Background: Collagen cross-linking mechanisms must be regulated to obtain tissue-specific collagen fiber properties.

Results: Deficiency in collagen-associated protein fibromodulin leads to excessively cross-linked specific domain of collagen.

Conclusion: Fibromodulin modulates site-specific cross-linking of collagen.

Significance: This is the first report showing that a collagen-associated protein can modulate cross-linking of specific collagen domains.

Keywords: Collagen, Connective Tissue, Lysyl Oxidase, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Tendon, SLRP, Cross-links, Fibromodulin, Small Leucine-rich Protein

Abstract

The controlled assembly of collagen monomers into fibrils, with accompanying intermolecular cross-linking by lysyl oxidase-mediated bonds, is vital to the structural and mechanical integrity of connective tissues. This process is influenced by collagen-associated proteins, including small leucine-rich proteins (SLRPs), but the regulatory mechanisms are not well understood. Deficiency in fibromodulin, an SLRP, causes abnormal collagen fibril ultrastructure and decreased mechanical strength in mouse tendons. In this study, fibromodulin deficiency rendered tendon collagen more resistant to nonproteolytic extraction. The collagen had an increased and altered cross-linking pattern at an early stage of fibril formation. Collagen extracts contained a higher proportion of stably cross-linked α1(I) chains as a result of their C-telopeptide lysines being more completely oxidized to aldehydes. The findings suggest that fibromodulin selectively affects the extent and pattern of lysyl oxidase-mediated collagen cross-linking by sterically hindering access of the enzyme to telopeptides, presumably through binding to the collagen. Such activity implies a broader role for SLRP family members in regulating collagen cross-linking placement and quantity.

Introduction

Collagen fibrils are essential for the material strength of animal tissues. Their properties vary dependent on the content and quality of covalent intermolecular cross-links formed as a result of lysyl oxidase activity. The cross-links form progressively as fibrils grow. Lysyl oxidase deaminates specific telopeptide lysine and hydroxylysine residues, creating reactive aldehydes that initiate covalent bonds with lysines or hydroxylysines at specific sites on neighboring collagen monomers (1). Tissue-specific variations in cross-linking chemistry and bond placement are well documented (1–4). We suspect that such variations are influenced by collagen-associated small leucine-rich proteins (SLRPs).3 Because their expression patterns vary between tissues and at different developmental stages, SLRPs play a role in regulating the diversity in collagen fibril architecture (5). Clues on function come from SLRP knock-out mice, in which various tissues—depending on which SLRP is absent—display abnormal collagen fibrils. Thus, decorin-deficient mice have fragile skin, weak tendons, and lower lung airway resistance, all because of altered collagen fibril structure (6–8). Keratocan-deficient mice develop a flattened cornea, which is a phenocopy of human cornea plana caused by KERA gene mutations (9, 10). Biglycan deficiency causes an osteoporotic phenotype (11), and lumican-deficient mice have opaque corneas and fragile skin (12, 13). Lastly, fibromodulin-null mice have thinner and irregularly fused collagen fibrils in tendons (14) and develop osteoarthritis and weak ligaments (15). Absence of one SLRP, therefore, is not compensated by another, which supports the notion of their having specific functions during different stages of collagen fibrillogenesis.

Compound SLRP knock-out mice have more severe phenotypes. Lumican- and fibromodulin-deficient mice have joint laxity and very weak tendons with severely disrupted collagen fibrillogenesis (16, 17). Decorin- and biglycan-deficient mice corneas also contain severely misshaped collagen fibrils (18). This specificity may depend to some extent on known differences in SLRP binding sites to collagen. Fibromodulin has two collagen-binding domains: one shared by lumican and the other specific to fibromodulin. They can therefore compete for collagen binding, but fibromodulin has the stronger affinity, suggesting different roles during collagen fibrillogenesis (19–21). Not all SLRPs can compete with each other, as in the case of decorin being unable to inhibit fibromodulin binding (19, 22), but competing with asporin (23).

To date, several reports have shown that SLRPs can act during collagen fibrillogenesis in vitro, affecting the kinetics and resulting fibril thicknesses (24–28). Such systems are limited in the insights they can provide, however, because they lack cells, procollagen monomers, and continuous growth.

Here we studied the biochemical properties of collagen from fibromodulin-deficient Fmod−/− mouse tendons. The findings show that in the absence of fibromodulin, lysyl oxidase-mediated cross-linking of tendon type I collagen becomes deregulated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sequential Extraction and CNBr Digestion of Collagen

The method has been previously described (29). Briefly, collagen was sequentially extracted from the tail tendons of 5-month-old Fmod−/− and wild-type mice for 24 h each in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, then 0.5 m acetic acid, and finally pepsin (1 mg/ml) in 0.5 m acetic acid at 4 °C. Extracts were collected as supernatants after centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min, and pellets were carried over to the next extraction step. Collagen was analyzed by 8% Tris-glycine-reduced SDS-PAGE. All collagen band identities were verified by mass spectrometry. Collagen was quantified by hydroxyproline assay as described (30). For CNBr digests, whole tendons were resuspended in 70% formic acid with 1 mg/ml CNBr, degassed, and digested overnight. Digests were SpeedVac-dried for analysis by SDS-PAGE.

P13 Antiserum Preparation

The P13 rabbit anti-collagen IgG specifically recognizes α2(I)-collagen chains in immunoblotting.4 The IgG was purified by protein A-Sepharose from serum of rabbits immunized with a CNBr-digest of bovine α2(I)-collagen chains purified by CM-cellulose under denaturing conditions (29). The collagen type I was isolated from calf skin by pepsin cleavage in acetic acid (29).

Immunoblots

Acetic acid-extracted collagen was run on 4–20% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in TBS, incubated with P13 anti-serum at 1 μg/ml in 0.5% milk in TBST (TBS with 0.1% Tween 20), washed with TBST, incubated with anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated 1:1000 (Dako), washed with TBST, and developed using SuperSignal West Dura ECL kit (Pierce).

