Abstract

Treatment with mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) is currently of interest for a number of diseases including multiple sclerosis. MSCs are known to target inflamed tissues, but in a therapeutic setting their systemic administration will lead to few cells reaching the brain. We hypothesized that MSCs may target the brain upon intranasal administration and persist in central nervous system (CNS) tissue if expressing a CNS-targeting receptor. To demonstrate proof of concept, MSCs were genetically engineered to express a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific receptor. Engineered MSCs retained their immunosuppressive capacity, infiltrated into the brain upon intranasal cell administration, and were able to significantly reduce disease symptoms of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Mice treated with CNS-targeting MSCs were resistant to further EAE induction whereas non-targeted MSCs did not give such persistent effects. Histological analysis revealed increased brain restoration in engineered MSC-treated mice. In conclusion, MSCs can be genetically engineered to target the brain and prolong therapeutic efficacy in an EAE model.

Keywords: chimeric antigen receptor, experimental autoimmune encephalitis, gene engineering, mesenchymal stromal cells, multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a heterogeneous population of stromal cells residing in most connective tissues, bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, blood and perivascular tissues. These stem cells can differentiate into cells of the mesenchymal lineage, such as bone, cartilage, adipose tissue, tendon and muscle.1,2 MSCs can suppress both innate and adaptive immune reactions.3–5 They have been shown to modulate the function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells via down-regulation of antigen presentation and co-stimulation,6,7 inhibit proliferation, cytotoxicity and cytokine production of natural killer cells and induce cell cycle arrest in T cells.8,9 Also, MSCs inhibit B-cell proliferation, differentiation and constitutive expression of chemokine receptors10 and promote the generation of regulatory T cells.11 Several studies have highlighted the ability of MSCs to contribute to central nervous system (CNS) repair in experimental studies of multiple sclerosis, stroke,12–15 trauma16 and Parkinson's disease.17 Migration of MSCs to the CNS also occurs in human recipients of bone marrow transplants and it has been demonstrated that systemically infused therapeutic MSCs can migrate to and suppress the ongoing inflammation in the CNS.18

There is considerable interest in cell-based therapies for inflammatory diseases, especially upon MSCs because of their excellence in suppressing inflammation. MSCs are used in the clinic with great success to prevent graft-versus-host disease19 and could potentially be used in the clinic for several other purposes: to repair damaged tissues and to promote haematopoietic engraftment following autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Multiple clinical trials to evaluate their safety, feasibility and efficacy are currently ongoing, as previously reviewed.20 MSC therapy has been reported to reduce clinical symptoms in an animal model of mulitple sclerosis, but because of poor access into the brain, high cell numbers are required to achieve a therapeutic effect.21 MSCs have been injected intrathecally into patients with multiple sclerosis, demonstrating the feasibility of MSC therapy. However, clinical materials are generally still too scarce to allow meaningful therapeutic conclusions.22–24 MSCs traffic to inflamed tissues, but it remains unclear for how long the transplanted cells survive in vivo and if they reside in or leave the site of action post-inflammation.

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is an immune-mediated disease model with pathological similarities to human multiple sclerosis, including CNS inflammation, myelin loss, axonal damage and neurological disability. In EAE, immune cells, particularly activated T cells, migrate from the periphery across the blood–brain barrier to the CNS parenchyma where they exert pathogenic effects. MSCs have previously been used in the EAE model with promising results. Barhum et al.25 demonstrated that human MSCs could be detected in the mouse brain 1 month following intracerebroventricular injection, indicating that the xenogeneic response is diminished against these cells. Other groups have reported that peripheral delivery of either human25,26 or murine1 MSCs into mice with EAE reduces disease severity. Systemic infusion has been the predominant mode of administration of MSCs, but the cells become entrapped in the afferent vessels of the lung and are degraded therein.27,28 Intraperitoneal (i.p.) or intravenous infusion of MSCs only results in a minor influx of MSCs into inflamed areas and they do not reside long enough for a continuous effect.29

To increase homing efficiency and persistence of MSCs in the CNS we hypothesized that MSCs can be genetically engineered to target the CNS and suppress local inflammation upon administration. Efficient CNS-targeting of MSCs may improve their retention within the CNS. Resident MSCs may be able to better suppress ongoing inflammation as well as preventing the formation of new lesions. An interesting option to further increase the transfer of MSCs into the brain and to minimize the number of cells required is the use of intranasal (i.n.) cell delivery. In the present study we investigated the treatment efficacy of genetically engineered MSCs targeting myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) via a single i.n. or i.p. cell administration in an EAE model.

Materials and methods

Isolation and expansion of adult human MSCs and HUVECs

Mesenchymal stromal cells were isolated and expanded from bone marrow as previously described5 following approval by the Ethics Committee at Huddinge University Hospital and have further been approved for use in our studies (Dnr 2013/144). The cells were cultured in MSC medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium–low glucose, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (from PAA, Pasching, Austria) and 1% antibiotic solution. Cells were classified as MSCs based on plastic adherence, differentiation to bone and fat, and expression of surface markers (CD166, CD105, CD44, CD29, SH-3, SH-4 and negative for CD34 and CD45).5 MSCs in passage five to eight from three donors were used in this study. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) were cultured in endothelial cell growth medium (PromoCell) on 1% gelatine-coated tissue-culture-treated plastic. The HUVECs were cultured in passages 4–12.

Chimeric antigen receptor construct for MOG targeting

The CARαMOG vector was constructed as follows: a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) was cloned from the 8.18C5 hybridoma30 producing anti-rat MOG antibodies. The MOG scFv was inserted into a conventional chimeric antigen receptor (CAR),31 which yields stable cell surface expression of the targeting device. The final CAR construct was inserted into the lentiviral vector pRRL-CMV (a kind gift from R Houeben, Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands). Lentiviruses (Lenti-CARαMOG, Lenti-Mock, Lenti-GFP, Lenti-MOG) were produced by co-transfecting 293FT cells with pLP1, pLP2 and pLP/VSVG (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Virus supernatants were harvested on days 2 and 3 and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Viral supernatants were added to 5 × 104 MSCs in 100 μl RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% non-essential amino acids, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from Invitrogen) and 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St Louis, MO). Cells were incubated for 4 hr at 37°, 5% CO2 followed by addition of 300 μl of medium (as above) and the following day medium was replaced. Cells were cultured for 7 days. Transduction efficiency was analysed 3–6 days post-transduction. Transduced cells were incubated for 10 min at 4° with FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibody specific for the κ chain in the scFv (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Samples were analysed for surface expression of CAR or GFP using FACScanto (BD Biosciences).

