Abstract

Both swallowing and respiration involve postinspiratory laryngeal adduction. Swallowing-related postinspiratory neurons are likely to be located in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and those involved in respiration are found in the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus (KF). The function of KF and NTS in the generation of swallowing and its coordination with respiration was investigated in perfused brainstem preparations of juvenile rats (n = 41). Orally injected water evoked sequential pharyngeal swallowing (s-PSW) seen as phasic, spindle-shaped bursting of vagal nerve activity (VNA) against tonic postinspiratory discharge. KF inhibition by microinjecting isoguvacine (GABAA receptor agonist) selectively attenuated tonic postinspiratory VNA (n = 10, P < 0.001) but had no effect on frequency or timing of s-PSW. KF disinhibition after bicuculline (GABAA receptor antagonist) microinjections caused an increase of the tonic VNA (n = 8, P < 0.01) resulting in obscured and delayed phasic s-PSW. Occurrence of spontaneous PSW significantly increased after KF inhibition (P < 0.0001) but not after KF disinhibition (P = 0.14). NTS isoguvacine microinjections attenuated the occurrence of all PSW (n = 5, P < 0.01). NTS bicuculline microinjections (n = 6) resulted in spontaneous activation of a disordered PSW pattern and long-lasting suppression of respiratory activity. Pharmacological manipulation of either KF or NTS also triggered profound changes in respiratory postinspiratory VNA. Our results indicate that the s-PSW comprises two functionally distinct components. While the primary s-PSW is generated within the NTS, a KF-mediated laryngeal adductor reflex safeguards the lower airways from aspiration. Synaptic interaction between KF and NTS is required for s-PSW coordination with respiration as well as for proper gating and timing of s-PSW.

Key points

Laryngeal adduction is a major mechanism in sealing off entry to the trachea to prevent aspiration during swallowing.

An experimental protocol to reliably elicit sequential swallowing by oral injection of small volumes of water was developed in the in situ perfused brainstem preparation of juvenile rats.

The sequential swallowing motor pattern consists of two distinct components: (i) phasic swallowing, indicated by rhythmic sequential vagal nerve bursting, and (ii) protective laryngeal adduction, indicated by background tonic vagal discharge.

Pharmacological manipulation of the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus revealed that it specifically mediates the protective tonic laryngeal adduction, while GABAergic neurotransmission is needed in the nucleus of the solitary tract for the generation of the sequential swallowing motor pattern.

We conclude that sequential swallow motor patterning, including effective airway protection, requires balanced excitatory–inhibitory synaptic interaction within the nucleus of the solitary tract and the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus, as well as between the two nuclei.

Introduction

Swallowing disorders that increase the risk of aspiration and subsequent pneumonia are prevalent in the elderly and patients with neurological diseases such as Rett syndrome, Alzheimer's disease and Parkinsonism (Kalia, 2003; Easterling & Robbins, 2008; Lin et al. 2012; Sura et al. 2012; Alagiakrishnan et al. 2013). Swallowing disorders are often attributed to a weakening of the ageing upper airway and digestive tract musculature; however, disturbed neural coordination of breathing and swallowing is evident in such diseases (Shaker et al. 1992; Hadjikoutis et al. 2000; Gross et al. 2008; Aydogdu et al. 2011).

The central pattern generators that control breathing/respiration (r-CPG) and swallowing (sw-CPG) are located in the brainstem. Using the definition proposed by Grillner & Wallén (1985), we define a CPG as the central network required to generate a rhythmic, patterned motor behaviour in the absence of sensory input. The r-CPG is a constantly active network of columnar-organized neurons in the ponto-medullary brainstem (Alheid et al. 2004; Lindsey et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2013). In contrast, the sw-CPG required to produce the oropharyngeal stage of swallow is gated under resting conditions in that it requires sensory or cortical commands to trigger swallowing. The sw-CPG is restricted to the caudal brainstem. The ‘dorsal swallowing group’ is located in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) (Jean & Car, 1979; Kalia & Mesulam, 1980; Kessler & Jean, 1985) and the ‘ventral swallowing group’ comprises the reticular formation dorsomedial to the nucleus ambiguus (Kessler & Jean, 1985; Ezure et al. 1993; Sugiyama et al. 2011). The NTS also contains respiratory-related neurons, termed the dorsal respiratory group, that are adjacent to, and may overlap with, the dorsal swallowing group in cat (Berger, 1977; Lipski & Merrill 1980; see Long & Duffin, 1986). In rat, however, respiratory neurons in the dorsal respiratory group appear to be sparse (Saether et al. 1987; Ezure et al. 1988; see Bianchi et al. 1995).

The laryngeal adductor muscles that narrow the vocal folds are an important final motor output common to both swallowing and respiration (Bolser et al. 2006; Bianchi & Gestreau, 2009; Davenport et al. 2011; Pitts et al. 2013). Partial laryngeal adduction dynamically contributes to patterning of the expiratory airflow during breathing (Harding, 1984; Bartlett, 1986; Dutschmann & Paton, 2002b). Importantly, laryngeal adductors also play a pivotal role in protecting the lower airways (trachea, lungs) from aspiration of ingested materials during swallowing (Medda et al. 2003). The laryngeal adductor motor neurons are located in the nucleus ambiguus (Bieger & Hopkins, 1987) and discharge during the postinspiratory (early expiratory) stage of respiration. The very same motor neurons are recruited during swallowing (Gestreau et al. 2000; Sun et al. 2011).

The mechanisms by which the r-CPG and sw-CPG interact to produce effective protection of the airway, including the origins of swallowing-related laryngeal adduction, are poorly understood. Potential mediators of interaction between the sw-CPG and r-CPG are probably the premotor neurons that drive postinspiration in laryngeal motor neurons (Shiba et al. 1999, 2007). A major population of postinspiratory premotor neurons is located in the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus (KF), which forms part of the pontine respiratory group (Dutschmann & Herbert, 2006; Dutschmann & Dick, 2012). Previous studies suggest a role for the KF in the gating of swallowing and its coordination with respiration (Oku & Dick, 1992; Bonis et al. 2011, 2013). However, the role of the KF in elaborating the swallowing-related postinspiratory laryngeal adductor activity was not addressed. Some evidence also supports the notion that the NTS may directly provide premotor drive to laryngeal adductors during swallowing (Sugiyama et al. 2011; Sun et al. 2011). The NTS subnuclei that form part of the sw-CPG are also densely and reciprocally connected with KF in the dorsolateral pons (Herbert et al. 1990; Song et al. 2011). Therefore, the neural axis between NTS and KF is a logical target for investigation of swallowing/breathing interaction.

Here we used the in situ perfused brainstem preparation of juvenile rat to study the involvement of the KF and NTS in the generation of fictive swallowing. We demonstrate that the in situ preparation reliably generates swallowing sequences following injection of a small amount of water into the oral cavity. Use of this decerebrate experimental model avoids the suppression of laryngeal adductor activity and swallowing under anaesthetized conditions in vivo (Bartlett, 1979; Nishino et al. 1985; Sun et al. 2011). The study tested the hypotheses that: (1) the KF contributes to swallow-related laryngeal adduction, and (2) the NTS is primarily responsible for the patterning of sequential pharyngeal swallowing.

Methods

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes and conform to the principles of UK regulations, as described in Drummond (2009). This study was approved by, and carried out according to the guidelines of, the ethics committee of the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health (AEC 12–084).

Perfused brainstem preparation

Experiments were performed using the arterially perfused, in situ brainstem preparation (Paton, 1996) of juvenile Sprague–Dawley rats of either sex and aged postnatal days 17–21. All basic procedures performed to obtain the perfused brainstem preparations in the present study follow the exact protocol as described in Dutschmann et al. (2009). In brief, rats were anaesthetised deeply in an atmosphere saturated with isoflurane (1-chloro-2,2,2-trifluoroethyl-difluoromethylether). Once the animal failed to respond to noxious pinch to the tail or a hind paw, the whole animal was transected below the diaphragm, and the rostral half was transferred into ice-cold (5°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) gassed with carbogen (95% O2 and 5% CO2), decerebrated at the precollicular level and cerebellectomised. Additionally, the lungs and heart were removed.

Nerve recording

Activity from the cut proximal ends of isolated nerves was recorded using suction electrodes. In all experiments, phrenic nerve activity (PNA) was used to monitor inspiratory respiratory activity. Cervical vagal nerve activity (VNA) served as an index for both inspiratory and postinspiratory respiratory activity. Activity from the lateral hypoglossal nerve (HNA) or iliohypogastric branch of the abdominal nerve (AbNA) was also recorded. Nerve signals were amplified (differential amplifier DP-311, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA), band-pass filtered (100 Hz to 5 kHz), digitized (PowerLab/16SP ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia) and stored on a computer using Chart v7.0/s software (ADInstruments). During post hoc analysis, additional digital filtering in the Chart program (high pass >10 Hz) was applied when necessary to remove movement artifacts.

In each preparation, PNA was used to fine-tune the perfusion in order to obtain a ramping envelope of the integrated PNA with discharge duration of approximately 1 s or shorter. Optimal perfusion also corresponded with the presence of a sharp onset of postinspiratory activity in VNA. Flow rates (18–22 ml min–1) and perfusion pressures (40–70 mmHg) required to obtain consistent respiratory patterning in recorded nerves varied between animals.

Eliciting sequential pharyngeal swallowing (s-PSW) in situ

Oral injection of distilled water was chosen as a stimulus for evoking swallowing in lieu of the widely used electrical stimulation of the superior laryngeal nerve because it (1) is more physiological, akin to drinking fluid, and thus activates both glossopharyngeal and laryngeal sensory nerve afferents, and (2) results in a s-PSW pattern similar to that seen during human drinking (Aydogdu et al. 2011). s-PSW could be reliably triggered in the perfused brainstem preparation by injecting 0.2–0.6 ml of distilled water (room temperature) into the oral cavity via a small plastic tube whose caudal end was placed approximately 0.75 cm rostral to the larynx. At the beginning of every experiment, the volume of injected water and positioning of the injection cannula was optimized. The volume was chosen such that elicited s-PSW sequences consisted of typically 3–6 fast sequential swallowing bursts, followed by a smaller number of swallows at a much lower frequency (see examples in Fig. 1A–E). It is pertinent to distinguish between PSW and gagging. In cases of inappropriately high volumes of injected water, fast speed of injection or misplaced oral cannula, longer VNA bursts (>600 ms) with concurrent abdominal activity (AbNA) that were probably related to gagging or retching motor activity were observed (Figs 1E and 2F). Gagging activities were excluded from analysis.

