Abstract

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In developed countries, ALD is a major cause of end-stage liver disease that requires transplantation. The spectrum of ALD includes simple steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Alcohol abstinence is the most effective therapy for ALD. However, targeted therapies are urgently needed for patients with severe ALD (i.e., alcoholic hepatitis) or those who do not abstain from alcohol. The lack of studies and the availability of animal models that do not reflect all the features of this disease in humans inhibit the development of new drugs for ALD. In ALD-associated fibrosis, hepatic stellate cells are the principal cell type responsible for extracellular matrix production. Although the mechanisms underlying fibrosis in ALD are largely similar to those observed in other chronic liver diseases, oxidative stress, methionine metabolism abnormalities, hepatocyte apoptosis, and endotoxin lipopolysaccharides that activate Kupffer cells may play unique roles in disease-related fibrogenesis. Lipogenesis during the early stages of ALD has recently been implicated as a risk factor for the progression of cirrhosis. Other topics include osteopontin, interleukin-1 signaling, and genetic polymorphism. In this review, we discuss the basic pathogenesis of ALD and focus on liver fibrogenesis.

Keywords: Stellate cell, Kupffer cell, Steatohepatitis, Fibrosis, Cytokine, Oxidative stress

Core tip: Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a major cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In ALD-associated fibrosis, hepatic stellate cells are the principal cell type responsible for extracellular matrix production. Although the mechanisms underlying ALD-associated fibrosis are largely similar to those observed in other chronic liver diseases, oxidative stress, abnormal methionine metabolism, hepatocyte apoptosis, and endotoxin lipopolysaccharides that activate Kupffer cells play unique roles in fibrogenesis in ALD. Recently, lipogenesis during the early stages of ALD has been implicated as a risk factor for progression of cirrhosis. Other critical factors include osteopontin, interleukin-1 signaling, and genetic polymorphisms.

INTRODUCTION

Although the incidence of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) varies widely worldwide, the burden of ALD and ALD-induced death remains dominant in most countries[1]. ALD is the third highest risk factor for disease and disability worldwide. Almost 4% of all deaths in the world result from ALD, which is greater than deaths caused by the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, violence, or tuberculosis[1]. Furthermore, alcohol is associated with many serious social problems, including violence, child neglect, and abuse, and absenteeism in the workplace. A recent nationwide survey revealed that ALD was the third highest cause of liver cirrhosis in Japan (13.6%)[2], and the associated cost of medical care was estimated to be 6.9% of the total national medical expenditure[3]. Overall, ALD is recognized as a major but preventable public health problem.

The spectrum of ALD is broad: asymptomatic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, progressive fibrosis, end-stage cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[4,5]. ALD may often resolve in those who become abstinent. However, for patients with severe ALD and those who do not completely abstain from alcohol, targeted therapies are urgently needed[4].

