Abstract

AIM: To compare the short-term outcomes of patients who underwent proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition (PGJI) with those undergoing total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis (TGRY).

METHODS: From January 2009 to January 2011, thirty-five patients underwent PGJI, and forty-one patients underwent TGRY. The surgical efficacy and short-term follow-up outcomes were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS: There were no differences in the demographic and clinicopathological characteristics. The mean operation duration and postoperative hospital stay in the PGJI group were statistically longer than those in the TGRY group (P = 0.00). No anastomosis leakage was observed in two groups. No statistically significant difference was found in endoscopic findings, Visick grade or serum albumin level. The single-meal food intake in the PGJI group was more than that in the TGRY group (P = 0.00). The PG group showed significantly better hemoglobin levels in the second year (P = 0.02). The two-year survival rate was not significantly different (PGJI vs TGRY, 93.55% vs 92.5%, P = 1.0).

CONCLUSION: PGJI is a safe, radical surgical method for proximal gastric cancer and leads to better outcomes in terms of the single-meal food intake and hemoglobin level, compared with TGRY in the short term.

Keywords: Proximal gastric cancer, Proximalgastrectomy with jejunal interposition, Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis

Core tip: For proximal gastric cancer, total gastrectomy is widely accepted because of the lower incidence of reflux esophagitis. However, the continuity of the digestive tract, food storage and nutritional status should be considered after radical surgery for proximal gastric cancer. We conducted this study to compare proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition (PGJI) and total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis (TGRY) for proximal gastric cancer. Based on our two-year follow-up, the single-meal food intake in the PGJI group was more than that in the TGRY group, and the hemoglobin level was well maintained in the PGJI group. The two-year survival rate was not significantly different.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is estimated to be the fourth most common cancer and the second most frequent cause of cancer death in the world[1]. In both Western and Asian countries, the incidence of cancer in the upper third of the stomach has been increasing recently[2-5]. Proximal gastrectomy with gastroesophagectomy (PGGE) and total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis (TGRY) are the most common surgical approaches for cancer located in the upper third of the stomach[6-12]. As a function-preserving operation, PGGE can retain the distal stomach, but a high incidence of reflux esophagitis is observed by endoscopic examination[13-16]. TGRY can reduce the incidence of reflux esophagitis but is associated with postoperative dumping syndrome and poor food intake[17-19]. However, the continuity of the digestive tract, food storage and nutritional status should be considered after radical surgery for proximal gastric cancer. A sphincter-substituting reconstruction called jejunal interposition after proximal gastrectomy has been reported in certain studies[13,20-27]. Theoretically, this modified surgical method can minimize reflux symptoms and improve food intake compared with the two above-mentioned surgical methods. However, these reports differ in their conclusions. We conducted this study to compare proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition (PGJI) to TGRY in terms of surgical duration, surgical complications, postoperative hospital stay, Visick grade, food intake, endoscopic findings, and nutrition status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient indications

The patients’ indications were as follows: (1) tumors of all patients must be located in the upper third of the stomach; (2) clinically staged as T1-2N0M0; (3) estimated to have more than half of the stomach remained; and (4) be voluntary and sign an informed consent form.

Study design

Seventy-six patients were included in our study between January 2009 and January 2011 in our department. All patients had to undergo electronic gastroscopy, a gastrointestinal barium meal, computed tomography and a histopathological examination before the operation. Based on the admission time, these patients were semi-randomly classified into two groups: PGJI and TGRY. No organ was subjected to a combined resection such as splenectomy and cholecystectomy in our study. All the patients underwent R0 resection, and tumor rupture was not apparent during the surgery. The lower edge of the tumor was at least 5 cm. The resected specimens in our study were classified according to the AJCC cancer staging guidelines (7th ed)[28]. In this study, 35 patients underwent PGJI, and 41 patients underwent TGRY. The characteristics of these patients, such as gender, age, surgical duration, pathological stage, common complications, hospital stay and outcomes of follow-up were collected. The study obtained IRB approval.