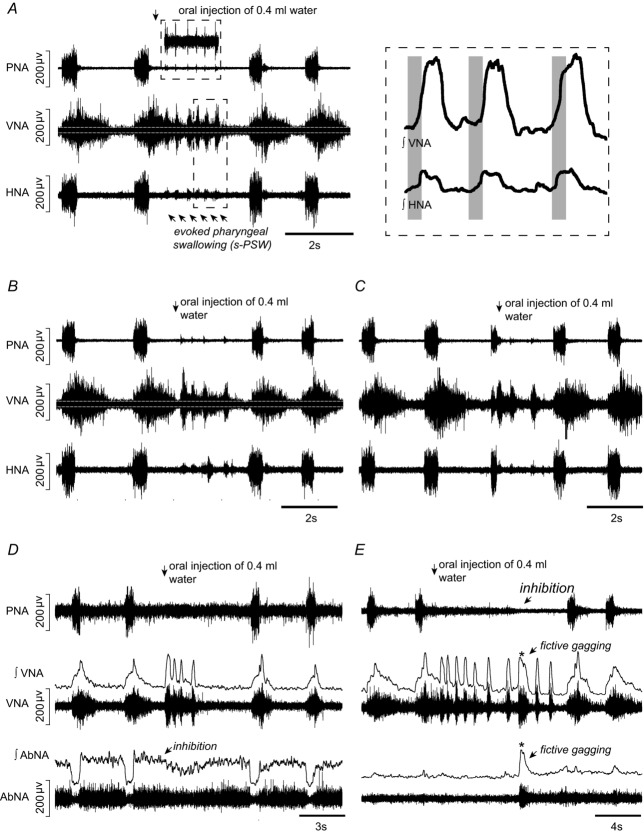

Figure 1. Fictive swallow sequences elicited by water stimulation of the pharynx of the in situ perfused juvenile rat preparation.

A, a typical example of a sequential pharyngeal swallowing (s-PSW) sequence elicited by oral injection of a small volume of distilled water during postinspiration. s-PSW corresponds with short, spindle-shaped bursts in cervical vagal nerve activity (VNA). Each s-PSW-related VNA burst is accompanied by a low amplitude burst in lateral hypoglossal nerve activity (HNA) (lower box; integrated VNA and HNA shown at higher magnification on the right). During the s-PSW sequence, inspiratory discharges in phrenic nerve activity (PNA) are inhibited, although a very low amplitude activity sometimes occurred in time with s-PSW-related VNA bursts (top box). Importantly, tonic lower amplitude activity is observed in VNA prior to and in between phasic swallow bursts. White lines indicate zero activity in VNA. B, prominent tonic s-PSW-related VNA still occurs if water injection is timed in late expiration. Note the medium-sized burst in HNA in the interval between the three fast swallows and the delayed fourth swallow. C, water stimulation timed during inspiration prematurely terminates this phase. Generally, fewer s-PSW bursts are elicited and the tonic activity between swallows is reduced. D, baseline activity from the iliohypogastric branch of abdominal nerve (AbNA) is inhibited during the evoked s-PSW. E, fictive gags (asterisk) are occasionally elicited by water stimulation. Gags are associated with longer bursts in VNA and with concurrent robust bursts in AbNA.

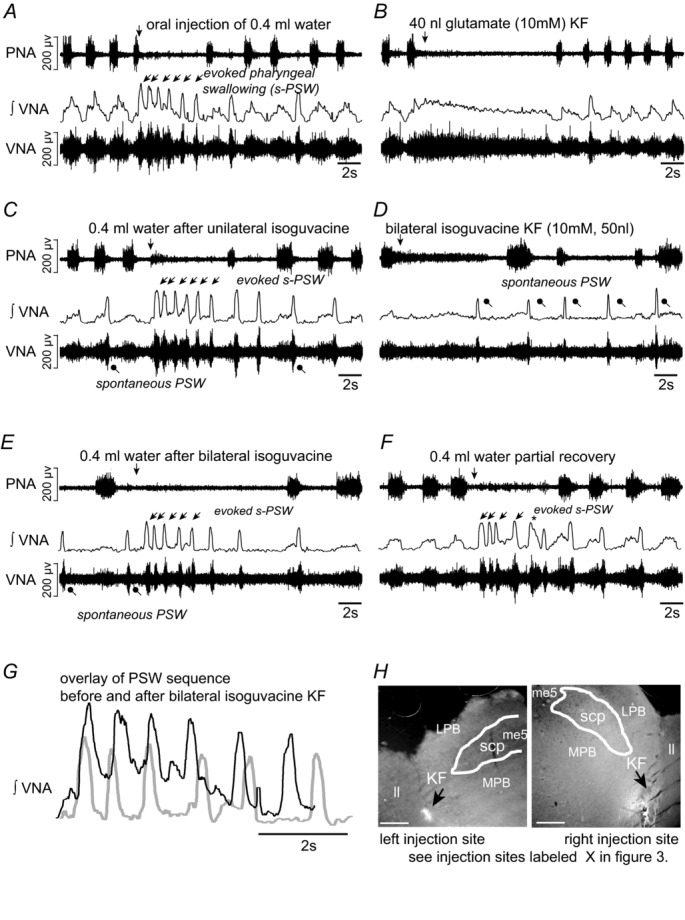

Figure 2. Swallowing activity after inhibition of the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus (KF).

A, evoked sequential pharyngeal swallowing (s-PSW, arrows) during baseline conditions. B, microinjection of glutamate into the intermediate KF region induces a postinspiratory apnoea. C, unilateral injection of GABAA receptor agonist isoguvacine (10 mm, 50 nl) into the left KF results in spontaneous swallows (dots). Tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW is slightly reduced. D, increased incidence of spontaneous swallows immediately after the second microinjection of isoguvacine into the right KF. E, bilateral microinjections of isoguvacine into the KF region causes apneusis. The tonic postinspiratory component of the evoked s-PSW is virtually abolished. F, partial recovery of the tonic s-PSW activity after 45 min. G, integrated VNA showing that the timing and duration of s-PSW remains comparable before (black) and after (grey) bilateral inhibition of KF. The decrease in amplitude of tonic VNA is the only obvious difference. H, microinjection sites marked with rhodamine beads. The KF is shown in relation to the lateral leminscus (ll), lateral parabrachial complex (LPB), medial parabrachial complex (MPB), superior cerebellar peduncle (scp) and mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus (Me5). Scale bar = 500 μm.

After the initial adjustments, a s-PSW sequence without gagging could be elicited repetitively and reliably throughout the remaining experimental protocol. s-PSW could be elicited when the stimulus was given at any stage of the respiratory cycle but was most consistent when initiated during the postinspiratory phase (Fig. 1).

PSW was initially visualized as contractions of the pharyngeal muscles. Following neuromuscular blockade, s-PSW was observed as brief (∼300–500 ms), high amplitude, spindle-shaped bursts in cervical VNA (Fig. 1A). VNA recorded during swallowing in the present experimental setting mainly consists of the activity in the recurrent laryngeal nerve (Sun et al. 2011). The VNA activity during elicited PSW specifically reflects laryngeal adduction of the vocal folds, since laryngeal abductor motoneurons and muscles are inhibited during PSW (Van Daele et al. 2005; Suzuki et al. 2010).

Experimental protocol

Following optimization of water injections to elicit reproducible s-PSW, two control water stimulations at the chosen volume were performed before microinjections of drugs into the brainstem. All drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Australia) and dissolved in saline except where indicated.

Local microinjections of drugs (50–70 nl) into the KF or NTS were performed using multi-barrel borosilicate glass pipettes. The individual barrels were filled with l–glutamate (10 mm), rhodamine beads (2%) and with either isoguvacine (10 mm, GABAA receptor agonist) or bicuculline methiodide (10 mm, GABAA receptor antagonist) to inhibit or disinhibit regions of interest, respectively. The most effective concentration of bicuculline was determined by initial screening experiments using microinjections (n = 5 preparations) of either 1, 5 and 10 mm into the NTS or KF. The 10 mm dose of bicuculline was chosen as the experimental dose as it produced the most reproducible effects. The relatively high concentration needed relates to the specific experimental condition in situ, in which enlarged interstitial spaces in brainstem result in quick wash out of drugs and rapid dilution of injected drugs. Volumes of microinjections were monitored by movement of the liquid meniscus in relation to a calibrated scale, as examined through a microscope at high magnification.

Landmarks on the dorsal surface of the brainstem were used to approximate the rostro-caudal and medio-lateral coordinates of the KF (0.2–0.5 mm caudal to the caudal end of the inferior colliculus and 2.0–2.5 mm lateral to midline) and caudal NTS (0.5 mm lateral and 0.5 mm rostral to the calamus scriptorius) for microinjection. The dorso-ventral coordinates of the KF and NTS were approximately 1 mm and 0.1 mm deep to the dorsal surface of brainstem. The KF was more precisely identified by a postinspiratory breath-hold or tachypnoea elicited upon unilateral microinjection of glutamate (10 mm, 40 nl). After identification of the KF, microinjection of experimental drug was performed at the same site before moving the pipette to the same coordinates on the contralateral site for the second microinjection. The contralateral KF was not mapped with glutamate to prevent dilution of the effect of the experimental drug. Microinjection sites within the KF and NTS were marked by injecting fluorescent rhodamine beads following bilateral microinjections of drugs.

In all experiments, two water stimulations were performed within 5 min of the bilateral drug microinjection. The effect of injected drug on the respiratory pattern was allowed to wash out for at least 45 min before the response to two water stimulations were re-tested. At the end of experiments, the brainstem was removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis.

Histological verification of microinjection sites

Brainstems were fixed for several days in 4% paraformaldehyde and then transferred to 30% sucrose for at least a day before being serially sectioned at 50 μm using a microtome. The locations of microinjections, as indicated by rhodamine beads, were documented on schematic drawings of coronal sections showing the parabrachial complex of the dorsolateral pons or the dorsomedial medulla.

Data analyses

All analyses of nerve activity were performed offline using Chart software. To quantify the respiratory motor output at the different stages of the experimental protocol, 20 representative, sequential (where possible) respiratory cycles were analysed. The total length of a respiratory cycle (Ttot) was defined from the onset of the inspiratory burst in PNA to the onset of the subsequent burst. The inspiratory period (Ti) was measured from the onset of the PNA burst to its off-switch, which coincided with the high amplitude, decrementing burst in VNA. The postinspiratory period (Tpi) was defined from the onset of the high amplitude, decrementing burst in VNA to its offset. The expiratory period (Te) was defined by the silent period in VNA. For ease of analysis and illustrative purposes, recorded nerve activities were integrated and smoothed (τ = 0.05 s).

The baseline period was chosen just prior to the first drug microinjection. The treatment period, i.e. after bilateral microinjection of drug, was taken at least 30 s after the second microinjection of drug to exclude non-specific volume effects. The recovery period was judged according to the half-life of the specific drug injected. Typically, this was at least 45 min or 1.5 h after the second injection of isoguvacine and bicuculline, respectively. Where relevant, care was taken to choose representative respiratory cycles that were at least three cycles after water stimulation in case of any delayed elicited swallowing.

