Background: The Sec translocon mediates protein secretion in all organisms.

Results: YfgM interacts with the Sec translocon and is part of a periplasmic chaperone network in Escherichia coli.

Conclusion: We propose that YfgM mediates protein transfer from the Sec translocon to periplasmic chaperones.

Significance: This study provides a better understanding of the composition of the Sec translocon.

Keywords: Escherichia coli (E. coli), Membrane Biogenesis, Membrane Protein, Protein Secretion, Protein Translocation, BN-PAGE, SecYEG Translocon, Periplasmic Chaperones

Abstract

Protein secretion in Gram-negative bacteria is essential for both cell viability and pathogenesis. The vast majority of secreted proteins exit the cytoplasm through a transmembrane conduit called the Sec translocon in a process that is facilitated by ancillary modules, such as SecA, SecDF-YajC, YidC, and PpiD. In this study we have characterized YfgM, a protein with no annotated function. We found it to be a novel ancillary subunit of the Sec translocon as it co-purifies with both PpiD and the SecYEG translocon after immunoprecipitation and blue native/SDS-PAGE. Phenotypic analyses of strains lacking yfgM suggest that its physiological role in the cell overlaps with the periplasmic chaperones SurA and Skp. We, therefore, propose a role for YfgM in mediating the trafficking of proteins from the Sec translocon to the periplasmic chaperone network that contains SurA, Skp, DegP, PpiD, and FkpA.

Introduction

A number of different protein secretion systems are available in Gram-negative bacteria; however, the vast majority of secreted proteins utilize a transmembrane conduit called the Sec translocon (SecYEG in Escherichia coli) (1, 2). This multipurpose device can facilitate co-translational insertion of proteins into the inner membrane and post-translational translocation of proteins to the periplasmic space (3–6). The latter category includes lipoproteins, β-barrel proteins, and extracellular proteins, which are subsequently trafficked from the periplasm to their final destination by other dedicated pathways (7–11).

There is considerable interest in understanding how the Sec translocon inserts and translocates proteins. Crystal structures indicate that it has an hourglass shape with a central constriction that comprises a ring of hydrophobic residues and a short “plug” helix (12–15). An opening between transmembrane helices 2 and 7 is postulated to act as a lateral-exit gate for signal sequences and transmembrane helices. Current opinion favors a model whereby docking of a signal sequence or a transmembrane helix at the lateral-exit gate signals movement of the plug and enables protein translocation (3–6).

The Sec translocon is essentially a passive pore, and it requires ancillary modules to facilitate insertion and/or translocation. For example, translational elongation by the ribosome provides a driving force for co-translational insertion of inner membrane proteins (3–6), and YidC facilitates their insertion into the lipid bilayer (16–18). Secreted proteins and large soluble domains in membrane proteins are “pushed” through the translocon by SecA and the SecDF-YajC complex (15, 19, 20). The ancillary modules can in most cases be co-purified with the translocon after detergent solubilization (17, 18, 21, 22); thus, it seems likely that they are physically associated in the lipid bilayer.

Have all ancillary modules of the Sec translocon been identified? Recently we reported that YfgM, a protein with no annotated function, interacts with PpiD in the inner membrane of E. coli (23). Because PpiD is thought to act as a periplasmic gatekeeper for the translocon (24), we reasoned that YfgM might have a similar role. YfgM (like PpiD) is an inner membrane protein with a single transmembrane helix and a large C-terminal periplasmic domain (23, 25, 26). In this study we present data that indicate that YfgM interacts with the SecYEG translocon and that it operates in the periplasmic chaperone network consisting of SurA, Skp, DegP, PpiD, and FkpA.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Microbial Techniques

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids were constructed using standard molecular biology techniques or the In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (Clontech). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All plasmids were confirmed by sequencing (MWG). Disruption of chromosomal genes in MC4100 and W3110 was carried out by bacteriophage P1 transduction from the Keio collection (27). In some strains the kanamycin cassette in the target strain was eliminated by the pCP20 method as described in Datsenko and Wanner (28). These strains were confirmed by diagnostic PCR. All strains in this study were cultured at 37 °C in standard LB broth (Difco) supplemented with 25/50 μg/ml kanamycin, 17 μg/ml chloramphenicol, or 50/100 μg/ml ampicillin when necessary.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Relevant characteristics | Reference or source | |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| BL21(DE3) | Carrying pLysS | Invitrogen |

| W3110 | Our collection | |

| ΔyfgM ΔppiD | W3110 ΔyfgM + ppiD::kan | This study |

| MC4100 | Our collection | |

| ΔdegP | MC4100 degP::kan | M. Sousa |

| ΔyfgM | MC4100 yfgM::kan | This study |

| Δskp | MC4100 skp::kan | This study |

| ΔsurA | MC4100 surA::kan | This study |

| ΔppiD | MC4100 ppiD::kan | This study |

| ΔyfgM ΔppiD | MC4100 ΔppiD + yfgM::kan | This study |

| ΔyfgM ΔdegP | MC4100 ΔdegP + yfgM::kan | This study |

| ΔyfgM Δskp | MC4100 Δskp + yfgM::kan | This study |

| ΔyfgM ΔsurA | MC4100 ΔsurA + yfgM::kan | This study |

| ΔppiD ΔdegP | MC4100 ΔdegP + ppiD::kan | This study |

| ΔppiD Δskp | MC4100 ΔppiD + skp::kan | This study |

| ΔppiD ΔsurA | MC4100 ΔppiD + surA::kan | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSc-yfgM | yfgM + native promoter in pUA66 | This study |

| pUA66 | Low copy plasmid with sc101 origin of replication | (30) |

| pUA66-rpoE-gfpmut2 cm | Cm resistance rpoE rseABC reporter | This study |

| pUA66-ppiA-gfpmut2 cm | Cm resistance ppiA reporter | This study |

| pUA66-rpoE-gfpmut2 | Km resistance rpoE rseABC reporter | (30) |

| pUA66-ppiA-gfpmut2 | Km resistance ppiA reporter | (30) |

| pCP20 | Flp recombinase gene | (28) |

| pETDuet-ppiD37H8 | Expression of PpiDSOL | This study |

| pET28ayfgM45H8 | Expression of YfgMSOL | This study |

Immunoprecipitations

Whole cells were grown in 10 ml of M9 minimal media supplemented with 100 μg/ml thiamine, 0.2 (w/v) % glucose, 1 mm MgSO4, 50 μm CaCl2, and 2 mg/ml Complete Supplement Mixture amino acids minus methionine. At an A600 of 0.6 the cells were labeled with 15 μCi/ml [35S]methionine for 10 min, then harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 10 min. The cell pellet was frozen then thawed on ice and resuspended in 1 ml of immunoprecipitation (IP)2 buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 20% (w/v) glycerol, Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture Tablets (Roche Applied Science)). Cell lysis was induced by the addition of 10 mm EDTA, 1 mg/ml lysozyme and incubation on ice for 30 min. 1% (w/v) digitonin (native IPs) or 1% (w/v) Triton X-100, 0.2% (w/v) SDS (denaturing IPs) was added, and lysis was allowed to continue on ice for an additional hour (with occasional vortexing). The extract was retrieved by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 20 min. The preparation yielded enough material for 5 IPs.