Antibody production and purification

Hybridoma cell line 8-18C528 was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Antibodies were purified using protein affinity column chromatography (HiTrap MabSelect; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) following addition of 0·5 m trisodium citrate (Sigma, St Louis, MO) to the clarified supernatant. The column was washed with 500 mm sodium citrate pH 8·5 and the antibody fraction was eluted with 0·1 m glycine (Sigma) at pH 2·7. The eluate was neutralized using Tris–HCl (Sigma) at pH 8 and concentrated using a JumboSep ultrafiltration device and 10 000 molecular weight cut-off filter (Pall Gellman, WWR International, Stockholm, Sweden). Specificity was confirmed through Western blotting analyses of whole mouse myelin and recombinant MOG.

Suppression assay

For in vitro suppression, 3 × 104 CARαMOG or mock-transduced MSCs were irradiated at 25 Gy and mixed in different ratios with αCD3/interleukin-2-stimulated splenocytes in a total volume of 200 μl/well RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% non-essential amino acids, 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were seeded in 96-well round-bottom tissue-culture-treated plates and incubated for 48 hr after which 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) was added per well and cells were incubated for an additional 8 hr before analysis using a β-counter (Perkin Elmer Life Science, Turku, Finland). In some experiments, as indicated in the figures, murine macrophages (2·5 × 104) or MOG+ cells (2·5 × 104) were added to cultures with CARαMOG-transduced MSCs at a 1 : 1 ratio. Activated macrophages were obtained via plastic adherence of monocytes from spleen (see Supporting information, Fig. S1). MOG+ cells were generated via lentiviral gene transfer of murine MOG to 293T cells. MOG expression was confirmed using immunohistochemistry with αMOG antibodies from clone 8.18C5.

EAE induction and cell therapy

Female C57BL/6 (6 weeks) mice were purchased from Taconic M&B (Ry, Denmark). Mice were housed in the Department of Animal Resources facility at Uppsala University and used at 6–8 weeks of age. All studies were approved by the regional animal ethics committee in Uppsala (Dnr: C28/10). EAE was induced by immunization with 200 μg MOG35–55 peptides emulsified in complete Freunds' adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) containing 5 mg/ml Mycobacterium tuberculosis subcutaneously located near the limbs. Pertussis toxin (100 ng i.p.; Sigma Aldrich) was given at the time of immunization and a second dose 2 days later. Disease severity was monitored according to the following scale: 0, no disease; 1, flaccid tail; 2, hind limb weakness; 3, hind limb paralysis; 4, fore limb weakness; 5, moribund. When mice exhibited a mean score of 3 (2 weeks post-immunization) they were treated with cell therapy. A low dose of cells (1 × 104 CARαMOG or mock-transduced MSCs dispersed in 10 μl PBS) or vehicle were administered i.n. in 5 μl PBS using a plastic catheter connected to a pipette (polyethylene tube; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) inserted for 3 mm in both nasal nostrils of groups of mice during a short anaesthesia (0·05–0·1 mg ketamine–xylazine mixture/10 g bodyweight; ketamine 50 mg/ml, Pfizer AB, Sweden; xylazine 20 mg/ml, Bayer AG Animal Health, Business group, Wuppertal, Germany). For i.p. cell therapy, a low dose (1 × 104 dispersed in 100 μl PBS) of CARαMOG or mock-transduced MSCs or vehicle were injected into groups of mice. Mice were killed with gaseous CO2 and brains were excised and fixed in ice-cold 4% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde (pH 7·4) for paraffin embedding or were frozen by immersion in isopentane (with dry-ice) for cryosectioning. Brains, embedded in low-melting-point paraffin after a graded series of alcohol dehydration and xylene treatment, were sectioned in the sagittal plane (4 μm), mounted on gelatine-coated glass and used for immunohistochemistry. In addition, to exclude the possibility that treatment with human cells per se could reduce EAE symptoms, groups of six EAE mice were given a unilateral i.n. injection as above with 1 × 104 CARαMOG or mock-transduced human HUVEC cells or PBS and the disease severity was monitored for 15 days.

Tissue localization of human engineered MSCs in naive mice

The GFP/CARαMOG-engineered MSCs, 5 × 104 cells dispersed in 5 μl PBS, were unilaterally instilled in the right nostril as described above in healthy naive mice, which were killed 24 hr post-instillation. Horizontal cryosections (10 μm) of the brain showing the olfactory bulb, cerebrum and cerebellum were mounted onto plusglass, air-dried and stored at −80°. Tissue sections at this level were selected following brief staining with toluidine blue. Cryosections washed in cold PBS were quenched with 0·3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min, and then blocked with 2·5% normal horse serum for 1 hr. Immunofluorescence studies were performed using a primary antibody for GFP (1 : 300) ab390 (Abcam, Cambridge Science Park, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°. Fluorescence double immunohistochemistry was performed using primary antibodies against GFP (1 : 100) and HuNu (Mab 1281-567 1 : 100) and secondary antibody (Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-rabbit). Specificity controls for immunostaining included sections stained in the absence of primary antibody and staining, using the full protocol, of brain sections from mice that did not receive MSC therapy. For detection of DNA/nuclei, sections were overlain with Vectashield Mounting Medium with (DAPI) 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindoledihydrochloride (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were assessed using fluorescence microscopy for GFP (green), HuNu (red) and DAPI nuclear staining (blue). Immunofluorescence images were captured using a Leica DM RBE fluorescence microscope. Confocal images were captured using a Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope and the software zen light version (Carl Zeiss, MicroImagining GmBh, Jena, Germany). Apotome images were captured with zeiss axioimager and axiovision software (Carl Zeiss, MicroImagining GmBh).