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measurements were performed with 0.5 mg/ml acetic acid-extracted collagen, with or without pepsin treatment, followed by precipitation by 0.7 m NaCl, redissolving in 0.5 m acetic acid, and dialysis against 0.2 m sodium phosphate, 0.5 m glycerol, pH 7.4 (glycerol prevents new collagen fibril formation). The DSC thermograms were recorded in VP-DSC (MicroCal) using temperature gradient from 25 to 70 °C, scan rate at 0.25 °C/min, and medium feedback. Each thermogram was corrected by subtraction of a linear baseline based on a blank buffer sample and normalized for collagen concentration.

Mass Spectrometry

Tail tendon tissue was digested with bacterial collagenase as described (3). Collagenase-generated peptides were separated by reverse phase HPLC (C8, Brownlee Aquapore RP-300, 4.6 mm × 25 cm) with a linear gradient of acetonitrile:n-propanol (3:1 v/v) in aqueous 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (2). Individual fractions were analyzed by LC-MS. Collagen chains were also directly extracted from tendon by heat denaturation (90 degrees C) in SDS sample buffer and run on SDS-6% PAGE. Collagen chains and CB peptides resolved by SDS-PAGE were cut out, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS. Peptides were resolved and analyzed by electrospray LC/MS using an LTQ XL ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with in-line liquid chromatography using a C4 5-μm capillary column (300 μm × 150 mm; Higgins Analytical RS-15M3-W045) eluted at 4.5 μl/min. The LC mobile phase consisted of buffer A (0.1% formic acid in MilliQ water) and buffer B (0.1% formic acid in 3:1 acetonitrile:n-propanol, v/v). An electrospray ionization source introduced the LC sample stream into the mass spectrometer with a spray voltage of 3 kV. Linear and cross-linked peptides were identified based on their known elution positions and MSMS fragmentation patterns (31).

Amino Acid Analysis

Acetic-acid extracted collagen was hydrolyzed in 6 m HCl, lyophilized, redissolved in water with EDTA, and derivatized with phenylisothiocyanate. Amino acids were then applied on a narrow bore HPLC system for separation on a reverse phase C18 silica column and detected for phenylthiocarbamyl chromophore at 254 nm.

Trypsin Sensitivity Assay

Acid-extracted tail tendon collagen from wild-type and Fmod−/−mice was dialyzed into 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, and incubated with trypsin at 1:100 (w/w) ratio. Aliquots of 5 μg of collagen were removed after 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min, and trypsin activity was quenched by SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Samples were run on 8% Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE and analyzed for the amount of proteolysis by Coomassie staining.

Procollagen Processing Assay

Smooth muscle cells were isolated from aorta of wild-type and Fmod−/− mice into α-minimal essential medium using collagenase. After reaching confluency, ascorbate was added at 50 μg/ml, and the cells were pulsed for 10 min with 2.5 μCi/ml of [14C]proline and chased from 0 to 2 h. Procollagen was acetone precipitated from cell culture medium, run on SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiography.

RESULTS

Fmod−/− Mouse Tendon Collagen Is Abnormally Cross-linked

To assess the overall cross-linking, collagen was serially extracted from dissected tail tendons. Although PBS extracts only trace amounts of collagen, the subsequent 0.5 m acetic acid extraction solubilizes molecules linked by acid-labile aldimine cross-links, and finally pepsin extraction cleaves collagen telopeptides and releases molecules polymerized by acid-stable cross-links (e.g. aldol; see “Discussion”). The results show that only 20% of total collagen could be extracted with PBS plus acetic acid from Fmod−/− mice, compared with 70% from wild-type mice. Thus, a large fraction of collagen in Fmod−/− mouse tendon required pepsin to extract it, whereas most collagen in wild-type tendon was solubilized by dilute acetic acid (Fig. 1A).

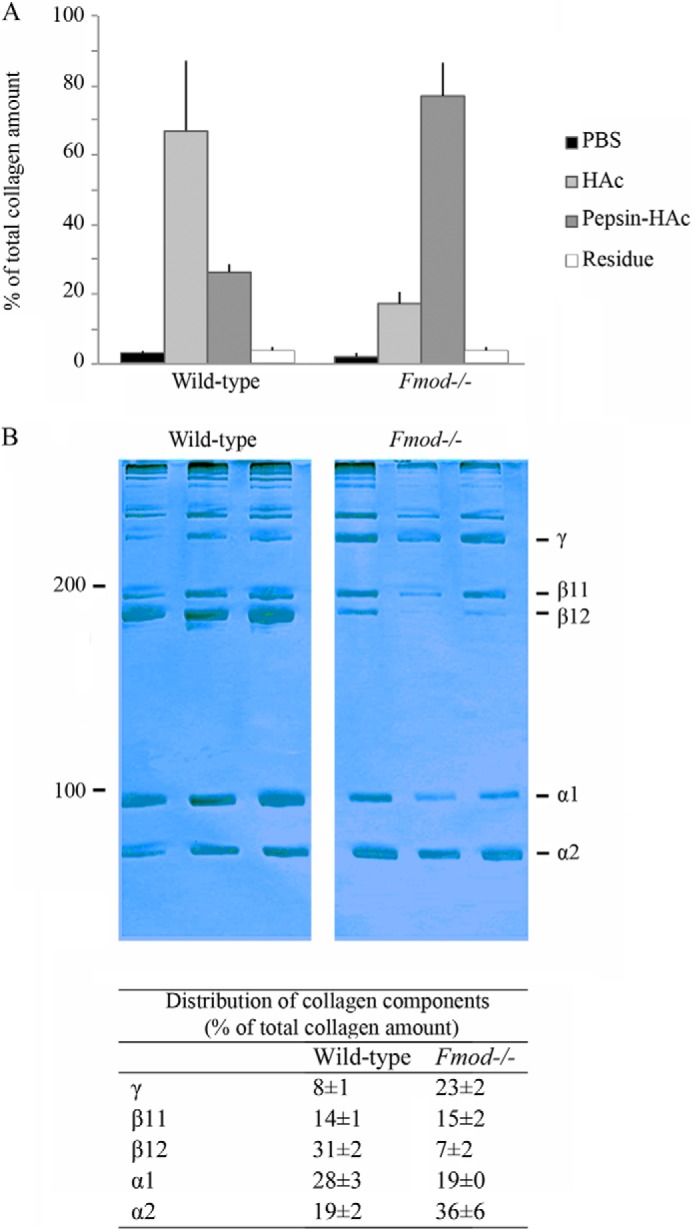

FIGURE 1.