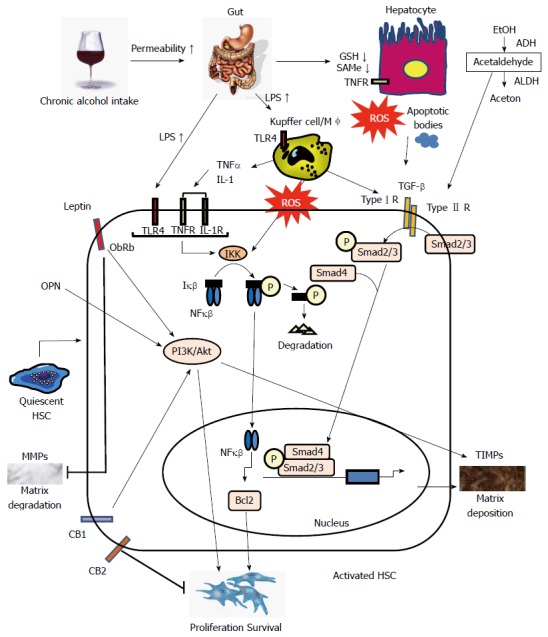

Patients with ALD can develop progressive liver fibrosis because of the accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) materials, including type I collagen, as generated by activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and hepatic myofibroblasts. When liver injury occurs, HSCs are activated and differentiate into myofibroblast-like cells[6,7]. Activated Kupffer cells, infiltrating monocytes, activated and aggregated platelets, and damaged hepatocytes are the sources of platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1); these cells initiate intracellular signaling cascades leading to HSC activation. Although the key pathways of HSC activation are common to all forms of liver injury and fibrosis, disease-specific pathways also exist. Some specific signaling pathways regulating HSC activation in ALD are discussed below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Signaling pathways regulating hepatic stellate cell activation in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol consumption causes hepatocyte damage, which subsequently induces apoptosis. Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) oxidizes alcohol to acetaldehyde that is converted to acetate by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). Acetaldehyde directly targets hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Alcohol reduces glutathione (GSH) synthesis and acetaldehyde inhibits GSH activity in hepatocytes. Levels of the S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) are also markedly reduced. Alcohol consumption increases permeability of the intestine to bacterial endotoxin that in turn, elevates serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels. LPS directly enhances HSCs activation by upregulating transforming growth factor (TGF)- signaling. TGF-β1 derived from activated Kupffer cells and damaged hepatocytes binds to TGF receptors. Phospho-Smad2/3 and Smad4 complexes translocate into the nucleus, display DNA-binding activity, and activate expression of genes related to fibrosis. Extracellular molecules, such as LPS, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), activate IκB kinase (IKK) that, in turn, phosphorylates IκB, resulting in ubiquitination, dissociation of IκBα from nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and eventually, degradation of IκB by the proteasome. The activated NF-κB is then translocated into the nucleus and binds to specific DNA response elements. NF-B-dependent pathways are involved in the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2). Leptin binds ObRb, activating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway and inducing matrix deposition by increasing expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). Leptin also inhibits matrix degradation by decreasing expression of Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Osteopontin (OPN) positively stimulates the PI3K/Akt pathway. The cannabinoid receptor CB2 mediates antifibrotic actions; in contrast, activation of CB1 receptors positively stimulates the PI3K/Akt pathway to promote the proliferation and apoptosis of HSCs. TLR: Toll-like receptor.

CLASSICAL MECHANISMS UNDERLYING FIBROGENESIS IN ALD

Alcohol metabolism

Approximately 90% of ingested alcohol is metabolized in the cytosol of hepatocytes. Cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase[8] oxidizes alcohol to acetaldehyde that is then converted to acetate by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetaldehyde is considered the key toxin in alcohol-mediated liver injury that includes cellular damage, inflammation, ECM remodeling, and fibrogenesis[9]. Moreover, acetaldehyde triggers TGF-β1-dependent late-phase response in HSCs that maintains a pro-fibrogenic and pro-inflammatory cellular state[10]. Recently, Liu et al[10] indicated that, in vitro, leptin potentiates acetaldehyde-induced HSC activation and alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA) expression by interleukin-6 (IL-6)-dependent signals such as p38 and phosphorylated-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1⁄2. This report discusses the importance of a synergistic effect of leptin and acetaldehyde in the activation of HSCs in ALD.

Oxidative stress

Alcohol consumed in chronic and heavy drinkers is also oxidized via the hepatocytic cytochrome P450 (CYP); previously termed inducible microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system[11]. CYP2E1 metabolizes various substances, including multiple drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, acetaminophen, and most organic solvents, and plays a critical role in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anions[11,12]. ROS are also generated from nitric oxide and reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase by Kupffer cells[13]. ROS trigger inflammatory cascades and recruit neutrophils and other immune cells to the site of alcohol-induced hepatocyte damage, increasing levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, notably tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α[14].

Accumulation of lipid peroxidation products, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), has been reported both in patients as well as animal models of ALD[15,16]. Several studies have shown that the lipid peroxidation reaction in the liver precedes the initial stages of fibrosis and is associated with the increased production of pro-fibrogenic TGF-β1 by Kupffer cells[14]. Nieto reported that ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation triggers the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) transactivation of the collagen 2(I) gene promoter in HSCs by stimulating kinase cascades, including protein kinase C, phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K), and protein kinase B/Akt[17]. These observations are agreement with the findings of previous reports, indicating that 4-HNE is pro-fibrogenic for collagen production in human HSCs[14] and that oxidative stress directly promotes collagen synthesis in HSCs over-expressing the CYP2E1 gene[14].

