Abstract

These experiments on the human forearm are based on the hypothesis that drift in the perceived position of a limb over time can be explained by receptor adaptation. Limb position sense was measured in 39 blindfolded subjects using a forearm-matching task. A property of muscle, its thixotropy, a contraction history-dependent passive stiffness, was exploited to place muscle receptors of elbow muscles in a defined state. After the arm had been held flexed and elbow flexors contracted, we observed time-dependent changes in the perceived position of the reference arm by an average of 2.8° in the direction of elbow flexion over 30 s (Experiment 1). The direction of the drift reversed after the arm had been extended and elbow extensors contracted, with a mean shift of 3.5° over 30 s in the direction of elbow extension (Experiment 2). The time-dependent changes could be abolished by conditioning elbow flexors and extensors in the reference arm at the test angle, although this led to large position errors during matching (±10°), depending on how the indicator arm had been conditioned (Experiments 3 and 4). When slack was introduced in the elbow muscles of both arms, by shortening muscles after the conditioning contraction, matching errors became small and there was no drift in position sense (Experiments 5 and 6). These experiments argue for a receptor-based mechanism for proprioceptive drift and suggest that to align the two forearms, the brain monitors the difference between the afferent signals from the two arms.

Key points

When a blindfolded subject holds his or her arm at a particular angle, its reported position shifts over time; this is known as proprioceptive drift.

Here, we show that in relation to position sense at the elbow, the direction of perceived shifts is consistent with adaptation in discharge levels of sensory receptors in elbow muscles.

Raising or lowering receptor discharge levels by similar amounts in opposing muscles at the elbow using muscle conditioning abolishes proprioceptive drift, but large position errors may result.

The present experiments provide an explanation for proprioceptive drift and indicate that, in a forearm position-matching task, the brain is not concerned with actual discharge levels from arm muscles, but with their difference.

Introduction

It is now generally accepted that muscle spindles are the principal proprioceptors concerned with the senses of limb position and movement, and that skin receptors play a minor contributory role (Proske & Gandevia, 2012). With reference to muscle spindles, including both the primary and secondary endings (McCloskey, 1973), it is believed that when a muscle is stretched, the maintained increase in discharge rate is interpreted by the brain as a longer muscle, and thus a more flexed or extended joint. An interesting point made by Matthews (1988) is that for most sensory receptors an increase in discharge rate is perceived as an increase in stimulus intensity; in muscle spindles it implies an increase in muscle length.

It is a common experience that when we touch an object and maintain contact with it for a period of time, the touch sensation gradually fades as a result of adaptation processes, including receptor adaptation. Muscle spindles also exhibit receptor adaptation. The adaptation mechanisms may be both mechanical and ionic in origin (Matthews, 1972, p270). Whereas adaptation in other sensory receptors results in the perception of a weaker stimulus, in muscle spindles, based on the considerations outlined above, it can be interpreted as the muscle becoming shorter. Thus, the adaptation of spindle discharge in elbow flexor muscles would be perceived as indicating a more flexed elbow and that in elbow extensors would be perceived as indicating a more extended elbow. This point is the subject of the present study.

When a limb is held steady in a particular posture for a period, the change in its perceived position over time, in the absence of vision, is referred to as ‘proprioceptive drift’ (Wann & Ibrahim, 1992; Desmurget et al. 2000; Brown et al. 2003). In a simple position-matching experiment (Paillard & Brouchon, 1968), subjects were required to move a vertical slide with one hand to match the position of the other hand. If a delay between the placement of the reference hand and the matching of its position by the other hand was introduced, time-dependent errors emerged in the form of proprioceptive drift. Wann & Ibrahim (1992) considered the possibility that proprioceptive drift was a consequence of the slowly adapting properties of limb proprioceptors, but rejected this explanation on the grounds that vision and proprioception were only partially effective in resetting the perceived limb position. Desmurget et al. (2000) claimed that in the search for an explanation of proprioceptive drift two factors had been overlooked: the influence of motor outflow, and the ability to memorize position. When the reference hand was moved to its position, at zero delay it had available not only a static proprioceptive signal, but also information related to the magnitude of the performed displacement. This latter cue would be expected to fade, leading to the perceived proprioceptive drift. In support of their view, Desmurget et al. (2000) showed that, in the absence of vision, if one hand was moved to a target position following an indirect, randomly varying movement, the accuracy of the localization of its position by the other hand was unaltered over a measurement period of 20 s. Thus, this study suggested that proprioceptive drift was a consequence of a fading memory of the initial displacement.

More recently, Brown et al. (2003) asked subjects to carry out a series of repetitive movements without vision. The starting location was observed to visibly drift with time, but movement distance and direction remained unaffected. These authors concluded that after a prolonged period without vision, proprioceptive information was used differently by separate position and movement controllers. Drift occurred because the two controllers were differentially sensitive to small position errors. The movement controller tracked intrinsic limb posture (from a body map), whereas the position controller tracked extrinsic hand location.

The term ‘proprioceptive drift’ has also been used in relation to the rubber hand illusion (Botvinick & Cohen, 1998). By using touch in combination with vision, a rubber hand can be successfully incorporated into one's own body representation. The accompanying relocation of the felt position of the unseen hand towards the rubber hand has been referred to as proprioceptive drift (Kammers et al. 2009). In the present study, we restrict the meaning of the term to perceived changes in the position of a limb over time which, we propose, result from alterations in afferent activity in muscles acting at the joint under study. An illusory change in the ownership of a body part, generated by a sensory conflict situation, is something quite different and presumably operates entirely centrally.

In summary, none of the studies referred to above suggest that proprioceptive drift is a direct consequence of a declining afferent discharge by muscle proprioceptors. In the present study, we provide evidence that a component of proprioceptive drift can be attributed to receptor adaptation. The supporting evidence is derived from the finding that, at a given limb position, the direction of drift can be manipulated and can be changed according to how the muscles acting at the joint have been conditioned.

The present study is concerned with position sense at the elbow. Position sense is defined here as the ability to perceive the position of a limb in the absence of vision. Position sense at the elbow is signalled predominantly by afferents of muscle spindles in elbow flexors and extensors (Goodwin et al. 1972). It is believed that the level of background activity in spindles provides the positional signal (Clark et al. 1985). Position sense can be measured in a forearm-matching task, in which the experimenter places one arm of the subject at a predetermined angle and the blindfolded subject is required to match its position with his or her other arm. It is the muscle undergoing stretch during placement of the reference arm at the test angle that provides the positional information used to match its position (Gilhodes et al. 1986; Ribot-Ciscar & Roll, 1998). Because the evidence in this task suggests that afferent activity from both arms contributes to the perceived position of the reference arm (Lackner, 1984; Lackner & Taublieb, 1984; Allen et al. 2007; White & Proske, 2009; Izumizaki et al. 2010), some experimenters prefer to measure position sense only in one arm and thus require the subject to indicate the position of the hidden arm with a pointer (Walsh et al. 2013). Here, we have chosen a two-arm matching task to measure position sense. We have done so because matching and pointing tasks do not measure exactly the same thing and we wanted to relate findings from the present study to previous observations made using a matching task.

In the present work, we used the technique of conditioning forearm muscles with contractions and length changes to systematically alter their afferent activity. The technique relies on a property of muscle called ‘thixotropy’, a contraction history-dependent, passive stiffness (Lakie et al. 1984). Changing the thixotropic state of elbow muscles by conditioning alters the responses of muscle spindles and therefore can alter position sense at the forearm (Gregory et al. 1988).

