Abstract

Background

Most nemerteans (phylum Nemertea) are free-living, but about 50 species are known to be firmly associated with other marine invertebrates. For example, Gononemertes parasita is associated with ascidians, and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila with barnacles. There are 12 complete or near-complete mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) sequences of nemerteans available in GenBank, but no mitogenomes of none free-living nemerteans have been determined so far. In the present paper complete mitogenomes of the above two parasitic/commensal nemerteans are reported.

Methods

The complete mitochondrial genomes (mitogenome) of G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila were amplified by conventional and long PCR. Phylogenetic analyses of maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) were performed with both concatenated nucleotide and amino acid sequences.

Results

Complete mitogenomes of G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila are 14742 bp and 14597 bp in size, respectively, which are within the range of published Hoplonemertea mitogenomes. Their gene orders are identical to that of published Hoplonemertea mitogenomes, but different from those of Palaeo- and Heteronemertea species. All the coding genes, as well as major non-coding regions (mNCRs), are AT rich, which is especially pronounced at the third codon position. The AT/GC skew pattern of the coding strand is the same among nemertean mitogenomes, but is variable in the mNCRs. Some slight differences are found between mitogenomes of the present species and other hoplonemerteans: in G. parasita the mNCR is biased toward T and C (contrary to other hoplonemerteans) and the rrnS gene has a unique 58-bp insertion at the 5′ end; in N. tetraclitophila the nad3 gene starts with the ATT codon (ATG in other hoplonemerteans). Phylogenetic analyses of the nucleotide and amino acid datasets show early divergent positions of G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila within the analyzed Distromatonemertea species, and provide strong support for the close relationship between Hoplonemertea and Heteronemertea.

Conclusion

Gene order is highly conserved within the order Monostilifera, particularly within the Distromatonemertea, and the special lifestyle of G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila does not bring significant variations to the overall structures of their mitogenomes in comparison with free-living hoplonemerteans.

Keywords: Nemertea, Gononemertes parasita, Nemertopsis tetraclitophila, Parasitic/Commensal, Mitochondrial genome, Phylogeny

Background

The phylum Nemertea (ribbon worm) includes about 1280 named species [1]. Most of them are free-living in marine, freshwater and terrestrial habitats, but there are about 50 species reported to be associated with other animals; host organisms include poriferans, cnidarians, bivalves, echiurans, crustaceans, echinoderms and ascidians. The position of Nemertea among metazoans was traditionally considered to be close to the acoelomate Platyhelminthes, but comparative ultrastructure studies and molecular phylogenetic analyses during recent decades have supported it to be a member of the Lophotrochozoa [2-6]. The phylogenetic relationship of the phylum is still unsettled in parts, and conclusions may be dependent on different markers and analytical methods [7-9]. A recent analysis based on four nuclear and two mitochondrial loci further suggested that an expanded taxon sampling at family and generic level was required for getting a better understanding of nemertean affinities [9].

To date, there are 12 complete or near-complete nemertean mitogenome sequences available in GenBank. From these, we can infer some interesting patterns in terms of genome organization. For instance, Palaeonemertea and Heteronemertea bear larger mitogenomes than the more recently diverged hoplonemertean taxon Distromatonemertea. The gene arrangement within the phylum is not conserved, but generally stable within each of the three major groups (Palaeo-, Hetero- and Hoplonemertea). Nevertheless, a fuller understanding of the evolutionary patterns of nemertean mitogenome evolution requires denser taxon sampling, particularly of taxa that have adopted unusual lifestyles, such as Malacobdella and Carcinonemertes. In the present study, we determined the first complete mitogenome sequences of two parasitic/commensal nemerteans, Gononemertes parasita Bergendal, 1900 and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila Gibson, 1990, which taxonomically belong to Monostilifera (a group that contains most known symbiotic nemerteans). G. parasita lives in the branchial chamber of some ascidians in European waters [10], whereas N. tetraclitophila has been recorded from the mantle cavity of the balanomorph barnacle Tetraclita squamosa (Bruguiére, 1789) in Hong Kong, China [11]. Worms of both species seem to be firmly associated with a host, and possess some adaptive features that might be related to none free-living lifestyle, e.g., the greater number of gonads than most free-living monostiliferans; the absence of a proboscis apparatus (G. parasita) [11,12]. Mostly based on reproductive adaptations, Roe has argued that G. parasita and another Nemertopis species living in barnacles (Nemertopis quadripunctata (Quoy & Gaimard, 1833), which feeds on the eggs of the barnacles and possibly on the barnacles themselves) should be regarded as parasites [13]. However, the ecology, particularly the feeding biology, of G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila has not been well understood. Therefore, the two species are cautiously mentioned as “parasitic/commensal” in the present paper.

Methods

Specimens and DNA extraction

Gononemertes parasita was collected from the branchial chamber of the sea squirt Ascidia obliqua Alder, 1863 near Tjärnö, Sweden. Nemertopsis tetraclitophila was collected from the mantle cavity of the barnacle Tetraclita squamosa in Shenzhen, China. For either species, total DNA was extracted from a single specimen using the Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (OMEGA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −20°C.