The antisera (2.5 μl) were coupled to 10 μl of GammaBind G-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) then prewashed with 300 μl of IP buffer. 200 μl of extract was bound by incubation at 4 °C for 30 min and washed 3 times with 300 μl of IP buffer containing either 1% (w/v) digitonin (native IPs) or 1% (w/v) Triton X-100, 0.2% (w/v) SDS (denaturing IPs). Proteins were eluted from the beads by heating at 95 °C in Laemmli buffer for 5 min and then separated by 14% SDS-PAGE. Gels were dried and imaged with Fuji FLA-3000 phosphorimaging.

Two-dimensional Gel Electrophoresis-BN-/SDS-PAGE

Inner membrane vesicles were prepared as described previously (23, 29) with few minor changes. Briefly, cells were grown in LB media by shaking at 37 °C to A600 = 0.9 then broken using an Emulsiflex-C3 (Avestin). Unbroken cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 8000 × g at 4 °C. The membrane fraction was collected by ultracentrifugation for 60 min at 180,000 × g at 4 °C then separated into fractions containing inner and outer membrane vesicles using a six-step sucrose gradient. Inner membrane vesicles were resuspended in ACA750 buffer (750 mm n-amino-caproic acid, 50 mm Bis-Tris, 0.5 mm Na2EDTA, pH 7.0), and the protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Inner membrane proteins were solubilized by resuspending 500 μg of inner membrane vesicles in 100 μl of ACA750 buffer containing 1% (w/v) digitonin for 60 min on ice. Insoluble membrane debris was removed by centrifugation for 20 min at 264,000 × g, and the sample was mixed with 15 μl of G250 solution (5% (w/v) Coomassie G250 in ACA750 buffer). Samples were separated in the first dimension by 5–15% BN-PAGE and in the second dimension by 8–16% SDS-PAGE as described previously (23, 29). Proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes using a semi-dry blotting device (Bio-Rad) and decorated with rabbit antisera raised against YfgM/PpiD (see below), SecY, SecE, and YidC. A donkey anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate secondary antibody was used (GE Healthcare). For detection, the ECL system (GE Healthcare) and a LAS-1000 CCD camera (Fujifilm) were used. Images were analyzed with the Image Gauge Version 4.23 software (Fujifilm).

Production of YfgM/PpiD Antisera

The full-length YfgM and PpiD were co-purified as described in Maddalo et al. (23). A single rabbit polyclonal antisera was produced by Innovagen AB (Sweden).

Antibiotic Susceptibility Disc Assays

Cells were grown to an A600 nm ≈ 0.8, and a volume equivalent to 0.2 A600 units was plated onto LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics (kanamycin 50 μg/ml and chloramphenicol 17 μg/ml). Cultures were evenly spread then let dry before discs containing 30 μg of vancomycin (Oxoid) were placed on the agar. Inhibition zone radii were measured after 16 h at 37 °C.

σE and Cpx Stress Response Assay

Reporter plasmids for σE- and Cpx-dependent envelope stress responses (rpoE rseABC-gfp and ppiA-gfp, respectively) were obtained from (30), and the kanamycin resistance cassette was replaced with a chloramphenicol resistance cassette. Strains were transformed with the plasmids and selected on LB agar supplemented with 17 μg/ml chloramphenicol (and kanamycin if required by the host strain). Three colonies were grown in liquid LB media at 37 °C to an A600 of ∼0.8. The cells were concentrated by centrifugation at 4000 × g and resuspended in 200 μl of buffer G (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 15 mm EDTA). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence was measured (488-nm excitation − 512-nm emission) in a Spectramax GEMINI EM microplate reader (Molecular Devices) and normalized by the corresponding A600 value.

Purification of YfgMSOL and PpiDSOL

The regions encoding amino acids 45–206 of YfgM and 37–623 of PpiD were cloned downstream of a region coding for an octahistidine tag (−His8) in the pGFPE vector (a derivative of pET28a (31, 32)). The plasmids were individually transformed into the BL21(DE3) pLysS and grown in LB supplemented with 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 50 μg/ml kanamycin to an A600 of ∼0.4. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 5 h at 37 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000 × g then resuspended in disruption buffer (PBS, pH 7.4, complete protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science), 10 μg of DNAse I) and mechanically broken using an Emulsiflex-C3 (Avestin). Membrane debris was removed by ultracentrifugation at 180,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The soluble fraction was supplemented with 10 mm imidazole and cycled over an equilibrated 5-ml HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare). Impurities were removed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer (PBS, pH 7.4, 70 mm imidazole, 150 mm NaCl), and YfgMSOL/PpiDSOL were eluted by increasing the concentration of the wash buffer to 500 mm using a linear gradient of 100 ml. For further purification and buffer exchange to 20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, and 150 mm NaCl, a Superdex 200 10/300 column was used (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing the desired protein were pooled and concentrated using a 10-kDa cut-off concentrator (Sartorius Stedim A/S). SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie staining was used to assess the purity of the proteins.

Protein Aggregation Assays

Firefly luciferase aggregation was performed as described in Cajo et al. (33), except that luciferase was denatured for 90 min at 25 °C and aggregation kinetics were followed at 25 °C (34).

Unfolded proOmpC (200 μm in 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 20% glycerol, 8 m urea) prewarmed for 10 min at 60 °C was diluted 100-fold in reaction buffer (30 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 40 mm KCl, 50 mm NaCl, 7 mm magnesium acetate, and 1 mm DTT) preincubated at 25 °C with or without chaperones. Immediately after the addition of denatured proOmpC, aggregation was monitored continuously at 320 nm for 60 min at 25 °C on a Cary Scan UV-visible spectrophotometer from Varian. All solutions used in this assay were filtered through a 0.22-μm filter (35).

Malate dehydrogenase (1 μm monomer in the final reaction; Roche Applied Science) was incubated in the presence or absence of preincubated protein for 30 min at 30 °C or 47 °C in 50 μl of reaction buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm KCl, 20 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT. Samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C. Supernatant and pellet were analyzed separately by 4–12% SDS-PAGE and then stained with Coomassie Blue.

