Abstract

Background

Healthcare disparities have afflicted the healthcare industry for decades and there have been many campaigns in recent years to identify and eliminate disparities. The purpose of this study was to identify disparities in the lung cancer population of a single community cancer center and to report the results in accordance with industry goals.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of data on non-small cell lung cancer patients recorded in the Christiana Care Tumor Registry (CCTR) in Delaware. Gender, age, race, socioeconomic status and insurance status were used as potential variables in identifying disparities.

Results

We found no significant disparities between sexes, race or patients who were classified as having socioeconomic status 1–3. There was a lower survival rate associated with having the poorest socioeconomic status and in patients who used Medicare. Uninsured patients had the best survival outcomes and patients with Medicare had the poorest survival outcomes.

Conclusion

Although we have closed the gap on sex and racial disparities, there remains a difference in survival outcomes across socioeconomic classes and insurance types.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, thoracic surgery, Medicare, Medicaid, socioeconomic status, indigent, uninsured

Introduction

Health disparities have been well documented in all areas of healthcare since the 1980’s. There have been many campaigns in recent years to eliminate these disparities. For example, in 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program with the purpose of funding community coalitions focused on reducing disparities in six areas of cancer [1]. Similarly, the Healthy People campaigns and the American Cancer Society 2015 Challenge Goals charged the healthcare community with developing innovative ways to measure, track and decrease disparities in healthcare [2, 3]. However, despite improvements, healthcare disparities are still a major cause for concern.

Lung cancer in particular, which remains the leading cause of cancer related death in the United States, is a major focus for measuring disparities as discussed in several studies [4–6]. For instance, it has been documented that African-Americans, Hispanics and those with low socioeconomic status have higher incidence and mortality rates of lung cancer when compared to non-Hispanic whites and those with high socioeconomic status [7]. Furthermore, analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data shows that those from lower SES and minorities are more likely to be diagnosed with late stage cancers, including lung cancer [8, 9]. Finally, a review by Lynne et al provides supporting evidence from multiple studies showing patients from socioeconomically poor environments are less likely to receive lung cancer treatment of any kind [10].

One of the overarching goals for eliminating health disparities has been to put in place institutional and state level data collection systems to measure initial health status and track changes over time [11]. In 1998, the Christiana Care Tumor Registry (CCTR) was created to assess the impact that the Christiana Care Health System (CCHS) and later the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center (HFGCC), an NCI Selected Community Cancer Center Program (NCCCP), has on the cancer population of Delaware. The purpose of this study is to specifically evaluate the data collected for lung cancer patients in the CCTR to gauge our progress in eliminating healthcare disparities in this patient population.

Methods

After approval from the Christiana Care institutional review board, data was obtained from the Christiana Care Tumor Registry (CCTR). The CCTR included information regarding patient demographics, diagnoses, stage at diagnosis, histology, treatment types, surgical procedures, payment types, vital status and survival times. Excluding out-of-state patients, this study involved Delaware residents 18 years or older diagnosed with lung cancer at CCHS between the years of 1998 and 2012. The data was limited to patients with a final diagnosis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), which included adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, bronchial alveolar carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Race in the NSCLC population was divided into three groups: Non-Hispanic Whites, African-Americans and Other. The group “other” was excluded from the analysis due to the small patient population. Ethnicity other than non-Hispanic was also excluded due to a small patient population. Age at initial diagnosis was initially divided into 20 year incremental groups as follows: < 20, 20–39, 40–59, 60–79, 80–99, & 100+. However, after initial evaluation it was clear that the statistical analysis would be inaccurate due to small populations in some of the groups, so they were further grouped as follows: < 60, 60–79 and 80+.

