INTRODUCTION

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) most recently published recommendations for use of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologics in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 2008 (1). These recommendations covered indications for use, monitoring of side-effects, assessment of the clinical response to DMARDs and biologics, screening for tuberculosis (TB), and assessment of the roles of cost and patient preference in decision-making for biologic agents (1). Recognizing the rapidly evolving knowledge in RA management and the accumulation of new evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of existing and newer therapies, the ACR commissioned an update of the 2008 recommendations in select topic areas.

The 2012 revision updates the 2008 ACR recommendations in the following areas: (1) indications for DMARDs and biologics; (2) switching between DMARD and biologic therapies; (3) use of biologics in high-risk patients (those with hepatitis, congestive heart failure, and malignancy); (4) screening for TB in patients starting or currently receiving biologics; and (5) vaccination in patients starting or currently receiving DMARDs or biologics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview Comparison of Topics and Medications Included in the 2008 and 2012 ACR RA Recommendations

| TOPIC AREA CONSIDERED | 2008 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|

| Indications for starting or resuming DMARDs and biologics | X | X |

| DMARDs Included1 |

|

|

| and, when appropriate, combination DMARD therapy with two or three DMARDs1 | and, when appropriate, combination DMARD therapy with two or three DMARDs2 | |

| Biologics Included3 | Non-TNF

|

Non-TNF

|

Anti-TNF

|

Anti-TNF

|

|

| Role of cost and patient preference in decision-making for biologics | X | see 2008 recommendations4 |

| Switching between therapies | Considered, but not addressed in detail | X |

| Monitoring of side-effects of DMARDs and biologics | X | see 2008 recommendations4 |

| TB screening for patients starting/receiving biologics | X | X |

| Use of biologics in high-risk patients (those with hepatitis, congestive heart failure and malignancy) | X | X |

| Vaccinations in patients starting/receiving DMARDs or biologics | pneumococcal, influenza and hepatitis vaccines | pneumococcal, influenza, hepatitis, human papilloma, and herpes zoster vaccines |

Cyclosporine, Azathioprine and gold were included in the literature search, but due to lack of new data and/or infrequent use, were not included in scenarios and the recommendations

Triple therapy with methotrexate + hydroxychloroquine + sulfasalazine

Anakinra was included in the literature search, but due to lack of new data and/or infrequent use, was not included in the recommendations not included due to lack of new data and infrequent use

No significant new data related to these topics

METHODS

We utilized the same methodology as described in detail in the 2008 guidelines (1) to maintain consistency and to allow cumulative evidence to inform this 2012 recommendation update. These recommendations were developed by two expert panels: (1) a non-voting working group and Core Expert Panel (CEP) of clinicians and methodologists responsible for the selection of the relevant topic areas to be considered, the systematic literature review, and the evidence synthesis and creation of “clinical scenarios”; and (2) a Task Force Panel (TFP) of 11 internationally-recognized expert clinicians, patient representatives and methodologists with expertise in RA treatment, evidence-based medicine and patient preferences who were tasked with rating the scenarios created using an ordinal scale specified in the Research and Development/University of California at Los Angeles (RAND/UCLA) Appropriateness method (2–4). This method solicited formal input from a multi-disciplinary TFP panel to make recommendations informed by the evidence. The methods used to develop the updated ACR recommendations are described briefly below.

Systematic Literature Review – Sources, Databases and Domains

Literature searches for both DMARDs and biologics relied predominantly on PubMed searches) with medical subject headings (MeSH) and relevant keywords similar to those used for the 2008 ACR RA recommendations (see Appendices 1 and 2). We included randomized clinical trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), quasi-experimental designs, cohort studies (prospective or retrospective), and case-control studies, with no restrictions on sample size. More details about inclusion criteria are listed below and in Appendix 3.

The 2008 recommendations were based on a literature search that ended on February 14, 2007. The literature search end date for the 2012 Update was February 26, 2010 for the efficacy and safety studies and September 22, 2010 for additional qualitative reviews related to TB screening, immunization and hepatitis (similar to the 2008 methodology). Studies published subsequent to that date were not included.

For biologics, we also reviewed the Cochrane systematic reviews and overviews (published and in press) in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to identify additional studies (5–8) and further supplemented by hand-checking the bibliographies of all included articles. Finally, the CEP and TFP confirmed that relevant literature was included for evidence synthesis. Unless they were identified by the literature search and met the article inclusion criteria (see Appendix 3), we did not review any unpublished data from product manufacturers, investigators, or the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System.

We searched the literature for the eight DMARDs and nine biologics most commonly used for the treatment of RA. Literature was searched for eight DMARDS including azathioprine, cyclosporine, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, minocycline, organic gold compounds and sulfasalazine. As in 2008, azathioprine, cyclosporine and gold were not included in the recommendations based on infrequent use and lack of new data (Table 1). Literature was searched for nine biologics including abatacept, adalimumab, anakinra, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab and tocilizumab; anakinra was not included in the recommendations due to infrequent use and lack of new data. Details of the bibliographic search strategy are listed in Appendix 1.

Literature Search Criteria and Article Selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for review of article abstracts and titles

With the exception of assessment of TB, hepatitis and vaccination (see below), studies were included if they met all of the following criteria: (1) original study in English language with an abstract; (2) observational studies (case-control or cohort) or intervention studies; (3) related to the treatment of RA with DMARDs or biologics; and (4) study duration of at least six months (see Appendix 2)..

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) the report was a meeting abstract, review article or meta-analysis; (2) study duration was less than six months; (3) DMARDs or biologics were used for non-RA conditions (e.g., psoriatic arthritis, systematic lupus erythematosus), or non-FDA approved use in health conditions other than RA (e.g., biologics in vasculitis) (Appendix 2).

Selection criteria for articles reviewing efficacy/adverse events

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of 2,497 potential articles from the PubMed and Cochrane Library searches by applying the above selection method. Any disagreements were resolved by consultation with the lead reviewer (JAS). The lead author also reviewed all titles and abstracts to identify any that might have been overlooked. We identified 149 original articles from the three searches for full text retrieval. After excluding duplicates, 128 unique original articles were identified and data were abstracted. This included 16 articles focused on DMARDs and 112 on biologics (98 on the six biologics assessed in the 2008 RA recommendations; 14 on certolizumab pegol, golimumab and tocilizumab, three newer biologics which had been added since the 2008 recommendations; Appendix 3). A list of all included articles is provided in Appendix 4.

Additional literature searches for articles reviewing TB screening, hepatitis and vaccination

Qualitative reviews of the literature were performed for these three topics (completed September 22, 2010). Similar to the strategy for the 2008 recommendations, literature searches were broadened to include case reports and case series of any size, review articles, meta-analyses, plus inclusion of diseases other than RA. In addition, we included searches on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website for past and current recommendations regarding TB screening and vaccination in immunocompromised patients (www.cdc.gov).

Agreement between Reviewers for Selection of Studies for Full Text Retrieval

The kappa coefficients (agreement beyond chance) for independent selection of articles for full-text review by the two reviewers met or exceeded 0.60 (good) for DMARDs, 0.65 (very good) for the six biologics included in the 2008 ACR recommendations and 0.84 (excellent) for a combination of certolizumab pegol, golimumab and tocilizumab (9).