Immunohistochemistry for nerve damage and repair

Deparaffined and rehydrated sagittal sections from mouse brains were rinsed with PBS-Tween before incubation in peroxidase-blocking reagent (EnVision; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Sections were analysed using a Leica FDC320 microsystems microscope. Myelin basic protein (MBP) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) were localized using the avidin–biotin complex method and with DAB as chromogen. Deparaffined and rehydrated sagittal sections were rinsed with PBS and PBS-Tween. For GFAP antigen demasking was performed in a microwawe oven with 10 mm sodium citrate buffer. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 1–3% H2O2 in PBS-Tween incubation and non-specific background staining was blocked with 4% BSA in PBS. The sections were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies (MBP 1 : 200 Abcam; GFAP 1 : 400 Millipore, Billerica, MA). A biotinylated secondary antibody was used followed by avidin–biotin complex (both from Vector Laboratories). Immunoreactions were visualized with DAB (Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin for 5 min followed by a tap water rinse. Finally, the tissue sections were rinsed gradually through a graded alcohol series and finally in xylene, and mounted immediately after with Pertex (Histolab, Göteborg, Sweden). The tissue sections were analysed using an Olympus microscope and images were captured using a digital camera (Nikon Dxm 1200F; Nikon corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Nikon ACT-1 version 2.62 (Nikon corporation) software. All tissue sections used for analysis were processed in parallel using the same reagent concentration and incubation times. In addition, the procedure was repeated on three separate occasions. The results were analysed in a blinded mode scoring the level of staining as weak, moderate or strong. Digital images were collected at the same time using an identical setting with respect to image exposure time and image compensation setting. Images were processed in Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator CS4.

Statistics

Significant differences between groups were calculated using GraphPad Software version 6.0 (La Jolla, CA).

Results

Engineered MSCs retain their ability to suppress T cells in vitro

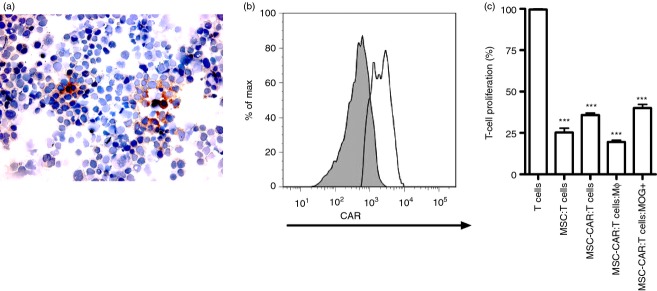

We constructed an scFv antibody domain from a hybridoma producing anti-rat MOG antibody that cross-reacted with murine MOG as evident by staining of murine MOG-transduced cells (Fig. 1a). The MOG scFv construct was introduced into a murine conventional CAR and the CARαMOG construct was inserted into a lentiviral vector system. Human MSCs were engineered by transducing MSCs with the CARαMOG lentiviral vectors. Transduction efficiency ranged from 60% to 89% measured with a κ-chain-specific antibody and exemplified in Fig. 1(b) depicting flow cytometric immunostaining. Engineered MSCs were equally good as unmodified MSCs in suppressing proliferation of polyclonally stimulated T cells (P < 0·001) at a 1 : 2 ratio (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, when exposing engineered MSCs to MOG+ cells or activated macrophages (for phenotype expression see Supporting information, Fig. S1) they were still able to suppress T-cell proliferation (P < 0·001).

Figure 1.

Genetic engineering of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC)s with a central nervous system (CNS) -targeting receptor. (a) Anti- myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody staining of 293T cells transduced with Lenti-murine MOG. (b) MSCs transduced with CARαMOG receptors were analysed for surface expression using flow cytometry. (c) MSCs and engineered MSCs were mixed with αCD3/interleukin-2-stimulated T cells at a 1 : 2 ratio and analysed for suppressive ability in a thymidine-based assay. All samples were analysed in triplicates. Engineered MSCs suppressed activated T cells (P < 0·001). Engineered MSCs retained their suppressive function in the presence of lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages (P < 0·001) or MOG-expressing cells (P < 0·001). All experiments in this figure were repeated at least three times with similar results. Statistics were analysed using the Mann–Whitney test and GraphPad prism software.