Muscle thixotropy is a consequence of longterm stable cross-bridges (Hill, 1968) between the myofilaments of both extrafusal and intrafusal muscle fibres (Proske et al. 1993). When a muscle is conditioned with a voluntary contraction at a particular length, fusimotor neurones are coactivated together with skeletomotor neurones (Vallbo, 1971, 1974), leading intrafusal fibres to contract. At the end of the contraction, stable cross-bridges will form, leaving the intrafusal fibres taut and imposing their resting tension on the spindle sensory ending. As a result, spindle background discharge rises and spindles become stretch-sensitive. If an intrafusal contraction takes place in a stretched muscle and the muscle is then shortened, the stiffness imposed on the intrafusal fibres by their stable cross-bridges prevents them from shortening as well and they fall slack. Slack spindles have low resting discharge rates and low sensitivities to movements (Proske et al. 1992; Scott et al. 1994). Thus the ability to manipulate spindle responsiveness between two extremes, a sensitized state and a state of low sensitivity, can be used as a tool in the study of position sense. Although the thixotropic behaviour of muscle spindles has been studied largely in animal experiments (Proske et al. 1993), there is evidence from human spindles (Jahnke et al. 1989; Burke & Gandevia, 1995; Wilson et al. 1995) consistent with such behaviour.

In recent experiments concerned with the effects of exercise on forearm position sense (Tsay et al. 2012), we observed position errors in control measurements before the exercise had started, despite the fact that both arms had been conditioned identically. At the time we suspected that the time delay between the placement of the reference arm and the matching of its position was responsible and thus that the errors were caused by receptor adaptation in proprioceptors of the reference arm. In the present study, we put this idea to the test.

We hypothesized that at least one component of proprioceptive drift is caused by adaptation of receptor discharge. By adaptation, we mean the progressive slowing of muscle spindle discharge following a conditioning contraction used to remove any pre-existing slack in muscle and its spindles. Without the contraction, because of the presence of slack, spindle discharge levels are too low for significant adaptation to take place. We propose that these adaptive changes occur at the level of background discharge, signalling limb position, and do not reflect the signal generated by the movement from the conditioning length to the test length. Finally, by combining a conditioning contraction with a stretch, we deliberately introduced slack in spindles to lower their background discharge.

Methods

A total of six experiments were carried out. Experiments 1 and 2 used 12 subjects; the other experiments each used nine subjects. One cohort of subjects participated in both Experiments 1 and 2, and another participated in both Experiments 5 and 6. This made for a total of 39 subjects, of whom 22 were male and 17 were female. The mean ± s.e.m. age of the subjects was 24.5 ± 1.3 years. Subjects gave informed written consent prior to participating in an experiment. The work was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. The ethical aspects of the experiments conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki.

All position matching was performed in the vertical plane. Blindfolded subjects sat at a table and placed both forearms on the lightweight paddles of a custom-built apparatus for measuring forearm position sense (Allen & Proske, 2006). The forearms were strapped to the paddles by Velcro straps of 5 cm in width placed just below the crease of the wrist with the palms facing upward. The tension of the strapping was verified as equal before the experiment was started in order to minimize potential differences in skin sensation between the two arms. The upper arms rested on horizontal supports, which allowed subjects to relax their shoulder muscles during matching trials. One arm was designated the reference arm (the arm placed at the target angle by the experimenter) and the other was the indicator arm (the arm moved by the subject to match the position of the reference arm).

Forearm angle was measured using potentiometers (25 kΩ; Spectra Symbol Corp., Salt Lake City, UT, USA) located at the hinges of each paddle. The hinges were co-linear with the elbow joint. The potentiometers provided a continuous voltage output proportional to the angle of each paddle, in which a reading of 0° referred to the forearm in a horizontal position and a reading of 90° referred to it in a vertical position. The calibration of the potentiometers was checked before each experiment.

Muscle activity in the reference arm was measured using surface electromyography (EMG). A pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes with an adhesive base and solid gel contact points (3M Health Care, London, ON, Canada) were placed approximately 2.5 cm apart over the surface of the biceps brachii and triceps brachii. A grounding electrode was placed on the collar bone. EMG output was connected to an audio amplifier for biofeedback. Position signals were acquired at 20 Hz and EMG signals at 1000 Hz using a MacLab 4/s data acquisition module running Chart software (ADInstruments Pty Ltd, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia) on a Macintosh computer.

Position errors between the two arms were calculated using the formula:

According to the convention used, when the indicator arm was placed in a more extended position than the reference arm, errors were given a positive value. When the indicator arm was placed in a more flexed position, errors were assigned a negative value.

Of the 39 subjects, 32 were right-handed. Reference and indicator arms were randomly assigned to reduce any biases caused by matching with a dominant or non-dominant arm (Goble et al. 2006). The reference arm was the dominant arm in 18 subjects and the non-dominant arm in 21 subjects. During a trial the paddle strapped to the reference arm was moved by the experimenter to the test angle and the blindfolded subject was asked to match its perceived position with his or her indicator arm. The test angle chosen was approximately 45°. The actual angle achieved in each trial depended on placement by the experimenter and ranged from 40° to 50°. The variation in target angle from trial to trial meant that the subject was unable to use timing or movement cues to guess the actual test angle. During the movement of the reference arm to the test angle, subjects were asked to remain relaxed. This was monitored using auditory feedback of EMG in the reference arm. In each experimental trial, conditions were randomized.

Throughout these experiments, once the reference arm had been placed at the test angle, its position was maintained by the subject voluntarily. All matching with the indicator arm was also performed voluntarily by the subject. Subjects were therefore required to generate mild contractions sufficient to support the arms against gravity and to move the indicator arm into the matching position. These conditions were chosen to keep the matching process close to the type of activity the subjects might carry out in everyday life. During the matching process, subjects were asked not to rush and to move the indicator arm into position carefully and deliberately. Once the reference arm was in position at the test angle, moving the indicator from its starting position into the matching position took about 5 s. At the end of each trial the arms were brought back to their resting positions one at a time in order to make it difficult for subjects to obtain cues about the test angle from the time it took to return the arms to their initial positions.

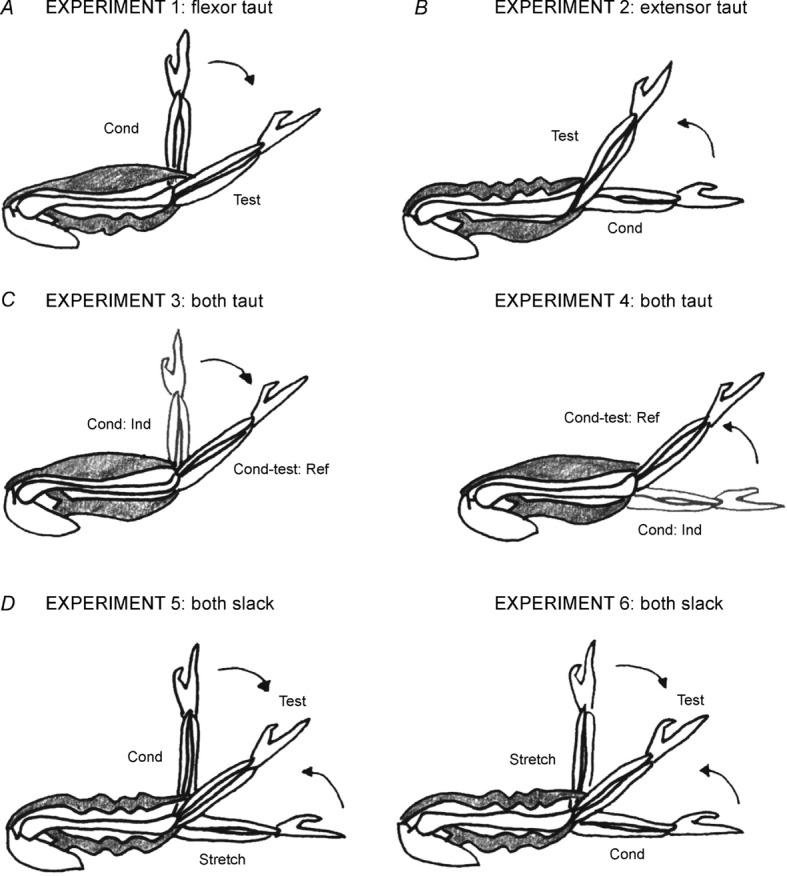

Muscle conditioning

It was necessary at the start of each position-matching trial to put the elbow muscles of both the reference and indicator arms into a defined thixotropic state. This is called muscle conditioning. Typically the muscle is conditioned with a half-maximum voluntary contraction (Gregory et al. 1998). In Experiment 1, elbow flexors in both arms were contracted with the arms held flexed. Flexion conditioning altered the mechanical state of elbow flexors in both arms, leaving them taut and leaving elbow extensors slack during the matches (flexor taut, Fig. 1A). In Experiment 2, elbow extensors in both arms were contracted with the arms held extended; this is extension conditioning. Here, during matching the elbow flexors in both arms lay slack and the extensors were taut (extensor taut, Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Mechanical state of elbow muscles after conditioning.