Full Text Article Review, Data Abstraction, Data Entry, and Evidence Report Generation

The full-text of each article was reviewed; data abstraction and entry was performed by reviewers using the standardized Microsoft Access® database (Redmond, WA) that was developed and used for data abstraction for the 2008 ACR RA recommendations. Two reviewers were assigned to abstract data on DMARDs (SB, DF), rituximab (HA, LV), and the rest of the biologics (AB, AJ). To ensure that error rates were low and abstractions similar, 26 articles related to biologics were dually abstracted by two abstractors (AB, AJ). The data entry errors were less than 3%. Entered data was further checked against raw data on biologics from the Cochrane systematic reviews (5–8). Following this comprehensive literature review, we developed an evidence report using the data abstracted from the published studies.

Clinical Scenarios Development

Clinical scenarios were drafted by the investigators and the CEP, based on the updated evidence report. We used the same key determinant clinical thresholds and treatment decision branch points that were developed for the 2008 ACR RA treatment recommendations (1). Clinical scenarios were constructed based on permutations in the particular therapeutic considerations that reflected: 1) disease duration (early versus established RA); 2) disease activity (low, moderate or high; Tables 2 and 3 and Appendix 5); 3) current medication regimen; and 4) presence of poor prognostic factors (yes or no, as defined in the 2008 ACR recommendations). An example of a clinical scenario is: “The patient has active established RA and has failed an adequate trial of an Anti-TNF biologic because of adverse events. Is it appropriate to switch to another Anti-TNF biologic after failing etanercept?” (Appendix 6) Scenarios included both new considerations and questions considered in the 2008 recommendations.

Table 2.

Key Assumptions for Clinical Scenarios and Definitions of Key Terms for 2012 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations Update for the Treatment of RA

| Key assumptions |

|---|

|

| Key Terms | Definitions |

|---|---|

| DMARDs2 | Hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, minocycline or sulfasalazine |

| Non-Methotrexate DMARDs | Hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, minocycline or sulfasalazine |

| DMARD combination-therapy | Combinations including two drugs, most of which are methotrexate-based with only a few exceptions (for example, methotrexate + hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate + leflunomide, methotrexate + sulfasalazine, sulfasalazine + hydroxychloroquine) and triple therapy (methotrexate + hydroxychloroquine + sulfasalazine) |

| Anti-TNF biologics | Adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, infliximab or golimumab |

| Non-TNF biologics | Abatacept, rituximab or tocilizumab |

| Biologics | Anti-TNF biologic or non-TNF biologic (eight biologics excluding anakinra) |

| Early RA | RA disease duration < 6 months |

| Established RA | RA disease duration ≥ 6 months or meeting 1987 ACR Classification Criteria (24) 3 |

| Disease activity | Categorized as low, moderate, and high as per validated common scales (Table 3 and Appendix 4) or the treating clinician’s formal assessment (26–32) |

| Poor prognosis | Presence of one or more of the following features: functional limitation (e.g., HAQ-DI or similar valid tools); extra-articular disease (e.g., presence of rheumatoid nodules, RA vasculitis, Felty’s syndrome); positive rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (33–37); bony erosions by radiograph (38–40) |

| RA remission | A joint ACR-EULAR task force defined remission as a tender joint count, swollen joint count, C-reactive protein (mg/dl) and patient global assessment ≤ 1 each or a Simplified Disease Activity Score of ≤ 3.3 (41) |

| Child-Pugh classification | Scoring system based upon the levels of albumin, total bilirubin and prothrombin time, and the presence of ascites and encephalopathy. Patients with a score of 10 or more (in the Class C category) have a prognosis with 1-year survival of about 50%. Patients with Class A or B have a better 5-year prognosis, with a survival rate of 70%–80% (12). |

| NYHA class III and IV | NYHA class III includes patients with cardiac disease resulting in marked limitation of physical activity with less than ordinary physical activity causing fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or anginal pain, but no symptoms at rest. NYHA class IV includes patients with cardiac disease resulting in inability to carry on any physical activity without discomfort and symptoms of cardiac insufficiency or that the anginal syndrome may be present even at rest, which increases if any physical activity is undertaken (13). |

| CDC defined risk factors for Latent TB Infection (LTBI) | Close contacts of persons known or suspected to have active tuberculosis; foreign-born persons from areas with a high incidence of active tuberculosis (e.g., Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Russia); persons who visit areas with a high prevalence of active tuberculosis, especially if visits are frequent or prolonged; residents and employees of congregate settings whose clients are at increased risk for active tuberculosis (e.g., correctional facilities, long-term care facilities, and homeless shelters); health-care workers who serve clients who are at increased risk for active tuberculosis; populations defined locally as having an increased incidence of latent M. tuberculosis infection or active tuberculosis, possibly including medically underserved, low-income populations, or persons who abuse drugs or alcohol; and infants, children, and adolescents exposed to adults who are at increased risk for latent M. tuberculosis infection or active tuberculosis (14). |

Agreement as defined by the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method

Azathioprine, cyclosporine and gold were considered but not included due to their infrequent use in RA and/or lack of new data since 2008

New classification criteria for RA (ACR-EULAR collaborative initiative) have been published (23); however, the evidence available for these 2011 recommendations relied on the use of 1987 ACR RA classification criteria, since literature review preceded the publication of the new criteria. We anticipate that in the near future, data using the new classification criteria may be available for evidence synthesis and formulating recommendations.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CHF, Congestive Heart Failure; DMARD, Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drug; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RA, Rheumatoid Arthritis; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; HAQ-DI, Health assessment questionnaire; DAS, Disease Activity Score

Table 3.

Instruments to Measure Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity and to Define Remission

| Instrument | Thresholds of Disease Activity Levels |

|---|---|

| Patient Activity Scale (PAS) or PASII (31) Range 0 – 10 |

Remission: 0 – 0.25 Low activity: > 0.25–3.7 Moderate activity: > 3.7 – < 8.0 High activity: ≥ 8.0 |

| Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3) (42) Range 0 – 10 |

Remission: 0–1.0 Low activity: > 1.0–2.0 Moderate activity: > 2.0–4.0 High activity: > 4.0–10 |

| Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) (43) Range 0 – 76.0 |

Remission: ≤ 2.8 Low activity: > 2.8–10.0 Moderate activity: 1> 10.0–22.0 High activity: > 22 |

| Disease Activity Score (DAS) 281 (44) Range 0 – 9.4 |

Remission: < 2.6 Low activity: ≥ 2.6 – < 3.2 Moderate activity: ≥ 3.2 – ≤ 5.1 High activity: > 5.1 |

| Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) (45) Range 0 – 86.0 |

Remission: ≤ 3.3 Low activity: > 3.3 – ≤ 11.0 Moderate activity: > 11.0 – ≤ 26 High activity: > 26 |

DAS28: disease activity score based on 28 joint counts

For this 2012 update, we used a modified Delphi process and obtained consensus (defined as ≥70% agreement) from the CEP for inclusion of relevant clinical scenarios based on: (1) review of each of the previous 2008 scenarios; and (2) review of newly developed scenarios to address switching between therapies. We provided CEP members with manuscript abstracts and requested full-text articles to help inform decisions.