Intranasal administration effectively delivers MSCs to the brain

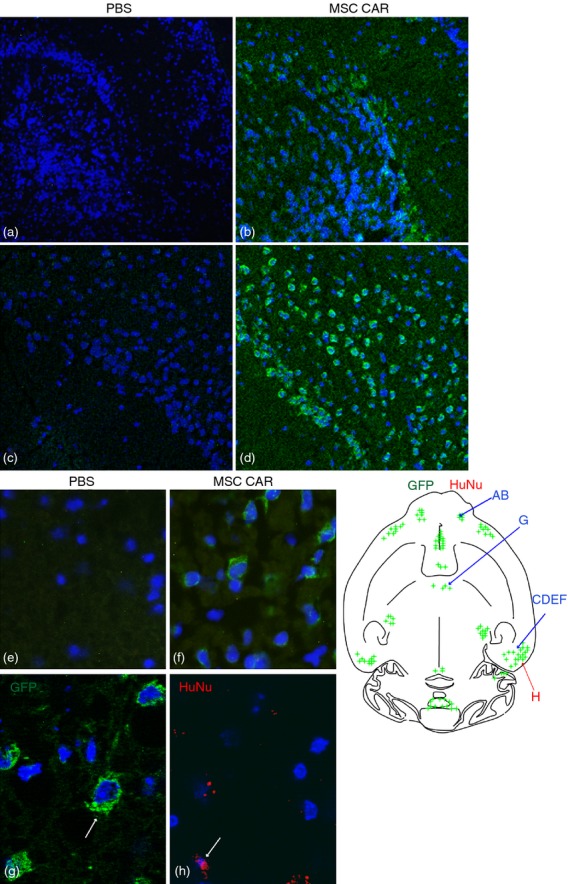

Mesenchymal stromal cells co-expressing GFP and CARαMOG were used to evaluate in vivo targeting following i.n. cell delivery in naive mice after 24 hr. The overall localization of GFP immunofluorescence is depicted in the upper schematic drawing in Fig. 2. GFP-fluorescence was mainly localized in clusters of cells in the internal plexiform layer of the olfactory bulb and anterior olfactory nucleus (Fig. 2b), ectorhinal cortex (Fig. 2d) and in the Purkinje cell layer of the cerebellum (Fig. 2f). In addition, signals were observed in the central medial genic nucleus and ventral orbital cortex, lateral septal nucleus and central medial thalamic nucleus, respectively (data not included). Immunofluorescence was only observed in the soma and was preferentially present in the perinuclear part. Although a unilateral dose of MSC was given in naive mice the localization of immunofluorescence occurred on both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides. In the PBS-treated control mice no or weak background immunofluorescence could be detected in the brain (Fig. 2a,c,e).

Figure 2.

Brain localization of central nervous system (CNS) -targeted mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC)s in naive mice following intranasal delivery. Human MSCs were instilled via a unilateral intransal (i.n.) administration and the distribution of green fluorescent protein (GFP) or human nuclei (HuNu) immunofluorescence in horizontal cryosections of the brain of naive mice was studied 24 hr after delivery. The schematic depicts a selective GFP and HuNu immunofluorescence (indicated by green and red spots) in various brain regions. Confocal microscopy reveals that GFP immunofluorescence (green) is present in the internal plexiform layer of the olfactory bulb (b) ectorhinal cortex (d) and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (f) in MSC CARαMOG-treated naive mice. The corresponding areas in PBS-treated naive mice are (a) ,(c,) and (e), respectively. Cell nuclei (blue) are stained with DAPI. Original magnifications 10× (a–f) and 40× (g,h). Immunofluorescence microscopy reveals that GFP fluorescence (green) and HuNu fluorescence (red) are both present in the ectorhinal cortex.

For further identification of human MSC CAR cells in the brains of naive mice a human-specific antiserum recognizing human nuclei (HuNu) was used. Although the immunofluorescence of HuNu (red) was low compared with the immunofluorescence of GFP (green), co-localization was confirmed by double staining. The localization of HuNu immunofluorescence is indicated in the schematic drawing in Fig. 2. Red fluorescence was detected in the central medial thalamic nucleus (Fig. 2h). In addition, red immunofluorescence was observed in the internal plexiform layer and olfactory nerve layer of the olfactory bulb, in the anterior olfactory nucleus and ectorhinal cortex (data not included). In the PBS-treated murine controls no or weak, green and red immunofluorescence could be detected.