Altered extractability and electrophoretic pattern of Fmod−/− tail tendon collagen. A, collagen yields on sequential extraction (PBS, 0.5 m acetic acid, and pepsin) of tail tendons from Fmod−/− and wild-type mice. Filled bars, wild-type mice (n = 5); open bars, Fmod−/− mice (n = 5). B, 8% SDS-PAGE of acetic acid-extracted collagen from wild-type (n = 3) and Fmod−/− (n = 3) mice stained with Coomassie Blue. Relative amounts of α-, β-, and γ-components of collagen were quantified with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) and are listed as percentages of total collagen ± S.D.

The acetic acid extracts were run on SDS-PAGE to assess the collagen cross-linking pattern. The α-, β-, and γ-components were quantified (Fig. 1B). Compared with wild-type, Fmod−/− extracts had a higher ratio of α2(I) to α1(I) chains, one-fourth the amount of the β12 dimer (β12), and three times the amount of the γ112 trimer. Analyses of tendons from more than 30 mice revealed that the α2(I) to α1(I) ratio could vary somewhat between mice; however, the overall trend of less β12 and more γ112 in Fmod−/− extracts was reproducible. This shift could also be seen on an immunoblot of the extracts using an antiserum specific for the α2(I) chain (Fig. 2, A and B). A CNBr digest of whole Fmod−/− tendon contained less of the linear non-cross-linked CB6 peptide than wild-type tendon (Fig. 2C). Peptide CB6 comes from the C-terminal sequence including the cross-linking C-telopeptide of the α1(I) chain. These data are consistent with a marked increase in stable cross-linking through the C-terminal telopeptide of the α1(I) chain in the Fmod−/− tendon collagen.

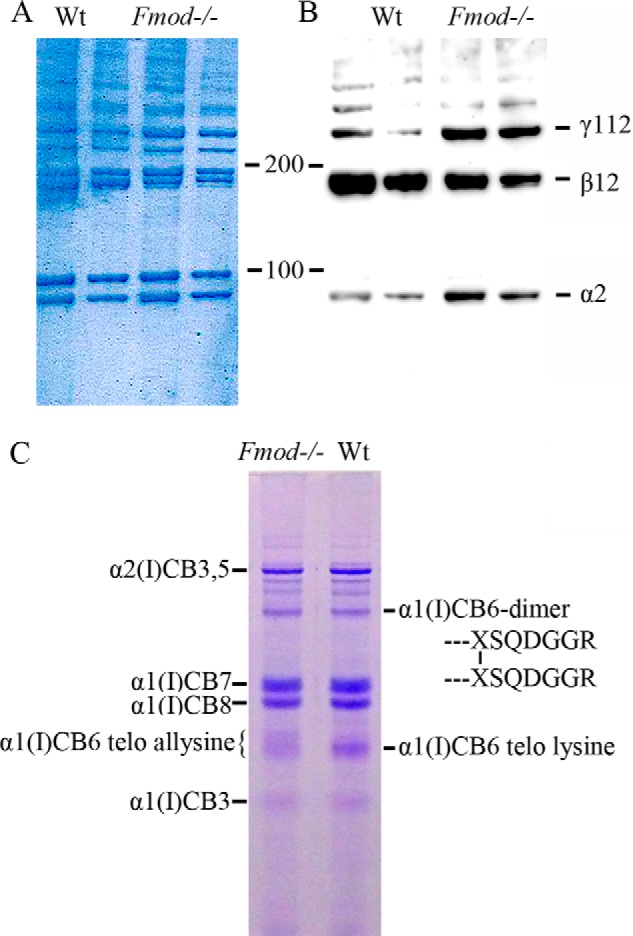

FIGURE 2.

Enhanced stable cross-linking of α1(I) chains. A and B, acid-extracted collagen was run on 4–20% SDS-PAGE gradient gels and either stained with Coomassie Blue (A) or transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and immunoblotted with an antiserum specific to the collagen α2(I) chain (B). C, whole tendons were digested with CNBr, and the resulting collagen fragments were resolved on 12.5% SDS-PAGE staining with Coomassie Blue. The indicated α1(I)CB6-containing monomer and dimer bands were identified by in-gel trypsin digestion and mass spectroscopy. The prominent α1(I)CB6 monomer from wild-type tendon gave a C-terminal tryptic peptide cleaved after its C-terminal unmodified lysine residue. From Fmod−/− tendon, this component was largely missing, and the retarded, broad α1(I)CB6 monomer band gave a C-terminal tryptic peptide cleaved at arginine, six residues more C-terminal. Sequences of the latter same two tryptic peptides are shown later in Fig. 4.