Methionine metabolism

Decreased intracellular levels of antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, and glutathione (GSH) in the blood and liver modify the process of alcohol-induced liver injury[18]. Excessive acute alcohol intake reduces GSH synthesis, and the acetaldehyde produced from alcohol metabolism inhibits GSH activity. Alcohol also disturbs the intracellular transport of GSH and preferentially depletes mitochondrial GSH, leading to apoptosis[18]. Levels of S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), a universal methyl donor, are also markedly reduced in ALD due to the reduced activity of SAMe synthetase[18]. This fact is clinically important because therapy using SAMe increases survival of patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis[18].

Hepatocyte apoptosis

Hepatocyte apoptosis is pathophysiologically important in the progression of ALD[19]. There are two important apoptotic pathways: extrinsic (death receptor-mediated) and intrinsic (organelle-initiated)[20]. Most recently, Petrasek et al[21] revealed that interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) mediates ALD by linking endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress with the mitochondrial pathway of hepatocyte apoptosis. Interestingly, ethanol induces ER stress and triggers the association of IRF-3 with the ER adaptor, stimulator of interferon genes, as well as the subsequent phosphorylation of IRF-3. Activated IRF-3 is associated with the proapoptotic molecule Bax (B-cell lymphoma 2-associated X protein) and contributes to hepatocyte apoptosis[21]. Apoptotic bodies induced by alcohol are phagocytosed by Kupffer cells and HSCs, which then produce TGF-β1 and subsequently activate HSCs[19,22]. Finally, increased serum levels of caspase-digested cytokeratin-18 fragments, a useful marker of hepatocyte apoptosis, are independent factors in predicting severe fibrosis in patients with ALD[23].

Lipopolysaccharide

Increased serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels are commonly found in patients with ALD[19]. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 is one of the multiple pattern recognition receptors that recognize both pathogen- and host-derived factors that modulate inflammatory signals[24]. LPS interacts with TLR4 to activate the MyD88-independent toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β/IRF-3 signaling pathway that produces oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokines (including TNF-α) causes hepatocellular damage and contributes to alcoholic steatohepatitis[15,22,25]. Recent studies have revealed that activation of TLR4 and complement factors also stimulates Kupffer cells to produce hepatoprotective cytokines, such as IL-6, and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10[15,22,25,26]. These cytokines activate signal transduction and activator of transcription 3 in hepatocytes and macrophages/Kupffer cells, respectively, to prevent alcohol-induced liver injury and inflammation[15,22,26]. On the other hand, previous studies have reported that activation of TLR4 signaling in HSCs and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) promoted liver fibrogenesis[22,25], and that activation of TLR4 signaling in LSECs regulates angiogenesis through the MyD88-effector protein that regulates extracellular protease production, in turn, results in the development of liver fibrosis[27].

Experimental models of ALD have revealed that translocation of bacterial products across the intestinal barrier to the portal circulation triggers inflammatory responses in the liver and contributes to steatohepatitis[28,29]. Most recently, Hartmann et al[30] investigated the role of the intestinal mucus layer and found that mucin (Muc) 2 was involved in the development of alcohol-associated liver disease. The authors reported that Muc2-/- mice have significantly lower plasma levels of LPS than wild-type mice after alcohol administration. In addition, it was shown that Muc2-/- mice are effectively protected from intestinal bacterial overgrowth and the microbiome in response to alcohol administration[30]. This study clearly showed that the alcohol-associated alteration in the microbiome, and in particular, the overgrowth of intestinal bacteria contributes to the progression of ALD.

EMERGING MECHANISMS UNDERLYING FIBROGENESIS IN ALD

Lipogenesis in the early stages of ALD

The development of steatosis due to chronic alcohol consumption is an important contributor to the progression of hepatic fibrogenesis[15]. Recent studies have found that direct or indirect alcohol exposure regulates transcription factors associated with lipid metabolism. Alcohol also stimulates lipogenesis and inhibits fatty acid oxidation[31]. There are two well-known pathways of lipogenesis: sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-1 activation and adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK) inhibition[15,31].

Alcohol consumption directly upregulates SREBP-1c gene expression through its metabolite acetaldehyde[19] or indirectly upregulates activating processes and factors such as ER stress[32], adenosine[33,34], endocannabinoids[35], LPS signaling via TLR4, and its downstream proteins, such as IRF-3, early growth response-1, and TNF-α.