PCR amplification and sequencing

Small fragments such as cox1, rrnS-rrnL, cob and cox3 were amplified with universal primers, and then specific primers were designed for the amplification of long fragments (Additional file 1: Table S1). All PCR reactions were carried out in a reaction volume of 25 μl containing 12.5 μl Premix Taq (LA version 2.0) (TaKaRa Clone Tech), 0.5 μl each primer, 0.5 μl DNA template and 11 μl distilled H2O. The PCR amplifications were performed under the following conditions: 4 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 48–50°C (according to primers), 1–10 min (according to the length of products) at 72°C, followed by a 10 min elongation. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using DNA gel extraction kit (OMEGA). The purified PCR products were ligated into pEASY-T1 vector (Transgen, China) and sequenced by primer walking on an ABI 3730 Sequencer.

Genome assembly and annotation

All the sequences were compared with other nemerteans to prevent contaminations from a host or bacteria. The obtained fragments of mitogenomes were assembled with Codoncode Aligner 5.0.1. Identification of protein-coding genes and rRNA genes was performed by BLAST searches (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) and by alignment to known hoplonemertean mitogenomes. Most tRNA genes were identified by tRNAscan-SE 1.21 [14], and additional tRNA genes were inferred with RNAfold [15]. The mitogenome was visualized using CGView [16]. The nucleotide composition and codon usage were calculated with DAMBE 5 [17]. Multiple alignments of genes were generated by Clustal X [18] with default settings and amino acid translation was carried out using MEGA 5.0 [19]. The full mitogenome sequences of Gononemertes parasita [KF572481] and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila [KF572482] were submitted to GenBank and compared with Cephalothrix hongkongiensis [NC_012821], Cephalothrix sp. [NC_014869], Iwatanemertes piperata [KF719984], Lineus viridis [NC_012889], Lineus alborostratus [NC_018356], Nectonemertes cf. mirabilis [NC_017874], Amphiporus formidabilis [KC710979], Emplectonema gracile [NC_016952], Paranemertes cf. peregrina [NC_014865], Zygeupolia rubens [NC_017877], Prosadenoporus spectaculum [KC710980] and Nipponnemertes punctatula [KC710981].

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analyses of the 14 available nemertean mitogenomes were carried out as follows: i) nucleotide-level analysis of protein-coding genes, with 3rd codon position removed; ii) nucleotide-level analysis of protein-coding genes, with 3rd codon position removed, rRNA and tRNA genes, iii) amino acid-level analysis of protein-coding genes. The saturation test was carried out based on the transition and transversion substitutions vs. the Tamura-Nei (TN93) distance of three codon positions by DAMBE 5 [17], and the third codon position which tended to be saturated (the transition and transversion substitution values do not increase as the genetic distance increase) was not used in phylogenetic analyses. The outgroups Katharina tunicata [NC_001636] and Terebratulina retusa [NC_000941] were selected based on their close relationships with Nemertea in previous studies [20,21]. All datasets were aligned with Clustal X with default settings [18]. Poorly aligned positions were excluded using Gblocks Version 0.91b [22] allowing less strict flanking positions and other default parameters. For nucleotide sequences MODELTEST [23] and MRMODELTEST [24], and for amino acid sequences ProtTest 2.4 [25] were used to select the best-fit substitution models (the model parameters were estimated when the concatenated nucleotides/amino acids were treated as a single partition). Based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the best-fit model for nucleotides was the GTR + I + G and for amino acid sequences was the MtRev + G + F. The ML analysis was performed with PHYML 3.0 program (http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/phyml/) [26] with 100 bootstrap replicates. Bayesian inference was conducted using MrBayes version 3.1.2 [27]. Four Monte Carlo Markov chains (MCMC) were run for 1,000,000 generations, sampling every 100 generations. The first 2500 trees were omitted as burn-in. To ensure convergence, the run was not ended until the average standard deviation of split frequencies reached <0.01 and the PSRF values were close to 1 for all parameters. To investigate the contribution of different genes, the nucleotide data matrix containing the 1st and 2nd codon positions, rRNA and tRNA sequences was subjected to a heuristic parsimony analysis (i.e. hsearch addseq = random nreps = 1000 swap = TBR multrees = yes start = stepwise) in PAUP* 4.0 [28] and TreeRot.v3 [29] was used to calculate the partitioned Bremer support (PBS) values [30,31] of each gene partition on the tree nodes.

Results and discussion

Genome organization and base composition

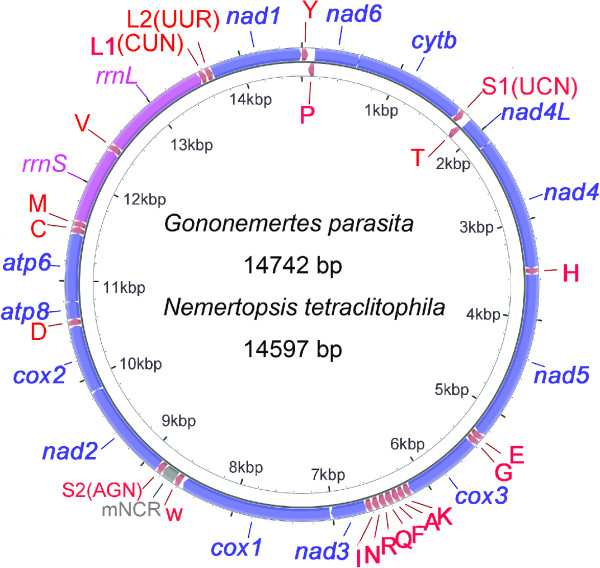

As observed in the previously determined Hoplonemertea mitogenomes, both of the present mitogenomes also include 13 protein-coding genes, two rRNAs and 22 tRNAs genes, all encoded on the coding strand except for trnP and trnT (Figure 1 and Table 1). The gene orders are identical to previously published hoplonemertean mitogenomes without exceptions. There are several overlaps throughout the two mitogenomes, for example, the 8-bp overlaps between nad6 and cob (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Map of the mitochondrial genomes of Gononemertes parasita and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila. Genes coded on the coding strand are arranged clockwise; those on the other strand are counter-clockwise. Thirteen protein-coding genes are shown in blue and two ribosomal RNA genes in pink. Transfer RNA genes are labeled by their single letter of corresponding amino acids. Major non-coding regions (mNCR) are represented in grey.

