Abstract

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are emerging as key regulators of embryogenesis. They control embryonic gene expression by several means, ranging from microRNA-induced degradation of mRNAs to long ncRNA-mediated modification of chromatin. Many aspects of embryogenesis seem to be controlled by ncRNAs, including the maternal–zygotic transition, the maintenance of pluripotency, the patterning of the body axes, the specification and differentiation of cell types and the morphogenesis of organs. Drawing from several animal model systems, we describe two emerging themes for ncRNA function: promoting developmental transitions and maintaining developmental states. These examples also highlight the roles of ncRNAs in ensuring a robust commitment to one of two possible cell fates.

The discoveries of the microRNA (miRNA) lin-4 in nematode patterning1,2 and the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) Xist in mammalian X chromosome inactivation3–5 were milestones in molecular and developmental biology. Regulatory roles for RNAs had been postulated previously6,7, but lin-4 and Xist were initially regarded as rare exceptions to the rule that proteins are the main regulators of gene expression. In the past 10 years, however, genome-wide transcriptome analyses have revealed the presence of thousands of non-coding transcripts (reviewed in REFS 8–10). Members of this diverse group of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as regulators of almost every aspect of biology (reviewed in REFS 11–13).

ncRNAs comprise a diverse group of transcripts including ‘housekeeping’ ncRNAs (ribosomal RNA, transfer RNA, small nuclear RNA and small nucleolar RNA), regulatory ncRNAs and several other poorly characterized types of ncRNAs (for example, ncRNAs that originate from regulatory elements (reviewed in REFS 9,10)) (Supplementary information S1 (table)). Regulatory ncRNAs can be broadly classified according to their sizes as small ncRNAs (<200 bp; for example, miRNAs, endogenous small interfering RNAs (endo-siRNAs) and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs)) and lncRNAs (for example, large intergenic ncRNAs (lincRNAs)). Members of both classes are known for their ability to regulate gene expression by a wide range of mechanisms. For example, miRNAs can act at the RNA level by destabilizing and repressing target RNAs (reviewed in REF. 12). lncRNAs can act at multiple levels. At the DNA level, lncRNAs regulate gene expression by a range of mechanisms, including transcriptional interference by antisense transcription and modulation of chromatin modifications (reviewed in REFS 11,14).

In this Review, we highlight the recent advances in our understanding of ncRNA-mediated regulation during animal embryogenesis, focusing mainly on regulatory roles of miRNAs and lncRNAs. Readers interested in RNA-mediated control of plant development should refer to recent publications15–18. piRNAs and endo-siRNAs (reviewed in REFS 19,20) seem to function predominantly in the germ line and will be discussed only in the context of their potential roles during embryogenesis.

Global requirements for miRNAs

The functions of ncRNAs can be explored globally as well as at the level of specific RNAs. Biogenesis of most miRNAs depends on specific RNA processing enzymes, including Drosha, its essential cofactor DGCR8, and Dicer (reviewed in REF. 20). Because the biogenesis of endo-siRNAs involves Dicer but not DGCR8, deleting Dicer abolishes the production of most mature miRNAs and endo-siRNAs, whereas deleting DGCR8 specifically blocks canonical miRNA biogenesis. This provides a powerful approach for determining the global roles of miRNAs. By contrast, there is no known dedicated post-transcriptional processing machinery for lncRNAs, which impedes specific blockage of their biogenesis.

Evidence that miRNAs are essential for vertebrate embryogenesis comes from the phenotypes of zebrafish mutants that lack both maternal and zygotic Dicer activity (known as MZdicer mutants)21–23. MZdicer fish undergo gametogenesis, cell fate determination and early patterning, but they show defects in germ layer formation, morphogenesis and organogenesis. Importantly, many of these defects are rescued by mature miR-430 (discussed further below), demonstrating that the phenotypes of MZdicer fish are indeed due to an absence of miRNA function.

miRNA activity is also essential for normal progression through mouse embryogenesis, as evidenced by the malformation and resorption of maternal–zygotic Dgcr8 mutants24,25. Dgcr8 mutant mouse oocytes develop normally25, but Dicer1 mutant oocytes have hundreds of misregulated transcripts and are impaired in maturation26,27. The phenotypic differences between Dicer1 and Dgcr8 mutant mouse oocytes indicate that endo-siRNAs but not miRNAs are essential for oocyte maturation. Subsequent roles of miRNAs in mammalian post-fertilization development are revealed by tissue-specific deletions of Dicer (reviewed in REF. 13).

Analyses of global miRNA function during early embryonic development in flies and worms have been hampered by severe germline defects and sterility caused by loss-of-function mutations in the small RNA processing machinery (reviewed in REF. 13). Nevertheless, recent knockout studies of individual miRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans suggest that miRNA activity is also required during early invertebrate embryogenesis28,29. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that miRNAs regulate various aspects of animal embryogenesis.

Clearance of maternal mRNAs

The earliest known role of embryonic miRNAs is during the maternal–zygotic transition (MZT), when zygotic transcription starts and maternal mRNAs are degraded (reviewed in REFS 30,31). The zebrafish miR-430 cluster is expressed during zygotic genome activation and accelerates the deadenylation and clearance of hundreds of maternal mRNAs22. Maternal mRNAs persist abnormally in MZdicer mutants, but the resulting defects in embryonic morphogenesis are rescued by expression of mature miR-430 family members (FIG. 1a). The role of miRNAs in repressing maternal transcripts is evolutionarily conserved: both the miR-430 orthologue in frogs (miR-427)32 and families of unrelated embryonic miRNAs in Drosophila melanogaster and C. elegans33,34 also trigger the deadenylation of maternal mRNAs. Interestingly, recent work in D. melanogaster has raised the possibility that piRNAs, which have so far been implicated only in the germ line (reviewed in REF. 20), may also contribute to the timely decay of maternal mRNAs35. Together, these findings show how small ncRNAs promote developmental transitions by removing mRNAs that are expressed at the preceding developmental stages.

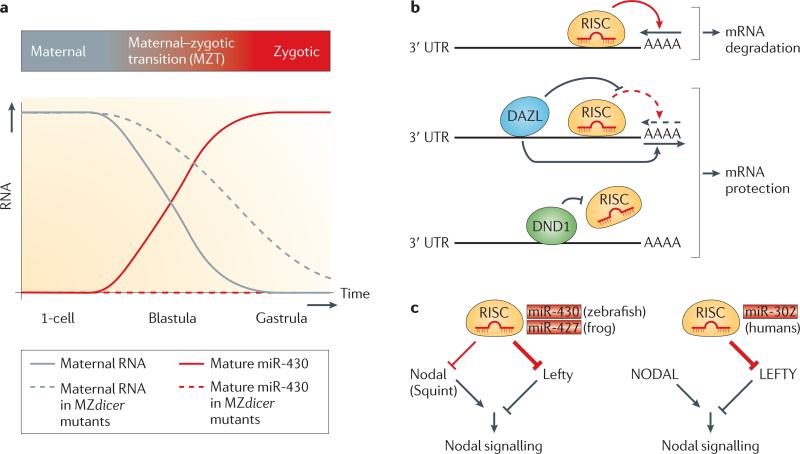

Figure 1. miR-430 — a multitasking microRNA family during embryogenesis.

a | Clearance of maternal RNAs by miR-430. The miR-430 family promotes clearance of maternal RNAs in zebrafish and frogs. Maternal RNAs that are present in the egg drive early development in the absence of zygotic transcription. Activation of zygotic transcription leads to the expression of zygotic genes, including miR-430. Mature miR-430 accelerates the decay of hundreds of maternal RNAs. In the absence of Dicer (as in maternal-zygotic Dicer (MZdicer) mutants), primary miR-430 transcripts are not processed into mature miR-430, which results in prolonged persistence of maternal RNAs. b | Modulation of miR-430 effector function. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) normally direct RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to the 3′ UTR of target genes and promote deadenylation of mRNAs (poly(A) tail shortening indicated by an arrow above AAAA). Binding of deleted in azoospermia-like (DAZL) to certain mRNAs antagonizes miRNA–RISC effector function by promoting polyadenylation of the mRNA. Similarly, binding of dead end 1 (DND1) to cis elements within 3′ UTRs of certain mRNAs prevents miRNA–RISC association. c | miR-430 family members regulate Nodal signalling. In fish and frogs, RISC, which contains miR-430/miR-427, dampens and balances Nodal signalling by repressing both agonistic (Nodal) and antagonistic (Lefty) ligands. The human orthologue of miR-430 (miR-302) targets only the antagonist LEFTY, and thereby enhances Nodal signalling. miRNA-mediated repression is shown in red (the thickness of the line indicates the strength of repression) and protein-mediated silencing or activation in black.