For each stage of the experimental protocol, elicited s-PSW was reported as the averaged response of two water stimulations. Water stimulation reproducibly resulted in fast s-PSW. In some experiments, swallows towards the end of the s-PSW significantly slowed down and were characterized by >1.5 standard deviations of the inter-swallow period during the earlier fast swallows. The slower swallows were not associated with an obvious tonic VNA component and thus were not included in the analysis. However, these were included when counting the number of total elicited swallows within a s-PSW sequence, as defined as all swallows from the first elicited swallow to the last swallow before the return of phrenic nerve discharge.

Pharmacological manipulation of the KF exclusively affected the tonic background component of the elicited s-PSW sequence. Because the tonic VNA component is small in relation to the dominant phasic VNA discharges, the tonic component was extracted from the total integrated signal of the s-PSW sequence. To do so, phasic VNA bursts were subtracted from the total integrated VNA during s-PSW.

Finally, the occurrence of spontaneous PSW was estimated by counting swallows observed during 20 consecutive respiratory cycles before and immediately after bilateral microinjection into either the KF or NTS.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (v.6). Almost all statistical tests used, unless otherwise stated, were one-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Tukey tests to compare between baseline, treatment and recovery periods. All statistical data are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Forty-one decerebrate, arterially perfused preparations of juvenile rat were used in this study. In all preparations, the PNA and VNA were recorded to monitor breathing pattern. The fictive breathing pattern in situ is reminiscent of the 3-phase pattern observed in the anaesthetized in vivo animal, e.g. Fig. 1A before water stimulation. At baseline, all preparations exhibited PNA featuring an augmenting burst discharge with an inspiratory period (Ti) of approximately 1 s or shorter. The postinspiratory period (Tpi), as measured from VNA, typically ranged from 0.6 to 3 s. HNA (Fig. 1A–C) or AbNA (Fig. 1D and E) was additionally recorded in subsets of animals. HNA consistently exhibited pronounced preinspiratory modulation. The onset of HNA bursts began typically ∼300 ms before the onset of inspiratory PNA, while the offset coincided with the burst onset of postinspiratory VNA (e.g. Fig. 1A). AbNA showed greater variability in its amplitude (not present, low or moderate) and respiratory modulation, although it was always confined to the expiratory phase as reported by others, e.g. tonic expiratory activity, phasic late expiratory bursting or phasic late expiratory and postinspiratory bursting (Abdala et al. 2009). Variability in AbNA is illustrated in Fig. 1D and E.

The present study focused on the coordination of breathing and swallowing briefly before and after evoked s-PSW. However, pharmacological manipulation of NTS activity, and likewise that of KF, resulted in significant changes in baseline breathing pattern in addition to the changes in s-PSW. In particular, bicuculline injections into either KF or NTS resulted in a profound increase in variability in the timing of recorded respiratory motor discharge. As our focus was on swallowing activity and respiratory activity immediately before, during and after evoked s-PSW, these complex effects on the baseline breathing pattern are not presented in full detail.

The KF selectively mediates the pharyngo-glottal reflex and contributes to inhibitory gating of swallowing

In all experiments the KF was localized by glutamate microinjection, which generally elicited a postinspiratory apnoea (Fig. 2B) when injected into the intermediate KF, or tachypnoea after injection into the rostral KF.

Bilateral microinjections of isoguvacine (10 mm, 50 nl) into the KF region were performed in 10 preparations. As previously reported by Dutschmann & Herbert (2006), isoguvacine reliably triggered apneusis (prolongation of Ti from 0.9 ± 0.2 s to 2.2 ± 0.8 s, ANOVA, P = 0.0001) and strongly attenuated postinspiratory VNA (Tpi from 2.1 ± 1.3 s to 0.3 ± 0.3 s, ANOVA, P = 0.0004; Fig. 2D and E). s-PSW was largely unaltered after KF inhibition (Fig. 2G). No significant changes were observed in the inter-swallowing interval (1.1 ± 0.3 s baseline vs. 0.9 ± 0.2 s, ANOVA, P = 0.13), amplitude (0.3 ± 0.1 μV baseline vs. 0.3 ± 0.1 μV, ANOVA, P = 0.50) or duration of swallowing-related VNA bursts (440 ± 90 ms baseline vs. 406 ± 72 ms, ANOVA, P = 0.11). There was also no difference in the total number of swallows in the elicited swallowing sequence (7.2 ± 2.4 baseline vs. 7.7 ± 3.1 post KF isoguvacine, ANOVA, P = 0.75). These findings are illustrated in Fig. 2G, where s-PSW patterns before and after isoguvacine are superimposed.

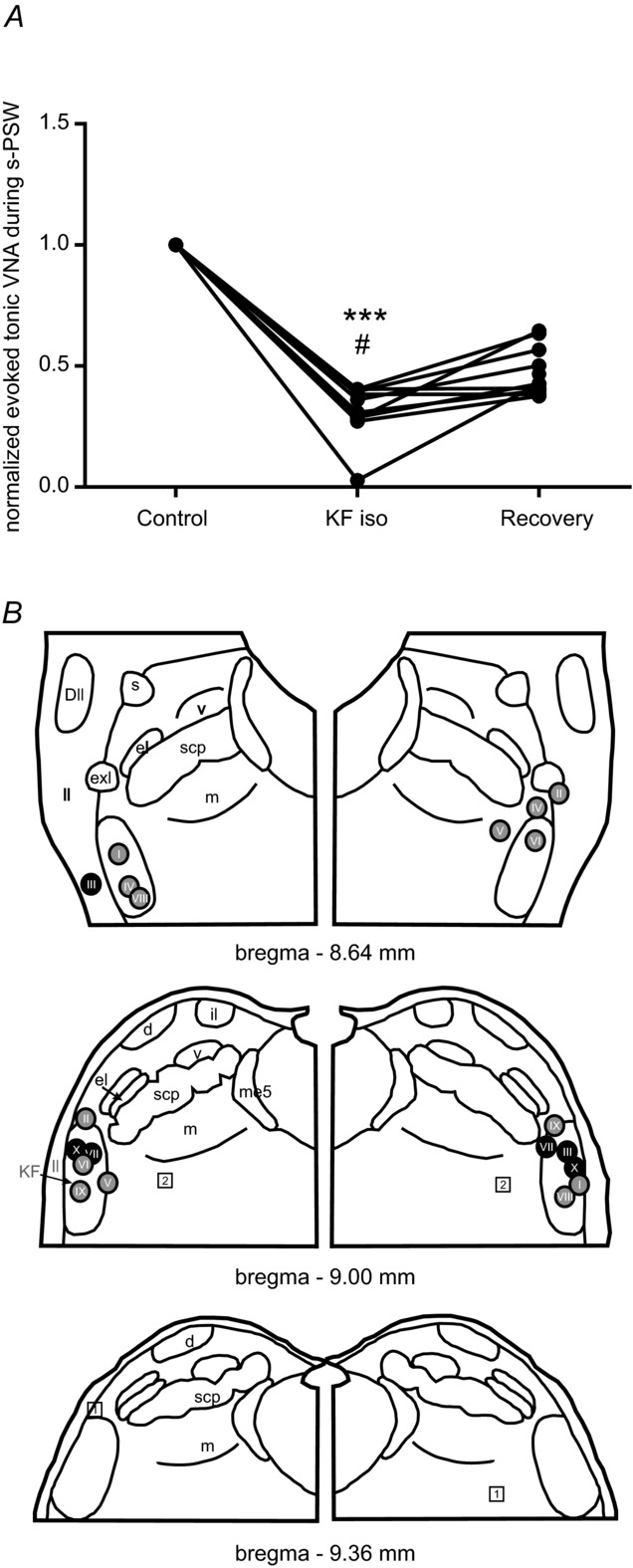

However, the tonic VNA component of the evoked PSW sequence was significantly diminished to 31.3 ± 11.3% of baseline after bilateral injection of isoguvacine into the KF (ANOVA, P < 0.001, Figs 2G and 3A). Almost no s-PSW-related tonic VNA could be elicited in preparations (n = 4) in which postinspiratory activity was completely abolished after bilateral isoguvacine injection into the KF (see black circles in Fig. 3B). The tonic VNA component of s-PSW is thought to be associated with the previously described ‘pharyngo-glottal closure reflex’ (Shaker et al. 2003). Suppression of PNA (swallowing apnoea) was unchanged during elicited PSW sequences after inhibition of the KF region (Fig. 2E).

Figure 3. Summary of responses to water stimulation after inhibition of the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus.

A, line graph showing a reduction of tonic VNA component during evoked s-PSW after inhibition of the KF region by bilateral microinjections of isoguvacine. Normalized values are shown. However, the raw mean value of tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW after bilateral isoguvacine microinjections into KF was significantly reduced compared to the mean at baseline (***P < 0.001) and during recovery (#P < 0.01). B, semi-schematic drawing of the pontine parabrachial complex to illustrate location of the microinjection sites (I–X). Colour-coding of the injection sites reflects the magnitude of the effect of isoguvacine on the tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW. Black circles reflect a reduction of tonic VNA of 70–100%. Grey circles reflect 30–70% reduction in tonic VNA. Squares reflect ineffective microinjection sites (0–20% reduction). Abbreviations: Dll, dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus; me5, mesencephalic trigeminal neurons; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle. Nuclei of the parabrachial complex: d, dorsal nucleus; el, external lateral nucleus; exl, extreme lateral nucleus; il, internal lateral nucleus; KF, Kölliker–Fuse nucleus; m, medial nucleus; v, ventral nucleus.

Bilateral isoguvacine microinjections into the KF further resulted in a significant increase in the number of spontaneous PSW bursts observed (see Fig. 2C and D; 0.4 ± 1.0 baseline vs. 5.5 ± 6.8 post KF isoguvacine, ANOVA, P = 0.0091). The increased incidence of spontaneous PSW was greatest during the immediate period following isoguvacine microinjections and the drastic change in baseline respiratory pattern (see Fig. 2C and D).

All isoguvacine effects on the respiratory pattern, the magnitude of the tonic VNA component of the elicited PSW sequence, and the occurrence of spontaneous PSW recovered to baseline parameters at least partially after ∼45 min (Figs 2F and 3A). This experimental series clearly indicates that the tonic VNA associated with fast sequential swallowing represents a separate KF-mediated reflex identity, named the pharyngo-glottal reflex (Shaker et al. 1998).