Surgical procedures

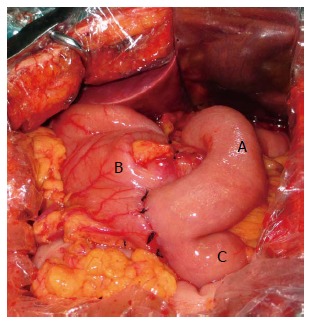

PGJI: For the proximal gastrectomy, the stomach was transected at least 5 cm from the lower edge of the tumor, and the esophagus was transected 3-4 cm from the cardia. Concurrently, the D2 lymph nodes, which were defined in the AJCC cancer staging guidelines, were dissected. After the jejunum was divided 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz, the distal jejunum was placed posterior to the transverse colon. An end-to-side anastomosis was performed. One 25 mm circular stapler was used for the esophagojejunostomy, and one 100 mm closure was used for the jejunal stump. The side-to-side gastrojejunostomy was performed 20 cm distal from the esophagojejunostomy site. The end-to-side jejunojejunostomy was performed 20-30 cm distal to the gastrojejunostomy site. Two 25 mm circular staplers and two 100 mm closures were used for the gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Jejunal interposition reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy. A: Interposed jejunum; B: Remnant stomach; C: Distal jejunum.

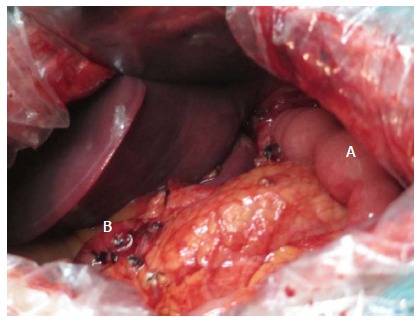

TG: After the total gastrectomy and the D2 lymph node dissection were completed, the jejunum was transected 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz and placed posterior to the transverse colon. Esophagojejunostomy with one 25 mm circular stapler and one 100 mm closure was performed. Jejunojejunostomy with one 25 mm circular stapler and one 100 mm closure was performed 50-60 cm distal from the anastomosis site (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. A: Roux jejunum; B: Duodenal stump.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 19.0 statistical package was used to perform all statistical analyses. All data are presented as mean and standard deviation. For categorical variables, Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used. For continuous variables, Student’s t-test was used. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Seventy-six patients with gastric cancer were included in our study. In the PGJI group, the median patient age was 56.97 years, and there were 22 men and 13 women; in the TGRY group, the median patient age was 56.19 years, and there were 30 men and 11 women. There was no significant difference between the PGJI group and the TGRY group in age or sex. The mean surgical duration was significantly longer in the PGJI group (PGJI vs TGRY: 205.08 min vs 152.73 min; P = 0.00). No differences were observed between the two groups for lymph nodes dissected (PGJI vs TGRY: 29.80 vs 31.12; P = 0.16), histological grade (P = 0.45) or pathological stage (P = 0.92). Anastomosis leakage was not found in the two groups. There was a marked difference in the hospital stay (from the first day in the hospital to discharge) between the PGJI group and the TGRY group (PGJI vs TGRY: 17.31 vs 16.39; P = 0.003).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | Proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition (n = 35) | Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis (n = 41) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 57.26 ± 9.71 | 56.19 ± 11.42 | 0.67 |

| Gender (M/F) | 22:13 | 30:11 | 0.34 |

| Surgical duration(min) | 205.08 ± 7.60 | 152.73 ± 7.16 | 0.00 |

| Lymph nodes dissected | 29.80 ± 3.85 | 31.12 ± 4.40 | 0.16 |

| Anastomosis leakage | 0 | 0 | |

| Surgical site infection | 0 | 0 | |

| Postoperative hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | |

| Hospital stay (d) | 17.31 ± 1.39 | 16.39 ± 1.22 | 0.003 |

| Histological grade (n) | 0.45 | ||

| G1/G2 (differentiated) | 14 | 13 | |

| G3/G4 (undifferentiated) | 21 | 28 | |

| Pathological T factor | 0.92 | ||

| pT1 | 10 | 14 | |

| pT2 | 7 | 6 | |

| pT3 | 17 | 20 | |

| pT4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Pathological N factor | 0.45 | ||