Analysis of miR-430 targets in zebrafish revealed two classes of mRNAs36. The first class is removed in both somatic cells and primordial germ cells (PGCs), whereas the second class is degraded in the soma but not in the germ line. mRNAs belonging to the second class are protected from miR-430 activity by the proteins deleted in azoospermia-like (DAZL) and dead end 1 (DND1)37,38 (FIG. 1b). DAZL is enriched in germ cells and promotes the poly(A)-tail elongation of a subset of miR-430 target mRNAs. Thus, DAZL counteracts miR-430-induced deadenylation and increases the efficiency of translation of the mRNAs to which it binds38. Human DAZL is essential for primordial germ cell formation39, suggesting that DAZL-mediated miRNA target protection may be evolutionarily conserved. DND1 uses a different mechanism to counteract certain human miRNAs as well as miR-430 in zebrafish germ cells. It interferes with the interaction of specific miRNAs with target mRNAs by binding to target 3′ UTRs36,37. DAZL and DND1 illustrate how the modulation of miRNA activity at subsets of target mRNAs can control cell type-specific gene expression.

Renewal and differentiation of ES cells

The conserved function of miR-430 family members in fish and frogs raises the possibility that miR-430 orthologues in mice (miR-290–295) and humans (miR-302, miR-372 and miR-516–520) are also involved in the MZT. These miRNAs are expressed during early mammalian development40, but no mutational analysis has been carried out to address their function in vivo. However, mammalian miR-430 orthologues have emerged as important regulators of embryonic stem (ES) cell pluripotency.

The hallmark of ES cells is their ability to self-renew and to produce differentiated cells of any fate. These unique properties depend on specific gene regulatory circuits that feature pluripotency factors such as OCT4 (also known as POU5F1), SOX2, Nanog, Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), transcription factor E2-α (TCF3) and MYC (also known as c-MYC). Recent studies show that miRNAs and possibly lncRNAs are also involved in ES cell maintenance and differentiation (FIG. 2).

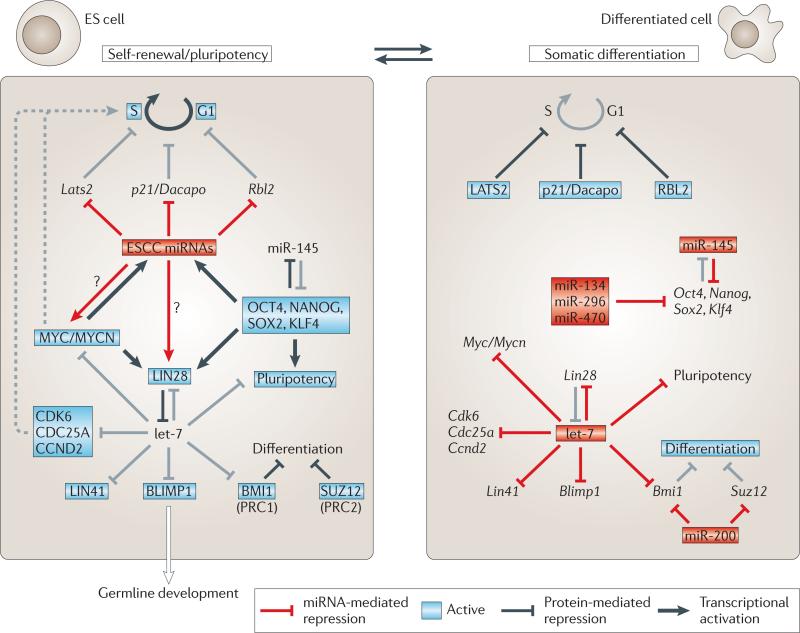

Figure 2. Regulation of pluripotency by microRNAs.

Model for the various roles of different families of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the gene regulatory network that maintains pluripotent and differentiating cell states. Maintenance of embryonic stem (ES) cell fate depends on the activity of the ES cell-specific cell-cycle-regulating (ESCC) miRNAs, which are induced by the core pluripotency factors OCT4, Nanog, SOX2 and KLF4 or TCF3, as well as by MYC or MYCN. ESCC miRNAs trigger S phase entry by repressing negative G1–S phase regulators (for example, the serine–threonine protein kinase LATS2, the cyclin E-Cdk2 inhibitor p21 (also known as Dacapo) and retinoblastoma-like protein 2 (RBL2))44. Key to the stabilization of either the pluripotent or the differentiated state is the antagonism between LIN28 (on in ES cells, off in differentiating cells) and let-7 (off in ES cells, on in differentiating cells). let-7 has a central role in promoting somatic differentiation by repressing multiple genes with important functions in ES cells. Other miRNAs that contribute to the suppression of pluripotent genes upon differentiation include miRNAs that repress pluripotency factors and miR-200 family members that repress the activity of Polycomb repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 (REFS 148,165,166). Red boxes indicate active miRNAs; unboxed text indicates inactive genes/miRNAs; grey lines indicate inactive processes. For further details, see the main text. Figure is modified, with permission, from REF. 46 © (2010) Macmillan Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

miRNAs in ES cell proliferation.

Studies that removed miRNA biogenesis components indicate essential roles for miRNAs in ES cell proliferation and differentiation. For example, Dicer1 mutant mouse embryos are impaired in ES cell generation41, and Dicer1 as well as Dgcr8 mutant mouse ES cells show severe growth and differentiation defects24,26,42,43.

The proliferation defects of Dgcr8 mutant mouse ES cells are partially rescued by expression of mature members of the miR-290–295/302 family44. Because of their sufficiency in promoting a cell cycle that is characteristic of ES cells, these miRNAs are called ES cell-specific cell cycle-regulating (ESCC) miRNAs. They trigger S phase entry by silencing multiple negative G1–S regulators44 (FIG. 2). The potency of ESCC miRNAs in promoting rapid stem cell proliferation is further highlighted by their ability to enhance de-differentiation of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) and to substitute for MyC in iPS cell generation45.

miRNAs in ES cell differentiation

Whereas ESCC miRNAs enable Dgcr8 mutant ES cells to proliferate, mature let-7 miRNA partially rescues their differentiation defects46. let-7 represses several key pathways that are crucial for ES cell identity, including genes that promote cell cycle progression47 and stem cell identity46,48 (FIG. 2). Consistent with the ability of let-7 to promote differentiation and repress self-renewal, blocking let-7 activity increases reprogramming efficiency46. The opposing roles of ESCC miRNAs and let-7 in ES cell self-renewal and differentiation, respectively, illustrate how specific sets of miRNAs can maintain a particular cellular property or induce alternative fates.

It needs to be stressed that our current understanding of let-7 function in vertebrates is mainly based on in vitro knockdown and overexpression studies, and a direct contribution of let-7 to vertebrate development has not yet been demonstrated. The difficulty in generating let-7 knockout models in the presence of multiple potentially redundant family members is one example of the difficulty of assessing miRNA function in vivo.

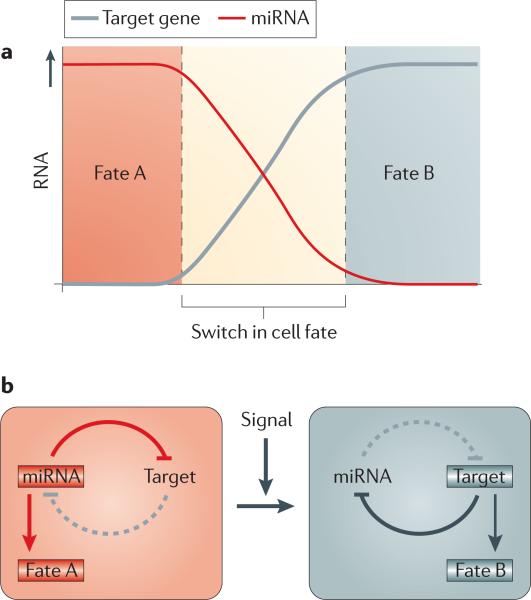

In addition to let-7, several other miRNAs have been implicated in repressing pluripotency in differentiating ES cells (reviewed in REF. 49) (FIG. 2). Whereas most promoters of ES cell-specific miRNAs are bound and induced by OCT4, SOX2, Nanog and TCF3 (REF. 50), these core pluripotency factors are post-transcriptionally repressed by several differentiation-induced miRNAs. For example, human miR-145 downregulates OCT4, SOX2 and KLF4 upon differentiation51. As OCT4 represses miR-145 expression, the interplay between miR-145 and OCT4 is an example of a bistable feedback loop involved in balancing pluripotency and differentiation (FIGS 2,3).

Figure 3. RNAs control alternative cell fate decisions.

A recurrent theme of microRNA (miRNA) regulation during embryogenesis is their ability to control alternative cell fate decisions. Mutual repression between an miRNA and its target mRNA ensures reciprocal expression. The resulting bistable, double-negative feedback loop stabilizes either one of two possible cell fates and also promotes a rapid transition between the two states. Examples of bistable loops during embryogenesis include let-7–LIN28, miR-145–OCT4, miR-124–REST–SCP1, miR-9–TLX and miR-200–ZEB1.