AMPK is a key player in cellular and organism survival in metabolic stress through its ability to maintain metabolic homeostasis[36]. Chronic ethanol exposure inhibits AMPK activity, which increases activity of acetyl-CoA carboxylase and suppresses the rate of palmitic acid oxidation through the inhibition of liver kinase B1 phosphorylation[31,36].

The endocannabinoids, which are similar to the major active ingredient in marijuana, are endogenous lipid mediators that participate in the complex neural circuitry that controls energy intake[37]. There are at least two different cannabinoid receptors: CB1 and CB2. Recent studies indicate that while CB2 receptors mediate antifibrotic actions, the activation of CB1 receptors contribute to the development of fibrosis[37,38]. Both cannabinoid receptors are expressed in HSCs, and the inactivation of CB1 receptors decrease fibrogenesis by lowering TGF-β1 levels and reduce the accumulation of fibrogenic cells via downregulation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway[37]. Intriguingly, alcoholic liver steatosis is mediated mainly through HSC-derived endocannabinoids and their hepatocytic receptor[22,37]. Chronic alcohol consumption stimulates HSCs to produce 2-arachidonoylglycerol and its interaction with the CB1 receptor upregulates the expression of SREPB1c and fatty acid synthase, but downregulates the activities of AMPK and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1[37,39].

Osteopontin

Osteopontin (OPN) is a secreted, 44-66 kDa adhesive glycophosphoprotein that has involvement in both normal processes, such as bone development and immune system regulation, and pathologic processes, such as inflammation, cell transformation, tumor invasiveness, and metastasis[40]. OPN plays additional roles in ALD. In animal models, hepatic mRNA levels of OPN increased in ALD[15] and stimulated HSC activation in an autocrine and paracrine fashion[41]. Recently, Urtasun et al[42] investigated the mechanism of OPN in HSC activation. Recombinant OPN upregulated type I collagen production in primary HSCs in a TGF-β independent fashion, whereas it down-regulated matrix metalloprotease (MMP)-13. OPN induction of type I collagen occurred via integrin avβ3 engagement and activation of the PI3K/pAkt/NF-κB-signaling pathway[42]. On the other hand, recent studies indicate that OPN participates in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and the fibrosis that results from non-alcoholic steatohepatitis[43]. OPN regulates steatohepatitis by stimulating the Hedgehog-signaling pathway[43]. In human ALD, hepatic mRNA levels of OPN correlate with hepatic neutrophil infiltration and the severity of fibrosis[44]. Finally, immunohistochemical detection of OPN is used as a prognostic biomarker to discriminate outcomes in some transplant patients with hepatocellular carcinoma derived from ALD[45].

IL-1 signaling

Emerging data have provided evidence for the role of IL-1 signaling in acute and chronic liver injury resulting from various causes, including acetaminophen-induced liver damage[46], nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[47], liver fibrosis[48], and immune-mediated liver injury[49]. However, the significance of IL-1 signaling in ALD has yet to be evaluated. A recent study from Petrasek et al[50] showed that activation of inflammasome-IL-1 signaling also plays a critical role in ethanol-induced liver injury in mice. Using IL-1 receptor antagonist-treated mice as well as 3 different mouse models deficient in regulators of IL-1β activation [caspase-1 (Casp-1) and ASC] or signaling (IL-1 receptor), they showed that IL-1β signaling is required for the development of alcohol-induced liver steatosis, inflammation, and injury. Interestingly, several fibrotic markers such as procollagen III N-terminal propeptide (PIIINP), tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1), and hyaluronic acid were downregulated in ethanol-fed Casp-1 knockout mice or in response to IL-1Ra treatment. Although the roles of inflammasome in HSC activation are not fully elucidated[51], it is suggested that targeting the inflammasome and/or IL-1 signaling pathways have therapeutic potential in ALD management. However, further studies are required to discover direct evidence of the relationship between IL-1 signaling and fibrogenesis in ALD.