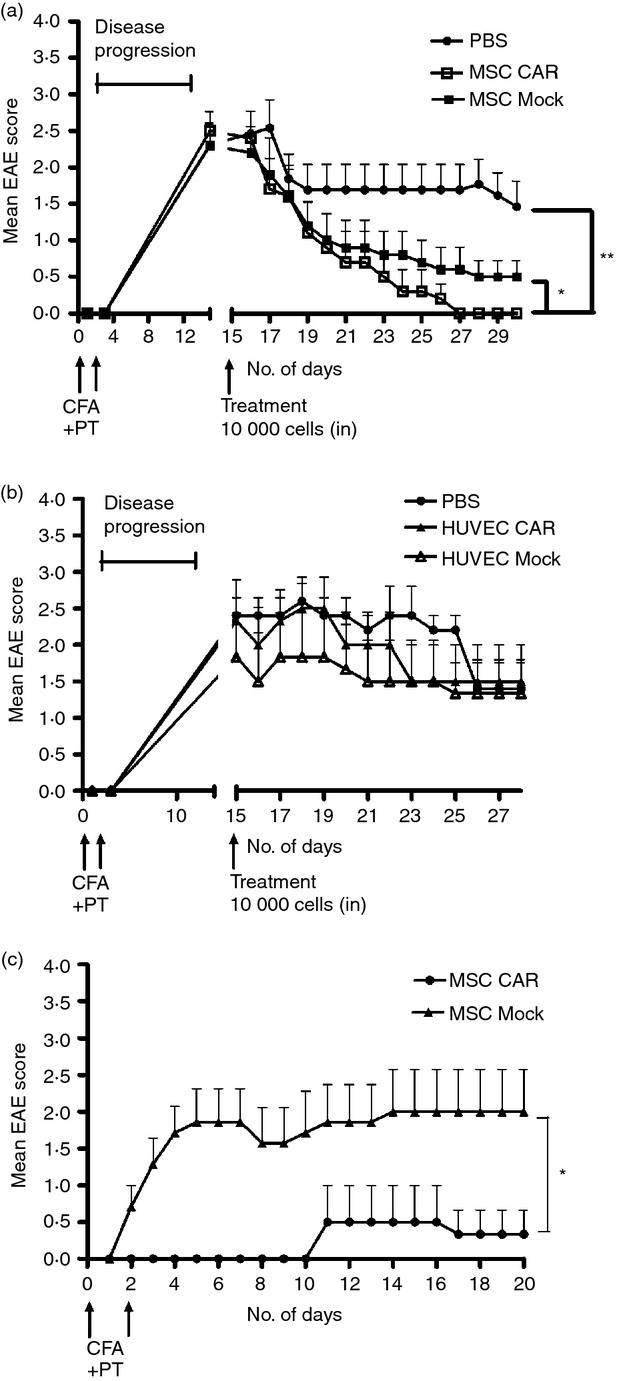

CNS-targeted MSCs had therapeutic efficacy in mice with active EAE

Genetically engineered MSCs were able to suppress activated T cells in vitro, so we sought to investigate whether they could reduce clinical symptoms in mice with EAE. At the peak of EAE inflammation (2 weeks post-immunization), a low dose of 1 × 104 CARαMOG or mock-transduced MSCs, or PBS alone, were applied via bilateral i.n. administration. Mice in both CARαMOG and Mock groups initially exhibited reduced EAE symptoms (Fig. 3a) whereas no reduction of symptoms occurred in the PBS controls. However, 15 days after MSC treatment, recovery in the Mock group was less prominent. Conversely, the CARαMOG group mice exhibited a continuous reduction of disease score and 12 days post-therapy all mice (n = 10) were symptom-free (score 0) and classified as being cured healthy mice. Only a few mice in the Mock group (n = 4) were considered to be healthy (score = 0) at end point and there were still mice in this group exhibiting clinical EAE score values of 3 (n = 2). To exclude that the reduction of EAE symptoms was the result of the conversion of an autoimmune response to a xenogeneic response, two groups of EAE mice were treated i.n. with CARαMOG and mock-transduced human HUVEC cells (Fig. 3b). Neither CARαMOG nor mock-engineered HUVEC cells reduced clinical score 15 days after initial HUVEC treatment in animals with EAE.

Figure 3.

Efficacy of central nervous system (CNS) -targeted mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC)s in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice. (a) Ten EAE mice in three groups were given a low dose (1 × 104) of engineered CARαMOG or Mock MSCs or PBS alone by intranasal (i.n.) administration at the peak of EAE inflammation (15 days post-EAE immunization). Ten days after i.n. MSC treatment all mice in the CARαMOG group were symptom-free (**P < 0·01). At end-point (15 days after i.n. MSC treatment) mice in the mock-treated group still exhibited EAE symptoms (P < 0·05). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (b) To exclude that treatment efficacy was due to a xenogeneic response of the human MSC, mice were treated with human HUVEC cells equipped with the CARαMOG targeting receptor. Six mice in three groups were given a low dose (1 × 104) of engineered CARαMOG or Mock HUVECs, or PBS alone by i.n. delivery at the peak of EAE inflammation (15 days post-EAE immunization). (c) Cured EAE mice from each treatment group of i.n. MSCs (n = 6) were given a second EAE immunization (as described previously). MSC CARαMOG-treated mice were able to resist EAE inflammation longer than MSC-mock-treated mice (*P < 0·05). Statistics were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test and GraphPad prism software.

At day 30 (15 days post-initial MSC treatment), healthy mice from each group of CARαMOG- and Mock-treated mice were re-challenged using another cycle of MOG, complete Freunds' adjuvant and pertussis toxin to investigate if CARαMOG MSCs provided continuous protection against EAE induction. In contrast, in the Mock group all mice already exhibited EAE symptoms 2 days after the repeated EAE challenge. In the CARαMOG group all mice resisted the second EAE challenge until day 10, at which point one mouse developed mild signs of EAE. Nevertheless, this mouse recovered 7 days later (Fig. 3c).

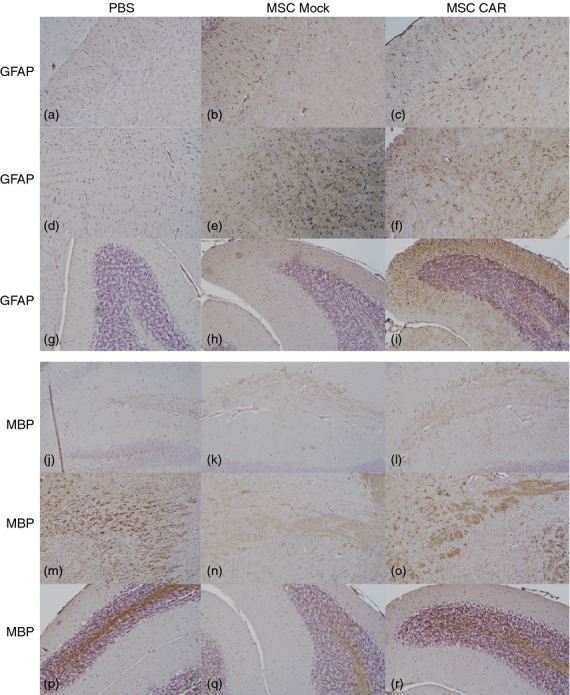

CNS-directed MSCs modulate biomarkers in active EAE

Upon immunohistochemical examination using markers for reactive astrogliosis (GFAP) and myelination (MBP), axonal recovery was confirmed in mice in the CARαMOG group 15 days following i.n. administration of MSC. Reactive astrogliosis was evaluated in the corpus callosum (Fig. 4a–c), brainstem (Fig. 4d–f), cerebellum (Fig. 4g–i), olfactory bulb (see Supporting information, Fig. S2a–c) and hippocampus (Fig. S2d–f). An increased GFAP staining was detected in MSC CARαMOG- or Mock-treated EAE mice but not in PBS-treated EAE mice. The level of staining was higher in CARαMOG-treated EAE mice compared with Mock-treated EAE mice in the cerebellum, brainstem and corpus callosum, whereas the level of staining was similar in the hippocampus and olfactory bulb of CARαMOG-treated and Mock-treated EAE mice.

Figure 4.

Effects of intranasally delivered CNS-targeted mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) on axonal damage and tissue recovery in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice. Immunohistochemical staining for glial acidic fibrillary protein (GFAP) in corpus callosum (a–c), brainstem (d–f) and cerebellum (g–i) in brain sections from PBS-, MSC Mock- and MSC CARαMOG-treated EAE mice (15 days after i.n. treatment). In MSC CARαMOG-treated EAE mice there is strong staining in all areas (c,f,i). In MSC Mock-treated mice there is strong staining in all areas (b,e,h). In PBS-treated EAE mice there is weak staining (a,d,g). Immunohistochemical staining for myelin basic protein (MBP) in hippocampus (j–l), brainstem (m–o) and cerebellum (p–r) in brain sections from PBS-treated, MSC Mock-treated and MSC CARαMOG-treated EAE mice. In MSC CARαMOG-treated EAE mice there is strong staining of all areas (l,o,r). In MSC Mock-treated mice there is weak staining in all areas (k,n,q). In PBS-treated EAE mice there is moderate staining in hippocampus (j) and strong staining in brainstem and cerebellum (m,p). Original magnification 10×.

