Structural mechanisms for regulation of membrane traffic by Rab GTPases. Traffic. 2009;10:1377–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aivazian D, Serrano R, Pfeffer S. TIP47 is a key effector for Rab9 localization. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:917–926. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali B, Seabra M. Targeting of Rab GTPases to cellular membranes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:652–656. doi: 10.1042/BST0330652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chavrier P, Gorvel JP, Stelzer E, Simons K, Gruenberg J, Zerial M. Hypervariable C-terminal domain of rab proteins acts as a targeting signal. Nature. 1991;353:769–772. doi: 10.1038/353769a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pereira-Leal J, Seabra M. The mammalian Rab family of small GTPases: definition of family and subfamily sequence motifs suggests a mechanism for functional specificity in the Ras superfamily. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1077–1087. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore I, Schell J, Palme K. Subclass-specific sequence motifs identified in Rab GTPases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:10–12. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)88939-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostermeier C, Brunger AT. Structural basis of Rab effector specificity: crystal structure of the small G protein Rab3A complexed with the effector domain of rabphilin-3A. Cell. 1999;96:363–374. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlichting I, Almo SC, Rapp G, Wilson K, Petratos K, Lentfer A, Wittinghofer A, Kabsch W, Pai EF, Petsko GA, Goody RS. Time-resolved X-ray crystallographic study of the conformational change in Ha-Ras p21 protein on GTP hydrolysis. Nature. 1990;345:309–315. doi: 10.1038/345309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stroupe C, Brunger AT. Crystal structures of a Rab protein in its inactive and active conformations. J Mol Biol. 2000;304(4):585–598. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brennwald P, Novick P. Interactions of three domains distinguishing the Ras-related GTP-binding proteins Ypt1 and Sec4. Nature. 1993;362:560–563. doi: 10.1038/362560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfeffer SR. Rab GTPases: specifying and deciphering organelle identity and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11(12):487–491. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02147-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alexandrov K, Horiuchi H, Steele-Mortimer O, Seabra M, Zerial M. Rab escort protein-1 is a multifunctional protein that accompanies newly prenylated rab proteins to their target membranes. EMBO J. 1994;13:5262–5273. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andres D, Seabra M, Brown M, Armstrong S, Smeland T, Cremers F, Goldstein J. cDNA cloning of component A of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase and demonstration of its role as a Rab escort protein. Cell. 1993;73:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ullrich O, Stenmark H, Alexandrov K, Huber LA, Kaibuchi K, Sasaki T, Takai Y, Zerial M. Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor as a general regulator for the membrane association of rab proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18143–18150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dirac-Svejstrup AB, Sumizawa T, Pfeffer SR. Identification of a GDI displacement factor that releases endosomal Rab GTPases from Rab-GDI. EMBO J. 1997;16:465–472. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins R. “Getting it on”-GDI displacement and small GTPase membrane recruitment. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1064–1066. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bos J, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alory C, Balch WE. Organization of the Rab-GDI/CHM superfamily: the functional basis for choroideremia disease. Traffic. 2001;2(8):532–543. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.20803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garrett MD, Zahner JE, Cheney CM, Novick PJ. GDI1 encodes a GDP dissociation inhibitor that plays an essential role in the yeast secretory pathway. EMBO J. 1994;13(7):1718–1728. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grosshans BL, Ortiz D, Novick P. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(32):11821–11827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kishida S, Shirataki H, Sasaki T, Kato M, Kaibuchi K, Takai Y. Rab3A GTPase-activating protein-inhibiting activity of Rabphilin-3A, a putative Rab3A target protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(30):22259–22261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X, Hu B, Zimmermann B, Kilimann MW. Rim1 and rabphilin-3 bind Rab3-GTP by composite determinants partially related through N-terminal alpha -helix motifs. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(35):32480–32488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Handley MT, Burgoyne RD. The Rab27 effector Rabphilin, unlike Granuphilin and Noc2, rapidly exchanges between secretory granules and cytosol in PC12 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373(2):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fukuda M. Versatile role of Rab27 in membrane trafficking: focus on the Rab27 effector families. J Biochem. 2005;137(1):9–16. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Díaz E, Pfeffer SR. TIP47: a cargo selection device for mannose 6-phosphate receptor trafficking. Cell. 1998;93(3):433–443. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bahadoran P, Aberdam E, Mantoux F, Buscà R, Bille K, Yalman N, de Saint-Basile G, Casaroli-Marano R, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R. Rab27a: a key to melanosome transport in human melanocytes. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(4):843–850. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hume AN, Collinson LM, Rapak A, Gomes AQ, Hopkins CR, Seabra MC. Rab27a regulates the peripheral distribution of melanosomes in melanocytes. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(4):795–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strom M, Hume AN, Tarafder AK, Barkagianni E, Seabra MC. A family of Rab27-binding proteins. Melanophilin links Rab27a and myosin Va function in melanosome transport. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(28):25423–25430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matanis T, Akhmanova A, Wulf P, Del Nery E, Weide T, Stepanova T, Galjart N, Grosveld F, Goud B, De Zeeuw CI, Barnekow A, Hoogenraad CC. Bicaudal-D regulates COPI-independent Golgi-ER transport by recruiting the dynein-dynactin motor complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(12):986–992. doi: 10.1038/ncb891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moyer BD, Allan BB, Balch WE. Rab1 interaction with a GM130 effector complex regulates COPII vesicle cis—Golgi tethering. Traffic. 2001;2(4):268–276. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.1o007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.TerBush DR, Maurice T, Roth D, Novick P. The exocyst is a multiprotein complex required for exocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . EMBO J. 1996;15(23):6483–6494. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lehman K, Rossi G, Adamo JE, Brennwald P. Yeast homologues of tomosyn and lethal giant larvae function in exocytosis and are associated with the plasma membrane SNARE, Sec9. J Cell Biol. 1999;146(1):125–140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grosshans BL, Andreeva A, Gangar A, Niessen S, Yates JR, 3rd, Brennwald P, Novick P. The yeast lgl family member Sro7p is an effector of the secretory Rab GTPase Sec4p. J Cell Biol. 2006;172(1):55–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weide T, Teuber J, Bayer M, Barnekow A. MICAL-1 isoforms, novel rab1 interacting proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fischer J, Weide T, Barnekow A. The MICAL proteins and rab1: a possible link to the cytoskeleton? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328(2):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ooms LM, Horan KA, Rahman P, Seaton G, Gurung R, Kethesparan DS, Mitchell CA. The role of the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases in cellular function and human disease. Biochem J. 2009;419(1):29–49. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hyvola N, Diao A, McKenzie E, Skippen A, Cockcroft S, Lowe M. Membrane targeting and activation of the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL1 by rab GTPases. EMBO J. 2006;25(16):3750–3761. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laufman O, Hong W, Lev S. The COG complex interacts directly with Syntaxin 6 and positively regulates endosome-to-TGN retrograde transport. J Cell Biol. 2011;194(3):459–472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alvarez C, Garcia-Mata R, Hauri HP, Sztul E. The p115-interactive proteins GM130 and giantin participate in endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi traffic. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(4):2693–2700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weide T, Bayer M, Köster M, Siebrasse JP, Peters R, Barnekow A. The Golgi matrix protein GM130: a specific interacting partner of the small GTPase rab1b. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(4):336–341. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Diao A, Rahman D, Pappin DJC, Lucocq J, Lowe M. The coiled-coil membrane protein golgin-84 is a novel rab effector required for Golgi ribbon formation. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:201–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Satoh A, Wang Y, Malsam J, Beard MB, Warren G. Golgin-84 is a rab1 binding partner involved in Golgi structure. Traffic. 