RESULTS

YfgM Interacts with the SecYEG Translocon

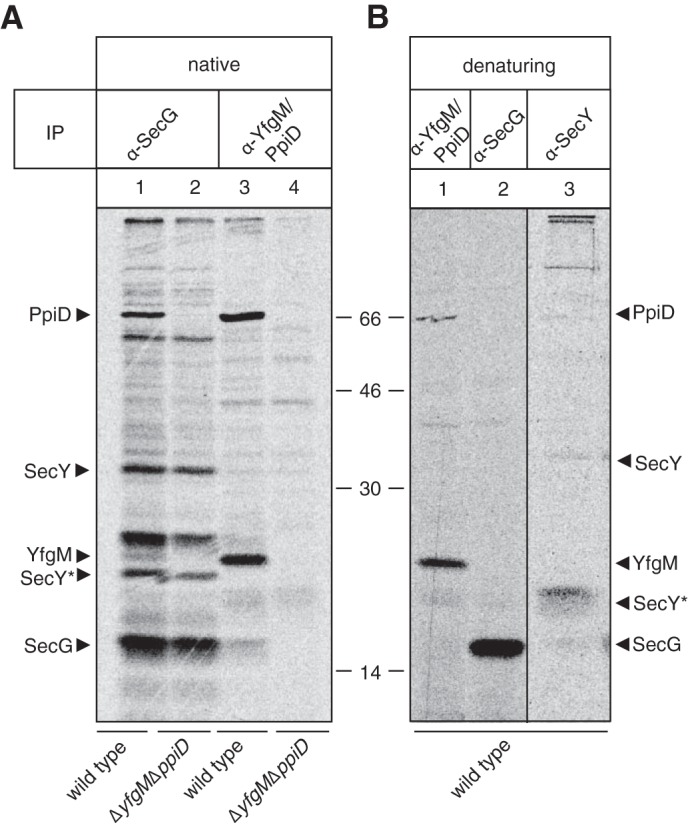

To determine if YfgM interacts with the Sec translocon, we initially tried to detect it after co-IP with SecG antisera. We radiolabeled wild type cells with [35S]methionine, extracted membrane protein complexes with digitonin and immunoprecipitated SecG using native conditions. Approximately 10 prominent bands were detected when the samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (Fig. 1A, lane 1). Two of the bands corresponded in molecular mass to YfgM (22 kDa) and PpiD (68 kDa) and could be assigned by repeating the experiment in a strain devoid of yfgM and ppiD (Fig. 1A, lane 2). Two bands appeared at the same molecular mass as SecY and the processed form of SecY, called SecY* (Fig. 1A, lane 2 versus Fig. 1B, lane 3). Other bands that were co-immunoprecipitated with the SecG antisera have not been assigned in this study, as this has been done previously (21).

FIGURE 1.

YfgM and PpiD form a detergent-stable supercomplex with the Sec translocon. A, IP of membrane protein complexes from wild type E. coli and the ΔppiD ΔyfgM strain using antisera to SecG or YfgM/PpiD. Whole cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine and solubilized in buffer containing 1% (w/v) digitonin. The immunoprecipitation was carried out under native conditions so that interacting partners could be co-immunoprecipitated. B, IPs from wild type cells using antisera to SecY, SecG, and YfgM/PpiD were carried out under denaturing conditions to show the specificity of the antibodies and assign bands in A. Note that the lower molecular weight band observed for SecY indicated that it was the processed form (termed SecY*), as described by Akiyama and Ito (58).

We also performed a reciprocal co-IP. In this experiment SecG was co-immunoprecipitated with YfgM/PpiD antisera (Fig. 1A, lane 3). Notably, SecG was not co-immunoprecipitated in a strain devoid of yfgM and ppiD (Fig. 1A, lane 4); thus it is unlikely that the antisera unspecifically recognizes SecG. SecY was not detected in this experiment. We believe that this was a technical artifact rather than a biological observation, as we detected SecY when we co-immunoprecipitated with SecG antisera and in BN-PAGE analysis (see below).

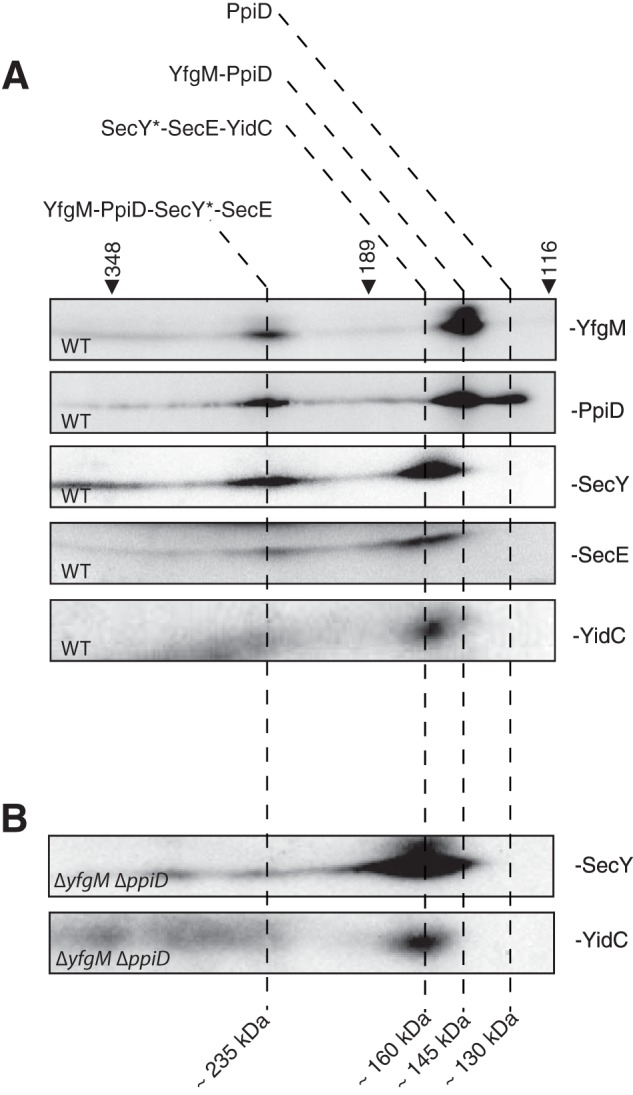

To obtain complementary evidence that YfgM interacts with the translocon, we solubilized protein complexes from wild type inner membranes with digitonin then separated them by two-dimensional BN-/SDS-PAGE. Proteins were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and identified with antisera raised against YfgM/PpiD, SecY, and SecE. All proteins aligned in a vertical channel of ∼235 kDa, indicating that they had co-migrated in the non-denaturing BN-PAGE (Fig. 2A). The analysis also detected vertical channels containing YfgM and PpiD (∼145 kDa) and PpiD only (∼130 kDa) (Fig. 2A). Thus there appear to be populations of YfgM and PpiD that are independent from the translocon. Finally, we detected a complex containing SecY, SecE, and YidC (Fig. 2A). This latter observation suggests that there might be different populations of the Sec translocon.