Fmod−/− Tendon Type I Collagen Has Increased α1(I) C-telopeptide Aldehyde Formation

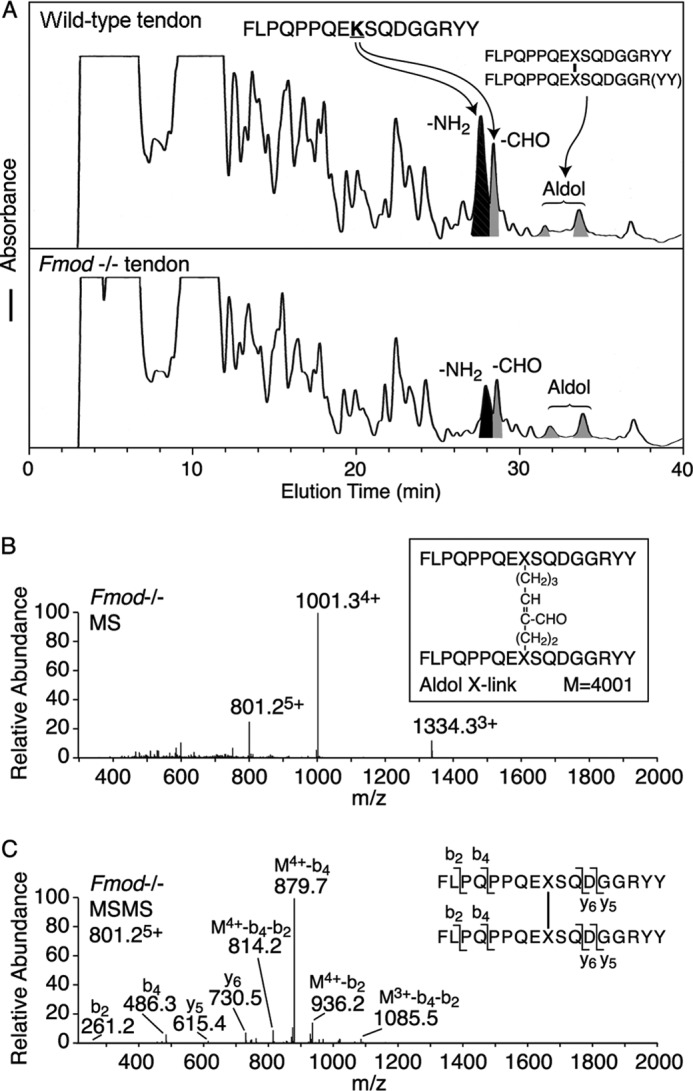

Type I collagen prepared by bacterial collagenase digestion of whole Fmod−/− tendons contained less α1(I) C-telopeptide with an unmodified lysine and more lysyl-oxidase-mediated aldehyde plus aldol dimer forms. In Fig. 3, the black peak indicates the C-telopeptide with an unmodified lysine. The gray peaks are the lysine aldehyde-containing linear C-telopeptide (−CHO) and two cleavage variants of the C-telopeptide dimer linked by an allysine aldol cross-link. The present study and other unpublished results5 indicate that the latter aldol is primarily intermolecular, whereas the well established N-telopeptide aldol dimer formed between N-telopeptides is intramolecular in origin (1). The bacterial collagenase digest also showed that only the lysine form of N-telopeptides and the α1(I) C-telopeptide were present in the collagen with little or no lysine hydroxylation in either Fmod−/− or wild-type tendon type I collagen. Cross-links therefore appeared to be formed exclusively on the lysine aldehyde pathway in both Fmod−/− and wild-type tail tendons (2).

FIGURE 3.

Mass spectrometric identification of the collagen type I C-telopeptide cross-linking domain. Bacterial collagenase-digested tendon collagen peptides from Fmod−/− and wild-type mice were resolved by HPLC (A) and identified by tandem mass spectrometry from their MSMS fragments (B and C). Consistently the ratio of unmodified lysine-containing C-telopeptide to aldehyde- plus aldol-containing C-telopeptides was approximately 2:1 from wild type compared with 1:2 from mutant tendon. The small peaks eluting from 25 to 27 min in wild-type tendon are amino and aldehyde versions of the C-telopeptide missing one or two Tyr residues from the C terminus. The structure of the aldol cross-link from Fmod−/− tendon was identified by MS (B) and MSMS fragmentation of the 801.25+ ion as shown (C). M4+-b4-b2 is a fragment of the parent ion with four charges that lost b2 from one arm and b4 from the other arm of the cross-linked structure.