The let-7–LIN28 bistable switch

Paradoxically, despite the role of let-7 in driving cellular differentiation, the let-7 precursor RNAs are present in both pluripotent and differentiated cells. This enigma has been resolved by the discovery that the pluripotency factor LIN28 binds to a short tetranucleotide binding motif in the terminal loop of let-7 miRNA precursors and blocks their processing by Drosha52,53 and Dicer54,55. Inhibition of Dicer-mediated pre-let-7 processing depends on LIN28-mediated recruitment of the non-canonical poly(A) polymerase TUTase4 (also known as ZCCHC1), which adds an oligo-uridine tail to the 3′ end of pre-let-7 and causes its degradation (reviewed in REF. 56).

As let-7 prevents LIN28 expression by binding to the Lin28 3′ UTR55, let-7 and LIN28 establish a toggle switch between pluripotent (let-7 off, LIN28 on) and differentiated (let-7 on, LIN28 off) cell fates. The antagonism between let-7 and LIN28 further illustrates a major theme in miRNA regulation during embryogenesis: miRNAs participate in bistable loops and thereby control and stabilize alternative cell fate decisions (FIG. 3). let-7 also promotes differentiation by repressing MYC, which collaborates with OCT4, SOX2, Nanog and TCF3 to induce LIN28 and ESCC miRNAs45. The observation that MYC and KLF4 can be replaced by LIN28 and Nanog in iPS cell generation57 highlights the existence of an interlinked gene regulatory network that can be shifted towards pluripotent or differentiated cell fates (FIG. 2).

In contrast to somatic tissue differentiation, which is inhibited by LIN28, differentiation of mouse ES cells into PGCs requires LIN28 (REF. 58). As in ES cell maintenance, LIN28 inhibits let-7 processing and thereby indirectly stabilizes the let-7 target gene that encodes PR domain zinc finger protein 1 (Prdm1; also known as Blimp1), a key regulator of PGC commitment (FIG. 2). PRDM1 seems to be the main mediator of LIN28 function in PGC development, as it can rescue the failure of Lin28 knockdown ES cells to contribute to the germ line in chimeric mouse embryos.

Long non-coding RNAs and pluripotency

Recent studies in mouse ES cells suggest that lncRNAs are integral members of the ES cell regulatory circuit59–61. Expression of several lncRNAs correlates with the expression of pluripotency markers62, and more than 100 lincRNA promoters are bound by stem cell factors such as OCT4 and Nanog59. Overexpression and knockdown of individual OCT4- or Nanog-controlled lncRNAs interferes with ES cell maintenance and modulates ES cell lineage-specific differentiation61. Recently a study identified a set of lincRNAs that are associated with pluripotency, including the lincRNA-RoR (regulator of reprogramming) that is required for and enhances the reprogramming of fibroblasts into the pluripotent state63. Despite these insights, a comprehensive understanding of the roles of lncRNAs in stem cell function awaits loss-of-function analyses.

Germ layer specification

The first specialization of pluripotent cells during embryogenesis is their allocation to a germ layer — ectoderm, mesoderm or endoderm. Two members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) family, Nodal and Lefty, regulate germ layer formation (reviewed in REF. 64). Nodal promotes mesoderm and endoderm formation, whereas lefty blocks Nodal signalling and promotes ectoderm development. Strikingly, members of the miR-430/290–295/302 family not only promote the degradation of maternal mRNAs and ES cell proliferation but also repress Nodal signalling23,65,66 (FIG. 1c). For example, zebrafish miR-430 modulates Nodal signalling by targeting the Nodal ligand Squint and its antagonist Lefty2 (REF. 23). Absence of miR-430-mediated repression causes an imbalance and overall reduction in Nodal signalling. Thus, miR-430 balances the counteracting inputs of Nodal and Lefty and promotes mesendoderm formation. Similar to the role of miR-430 in zebrafish23, miR-427 regulates Nodal and Lefty expression in frogs66. By contrast, human miR-302 targets Lefty but not Nodal66: interference with miR-302 function reduces Nodal signalling in human ES cells and blocks differentiation into mesendoderm (FIG. 1c).

In addition to Nodal pathway ligands, the Nodal receptor activin receptor 2a (Acvr2a) is also subject to repression by miRNAs65. Mature miR-15/16 is present in a ventral–dorsal gradient in Xenopus laevis embryos, which results in the preferential repression of Acvr2a at the future ventral side. The higher levels of Acvr2a on the dorsal side are thought to contribute to the dorsal–ventral gradient of Nodal activity. This role might be conserved in humans, as miR-15 can target human ACVR2A in vitro.

The regulation of Nodal signalling by miRNAs is an example of how miRNAs modulate activity thresholds of dosage-sensitive pathways and thus modulate cell fate decisions. This characteristic feature of miRNA-mediated regulation has also been exploited in other concentration-dependent pathways such as Hedgehog67, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)68, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)69 and D. melanogaster Notch signalling70.

Imprinting and dosage compensation

One of the earliest developmental roles for lncRNAs occurs during dosage compensation71 and imprinting72. Both processes are required for normal development and rely on lncRNA-mediated epigenetic modulation of chromatin states to regulate gene expression levels.

Imprinting

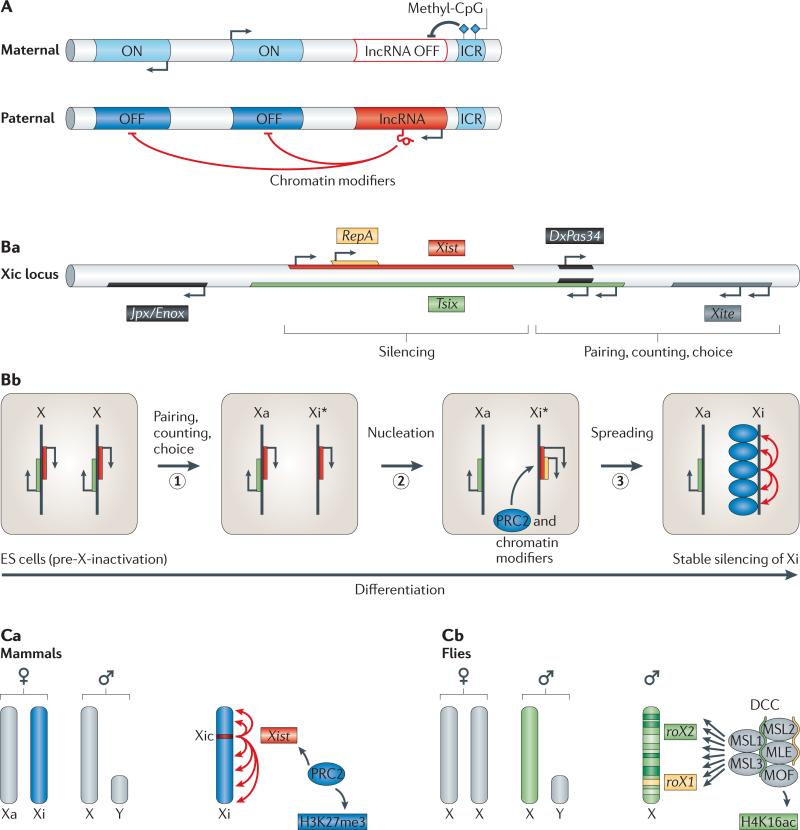

Even though not all imprinted lncRNAs may have a functional role in imprinting73, it is intriguing that most of the known imprinted domains contain at least one lncRNA with anti-correlated expression (reviewed in REF. 72). Parental-specific expression of lncRNAs is controlled by the inheritance of differentially methylated DNA sequences known as imprinting control regions (ICRs). An unmethylated ICR enables expression of a nearby lncRNA, which leads to silencing of selected neighbouring genes in cis (FIG. 4A). For example, in mice, paternal-allelic expression of two lncRNAs, antisense to Igf2r RNA non-coding (Airn) and Kcnq1-overlapping transcript 1 (Kcnq1ot1), is essential for the silencing of some neighbouring paternal genes74,75. Although the mechanism of silencing in the embryo proper is still unclear, in extra-embryonic lineages such as the placenta, lncRNA-mediated recruitment of complexes that modify histones76–79 and/or DNA80 results in allele-specific chromatin profiles (FIG. 4A). The role of imprinting is still unknown for most loci, but the antagonistic activities of the imprinted genes insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) and IGF2 receptor (Igf2r) during growth control demonstrate a function for imprinting in development (reviewed in REF. 81). Imprinting illustrates how cis-acting lncRNAs can silence neighbouring genes and thus regulate gene dosage.

Figure 4. Imprinting and dosage compensation.