| pN0 | 28 | 32 | |

| pN1 | 6 | 9 | |

| pN2 | 1 | 0 | |

| pN3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pathological stage | 0.55 | ||

| IA | 10 | 14 | |

| IB | 3 | 1 | |

| IIA/IIB | 20 | 25 | |

| IIIA | 2 | 1 | |

At approximately the sixth month after surgery, 31 patients completed endoscopic examinations in the PGJI group, and 40 patients completed endoscopic examinations in the TGRY group. Reflux esophagitis was found in two PGJI patients, and in two TGRY patients. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.59). Anastomotic inflammation was found in 20 PGJI patients and in 23 TGRY patients. However, no obvious symptoms were found in any group, and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.56). One PGJI patient was found to have an anastomotic ulcer and cured by administration of a proton pump inhibitor for four weeks (Table 2). The Visick grading system was used to evaluate the postoperative quality of life; these outcomes are listed in Table 3. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.58; P = 0.36).

Table 2.

Endoscopic findings in the sixth month after surgery

| PGJI (n = 31) | TGRY (n = 40) | P value | |

| Refluxesophagitis | 2 | 2 | 0.59 |

| Anastomotic inflammation | 20 | 23 | 0.56 |

| Anastomotic ulcer | 1 | 0 |

TGRY: Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis; PGJI: Proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition.

Table 3.

Visick grade after operation

| PGJI | TGRY | P value | ||

| The time of discharge (n = 76) | 1 | 19 | 23 | 0.58 |

| 2 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| The sixth month after surgery (n = 71) | 1 | 24 | 25 | 0.36 |

| 2 | 6 | 9 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 1 |

TGRY: Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis; PGJI: Proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition.

In the twelfth month after surgery, the single meal food intake of 28 PGJI patients and 20 TGRY patients was same as before surgery, and the difference was significant, with a P value of 0.00 (Table 4). With respect to the postoperative indicators of nutritional status, the hemoglobin and serum albumin levels sharply decreased, and then gradually increased during the second year after the surgery. In the second year after surgery, the difference in the hemoglobin levels was statistically significant. The difference in the serum albumin levels was not statistically significant during the two-year follow-up (Table 5).

Table 4.

Number of meals per day in the twelfth month after surgery

| Number of meals per day | N (TGRY) | N (PGJI) | P value |

| 3 | 20 | 28 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 17 | 3 | |

| 5 | 3 | 0 |

TGRY: Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis; PGJI: Proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition.

Table 5.

Postoperative indicators of nutritional status

| TRGY | PGJI | P value | |

| Hemoglobin level (g/L) | |||

| Preoperation | 122.75 ± 18.74 | 122.23 ± 19.98 | 0.91 |

| Discharge | 107.95 ± 10.67 | 102.96 ± 12.92 | 0.08 |

| One year after surgery | 111.28 ± 10.75 | 114.35 ± 10.24 | 0.23 |

| Two years after surgery | 118.10 ± 10.08 | 123.23 ± 7.73 | 0.02 |

| Serum albumin level (g/L) | |||

| Preoperation | 37.57 ± 2.36 | 35.06 ± 2.22 | 0.75 |

| Discharge | 31.72 ± 2.40 | 31.63 ± 2.12 | 0.12 |

| One year after surgery | 36.70 ± 6.94 | 38.12 ± 3.02 | 0.10 |

| Two years after surgery | 39.84 ± 6.23 | 41.10 ± 3.18 | 0.45 |

TGRY: Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis; PGJI: Proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition.

Seventy-one patients completed the follow-up. Two patients died from retroperitoneal metastasis in the PGJI group. One patient died from liver metastasis, one patient from retroperitoneal metastasis and one patient from malnutrition in the TGRY group. The 2-year survival rate was not statistically significant (PGJI vs TGRY: 93.55% vs 92.5%; P = 1.0).