The CEP members also recommended the following: (1) use of the FDA definitions of “serious” and “non-serious” adverse events (10); (2) exclusion of three DMARDs used very infrequently (i.e., cyclosporine, azathioprine, gold—see above) or without additional relevant new data; and (3) exclusion of one biologic without additional relevant new evidence and infrequent use (anakinra).

Rating the Appropriateness of Clinical Scenarios by the Task Force Panel (TFP)

The TFP is referred to as the “panel” in the methods and the recommendations that follow. For the first round of ratings we contacted panel members by email and provided them with the evidence report, clinical scenarios, and rating instructions. We asked them to use the evidence report and their clinical judgments to rate the “appropriateness” of clinical scenarios under consideration. The panelists individually rated each scenario permutation using a 9-point Likert appropriateness scale. A median score of 1 to 3 indicated “not appropriate” and 7 to 9 indicated “appropriate” for taking action defined in the scenario (2–4). For all eventual recommendations, the RAND-UCLA appropriateness panel score required a median rating of 7 to 9. Those scenario permutations with median ratings in the 4 to 6 range and those with disagreement among the panelists (i.e., one-third or more TFP members rating the scenario in the 1 to 3 range and one-third or more rating it in the 7 to 9 range) were classified as “uncertain.” At a face-to-face meeting with both the TFP and the CEP members on November 15, 2010, the anonymous the first round of ratings by the panel – including dispersion of the scores, ranges and median scores –. were provided to the task force panelists.

The task force panelists agreed upon certain assumptions and qualifying statements on which they based their discussion and subsequent ratings of the scenarios (Table 2). A second round of ratings by panel members occurred after extensive in person discussion of the prior ratings and evidence supporting each scenario.

Conversion of Clinical Scenarios to ACR RA Treatment Recommendations

After the TFP meeting was complete, recommendations were derived from directly transcribing final clinical scenario ratings. Based on the ratings, scenario permutations were collapsed to yield the most parsimonious recommendations. For example, when ratings favored a drug indication for both moderate and high disease activity, one recommendation was given, specifying “moderate or high disease activity.” In most circumstances, the recommendations included only positive and not negative statements. For example, the recommendations focused on when to initiate specific therapies rather than when an alternate therapy should not be used. Most of the recommendations were formulated by drug category (DMARD, anti-TNF biologic, non-TNF biologic listed alphabetically within category), since in many instances, the ratings were similar for medications within a drug category. We specifically note instances where a particular medication was recommended but others in its group were not endorsed. Two additional community-based rheumatologists (Drs. Anthony Turkiewicz and Gary Feldman) independently reviewed the manuscript and provided comments. CEP and TFP members reviewed and approved all final recommendations.

For each final recommendation, the strength of evidence was assigned using the methods from the American College of Cardiology (11). Three levels of evidence are specified: 1) Level of Evidence A: data were derived from multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs) ; 2) Level of Evidence B: data were derived from a single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies; 3) Level of Evidence C: data were derived from consensus opinion of experts, case studies, or standards of care. The evidence was rated by four panel experts (J.O. and J.K.; A.K. and L.M.—each rated half the evidence), and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Level C evidence often denoted a circumstance where medical literature addressed the general topic under discussion but it did not address the specific clinical situations or scenarios reviewed by the panel. Since several (but not all) recommendations had multiple components (in most cases multiple medication options), a range is sometimes provided for the level of evidence ; for others, the level of evidence is provided following each recommendation.

ACR Peer Review of Recommendations

Following construction of the recommendations, the manuscript was reviewed through the regular journal review process and by over 30 ACR members serving on the ACR Guidelines Subcommittee, Quality of Care Committee and Board of Directors.

2012 UPDATE OF THE 2008 ACR RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE USE OF DISEASE MODIFYING ANTI-RHEUMATIC DRUGS (DMARDS) AND BIOLOGICS IN PATIENTS WHO QUALIFY FOR TREATMENT OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (RA)

This 2012 ACR recommendations update incorporates the evidence from systematic literature review synthesis and recommendations from 2008 (1) and rating updated and new clinical scenarios regarding the use of DMARDs and biologics for the treatment of RA. Terms used in recommendations are defined in Table 2. The 2012 recommendations are listed in the four sections below and in the following order:

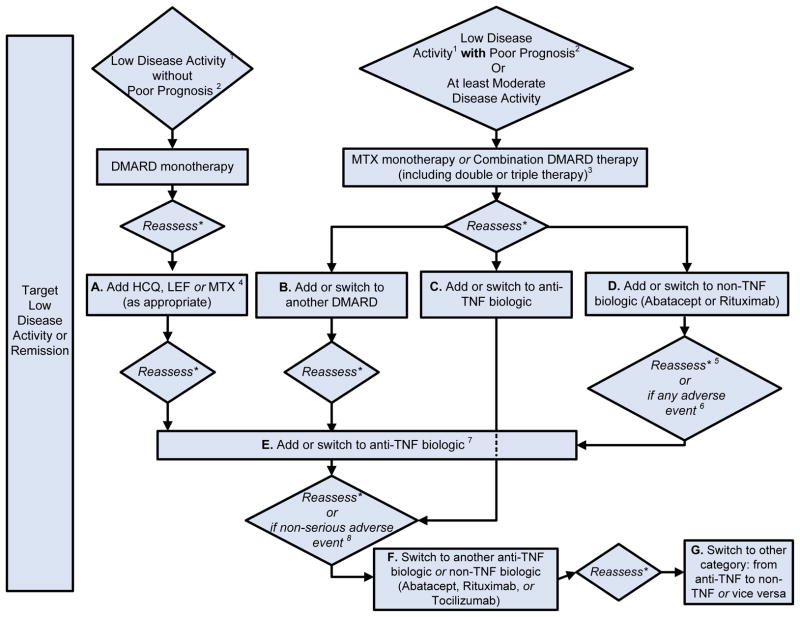

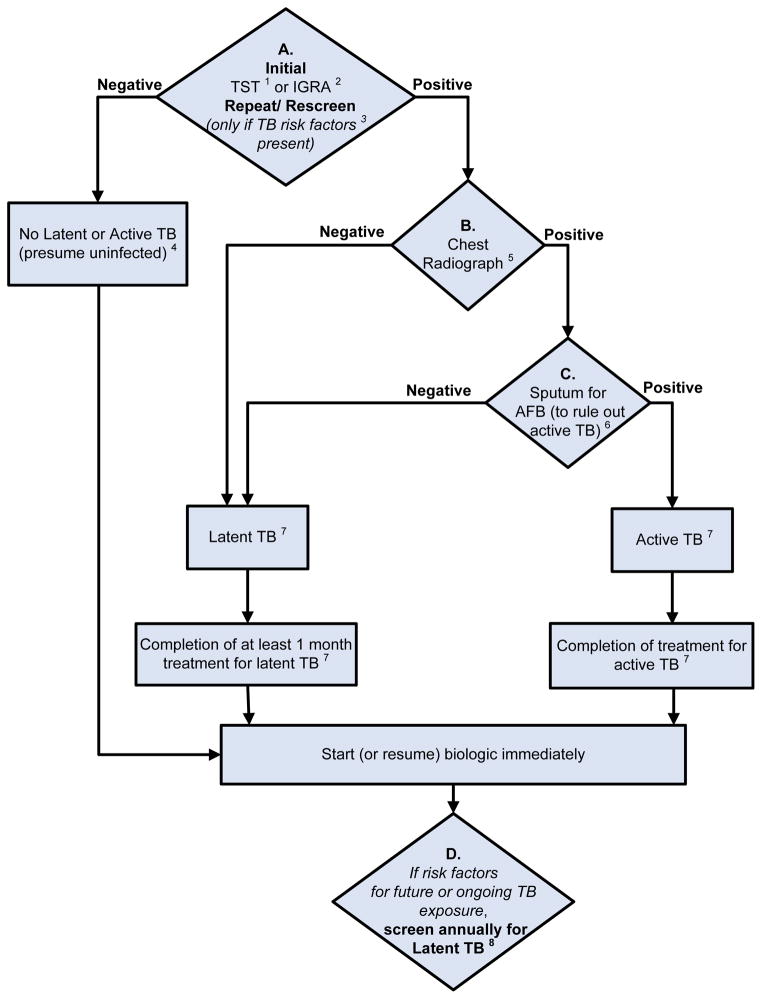

Indications for and switching DMARDs and biologics – early RA (indications, Figure 1) followed by established RA (indications and switching, Figure 2) along with details of the level of evidence supporting these recommendations (Appendix 7)

Use of biologics in patients with hepatitis, malignancy or congestive heart failure who qualify for RA management (Table 4);

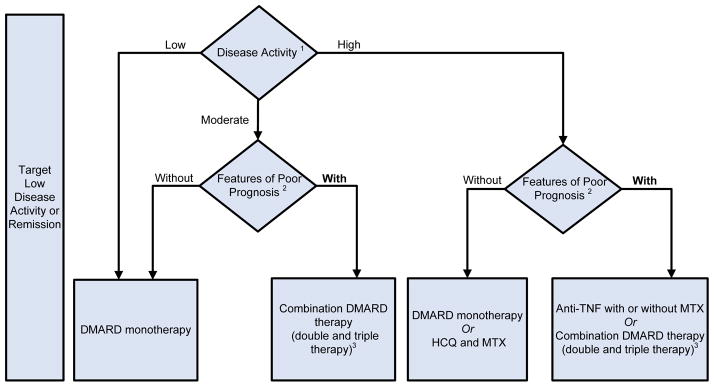

Screening for TB in patients starting or currently receiving biologics as part of their RA therapy (Figure 3); and

Vaccination in patients starting or currently receiving DMARDs or biologics as part of their RA therapy (Table 5).

Figure 1. 2012 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations Update for Treatment of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis, Defined as Disease Duration < 6 Months.

1Definitions of disease activity are discussed in Tables 2 and 3 and Appendix 4 and were categorized as low, moderate or high

2Patients were categorized based on presence or absence of one or more of the following poor prognostic features: functional limitation (e.g., health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) score or similar valid tools); extra-articular disease (e.g., presence of rheumatoid nodules, RA vasculitis, Felty’s syndrome); positive rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies (33–37); bony erosions by radiograph (38)

HCQ, Hydroxychloroquine; MTX, methotrexate; DMARD, Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug- includes hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, minocycline and sulfasalazine; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; TNF, Tumor-necrosis Factor

For the level of evidence supporting each recommendation, please see Appendix 7.

Figure 2. 2012 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations Update for Treatment of Established Rheumatoid Arthritis (Disease Duration≥ 6 months or Meeting 1987 ACR Classification Criteria).

* Reassess after 3 months and proceed escalating therapy if Moderate or High Disease Activity in all instances except after treatment with non-TNF biologic (rectangle D), where reassessment is recommended at 6-months due to a longer anticipated time for peak effect

1Definitions of disease activity are discussed in Tables 2 and 3 and Appendix 4 and were categorized as low, moderate or high

2Features of poor prognosis included the presence of one or more of the following: functional limitation (e.g., health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) score or similar valid tools); extra-articular disease (e.g., presence of rheumatoid nodules, RA vasculitis, Felty’s syndrome); positive rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies (33–37); bony erosions by radiograph (38)

3Combination DMARD therapy with two DMARDs, which is most commonly methotrexate-based with few exceptions (for example, methotrexate + hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate + leflunomide, methotrexate + sulfasalazine, sulfasalazine + hydroxychloroquine) and triple therapy (methotrexate + hydroxychloroquine + sulfasalazine).

4Leflunomide can be added in patients with low disease activity after 3–6 months of minocycline, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate or sulfasalazine

5If after 3 months of intensified DMARD combination-therapy or after a second DMARD has failed, the option is to add or switch to an anti-TNF biologic.

6Reassessment after treatment with non-TNF biologic is recommended at 6-months due to anticipation that a longer time to peak effect is needed for non-TNF compared to anti-TNF biologics.

7Any adverse event was defined as per the U.S. FDA as any undesirable experience associated with the use of a medical product in a patient. Serious adverse events were defined per the U.S. FDA (see below); all other adverse events were considered non-serious adverse events. The FDA definition of serious adverse event includes death, life-threatening event, initial or prolonged hospitalization, disability, congenital anomaly or an adverse event requiring intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage.

For the level of evidence supporting each recommendation, please see Appendix 7.

MTX, methotrexate; LEF, leflunomide; HCQ, Hydroxychloroquine; TNF, Tumor-necrosis factor

DMARD, Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug include hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, minocycline and sulfasalazine (therapies are listed alphabetically; azathioprine and cyclosporine were considered but not included)

DMARD monotherapy refers to treatment in most instances with hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate or sulfasalazine; in few instances, where appropriate, minocycline may also be used

Anti-TNF biologics include adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab

Non-TNF biologics include abatacept, rituximab or tocilizumab (therapies are listed alphabetically)

Table 4.

2012 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations Update for use of Biologics in Patients Otherwise Qualifying for the Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment with a History of Hepatitis, Malignancy, or Congestive Heart Failure

| Comorbidity/Clinical Circumstance | Recommended | Not Recommended | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis | |||

| Hepatitis C | Etanercept | C | |

| Untreated chronic Hepatitis B or with treated chronic Hepatitis B1 with Child-Pugh2 Class B and higher | Any biologic | C | |

| Malignancy | |||

| Treated solid malignancy >5 years ago or treated non-melanoma skin cancer > 5 years ago | Any biologic | C | |

| Treated solid malignancy within the last 5 years or treated non-melanoma skin cancer within the last 5 years3 | Rituximab | C | |

| Treated skin melanoma3 | Rituximab | C | |

| Treated lymphoproliferative malignancy | Rituximab | C | |

| Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) | |||

| NYHA class III/IV4 and with ejection fraction 50% or less. | Anti-TNF biologic | C | |

For definitions and key terms, please refer to Table 2

NYHA, New York Heart Association

Therapy defined as anti-viral regimen deemed appropriate by expert in liver diseases

The Child-Pugh classification liver disease scoring system is based upon the presence of albumin, ascites, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, and encephalopathy. Patients with a score of 10 or more (in the Class C category) have a prognosis with 1-year survival being about 50%. Patients with Class A or B have a better prognosis of 5 years, with a survival rate of 70–80% (12).

little is known about the effects of biologic therapy on solid cancers treated within the past 5 years, due to exclusion of these patients from most randomized controlled trials

NYHA III = Patients with cardiac disease resulting in marked limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary physical activity causes fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or anginal pain. NYHA IV = Patient with cardiac disease resulting in inability to carry out any physical activity without discomfort. Symptoms of cardiac insufficiency or of anginal syndrome may be present even at rest. If any physical activity is undertaken, discomfort is increased (13).