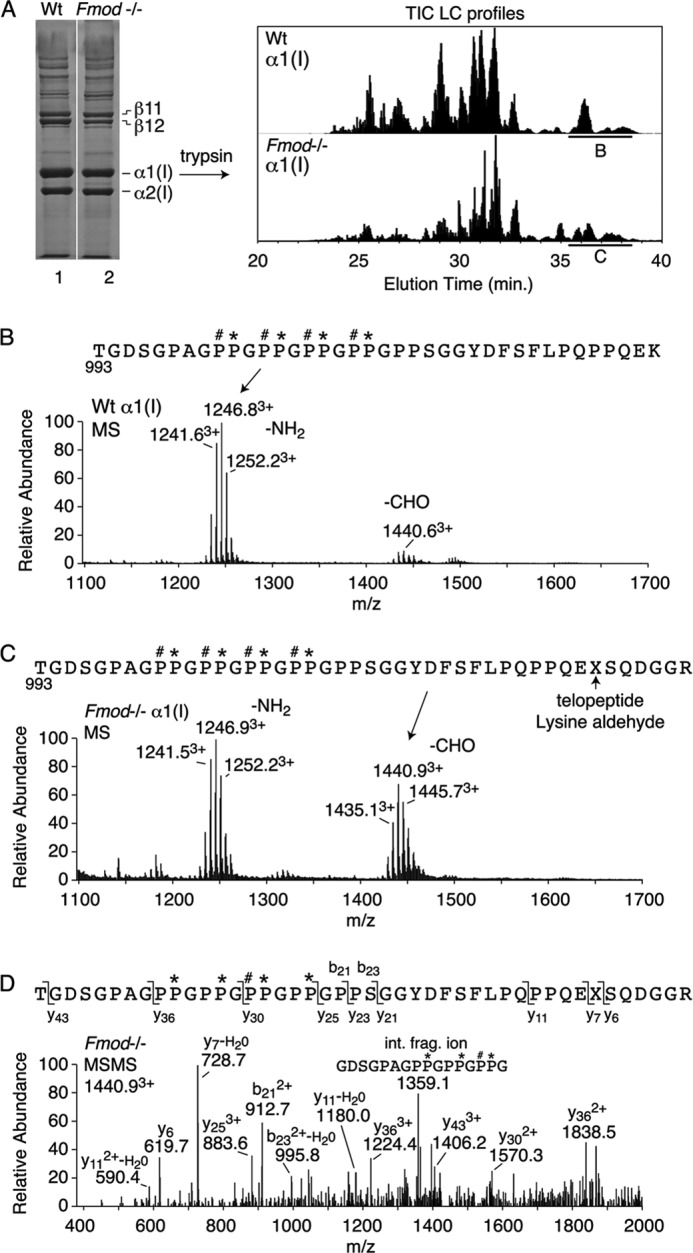

Mass spectral analysis of the excised, trypsin-digested α1(I) chains (Fig. 4) confirmed the higher degree of lysyl oxidase-mediated C-telopeptide aldehyde formation in the Fmod−/− tendon. Trypsin does not cleave after the cross-linking lysine when converted to an aldehyde and produces a 6-residue longer telopeptide cleaving after arginine. This tryptic peptide includes the (GPP)n sequence from the end of the triple-helix, which is a unique site of prolyl 3-hydroxylation in tendon type I collagen (4) explaining the +16 Dalton mass ladder evident for the molecular ions in Fig. 4. The degree of prolyl 3-hydroxylation was found to be similar in Fmod−/− and wild-type collagen.

FIGURE 4.

Mass spectral analysis of the C-terminal domain of collagen α1(I) chains extracted from Fmod−/− and wild-type tendons. A, heat-denatured extract of tendon collagen was run on 6% SDS-PAGE, and excised α1(I) chains were digested in-gel with trypsin and the peptides profiled by LC-tandem mass spectrometry. B–D, the C-terminal tryptic peptide domain (underlined in total ion current (TIC) profile), identified by MSMS fragmentation (D), showed more of the longer aldehyde-containing peptide from Fmod−/− tissue (C) than from wild type (B). Note that the (GPP)5 C terminus of the triple-helix is equally modified with up to four 3-hydroxyproline residues per chain in both Fmod−/− and wild-type tendon collagen, a post-translational modification that is peculiar to tendon (4).

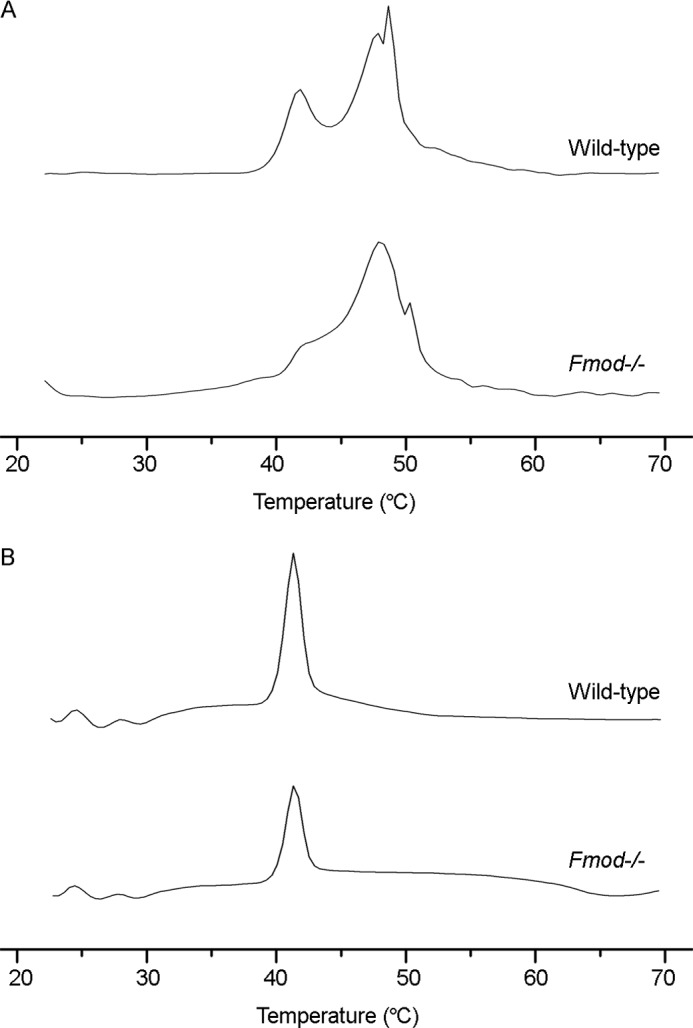

Differential Scanning Calorimetry Indicates Increased Cross-linking in Fmod−/− Collagen

Differential scanning calorimetry revealed different thermograms during denaturation of acid-extracted wild-type and Fmod−/− collagen (Fig. 5A). (Denaturation curve interpretation is described in Ref. 32.) Although both extracts generated a 41.8 °C peak corresponding to monomeric collagen, this peak was smaller for the Fmod−/− collagen. Shift in heat capacity from monomer to cross-linked forms (i.e. peaks between 45–52 °C) was prominent in Fmod−/− extracts, indicating excessive and dysregulated cross-linking. In contrast, denaturation of pepsin-treated collagen (in which cross-links are in effect removed by pepsin cleaving the telopeptides internal to the cross-linking residues) yielded a single denaturation peak at 41 °C in both samples (Fig. 5B). These data support the interpretation that fibromodulin deficiency in tendon results in excessive collagen cross-linking.

FIGURE 5.

Differential scanning calorimetry of collagen. A, acid-extracted collagen in phosphate-glycerol pH 7.4 buffer was melted in a differential scanning calorimeter heating at 0.25 °C/min. B, as in A, but prior to analysis the acid-extracted collagen was pepsin-treated, precipitated with salt, resuspended in acetic acid, and dialyzed against phosphate-glycerol buffer.