Staging at initial diagnosis in the CCTR was based on clinical staging and was recorded in the database as follows: OC, 0, 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 4, and 99. Those with a stage of 99 were excluded from the study, as they were found to have something other than NSCLC (i.e. carcinoid). Due to small patient populations in some of the groups, occult carcinoma (OC) and stage 0 were excluded and the remaining stages were further combined so that the final stages included 1, 2, 3 and 4, with stages 1 and 2 representing early stages and stages 3 and 4 representing late stages.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was determined by correlating patient zip codes with census tract data. The “Census 2010 ZIP Code to Census Tract Interactive Ranking and Equivalence Table” by Proximity was used to generate a list of every census tract within each Delaware ZIP code[12]. First, we used table B17001 entitled “Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months” from the 2011 summary file produced by the American Community Survey, to determine the percentage of the population in each census tract who fell below the poverty line[13]. Then we averaged the population percentages of each census tract within each ZIP code to create a better representation of poverty level for each ZIP code. ZIP codes 19809 and 99999 contained census tracts delineated as large bodies of water and were excluded from the ZIP code average as they were lacking population demographics. SES was then categorized into four groups corresponding to the area poverty levels: SES 1 (<5%), 2 (5–10%), 3 (10–20%) and 4 (>20%), where SES 1 represents the group with the higher status consisting of less than 5 percent of impoverished people compared with SES 4 which represents the group with the lowest status with greater than 20 percent of impoverished people.

Type of payment (insurance) was also recorded in the CCTR and was another parameter that we used for comparison. There were 12 types of payment recorded in the CCTR as follows: Health Maintenance Organization/Preferred Provider Organization (HMO/PPO), Insurance Not Otherwise Specified (Insurance NOS), Medicaid, Medicare, Medicare through a managed care plan, Medicare with Medicaid, Medicare with supplement, Military, Tricare (military), Uninsured, Unknown and Veterans Affairs. Due to variations in population size, the final grouped designations were as follows: Private, Medicaid, Medicare and Uninsured. Private includes HMO/PPO and Insurance NOS. Medicare includes Medicare through a managed health care plan, Medicare with Medicaid and Medicare with supplement. Those with unknown payer status and the military group, which includes military, Tricare and Veterans Affairs, were excluded due to small population. Of note, we identified a small number patients who were 65 years of age and older who were miscoded as having a payment method other than Medicare. Their payment status was verified with the database administrator and was either corrected or they were excluded from the survival analysis if the information could not be found or validated.

The data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20. The variables listed above were cross-tabulated and comparisons were made using the Pearson chi-square test with a p-value of less than 0.05 interpreted as having significance. The survival data for all variables accept that of payment type (insurance) was generated using life tables and the Kaplan-Meier method. The log rank test was used to test significance between factor levels and strata used for comparing survival data. Survival data for payment type (insurance) was generated using the Cox Regression model due to dissimilarities in age distribution between these groups.

Results

Demographics

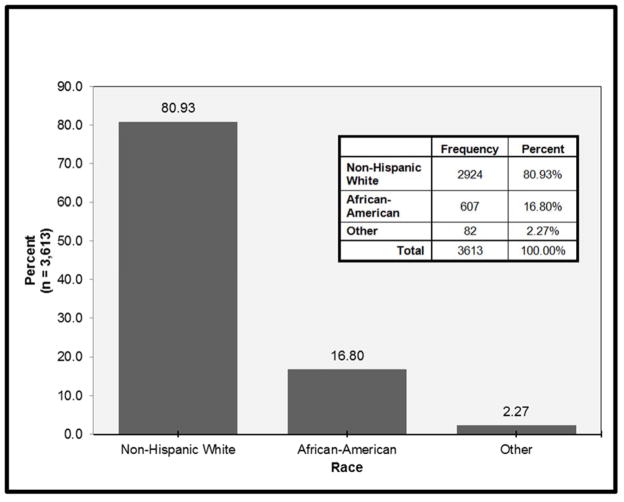

There were a total of 4,860 patients recorded in the Christiana Care Tumor Registry (CCTR) from 1998 to 2013. Of those, 3,613 (74.3%) patients were diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer. Figure I illustrates the distribution of the NSCLC population by race: 80.9% of the NSCLC patients were Non- Hispanic Whites, 16.8% were African-Americans and 2.27% were other races. Due to the poor representation of other races, they were excluded from the remainder of the results. Table I is a cross-tabulation presenting demographic information across multiple categorical variables in the NSCLC population. There was no significant difference in the distribution of sex between races with male and 50% female for both Non-Hispanic Whites and African-Americans (p= 0.945). The median age distribution at initial diagnosis was younger for African-Americans compared with Non-Hispanic Whites having a median age of 64 and 70 years respectively (p <0.001; Table II).