2003;4(3):153–161. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fukuda M, Kanno E, Ishibashi K, Itoh T. Large scale screening for novel rab effectors reveals unexpected broad Rab binding specificity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(6):1031–1042. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700569-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duran JM, Kinseth M, Bossard C, Rose DW, Polishchuk R, Wu CC, Yates J, Zimmerman T, Malhotra V. The role of GRASP55 in Golgi fragmentation and entry of cells into mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(6):2579–2587. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-0998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Short B, Preisinger C, Körner R, Kopajtich R, Byron O, Barr FA. A GRASP55-rab2 effector complex linking Golgi structure to membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 2001;155(6):877–883. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fernandes H, Franklin E, Recacha R, Houdusse A, Goud B, Khan AR. Structural aspects of Rab6-effector complexes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(5):1037–1041. doi: 10.1042/BST0371037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Antony C, Cibert C, Géraud G, Santa Maria A, Maro B, Mayau V, Goud B. The small GTP-binding protein rab6p is distributed from medial Golgi to the trans-Golgi network as determined by a confocal microscopic approach. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:785–796. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Opdam FJ, Echard A, Croes HJ, van den Hurk JA, van de Vorstenbosch RA, Ginsel LA, Goud B, Fransen JA. The small GTPase Rab6B, a novel Rab6 subfamily member, is cell-type specifically expressed and localised to the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2725–2735. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.15.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Young J, Ménétrey J, Goud B. RAB6C is a retrogene that encodes a centrosomal protein involved in cell cycle progression. J Mol Biol. 2010;397(1):69–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schlager MA, Kapitein LC, Grigoriev I, Burzynski GM, Wulf PS, Keijzer N, de Graaff E, Fukuda M, Shepherd IT, Akhmanova A, Hoogenraad CC. Pericentrosomal targeting of Rab6 secretory vesicles by Bicaudal-D-related protein 1 (BICDR-1) regulates neuritogenesis. EMBO J. 2010;29(10):1637–1651. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barbero P, Bittova L, Pfeffer SR. Visualization of Rab9-mediated vesicle transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(3):511–518. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Díaz E, Schimmöller F, Pfeffer SR. A novel Rab9 effector required for endosome-to-TGN transport. J Cell Biol. 1997;138(2):283–290. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reddy JV, Burguete AS, Sridevi K, Ganley IG, Nottingham RM, Pfeffer SR. A functional role for the GCC185 golgin in mannose 6-phosphate receptor recycling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(10):4353–4363. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schuck S, Gerl MJ, Ang A, Manninen A, Keller P, Mellman I, Simons K. Rab10 is involved in basolateral transport in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Traffic. 2007;8(1):47–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ullrich O, Reinsch S, Urbé S, Zerial M, Parton RG. Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J Cell Biol. 1996;135(4):913–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lindsay AJ, McCaffrey MW. Rab11-FIP2 functions in transferrin recycling and associates with endosomal membranes via its COOH-terminal domain. J Cell Chem. 2002;277(30):27193–27199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schonteich E, Wilson GM, Burden J, Hopkins CR, Anderson K, Goldenring JR, Prekeris R. The Rip11/Rab11-FIP5 and kinesin II complex regulates endocytic protein recycling. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(22):3824–3833. doi: 10.1242/jcs.032441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mammoto A, Ohtsuka T, Hotta I, Sasaki T, Takai Y. Rab11BP/Rabphilin-11, a downstream target of rab11 small G protein implicated in vesicle recycling. J Cell Chem. 1999;274(36):25517–25524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lindsay AJ, Marie N, McCaffrey MW. Functional properties of the Rab-binding domain of Rab coupling protein. Methods Enzymol. 2005;403:481–491. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)03042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Olkkonen VM, Dupree P, Killisch I, Lütcke A, Zerial M, Simons K. Molecular cloning and subcellular localization of three GTP-binding proteins of the rab subfamily. J Cell Sci. 1993;106(4):1249–1261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Iida H, Wang L, Nishii K, Ookuma A, Shibata Y. Identification of rab12 as a secretory granule-associated small GTP-binding protein in atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;78(2):343–347. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.78.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nokes RL, Fields IC, Collins RN, Fölsch H. Rab13 regulates membrane trafficking between TGN and recycling endosomes in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;182(5):845–853. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zahraoui A, Joberty G, Arpin M, Fontaine JJ, Hellio R, Tavitian A, Louvard D. A small rab GTPase is distributed in cytoplasmic vesicles in non polarized cells but colocalizes with the tight junction marker ZO-1 in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;124(1–2):101–115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Junutula JR, De Maziére AM, Peden AA, Ervin KE, Advani RJ, van Dijk SM, Klumperman J, Scheller RH. Rab14 is involved in membrane trafficking between the Golgi complex and endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(5):2218–2229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Proikas-Cezanne T, Gaugel A, Frickey T, Nordheim A. Rab14 is part of the early endosomal clathrin-coated TGN microdomain. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(22):5241–5246. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kelly EE, Horgan CP, Adams C, Patzer TM, Ní Shúilleabháin DM, Norman JC, McCaffrey MW. Class I Rab11-family interacting proteins are binding targets for the Rab14 GTPase. Biol Cell. 2009;102(1):51–62. doi: 10.1042/BC20090068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yamamoto H, Koga H, Katoh Y, Takahashi S, Nakayama K, Shin HW. Functional cross-talk between Rab14 and Rab4 through a dual effector, RUFY1/Rabip4. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(15):2746–2755. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dejgaard SY, Murshid A, Erman A, Kizilay O, Verbich D, Lodge R, Dejgaard K, Ly-Hartig TB, Pepperkok R, Simpson JC, Presley JF. Rab18 and Rab43 have key roles in ER-Golgi trafficking. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2768–2781. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lütcke A, Parton RG, Murphy C, Olkkonen VM, Dupree P, Valencia A, Simons K, Zerial M. Cloning and subcellular localization of novel rab proteins reveals polarized and cell type-specific expression. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:3437–3448. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brasaemle DL, Dolios G, Shapiro L, Wang R. Proteomic analysis of proteins associated with lipid droplets of basal and lipolytically stimulated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(45):46835–46842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ozeki S, Cheng J, Tauchi-Sato K, Hatano N, Taniguchi H, Fujimoto T. Rab18 localizes to lipid droplets and induces their close apposition to the endoplasmic reticulum-derived membrane. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2601–2611. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Martin S, Driessen K, Nixon SJ, Zerial M, Parton RG. Regulated localization of Rab18 to lipid droplets: effects of lipolytic stimulation and inhibition of lipid droplet catabolism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(51):42325–42335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gilchrist A, Au CE, Hiding J, Bell AW, Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Lesimple S, Nagaya H, Roy L, Gosline SJ, Hallett M, Paiement J, Kearney RE, Nilsson T, Bergeron JJ. Quantitative proteomics analysis of the secretory pathway. Cell. 2006;127(6):1265–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lütcke A, Olkkonen VM, Dupree P, Lütcke H, Simons K, Zerial M. Isolation of a murine cDNA clone encoding Rab19, a novel tissue-specific small GTPase. Gene. 1995;155(2):257–260. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00931-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Amillet JM, Ferbus D, Real FX, Antony C, Muleris M, Gress TM, Goubin G. Characterization of human Rab20 overexpressed in exocrine pancreatic carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(3):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen D, Guo J, Miki T, Tachibana M, Gahl WA. Molecular cloning of two novel rab genes from human melanocytes. Gene. 1996;174(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.de Leeuw HP, Wijers-Koster PM, van Mourik JA, Voorberg J. Small GTP-binding protein RalA associates with Weibel-Palade bodies in endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82(3):1177–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kelly EE, Giordano F, Horgan CP, Jollivet F, Raposo G, McCaffrey MW (2011) Rab30 is required for the morphological integrity of the Golgi apparatus. Biol Cell. doi:10.1111/boc.201100080 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 114.Fukuda M, Itoh T. Direct link between Atg protein and small GTPase Rab: Atg16L functions as a potential Rab33 effector in mammals. Autophagy. 