Background: Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger-retinoic acid receptor α (PLZF-RARα) is a transcriptional repressor generated by a chromosomal translocation between the PLZF and RARα genes in acute promyelocyteic leukemia patients.

Results: The transcriptional regulation of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα involves the competitive binding of p53, RARα, and Sp1, the modification of histones, and DNA methylation at the promoter.

Conclusion: PLZF-RARα increases cell proliferation by repressing p21 expression.

Significance: Oncoprotein PLZF-RARα represses transcription of the CDKN1A.

Keywords: Leukemia, Oncogene, p53, Transcription Regulation, Transcription Repressor, PLZF-RAR, p21WAF/CDKN1A

Abstract

Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger-retinoic acid receptor α (PLZF-RARα) is an oncogene transcriptional repressor that is generated by a chromosomal translocation between the PLZF and RARα genes in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL-type) patients. The molecular interaction between PLZF-RARα and the histone deacetylase corepressor was proposed to be important in leukemogenesis. We found that PLZF-RARα can repress transcription of the p21WAF/CDKN1A gene, which encodes the negative cell cycle regulator p21 by binding to its proximal promoter Sp1-binding GC-boxes 3, 4, 5/6, a retinoic acid response element (RARE), and distal p53-responsive elements (p53REs). PLZF-RARα also acts as a competitive transcriptional repressor of p53, RARα, and Sp1. PLZF-RARα interacts with co-repressors such as mSin3A, NCoR, and SMRT, thereby deacetylating histones Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 at the CDKN1A promoter. PLZF-RARα also interacts with the MBD3-NuRD complex, leading to epigenetic silencing of CDKN1A through DNA methylation. Furthermore, PLZF-RARα represses TP53 and increases p53 protein degradation by ubiquitination, further repressing p21 expression. Resultantly, PLZF-RARα promotes cell proliferation and significantly increases the number of cells in S-phase.

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)2 is characterized by the clonal expansion of malignant myeloid cells that are blocked at the promyelocytic stage of hematopoietic differentiation (1). The RARα gene fuses to the PLZF gene at the t(11;17)(q23;q21) chromosomal translocation, leading to expression of a PLZF-RARα fusion protein that initiates APL (2). The PLZF-RARα fusion protein contains the entire N-terminal transcriptional effector regions and the first two zinc fingers of PLZF and all of RARα except the N-terminal A activation domain AF1. PLZF-RARα contains functional domains that are important to its protein functions, including transcriptional repression the poxvirus and zinc finger (POZ) domain of PLZF and the DNA binding domain of RARα. These structural features may explain the leukemogenic properties of this particular fusion protein. RARα binds to retinoic acid response elements (RAREs, direct repeats of (A/G)G(G/T)TCA separated by 2 or 5 nucleotides), located in the promoters of many genes. RARα normally binds to RARE sites as a heterodimer with RXR. PLZF-RARα also binds to RAREs as a heterodimer with RXR (3, 4).

The PLZF-RARα oncoprotein functions as a transcriptional repressor in part by recruiting transcriptional corepressors and histone deacetylases (HDACs). However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the role of PLZF-RARα in oncogenesis and cell proliferation are poorly understood. It has been proposed that RARE-bound PLZF-RARα interacts with the NCoR/SMRT-HDAC complex to repress transcription, which appears to be a key pathogenic event in APL. Although the ligand/corepressor/coactivator binding domain of RARα alters its structure upon binding to RA ligand, releasing a corepressor and recruiting a coactivator instead (5–7), PLZF-RARα does not release the corepressor·HDAC complex in the presence of RA, thus acting as a dominant-negative mutant form of RARα in APL (8). Accordingly, ATRA resistance of cells containing the PLZF-RARα fusion gene disrupts the RA signaling pathway that mediates myeloid differentiation, resulting in arrest at the immature promyelocytic stage (6, 9–12). Although some developmentally important PLZF and RARα target genes have been reported, the targets of PLZF-RARα that are important in cell proliferation and oncogenesis remain largely unknown but are presumed to be genes that contain a RARE in their promoters (e.g. CDKN1A). PLZF-RARα antagonizes RARE-containing genes normally up-regulated by RARα in the presence of retinoic acid. Thus, transcription of a battery of RARα target genes important in differentiation, development, and cell cycle arrest can be aberrantly repressed, leading to proliferation of the undifferentiated promyelocytes (2, 3).

p21, encoded by CDKN1A, inhibits the activity of the cyclin/cdk2 complex and is a major regulator of mammalian cell cycle arrest (13, 14). CDKN1A is primarily regulated at the transcriptional and translational levels (15). Whereas the induction of p21 predominantly leads to cell cycle arrest, the repression of CDKN1A expression may have a variety of outcomes, including cell proliferation, depending on the cellular context (15). The CDKN1A gene also is a transcriptional target of p53, which acts on the CDKN1A promoter distal p53 regulatory elements (14, 16) and plays a crucial role in mediating G1, G2, and S phase growth arrests upon exposure to DNA-damaging agents (15). In addition, Sp1 family transcription factors are major regulators that affect CDKN1A gene expression by binding to the proximal promoter (17). Recently, Krüppel-like transcription factors were also characterized as key regulators of CDKN1A expression that affect p53- and proximal Sp1-mediated regulation of CDKN1A transcription (18–24). p21 expression is activated by retinoic acid, and the CDKN1A promoter has a RARE with RARα interacts to activate transcription.

MBD3 (methyl-CpG-binding domain protein-3) is a component of the Mi-2/NuRD (Mi-2/nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase) chromatin remodeling complex that contains a nucleosome remodeling ATPase, HDAC1 and HDAC2 (histone deacetylases-1 and -2), and metastasis-associated protein 2 (MTA2) (25). MBD3, which has no intrinsic DNA binding activity, is targeted to methylated promoters through interactions with MBD2. At the promoter, MBD3 maintains transcriptionally repressed chromatin (26). Interestingly, the MBD3 protein was shown to be associated with the proximal promoter of CDKN1A in cancer cells and was released upon treatment of the cells with an HDAC inhibitor (27). However, the function and mechanism of MBD3 association with the CDKN1A promoter remains largely uncharacterized. By recruiting HDACs and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), MBD3 may act as an important transcriptional repressor of p21 during oncogenic transformation and cell proliferation (28).

Consequently, we investigated whether and how the CDKN1A gene encoding p21, a key regulator of cell cycle control and cell proliferation, is controlled by PLZF-RARα at the transcriptional level. Here, we show how various molecular interactions between PLZF-RARα, p53, Sp1, and MBD3 are all involved in regulation of CDKN1A. We found that the transcriptional regulation of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα involves competitive binding of the transcription factors described above, modification of histones, and DNA methylation at the proximal CDKN1A promoter.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids, Antibodies, and Reagents

The pSG5-PLZF-RARα plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Jonathan D. Licht of Northwestern University (Chicago, IL). The CDKN1A-Luc plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Yoshihiro Sowa, Kyoto Perpetual University of Medicine (Kyoto, Japan). The pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc, pGL2-TP53-Luc, pGL2-ARF-Luc, pGL2-MDM2-Luc, pcDNA3.1-p53, pcDNA3.1-Sp1, pG5–5x(GC-box)-Luc, and pGL2–6x(p53RE)-Luc and co-repressor expression vectors were either reported elsewhere or prepared by us (23).

Antibodies against p21, p53, HDAC1, HDAC3, MDM2, PLZF, RARα, Sp1, GAPDH, Myc tag, Ac-H3, Ac-H4, H3K4-Me3, H3K9-Me3, MBD3, HP1, MTA2, DNMT1, DNMT3b, mSin3A, NCoR, and SMRT were purchased from Upstate, Chemicon, Cell Signaling Technology, Abcam, Calbiochem, and Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Most of the chemical reagents, including TSA (trichostatin A), 5-aza-dC (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine), and ATRA (all-trans-retinoic acid) were purchased from Sigma.

Cell Culture

HEK293, HL-60, HCT116 p53+/+, and HCT116 p53−/− cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen). HL-60 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS.

Ubiquitination Assays

H1299 cells grown in 10-cm dishes were co-transfected with 3 μg of pcDNA3-p53 and 2 μg of pcDNA3-His-ubiquitin in the presence or absence of pSG5-PLZF-RARα. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 20 μm MG132 for 3 h and harvested. The cell pellets were resuspended in RIPA buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% EDTA, 50 mm, Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, complete Mini-Protease mixture (1 tablet/50 ml, Roche Applied Science)). 500 μg of the cell lysates was incubated with MagneHisTM nickel particles for 1 h at 4 °C. After this step, the precipitated pellets were washed with buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA) three times, resuspended in 2× SDS sample buffer, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blot using an anti-p53 antibody.

Promoter DNA Methylation Analysis by Bisulfite DNA Sequencing

Genomic DNA was purified using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega). Methylation analyses were performed by bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA using the EpiXploreTM Methyl Detection kit (Clontech). The primer sequences used to amplify the CDKN1A promoter region were sense, 5′-AGGAGGGAAGTGTTTTTTTGTAGTA-3′, and antisense, 5′-ACAACTACTCACACCTCAACTAAC-3′. The PCR product was cloned using the pGEM®-T Easy vector System I kit (Promega). Mini-scale plasmid DNA was prepared from more than 30 individually transformed Escherichia coli clones and sequenced.

Transcriptional Analysis of ARF, MDM2, TP53, CDKN1A, and p53 Responsive Minimal Promoter

The pGL2-ARF-Luc, pGL2-MDM2-Luc, pGL2-TP53-Luc, pG13-Luc, pG5–5x(GC-box)-Luc, pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc promoter reporter fusion plasmids, and pSG5-PLZF-RARα, pcDNA3-HA-p53, and pCMV-LacZ were transiently cotransfected in various combinations into cells (HEK293, HCT116 p53+/+, HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60) with Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen). After 24–36 h of incubation, the cells were harvested and analyzed for luciferase activity. The reporter activity was normalized to either the total protein concentration or co-transfected β-galactosidase activity to correct for transfection efficiency.