FIGURE 2.

Two-dimensional BN-/SDS-PAGE indicates that YfgM and PpiD are in complex with a sub-population of the Sec translocon. A, inner membrane proteins from wild type E. coli were solubilized in 1% digitonin, separated by two-dimensional BN-/SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and immuno-decorated with protein-specific antisera. Proteins that align in vertical channels were deemed to be in complexes. Note that the molecular weight observed for SecY indicated that it was processed (termed SecY*), as described by Akiyama and Ito (58). B, SecY* shifts to a lower molecular mass when a ΔppiD ΔyfgM strain is analyzed by two-dimensional BN-/SDS-PAGE. Molecular mass markers (in kDa) were calibrated to membrane proteins (29).

Co-migration of proteins in BN-PAGE is usually considered proof that they form a detergent-stable complex. Nevertheless we substantiated our observation that YfgM and PpiD co-migrated with the Sec translocon by analyzing membrane protein complexes from the ΔppiD ΔyfgM strain. In this experiment, the vast majority of SecY* shifted from ∼235 to ∼160 kDa (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the co-IP analyses and BN-PAGE unequivocally show that YfgM co-purifies with the SecYEG translocon when digitonin is used for solubilization of membrane proteins.

YfgM Contributes to Outer Membrane Integrity

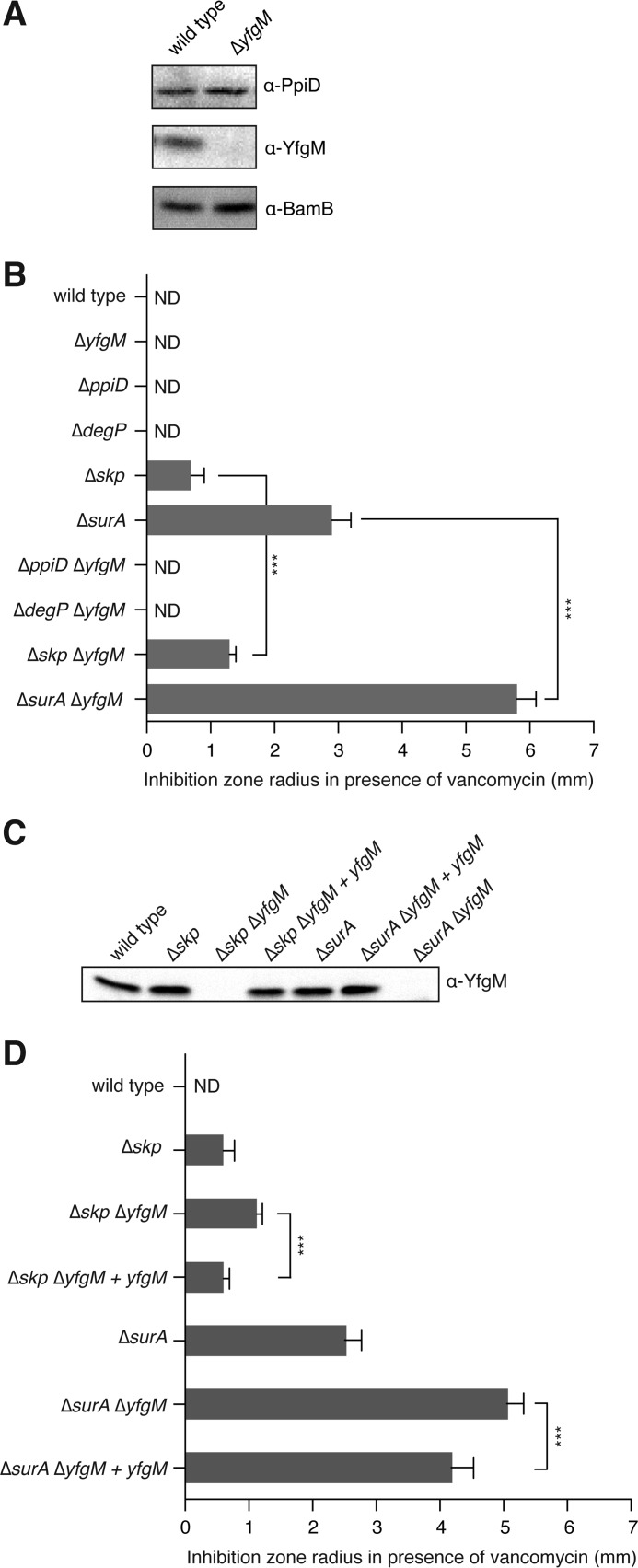

Based on the fact that YfgM has a large periplasmic domain (23, 25) and that it associates with PpiD (see Ref. 23 and this study) we reasoned that it might play a role in the periplasmic network that includes SurA, Skp, DegP, PpiD, and FkpA (for review, see Refs. 10, 36, and 37). This network chaperones β-barrel proteins from the Sec translocon to the β-barrel assembly machine (BAM) in the outer membrane. SurA and Skp are the major players in the network, and strains lacking them are defective in their ability to traffic β-barrel proteins. As a result, the integrity of the outer membrane is compromised, and the cells are hypersensitive to antibiotics such as vancomycin and novobiocin (38–41). To determine if YfgM is also part of this network, we analyzed a ΔyfgM strain in an antibiotic susceptibility assay. The strain was obtained by replacing the open reading frame of yfgM with a kanamycin resistance gene. To exclude the possibility of a polar effect on the expression of bamB (which is also involved in outer membrane biogenesis and adjacent to yfgM), we verified that the levels of BamB remained constant by Western blotting (Fig. 3A). When we tested ΔyfgM in the antibiotic susceptibility disc assay, we did not observe a zone of growth inhibition around filter paper discs containing 30 μg of vancomycin (Fig. 3B). Thus we conclude that there is no obvious defect in the outer membrane of the ΔyfgM strain. Similar results were obtained for the ΔdegP and ΔppiD strains (Fig. 3B), which are considered to be minor players in this periplasmic chaperone network. In contrast, ΔsurA and Δskp show susceptibility to vancomycin, indicating that the outer membrane is compromised in these strains (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Deletion of yfgM in combination with either surA or skp causes increased sensitivity to vancomycin. A, Western blot showing that deletion of yfgM has no effect on the levels of BamB. B, the integrity of the outer membrane in wild type and deletion strains was assayed by measuring the inhibition zone radius (mm) when a filter disc containing 30 μg of vancomycin was placed on a lawn of cells. Each bar represents an average of at least three biological replica. C, immunoblot of wild type, deletion, and complemented strains illustrating the protein levels of YfgM. D, ΔsurA ΔyfgM and Δskp ΔyfgM strains were complemented using the pSC-yfgM plasmid, and the integrity of the outer membrane was assayed by measuring the inhibition zone radius (mm). Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed Student's test assuming unequal variance. Three stars indicate a probability of p < 0.001. ND, not detected.