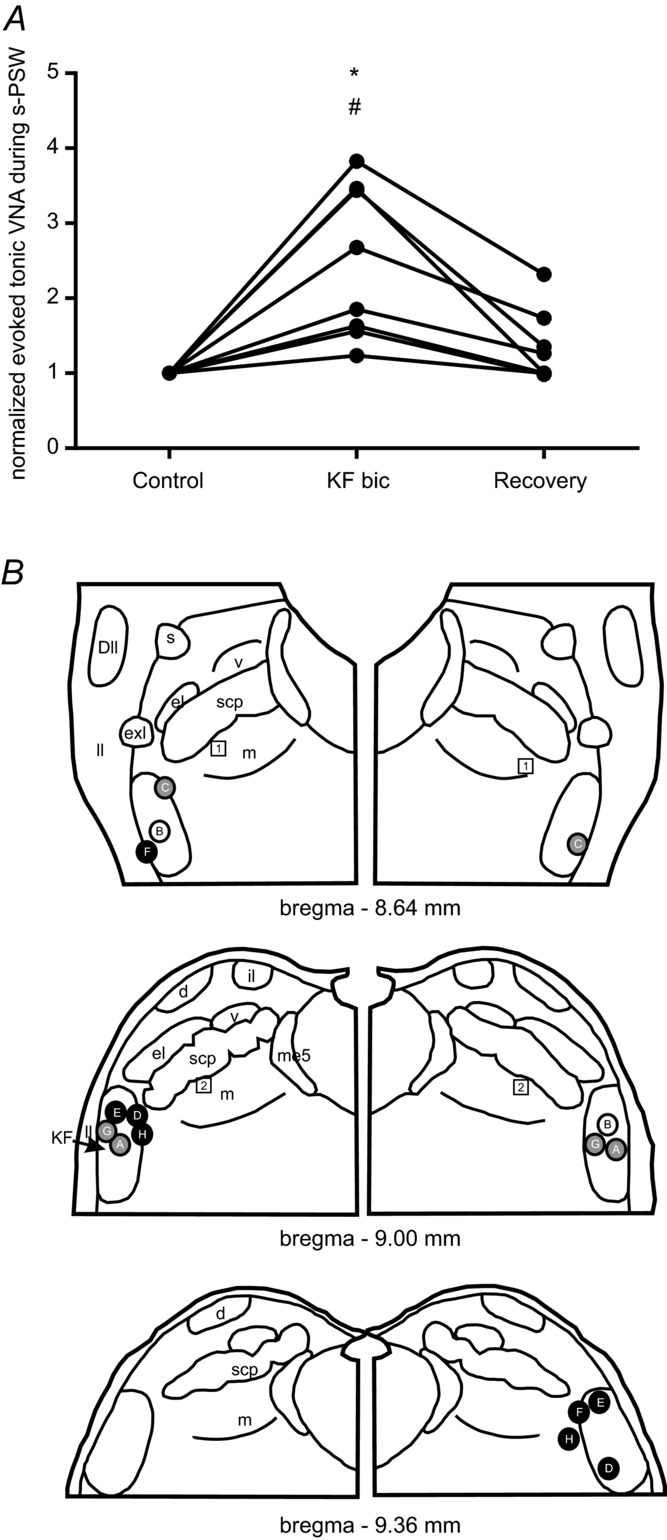

The pharyngo-glottal reflex dominates over swallowing activity after disinhibition of KF

Bilateral bicuculline microinjections into the KF region (n = 8 preparations, 10 mm, 50 nl) triggered complex effects on baseline respiratory parameters as illustrated by the increased coefficient of variation of all respiratory parameters (ANOVA, Ti: P = 0.0006, Tpi: P = 0.0001, Te: P = 0.0007, Ttot: P = 0.0001). In all preparations, occasional prolonged discharges appeared in PNA that consisted of both normal augmenting inspiratory discharge and disinhibited postinspiratory discharge. Seven out of the eight preparations exhibited spontaneous postinspiratory discharges in VNA (data not shown).

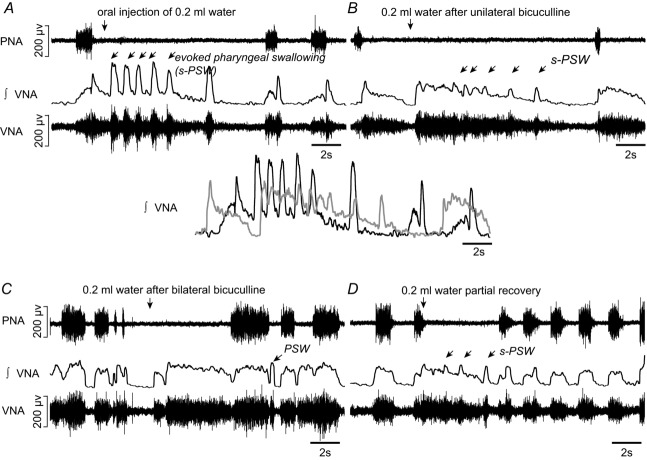

Disinhibition of the KF by bilateral microinjections of bicuculline (Fig. 4B and C) had a profound influence on the evoked s-PSW. In a subset of preparations in which water stimulation was performed after unilateral bicuculline injection (n = 5), the tonic VNA component (pharyngo-glottal closure reflex) of the elicited s-PSW increased such that phasic PSW-related VNA bursts were almost completely obscured (Fig. 4B). The phasic bursts in VNA were more obvious during the later stage of the s-PSW sequence (Fig. 4B). This effect was further exaggerated following bilateral microinjections of bicuculline. Consequently, tonic VNA and thus the pharyngo-glottal closure reflex was the dominant response to water stimulation (see Fig. 4C). The integrated tonic VNA significantly increased when compared to baseline (246 ± 101% of baseline, ANOVA, P = 0.010, n = 8) (Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, discernible sequential PSW could still be detected after the initial tonic activity. Additionally in n = 6/8 preparations, noticeable disruption to the swallow-related inhibition of PNA was observed. In such cases, an exaggerated pharyngo-glottal closure reflex was followed by inspiration before the onset of s-PSW or inspiratory break-throughs during the delayed PSW were observed (e.g. Fig. 4C). Both motor patterns could functionally lead to aspiration because inspiratory PNA occurs at a stage when the upper airways are insufficiently cleared of the injected fluid. The total number of swallows during the elicited PSW sequence was also reduced (5.8 ± 2.0 baseline vs. 2.2 ± 3.2 post KF bicuculline, ANOVA, P = 0.037), further underlining that PSW may become functionally insufficient in clearing the upper airways of fluid after KF disinhibition. The effects of bicuculline on the respiratory patterning and the elicited swallowing response required at least 1.5 h to recover to baseline values.

Figure 4. Swallowing activity after disinhibition of the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus.

A, evoked sequential pharyngeal swallowing (s-PSW, arrows) during baseline conditions. B, unilateral microinjection of GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (10 mm, 50 nl) increased postinspiratory activity in VNA. Amplitude of tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW was also increased. Below, the overlay of integrated evoked s-PSW-related VNA before (black) and after (grey) illustrates the relative increase in the tonic VNA. C, water stimulation after bilateral microinjections of bicuculline resulted in exaggerated tonic VNA without evidence of phasic s-PSW initially. A single delayed PSW was observed after an inspiratory burst in phrenic nerve. D, partial recovery of the s-PSW response to water stimulation after 90 min. Notice the reappearance of s-PSW-related VNA despite the elevated tonic VNA.

Figure 5. Summary of responses to water stimulation after disinhibition of the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus.

A, line graph showing an increase in the tonic VNA component during evoked s-PSW after disinhibition of the KF region by bilateral microinjections of bicuculline. Normalized values are shown. However, the raw mean value of tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW after bilateral bicuculline microinjections into KF was significantly increased compared to the mean at baseline (*P < 0.01) and during recovery (#P < 0.01). B, semi-schematic drawing of the pontine parabrachial complex to illustrate location of the microinjection sites (A–H). Colour-coding of the injection sites reflects the magnitude of the effect of bicuculline on the tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW. Black circles reflect an increase in tonic VNA of >150%. Grey circles reflect 50–150% increase in tonic VNA. Squares reflect ineffective microinjection sites (increase <50%). For abbreviations see Fig. 3.

Unlike microinjections of isoguvacine into the KF region, bilateral microinjections of bicuculline were not associated with an increase in the incidence of spontaneous PSW. On the contrary, spontaneous PSW was rare and occurrence was not significantly different compared to baseline (0.8 ± 0.8 baseline vs. 0.8 ± 1.1 post KF bicuculline, ANOVA, P = 0.14).