A | Imprinting. Parental-specific, monoallelic expression of gene clusters is based on differentially methylated imprinting control regions (ICRs). Only the unmethylated ICR (here shown on the paternal allele) is active and induces expression of a nearby long non-coding RNA (lncRNA, red). The lncRNA recruits repressive chromatin modifiers in cis to selected neighbouring genes, resulting in their silencing (OFF, dark blue). By contrast, a methylated ICR (here shown on the maternal allele) prevents expression of the lncRNA and thereby allows transcription of neighbouring genes (ON, light blue). B | Mechanism of X inactivation in mammals. In mammals, X chromosome inactivation occurs in distinct steps that depend on the activities of several lncRNAs that originate from the X-inactivation centre (Xic). Ba | Scheme of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) at the Xic locus. Bb | Steps of X inactivation in mammalian females. In embryonic stem (ES) cells, both X chromosomes express low levels of two key lncRNAs, Xist (red) and Tsix (green). Upon differentiation, one of the two X chromosomes is randomly selected to continue expressing Tsix (active X (Xa)). This process requires pairing, counting and choice (step 1). Tsix expression from Xa interferes with expression of Xist and RepA (yellow) in cis. On the future inactive X (Xi*), RepA recruits Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to nucleate repressive chromatin marks, which are essential for upregulation of Xist expression on Xi* (step 2). Silencing spreads along the entire Xi* in an Xist-dependent manner, resulting in the establishment of a stable heterochromatic state on Xi (inactive X) (step 3). c | Comparison of dosage compensation in mammals and flies. In mammals, one of the two female X chromosomes is inactivated (dark blue), whereas flies upregulate the single X chromosome in males about twofold (green). ca | X inactivation in mammals depends on spreading of Xist (red) from its site of transcription along the entire length of the X chromosome. Xist-associated protein complexes such as PRC2, which catalyses trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3), establish a stably repressed chromatin state on Xi (dark blue). cb | By contrast, the fly dosage compensation complex (DCC), which contains the two ncRNAs roX1 and roX2 as structural components, binds discontinuously at hundreds of sites along the male X chromosome and deposits the activating H4K16-acetyl mark (twofold upregulated X chromosome in green). Panels Ba and Bb are modified, with permission, from REF. 167 © (2010) Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

X chromosome inactivation in mammals

In the mammalian female embryo, random inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes equalizes X-linked gene dosage. Inactivation is mediated by a genomic region called the ‘X-inactivation centre’ (Xic), which encodes at least seven regulatory ncRNAs (reviewed in REF. 71) (FIG. 4Ba). One of them, the 17 kb lncRNA Xist, is the primary mediator of X-inactivation and is essential for silencing the X chromosome from which it is expressed (the inactive X, Xi)3–5,82. Xist and the Xist antisense transcript Tsix are initially biallelically expressed, but then, by still unclear means, Tsix continues to be transcribed from only one of the two X chromosomes, the future Xa (active X) (FIG. 4Bb). Tsix transcription results in stable silencing of Xist in cis by recruitment of the DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A to the Xist promoter on Xa. Whether this process involves Dicer-mediated processing of long duplex Tsix–Xist RNA is controversial83–85. Upregulation of Xist expression on Xi requires a trans-acting lncRNA called Jpx, which is encoded within the Xic and has been suggested to antagonize Tsix86. Absence of Tsix expression on Xi enables expression of an internal transcription unit within the Xist transcript called repeat A (RepA)87,88. RepA recruits Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) in cis, which then deposits repressive histone-modification marks (H3K27me3) at the 5′ end of Xist89. This RepA-directed repressive chromatin state is essential for upregulation of Xist expression from Xi85 and the subsequent Xist-dependent propagation of the silencing marks along the entire Xi (FIG. 4Bb,Ca). Coating of Xi by Xist leads to the establishment of heterochromatin that is maintained throughout the lifespan of females. X inactivation illustrates how a cascade of interactions among multiple lncRNAs establishes stably silenced chromatin domains that determine and maintain a specific developmental fate.

Dosage compensation in flies

Flies have evolved a different strategy to balance X-linked gene expression. Dosage compensation also depends on X-linked lncRNAs — roX1 and roX2 (RNA on the X 1 and 2) — but the D. melanogaster roX1and roX2-containing dosage compensation complex (DCC) does not induce silencing. Instead, it directs approximately twofold upregulation of most genes on the single male X chromosome (reviewed in REF. 90) (FIG. 4Cb). DCC binding activates expression of neighbouring genes by acetylating histone H4 (REF. 91). Loss-of-function mutations in core DCC proteins or roX1 roX2 double mutants cause lethality in males resulting from reduced expression of X-linked genes92,93.

The redundantly acting roX1 and roX2 ncRNAs seem to have both cis and trans activities. The roX loci function as DCC entry sites in cis, and roX RNAs are required for proper targeting of the DCC to the X chromosome92–94. However, unlike for Xist, X-chromosomal expression of these ncRNAs is not an absolute requirement for the upregulation of X-linked genes in males, because transgenic autosomal roX expression can rescue male lethality92. Therefore, roX RNAs can also function in trans and might act as structural components of the DCC.

In contrast to the single nucleation site in Xist-mediated silencing, fly X chromosomes contain hundreds of DCC binding sites with varying affinities95,96 (reviewed in REF. 90) (FIG. 4C). A common feature of DCC binding sites is their transcriptional activity97. Analogous to roX1 and roX2 loci, which have DCC-recruiting activities93,94, additional ncRNAs originating from genes on the X chromosome may therefore contribute to cis-recruitment of the DCC.

The roles of lncRNAs in imprinting and in balancing X-linked gene dosage show how lncRNAs can induce stable chromatin states that regulate hundreds of genes. The similarity of the mechanisms used in imprinting and dosage compensation to achieve monoallelic silencing of particular genomic regions highlights the capacity of lncRNAs to act as guides and tethers for epigenetic modifiers. The ability of lncRNAs to establish stable gene expression makes them ideally suited for maintaining developmental fates.

Regulation of Hox clusters

Hox genes regulate anterior–posterior patterning in all bilateria, and their misexpression can cause homeotic transformations. Several years before the discovery of lncRNAs as key determinants of X inactivation and imprinting, it was noted that “substances which in turn regulate other genes that actually determine segmental structure and function”98 and which “curiously … do not possess any significant coding potential”99 originate from regulatory regions of Hox clusters in D. melanogaster. Some of these hypothetical ‘substances’ have now been identified as ncRNAs.

Cis-regulation by ncRNAs

Transcription of non-coding regions in Hox clusters can regulate the expression of neighbouring Hox genes. For example, forced transcription through intergenic Polycomb group (PcG) response elements (PRes) in the D. melanogaster Bithorax complex causes homeotic transformations. These phenotypes resemble abnormalities that are caused by Hox gene misexpression and correlate with a loss of PRE-mediated silencing100,101. Silencing is lost irrespective of the direction of transcription, suggesting that the process of transcription per se can modulate the expression of neighbouring genes101 (FIG. 5Aa).

Figure 5. RNAs modulate chromatin.

A | Models of gene regulation by cis- and trans-acting long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). Aa | In cis (left), the process of transcription can displace DNA-bound factors that inhibit (left) or activate (right) transcription of a neighbouring gene (process of transcription). Ab | Alternatively, nascent non-coding transcripts can function as tethers for chromatin-modifying complexes and/or transcriptional regulators, which can have either activating (left) or repressive (right) activities (tether model). Ac | Trans-acting non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) can serve as platforms for the assembly of protein complexes (scaffold model). In this model, target sites are specified by DNA-binding proteins. Ad | Alternatively, trans-acting ncRNAs can specify target sites by forming hybrids with complementary DNA sequences, and thus recruit chromatin modifiers and transcriptional regulators (guide model). Ae | lncRNAs can also modulate the activity of protein complexes by inducing conformational changes (allosteric model). For simplicity, only repressive activities are shown as examples of trans-acting mechanisms. B | The lncRNA HOX antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) regulates gene expression in trans by providing a scaffold for chromatin-modifying complexes. HOTAIR is expressed from the HOXC cluster and represses multiple target genes elsewhere in the genome. HOTAIR binds to the H3K27-trimethylating Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) and the H3K4me2/3-demethylating lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1)–CoREST–REST complex, which together establish a repressive chromatin state at HOTAIR-associated target genes (OFF, dark blue). Pol II, RNA polymerase II.

Two conflicting studies have implicated ncRNAs originating from bithoraxoid (bxd), the upstream regulatory region of the D. melanogaster Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx), in regulating Ubx expression. According to a report in embryos, transcription across bxd prevents expression of Ubx102 (FIG. 5Aa). By contrast, a study in larval imaginal discs suggests that bxd transcripts induce Ubx expression by tethering a histone methyltransferase to the Ubx promoter103 (FIG. 5Ab).