Quantitative Real-time PCR (qPCR) of PLZF-RARα, MDM2, p53, GAPDH, and CDKN1A mRNA Expression in Cells

Total RNA was isolated from HEK293, HCT116 p53+/+, HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using 5 μg of total RNA, random hexamer (10 pmol), and SuperScript reverse transcriptase II (200 units) in a 20-μl reaction using a reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen). RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems). The following RT-qPCR oligonucleotide primer sets were used: PLZF-RARα forward, 5′-GAAGACGTACGGGTGCGAGCTC-3′ and PLZF-RARα reverse, 5′-GAAGACGTACGGGTGCGAGCTC-3′; MDM2 forward, 5′-CCCCTTAATGCCATTGAACCT-3′ and MDM2 reverse, 5′-ACTGGGCAGGGCTTATTCCT-3′; p53 forward, 5′-CCTGAGGTTGGCTCTGACTGTA-3′, and p53 reverse, 5′-AAAGCTGTTCCGTCCCAGTAGA-3′; p21 forward, 5′-AGGGGACAGCAGAGGAAG-3′ and p21 reverse, 5′-GCGTTTGGAGTGGTAGAAATCTG-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and GAPDH reverse, 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′.

Site-directed Mutagenesis of the CDKN1A Promoter

To investigate the role of each Sp1 binding site and RARα binding site, mutations were introduced into the p21 proximal promoter sequence using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The following oligonucleotides were used to introduce mutations into the core binding sequences of the GC-boxes and the RARE (only the top strands are shown): mSp1–2, 5′-CCCGGGCGGCGCGGTTTTCCGAGCGCGGGTCCCG-3′; mSp1–3, 3′-CCCGCCTCAAGGAGGCGGGAAAAGCGCTCGGCCC-5′; mSp1–4, 5′-CCCGCCTCCTTGAGGCTTTCCCGGGCGGGGCGGT-3′; mSp1–5/6, 5′-TGAGGCGGGCCCGGGCTTTGCGGTTGTATATCAG-3′; mRARE#1, 5′-CAAAGGTGAAGTCCAAAGGAGGTCAGGGGTGTG-3′; mRARE#2, 5′-CAGAAAGCAGGCAAAAATGAAGTCCAGGGGAG-3′; mRARE#1&2, 5′-CAAAAATGAAGTCCAAAGGAGGTCAGGGGTGTG-3′. For site-directed mutagenesis, 18 PCR cycles with denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, hybridization at 55 °C for 1 min, and extension at 68 °C for 10 min per cycle were used. The amplified mixtures were then treated with DpnI (Stratagene) at 37 °C for 1 h, and aliquots were used to transform competent E. coli. All constructs were confirmed through DNA sequencing with an ABI automatic DNA sequencer (Ramsey).

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholic acid, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, complete Mini-Protease mixture (1 tablet/50 ml, Roche Applied Science)). The cell extracts (40 μg) were separated using a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred onto Immuno-BlotTM PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), and blocked with 5% skim milk (BD Biosciences). The blotted membranes were then incubated with antibodies against PLZF, RARα (Santa Cruz), GAPDH (Chemicon), p21 (Cell Signaling), p53, HDAC1, NCoR, HDAC3, PLZF, and SMRT (Santa Cruz) and further incubated with either an anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to HRP (Vector Laboratories). Finally, antibody-bound protein bands were visualized using an ECL solution (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Quantitative Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (qChIP) Assays

HEK293, HCT116 p53+/+, HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60 cells were transfected with increasing amounts of pSG5-PLZF-RARα expression vector. The molecular interactions between PLZF-RARα and p53, Sp1, or RARα and various histone modifications within the CDKN1A proximal promoter were analyzed using a standard qChIP assay protocol as described elsewhere (23).

The degree of PLZF-RARα binding to p53RE-1, -2 and RARE, and Sp1-binding sites was analyzed by ChIP assays using an anti-PLZF, anti-RARα, and anti-HA tag antibody (Santa Cruz). The level of endogenous Sp1 and p53 protein binding was analyzed using polyclonal antibodies against anti-p53 (Santa Cruz), anti-Sp1 (Santa Cruz), anti-Ac-Histone 3, anti-Ac-Histone 4, anti-Histone H3K4-Me3, and anti-Histone H3K9-Me3 (Upstate). IgG was used as a negative control for the qChIP assays.

Quantitative PCR of the chromatin-immunoprecipitated DNA was performed using the following oligonucleotide primer sets, which were designed to amplify the upstream regulatory regions flanking the p53 and RARα binding sites and the CDKN1A proximal promoter region: p53RE-1 (bp −2307 to −1947) forward, 5′-CTGTGGCTCTGATTGGCTTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGTCTTTAGAGGTCTCCTGTCT-3′; p53RE-2 (bp −1462 to −1128) forward, 5′-CCACAGCAGAGGAGAAAGAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCTGCTCAGAGTCTGGAAATC-3′; RARE (bp −1020 to −1200) forward, 5′-GGGTTCTGTTTTTTAGTGGGATTTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGAAGTGTCTACTGGTTCTTCTGA-3′; and CDKN1A proximal promoter (bp −131 to +30) forward, 5′-GCGCTGGGCAGCCAGGAGCCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTGACTTCGGCAGCTGCTCAC-3′. To analyze histone H3 and H4 modifications within the CDKN1A proximal promoter (bp −131 to +100), the forward, 5′-GATCGGTACCGCGCTGGGCAGCCAGGAGCCT-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCGTCACCCGCGCACTTAGA-3′, primers were used. To analyze DNA methylation at the proximal CDKN1A promoter by ChIP, a Me-DIP kit designed to immunoprecipitate methylated DNA with an anti-methylated DNA antibody was used (Diagenode).

Immunoprecipitation Assays

HEK293, HCT116 p53+/+, HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60 cells (transfected with an expression vector, if necessary) were washed, pelleted, and resuspended in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, complete Mini Protease mixture (1 tablet/50 ml, Roche Applied Science)). Cell lysates were pre-cleared, and the supernatants were incubated overnight with an anti-PLZF (or anti-p53, anti-Sp1, anti-RARα, anti-MBD3, anti-MTA2, anti-HP1, anti-DNMT1, anti-DNMT3b, or anti-GAPDH) antibody on a rotating platform at 4 °C and then incubated with protein A-Sepharose Fast Flow beads. The beads were collected, washed, and resuspended in equal volumes of 5× SDS loading buffer. The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated using 8 and 10% SDS-PAGE. Western blots were performed with the appropriate antibodies as described above.

Oligonucleotide Pulldown Assays

HEK293, HCT116 p53+/+,HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60 cells were lysed in HKMG buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 100 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mm DTT, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40). The cell extracts were then incubated with 1 μg of biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides (p53RE-1, p53RE-2, RARE, Sp1–1, Sp1–2, Sp1–3, Sp1–4, and Sp1–5/6) for 16 h. Oligonucleotide sequences were as follows (only the top strands are shown): Sp1–1,5′-GATCGGGAGGGCGGTCCCG-3′; Sp1–2, 5′-GATCTCCCGGGCGGCGCG-3′; Sp1–3, 5′-GATCCGAGCGCGGGTCCCGGCTC-3′; Sp1–4, 5′-GATCCTTGAGGCGGGCCCG-3′; Sp1–5/6, 5′-GATCGGGCGGGGCGGTTGTATATCA-3′; RARE, 5′-GGCAAAGGTGAAGTCCAGGGGAGGTCAGGGGTGTG-3′; p53RE-1, 5′-GTCAGGAACATGTCCCAACATGTTGAGCTC-3′; p53RE-2, 5′-TAGAGGAAGAAGACTGGGCATGTCTGGGCA-3′; and 3′ UTR, 5′-TCCTGGAGCAGACCACCCCGC-3′. To collect the DNA-bound proteins, the mixtures were then incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads for 2 h, washed with HKMG buffer, and the precipitates collected by centrifugation. The precipitates were then analyzed by Western blots using antibodies against PLZF, Sp1, p53, or GAPDH, as described above.

Flow Cytometry for Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis

HEK293, HCT116 p53+/+, HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60 cells were transfected with either a PLZF-RARα expression or control vector. Transfected cells were washed, fixed with methanol, and stained with a solution containing propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) and ribonuclease A (100 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. The DNA content, cell cycle profiles, and forward scatter of the cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer set to 488 (excitation) and 575 nm (peak emission). The data were analyzed using ModFit LT 2.0 (Verity Software House) and WindMDI 2.8 (Joseph Trotter, Scripps Research Institute).

To analyze the effect of PLZF-RARα on apoptosis, HEK293, HCT116, p53+/+, HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60 cells were transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector. Cells were washed and stained with Annexin V-FITC (1:25, BD Biosciences) and propidium iodide (1 μg/ml, BD Biosciences) in Annexin V binding buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2) by incubating for 10–15 min at room temperature in the dark and then fixed for 15 min with chilled 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The apoptotic cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer, with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide excitation/emission wavelengths of 405/570 and 488/620 nm, respectively. The data were analyzed using CellQuest (BD Biosciences) and WindMDI 2.8 (Joseph Trotter, Scripps Research Institute).

MTT Assays

Confluent HEK293, HCT116 p53+/+, HCT116 p53−/−, and HL-60 cells grown on 10-cm culture dishes were transfected with either a PLZF-RARα expression vector or control vector, transferred to 6-well culture dishes and grown for 0–4 days. At days 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 20 μl of MTT/well (2 mg/ml). The precipitates were dissolved with 1 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide and the levels of cellular proliferation was determined by analyzing the conversion of MTT to formazan using a SpectraMAX 250 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) at 570 nm.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t test was used for all statistical analyses. p < 0.05 values were considered significant.