Genetic variants associated with the fibrosis of ALD

With the genotyping technique becoming more widely available, a great number of genetic case-control studies have evaluated candidate gene-variants that code proteins involved in the hepatic fibrosis[52]. Although two fibrosis-associated genes, including TGF-β and MMP 3, were evaluated in ALD[52], these genotypes are not associated with alcoholic liver cirrhosis[53,54]. Recent whole genome analyses of large numbers of genetic variants have identified novel yet unconsidered candidate genes[55]. Romeo et al[56] reported that the single-nucleotide polymorphism [rs738409(G), encoding I148M] in the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing (PNPLA) 3 gene is a significant risk factor for increased hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Subsequently, the strong association between the PNPLA3 I148 M allele and an increased risk of clinically evident alcoholic cirrhosis and liver cancer were confirmed in individual studies[57-60]. Most recently, Burza et al[61] reported that an increased age at onset of at-risk alcohol consumption and the PNPLA3 I148 M allele were independent risk factors for alcoholic liver cirrhosis (HR = 2.76; P < 0.01 vs 1.53; P = 0.021).

CONCLUSION

In this review, several aspects potentially contributing to the mechanisms underlying fibrogenesis in ALD are discussed. Since there are no FDA-approved treatments for ALD at present, development of novel therapies for inhibiting inflammation and/or fibrogenesis associated with early stages of ALD will be beneficial for slowing disease progression and improving patient outcomes[51]. To achieve these objectives, animal models that accurately reflect the metabolic and histological characteristics of human ALD are needed.

Footnotes

Supported by A grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through grant No. 25293177 to Kawada N (2013-2016), and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the JSPS through grant No. 25461007 to Fujii H (2013-2016)