Figure 3. 2012 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations Update for Tuberculosis Screening with Biologic Use.

1Anergy panel testing is not recommended

2IGRA is preferred if patient has a history of Bacillus-Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination

3Risk factors for TB exposure are defined based on a publication from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as: close contacts of persons known or suspected to have active tuberculosis; foreign-born persons from areas that have a high incidence of active tuberculosis (e.g., Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Russia); persons who visit areas with a high prevalence of active tuberculosis, especially if visits are frequent or prolonged; residents and employees of congregate settings whose clients are at increased risk for active tuberculosis (e.g., correctional facilities, long-term care facilities, and homeless shelters); health-care workers who serve clients who are at increased risk for active tuberculosis; populations defined locally as having an increased incidence of latent M. tuberculosis infection or active tuberculosis, possibly including medically underserved, low-income populations, or persons who abuse drugs or alcohol; and infants, children, and adolescents exposed to adults who are at increased risk for latent M. tuberculosis infection or active tuberculosis. (16)

4If patient is immunosuppressed and false negative results more likely, consider repeating screening test(s) with TST or IGRA.

5Chest radiograph may also be considered when clinically indicated in patients with risk factors, even with a negative repeat TST or IGRA.

6Obtain respiratory (e.g., sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage) or other samples as clinically appropriate for AFB smear and culture. Consider referral to TB specialist for further work-up and treatment.

7In a patient diagnosed with latent or active TB, consider referral to a specialist for the recommended treatment.

8Patients who test positive for TST or IGRA at baseline often remain positive for these tests even after successful treatment of TB. These patients need monitoring for clinical signs and symptoms of recurrent TB disease, since repeating tests will not allow help in diagnosis of recurrent TB.

The level of evidence supporting each recommendation for TB reactivation was “C”, except for initiation of biologics in patients being treated for latent TB infection (LTBI), where the Level of Evidence was “B”)

TST, Tuberculin Skin Test; IGRA, Interferon-gamma release assay; AFB, Acid fast bacilli

Table 5.

2012 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations Update Regarding use of Vaccines* in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Starting or Currently Receiving Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs or Biologics

| Killed vaccines | Recombinant vaccine | Live attenuated vaccine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Pneumococcal1 | Influenza (Intramuscular) | Hepatitis B2 | Human Papilloma | Herpes Zoster | |

| Before Initiating Therapy | |||||

| DMARD monotherapy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Combination DMARDs3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Anti-TNF Biologics4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Non-TNF Biologics5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| While already taking therapy | |||||

| DMARD monotherapy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Combination DMARDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Anti-TNF Biologics4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Not recommended6 |

| Non-TNF Biologics5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Not recommended6 |

✓ = Recommend vaccination when indicated (based on age and risk)

Evidence Level was “C” for all the vaccination recommendations

For definitions and key terms, please refer to Table 2

CDC also recommends a one-time pneumococcal revaccination after 5 years for persons with chronic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. For persons aged ≥ 65 years, one-time revaccination is recommended if they were vaccinated ≥5 years previously and were aged < 65 years at the time of primary vaccination.

If hepatitis risk factors are present (e.g., intravenous drug abuse, multiple sex partners in the previous six months, health care personnel).

DMARDs include hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, minocycline and sulfasalazine (listed alphabetically) and combination DMARD therapy included double (most methotrexate-based with few exceptions) or triple therapy (hydroxychloroquine + methotrexate + sulfasalazine)

Anti-TNF biologics include adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab (listed alphabetically)

Non-TNF biologics include abatacept, rituximab and tocilizumab (listed alphabetically)

According to the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method, panel members judged it as “not appropriate” and thus it qualifies as “not recommended” (median score on appropriateness scale was 1)

In the figures, decision-points are shown by diamonds and actions to be taken by the health care provider are shown as rectangles. The recommendations in the text below and in Tables 4 and 5 represent the results of the 2012 update only, whereas Figures 1–3 also incorporate some of the 2008 ACR RA recommendations that did not change (1). Areas of uncertainty by the panel (and which did not lead to recommendations) are noted in Appendix 8.

1. Indications for Starting, Resuming, Adding or Switching DMARDs or Biologics

We first describe the recommendation targeting remission or low disease activity in RA (section 1A). This is followed by recommendations for DMARD or biologic use in early RA (section 1B). Next, we present recommendations for initiating and switching between DMARDs and biologics in established RA (section 1C).

1A. Target Low Disease Activity or Remission

The panel recommends targeting either low disease activity (Table 3) or remission ( Table 2) in all patients with early RA (Figure 1; Level of Evidence C) and established RA (Figure 2; Level of Evidence C) receiving any DMARD or biologic.

1B. Early RA (disease duration < 6 months)

In patients with early RA, the panel recommends the use of DMARD monotherapy both for low disease activity and for moderate or high disease activity with the absence of poor prognostic features (Figure 1; Level of Evidence A–C, details in Appendix 7).

In patients with early RA, the panel recommends the use of DMARD combination-therapy (including double and triple therapy) in patients with moderate or high disease active plus poor prognostic features (Figure 1; Level of Evidence A–C).

In patients with early RA, it also recommends use of an anti-TNF biologic with or without methotrexate in patients who have high disease activity with poor prognostic features (Figure 1; Level of Evidence A–B). Infliximab is the only exception and the recommendation is to use it in combination with methotrexate, but not as monotherapy.

1C. Established RA (disease duration ≥ 6 months or meeting the 1987 ACR RA Classification Criteria)

The remainder of panel recommendations regarding indications for DMARDs and biologics are for patients with established RA. The three sections below define recommendations for initiating and switching therapies in established RA (Figure 2). Where prognosis is not mentioned, the recommendation to use/switch to a DMARD or a biologic applies to all patients, regardless of prognostic features.

Initiating and Switching among DMARDs

If after 3 months of methotrexate or methotrexate/DMARD combination, a patient still has moderate or high disease activity, then add another non-methotrexate DMARD to methotrexate or switch to a different non-methotrexate DMARD (rectangle B of Figure 2; Level of Evidence B–C).

If after 3 months of DMARD monotherapy (in patients without poor prognostic features), a patient deteriorates from low to moderate/high disease activity, then methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine or leflunomide should be added (rectangle A of Figure 2; Level of Evidence A–B).

Switching from DMARDs to Biologics

If a patient has moderate or high disease activity after 3 months of methotrexate monotherapy or DMARD combination-therapy, as an alternative to the DMARD recommendation just noted above, the panels also recommends adding or switching to an anti-TNF biologic, abatacept or rituximab (rectangles C and D of Figure 2; Level of Evidence A–C)

If after 3 months of intensified DMARD combination-therapy or after a second DMARD, a patient still has moderate or high disease activity, add or switch to an anti-TNF biologic (rectangle C of Figure 2; Level of Evidence C).