Figure I.

Distribution of non-small cell lung cancer patients subdivided by race. There were a total of 3,613 patients in the database.

Table I.

Cross-Tabulation of NSCLC Patients by Multiple Categorical Variables

| n=3531 | Race | Total | Missing | p-valuea (sig < 0.05) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | African- American | |||||

| Sex N (%) | Female | 1440 (49) | 298 (49) | 1738 (49) | 0 | 0.945 |

| Male | 1484 (51) | 309 (51) | 1793 (51) | |||

| Total | 2924 | 607 | 3531 | |||

| Age Group N (%) | < 60 | 611 (21) | 209 (34) | 820 (23) | 0 | <0.001 |

| 60 – 79 | 1817 (62) | 341 (56) | 2158 (61) | |||

| 80+ | 496 (17) | 57 (9) | 553 (16) | |||

| Total | 2924 | 607 | 3531 | |||

| SES N (%) | 1 (most wealth) | 387 (13) | 21 (3) | 408 (12) | 10 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1125 (39) | 119 (20) | 1244 (35) | |||

| 3 | 1368 (47) | 222 (37) | 1590 (45) | |||

| 4 (least wealth) | 37 (1) | 242 (40) | 279 (8) | |||

| Total | 2917 | 604 | 3521 | |||

| Insurance Type N (%) | Private Insurance | 719 (26) | 158 (27) | 877 (29) | 158 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 118 (4) | 83 (14) | 201 (6) | |||

| Medicare | 1929 (69) | 326 (56) | 2255 (64) | |||

| Uninsured | 21 (1) | 19 (3) | 40 (1) | |||

| Total | 2787 | 586 | 3373 | |||

| Stage Combined N (%)b | 1 | 802 (28) | 141 (24) | 943 (27) | 98 | 0.015 |

| 2 | 218 (8) | 31 (5) | 249 (7) | |||

| 3 | 736 (26) | 174 (30) | 910 (27) | |||

| 4 | 1090 (38) | 241 (41) | 1331 (39) | |||

| Total | 2846 | 587 | 3433 | |||

SES = Socioeconomic Status

0 cells (0.0%) have expected count less than 5.

Patients were grouped for staging in the following way: 1 = 1a,1b; 2 = 2a, 2b; 3 = 3a,3b; 4 = 4. See methods for more detail

TABLE II.

Age Distribution at Initial Diagnosis by Race

| N | Mean Age | Median Age | Std. Deviation | Siga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | 2924 | 68.77 | 70.00 | 11.037 | <0.001 |

| African-American | 607 | 63.86 | 64.00 | 11.597 | |

| Total | 3531 | 67.92 | 69.00 | 11.286 |

Sig = Significance. Calculated using ANOVA Between Groups (combined). Value <0.05 is significant