Table 1.

The mitochondrial genome organization of Gononemertes parasita and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila

|

Genes |

Gononemertes parasita

|

Nemertopsis tetraclitophila

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From 5′ to 3′ | Size (bp) | Start codon | Stop codon | 3′ spacer | From 5′ to 3′ | Size (bp) | Start codon | Stop codon | 3′ spacer | |

|

trnY |

1-66 |

66 |

|

|

1 |

1-63 |

63 |

|

|

9 |

|

trnPa |

133-68 |

66 |

|

|

3 |

138-73 |

66 |

|

|

8 |

|

nad6 |

137-604 |

468 |

ATG |

TAG |

−8 |

147-605 |

459 |

ATG |

TAG |

−8 |

|

Cob |

597-1733 |

1137 |

ATG |

TAA |

5 |

598-1734 |

1137 |

ATG |

TAG |

−1 |

|

trnS1(UCN) |

1739-1797 |

59 |

|

|

0 |

1734-1798 |

65 |

|

|

0 |

|

trnTa |

1862-1798 |

65 |

|

|

4 |

1860-1799 |

62 |

|

|

2 |

|

nad4L |

1867-2169 |

303 |

GTG |

TAA |

−7 |

1863-2165 |

303 |

ATG |

TAG |

−11 |

|

nad4 |

2163-3497 |

1335 |

ATG |

TAG |

23 |

2155-3504 |

1350 |

ATG |

TAA |

15 |

|

trnH |

3521-3590 |

70 |

|

|

0 |

3520-3581 |

62 |

|

|

0 |

|

nad5 |

3591-5324 |

1734 |

GTG |

TAG |

−10 |

3582-5304 |

1723 |

ATG |

T |

0 |

|

trnE |

5315-5381 |

67 |

|

|

6 |

5305-5368 |

64 |

|

|

2 |

|

trnG |

5388-5451 |

64 |

|

|

2 |

5371-5434 |

64 |

|

|

1 |

|

cox3 |

5454-6233 |

780 |

ATG |

TAG |

7 |

5436-6215 |

780 |

ATG |

TAG |

5 |

|

trnK |

6241-6309 |

69 |

|

|

0 |

6221-6281 |

61 |

|

|

−1 |

|

trnA |

6310-6373 |

64 |

|

|

0 |

6281-6344 |

64 |

|

|

5 |

|

trnF |

6374-6439 |

66 |

|

|

10 |

6350-6413 |

64 |

|

|

9 |

|

trnQ |

6450-6518 |

69 |

|

|

0 |

6423-6493 |

71 |

|

|

3 |

|

trnR |

6519-6583 |

65 |

|

|

8 |

6497-6560 |

64 |

|

|

2 |

|

trnN |

6592-6657 |

66 |

|

|

7 |

6563-6626 |

64 |

|

|

0 |

|

trnI |

6665-6729 |

65 |

|

|

1 |

6627-6690 |

64 |

|

|

7 |

|

nad3 |

6731-7084 |

354 |

ATG |

TAA |

1 |

6698-7040 |

343 |

ATT |

T |

0 |

|

cox1 |

7086-8621 |

1536 |

ATG |

TAA |

28 |

7041-8576 |

1536 |

ATG |

TAG |

33 |

|

trnW |

8650-8718 |

69 |

|

|

0 |

8610-8676 |

67 |

|

|

0 |

| mNCRb |

8719-8838 |

120 |

|

|

0 |

8677-8813 |

137 |

|

|

0 |

|

trnS2(AGN) |

8839-8905 |

67 |

|

|

−1 |

8814-8880 |

67 |

|

|

0 |

|

nad2 |

8905-9901 |

997 |

GTG |

T |

11 |

8881-9877 |

997 |

ATG |

T |

0 |

|

cox2 |

9913-10596 |

684 |

ATG |

TAG |

7 |

9878-10564 |

687 |

ATG |

TAA |

−2 |

|

trnD |

10604-10668 |

65 |

|

|

0 |

10563-10629 |

67 |

|

|

0 |

|

atp8 |

10669-10839 |

171 |

GTG |

TAG |

7 |

10630-10797 |

168 |

GTG |

TAG |

5 |

|

atp6 |

10847-11539 |

693 |

ATG |

TAG |

6 |

10803-11489 |

687 |

ATG |

TAG |

−2 |

|

trnC |

11546-11612 |

67 |

|

|

0 |

11488-11548 |

61 |

|

|

0 |

|

trnM |

11613-11676 |

64 |

|

|

0 |

11549-11611 |

63 |

|

|

0 |

|

rrnS |

11677-12513 |

837 |

|

|

0 |

11612-12384 |

773 |

|

|

0 |

|

trnV |

12514-12578 |

65 |

|

|

0 |

12385-12450 |

66 |

|

|

0 |

|

rrnL |

12579-13686 |

1108 |

|

|

0 |

12451-13540 |

1090 |

|

|

0 |

|

trnL1(CUN) |

13687-13750 |

64 |

|

|

5 |

13541-13606 |

66 |

|

|

4 |

|

trnL2(UUR) |

13756-13818 |

63 |

|

|

0 |

13611-13673 |

63 |

|

|

0 |

| nad1 | 13819-14739 | 921 | GTG | TAA | 3 | 13674-14594 | 921 | GTG | TAG | 3 |

athe genes coded on the opposite strand.

bmNCR represents the major non-coding region.