RESULTS

PLZF-RARα Stimulates Cell Proliferation and Increases the Number of Cells in S-phase

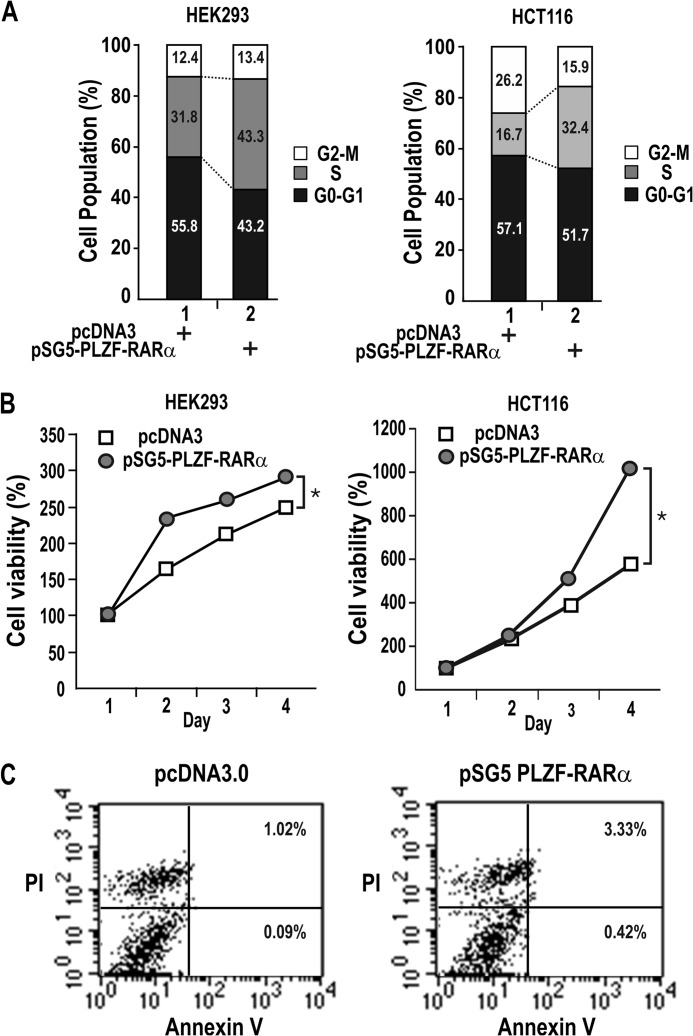

We tested whether the oncoprotein PLZF-RARα can promote cell proliferation in HEK293, HCT116 cells, and eventually in HL-60 myeloid cells in the later part of this study. Flow cytometry analysis of HEK293 and HCT116 cells transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression plasmid showed that PLZF-RARα stimulated cell cycle progression and increased the number of cells in S-phase (from 31.8 to 43.3%) (Fig. 1A). In agreement, MTT assays showed that PLZF-RARα significantly increased cell proliferation (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

PLZF-RARα promotes cell proliferation but does not induce apoptosis. A, FACS analysis of HEK293 and HCT116 cells transfected with either a pcDNA3 or pSG5-PLZF-RARα plasmid. B, MTT assay of cell proliferation. HEK293 and HCT116 cells transfected with either a pcDNA3 or pSG5-PLZF-RARα plasmid were grown for 1–4 days and analyzed for MTT to formazan conversion using colorimetry at 540–600 nm. *, p < 0.05. Mean values of three independent experiments are shown. Error bars are too small to see and represent S.D. C, FACS analysis of apoptosis. HEK293 cells were transfected with either a pcDNA3 or pSG5-PLZF-RARα plasmid. The cells were stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide 48 h after transfection. x axis, Annexin V-FITC staining; y axis, propidium iodide (PI) staining. The numbers shown in the two right quadrants represent the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis.

Because PLZF acts as a tumor suppressor with apoptotic activity in cells with a hematopoietic origin, we investigated whether PLZF-RARα induces apoptosis by analyzing HEK293 cells stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide. The cell populations undergoing early and late apoptosis were either minimal or negligible (from 1.11 to 3.75%) (Fig. 1C).

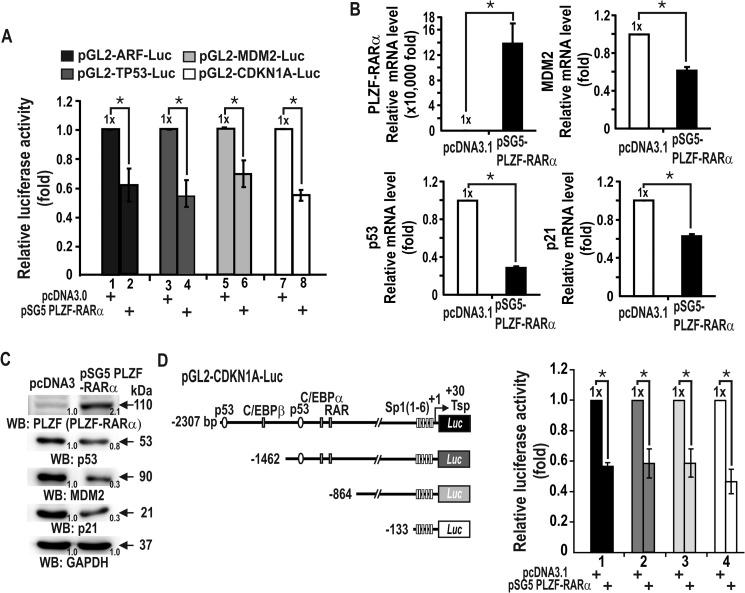

PLZF-RARα Is a Transcriptional Repressor of the CDKN1A Gene Encoding p21

To understand how PLZF-RARα increases cell proliferation and exerts oncogenic properties, we investigated whether the oncoprotein PLZF-RARα could stimulate cell proliferation by controlling genes of the p53 pathway, important for cell cycle regulation. Transient transcription assays of HEK293 cells showed that PLZF-RARα repressed transcription of ARF, MDM2, TP53, and in particular, CDKN1A (Fig. 2A). RT-qPCR and Western blot analyses revealed that ectopic PLZF-RARα also repressed the expression of endogenous TP53, MDM2, and CDKN1A at the transcriptional level (Figs. 2B and 3C). Thus, PLZF-RARα regulates the upstream regulatory genes that eventually affect CDKN1A expression. We also examined which region of the CDKN1A promoter is important for transcriptional repression by PLZF-RARα in HEK293 cells. PLZF-RARα repressed the transcription of the four different CDKN1A promoters in a similar fashion, suggesting that PLZF-RARα may repress transcription by acting at the proximal promoter, which has six Sp1-binding GC-boxes (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

PLZF-RARα represses the transcription of p53 pathway genes in HEK293 cells. A, transient transcription assays for the ARF, MDM2, TP53, and CDKN1A genes of the p53 pathway. The PLZF-RARα expression vector and promoter-luciferase fusion reporter plasmid were transiently co-transfected into HEK293 cells, and luciferase activity was measured. The results are the average of three independent assays. Bars, standard deviations. B and C, RT-qPCR and Western blot (WB) analyses showing PLZF-RARα and endogenous MDM2, TP53, and CDKN1A expression in HEK293 cells transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector. GAPDH, control. D, structures of the four CDKN1A promoter constructs tested and transient transcription assays for CDKN1A gene expression. The PLZF-RARα expression vector and various CDKN1A promoter-luciferase fusion reporter plasmids (shown on the left) were transiently co-transfected into HEK293 cells and luciferase activity was measured. *, p < 0.05; t test.

FIGURE 3.

PLZF-RARα represses transcriptional activation of CDKN1A by p53. A, transient transcription assays. HCT116 cells were transiently co-transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector and a pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc (−2.3 kb) reporter plasmid, after which the cells were treated with the DNA-damaging agent etoposide and analyzed for luciferase activity. B, transient transcription analysis in HCT116 p53−/− cells. Cells were transiently co-transfected with pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc WT (−2.3 kb), p53 and/or PLZF-RARα expression vectors and luciferase activity was measured. C and D, transient transcription assays for the p53-responsive minimal promoters. Saos-2 cells lacking p53 were cotransfected with pGL2–6x(p53RE)-Luc (or pG13-Luc), a PLZF-RARα expression vector and/or a p53 expression vector. p53RE, distal p53 binding element of the CDKN1A promoter pG13 containing 13 copies of the putative p53 binding element. E–H, transcriptional regulation of endogenous TP53 and CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα in HCT116 cells treated with etoposide, as shown by RT-qPCR and Western blot (WB) analysis. **, p < 0.05; *, p < 0.001; N.S., not significant; t test.

PLZF-RARα Represses Transcription of the CDKN1A Gene by Binding to the Distal p53 Binding Elements and Decreasing p53 Stability and TP53 Transcription

Treatment with the DNA damaging agent etoposide increased CDKN1A expression by inducing p53 in HCT116 cells, which was repressed by PLZF-RARα (Fig. 3A). In HCT116 p53−/− cells, ectopic p53 expression increased CDKN1A expression, which was also repressed by PLZF-RARα (Fig. 3B). An additional transcriptional analysis using a pG5–6x(p53RE)-Luc construct with five copies of the distal p53 binding elements of the CDKN1A showed that PLZF-RARα blocked transcriptional activation of CDKN1A by p53 in Saos-2 cells (Fig. 3C). We observed a similar PLZF-RARα-mediated transcriptional repression of pG13-Luc, which contains 13 copies of the putative p53 binding element (Fig. 3D). Overall, our data suggest that PLZF-RARα can inhibit transcriptional activation of the CDKN1A gene by p53 at the p53 response element (p53RE) of the distal CDKN1A promoter.

We next analyzed whether ectopic PLZF-RARα affected p53 binding induced by etoposide in HCT116 cells. Although etoposide treatment did not affect the expression of PLZF-RARα significantly, transcriptional activation of TP53 and CDKN1A by etoposide was potently repressed by PLZF-RARα at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3, E–H).

PLZF-RARα also repressed transcriptional activation of CDKN1A by etoposide or ectopic p53 (Fig. 3). We also tested whether PLZF-RARα repressed transcription of CDKN1A in the absence of p53. Transient transcription assays in HCT116 p53−/− cells showed that PLZF-RARα could repress transcription of CDKN1A (Fig. 4A), and MTT assays of the same cells showed that PLZF-RARα significantly increased cell proliferation by 2.5-fold (Fig. 4B). Western blot and RT-qPCR analyses revealed that ectopic PLZF-RARα also repressed the expression of endogenous CDKN1A at both the protein and mRNA levels in HCT116 p53−/− cells (Fig. 4, C–F). These results suggest that transcriptional repression of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα can be independent of p53.

FIGURE 4.

Transcription repression of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα can be independent of p53. A, transcription assays. HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells were transiently co-transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector and a pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc (−2.3 kb) reporter plasmid, after which the cells were treated with etoposide and analyzed for luciferase activity. B, MTT assay of cell proliferation. HCT116 p53−/− cells transfected with either a pSG5 or pSG5-PLZF-RARα plasmid were grown for 1–4 days and analyzed for the MTT to formazan conversion using colorimetry at 540–600 nm. C–F, RT-qPCR and Western blot (WB) analyses showing PLZF-RARα and endogenous p53 and p21 expression in the HCT116 p53−/− cells transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector. GAPDH, control. *, p < 0.05; N.S., not significant; t test.