All conditioning of arm muscles and subsequent position matching was performed in the vertical plane. A, in the flexor taut condition, elbow flexors were contracted with the arm held at 90°. After the contraction, subjects were asked to relax while the arm was moved by the experimenter into extension to the test angle (40–50°). In the process elbow flexors were stretched, leaving them taut, and elbow extensors were shortened, leaving them slack. The slack state is indicated by the rippling. The direction of movement of the arm to the test angle is indicated by the arrow. B, in the extensor taut condition, elbow extensors were contracted with the arm held at 0°. After the contraction the relaxed arm was moved by the experimenter into flexion to the test angle. In the process elbow extensors were stretched, leaving them taut, and elbow flexors were shortened, leaving them slack. The direction of movement to the test angle is shown by the arrow. C, in the both taut condition, the arm was moved to the test angle and held fixed in position while elbow flexors and then elbow extensors underwent conditioning isometric contractions (Experiment 3). The contractions removed any pre-existing slack in both muscle groups. The conditioning was repeated, but beginning with an extension contraction (Experiment 4). The position of the indicator arm during the conditioning contraction is shown in grey. D, in the both slack condition, for Experiment 5, after contraction of flexors at 90°, the arm was moved into extension (arrow), stretching flexors, shortening and slackening extensor muscles. Once the arm was fully extended, (0°), it was held there for 6 s before being moved into flexion to the test angle (arrow). The movement shortened and therefore slackened flexors so that both flexors and extensors were slack. The same result could be achieved by beginning with an extensor contraction at 0° and moving the arm to 90° for 6 s before placing it at the test angle (Experiment 6).

In Experiments 3 and 4, we wanted to measure position sense under conditions in which the proprioceptive bias imposed on the reference arm by flexion conditioning (Experiment 1) or extension conditioning (Experiment 2) was no longer present. In order to do this, the reference arm was conditioned in a way that left both elbow flexors and extensors in a sensitized state during matching (both taut, Fig. 1C). Conditioning used isometric contractions of elbow flexors and extensors at the test angle. Any adaptation in one antagonist would be offset by similar adaptation in the opposite direction in the other and therefore the signal difference from them would not be expected to change with time.

In Experiments 5 and 6, we wanted to measure position sense under conditions in which the sensitivity of muscle receptors in both reference and indicator muscles had been reduced by conditioning (both slack, Fig. 1D). To desensitize proprioceptors in a muscle, the muscle must be stretched and held at the stretched length for several seconds to allow stable cross-bridges to reassemble at that length (Morgan et al. 1984). If the muscle is then shortened, the muscle fibres, stiffened by the presence of the stable bridges, will fall slack, rather than shorten. A slack intrafusal fibre does not exert any tension on the sensory ending of the spindle and thus both spindle resting activity and stretch responsiveness are reduced.

Experiments 1 and 2: time-dependent changes in position sense after flexion or extension conditioning in both arms

Position sense was measured using four lengths of delay (1 s, 5 s, 10 s and 30 s) between the placement of the reference arm at the test angle and the matching of its position by the indicator. Subjects carried out six trials at each interval of delay. For each subject, the order of the trial conditions (i.e. the delay intervals) was randomized from trial to trial. For trials involving a time delay of 1 s, subjects were asked to begin moving the indicator arm into a matching position as soon as they felt the experimenter starting to move the reference arm from its conditioning position towards the test angle. About 1 s elapsed between the placement of the reference arm at the test angle and the subject's matching of its position with the indicator arm. In the 5 s delay condition, subjects were asked not to move the indicator arm until the reference arm had been placed at the test angle. Moving the indicator arm from its starting position to the matching position and declaring a match took 5 s. In the 10 s delay condition, subjects were asked to wait for 5 s before moving the indicator arm into the matching position. In the 30 s delay condition, subjects were asked to wait for 25 s before moving the indicator arm.

In Experiment 1 flexion conditioning was used. Here, both arms were moved to 90°, the paddles locked in position and the subject was asked to generate a 2 s, approximately half-maximum, isometric contraction with the elbow flexors by attempting to flex the elbows towards the body. The conditioning procedure took about 5 s. Once the arms had relaxed, the metal struts were removed and the reference arm was immediately moved into extension to the test angle (40–50°). The blindfolded subject then matched its position with his or her indicator arm. In Experiment 2, both arms were moved into full extension (0°) and the subject was asked to push the arms down on the supports to generate a half-maximum contraction in the elbow extensors. Once the subject had relaxed, the reference arm was moved in the direction of flexion to the test angle and its position was matched.

Experiments 3 and 4: time-dependent changes in position sense after co-contraction of reference muscles

In Experiment 3, the blindfolded subject's reference arm was moved to the test angle (45° from the horizontal). The subject was asked to generate a half-maximum contraction in extensor muscles by pushing the arm away from the body. During the contraction the arm was rigidly fixed at the test angle by a pair of metal struts bolted to the frame of the apparatus. The subject was then asked to generate a half-maximum flexion contraction, the arm again being held fixed at the test angle. Thus, the reference arm had now undergone isometric flexion and extension contractions at the test angle, leaving spindles in both muscle groups in a sensitized state. The indicator, by contrast, had only been flexion-conditioned before the subject moved it into a matching position. The nature of the matching procedure did not make it possible to condition indicator muscles at the test angle.

In Experiment 4, the same procedure was repeated, but this time the subject was asked to begin with an isometric flexion contraction of the reference arm, followed by an isometric extension contraction. After arm muscles had relaxed, the extension-conditioned indicator arm was moved into a matching position.

In both Experiments 3 and 4, after the conditioning procedure had been completed, position sense was measured at three intervals of delay (5 s, 10 s and 30 s). It was not possible to include a 1 s delay as the conditioning took several seconds to complete. Subjects carried out a series of six trials at each delay interval.

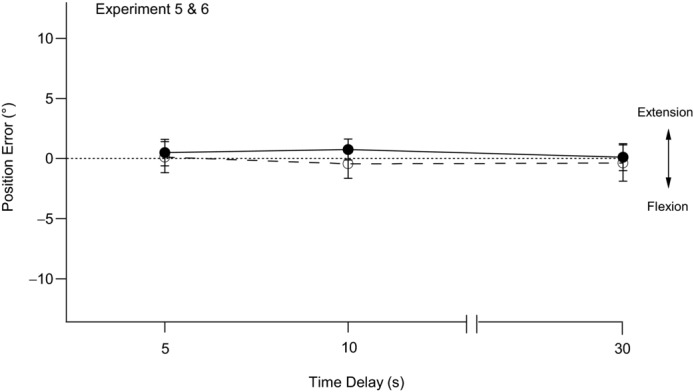

Experiments 5 and 6: time-dependent changes in position sense after stretching of reference and indicator elbow muscles

To desensitize muscle receptors, in Experiment 5 both arms of the blindfolded subject were initially flexion-conditioned, as before, by holding them at 90° and contracting them isometrically in the direction of flexion using a half-maximum contraction. The contraction removed any pre-existing slack in elbow flexors in both arms. At 90° the elbow extensors were stretched; stable cross-bridges in extensor muscles would be expected to form at that stretched length. After the flexor contraction, both arms were moved into full extension (0°). In the process, the flexors were now stretched to a long length and the extensors were shortened. The arm was held at 0° for 6 s to allow cross-bridges in flexors that had been detached by the stretch to reassemble at the longer length (Morgan et al. 1984). We believe there was no comparable reassemblage of cross-bridges in the extensors because their bridges had formed at 90° and the shortening movement to 0° simply meant that they fell slack. The experimenter then moved the reference arm from 0°, in the direction of flexion, to the test angle, and the subject moved the indicator arm into flexion to a matching position. In the process, elbow flexor muscles in both arms were shortened and fell slack. The movement into flexion represented a stretch from 0° to 40–50°, which, we believe, was too small a stretch of extensor muscles to reset their cross-bridges as these had formed at 90°. All the stretch did was to take up some, but not all, of the slack in the extensors. If there is any slack at all in a muscle, spindle background rates will remain low. Thus, now both flexor and extensor spindle rates in both arms were low because the muscles lay slack.