Expression of MBP was evaluated in the hippocampus (Fig. 4j–l), brainstem (Fig. 4m–o), cerebellum (Fig. 4p–r), olfactory bulb (Fig. S2g–i) and corpus callosum (Fig. S2j–l). The degree of demyelination, as indicated by the loss of MBP staining, was greater in PBS-treated EAE mice compared with CARαMOG-treated mice in all areas except in the cerebellum and brainstem, where staining intensity was similar.

The MBP staining in the brain of MSC Mock-treated EAE mice was lower compared with in MSC CAR-treated and PBS-treated mice. Damage to axons was evaluated in the cerebellum and brainstem.

CNS-infiltrating T cells have decreased interferon-γ responses but produce interleukin-17

T cells recovered from the spleens and brains of MSC CARαMOG- and Mock-treated EAE mice were restimulated in vitro to establish T-cell activation status. T cells were stimulated with a mix of MHC I- and MHC II-binding MOG peptides and evaluated by flow cytometry for secretion of interleukin-17 and interferon-γ (Fig. 5a,b). Brain T cells from EAE mice treated with either CARαMOG or Mock MSCs exhibited a low secretion of interferon-γ from both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells whereas interleukin-17 was produced by the CD4+ population. T cells isolated from the spleens of both experimental groups responded to polyclonal stimuli, indicating that peripheral T cells were not anergized and that the suppressive effects of MSCs are restricted to the brain. Brain biopsies of EAE mice were further analysed for T helper type 1 cytokines (interferon-γ and interleukin-12) using real time PCR. While PBS-treated mice had higher levels of both interferon-γ and interleukin-12 transcripts, EAE mice treated with either CARαMOG or Mock MSCs had only low levels of these cytokines, although these differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5c,d).

Figure 5.

Immunological evaluation of intranasal mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) treatment efficacy. T cells from brain (a, n = 3) and spleen (b, n = 3) from MSC CARαMOG and MSC Mock-treated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitisEAE mice were isolated using a MACS T-cell separation kit, stimulated for 24 hr and analysed for cytokine production [interleukin-17 (IL-17) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)]. T cells isolated from brain were stimulated with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptides (MOG37–46, MOG35–55) whereas T cells isolated from the spleen were stimulated with αCD3/IL-2. In the brain CD4+ T cells responded by secreting IL17 to a higher extent in the MSC Mock-treated mice compared with MSC CARαMOG-treated mice; however, the difference was not significant. Effector cytokines (c: IFN-γ, d: IL-12) were analysed by quantitative PCR from brain biopsies obtained from MSC CARαMOG-treated and MSC Mock-treated mice (15 days post-MSC treatment).

CNS-targeted MSCs, but not Mock MSCs, efficiently treat EAE upon i.p. delivery

To investigate if the targeted MSCs had a therapeutic effect following systemic administration, a low dose of cells (1 × 104 CARαMOG or Mock-transduced MSCs) was infused i.p. in EAE mice. CARαMOG MSCs were able to reduce EAE symptoms whereas the symptoms in Mock MSCs were comparable to those in PBS-treated EAE mice (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Efficacy of systemic delivery of central nervous system (CNS) -targeted mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC)s in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice. Ten mice in three groups were given a low dose (1 × 104) of CARαMOG or mock MSCs or PBS alone by intraperitoneal (i.p.) infusion at peak of EAE inflammation (15 days post-EAE immunization). Ten days post-MSC treatment all mice in the MSC CARαMOG group were cured (**P < 0·01). At end-point (15 days post-treatment) 7/10 mice in the mock-treated group still exhibited EAE symptoms (*P < 0·05). Statistics were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test and GraphPad prism software. The challenge experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Discussion

In the current study we have demonstrated how MSCs can be genetically engineered and targeted to the CNS. Engineered MSCs potently reduce disease symptoms in an EAE model followed by i.n. delivery. Furthermore, mice that recovered from EAE symptoms by CARαMOG MSC treatment were resistant to subsequent MOG antigen challenge while recovered mice that received non-targeted MSCs rapidly developed EAE after being re-challenged.

Chimeric antigen receptors are currently used to retarget cytotoxic T cells to tumour antigens, creating tumour-reactive T cells for cell therapy of cancer.32 We constructed a similar CAR to generate MOG-targeting MSCs and demonstrated proof-of-principle of their function. The MOG targeting CAR has previously been successfully used to retarget T regulatory cells to the brain in the EAE model.33 Genetic engineering of MSCs did not affect their immunosuppressive capacity in our in vitro model of inflammation where engineered MSCs were equally good in suppressing activated T cells and macrophages as unmodified MSCs.

Due to immune modulatory differences in the murine and human MSC population,34 human MSC were used in the current study. Zhang et al.15 have previously demonstrated that intravenous administration of human MSC improved the clinical course of proteolipid protein-induced EAE while human MSCs have been shown to be rejected in a murine model of islet transplantation.35 These discrepancies may be due to disease settings or because the brain is an immune privileged site.

Recent data from early clinical trials treating multiple sclerosis patients with MSCs have revealed poor infiltration of cells into the CNS following either intravenous or intrathecal injections.24 In an attempt to attain therapeutically effective numbers of MSC in the brain we delivered engineered cells via the nasal mucosa. Intranasal delivery has shown potential for transplantation of cells into the brain and may be a means of reducing the cell doses required for therapeutic efficacy while at the same time decreasing systemic exposure.36–39 We demonstrated that it was possible to treat EAE mice with a single, low dose of engineered MSCs and yet still achieve therapeutic efficacy when the cells were delivered i.n. The low numbers of cells used in our i.n. protocol are equivalent to a dose of 0·5 × 105 MSC/kg in humans, a number that could easily be obtained using current clinical production protocols of human MSCs.