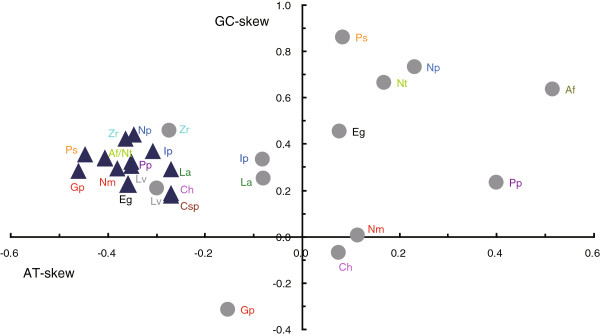

The nucleotide composition of the coding strand is biased toward T and A in these two mitogenomes, as is the case in most metazoan mitogenomes [32]. The A + T content of the coding strands in G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila is 68.8% and 71.2% respectively, which falls within the range of the previously sequenced nemertean mitogenomes (from 64.7% in Lineus alborostratus to 75.7% in Cephalothrix sp.) (Table 2). The A + T biased composition is particularly pronounced at the third codon position of the protein-coding genes (75.4% and 82.5%, respectively). The coding strands bear several poly-T stretches with the longest one being 20 Ts in G. parasita and 33 Ts in N. tetraclitophila, which have proved to be detrimental to PCR amplification [33,34]. Among lophotrochozoans, AT- and GC skews always show high inter- or intra-phylum variation, which might affect phylogenetic analyses [35]. The nucleotide skewness for the coding strands of N. tetraclitophila (AT-skew = −0.41, GC-skew = 0.34) and G. parasita (AT-skew = −0.46, GC-skew = 0.28) is biased toward T and G. A similar trend has been observed in other Nemertea mitogenomes (Figure 2): the negative AT-skew ranges from −0.46 (G. parasita) to −0.27 (Cephalothrix sp., C. hognkongiensis and L. alborostratus) and the GC-skew is always positive varying from 0.18 (Cephalothrix sp.) to 0.44 (N. punctatula). It is noteworthy that the nucleotide skews of the mNCRs are different among species (Figure 2), which reflects the relatively higher variability of mNCR. The mNCR of G. parasita is biased toward T and C, which is contrary to other hoplonemerteans.

Table 2.

Nucleotide compositions of Gononemertes parasita (Gp) and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila (Nt) mitogenomes

|

Feature |

Length (bp) |

A (%) |

C (%) |

G (%) |

T (%) |

A + T (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gp | Nt | Gp | Nt | Gp | Nt | Gp | Nt | Gp | Nt | Gp | Nt | |

| Coding strand |

14742 |

14597 |

18.6 |

21.1 |

11.2 |

9.5 |

20.0 |

19.3 |

50.3 |

50.0 |

68.8 |

71.2 |

| Protein-coding genesa |

11076 |

11058 |

15.8 |

18.1 |

11.5 |

9.6 |

20.4 |

19.6 |

52.3 |

52.8 |

68.1 |

70.9 |

| 1st codon position |

3692 |

3686 |

18.0 |

20.2 |

12.6 |

11.5 |

25.2 |

25.0 |

44.3 |

43.2 |

62.2 |

63.5 |

| 2nd codon position |

3692 |

3686 |

14.8 |

16.1 |

16.1 |

15.2 |

17.4 |

18.2 |

51.8 |

50.5 |

66.6 |

66.6 |

| 3rd codon position |

3692 |

3686 |

14.6 |

17.9 |

6.0 |

2.1 |

18.6 |

15.4 |

60.8 |

64.6 |

75.4 |

82.5 |

| tRNA genes |

1445 |

1418 |

29.4 |

32.0 |

10.2 |

10.4 |

20.8 |

19.7 |

39.6 |

37.9 |

69.0 |

70.0 |

|

rrnL gene |

1108 |

1090 |

26.7 |

28.6 |

9.8 |

8.9 |

17.5 |

17.6 |

45.9 |

45.0 |

72.7 |

73.6 |

|

rrnS gene |

837 |

773 |

24.9 |

30.0 |

10.0 |

9.2 |

19.1 |

18.0 |

46.0 |

42.8 |

70.9 |

72.8 |

| mNCR | 120 | 137 | 30.0 | 43.1 | 19.2 | 4.4 | 10.0 | 21.9 | 40.8 | 30.7 | 70.8 | 73.7 |

aexcluding stop codons.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of AT- and GC-skews in 14 nemertean species. Values were calculated for the coding strand of the overall mitogenome sequences (▲) and the major non-coding region (Cephalothrix sp. not included because the major non-coding region of this species is incomplete) (●). AT-skew = (A-T)/(A + T); GC-skew = (G-C)/(G + C). Af = Amphiporus formidabilis, Ch = Cephalothrix hongkongiensis, Csp = Cephalothrix sp., Eg = Emplectonema gracile, Ip = Iwatanemertes piperata, Gp = Gononemertes parasita, Lv = Lineus viridis, La = Lineus alborostratus, Nt = Nemertopsis tetraclitophila, Np = Nipponnemertes punctatula, Nm = Nectonemertes cf. mirabilis, Ps = Prosadenoporus spectaculum, Pp = Paranemertes cf. peregrina, Zr = Zygeupolia rubens.