P- Reviewers: Dragoteanu M, He ST, Streba CT, Zhang SJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Schwartz JM, Reinus JF. Prevalence and natural history of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michitaka K, Nishiguchi S, Aoyagi Y, Hiasa Y, Tokumoto Y, Onji M. Etiology of liver cirrhosis in Japan: a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura K, Tanaka A, Takano T. The social cost of alcohol abuse in Japan. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54:618–625. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altamirano J, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new targets for therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:491–501. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford JM. Histologic findings in alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:699–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawada N. Evolution of hepatic fibrosis research. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:199–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elamin EE, Masclee AA, Dekker J, Jonkers DM. Ethanol metabolism and its effects on the intestinal epithelial barrier. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:483–499. doi: 10.1111/nure.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mello T, Ceni E, Surrenti C, Galli A. Alcohol induced hepatic fibrosis: role of acetaldehyde. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Brymora J, Zhang H, Smith B, Ramezani-Moghadam M, George J, Wang J. Leptin and acetaldehyde synergistically promotes αSMA expression in hepatic stellate cells by an interleukin 6-dependent mechanism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:921–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung TM, Nieto N. CYP2E1 and oxidant stress in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:395–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu H, Jia Z, Misra H, Li YR. Oxidative stress and redox signaling mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease: updated experimental and clinical evidence. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dey A, Cederbaum AI. Alcohol and oxidative liver injury. Hepatology. 2006;43:S63–S74. doi: 10.1002/hep.20957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albano E. Oxidative mechanisms in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seth D, Haber PS, Syn WK, Diehl AM, Day CP. Pathogenesis of alcohol-induced liver disease: classical concepts and recent advances. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1089–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smathers RL, Galligan JJ, Stewart BJ, Petersen DR. Overview of lipid peroxidation products and hepatic protein modification in alcoholic liver disease. Chem Biol Interact. 2011;192:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nieto N. Ethanol and fish oil induce NFkappaB transactivation of the collagen alpha2(I) promoter through lipid peroxidation-driven activation of the PKC-PI3K-Akt pathway. Hepatology. 2007;45:1433–1445. doi: 10.1002/hep.21659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kharbanda KK. Methionine metabolic pathway in alcoholic liver injury. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:89–95. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32835a892a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alkhouri N, Carter-Kent C, Feldstein AE. Apoptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5:201–212. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrasek J, Iracheta-Vellve A, Csak T, Satishchandran A, Kodys K, Kurt-Jones EA, Fitzgerald KA, Szabo G. STING-IRF3 pathway links endoplasmic reticulum stress with hepatocyte apoptosis in early alcoholic liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16544–16549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308331110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suh YG, Jeong WI. Hepatic stellate cells and innate immunity in alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2543–2551. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i20.2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavallard VJ, Bonnafous S, Patouraux S, Saint-Paul MC, Rousseau D, Anty R, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tran A, Gual P. Serum markers of hepatocyte death and apoptosis are non invasive biomarkers of severe fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrasek J, Csak T, Szabo G. Toll-like receptors in liver disease. Adv Clin Chem. 2013;59:155–201. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-405211-6.00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao B, Seki E, Brenner DA, Friedman S, Cohen JI, Nagy L, Szabo G, Zakhari S. Innate immunity in alcoholic liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G516–G525. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00537.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrasek J, Dolganiuc A, Csak T, Nath B, Hritz I, Kodys K, Catalano D, Kurt-Jones E, Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Interferon regulatory factor 3 and type I interferons are protective in alcoholic liver injury in mice by way of crosstalk of parenchymal and myeloid cells. Hepatology. 2011;53:649–660. doi: 10.1002/hep.24059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagavelu K, Routray C, Shergill U, O’Hara SP, Faubion W, Shah VH. Endothelial cell toll-like receptor 4 regulates fibrosis-associated angiogenesis in the liver. Hepatology. 2010;52:590–601. doi: 10.1002/hep.23739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan AW, Fouts DE, Brandl J, Stärkel P, Torralba M, Schott E, Tsukamoto H, Nelson KE, Brenner DA, Schnabl B. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:96–105. doi: 10.1002/hep.24018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:638–644. doi: 10.1002/hep.23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartmann P, Chen P, Wang HJ, Wang L, McCole DF, Brandl K, Stärkel P, Belzer C, Hellerbrand C, Tsukamoto H, et al. Deficiency of intestinal mucin-2 ameliorates experimental alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:108–119. doi: 10.1002/hep.26321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breitkopf K, Nagy LE, Beier JI, Mueller S, Weng H, Dooley S. Current experimental perspectives on the clinical progression of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1647–1655. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esfandiari F, Medici V, Wong DH, Jose S, Dolatshahi M, Quinlivan E, Dayal S, Lentz SR, Tsukamoto H, Zhang YH, et al. Epigenetic regulation of hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways in the ethanol-fed cystathionine beta synthase-deficient mouse. Hepatology. 