Upon i.p. delivery, CARαMOG MSCs were able to decrease disease symptoms at the same low cell doses used in the i.n. study protocol while the Mock MSCs did not. It is possible that a number of cells were rejected because of xenogeneic responses to the i.p. injected cells but as a result of the expression of the CARαMOG receptor, sufficient numbers of cells might have been retained in the CNS to exert a therapeutic effect. Reduced clinical disease symptoms correlated with reduced damage to axons were exemplified by immunohistochemical analyses of MBP.

As it has been demonstrated that human MSCs improve the clinical course of EAE in mice15,40 it was expected that mice treated with both CARαMOG MSCs and non-targeted MSCs would show reduced symptoms of EAE. However, mice that recovered from EAE symptoms by CARαMOG MSC treatment were resistant to subsequent MOG antigen challenge while recovered mice that received non-targeted MSCs rapidly developed EAE following re-challenge. This may be due to the ability of targeted MSCs to reside in the brain post-inflammation while non-targeted cells may migrate to other sites. It was not possible to detect GFP-positive cells 15 days after MSC treatment. The difference in treatment efficacy between targeted and non-targeted MSCs might be due to a biological reprogramming effect such as induction of T regulatory cells at site. However, this issue remains to be investigated through in vivo tracking of cells and biological markers, such as cytokines, over time.

Previous experimental studies using i.n. administration of stem cells have indicated that their delivery into the brain is relatively low.37,38 However, brain sections of naive mice treated with GFP-labelled CARαMOG MSCs suggest a localization of GFP immunofluorescence in various brain areas (such as the olfactory bulb) following i.n. administration in naive mice after 24 hr. To confirm the presence of human MSCs at these sites, additional immunohistochemical studies were performed using an antibody specific for human nuclei.41 We revealed weak HuNu staining in the same areas but both the number of cells and the staining intensity were markedly lower than that observed with GFP immunofluorescence. The increased GFP immunofluorescence could be a result of the MSCs' capacity to transfer material and interact with other cells. Previous reports suggest a fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with various epithelial cell types42–44 while others have demonstrated that MSCs can transfer genetic material to neighbouring cells via microvesicles.45 Considerably, this might be a reason that GFP immunofluorescence could be detected to a markedly higher extent than human nuclear events (HuNu). Further studies are therefore needed to characterize the migration, identity and long-term survival of engineered MSCs delivered via the i.n. route into the brain.

The olfactory pathways, located in the posterior nasal cavity, may provide a port of entry for drugs, metals and environmental pollutants into the brain because the olfactory neurons have dendrites projecting into the nasal mucus and axons projecting into the olfactory bulb.46,47 Therapeutic MSCs deposited locally on the olfactory epithelium may therefore circumvent the blood–brain barrier and pass the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone to the olfactory bulb in extracellular channels made up of olfactory ensheathing cells. However, in our studies, GFP- and HuNu-positive immmunofluorescence staining were observed after 24 hr on both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides following a unilateral application of engineered MSCs, suggesting that a migration of MSCs to the brain may not be confined to the olfactory pathways or that there is migration within the brain following an initial olfactory migration. In addition, migration of MSCs from the nasal mucosa into the general blood circulation cannot be excluded because the nasal mucosa is highly vascularized.48,49

A potential risk of MSC treatment is their ability to suppress anti-tumour surveillance that could result in tumour progression and metastasis in the same manner as that evident in patients subjected to life-long immunosuppressive drugs post-transplantation. A further risk associated with MSC expansion in vitro is subsequent in vivo differentiation into malignant cells as observed upon in vivo administration in rodents.50 Nonetheless, there is general agreement that bone-marrow-derived human MSCs can safely be expanded in vitro with limited risk of malignant transformation.51,52 By inserting an inducible suicide gene in trans with CARαMOG the engineered MSCs would provide a safer option than regular MSCs.

In conclusion, we have developed CNS-targeting MSCs that efficiently reduce EAE symptoms in mice following i.n. delivery. MSC-derived proteins were detected in selected areas of the brain upon i.n. cell delivery and furthermore, we have revealed that targeting of the MSCs results in sustained treatment efficacy because engineered MSC-treated EAE mice cannot be provoked to show new EAE symptoms after re-challenge. Targeted MSCs may therefore be an interesting therapeutic option for multiple sclerosis as well as for other organ-specific autoimmune conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Lu at Pittsburgh University for teaching us the EAE model and Mrs Raili Engdahl and Berith Nilsson for technical assistance during animal experiments and viral vector production, respectively. This study was supported by grants to Dr Loskog from the Swedish Research Council and the Medical Faculty at Uppsala University, to Dr Fransson, from the Göransson-Sandviken fund.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest except from Dr Loskog who is the CEO of Lokon Pharma AB, scientific advisor of NEXTTOBE AB and has a royalty agreement with Alligator Biosciences AB. None of these have an economical relation/conflict with the results presented herein.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Phenotype of lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages.

Figure S2. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and myelin basic protein (MBP) staining of the olfactory bulb and hippocampus.