Protein-coding genes

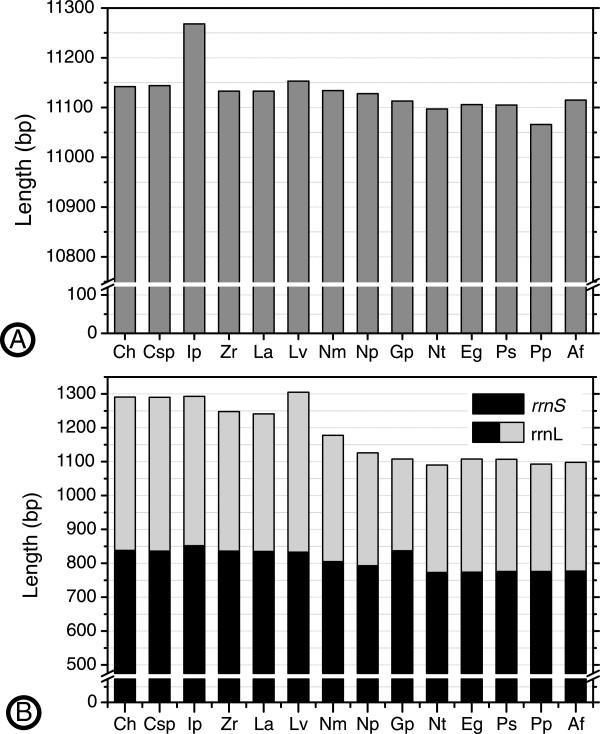

The canonical start codons ATG and GTG are used in most protein-coding genes of the G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila mitogenomes. An exceptional case is the nad3 gene of N. tetraclitophila, which was inferred to be initiated by the ATT codon (Table 1), and its length (343 bp) is shorter than that of other Monostilifera species (354 bp). Nonstandard initiation codons were also inferred in previously sequenced nemertean mitogenomes, e.g., the cox1 (TCT) of Cephalothrix sp. and C. hongkongiensis. The majority of the protein-coding genes appear to use the stop codons TAA or TAG, except that the nad5, nad3 and nad2 genes in N. tetraclitophila and the nad2 gene in G. parasita use a single T as the termination codon, most of which are adjacent to a protein-coding gene and occasionally a tRNA gene (Table 1). The incomplete termination codon T has been proposed to be converted into the complete stop codon TAA through polyadenylation during posttranscriptional mRNA processing [36]. The overall length of protein-coding genes in the known nemertean mitogenomes varies from 11066 to 11268 bp. The protein-coding genes in seven Monostilifera mitogenomes are shorter than that in the other nemerteans (Figure 3A). The two present mitogenomes do not exhibit apparent length change compared to other hoplonemertean mitogenomes, unlike in some parasitic insects whose protein-coding gene sizes are significantly smaller than those of free-living ones [37].

Figure 3.

Length comparisons of protein-coding genes (A) and ribosomal RNA genes (B) among 14 nemertean mitogenomes. Abbreviations of species names see Figure 2.

The overall nucleotide composition of 13 protein-coding genes in G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila mitogenomes are AT biased (68.1% and 70.9%, respectively). For both species, the third codon position has a considerably higher AT content (75.4% and 82.5%, respectively) than the first and second codon positions and the lowest content of C (Table 2). According to the analysis of relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU), the two- and four-fold degenerate codons prefer the one ending with T (Additional file 2: Table S2), for example, GCT (2.811) is more frequently used than the other three codons (0.297-0.486) for Ala. Corresponding to the high percentage of T in both mitogenomes, the most frequently used codon is TTT (17.6% and 16.3%, respectively), and Phe is the most frequently used amino acid (19.2% and 16.8%, respectively) (Additional file 2: Table S2). The other preferred amino acids in both species are Leu, Val, Gly and Ser, all of which might be associated with transmembrane functions. Similar codon usage and amino acid composition patterns have been observed in previously sequenced Nemertea mitogenomes [38].

Ribosomal and transfer RNA genes

The ribosomal RNA genes (rrnL and rrnS) are located at the same location as in other nemertean mitogenomes, separated by trnV. The rrnL gene is 1,108 bp in G. parasita and 1,090 bp in N. tetraclitophila, and the A + T contents are 72.7% and 73.6%, respectively. The rrnS gene is 837 bp and 773 bp, and the A + T content is 70.9% and 72.8%, respectively (Table 2). At the 5′ end of rrnS gene in G. parasita, there is a region of 58 bp (TGTTTATTGGTATATTTTGATAAGTACTTTTAGTTTTATTCTATTTTTTTTCTTGTTT), which can neither be aligned with other nemertean rrnS sequences nor does it show any similarity with any remaining parts of the mitogenome, making the rrnS gene in G. parasita the longest among enoplan mitogenomes (Figure 3B). This insertion is also one major reason that G. parasita bears the largest mitogenome within Distromatonemertea. Except for rrnS of G. parasita, the rRNA genes of monostiferans are apparently shorter than that of other nemerteans (Figure 3B).