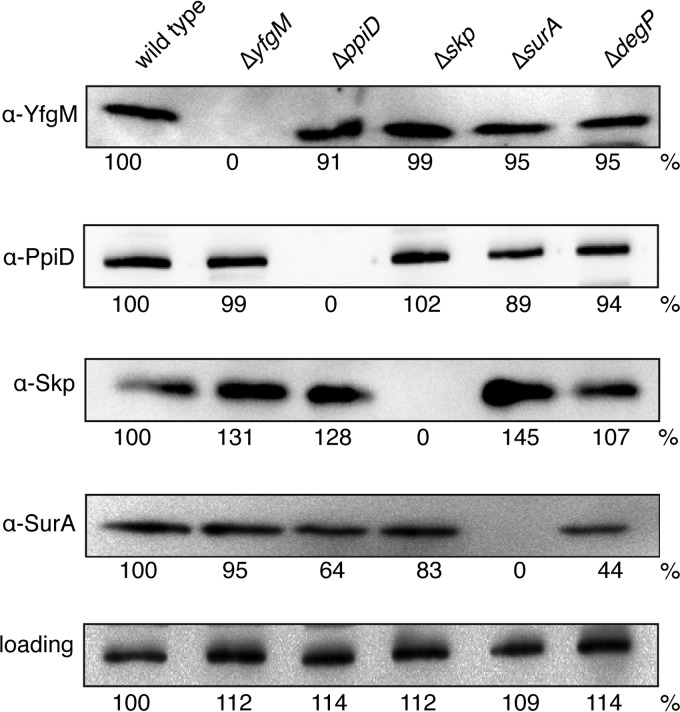

To determine if the lack of a phenotype in the ΔyfgM strain was caused by compensatory up-regulation of other periplasmic chaperones, we monitored the steady state levels of PpiD, Skp, and SurA by immunoblotting (Fig. 4). We detected a slight up-regulation of Skp, which might partly explain why the susceptibility to antibiotics was weak. A similar level of up-regulation of Skp was also observed in the ΔppiD and ΔsurA strains.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the steady state levels of periplasmic chaperones. Wild type cells and single gene deletions were separated by 14% SDS-PAGE then immunoblotted. Signal intensities were quantified and normalized relative to the wild type protein.

Because periplasmic chaperones often have overlapping functions, their involvement in a network can only be discerned by deleting them in combination. For example, the simultaneous deletion of ppiD and degP results in a temperature-sensitive phenotype (37), and deletion of surA and either skp or degP results in lethality (42). We engineered ΔppiD ΔyfgM, ΔdegP ΔyfgM, Δskp ΔyfgM, and ΔsurA ΔyfgM double deletions and again probed outer membrane integrity with vancomycin. All strains were obtained, indicating that the double deletions were viable. In the antibiotic susceptibility disc assays the ΔppiD ΔyfgM and ΔdegP ΔyfgM strains were insensitive to vancomycin, but the ΔsurA ΔyfgM strain, and to a lesser extent the Δskp ΔyfgM strain, were more sensitive to vancomycin than the respective single deletions (Fig. 3B). These same phenotypes were observed using novobiocin, indicating that they are not limited to the action of vancomycin (data not shown).

The vancomycin sensitivity of the Δskp ΔyfgM double deletion could be reverted to that of the Δskp single deletion by expressing yfgM from its native promoter in a low copy plasmid (Fig. 3, C and D). Plasmid expression of yfgM could partially revert the phenotype of the ΔsurA ΔyfgM double deletion to that of the ΔsurA mutant (Fig. 3, C and D). At this stage it is not clear why complementation was not completely effective in this strain. Taken together, the data indicate that deletion of yfgM further compromised the integrity of the outer membrane in both the ΔsurA and Δskp backgrounds. This observation suggests that the physiological role of YfgM overlaps to some degree with SurA and Skp.

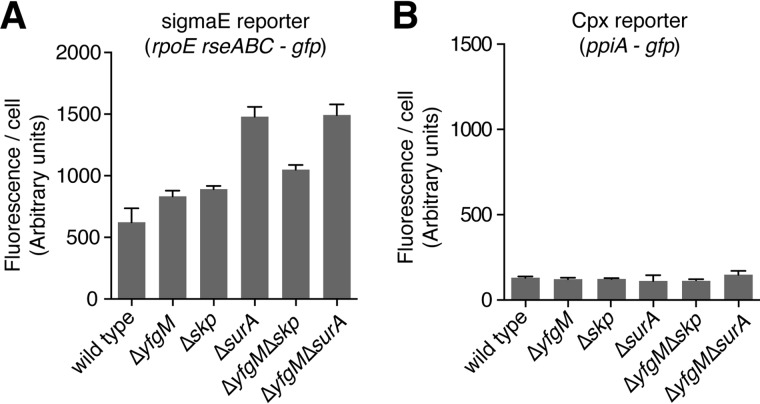

Loss of YfgM Exacerbates the σE-Dependent Envelope Stress Response in a Δskp Deletion Strain

Deletion of periplasmic chaperones can result in an extracytoplasmic stress response. In E. coli there are two major systems for detecting extracytoplasmic stresses, the σE-dependent envelope stress response and the CpxAR two-component system (for review, see Refs. 43–46). Both systems trigger a signaling cascade that results in the up-regulation of envelope chaperones and/or proteases. We first tested for a σE-dependent envelope stress response using a plasmid containing the promoter region for the rpoE rseABC operon adjacent to the gene encoding the GFP (30). Thus σE activity was inferred from whole cell fluorescence. In the ΔyfgM strain, the expression of GFP from the rpoE rseABC promoter was slightly higher than the wild type strain (Fig. 5A). The Δskp ΔyfgM double deletion also resulted in a slightly stronger σE-dependent envelope stress response than the Δskp deletion. Deletion of yfgM in the ΔsurA background did not affect the strength of the σE response, which was already quite high in the ΔsurA deletion strain (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Deletion of yfgM in combination with skp leads to increased envelope stress. The transcription of rpoE rseABC (σE-dependent envelope stress response) (A) and ppiA (Cpx regulon) (B) were monitored using transcriptional fluorescence reporters (30) to evaluate envelope stress in deletion strains. All fluorescence data were normalized by the optical density at 600 nm and expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units per cell. Each data point represents the average of at least three biological replica.