Accordingly, PLZF-RARα may directly repress transcription of CDKN1A or indirectly, by repression of p53 activity or expression. Oligonucleotide pulldown assays showed that PLZF-RARα binds to and decreases p53 binding to p53REs (Fig. 5B). ChIP assays showed similar results in vivo (Fig. 5, C–G). Together, these results suggest that PLZF-RARα competes with p53 to bind to the two p53 binding elements and that this binding competition is important for transcriptional repression of CDKN1A. The transcription repression of TP53 by PLZF-RARα may also contribute indirectly to the repression of CDKN1A (Figs. 3, F and H; 5B, input lane 2, and 5I, input lane 2).

FIGURE 5.

PLZF-RARα represses CDKN1A gene transcription through binding competition with p53, TP53 transcriptional repression, and increased p53 ubiquitination. A, structure of the human CDKN1A gene promoter. The arrows at the p53 binding elements indicate the locations of the qChIP-PCR primer binding sites. Tsp(+1), transcription start site. B, oligonucleotide pulldown assay of PLZF-RARα binding to p53 response elements in the CDKN1A promoter. Extracts from HCT116 p53+/+ cells expressing ectopic PLZF-RARα were incubated with biotinylated oligonucleotides, incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads, and precipitated. The precipitates were analyzed by Western blot with the antibodies indicated. C–F, qChIP assay showing HA-PLZF-RARα/PLZF-RARα or p53 binding to the distal p53RE-1 and -2 of the endogenous CDKN1A gene in HCT116 p53+/+ cells. The cells were transfected with an increasing amount (0–9 μg) of pSG5-PLZF-RARα expression vector. Antibodies against PLZF, RARα, and p53 were used for ChIP. IgG, control. G, Western blot (WB) analyses showing PLZF-RARα and endogenous p53 expression in HCT116 p53+/+ cells transfected with an increasing amount (0–9 μg) of pSG5-PLZF-RARα expression vector. GAPDH, control. H and I, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of PLZF-RARα and p53. HCT116 p53+/+ cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti-RARα antibody and the precipitates were analyzed by Western blot using an anti-p53 antibody. Alternatively, the anti-p53 antibody was used first in the co-IP, and the anti-RARα antibody was used for Western blotting. J, ubiquitination assay for endogenous p53. H1299 cells were transfected with pcDNA3-His-ubiquitin or pSG5-PLZF-RARα in the various combinations indicated. The cells were cultured and treated with MG132 for 3 h prior to harvest. The cell lysates were then incubated with MagneHis nickel particles and the precipitated pellets were washed, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blot using a p53 antibody. *, p < 0.05; N.S., not significant; t test.

As protein-protein interactions between transcription factors can also repress transcription, we investigated whether PLZF-RARα directly interacts with p53. Co-immunoprecipitation and Western blot assays of HEK293 cells transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector revealed that PLZF-RARα interacts with p53 in vivo (Fig. 5H). Interestingly, we noticed that PLZF-RARα decreased the expression and acetylation of p53 (Fig. 5I). Ubiquitination assays and Western blot analyses further revealed that PLZF-RARα considerably increased p53 ubiquitination, likely decreasing p53 protein stability. In cells expressing ectopic PLZF-RARα, p53 expression was most likely low because of the combination of decreased p53 stability and transcriptional repression of TP53 (Figs. 3, F and H; and 5, H–J).

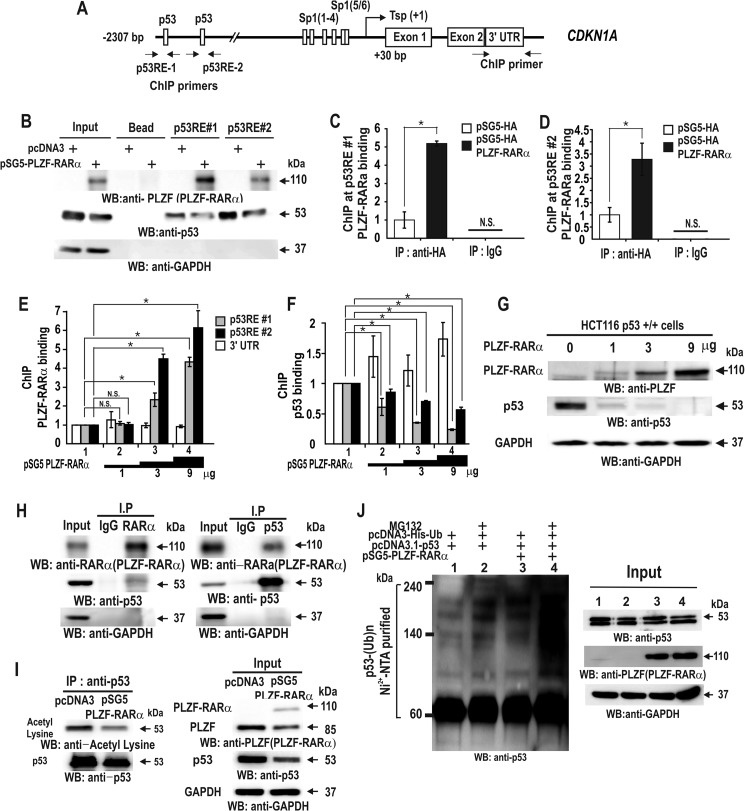

PLZF-RARα Binds to the Proximal GC Boxes and Interacts with Sp1 to Repress the Transcription of CDKN1A

PLZF-RARα can repress transcription by acting on the short proximal promoter (bp −131 to +30) of CDKN1A. The proximal promoter is GC-rich, contains six Sp1 binding sites (Sp1–1 to Sp1–6), and is important in transcriptional activation by Sp1 (Fig. 6A) (15, 17, 29). We found that Sp1 activated transcription of the pG5–5x(GC)-Luc reporter plasmid that contained Sp1-binding GC-boxes, which was also repressed by PLZF-RARα (Fig. 6, B and C).

FIGURE 6.

PLZF-RARα represses CDKN1A transcription by competing with Sp1 for binding to proximal promoter GC-boxes 3, 4, and 5/6, in vitro and in vivo. A, structure of the human CDKN1A promoter. The arrows indicate the binding positions of the qChIP oligonucleotide PCR primers. Tsp(+1), transcription start site. B, transcription analysis in HEK293 cells. Cells were transiently co-transfected with the pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc WT (−131 bp), Sp1 and/or PLZF-RARα expression vectors, and luciferase activity was measured. C, transcription assays. HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with the pG5–5x(GC box)-tk*-Luc, Sp1, and/or PLZF-RARα expression vectors and luciferase activity was measured. The GC-box is derived from the well defined Sp1 consensus binding sequence. D, identification of the functional elements in transcriptional repression by PLZF-RARα (left). The structures of the pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc WT (−131 bp) construct and the mutants generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the GC-box. X, mutation introduced; the GC box core GGG was replaced with TTT (right). Transcription analysis in HEK293 cells. Cells were transiently co-transfected with pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc WT or a mutant construct (−131 bp), and PLZF-RARα expression vector and luciferase activity were then measured. E, oligonucleotide pulldown assay showing PLZF-RARα binding to the proximal GC-boxes. HEK293 cell extracts were incubated with biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides and precipitated, as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The precipitates were analyzed for PLZF-RARα and Sp1 binding by Western blot (WB). F, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of PLZF-RARα and Sp1. HEK293 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti-RARα antibody and analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Sp1 antibody. Conversely, the lysates were also immunoprecipitated with the anti-Sp1 antibody and analyzed by Western blot with an anti-RARα antibody. G–I, qChIP assay showing competitive Sp1 and PLZF-RARα/HA-PLZF-RARα binding at the endogenous CDKN1A proximal promoter in HEK293 cells. The cells were transfected with an increasing amount (0–9 μg) of the PLZF-RARα expression vector. Antibodies against HA tag, PLZF, Sp1, and IgG (control) were used in the ChIP assays. *, p < 0.05; N.S., not significant; t test.

We also tested which GC-box at the CDKN1A promoter is important for transcriptional repression by PLZF-RARα. Site-directed mutagenesis of the proximal GC-boxes of reporter plasmids and transient transcription assays revealed that GC-boxes 3, 4, and 5/6 are important for transcriptional repression by PLZF-RARα, as mutations in these elements inhibited CDKN1A transcriptional repression by PLZF-RARα (Fig. 6D).

Oligonucleotide pulldown assays using HEK293 cells transfected with a control or PLZF-RARα expression vector also indicated that PLZF-RARα binds to these three elements and decreases Sp1 binding (Fig. 6E). PLZF-RARα expression did not affect Sp1 expression (Fig. 6, E and I). ChIP assays further revealed that HA-tagged PLZF-RARα or untagged PLZF-RARα bound to the proximal promoter region in vivo, and that the increased PLZF-RARα expression vector decreased endogenous Sp1 binding to the proximal promoter (Fig. 6, H and I). Additionally, co-immunoprecipitation and Western blot assays of HEK293 cells transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector revealed that PLZF-RARα and Sp1 interact with each other in vivo (Fig. 6, G–I). Our data indicate that PLZF-RARα is a GC-box-binding transcription factor that can compete with Sp1 at GC-boxes 3, 4, and 5/6 to repress the transcription of CDKN1A.