The conditioning procedure for Experiment 6 was essentially the same, except that it began with the contraction of elbow extensors in both arms while the arms were held extended (0°). Then both arms were flexed to 90° and held there for 6 s before the reference arm was extended to 40–50° and the indicator arm was moved into a matching position.

In both Experiments 5 and 6, after the conditioning procedure had been completed, position sense was measured at three intervals of delay (5 s, 10 s and 30 s). A shortest delay of 5 s rather than of 1 s was chosen to allow for a direct comparison between these data and data from Experiments 3 and 4. Subjects carried out a series of six trials at each delay interval.

Statistical analysis

A repeated-measures ANOVA was used to test for the effects of time delay on position errors. If significance was found, a post hoc least significant differences (LSD) test was used to determine which of the matching trial types were significantly different from one another. Pooled data from each group of experiments are shown as means ± s.e.m.

Results

Time-dependent changes in position sense after flexion or extension conditioning of both arms

The aims of these experiments were to confirm the suggestion that when an arm sits at a test angle for a period of time, time-dependent changes in position sense occur (Paillard & Brouchon, 1968; Wann & Ibrahim, 1992) and to test the hypothesis that the direction of these changes is consistent with adaptation of the discharge of muscle spindles.

Experiment 1: conditioning reference elbow flexors

In the first experiment, time-dependent changes in position sense were studied after both arms were flexion-conditioned with the arms held at 90°. As soon as the subject had relaxed, the reference arm was moved to the test angle (40–50°) by the experimenter and the subject followed the movement with the indicator arm to adopt a matching position as soon as the reference arm had stopped moving. This was the 1 s delay condition. In the 5 s, 10 s and 30 s delays, the movement of the indicator arm was delayed.

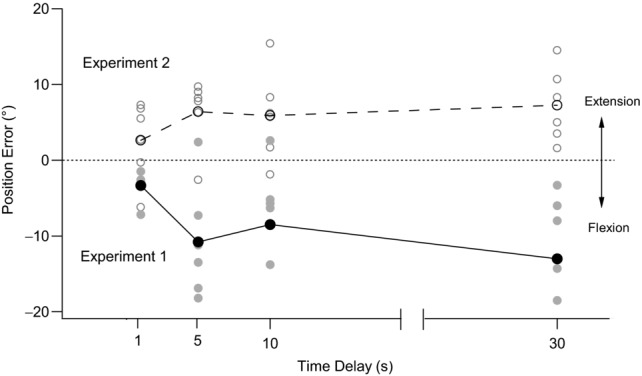

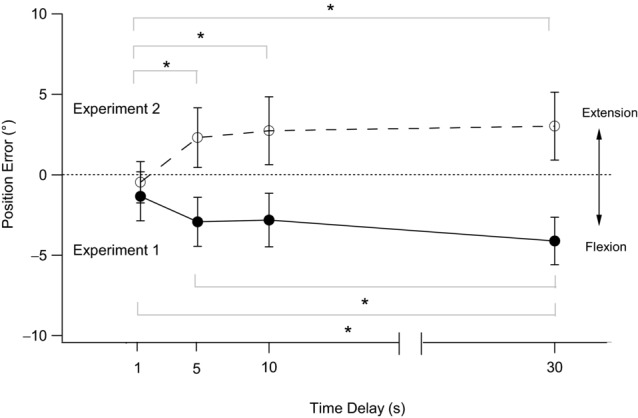

Data for a single subject are shown in Fig. 2 (filled circles). With a 1 s delay between the placement of the reference arm and the matching of its position, the single subject made an error of −3.4° When a delay of 5 s was introduced between the placement of the reference arm and the matching of its position, the subject made an error of −10.8°. This error reduced to −8.5° at 10 s and increased further to −13.0° at 30 s. This trend in the single subject was reflected in pooled data from 12 subjects (Fig. 3). With a 1 s delay, the mean ± s.e.m. error was −1.3 ± 1.5°. The error into flexion increased to −2.9 ± 1.5° with a 5 s delay, was −2.8 ± 1.7° with a 10 s delay and increased to −4.1 ± 1.5° with a 30 s delay. A repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of time delay (F(3,33) = 3.1, P < 0.05). A post hoc LSD test showed a significant difference in outcomes between the 1 s and 30 s delays, as well as between the 5 s and 30 s delays. Therefore, systematic changes with time occurred in the perceived position of the reference arm. The errors increased in the direction of elbow flexion, consistent with previous reports (Wann & Ibrahim, 1992). In other words, over time, subjects believed that their reference arm was in a progressively more flexed position than it really was.

Figure 2. Single-subject data for changes with time in position errors at the elbow joint after flexion or extension conditioning of elbow muscles.

The filled circles and continuous line show mean position errors after flexion conditioning. The open circles and dashed line show mean position errors after extension conditioning. Grey symbols show individual matching trials. At the start of each flexion conditioning trial the elbow flexors of both arms were contracted with the arms held flexed (90°). The reference arm was then moved into extension to the test angle and its position matched by the indicator arm, immediately (1 s), and after 5 s, 10 s and 30 s (Experiment 1). In extension conditioning trials, elbow extensors of both arms were contracted with the arm held extended (0°) and the position of the reference arm was then matched at the test angle by the indicator arm at the same four time delays as in flexion conditioning (Experiment 2). Position errors are plotted against time. Errors into flexion are shown as negative and errors into extension as positive. Dotted line indicates zero error.

Figure 3. Pooled data for changes with time in position errors at the elbow joint after flexion or extension conditioning of elbow muscles.

Data refer to 12 subjects. The filled circles and continuous line show position errors after flexion conditioning. The open circles and dashed line show position errors after extension conditioning. Position errors are plotted against time. Errors into flexion are shown as negative and errors into extension as positive. Data are means ± s.e.m. *Significant differences between bracketed values (P < 0.05). Dotted line indicates zero error.

Experiment 2: conditioning reference elbow extensors

The working hypothesis for Experiment 1 was that conditioning of elbow flexors with the arms held flexed (flexor taut, Fig. 1A) led to time-dependent changes in matching errors in the direction of flexion as a result of adaptation processes in the discharges of the reference flexor spindles. To test the adaptation hypothesis, we repeated the experiment, but raised discharges in the spindles of extensor muscles (extensor taut, Fig. 1B). Adaptation of discharge in elbow extensors should lead to time-dependent changes in matching errors in the direction of extension.

Figure 2 shows data for extension conditioning (open circles) in the same single subject previously tested with flexion conditioning. The trends in position error after the two forms of conditioning clearly lie in opposite directions. In extension conditioning, when the indicator was matched as soon as the reference had reached its test angle (the 1 s delay condition), the single subject matched with a mean error of +2.6°. After a 5 s delay between placement and matching, the error increased to +6.4°. When the delay was increased to 10 s, the error decreased slightly to +5.9°, but then increased further to +7.3° with a delay of 30 s. Similar trends were apparent in the pooled data. With a 1 s delay, the mean error was −0.5 ± 1.3°. The mean error increased to +2.3 ± 1.9° with a 5 s delay, to +2.7 ± 2.1° with a 10 s delay and to 3.0 ± 2.1° with a 30 s delay. A repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of time delay (F(3,33) = 6.7, P < 0.05). A post hoc LSD test showed a significant difference between the 1 s and all other time delays.