We also tested for an envelope stress response through the CpxAR two-component system using a plasmid containing the promoter region for ppiA (a periplasmic peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase). We did not detect elevated fluorescence levels in any of the deletion strains, indicating that the Cpx extracytoplasmic stress response was not activated by perturbations to the trafficking of β-barrel proteins (Fig. 5B). It is worth noting that others have detected a response in a surA deletion strain using a cpxP-lacZ reporter construct (37). We did not resolve this discrepancy, as it was not the main point of the study.

Our analyses of the outer membrane integrity and extracytoplasmic stress responses indicate that loss of yfgM exacerbates the phenotypes of both ΔsurA and Δskp strains. These observations strongly suggest a role for YfgM in the periplasmic chaperone network that traffics β-barrel proteins from the Sec translocon to the BAM.

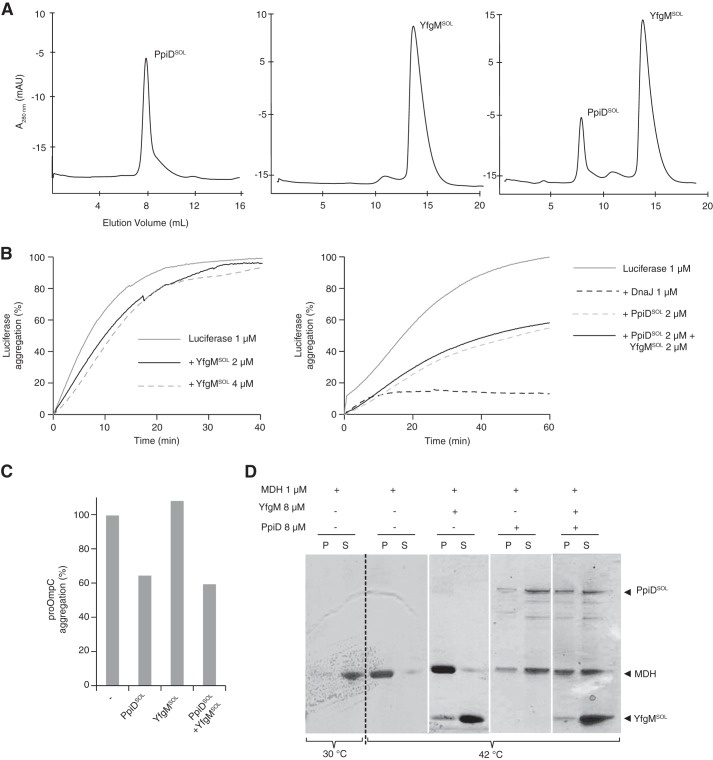

PpiD Can Prevent Protein Aggregation but YfgM Cannot

How might YfgM assist β-barrel proteins as they exit from the Sec translocon? One obvious possibility is that YfgM delays aggregation of the polypeptide as it enters the periplasm, as shown for PpiD (37). To explore this possibility we carried out in vitro aggregation assays in the presence of a soluble version of YfgM (YfgMSOL). For comparison, we also expressed and purified a soluble version of PpiD (PpiDSOL). Both YfgMSOL and PpiDSOL showed mono-disperse profiles when analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography, indicating that the domains were folded (Fig. 6A). The size-exclusion chromatography traces also indicated that both domains formed homo-oligomeric species; however, we are not sure if these states are physiologically relevant. We then tested whether YfgMSOL + PpiDSOL could prevent aggregation of three test proteins, proOmpC, malate dehydrogenase, and luciferase. When the test proteins were denatured either chemically or by heat treatment and diluted into buffer, they aggregated (Fig. 6, B–D). For all three proteins, the aggregation could be inhibited by a molar excess of PpiDSOL but not of YfgMSOL. Simultaneous addition of both YfgMSOL and PpiDSOL did not show a cooperative effect on aggregation of the test proteins; however, this was not surprising, as the two domains do not interact in vitro (Fig. 6A). Taken together, the data indicate that YfgM does not prevent protein aggregation; thus its role at the translocon may differ from that of PpiD.

FIGURE 6.

YfgMSOL cannot prevent protein aggregation activity in vitro but PpiDSOL can. A, purified PpiDSOL, YfgMSOL, or both were analyzed by size exclusion chromatography. mAU, milliabsorbance units. B, luciferase aggregation protection assay. Optical densities were measured at 320 nm, and the percentage values were normalized to the luciferase aggregation obtained in the absence of added chaperones. Left panel, a representative plot of a luciferase aggregation protection assay is shown with chemically denatured luciferase 1 μm alone (gray line) or in the presence of YfgMSOL 2 μm (black line) or 4 μm (gray dashed line). Right panel, a representative plot of a luciferase aggregation protection assay is shown with chemically denatured luciferase 1 μm alone (gray line) or in the presence of DnaJ 1 μm (black dashed line), PpiDSOL 2 μm (gray dashed line) or both PpiDSOL 2 μm and YfgMSOL 2 μm (black line). C, aggregation of denatured proOmpC (2 μm) at 25 °C after a 50-min reaction in the presence of 8 μm PpiDSOL, 8 μm YfgMSOL, and both 8 μm PpiDSOL and 16 μm YfgMSOL or in the absence of chaperone (−). The percentage of aggregation was normalized to proOmpC aggregation obtained when no chaperone was added. D, malate dehydrogenase (MDH) aggregation protection assay. Interaction of native malate dehydrogenase (with PpiDSOL, YfgMSOL, or both as indicated above the gel. Samples were incubated at 42 °C and centrifuged to analyze the resulting supernatant (S) and pellets (P) containing malate dehydrogenase and associated proteins aggregates by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue.

DISCUSSION

Here we show that YfgM, an inner membrane protein with no annotated function, is an ancillary subunit of the Sec translocon. Initially we showed that YfgM and PpiD were physically associated with the translocon when solubilized with digitonin and analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation and two-dimensional BN-/SDS-PAGE. Both YfgM and PpiD contain a single transmembrane helix and a large periplasmic domain (23, 25, 26); thus it seems likely that the periplasmic domains reside in close proximity to the exit of the translocon. Curiously, our analysis also indicated that there was a population of YfgM-PpiD that was independent from SecYEG. It remains to be determined if this is a distinct population or whether YfgM-PpiD cycles on and off the translocon.