Socioeconomic Status

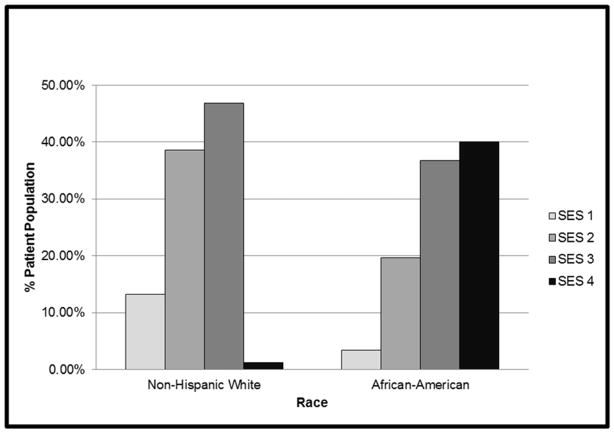

Table I reveals that over all, greater than 50% of the patients in the study population were in the 2 lowest socioeconomic status categories. However, further analysis revealed a significant difference in distribution of patients by SES between African-Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites (p <0.001). Figure II shows that more than 50% of the Non-Hispanic Whites fell into the wealthiest SES categories when grouped together, whereas close to 80% of the African-American population fell into the poorest SES categories with the greatest number in SES category 4. However, the data does point out that the majority of Non-Hispanic Whites in this population fell into SES category 3 when compared individually. This is also illustrated in Figure II.

Figure II.

Race subdivided by socioeconomic status. SES 1 represents the “wealthiest” group, whereas SES 4 represents the “poorest” group.

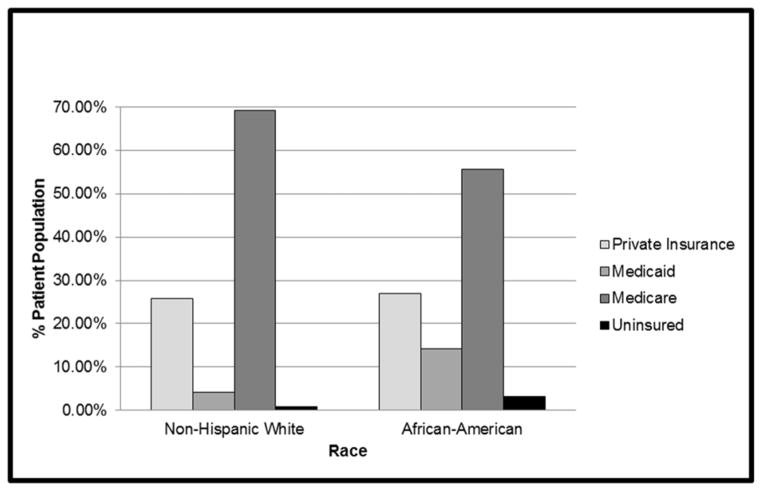

Type of Insurance

Table I reveals that over all, the majority of patients in the database were covered under Medicare as their primary source of payment. However, further analysis revealed a significant difference in distribution of patients by insurance type between African-Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites (p <0.001). The smallest numbers of patients in the database were uninsured for both races. Roughly the same percentages of both races were privately insured. There was a significantly greater percent of African-Americans who were covered under Medicaid compared to Non-Hispanic Whites as visualized in Figure III.

Figure III.

Race subdivided by insurance type.

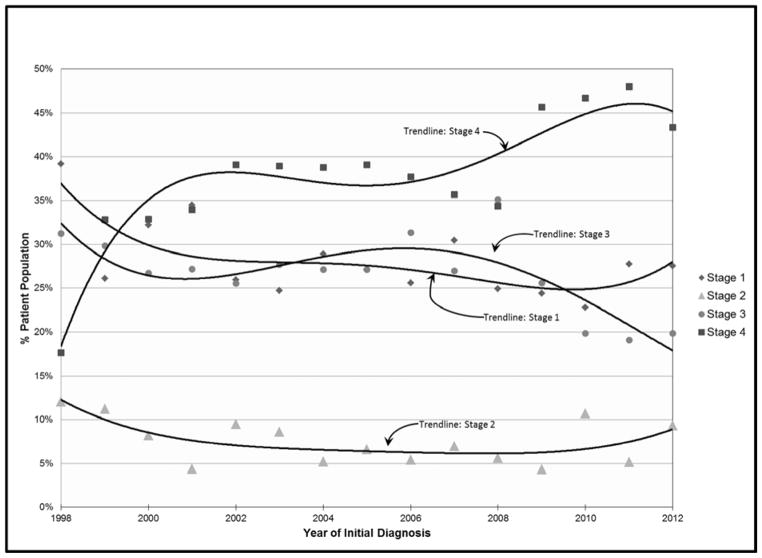

Stage Distribution

The overall distribution of patients by stage at initial diagnosis is pictured in Figure IV. There were a total of 98 patients who were missing staging information and were excluded from the analysis. The trend in the diagram reveals that most of the time, stage IV diagnoses predominated the patient population and stage II carried the least percentage of the population (p <0.001). As cross tabulated in table I, this was true for both races.