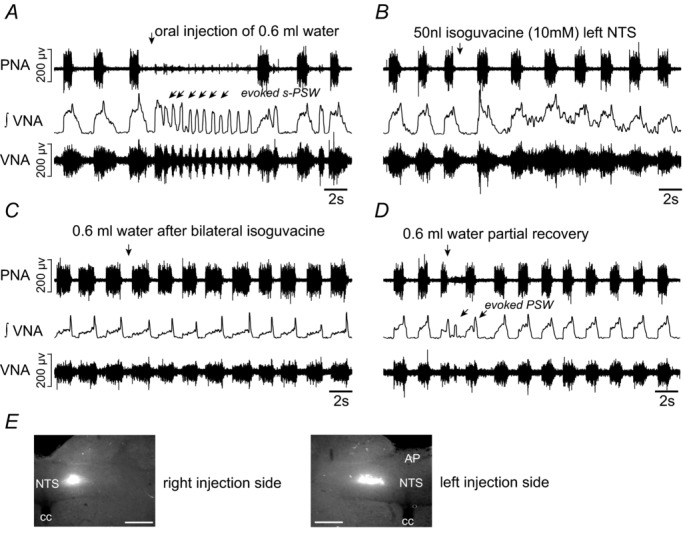

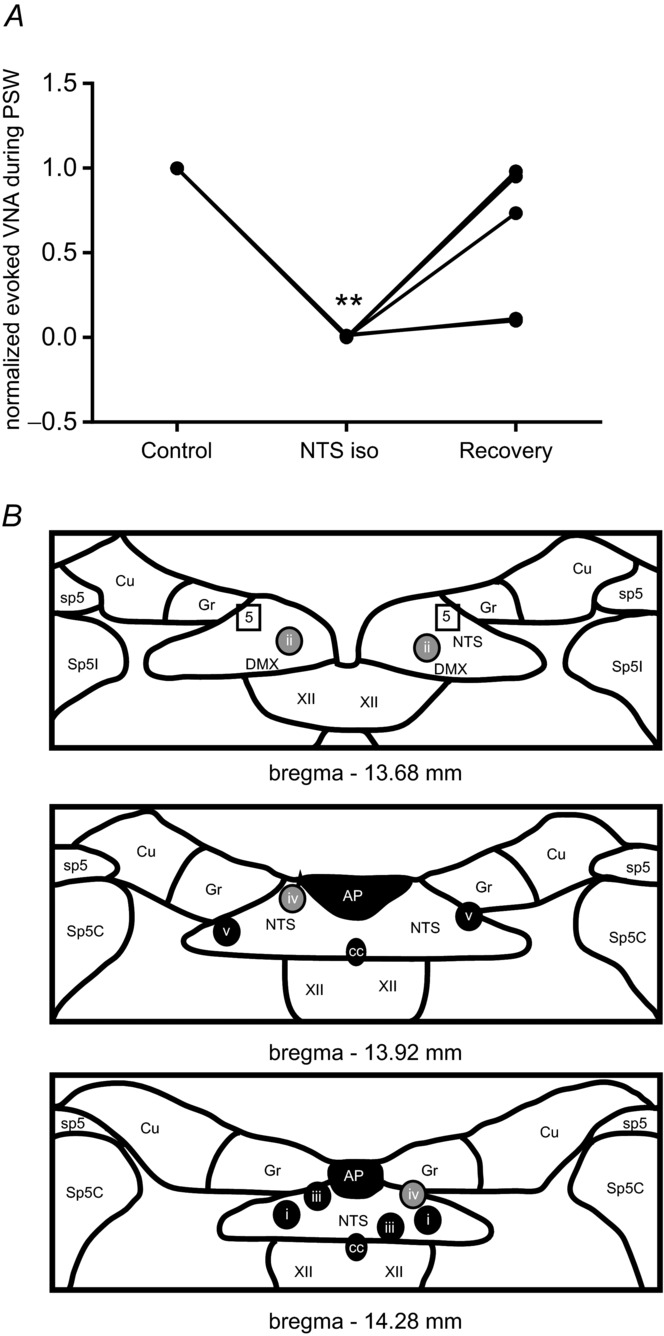

The caudal NTS contains the in situ central pattern generator for swallowing

Bilateral microinjections of isoguvacine into the lateral NTS at the caudal end of the area postrema (n = 5 preparations, 10 mm, 50 nl) gave rise to consistent changes in baseline respiratory pattern as previously reported by Wasserman et al. (2002). Briefly, the length of inspiratory PNA (Ti) increased, as shown in Fig. 6C (0.9 s ± 0.0 s to 1.4 ± 0.5 s, ANOVA, P = 0.042). This prolonged inspiratory PNA differed from the apneusis resulting from bilateral injection of isoguvacine into KF in that short postinspiratory bursts in VNA were still clearly detectable (Fig. 6C), albeit reduced in duration compared to baseline (1.7 ± 1.4 baseline to 0.3 ± 0.1 s, ANOVA, P = 0.048). These microinjections in addition almost abolished all evoked s-PSW (Figs 6C and D, and 7A) as reflected in the greatly reduced total number of elicited PSW bursts across all preparations (6.5 ± 2.9 baseline vs. 0.8 ± 1.4 post NTS isoguvacine, ANOVA, P = 0.0028). Effectively no spontaneous PSW was seen following bilateral isoguvacine injection into NTS (3.2 ± 4.6 baseline vs. 0.4 ± 0.9 post NTS isoguvacine, ANOVA, P = 0.17, n = 5). The isoguvacine NTS microinjections most effective in suppressing PSW were placed at the level of the caudal area postrema, while more rostrally placed injections were less effective or resulted in a normal s-PSW response with a similar number of swallows (Fig. 7B).

Figure 6. Swallowing activity after inhibition of the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract.

A, evoked sequential pharyngeal swallowing (s-PSW, arrows) during baseline conditions. B, unilateral microinjection of isoguvacine (10 mm, 50 nl) into the caudal NTS induces immediate prolongation of inspiratory period and shortening of postinspiratory activity. C, all responses to water stimulation were abrogated after bilateral microinjections of isoguvacine into the NTS. D, partial recovery of evoked s-PSW after 45 min. E, microinjection sites marked by rhodamine beads were found in the caudal portions of the NTS. The NTS is shown in relation to the central canal (cc) and area postrema (AP). Scale bar = 200 μm.

Figure 7. Summary of responses to water stimulation after inhibition of the NTS.

A, line graph showing a reduction of evoked VNA during s-PSW after isoguvacine injection into NTS. Normalized values are shown. However, the raw mean value of tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW after bilateral isoguvacine microinjections into NTS was significantly decreased compared to the mean at baseline (**P < 0.001) but not different compared to recovery. B, schematic diagrams illustrating bilateral injection (i–v) sites into the NTS. Colour-coding of the injection sites reflects the magnitude of the effect of isoguvacine on the tonic VNA during evoked s-PSW. Black circles reflect complete abolition of all spontaneous and evoked PSW. Grey circles reflect abolished spontaneous PSW and decreased VNA during evoked s-PSW (at least 25% decrease). Squares reflect ineffective injection site. Abbreviations: AP, area postrema; cc, central canal; Cu, cuneate nucleus; DMX, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve; Gr, gracile nucleus; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; sp5, spinal trigeminal tract; Sp5C, caudal nucleus of the spinal trigeminal tract; Sp5I, interpolar nucleus of the spinal trigeminal tract; XII, hypoglossal motor nucleus.

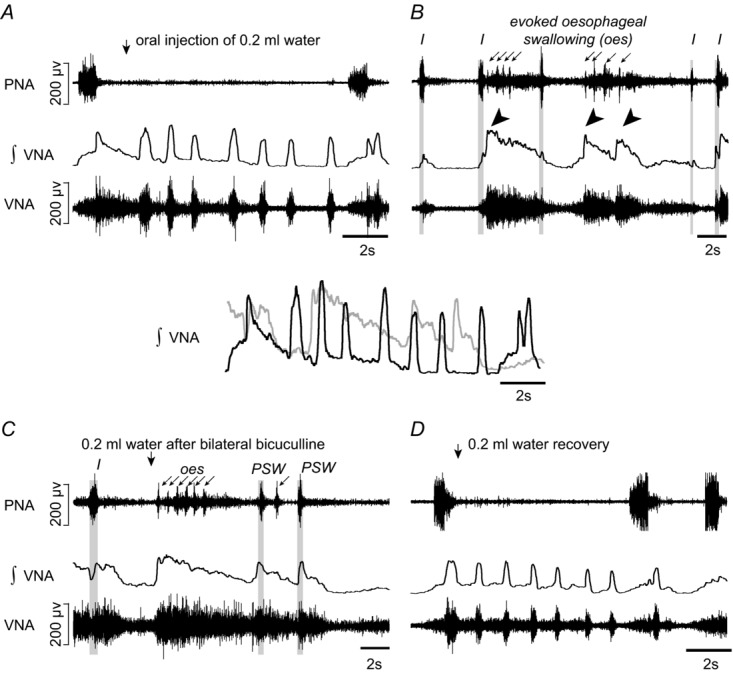

Generation of evoked sequential pharyngeal swallowing in situ depends on fast synaptic inhibition in the NTS

Bilateral microinjections of bicuculline into the NTS (n = 6 preparations, 10 mm, 50 nl) at the level of the area postrema resulted in significant perturbation of the baseline respiratory pattern by occurrence of frequent, spontaneous PSW activity in VNA and PNA. The respiratory disruption was such that normal inspiratory PNA-related activity was difficult to identify and thus quantify. Similar results were reported by Wasserman et al. (2002) in anaesthetized rat, in which bilateral bicuculline microinjections elicited a long-lasting apnoea that required artificial ventilation in most cases.

In the present study, large amplitude, decrementing bursts in VNA were repeatedly observed almost immediately after the second NTS microinjection of bicuculline (Fig. 8B). These VNA bursts were accompanied by short, rhythmic PNA bursts (∼90 ms, ∼4 bursts at 2.5 Hz; Fig. 8B). Importantly, the spontaneously occurring activities in VNA and PNA were remarkably similar to the dramatically altered s-PSW response to water stimulation after bilateral injection of bicuculline in NTS (Fig. 8B and C). The most notable change in the response to water stimulation compared to baseline was the loss of phasic PSW (Fig. 8C). Like the spontaneously occurring large decrementing VNA bursts, the evoked VNA was accompanied by small, rhythmic bursts in PNA presumably linked to oesophageal sphincter function of crural diaphragm (see arrows labelled with ‘oes’ in Fig. 8B and C). The evoked large decrementing burst in VNA was similar in duration (8.6 ± 2.6 s vs. 7.8 ± 2.0 s, ANOVA, P = 0.47) to the evoked s-PSW patterns at baseline (Fig. 8B and C). Altogether, the disordered evoked PSW was characterized by a highly significant increase in integrated VNA (187.4 ± 54.6%, ANOVA, P = 0.0001, Fig. 9A) and PNA (266.4 ± 108.3%, ANOVA, P = 0.0043) compared to baseline water stimulation.

Figure 8. Responses to water stimulation after disinhibition of the NTS.

A, evoked sequential pharyngeal swallowing (s-PSW, arrows) during baseline conditions. B, profound disruption to respiratory activity following bilateral microinjections of bicuculline (10 nm, 50 nl) into the caudal NTS caused by spontaneous cycles of large, decrementing s-PSW-related bursts in VNA (tilted arrowheads). The decrementing bursts in VNA were associated with tonic activity and small rhythmic bursts in PNA (arrows). Some relatively normal but shortened respiratory-related discharges in PNA and VNA (grey panelling; I-inspiration) were observed but were infrequent. C, the disordered response to water stimulation after bilateral microinjections of bicuculline into the NTS is very similar to the spontaneous cyclic activity in B. Some delayed bursts in VNA that resemble normal PSW-related bursts are shown in grey panelling. Above, an overlay of the response to water stimulation in integrated and smoothed VNA before (black) and after (grey) bilateral disinhibition of the NTS. D, recovery of the control response to swallow stimulation as well as normal respiratory discharges after 90 min. Note that both spontaneous (seen in B) and evoked (seen in C) PSW were always characterized by presumptive oesophageal swallowing (‘oes’) seen as the shortened bursts in the PNA recording.