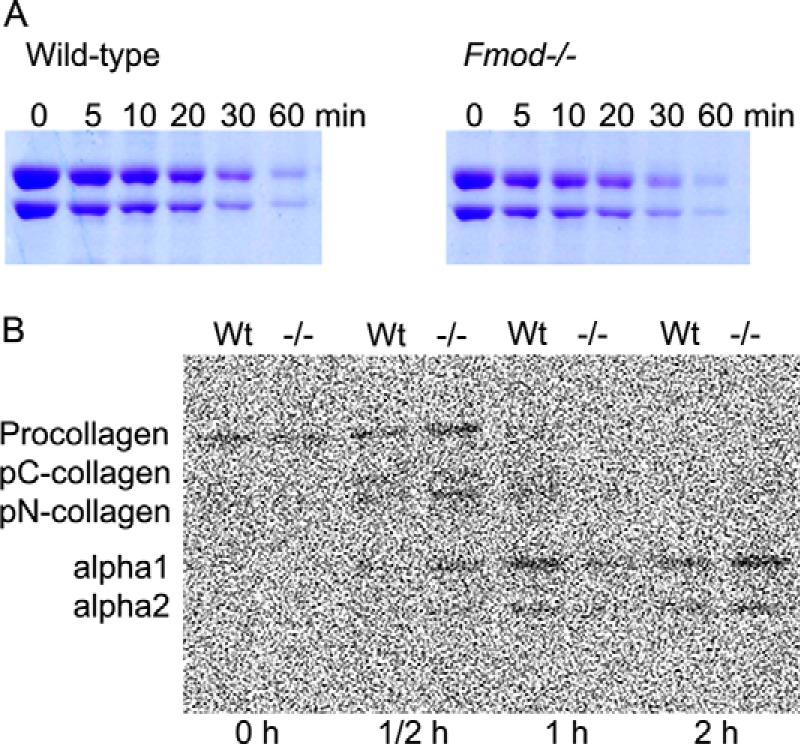

Fibromodulin Deficiency Does Not Influence Procollagen Processing, Denaturation, or the Hydroxylation of Lysines or Pralines

We also considered other mechanisms by which fibromodulin deficiency could impede collagen fibril assembly. The presence of denatured collagen in Fmod−/− tendons was ruled out by finding no difference in the time course of degradation in a trypsin sensitivity assay (Fig. 6A). Procollagen processing was unchanged in cultures of Fmod−/− vascular smooth muscle cells. (These cells, and not tendon fibroblasts, were used because we have found that the latter lose their fibromodulin expression when cultured in flasks (Fig. 6B)).2 Post-translational hydroxylation of prolines and lysines was also unaffected; hydroxyproline comprised 8.2% and hydroxylysine comprised 0.7% of total amino acid content in both wild-type and Fmod−/− mice.

FIGURE 6.

A, collagen trypsin sensitivity assay. Acid-extracted collagen was neutralized and incubated with trypsin (1:100 w/w). Aliquots (5 μg) of collagen were removed at indicated time points, and trypsin activity was quenched by adding SDS loading buffer. The amount of proteolysis was assessed by SDS-PAGE staining with Coomassie Blue. B, procollagen processing assay. Primary cultures of smooth muscle cells from Fmod−/− and wild-type aortas were pulsed with 2.5 μCi/ml of [14C]proline and chased from 0 to 2 h. Procollagen was acetone-precipitated from the medium, run on SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiography.

DISCUSSION

The most prominent tissue phenotype of fibromodulin-null mice is abnormal tendon. The tendons have reduced tensile strength, and the animals develop secondary osteoarthritis (14, 15). Collagen fibrils in tendons and ligaments appear morphologically abnormal on electron microscopy. Carcinomas induced in Fmod−/− mice also have a less dense collagenous stroma (33). Because fibromodulin can inhibit collagen fibril formation at relatively low molar concentrations (26), one of the functions of fibromodulin in a developing connective tissue matrix appears to be in modulating the assembly of collagen monomers into fibrils. The mechanism is not understood. Here we report findings showing that Fmod−/− tendons differ from wild type in having more lysyl oxidase-mediated stable cross-links formed through their type I collagen C-telopeptide domains.

We focused the study on tail tendon collagen. On sequential extraction, acetic acid solubilized only 20% of the total collagen from Fmod−/− tendons, compared with 75% of the total collagen from wild-type tendons. This difference suggested altered intermolecular cross-linking. Differences in cross-linking were revealed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). The Fmod−/− collagen had a higher ratio of α2(I) to α1(I) chains, a deficiency of β12 dimer, and a higher proportion of α1(I) chains in stably cross-linked oligomers on SDS-PAGE. Also, a CNBr digest of the Fmod−/− tendons contained less α1(I)CB6 monomer containing an unmodified C-telopeptide lysine (Fig. 2C). This can best be explained by more complete cross-linking of the α1(I) chains caused by a higher proportion having their C-telopeptide lysines converted to aldehydes by lysyl oxidase. This results in more acid-stable aldols being formed between two α1(I) C-telopeptides, which can account for the observed increase in the γ112 trimer (and other acid-stable oligomers involving α1(I)). Therefore, the apparent increase in uncross-linked α2(I) chains is in fact due to a decrease in α1(I) monomers. The mass spectral analyses of bacterial collagenase-digested whole tendon established that indeed a higher proportion of total α1(I) C-telopeptides were present as the lysine aldehyde in Fmod−/− versus wild-type collagen (Figs. 3 and 4). The results suggest that fibromodulin binds to the surface molecules of growing fibrils and inhibits lysyl oxidase activity in a significant proportion of their α1(I) C-telopeptide domains. The increased C-telopeptide lysine oxidation in Fmod−/− mice can explain the decrease in acid-soluble collagen and the increase in the pepsin-soluble pool if the resulting aldol cross-links are intermolecular.

We excluded the unlikely possibility that α2(I) chains had formed triple helical molecules other than [α1α1α2] in the null mice because the melting temperature of monomeric collagen molecules was unchanged (Fig. 5). Fibromodulin deficiency also did not appear to affect post-translational modifications of collagen in the triple-helix because the amount of 4-hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine was similar in Fmod−/− and wild-type mouse tendon on amino acid analysis.