Switching among Biologics

Due to Lack of Benefit or Loss of Benefit

If a patient still has moderate or high disease activity 3 months of anti-TNF biologic therapy and this is due to lack or loss of benefit, switching to another anti-TNF biologic or a non-TNF biologic is recommended (rectangles F of Figure 2; Level of Evidence B–C).

If a patient still has moderate or high disease activity after 6 months of a non-TNF biologic and whose failure is due to lack or loss of benefit, switch to another non-TNF biologic or an anti-TNF biologic (rectangles H and I of Figure 2; Level of Evidence B–C). An assessment period of 6-months was chosen rather then 3-months, due to the anticipation that longer time may be required for efficacy of non-TNF biologic.

Due to Harms/Adverse Events

If a patient has high disease activity after failing an anti-TNF biologic because of a serious adverse event, switch to a non-TNF biologic (rectangle F of Figure 2; Level of Evidence C).

If a patient has moderate or high disease activity after failing an anti-TNF biologic because of a non-serious adverse event switch to another anti-TNF biologic or a non-TNF biologic (rectangle G of Figure 2; Level of Evidence B–C).

If a patient has moderate or high disease activity after failing a non-TNF biologic because of an adverse event (serious or non-serious), switch to another non-TNF biologic or an anti-TNF biologic (rectangle H of Figure 2; Level of Evidence C).

2. Use of biologics in RA patients with hepatitis, malignancy or congestive heart failure (CHF), qualifying for more aggressive treatment (Level of Evidence “C” for all recommendations)

Hepatitis B or C

The panel recommends that etanercept could potentially be used in RA patients with Hepatitis C requiring RA treatment (Table 4).

The panel also recommends not using biologics in RA patients with untreated chronic Hepatitis B (disease not treated due to contraindications to treatment or intolerable adverse events) and in RA patients with treated chronic Hepatitis B with Child-Pugh Class B and higher (Table 4; for details of Child-Pugh classification, see Table 2) (12). The panel did not make recommendations regarding the use of any biologic for treatment in RA patients with past history of hepatitis B and a positive hepatitis B core antibody.

Malignancies

For patients, who have been treated for solid malignancies more than 5 years ago or who have been treated for non-melanoma skin cancer more than 5 years ago, the panel recommends starting or resuming any biologic if those patients would otherwise qualify for this RA management strategy (Table 4),

They only recommend starting or resuming rituximab in RA patients with: 1) a previously treated solid malignancy within the last 5 years, 2) a previously treated non-melanoma skin cancer within the last 5 years, 3) a previously treated melanoma skin cancer, or 4) a previously treated lymphoproliferative malignancy. Little is known about the effects of biologic therapy in patients with a history of a solid cancer within the past 5 years owing to the exclusion of such patients from participation in clinical trials and the lack of studies examining the risk of recurrent cancer in this subgroup of patients.

Congestive Heart Failure

The panel recommends not using an anti-TNF biologic in RA patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) that is New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV and who have an ejection fraction of 50% or less (Table 4 ) (13).

3. Tuberculosis (TB) Screening for Biologics (Level of Evidence “C” for all recommendations except for initiation of biologics in patients being treated for latent TB infection (LTBI), where the Level of Evidence is “B”)

The panel recommends screening to identify LTBI in all RA patients being considered for therapy with biologics, regardless of the presence of risk factors for LTBI (diamond A of Figure 3) (14). It recommends that clinicians take a history to identify risk factors for TB (specified by the CDC, Table 2).

The panel recommends the Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) or Interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA) as the initial test in all RA patients starting biologics, regardless of risk factors for LTBI (diamond A in Figure 3). It recommends the use of the IGRA over the TST in patients who had previously received a Bacillus-Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination, due to high false-positive test rates for TST (Figure 3).

The panel recommends that RA patients with a positive initial or repeat TST or IGRA should have a chest radiograph and, if positive for past TB exposure or active TB, a subsequent sputum examination to check for the presence of active TB (diamonds B and C in Figure 3). RA patients with a negative screening TST or IGRA may not need further workup in the absence of risk factors and/or clinical suspicion for TB. Since patients with RA may have false-negative TST or IGRA results due to immunosuppression, a negative TST or IGRA should not be interpreted as excluding the possibility that patient has LTBI. Accordingly, in immunosuppressed RA patients with risk factors for LTBI and negative initial screening tests, the panel recommends that a repeat TST or IGRA could be considered 1–3 weeks after the initial negative screening (diamond A in Figure 3).

If the RA patient has active or latent TB based on the test results, the panel recommends appropriate anti-tubercular treatment and consideration of referral to a specialist. Treatment with biologics can be initiated or resumed after 1 month of latent TB treatment with anti-tubercular medications and after completion of the treatment of active TB, as applicable (Figure 3).

The panel recommends annual testing in RA patients who live, travel, or work in situations where TB exposure is likely while they continue treatment with biologics (diamond D of Figure 3). Patients who test positive for TST or IGRA at baseline are expected to remain positive for these tests even after successful treatment of TB. These patients need monitoring for clinical signs and symptoms of recurrent TB, since repeating tests will not help in diagnosis of recurrent TB.

4. Vaccination in patients starting or currently receiving DMARDs or biologics as part of their RA therapy (Level of Evidence “C” for all recommendations)

The panel recommends that all killed (Pneumococcal, Influenza intramuscular and Hepatitis B), recombinant [Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine for cervical cancer] and live attenuated (Herpes Zoster) vaccinations should be undertaken before starting a DMARD or a biologic (Table 5).

It also recommends that, if not previously done, vaccination with indicated Pneumococcal (killed), Influenza intramuscular (killed), Hepatitis B (killed) and HPV vaccine (recombinant) should be undertaken in RA patients already taking a DMARD or a biologic (Table 5).

The panel recommends vaccination with Herpes Zoster vaccine in RA patients already taking a DMARD. All vaccines should be given based on age and risk, and physicians should refer to vaccine instructions and CDC recommendations for details about dosing and timing issues related to vaccinations.

DISCUSSION

We updated the 2008 ACR RA recommendations for the treatment of RA (1) using scientific evidence and a rigorous evidence-based group consensus process. The 2012 update addresses the use of DMARDs and biologics, switching between therapies, use of biologics in high-risk patients, TB screening with the use of biologics, and vaccination in patients with RA receiving DMARDs or biologics.

These recommendations were derived using a rigorous process including a comprehensive updated literature review, data review by a panel of international experts, and use of a well-accepted, validated process for developing recommendations and consensus (2–4).

Because we used the same method for this update as the 2008 ACR RA recommendations, we were able to incorporate the evidence from the 2008 process and comprehensively update the recommendations. Consistent with the common need to extrapolate from clinical experience in the absence of higher tier evidence, many of these new recommendations (approximately 79%) were associated with level C evidence.

These recommendations aim to address common questions facing both patients with RA and the treating health care providers.. Since the recommendations were derived considering the “common patients, not exceptional cases,” they are likely to be applicable to a great majority of RA patients. The emergence of several new therapies for RA in the last decade has led to great excitement in the field of rheumatology as well as provided patients and health care providers with multiple options for treatment.