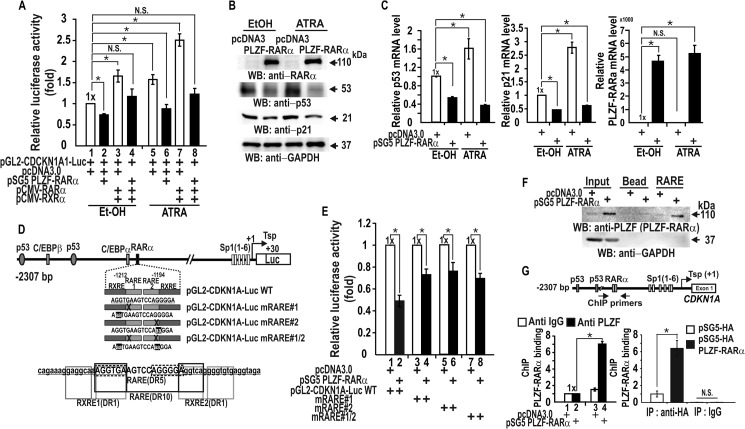

PLZF-RARα Binds to a Distal RARE Promoter Element to Repress Transcription of CDKN1A

It has previously been shown that RARα-RXR complexes can activate transcription of CDKN1A by acting on the RARE in the CDKN1A distal promoter region (bp −1212 to −1194) (15, 30). In addition, the PLZF-RARα fusion protein retains a functional RARα DNA binding domain, and dysregulation of RARα target gene expression has been proposed to be an underlying cause of oncogenesis (5, 31). Accordingly, we tested whether PLZF-RARα could represses transcription of a CDKN1A-reporter fusion gene and the endogenous CDKN1A gene in HEK293 cells. Co-expression of RXR and RARα increased transcription and, in the presence of ATRA, further activated transcription. Regardless of the presence of ATRA, PLZF-RARα repressed both the CDKN1A reporter (Fig. 7A) and endogenous CDKN1A at their protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 7, B and C). Interestingly, we noticed that ATRA treatment increased p53 expression and PLZF-RARα decreased p53 expression, but ATRA did not affect PLZF-RARα expression (Fig. 7, B and C). Decrease in p53 expression by PLZF-RARα could further decrease CDKN1A expression.

FIGURE 7.

PLZF-RARα represses the transcription of CDKN1A by binding to its RARE in vitro and in vivo. A, transcription assay for the CDKN1A promoter in the presence of PLZF-RARα and ATRA or EtOH control in HEK293 cells. Cells were transiently co-transfected with the pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc WT (−2.3 kb), PLZF-RARα and/or RXR-RARα expression vectors, treated with ATRA, and luciferase activity was measured. B and C, Western blot (WB) and RT-qPCR mRNA level analysis of the cell lysates transfected with control or PLZF-RARα expression vectors and treated with ATRA or EtOH control. D, structure of the human CDKN1A promoter showing point mutations within the RARE. RXRE, the binding sites for RXR are also indicated. E, CDKN1A transcription reporter assays. HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with pGL2-CDKN1A-Luc WT or one of the three RARE mutants (−2.3 kb) and the PLZF-RARα expression vector and/or control vector, and luciferase activity was measured. F, oligonucleotide pulldown assays showing PLZF-RARα binding to the RARE. HEK293 cell extracts were incubated with biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotide and analyzed, as described in the legend to Fig. 3I using an antibody against PLZF or IgG. G, qChIP assay showing PLZF-RARα binding at the RARE of the endogenous CDKN1A proximal promoter in HEK293 cells. The cells were transfected with HA-PLZF-RARα or PLZF-RARα expression vector. Antibodies against HA and PLZF and IgG were used in ChIP assays. The endogenous CDKN1A gene structure is shown. RAREs are indicated as RARα. The arrows indicate the binding positions of the qChIP oligonucleotide PCR primers flanking the RARE. Tsp(+1), transcription start site. *, p < 0.05; N.S., not significant; t test.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the RARE of the CDKN1A promoter in the reporter plasmid and transient transcription assays revealed that the RARE is important for PLZF-RARα-mediated transcriptional repression because the mutation of any of the bipartite RARE elements caused a loss of transcriptional repression (Fig. 7, D and E). Oligonucleotide pulldown assays indicated that PLZF-RARα binds the RARE (Fig. 7F). Moreover, ChIP assays of PLZF-RARα binding with both anti-PLZF and anti-HA antibodies revealed that ectopic PLZF-RARα binds to the RARE (Fig. 7G), resulting in CDKN1A transcriptional repression.

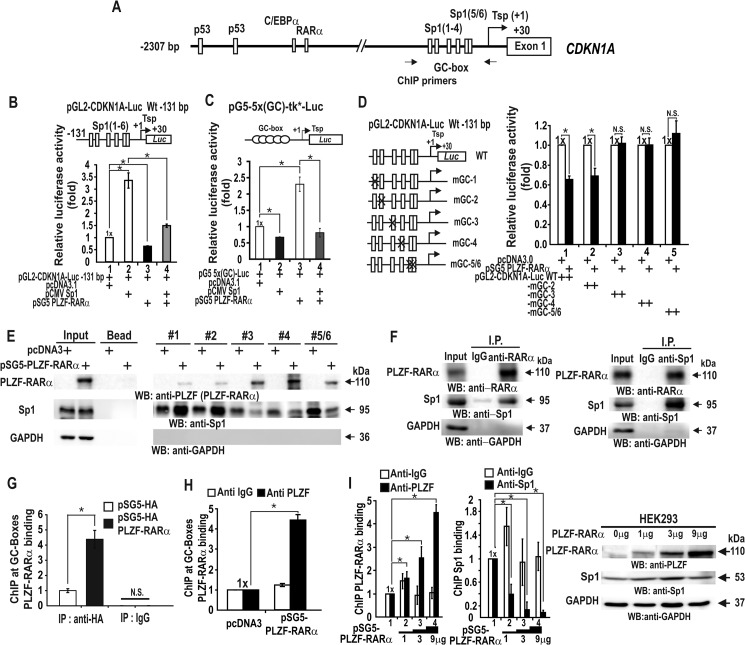

PLZF-RARα Epigenetically Silences the CDKN1A Proximal Promoter by Interacting with the MBD3·NuRD-HDAC3 Complex and DNMTs, Leading to DNA Methylation

PLZF was shown to repress transcription by interacting with the NCoR/SMRT corepressor (2). Because PLZF-RARα retains the domains of PLZF that are important for transcriptional repression, PLZF-RARα may inhibit transcription at the CDKN1A proximal promoter by interacting with the corepressor·HDAC complex. ChIP assays showed that expression of ectopic PLZF-RARα decreased acetylation of histones H3 and H4 at the CDKN1A proximal promoter by 40–65% (Fig. 8C). In addition, epigenetic markers of transcriptional repression (H3K9-Me3) and activation (H3K4-Me3) were increased or decreased, respectively, by PLZF-RARα (Fig. 8D).

FIGURE 8.

PLZF-RARα represses transcription of CDKN1A epigenetically by histone deacetylation and DNA methylation. A, structure of the human CDKN1A gene promoter. The arrows indicate the locations of the qChIP-PCR primer binding sites. B, qChIP assays showing PLZF-RARα binding at the endogenous CDKN1A proximal promoter using an antibody against RARα. Cells were transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector and immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-RARα antibody. IgG, control ChIP antibody. C and D, qChIP-PCR assays showing histone modifications at the endogenous CDKN1A proximal promoter. Cells were transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector and lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies (IgG, Ac-H3, Ac-H4, H3K4-Me3, or H3K9-Me3). E, Me-DIP (methylated DNA ChIP) assays showing increased DNA methylation at the endogenous CDKN1A proximal promoter following ectopic PLZF-RARα expression. HEK293 cells were transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector, lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the antibody recognizing methylated DNA, and precipitated DNA was amplified using the primers indicated in A. F, bisulfite sequencing analysis of the methylated CDKN1A promoter. The proximal promoter sequences of CDKN1A, with potentially methylated CpG sites are shown in gray ovals, and the Sp1 binding GC-boxes shown above. Open ovals, unmethylated CpG; filled ovals, methylated CpG. G, co-immunoprecipitation of PLZF-RARα, MBD3, NuRD (MTA2), DNMT1, DNMT3b, and HP1. Cell lysates from either HEK293 cells transfected with a pcDNA3 vector or a PLZF-RARα expression vector were immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-PLZF, anti-RARα or anti-IgG antibodies and analyzed by Western blot (WB) with the indicated antibodies. H, qChIP assays showing the proximal promoter binding of PLZF-RARα, MBD3, the NuRD-HDAC3 complex, DNMT1/3b and HP1 proteins in HEK293 cells transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector. *, p < 0.05; N.S., not significant; t test.

These data imply the involvement of HDACs, DNMTs, and promoter DNA methylation in the transcriptional repression of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα. Accordingly, we investigated whether the CDKN1A promoter region can be methylated by Me-DIP (methylated DNA immunoprecipitation) assays. Ectopic PLZF-RARα increased methylation of the CDKN1A promoter region, as in the positive control AlphaX1 promoter, indicating that PLZF-RARα may repress transcription of CDKN1A through DNA methylation at the 15 CpGs of the proximal promoter region (bp, −139 to +30) (Fig. 8E). In control cells transfected with the pcDNA3 control construct, methylated bisulfite DNA sequencing showed that although some of the CpGs were methylated, only 1 of 20 CDKN1A promoter DNA strands sequenced was strongly methylated (13 of 15 CpGs), and only 2–3 moderately methylated promoter DNA strands were detected. In particular, the core CpG of Sp1 binding site-3, which is critical for transcriptional activation of CDKN1A, was methylated in 50% of the promoter DNA strands sequenced (17). In contrast, PLZF-RARα dramatically increased methylation at the CpG island of the CDKN1A proximal promoter, with virtually 70% (14 of 20) of the promoter DNA strands sequenced exhibiting extensively methylated CpGs (Fig. 8F). Interestingly, all of the core CpGs of the six Sp1 binding GC-boxes were heavily methylated, which may inhibit promoter DNA binding and transcriptional regulation by Sp1 family and other Krüppel-like transcription factors.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis of either HEK293 cells or HEK293 cells transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector revealed that PLZF-RARα interacts with MBD3, the Mi-2·NuRD-HDAC3 complex, and the NuRD complex-associated DNMTs and HP1 (Fig. 8G). ChIP analysis also showed that ectopic PLZF-RARα significantly increased the binding of MBD3, Mi-2·NuRD-HDAC3 complex (as monitored by diagnostic subunit MTA2), DNMT1/3b, and HP1 to the CDKN1A proximal promoter (Fig. 8H). PLZF-RARα, by interacting with MBD3, recruits the Mi-2·NuRD-HDAC3 complex and the complex-associated DNMT1/3b and HP1, likely resulting in CDKN1A promoter DNA methylation. Together, these results suggest that the CDKN1A promoter may be epigenetically silenced by histone deacetylation and DNA methylation.