These two sets of observations provide experimental support for the hypothesis that when conditioning is restricted to a single muscle group, be it elbow flexors or extensors, time-dependent errors in position sense occur in a direction consistent with adaptation of the discharge in the conditioned muscles.

Time-dependent changes in position sense after co-contraction of reference antagonists

In this experiment, the aim was to condition reference muscles in such a way that both flexor and extensor spindles were left in a sensitized state (both taut, Fig. 1C). We would expect adaptation to occur over time in spindles of both antagonists. If spindle adaptation followed a similar time course, the fall in reference flexor spindle discharges, leading the arm to be perceived as becoming more flexed, would be offset by the fall in reference extensor discharges, leading the arm to be perceived as more extended. Thus, the hypothesis for this experiment was that there would be no time-dependent changes in position sense.

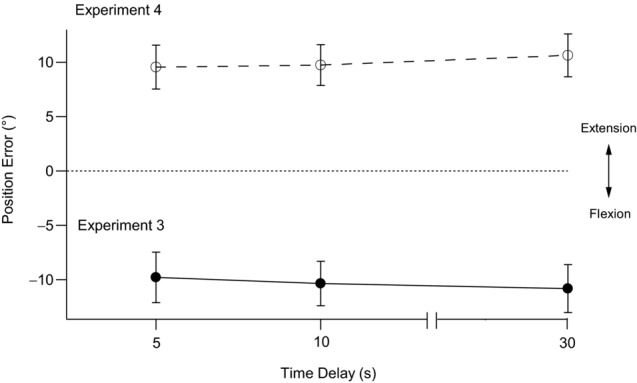

Experiment 3: flexion conditioning of the indicator arm

In this experiment, carried out in nine subjects, both flexors and extensors of the reference arm were contracted at the test angle. At the same time, the indicator arm was flexion-conditioned. In these experiments, because the reference arm had to be conditioned before the indicator, it was not possible to have a 1 s delay and the shortest matching interval was 5 s.

Pooled data are shown in the lower panel of Fig. 4. When the delay between the placement of the reference arm and the matching of its position was 5 s, subjects matched the position of the reference arm by placing the indicator arm at −9.8 ± 2.3°. In other words, subjects thought their reference arm was more flexed than it really was by nearly 10°. When a 10 s delay was introduced, the matching error increased slightly to −10.3 ± 2.0°. With a 30 s delay, the error was −10.8 ± 2.2°. These differences in error were small and not significant. The errors at all time delays were significantly different from zero error (P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Position errors after isometric contractions of reference flexors and extensors at the test angle.

The reference arm was moved to the test angle and held there, fixed in position. The filled circles and continuous line show pooled means ± s.e.m. of position errors for nine subjects after the reference arm had undergone an isometric extensor contraction followed by an isometric flexor contraction while elbow flexors of the indicator arm were contracted with the arm held flexed (90°). The indicator arm was then moved to match the perceived position of the reference arm at 5 s, 10 s and 30 s after the reference had reached the test position (Experiment 3). The open circles and dashed line show the pooled means ± s.e.m. of position errors for nine subjects after the reference had undergone an isometric flexor contraction and then an isometric extensor contraction while indicator extensors were contracted with the arm held extended (0°). The indicator arm then matched the perceived position of the reference arm after delays of 5 s, 10 s and 30 s (Experiment 4). The dotted line indicates zero error. Errors into flexion are shown as negative and errors into extension as positive.

Experiment 4: extension conditioning of the indicator arm

Here, the conditions of Experiment 3 were repeated, but, following the co-conditioning of reference elbow muscles at the test angle, the indicator arm was extension-conditioned. The pooled data for the nine subjects are shown in the upper panel of Fig. 4. With a 5 s delay between conditioning and matching, the mean error in position was +9.6 ± 2.0°. That is, subjects felt their arm positions were accurately aligned, when in fact the indicator was nearly 10° more extended than the reference arm. The error increased slightly to 9.8 ± 1.9° with a 10 s interval and 10.6 ± 2.0° with a 30 s interval. These differences in error with time were small and not significant. The errors at all time delays were significantly different from zero error (P < 0.05).

The results of Experiments 3 and 4 support our working hypothesis in that after co-conditioning of reference muscles there was no longer any evidence for a shift in the perceived position of the arm with time because the influences from the two antagonists impacted in opposite directions and so annulled one another. The presence of large bias errors, in the direction of flexion or extension, was interpreted as attributable to the indicator arm, in which the elbow muscles had been conditioned to generate a strong flexor or extensor signal.

Time-dependent changes in position sense after stretch of elbow muscles

The question of why initial bias errors occurred during a normal matching trial remained. For example, why was there an error of −2.3° with a 1 s delay in Experiment 1? Given that the two arms had been conditioned identically, why did average matching errors not fall to zero? Our proposed explanation is that once the conditioned reference arm had been placed at the test angle, its spindles were likely to maintain a level of background activity proportional to the length of the muscle at that angle. However, during the movement of the indicator arm to the matching position, its spindles would respond to both the length change and the rate of length change, which would raise their discharge rates well above those in the reference muscles. Therefore, the indicator arm was perceived as more extended than the reference arm. As a result, the subject stopped moving the indicator arm before he or she achieved an accurate match. The same argument can be applied to extension conditioning, but here the errors would occur in the opposite direction.

To test this idea, we tried to lower spindle discharge rates in flexors and extensors in both arms using conditioning techniques. If spindle rates could be lowered, any difference between the static signal from the reference arm and the static plus dynamic signal from the indicator arm would be smaller and should therefore lead to smaller bias errors. In order to achieve lower rates, attempts were made to introduce slack into elbow muscles in both arms (both slack, Fig. 1D).

Experiment 5: introducing slack after flexion conditioning

The experiment was begun with flexion conditioning of both arms. After subjects had relaxed, both arms were moved by the experimenter to full extension (0°) and held there for 6 s. Then the reference arm was moved to the test angle (40–50°) and its position was matched by the indicator arm.

Data for a group of nine subjects using flexion conditioning are shown in Fig. 5. At 5 s after the reference arm had been placed at the test angle, its position was matched by the indicator arm with a mean error of +0.5 ± 1.1° in the direction of extension. The error at 10 s was +0.8 ± 0.9° and that at 30 s was +0.1 ± 1.1°. Mean errors therefore lay close to zero and statistical analysis showed no significant effect of time delay on position error. Therefore, there was no evidence of adaptation over the 30 s of measurement. In addition, the errors at all time delays did not differ significantly from zero error.

Figure 5. Position errors after conditioning to introduce slack in both reference and indicator muscles.

The filled circles and continuous line show pooled means ± s.e.m. of position errors in nine subjects after elbow flexors of both arms had first undergone contractions with the arms held flexed (90°). Both arms were then moved into full extension (0°) and held there for 6 s before the reference arm was moved to the test position and its position matched by the indicator arm. Matching was performed at 5 s, 10 s and 30 s after the reference arm had reached the test angle (Experiment 5). The open circles and dashed line show pooled means ± s.e.m. of position errors of nine subjects after elbow extensors of both arms had first undergone contractions with the arms held extended (0°). Both arms were then moved into full flexion (90°) and held there for 6 s before the reference arm was moved to the test angle and its position matched by the indicator arm after delays of 5 s, 10 s and 30 s (Experiment 6). The dotted line indicates zero error. Errors into flexion are shown as negative and errors into extension as positive.

Experiment 6: introducing slack after extension conditioning

This time, the experiment began with extension conditioning of both arms at 0°. After subjects had relaxed, both arms were moved to 90° and held there for 6 s before the reference arm was extended to the test angle (40–50°) and its position matched by the indicator arm. Mean values for the nine subjects are shown in Fig. 5.

When the placement of the reference arm was matched by the indicator arm after a delay of 5 s, an error of 0.1 ± 1.3° into extension occurred. This error increased to +0.4 ± 1.2° at 10 s and −0.4 ± 1.5° at 30 s. Again, statistical analysis showed no significant effect of time delay on position error and there was no evidence of adaptation over the 30 s. Furthermore, none of the errors differed significantly from zero error.

