A recent court decision denying injured migrant farm workers health care after their work visas expire is only the latest attack on these workers’ health rights, according to advocates, who say these labourers die, are injured or are exposed to carcinogenic chemicals with impunity in Canada.

In mid-April, the Ontario Divisional Court ruled the province does not have to pay for health care for Denville Clarke and Kenroy Williams, two Jamaicans formerly employed by the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP).

Nearly 30 000 migrant workers come to Canada each year under the program, with the majority working in Ontario.

Clarke and Williams were injured in a 2012 crash while riding to work in their employer’s van, which they say didn’t have enough seat belts for all nine passengers. One worker was killed in the crash and the others were sent to their home countries, but Clarke and Williams stayed in Ontario to fight for compensation. Although all temporary farm workers are entitled to injury compensation, it’s woefully inadequate and nearly impossible to access after workers leave the country, according to Chris Ramsaroop, an organizer with advocacy group Justicia for Migrant Workers. Clarke and Williams say none of their fellow injured passengers have received any compensation.

Clarke said he can no longer turn his neck to the left and has pain that “shoots straight down my spine.” Williams reports frequent bouts of dizziness and often has to lie down when his pain becomes unbearable, because he can no longer afford medication. Although two earlier court decisions forced the Ontario government to provide provincial health coverage while the two seek injury compensation from the Workers’ Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB), the most recent decision cut them off as of Mar. 31. In court, the Ontario Health Ministry argued that a decision in Clarke and Williams’ favour would mean the government would have to pay for migrant workers’ health coverage “in perpetuity.” But Dr. Ritika Goel, a Toronto-based physician who lobbies for health care access for people living in Canada without status, called this concern “ridiculous.” The ministry could decide who to cover on a case-by-case basis, she noted. “It’s exceptional that migrant workers are injured here and need to stay.”

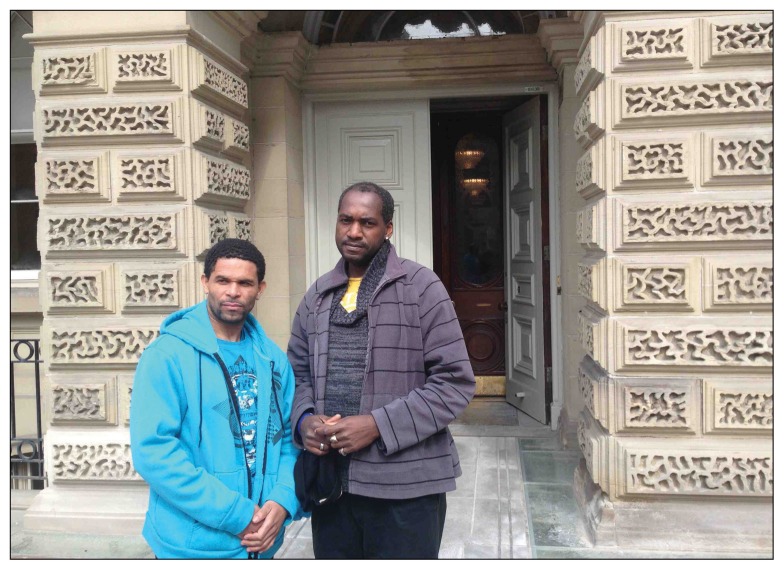

Migrant farm workers Kenroy Williams (left) and Denville Clarke (right) have been fighting for compensation since a 2012 crash.

Image courtesy of Justicia for Migrant Workers

“I feel pissed off … it feels like we are animals,” said Williams, a single father who can no longer afford school fees for his five children. He has earned $300 a week as a farm worker in Canada since 2006; back home in Jamaica, he can only find work as a driver, which pays $25 a week.

Paucity of data

Several government bodies were contacted regarding the rate of injury and death among migrant farm workers, to no avail. According to Janet McLaughlin, a researcher with the International Migration Research Centre, such information is not publicly available.