Mass spectral analysis of trypsin or bacterial collagenase-generated peptides was less informative on the cross-linking status of the N-telopeptides. Aldol intramolecular cross-links between α1-α1 and α1-α2 N-telopeptides are known to be the main source of the β dimers seen on electrophoresis of skin and tendon type I collagen. SDS-PAGE indicated normal amounts of β11 and evidence that β12 was shifted to γ and higher cross-linked oligomers in Fmod−/− collagen (Figs. 1 and 2). The latter shift is explained by excessive C-telopeptide cross-linking, which we confirmed by mass spectral analyses. In interpreting the tissue extraction and gel electrophoresis patterns, note that aldol cross-links are stable to low pH and denaturation, whereas aldimine (Schiff's base) cross-links formed between lysine aldehyde and hydroxylysine or lysine are not. This can explain the differences in chain and CNBr peptide profiles seen on electrophoresis (Figs. 1 and 2).

The collagen assembled without fibromodulin also had altered physical properties, as revealed by differential scanning calorimetry. Thermal denaturation of collagen includes an initial melting of less cross-linked triple-helical monomers at lower temperature, followed by denaturation of cross-linked collagen molecules, whereas any inherently denatured collagen cannot refold at physiological temperatures and so does not contribute to a thermogram (32, 34). In addition, the denaturation peak pattern of a DSC thermogram correlates with the degree of intermolecular cross-linking (35), supported by the similar melting points and enthalpies of the pepsin-treated (i.e. non-cross-linked) collagens. The altered physical properties of collagen in Fmod−/− tendons may regulate cellular behavior, including cell migration, survival, and matrix protein synthesis (36, 37).

In summary, we propose that fibromodulin modifies covalent cross-linking of type I collagen during fibril assembly by modulating lysyl oxidase action on the C-telopeptide lysines. It is clear that other SLRPs such as lumican (which is elevated in content (14)) do not replace fibromodulin in this activity. It implies that individual SLRPs may have evolved distinct activities affecting cross-linking during fibril growth and maturation. Absence of one constraining protein (in this case fibromodulin) may allow premature assembly of intermediates and their cross-linking through α1(I) C-telopeptide aldehydes, which results in deregulated growth of fibrils and of the tendon. Collectively, our findings suggest that collagen, despite its self-assembling properties, has evolved to be finely regulated by many fibril-associating proteins along its surface that tailor it for specialized tissue functions.

It is also intriguing that increased lysyl oxidase-mediated cross-linking leads to mechanically weaker tendons. This finding may seem counter-intuitive, but it emphasizes the importance of understanding not just the total number and stability of covalent cross-links but also their placement, for example whether they are solely intrafibrillar or can also form interfibrillar bonds as fibrils grow and interact. One possible explanation for decreased tissue tensile strength in Fmod−/− is loss of latent fibril surface C-telopeptide lysines to allow fibril to fibril bonding during tissue growth. Clearly, collagen-binding members of the SLRP family have the potential to play a major role in such processes. To what degree SLRPs other than fibromodulin have evolved to directly modulate access to lysyl oxidase(s) during collagen fibrillogenesis by related mechanisms deserves attention.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Dick Heinegård for invaluable scientific discussions and for supporting this work.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AR036794 and AR037318 (to D. R. E.). This work was also supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Cancer Foundation, Crafoord Foundation, King Gustaf V's 80th Anniversary Fund, Magnus Bergvall Foundation, Åke Wiberg Foundation, Greta and Johan Kock's Foundation, and Alfred Österlund's Foundation.