In Experiments 5 and 6, although mean errors from the pooled data lay close to zero, individual subjects showed degrees of variability in performance from trial to trial similar to those seen in the other experiments. There was no suggestion that the conditions of these experiments had altered inter-trial variability. Furthermore, conditioning eliminated any directional bias in the placement of the indicator, allowing pooled means to lie close to zero.

Discussion

The findings of this study contribute two new observations to the study of limb position sense in human subjects. They provide evidence in support of the view that receptor adaptation is responsible, at least in part, for time-dependent errors in position sense, referred to previously as proprioceptive drift. Secondly, they confirm reports that position sense derives from a difference in signals from proprioceptors of the two antagonists acting at the elbow joint. We extend this concept to include signals from both arms. Our data are consistent with the view that for position sense at the forearm, the difference in signals from the two arms is computed and that when this reaches a minimum value, the arms are assumed to be aligned.

In all the present experiments, subjects held their reference arms at the test angle, unsupported. We do not believe that the motor commands and muscle contraction required to hold the arm in place were responsible for any position errors in their own right. Our previous work (Ansems et al. 2006; Allen et al. 2010; Walsh et al. 2013) has shown that position errors measured in a relaxed supported arm do not differ significantly from errors measured when arm muscles contract to support a load. Furthermore, it could be argued that in situations in which the muscle and its spindles were meant to lie slack, the contractions required to hold the reference arm and to move the indicator arm into a matching position risked removing the slack. The elbow flexor torque required to hold an arm at 45° has been estimated at 5% of maximum (Winter et al. 2005). Contractions of that strength are insufficient to reset the muscle's conditioned state (Gregory et al. 1998).

The present experiments are based on the thixotropic behaviour of muscle spindles. Although our interpretations are consistent with observations made in human spindles (Jahnke et al. 1989; Burke & Gandevia, 1995; Wilson et al. 1995) and animal spindles (Morgan et al. 1984; Gregory et al. 1988), the approach is, by necessity, indirect, although the consistency of the findings and their predictability, based on theory, support our view.

Time-dependent changes in position sense after flexion or extension conditioning of both arms (Experiments 1 and 2)

These experiments were based on the hypothesis that the time-dependent changes in position sense previously reported (Paillard & Brouchon, 1968; Wann & Ibrahim, 1992; Brown et al. 2003) resulted from adaptation processes at the level of muscle receptors. It was proposed that by conditioning a muscle with a contraction, high levels of resting discharge would be generated in spindles and discharge rates would fall over time as a result of adaptation. Indeed, time-dependent changes in position sense did occur and the direction of the changes depended on which muscle group had been conditioned (Figs 2 and 3). Such a directional change in the distribution of the errors argues in support of a peripheral signal for the origin of proprioceptive drift and makes an explanation based entirely on central mechanisms less likely.

Evidence for adaptation was sought over four periods of delay. It could be argued that in the first condition, of 1 s interval measurements, subjects were carrying out not a position-matching task, but a movement-tracking task. This raises the possibility that the subsequent time-dependent changes in position errors did not reflect receptor adaptation but the fading effects of a tracking task. The difficulty with such an interpretation is that it is not easy to distinguish between changes caused by adaptation and those of a movement-tracking task. The interval most likely to be influenced by the preceding movement is the 1 s interval. If this is excluded from the analysis of the time-dependent changes in error, the result is no longer significant. Such an outcome is not surprising because during the time course of adaptation of a typical spindle discharge, most of the changes occur within the first second after a stretch [Fig. 5B in Roll & Vedel (1982)].

In Fig. 3, notice that after flexion conditioning errors differ significantly between the 1 s and 30 s delays, as well as between the 5 s and 30 s delays. Significant changes in error beyond the 1 s interval support our case for receptor adaptation. The same is not true in extension conditioning, in which the change in errors between the 5 s and 30 s intervals is not significant. This may be because after extension conditioning subjects were required to hold their arms at the test angle and this may have removed some slack in elbow flexors and thus reduced the difference in signals from flexors and extensors.

Perusal of the literature has not revealed any examples of time-dependent changes in position errors following a limb-tracking task. It has been reported that when movement of one arm is suddenly stopped, the distance it has moved is overestimated in the placement of the other arm (Hollingworth, 1909). However, in the present experiments, errors in the opposite direction occurred. After flexion conditioning, when the movement of the reference arm into extension was stopped, it led to matching errors into flexion (Fig. 2).

In Experiment 1, it was postulated that when the reference arm was moved to the test angle, the conditioned elbow flexors were stretched by the movement, generating a high level of spindle discharge. The same movement would shorten the extensors, which would fall slack. We assumed that the high rate of discharge in flexors would adapt with time, leading to the perception over time of the elbow as being more flexed. In an alternative interpretation, the low level of activity in the slack elbow extensors picks up with time, perhaps as a result of spontaneous uptake of intrafusal slack, leading to the sensation that the extensors are becoming longer (i.e. the elbow is becoming more flexed). The time-dependent changes in position error would remain in the same direction, but the explanation would not be in terms of receptor adaptation. In animal studies of conditioning effects on discharges of identified muscle spindles, we observed that after slack had been introduced, spindles maintained a low and steady level of discharge for long periods, unless the muscle was held at a rather long length, when slack was removed spontaneously as a result of rising passive tension (Gregory et al. 1986). At the test angle of 40–50°, passive tension in human elbow muscles is low and thus the spontaneous removal of slack in spindles is unlikely. Therefore, our preferred explanation for the observations in Experiments 1 and 2 remains receptor adaptation, although we cannot exclude a contribution from changes in the activity of the antagonists. In any case, the principal conclusion from these experiments, that proprioceptive drift is attributable to a peripheral receptor mechanism, remains the same.

Although we have argued in favour of receptor adaptation as the principal mechanism for proprioceptive drift, we do not, of course, exclude an additional contribution from central sources. However, we believe there is now an adequate peripheral mechanism available to account for proprioceptive drift and, in the absence of new evidence, it is unnecessary to invoke a central mechanism as well.

According to current opinion, the brain does not listen to individual spindles but to the population of afferents transmitting from a muscle or group of muscles (Bergenheim et al. 2000). In view of this, it is remarkable how closely the drift in time of perceived limb position follows the time course of adaptation estimated from individual spindle discharges. Presumably the population signal changes with a time course that differs little from that of individual afferents. In addition, the process of converting a change in afferent impulse stream into a change in sensation of limb position must be relatively direct, with little loss or distortion of information. Such considerations are of interest within the context of recent efforts to improve acceptance of prosthetic devices by providing amputees with gradable, distally referred sources of touch or movement information (Dhillon & Horch, 2005).

As far as we know, the notion that proprioceptive drift arises as a result of influences originating in the proprioceptors has not been proposed previously. Here, we have argued that the relevant afferent signal used to align the forearms in a position-matching task is the antagonist difference signal from each arm. The brain compares the two arms and calculates an overall difference. When this difference reaches a minimum value, the arms are assumed to be aligned. It remains uncertain whether any of this involves reference to a central map and it may not do so. Certainly, when position sense is measured using a pointing task rather than a matching task, there is no other arm with which to compare and reference to a central map will be necessary.

It has been proposed that there are at least two distinct body representations in the brain: the body image, and the body schema (De Vignemont, 2010). Their relationship to a third representation, the body model, remains uncertain (Longo & Haggard, 2010). The body schema could conceivably be used as a central reference point for position sense. It is dependent on ongoing proprioceptive input, operates largely unconsciously and is concerned with body movements. It is known to change rapidly as a result of a change in peripheral afferent input produced by a progressive nerve block (Inui et al. 2011). It is therefore conceivable that errors in position sense triggered by muscle conditioning are the result of changes evoked by afferents in the body schema.