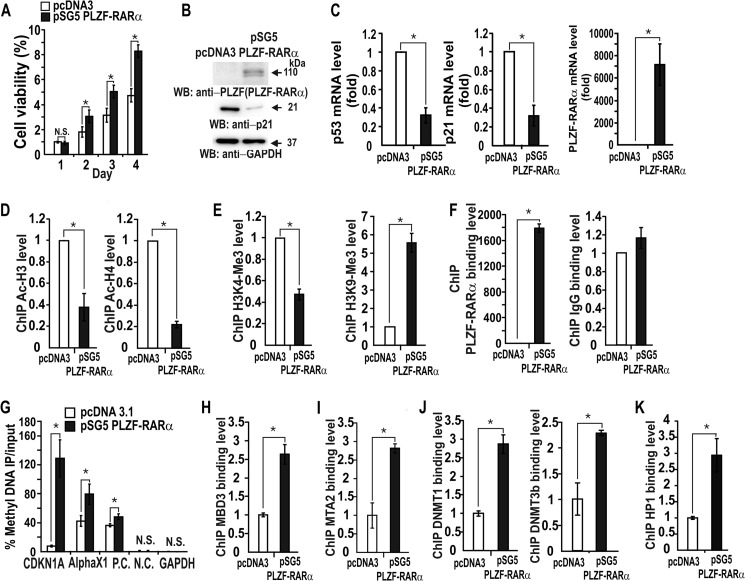

PLZF-RARα Stimulates Cell Proliferation and Represses CDKN1A Transcription in HL-60 Leukemia Cells through the Competitive Binding of p53, RARα, and Sp1, Histone Modifications, and DNA Methylation

We showed the molecular mechanism underlying the oncogenic properties of PLZF-RARα in HEK293 and HCT116 cells, and eventually tried to validate our findings in acute promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. PLZF-RARα promoted cell proliferation of human HL-60 cells and repressed CDKN1A and TP53 expression (Fig. 9, A–C). ChIP assays also showed that ectopic PLZF-RARα decreased acetylation of histones H3 and H4 at the CDKN1A proximal promoter by 40–65% and increased or decreased histone methylation markers of repression (H3K9-Me3) or activation (H3K4-Me3), respectively (Fig. 9, D–F). Furthermore, Me-DIP assays showed that ectopic PLZF-RARα expression increased DNA methylation of the CDKN1A proximal promoter (Fig. 9G). These data imply that, as in HEK293 cells, PLZF-RARα represses CDKN1A transcription by HDAC and promoter DNA methylation in HL-60 cells.

FIGURE 9.

PLZF-RARα stimulates cell proliferation and represses CDKN1A transcription in HL-60 cells through inhibitory histone modifications and DNA methylation. A, MTT assay of cell proliferation. HL-60 cells transfected with either pcDNA3 or pSG5-PLZF-RARα plasmid were grown for 1–4 days and analyzed for MTT to formazan conversion using colorimetry at 540–600 nm. B and C, Western blot (WB) and RT-qPCR analysis of protein and mRNA levels of the HL-60 cells transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector or a control plasmid. D–F, qChIP assays of modified histones Ac-H3, Ac-H4, H3K4-Me3, H3K9-Me3, and PLZF-RARα binding at the proximal CDKN1A promoter. HL-60 cells were transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector and analyzed for changes in Ac-H3, Ac-H4, H3K4-Me3, and H3K9-Me3 levels at the indicated regions (Fig. 8A) using the indicated antibodies. G, Me-DIP assays to assess DNA methylation of the endogenous CDKN1A proximal promoter in HL-60 cells transfected with PLZF-RARα expression vector. Alpha X1, positive control. H–K, qChIP assays of MBD3, NuRD (MTA2), DNMT1 and -3b, and HP1 binding at the proximal CDKN1A promoter in HL-60 cells transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector. *, p < 0.05; N.C., negative control; P.C., positive control; N.S., not significant; t test.

ChIP assays of HL-60 cells transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector further revealed that ectopic PLZF-RARα increased binding of MBD3, the Mi-2·NuRD-HDAC3 complex (as monitored by MTA2 binding), DNMT1/3b, and HP1 to the CDKN1A promoter (Fig. 9, H–K). These results suggest that PLZF-RARα may repress CDKN1A expression epigenetically by histone deacetylation and/or methylation by recruiting the MBD3-Mi-2·NuRD-HDAC3 complex and its associated DNMT1/3b and HP1. These results show the molecular mechanisms we identified in HEK293 cells are also applicable to HL-60 human leukemia cells.

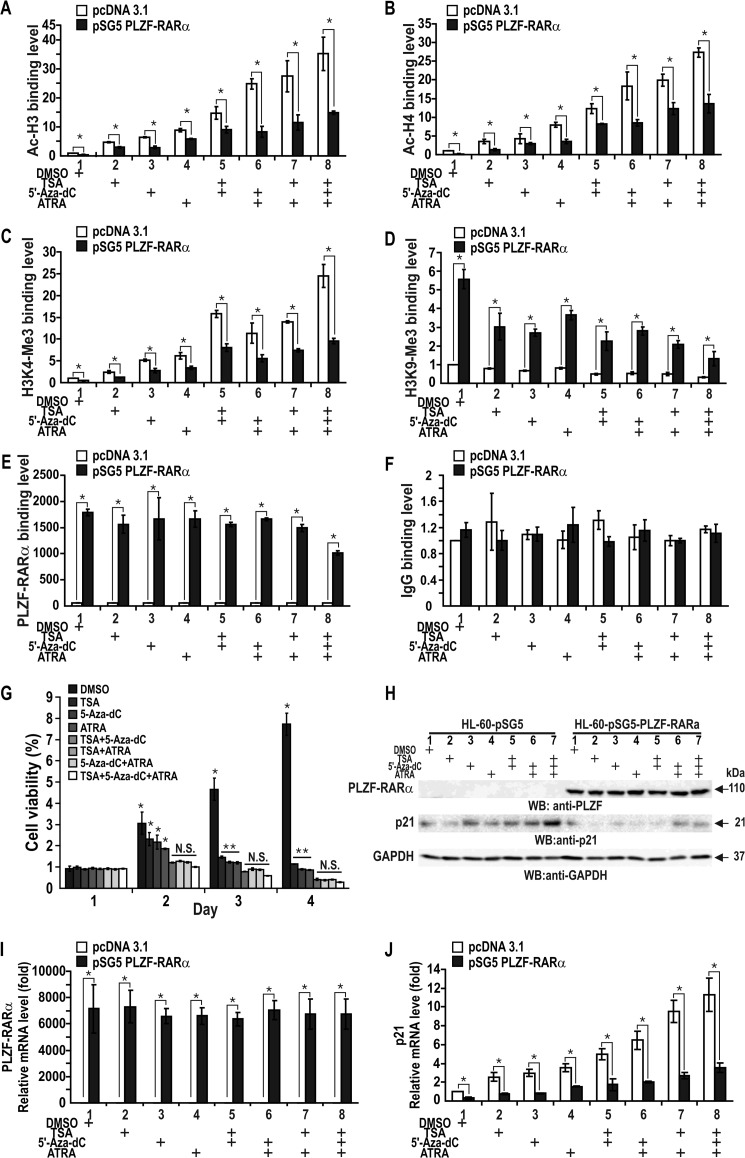

Epigenetic Repression of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα in HL-60 Cells Can Be Partially Reversed by the HDAC Inhibitor TSA, the DNMT Inhibitor 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine, ATRA or Any Combination of these Three Drugs

PLZF-RARα can repress CDKN1A expression in HL-60 cells through epigenetic mechanisms that include histone deacetylation and promoter DNA methylation. Ectopic PLZF-RARα repressed CDKN1A through the deacetylation of histones H3 and H4 (Fig. 10, A and B). The ChIP data on markers of transcriptional activation and repression indicated that treating the cells with epigenetic derepressive agents (TSA and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) combined with the RARα ligand ATRA did not completely derepress CDKN1A transcription to the level found in control cells (Fig. 10, H and J). Treating the cells with any of these agents alone or in combination did not affect PLZF-RARα (as judged by ChIP using an anti-PLZF antibody) binding or the control ChIP reactions (Fig. 9E). These results indicate that, of the several transcriptional repression mechanisms described above, CDKN1A transcriptional repression by the competitive binding of p53, PLZF-RARα, and Sp1 is quite significant. Because binding competition between these transcription factors is not likely affected by TSA and ATRA, the finding may explain why some APL patients with PLZF-RARα translocation are resistant to TSA and ATRA combination therapy and relapse.

FIGURE 10.

Proliferation of HL-60 cells is increased by ectopic PLZF-RARα and decreased by TSA, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, ATRA, or any combination thereof. Transcriptional repression of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα is derepressed by the reagents. A–D, qChIP assays of histone modifications at the endogenous CDKN1A gene proximal promoter using antibodies against IgG, Ac-H3, Ac-H4, H3K4-Me3, and H3K9-Me3. Cells were transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector and the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. E and F, qChIP-PCR assays of PLZF-RARα binding at the endogenous CDKN1A proximal promoter. Cells were transfected with a PLZF-RARα expression vector and the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PLZF antibody. Control ChIP assays using IgG are shown at the right (F). G, MTT assay of HL-60 cell proliferation. The cells were transfected with the pSG5-PLZF-RARα plasmid, treated with 200 nm TSA, 4 μm 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, 2 μm ATRA for 12 h or any combination thereof, grown 1–4 days, and analyzed for the MTT to formazan conversion using colorimetry at 540–600 nm. H, Western blot (WB) analysis of ectopic PLZF-RARα expression in HL-60 cells treated with various combinations of reagents. I and J, RT-qPCR analysis of PLZF-RARα and p21 mRNA. HL-60 cells transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector were further treated with the reagents and analyzed for expression of ectopic PLZF-RARα and endogenous p21 mRNA. *, p < 0.05; N.S., not significant; t test.

Although ATRA supplemented with the HDAC inhibitor TSA is effective in leukemia treatment, the addition of a DNMT inhibitor such as 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine appears to be more effective in inhibiting the proliferation of HL-60 cells transfected with the PLZF-RARα expression vector (Fig. 10G). Because CDKN1A transcriptional repression caused by the competitive binding of p53, PLZF-RARα, RARα, and Sp1 and PLZF-RARα-mediated down-regulation of CDKN1A expression by PLZF-RARα (Fig. 10, H–J) persists in leukemic cells expressing the PLZF-RARα oncoprotein, a certain population of leukemic cells may still remain resistant to the three drug combination therapies. Accordingly, the fundamental goal for better treating RA-resistant APL leukemic patients may be to inactivate PLZF-RARα activity or block the expression of the fusion protein.