Figure IV.

Percentage of the population subdivided by initial stage and trended over time. The trendlines are of the polynomial type to the 4th order.

Survival Analysis

Survival data is represented in Table III. Overall, there was no significant difference in survival times between races (log rank score 0.246) with the median survival time being 10–12 months (95% CI 30.16, 33.69). However, there were significant differences in survival time when looking at overall socioeconomic status. Overall, SES 1–3 had longer median survival times when compared to SES 4 (log rank scores <0.05). There were no significant differences in median survival times between SES 1–3.

TABLE III.

Median Survival Times

| Median Survival Time | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval | Log Rank Scorec | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||||||

| Raceb Overall | A | 10.000 | 0.691 | 8.645 | 11.355 | 0.246 | ||||

| W | 12.000 | 0.418 | 11.181 | 12.819 | ||||||

| SESa | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| SESa Overall | 1 | 12.000 | 0.988 | 10.064 | 13.936 | 0.598 | 0.222 | 0.015 | ||

| 2 | 12.000 | 0.764 | 10.502 | 13.498 | 0.344 | 0.019 | ||||

| 3 | 11.000 | 0.516 | 9.988 | 12.012 | 0.071 | |||||

| 4 | 9.000 | 1.033 | 6.975 | 11.025 | ||||||

|

SESa Stratified by Raceb |

1 | A | 14.000 | 1.980 | 10.120 | 17.880 | 0.485 | |||

| W | 16.000 | 1.157 | 13.732 | 18.268 | ||||||

| 2 | A | 9.000 | 1.638 | 5.789 | 12.211 | 0.247 | ||||

| W | 14.000 | 1.927 | 10.223 | 17.777 | ||||||

| 3 | A | 9.000 | 1.083 | 6.877 | 11.123 | 0.475 | ||||

| W | 9.000 | 0.473 | 8.073 | 9.927 | ||||||

| 4 | A | 21.000 | 12.897 | 0.000 | 46.278 | 0.246 | ||||

| W | 14.000 | 3.309 | 7.514 | 20.486 | ||||||

| SESa | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

|

Raceb Stratified by SESa |

A | 1 | 7.000 | 1.035 | 4.971 | 9.029 | 0.306 | 0.871 | 1.000 | |

| 2 | 13.000 | 2.601 | 7.901 | 18.099 | 0.122 | 0.041 | ||||

| 3 | 10.000 | 1.081 | 7.881 | 12.119 | 0.562 | |||||

| 4 | 9.000 | 1.196 | 6.655 | 11.345 | ||||||

| W | 1 | 13.000 | 0.945 | 11.148 | 14.852 | 0.424 | 0.244 | 0.029 | ||

| 2 | 12.000 | 0.771 | 10.488 | 13.512 | 0.641 | 0.048 | ||||

| 3 | 11.000 | 0.569 | 9.884 | 12.116 | 0.071 | |||||

| 4 | 8.000 | 2.534 | 3.034 | 12.966 | ||||||

Socioeconomic Status: SES 1 = “wealthiest”; SES 4 = “poorest”

Race: A = African-American; W = Non-Hispanic White

Log rank score <0.050 interpreted as being significant

When SES is stratified by race, there is no significant difference in survival time. In other words, there was no difference in survival times of African-Americans compared with Non-Hispanic Whites within the same SES category. However, when comparing race stratified by SES, there were significant differences in survival times. Specifically, there was a significant difference in survival of SES 2 compared with SES 4 in African-Americans. The median survival time of African-Americans in the SES 4 category was 9 months compared with approximately 13 months in the SES 2 category (log rank score 0.41). Likewise, there was a significant difference in survival of SES 1 and SES 2 compared with SES 4 in Non-Hispanic Whites. In Non-Hispanic Whites, the median survival time of patients in the SES 4 category was roughly 8 months compared with approximately 13 months and 12 months for SES 1 and 2 respectively (log rank score 0.029 and 0.048 respectively).