DISCUSSION

Proximal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy were the common surgical approaches for proximal gastric cancer[6-9]. Proximal gastrectomy maintains the upper digestive function but cannot prevent gastroesophageal reflux due to absence of the cardia. Total gastrectomy can reduce reflux after the entire stomach dissection but changes the upper digestive function. Bloating, anemia, dumping syndrome and malnutrition are often found in these patients[29,30]. Therefore, both proximal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy are not ideal surgical approaches for cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Theoretically, maximizing the retention of the stomach with a radical dissection is the best surgical approach. In this sense, PGJI should be the best surgical approach because the distal stomach is retained to maintain the normal digestive function and the jejunal interposition substitutes for the cardiac sphincter and reduces gastroesophageal reflux. However, it remains controversial whether PGJI provides a better outcome compared with total gastrectomy[20,22,31]. We conducted this comparative study to clarify whether PGJI is better than total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer.

In our study, all patients were from a single institution and all operations were performed by a specialized gastric surgeon who had over 10 years of experience in gastric surgery. This study design standardized our surgical procedure and avoided operation-derived error. Theoretically, because one additional gastrojejunostomy is required to be performed, the surgical duration of PGJI should be longer than that of TG. In the present study, the PGJI had a longer surgical duration than the TGRY. At the same time, no patient died from surgical complications in any group. However, TG was better than PGJI in terms of the postoperative hospital stay.

Compared to PG with gastroesophagectomy, TG has lower incidence of reflux esophagitis[30,32]. The interposed jejunum is similar to the Roux jejunum with respect to the cardiac sphincter function for preventing food regurgitation. Related research has also confirmed that PGJI improves reflux esophagitis, compared with esophagogastrostomy[13,33]. In the present study, the incidence of reflux esophagitis in the PGJI group was 6.5%. The reported reflux esophagitis incidence of 1.7%-5.0% is lower than our result[13,20,33]. This difference might be caused by the length of the interposed jejunum. In our study, the length was 20 cm, which is longer than the reported data. Theoretically, longer interposed jejunum can reduce the incidence of reflux esophagitis. However, the clinical result is not comparable to our anticipation. The limited sample size in our study might be an important reason for this mismatched result. Nozaki and Namikawa reported that the incidence of reflux esophagitis does not significantly differ between the PGJI and TGRY groups[20,34]. This result was also obtained in our study.

Most of the PGJI patients and half of the TGRY patients can eat three times per day in the twelfth month after surgery. The difference was statistically significant. The function-preserving operation retained the distal stomach, increased the single-meal food intake, reduced the number of meals and improved the quality of life. Serum vitamin B12 is the most important factor for maintaining the hemoglobin level and was significantly poorer in the TGRY group than in the PGJI group[29,35,36]. In our study, the hemoglobin level difference was statistically significant in the second year. In the second year, six patients with macrocytic anemia were found in the TGRY group, and two patients with macrocytic anemia were found in the PGJI group. The difference was possibly more obvious during a longer follow-up term. Moreover, the Visick grade and two-year survival rate did not differ between the two groups. However, we recognize the limitations of the sample size in the present study, and the follow-up time is insufficient to clarify the long-term quality of life and overall survival.

In conclusion, PGJI can be performed as safely as TGRY and should be recommended because it achieves better food intake in the early period and the same survival rate. Further follow-up is necessary to confirm the long-term quality of life and overall survival of PGJI patients.

COMMENTS

Background

Proximal gastrectomy with gastroesophagectomy (PGGE) and total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis (TGRY) are the most common surgical approaches for cancer located in the upper third of the stomach. As a function-preserving operation, PGGE can retain the distal stomach, but a high incidence of reflux esophagitis is observed by endoscopic examination. TGRY can reduce the incidence of reflux esophagitis but is associated with postoperative dumping syndrome and poor food intake.