The cause for this discrepancy is unclear, but there is evidence for both repressive and activating effects of other lncRNAs. For example, a recent study in mammalian cells suggests that lncRNAs can have enhancer-like activity and promote expression in cis104. Conversely, a lncRNA at the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) locus binds to and inhibits expression from the DHFR promoter105 (FIG. 5Ab). Cis-acting repression might also be induced by short transcriptional start site-associated ncRNAs (TSSa RNAs). Many human TSSa RNAs are GC-rich, can form stem–loop structures and have been suggested to recruit PRC2 to silence genes106. Although it remains unclear whether these ncRNAs have embryonic functions, these studies suggest pervasive roles of cis-acting small and long ncRNAs in recruiting chromatin modifiers and modulating local gene expression.

Trans-regulation by lncRNAs

The study of human HOX transcripts led to the discovery of HOX antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR), a trans-acting lncRNA107. Unlike Xist and imprinted lncRNAs, which seem to function strictly in cis, HOTAIR does not contribute to gene regulation at its site of expression in the HOXC cluster. Instead, it has been implicated in repressing genes located at other sites in the genome, including a domain in the HOXD cluster107. The silencing activity of HOTAIR is based on its interaction with two histonemodifying complexes, the H3K27-trimethylating PRC2 (REF. 107) and the H3K4me2/3-demethylating lysine-specific demethylase1 (LSD1)–CoREST–REST complex108 (FIG. 5B). These two protein complexes cooccupy and repress HOXD and several other loci in a HOTAIR-dependent manner. Thus, HOTAIR might act as a molecular scaffold for modulating expression of genes throughout the genome107–109 (reviewed in REFS 14,110) (FIG. 5Ac,Ad,B). It is currently unclear whether HOTAIR itself selects its target sites and acts as a guide for interacting protein complexes (FIG. 5Ad), or whether target sites are selected by the DNA-binding specificity of interacting protein complexes (for example, CoREST) (FIG. 5Ac). Although the basis of HOTAIR recruitment is unknown and analysis of its role during embryogenesis awaits the generation of mutant alleles, HOTAIR illustrates the potentially wide-ranging effects of lncRNAs as trans-acting regulators62,111–113 (reviewed in REF. 14) (FIG. 5Ac–e).

Hox genes can escape miRNA regulation

In addition to many ncRNAs, Hox clusters encode two evolutionarily conserved miRNAs, miR-10 and miR-196 (iab-4 in D. melanogaster)114–116. Several Hox genes (for example, Ubx in D. melanogaster) contain conserved target sites for these Hox miRNAs, and Hox miRNA overexpression can cause homeotic transformations in D. melanogaster and chicks117,118. However, the absence of Hox-like patterning defects in D. melanogaster mutants that lack iab-4 raises the question of how important Hox miRNAs are during embryogenesis119.

Early Ubx transcripts have shorter 3′ UTRs that lack most miRNA-binding sites120. It is thus conceivable that iab-4 is dispensable for establishing early Ubx expression domains but might be required during later central nervous system development, when long 3′ UTR-containing Ubx transcripts dominate120. These observations highlight the potential for differential 3′ UTR length in escaping, allowing or fine-tuning miRNA-induced regulation.

Cell fate specification

The specification of cell fates is dictated by the activation of lineage-specific genes and the suppression of genes that promote alternative fates. Intriguingly, ncRNAs have emerged as regulators of both processes in muscles, neurons, the haematopoietic system and other cell types (reviewed in REFS 13,121). We focus here on neural development as a representative developmental process that illustrates the important roles of ncRNAs in fate specification.

miR-124: a master regulator of neural development?

In vertebrates, miR-124 is considered a master regulator of neural development. In vitro, miR-124 overexpression triggers, and miR-124 knockdown prevents, neural differentiation (reviewed in REF. 122). Consistent with its pro-neural activity, miR-124 is abundantly expressed in neural progenitors and mature neurons, where it represses several genes with anti-neural activities (FIG. 6a). For example, miR-124 downregulates small C-terminal domain phosphatase 1 (SCP1), which serves as a cofactor for REST to suppress the transcription of genes that promote neural development. miR-124 itself is transcriptionally repressed by SCP1–REST in nonneuronal cells123,124. Reminiscent of the let-7–LIN28 toggle switch in ES cells, the miR-124–SCP1 cross-repression ensures de-repression of neural genes in the developing neural lineage and repression of neural genes in non-neural cells (FIGS 3,6a).

Figure 6. Non-coding RNAs regulate neural development.

a | miR-124 promotes neural development by orchestrating the repression of several pathways that interfere with neural differentiation. Targeting of the mRNAs polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 (PTB), neuronal progenitor-specific BAF (npBAF) and small C-terminal domain phosphatase 1 (SCP1) by miR-124 promotes neural-specific splicing, neuronal chromatin remodelling and neural gene expression, respectively. These concerted changes are a driving force of neural differentiation. miR-124 has also been implicated in promoting adult neurogenesis in mice by repressing the transcription factor SOX9 (REF. 168). In Aplysia, miR-124 has been implicated in modulating synaptic plasticity by downregulating the transcriptional activator CREB144. b | Cell fate specification by lsy-6 in Caenorhabditis elegans. A double-negative feedback loop under control of microRNAs and two transcription factors (DIE-1 and COG-1) specifies neuronal identities in C. elegans. Repression of cog-1 by DIE-1-induced lsy-6 is essential for establishing left side (ASEL) neuronal identities. Conversely, COG-1 interferes with DIE-1 expression in ASER neurons by activating a still unknown factor that represses die-1. Red boxes indicate active miRNAs; light blue boxes indicate active proteins; unboxed text indicates inactive elements; grey lines indicate inactive processes.

mir-124 also enhances neural differentiation by promoting exchanges of cell type-specific protein variants. For example, miR-124 represses the neural progenitor-specific variant of the chromatin-remodelling complex BAF (npBAF), which promotes neural progenitor proliferation. Thus, miR-124 relieves npBAF-mediated inhibition of neural differentiation, which is in turn promoted by the neuron-specific form of BAF (nBAF)125. In addition, miR-124 promotes neural-specific alternative splicing through the neural variant of the global repressor of alternative splicing polypyrimidine tractbinding protein 1 (PTB; neural variant, nPTB)126. PTB blocks expression of nPTB in non-neural cells by causing exon skipping and degradation of nPTB mRNA. miR-124-mediated repression of PTB during neural differentiation allows correct splicing of nPTB and results in widespread changes in the splicing pattern in neurons. Conversely, downregulation of nPTB is reinforced by the muscle-specific miRNA miR-133, which contributes to muscle differentiation127. These findings exemplify the intimate crosstalk that exists between miRNA-dependent gene regulatory networks that control distinct cell fates.

The examples of miR-124 function highlight the ability of miRNAs to temporally and spatially orchestrate the modulation of hundreds of genes by means of targeting a few key components of distinct gene regulatory pathways (for example, transcriptional regulators, splicing factors or chromatin remodellers). Importantly, interactions between miRNAs and regulatory proteins are widespread in miRNA-mediated control of distinct cellular differentiation pathways. For example, regulatory interactions between the muscle-specific miRNAs miR-1 and miR-133 and core transcription factors (for example, the serum-response factor SRF and the myogenic transcription factor MYOD) and the histone deacetylase HDAC4 are central to skeletal and cardiac myogenesis128–130.

Only a few of the many miR-124 targets have been mentioned here, and miR-124 represses several additional mRNAs with functions in neurogenesis (reviewed in REF. 122). In addition, there are other miRNAs, such as miR-9, that have been implicated in various aspects of neural development in mice, fish and flies (reviewed in REF. 122). For example, mutual repression between miR-9 and the nuclear receptor TLX (also known as NR2E1) contributes to the control of differentiation of neural stem cell progenitors in mice131 (FIG. 3). Despite the plethora of data that support important roles of miR-124 and miR-9 in promoting neural differentiation, genetic loss-of-function experiments are needed to conclusively test this hypothesis; such studies are urgently needed given the very mild phenotypes observed in C. elegans miR-124 mutants132.

Cell fate specification by miRNA lsy-6

In C. elegans, lsy-6 is a striking example of an miRNA that regulates the formation of a highly specialized neuronal fate. During left–right patterning, the gustatory neurons ASEL and ASER acquire distinct fates. lsy-6 is specifically expressed in ASEL neurons. Loss of lsy-6 causes a cell fate switch from left (ASEL) to right (ASER) side neuronal identity133. Two transcription factors, COG-1 and DIE-1, are part of the ASEL–ASER network. lsy-6 is activated by DIE-1 and represses COG-1 in ASEL by binding to the cog-1 3′ UTR (FIG. 6b). Conversely, COG-1 is expressed in ASER, where it represses DIE-1 expression. This repressive effect is mediated by the DIE-1 3′ UTR, suggesting that COG-1 activates miRNA(s) or RNA-binding proteins that repress die-1 (REF. 134). It should be noted that members of the miR-273 family are expressed in ASER and, if misexpressed, can repress die-1. However, these miRNAs are not required for die-1 repression135. The lsy-6–cog-1–die-1 network (FIG. 6b) highlights how miRNAs can regulate the activity of bistable feedback loops and thus ensure the specification of discrete neuronal identities.

lncRNAs increase neuronal complexity

In addition to miRNAs, lncRNAs are likely to have key roles in neuronal fate specification and/or maintenance. Even though only a few of the numerous lncRNAs expressed in the nervous system136,137 have been functionally characterized, their restricted expression patterns and genomic locations adjacent to genes with neural functions136 suggest roles in neural development11.