Time-dependent changes in position sense after co-contraction of reference muscles (Experiments 3 and 4)

These experiments were designed to provide controls for the time-dependent changes observed in Experiments 1 and 2. In Experiments 1 and 2 only flexors or only extensors of both arms were selectively conditioned by a voluntary contraction. Adaptation of the spindle signal in the reference arm led to shifts in the perceived position of the arm in a direction that depended on which muscle had been conditioned. If this interpretation is correct, raising spindle rates in both antagonists of the reference arm should lead to time-dependent changes which annul one another because they occur in opposite directions. The reference flexors and extensors were therefore both conditioned at the test angle with isometric contractions. This would leave spindles of both muscle groups in a sensitized state. As the reference flexor signal fell from adaptation, this would be accompanied by a similar fall in extensor signal. Therefore, the difference in signals from the reference arm was predicted to be close to zero. Such low signals would not be expected to show time-dependent changes.

This result was achieved and a reduction in time-dependent errors was observed (Fig. 4). Selective conditioning of one or other of the reference antagonists led to time-dependent changes in position errors of 2.4° and 3.4°, whereas conditioning of both groups reduced the error to 1.0°. This small, non-significant change in error with time, in the direction of flexion in Experiment 3 and in the direction of extension in Experiment 4 (Fig. 4), was probably a consequence of the sequence of conditioning used (i.e. flexion first or extension first).

Experiments 3 and 4 revealed important new trends. After flexion conditioning, all errors lay 10° in the direction of flexion; thus, subjects believed their arms to be accurately aligned when in fact they differed by roughly 10° (Fig. 4). This was a very different result from that of Experiment 1. Here, we believe the source of error was the indicator arm. Our working hypothesis was that the brain calculates the difference between the flexor and extensor signals of each arm and compares these two differences to calculate the overall difference. After conditioning, the indicator flexor signal is high, whereas the difference in signals from the reference arm is low. As a result, as the indicator arm moves into the matching position, in an attempt to match the low reference signal, it stops early, 10° short of the actual position of the reference arm. This means that the stretch of indicator flexors was kept to a minimum. The same argument can be applied to the 10° of error into extension seen after extension conditioning of the indicator (Fig. 4). We therefore suspect that the brain listens to the afferent streams from each arm and during a position-matching task computes their difference. When this difference reaches a minimum value, the arms are assumed to be accurately aligned.

We do not believe the 10° of error in the direction of flexion or extension was some kind of non-specific effect resulting from indicator conditioning. In a new experimental series (Proske et al., 2014), we explored the point further. Experiment 3 was carried out in nine subjects, using the 5 s time delay. The mean ± s.e.m. position error measured was −9.3 ± 2.2°. This essentially confirms our previous result. The experiment was repeated, but this time, before the match, slack was introduced into indicator flexors by having the subject hold the arm stretched for 6 s after conditioning, as in Experiment 5. The matching error now fell to −1.4 ± 2.0°. The same cohort of subjects then carried out Experiment 4. The observed error was 7.4 ± 1.7°, again confirming earlier results. Repeating the experiment after slack had been introduced into extensors led the mean error to fall to −1.4 ± 1.5°. Thus, the introduction of slack in indicator muscles caused the difference between flexor and extensor signals in the indicator to become smaller and this compared with the reference difference signal, which was also small. As a result, errors lay close to zero.

Experiments 3 and 4 led to three important conclusions. Firstly, the brain does not determine position sense from the afferent streams from individual muscles, but computes the difference signal from the antagonists. Experiments using muscle vibration, which is a rather more artificial method of stimulating muscles than conditioning with voluntary contractions, have led to similar conclusions (Gilhodes et al. 1986; Ribot-Ciscar & Roll, 1998). Secondly, these experiments highlight the contribution made by the indicator arm in a position-matching task at the forearm. Again, similar conclusions have been reached by others (Lackner & Taublieb, 1984; Allen et al. 2007; White & Proske, 2009; Izumizaki et al. 2010). Finally, Experiments 3 and 4 demonstrate that proprioceptive drift in the reference arm depends on the adaptation of discharge from one muscle group when its discharge is higher than that of its antagonist. Raising discharge rates in both antagonists reduces the drift because the signal difference is now smaller.

It is interesting that the errors made under the conditions of Experiments 3 and 4 were each of about 10°, although in opposite directions. In previous experiments, in which the arms were conditioned differently, errors of a similar magnitude were observed (Allen et al. 2007; White & Proske, 2009). It is somewhat unexpected that errors larger than 10° have not previously been encountered. Perhaps this represents the limit of a spindle-based system for signalling disparities in forearm position. This makes forearm position matching a short-range system with limits of ±10°.

Time-dependent changes in position sense after stretching of elbow muscles (Experiments 5 and 6)

The main aim of these experiments was to eliminate the initial offset errors after identical flexion or extension conditioning of both arms (Experiments 1 and 2). We hypothesized that the errors arose from the high spindle signal from the indicator arm during its movement into the matching position. The introduction of slack in the muscles of both arms would lower the discharge rates of muscle spindles and so reduce the error. Slack was introduced by stretching arm muscles and then shortening them (Morgan et al. 1984). As a consequence, spindle discharges dropped to low levels (Proske et al. 1992; Scott et al. 1994).

Lowering spindle discharges in both arms removed the offset errors (Fig. 5). In addition, there was no adaptation of discharge over the period of measurement because of the low rates of discharge. Therefore, by slackening muscles and their spindles, we were able to reduce position errors to lie close to zero. This indicates that if the aim in an arm-matching task is to keep position errors as small as possible, slack must first be introduced in muscles of both arms. In everyday activities, we do not systematically condition our muscles. Presumably the thixotropic status of muscles varies so that sometimes slack is present and sometimes, particularly after a contraction, parts of the muscles become sensitized. This means that over time position errors are likely to be distributed over a considerable range, underlining the inaccuracy of the muscle proprioceptive system and the need for additional inputs from vision and touch (Proske & Gandevia, 2012). In addition, it emphasizes the importance of putting muscle into a defined state for the study of position sense in humans.

Conclusions

These experiments provide evidence for some of the neural processes likely to underlie the process of forearm matching. Firstly, evidence is provided in support of the hypothesis that proprioceptive drift can be accounted for by receptor adaptation. Secondly, the experiments provide evidence that the brain is listening to the difference in the discharges from the two antagonists of each arm. It does not appear to matter whether the actual spindle rates from each antagonist are high or low because, provided that they are equal, the outcome is the same. It is the difference in rates that matters. Finally, both arms play major and probably equal roles in determining position sense at the forearm and, if the discharges from the indicator are higher than those from the reference, large errors in position matching can result (Fig. 4).

In previous experiments, when large position errors were generated by muscle conditioning, such as in Experiments 3 and 4, when subjects were asked at the end of the match whether they were satisfied with their matches, they assured the investigator that they had aligned their arms accurately (Proske & Gandevia, 2009). This suggests that the brain was unaware of the large mismatch between the two arms. It implies that once a minimum difference in signals between the two arms has been achieved, the brain assumes that the two arms are accurately aligned. When a minimum difference signal is significantly above or below zero, position errors result, errors of which the subject remains unaware. This suggests that the brain assumes similar thixotropic states for the elbow muscles of both arms, which is likely to be correct in most everyday situations. Only by experimentally imposing differences in states in the two arms can the flaws in this system be revealed.

Can these findings be applied to any other joint? For example, are the neural mechanisms for aligning the lower limbs much the same as those for aligning the forearms? While we do not yet know the answer to this question, some limited evidence is available from position matching and pointing experiments at the wrist and forearm (Walsh et al. 2013). The data suggest that the level of precision with which an unseen limb can be indicated with a pointer is similar for the elbow and wrist, but at the elbow this is inherently less precise than a comparison of signals in a two-limb matching task. Thus, at the elbow the neural mechanism concerned with comparing signals from the two arms has evolved a high level of accuracy that is higher than at other joints, such as the wrist. We propose that this is a short-range system (±10°) in which limits are defined by the range of background discharges of spindles in the two arms.