2010;51:932–941. doi: 10.1002/hep.23382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng Z, Borea PA, Varani K, Wilder T, Yee H, Chiriboga L, Blackburn MR, Azzena G, Resta G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine signaling contributes to ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:582–594. doi: 10.1172/JCI37409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robson SC, Schuppan D. Adenosine: tipping the balance towards hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:941–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trebicka J, Racz I, Siegmund SV, Cara E, Granzow M, Schierwagen R, Klein S, Wojtalla A, Hennenberg M, Huss S, et al. Role of cannabinoid receptors in alcoholic hepatic injury: steatosis and fibrogenesis are increased in CB2 receptor-deficient mice and decreased in CB1 receptor knockouts. Liver Int. 2011;31:860–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sid B, Verrax J, Calderon PB. Role of AMPK activation in oxidative cell damage: Implications for alcohol-induced liver disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tam J, Liu J, Mukhopadhyay B, Cinar R, Godlewski G, Kunos G. Endocannabinoids in liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:346–355. doi: 10.1002/hep.24077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallat A, Teixeira-Clerc F, Deveaux V, Manin S, Lotersztajn S. The endocannabinoid system as a key mediator during liver diseases: new insights and therapeutic openings. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1432–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeong WI, Osei-Hyiaman D, Park O, Liu J, Bátkai S, Mukhopadhyay P, Horiguchi N, Harvey-White J, Marsicano G, Lutz B, et al. Paracrine activation of hepatic CB1 receptors by stellate cell-derived endocannabinoids mediates alcoholic fatty liver. Cell Metab. 2008;7:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagoshi S. Osteopontin: Versatile modulator of liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:22–30. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seth D, D’Souza El-Guindy NB, Apte M, Mari M, Dooley S, Neuman M, Haber PS, Kundu GC, Darwanto A, de Villiers WJ, et al. Alcohol, signaling, and ECM turnover. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:4–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urtasun R, Lopategi A, George J, Leung TM, Lu Y, Wang X, Ge X, Fiel MI, Nieto N. Osteopontin, an oxidant stress sensitive cytokine, up-regulates collagen-I via integrin α(V)β(3) engagement and PI3K/pAkt/NFκB signaling. Hepatology. 2012;55:594–608. doi: 10.1002/hep.24701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Syn WK, Choi SS, Liaskou E, Karaca GF, Agboola KM, Oo YH, Mi Z, Pereira TA, Zdanowicz M, Malladi P, et al. Osteopontin is induced by hedgehog pathway activation and promotes fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;53:106–115. doi: 10.1002/hep.23998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patouraux S, Bonnafous S, Voican CS, Anty R, Saint-Paul MC, Rosenthal-Allieri MA, Agostini H, Njike M, Barri-Ova N, Naveau S, et al. The osteopontin level in liver, adipose tissue and serum is correlated with fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sieghart W, Wang X, Schmid K, Pinter M, König F, Bodingbauer M, Wrba F, Rasoul-Rockenschaub S, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Osteopontin expression predicts overall survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients beyond the Milan criteria. J Hepatol. 2011;54:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imaeda AB, Watanabe A, Sohail MA, Mahmood S, Mohamadnejad M, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Mehal WZ. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is dependent on Tlr9 and the Nalp3 inflammasome. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:305–314. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miura K, Kodama Y, Inokuchi S, Schnabl B, Aoyama T, Ohnishi H, Olefsky JM, Brenner DA, Seki E. Toll-like receptor 9 promotes steatohepatitis by induction of interleukin-1beta in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:323–324.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gieling RG, Wallace K, Han YP. Interleukin-1 participates in the progression from liver injury to fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1324–G1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90564.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrasek J, Dolganiuc A, Csak T, Kurt-Jones EA, Szabo G. Type I interferons protect from Toll-like receptor 9-associated liver injury and regulate IL-1 receptor antagonist in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:697–708.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petrasek J, Bala S, Csak T, Lippai D, Kodys K, Menashy V, Barrieau M, Min SY, Kurt-Jones EA, Szabo G. IL-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammasome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3476–3489. doi: 10.1172/JCI60777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathews S, Gao B. Therapeutic potential of interleukin 1 inhibitors in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;57:2078–2080. doi: 10.1002/hep.26336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stickel F, Hampe J. Genetic determinants of alcoholic liver disease. Gut. 2012;61:150–159. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osterreicher CH, Halangk J, Berg T, Patsenker E, Homann N, Hellerbrand C, Seitz HK, Eurich D, Stickel F. Evaluation of the transforming growth factor beta1 codon 25 (Arg--& gt; Pro) polymorphism in alcoholic liver disease. Cytokine. 2008;42:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stickel F, Osterreicher CH, Halangk J, Berg T, Homann N, Hellerbrand C, Patsenker E, Schneider V, Kolb A, Friess H, et al. No role of matrixmetalloproteinase-3 genetic promoter polymorphism 1171 as a risk factor for cirrhosis in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:959–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krawczyk M, Müllenbach R, Weber SN, Zimmer V, Lammert F. Genome-wide association studies and genetic risk assessment of liver diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:669–681. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian C, Stokowski RP, Kershenobich D, Ballinger DG, Hinds DA. Variant in PNPLA3 is associated with alcoholic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trepo E, Guyot E, Ganne-Carrie N, Degre D, Gustot T, Franchimont D, Sutton A, Nahon P, Moreno C. PNPLA3 (rs738409 C& gt; G) is a common risk variant associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in alcoholic cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;55:1307–1308. doi: 10.1002/hep.25518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trépo E, Gustot T, Degré D, Lemmers A, Verset L, Demetter P, Ouziel R, Quertinmont E, Vercruysse V, Amininejad L, et al. Common polymorphism in the PNPLA3/adiponutrin gene confers higher risk of cirrhosis and liver damage in alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2011;55:906–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seth D, Daly AK, Haber PS, Day CP. Patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3: a case in point linking genetic susceptibility for alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1463–1465. doi: 10.1002/hep.23606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burza MA, Molinaro A, Attilia ML, Rotondo C, Attilia F, Ceccanti M, Ferri F, Maldarelli F, Maffongelli A, De Santis A, et al. PNPLA3 I148M (rs738409) genetic variant and age at onset of at-risk alcohol consumption are independent risk factors for alcoholic cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34:514–520. doi: 10.1111/liv.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]