The 2008 recommendations and 2012 update attempts to simplify the treatment algorithms for patients and providers. These recommendations provide clinicians with choices for treatments of patients with active RA, both in early and established disease phases.

Recommendations also provide guidance regarding treatment choices in RA patients with comorbidities such as hepatitis, CHF and malignancy. In particular, the risk for TB re-activation has become an increasingly common concern for clinicians and patients treating RA patients with biologics. The algorithm recommended provides a comprehensive approach for many RA patients. Due to an increasing awareness of risk of preventable diseases such an influenza and pneumonia (especially in the elderly), immunizations are very important in RA patients. Several recommendations address this important aspect of vaccination of RA patients. Because these recommendations were heavily informed by CDC guidance and minimal additional information was found in the broader literature search, our TB screening and vaccination recommendations are concordant with the CDC recommendations.

The goal for each RA patient should be low disease activity or remission. In ideal circumstances, RA remission should be the target of therapy, but in others, low disease activity may be an acceptable target. However, the decision about what the target should be for each patient is appropriately left to the clinician caring for each RA patient, in the context of patient preferences, comorbidities, and other individual considerations. Therefore, this manuscript does not recommend a specific target for all patients. Of note, the panel recommended more aggressive treatment in patients with early RA than in the 2008 ACR recommendations. We speculate that this may be related to several reasons: 1) the expectation that the earlier the treatment the better the outcome; 2) the thought that joint damage is largely irreversible so prevention of damage is an important goal; and 3) the data that early, intensive therapy may provide the best opportunity to preserve physical function, health-related quality of life and reduce work-related disability (15–22).

As with all recommendations, these recommendations apply to common clinical scenarios and only a clinician’s assessment in collaboration with the patient allows for the best risk/benefit analysis on a case-by-case basis. These recommendations cannot adequately convey all uncertainties and nuances of patient care in the real world. All recommendations were based on scientific evidence coupled with our formal group process rather than only the approved indications from regulatory agencies. Although new classification criteria for RA (ACR-EULAR collaborative initiative) were published in September 2010 (23), the studies evaluated for the 2012 recommendations relied on the use of 1987 ACR RA classification criteria (24) because our literature review preceded the publication of the new criteria.

The need to create recommendations that cover a comprehensive array of relevant clinical decisions has led to many recommendations which combine literature-based data and expert opinion, and thus are labeled as level “C” evidence. For example, rituximab was recommended as appropriate in patients with previously treated solid malignancy within the last 5 years, or a previously treated non-melanoma skin cancer within the last 5 years; a level “C” recommendation since the evidence is based on clinical trial extensions and observational data. It is important to note that the limited evidence available supporting this recommendation comes primarily from non-RA populations that included cancer patients. In addition, the panel ratings did not achieve the level of appropriateness needed to recommend other biologic therapies in this circumstance since most of the panelists’ ratings were “uncertain”. Like many of the other recommendations put forth, this recommendation was grounded, in part, on expert consensus and serves to highlight an important evidence gap in RA management.

In some cases panelists did not make a specific recommendation statement. This occurred when ratings reflected uncertainty over a particular potential clinical scenario or when there was inability to reach consensus. In these cases, given a lack of clear evidence or clear consensus, therapeutic decisions are best left to the careful consideration of risks/benefits by the individual patient and physician. These areas could be the subject of future research agendas and recommendation updates.

We anticipate that in the future, data using the new classification criteria may be available for evidence synthesis and formulating recommendations. Recommendations regarding the use of other anti-inflammatory medications, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and intra-articular and oral corticosteroids, and non-pharmacological therapies, such as physical and occupational therapies, were not within the purview of this update, although these agents may be important components of RA treatment and could also be included in separate reviews or recommendations. For example, recommendations related to glucocorticoid use in RA have been published by other professional organizations (25). The ACR may, in the future, decide to develop broader RA guidelines that include therapies that are not in this manuscript. In addition, due to the infrequent use of gold, anakinra, cyclosporine and azathioprine, scenarios for these medications were not included in this update.

In summary, we provide updated recommendations for the use of non-biologic and biologic treatments in RA following the same methodology used to develop the 2008 ACR RA recommendations. While these recommendations are extensive and include new areas and new agents not covered in 2008, they are not comprehensive. These recommendations, which focus on common clinical scenarios, should be used as a guide for clinicians treating RA patients, with the clear understanding that the best treatment decision can only be made by the clinician in discussions with patients, taking into account their risk/benefit assessment including consideration of comorbidities and concomitant medications, patient preferences, and practical economic considerations. These recommendations are not intended to determine criteria for payment or coverage of health care services. As with this 2012 update, the ACR plans to periodically update RA treatment recommendations depending upon the availability of new therapies, new evidence on the benefits and harms of existing treatments, and changes in policies to reflect the rapidly evolving cutting-edge care of RA patients.

Supplementary Material

Significance and Innovation.

These 2012 recommendations update the 2008 ACR recommendations for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

The recommendations cover the use of Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologics in patients with RA, including switching between drugs.

We address screening for TB reactivation, immunization and treatment of RA patients with hepatitis, congestive heart failure and/or malignancy in these recommendations, given their importance in RA patients receiving or starting biologics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Mary Elkins Melton for administrative support and ACR staff (Ms. Regina Parker and Ms. Amy Miller) for assistance in organizing face-to-face meeting and Ms. Amy Miller for help in revision of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Michael Saag (UAB) for providing expert advice regarding new literature related to clinical scenarios of infection risk, in context of biologics. We thank our two clinical colleagues, Dr. Anthony Turkiewicz and Dr. Gary Feldman for reviewing the recommendations and providing initial comments. We thank Dr. Cheryl Perry of the University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for Clinical and Translational Science (supported by 5UL1 RR025777) for her help in copy-editing this manuscript. We thank Dr. Ruiz Garcia of Médico adjunto de la Unidad de Hospitalización a Domicilio, Spain for providing data from their Cochrane systematic review on certolizumab in RA.

Grant support: This material is the result of work supported with a research grant from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).

Addendum

Therapies that were approved after the original literature review are not included in these recommendations.

Footnotes

participated in meetings only prior to june 2010

Task Force Panel

Claire Bombardier MD MSc (University of Toronto), Arthur F. Kavanaugh MD (University of California, San Diego), Dinesh Khanna MD MSc (University of Michigan), Joel M. Kremer MD (Albany Medical Center), Amye L. Leong MBA (Healthy Motivation), Eric L. Matteson MD MPH (Mayo Clinic, Rochester), John T. Schousboe MD PhD (Park Nicollet Clinic and University of Minnesota), Charles King (North Mississippi Medical Center, Tupelo, MS), Maxime Dougados, MD (Hopital Cochin, Paris, France), Eileen Moynihan, MD (Woodbury, New Jersey), Karen S. Kolba, MD (Pacific Arthritis Center Santa Mara, CA)

Core Expert Panel

Timothy Beukelman MD MSCE (University of Alabama), S. Louis Bridges MD PhD (University of Alabama), W Winn Chatham MD (University of Alabama), Jeffrey R. Curtis MD MPH (University of Alabama), Daniel E. Furst MD (UCLA), Ted Mikuls* (University of Nebraska), Larry Moreland MD (University of Pittsburgh), James O’Dell MD (University of Nebraska), Harold Paulus MD (UCLA), Kenneth G. Saag MD MSc (University of Alabama), Jasvinder A. Singh MBBS MPH (University of Alabama), Maria Suarez-Almazor MD MPH (MD Anderson)

Content Specific Expert Advisors

Tuberculosis: Kevin L. Winthrop MD, MPH (Oregon Health and Science University)

Infections: Michael Saag MD (University of Alabama at Birmingham)

Financial Conflict: Forms submitted as required

This study did not involve human subjects and therefore approval from Human Studies Committees was not required.