Research frontiers

Theoretically, a sphincter-substituting reconstruction called jejunal interposition after proximal gastrectomy can minimize reflux symptoms and improve food intake compared with the two above-mentioned surgical methods. The authors conducted this study to compare proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition (PGJI) to TGRY.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Based on our follow-up, the single-meal food intake in the PGJI group was more than that in the TGRY group and the hemoglobin level was well maintained in the PGJI group. Although the number of patients in the study was limited, the results of a 2-year follow-up demonstrated that the overall survival rates were not significantly different.

Applications

The current follow-up outcomes show that PGJI can be performed as safely as TGRY and should be recommended because it achieves a better food intake during the early period and the same survival rate. Further follow-up is required to establish the nutrition status and overall survival rates.

Terminology

Jejunal interposition is an anastomotic method after total gastrectomy and distal gastrectomy. The interposed jejunum is placed between the esophagus and the duodenum or gastric stump.

Peer review

The aim of this study was to compare the short-term outcomes of patients who underwent PGJI with those who underwent total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. The study is interesting and significant in the field, and it will most likely have an impact on the treatment of cancers in the upper third of the stomach (although some similar studies have been published).

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Suo J, Tsukada T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr RM, Lynch JP. At the crossroads in the management of gastroesophageal junction carcinomas-where do we go from here? Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008;2:253–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiologic trends in esophageal and gastric cancer in the United States. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:235–256. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehdev A, Catenacci DV. Gastroesophageal cancer: focus on epidemiology, classification, and staging. Discov Med. 2013;16:103–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Kaneko S, Sobue T. Trends in reported incidences of gastric cancer by tumour location, from 1975 to 1989 in Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:808–815. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen L, Chen XZ, Wu B, Chen XL, Wang L, Yang K, Zhang B, Chen ZX, Chen JP, Zhou ZG, et al. Total vs. proximal gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:633–640. doi: 10.5754/hge11834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pu YW, Gong W, Wu YY, Chen Q, He TF, Xing CG. Proximal gastrectomy versus total gastrectomy for proximal gastric carcinoma. A meta-analysis on postoperative complications, 5-year survival, and recurrence rate. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:1223–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park do J, Kim HH. Comparative study of clinical outcomes between laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy (LAPG) and laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) for proximal gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:282–289. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansson LE, Ekström AM, BergströmD Sc R, Nyrén O. Carcinoma of the gastric cardia: surgical practices and short-term operative results in a defined Swedish population. World J Surg. 2000;24:473–478. doi: 10.1007/s002689910075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masuzawa T, Takiguchi S, Hirao M, Imamura H, Kimura Y, Fujita J, Miyashiro I, Tamura S, Hiratsuka M, Kobayashi K, et al. Comparison of perioperative and long-term outcomes of total and proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective study. World J Surg. 2014;38:1100–1106. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butte JM, Waugh E, Parada H, De La Fuente H. Combined total gastrectomy, total esophagectomy, and D2 lymph node dissection with transverse colonic interposition for adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. Surg Today. 2011;41:1319–1323. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4412-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondoh Y, Okamoto Y, Morita M, Nabeshima K, Nakamura K, Soeda J, Ogoshi K, Makuuchi H. Clinical outcome of proximal gastrectomy in patients with early gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2007;32:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tokunaga M, Ohyama S, Hiki N, Hoshino E, Nunobe S, Fukunaga T, Seto Y, Yamaguchi T. Endoscopic evaluation of reflux esophagitis after proximal gastrectomy: comparison between esophagogastric anastomosis and jejunal interposition. World J Surg. 2008;32:1473–1477. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Evaluation of symptoms related to reflux esophagitis in patients with esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:697–701. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-0921-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiraishi N, Hirose R, Morimoto A, Kawano K, Adachi Y, Kitano S. Gastric tube reconstruction prevented esophageal reflux after proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:78–79. doi: 10.1007/s101209800023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinohara T, Ohyama S, Muto T, Kato Y, Yanaga K, Yamaguchi T. Clinical outcome of high segmental gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Br J Surg. 2006;93:975–980. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang CC, Lien HH, Wang PC, Yang JC, Cheng CY, Huang CS. Quality of life in disease-free gastric adenocarcinoma survivors: impacts of clinical stages and reconstructive surgical procedures. Dig Surg. 2007;24:59–65. doi: 10.1159/000100920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jentschura D, Winkler M, Strohmeier N, Rumstadt B, Hagmüller E. Quality-of-life after curative surgery for gastric cancer: a comparison between total gastrectomy and subtotal gastric resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1137–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y, Yang Y. Study for the quality of life following total gastrectomy of gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:669–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nozaki I, Hato S, Kobatake T, Ohta K, Kubo Y, Kurita A. Long-term outcome after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for gastric cancer compared with total gastrectomy. World J Surg. 2013;37:558–564. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1894-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeshita K, Saito N, Saeki I, Honda T, Tani M, Kando F, Endo M. Proximal gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition for the treatment of early cancer in the upper third of the stomach: surgical techniques and evaluation of postoperative function. Surgery. 1997;121:278–286. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kikuchi S, Nemoto Y, Katada N, Sakuramoto S, Kobayashi N, Shimao H, Watanabe M. Results of follow-up endoscopy in patients who underwent proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:304–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasoshima T, Denno R, Ura H, Mukaiya M, Yamaguchi K, Hirata K. Development of an ulcer in the side-to-side anastomosis of a jejunal pouch after proximal gastrectomy reconstructed by jejunal interposition: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:1270–1273. doi: 10.1007/BF02482813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwata T, Kurita N, Ikemoto T, Nishioka M, Andoh T, Shimada M. Evaluation of reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy: prospective comparative study of jejunal interposition and jejunal pouch interposition. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:301–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takagawa R, Kunisaki C, Kimura J, Makino H, Kosaka T, Ono HA, Akiyama H, Endo I. A pilot study comparing jejunal pouch and jejunal interposition reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy. Dig Surg. 2010;27:502–508. doi: 10.1159/000321224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinoshita T, Gotohda N, Kato Y, Takahashi S, Konishi M, Kinoshita T. Laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for gastric cancer in the proximal third of the stomach: a retrospective comparison with open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:146–153. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka T, Takayama T, Matsumoto S, Wakatsuki K, Enomoto K, Migita K, Ito M, Nakajima Y. Postoperative functional evaluation after pylorus-preserving nearly-total gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:200–206. doi: 10.5754/hge12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. New York: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo CH, Sohn BH, Han WK, Pae WK. Proximal gastrectomy reconstructed by jejunal pouch interposition for upper third gastric cancer: prospective randomized study. World J Surg. 2005;29:1592–1599. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.An JY, Youn HG, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. The difficult choice between total and proximal gastrectomy in proximal early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196:587–591. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S, Kakisako K, Inomata M, Yasuda K. Clinical outcome of proximal versus total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:1150–1154. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo CH, Sohn BH, Han WK, Pae WK. Long-term results of proximal and total gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma of the upper third of the stomach. Cancer Res Treat. 2004;36:50–55. doi: 10.4143/crt.2004.36.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katai H, Morita S, Saka M, Taniguchi H, Fukagawa T. Long-term outcome after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for suspected early cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Br J Surg. 2010;97:558–562. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Namikawa T, Oki T, Kitagawa H, Okabayashi T, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Impact of jejunal pouch interposition reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer on quality of life: short- and long-term consequences. Am J Surg. 2012;204:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bae JM, Park JW, Yang HK, Kim JP. Nutritional status of gastric cancer patients after total gastrectomy. World J Surg. 1998;22:254–260; discussion 260-261. doi: 10.1007/s002689900379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim CH, Kim SW, Kim WC, Kim JS, Cho YK, Park JM, Lee IS, Choi MG, Song KY, Jeon HM, et al. Anemia after gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: long-term follow-up observational study. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6114–6119. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]