References

- 1.Bernado ME, Pagliara D, Locatelli F. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy: a revolution in regenerative medicine? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:164–71. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–7. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells. Curr Opin Hematol. 2006;13:419–25. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000245697.54887.6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Immunoregulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2566–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Blanc K, Tammik L, Sundberg B, Haynesworth SE, Ringden O. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57:11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyth S, Borovsky Z, Mevorach D, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells alter antigen-presenting cell maturation and induce T-cell unresponsiveness. Blood. 2005;105:2214–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmusson I, Ringden O, Sundberg B, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by mitogens and alloantigens by different mechanisms. Exp Cell Res. 2005;305:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1482–90. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prevosto C, Zancolli M, Canevali P, Zocchi MR, Poggi A. Generation of CD4+ or CD8+ regulatory T cells upon mesenchymal stem cell–lymphocyte interaction. Haematologica. 2007;92:881–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Lu M, Zhang X, Chopp M. Therapeutic benefit of intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. J Neurol Sci. 2001;189:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Chen J, Chen XG, et al. Human marrow stromal cell therapy for stroke in rat: neurotrophins and functional recovery. Neurology. 2002;59:514–23. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerdoni E, Gallo B, Casazza S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells efficiently modulate pathogenic immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitits. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:219–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Li Y, Chen J, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cell treatments improves neurological functional recovery in EAE mice. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chopp M, Zhang XH, Li Y, et al. Spinal cord injury in rat: treatment with bone marrow stromal cell transplantation. NeuroReport. 2000;11:3001–5. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009110-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarz EJ, Alexander GM, Prockop DJ, Azizi SA. Multipotential marrow stromal cells transduced to produce l-DOPA: engraftment in a rat model of Parkinson disease. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2539–49. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uccelli A, Pistoia V, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression? Trends Immunol. 2007;28:219–26. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolar J, Le Blanc K, Keating A, Blazar BR. Concise review: hitting the right spot with mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1446–55. doi: 10.1002/stem.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassis I, Grigoriadis N, Gowda-Kurkalli B, et al. Neuroprotection and immunomodulation with mesenchymal stem cells in chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:753–61. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohyeddin Bonab M, Yazdanbakhsh S, Lotfi J, et al. Does mesenchymal stem cell therapy help multiple sclerosis patients? Report of a pilot study. Iran J Immunol. 2007;4:50–7. doi: 10.22034/iji.2007.17180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamout B, Hourani R, Salti H, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;227:185–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karussis D, Karageorgiou C, Vaknin-Dembinsky A, et al. Safety and immunological effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1187–94. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barhum Y, Gai-Castro S, Bahat-Stromza M, Barzilay R, Melamed E, Offen D. Intracerebroventricular transplantation of human mesenchymal stem cells induced to secrete neurotrophic factors attenuates clinical symptoms in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;41:129–37. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai L, Lennon DP, Eaton V, et al. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells induce Th2-polarized immune response and promote endogenous repair in animal models of multiple sclerosis. Glia. 2009;57:1192–203. doi: 10.1002/glia.20841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uccelli A, Prockop DJ. Why should mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) cure autoimmune diseases? Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:768–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Xu F, Zhang C, et al. High MR sensitive fluorescent magnetite nanocluster for stem cell tracking in ischemic mouse brain. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:1009–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon D, Pavlovska G, Glover CP, Uney JB, Wraith D, Scolding NJ. Human mesenchymal stem cells abrogate experimental allergic encephalomyelitis after intraperitoneal injection, and with sparse CNS infiltration. Neurosci Lett. 2008;448:71–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breithaupt C, Schubart A, Zander H, Skerra A, Huber R, Linington C, Jacob U. Structural insights into the antigenicity of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133443100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pule M, Finney H, Lawson A. Artificial T-cell receptors. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:211–26. doi: 10.1080/14653240310001488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park TS, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA. Treating cancer with genetically engineered T cells. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:550–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fransson M, Piras E, Burman J, et al. CAR/FoxP3-engineered T regulatory cells target the CNS and suppress EAE upon intranasal delivery. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:112. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meisel R, Brockers S, Heseler K, et al. Human but not murine multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells exhibit antimicrobial effector function mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Leukemia. 2011;25:648–54. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johansson U, Rasmusson I, Niclou SP, et al. Formation of composite endothelial cell–mesenchymal stem cell islets: a novel approach to promote islet revasularization. Diabetes. 2008;57:2393–401. doi: 10.2337/db07-0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang Y, Zhu J, Xu G, Liu X. Intranasal delivery of stem cells to the brain. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8:623–32. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.566267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danielyan L, Schäfer R, von Ameln-Mayerhofer A, et al. Intranasal delivery of cells to the brain. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88:315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Velthoven CT, Kavelaars A, van Bel F, Heijnen CJ. Nasal administration of stem cells: a promising novel route to treat neonatal ischemic brain damage. Pediatr Res. 2010;68:419–22. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181f1c289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danielyan L, Schäfer R, von Ameln-Mayerhofer A, et al. Therputic efficacy of intranasally delivered mesenchymal stromal cells in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Rejuvenation Res. 2011;1:3–16. doi: 10.1089/rej.2010.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou Y, Ryo CH, Park KY, Kim SM, Jeong CH, Jeun SS. Effective combination of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and minocycline in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Stem Cell Res. 2013;4:77. doi: 10.1186/scrt228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Englund U, Björklund A, Wictorin K. Migration patterns and phenotypic differentiation of long-term expanded human neural progenitor cells after transplantation into the adult rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;134:123–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nern C, Wolff I, Macas J, et al. Fusion of hematopoietic cells with Purkinje neurons does not lead to stable heterokaryon formation under noninvasive conditions. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3799–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5848-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968–73. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kemp K, Gordon D, Wraith DC, et al. Fusion between human mesenchymal stem cells and rodent cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2010;37:166–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iglesias D, El-Kares R, Taranta A, et al. Stem cell microvesicles transfer cystinosin to human cystinotic cells and reduce cystine accumulation in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westin U, Piras E, Jansson B, et al. Transfer of morphine along the olfactory pathway to the central nervous system after nasal administration to rodents. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2005;24:565–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Illum L. Transport of drugs from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;11:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(00)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsushita T, Kibayashi T, Katayama T, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells transmigrate across brain microvascular endothelial cell monolayers through transiently formed inter-endothelial gaps. Neurosci Lett. 2011;502:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kopen GC, Prockop DJ, Phinney DG. Marrow stromal cells migrate throughout forebrain and cerebellum, and they differentiate into astrocytes after injection into neonatal mouse brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10711–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tolar J, Nauta AJ, Osborn MJ, et al. Sarcoma derived from cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:371–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernardo ME, Zaffaroni N, Novara F, et al. Human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells do not undergo transformation after long-term in vitro culture and do not exhibit telomere maintenance mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9142–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pockop DJ, Brenner M, Fibbe WE, et al. Defining the risks of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:576–8. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.507330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.