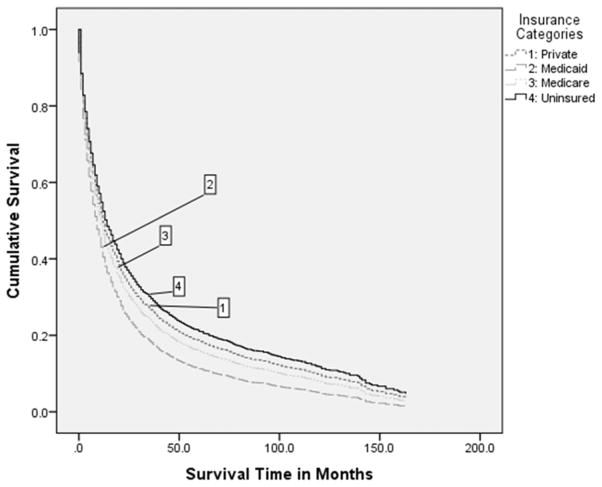

Survival time comparison between insurance groups is shown in Figure V represented by Cox regression analysis. The regression shows a significant difference in survival between these groups (Chi-square value 111.8; Significance <0.01). Overall, the uninsured group had the best survival and the Medicaid group had the worst survival.

Figure V.

Cox proportional hazards regression showing the cumulative percentage of the population surviving after a specified amount of time. The plots were generated using the mean of the covariates which included insurance type, as specified in the graph, and age.

Discussion

This study shows that African-Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites who reside in Delaware and utilize the Christiana Care Hospital System/Helen F Graham Cancer Center are likely to have the same survival outcome after being diagnosed and treated for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This is also true when comparing African-Americans to Non-Hispanic Whites who are considered to have the same socioeconomic status. However, like other studies, this study showed that patients with NSCLC who have the lowest socioeconomic status had shorter survival times compared with patients in the other groups, regardless of race. Furthermore, this study also compared survival outcomes of NSCLC patients with different insurance types and found that patients who were uninsured tended to live the longest while patients with Medicaid had the shortest survival times. Finally, we also saw that a large proportion of the entire cohort was diagnosed with later stage cancers.

Race

There are multiple studies that have been published over the past two decades demonstrating a survival advantage in whites who are diagnosed with NSCLC when compared with those of the black population[14–18]. However, like the multivariate analysis published by Yang et. al, the present study seems to have contradicted this, and showed that our institution is moving in the right direction [5]. It is not clear why we have eliminated this disparity and it is beyond the scope of this study. However, one hypothesis for this change could be from the implementation of statewide initiatives like the Delaware Tobacco Prevention and Control Program and the IMPACT Delaware Tobacco Prevention Coalition which was started in 1998. These programs educate and increase awareness on the dangers of smoking and have resulted in the reduction of tobacco usage[19, 20]. This change could also be a result of the multidisciplinary team and supportive staff, along with a strong cancer outreach program, at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, a National Cancer Institute selected Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP) and research institute, which was established in 2007. A study by Onega et al supports the notion that NCI centers do eliminate racial disparities in patients with lung cancer, but it is not clear if this is the case for our institution and further study will need to be conducted to elucidate on this hypothesis [21].