2008;4(6):824–826. doi: 10.4161/auto.6542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mallard F, Tang BL, Galli T, Tenza D, Saint-Pol A, Yue X, Antony C, Hong W, Goud B, Johannes L. Early/recycling endosomes-to-TGN transport involves two SNARE complexes and a Rab6 isoform. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(4):653–664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Valsdottir R, Hashimoto H, Ashman K, Koda T, Storrie B, Nilsson T. Identification of rabaptin-5, rabex-5, and GM130 as putative effectors of rab33b, a regulator of retrograde traffic between the Golgi apparatus and ER. FEBS Lett. 2001;508(2):201–209. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02993-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Starr T, Sun Y, Wilkins N, Storrie B. Rab33b and Rab6 are functionally overlapping regulators of Golgi homeostasis and trafficking. Traffic. 2010;11(5):626–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Plutner H, Cox AD, Pind S, Khosravi-Far R, Bourne JR, Schwaninger R, Der CJ, Balch WE. Rab1b regulates vesicular transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and successive Golgi compartments. J Cell Biol. 1991;115(1):31–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Goldenberg NM, Grinstein S, Silverman M. Golgi-bound Rab34 is a novel member of the secretory pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(12):4762–4771. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-0991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Song Y, Ailenberg M, Silverman M. Cloning of a novel gene in the human kidney homologous to rat munc13s: its potential role in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998;53(6):1689–1695. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Colucci AM, Campana MC, Bellopede M, Bucci C. The Rab-interacting lysosomal protein, a Rab7 and Rab34 effector, is capable of self-interaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334(1):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mori T, Fukuda Y, Kuroda H, Matsumura T, Ota S, Sugimoto T, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J. Cloning and characterization of a novel Rab-family gene, Rab36, within the region at 22q11.2 that is homozygously deleted in malignant rhabdoid tumors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254(3):594–600. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chen L, Hu J, Yun Y, Wang T. Rab36 regulates the spatial distribution of late endosomes and lysosomes through a similar mechanism to Rab34. Mol Membr Biol. 2010;27(1):24–31. doi: 10.3109/09687680903417470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chen T, Han Y, Yang M, Zhang W, Li N, Wan T, Guo J, Cao X. Rab39, a novel Golgi-associated Rab GTPase from human dendritic cells involved in cellular endocytosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303(4):1114–1120. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Becker CE, Creagh EM, O’Neill LA. Rab39a binds caspase-1 and is required for caspase-1-dependent interleukin-1beta secretion. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(50):34531–34537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lee RH, Iioka H, Ohashi M, Iemura S, Natsume T, Kinoshita N. XRab40 and XCullin5 form a ubiquitin ligase complex essential for the noncanonical Wnt pathway. EMBO J. 2007;26(15):3592–3606. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kanno E, Ishibashi K, Kobayashi H, Matsui T, Ohbayashi N, Fukuda M. Comprehensive screening for novel rab-binding proteins by GST pull-down assay using 60 different mammalian Rabs. Traffic. 2010;11(4):491–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Haas AK, Yoshimura S, Stephens DJ, Preisinger C, Fuchs E, Barr FA. Analysis of GTPase-activating proteins: Rab1 and Rab43 are key Rabs required to maintain a functional Golgi complex in human cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2997–3010. doi: 10.1242/jcs.014225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bard F, Casano L, Mallabiabarrena A, Wallace E, Saito K, Kitayama H, Guizzunti G, Hu Y, Wendler F, Dasgupta R, Perrimon N, Malhotra V. Functional genomics reveals genes involved in protein secretion and Golgi organization. Nature. 2006;439(7076):604–607. doi: 10.1038/nature04377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Echard A, Opdam FJ, de Leeuw HJ, Jollivet F, Savelkoul P, Hendriks W, Voorberg J, Goud B, Fransen JA. Alternative splicing of the human Rab6A gene generates two close but functionally different isoforms. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(11):3819–3833. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Goud B, Zahraoui A, Tavitian A, Saraste J. Small GTP-binding protein associated with Golgi cisternae. Nature. 1990;345(6275):553–556. doi: 10.1038/345553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Martinez O, Schmidt A, Salaméro J, Hoflack B, Roa M, Goud B. The small GTP-binding protein rab6 functions in intra-Golgi transport. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1575–1588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Martinez O, Antony C, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Berger EG, Salamero J, Goud B. GTP-bound forms of rab6 induce the redistribution of Golgi proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(5):1828–1833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.White J, Johannes L, Mallard F, Girod A, Grill S, Reinsch S, Keller P, Tzschaschel B, Echard A, Goud B, Stelzer EH. Rab6 coordinates a novel Golgi to ER retrograde transport pathway in live cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;147(4):743–760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Girod A, Storrie B, Simpson JC, Johannes L, Goud B, Roberts LM, Lord JM, Nilsson T, Pepperkok R. Evidence for a COP-I-independent transport route from the Golgi complex to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(7):423–430. doi: 10.1038/15658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kano F, Yamauchi S, Yoshida Y, Watanabe-Takahashi M, Nishikawa K, Nakamura N, Murata M. Yip1A regulates the COPI-independent retrograde transport from the Golgi complex to the ER. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2218–2227. doi: 10.1242/jcs.043414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sannerud R, Saraste J, Goud B. Retrograde traffic in the biosynthetic-secretory route: pathways and machinery. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15(4):438–445. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Del Nery E, Miserey-Lenkei S, Falguières T, Nizak C, Johannes L, Perez F, Goud B. Rab6A and Rab6A′ GTPases play non-overlapping roles in membrane trafficking. Traffic. 2006;7(4):394–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Monier S, Jollivet F, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Johannes L, Goud B. Characterization of novel Rab6-interacting proteins involved in endosome-to-TGN transport. Traffic. 2002;3(4):289–297. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Utskarpen A, Slagsvold HH, Iversen TG, Wälchli S, Sandvig K. Transport of ricin from endosomes to the Golgi apparatus is regulated by Rab6A and Rab6A′. Traffic. 2006;7(6):663–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Young J, Stauber T, del Nery E, Vernos I, Pepperkok R, Nilsson T. Regulation of microtubule-dependent recycling at the trans-Golgi network by Rab6A and Rab6A′. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(1):162–177. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Miserey-Lenkei S, Chalancon G, Bardin S, Formstecher E, Goud B, Echard A. Rab and actomyosin-dependent fission of transport vesicles at the Golgi complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(7):645–654. doi: 10.1038/ncb2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Valente C, Polishchuk R, De Matteis MA. Rab6 and myosin II at the cutting edge of membrane fission. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(7):635–638. doi: 10.1038/ncb0710-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.De Matteis MA, Luini A. Exiting the Golgi complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Grigoriev I, Splinter D, Keijzer N, Wulf PS, Demmers J, Ohtsuka T, Modesti M, Maly IV, Grosveld F, Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A. Rab6 regulates transport and targeting of exocytotic carriers. Dev Cell. 2007;13(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Grigoriev I, Yu KL, Martinez-Sanchez E, Serra-Marques A, Smal I, Meijering E, Demmers J, Peränen J, Pasterkamp RJ, van der Sluijs P, Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A. Rab6, Rab8, and MICAL3 cooperate in controlling docking and fusion of exocytotic carriers. Curr Biol. 2011;21(11):967–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Huber LA, Pimplikar S, Parton RG, Virta H, Zerial M, Simons K. Rab8, a small GTPase involved in vesicular traffic between the TGN and the basolateral plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1993;123(1):35–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sun Y, Shestakova A, Hunt L, Sehgal S, Lupashin V, Storrie B. Rab6 regulates both ZW10/RINT-1 and conserved oligomeric Golgi complex-dependent Golgi trafficking and homeostasis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(10):4129–4142. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Storrie B, Micaroni M, Morgan GP, Jones N, Kamykowski JA, Wilkins N, Pan TH, Marsh BJ. Electron tomography reveals that Rab6 is essential to the trafficking of trans-Golgi clathrin and COPI-coated vesicles and the maintenance of Golgi cisternal number. Traffic. 2012;13(5):727–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Karess R. Rod-Zw10-Zwilch: a key player in the spindle checkpoint. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(7):386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]