Foreign Agricultural Resource Management Services (F.A.R.M.S.), a private organization contracted by the federal government to administer the SAWP program in Ontario, does keep these numbers, but F.A.R.M.S. general manager Sue Williams wouldn’t release this data, citing “privacy reasons.”

A portion of the F.A.R.M.S. data was, however, submitted to the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal in 2012, after the family of Ned Peart, a Jamaican man who was crushed to death by a tobacco kiln in 2002, filed a complaint. It argued that Peart’s rights were violated because under the Ontario Coroner’s Act inquiries are automatically held into workers deaths’ in some sectors, but not in agriculture. There has never been an inquiry into the death of a migrant farm worker in Canada, said Ramsaroop. Peart’s family is still waiting for the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal to make a decision.

According to that data, between 1996 and 2011, 1198 migrant farm workers in Ontario were sent home for “medical reasons.” When an employer fires a worker or sends a worker home on medical grounds, they have no legal recourse to appeal, Ramsaroop added.

“Migrant farm workers’ rights are protected by the government liaison officer of their source country,” stated Jordan Sinclair, a spokesperson for Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, the federal government body that authorizes the SAWP program, in an email.

The liaison officers are expected to, among other regulatory tasks, inform workers of their rights (which includes the right to refuse unsafe work), inspect housing, ensure workers have health and injury insurance and act as an intermediary when employers terminate a worker, Sinclair wrote.

But advocates argue that the liaison officers’ role of upholding rights is thwarted by conflict of interest. The officers’ jobs and their country’s economy depend on maintaining their country’s spots in the temporary worker programs. Therefore, liaison officers strive to ensure their country’s workers are seen as agreeable in the eyes of employers.

“Each of the countries is competing for jobs,” said Ramsaroop. “They think of the contract first and the workers’ interest second.”

Interestingly, however, migrant workers are treated like Canadians in at least one respect: their injury compensation is cut off, often within a year, if, despite their injury, they are deemed able to work in another occupation with a comparable pay rate in Ontario, such as pumping gas — a practice known as “deeming.”

“Migrant workers are entitled to the same benefits as any worker in an Ontario workplace,” wrote Christine Arnott, public relations specialist for WSIB. When asked why a migrant worker who is only entitled to work in agriculture is treated as though they can work in any industry, Arnott replied, “We have provided you with all of the information we have.” Although Arnott couldn’t comment on any specific cases, Maryth Yachnin, the lawyer for Williams and Clarke in the provincial health care case, said Williams and Clarke were likely also cut off by WSIB because of deeming.

Workers used as “machines”

In addition to injuries related to road and farm equipment accidents, migrant workers also experience health problems stemming from pesticide exposure, cramped and isolated living conditions and the repetitive nature of their work. “The ones we see most often are musculoskeletal pain and injuries,” said McLaughlin. Most workers don’t demand reduced hours or modified work because of the precarious nature of their employment, she added. In late April, a worker informed Ramsaroop he’d been fired for refusing to work without gloves. Goel said workers are reluctant to report an injury or health concern, because they fear they could be sent home. “We’ve created really terrible power dynamics.”

In terms of chemical exposure, “people have thrown up, people have fainted, and we also see kidney failure,” Ramsaroop said, but it’s difficult for workers to prove the link between exposure and their symptoms. “The long-term effects are going to be years down the road.”

Mental health issues are also rife among migrant workers because of the lack of down-time and the alienating environment, added Goel. “You’re being watched at all times, you’re working 10 to 12 hours a day, seven days a week and you’re far away from all of your loved ones. We’re essentially using these people as machines.”

Although all migrant farm workers are entitled to health coverage for the duration of their work visas, access to health care is an issue. Workers must often rely on their employers for transportation to clinics and in some cases, are accompanied into the examination room by their boss, said Ramsaroop. Meanwhile, some employers delay registering their employees for health cards or illegally hold their employees’ health cards, he explained.

McLaughlin argues the treatment of migrant farm workers raises a major question for Canadians. “What kind of society are we living in where we bring workers here to work year after year and they pay their taxes, and then they suffer a major injury or illness and we refuse to help them in their time of need?”