Socioeconomic Status

It is globally demonstrated that lower socioeconomic status results in poorer outcomes in lung cancer patients when compared to those of higher status[22]. SES is said to be an independent risk factor for poor outcomes and some even label it as a carcinogen [18, 22, 23]. This study was no different. Patients with the lowest SES had the lowest chance of longevity. However, of note, only 8% of our study population fell within this SES group. Overall, the majority of our patient population fell within the SES 3 group, which is the second “poorest” group. This is important because this group had no statistical difference in survival outcome when compared to the two most “wealthiest” groups. Although our institution has not fully eliminated all disparities in survival outcomes at a socioeconomic level, there seems to be equalization between most groups with the exception of the poorest SES group.

Insurance Type

A similar study published by Yorio et al chooses a different method for classifying patients into SES groups. In their study, they argue that insurance type is a better classification method for SES because it is specific to the patient, regardless of zip code, and because other studies show it to be a better representation of wealth than by using indicators of income alone [4, 24]. Therefore, we chose to investigate survival differences in patients with different insurance types as an independent variable of wealth. Not surprisingly, our analysis produced supportive evidence to the current literature that suggests private insurance holders have better survival outcomes than those with Medicaid or Medicare. Conversely, our analysis contradicts a recent systematic review by the American Thoracic Society in that patients who were uninsured in our population group did not have less favorable outcomes than those with the other insurance types[25]. Our study showed that the uninsured population had the most favorable survival outcome out of all four groups. It should be stated that the Delaware Cancer Treatment Program provides free cancer care to eligible uninsured patients for up to two years after being diagnosed with cancer[26]. This could be a contributory factor for these outcomes. Nevertheless, if insurance type is an accurate depiction of socioeconomic status, our results show that the uninsured are receiving satisfactory care and improvements of outcomes for the Medicaid group should be a focus for our institution to further reduce disparities in the future.

Limitations

Comorbid conditions were not available in this cohort and could not be accounted for. Previous cancer history was also missing. Specific cause of death was not provided and had to be censored. Sample sizes for some of the categorical variables were too small to yield accurate analytical results. This study did not include other institutional (non-CCHS) data within our state from the same time period to be used for direct comparison and could be the focus of a future study. Finally, the scope of this study was limited in that it could not account for the causes of our results, only potential correlations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, eliminating health disparities has become a main focal point for improving quality, access and the cost of healthcare in the United States. Many governing bodies and institutions recommend vigorous measure and analysis of disparity data in an attempt to understand the causes of health disparities and to monitor the changes in these disparities over time. In compliance with this mandate, we have set out to publish our institutions health disparities “report card.” Our results have been promising, but there is still work to be done. Although we have closed the gap on sex and racial disparities, there remains a difference in survival outcomes across socioeconomic classes and insurance types. For now, emphasis should be placed on prevention, smoking cessation and earlier diagnosis of lung cancer so that significant improvements in survival outcomes can be achieved across all study groups.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This project was supported by the Delaware INBRE program, with a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences – NIGMS (8 P20 GM103446-13) from the National Institutes of Health. (The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH)