The Sec translocon interacts with a number of ancillary modules, such as SecA, SecDF-YajC, and YidC (19, 47–51), and it is not clear if they are present simultaneously. Unfortunately we were unable to determine whether SecA and SecDF-YajC were associated with the translocon at the same time as YfgM-PpiD, as antisera were not available. We were able to confirm that YidC associated with the translocon, but notably, it was not detected on those translocons that were associated with YfgM-PpiD. This may be because digitonin does not solubilize all supercomplexes or that the Sec translocon cannot associate with YfgM-PpiD and YidC simultaneously.

The Sec translocon has been extensively studied in E. coli, so why hasn't YfgM been previously detected as an ancillary module? Most other studies (including our own) have solubilized proteins with detergents such as n-dodecyl-B-D-maltoside (DDM) or β-octyl glucoside and have not detected the association (21–23). Thus we reason that it is only possible to co-purify YfgM with the Sec translocon if digitonin is used as a detergent, as we have done here. This observation is consistent with a large body of work that has shown that respiratory supercomplexes are sensitive to all detergents except digitonin (52).

What role does YfgM play at the translocon? Because YfgM physically interacts with PpiD (23), we reasoned that it might have a similar function. PpiD facilitates the release of β-barrel proteins into the periplasm (24) by preventing premature aggregation (37). The β-barrel proteins are then chaperoned across the periplasmic space by SurA, Skp, and DegP and delivered to the BAM complex in the outer membrane (10, 36, 37). Evidence that YfgM is involved in this network was primarily obtained by monitoring outer membrane integrity in strains lacking yfgM. We noted that strains lacking surA and skp became more sensitive to vancomycin and novobiocin when yfgM was deleted. Thus, indicating that the integrity of the outer membrane was further compromised in the absence of YfgM. Notably we also detected an exacerbated σE extracytoplasmic stress response when yfgM was deleted in a Δskp background. We did not detect an exacerbated σE extracytoplasmic stress response when yfgM was deleted in the ΔsurA background. This observation was surprising as the phenotype of the ΔsurA ΔyfgM strain was more pronounced than the ΔsurA strain in the antibiotic sensitivity assays. A possible explanation might be that the σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response was already fully activated in the ΔsurA strain. Taken together, the simplest interpretation of these data is that the physiological role of YfgM overlaps with SurA and Skp. This role is different to that of PpiD as we noted differences between YfgM and PpiD during our characterization.

Further work is required to understand the molecular role of YfgM at the Sec translocon. One possibility is that it acts as a docking point for SurA and Skp. Both of these proteins engage substrate proteins near the translocon (53); however, the molecular details of this engagement are vague. An interesting precedence for the involvement of a docking protein at the Sec translocon can be found in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis thaliana (54), where AtTPR7 mediates docking of Hsp70/90. Although AtTPR7 is unrelated to YfgM, both proteins contain tetratrico-peptide repeat (TPR) domains (for review, see Ref. 55), which are often involved in protein-protein interactions. Another possible role for YfgM may be in the acid stress response, as E. coli cells are more susceptible to acid stress when YfgM is overexpressed (56). The acid stress response involves a number of periplasmic chaperones that refold SurA, DegP, FkpA, and PpiD after acid damage (57). All of these potential roles warrant further exploration, as they will provide a better understanding of YfgM and its role in protein secretion through the Sec translocon.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Marcelo Sousa, Tom Silhavy, and Jan Willem de Gier for strains and antisera.

This work was supported by a grant from the Swedish Research Council (to D. O. D.).