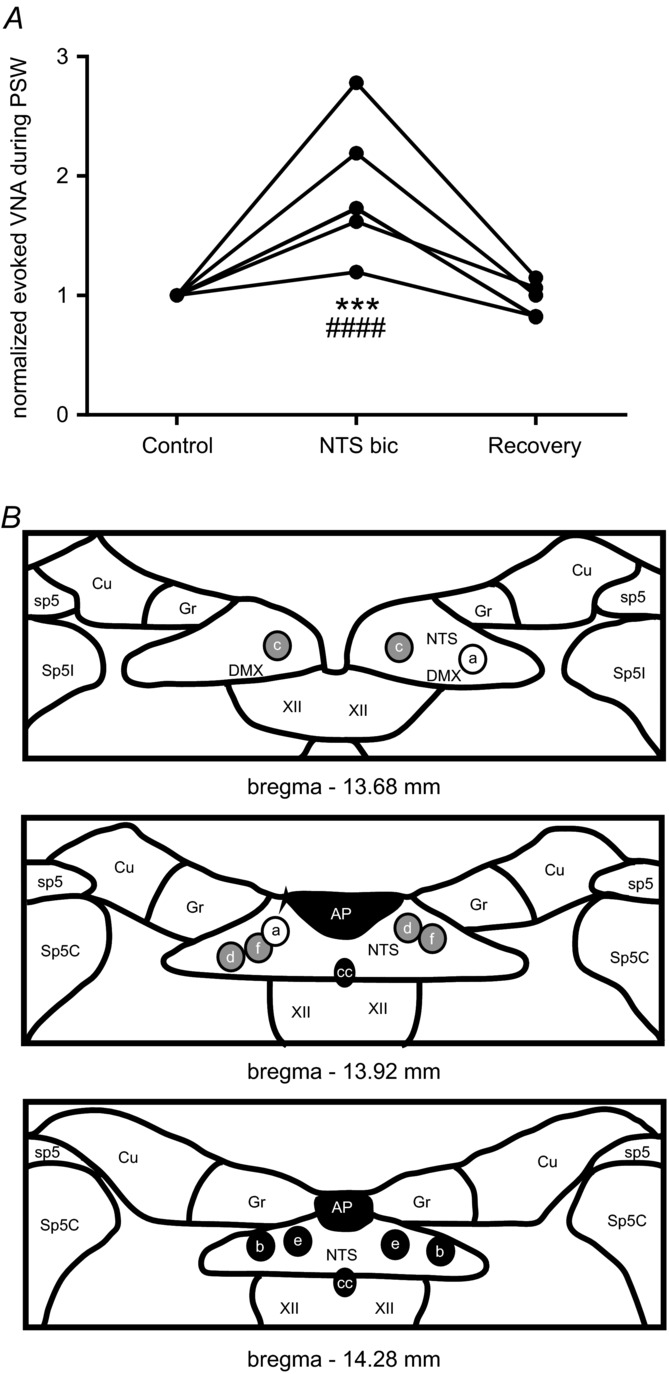

Figure 9. Summary of responses to water stimulation after disinhibition of the NTS.

A, line graph showing an increase of evoked VNA during PSW after bicuculline injection into NTS. Normalized values are shown. However, the raw mean value of evoked VNA during evoked PSW after bilateral bicuculline microinjections into NTS was significantly increased compared to the mean at baseline (***P < 0.0001) and during recovery (####P < 0.00001). B, schematic diagrams illustrating bilateral microinjection sites (a–f) into the NTS are shown. Colour-coding of the injection sites reflects the magnitude of the effect of bicuculline on VNA during evoked s-PSW. Black circles reflect an increase in evoked VNA >100%. Grey circles reflect 50–100% increase in evoked VNA. The white circle reflects an ineffective microinjection site. For abbreviations see Fig. 7.

Spontaneous PSW events continued to occur during recovery with a gradual change in pattern from the tonic burst response to periods of spontaneous PSW with clearly detectable individual swallowing bursts (data not shown). The declining frequency of spontaneous PSW events was associated with recovery of normal respiratory-related discharges in PNA and VNA. Stable, normal respiratory motor patterning and evoked fast sequential swallowing was recovered 45–70 min after bilateral bicuculline (Fig. 8D). Importantly, the large amplitude phrenic burst observed during the disordered evoked PSW returned to normal baseline amplitude (Fig. 8D, compared to Fig. 1A–C). The most effective bicuculline injection sites (Fig. 9B) showed a similar topography compared to the isoguvacine injection sites.

Discussion

We demonstrate that, upon oral water injection, a physiological and sequential pharyngeal swallowing pattern (s-PSW) can be reliably triggered in the perfused brainstem preparation. The in situ s-PSW pattern comprises two distinct components: (1) a phasic component indicated by short and decrementing bursts in VNA, and (2) a tonic component, indicated by background postinspiratory discharge in VNA. The present results demonstrate that the KF selectively mediates the tonic postinspiratory VNA component that is associated with the ‘pharyngo-glottal closure reflex’ (Shaker et al. 2003 and see below).

Disinhibition of the KF results in exaggeration of this reflex and delayed swallowing. On the other hand, generation of phasic s-PSW requires inhibitory transmission within the NTS since GABAA receptor blockade of this area results in a disordered response to water stimulation that lacks phasic swallowing. The current data also shed light on the gating of sw-CPG. KF blockade increased the occurrence of spontaneous PSW, suggesting that the KF provides a descending inhibitory input that gates the generation of s-PSW. GABAA receptor blockade within the sw-CPG circuits of the NTS triggered spontaneous generation of disordered PSW that suppressed respiratory motor activity for up to 1 h. Inhibitory gating from the KF and other sources therefore may also utilize GABAergic neurotransmission. Finally, we show that pharmacological manipulation of either KF or NTS disrupts baseline respiratory motor pattern by affecting the control of the postinspiratory phase.

The swallowing motor pattern in situ

This study is first to establish a reliable means to study s-PSW in response to a physiological stimulus in the in situ brainstem preparation of rodents, although others have previously reported swallowing in this experimental model (Paton et al. 1999; Smith et al. 2002). The major advantage of the decerebrate in situ preparation is the lack of anaesthesia, which depresses laryngeal adductor activity, swallowing and other airway protective reflexes (Bartlett, 1979; Nishino et al. 1987; Sun et al. 2011). Furthermore, in situ rats demonstrate swallowing/breathing interactions that are similar to humans, e.g. swallows are preferentially initiated in postinspiration (Saito et al. 2002; Sun et al. 2011).

Oro-pharyngeal water injection elicited s-PSW in the in situ perfused brainstem preparation that resembles swallowing while drinking a larger volume of water in humans (Aydogdu et al. 2011). Analysis of s-PSW showed maintenance of the physiological temporal relationship of peak tongue retractor activity (here reflected in HNA) occurring prior to peak laryngeal adduction (reflected in VNA) as well as prominent swallowing apnoea (inhibition of PNA) (Doty & Bosma, 1956). The observation that oral water injection simultaneously induced the pharyngo-glottal reflex (Shaker et al. 1998; Jadcherla et al. 2009) during s-PSW is also consistent with previous reports in rodents and humans (Dutschmann & Paton, 2002a; Shaker et al. 2003).

The KF mediates the pharyngo-glottal closure reflex during fast sequential pharyngeal swallowing

The KF gates the activity of postinspiratory neurons of the r-CPG and expression of eupnoeic laryngeal adductor activity (Dutschmann & Herbert, 2006; Dutschmann & Dick, 2012; Lindsey et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2013). Despite disruption of respiratory timing and loss of eupnoeic laryngeal adduction after KF inhibition, the timing, duration and amplitude of each swallow in the evoked s-PSW remained unchanged. Notably, the phasic laryngeal adduction during each swallow was unaffected by KF inhibition. However, KF inhibition selectively suppressed the tonic laryngeal adduction observed in addition to the s-PSW. Conversely, disinhibition of the KF resulted in exaggerated tonic laryngeal adduction that delayed the evoked s-PSW. Functionally, such a response represents an initial sustained laryngeal adduction or even laryngospasm until swallowing commences. The exaggerated evoked laryngeal adduction is similar to exaggerated postinspiratory apnoea after KF disinhibition (Dutschmann & Herbert, 1998).

Our data therefore support the notion that the KF has no role in the generation and patterning of s-PSW per se, but mediates a different laryngeal adductor reflex identity that is co-activated during fast s-PSW. This reflex is the previously described pharyngo-glottal closure reflex (Shaker et al. 1998; Jadcherla et al. 2009), which is a protective laryngeal adductor reflex in response to injection of small volumes of water into the oropharynx. It is also co-activated during s-PSW when ingesting larger volumes of water, as demonstrated here and by others (Dutschmann & Paton, 2002a; Shaker et al. 2003). However, such co-activation is rarely mentioned in the literature because studies concerned with the neural control of swallowing focused on single swallow activity. During a single swallow, additional airway protection is presumably less significant compared to s-PSW of larger amounts of fluid. Little is known of the neural pathways that subserve the pharyngo-glottal closure reflex besides that it is relayed through the glossopharyngeal nerve

(Shaker et al. 1998). Thus to our knowledge, this is the first study to relate a neural substrate to the mediation of the pharyngo-glottal closure reflex.

The NTS is the primary site of initiation and generation of pharyngeal swallowing in situ

We demonstrate that chemical inhibition of the NTS largely suppresses all elicited and spontaneous PSW, consistent with earlier studies that show that integrity of the dorsal swallowing group is required in peripherally and cortically induced PSW (Car et al. 1975; Jean & Car 1979; Kessler & Jean 1985; Wang & Beiger 1991). These experiments confirm that the sw-CPG is located within the NTS.

We further demonstrate that patterning of s-PSW requires fast synaptic inhibition in the NTS since local GABAA receptor blockade results in a significantly disturbed evoked response to water stimulation. After disinhibition, the evoked response was replaced by a tonic/decrementing discharge in the vagus nerve that reflected the failure to convert the tonic sensory signals encoding water stimulation of the oro-pharyngeal mucosa (Sant’Ambrogio et al. 1995) into a phasic and sequential PSW motor pattern. This strongly suggests that the sw-CPG is a neural oscillator reliant on reciprocal synaptic inhibition. Our results are in agreement with the demonstration by Saito and colleagues (2002, 2003) that respiratory neurons (e.g. Bötzinger expiratory neurons) receive differential and oscillating drive from the sw-CPG during sequential PSW.

Interestingly, our results differ from Wang & Bieger (1991) who report in urethane-anaesthetized rat that application of bicuculline onto the dorsal surface overlying NTS results in spontaneous but otherwise appropriately patterned s-PSW. The disparate results may be due to the greater concentration of bicuculline used in the current study. At high doses, bicuculline affects small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels and is also reported to potentiate NMDA-receptor-dependent burst firing (Johnson & Seutin, 1997; Khawaled et al. 1999). However, such non-specific excitatory effects cannot explain the failure to produce sequential vagal bursting after oral water injections. In addition, the facilitatory effect of anaesthesia on GABA neurotransmission means that a tonic level of inhibitory neurotransmission was probably present in the experimental design of Wang & Bieger (1991) that is absent in the decerebrate in situ preparation.

A curious observation was that all disordered PSW after NTS disinhibition were associated with rhythmic phrenic nerve bursts of very short duration compared to normal inspiratory activity. We propose that this swallowing-related phrenic activity is non-respiratory, since functionally such short phrenic bursts are insufficient to produce significant airflow into the lungs. In support of this, Wasserman et al. (2002) demonstrated in anaesthetized rat that a long-lasting suppression of respiration followed similar bicuculline microinjections into the NTS. A likely explanation is that the non-respiratory phrenic bursts are related to the external, lower oesophageal sphincter function of the crural diaphragm (Pickering & Jones, 2002), which is also innervated by the phrenic nerve. The relatively large microinjections may have affected the central subnucleus of the NTS, which contains the CPG for the oesophageal stage of swallowing (‘oes’) (Bieger, 1993; Lang, 2009).