The authors would like to acknowledge Seema Sonnad, PhD from the Value Institute at CCHS for assistance with statistical analysis and manuscript review.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer Disparities By Race/Ethnicity And Socioeconomic Status [Internet] CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Healthy People 2010 Final Review. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byers T, Mouchawar J, Marks J, et al. The American Cancer Society Challenge Goals [Internet] Cancer. 1999;86:715–727. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<715::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yorio JT, Yan J, Xie Y, et al. Socioeconomic Disparities In Lung Cancer Treatment And Outcomes Persist Within A Single Academic Medical Center [Internet] Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:448–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.03.002. [cited 2013 Oct 18] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22512997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang R, Cheung MC, Byrne MM, et al. Do Racial Or Socioeconomic Disparities Exist In Lung Cancer Treatment? [Internet] Cancer. 2010;116:2437–2447. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24986. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groth SS, D’Cunha J. Lung Cancer Outcomes: The Effects Of Socioeconomic Status And Race [Internet] Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;22:116–117. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2010.08.003. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043067910000699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemal A, Thun MJ, et al. Annual Report To The Nation On The Status Of Cancer: 1975–2005; Featuring Trends In Lung Cancer, Tobacco Use And Tobacco Control [Internet] J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1672–1694. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn389. Available from: http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/100/23/1672.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, et al. Impact Of Socioeconomic Status On Cancer Incidence And Stage At Diagnosis: Selected Findings From The Surveillance, Epidemiology, And End Results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:417–435. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Islami F, Kahn AR, Bickell NA, et al. Disentangling The Effects Of Race/ethnicity And Socioeconomic Status Of Neighborhood In Cancer Stage Distribution In New York City [Internet] Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:1069–78. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0184-2. [cited 2013 Oct 19] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23504151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forrest LF, Adams J, Wareham H, et al. Socioeconomic Inequalities In Lung Cancer Treatment: Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis [Internet] PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001376. [cited 2013 Oct 18] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3564770&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper S, Lynch J. Methods For Measuring Cancer Disparities: Using Data Relevant To Healthy People 2010 Cancer-Related Objectives. National Cancer Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.ProximityOne. Census 2010 ZIP Code To Census Tract Interactive Ranking & Equivalence Table [Internet] 2013 Available from: http://proximityone.com/ziptractequiv.htm.

- 13.American Community Survey Summary File [Internet] 2011 [cited 2013 Dec 3] Available from: http://www.census.gov/acs/www/data_documentation/summary_file/

- 14.Booske BC, Robert SA, Rohan AM. Awareness Of Racial And Socioeconomic Health Disparities In The United States: The National Opinion Survey On Health And Health Disparities, 2008–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLancey JOL, Thun MJ, Jemal A, et al. Recent Trends In Black-White Disparities In Cancer Mortality [Internet] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2908–2912. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0131. Available from: http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/17/11/2908.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bach PB, Cramer LD, Warren JL, et al. Racial Differences In The Treatment Of Early-Stage Lung Cancer [Internet] N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1198–205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10519898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach PB, MD, Cramer LD, ScM, Warren JL, PhD, et al. Racial Differences In The Treatment Of Early- Stage Lung Cancer [Internet] N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1198–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenwald HP, Polissar NL, Borgatta EF, et al. Social Factors, Treatment, And Survival In Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer [Internet] Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1681–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1681. [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1508564&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abramson-Chen EFAU, Khan OFAU, Raman T. Perceptions Of Smoking And Lung Cancer In New Castle County, Delaware. Delaware Med J JID - 0370077. 2012;84:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health CO on S and. Smoking And Tobacco Use; Tobacco Control State Highlights 2012; Delaware [Internet] [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/state_data/state_highlights/2012/states/delaware/index.htm.

- 21.Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, et al. Race Versus Place Of Service In Mortality Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Cancer [Internet] Cancer. 2010;116:2698–706. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25097. [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3277834&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberg AJ, Ford JG, Samet JM. Epidemiology Of Lung Cancer: ACCP Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (2nd Edition) [Internet] Chest. 2007;132:29S–55S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1347. [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17873159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knaggs H. Origins Of Human Cancer: A Comprehensive Review [Internet] Biochem Educ. 1993;21:112–113. [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/030744129390075B. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. Socioeconomic Status In Health Research: One Size Does Not Fit All [Internet] JAMA. 2005;294:2879–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16352796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slatore CG, Au DH, Gould MK. An Official American Thoracic Society Systematic Review: Insurance Status And Disparities In Lung Cancer Practices And Outcomes [Internet] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1195–205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-038ST. [cited 2013 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21041563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Delaware Cancer Treatment Program [Internet] 2009 [cited 2013 Feb 11] Available from: http://dhss.delaware.gov/dph/dpc/catreatment.html.

- 27.Spencer CS, Gaskin DJ, Roberts ET. The Quality Of Care Delivered To Patients Within The Same Hospital Varies By Insurance Type [Internet] Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1731–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1400. [cited 2013 Nov 7] Available from: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/10/1731.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]