Taurine-upregulated gene 1 (TUG1) is a conserved mammalian lincRNA involved in photoreceptor development138. TUG1-depleted photoreceptor cells show abnormal morphology of outer segments and complex alterations in gene expression patterns. It has been suggested that TUG1 might bias gene expression towards rod-typed cells by inhibiting expression of cone-specific genes. These effects might be mediated by the association of TUG1 with PRC2 (REF. 111), but the biological significance of this interaction remains to be tested in vivo.

One of the few lncRNAs that has been analysed by loss-of-function studies is Evf2 (REF. 113). This lncRNA is expressed in the embryonic mouse forebrain in domains similar to those of the homeobox transcription factors DLX5 and DLX6, which are encoded in the region adjacent to the Evf2 gene. Mice that are mutant for Evf2 demonstrate an essential function of this lncRNA in the development of GABAergic neurons113. Evf2 regulates the expression of Dlx5, Dlx6 and glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 (Gad1) through cis- and trans-acting mechanisms. Initial in vitro studies suggested that Evf2 may function as a transcriptional co-activator of homeobox protein DLX2 at the Dlx5–Dlx6 locus139. However, subsequent in vivo analysis revealed that Dlx5–Dlx6 expression increases in Evf2 mutants113, indicating a negative regulatory role of Evf2 at Dlx5–Dlx6. Whereas Dlx6 inhibition was proposed to be caused by transcriptional interference in cis, repression of Dlx5 and activation of Gad1 seem to be mediated by a trans-activity of Evf2, which involves recruitment of DLX homeodomain proteins and the DNA methyl-binding protein MECP2. Collectively, the roles of TUG1 and Evf2 illustrate important functions for lncRNAs in specific neuronal cell types.

Morphogenesis

ncRNAs have also been implicated in various morphogenetic processes, ranging from synaptogenesis to tissue rearrangements140–144. We focus on the roles of ncRNAs in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a fundamental morphogenetic process (reviewed in REF. 145).

ncRNAs regulate the EMT

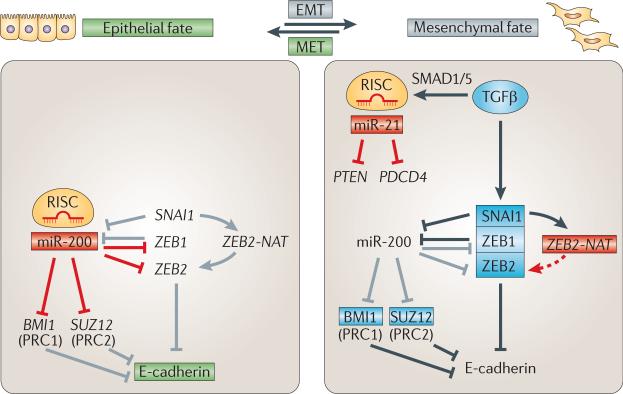

Mesenchymal cells are often migratory and undifferentiated, whereas epithelia are characterized by apical–basal polarity and E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion. EMT is associated with repression of E-cadherin expression by the zinc finger transcription factors homologue of Snail (SNAI1), ZEB1 and ZEB2 (reviewed in REF. 146). Because these repressors function as inducers of EMT in many cellular contexts, their activities are tightly regulated. In epithelia, ZEB1 and ZEB2 mRNAs are repressed by miR-200 family members141–143. In turn, mesenchymal expression of miR-200 is repressed by ZEB1 and SNAI1 (REFS 147,148), revealing a bistable loop that regulates EMT (FIGS 3,7). Additional support for this notion comes from the observation that forced transcription of miR-200 in mesenchymal cells is sufficient to induce epithelial properties in vitro141,143.

Figure 7. Regulation of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by non-coding RNAs.

Scheme of non-coding RNA (ncRNA)-mediated control of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). miR-200 has a central role in stabilizing the epithelial state (green) by repressing negative regulators of E-cadherin expression. In epithelia, miR-200 targets subunits of Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) (BMI1) and PRC2 (SUZ12) as well as the transcription factors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Conversely, transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ)-induced ZEB1, ZEB2 and homologue of Snail (SNAI1) repress miR-200 and E-cadherin and promote mesenchymal fate (grey). Additional mechanisms that are implicated in inducing EMT include the positive-feedforward loop featuring the SNAI1-induced natural antisense transcript of ZEB2 (ZEB2-NAT) as well as TGFβ-induced maturation of primary miR-21 (pri-miR-21). For further details, see the main text. Red boxes indicate active miRNAs; light blue boxes indicate active proteins; unboxed text indicates inactive genes/miRNAs; grey lines indicate inactive processes. PDCD4, programmed cell death 4; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue; MET, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex.

In contrast to miR-200, which represses ZEB2 activity and stabilizes the epithelial state, an antisense lncRNA in the ZEB2 locus — ZEB2 natural antisense transcript (ZEB2-NAT) — increases ZEB2 protein levels149. ZEB2-NAT binds to the pre-ZEB2 mRNA and prevents splicing of an intron that contains an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). Retention of this IRES is essential for efficient ZEB2 mRNA translation and thus for robust inhibition of E-cadherin expression in mesenchymal cells. SNAI1 activates ZEB2-NAT transcription149 and thus represses E-cadherin, both directly, by binding to the E-cadherin promoter, and indirectly, by promoting ZEB2 translation (FIG. 7). These results suggest that lncRNAs not only function at the level of chromatin but can also act as splicing regulators.

Another miRNA involved in EMT is miR-21. It represses tumour suppressors such as programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) and phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)150,151 to induce de-differentiation and increased motility and invasiveness. Pri-miR-21 to pre-miR-21 maturation is promoted by TGFβ signalling, a well-known inducer of EMT. TGFβ-induced nuclear translocation of SMAD proteins results in SMAD binding to specific pri-miRNA stems (for example, pri-miR-21), the recruitment of the DROSHA microprocessor complex and increased efficiency of miRNA maturation152,153 (FIG. 7). These findings show how developmental signalling pathways can influence miRNA processing.

Prospects

The discovery of a plethora of novel, presumably noncoding transcripts of unknown function was first met with scepticism. Why would an organism generate a universe of RNAs? Even though recent RNA-seq analyses indicate that the transcribed fraction of the genome may not be as large as initial microarray studies suggested, functional analyses have started to shed light on their biological activities (reviewed in REFS 11,14). Still, the large majority of ncRNAs have no assigned functions, underlining the need for comprehensive loss-of-function studies. Assigning functions to ncRNAs is likely to be a challenge, as systematic miRNA knockout studies in C. elegans show that single and even double and triple mutants do not result in easily recognizable phenotypes28,154,155. Moreover, misexpression studies do not necessarily reflect the in vivo requirement for an ncRNA135. The task is further complicated by the possibility that disruption of ncRNA sequences not only results in changes in ncRNA activity but may also interfere with the activity of overlapping cis-acting elements that regulate gene expression. Regardless of these challenges, there is a great need to move from expression and cell culture studies to functional analyses of miRNA and lncRNA function in vivo.

It is still largely unclear how the great diversity of embryonic forms has evolved, despite a limited set of regulatory proteins. Genomic studies show that miRNAs were continuously added to metazoan genomes through time, and that a large proportion of predicted target sites is not conserved between different species22,156,157. The ease by which 3′ UTRs can lose or gain miRNA target sites greatly facilitates phenotypic changes. For example, a point mutation in the 3′ UTR of myostatin renders this mRNA responsive to miR-206 and results in sheep with increased muscle mass158. Detailed comparative studies are likely to uncover intriguing principles of metazoan evolution for ncRNAs small and large alike.