A + T contents in the tRNA genes is slightly lower than in the remainder of the mitogenomes. The anticodons of 22 tRNAs in both mitogenomes are the same as in other hoplonemerteans. All tRNA genes can be folded into conventional cloverleaf-like structures, except for trnS1(UCN) and trnS2(AGN) of G. parasita, and trnS2(AGN) of N. tetraclitophila. The structures of trnS2 of both species conform to the secondary structure achieved for known hoplonemertean mitogenomes, all lacking a DHU-arm which is replaced by a DHU-loop [38,39]. trnS1 of G. parasita was inferred to be 59 bp, which makes it one of the shortest known tRNA genes of nemerteans. It has a 5-T DHU-loop instead of a DHU-arm. Uncanonical secondary structures of tRNA genes occur frequently during animal evolution [40].

Non-coding regions

There are a total of 265 bp and 250 bp non-coding nucleotides throughout the mitogenomes of G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila, accounting for 1.8% and 1.7% of the whole mitogenomes, respectively. The mNCRs are 120 bp and 137 bp, respectively, both located between trnW and trnS2. The A + T content (70.8% and 73.7%) of both mNCRs is slightly higher compared with the whole coding strands, but not as high as that of the third codon position (Table 2). Besides poly-T/C/G stretches, the two mNCRs have a similarity of 33%, which reflects a rapid evolutionary rate. Tandem repeats like those in Amphiporus formidabilis and Nipponnemertes punctatula[41] are not detected. In both, N. tetraclitophila and G. parasita, the mNCRs have the potential to fold into hairpin-like structures at the 5′ end (not shown), which might be involved in the beginning of replication and transcription [42]. The second longest mNCRs in the mitogenomes of N. tetraclitophila and G. parasita are both located between cox1 and trnW (33 bp and 28 bp, respectively), in agreement with other Monostilifera species [41].

Phylogenetic analysis

The concatenated datasets for amino acid and nucleotide sequences of the 13 protein-coding genes (excluding the 3rd codon position) yielded 3,056 and 6,721 aligned sites, respectively. The third dataset (comprising 8,962 nucleotide sites) was constructed by adding informative rRNA and tRNA gene sites to the above nucleotide dataset, which can help avoid directional migration resulting from only using protein-coding genes [43]. According to the Partitioned Bremer support (PBS) analysis [30], the rRNA and tRNA sequences contribute 17.7% and 11.7% (Table 3) of phylogenetic signal, respectively, making them promising for phylogenetic analysis.

Table 3.

Partitioned Bremer support values for each gene partition on the combined tree nodes in Figure4B

| Gene | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | Total BS | BS contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st codon position |

181 |

86 |

1 |

13 |

43 |

16.5 |

−2 |

26 |

30 |

2 |

15 |

411.5 |

33.7 |

| 2nd codon position |

141 |

86 |

30.3 |

6 |

99 |

2.5 |

7 |

41 |

26 |

12 |

1 |

451.8 |

36.9 |

| rRNA |

98 |

19 |

7.7 |

0 |

40 |

8.5 |

18 |

22 |

5 |

−5 |

3 |

216.2 |

17.7 |

| tRNA |

64 |

18 |

9 |

0 |

38 |

1.5 |

−7 |

7 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

143.5 |

11.7 |

| Total | 484 | 209 | 48 | 19 | 220 | 29 | 16 | 96 | 64 | 14 | 24 |

The partitioned Bremer support values for each node add up to the total Bremer support (BS) values.

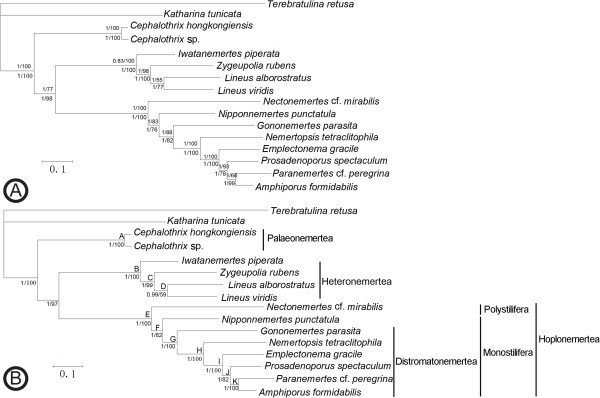

Based on these three datasets, ML and BI analyses yielded identical tree topologies (Figure 4). All of them support the hypothesis that Hoplonemertea has a closer relationship with Heteronemertea than with Palaeonemertea, represented here by two Cephalothrix species that form the earliest divergent clade with high bootstrap values and posterior probabilities. As documented in previous studies [7,44], Polystilifera (Nectonemertes cf. mirabilis) is the sister group to Monostilifera; Nipponnemertes is sister to the other monostiliferans which make up the group Distromatonemertea [8]. The two present taxa, G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila, exhibit early divergent positions in the analyzed Distromatonemertea species. A recent analysis based on data of six genes also placed G. parasita in a basal Distromatonemertea clade containing mostly symbiotic and terrestrial species [9], whereas it was placed at a different position in the phylogenetic analysis of cox1 and 18S rRNA sequences [45]. No similar species of the genus Nemertopsis have been studied in previous phylogenetic analyses. The position of the congeneric free-living species, Nemertopsis bivittata, was more or less different in previous analyses [8,9] and seems to be different from the placement of N. tetraclitophila in the present study, which calls for further studies about the interrelationships within the genus Nemertopsis.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees resulting from maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference. A. Nucleotide sequences (3rd codon position removed)/amino acid sequences of 13 protein-coding genes (same tree topology obtained from the both datasets). B. Nucleotide sequences (3rd codon position removed) of protein-coding genes, rRNA and tRNA sequences. Numbers at the nodes correspond to posterior probabilities (left) and bootstrap proportions (right) (in tree A, the upper values are those of the nucleotide tree and the lower ones are those of the amino acid tree). Capital letters (A to K) in tree B correspond to the nodes for which Bremer support values were calculated (see Table 3).