DISCUSSION

In APL-resistant ATRA treatment, the PLZF gene is fused with the RARα gene by chromosomal translocation (1, 2, 4). PLZF-RARα was presumed to antagonize the function of RARα by interfering with promyeloctye differentiation or/and disrupting myeloid-specific PLZF functions. PLZF-RARα promotes proliferation of promyelocytes (immature granulocytes) through the aberrant regulation of cell cycle-associated genes such as MYC (1–3, 32). However, the target genes and the mechanism by which the PLZF-RARα oncoprotein stimulates cell proliferation and blocks myeloid differentiation has remained largely unknown.

PLZF-RARα interacts with co-repressor·HDAC complexes such as NCoR/SMRT and Sin3A. PLZF-RARα contains two co-repressor binding sites, the CoR box of RARα and the POZ domain of PLZF. Retinoic acid releases HDAC complexes from the CoR box of PLZF-RARα, but not from the POZ domain, which accounts for the molecular basis of RA resistance in PLZF-RARα-type APL patients. Previously, an artificial minimal promoter system with a RARE was used to demonstrate that the histone deacetylase inhibitors TSA and ATRA can lift the transcriptional repression by PLZF-RARα and synergistically activate reporter gene expression in CV-1, NB4, and U937 cells (5, 33). That study provided a basis for the effective growth suppression of ATRA-resistant leukemic cells by HDAC inhibitors and ATRA (5). Although genome-wide PLZF-RARα target genes were characterized by ChIP-on-ChIP in lymphoma U937 cells (34), the true targets of PLZF-RARα that play important roles in cell proliferation, and the molecular mechanisms of PLZF-RARα actions on these targets, remain largely unknown.

One of the key regulators of the cell cycle is p21. The CDKN1A gene encoding p21 was previously reported to be a direct target of RARα (15). Our investigation revealed that PLZF-RARα represses CDKN1A expression potently to stimulate cell proliferation. PLZF-RARα also represses expression of another key regulator of the cell cycle, p53. Our investigation of the molecular mechanism of CDKN1A transcriptional regulation by PLZF-RARα revealed several important novel features of the oncoprotein PLZF-RARα. These include CDKN1A repression through competitive binding of transcription factors (p53, Sp1, RARα, and PLZF-RARα), transcriptional repression of TP53, degradation of p53 by ubiquitination, and CDKN1A promoter histone deacetylation and DNA methylation. Moreover, the DNA binding specificity of PLZF-RARα is rather promiscuous and is not limited to the RARE. PLZF-RARα also binds to two distal p53 binding elements and proximal GC-boxes (thus competing with Sp1 for GC-box binding). These binding activities of PLZF-RARα could potentially block both the constitutive and inducible expression of CDKN1A.

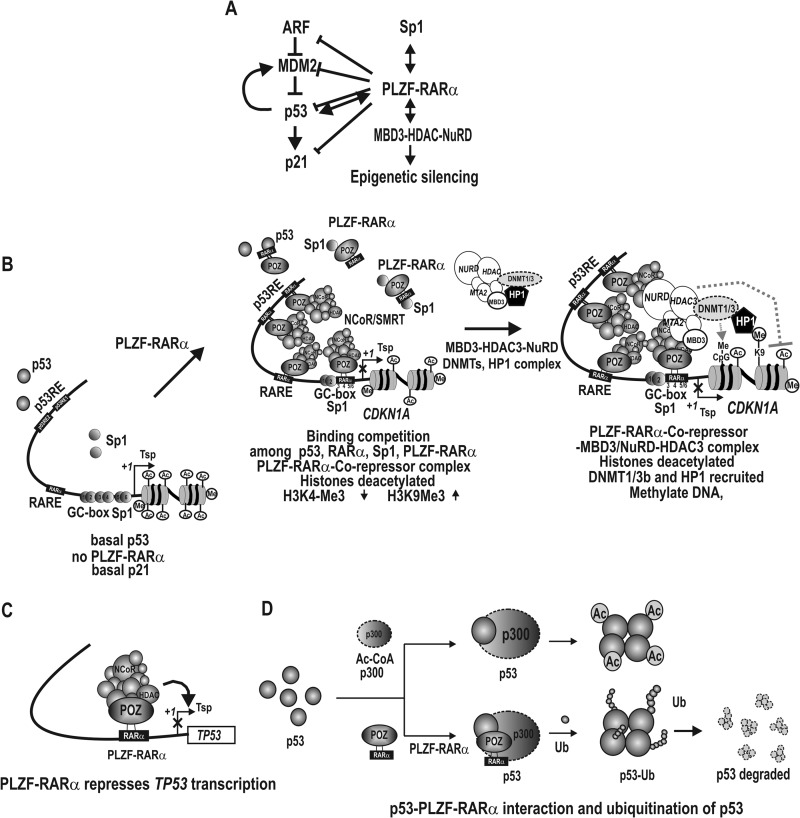

Consequently, we propose a hypothetical model for the transcriptional regulation of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα (Fig. 11). Under normal cellular conditions in which p53 levels are low and no PLZF-RARα is present, p21 is expressed at a low level and cells proliferate normally. When cells are challenged with genotoxic stress, however, the tumor suppressor p53 is markedly induced and activates CDKN1A transcription by interacting with its p53REs and Sp1 bound at the Sp1-binding GC-box 3. The induced p21 protein then stops progression of the cell cycle and allows the cells to either repair DNA damage or undergo apoptosis. When cells express PLZF-RARα following chromosomal translocation, PLZF-RARα represses CDKN1A transcription by binding to proximal GC-boxes 3, 4, and 5/6, RARE, and the distal p53 binding elements of the CDKN1A promoter (Fig. 11B). Thus, transcriptional activation by p53, RARα, and Sp1 can be effectively blocked by PLZF-RARα at their respective binding elements. Even when cells are under genotoxic stress, p53 and Sp1 cannot activate transcription due to PLZF-RARα competitive binding to both the proximal GC boxes and distal p53REs that are critical for basal transcription and synergistic transcriptional activation by Sp1 and p53, leading to the accumulation of DNA damage and increased cell proliferation.

FIGURE 11.

Hypothetical model for transcriptional regulation of CDKN1A and TP53 by PLZF-RARα and post-translational ubiquitination of p53. A, PLZF-RARα represses all four genes in the p53 pathway. ⊢, transcriptional repression; ↔, protein-protein interaction. B, hypothetical model for transcriptional repression of the CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα. In the absence of PLZF-RARα, the CDKN1A gene is transcribed at a basal level, primarily by Sp1 family transcription factors. In PLZF-RARα type leukemic cells, however, PLZF-RARα represses CDKN1A transcription by binding to its two distal promoter p53-binding elements, a RARE, and the proximal GC-boxes 3, 4, and 5/6. Binding to these elements involves competition with p53, RARα/RXR, and Sp1 at their respective binding sites. PLZF-RARα recruits co-repressor·HDAC complexes, deacetylates histones, and increases the level of H3K9-Me3. PLZF-RARα also interacts with the MBD3·NuRD/HDAC3 complex, which also modifies histone acetylation and methylation to reflect a repressed state. The MBD3·NuRD complex also contains DNMT1/3 and can methylate the CDKN1A promoter DNA. Because the MBD3·NuRD complex contains HDAC3 and DNMTs, it is not certain whether histone deacetylation and DNA methylation occurs simultaneously or sequentially. Presence of HP1 at the promoter region indicates heterochromatin formation. Tsp(+1), transcription start site. ZF, zinc finger DNA binding domain. X, transcriptional repression. C, transcriptional repression of the TP53 gene by PLZF-RARα and the corepressor·HDAC complex. D, post-translational ubiquitination of p53 by PLZF-RARα. Although acetylation of p53 by p300 increases p53 activity or stability, ubiquitination of p53 decreases p53 protein stability.

Furthermore, PLZF-RARα potently represses transcription of TP53 and decreases p53 stability by inhibiting p53 acetylation and increasing p53 ubiquitination. p53 is an upstream transcriptional activator of CDKN1A. PLZF-RARα blocks the induction of CDKN1A by repressing the expression of de novo p53 and promoting the degradation of p53 through decreased p53 acetylation and increased p53 ubiquitination (Figs. 5, B, G, I, and J; and 11, C and D). PLZF-RARα significantly affects not only the transcription of CDKN1A, but may also affect other p53 and RARα target genes important for apoptosis, differentiation, cell cycle regulation, etc.

However, the transcriptional repression of CDKN1A mediated by PLZF-RARα appears to be more complex than the repression by competitive binding among transcription factors and HDAC activity, and additionally involves epigenetic silencing by histone deacetylation and DNA methylation. Interestingly, the methylated DNA-binding protein MBD3, which is one of the subunits of the Mi-2·NuRD-HDAC3 complex, was found to be associated with the proximal promoter of CDNK1A (35). PLZF-RARα interacts with MBD3 and recruits the Mi-2·NuRD-HDAC3 complex and the NuRD-associated DNMT1/3b and HP1, which eventually leads to CDKN1A promoter DNA methylation.

Using HEK293 and HCT116 cells, we were able to consistently show that PLZF-RARα has proto-oncoprotein characteristics with the capacity to transform cells and stimulate cell proliferation by repressing CDKN1A expression. However, one might argue that the molecular mechanism of transcriptional regulation of CDKN1A by PLZF-RARα revealed in HEK293 and HCT116 cells might not be true in leukemic cells, which is often true depending on the transcription factors and cellular contexts. We were able to demonstrate that PLZF-RARα also represses transcription of CDKN1A in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells.

The PML-RARα fusion protein has an abnormally high affinity for corepressors, and the protein switches to an activator by releasing corepressors at pharmacological doses of ATRA (5, 36). However, the PLZF-RARα fusion protein is ATRA-resistant and does not release corepressors. Previously, HDAC inhibitors such as TSA and butyrate were shown to block PLZF-RARα-mediated repression of reporter genes (5), and the combination of ATRA and the HDAC inhibitor suberoyl anilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) was reported to be sufficient for clearing leukemic blasts from the peripheral blood of mice harboring PLZF-RARα (12). Our study suggests that DNMT inhibitors such as 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in combination with ATRA and HDAC inhibitors may be more effective in derepression of the PLZF-RARα target genes involved in cell differentiation, cell proliferation, and oncogenesis. Thus, PLZF-RARα-type APL patients may be more effectively treated by the addition of DNMT inhibitors to the ATRA plus HDAC inhibitor regimen. However, because the repression of CDKN1A is, in part, due to competitive binding between p53, PLZF-RARα, RARα, and Sp1, and the fact that transcription repression of TP53 by PLZF-RARα persists in leukemic cells with PLZF-RARα, a certain population of leukemic cells may still remain resistant to the above described three drug combination therapy. Thus, an improved treatment of ATRA-resistant APL patients could be to inactivate PLZF-RARα activity or block the expression of the fusion protein.