We must also keep in mind that putative non-coding transcripts could encode small peptides. This possibility has been raised by the discoveries that the D. melanogaster gene polar granule component (pgc) encodes a small protein159 and that the polycistronic RNA polished rice (pri) encodes several small peptides that control the activity of the transcription factor Shavenbaby160,161. Conversely, protein-coding mRNAs might have functions as RNAs. For example, human tumour suppressor p53 (TP53)162 and D. melanogaster Oskar163 function at both the protein and RNA level. our expanding knowledge of ncRNA function in metazoans and the numerous studies of ncRNAs in prokaryotes164 raise the possibility that the roles of RNAs will be even more pervasive than is currently perceived.

miRNAs

(MicroRNAs). ssRNAs of ~ 22 bp that act as guides for RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)-mediated repression of partially complementary target genes. Biogenesis of most miRNAs requires the stepwise activity of two RNase III endonuclease complexes, nuclear Drosha–DGCR8 and cytoplasmic Dicer.

lncRNAs

(Long non-coding RNAs). Transcripts that resemble protein-coding mRNAs in that they are capped, spliced and polyadenylated RNA polymerase II transcripts; they differ from mRNAs only in their lack of a protein-coding ORf.

endo-siRNAs

(Endogenous small interfering RNAs). Small RNAs that originate, in a Dicer-dependent manner, from long double-stranded (sense–antisense or hairpin) precursors. Initially mainly thought of as a mechanism of host defence against exogenous dsRNA, endo-siRNAs are now known to also regulate endogenous mRNAs in mouse oocytes and Caenorhabditis elegans.

piRNAs

(PIWI-interacting RNAs). Small (24–31 bp) RNAs that are associated with PIWI-clade proteins of the Argonaute family. They ensure genome stability in the germ line of flies, mice and zebrafish by silencing transposable and repetitive elements.

lincRNAs

(Large intergenic non-coding RNAs). A subgroup of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that originate from intergenic regions.

Drosha

The double-stranded RNA processing enzyme that catalyses the nuclear primary microRNA (pri-miRNA) to precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) cleavage reaction.

DGCR8

The essential RNA-binding cofactor of Drosha; DGCR8 and Drosha are core proteins of the so-called microprocessor complex that promotes nuclear primary microRNA (pri-miRNA) to precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) processing during canonical microRNA biogenesis.

Dicer

The dsRNA processing enzyme that catalyses the final cytoplasmic precursor microRNA (pre-miRNA) cleavage reaction to generate mature miRNAs during canonical miRNA biogenesis; Dicer also promotes processing of endogenous small interfering RNA (endo-siRNA) precursors to generate mature endo-siRNAs.

RNA-induced silencing complex

(RISC). The RISC complex contains the single-stranded, ~ 22 bp miRNA and proteins of the Argonaute family. The miRNA acts as guide for the Argonaute proteins, which mediate the repression of the target mRNA.

Germ layers

Cell layers that are specified in a transforming growth factor-β (TGfβ)-signalling dependent manner after the initial embryonic cleavage stages. Each of the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm) gives rise to specific tissues and organs during later embryogenesis.

Deadenylation

The process of removal of the 3’ poly(A) tail of mRNAs, which leads to their destabilization and subsequent degradation; deadenylation is mainly mediated by the CAF1–CCR4 deadenylase complex and contributes to the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)-mediated repression of target mRNAs.

Primordial germ cells

(PGCs). Embryonic cells that give rise to germ cells from which the haploid gametes (oocytes in females and sperm in males) differentiate.

Induced pluripotent stem cells

(iPs cells). In vitro-derived pluripotent stem cells that originate from non-pluripotent somatic cells in a process called reprogramming.

Dosage compensation

A process that equalizes levels of X-linked gene expression in XX females and XY males.

Epigenetic

An epigenetic change is an inherited phenotypic change that is caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence.

Polycomb

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are epigenetic regulators of gene expression that silence target genes by establishing a repressive chromatin state. Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) trimethylates histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3). This repressive histone modification is recognized by PRC1, which has ubiquitylating activity. Because of their role in maintaining states of gene expression, PRCs have key roles in cell fate maintenance and transitions during development.

Hox genes

Hox genes represent an ancestral embryonic patterning mechanism that specifies segmental identities along the anterior–posterior body axis in all bilateria. Hox genes encode homeobox transcription factors that are arranged in clusters. Expression of paralogous Hox genes within a cluster is tightly regulated both spatially and temporally; misexpression causes dramatic alterations in the embryonic body plan (homeotic transformations).

Acknowledgements

We thank G.-L. Chew and O. Minkina for critical reading of the manuscript, and E. Valen, E. Alvarez-Saavedra, S. Cohen, R. Gregory, O. Hobert and members of the Schier laboratory for discussions. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants to A.F.S. and J.L.R. and by fellowships from the European Molecular Biology Organization (ALTF 372-2009) and The Human Frontier Science Program (LT-000307/2010) to A.P.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

FURTHER INFORMATION

John L. Rinn's homepage: http://www.rinnlab.com Alexander F. Schier's homepage: http://www.mcb.harvard.edu/faculty/faculty_profile.php?f=alex-schier

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

See online article: S1 (table)