Conclusions

The complete mitochondrial genomes of Gononemertes parasita and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila, both of which possess some morphological characteristics adaptive to their lifestyle, are 14742 bp and 14597 bp, respectively. They are identical to the previously published mitogenomes of free-living hoplonemerteans in gene content and gene order, and have similar patterns in nucleotide richness and skewness. The length of whole genomes, as well as protein-coding genes and ribosomal RNA genes, is relatively conservative within Distromatonemertea and shorter (with the exception of the rrnS of G. parasita) than that of the other nemerteans. As in other hoplonemerteans, the coding strands of the present two mitogenomes bear some poly-T stretches; the tRNA genes usually exhibit cloverleaf-like structure except for trnS; the major non-coding regions exhibit AT-rich and hairpin-like structures that may be involved in transcription and replication. Some differences are found between the present mitogenomes and other hoplonemertean mitogenomes. For example, in G. parasita the mNCR is biased toward T and C (contrary to that in other hoplonemerteans) and the rrnS gene has a unique 58-bp insertion at 5′ end, and in N. tetraclitophila the nad3 gene starts with the ATT codon (ATG in other hoplonemerteans). However, we cannot conclude that these differences are related to their special lifestyle, because similar variations may also exist among free-living nemerteans and available mitogenomic data of nemerteans are stilled limited. Phylogenetic analyses show that both G. parasita and N. tetraclitophila are early divergent within the analyzed Distromatonemertea species.

Abbreviations

atp6 and atp8: ATP synthase subunits 6 and 8; cytb: Cytochrome b; cox1-3: Cytochrome c oxidase subunits I-III; nad1-6 and nad4L: NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1–6 and 4 L; rrnL and rrnS: The large and small subunits of ribosomal RNA; trnX: Transfer RNA molecules with the one-letter code of corresponding amino acid; DHU: Dihydrouridine; mNCR: Major non-coding region; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; bp: Base pair.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

S-CS conceived and designed the study. W-YS and D-LX performed the experiments. W-YS, D-LX and WS analyzed the data. MS, PS and S-CS collected and identified specimens. WY-S drafted the manuscript. S-C S, H-XC and PS revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

PCR primers used to amplify the mitochondrial genomes of Gononemertes parasita and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila.

Percentage of codon usage and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of the 13 protein-coding genes in the mitogenomes of Gononemertes parasita (Gp) and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila (Nt).

Contributor Information

Wen-Yan Sun, Email: swy8710@163.com.

Dong-Li Xu, Email: xudl@163.com.

Hai-Xia Chen, Email: chen_hai_xia@126.com.

Wei Shi, Email: kcool@126.com.

Per Sundberg, Email: p.sundberg@zool.gu.se.

Malin Strand, Email: malin.strand@artdata.slu.se.

Shi-Chun Sun, Email: sunsc@ouc.edu.cn.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31172046; 30970333). We are grateful to Mr. Hai-Lin Shen for assistance in collecting specimens.

References

- Kajihara H, Chernyshev AV, Sun S-C, Sundberg P, Crandall FB. Checklist of nemertean genera and species published between 1995–2007. Species Div. 2008;13:245–274. [Google Scholar]

- Turbeville JM, Field KG, Raff RA. Phylogenetic position of phylum Nemertini, inferred from 18S rRNA sequences: molecular data as a test of morphological character homology. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:235–249. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamaneck Y, Halanych KM. Lophotrochozoan phylogeny assessed with LSU and SSU data: evidence of lophophorate polyphyly. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;40:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn CW, Hejnol A, Matus DQ, Pang K, Browne WE, Smith SA, Seaver E, Rouse GW, Obst M, Edgecombe GD, Sørensen MV, Haddock SH, Schmidt-Rhaesa A, Okusu A, Kristensen RM, Wheeler WC, Martindale MQ, Giribet G. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature. 2008;452:745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature06614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlowski L, Braband A, Struck TH, von Dohren J, Bartolomaeus T. Phylogeny and mitochondrial gene order variation in Lophotrochozoa in the light of new mitogenomic data from Nemertea. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:364. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbeville JM. An ultrastructural analysis of coelomogenesis in the hoplonemertine Prosorhochmus americanus and the polychaete Magelona sp. J Morphol. 1986;187:51–60. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051870105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg P, Turbeville JM, Lindh S. Phylogenetic relationships among higher Nemertean (Nemertea) Taxa inferred from 18S rDNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2001;20:327–334. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thollesson M, Norenburg JL. Ribbon worm relationships: a phylogeny of the phylum Nemertea. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270:407–415. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade SCS, Strand M, Schwartz M, Chen HX, Kajihara H, Von Döhren J, Sun SC, Junoy J, Thiele M, Norenburg JL, Turbeville JM, Giribet G, Sundberg P. Disentangling ribbon worm relationships: multi-locus analysis supports traditional classification of the phylum Nemertea. Cladistics. 2012;28:141–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand M, Samuelsson H, Sundberg P. Nationalnyckeln till Sveriges flora och fauna. Stjärnmaskar − slemmaskar. Sipuncula − Nemertea. Uppsala: ArtDatabanken, SLU; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson R. In: Proceedings of the Second International Marine Biological Workshop: the Marine Flora and Fauna of Hong Kong and Southern China, 1986. Volume 1. Morton B, editor. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 1990. The macrobenthic nemertean fauna of Hong Kong; pp. 33–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bergendal D. Über ein Paar sehr eigenthümliche nordische Nemertinen. Zoologischer Anzeiger. 1900;23:313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Roe P. Ecological implications of the reproductive biology of symbiotic nemerteans. Hydrobiologia. 1988;156:13–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00027973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denman RB. Using RNAFOLD to predict the activity of small catalytic RNAs. Biotechniques. 1993;15:1090–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JR, Stothard P. The CGView server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W181–W184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. DAMBE5: a comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1720–1728. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek A, Tobergte S, Nesnidal MP, Purschke G, Struck TH. Mitochondrial genomes to the rescue - diurodrilidae in the myzostomid trap. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;68:312–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöger I, Schrodl M. Mitogenomics does not resolve deep molluscan relationships (yet?) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;69:376–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56:564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander JAA. MrModeltest v2. Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University; 2004. [ http://www.abc.se/] [Google Scholar]

- Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D. ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2104–2105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. Book PAUP* – Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Ver. 4.0. [Computer software and manual] Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1999. PAUP* – Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Ver. 4.0. [Computer software and manual]. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- TreeRot version 3. [ http://people.bu.edu/msoren/TreeRot.html]

- Bremer K. The limits of amino acid sequence data in angiosperm phylogenetic reconstruction. Evolution. 1988;42:795–803. doi: 10.2307/2408870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer K. Branch support and tree stability. Cladistics. 1994;10:295–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1994.tb00179.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanin A, Leger N, Deutsch J. Evidence for multiple reversals of asymmetric mutational constraints during the evolution of the mitochondrial genome of metazoa, and consequences for phylogenetic inferences. Syst Biol. 2005;54:277–298. doi: 10.1080/10635150590947843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riepsamen AH, Gibson T, Rowe J, Chitwood DJ, Subbotin SA, Dowton M. Poly(T) variation in heteroderid nematode mitochondrial genomes is predominantly an artefact of amplification. J Mol Evol. 2011;72:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s00239-010-9414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson T, Farrugia D, Barrett J, Chitwood DJ, Rowe J, Subbotin S, Dowton M. The mitochondrial genome of the soybean cyst nematode, Heterodera glycines. Genome. 2011;54:565–574. doi: 10.1139/g11-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesnidal MP, Helmkampf M, Bruchhaus I, Hausdorf B. The complete mitochondrial genome of Flustra foliacea (Ectoprocta, Cheilostomata) - compositional bias affects phylogenetic analyses of lophotrochozoan relationships. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:572. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojala D, Montoya J, Attardi G. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature. 1981;290:470–474. doi: 10.1038/290470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon DP, Hayward A, Kathirithamby J. The mitochondrial genome of the ‘twisted-wing parasite’ Mengenilla australiensis (Insecta, Strepsiptera): a comparative study. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:603. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HX, Sun SC, Sundberg P, Ren WC, Norenburg JL. A comparative study of nemertean complete mitochondrial genomes, including two new ones for Nectonemertes cf. mirabilis and Zygeupolia rubens, may elucidate the fundamental pattern for the phylum Nemertea. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HX, Sundberg P, Wu HY, Sun SC. The mitochondrial genomes of two nemerteans, Cephalothrix sp. (Nemertea: Palaeonemertea) and Paranemertes cf. peregrina (Nemertea: Hoplonemertea) Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:4509–4525. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser RB, Jabbar A, Mohandas N, Hoglund J, Hall RS, Littlewood DT, Jex AR. Assessment of the genetic relationship between Dictyocaulus species from Bos taurus and Cervus elaphus using complete mitochondrial genomic datasets. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:241. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun WY, Sun SC. A description of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Amphiporus formidabilis. Mol Biol Rep, in press: Prosadenoporus spectaculum and Nipponnemertes punctatula (Nemertea: Hoplonemertea: Monostilifera); doi:10.1007/s11033-014-3438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnason E, Rand DM. Heteroplasmy of short tandem repeats in mitochondrial DNA of Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua. Genetics. 1992;132:211–220. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa Y, Nishida M. Sequence evolution of mitochondrial tRNA genes and deep-branch animal phylogenetics. J Mol Evol. 1993;37:380–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00178868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg P, Chernyshev AV, Kajihara H, Kanneby T, Strand M. Character-matrix based descriptions of two new nemertean (Nemertea) species. Zool J Linn Soc. 2009;157:264–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00514.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Junoy J, Andrade SCS, Giribet G. Phylogenetic placement of a new hoplonemertean species commensal on ascidians. Invertebr Syst. 2010;24:616–629. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PCR primers used to amplify the mitochondrial genomes of Gononemertes parasita and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila.

Percentage of codon usage and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of the 13 protein-coding genes in the mitogenomes of Gononemertes parasita (Gp) and Nemertopsis tetraclitophila (Nt).