This work was supported by Grant 00001561 (to M.-W. H.) from the National R & D Program for Cancer Control, Korean Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family affairs and DOYAK Research Grant 2011-0028817 (to M.-W. H.) from the Korea Research Foundation of the Korea Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

- APL

- acute promyelocytic leukemia

- ARF

- alternative reading frame gene

- ATRA

- all-trans-retinoic acid

- CDKN1A

- cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor-1A

- DNMT

- DNA methyltransferase

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- HP1

- heterochromatin protein-1

- Luc

- luciferase gene

- MBD3

- methyl-CpG binding domain protein-3

- MDM2

- human analogue of mouse double minute oncogene

- Me-DIP

- methylated DNA immunoprecipitation

- MTA2

- metastasis-associated protein 2

- NCoR

- nuclear receptor corepressor

- p53REs

- p53 response elements

- PLZF

- promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein

- PVDF

- polyvinylidine difluoride

- RARα

- retinoic acid receptor-α

- RARE

- retinoic acid response element

- RXR

- retinoid × receptor

- SMRT

- silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptors

- Sp1

- specificity protein 1

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- POZ

- poxvirus and zinc finger

- NuRD

- nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase

- ATRA

- all-trans-retinoic acid

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Warrell R. P., Jr., de Thé H., Wang Z. Y., Degos L. (1993) Acute promyelocytic leukaemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 329, 177–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Z., Guidez F., Rousselot P., Agadir A., Chen S. J., Wang Z. Y., Degos L., Zelent A., Waxman S., Chomienne C. (1994) PLZF-RARα fusion proteins generated from the variant t(11;17)(q23;q21) translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia inhibit ligand-dependent transactivation of wild-type retinoic acid receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 1178–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Licht J. D., Shaknovich R., English M. A., Melnick A., Li J. Y., Reddy J. C., Dong S., Chen S. J., Zelent A., Waxman S. (1996) Reduced and altered DNA-binding and transcriptional properties of the PLZF-retinoic acid receptor-α chimera generated in t(11;17)-associated acute promyelocytic leukemia. Oncogene 12, 323–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen Z., Brand N. J., Chen A., Chen S. J., Tong J. H., Wang Z. Y., Waxman S., Zelent A. (1993) Fusion between a novel Krüppel-like zinc finger gene and the retinoic acid receptor-α locus due to a variant t(11;17) translocation associated with acute promyelocytic leukaemia. EMBO J. 12, 1161–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin R. J., Nagy L., Inoue S., Shao W., Miller W. H., Jr., Evans R. M. (1998) Role of the histone deacetylase complex in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature 391, 811–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He L. Z., Guidez F., Tribioli C., Peruzzi D., Ruthardt M., Zelent A., Pandolfi P. P. (1998) Distinct interactions of PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα with co-repressors determine differential responses to RA in APL. Nat. Genet. 18, 126–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hong S. H., David G., Wong C. W., Dejean A., Privalsky M. L. (1997) SMRT corepressor interacts with PLZF and with the PML-retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) and PLZF-RARα oncoproteins associated with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 9028–9033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin R. J., Sternsdorf T., Tini M., Evans R. M. (2001) Transcriptional regulation in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Oncogene 20, 7204–7215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Warrell R. P., Jr., He L. Z., Richon V., Calleja E., Pandolfi P. P. (1998) Therapeutic targeting of transcription in acute promyelocytic leukemia by use of an inhibitor of histone deacetylase. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 1621–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaknovich R., Yeyati P. L., Ivins S., Melnick A., Lempert C., Waxman S., Zelent A., Licht J. D. (1998) The promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein affects myeloid cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 5533–5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heinzel T., Lavinsky R. M., Mullen T. M., Söderstrom M., Laherty C. D., Torchia J., Yang W. M., Brard G., Ngo S. D., Davie J. R., Seto E., Eisenman R. N., Rose D. W., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (1997) A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387, 43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He L. Z., Tolentino T., Grayson P., Zhong S., Warrell R. P., Jr., Rifkind R. A., Marks P. A., Richon V. M., Pandolfi P. P. (2001) Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce remission in transgenic models of therapy-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1321–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harper J. W., Adami G. R., Wei N., Keyomarsi K., Elledge S. J. (1993) The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell 75, 805–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. el-Deiry W. S., Tokino T., Velculescu V. E., Levy D. B., Parsons R., Trent J. M., Lin D., Mercer W. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1993) WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gartel A. L., Radhakrishnan S. K. (2005) Lost in transcription: p21 repression, mechanisms, and consequences. Cancer Res. 65, 3980–3985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seoane J., Le H. V., Massagué J. (2002) Myc suppression of the p21Cip1 Cdk inhibitor influences the outcome of the p53 response to DNA damage. Nature 419, 729–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koutsodontis G., Tentes I., Papakosta P., Moustakas A., Kardassis D. (2001) Sp1 plays a critical role in the transcriptional activation of the human cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/Cip1 gene by the p53 tumor suppressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29116–29125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gartel A. L., Ye X., Goufman E., Shianov P., Hay N., Najmabadi F., Tyner A. L. (2001) Myc represses the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter and interacts with Sp1/Sp3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4510–4515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kardassis D., Papakosta P., Pardali K., Moustakas A. (1999) c-Jun transactivates the promoter of the human p21WAF1/Cip1 gene by acting as a superactivator of the ubiquitous transcription factor Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29572–29581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maeda T., Merghoub T., Hobbs R. M., Dong L., Maeda M., Zakrzewski J., van den Brink M. R., Zelent A., Shigematsu H., Akashi K., Teruya-Feldstein J., Cattoretti G., Pandolfi P. P. (2007) Regulation of B versus T lymphoid lineage fate decision by the proto-oncogene LRF. Science 316, 860–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Phan R. T., Dalla-Favera R. (2004) The BCL6 proto-oncogene suppresses p53 expression in germinal-centre B cells. Nature 432, 635–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi W. I., Jeon B. N., Park H., Yoo J. Y., Kim Y. S., Koh D. I., Kim M. H., Kim Y. R., Lee C. E., Kim K. S., Osborne T. F., Hur M. W. (2008) Proto-oncogene FBI-1 (Pokemon) and SREBP-1 synergistically activate transcription of fatty-acid synthase gene (FASN). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29341–29354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choi W. I., Jeon B. N., Yun C. O., Kim P. H., Kim S. E., Choi K. Y., Kim S. H., Hur M. W. (2009) Proto-oncogene FBI-1 represses transcription of p21CIP1 by inhibition of transcription activation by p53 and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12633–12644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi W. I., Kim Y., Kim Y., Yu M. Y., Park J., Lee C. E., Jeon B. N., Koh D. I., Hur M. W. (2009) Eukaryotic translation initiator protein 1A isoform, CCS-3, enhances the transcriptional repression of p21CIP1 by proto-oncogene FBI-1 (Pokemon/ZBTB7A). Cell Physiol. Biochem. 23, 359–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crook J. M., Dunn N. R., Colman A. (2006) Repressed by a NuRD. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 212–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wade P. A. (2001) Methyl CpG-binding proteins and transcriptional rep ression. BioEssays 23, 1131–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Noh E. J., Jang E. R., Jeong G., Lee Y. M., Min C. K., Lee J. S. (2005) Methyl CpG-binding domain protein 3 mediates cancer-selective cytotoxicity by histone deacetylase inhibitors via differential transcriptional reprogramming in lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65, 11400–11410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reese K. J., Lin S., Verona R. I., Schultz R. M., (2007) Bartolomei MS. Maintenance of paternal methylation and repression of the imprinted H19 gene requires MBD3. PLoS Genet. 3, e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kelly K. F., Daniel J. M. (2006) POZ for effect: POZ-ZF transcription factors in cancer and development. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 578–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mangelsdorf D. J., Ong E. S., Dyck J. A., Evans R. M. (1990) Nuclear receptor that identifies a novel retinoic acid response pathway. Nature 345, 224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grignani F., De Matteis S., Nervi C., Tomassoni L., Gelmetti V., Cioce M., Fanelli M., Ruthardt M., Ferrara F. F., Zamir I., Seiser C., Grignani F., Lazar M. A., Minucci S., Pelicci P. G. (1998) Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-α recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature 391, 815–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rice K. L., Hormaeche I., Doulatov S., Flatow J. M., Grimwade D., Mills K. I., Leiva M., Ablain J., Ambardekar C., McConnell M. J., Dick J. E., Licht J. D. (2009) Comprehensive genomic screens identify a role for PLZF-RARα as a positive regulator of cell proliferation via direct regulation of c-MYC. Blood 114, 5499–5511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Villa R., Morey L., Raker V. A., Buschbeck M., Gutierrez A., De Santis F., Corsaro M., Varas F., Bossi D., Minucci S., Pelicci P. G., Di Croce L. (2006) The methyl-CpG binding protein MBD1 is required for PML-RARα function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1400–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spicuglia S., Vincent-Fabert C., Benoukraf T., Tibéri G., Saurin A. J., Zacarias-Cabeza J., Grimwade D., Mills K., Calmels B., Bertucci F., Sieweke M., Ferrier P., Duprez E. (2011) Characterisation of genome-wide PLZF/RARA target genes. PLoS One 6, e24176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Choi W. I., Jeon B. N., Yoon J. H., Koh D. I., Kim M. H., Yu M. Y., Lee K. M., Kim Y., Kim K., Hur S. S., Lee C. E., Kim K. S., Hur M. W. (2013) The proto-oncoprotein FBI-1 interacts with MBD3 to recruit the Mi-2/NuRD-HDAC complex and BCoR and to silence p21WAF/CDKN1A by DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 6403–6420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Villa R., Pasini D., Gutierrez A., Morey L., Occhionorelli M., Viré E., Nomdedeu J. F., Jenuwein T., Pelicci P. G., Minucci S., Fuks F., Helin K., Di Croce L. (2007) Role of the polycomb repressive complex 2 in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell 11, 513–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]