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown CJ, et al. The human XIST gene: analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell. 1992;71:527–542. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90520-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brockdorff N, et al. The product of the mouse Xist gene is a 15 kb inactive X-specific transcript containing no conserved ORF and located in the nucleus. Cell. 1992;71:515–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90519-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borsani G, et al. Characterization of a murine gene expressed from the inactive X chromosome. Nature. 1991;351:325–329. doi: 10.1038/351325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob F, Monod J. Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1961;3:318–356. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Britten RJ, Davidson EH. Gene regulation for higher cells: a theory. Science. 1969;165:349–357. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3891.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattick JS, Taft RJ, Faulkner GJ. A global view of genomic information-moving beyond the gene and the master regulator. Trends Genet. 2009;26:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacquier A. The complex eukaryotic transcriptome: unexpected pervasive transcription and novel small RNAs. Nature Rev. Genet. 2009;10:833–844. doi: 10.1038/nrg2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carninci P. Molecular biology: the long and short of RNAs. Nature. 2009;457:974–975. doi: 10.1038/457974b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercer T, Dinger M, Mattick J. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nature Rev. Genet. 2009;10:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koziol MJ, Rinn JL. RNA traffic control of chromatin complexes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010;20:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE. Epigenetic inheritance in plants. Nature. 2007;447:418–424. doi: 10.1038/nature05917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wollmann H, Weigel D. Small RNAs in flower development. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2010;89:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chitwood DH, Timmermans MC. Small RNAs are on the move. Nature. 2010;467:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature09351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swiezewski S, Liu F, Magusin A, Dean C. Cold-induced silencing by long antisense transcripts of an Arabidopsis Polycomb target. Nature. 2009;462:799–802. doi: 10.1038/nature08618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamura K, Lai EC. Endogenous small interfering RNAs in animals. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:673–678. doi: 10.1038/nrm2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nature Rev. Genet. 2009;10:94–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giraldez AJ, et al. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science. 2005;308:833–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1109020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giraldez AJ, et al. Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science. 2006;312:75–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1122689. [This study demonstrates that a single miRNA family promotes the concerted elimination of hundreds of maternal RNAs in zebrafish and thereby sharpens the transition between maternal and zygotic gene expression programmes. The authors furthermore show that miR-430 destabilizes target mRNAs by causing their deadenylation.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi W-Y, Giraldez AJ, Schier AF. Target protectors reveal dampening and balancing of Nodal agonist and antagonist by miR-430. Science. 2007;318:271–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1147535. [This study provides evidence for the physiological role of specific miRNA–mRNA interactions. Interference with miR-430 targeting of the Nodal agonist and antagonist by ‘target protectors’ identifies essential roles for miR-430 in regulating this key embryonic signalling pathway.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature Genet. 2007;39:380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh N, et al. MicroRNA function is globally suppressed in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang F, et al. Maternal microRNAs are essential for mouse zygotic development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:644–648. doi: 10.1101/gad.418707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murchison EP, et al. Critical roles for Dicer in the female germline. Genes Dev. 2007;21:682–693. doi: 10.1101/gad.1521307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez-Saavedra E, Horvitz HR. Many families of C. elegans microRNAs are not essential for development or viability. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.051. [To date, this study provides the most comprehensive analyses of miRNA function in vivo. Loss-of-function mutants for individual as well as all members of redundantly acting miRNA families often revealed no or only subtle phenotypes. These results highlight the importance and challenge of miRNA loss-of-function analyses.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner JL, Jasiewicz KL, Fahley AF, Kemp BJ, Abbott AL. Loss of individual microRNAs causes mutant phenotypes in sensitized genetic backgrounds in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tadros W, Lipshitz HD. The maternal-to-zygotic transition: a play in two acts. Development. 2009;136:3033–3042. doi: 10.1242/dev.033183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schier AF. The maternal-zygotic transition: death and birth of RNAs. Science. 2007;316:406–407. doi: 10.1126/science.1140693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lund E, Liu M, Hartley RS, Sheets MD, Dahlberg JE. Deadenylation of maternal mRNAs mediated by miR-427 in Xenopus laevis embryos. RNA. 2009;15:2351–2363. doi: 10.1261/rna.1882009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bushati N, Stark A, Brennecke J, Cohen SM. Temporal reciprocity of miRNAs and their targets during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu E, et al. Pervasive and cooperative deadenylation of 3’UTRs by embryonic MicroRNA families. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:558–570. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouget C, et al. Maternal mRNA deadenylation and decay by the piRNA pathway in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 2010;467:1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature09465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mishima Y, et al. Differential regulation of germline mRNAs in soma and germ cells by zebrafish miR-430. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:2135–2142. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kedde M, et al. RNA-binding protein Dnd1 inhibits microRNA access to target mRNA. Cell. 2007;131:1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.034. [This study describes one of the first examples for mechanisms that modulate miRNA activity. The conserved RNA-binding protein DND1 counteracts miRNA-mediated repression in human cells and zebrafish primordial germ cells.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeda Y, Mishima Y, Fujiwara T, Sakamoto H, Inoue K. DAZL relieves miRNA-mediated repression of germline mRNAs by controlling poly(A) tail length in zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kee K, Angeles VT, Flores M, Nguyen HN, Reijo Pera RA. Human DAZL, DAZ and BOULE genes modulate primordial germ-cell and haploid gamete formation. Nature. 2009;462:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature08562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landgraf P, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernstein E, et al. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nature Genet. 2003;35:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murchison EP, Partridge JF, Tam OH, Cheloufi S, Hannon GJ. Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc.Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12135–12140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505479102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanellopoulou C, et al. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 2005;19:489–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1248505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, et al. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs regulate the G1-S transition and promote rapid proliferation. Nature Genet. 2008;40:1478–1483. doi: 10.1038/ng.250. [This paper provides compelling evidence that miRNAs are essential for ES cell self-renewal. Expression of a single miRNA family member of the ESCC miRNAs can rescue the proliferation defect of ES cells that lack mature miRNAs.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Judson RL, Babiarz JE, Venere M, Blelloch R. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs promote induced pluripotency. Nature Biotech. 2009;27:459–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melton C, Judson RL, Blelloch R. Opposing microRNA families regulate self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2010;463:621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature08725. [This study presents evidence that two opposing families of miRNAs control ES cell maintenance and differentiation. Self-renewal-promoting ESCC miRNAs (see also reference 44) are antagonized by let-7, which functions as a regulator of ES cell differentiation.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson CD, et al. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7713–7722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rybak A, et al. The let-7 target gene mouse lin-41 is a stem cell specific E3 ubiquitin ligase for the miRNA pathway protein Ago2. Nature Cell Biol. 2009;11:1411–1420. doi: 10.1038/ncb1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Keys DN, Au-Young JK, Chen C. MicroRNAs in embryonic stem cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2009;218:251–255. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marson A, et al. Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, Thomson J, Kosik K. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newman MA, Thomson JM, Hammond SM. Lin-28 interaction with the Let-7 precursor loop mediates regulated microRNA processing. RNA. 2008;14:1539–1549. doi: 10.1261/rna.1155108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viswanathan S, Daley G, Gregory R. Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science. 2008;320:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1154040. [References 52 and 53 identify the stem cell factor and RNA-binding protein LIN28 as an inhibitor of let-7 maturation.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heo I, et al. Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor MicroRNA. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rybak A, et al. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:987–993. doi: 10.1038/ncb1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nature Rev. Genet. 2010;11:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakagawa M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nature Biotech. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.West JA, et al. A role for Lin28 in primordial germ-cell development and germ-cell malignancy. Nature. 2009;460:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature08210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guttman M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [In this first comprehensive study of lncRNAs, the authors use the chromatin signature of RNA polymerase II-transcribed regions (H3K4me3 and H3K36me3) to identify lincRNAs in four mouse cell types. Many of these lincRNAs are predicted to function in a wide range of biological processes.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guttman M, et al. Ab initio reconstruction of cell type-specific transcriptomes in mouse reveals the conserved multi-exonic structure of lincRNAs. Nature Biotech. 2010;28:503–510. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheik Mohamed J, Gaughwin PM, Lim B, Robson P, Lipovich L. Conserved long noncoding RNAs transcriptionally regulated by Oct4 and Nanog modulate pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. RNA. 2009;16:324–337. doi: 10.1261/rna.1441510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dinger ME, et al. Long noncoding RNAs in mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Genome Res. 2008;18:1433–1445. doi: 10.1101/gr.078378.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Loewer S, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature Genet. 2010;42:1113–1117. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schier AF. Nodal morphogens. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009;1:a003459. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martello G, et al. MicroRNA control of Nodal signalling. Nature. 2007;449:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature06100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosa A, Spagnoli FM, Brivanlou AH. The miR-430/427/302 family controls mesendodermal fate specification via species-specific target selection. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flynt AS, Li N, Thatcher EJ, Solnica-Krezel L, Patton JG. Zebrafish miR-214 modulates Hedgehog signaling to specify muscle cell fate. Nature Genet. 2007;39:259–263. doi: 10.1038/ng1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leucht C, et al. MicroRNA-9 directs late organizer activity of the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Nature Neurosci. 2008;11:641–648. doi: 10.1038/nn.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y, Wang F, Lee J-A, Gao F-B. MicroRNA-9a ensures the precise specification of sensory organ precursors in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2793–2805. doi: 10.1101/gad.1466306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lai EC, Tam B, Rubin GM. Pervasive regulation of Drosophila Notch target genes by GY-box-, Brd-box-, and K-box-class microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1067–1080. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee JT. Lessons from X-chromosome inactivation: long ncRNA as guides and tethers to the epigenome. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1831–1842. doi: 10.1101/gad.1811209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koerner MV, Pauler FM, Huang R, Barlow DP. The function of non-coding RNAs in genomic imprinting. Development. 2009;136:1771–1783. doi: 10.1242/dev.030403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schmidt JV, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM. Enhancer competition between H19 and Igf2 does not mediate their imprinting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9733–9738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mancini-Dinardo D, Steele SJ, Levorse JM, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. Elongation of the Kcnq1ot1 transcript is required for genomic imprinting of neighboring genes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1268–1282. doi: 10.1101/gad.1416906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sleutels F, Zwart R, Barlow DP. The non-coding Air RNA is required for silencing autosomal imprinted genes. Nature. 2002;415:810–813. doi: 10.1038/415810a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Umlauf D, et al. Imprinting along the Kcnq1 domain on mouse chromosome 7 involves repressive histone methylation and recruitment of Polycomb group complexes. Nature Genet. 2004;36:1296–1300. doi: 10.1038/ng1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nagano T, et al. The Air noncoding RNA epigenetically silences transcription by targeting G9a to chromatin. Science. 2008;322:1717–1720. doi: 10.1126/science.1163802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pandey RR, et al. Kcnq1ot1 antisense noncoding RNA mediates lineage-specific transcriptional silencing through chromatin-level regulation. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:232–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.022. [References 77 and 78 demonstrate essential roles for imprinted lncRNAs in recruiting chromatin modifiers to neighbouring genes, resulting in monoallelic silencing of entire gene clusters in cis.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Terranova R, et al. Polycomb group proteins Ezh2 and Rnf2 direct genomic contraction and imprinted repression in early mouse embryos. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:668–679. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mohammad F, Mondal T, Guseva N, Pandey GK, Kanduri C. Kcnq1ot1 noncoding RNA mediates transcriptional gene silencing by interacting with Dnmt1. Development. 2010;137:2493–2499. doi: 10.1242/dev.048181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haig D. Genomic imprinting and kinship: how good is the evidence? Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:553–585. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Penny GD, Kay GF, Sheardown SA, Rastan S, Brockdorff N. Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature. 1996;379:131–137. doi: 10.1038/379131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ogawa Y, Sun BK, Lee JT. Intersection of the RNA interference and X-inactivation pathways. Science. 2008;320:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1157676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kanellopoulou C, et al. X chromosome inactivation in the absence of Dicer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1122–1127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812210106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun BK, Deaton AM, Lee JT. A transient heterochromatic state in Xist preempts X inactivation choice without RNA stabilization. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tian D, Sun S, Lee JT. The long noncoding RNA, Jpx, is a molecular switch for X chromosome inactivation. Cell. 2010;143:390–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wutz A, Rasmussen TP, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal silencing and localization are mediated by different domains of Xist RNA. Nature Genet. 2002;30:167–174. doi: 10.1038/ng820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Navarro P, Page DR, Avner P, Rougeulle C. Tsix-mediated epigenetic switch of a CTCF-flanked region of the Xist promoter determines the Xist transcription program. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2787–2792. doi: 10.1101/gad.389006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song J-J, Lee JT. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science. 2008;322:750–756. doi: 10.1126/science.1163045. [Analogous to the function of imprinted ncRNAs (see references 77 and 78), this study provides evidence that a conserved ncRNA originating from the Xic recruits repressive chromatin-modifying complexes of the Polycomb group family (PRC2) incis. Recruitment of PRC2 is essential for the nucleation of silencing of one entire X chromosome in mammalian females.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gelbart ME, Kuroda MI. Drosophila dosage compensation: a complex voyage to the X chromosome. Development. 2009;136 doi: 10.1242/dev.029645. 1399–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Akhtar A, Becker PB. Activation of transcription through histone H4 acetylation by MOF, an acetyltransferase essential for dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meller VH, Rattner BP. The roX genes encode redundant male-specific lethal transcripts required for targeting of the MSL complex. EMBO J. 2002;21:1084–1091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]