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- BN

- blue native

- BAM

- β-barrel assembly machine

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dalbey R. E., Kuhn A. (2012) Protein traffic in Gram-negative bacteria: how exported and secreted proteins find their way. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 1023–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Economou A. (2000) Bacterial protein translocase: a unique molecular machine with an army of substrates. FEBS Lett. 476, 18–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park E., Rapoport T. A. (2012) Mechanisms of Sec61/SecY-mediated protein translocation across membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 21–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rapoport T. A. (2007) Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature 450, 663–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. du Plessis D. J., Nouwen N., Driessen A. J. (2011) The Sec translocase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 851–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lycklama A Nijeholt J. A., Driessen A. J. (2012) The bacterial Sec-translocase: structure and mechanism. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 1016–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dautin N., Bernstein H. D. (2007) Protein secretion in gram-negative bacteria via the autotransporter pathway. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 89–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leyton D. L., Rossiter A. E., Henderson I. R. (2012) From self-sufficiency to dependence: mechanisms and factors important for autotransporter biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 213–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okuda S., Tokuda H. (2011) Lipoprotein sorting in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 239–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rigel N. W., Silhavy T. J. (2012) Making a β-barrel: assembly of outer membrane proteins in Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 189–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruiz N., Kahne D., Silhavy T. J. (2006) Advances in understanding bacterial outer-membrane biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Egea P. F., Stroud R. M. (2010) Lateral opening of a translocon upon entry of protein suggests the mechanism of insertion into membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17182–17187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsukazaki T., Mori H., Fukai S., Ishitani R., Mori T., Dohmae N., Perederina A., Sugita Y., Vassylyev D. G., Ito K., Nureki O. (2008) Conformational transition of Sec machinery inferred from bacterial SecYE structures. Nature 455, 988–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van den Berg B., Clemons W. M., Jr., Collinson I., Modis Y., Hartmann E., Harrison S. C., Rapoport T. A. (2004) X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel. Nature 427, 36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zimmer J., Nam Y., Rapoport T. A. (2008) Structure of a complex of the ATPase SecA and the protein-translocation channel. Nature 455, 936–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Samuelson J. C., Chen M., Jiang F., Möller I., Wiedmann M., Kuhn A., Phillips G. J., Dalbey R. E. (2000) YidC mediates membrane protein insertion in bacteria. Nature 406, 637–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scotti P. A., Urbanus M. L., Brunner J., de Gier J. W., von Heijne G., van der Does C., Driessen A. J., Oudega B., Luirink J. (2000) YidC, the Escherichia coli homologue of mitochondrial Oxa1p, is a component of the Sec translocase. EMBO J. 19, 542–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sachelaru I., Petriman N. A., Kudva R., Kuhn P., Welte T., Knapp B., Drepper F., Warscheid B., Koch H. G. (2013) YidC occupies the lateral gate of the SecYEG translocon and is sequentially displaced by a nascent membrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 16295–16307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duong F., Wickner W. (1997) The SecDFyajC domain of preprotein translocase controls preprotein movement by regulating SecA membrane cycling. EMBO J. 16, 4871–4879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsukazaki T., Mori H., Echizen Y., Ishitani R., Fukai S., Tanaka T., Perederina A., Vassylyev D. G., Kohno T., Maturana A. D., Ito K., Nureki O. (2011) Structure and function of a membrane component SecDF that enhances protein export. Nature 474, 235–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duong F., Wickner W. (1997) Distinct catalytic roles of the SecYE, SecG, and SecDFyajC subunits of preprotein translocase holoenzyme. EMBO J. 16, 2756–2768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boy D., Koch H. G. (2009) Visualization of distinct entities of the SecYEG translocon during translocation and integration of bacterial proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1804–1815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maddalo G., Stenberg-Bruzell F., Götzke H., Toddo S., Björkholm P., Eriksson H., Chovanec P., Genevaux P., Lehtiö J., Ilag L. L., Daley D. O. (2011) Systematic analysis of native membrane protein complexes in Escherichia coli. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1848–1859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Antonoaea R., Fürst M., Nishiyama K., Müller M. (2008) The periplasmic chaperone PpiD interacts with secretory proteins exiting from the SecYEG translocon. Biochemistry 47, 5649–5656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Toddo S., Söderström B., Palombo I., von Heijne G., Nørholm M. H., Daley D. O. (2012) Application of split-green fluorescent protein for topology mapping membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 21, 1571–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dartigalongue C., Raina S. (1998) A new heat-shock gene, ppiD, encodes a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase required for folding of outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 17, 3968–3980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baba T., Ara T., Hasegawa M., Takai Y., Okumura Y., Baba M., Datsenko K. A., Tomita M., Wanner B. L., Mori H. (2006) Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stenberg F., Chovanec P., Maslen S. L., Robinson C. V., Ilag L. L., von Heijne G., Daley D. O. (2005) Protein complexes of the Escherichia coli cell envelope. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34409–34419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zaslaver A., Bren A., Ronen M., Itzkovitz S., Kikoin I., Shavit S., Liebermeister W., Surette M. G., Alon U. (2006) A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat. Methods 3, 623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Daley D. O., Rapp M., Granseth E., Melén K., Drew D., von Heijne G. (2005) Global topology analysis of the Escherichia coli inner membrane proteome. Science 308, 1321–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rapp M., Drew D., Daley D. O., Nilsson J., Carvalho T., Melén K., De Gier J. W., Von Heijne G. (2004) Experimentally based topology models for E. coli inner membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 13, 937–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cajo G. C., Horne B. E., Kelley W. L., Schwager F., Georgopoulos C., Genevaux P. (2006) The role of the DIF motif of the DnaJ (Hsp40) co-chaperone in the regulation of the DnaK (Hsp70) chaperone cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12436–12444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perrody E., Cirinesi A. M., Desplats C., Keppel F., Schwager F., Tranier S., Georgopoulos C., Genevaux P. (2012) bacteriophage-encoded J-domain protein interacts with the DnaK/Hsp70 chaperone and stabilizes the heat-shock factor δ32 of Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 8, e1003037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bordes P., Cirinesi A. M., Ummels R., Sala A., Sakr S., Bitter W., Genevaux P. (2011) SecB-like chaperone controls a toxin-antitoxin stress-responsive system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8438–8443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ricci D. P., Silhavy T. J. (2012) The Bam machine: a molecular cooper. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 1067–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matern Y., Barion B., Behrens-Kneip S. (2010) PpiD is a player in the network of periplasmic chaperones in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 10, 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu A., Tran L., Becket E., Lee K., Chinn L., Park E., Tran K., Miller J. H. (2010) Antibiotic sensitivity profiles determined with an Escherichia coli gene knockout collection: generating an antibiotic bar code. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 1393–1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lazar S. W., Kolter R. (1996) SurA assists the folding of Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1770–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rouvière P. E., Gross C. A. (1996) SurA, a periplasmic protein with peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity, participates in the assembly of outer membrane porins. Genes Dev. 10, 3170–3182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schwalm J., Mahoney T. F., Soltes G. R., Silhavy T. J. (2013) Role for Skp in LptD Assembly in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 195, 3734–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rizzitello A. E., Harper J. R., Silhavy T. J. (2001) Genetic evidence for parallel pathways of chaperone activity in the periplasm of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6794–6800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alba B. M., Gross C. A. (2004) Regulation of the Escherichia coli δ-dependent envelope stress response. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Raivio T. L., Silhavy T. J. (2001) Periplasmic stress and ECF δ factors. Annu. Rev Microbiol. 55, 591–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ruiz N., Silhavy T. J. (2005) Sensing external stress: watchdogs of the Escherichia coli cell envelope. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 122–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rowley G., Spector M., Kormanec J., Roberts M. (2006) Pushing the envelope: extracytoplasmic stress responses in bacterial pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gardel C., Benson S., Hunt J., Michaelis S., Beckwith J. (1987) secD, a new gene involved in protein export in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169, 1286–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gardel C., Johnson K., Jacq A., Beckwith J. (1990) The secD locus of E. coli codes for two membrane proteins required for protein export. EMBO J. 9, 4205–4206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fang J., Wei Y. (2011) Expression, purification and characterization of the Escherichia coli integral membrane protein YajC. Protein Pept. Lett. 18, 601–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nouwen N., Driessen A. J. (2002) SecDFyajC forms a heterotetrameric complex with YidC. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 1397–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kato Y., Nishiyama K., Tokuda H. (2003) Depletion of SecDF-YajC causes a decrease in the level of SecG: implication for their functional interaction. FEBS Lett. 550, 114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schägger H. (2002) Respiratory chain supercomplexes of mitochondria and bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1555, 154–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ieva R., Tian P., Peterson J. H., Bernstein H. D. (2011) Sequential and spatially restricted interactions of assembly factors with an autotransporter β domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E383–E391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schweiger R., Müller N. C., Schmitt M. J., Soll J., Schwenkert S. (2012) AtTPR7 is a chaperone-docking protein of the Sec translocon in Arabidopsis. J. Cell Sci. 125, 5196–5207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cerveny L., Straskova A., Dankova V., Hartlova A., Ceckova M., Staud F., Stulik J. (2013) Tetratricopeptide repeat motifs in the world of bacterial pathogens: role in virulence mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 81, 629–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Westphal K., Langklotz S., Thomanek N., Narberhaus F. (2012) A trapping approach reveals novel substrates and physiological functions of the essential protease FtsH in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 42962–42971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang M., Lin S., Song X., Liu J., Fu Y., Ge X., Fu X., Chang Z., Chen P. R. (2011) A genetically incorporated crosslinker reveals chaperone cooperation in acid resistance. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Akiyama Y., Ito K. (1990) SecY protein, a membrane-embedded secretion factor of E. coli, is cleaved by the ompT protease in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 167, 711–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]