KF-mediated gating of the sw-CPG

Swallowing is a ‘gated’ behaviour in that it is not ongoing unlike breathing. The sw-CPG in the NTS receives sensory synaptic inputs via the superior laryngeal and glossopharyngeal nerves and also from higher cortical areas that mediate the behavioural gating of PSW (Jean & Car, 1979; Kalia & Mesulam, 1980; Sweazey & Bradley, 1986). The observation of spontaneous (albeit disordered) PSW after NTS bicuculline is in line with previous investigations that provide evidence that the sw-CPG is under strong GABAergic inhibition at rest (Wang & Bieger, 1991). Thus, withdrawal of GABAergic inhibition may be an important central mechanism by which the sw-CPG is gated.

Data from the present and previous studies demonstrate that the KF may provide descending inhibitory gating of the sw-CPG during ongoing breathing as there is a significant increase in spontaneous PSW after KF inhibition or lesion (Bonis et al. 2011, 2013). This is anatomically supported by the fact that the KF reciprocally innervates several NTS subnuclei and the surrounding medullary reticular formation – areas known to participate in swallow generation (Herbert et al. 1990). The KF is also ideally positioned to mediate interaction between higher brain centres that induce behaviour-related swallowing and the sw-CPG in the medulla. The KF receives descending input from various forebrain and limbic brain areas (see Dutschmann & Dick, 2012). In addition, evidence for an ascending ‘pontine relay’ for conscious swallowing was shown previously (Car et al. 1975).

Synergy of CPGs for swallowing and respiration provide effective airway protection during PSW

Laryngeal adductor motoneurons are a final common pathway for sw-CPG and r-CPG premotor circuits whose corresponding muscles are valving the entry/exit into the lower airways during swallowing and breathing. Our results suggest that the sw-CPG and r-CPG synergize in producing maximal airway protection during fast s-PSW. That the composite sequential PSW motor pattern is the result of synergistic interaction of two functionally distinct CPGs is supported by the fact that: (i) KF inhibition did not significantly alter the ‘primary s-PSW pattern’ while eupnoeic postinspiratory motor drive to laryngeal adductors was completely abolished, and (ii) NTS inhibition abolished spontaneous and evoked PSW while eupnoeic postinspiratory drive was reduced but still present.

In summary we propose the following scenario of sw-CPG and r-CPG interaction. Oral water injection stimulates both superior laryngeal and glossopharyngeal nerves that both terminate in the NTS. s-PSW is generated within the sw-CPG circuitry in the NTS. The generated phasic s-PSW pattern is then conferred upon laryngeal adductor motoneurons (Jean, 2001). In parallel, the afferent input from the glossopharyngeal nerve is relayed via the NTS to the KF laryngeal premotor neurons, which provide additional airway protection via the activation of the pharyngo-glottal closure reflex during fast s-PSW.

Our data also imply that balanced synaptic interaction along the NTS/KF axis (Herbert et al. 1990; Song et al. 2011) is also pivotal for effective swallowing/breathing coordination. Imbalance of synaptic interaction between and within NTS and KF may have an important role in the pathophysiology of swallowing disorders (see ‘Translational perspective’ below). For instance, KF hyperexcitability produces an exaggerated pharyngo-glottal closure reflex that dominates and delays s-PSW despite parallel activation of the sw-CPG pathway via the superior laryngeal nerve. On the other hand, NTS hyperexcitability results in excessive spontaneous PSW that suppresses ongoing respiratory activity.

Revival of the dorsal and pontine respiratory group

The prolonged inspiratory duration observed here after NTS inhibition reveals that input from the NTS to the r-CPG is critical for the correct timing of the inspiratory off-switch. Similar results were reported in vagotomized rats in vivo (Wasserman et al. 2002). In both studies, the specific contribution of the NTS to inspiratory off-switch mechanisms was demonstrated in the absence of information from pulmonary stretch receptors that mediate the Hering–Breuer reflex (see Kubin et al. 2006). Therefore the intrinsic activity of the NTS, separate to its function as a relay for the Hering–Breuer reflex, contributes to the timing of the inspiratory off-switch. This observation revives the discussion of a potential role of the dorsal respiratory group in r-CPG function. The dorsal respiratory group of the NTS was classically considered as an integral part of the r-CPG in cat because it contains inspiratory bulbo-spinal projection neurons (see Berger, 1977; Lipski & Merrill, 1980; Long & Duffin, 1986; Bianchi et al. 1995). Recently, appreciation of the dorsal respiratory group has waned because bulbo-spinal NTS neurons are sparse in rat (Saether et al. 1987; Ezure et al. 1988; Dobbins & Feldman, 1994; Bianchi et al. 1995; Tian & Duffin, 1998), which has become the preferred animal model for studies in respiratory control. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with the notion that the NTS interacts with other r-CPG nuclei that mediate the inspiratory off-switch, such as the KF. An ‘efference copy model’ for inspiratory off-switching based on ascending medullary inspiratory input to the KF was proposed previously (see Mörschel & Dutschmann, 2009).

The importance of the KF as part of the pontine respiratory group in the control of respiratory motor patterning (Dutschmann & Herbert, 2006; also see Smith et al. 2007) is again illustrated in the present study. The observed, highly variable postinspiratory phase durations and frequent incidence of postinspiratory apnoea (breath-hold) after KF disinhibition further highlights the importance of KF in the formation of the eupnoeic respiratory motor pattern in situ.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Sarah Jones and Davor Stanic for their assistance with the histology.

Glossary

- AbNA

abdominal nerve activity (iliohypogastric branch)

- HNA

hypoglossal nerve activity

- KF

Kölliker–Fuse nucleus

- NTS

nucleus of the solitary tract

- PNA

phrenic nerve activity

- PSW

pharyngeal swallowing

- r-CPG

respiratory central pattern generator

- s-PSW

sequential pharyngeal swallowing

- sw-CPG

swallowing central pattern generator

- VNA

vagal nerve activity

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Both T. G. Bautista and M. Dutschmann were involved in all of the following: conception and design of experiments, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. The experiments were performed at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, Melbourne, Australia. All persons designated for authors qualify for authorship and all those who qualify for authorship are listed. Both authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors’ work is funded by a start-up fund from the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health. M. Dutschmann is supported by an ARC Future Fellowship (FT120100953).

Translational perspective

The distinct changes in sequential pharyngeal swallowing after Kölliker–Fuse nucleus (KF) disinhibition in the in situ rat preparation are strikingly similar to swallowing patterns observed in patients of the neurodevelopmental disease Rett syndrome (Morton et al. 1997, 2000; Isaacs et al. 2003). Such patients exhibit prolonged breath-holds followed by late swallows upon oral presentation of liquids (Morton et al. 1997). The similarity of our results strengthens the proposal that disordered breathing and upper airway behaviours (including swallow) in Rett syndrome are closely linked to KF hyper-excitability caused by reduced GABAergic inhibition of KF neurons (Stettner et al. 2007; Abdala et al. 2010). Swallowing/breathing dis-coordination due to synaptic imbalance along the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS)–KF axis may also be of relevance to the aspiration pneumonia common in elderly patients and those with Alzheimer's disease, Parkinsonism or fronto-temporal dementia (Finiels et al. 2001; Easterling & Robbins, 2008; Alagiakrishnan et al. 2013). Patients and transgenic mouse models of these diseases exhibit marked neurodegeneration linked to tauopathy in NTS–KF circuitry (Rüb et al. 2001, 2002; Dutschmann et al. 2010; Menuet et al. 2011). Whether tauopathy of the NTS–KF pathway for airway protection during pharyngeal swallowing causes the high incidence of aspiration in patients of neurodegenerative disease needs to be verified in multidisciplinary research studies involving human and animal physiology.