Our current working hypothesis is that in position matching at the elbow, in the absence of vision, the initial alignment of the arms makes use of a central reference map. When the arms are sufficiently close to one another, within a range of ±10°, a second mechanism comes into play, which uses the difference signal coming from arm proprioceptors. This second mechanism is more accurate than a mechanism based on reference to a central map. Why do we need such an accurate system? In everyday tasks we commonly use a posture in which the arms are held in front of the body, with the hands facing each other, in order to use the two hands as a single instrument, to make skilled cooperative movements and to fashion tools. Such skills in our ancestors are likely to have contributed to our present-day dominance over other animals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Melita Giumarra for her constructive comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

- EMG

electromyography

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the conception and execution of the project, and in data processing and the preparation of the material for publication. All experiments were carried out in the Department of Physiology at Monash University.

References

- Allen TJ, Proske U. Effect of muscle fatigue on the sense of limb position and movement. Exp Brain Res. 2006;170:30–38. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TJ, Ansems GE, Proske U. Effects of muscle conditioning on position sense at the human forearm during loading or fatigue of elbow flexors and the role of the sense of effort. J Physiol. 2007;580:423–434. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TJ, Leung M, Proske U. The effect of fatigue from exercise on human limb position sense. J Physiol. 2010;588:1369–1377. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansems GE, Allen TJ, Proske U. Position sense at the human forearm in the horizontal plane during loading and vibration of elbow muscles. J Physiol. 2006;576:445–455. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergenheim M, Ribot-Ciscar E, Roll JP. Proprioceptive population coding of two-dimensional limb movements in humans. 1. Muscle spindle feedback during spatially oriented movements. Exp Brain Res. 2000;134:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s002210000471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Cohen J. Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature. 1998;391:756. doi: 10.1038/35784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LE, Rosenbaum DA, Sainsburg RL. Limb position drift: implications for control of posture and movement. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:3105–3118. doi: 10.1152/jn.00013.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke D, Gandevia SC. The human muscle spindle and its fusimotor control. In: Ferrell W, Proske U, editors. Neural Control of Movement. London: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Clark F, Burgess RC, Chapin W, Lipscomb WT. Role of intramuscular receptors in the awareness of limb position. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:1529–1540. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.6.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vignemont F. Body schema and body image – pros and cons. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:669–680. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmurget M, Vindras P, Grea H, Viviani P, Grafton ST. Proprioception does not quickly drift during visual occlusion. Exp Brain Res. 2000;134:363–377. doi: 10.1007/s002210000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon GS, Horch KW. Direct neural sensory feedback and control of a prosthetic arm. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2005;13:468–472. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.856072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhodes JC, Roll JP, Tardy-Gervet MF. Perceptual and motor effects of agonist–antagonist muscle vibration in man. Exp Brain Res. 1986;61:395–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00239528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goble DJ, Lewis CA, Brown SH. Upper limb asymmetries in the utilization of proprioceptive feedback. Exp Brain Res. 2006;168:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0280-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM, McCloskey DI, Matthews PBC. The contribution of muscle afferents to kinaesthesia shown by vibration induced illusions of movement and by the effects of paralysing joint afferents. Brain. 1972;95:705–748. doi: 10.1093/brain/95.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JE, Morgan DL, Proske U. Aftereffects in the responses of cat muscle spindles. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:451–461. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JE, Morgan DL, Proske U. Aftereffects in the responses of cat muscle spindles and errors of limb position sense in man. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:1220–1230. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.4.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JE, Wise AK, Wood SA, Prochazka A, Proske U. Muscle history, fusimotor activity and the human stretch reflex. J Physiol. 1998;513:927–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.927ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DK. Tension due to interaction between the sliding filaments in resting striated muscle. The effect of stimulation. J Physiol. 1968;199:637–684. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth H. The inaccuracy of movement. Arch Psychol. 1909;2:1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Izumizaki M, Tsuge M, Akai L, Proske U, Homma I. The illusion of changed position and movement from vibrating one arm is altered by vision or movement of the other arm. J Physiol. 2010;588:2789–2800. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui N, Walsh LD, Gandeviaq SC. Dynamic changes in the perceived posture of the hand during ischaemic anaesthesia of the arm. J Physiol. 2011;589:5775–5784. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.219949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke MT, Proske U, Struppler A. Measurements of muscle stiffness, the electromyogram and activity in single muscle spindles of human flexor muscles following conditioning by passive stretch or contraction. Brain Res. 1989;493:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammers MPM, de Vignemont F, Verhagen L, Dijkerman HC. The rubber hand illusion in action. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner JR. Some influences of tonic vibration reflexes on the position sense of the contralateral limb. Exp Neurol. 1984;85:107–113. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(84)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner JR, Taublieb AB. Influence of vision on vibration-induced illusions of limb movement. Exp Neurol. 1984;85:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(84)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakie M, Walsh EG, Wright GW. Resonance at the wrist demonstrated by the use of a torque motor: an instrumental analysis of muscle tone in man. J Physiol. 1984;353:265–285. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo MR, Haggard P. An implicit body representation underlying human position sense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11727–11732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003483107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews PBC. Mammalian Muscle Receptors and their Central Actions. London: Arnold; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews PBC. Proprioceptors and their contribution to somatosensory mapping: complex messages require complex processing. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1988;66:430–438. doi: 10.1139/y88-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DI. Differences between the senses of movement and position shown by the effects of loading and vibration of muscles in man. Brain Res. 1973;61:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL, Prochazka A, Proske U. The after-effects of stretch and fusimotor stimulation on the responses of primary endings of cat muscle spindles. J Physiol. 1984;356:465–477. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillard J, Brouchon M. Active and passive movements in the calibration of position sense. In: Freeman SJ, editor. The Neuropsychology of Spatially Oriented Behaviour. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press; 1968. pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Morgan DL, Gregory JE. Muscle history dependence of responses to stretch of primary and secondary endings of cat soleus muscle spindles. J Physiol. 1992;445:81–95. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Morgan DL, Gregory JE. Thixotropy in skeletal muscle and in muscle spindles: a review. Prog Neurobiol. 1993;41:705–721. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90032-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Gandevia SC. The kinaesthetic senses. J Physiol. 2009;587:4139–4146. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signalling body shape, body position and movement and muscle force. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1651–1697. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Tsay A, Allen TJ. 2014. Muscle thixotropy as a tool in the study of proprioception (submitted)

- Ribot-Ciscar E, Roll JP. Ago-antagonist muscle spindle inputs contribute together to joint movement coding in man. Brain Res. 1998;791:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JP, Vedel JP. Kinaesthetic role of muscle afferents in man, studied by tendon vibration and microneurography. Exp Brain Res. 1982;47:177–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00239377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JJA, Gregory JE, Proske U, Morgan DL. Correlating resting discharge with small signal sensitivity and discharge variability in primary endings of cat soleus muscle spindles. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:309–316. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay A, Allen TJ, Leung M, Proske U. The fall in force after exercise disturbs position sense at the human forearm. Exp Brain Res. 2012;222:415–425. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3228-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB. Muscle spindle response at the onset of isometric voluntary contractions in man. Time difference between fusimotor and skeletomotor effects. J Physiol. 1971;218:405–431. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB. Human muscle spindle discharge during isometric voluntary contractions. Amplitude relations between spindle frequency and torque. Acta Physiol Scand. 1974;90:319–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1974.tb05594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh LD, Proske U, Allen TJ, Gandevia SC. The contribution of motor commands to position sense differs between elbow and wrist. J Physiol. 2013;591:6103–6114. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wann JP, Ibrahim SF. Does limb proprioception drift? Exp Brain Res. 1992;91:162–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00230024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White O, Proske U. Illusions of forearm displacement during vibration of elbow muscles in humans. Exp Brain Res. 2009;192:113–120. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1561-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LR, Gandevia SC, Burke D. Increased resting discharge of human spindle afferents following voluntary contractions. J Physiol. 1995;488:833–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter JA, Allen TJ, Proske U. Muscle spindle singals combine with the sense of effort to indicate limb position. J Physiol. 2005;568:1035–1046. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]