K. Rubin, unpublished observation.

M. Weis and D. R. Eyre, unpublished observation.

- SLRP

- small leucine-rich repeat protein

- DSC

- differential scanning calorimetry.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eyre D. R., Paz M. A., Gallop P. M. (1984) Cross-linking in collagen and elastin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53, 717–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu J. J., Woods P. E., Eyre D. R. (1992) Identification of cross-linking sites in bovine cartilage type IX collagen reveals an antiparallel type II-type IX molecular relationship and type IX to type IX bonding. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 23007–23014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hanson D. A., Eyre D. R. (1996) Molecular site specificity of pyridinoline and pyrrole cross-links in type I collagen of human bone. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 26508–26516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eyre D. R., Weis M., Hudson D. M., Wu J. J., Kim L. (2011) A novel 3-hydroxyproline (3Hyp)-rich motif marks the triple-helical C terminus of tendon type I collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7732–7736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalamajski S., Oldberg A. (2010) The role of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in collagen fibrillogenesis. Matrix Biol. 29, 248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Danielson K. G., Baribault H., Holmes D. F., Graham H., Kadler K. E., Iozzo R. V. (1997) Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J. Cell Biol. 136, 729–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang G., Ezura Y., Chervoneva I., Robinson P. S., Beason D. P., Carine E. T., Soslowsky L. J., Iozzo R. V., Birk D. E. (2006) Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J. Cell Biochem. 98, 1436–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fust A., LeBellego F., Iozzo R. V., Roughley P. J., Ludwig M. S. (2005) Alterations in lung mechanics in decorin-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 288, L159–L166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu C. Y., Birk D. E., Hassell J. R., Kane B., Kao W. W. (2003) Keratocan-deficient mice display alterations in corneal structure. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21672–21677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pellegata N. S., Dieguez-Lucena J. L., Joensuu T., Lau S., Montgomery K. T., Krahe R., Kivelä T., Kucherlapati R., Forsius H., de la Chapelle A. (2000) Mutations in KERA, encoding keratocan, cause cornea plana. Nat. Genet. 25, 91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu T., Bianco P., Fisher L. W., Longenecker G., Smith E., Goldstein S., Bonadio J., Boskey A., Heegaard A. M., Sommer B., Satomura K., Dominguez P., Zhao C., Kulkarni A. B., Robey P. G., Young M. F. (1998) Targeted disruption of the biglycan gene leads to an osteoporosis-like phenotype in mice. Nat. Genet. 20, 78–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yeh J. T., Yeh L. K., Jung S. M., Chang T. J., Wu H. H., Shiu T. F., Liu C. Y., Kao W. W., Chu P. H. (2010) Impaired skin wound healing in lumican-null mice. Br. J. Dermatol. 163, 1174–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chakravarti S., Petroll W. M., Hassell J. R., Jester J. V., Lass J. H., Paul J., Birk D. E. (2000) Corneal opacity in lumican-null mice: defects in collagen fibril structure and packing in the posterior stroma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 3365–3373 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Svensson L., Aszódi A., Reinholt F. P., Fässler R., Heinegård D., Oldberg A. (1999) Fibromodulin-null mice have abnormal collagen fibrils, tissue organization, and altered lumican deposition in tendon. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9636–9647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gill M. R., Oldberg A., Reinholt F. P. (2002) Fibromodulin-null murine knee joints display increased incidences of osteoarthritis and alterations in tissue biochemistry. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 10, 751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ezura Y., Chakravarti S., Oldberg A., Chervoneva I., Birk D. E. (2000) Differential expression of lumican and fibromodulin regulate collagen fibrillogenesis in developing mouse tendons. J. Cell Biol. 151, 779–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jepsen K. J., Wu F., Peragallo J. H., Paul J., Roberts L., Ezura Y., Oldberg A., Birk D. E., Chakravarti S. (2002) A syndrome of joint laxity and impaired tendon integrity in lumican- and fibromodulin-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35532–35540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang G., Chen S., Goldoni S., Calder B. W., Simpson H. C., Owens R. T., McQuillan D. J., Young M. F., Iozzo R. V., Birk D. E. (2009) Genetic evidence for the coordinated regulation of collagen fibrillogenesis in the cornea by decorin and biglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8888–8897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Svensson L., Närlid I., Oldberg A. (2000) Fibromodulin and lumican bind to the same region on collagen type I fibrils. FEBS Lett. 470, 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalamajski S., Oldberg A. (2007) Fibromodulin binds collagen type I via Glu-353 and Lys-355 in leucine-rich repeat 11. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26740–26745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalamajski S., Oldberg A. (2009) Homologous sequence in lumican and fibromodulin leucine-rich repeat 5–7 competes for collagen binding. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 534–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalamajski S., Aspberg A., Oldberg A. (2007) The decorin sequence SYIRIADTNIT binds collagen type I. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16062–16067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kalamajski S., Aspberg A., Lindblom K., Heinegård D., Oldberg A. (2009) Asporin competes with decorin for collagen binding, binds calcium and promotes osteoblast collagen mineralization. Biochem. J. 423, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sini P., Denti A., Tira M. E., Balduini C. (1997) Role of decorin on in vitro fibrillogenesis of type I collagen. Glycoconj J. 14, 871–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vogel K. G., Paulsson M., Heinegård D. (1984) Specific inhibition of type I and type II collagen fibrillogenesis by the small proteoglycan of tendon. Biochem. J. 223, 587–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hedbom E., Heinegård D. (1989) Interaction of a 59-kDa connective tissue matrix protein with collagen I and collagen II. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 6898–6905 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Font B., Eichenberger D., Goldschmidt D., Boutillon M. M., Hulmes D. J. (1998) Structural requirements for fibromodulin binding to collagen and the control of type I collagen fibrillogenesis: critical roles for disulphide bonding and the C-terminal region. Eur. J. Biochem. 254, 580–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stamov D. R., Müller A., Wegrowski Y., Brezillon S., Franz C. M. (2013) Quantitative analysis of type I collagen fibril regulation by lumican and decorin using AFM. J. Struct. Biol. 183, 394–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miller E. J., Rhodes R. K. (1982) Preparation and characterization of the different types of collagen. Methods Enzymol. 82, 33–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cutroneo K. R., Counts D. F. (1975) Anti-inflammatory steroids and collagen metabolism: glucocorticoid-mediated alterations of prolyl hydroxylase activity and collagen synthesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 11, 632–639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schwarze U., Cundy T., Pyott S. M., Christiansen H. E., Hegde M. R., Bank R. A., Pals G., Ankala A., Conneely K., Seaver L., Yandow S. M., Raney E., Babovic-Vuksanovic D., Stoler J., Ben-Neriah Z., Segel R., Lieberman S., Siderius L., Al-Aqeel A., Hannibal M., Hudgins L., McPherson E., Clemens M., Sussman M. D., Steiner R. D., Mahan J., Smith R., Anyane-Yeboa K., Wynn J., Chong K., Uster T., Aftimos S., Sutton V. R., Davis E. C., Kim L. S., Weis M. A., Eyre D., Byers P. H. (2013) Mutations in FKBP10, which result in Bruck syndrome and recessive forms of osteogenesis imperfecta, inhibit the hydroxylation of telopeptide lysines in bone collagen. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leikina E., Mertts M. V., Kuznetsova N., Leikin S. (2002) Type I collagen is thermally unstable at body temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1314–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oldberg A., Kalamajski S., Salnikov A. V., Stuhr L., Mörgelin M., Reed R. K., Heldin N. E., Rubin K. (2007) Collagen-binding proteoglycan fibromodulin can determine stroma matrix structure and fluid balance in experimental carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13966–13971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flandin F., Buffevant C., Herbage D. (1984) A differential scanning calorimetry analysis of the age-related changes in the thermal stability of rat skin collagen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 791, 205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Horgan D. J., King N. L., Kurth L. B., Kuypers R. (1990) Collagen crosslinks and their relationship to the thermal properties of calf tendons. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 281, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koyama H., Raines E. W., Bornfeldt K. E., Roberts J. M., Ross R. (1996) Fibrillar collagen inhibits arterial smooth muscle proliferation through regulation of Cdk2 inhibitors. Cell 87, 1069–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schlessinger J. (1997) Direct binding and activation of receptor tyrosine kinases by collagen. Cell 91, 869–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]