References

- Abdala AP, Rybak IA, Smith JC, Paton JF. Abdominal expiratory activity in the rat brainstem-spinal cord in situ: patterns, origins and implications for respiratory rhythm generation. J Physiol. 2009;587:3539–3559. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdala APL, Dutschmann M, Bissonnette JM, Paton JFR. Correction of respiratory disorders in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18208–18213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012104107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagiakrishnan K, Bhanji RA, Kurian M. Evaluation and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different types of dementia: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alheid GF, Milsom WK, McCrimmon DR. Pontine influences on breathing: an overview. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;143:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydogdu I, Tanriverdi Z, Ertekin C. Dysfunction of bulbar central pattern generator in ALS patients with dysphagia during sequential deglutition. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett D., Jr Effects of hypercapnia and hypoxia on laryngeal resistance to airflow. J Physiol. 1979;37:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(79)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett D., Jr . Upper airway motor systems. In: Cherniack NS, Widdicombe JG, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 3, The Respiratory System, vol. II, Control of Breathing, part 1. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Physiological Society; 1986. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Berger AJ. Dorsal respiratory group neurons in the medulla of cat: spinal projections, responses to lung inflation and superior laryngeal nerve stimulation. Brain Res. 1977;135:231–254. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)91028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi AL, Denavit-Saubié M, Champagnat J. Central control of breathing in mammals: neuronal circuitry, membrane properties, and neurotransmitters. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:1–45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi AL, Gestreau C. The brainstem respiratory network: An overview of a half century of research. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;168:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieger D. The brainstem esophagomotor network pattern generator: A rodent model. Dysphagia. 1993;8:203–208. doi: 10.1007/BF01354539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieger D, Hopkins DA. Viscerotopic representation of the upper alimentary tract in the medulla oblongata in the rat: the nucleus ambiguus. J Comp Neurol. 1987;262:546–562. doi: 10.1002/cne.902620408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser DC, Poliacek I, Jakus J, Fuller DD, Davenport PW. Neurogenesis of cough, other airway defensive behaviors and breathing: A holarchical system? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;152:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonis JM, Neumueller SE, Marshall BD, Krause KL, Qian B, Pan LG, Hodges MR, Forster HV. The effects of lesions in the dorsolateral pons on the coordination of swallowing and breathing in awake goats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;175:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonis JM, Neumueller SE, Krause KL, Pan LG, Hodges MR, Forster HV. Contributions of the Kölliker-Fuse nucleus to coordination of breathing and swallowing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;189:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Car A, Jean A, Roman C. A pontine primary relay for ascending projections of the superior laryngeal nerve. Exp Brain Res. 1975;22:197–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00237689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport PW, Bolser DC, Morris KF. Swallow remodeling of respiratory neural networks. Head Neck. 2011;33:S8–S13. doi: 10.1002/hed.21845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins EG, Feldman JL. Brainstem network controlling descending drive to phrenic motoneurons in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1994;347:64–86. doi: 10.1002/cne.903470106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RW, Bosma JF. An electromyographic analysis of reflex deglutition. J Neurophysiol. 1956;19:44–60. doi: 10.1152/jn.1956.19.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Dick T. Pontine mechanisms of respiratory control. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:2443–2469. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Herbert H. NMDA and GABAA receptors in the rat Kölliker–Fuse area control cardiorespiratory responses evoked by trigeminal ethmoidal nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 1998;510:793–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.793bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Herbert H. The Kölliker-Fuse nucleus gates the postinspiratory phase of the respiratory cycle to control inspiratory off-switch and upper airway resistance in rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1071–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Menuet C, Stettner GM, Gestreau C, Borghgraef P, Devijver H, Gielis L, Hilaire G, Van Leuven F. Upper airway dysfunction of Tau-P301L mice correlates with tauopathy in midbrain and ponto-medullary brainstem nuclei. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1810–1821. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5261-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Morschel M, Rybak IA, Dick TE. Learning to breathe: control of the inspiratory/expiratory phase transition shifts from sensory- to central-dominated during postnatal development in rats. J Physiol. 2009;587:4931–4948. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Paton J. Influence of nasotrigeminal afferents on medullary respiratory neurones and upper airway patency in the rat. Pflugers Arch. 2002a;444:227–235. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0797-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Paton JFR. Glycinergic inhibition is essential for co-ordinating cranial and spinal respiratory motor outputs in the neonatal rat. J Physiol. 2002b;543:643–653. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterling CS, Robbins E. Dementia and dysphagia. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezure K, Manabe M, Yamada H. Distribution of medullary respiratory neurons in the rat. Brain Res. 1988;455:262–270. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezure K, Oku Y, Tanaka I. Location and axonal projection of one type of swallowing interneurons in cat medulla. Brain Res. 1993;632:216–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91156-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finiels H, Strubel D, Jacquot JM. Deglutition disorders in the elderly. Epidemiological aspects. Presse Med. 2001;30:1623–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestreau C, Grelot L, Bianchi AL. Activity of respiratory laryngeal motoneurons during fictive coughing and swallowing. Exp Brain Res. 2000;130:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s002210050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Wallén P. Central pattern generators for locomotion, with special reference to vertebrates. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1985;8:233–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.08.030185.001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross R, Atwood C, Ross S, Eichhorn K, Olszewski J, Doyle P. The coordination of breathing and swallowing in Parkinson's Disease. Dysphagia. 2008;23:136–145. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikoutis S, Pickersgill TP, Dawson K, Wiles CM. Abnormal patterns of breathing during swallowing in neurological disorders. Brain. 2000;123:1863–1873. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.9.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R. Perinatal development of laryngeal function. J Dev Physiol. 1984;6:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert H, Moga MM, Saper CB. Connections of the parabrachial nucleus with the nucleus of the solitary tract and the medullary reticular formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;293:540–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs JS, Murdock M, Lane J, Percy AK. Eating difficulties in girls with Rett syndrome compared with other developmental disabilities. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:224–230. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Wang M, Coley BD, Fernandez S, Shaker R. Definition and implications of novel pharyngo-glottal reflex in human infants using concurrent manometry ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2572–2582. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean A. Brain stem control of swallowing: neuronal network and cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:929–969. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean A, Car A. Inputs to the swallowing medullary neurons from the peripheral afferent fibers and the swallowing cortical area. Brain Res. 1979;178:567–572. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, Seutin V. Bicuculline methiodide potentiates NMDA-dependent burst firing in rat dopamine neurons by blocking apamin-sensitive Ca2+-activated K+ currents. Neurosci Lett. 1997;231:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M. Dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Metabolism. 2003;52(Suppl. 2):36–38. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(03)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Mesulam MM. Brain stem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus complex in the cat: II. Laryngeal, tracheobronchial, pulmonary, cardiac, and gastrointestinal branches. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:467–508. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler J, Jean A. Identification of the medullary swallowing regions in the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1985;57:256–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00236530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawaled R, Bruening-Wright A, Adelman JP, Maylie J. Bicuculline block of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Pflugers Arch. 1999;438:314–321. doi: 10.1007/s004240050915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin L, Alheid GF, Zuperku EJ, McCrimmon DR. Central pathways of pulmonary and lower airway vagal afferents. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:618–627. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00252.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I. Brain stem control of the phases of swallowing. Dysphagia. 2009;24:333–348. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-W, Chang Y-C, Chen W-S, Chang K, Chang H-Y, Wang T-G. Prolonged swallowing time in dysphagic parkinsonism patients with aspiration pneumonia. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2012;93:2080–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey BG, Rybak IA, Smith JC. Computational models and emergent properties of respiratory neural networks. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:1619–1670. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipski J, Merrill EG. Electrophysiological demonstration of the projection from expiratory neurones in rostral medulla to contralateral dorsal respiratory group. Brain Res. 1980;197:521–524. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S, Duffin J. The neuronal determinants of respiratory rhythm. Prog Neurobiol. 1986;27:101–182. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(86)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medda BK, Kern M, Ren J, Xie P, Ulualp SO, Lang IM, Shaker R. Relative contribution of various airway protective mechanisms to prevention of aspiration during swallowing. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G933–G939. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00395.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menuet C, Borghgraef P, Matarazzo V, Gielis L, Lajard AM, Voituron N, Gestreau C, Dutschmann M, Van Leuven F, Hilaire G. Raphé tauopathy alters serotonin metabolism and breathing activity in terminal Tau.P301L mice: possible implications for tauopathies and Alzheimer's disease. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;178:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mörschel M, Dutschmann M. Pontine respiratory activity involved in inspiratory/expiratory phase transition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton RE, Bonas R, Minford J, Tarrant SC, Ellis RE. Respiration patterns during feeding in Rett syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:607–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton RE, Pinnington L, Ellis RE. Air swallowing in Rett syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:271–275. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino T, Kochi T, Shirahata M, Yonezawa T. Effects of increasing depths of anesthesia on phrenic and hypoglossal nerve activity during the swallowing reflex in cats. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57:208–213. doi: 10.1093/bja/57.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino T, Takizawa K, Yokokawa N, Hiraga K. Depression of the swallowing reflex during sedation and/or relative analgesia produced by inhalation of 50% nitrous oxide in oxygen. Anesthesiology. 1987;67:995–998. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198712000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku Y, Dick TE. Phase resetting of the respiratory cycle before and after unilateral pontine lesion in cat. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:721–730. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.2.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JFR. A working heart–brainstem preparation of the mouse. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;65:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JFR, Li YW, Kasparov S. Reflex response and convergence of pharyngoesophageal and peripheral chemoreceptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Neuroscience. 1999;93:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering M, Jones JF. The diaphragm: two physiological muscles in one. J Anat. 2002;201:305–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts T, Rose MJ, Mortensen AN, Poliacek I, Sapienza CM, Lindsey BG, Morris KF, Davenport PW, Bolser DC. Coordination of cough and swallow: a meta-behavioral response to aspiration. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;189:543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüb U, Del Tredici K, Schultz C, Thal DR, Braak E, Braak H. The autonomic higher order processing nuclei of the lower brain stem are among the early targets of the Alzheimer's disease-related cytoskeletal pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101:555–564. doi: 10.1007/s004010000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüb U, Del Tredici K, Schultz C, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Arai K, Braak H. Progressive supranuclear palsy: neuronal and glial cytoskeletal pathology in the higher order processing autonomic nuclei of the lower brainstem. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2002;28:12–22. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saether K, Hilaire G, Monteau R. Dorsal and ventral respiratory groups of neurons in the medulla of the rat. Brain Res. 1987;419:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90571-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Ezure K, Tanaka I. Swallowing-related activities of respiratory and non-respiratory neurons in the nucleus of solitary tract in the rat. J Physiol. 2002;540:1047–1060. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Ezure K, Tanaka I, Osawa M. Activity of neurons in ventrolateral respiratory groups during swallowing in decerebrate rats. Brain Dev. 2003;25:338–345. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant’Ambrogio G, Tsubone H, Sant’Ambrogio FB. Sensory information from the upper airway: role in the control of breathing. Respir Physiol. 1995;102:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00048-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker R, Li Q, Ren J, Townsend WF, Dodd WJ, Martin BJ, Kern MK, Rynders A. Coordination of deglutition and phases of respiration: Effect of aging, tachypnea, bolus volume and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1992;263:G750–G755. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.5.G750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker R, Medda BK, Ren J, Jaradeh S, Xie P, Lang IM. Pharyngoglottal closure reflex: Identification and characterization in a feline model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1998;275:G521–G525. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.3.G521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker R, Ren J, Bardan E, Easterling C, Dua K, Xie P, Kern M. Pharyngoglottal closure reflex: Characterization in healthy young, elderly and dysphagic patients with predeglutitive aspiration. Gerontology. 2003;49:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000066504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba K, Nakazawa K, Ono K, Umezaki T. Multifunctional laryngeal premotor neurons: their activities during breathing, coughing, sneezing, and swallowing. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5156–5162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0001-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba K, Satoh I, Kobayashi N, Hayashi F. Multifunctional laryngeal motoneurons: an intracellular study in the cat. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2717–2727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02717.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Abdala APL, Borgmann A, Rybak IA, Paton JFR. Brainstem respiratory networks: Building blocks and microcircuits. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Abdala AP, Koizumi H, Rybak IA, Paton JF. Spatial and functional architecture of the mammalian brain stem respiratory network: a hierarchy of three oscillatory mechanisms. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:3370–3387. doi: 10.1152/jn.00985.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Paton JFR, Andrews PLR. An arterially perfused decerebrate preparation of Suncus murinus (house musk shrew) for the study of emesis and swallowing. Exp Physiol. 2002;87:563–574. doi: 10.1113/eph8702424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Xu H, Wang H, MacDonald SM, Poon CS. Hypoxia-excited neurons in NTS send axonal projections to Kölliker-Fuse/parabrachial complex in dorsolateral pons. Neuroscience. 2011;175:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stettner GM, Huppke P, Brendel C, Richter DW, Gartner J, Dutschmann M. Breathing dysfunctions associated with impaired control of postinspiratory activity in Mecp2–/y knockout mice. J Physiol. 2007;579:863–876. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama Y, Shiba K, Nakazawa K, Suzuki T, Umezaki T, Ezure K, Abo N, Yoshihara T, Hisa Y. Axonal projections of medullary swallowing neurons in guinea pigs. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:2193–2211. doi: 10.1002/cne.22624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]