“The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.”

References

- 1.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. Epub 2008/06/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGory ML, Shekelle PG, Rubenstein LZ, Fink A, Ko CY. Developing quality indicators for elderly patients undergoing abdominal operations. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):870–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.07.009. Epub 2005/11/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shekelle P. The appropriateness method. Med Decis Making. 2004;24(2):228–31. doi: 10.1177/0272989X04264212. Epub 2004/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shekelle PG, Park RE, Kahan JP, Leape LL, Kamberg CJ, Bernstein SJ. Sensitivity and specificity of the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method to identify the overuse and underuse of coronary revascularization and hysterectomy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1004–10. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00365-1. Epub 2001/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, Singh G. Golimumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD008341. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008341. Epub 2010/01/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh JA, Beg S, Lopez-Olivo MA. Tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD008331. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008331.pub2. Epub 2010/07/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh JA, Christensen R, Wells GA, Suarez-Almazor ME, Buchbinder R, Lopez-Olivo MA, et al. Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD007848. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007848.pub2. Epub 2009/10/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz Garcia V, Burls A, Cabello López JC, Fry- Smith AF, Gálvez Muñoz JG, Jobanputra P, et al. Certolizumab pegol (CDP870) for rheumatoid arthritis in adults (Protocol) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(1 ):CD007649. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007649.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FDA. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. What is a Serious Adverse Event? Rockville, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; [Accessed 02/14/2011]. 2010. http://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/howtoreport/ucm053087.htm. Page last udpated 12/15/2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112(12):e154–235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen E, Schlichting P, Fauerholdt L, Gluud C, Andersen PK, Juhl E, et al. Prognostic value of Child-Turcotte criteria in medically treated cirrhosis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md. 1984;4(3):430–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurst JW, Morris DC, Alexander RW. The use of the New York Heart Association’s classification of cardiovascular disease as part of the patient’s complete Problem List. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(6):385–90. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960220604. Epub 1999/06/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. MMWR. 2000;49(RR-6) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bejarano V, Quinn M, Conaghan PG, Reece R, Keenan AM, Walker D, et al. Effect of the early use of the anti-tumor necrosis factor adalimumab on the prevention of job loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1467–74. doi: 10.1002/art.24106. Epub 2008/09/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):375–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61000-4. Epub 2008/07/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han C, Smolen J, Kavanaugh A, St Clair EW, Baker D, Bala M. Comparison of employability outcomes among patients with early or long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(4):510–4. doi: 10.1002/art.23541. Epub 2008/04/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimel M, Cifaldi M, Chen N, Revicki D. Adalimumab plus methotrexate improved SF-36 scores and reduced the effect of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on work activity for patients with early RA. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(2):206–15. Epub 2007/12/19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde D, Emery P, Bathon JM, Keystone E, et al. Infliximab treatment maintains employability in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):716–22. doi: 10.1002/art.21661. Epub 2006/03/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, Maini RN, Bathon JM, Emery P, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3432–43. doi: 10.1002/art.20568. Epub 2004/11/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Kooij SM, le Cessie S, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, et al. Clinical and radiological efficacy of initial vs delayed treatment with infliximab plus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1153–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.093294. Epub 2008/10/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. The New England journal of medicine [Internet] 2000;(22):1586–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201. Available from: http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clcentral/articles/393/CN-00331393/frame.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2569–81. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. Epub 2010/09/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. Epub 1988/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):964–75. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126532. Epub 2010/05/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aletaha D, Smolen JS. The definition and measurement of disease modification in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2006;32(1):9–44. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aletaha D, Ward MM, Machold KP, Nell VP, Stamm T, Smolen JS. Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2005;52(9):2625–36. doi: 10.1002/art.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1995;38(6):727–35. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pincus T. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Core Data Set and derivative “patient only” indices to assess rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells GA, Boers M, Shea B, Brooks PM, Simon LS, Strand CV, et al. Minimal disease activity for rheumatoid arthritis: a preliminary definition. The Journal of rheumatology. 2005;32(10):2016–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T. A composite disease activity scale for clinical practice, observational studies, and clinical trials: the patient activity scale (PAS/PAS-II) The Journal of rheumatology. 2005;32(12):2410–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T, Furst D, Keystone E. The disease activity score is not suitable as the sole criterion for initiation and evaluation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in the clinic: discordance between assessment measures and limitations in questionnaire use for regulatory purposes. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2005;52(12):3873–9. doi: 10.1002/art.21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agrawal S, Misra R, Aggarwal A. Autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: association with severity of disease in established RA. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(2):201–4. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ates A, Kinikli G, Turgay M, Akay G, Tokgoz G. Effects of rheumatoid factor isotypes on disease activity and severity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparative study. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(4):538–45. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berglin E, Johansson T, Sundin U, Jidell E, Wadell G, Hallmans G, et al. Radiological outcome in rheumatoid arthritis is predicted by presence of antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide before and at disease onset, and by IgA-RF at disease onset. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2006;65(4):453–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.041376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer O, Labarre C, Dougados M, Goupille P, Cantagrel A, Dubois A, et al. Anticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody assays in early rheumatoid arthritis for predicting five year radiographic damage. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2003;62(2):120–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.2.120. Epub 2003/01/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vencovsky J, Machacek S, Sedova L, Kafkova J, Gatterova J, Pesakova V, et al. Autoantibodies can be prognostic markers of an erosive disease in early rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2003;62(5):427–30. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.5.427. Epub 2003/04/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brook A, Corbett M. Radiographic changes in early rheumatoid disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1977;36(1):71–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.36.1.71. Epub 1977/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells G, Becker JC, Teng J, Dougados M, Schiff M, Smolen J, et al. Validation of the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):954–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084459. Epub 2008/05/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bresnihan B. Preventing joint damage as the best measure of biologic drug therapy. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2002;65:39–43. Epub 2002/09/19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LH, Funovits J, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):573–86. doi: 10.1002/art.30129. Epub 2011/02/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pincus T, Yazici Y, Bergman M. A practical guide to scoring a Multi-Dimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ) and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID) scores in 10–20 seconds for use in standard clinical care, without rulers, calculators, websites or computers. Best practice & research. 2007;21(4):755–87. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, Uffmann M, Pflugbeil S, Machold K, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(4):R796–806. doi: 10.1186/ar1740. Epub 2005/07/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fransen J, Stucki G, Van Riel PL. Disease Activity Score (DAS), Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS28), Rapid Assessment of Disease Activity in Rheumatology (Radar), and Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI) Arthritis and rheumatism. 2003;49(5S):S214–S24. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, Kalden JR, Emery P, Eberl G, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42(2):244–57. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg072. Epub 2003/02/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.